The reactive power–voltage droop link helps grid-forming converters dynamically adjust reactive output and stabilize system voltage. However, retaining this link during faults boosts the converter’s reactive output, forcing its internal potential to drop and weakening its reactive support capability.

After analyzing this underlying mechanism, this section proposes a reactive power support method that freezes the reactive power–voltage droop link. It uses positive-sequence voltage amplitude to detect system faults and determine whether to freeze the link—enhancing the converter’s reactive support during voltage dips while avoiding post-fault overvoltage risks caused by prolonged droop freezing.

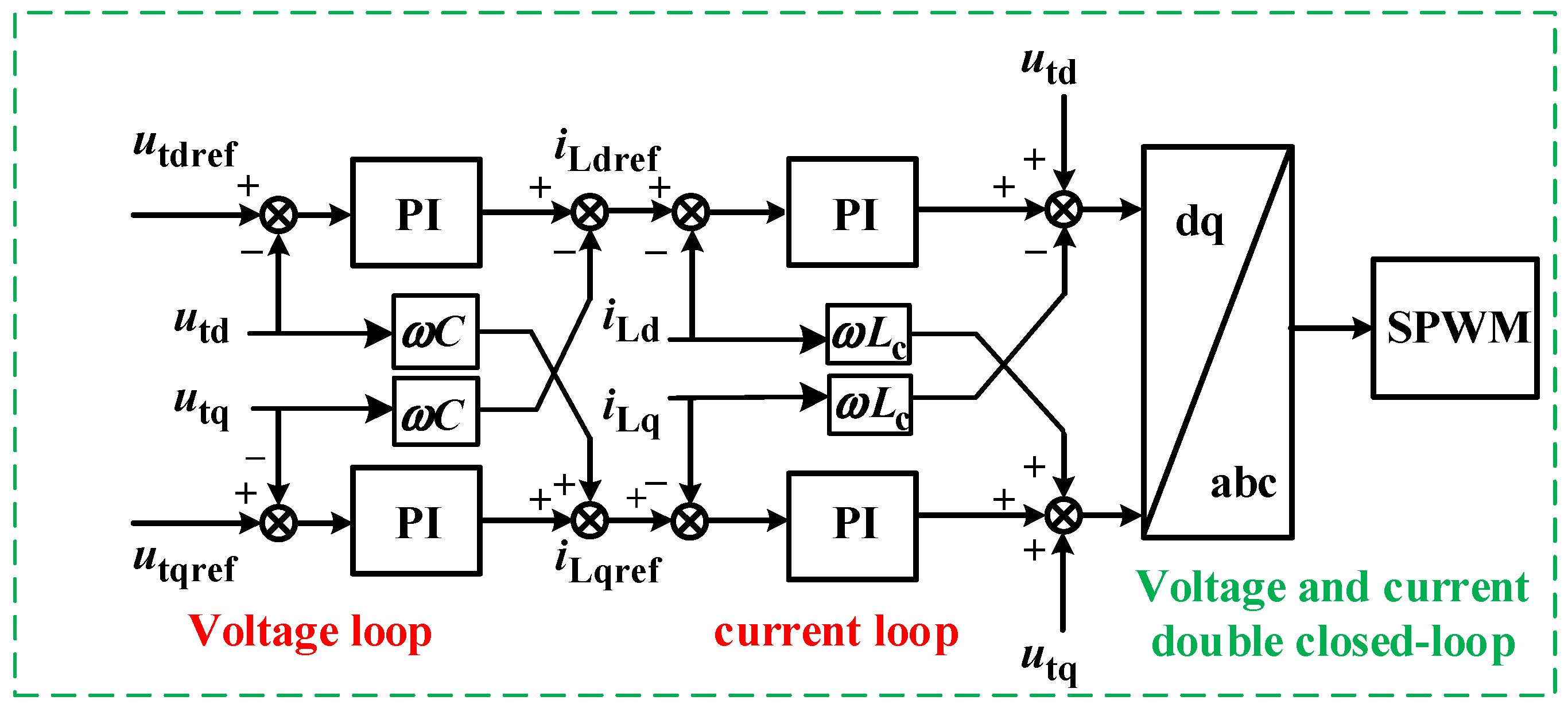

