A Machine Learning Approach for the Completion, Augmentation and Interpretation of a Survey on Household Food Waste Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

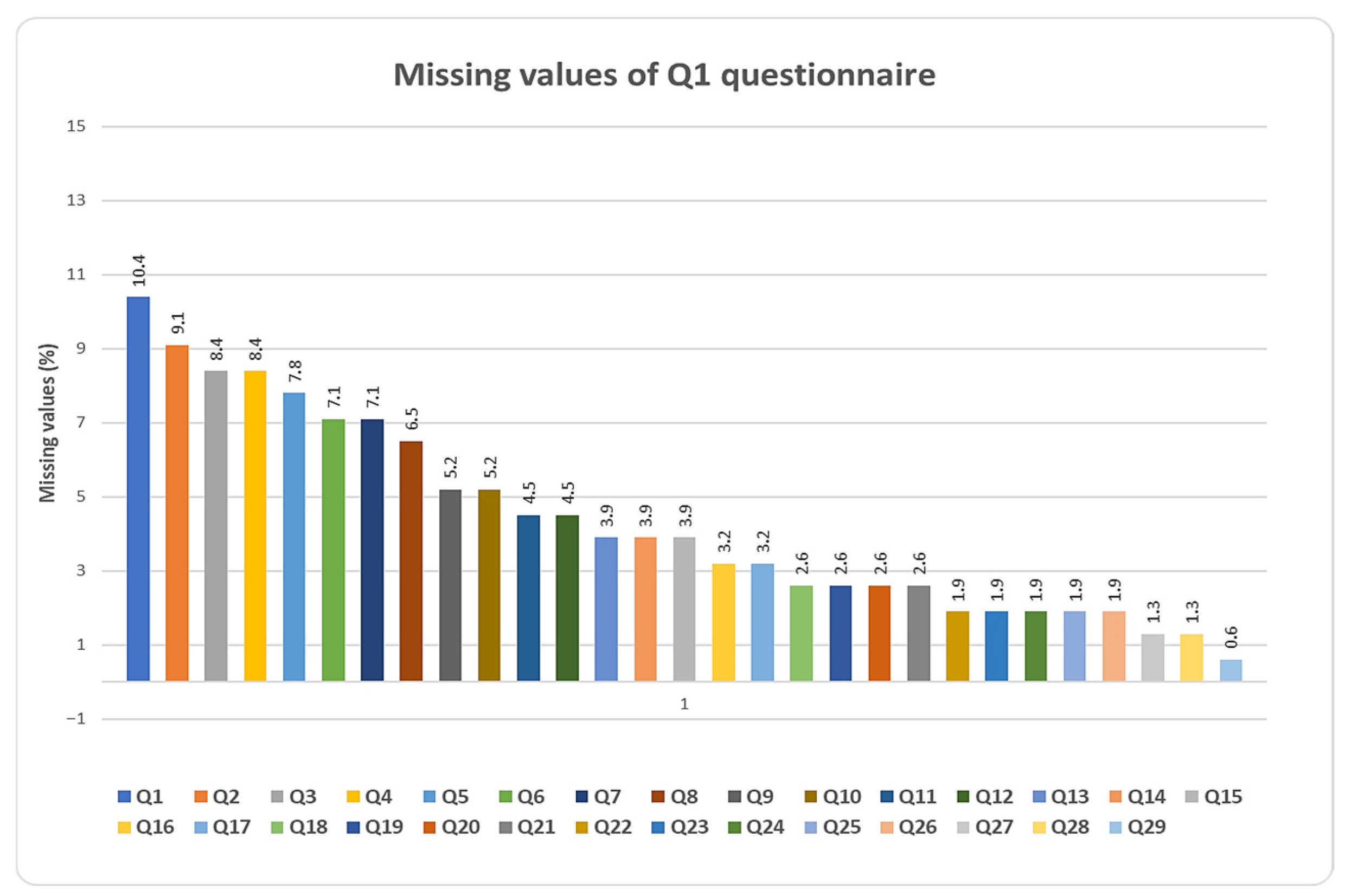

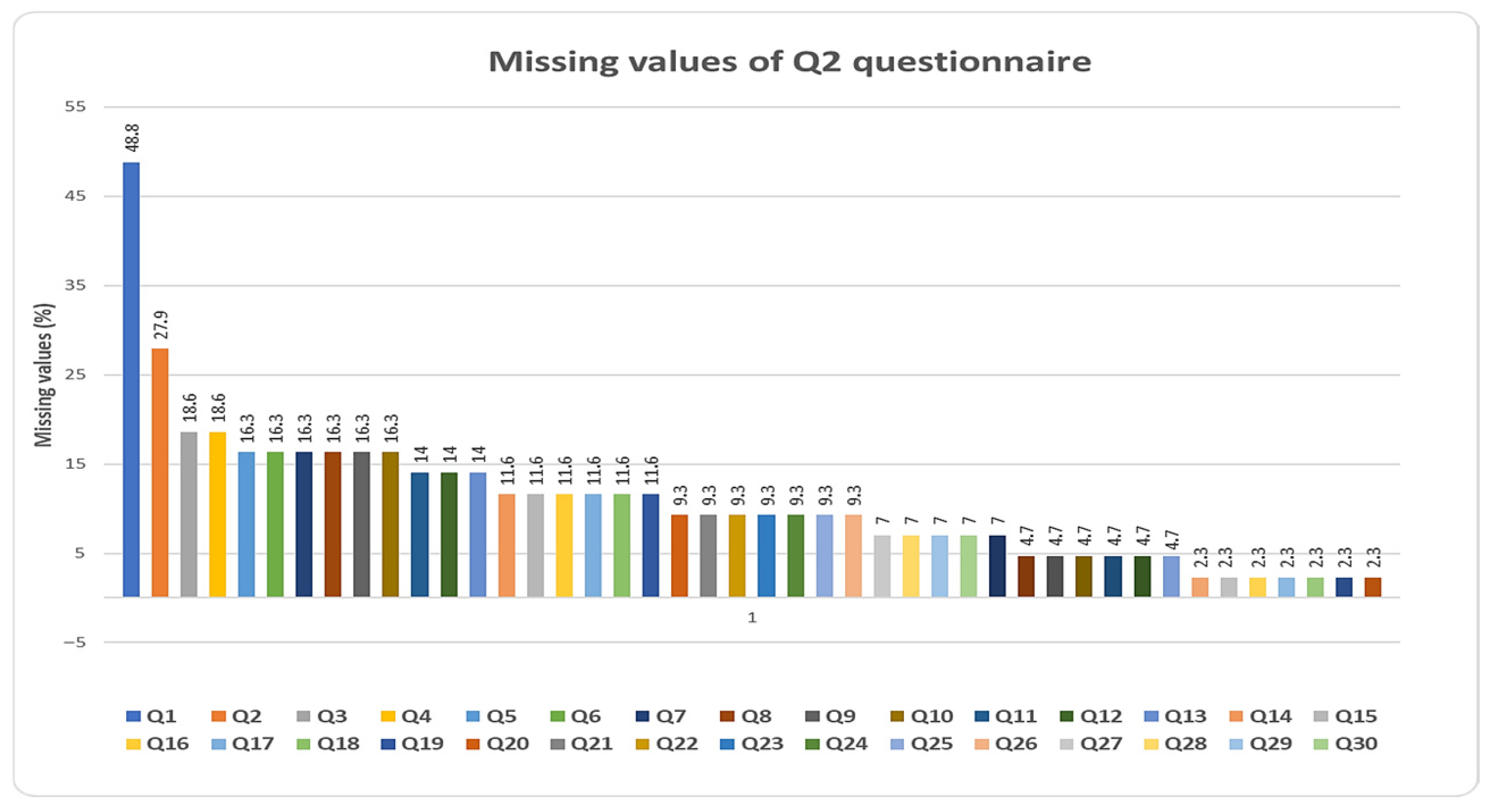

3.1. Machine Learning Cured Household Food Waste Questionnaires

3.2. Responses for the Small Group Questionnaire Along with the Projection Using ML

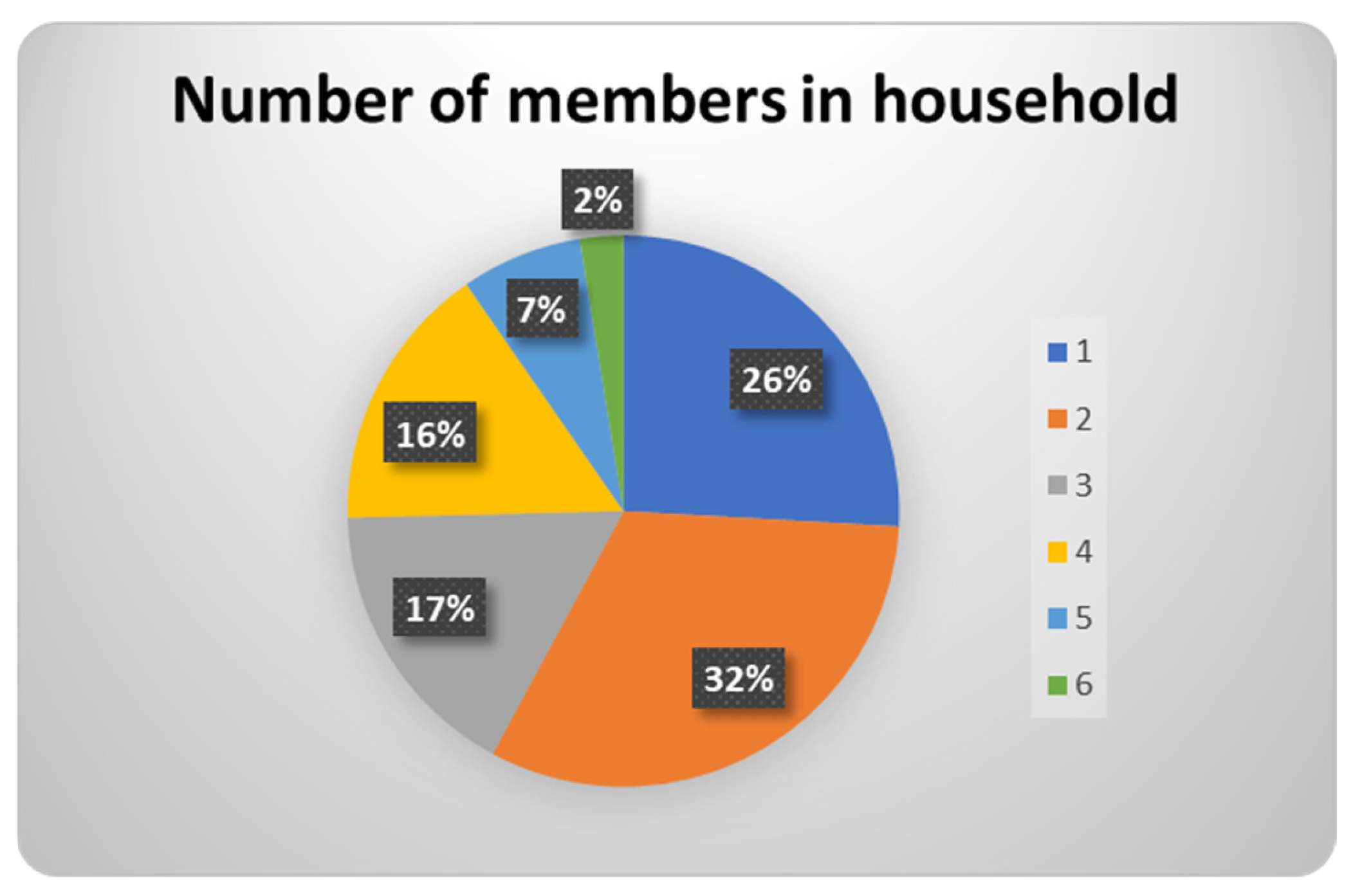

3.2.1. Demographic Findings

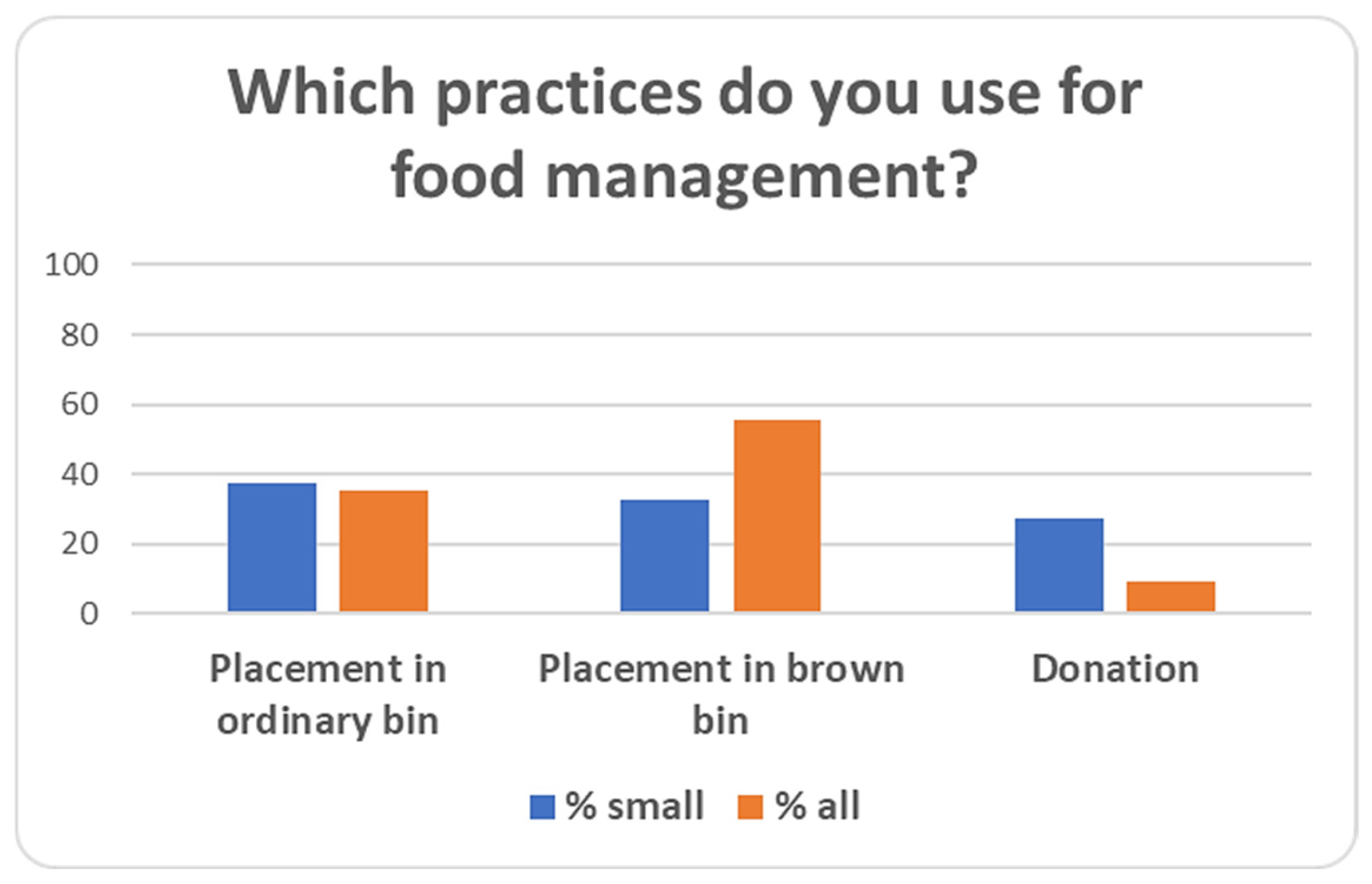

3.2.2. Food Management Habits

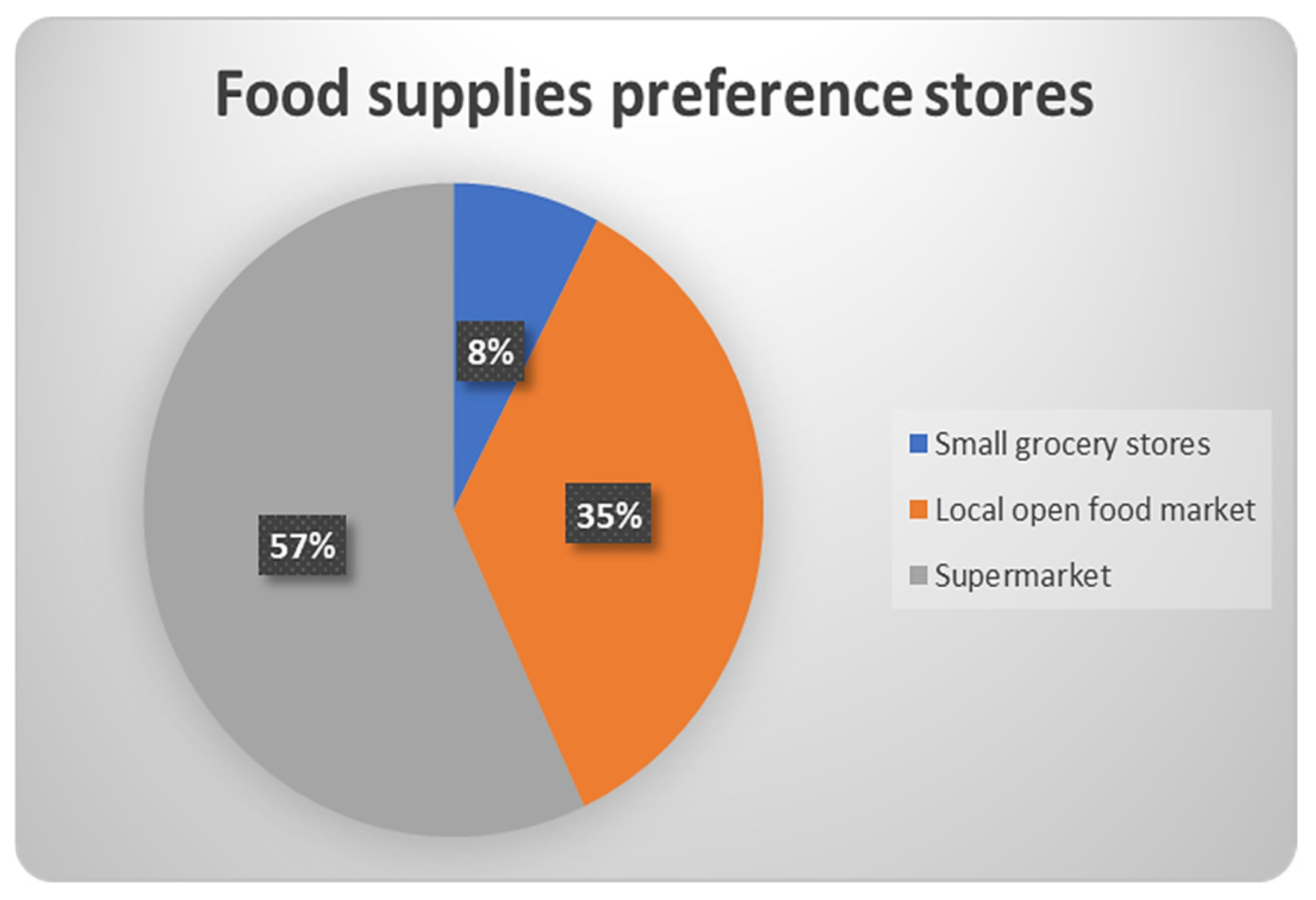

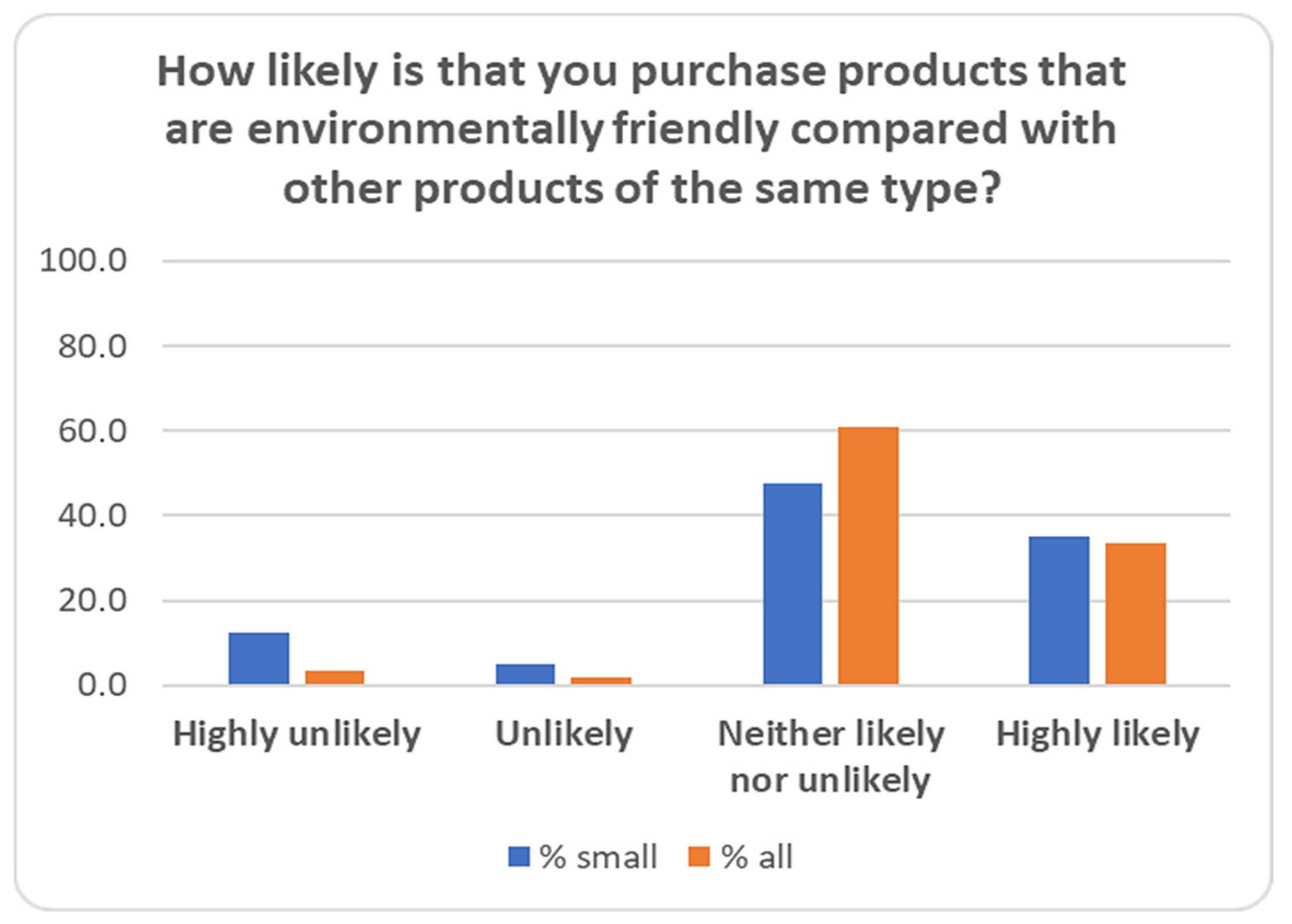

3.2.3. Shopping Habits

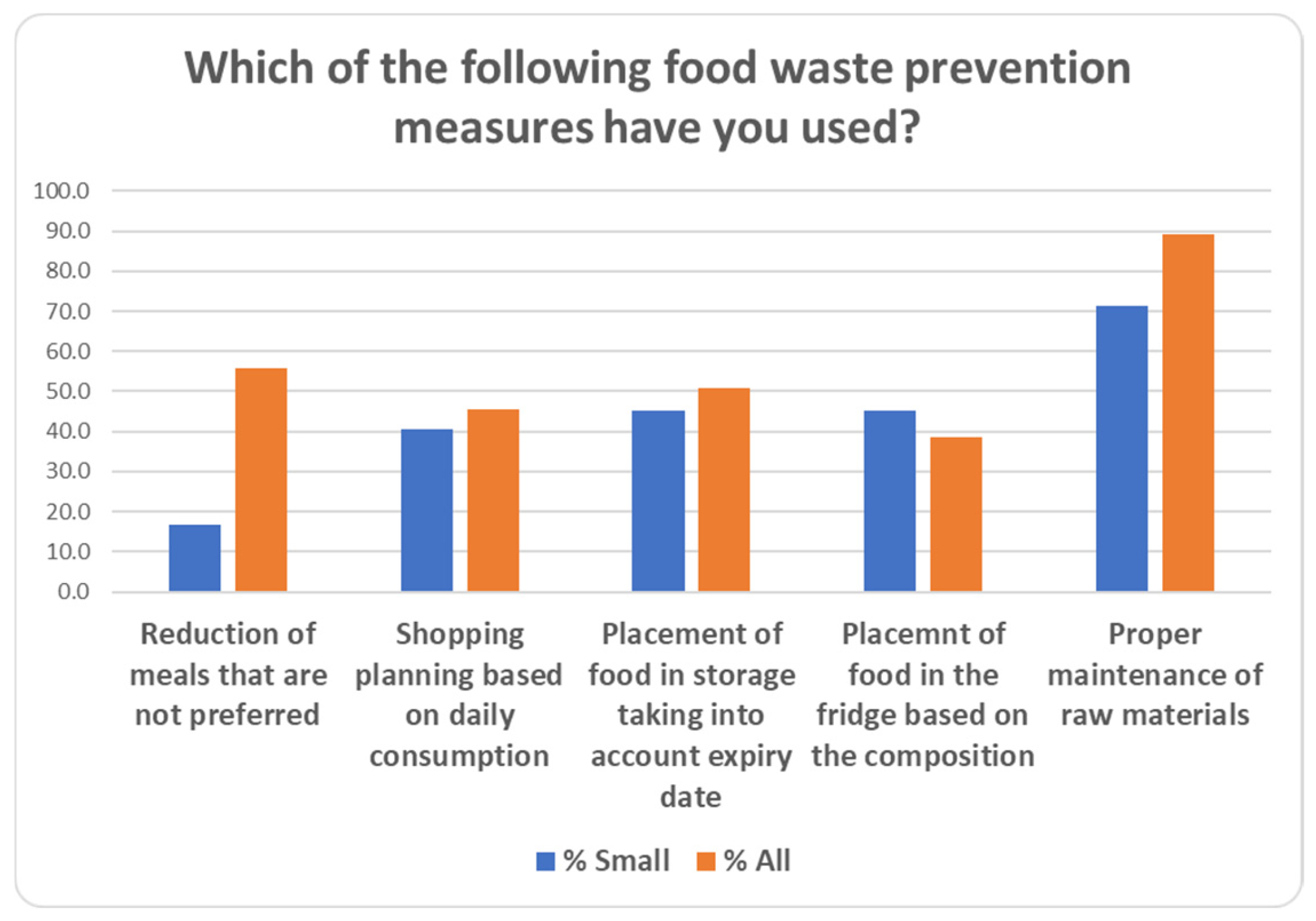

3.2.4. Food Storage

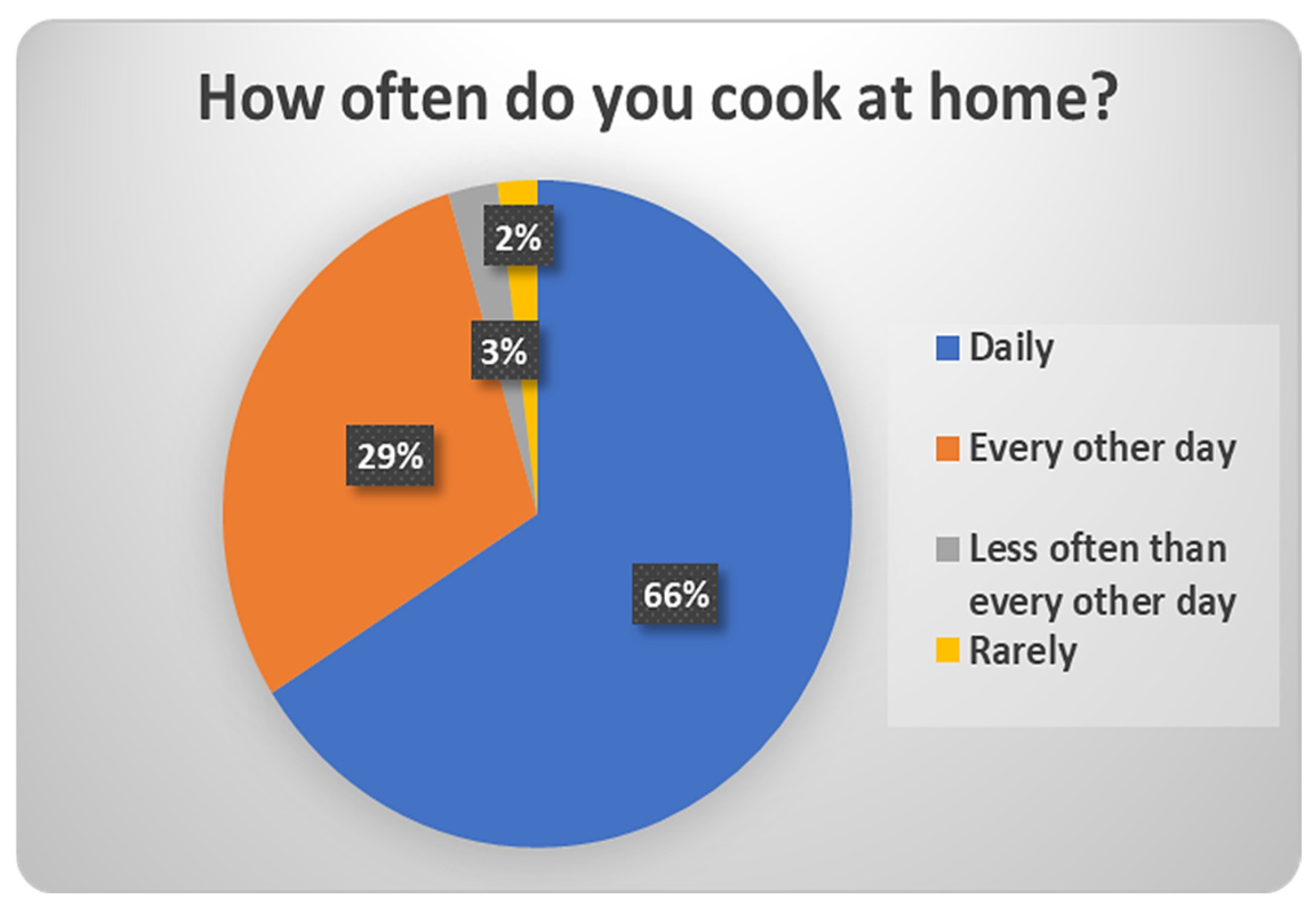

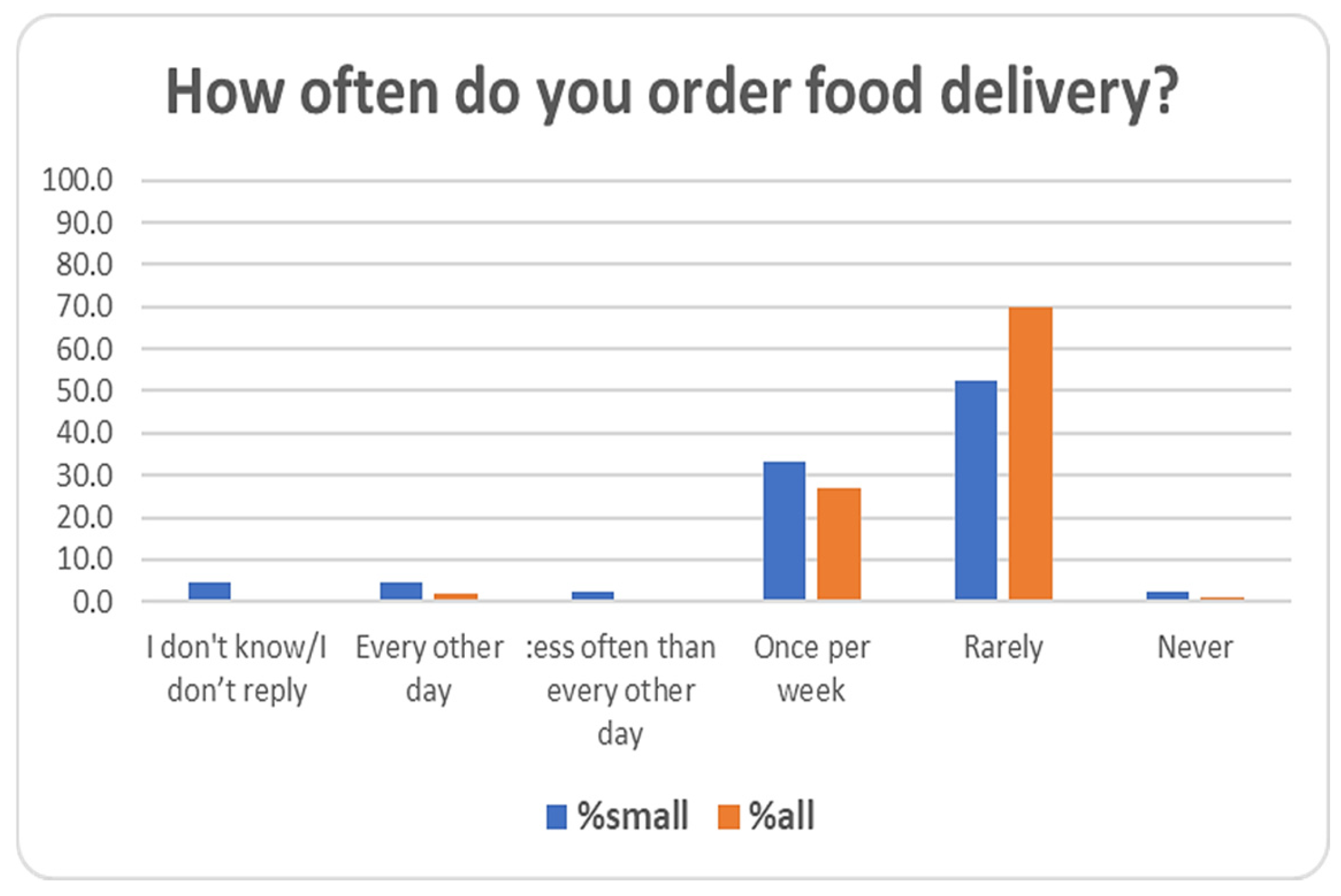

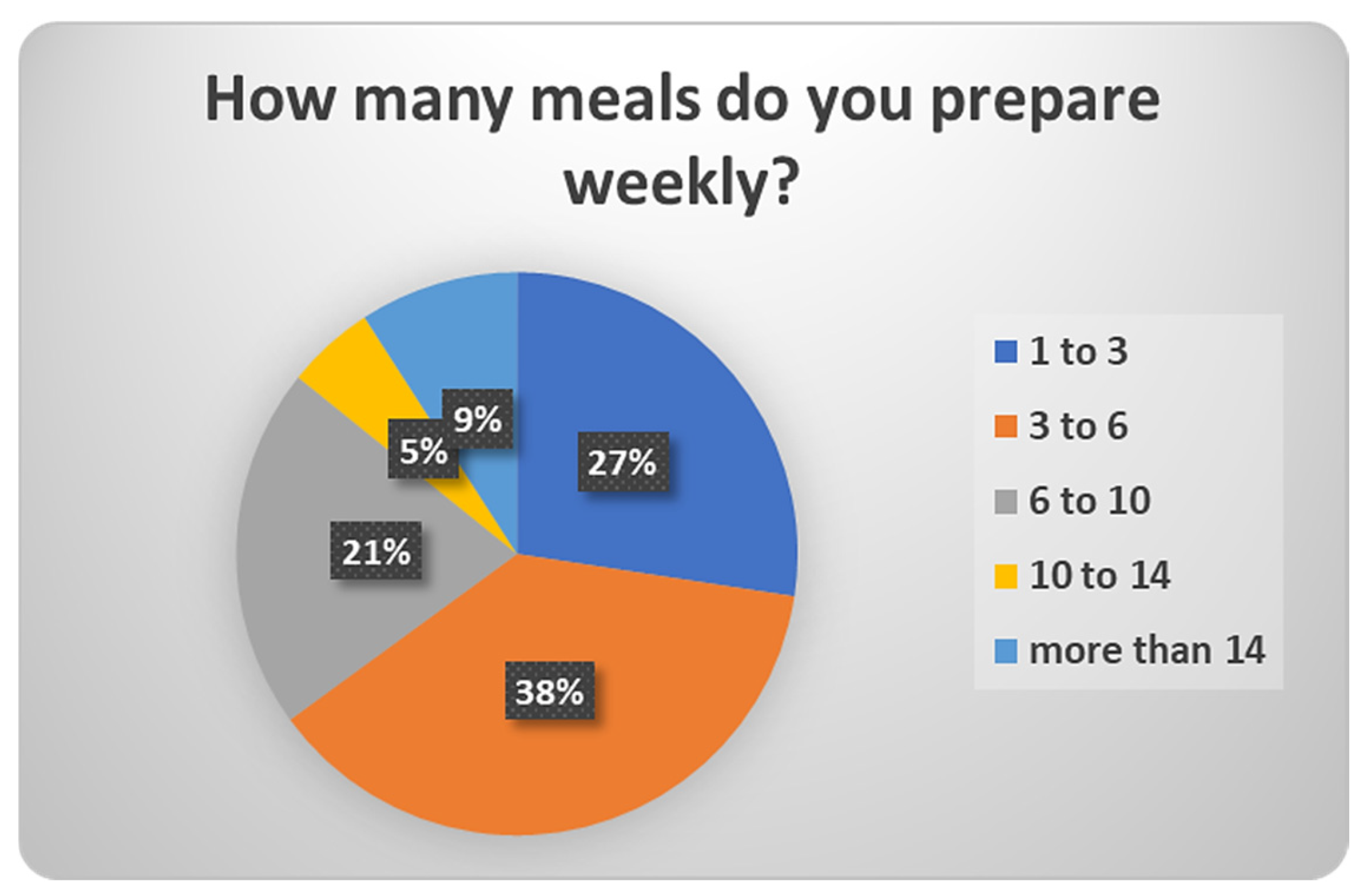

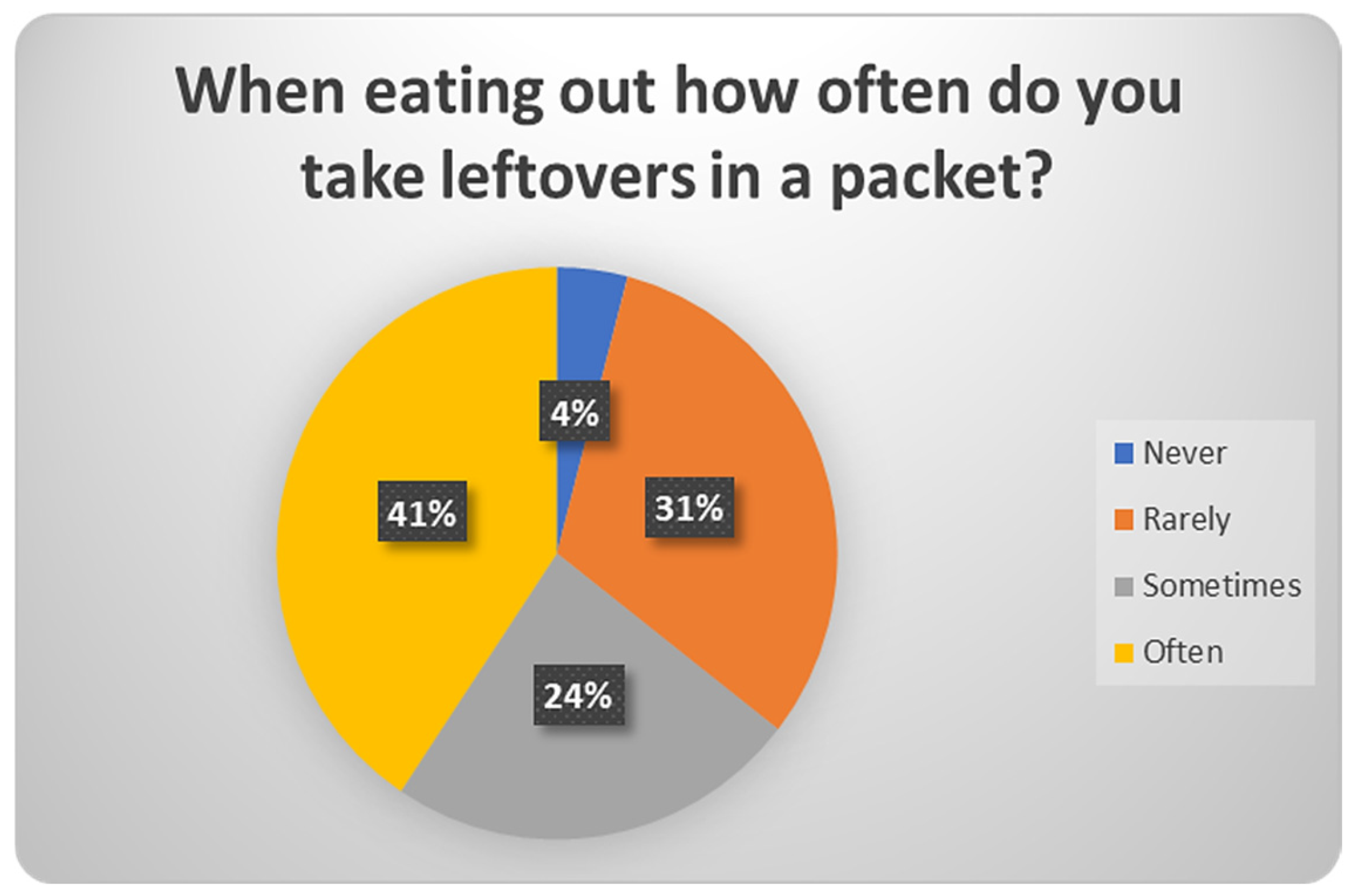

3.2.5. Cooking and Dining Habits

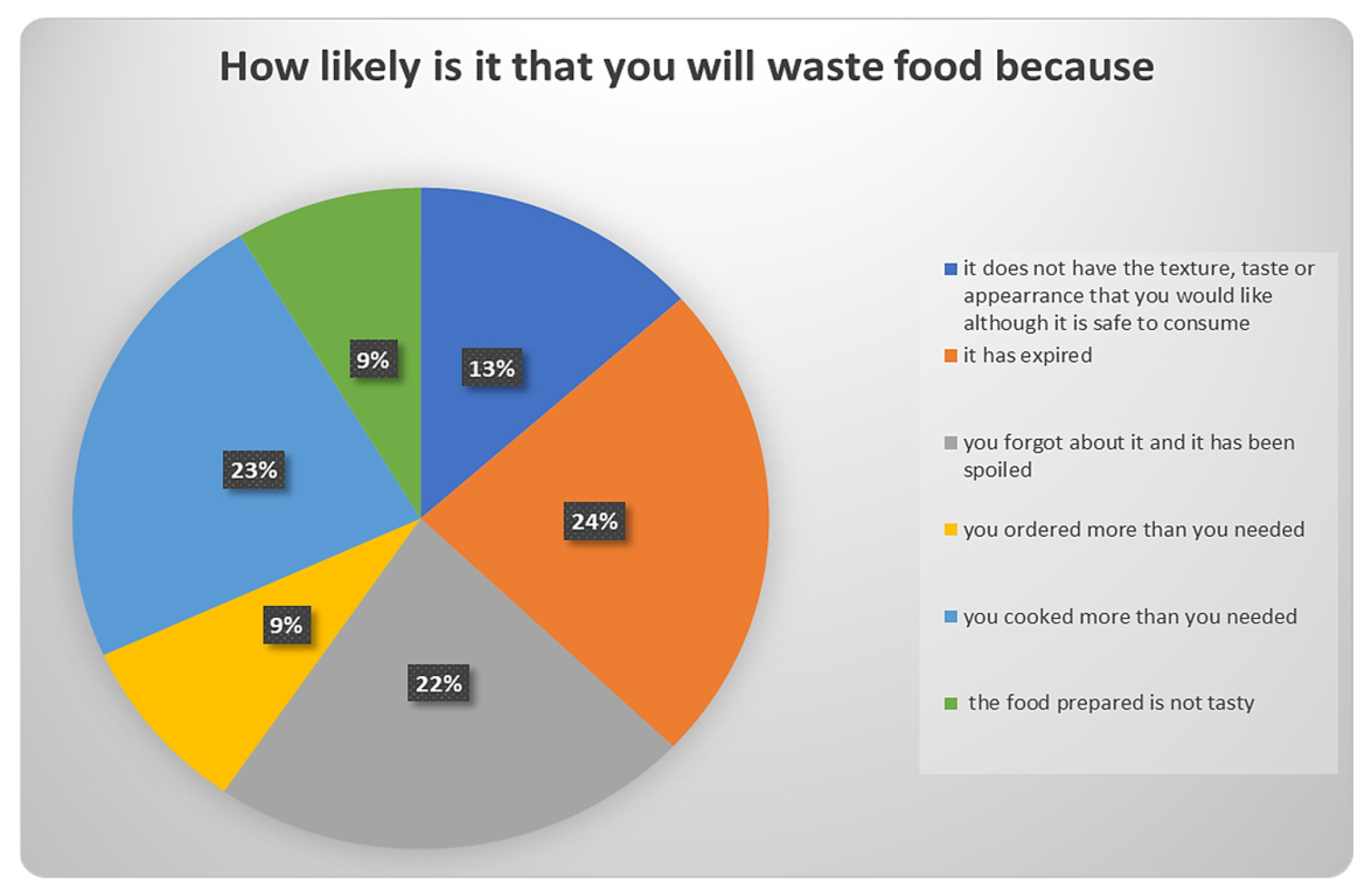

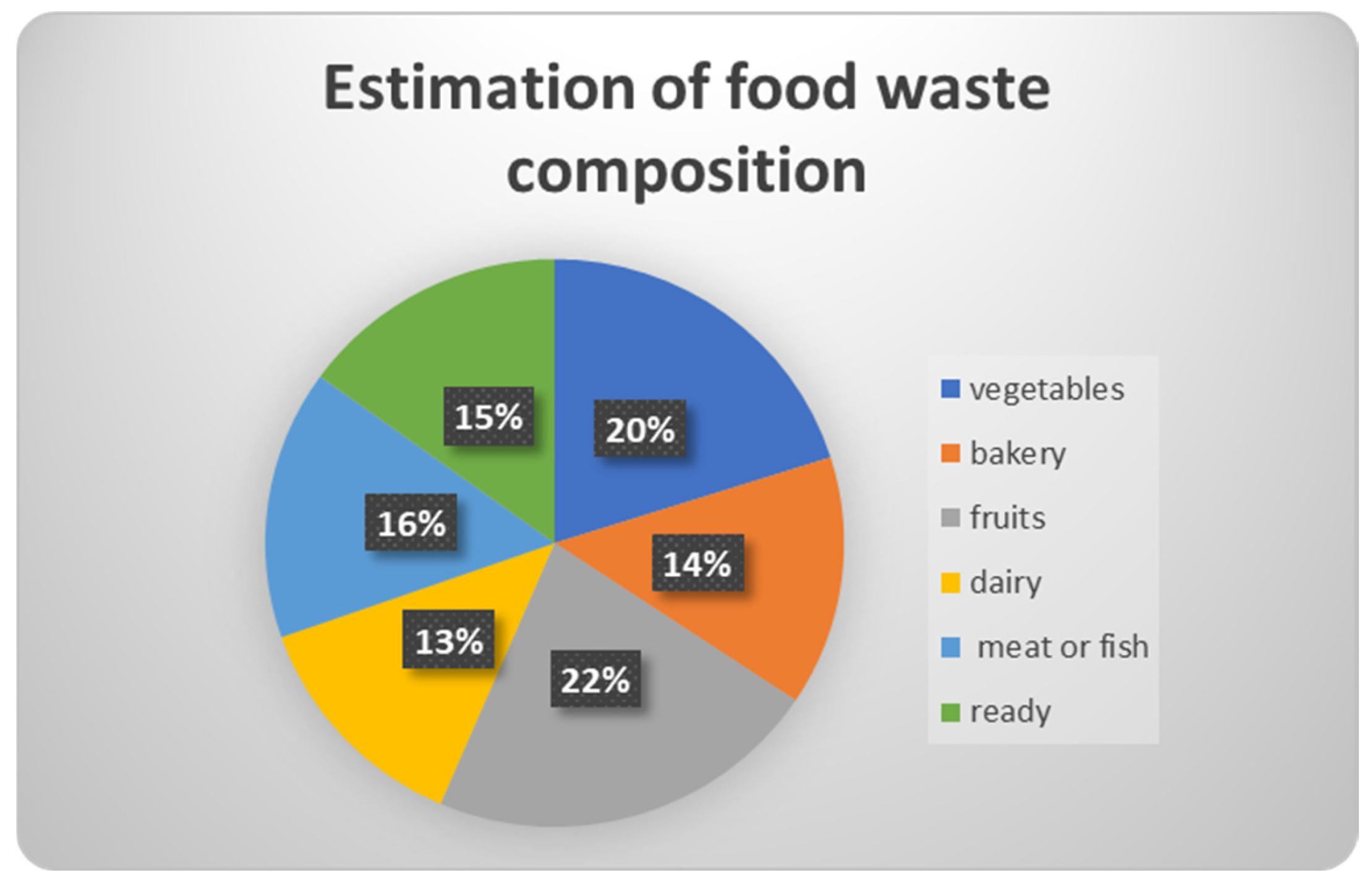

