Distributionally Robust Optimization for Integrated Energy System with Tiered Carbon Trading: Synergizing CCUS with Hydrogen Blending Combustion

Abstract

1. Introduction

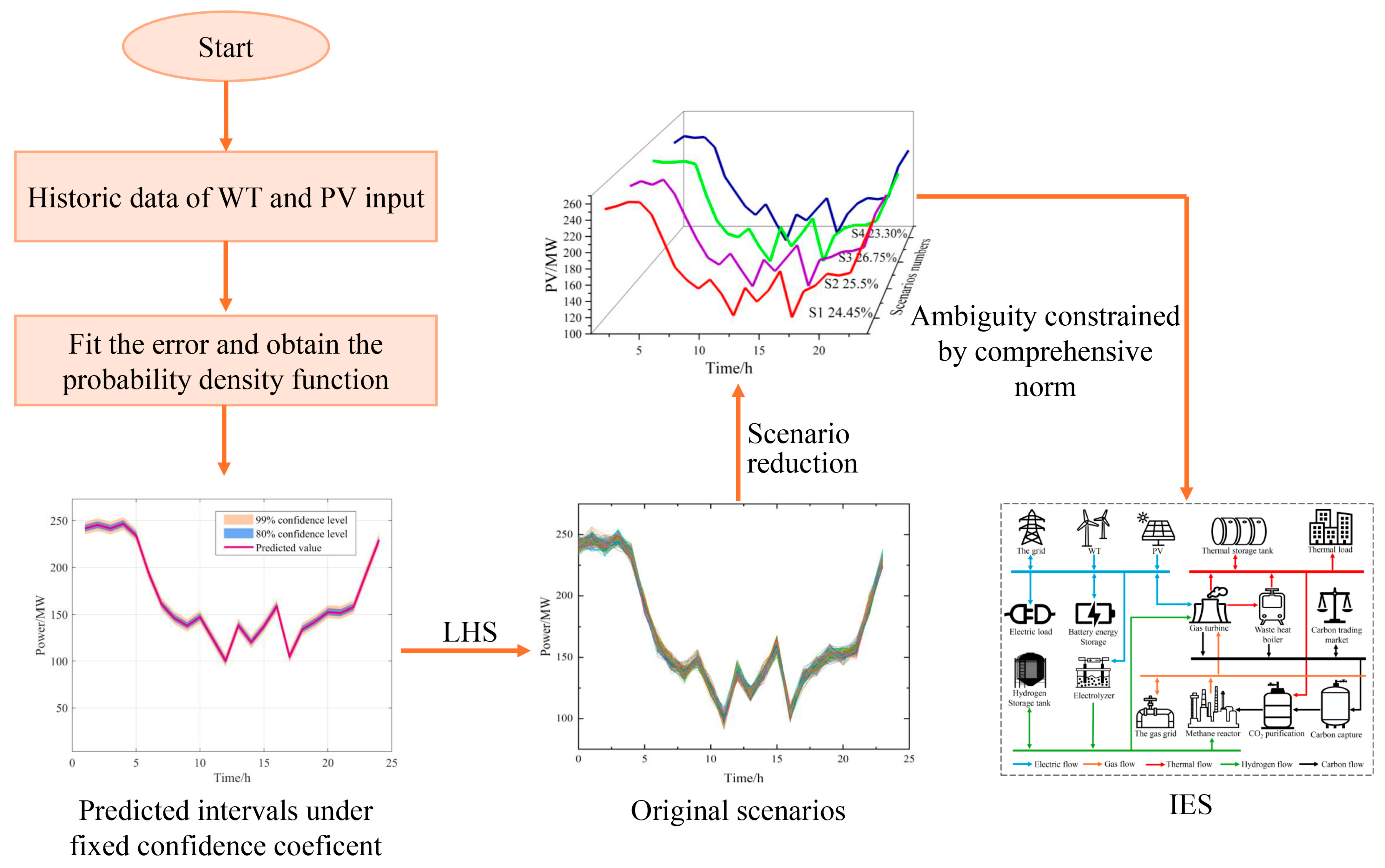

- To effectively handle the uncertainty of RE, a data-driven DRO approach is employed to maintain stability between economic performance and system robustness considering the WT and PV variability. A fuzzy set formulation based on KDE is proposed to handle this uncertainty.

