Hydrothermal Carbonization of Biomass for Hydrochar Production: Mechanisms, Process Parameters, and Sustainable Valorization

Abstract

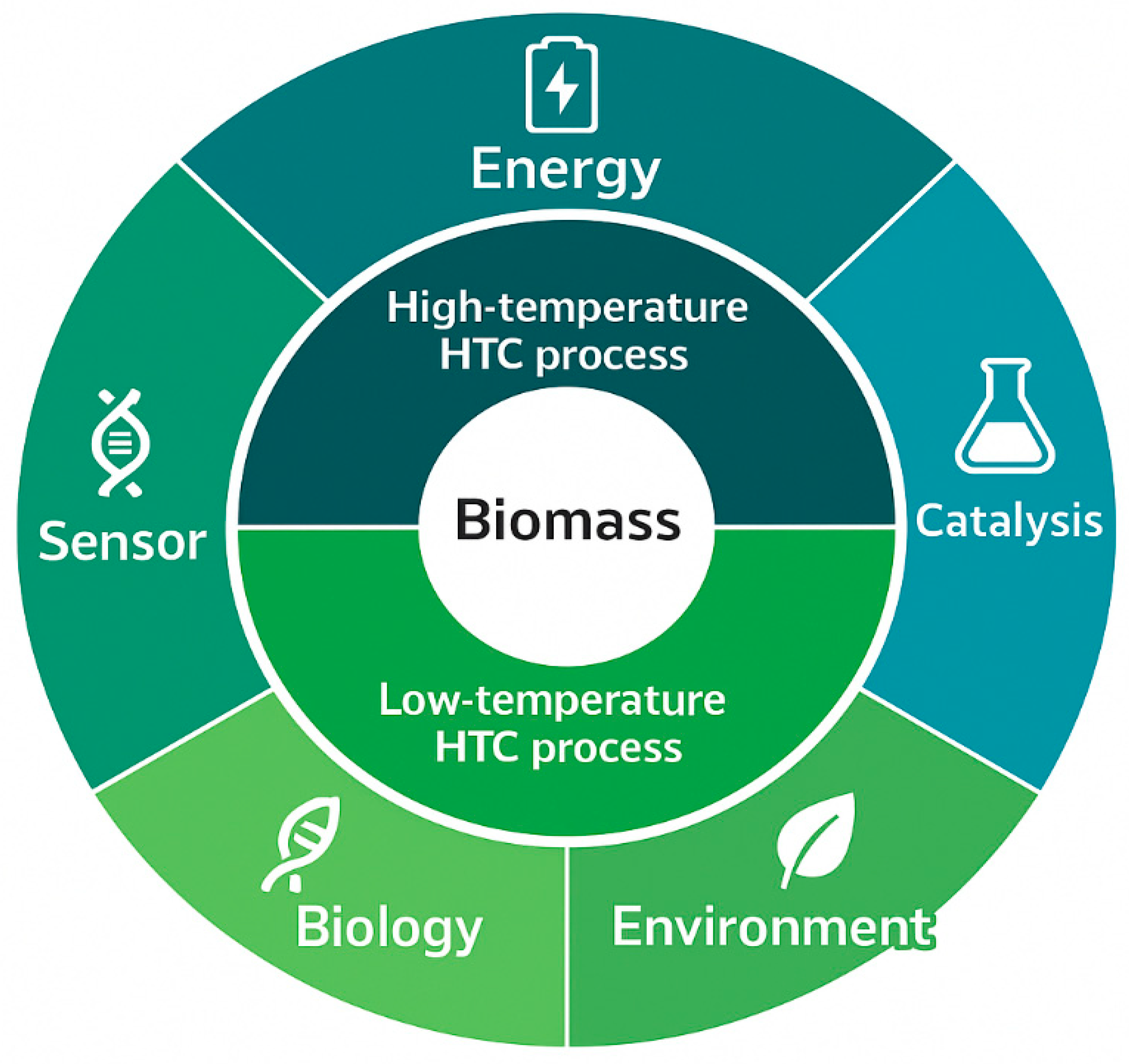

1. Introduction

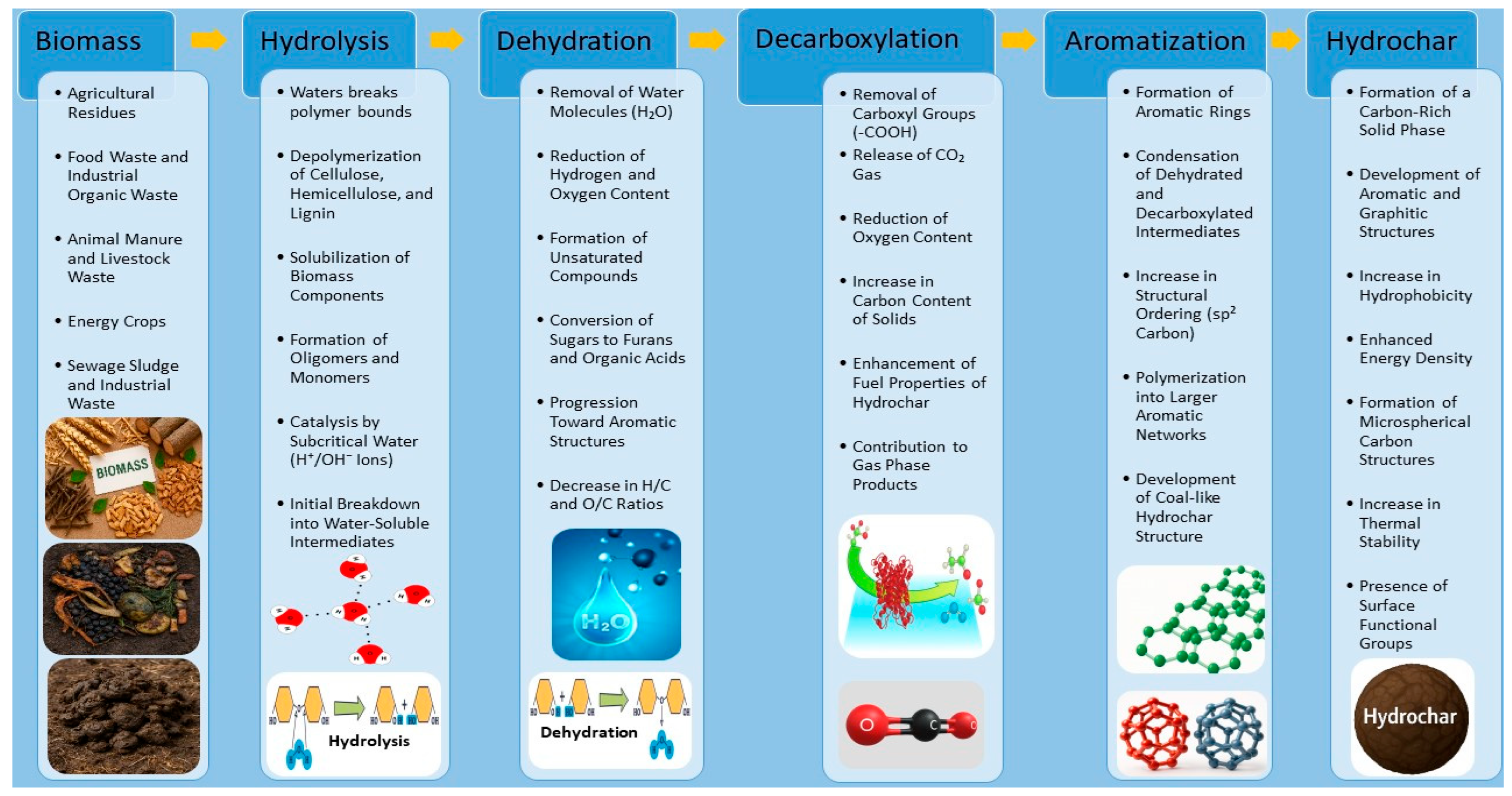

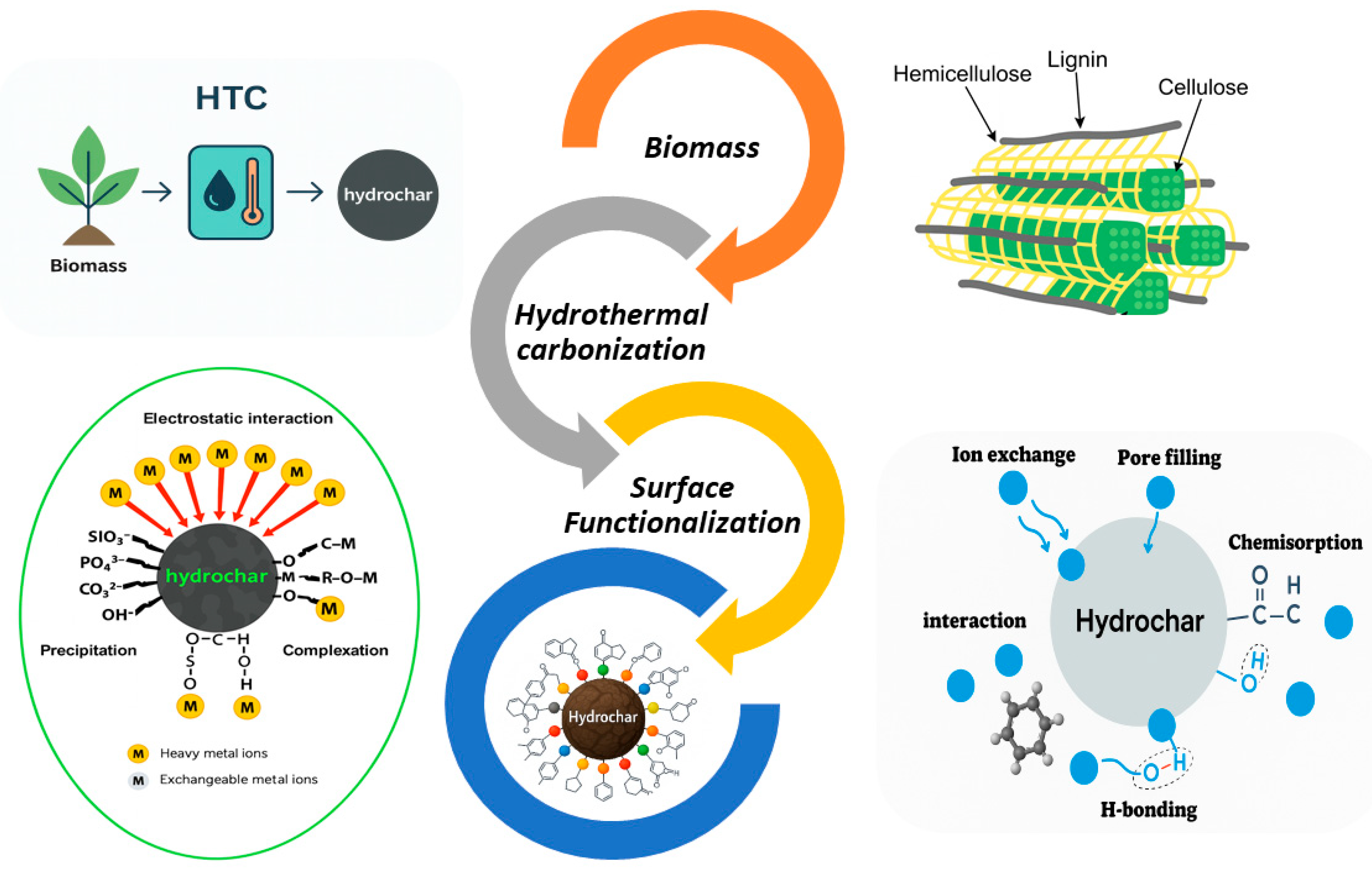

2. Fundamentals and Reaction Mechanisms of Hydrothermal Carbonization (HTC)

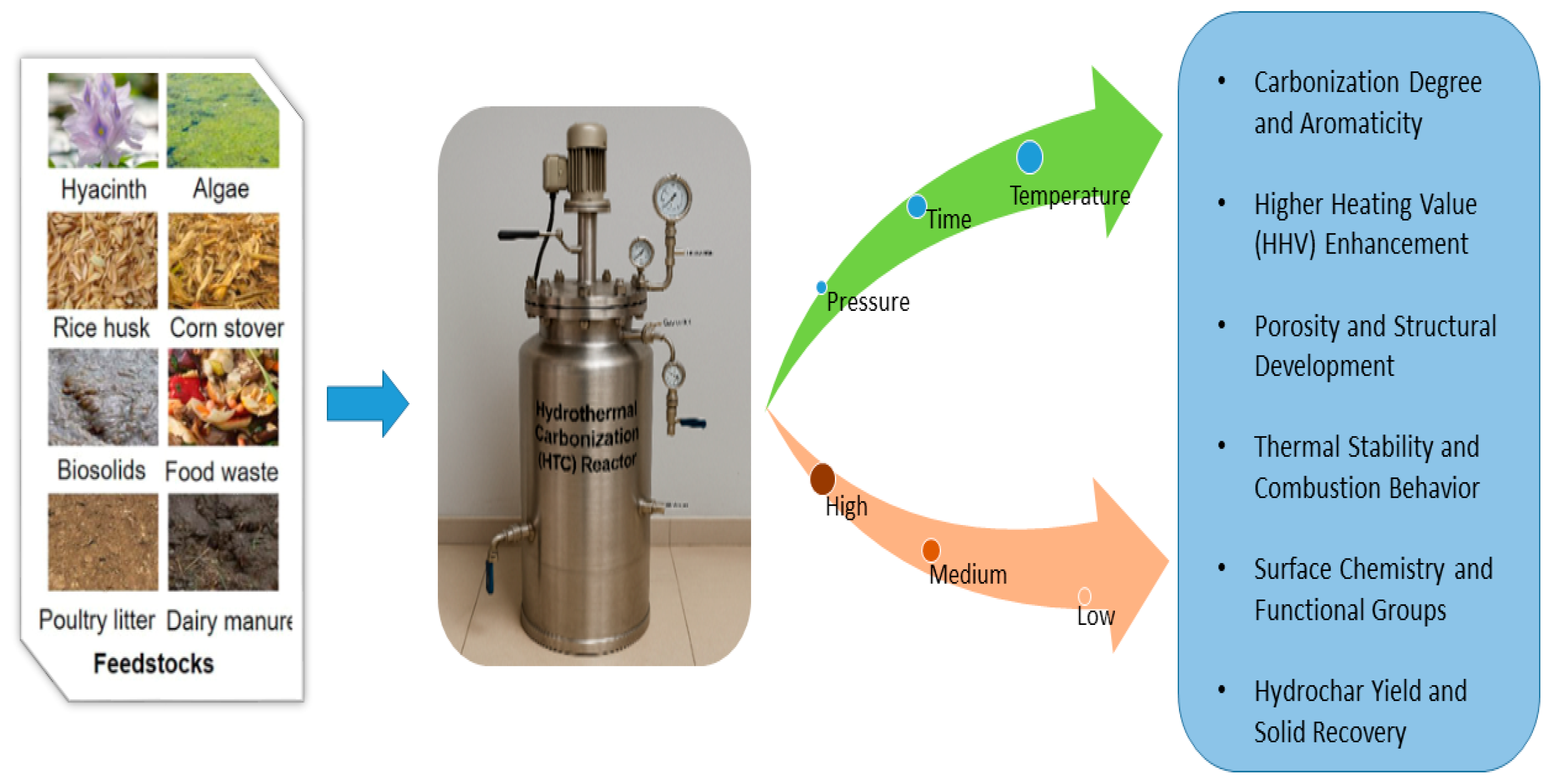

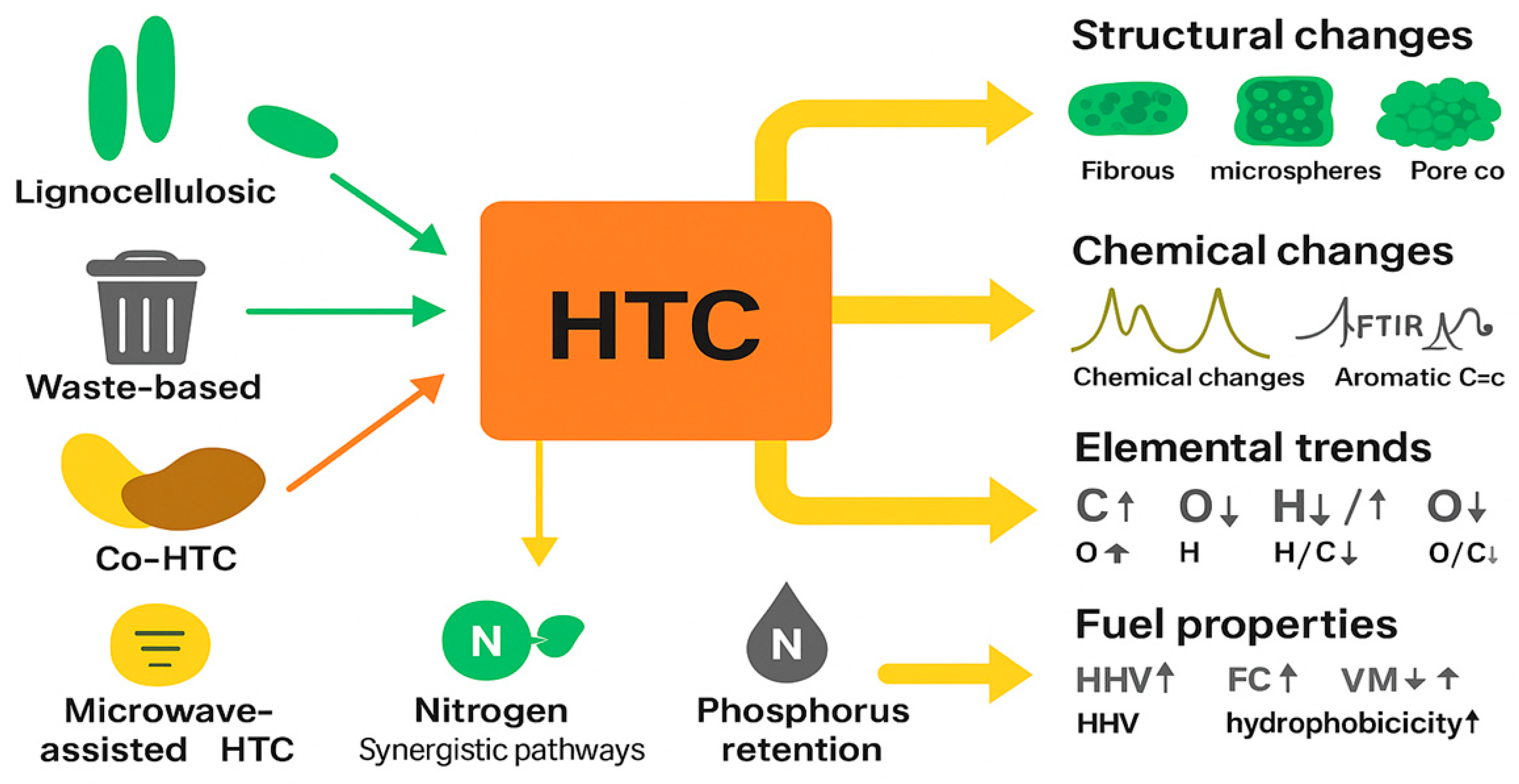

3. Influence of Process Parameters on Hydrochar Yield and Properties

4. Physicochemical Properties of Hydrochar

5. Functional Materials

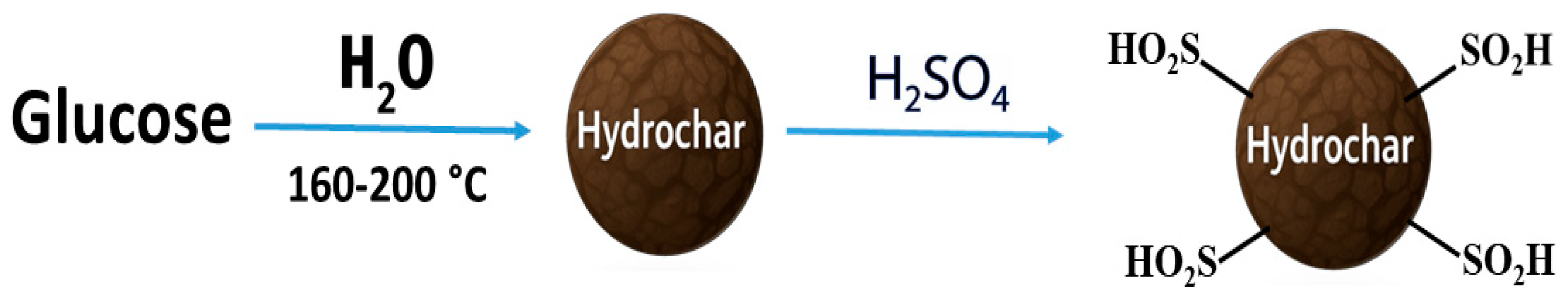

5.1. Heterogeneous Catalysis

- In situ templating (hard and soft templates): Researchers often use templates during the HTC process to prevent the formation of dense microspheres [104]. In hard templates, after the carbon is formed, the silica is etched away with HF or NaOH, leaving behind a carbon skeleton with a controlled pore size [105]. In soft templates, it is typical to use surfactants (like Pluronic F127) to guide the polymerization of carbon precursors into ordered mesoporous structures [106].

- Graphene oxide (GO) assistance: Studies have shown that adding small amounts of graphene oxide during HTC acts as a 2D template [107,108,109]. This may prevent the “clumping” of carbon, and it results in flake-like or platelet-like structures that significantly boost the initial SSA before any further chemical activation.