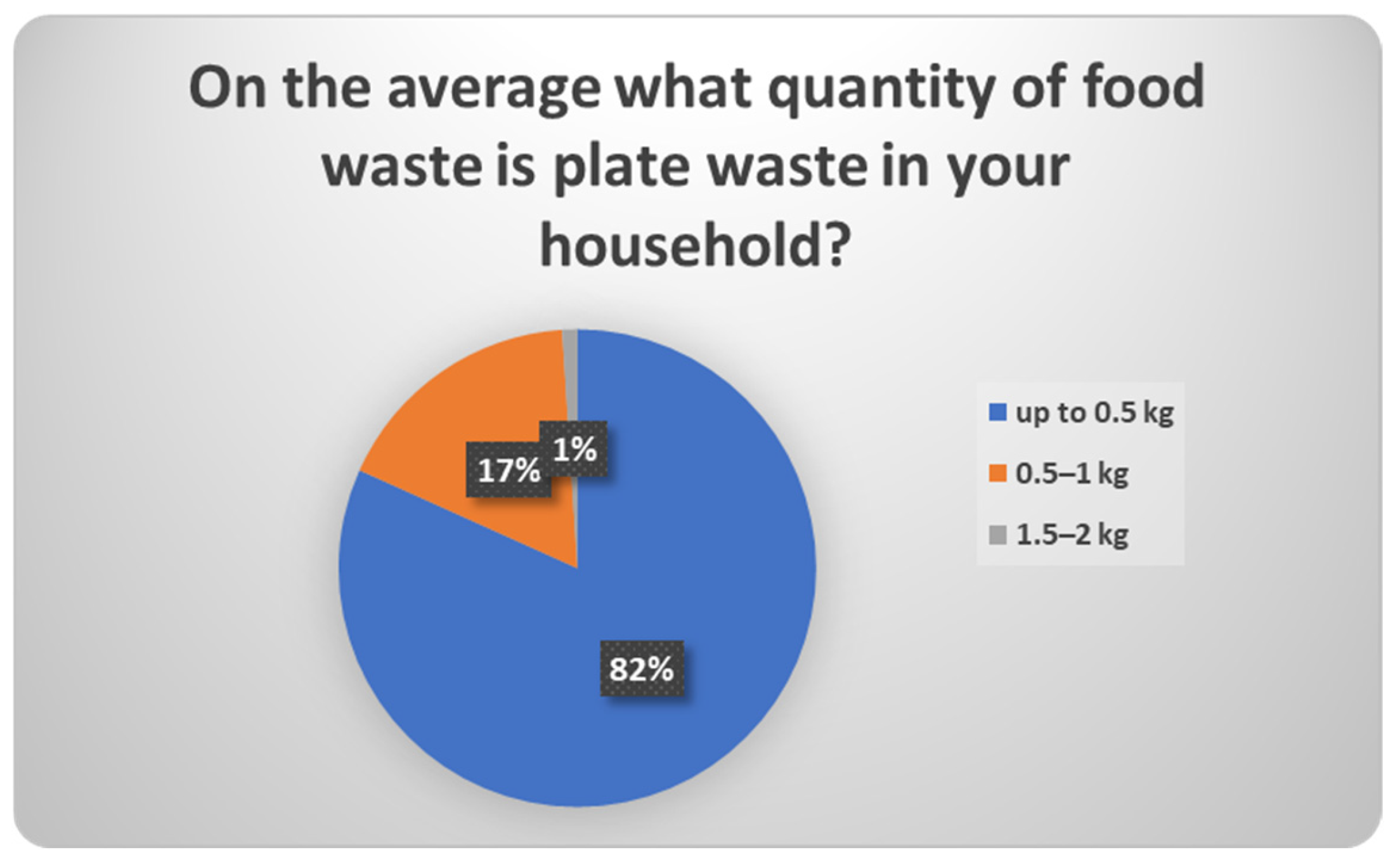

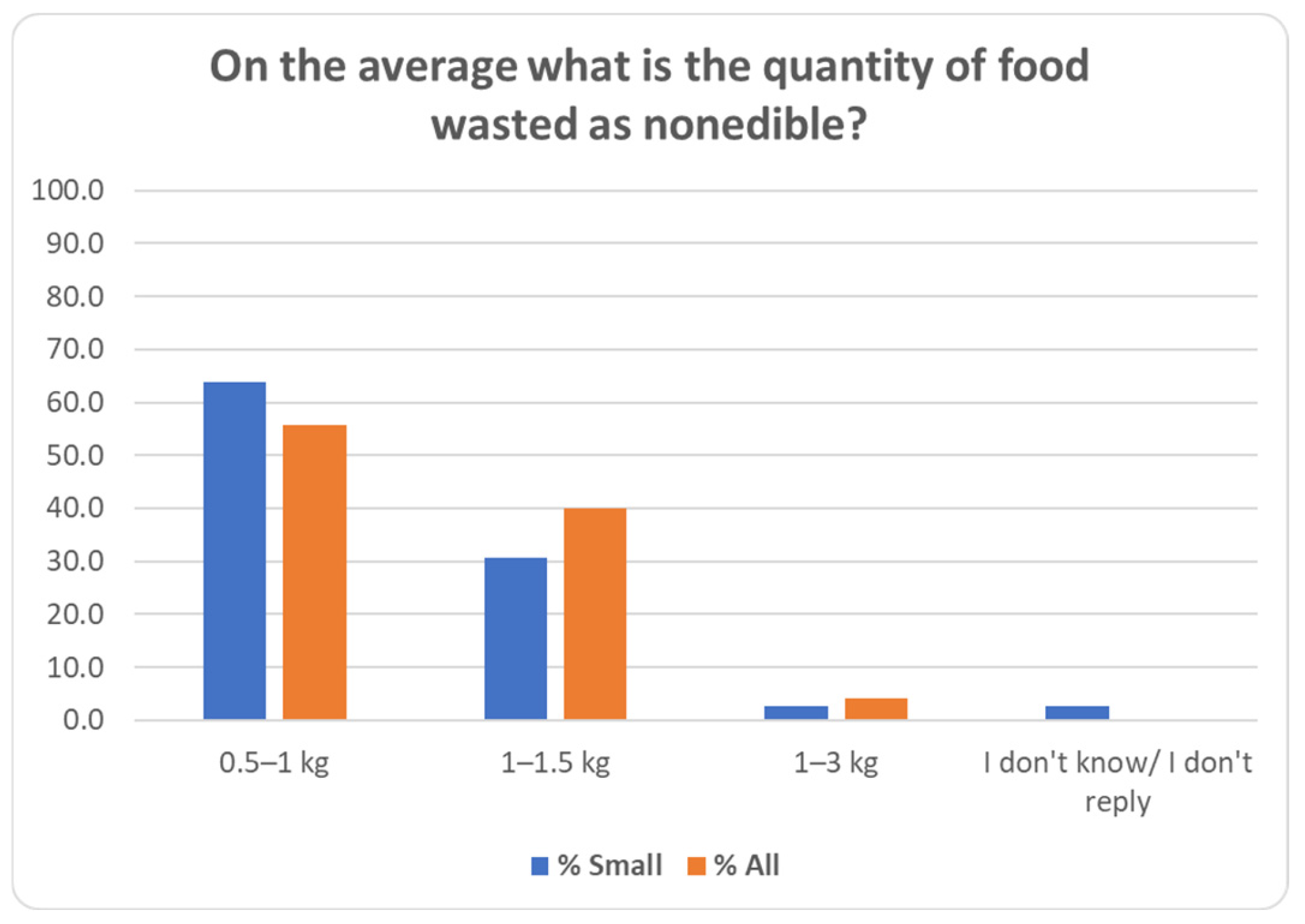

3.2.6. Food Wasting Habits

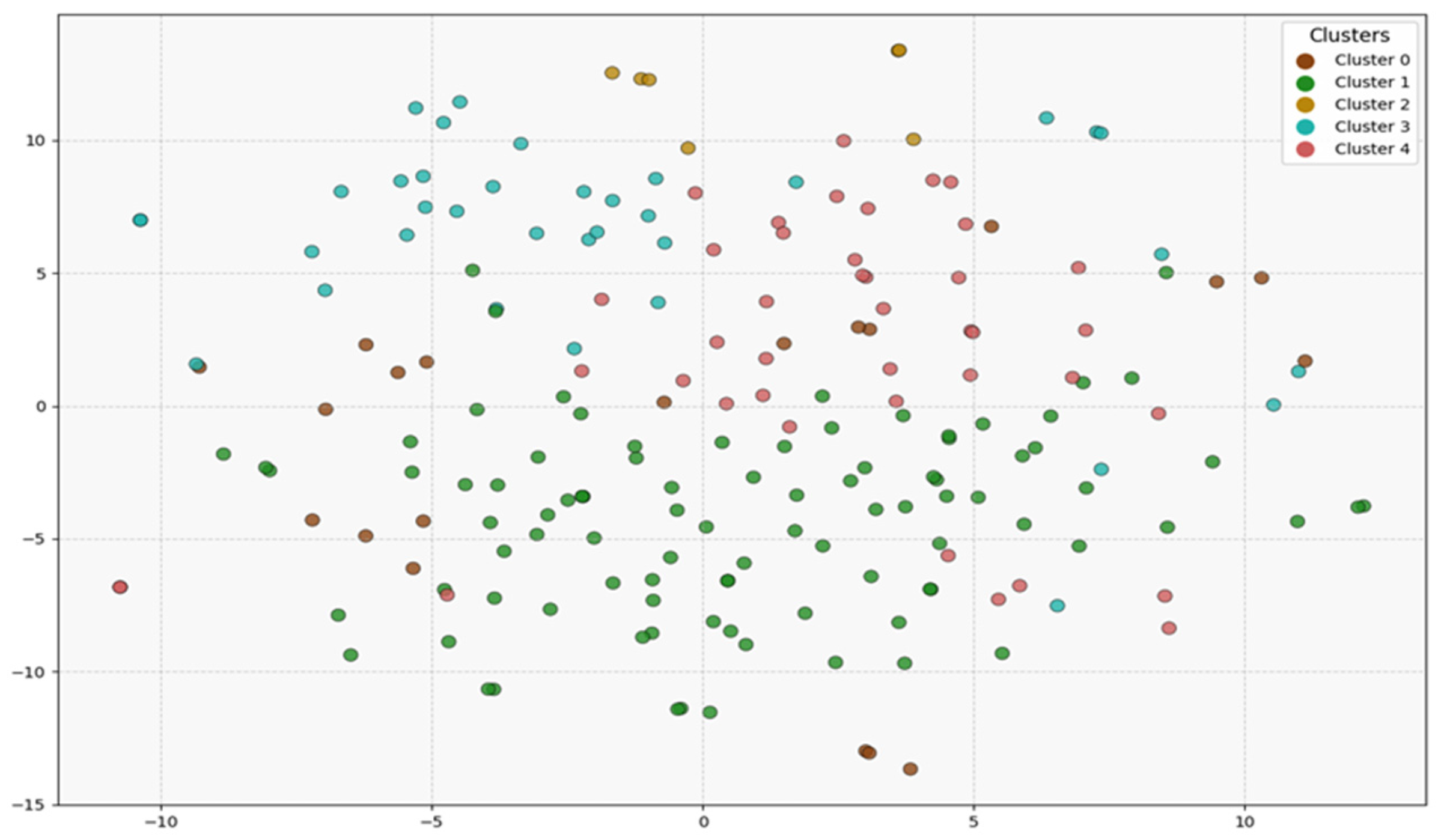

3.3. Clustering

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| FLWPU | Food Loss and Waste Prevention Unit |

| HHFW | Households Food Waste |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| CEA | Circular Economy Act |

| UN SDGs | United Nations Sustainable Development Goals |

| EU | European Union |

| F2F | Farm-to-Fork Strategy |

| FSC | Food Supply Chain |

| FLW | Food Loss and Waste |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| FL | Food Loss |

| FW | Food Waste |

| UNEP | United Nations Environmental Programme |

| MAR | Missing At Random |

| MICE | Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations |

| MSW | Municipal Solid Waste |

Appendix A

| Question | Question | Response |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | |

| 2 | Number of members in household | |