- This paper introduces a model for the refined use of hydrogen generated by RE, encompassing blending combustion in CHP and gas synthesis using CCUS technology, as well as storage in tanks. This approach aims to improve the consumption rate of RE and enhance hydrogen utilization rates.

- A TCTM model is developed to further reduce CO2 emissions. The effects of related TCTM parameters, including transaction benchmark prices and growth ratios when the carbon trading range is fixed, on overall costs, CO2 emissions, and expenses of carbon trading expenses are thoroughly examined, offering guidance for selecting appropriate trading parameters.

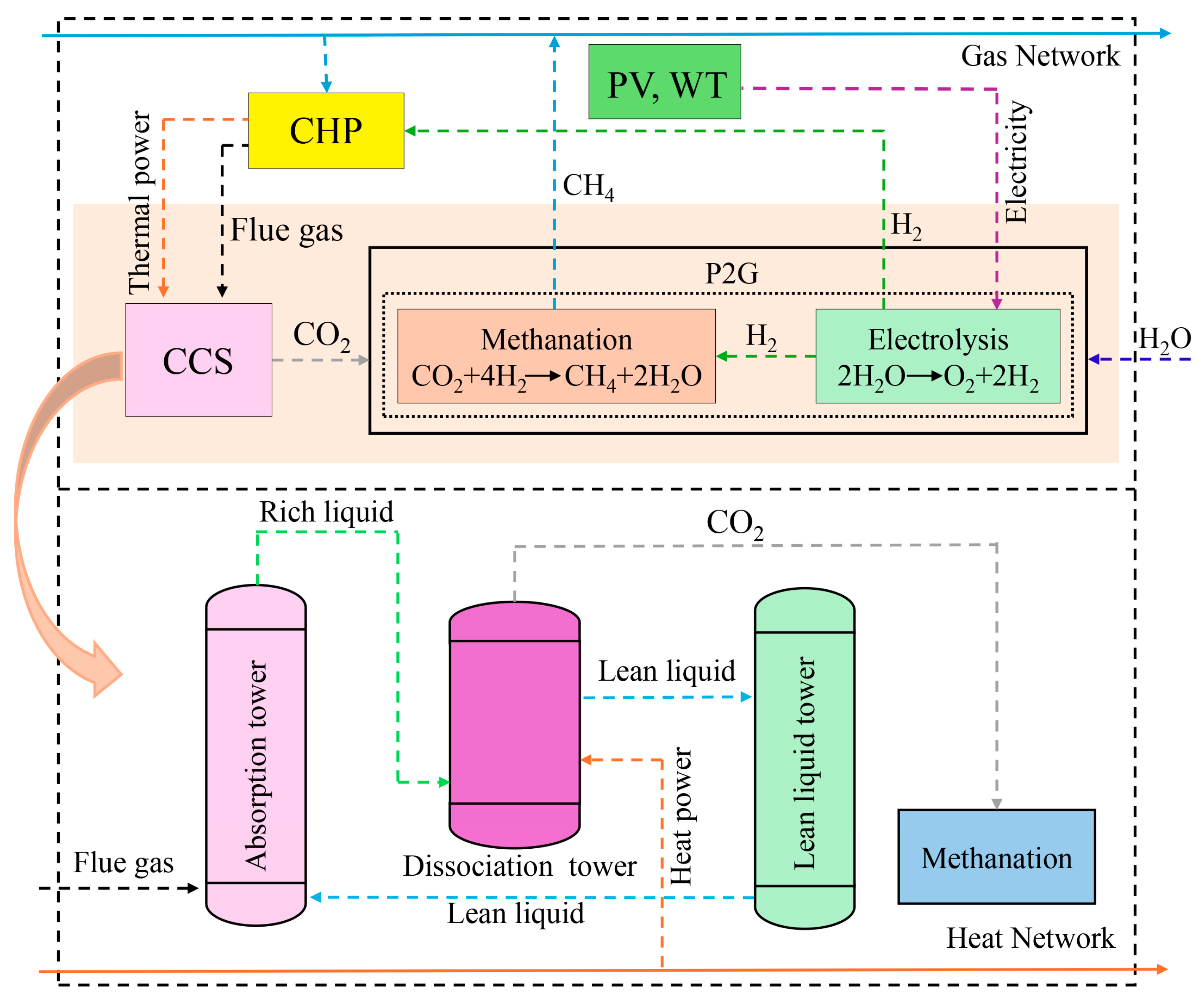

2. The Framework of the Proposed IES

2.1. Model of CHP with Flexible Hydrogen Blending Combustion and Thermoelectric Ratio

2.2. Model of Electrolysis (EL)

2.3. Model of Methanation Reaction (MR)

2.4. Model of Energy Storage

2.5. Model of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS)

2.6. Power Balance Constraints

2.6.1. Electric Power Constraints

2.6.2. Thermal Power Constraints

2.6.3. Hydrogen and Natural Gas Constraints

2.7. Model of Carbon Trading

2.7.1. Model of Allocated Carbon Emission Quota in System