5.2. Adsorption

5.3. Soil Amendment and Agricultural Applications

5.4. Activated Carbon and Carbon-Derived Materials

6. Functionalization of HTC Products

7. Sustainability Assessment

7.1. Sustainability Development

7.2. Circular Economy

7.3. Environmental Sustainability

7.4. Economic Sustainability

8. Challenges, Limitations, and Future Perspectives

8.1. Challenges in Scaling up HTC Processes

8.2. Controlling Product Quality Variability in HTC

8.3. Emerging Directions for Future HTC Research

9. Conclusions

- Fundamental Mechanistic Gaps: The comprehensive reaction chemistry underlying HTC, including kinetics, the formation of intermediates, and polymerization pathways, remains inadequately characterized, particularly for innovative approaches like co-HTC or microwave-assisted HTC. Without a deeper mechanistic understanding, the development of predictive models and effective process control measures is hampered.

- Reactor Engineering and Scalability: Most existing HTC research has been conducted using small-scale batch reactors. The design of continuous pilot-scale systems that feature effective heat integration is critical for practical applications. Current batch-to-batch variability, along with heat losses, must be addressed through novel reactor designs.

- Process Water Treatment: HTC generates a process effluent that is typically acidic and laden with organics and nutrients. Robust methodologies for treating or valorizing this aqueous byproduct are currently lacking. Further investigation is required into nutrient recycling, energy or chemical recovery from the effluent, and the potential integration of HTC with wastewater treatment solutions, such as coupled anaerobic digestion, to manage this byproduct efficiently.

- Standardization of Hydrochar Quality: There is no consensus on the characterization standards or quality metrics for hydrochar. Inconsistent protocols for proximate and ultimate analyses, surface chemistry assessments, and calorific value determinations hinder the comparability of cross-study results. The establishment of standardized production methodologies and analytical protocols is imperative for the consistent evaluation of hydrochar properties.

- Techno-Economic and Life-Cycle Evaluation: System-wide analyses of HTC methodologies are still limited. Comprehensive techno-economic evaluations and life-cycle assessments are essential to elucidate cost factors, energy balances, and environmental repercussions on a larger scale. In the absence of such studies, benchmarks for HTC against alternative waste management and energy strategies are difficult to ascertain.

- Continuous Reactor Development: The design and implementation of continuous HTC systems, such as tubular or screw reactors, should be pursued to optimize heat recovery and material handling. Pilot-scale experiments are needed to bridge the gap between laboratory findings and industrial applications, validating performance during sustained operation.

- Integration into Biorefinery Processes: HTC may be effectively combined with other complementary treatments such as anaerobic digestion, pyrolysis, and gasification within integrated biorefinery frameworks. Such synergies could improve overall energy and nutrient recovery, for instance, by utilizing HTC effluent as feed for anaerobic digestion or repurposing residual heat for process integration. The recycling of process water as feedstock or fermentation medium could minimize waste generation.

- Hydrochar Activation and Functionalization: Advancing post-HTC processing methods is essential to enhance the functionality of hydrochar. Techniques such as physical or chemical activation (utilizing steam, CO2, KOH, etc.), heteroatom doping, and templating can yield highly porous activated carbons tailored for specific applications, such as electrodes for energy storage or catalysts for pollutant degradation. Research should aim to optimize these methodologies to devise hydrochars designed for particular uses.