| 3 | Do you live in a town? | Yes/No |

| 4 | Shopping frequency | Several times per week/weekly |

| 5 | Is weekly planning the basis for food shopping? | Yes/No |

| 6 | Do you use a shopping list? | Yes/No |

| 7 | Is shopping influenced by offers, sales etc.? | Yes/No |

| 8 | Do you use apps for shopping planning? | Yes/No |

| 9 | Do you shop impulsively, e.g., sweets upon checkout? | Yes/No |

| 10 | Do you shop on your own or with family? | With family/On my own |

| 11 | Do you check expiry date for products? | Yes/No |

| 12 | Does your mood influence your shopping? | Yes/No |

| 13 | Are you aware of the golden rules for shopping? | Yes/No |

| 14 | If no, would you like to learn more about small things that you should take into account in order to save money and reduce food wasting? | Yes/No |

| 15 | Do you know the rules for food storage? | Yes/No |

| 16 | Do you use cooking recipes? | Yes/No |

| 17 | Do you use food residues for preparing new meals? | Yes/No |

| 18 | Do you know the golden rules for effective cooking? | Yes/No |

| 19 | If no, would you like to learn some tips for effective storage, cooking and food processing that can save money and reduce food wasting? | Yes/No |

| 20 | Do you think that you generate a lot of food waste? | Yes/No |

| 21 | Do you separate food waste from other waste at home? | Yes/No |

| 22 | Do you put food waste in the corresponding bin? | Yes/No |

| 23 | Do you know the rules for food storage and food wasting? | Yes/No |

| 24 | If no, would you like to learn some tips for food storage and food wasting in order to reduce food wasting and help combat climate change? | Yes/No |

| 25 | Do you know if there are people in need of food? | Yes/No |

| 26 | Would you be willing to donate food that you will not use before expiry date? | Yes/No |

| 27 | Do you know where you can donate food? | Yes/No |

| 28 | If no, would you like to learn how you can help needy people and help fight climate change? | Yes/No |