2.7.2. Model of Actual Carbon Emission in System

2.7.3. Model of Tiered Carbon Trading Mechanism

3. Model of DRO in IES

4. Case Studies

4.1. Basic Data

4.2. Fuzzy Sets of RE

4.3. Optimization Scheduling Results

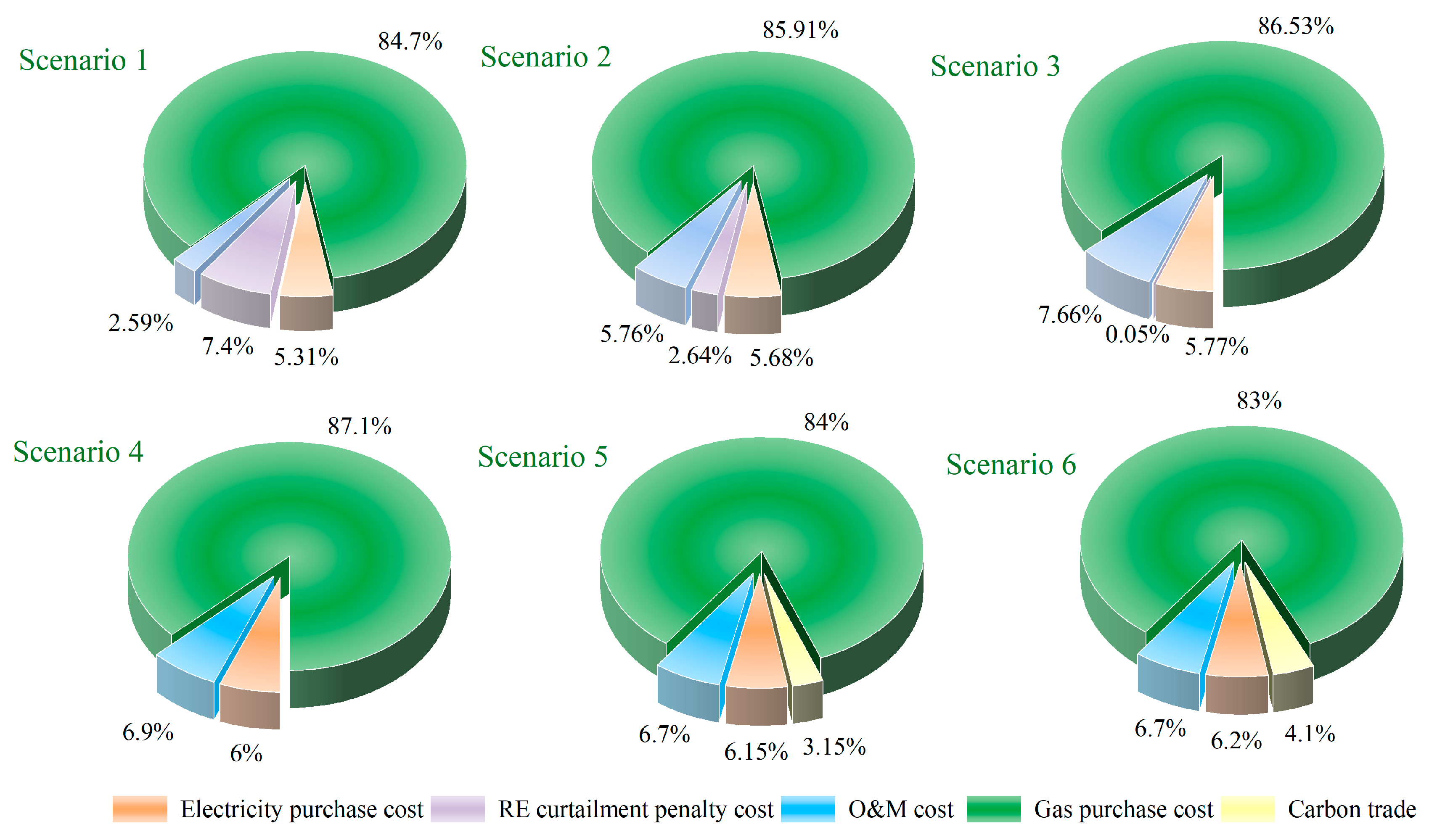

5. Further Discussion and Analysis

5.1. Comparative Analysis of Hydrogen Utilizations

5.2. Comparative Discussion of Carbon Trading Mechanism

5.3. Hydrogen Blending Combustion Rate of CHP Analysis

5.4. The Analysis of the Tiered Carbon Trading Mechanism Parameters

5.5. Comparison of Methods for Handling Uncertainty

6. Conclusions and Outlook

- Dealing with the uncertainty of the RE output, SP minimizes the expected cost under probabilistic scenarios and is typically more economical, but its scalability deteriorates as the number of scenarios grows. RO enforces worst-case feasibility over a prescribed uncertainty set, enhancing robustness at the expense of a higher operating cost. In contrast, DRO yields total costs between SP and RO, while achieving a better balance of the economy and robustness, making it well suited to address WT/PV uncertainty.

- Due to the upper limit of the hydrogen blend rate—using HBC alone with an RE utilization rate of about 93%—using hydrogen for methanation alone further raises RE utilization but drives up O&M costs sharply. Combining HBC with CCUS delivers the best overall performance: it achieves near-complete RE utilization and the lowest total cost. The joint deployment of HBC and CCUS offers the most favorable cost–emissions trade-off for the IES.

- A comparison between the TCTM and other carbon trading mechanisms demonstrates the former’s superior operational performance. Specifically, the TCTM and fixed-price trading reduce the carbon emissions of the system by approximately 3.4% and 2.4%, respectively. Moreover, we examined the impact of the TCTM parameters, like the carbon trading price and increasing rate, on CO2 emissions of the system. The suitable carbon trading parameters play a critical role in preventing a higher expenditure and weaker involvement of the carbon market.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCUS | Carbon capture, utilization, and storage | Hydrogen conversion efficiency of EL (%) | |

| CHP | Combined heat and power | PMR,h | Methanation conversion efficiency of MR (%) |

| DRO | Distributionally robust optimization | Methanation conversion efficiency of MR (%) | |