4.1. Mechanism Analysis of Droop Control Link Affecting Reactive Power Support Capability

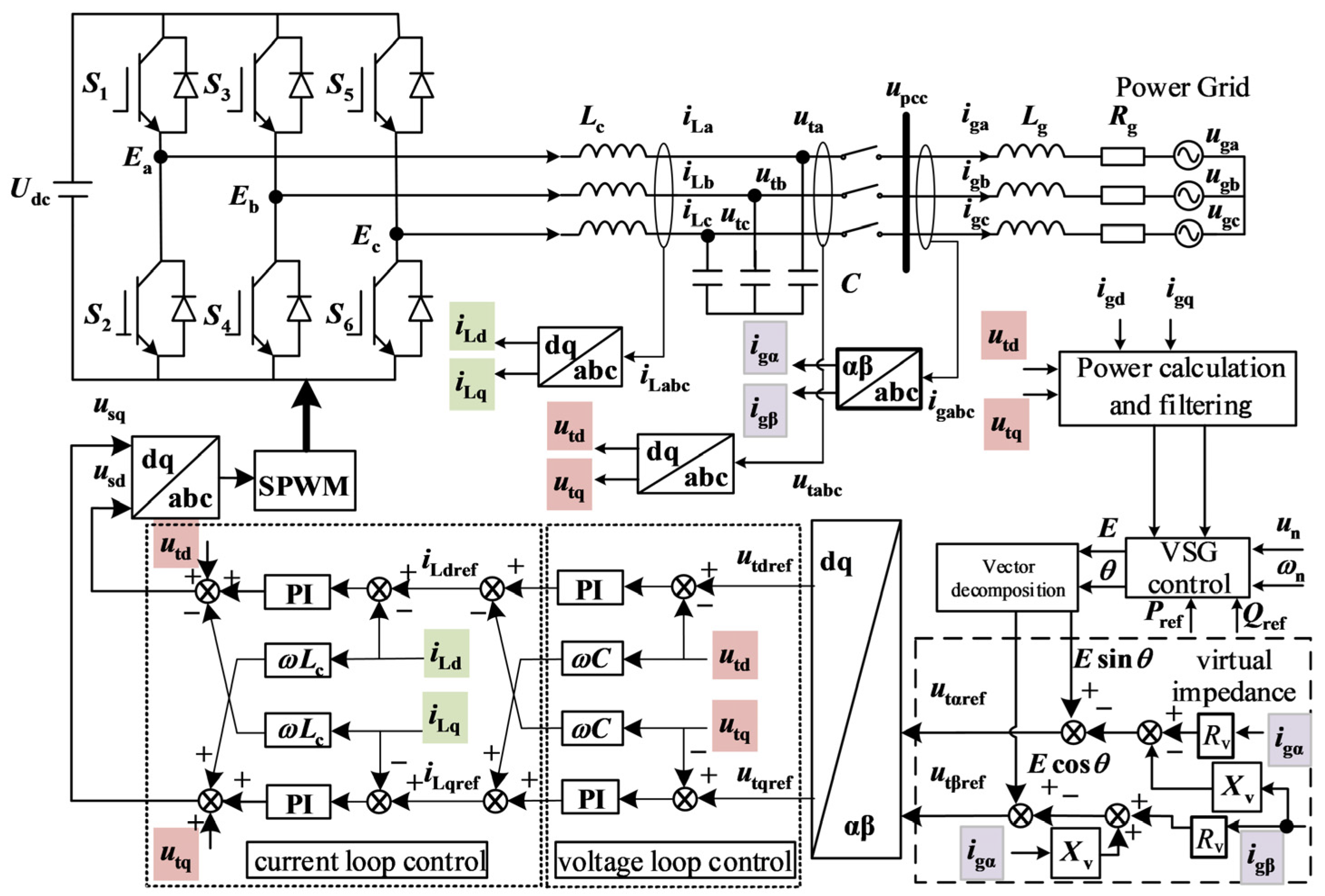

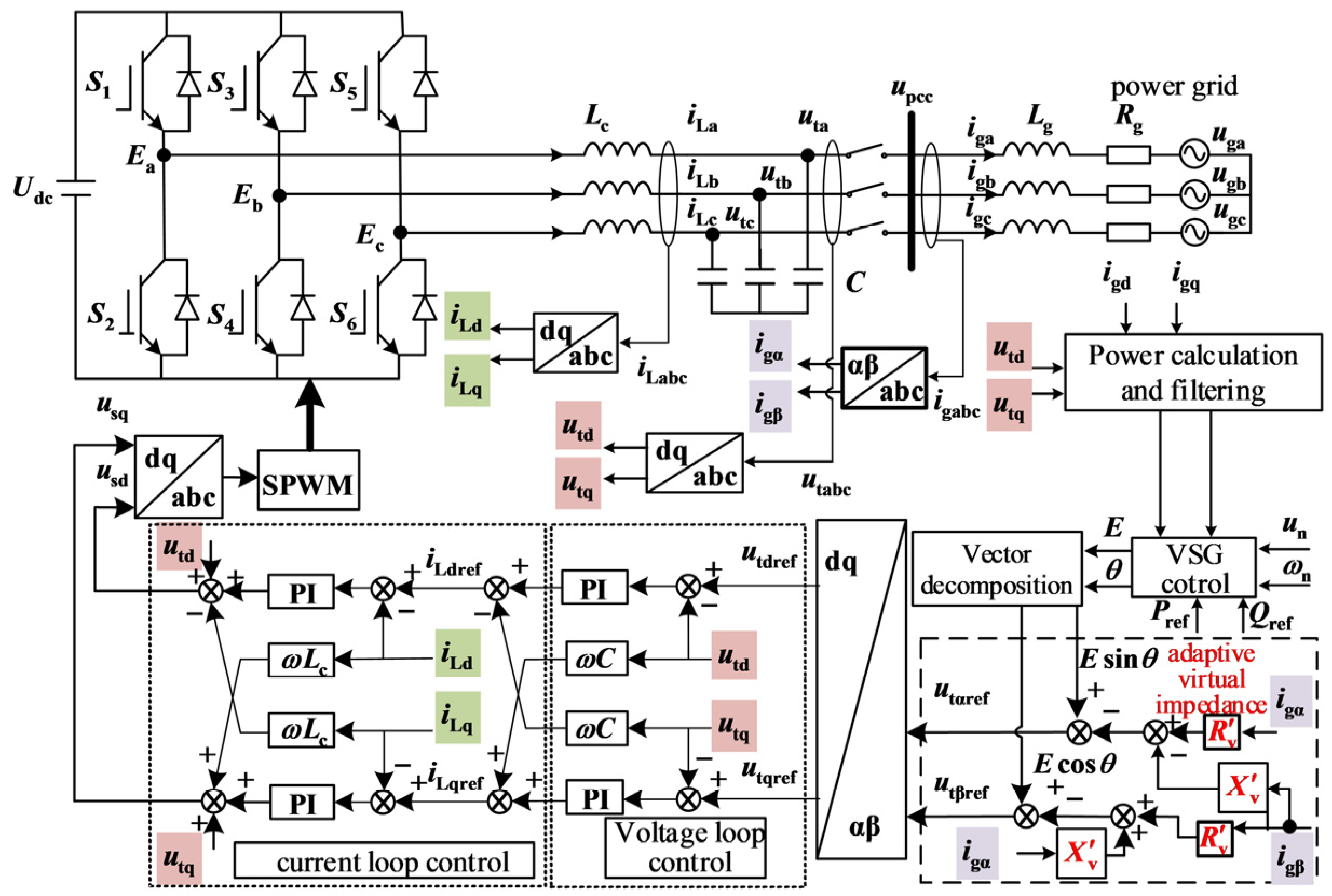

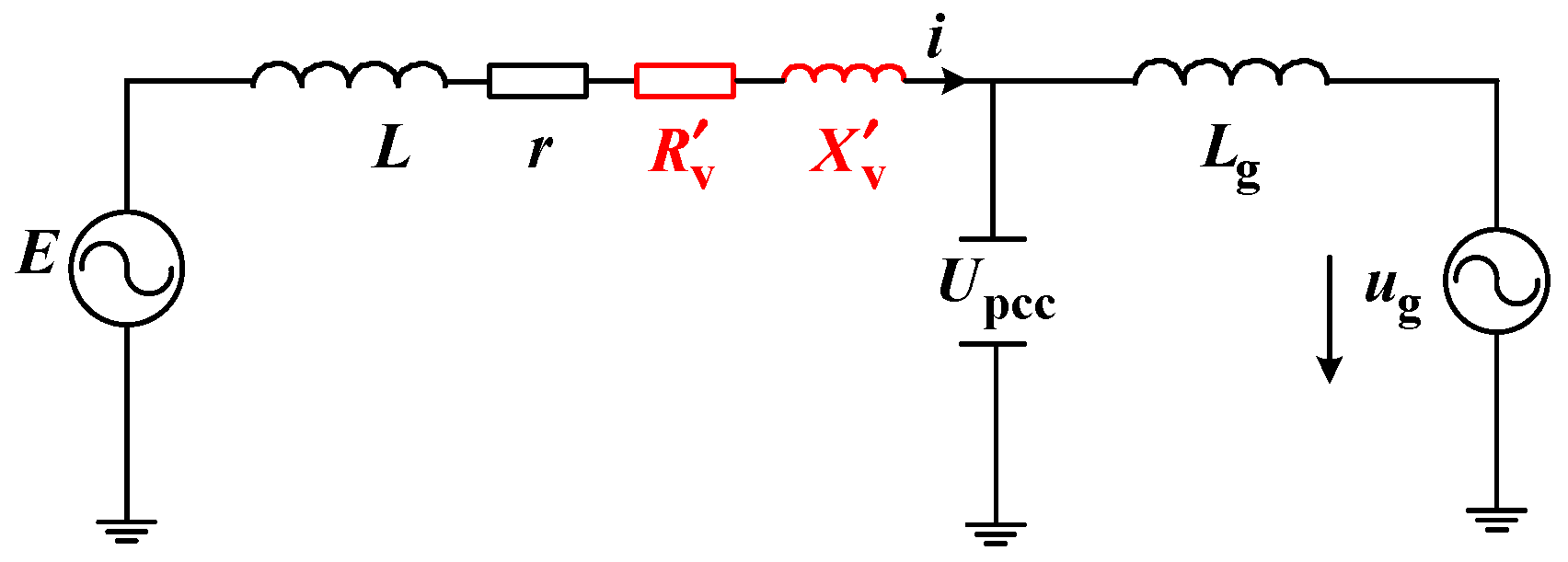

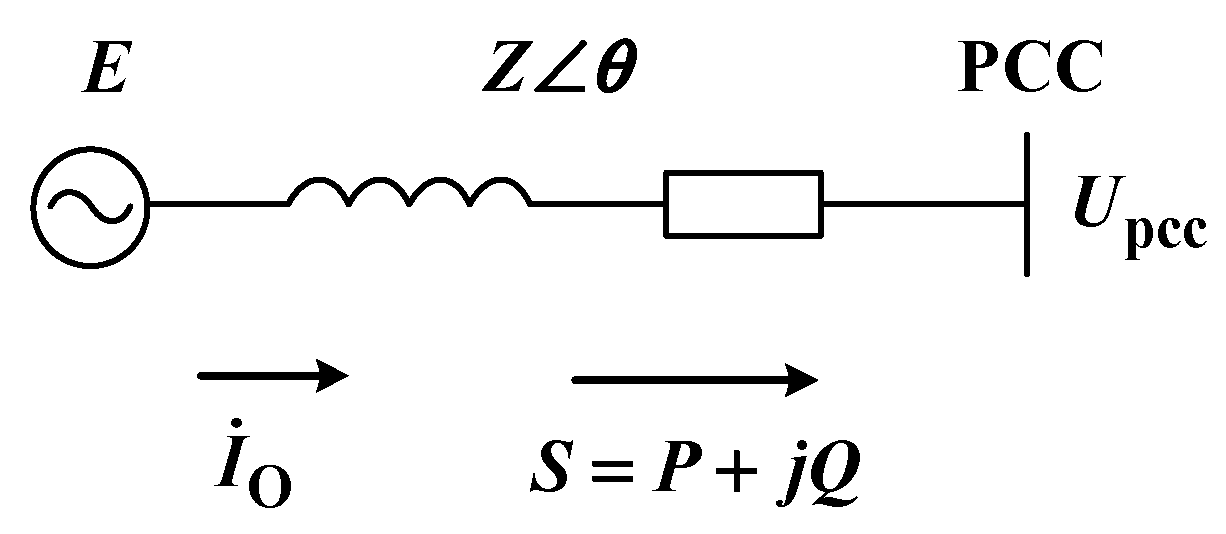

The output of the grid-connected converter can be equivalent to the circuit structure shown in

Figure 20. In the figure,

UPCC represents the voltage at the PCC point, with its phase angle set as the reference phase angle;

E represents the output voltage of the grid-connected converter port;

Z∠

θ represents the equivalent impedance from the converter to the PCC point;

S represents the complex power flowing into the PCC point; and

represents the output current of the converter.