| 29 | Are you aware that food wasting increases CO2 emissions and contributes to climate change? | Yes/No |

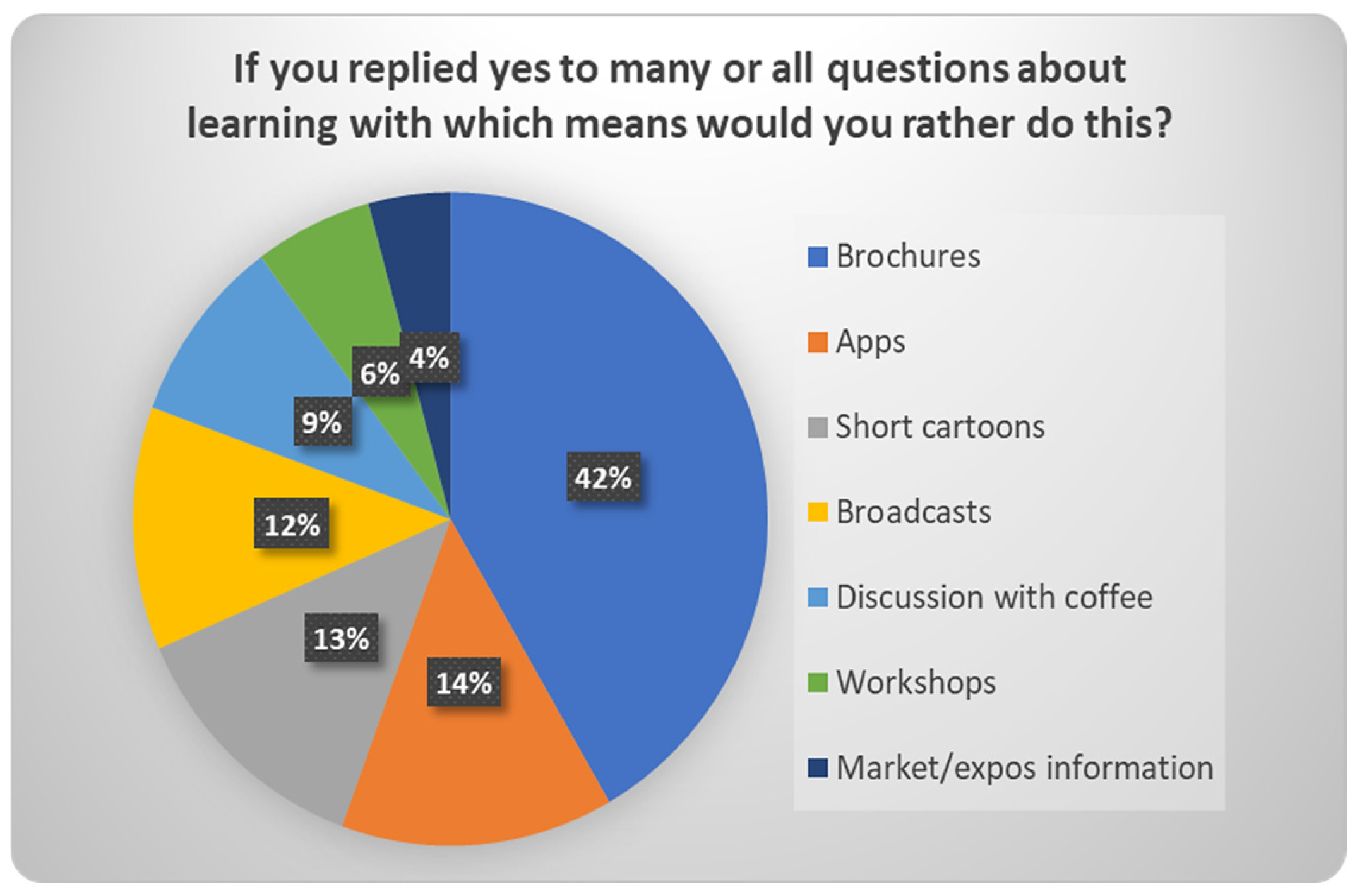

| 30 | If you replied yes to many or all questions about learning with which means, would you rather do this? | Brochures/Apps/Short cartoons/Broadcasts/Discussion with coffee/Workshops |

| Question | Question | Response |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Do you agree with the declaration of consent to the processing of personal data? | Yes/No |

| 2 | Household members | |

| 3 | Age groups | <30/30–40/41–50/51–65/>65 |

| 4 | Occupation | Pupil/Student/Employee/Freelancer-self-employed/Pensioner/Housekeeping- not employed |

| 5 | Do you participate in grocery shopping for your home? | Yes/No |

| 6 | Have you ever heard the term “food waste” or “food loss” or “organic food waste”? | Yes/No |

| 7 | You usually select for food shopping: | Delicatessen/Local producers/Small grocery stores/Internet purchasing/Local open food market/Supermarkets |