| ES | Energy storage | Charging efficiency of the ES (%) | |

| GT | Gas turbine | Discharging efficiency of ES (%) | |

| HBC | Hydrogen blending combustion | Output power of the PV (MW) | |

| IES | Integrated energy system | Output power of the WT (MW) | |

| TCTM | Tiered carbon trading mechanism | Electric load (MW) | |

| LHS | Latin hypercube sampling | Prices of purchasing electricity (CNY/MW) | |

| WHB | Waste heat boiler | External electricity procurement (MW) | |

| Parameters | |||

| Electricity output of GT (MW) | Ladder-type carbon trading cost (CNY) | ||

| Thermal output of WHB (MW) | Carbon trading base price (CNY/tons) | ||

| Output power of CHP (MJ) | Length of carbon emission interval (tons) | ||

| Hydrogen input of CHP (m3) | Growth rate of carbon trading prices (%) | ||

| Natural gas input of CHP (m3) | Prices of purchasing gas (CNY/m3) | ||

| Electricity input of EL (MW) | O&M price of device i (CNY/MW) | ||

| Hydrogen output of EL (MW) | Power output of device i (MW) | ||

| Hydrogen input of MR (MW) | |||

References

- Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Tanaka, K.; Ciais, P.; Penuelas, J.; Balkanski, Y.; Sardans, J.; Hauglustaine, D.; Cao, J.; Chen, J.; et al. Global spatiotemporal optimization of photovoltaic and wind power to achieve the Paris Agreement targets. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Tanaka, K.; Ciais, P.; Penuelas, J.; Balkanski, Y.; Sardans, J.; Hauglustaine, D.; Liu, W.; Xing, X.; et al. Accelerating the energy transition towards photovoltaic and wind in China. Nature 2023, 619, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bu, F.; Gao, J.; Li, G. Optimal dispatch of low-carbon integrated energy system considering nuclear heating and carbon trading. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 378, 134540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Lu, H.; Chang, X.; Liao, H. An optimization on an integrated energy system of combined heat and power, carbon capture system and power to gas by considering flexible load. Energy 2023, 273, 127203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Long, Z.; Liu, X.; Lee, K.Y. Distributionally robust optimization of electric–thermal–hydrogen integrated energy system considering source–load uncertainty. Energy 2025, 316, 134568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, R.; Gu, W.; Cao, G. N-1 Evaluation of Integrated Electricity and Gas System Considering Cyber-Physical Interdependence. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025, 16, 3728–3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Gao, H.; Wang, L.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, J. Distributionally robust planning for integrated energy systems incorporating electric-thermal demand response. Energy 2020, 213, 118783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Y. Day-ahead scheduling strategy for integrated heating and power system with high wind power penetration and integrated demand response: A hybrid stochastic/interval approach. Energy 2022, 253, 124189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Qian, F.; Sun, K.; Meng, H. Optimization on building combined cooling, heating, and power system considering load uncertainty based on scenario generation method and two-stage stochastic programming. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lu, X.; Zhou, K.; Shao, Z. Distributionally robust optimal dispatching method for integrated energy system with concentrating solar power plant. Renew. Energy 2024, 229, 120792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Song, J.; Li, Z.; Shui, S. Distributionally robust electricity-carbon collaborative scheduling of integrated energy systems based on refined joint model of heating networks and buildings. Renew. Energy 2025, 251, 123468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.G.; Kim, S.Y. Optimal planning and operation of integrated energy systems in South Korea: Introducing a Novel ambiguity set based distributionally robust optimization. Energy 2024, 307, 132503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, M.; Jia, M.; Li, B.; Fei, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Multi-objective distributionally robust optimization for hydrogen-involved total renewable energy CCHP planning under source-load uncertainties. Appl. Energy 2023, 342, 121212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqin, Z.; Niu, D.; Wang, X.; Zhen, H.; Li, M.; Wang, J. A two-stage distributionally robust optimization model for P2G-CCHP microgrid considering uncertainty and carbon emission. Energy 2022, 260, 124796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, M.; Jia, M.; Shi, L.; Li, B. TimeGAN based distributionally robust optimization for biomass-photovoltaic-hydrogen scheduling under source-load-market uncertainties. Energy 2023, 284, 128589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, D.; Guo, H.; Zhang, J. Distributionally Robust Optimization for integrated energy system accounting for refinement utilization of hydrogen and ladder-type carbon trading mechanism. Appl. Energy 2024, 367, 123391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Li, S.; Ma, X.; Zhang, C. A bi-level scheduling strategy for integrated energy systems considering integrated demand response and energy storage co-optimization. J. Energy Storage 2023, 66, 107508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Ren, J.; Yang, C.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Wu, Y. A three-stage optimization planning model for the integrated energy service station from the sustainable perspective of energy-transportation-information-humanities. Energy 2025, 332, 137145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Z. Low carbon economic scheduling model for a park integrated energy system considering integrated demand response, ladder-type carbon trading and fine utilization of hydrogen. Energy 2024, 290, 130311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.