- Standardized Protocols and Metrics: The development of consensus protocols for HTC processing and hydrochar evaluation is necessary. This includes establishing standardized feedstock preparation methods, reaction protocols, and analytical techniques (such as elemental analysis, BET surface area assessment, functional-group quantification, and measurement of heating values). Additionally, benchmark comparisons of hydrochar against traditional materials like biochar and activated carbon should be conducted to enhance clarity and utility in this field.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gollakota, A.R.K.; Kishore, N.; Gu, S. A review on hydrothermal liquefaction of biomass. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1378–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Lin, G.; Guo, S.; Wang, S.; Guo, Y.; Jing, Z. Catalytic hydrothermal liquefaction of algae and upgrading of biocrude: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 97, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak, H. Comprehensive Assessment of Thermochemical Processes for Sustainable Waste Management and Resource Recovery. Processes 2023, 11, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.W.; Lee, S.H.; Nam, H.; Lee, D.; Tokmurzin, D.; Wang, S.; Park, Y.K. Recent advances of thermochemical conversion processes for biorefinery. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 343, 126109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.; Inayat, A.; Abu-Jdayil, B. Crude Glycerol as a Potential Feedstock for Future Energy via Thermochemical Conversion Processes: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, J.; Petrović, M.; Ercegovic, M.; Koprivica, M.; Milenković, M.; Nuic, I. Upgrading fuel potentials of waste biomass via hydrothermal carbonization. Hem. Ind. 2021, 75, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhai, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, C.; Zeng, G. A review of the hydrothermal carbonization of biomass waste for hydrochar formation: Process conditions, fundamentals, and physicochemical properties. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, J.; Ercegović, M.; Simić, M.; Koprivica, M.; Dimitrijević, J.; Jovanović, A.; Janković Pantić, J. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Waste Biomass: A Review of Hydrochar Preparation and Environmental Application. Processes 2024, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavali, M.; Libardi Junior, N.; de Sena, J.D.; Woiciechowski, A.L.; Soccol, C.R.; Belli Filho, P.; Bayard, R.; Benbelkacem, H.; de Castilhos Junior, A.B. A review on hydrothermal carbonization of potential biomass wastes, characterization and environmental applications of hydrochar, and biorefinery perspectives of the process. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhan, L.; Ok, Y.S.; Gao, B. Minireview of potential applications of hydrochar derived from hydrothermal carbonization of biomass. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 57, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.-W.; Lee, S.Y.; Choi, J.W.; Lee, Y. A facile one-pot hydrothermal synthesis of hydroxyapatite/biochar nanocomposites: Adsorption behavior and mechanisms for the removal of copper(II) from aqueous media. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 369, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antero, R.V.P.; Alves, A.C.F.; de Oliveira, S.B.; Ojala, S.A.; Brum, S.S. Challenges and alternatives for the adequacy of hydrothermal carbonization of lignocellulosic biomass in cleaner production systems: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Shen, B.; Liu, L. Insights into biochar and hydrochar production and applications: A review. Energy 2019, 171, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Balasubramanian, R.; Srinivasan, M.P. Tuning hydrochar properties for enhanced mesopore development in activated carbon by hydrothermal carbonization. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2015, 203, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, S.; Shang, H.; Luo, J.; Tsang, D.C.W. Chapter 15—Hydrothermal Carbonization for Hydrochar Production and Its Application. In Biochar from Biomass and Waste; Ok, Y.S., Tsang, D.C.W., Bolan, N., Novak, J.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, Ž.; Markočič, E.; Knez Marevci, M.; Ravber, M.; Škerget, M. High Pressure Water Reforming of Biomass for Energy and Chemicals: A Short Review. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2014, 96, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, Q.; Cui, D.; Wang, X.; Wu, D.; Bai, J.; Xu, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J. Analysis of fuel properties of hydrochar derived from food waste and biomass: Evaluating varied mixing techniques pre/post-hydrothermal carbonization. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 430, 139660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighalo, J.O.; Akaeme, F.C.; Georgin, J.; de Oliveira, J.S.; Franco, D.S.P. Biomass Hydrochar: A Critical Review of Process Chemistry, Synthesis Methodology, and Applications. Processes 2025, 17, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajlović, M.; Petrović, J.; Maletić, S.; Isakovski, M.K.; Stojanović, M.; Lopičić, Z.; Trifunović, S. Hydrothermal carbonization of Miscanthus × giganteus: Structural and fuel properties of hydrochars and organic profile with the ecotoxicological assessment of the liquid phase. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 159, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, C.; Alves, O.; Durão, L.; Şen, A.; Vilarinho, C.; Gonçalves, M. Characterization of hydrochar and process water from the hydrothermal carbonization of Refuse Derived Fuel. Waste Manag. 2021, 120, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, X.; Teng, H.; Wang, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, N.; Huang, C.; Wang, C. Physiochemical, structural and combustion properties of hydrochar obtained by hydrothermal carbonization of waste polyvinyl chloride. Fuel 2020, 270, 117526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.T.; Mansouri, S.S.; Udugama, I.A.; Baroutian, S.; Gernaey, K.V.; Young, B.R. Resource recovery from organic solid waste using hydrothermal processing: Opportunities and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 96, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Chen, H.; Chen, K.; Ren, S.; Clark, J.H.; Fan, J.; Luo, G.; Zhang, S. Characterization and utilization of aqueous products from hydrothermal conversion of biomass for bio-oil and hydro-char production: A review. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 1553–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Taiwo, K.; Wang, H.; Ntihuga, J.-N.; Angenent, L.T.; Usack, J.G. Anaerobic digestion of process water from hydrothermal treatment processes: A review of inhibitors and detoxification approaches. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2024, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannan, S.; Burelle, I.; Orsat, V.; Raghavan, V. Characterization of Bio-crude Liquor and Bio-oil Produced by Hydrothermal Carbonization of Seafood Waste. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 3553–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, J.V.; Fregolente, L.; Laranja, M.; Moreira, A.; Ferreira, O.; Bisinoti, M. Hydrothermal carbonization of sugarcane industry by-products and process water reuse: Structural, morphological, and fuel properties of hydrochars. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2022, 12, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak, E.D. Antifungal potential of hydrothermal liquefaction wastewater in plant protection. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 41, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, S.; Borugadda, V.B.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K. Hydrochar: A Review on Its Production Technologies and Applications. Processes 2021, 11, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilian, M.; Bissessur, R.; Ahmed, M.; Hsiao, A.; He, Q.; Hu, Y. A review: Hydrochar as potential adsorbents for wastewater treatment and CO2 adsorption. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.; Espada, J.J. Environmental and techno-economic assessment of thermochemical treatment systems for sludge. In Wastewater Treatment Residues as Resources for Sustainable Recovery; Elseiver: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akmach, D.; Bathla, S.; Tran, C.-C.; Kaliaguine, S.; Mushrif, S.H. Transition metal carbide catalysts for Upgrading lignocellulosic biomass-derived oxygenates: A review of the experimental and computational investigations into structure-property relationships. Catal. Today 2023, 423, 114285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colin, J.; Sarrion, A.; Diaz, E.; de la Rubia, M.A.; Mohedano, A.F. Ecotoxicity assessment of hydrochar from hydrothermal carbonization of biomass waste. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 44, 101909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.P.; Shi, Z.J.; Xu, F.; Sun, R.C. Hydrothermal carbonization of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 118, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascó, G.; Paz-Ferreiro, J.; Álvarez, M.L.; Saa, A.; Méndez, A. Biochars and hydrochars prepared by pyrolysis and hydrothermal carbonisation of pig manure. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cognigni, P.; Leonelli, C.; Berrettoni, M. A bibliographic study of biochar and hydrochar: Differences and similarities. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2025, 187, 106985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Peng, X.; Sun, S.; Zhong, L.; Sun, R. Hydrothermal Conversion of Bamboo: Identification and Distribution of the Components in Solid Residue, Water-Soluble and Acetone-Soluble Fractions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 12360–12365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Qian, Q.; Quek, A.; Ai, N.; Zeng, G.; Wang, J. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Macroalgae and the Effects of Experimental Parameters on the Properties of Hydrochars. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2013, 1, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Guo, Y.; Luo, L.; Liu, Z.; Miao, W.; Xia, Y. A critical review of hydrochar based photocatalysts by hydrothermal carbonization: Synthesis, mechanisms, and applications. Biochar 2024, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Dong, C.; Wang, G.; Zhang, J.; Hou, R. Phosphorus-rich biochar/hydrochar: Review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 33649–33665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oumabady, S.; Sebastian, S.P.; Kamaludeen, S.P.B.; Ramasamy, M.; Kalaiselvi, P.; Parameswari, E. Preparation and Characterization of Optimized Hydrochar from Paper Board Mill Sludge. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojewumi, M.E.; Chen, G. Hydrochar Production by Hydrothermal Carbonization: Microwave versus Supercritical Water Treatment. Biomass 2024, 4, 574–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.V.; Kanaan, A.F.; Voll, F.A.P.; Corazza, M.L. Hydrothermal carbonization of digestate from sewage sludge: Evaluating the impact of process parameters in hydrochar yield and characterization. Fuel 2026, 405, 136672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, E.; Jariyaboon, R.; Reungsang, A.; Chucheep, T.; Kongjan, P. Optimization of hydrothermal carbonization parameters of sugarcane residues for enhanced hydrochar fuel properties with ammonium adsorption assessment. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2026, 320, 122576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.M.; Kousar, S.; Jiang, Y.; Fan, M.; Stelgen, I.; Zhang, S.; Hu, X. Influence of externally added organic or inorganic acids on evolution of property of hydrochar from hydrothermal carbonization of potato peel. Biomass Bioenergy 2026, 204, 108393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Meng, W.; Xu, C.; Fan, X.; Yang, J.; Chen, M.; Tang, W.; Leng, L.; Zhan, H.; Li, H. Co-hydrothermal carbonization of antibiotic fermentation residues and Camellia oleifera shell: Enhancing coalification, demineralization, and denitrogenation for producing solid biofuel. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378, 134633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H. Utilization of potato peel waste in cyanobacterium Spirulina sp. cultivation for biodiesel production and subsequent hydrochar production via optimized hydrothermal carbonization process. Renew. Energy 2025, 255, 123815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Ye, J.; Luo, C.; Wang, H.; Sun, H.; Chen, L.; Liao, Z.; Ying, Y. Energy recovery and critical element immobilization in medical waste-derived fuel: Hydrothermal vs. vapor thermal carbonization. Fuel 2025, 402, 135985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, S.; Onat, E.; Levent, A.; Astan, R. Hydrochar-derived activated carbon from chenopodium botrys for dual applications in dye removal and energy storage. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 159, 112834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrez, K.; Fryda, L.; Djelal, H.; Mercier, M.; Wray, H.; Kane, A.; Leblanc, N.; Visser, R. Hydrothermal treatment of contaminated sorghum: Hydrochar properties and characterization/phytotoxicity evaluation of the liquid phase. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambli, J.; Quitain, A.T.; Khezri, R.; Wan Ab Karim Ghani, W.A.; Assabumrungrat, S.; Kida, T. Microwave-assisted hydrothermal carbonization of sago (Metroxylon spp) to hydrochar as potential catalyst for etherification of glycerol. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 201, 108143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Huang, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Wei, X.; Wu, S. Physicochemical Characterization and Formation Pathway of Hydrochar from Brewer’s Spent Grain via Hydrothermal Carbonization. Catalysts 2025, 15, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xia, P.; Zhao, L.; Yang, C.; Wang, K.; Ling, Y.; Huang, Z. The combustion characteristics of hydrothermal carbonization products from traditional Chinese medicine residue. Energy 2025, 330, 136814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Choi, J.W.; Oh, D.Y.; Lee, K.; Park, K.Y.; Kim, D. Chemical upgrading of hydrochar from waste coir substrate from controlled environment agriculture using hydrothermal carbonization. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2025, 27, 4379–4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alper, K. Effect of Acrylic Acid Concentration on the Hydrothermal Carbonization of Stevia rebaudiana Biomass and Resulting Hydrochar Properties. Processes 2025, 13, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Gómez, J.M.; Orozco, L.M.; Renz, M.; Veloza, L.A. Hydrothermal carbonization of Colombian plantain peels: Physicochemical properties, thermal behavior, and bioactive potential. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 46, 102118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Mena, L.; Campana, R.; Villardon, A.; Dorado, F.; Sánchez-Silva, L. Optimisation of hydrothermal carbonisation of olive stones for enhanced CO2 capture: Impact of zinc chloride activation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Xie, Z.; Han, Z. Effects of hydrothermal carbonization process parameters on phase composition and the microstructure of corn stalk hydrochars. High Temp. Mater. Process. 2025, 44, 20250079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, D.; Xiong, L.; Dan, J.; Xu, K.; Yuan, X.; Kan, G.; Ning, X.; Wang, C. Application of catalysts in biomass hydrothermal carbonization for the preparation of high-quality blast furnace injection fuel. Energy 2023, 283, 129147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.-B.; Pan, Z.-Q.; Xiao, X.-F.; Huang, H.-J.; Lai, F.-Y.; Wang, J.-X.; Chen, S.-W. Study on the hydrothermal carbonization of swine manure: The effect of process parameters on the yield/properties of hydrochar and process water. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2019, 144, 104692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Akber, M.A.; Limon, S.H.; Akbor, M.A.; Islam, M.A. Characterization of solid biofuel produced from banana stalk via hydrothermal carbonization. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2019, 9, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Li, B.; Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, K. Hydrothermal carbonization of tobacco stalk for fuel application. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 220, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, S.; Alavi, N.; Tavakoli, O.; Shahsavani, A.; Sadani, M. Optimization of hydrothermal carbonization of food waste as sustainable energy conversion approach: Enhancing the properties of hydrochar by landfill leachate substitution as reaction medium and acetic acid catalyst addition. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 297, 117647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majee, P.; Periyavaram, S.R.; Uppala, L.; Reddy, P.H.P. Physicochemical and Energy Characteristics of Biochar and Hydrochar Derived from Cotton Stalks: A Comparative Study. BioEnergy Res. 2025, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, G.; Xu, J.; Xu, H.; Yuan, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Sarma, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Microwave-assisted hydrothermal carbonization of dairy manure: Chemical and structural properties of the products. Energy 2018, 165, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Wang, G.; Xu, R.; Ning, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, X.; Ye, L.; Li, J.; Jiang, C.; Wang, P.; et al. Hydrothermal carbonization of forest waste into solid fuel: Mechanism and combustion behavior. Energy 2022, 246, 123343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, J.; Wang, G.; Ning, X.; Meng, F.; Li, C.; Ye, L.; Wang, C. Physicochemical characteristics of three-phase products of low-rank coal by hydrothermal carbonization: Experimental research and quantum chemical calculation. Energy 2022, 261, 125347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Lee, S.E.; Shong, B.; Park, Y.-K.; Lee, H.-S. Valorization of cocoa bean shell residue from supercritical fluid extraction through hydrothermal carbonization for porous material production. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2025, 221, 106550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Chen, F.; Li, T.; Zhong, L.; Feng, H.; Xu, Z.; Hantoko, D.; Wibowo, H. Hydrothermal carbonization of food waste digestate solids: Effect of temperature and time on products characteristic and environmental evaluation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 178, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhu, X.; Shen, Q.; Huang, Y.; Xia, A.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q. Insights into hydrochar’s physicochemical properties evolution and nitrogen migration mechanism during co-hydrothermal carbonization of microalgae and corn stalk with FeCl3/NH4Cl/melamine addition. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 431, 132612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arauzo, P.J.; Checa-Gómez, M.; Maziarka, P.A.; Romuli, S.; Román, S. Influence of the biomass particle size during the hydrothermal carbonization of Jatropha curcas fruit residue to unlock its potential in bioenergy production. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 200, 107996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, C.G.; Lam, M.K.; Mohamed, A.R.; Lee, K.T. Hydrochar production from high-ash low-lipid microalgal biomass via hydrothermal carbonization: Effects of operational parameters and products characterization. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Cao, J.; Huang, W.; Feng, Y.; Xie, H.; Wang, B.; Xue, L. Hydrothermal carbonization of waste wet biomass achieves resource cycling: Regulating nutrient availability and generating economic benefits. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Sui, Z.; Shi, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, W. Investigation of the Effects of Cohydrothermal Carbonization on the Physicochemical Characteristics and Combustion Behavior of Straw Hydrochars. Energy Technol. 2023, 11, 2300245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, N.; Islam, M.A.; Liu, Z.; Hameed, B.H.; Islam, M.A. Co-hydrothermal carbonization of styrofoam and sawdust: Fuel properties evaluation and effect of water recirculation on hydrochar properties. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 6287–6296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolae, S.A.; Au, H.; Modugno, P.; Luo, H.; Szego, A.E.; Qiao, M.; Li, L.; Yin, W.; Heeres, H.J.; Berge, N.; et al. Recent advances in hydrothermal carbonisation: From tailored carbon materials and biochemicals to applications and bioenergy. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 4747–4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Wang, K.; Wu, L.; Yu, S.-H.; Antonietti, M.; Titirici, M.-M. Engineering Carbon Materials from the Hydrothermal Carbonization Process of Biomass. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Zhu, J.; Lv, L. Cellulose hydrolysis catalyzed by highly acidic lignin-derived carbonaceous catalyst synthesized via hydrothermal carbonization. Cellulose 2017, 24, 5327–5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, F.C.P.; Santos, J.L.; Araujo, R.O.; Santos, V.O.; Chaar, J.S.; Tenório, J.A.S.; de Souza, L.K.C. Sustainable catalysts for esterification: Sulfonated carbon spheres from biomass waste using hydrothermal carbonization. Renew. Energy 2024, 220, 119653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, G.; Yadav, N.; Ahmaruzzaman, M. Microwave-assisted synthesis of biodiesel by a green carbon-based heterogeneous catalyst derived from areca nut husk by one-pot hydrothermal carbonization. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, R.; Santos, V.; Ribeiro, F.; Chaar, J.; Falcão, N.; Souza, L. One-step synthesis of a heterogeneous catalyst by the hydrothermal carbonization of acai seed. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2021, 134, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowski, P.; Demir-Cakan, R.; Antonietti, M.; Goettmann, F.; Titirici, M. Selective partial hydrogenation of hydroxy aromatic derivatives with palladium nanoparticles supported on hydrophilic carbon. Chem. Commun. 2008, 8, 999–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahata, N.; Vishwanathan, V. Enhanced phenol hydrogenation activity on promoted palladium alumina catalysts for synthesis of cyclohexanone. Indian J. Chem. Sect. A 1998, 37, 652–654. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, S.; Krishna, K. Hydrotalcite-supported palladium catalysts: Part II. Preparation, characterization of hydrotalcites and palladium hydrotalcites for CO chemisorption and phenol hydrogenation. Appl. Catal. A 2000, 198, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir-Cakan, R.; Baccile, N.; Antonietti, M.; Titirici, M.-M. Carboxylate-Rich Carbonaceous Materials via One-Step Hydrothermal Carbonization of Glucose in the Presence of Acrylic Acid. Chem Mater 2009, 21, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir-Cakan, R.; Makowski, P.; Antonietti, M.; Goettmann, F.; Titirici, M.-M. Hydrothermal synthesis of imidazole functionalized carbon spheres and their application in catalysis. Catal. Today 2010, 150, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titirici, M.-M.; Antonietti, M. Chemistry and materials options of sustainable carbon materials made by hydrothermal carbonization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier-Bourbigou, H.; Magna, L. Ionic Liquids: Perspectives for Organic and Catalytic Reactions. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2003, 182–183, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, N.; Diez-Gonzalez, S.; Nolan, S. N-Heterocyclic Carbenes as Organocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2988–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaper, H.; Antonietti, M.; Goettmann, F. Metal-free activation of C–C multiple bonds through halide ion pairs: Diels–Alder reactions with subsequent aromatization. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 4546–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karod, M.; Pollard, Z.A.; Ahmad, M.T.; Dou, G.; Gao, L.; Goldfarb, J.L. Impact of Bentonite Clay on In Situ Pyrolysis vs. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Avocado Pit Biomass. Catalysts 2022, 12, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Street, J.; Yu, F. Synthesis of carbon-encapsulated iron nanoparticles from wood derived sugars by hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) and their application to convert bio-syngas into liquid hydrocarbons. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 83, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz de Tuesta, J.L.; Saviotti, M.C.; Roman, F.F.; Pantuzza, G.F.; Sartori, H.J.F.; Shinibekova, A.; Kalmakhanova, M.S.; Massalimova, B.K.; Pietrobelli, J.M.T.A.; Lenzi, G.G.; et al. Assisted hydrothermal carbonization of agroindustrial byproducts as effective step in the production of activated carbon catalysts for wet peroxide oxidation of micro-pollutants. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Cheng, L.; Shen, P.; Liu, Y. Methanol and ethanol electrooxidation on Pt and Pd supported on carbon microspheres in alkaline media. Electrochem. Commun. 2007, 9, 997–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, M.; Lota, G.; Fuertes, A.B. Saccharide-based graphitic carbon nanocoils as supports for PtRu nanoparticles for methanol electrooxidation. J. Power Sources 2007, 171, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.; Joo, J.-B.; Kim, W.; Kim, J.; Song, I.; Yi, J. Graphitic spherical carbon as a support for a PtRu-alloy catalyst in the methanol electro-oxidation. Catal. Lett. 2006, 112, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Zhu, W.; Wang, Z.; Huang, X.; Chen, L. Monodispersed hard carbon spherules as a catalyst support for the electrooxidation of methanol. Carbon 2005, 43, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.S.; Xu, C.-W.; Liu, Y.; Tan, S.; Wang, X.; Wei, Z.; Shen, P. Synthesis of coin-like hollow carbon and performance as Pd catalyst support for methanol electrooxidation. Electrochem. Commun. 2007, 9, 2473–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.S.; Zeng, J.; Chen, J.; Tan, S.; Liu, Y.; Kristian, N.; Wang, X. Synthesis of Hollow-Cone-like Carbon and Its Application as Support Material for Fuel Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2009, 156, B377–B380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, J. Core/Shell Pt/C Nanoparticles Embedded in Mesoporous Carbon as a Methanol-Tolerant Cathode Catalyst in Direct Methanol Fuel Cells. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.-S.; Antonietti, M.; Yu, S.-H. Hybrid “Golden Fleece”: Synthesis and Catalytic Performance of Uniform Carbon Nanofibers and Silica Nanotubes Embedded with a High Population of Noble-Metal Nanoparticles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007, 17, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, E.; Sanchis, I.; Coronella, C.J.; Mohedano, A.F. Activated Carbons from Hydrothermal Carbonization and Chemical Activation of Olive Stones: Application in Sulfamethoxazole Adsorption. Resources 2022, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, C.; Mohan, S.; Dinesha, P.; Rosen, M.A. CO2 adsorption by KOH-activated hydrochar derived from banana peel waste. Chem. Pap. 2024, 78, 3845–3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanti, R.F.; Wiratmadja, R.G.R.D.; Cleary Wanta, K.; Andreas Arie, A.; Kristianto, H. Zinc Chloride as a Catalyst in Hydrothermal Carbonization of Cocoa Pods Husk: Understanding the Effect of Different Carbonization Temperature and ZnCl2 Concentration. Period. Polytech. Chem. Eng. 2024, 68, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Shahbazi, A. A Review of Hydrothermal Carbonization of Carbohydrates for Carbon Spheres Preparation. Trends Renew. Energy 2015, 1, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Fu, H. Recent advances of biomass-derived carbon-based materials for efficient electrochemical energy devices. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 10373–10408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, S.; Huang, B.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Block Copolymers-Enabled Organic–Organic Assembly for Unique Carbonaceous Micro-/Nano-Structures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2410248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, D.; Raidongia, K.; Shao, J.; Huang, J. Graphene Oxide Assisted Hydrothermal Carbonization of Carbon Hydrates. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 4498–4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, L. Roles of Graphene Oxide in Hydrothermal Carbonization and Microwave Irradiation of Distiller’s Dried Grains with Solubles to Produce Supercapacitor Electrodes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 8433–8441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X. The Future of Graphene: Preparation from Biomass Waste and Sports Applications. Molecules 2024, 29, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Xiong, J.; Yu, Z.; Lu, X. Metal Stabilization of Metal-Supported Catalysts: Anchoring Strategies and Catalytic Applications in Carbon Resources Conversion. ChemCatChem 2025, 17, e00182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.-M.; Mo, C.-H.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Huang, W.-X.; Wong, M.H. Comparison of physicochemical properties of biochars and hydrochars produced from food wastes. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 117637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Jasrotia, K.; Singh, N.; Ghosh, P.; Srivastava, S.; Raj Sharma, N.; Singh, J.; Kanwar, R.; Kumar, A. A comprehensive review on hydrothermal carbonization of biomass and its applications. Chem. Afr. 2020, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.; Pandey, M.; Mishra, R.; Kumar, P. Adsorption potential of hydrochar derived from hydrothermal carbonization of waste biomass towards the removal of methylene blue dye from wastewater. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 15, 9229–9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshbouy, R.; Takahashi, F.; Yoshikawa, K. Preparation of high surface area sludge-based activated hydrochar via hydrothermal carbonization and application in the removal of basic dye. Environ. Res. 2019, 175, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, S.; Chen, J. A novel pyro-hydrochar via sequential carbonization of biomass waste: Preparation, characterization and adsorption capacity. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 176, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koottatep, T.; Fakkaew, K.; Tajai, N.; Polprasert, C. Isotherm models and kinetics of copper adsorption by using hydrochar produced from hydrothermal carbonization of faecal sludge. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2017, 7, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; Björkman, E.; Lilliestråle, M.; Hedin, N. Activated carbons prepared from hydrothermally carbonized waste biomass used as adsorbents for CO2. Appl. Energy 2013, 112, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanah, M.; Wijaya, A.; Arsyad, F.S.; Mohadi, R.; Lesbani, A. Preparation of Hydrochar from Salacca zalacca Peels by Hydrothermal Carbonization: Study of Adsorption on Congo Red Dyes and Regeneration Ability. Sci. Technol. Indones. 2022, 7, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, R.; Deen, M.A.; Narayanasamy, S. Performance analysis of hydrochar derived from catalytic hydrothermal carbonization in the multicomponent emerging contaminant systems: Selectivity and modeling studies. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 393, 130018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genli, N.; Kutluay, S.; Baytar, O.; Şahin, Ö. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon from hydrochar by hydrothermal carbonization of chickpea stem: An application in methylene blue removal by RSM optimization. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2022, 24, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, X.; Zhuang, X.; Li, B.; Xu, X.; Wei, Z.; Song, Y.; Jiang, E. Comparison of characterization and adsorption of biochars produced from hydrothermal carbonization and pyrolysis. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2018, 10, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanelli, E.; Vitolo, S.; Di Fidio, N.; Puccini, M. Tailoring the porosity of chemically activated carbons derived from the HTC treatment of sewage sludge for the removal of pollutants from gaseous and aqueous phases. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xue, G.; Chen, H.; Li, X. Magnetic biochar catalyst derived from biological sludge and ferric sludge using hydrothermal carbonization: Preparation, characterization and its circulation in Fenton process for dyeing wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2018, 191, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malghani, S.; Gleixner, G.; Trumbore, S.E. Chars produced by slow pyrolysis and hydrothermal carbonization vary in carbon sequestration potential and greenhouse gases emissions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 62, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malghani, S.; Jüschke, E.; Baumert, J.; Thuille, A.; Antonietti, M.; Trumbore, S.; Gleixner, G. Carbon sequestration potential of hydrothermal carbonization char (hydrochar) in two contrasting soils; results of a 1-year field study. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2014, 51, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titirici, M.-M.; Thomas, A.; Antonietti, M. Back in the black: Hydrothermal carbonization of plant material as an efficient chemical process to treat the CO2 problem? New J. Chem. 2007, 31, 787–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramke, H.-G.; Blöhse, D.; Lehmann, H.J. Hydrothermal carbonization of organic municipal solid waste-scientific and technical principles. Müll Abfall 2012, 9, 476–483. [Google Scholar]