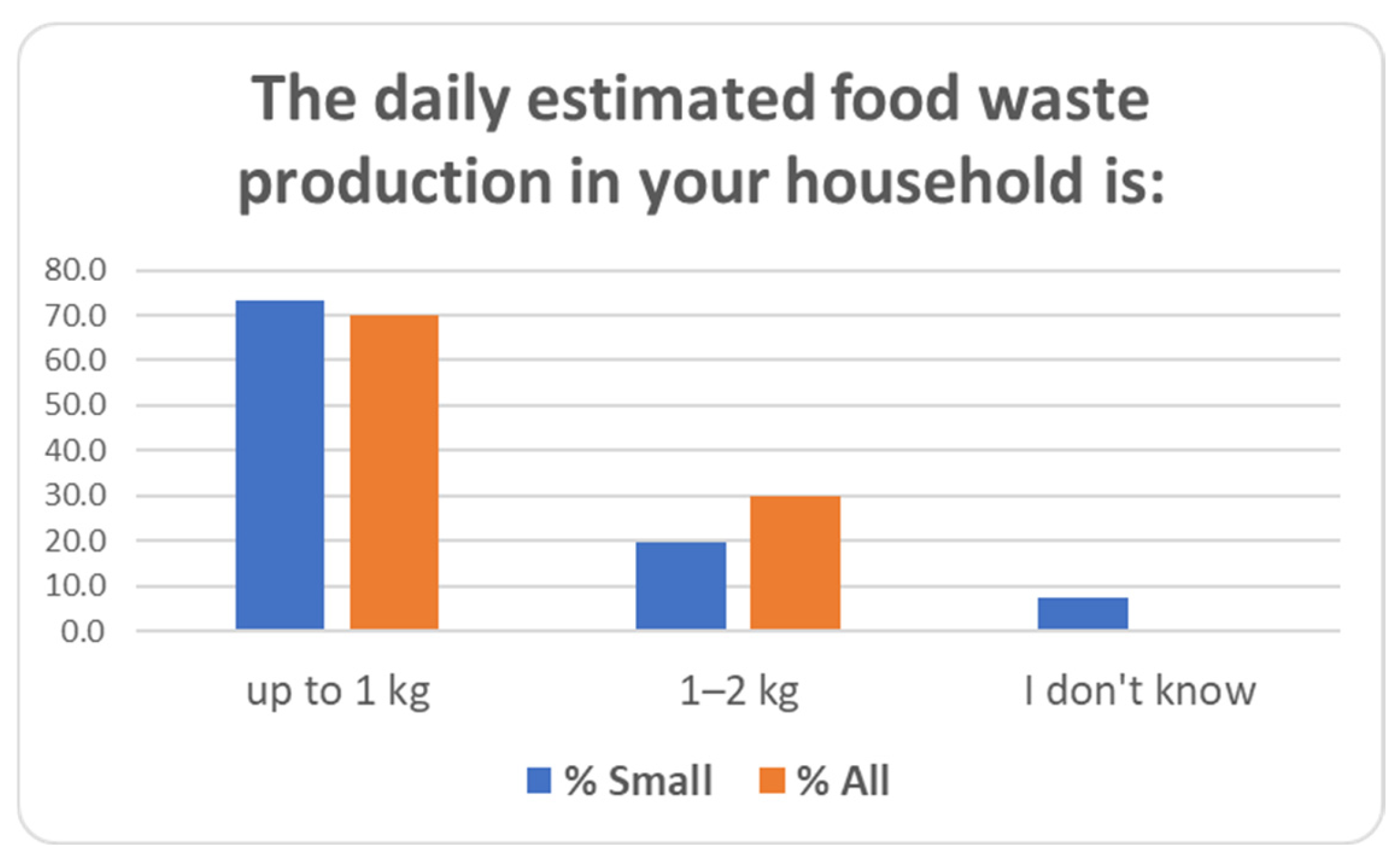

| 8 | The daily estimated food waste production in your household is: | Up to 1 kg/1–2 kg/I don’t know |

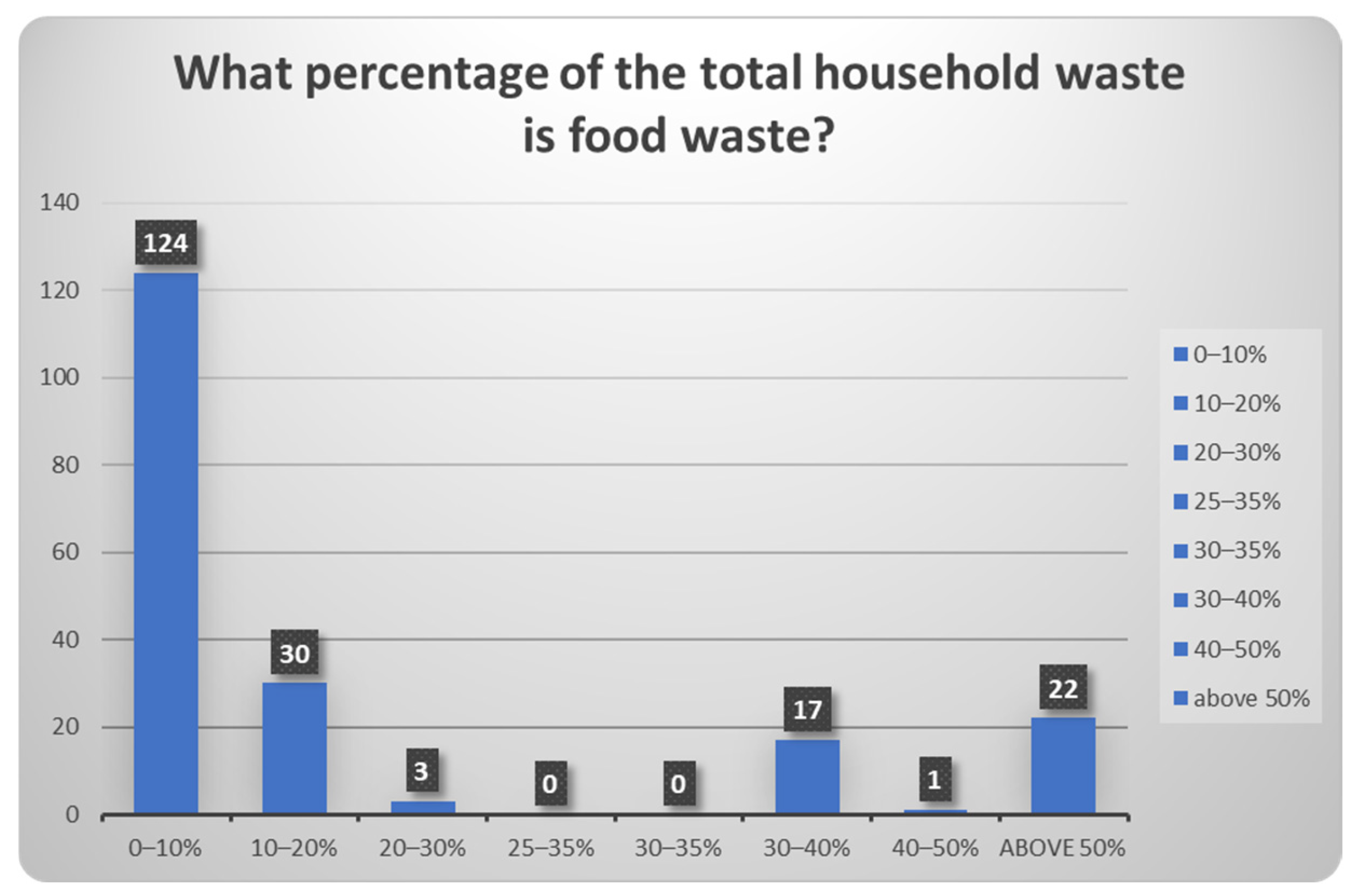

| 9 | What percentage of the total household waste is food waste? | 0–10/10–20/20–30/30–40/40–50/above 50%/I don’t know-I do not wish to reply |

| 10 | How likely is it that you will waste food because it does not have the texture, taste or appearance that you would like although it is safe to consume? | Highly unlikely/Neither likely, nor unlikely/Likely/Highly likely/I don’t know-I do not wish to reply |

| 11 | How likely is it that you will waste food because it has expired? | Highly unlikely/Neither likely, nor unlikely/Likely/Highly likely/I don’t know-I do not wish to reply |

| 12 | How likely is it that you will waste food because you forgot about it and it has been spoiled? | Highly unlikely/Neither likely, nor unlikely/Likely/Highly likely/I don’t know-I do not reply |

| 13 | How likely is it that you will waste food because you ordered more than you needed? | Highly unlikely/Neither likely, nor unlikely/Likely/Highly likely/I don’t know-I do not reply |

| 14 | How likely is it that you will waste food because you cooked more than you needed? | Highly unlikely/Neither likely, nor unlikely/Likely/Highly likely/I don’t know-I do not reply |

| 15 | How likely is it that you will waste food because the food prepared is not tasty? | Highly unlikely/Neither likely, nor unlikely/Likely/Highly likely/I don’t know-I do not reply |

| 16 | Percentage of food waste that is vegetables | 0–10/10–20/20–30/30–40/40–50/50–60/60–70/70–80/80–90 |

| 17 | Percentage of food waste that is bread, cereals, bakery products | 0–10/10–20/20–30/30–40/40–50/50–60/60–70/70–80/80–90 |

| 18 | Percentage of food waste that is fruits | 0–10/10–20/20–30/30–40/40–50/50–60/60–70/70–80/80–90 |

| 19 | Percentage of food waste that is dairy products | 0–10/10–20/20–30/30–40/40–50/50–60/60–70/70–80/80–90 |

| 20 | Percentage of food waste that is meat or fish | 0–10/10–20/20–30/30–40/40–50/50–60/60–70/70–80/80–90 |

| 21 | Percentage of food waste that is ready meals | 0–10/10–20/20–30/30–40/40–50/50–60/60–70/70–80/80–90 |

| 22 | How often do you cook at home? | Daily/Every other day/Less often than every other day/Rarely/I don’t know-I don’t wish to reply |

| 23 | How often do you order food delivery? | Every other day/Less often than every other day/Once per week/Rarely/Never/I don’t know-I don’t wish to reply |

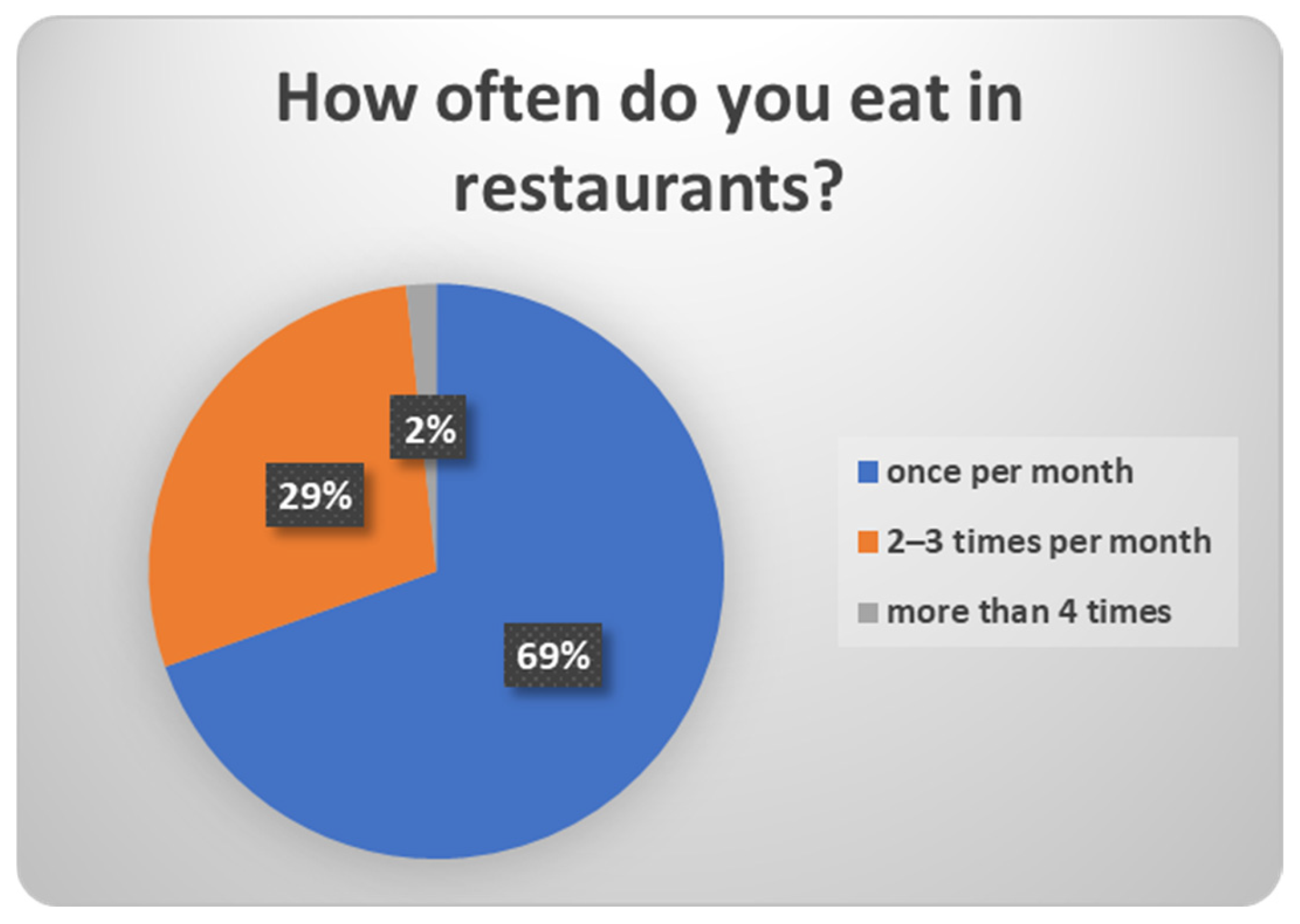

| 24 | How often do you eat in restaurants? | Once per month/2–3 times per month/more than 4 times/I don’t know-I don’t wish to reply |

| 25 | When eating out how often do you take leftovers in a packet? | Never/Rarely/Sometimes/Often |

| 26 | How many meals do you prepare weekly? | 1 to 3/3 to 6/6 to 10/10 to 14/more than 14 |

| 27 | On the average what is the quantity of food wasted as nonedible? (kg) | up to 0.5/0.5–1/1–1.5/1–3/3–5/ more than 5/I don’t know-I don’t wish to reply |

| 28 | On the average what quantity of food waste is plate waste in your household? (kg) | up to 0.5/0.5–1/1.5–2/more than 2/I don’t know-I do not wish to reply |