-L.; Li, Z.; Huang, X.; Li, K.; Zhang, X.; Lu, X.; Wu, J.; Hubacek, K.; Shen, B. A net-zero emissions strategy for China’s power sector using carbon-capture utilization and storage. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, Z.; Zheng, S. Coordinated scheduling of integrated electricity, heat, and hydrogen systems considering energy storage in heat and hydrogen pipelines. J. Energy Storage 2024, 85, 111034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, W.; Cho, S.; Lee, I. Carbon utilization in natural gas-based hydrogen production via carbon dioxide electrolysis: Towards cost-competitive clean hydrogen. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 314, 118719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, H.; Huang, Y.; Dong, H.; Qi, C.; Baptiste, N. Optimal design of integrated energy system considering economics, autonomy and carbon emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Liu, Y. Research on multi-energy collaborative operation optimization of integrated energy system considering carbon trading and demand response. Energy 2023, 283, 129117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wen, X.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Low carbon optimal operation of integrated energy system based on carbon capture technology, LCA carbon emissions and ladder-type carbon trading. Appl. Energy 2022, 311, 118664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Ma, G.; Li, X.; Guerrero, J.M. Low-Carbon Economic Dispatch Method for Integrated Energy System Considering Seasonal Carbon Flow Dynamic Balance. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2023, 14, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, Z.; Niu, X.; Li, S. Economic optimization scheduling of virtual power plants considering an incentive based tiered carbon price. Energy 2024, 305, 132080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Jiang, H.; Liu, C.; Kang, L.; Wang, C. Coordinated optimization scheduling operation of integrated energy system considering demand response and carbon trading mechanism. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 147, 108902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xu, Z.; He, J.; Dong, W.; Zhao, R.; Yan, J.; Zhong, Z.; Wu, Y. Multi-energy synergy and deep carbon emission reduction mechanism for steel enterprises based on deep learning and dynamic computable general equilibrium model. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 344, 120336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.; Zhang, C. Scheduling optimization of a wind power-containing power system considering the integrated and flexible carbon capture power plant and P2G equipment under demand response and reward and punishment ladder-type carbon trading. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2023, 128, 103955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liao, W. Long-term, multi-stage low-carbon planning model of electricity-gas-heat integrated energy system considering ladder-type carbon trading mechanism and CCS. Energy 2023, 280, 128113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, H.; Hong, F.; Yang, J.; Chen, Z.; Cui, H.; Feng, J. Modeling and optimization of combined heat and power with power-to-gas and carbon capture system in integrated energy system. Energy 2021, 236, 121392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wu, Z.; Shi, Z. Low carbon economic dispatch of integrated energy systems considering utilization of hydrogen and oxygen energy. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 158, 109923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Gu, W.; Zhou, S.; Yao, S.; Pan, G. Adaptive Robust Dispatch of Integrated Energy System Considering Uncertainties of Electricity and Outdoor Temperature. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 4691–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, S. Study on two-stage robust optimal configuration of integrated energy system considering CCUS and electric hydrogen production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 324, 119278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikulov, K.; Aminov, Z.; Anh, L.H.; Tran Dang, X.; Kim, W. Effect of ammonia and hydrogen blends on the performance and emissions of an existing gas turbine unit. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 61, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamodaran, G.; Venugopal, S.; Seetharaman, S.; Palsami, T. Comparative analysis of a diesel engine fueled with hydrogen-enriched nanoparticle-emulsified second-generation biodiesel. Fuel 2026, 409, 137851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushparani, D.S.; Varatharajan, K.; Nagarajan, P.K.; Gopinath, D.; Ganesan, S. Isolation and characterization of carbonic anhydrase enzyme from the Lantana camara plant leaves and its immobilization in polyurethane foam for carbon capture applications. Biocatal. Biotransform. 2025, 43, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.W.; He, H.; Barzagli, F.; Amer, M.W.; Li, C.E.; Zhang, R. Analysis of the energy consumption in solvent regeneration processes using binary amine blends for CO2 capture. Energy 2023, 270, 126903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Mirsaeidi, S.; He, J.; Pei, W. Multi-agent energy management optimization for integrated energy systems under the energy and carbon co-trading market. Appl. Energy 2022, 324, 119646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, K.; Yu, T.; Huang, L.; Yang, B.; Zhang, X. Decentralized optimal multi-energy flow of large-scale integrated energy systems in a carbon trading market. Energy 2018, 149, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Category | Technical Measure | TCTM Parameter Analysis | Uncertainty | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV | WT | Method | ||||