- Berge, N.; Ro, K.; Mao, J.; Flora, J.; Chappell, M.; Bae, S. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Municipal Waste Streams. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 5696–5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Quek, A.; Kent Hoekman, S.; Balasubramanian, R. Production of solid biochar fuel from waste biomass by hydrothermal carbonization. Fuel 2013, 103, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.; Blöhse, D.; Ramke, H.G. Hydrothermal carbonization of agricultural residues. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 142, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Liu, H.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jiao, W. Immobilization of heavy metals in contaminated soils by modified hydrochar: Efficiency, risk assessment and potential mechanisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 685, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhrdanz, M.; Rebling, T.; Ohlert, J.; Jasper, J.; Greve, T.; Buchwald, R.; von Frieling, P.; Wark, M. Hydrothermal carbonization of biomass from landscape management—Influence of process parameters on soil properties of hydrochars. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 173, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Q.; Guo, X.; Zou, G.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Liu, B.; Sun, Q. Hydrochar reduces oxytetracycline in soil and Chinese cabbage by altering soil properties, shifting microbial community structure and promoting microbial metabolism. Chemosphere 2023, 338, 139578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Castro e Silva, H.; Robles Aguilar, A.; Akyol, Ç.; Luo, H.; Edayilam, N.; Meers, E. Hydrochars as Bio-based Fertilisers for Enhancing Biomass Growth: Insights into Phosphorus and Metals Dynamics. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 9290–9306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yin, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhu, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, K. Changes and release risk of typical pharmaceuticals and personal care products in sewage sludge during hydrothermal carbonization process. Chemosphere 2021, 284, 131313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, G.; Li, W.; Bao, S.; Li, Y.; Tan, W. Co-hydrothermal carbonization of agricultural waste and sewage sludge for product quality improvement: Fuel properties of hydrochar and fertilizer quality of aqueous phase. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 326, 116781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Zhao, C.; Wang, B.; Liang, X.; Gao, M.; Jiang, Z.; Yu, H.; Yang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Ogino, K.; et al. Liquid-solid ratio during hydrothermal carbonization affects hydrochar application potential in soil: Based on characteristics comparison and economic benefit analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 335, 117567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Luo, H.; Li, D.; Chen, Z.; Yang, S.; Liu, Z.; Yang, T.; Gai, C. Efficient immobilization of toxic heavy metals in multi-contaminated agricultural soils by amino-functionalized hydrochar: Performance, plant responses and immobilization mechanisms. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 261, 114217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alessandrino, L. Dynamic equilibrium and nutrients and metals release in sandy soils amended with hydrochar, lignite, and cactus powder. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2024, 79, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Chen, T.; Shan, Y.; Chen, K.; Ling, N.; Ren, L.; Qu, H.; Berge, N.; Flora, J.; Goel, R.; et al. Recycling food waste to agriculture through hydrothermal carbonization sustains food-energy-water nexus. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 496, 153710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, W.; Khan, A.; Jamal, A.; Radicetti, E.; Elsadek, M.F.; Ali, M.A.; Mancinelli, R. Optimizing Maize Productivity and Soil Fertility: Insights from Tillage, Nitrogen Management, and Hydrochar Applications. Land 2024, 13, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.Y.; Huang, W.-J. Production of silicon carbide liquid fertilizer by hydrothermal carbonization processes from silicon containing agricultural waste biomass. Eng. J. 2016, 20, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kong, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Xie, C.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, H.; Yu, X.; Yao, H.; Quan, Y.; You, X.; et al. Cattle manure hydrochar posed a higher efficiency in elevating tomato productivity and decreasing greenhouse gas emissions than plant straw hydrochar in a coastal soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 168749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Feng, Y.; Wang, N.; Petropoulos, E.; Li, D.; Yu, S.; Xue, L.; Yang, L. Win-win: Application of sawdust-derived hydrochar in low fertility soil improves rice yield and reduces greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 748, 142457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.-Y.; Huang, W.-J. Hydrothermal biorefinery of spent agricultural biomass into value-added bio-nutrient solution: Comparison between greenhouse and field cropping data. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 126, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Jiang, H.; Xie, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, P.; Liu, X.; Li, D. Nutrient recovery from biogas slurry via hydrothermal carbonization with different agricultural and forestry residue. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 189, 115891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, D.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, Z. Applying Hydrochar Affects Soil Carbon Dynamics by Altering the Characteristics of Soil Aggregates and Microbes. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puccini, M.; Stefanelli, E.; Hiltz, M.; Seggiani, M.; Vitolo, S. Activated Carbon from Hydrochar Produced by Hydrothermal Carbonization of Wastes. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017, 57, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plavniece, A.; Dobele, G.; Volperts, A.; Zhurinsh, A. Hydrothermal Carbonization vs. Pyrolysis: Effect on the Porosity of Activated Carbon Materials. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, C.; Marco-Lozar, J.P.; Salinas-Torres, D.; Morallón, E.; Cazorla-Amorós, D.; Titirici, M.M.; Lozano-Castelló, D. Tailoring the porosity of chemically activated hydrothermal carbons: Influence of the precursor and hydrothermal carbonization temperature. Carbon 2013, 62, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Becker, G.; Faweya, N.; Rodriguez Correa, C.; Yang, S.; Xie, X.; Kruse, A. Fertilizer and activated carbon production by hydrothermal carbonization of digestate. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2018, 8, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, F.; Yánez, D.; Díaz-Robles, L.; Oyaneder, M.; Alejandro-Martín, S.; Zalakeviciute, R.; Romero, T. Valorizing Biomass Waste: Hydrothermal Carbonization and Chemical Activation for Activated Carbon Production. Biomass 2025, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ouadrhiri, F.; Abdu Musad Saleh, E.; Husain, K.; Adachi, A.; Hmamou, A.; Hassan, I.; Mostafa Moharam, M.; Lahkimi, A. Acid assisted-hydrothermal carbonization of solid waste from essential oils industry: Optimization using I-optimal experimental design and removal dye application. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Correa, C.; Ngamying, C.; Klank, D.; Kruse, A. Investigation of the textural and adsorption properties of activated carbon from HTC and pyrolysis carbonizates. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2018, 8, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Kang, K.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, S.; Wu, K.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; Liang, B. Green synthesis of high-performance activated carbon from biomass by coupling hydrothermal carbonization and pyrolysis self-activation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 237, 122209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.-J.; Weinberg, G.; Liu, X.; Timpe, O.; Schlögl, R.; Su, D. Nanoarchitecturing of Activated Carbon: Facile Strategy for Chemical Functionalization of the Surface of Activated Carbon. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 3613–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unur, E. Functional nanoporous carbons from hydrothermally treated biomass for environmental purification. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 168, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, M.; Maciá-Agulló, J. Hydrothermal carbonization of biomass as a route for the sequestration of CO2: Chemical and structural properties of the carbonized products. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 3152–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadikolaei, N.F.; Kowsari, E.; Balou, S.; Moradi, A.; Taromi, F.A. Preparation of porous biomass-derived hydrothermal carbon modified with terminal amino hyperbranched polymer for prominent Cr(VI) removal from water. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 288, 121545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohzadi, S.; Marzban, N.; Godini, K.; Amini, N.; Maleki, A. Effect of Hydrochar Modification on the Adsorption of Methylene Blue from Aqueous Solution: An Experimental Study Followed by Intelligent Modeling. Water 2023, 15, 3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Xie, W.; Han, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Enhanced adsorption of Pb(II) onto modified hydrochar by polyethyleneimine or H3PO4: An analysis of surface property and interface mechanism. Colloids Surf. A 2019, 583, 123962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, T.; Dwivedi, P.; Krishnan, V. Acid functionalized hydrochar as heterogeneous catalysts for solventless synthesis of biofuel precursors. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 898–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyniuk, A.; Likozar, B. Wet torrefaction of biomass waste into high quality hydrochar and value-added liquid products using different zeolite catalysts. Renew. Energy 2024, 227, 120509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.Y.; Choi, J.W.; Jung, K.W. Synergistic effect in simultaneous removal of cationic and anionic heavy metals by nitrogen heteroatom doped hydrochar from aqueous solutions. Chemosphere 2023, 323, 138269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, M.; Yue, H.; Brun, N.; Ellis, G.J.; Naffakh, M.; Shuttleworth, P.S. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Biomass for Electrochemical Energy Storage: Parameters, Mechanisms, Electrochemical Performance, and the Incorporation of Transition Metal Dichalcogenide Nanoparticles. Polymers 2024, 16, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Chi, M.; Bai, L.; Liu, J.; Wen, X. Structure–tuned, phosphorus–doped hierarchical porous biochar via green hydrothermal carbonization and activation for formaldehyde adsorption. Fuel 2026, 404, 136381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustamaji, H.; Prakoso, T.; Devianto, H.; Widiatmoko, P.; Febriyanto, P.; Eviani, M. Modification of hydrochar derived from palm waste with thiourea to produce N, S co-doped activated carbon for supercapacitor. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2024, 7, 100132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Zhou, X.; Leghari, A.; Akram, M.S.; Zeb, H.; Ali, M.F.; Kashif Javed, M.; Wang, M.; Nawaz, M.A. Catalyzed hydrothermal carbonization of sewage sludge: Structural modification of hydrochar and its derived selective pyrolytic product distribution. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 43905–43921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Mora, A.; Diaz de Tuesta, J.L.; Pariente, M.I.; Segura, Y.; Puyol, D.; Castillo, E.; Lissitsyna, K.; Melero, J.A.; Martínez, F. Chemically activated hydrochars as catalysts for the treatment of HTC liquor by catalytic wet air oxidation. Catal. Today 2024, 429, 114462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, C.; Dodson, J.; Pinto, B.; Fernandes, D. Sustainable acid catalyst from the hydrothermal carbonization of carrageenan: Use in glycerol conversion to solketal. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2021, 13, 12009–12019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciceri, G.; Hernández Latorre, M.; Mediboyina, M.K.; Murphy, F. Hydrothermal Carbonization (HTC): Valorisation of Organic Wastes and Sludges for Hydrochar Production and Biofertilizers; Task 36; IEA Bioenergy: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, S.; Nawaz, T.; Beaudry, J. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Recovery from Wastewater. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2015, 1, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farru, G.; Scheufele, F.; Paniagua, D.M.; Keller, F.; Jeong, C.; Basso, D. Business and Market Analysis of Hydrothermal Carbonization Process: Roadmap toward Implementation. Agronomy 2024, 14, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals Report. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Padhye, L.P.; Bandala, E.R.; Wijesiri, B.; Goonetilleke, A.; Bolan, N. Hydrochar: A Promising Step Towards Achieving a Circular Economy and Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Process Eng. 2022, 4, 867228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavali, M.; Dresch, A.P.; Belli, I.M.; Libardi Junior, N.; Woiciechowski, A.L.; Soares, S.R.; Castilhos Junior, A.B.d. Hydrothermal carbonization—A critical overview of its environmental and economic sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 491, 144838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; He, J.