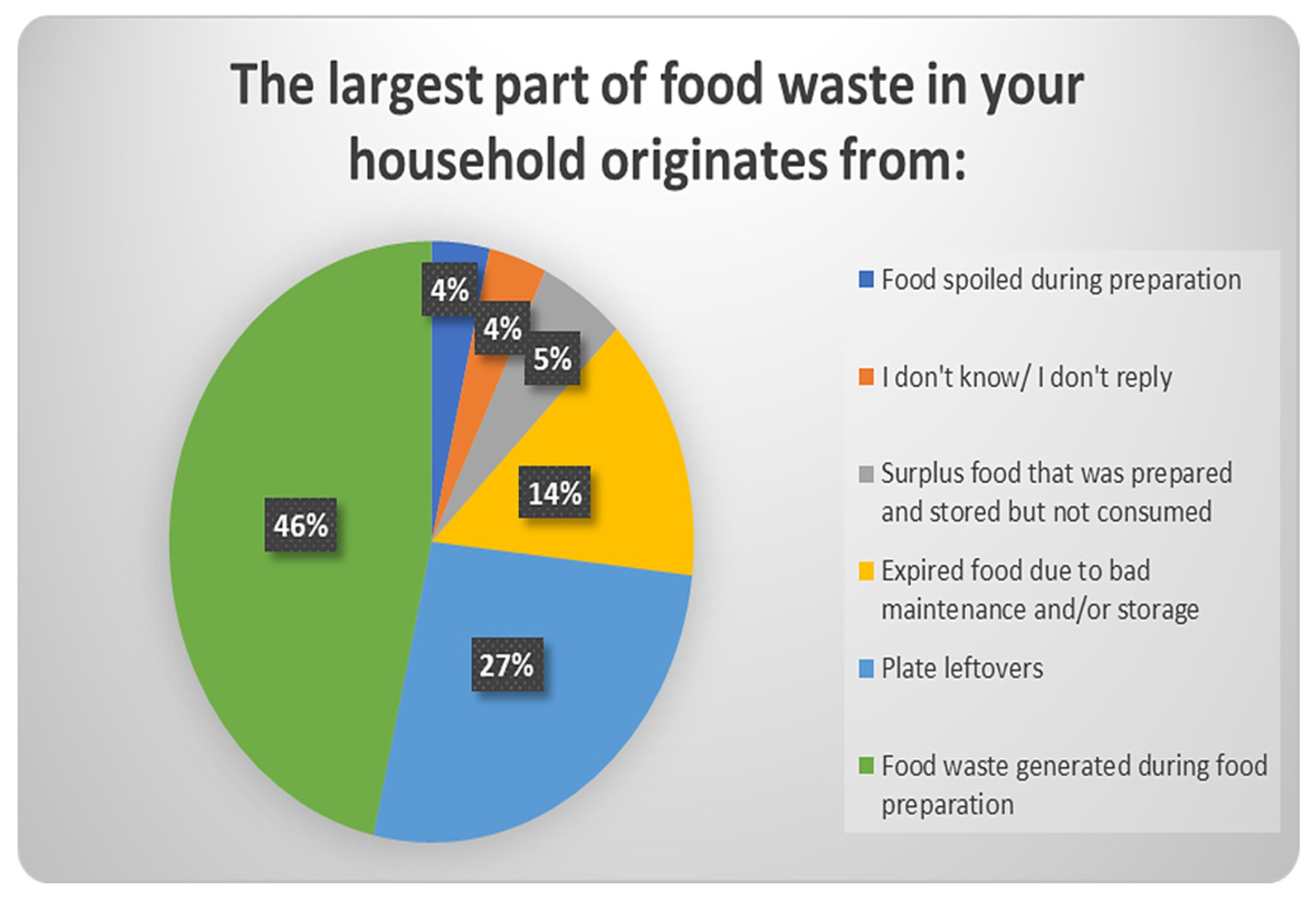

| 29 | The largest part of food waste in your household is attributed to: | Food generated during food preparation (unavoidable)/Plate leftovers/Expired food due to inappropriate management and- or storage/Surplus food that was prepared and stored but not consumed/Food spoiled during preparation/I don’t know-I do not wish to reply |

| 30 | Which of the following food waste prevention measures have you used? | Reduction of meals that are not preferred/Shopping planning based on daily consumption/Placement of food in storage considering expiry date/Placement of food in the fridge based on the composition |

| 31 | Which practices do you use for food management? | Placement in ordinary bin/Placement in brown bin/Donation/I don’t know- I do not wish to reply |

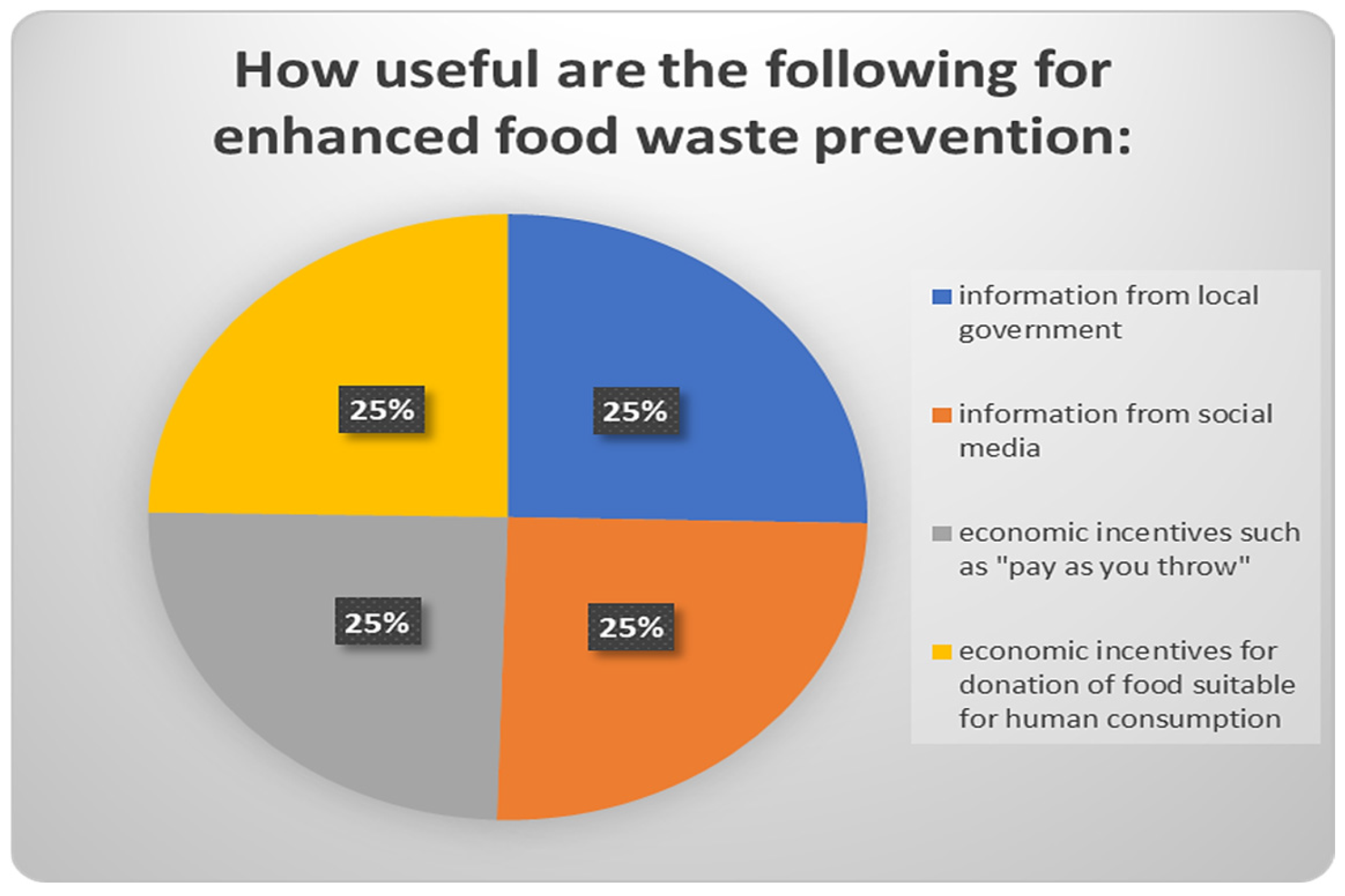

| 32 | How useful is the following for enhanced food waste prevention: information from local government | Not at all/Barely/Moderately/Substantially/Significantly/Very much |

| 33 | How useful is the following for enhanced food waste prevention: information from social media | Not at all/Barely/Moderately/Substantially/Significantly/Very much |

| 34 | How useful is the following for enhanced food waste prevention: economic incentives such as “pay as you throw” | Not at all/Barely/Moderately/Substantially/Significantly/Very much |

| 35 | How useful is the following for enhanced food waste prevention: economic incentives for donation of food suitable for human consumption? | Not at all/Barely/Moderately/Substantially/Significantly/Very much |

| 36 | How likely is that you purchase products that are environmentally friendly compared with other products of the same type? | Not at all/Highly unlikely/Unlikely/Neither likely nor unlikely/Highly likely |

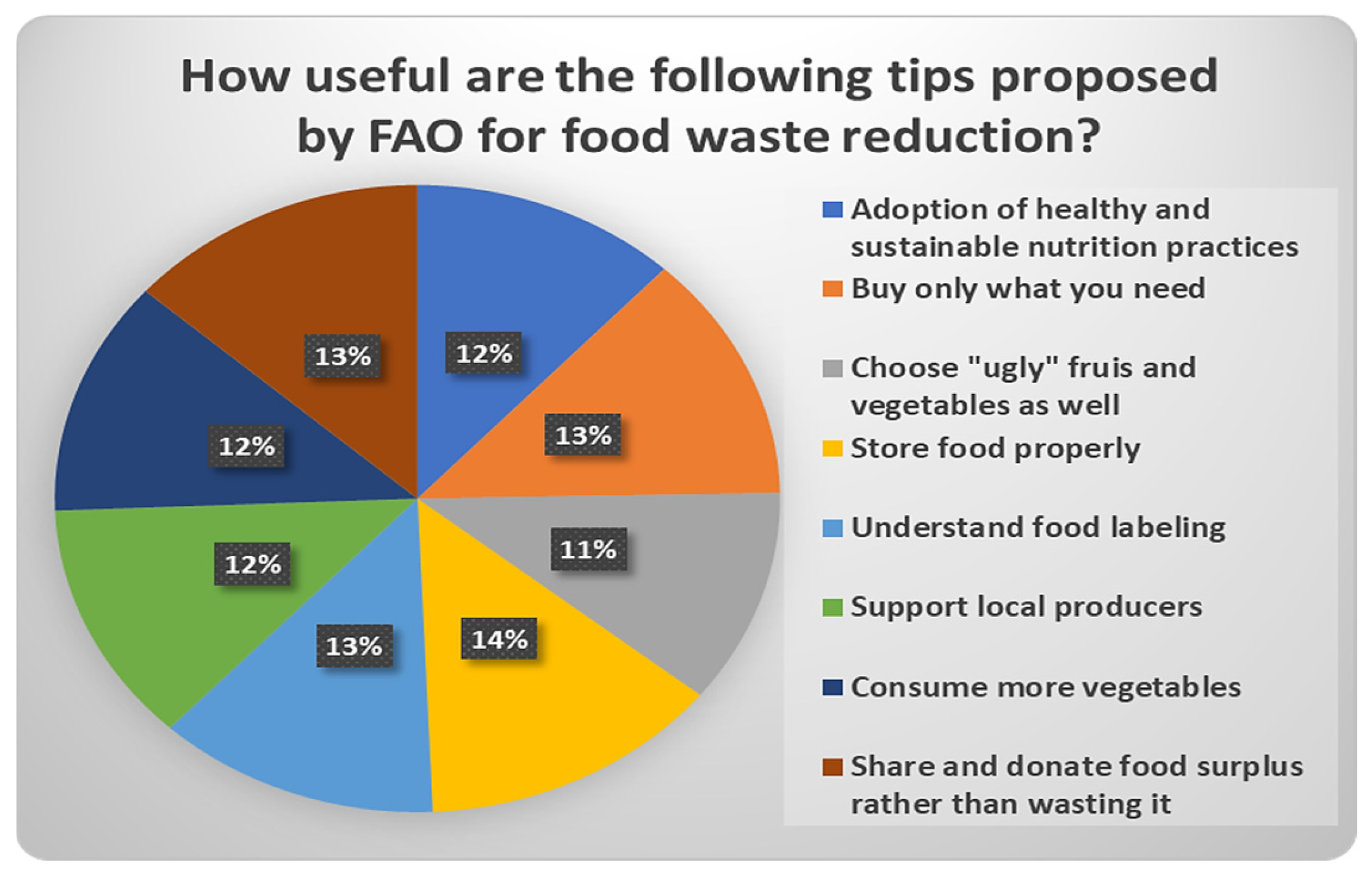

| 37 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Adoption of healthy and sustainable nutrition practices | Not at all/Barely/Moderately/Substantially/Significantly/Very Much |

| 38 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Buy only what you need | Not at all/Barely/Moderately/Substantially/Significantly/Very Much |

| 39 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Choose “ugly” fruits and vegetables as well | Not at all/Barely/Moderately/Substantially/Significantly/Very Much |

| 40 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Store food properly | Not at all/ Barely/ Moderately/ Substantially/ Significantly/ Very Much |

| 41 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Understand food labeling | Not at all/Barely/Moderately/Substantially/Significantly/Very Much |

| 42 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Support local producers | Not at all/Barely/Moderately/Substantially/Significantly/Very Much |

| 43 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Consume more vegetables | Not at all/Barely/Moderately/Substantially/Significantly/Very Much |

| 44 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Share and donate food surplus rather than wasting it | Not at all/Barely/Moderately/Substantially/Significantly/Very Much |

| 45 | Do you know if in the Municipality of Halandri there is separate collection of food waste using the brown bin? | Yes/No |

| 46 | Do you know that “use by” label on a food product refers to the time until it may be safely consumed whereas the phrase “ best before” refers to the taste and texture of the product, which is still safe to consume? | Yes/No |

| 47 | Do you know that food wasting is responsible for the emission of a significant amount of greenhouse gases? | Yes/No |

| Question | Question | Missing Values (%) | Number of Missing Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Do you use apps for shopping planning? | 10.4 | 16 |

| 2 | Is weekly planning the basis for food shopping? | 9.1 | 14 |

| 3 | Do you shop impulsively, e.g., sweets upon checkout? | 8.4 | 13 |

| 4 | Do you shop on your own or with family? | 8.4 | 13 |

| 5 | Does your mood influence your shopping | 7.8 | 12 |

| 6 | Do you check expiry date for products? | 7.1 | 11 |

| 7 | Are you aware of the golden rules for shopping? | 7.1 | 11 |

| 8 | Is shopping influenced by offers, sales etc.? | 6.5 | 10 |

| 9 | Age | 5.2 | 8 |

| 10 | If no, would you like to learn more about small things that you should take into account in order to save money and reduce food wasting? | 5.2 | 8 |

| 11 | Are you aware that food wasting increases CO2 emissions and contributes to climate change? | 4.5 | 7 |

| 12 | If no, would you like to learn how you can help needy people and help fight climate change? | 4.5 | 7 |