At this time,

can be expressed as

The complex power

S injected by the converter into the grid-side system can be expressed as

By substituting Formula (41) into Formula (42), we can get

When the system is in a purely inductive environment,

X >>

R,

R ≈ 0, and the formula can be simplified to

Generally, considering that the value of is small, it can be approximately considered that .

At this time, Formula (44) is transformed into

Assuming

, taking the differential of Equation (45) yields

At this time, the active power P output by the converter mainly depends on the power angle difference, and the reactive power Q mainly depends on the voltage amplitude E, with almost no coupling relationship.

At this time, the reactive power output by the converter can be expressed as follows:

As Q increases, E also increases. This equation indicates that VSG can support voltage during a fault by providing more reactive power to the grid.

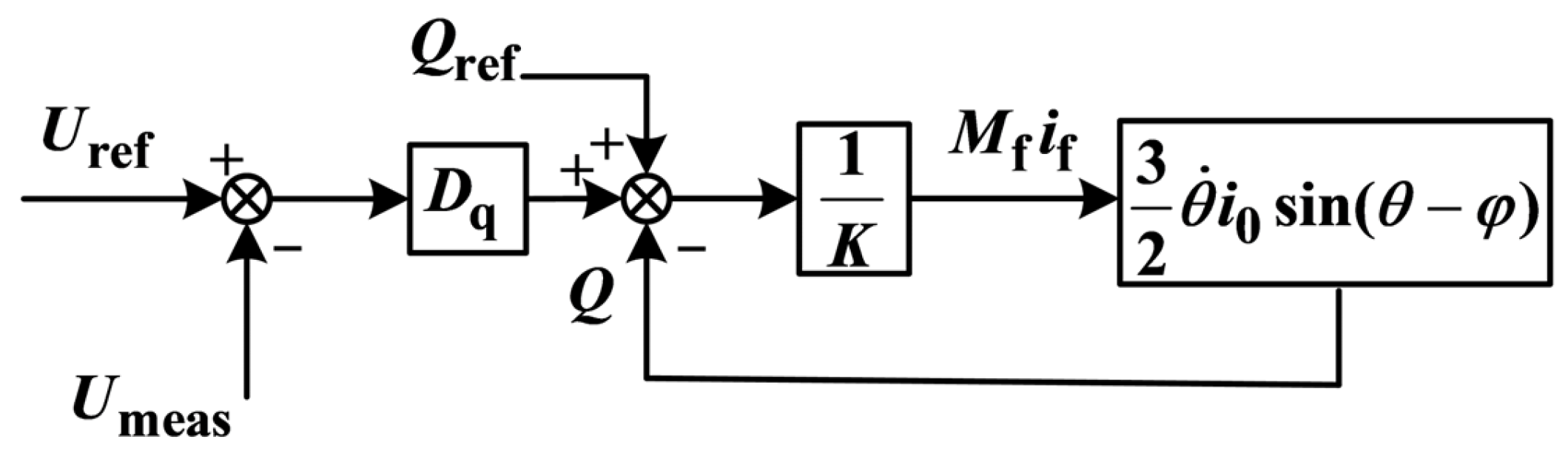

However, the VSG output voltage is controlled by the reactive droop link, and the expression for reactive droop control is

By transforming Equation (48), we can obtain the expression for the reactive power output by the VSG:

Grid voltage dips create a potential difference between the VSG’s internal potential and grid voltage, leading to a natural rise in the VSG’s reactive power output. Retaining the reactive droop link at this point introduces reactive power negative feedback, which lowers the internal potential E and reduces reactive output—hindering the inverter’s grid reactive support.