| [4,32] | Park-IES (kw) | CCS, P2G | × | × | × | × |

| [18] | Service station-IES (kw) | P2G | √ | √ | √ | SP |

| [3] | Park-IES (kw) | P2G | × | √ | √ | SP |

| [33] | Power plant-IES (MW) | P2G, HBC | √ | × | √ | SP |

| [34] | Resident-IES (kw) | × | × | √ | √ | RO |

| [35] | Industrial park-IES (MW) | CCS, P2G | × | √ | √ | Two stage-RO |

| [10] | Park-IES (kw) | × | × | × | √ | DRO |

| [5] | Park-IES (kw) | P2G, HBC | × | √ | √ | DRO |

| Proposed | Power plant-IES (MW) | CCS, P2G, HBC | √ | √ | √ | DRO |

| Scenarios | CCUS | HBC | Fixed-Price Carbon Trading | TCTM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | × | × | × | × |

| 2 | × | √ | × | × |

| 3 | √ | × | × | × |

| 4 | √ | √ | × | × |

| 5 | √ | √ | √ | × |

| 6 | √ | √ | × | √ |

| Category | Time/h | Unit Price CNY/MWh |

|---|---|---|

| Valley tariff | 22:00–5:00 | 295 |

| Parity tariff | 6:00–7:00 12:00–17:00 | 550 |

| Peak tariff | 8:00–11:00 18:00–21:00 | 804 |

| Valley tariff | 22:00–5:00 | 295 |

| Device | Charge and Discharge Efficiency | Storage Capacity/ MW | Lower Bound of Storage State | Upper Bound of Storage State |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EES | 0.9 | 150 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| TES | 0.9 | 150 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| HES | 0.9 | 200 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| CCS | 0.9 | 50 (tons) | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| EES | 0.9 | 150 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Equipment | Parameters | Values |

|---|---|---|

| GT | /MW | 100 |

| /MW | 350 | |

| 0.35 | ||

| WHB | /MW | 80 |

| /MW | 300 | |

| 0.9 | ||

| CHP | 0.95 | |

| [0, 0.2] | ||

| (0, 1) | ||

| [0.6, 3] | ||

| EL | /MW | 0 |

| /MW | 200 | |

| 0.88 | ||

| MR | /MW | 0 |

| /MW | 150 | |

| 0.65 |

| Equipment | O&M Values (CNY/MW) |

|---|---|

| GT | 25 |

| WHB | 18 |

| EES | 20 |

| TES | 12 |

| HES | 35 |

| CCS | 40 |

| EL | 40 |

| MR | 55 |

| PV/WT | 350 (punishment for abandoning RE cost, CNY/MWh) |

| Optimization Method | Total Costs/CNY | Amount of Carbon Emissions/Tons | Calculation Time/s |

|---|---|---|---|

| SP | 3,846,410.53 | 4213.54 | 786 |

| RO | 3,931,307.64 | 4507.74 | 34 |

| DRO | 3,854,222.94 | 4227.67 | 55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, M.; Mutailipu, M.; Wang, P.; Huang, J.; Xue, F.; Li, X. Distributionally Robust Optimization for Integrated Energy System with Tiered Carbon Trading: Synergizing CCUS with Hydrogen Blending Combustion. Processes 2026, 14, 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020328

Huang M, Mutailipu M, Wang P, Huang J, Xue F, Li X. Distributionally Robust Optimization for Integrated Energy System with Tiered Carbon Trading: Synergizing CCUS with Hydrogen Blending Combustion. Processes. 2026; 14(2):328. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020328

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Mingyao, Meiheriayi Mutailipu, Peng Wang, Jun Huang, Fusheng Xue, and Xiaofeng Li. 2026. "Distributionally Robust Optimization for Integrated Energy System with Tiered Carbon Trading: Synergizing CCUS with Hydrogen Blending Combustion" Processes 14, no. 2: 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020328

APA StyleHuang, M., Mutailipu, M., Wang, P., Huang, J., Xue, F., & Li, X. (2026). Distributionally Robust Optimization for Integrated Energy System with Tiered Carbon Trading: Synergizing CCUS with Hydrogen Blending Combustion. Processes, 14(2), 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020328