| 13 | Number of members in household | 3.9 | 6 |

| 14 | Do you use a shopping list? | 3.9 | 6 |

| 15 | Do you know the rules for food storage and food wasting? | 3.9 | 6 |

| 16 | If no, would you like to learn more about small things about food storage and proper disposal of food waste so as to reduce waste and help combat climate change? | 3.2 | 5 |

| 17 | Do you separate food waste from other waste at home? | 3.2 | 5 |

| 18 | Do you know where you can donate food? | 2.6 | 4 |

| 19 | Would you be willing to donate food that you will not use before expiry date? | 2.6 | 4 |

| 20 | If no, would you like to learn some tips for effective storage, cooking and food processing that can save money and reduce food wasting? | 2.6 | 4 |

| 21 | Do you use food residues for preparing new meals? | 2.6 | 4 |

| 22 | Do you think that you generate a lot of food waste? | 2.6 | 4 |

| 23 | Shopping frequency | 1.9 | 3 |

| 24 | Do you know the golden rules for effective cooking? | 1.9 | 3 |

| 25 | Do you know the rules for food storage? | 1.9 | 3 |

| 26 | Do you use cooking recipes? | 1.9 | 3 |

| 27 | Do you know if there are people in need of food? | 1.3 | 2 |

| 28 | Do you put food waste in the corresponding bin? | 1.3 | 2 |

| 29 | Do you live in a town? | 0.6 | 1 |

| Question | Question | Missing Values (%) | Number of Missing Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | 48.8 | 21 |

| 2 | How often do you eat in restaurants? | 27.9 | 12 |

| 3 | Percentage of food waste that is dairy products | 18.6 | 8 |

| 4 | Percentage of food waste that is meat or fish | 18.6 | 8 |

| 5 | How likely is it that you will waste food because you ordered more than you needed? | 16.3 | 7 |

| 6 | How useful is the following for enhanced food waste prevention: economic incentives for donation of food suitable for human consumption | 16.3 | 7 |

| 7 | On the average what is the quantity of food wasted as nonedible? | 16.3 | 7 |

| 8 | How useful is the following for enhanced food waste prevention: information from social media? | 16.3 | 7 |

| 9 | How useful is the following for enhanced food waste prevention: economic incentives such as “pay as you throw” | 16.3 | 7 |

| 10 | Percentage of food waste that is fruits | 16.3 | 7 |

| 11 | Percentage of food waste that is ready meals | 14 | 6 |

| 12 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Share and donate food surplus rather than wasting it | 14 | 6 |

| 13 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Support local producers | 14 | 6 |

| 14 | How likely is it that you will waste food because the food prepared is not tasty? | 11.6 | 5 |

| 15 | The daily estimated food waste production in your household is | 11.6 | 5 |

| 16 | How likely is it that you will waste food because it does not have the texture, taste or appearance that you would like although it is safe to consume | 11.6 | 5 |

| 17 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Choose “ugly” fruits and vegetables as well | 11.6 | 5 |

| 18 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Adoption of healthy and sustainable nutrition practices | 11.6 | 5 |

| 19 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Understand food labeling | 11.6 | 5 |

| 20 | What percentage of the total household waste is food waste | 9.3 | 4 |

| 21 | How likely is it that you will waste food because you cooked more than you needed? | 9.3 | 4 |

| 22 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Consume more vegetables | 9.3 | 4 |

| 23 | Percentage of food waste that is vegetables | 9.3 | 4 |

| 24 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Store food properly | 9.3 | 4 |

| 25 | Percentage of food waste that is bread, cereals, bakery products | 9.3 | 4 |

| 26 | On the average what quantity of food waste is plate waste in your household? | 9.3 | 4 |

| 27 | How useful are the following tips proposed by FAO for food waste reduction? Buy only what you need | 7 | 3 |

| 28 | How many meals do you prepare weekly? | 7 | 3 |

| 29 | Do you know that “use by” label on a food product refers to the time until it may be safely consumed whereas the phrase “ best before” refers to the taste and texture of the product, which is still safe to consume? | 7 | 3 |

| 30 | Do you know that food wasting is responsible for the emission of a significant amount of greenhouse gases? | 7 | 3 |

| 31 | How useful is the following for enhanced food waste prevention: information from local government | 7 | 3 |

| 32 | How often do you order food delivery? | 4.7 | 2 |

| 33 | How likely is it that you will waste food because you forgot about it and it has been spoiled? | 4.7 | 2 |

| 34 | Do you agree with the declaration of consent to the processing of personal data? | 4.7 | 2 |

| 35 | Have you ever heard the term “food waste” or “food loss” or “organic food waste”? | 4.7 | 2 |

| 36 | How likely is it that you will waste food because it has expired? | 4.7 | 2 |

| 37 | Occupation | 4.7 | 2 |

| 38 | Do you participate in grocery shopping for your home? | 2.3 | 1 |

| 39 | When eating out, how often do you take leftovers in a packet?) | 2.3 | 1 |

| 40 | How often do you cook at home? | 2.3 | 1 |

| 41 | How likely is that you purchase products that are environmentally friendly compared with other products of the same type | 2.3 | 1 |

| 42 | Do you know if in the Municipality of Halandri there is separate collection of food waste using the brown bin? | 2.3 | 1 |

| 43 | Age groups | 2.3 | 1 |

| 44 | Household members | 2.3 | 1 |

References

- Thomsen, M.; Ahrné, L.; Ohlsson, T. Chapter 49—Sustainability and Food Systems. In Food Safety Management, 2nd ed.; Andersen, V., Lelieveld, H., Motarjemi, Y., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2023; pp. 1021–1039. ISBN 9780128200131. [Google Scholar]

- Commission Launches Consultation for Upcoming Circular Economy Act—Environment. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/news/commission-launches-consultation-upcoming-circular-economy-act-2025-08-01_en (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions a New Circular Economy Action Plan for a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52020DC0098 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Food Waste and Food Waste Prevention—Estimates. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Food_waste_and_food_waste_prevention_-_estimates (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Directive-EU-2025/1892-EN-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2025/1892/oj/eng (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Farm to Fork Strategy—Food Safety—European Commission. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- FAO Knowledge Repository. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/4a463cff-586d-433f-9124-af4b99246f91 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Regulation-178/2002-EN-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2002/178/oj/eng (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Abbade, E.B. Estimating the Nutritional Loss and the Feeding Potential Derived from Food Losses Worldwide. World Dev. 2020, 134, 105038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food Waste Matters—A Systematic Review of Household Food Waste Practices and Their Policy Implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Food Waste Index Report 2024. Think Eat Save: Tracking Progress to Halve Global Food Waste; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Publications-Waste-Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/waste/publications (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2017. Available online: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/1043688/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Zhang, X.Q. The Trends, Promises and Challenges of Urbanisation in the World. Habitat Int. 2016, 54, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casonato, C.; García-Herrero, L.; Caldeira, C.; Sala, S. What a Waste! Evidence of Consumer Food Waste Prevention and Its Effectiveness. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 41, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive-2008/98-EN-Waste Framework Directive-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/98/oj/eng (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Soloha, R.; Dace, E. Research on Quantification of Food Loss and Waste in Europe: A Systematic Literature Review and Synthesis of Methodological Limitations. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2025, 28, 200287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicarelli, V.; Bux, C. Food Waste Measurement toward a Fair, Healthy and Environmental-Friendly Food System: A Critical Review. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 2907–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, E.G.; Chroni, C.; Boikou, K.; Abeliotis, K.; Panagiotakos, D.; Lasaridi, K. Quantification of Household Food Waste in Greece to Establish the 2021 National Baseline and Methodological Implications. Waste Manag. 2024, 190, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeaka, H.; Akinsemolu, A.; Miri, T.; Nnaji, N.D.; Duan, K.; Pang, G.; Tamasiga, P.; Khalid, S.; Al-Sharify, Z.T.; Ugwa, C. Artificial Intelligence in Food System: Innovative Approach to Minimizing Food Spoilage and Food Waste. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harikrishnan, S.; Kaushik, D.; Rasane, P.; Kumar, A.; Kaur, N.; Reddy, C.K.; Proestos, C.; Oz, F.; Kumar, M. Artificial Intelligence in Sustainable Food Design: Technological, Ethical Consideration, and Future. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 163, 105152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus+. Available online: https://erasmus-plus.ec.europa.eu/projects/search/details/2022-2-DE02-KA210-ADU-000098503 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- An Innovative Collaborative Circular Food System to Reduce Food Waste and Losses in the Agri-Food Chain. FOODRUS. Project. Fact Sheet. H2020. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/101000617 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- De Laurentiis, V.; Corrado, S.; Sala, S. Quantifying Household Waste of Fresh Fruit and Vegetables in the EU. Waste Manag. 2018, 77, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papamonioudis, K.; Zabaniotou, A. Exploring Greek Citizens’ Circular Thinking on Food Waste Recycling in a Circular Economy—A Survey-Based Investigation. Energies 2022, 15, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMLEH-Publications-10 Golden Rules to Prevent Food Waste. Available online: https://www.bmleh.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/Publications/zgfdt-10rulespreventfoodwaste.html (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Identifying Motivations and Barriers to Minimising Household Food Waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 84, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritikou, T.; Panagiotakos, D.; Abeliotis, K.; Lasaridi, K. Investigating the Determinants of Greek Households Food Waste Prevention Behaviour. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, P.; Zacharatos, T.; Boukouvala, V. Consumer Behaviour and Household Food Waste in Greece. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 965–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Buuren, S.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. Mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K.P. Machine Learning: A Probabilistic Perspective; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; ISBN 9780262304320. [Google Scholar]

- Ponis, S.T.; Papanikolaou, P.-A.; Katimertzoglou, P.; Ntalla, A.C.; Xenos, K.I. Household Food Waste in Greece: A Questionnaire Survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, B.; Bokelmann, W. Explorative Study about the Analysis of Storing, Purchasing and Wasting Food by Using Household Diaries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungowska, J.; Kulczyński, B.; Sidor, A.; Gramza-Michałowska, A. Assessment of Factors Affecting the Amount of Food Waste in Households Run by Polish Women Aware of Well-Being. Sustainability 2021, 13, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herpen, E.; Van Der Lans, I.A.; Holthuysen, N.; Nijenhuis-de Vries, M.; Quested, T.E. Comparing Wasted Apples and Oranges: An Assessment of Methods to Measure Household Food Waste. Waste Manag. 2019, 88, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.L.; Gibson, K.E.; Ricke, S.C. Critical Factors and Emerging Opportunities in Food Waste Utilization and Treatment Technologies. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 781537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hooge, I.E.; Oostindjer, M.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Normann, A.; Loose, S.M.; Almli, V.L. This Apple Is Too Ugly for Me! Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 56, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloysius, N.; Ananda, J.; Mitsis, A.; Pearson, D. Why People Are Bad at Leftover Food Management? A Systematic Literature Review and a Framework to Analyze Household Leftover Food Waste Generation Behavior. Appetite 2023, 186, 106577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, H.; Stelloh, T.D.; Schleyerbach, U.; Bornkessel, S. Food Upcycling Focusing on Private Households: The Potential of Food Upcycling in Rural Areas. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1662557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim Ghani, W.A.W.A.; Rusli, I.F.; Biak, D.R.A.; Idris, A. An Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Study the Influencing Factors of Participation in Source Separation of Food Waste. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Z.; Toth, J.D. Global Primary Data on Consumer Food Waste: Rate and Characteristics—A Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, B.; Hofmann, E. To Sort or Not to Sort?—Consumers’ Waste Behavior in Public. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 475, 143677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; De Hooge, I.; Amani, P.; Bech-Larsen, T.; Oostindjer, M. Consumer-Related Food Waste: Causes and Potential for Action. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6457–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merian, S.; O’Sullivan, K.; Stöckli, S.; Beretta, C.; Müller, N.; Tiefenbeck, V.; Fleisch, E.; Natter, M. A Field Experiment to Assess Barriers to Accurate Household Food Waste Measurements. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 206, 107644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, J.; Karunasena, G.G.; Kansal, M.; Mitsis, A.; Pearson, D. Quantifying the Effects of Food Management Routines on Household Food Waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 391, 136230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2021 Population-Housing Census—ELSTAT. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/en/2021-census-pop-hous (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Falasconi, L.; Cicatiello, C.; Franco, S.; Segrè, A.; Setti, M.; Vittuari, M. Such a Shame! A Study on Self-Perception of Household Food Waste. Sustainability 2019, 11, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.; Goucher, L.; Quested, T.; Bromley, S.; Gillick, S.; Wells, V.K.; Evans, D.; Koh, L.; Carlsson Kanyama, A.; Katzeff, C.; et al. Review: Consumption-Stage Food Waste Reduction Interventions—What Works and How to Design Better Interventions. Food Policy 2019, 83, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, J.; Carvalho, A.; Gaspar De Matos, M. How to Influence Consumer Food Waste Behavior with Interventions? A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, Q.D.; Muth, M.K. Cost-Effectiveness of Four Food Waste Interventions: Is Food Waste Reduction a “Win–Win?”. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agya, B.A. Technological Solutions and Consumer Behaviour in Mitigating Food Waste: A Global Assessment across Income Levels. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 55, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Barka-Papadimitriou, A.; Lyberatos, V.; Desiotou, E.; Efthimiou, K.; Lyberatos, G. A Machine Learning Approach for the Completion, Augmentation and Interpretation of a Survey on Household Food Waste Management. Processes 2026, 14, 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020302

Barka-Papadimitriou A, Lyberatos V, Desiotou E, Efthimiou K, Lyberatos G. A Machine Learning Approach for the Completion, Augmentation and Interpretation of a Survey on Household Food Waste Management. Processes. 2026; 14(2):302. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020302

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarka-Papadimitriou, Athanasia, Vassilis Lyberatos, Eleni Desiotou, Kostas Efthimiou, and Gerasimos Lyberatos. 2026. "A Machine Learning Approach for the Completion, Augmentation and Interpretation of a Survey on Household Food Waste Management" Processes 14, no. 2: 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020302

APA StyleBarka-Papadimitriou, A., Lyberatos, V., Desiotou, E., Efthimiou, K., & Lyberatos, G. (2026). A Machine Learning Approach for the Completion, Augmentation and Interpretation of a Survey on Household Food Waste Management. Processes, 14(2), 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020302