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Xie, M.; Xu, Y.; Bie, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.g.; Sevilla, M.; et al. Towards Negative Emissions: Hydrothermal Carbonization of Biomass for Sustainable Carbon Materials. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2307412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Lee, G.; Kang, D. Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions in Urban Wastewater Treatment Facilities: A Case Study of Seoul Metropolitan City (SMC). Water 2025, 17, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Bin Abu Sofian, A.D.A.; Chan, Y.J.; Chakrabarty, A.; Selvarajoo, A.; Abakr, Y.; Show, P. Hydrothermal carbonization: Sustainable pathways for waste-to-energy conversion and biocoal production. GCB Bioenergy 2024, 16, e13150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Circular Economy: Definition, İmportance and Benefits. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/pdfs/news/expert/2023/5/story/20151201STO05603/20151201STO05603_en.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Neves, S.A.; Marques, A.C. Drivers and barriers in the transition from a linear economy to a circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 341, 130865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunleye, A.; Flora, J.; Berge, N. Life Cycle Assessment of Hydrothermal Carbonization: A Review of Product Valorization Pathways. Agronomy 2024, 14, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, M.; Novera, T.M.; Tabassum, M.; Islam, M.; Islam, M.A.; Hameed, B. Co-hydrothermal carbonization of different feedstocks to hydrochar as potential energy for the future world: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Pei, X.; Zhang, X.; Du, H.; Ju, L.; Li, S.; Chen, L.; Zhang, J. Advancing Hydrothermal Carbonization: Assessing Hydrochar’s Role and Challenges in Carbon Sequestration. Environ. Res. 2025, 270, 121023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Wu, J.; Li, H.; Karasev, A.; Ning, X.; Wang, C. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Biomass Waste for Solid Biofuel Production: Hydrochar Characterization and Its Application in Blast Furnace Injection. Recycling 2025, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariuzza, D.; Lin, J.-C.; Volpe, M.; Fiori, L.; Ceylan, S.; Goldfarb, J. Impact of Co-Hydrothermal carbonization of animal and agricultural waste on hydrochars’ soil amendment and solid fuel properties. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 157, 106329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bona, D.; Bertoldi, D.; Borgonovo, G.; Mazzini, S.; Ravasi, S.; Silvestri, S.; Zaccone, C.; Giannetta, B.; Tambone, F. Evaluating the potential of hydrochar as a soil amendment. Waste Manag. 2023, 159, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypczak, D.; Mironiuk, M.; Witek-Krowiak, A.; Mikula, K.; Pstrowska, K.; Łużny, R.; Mościcki, K.; Pawlak-Kruczek, H.; Siarkowska, A.; Moustakas, K.; et al. Innovative fertilizers and soil amendments based on hydrochar from brewery waste. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2024, 26, 1571–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; He, M.; Dutta, S.; Luo, G.; Zhang, S.; Tsang, D. Hydrothermal carbonization and liquefaction for sustainable production of hydrochar and aromatics. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhusudhan, A.; Zelenka, T.; Satrapinskyy, L.; Roch, T.; Gregor, M.; Cheng, P.; Monfort, O. A comparative study of different activation methods for hydrochar: Surface properties and removal of pharmaceutical pollutant in water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 18107–18120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbero, F.; Destro, E.; Bellone, A.; Di Lorenzo, L.; Brunella, V.; Perrone, G.; Damin, A.; Fenoglio, I. Hydrothermal carbonization synthesis of amorphous carbon nanoparticles (15–150 nm) with fine-tuning of the size, bulk order, and the consequent impact on antioxidant and photothermal properties††Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. Nanoscale Adv. 2025, 7, 1391–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevan, E.; Fu, J.; Luberti, M.; Zheng, Y. Challenges and opportunities of hydrothermal carbonisation in the UK; case study in Chirnside. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 34870–34897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Ma, X.; Peng, X.; Yu, Z.; Fang, S.; Lin, Y.-B. Combustion, pyrolysis and char CO2-gasification characteristics of hydrothermal carbonization solid fuel from municipal solid wastes. Fuel 2016, 181, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owsianiak, M.; Ryberg, M.W.; Renz, M.; Hitzl, M.; Hauschild, M.Z. Environmental Performance of Hydrothermal Carbonization of Four Wet Biomass Waste Streams at Industry-Relevant Scales. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 6783–6791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, T. Advances in Hydrothermal Carbonization for Biomass Wastewater Valorization: Optimizing Nitrogen and Phosphorus Nutrient Management to Enhance Agricultural and Ecological Outcomes. Water 2025, 17, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, S.M.; Pradhan, R.; Thimmanagari, M.; Dutta, A. Supply chain design of biocarbon production from Miscanthus through hydrothermal carbonization in southern Ontario: A life cycle assessment perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 513, 145758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Xu, Q.; Abou-Elwafa, S.; Alshehri, M.; Zhang, T. Hydrothermal Carbonization Technology for Wastewater Treatment under the “Dual Carbon” Goals: Current Status, Trends, and Challenges. Water 2024, 16, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management–Life Cycle Assessment–Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044:2006; Environmental Management-Life Cycle Assessment-Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Germirli Babuna, F.; Baş, B.; Atılgan Türkmen, B.; Elginöz Kanat, N. Türk Endüstrisi için Temiz Üretim ve Yaşam Döngüsü Değerlendirmesi Örnekleri. Çevre İklim Ve Sürdürülebilirlik 2023, 24, 55–64. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11411/9662 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Azapagic, A. Life cycle assessment and its application to process selection, design and optimisation. Chem. Eng. J. 1999, 73, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.; Bhandari, R.; Gäth, S. Critical review on life cycle assessment of conventional and innovative waste-to-energy technologies. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 672, 708–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarino, G.; Caffaz, S.; Gori, R.; Lombardi, L. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Hydrothermal Carbonization of Sewage Sludge and Its Products Valorization Pathways. Waste Biomass Valorization 2022, 13, 3845–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owsianiak, M.; Fozer, D.; Chrzanowski, Ł.; Renz, M.; Nowacki, B.; Ryberg, M. Evaluation of hydrothermal carbonization of biomass residues for bioenergy: A life-cycle based comparison against incumbent technologies. EFB Bioeconomy J. 2024, 4, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Qi, S.; Wang, R.; Li, H.; Song, G.; Li, H.; Yin, Q. Life cycle assessment of food waste energy and resource conversion scheme via the integrated process of anaerobic digestion and hydrothermal carbonization. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 52, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yay, A.; Birinci, B.; Açıkalın, S.; Yay, K. Hydrothermal carbonization of olive pomace and determining the environmental impacts of post-process products. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 315, 128087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, M.; Recchia, L.; Wray, H.E.; Dijkstra, J.W.; Nanou, P. Environmental Assessment of Hydrothermal Treatment of Wet Bio-Residues from Forest-Based and Agro-Industries into Intermediate Bioenergy Carriers. Energies 2024, 17, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Martos, E.; Istrate, I.; Villamil, J.; Gálvez-Martos, J.-L.; Dufour, J.; Mohedano, Á. Techno-economic and life cycle assessment of an integrated hydrothermal carbonization system for sewage sludge. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 122930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.F.; Abrar, M.F.; Tithi, S.S.; Kabir, K.B.; Kirtania, K. Life cycle assessment of hydrothermal carbonization of municipal solid waste for waste-to-energy generation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.-Y.; Chen, X.; Jiang, H. A Life Cycle Assessment of the Combined Utilization of Biomass Waste-Derived Hydrochar as a Carbon Source and Soil Remediation. ACS EST Eng. 2023, 3, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangaré, D.; Moscosa-Santillan, M.; Aragón Piña, A.; Bostyn, S.; Belandria, V.; Gökalp, I. Hydrothermal carbonization of biomass: Experimental study, energy balance, process simulation, design, and techno-economic analysis. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 2561–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, A.; McGaughy, K.; Reza, M.T. Techno-Economic Assessment of Co-Hydrothermal Carbonization of a Coal-Miscanthus Blend. Energies 2019, 12, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrinzi, D.; Ferrentino, R.; Baù, E.; Fiori, L.; Andreottola, G. Sewage Sludge Management at District Level: Reduction and Nutrients Recovery via Hydrothermal Carbonization. Waste Biomass Valorization 2023, 14, 2505–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, P.; Stampone, N.; Di Giacomo, G. Evolution and Prospects of Hydrothermal Carbonization. Energies 2023, 16, 3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucian, M.; Fiori, L. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Waste Biomass: Process Design, Modeling, Energy Efficiency and Cost Analysis. Energies 2017, 10, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.; Nadeem, A.; Choe, K. A Review of Upscaling Hydrothermal Carbonization. Energies 2024, 17, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, M.; Dutta, A.; Acharya, B.; Mahmud, S. A review of the current knowledge and challenges of hydrothermal carbonization for biomass conversion. J. Energy Inst. 2019, 92, 1779–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ender, T.; Ekanthalu, V.S.; Jalalipour, H.; Sprafke, J.; Nelles, M. Process Waters from Hydrothermal Carbonization of Waste Biomasses like Sewage Sludge: Challenges, Legal Aspects, and Opportunities in EU and Germany. Water 2024, 16, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccariello, L.; Battaglia, D.; Morrone, B.; Mastellone, M. Hydrothermal Carbonization: A Pilot-Scale Reactor Design for Bio-waste and Sludge Pre-treatment. Waste Biomass Valorization 2022, 13, 3865–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ischia, G.; Fiori, L. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Organic Waste and Biomass: A Review on Process, Reactor, and Plant Modeling. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 12, 2797–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sun, H.; Wu, S.; Pan, S.; Cui, D.; Wu, D.; Xu, F.; Wang, Z. Production of biomass-based carbon materials in hydrothermal media: A review of process parameters, activation treatments and practical applications. J. Energy Inst. 2023, 110, 101357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Carvalho, N.T.; Silveira, E.A.; de Paula Protásio, T.; Mendoza-Martinez, C.; Bianchi, M.L.; Trugilho, P.F. Optimizing catalytic hydrothermal carbonization of Eucalyptus grandis sawdust for enhanced biomass energy production: Statistical analysis and insights of sustainable carbon-neutral pathways. Energy 2025, 317, 134647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, I.; Na, R.; Kushima, K.; Shimizu, N. Investigating the Effect of Processing Parameters on the Products of Hydrothermal Carbonization of Corn Stover. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, L.; Zhu, M.; Sun, G.; Zhang, T.; Kang, K. Comparative Evaluation of Hydrothermal Carbonization and Low Temperature Pyrolysis of Eucommia ulmoides Oliver for the Production of Solid Biofuel. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devnath, B.; Khanal, S.; Shah, A.; Reza, T. Influence of Hydrothermal Carbonization (HTC) Temperature on Hydrochar and Process Liquid for Poultry, Swine, and Dairy Manure. Environments 2024, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslan, S.Z.; Zainudin, S.; Aris, A.M.; Chin, K.B.; Musa, M.; Daud, A.M.; Hassan, S.S. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Sewage Sludge into Solid Biofuel: Influences of Process Conditions on the Energetic Properties of Hydrochar. Energies 2023, 16, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, M.; Goldfarb, J.; Fiori, L. Hydrothermal carbonization of Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes: Role of process parameters on hydrochar properties. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ischia, G.; Berge, N.D.; Bae, S.; Marzban, N.; Román, S.; Farru, G.; Wilk, M.; Kulli, B.; Fiori, L. Advances in Research and Technology of Hydrothermal Carbonization: Achievements and Future Directions. Agronomy 2024, 14, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biomass (Feedstock) | Temperature (°C) | Time (min.) | Solid/Liquid Ratio | Fixed Carbon (wt.%) | Ash (%) | Carbon Content (wt.%) | HHV (MJ kg−1) | Surface Area (m2/g) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial digestate (IDT) | 200–240 | 10–60 | 1:4–1:10 | 1.80–4.60 | 52.80–64.20 | 20.50–27.50 | 9.70–13.10 | 5–22 | [42] |

| Sugarcane residues | 200–240 | 80–240 | 1:10–1:8 | 18.00–35.00 (%) | 12.00 | - | 21.43–24.94 | 9 | [43] |

| Potato peel (organic and mineral acid) | 180 | 300 | 1:6 | - | 0.09–1.70 | 58.60–72.40 | 22.00–29.80 | - | [44] |

| Antibiotic fermentation residues | 120–270 | 45 | 1:10 | - | 6.80 | - | 24.50 | - | [45] |

| Potato peel waste | 150–220 | 60–300 | 1:10 | - | - | 42.95–44.65 | - | - | [46] |

| Medical waste (MW) | 240–280 | 45 | 1:10 | 5.90 | - | 78.90 | 38.99 | - | [47] |

| Chenopodium botrys | 150–180 | 360–600 | 1:10 | - | - | - | - | 13–59 | [48] |

| Sorghum | 180–240 | 30–240 | 1:10 | - | 3.50–4.00 | 49.10–60.50 | 20.20–25.20 | - | [49] |

| Sago (Metroxylon spp) | 200–300 | 60 | 1:50 | 11.30–26.42 | 1.00–2.40 | 38.54–53.55 | 19.48–23.88 | 4–180 | [50] |

| Brewer’s spent grain (BSG) | 220–280 | 60 | 1:5 | 23.14–27.07 | 1.72–2.28 | 61.32–66.91 | 34.70–35.36 | - | [51] |

| Traditional Chinese medicine residue | 200–250 | 240–720 | 1:5 | 37.32–43.90 | 3.74–4.38 | 60.78–70.81 | 20.36–25.12 | - | [52] |

| Waste coir substrate | 180–300 | 60 | 1:5 | 36.12–47.94 | 4.59–8.19 | 51.95–70.32 | 19.55–24.93 | - | [53] |

| Stevia rebaudiana | 185–275 | 30–90 | 1:10 | 20.79–34.27 | 1.68–6.72 | 62.11–75.59 | 26.95–36.61 | - | [54] |

| Colombian plantain peels | 150–230 | 120–240 | 1:1–1:6 | - | - | - | - | - | [55] |

| Olive stone | 200–240 | 120–600 | 1:10–1:20 | 27.3–39.10 | 0.56–1.02 | 50.13–57.53 | 20.04–23.00 | - | [56] |

| Corn stalk | 180–300 | 20–80 | 1:4 | - | - | 71.87–80.52 | 22.03–22.45 | - | [57] |

| Woodchip (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O) | 240 | 60 | 1:4 | 42.95–44.31 | - | - | 22.10–30.05 | - | [58] |

| Swine manure | 200–280 | 0–60 | 1:20–1:4 | 8.60–15.70 | 36.10–48.90 | 27.40–37.40 | 10.90–16.00 | - | [59] |

| Banana stalk | 160–200 | 60–180 | 1:10 | 5.00–44.30 | 6.70–19.00 | 33.00–48.50 | 15.60–18.90 | - | [60] |

| Tobacco stalk | 180–260 | 60–720 | 1:10 | 15.19–48.75 | 3.05–7.49 | 46.22–65.24 | 18.78–27.18 | 1–11 | [61] |

| Food waste (Acetic acid) | 180–260 | 120–360 | 2:10–1:10 | 11.78–38.81 | 2.97–6.59 | 43.89–72.88 | 18.05–32.56 | - | [62] |

| Feedstock and Conditions | Structural and Chemical Features | Elemental Composition | Key Findings | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cotton stalks 180–240 °C, 4 h, 1:10 (w/v) | Increasing temperature reduced yield but enhanced carbonization and fuel quality. | C content increased while H/C and O/C ratios declined, indicating stronger carbonization and aromaticity. | Higher T improved fuel quality but reduced yield. | [63] |

| Dairy manure (DM) Microwave-assisted HTC at 180–260 °C, 0.5–14 h, | Higher T increased C and HHV, reduced O, and enhanced carbonization and energy density. | Rising T and time enhanced dehydration–deoxygenation, increasing carbon content and energy efficiency. | Microwave-assisted HTC enhanced carbonization and porosity, yielding mesoporous microspheres and graphene-like sheets. | [64] |

| Forest waste (FW) 200–280 °C, 1 h, 1:5 (w/v) | Porosity and surface area increased then declined with T due to pore collapse. Rising T caused dehydration decarboxylation, loss of –OH/C=O groups, and partial lignin decomposition. | Fixed carbon rose 14.9 → 45.1%, carbon 47.9 → 70.8%, O and H decreased; H/C ↓ and O/C ↓, showing enhanced carbonization and coalification. | Elevated T produced energy-dense, stable hydrochar with improved carbon order despite lower yield | [65] |

| Low-rank coal 250–340 °C, 1 h, 1:2 (w/w) | BET surface area declined and pores enlarged due to collapse. Aliphatic chains shortened, aromaticity increased, and oxygenated groups diminished. | Carbonization increased (C, FC↑; O, O/C, H/C↓), improving coal rank and energy density | Higher T promoted carbonization, aromatization, and impurity removal, yielding stable, low-volatile HTC coal. | [66] |

| Cocoa bean shell residues 180 °C; 24 h; 1:5 (w/w) | HTC E showed highest surface area and mesoporosity. Dehydration, decarboxylation reduced –OH/C=O groups and formed aromatic C=C; activation enhanced porosity and induced N-doping. | C content increased and O, H/C, O/C ratios decreased, indicating strong carbonization | HTC activation enhanced aromatization and pore formation; ethanol increased C, and water enlarged pores | [67] |

| Food waste digestate solids ( 220–260 °C; 30–60 min; 1:1 (w/w) | Color darkened, and pore collapse occurred with higher T. Dehydration, decarboxylation weakened –OH/C=O bands, indicating cellulose degradation and increased aromaticity. | Higher T enriched carbon and lowered O/C–H/C ratios, evidencing coalification and aromatic carbon growth. | Higher T reduced yield but improved HHV and stability; N moved to liquid, P retained as apatite. | [68] |

| Microalgae + corn stalk 200–280 °C, 120 min, | FeCl3/NH4Cl increased surface area; melamine reduced porosity. Dehydration, aromatization dominated; Fe3+ promoted deamination, and NH4Cl/melamine induced amidation without triazine residues. | C↑ (61.8–74.4%), O↓; NH4Cl yielded highest N (8.9%), FeCl3 the lowest. | FeCl3 promoted N migration to liquid; NH4Cl and melamine increased hydrochar N and yield via two stage transformation. | [69] |

| Jatropha curcas fruit residues 220 °C, 2 h, 10 wt % | Particle density increased (up to 1.64 g cm−3); pore evolution was governed by lignin and size. Dehydration, decarboxylation weakened –OH/C–O bands, forming aromatic, hydrophobic hydrochars. | C ↑ (50.7→61.9%), O ↓ (37.8→29.1%); H/C ↓ (0.13 → 0.10 approx.); O/C ↓ (0.56→0.33). FHK: lower C gain (max 12%); SSH: +20%. | SSH showed higher yield, HHV, and ED than FHK; smaller particles enhanced ash reduction and mineral leaching | [70] |

| Chlorella vulgaris biomass 180–250 °C; 0.5–4 h; 1:100; | Carbon densification doubled with higher T; fixed C↑, volatiles↓, ash↑. Dehydration, decarboxylation reduced –OH/C–O and enhanced C=C, C=O, yielding aromatic, hydrophobic hydrochars (optimum at 210 °C) | C↑ (27.4→~60%), O↓ (59.7→25–40%), H/C and O/C↓; condensation and aromatization enhanced carbonization. | Yield ↓, HHV ↑ (~2×), energy yield ≤ 76.6%. Higher ignition T improved safety; nutrient-rich aqueous phase supported 92% microalgae regrowth. | [71] |

| Pig manure 200 °C and 240 °C, 3 h, 1:10 | Mg citrate enhanced pore formation and fiber opening, reduced ash (↓ 4–20%), and increased C (+2–19%). Dehydration, decarboxylation intensified aromatic C=C and C–O bands; Mg–O and Si–O–Mg structures formed. | C↑ (+19%), ash and O/C–H/C↓, indicating enhanced aromatization and structural stability. | Mg citrate improved N/P retention and struvite recovery (>90% N, >85% P), enhancing hydrolysis, stabilization, and economic yield. | [72] |

| Dominico Harton plantain peels 150–230 °C, 2–4 h, | Increasing T formed denser, porous hydrochars; FC↑, VM↓, ash↓, ED = 1.69. Dehydration–decarboxylation dominated, generating furfural/5-HMF (190 °C) and phenolics (170–190 °C); aromatization intensified above 210 °C. | C↑, O and O/C–H/C↓, confirming enhanced aromaticity and structural stability | Yield↓ with T; high C and ED indicate solid fuel potential; 210–230 °C gives optimal stability and efficiency. | [55] |

| Rice straw (RS), Wheat straw (WS), and Corn straw (CS) 180 °C and 260 °C; 1 h, 1:10 (w/v); | Temperature increase transformed fibrous structures into porous, microspherical carbon via polymerization and gas release. Enhanced dehydration and decarboxylation weakened –OH/C=O bands and strengthened aromatic C=C, indicating oxygen removal and aromatization. | C↑ and H/C–O/C↓ confirmed dehydration, deoxygenation; Van Krevelen indicated higher coalification and hydrophobicity. | HTC at 280 °C produced carbon-rich, aromatic hydrochar via dehydration, aromatization, suitable for energy conversion. | [73] |

| Styrofoam (SF) + Sawdust (SD) 180 °C, 200 °C, 220 °C; 60 min; 1:1 | Thermal analysis showed three degradation stages (≤ 233 °C, 200–386 °C, 445–598 °C) reflecting gradual carbon densification. FTIR confirmed dehydration–decarboxylation via weakened –OH/C=O and aromatic C–H bands, indicating increased aromaticity | Progressive C enrichment and O loss (↓H/C, O/C) enhanced carbonization, coalification, and hydrophobic character. | Co HTC improved HHV (28.8→29.8 MJ/kg), raised fixed carbon, and lowered ash. Water recirculation enhanced yield via polymerization and gas release effects | [74] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Durak, H.; Yarbay, R.Z.; Atilgan Türkmen, B. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Biomass for Hydrochar Production: Mechanisms, Process Parameters, and Sustainable Valorization. Processes 2026, 14, 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020339

Durak H, Yarbay RZ, Atilgan Türkmen B. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Biomass for Hydrochar Production: Mechanisms, Process Parameters, and Sustainable Valorization. Processes. 2026; 14(2):339. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020339

Chicago/Turabian StyleDurak, Halil, Rahmiye Zerrin Yarbay, and Burçin Atilgan Türkmen. 2026. "Hydrothermal Carbonization of Biomass for Hydrochar Production: Mechanisms, Process Parameters, and Sustainable Valorization" Processes 14, no. 2: 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020339

APA StyleDurak, H., Yarbay, R. Z., & Atilgan Türkmen, B. (2026). Hydrothermal Carbonization of Biomass for Hydrochar Production: Mechanisms, Process Parameters, and Sustainable Valorization. Processes, 14(2), 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020339