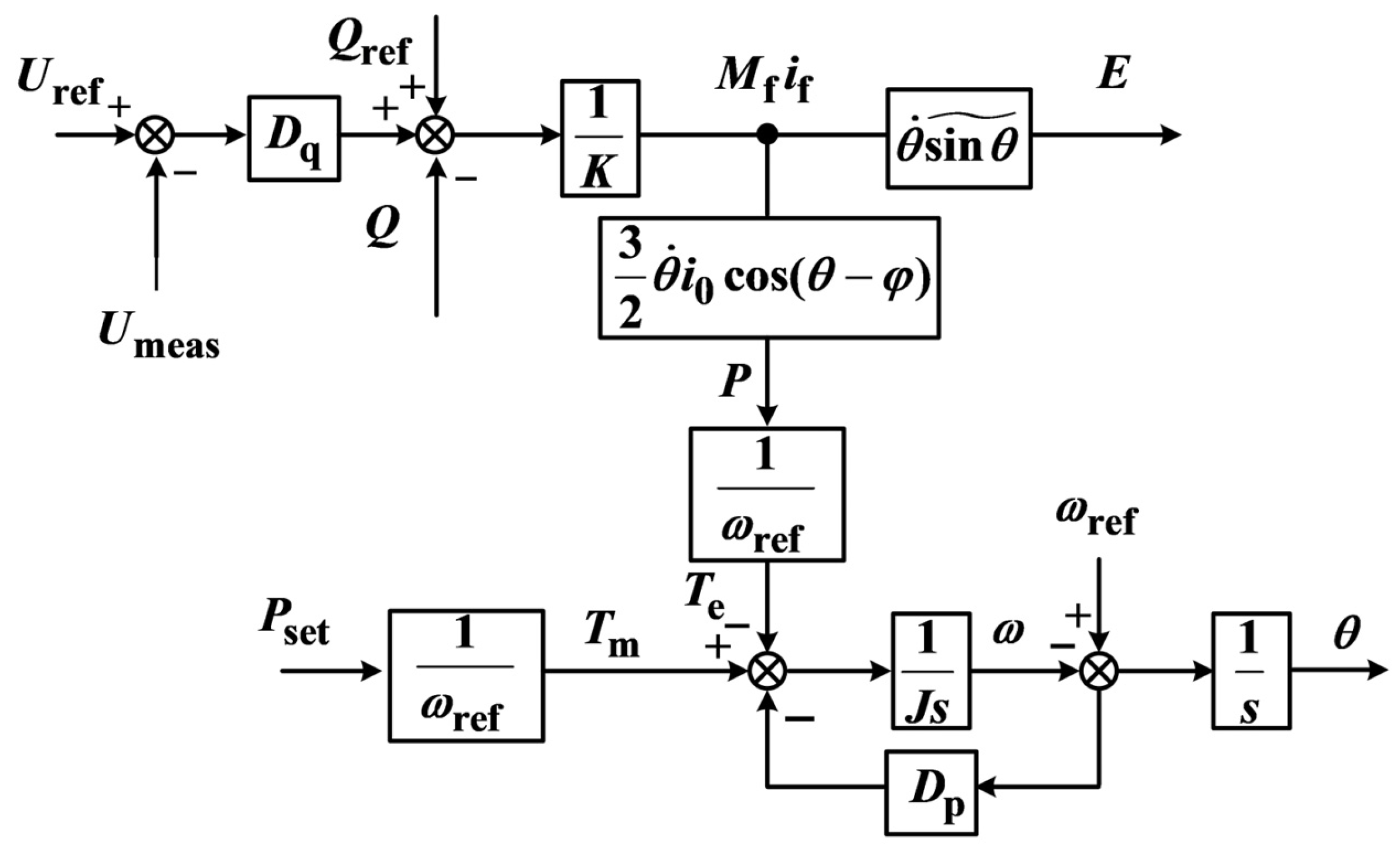

4.2. Principle of Reactive Power Support Based on Frozen Droop Control

This method uses the positive-sequence component of the grid voltage as the condition for fault identification. When the amplitude of the positive-sequence voltage is less than 0.9 p.u., it is determined that a voltage sag fault has occurred in the grid, and the reactive power droop control link is frozen. When the amplitude of the positive-sequence voltage is greater than 0.9 p.u., it is determined that the fault has been cleared, and the reactive droop control link is restarted.

The formula for VSG output voltage is

The voltage equation of VSG under droop control is

where

K is the reactive power loop inertia coefficient;

is the voltage droop coefficient.

Transforming Equation (51) yields

The two formulas are equivalent; thus,

is the phase angle difference between the internal electromotive force E and the point of common coupling (PCC) voltage U, and ω0 is the rated angular frequency of the power grid. This formula indicates that the traditional method of freezing the reactive power loop during a fault can be improved by stabilizing the value of

Mfif. By setting

Mfif to a fixed value of

KG, Equation (50) will be transformed into

Equation (8) will be transformed into

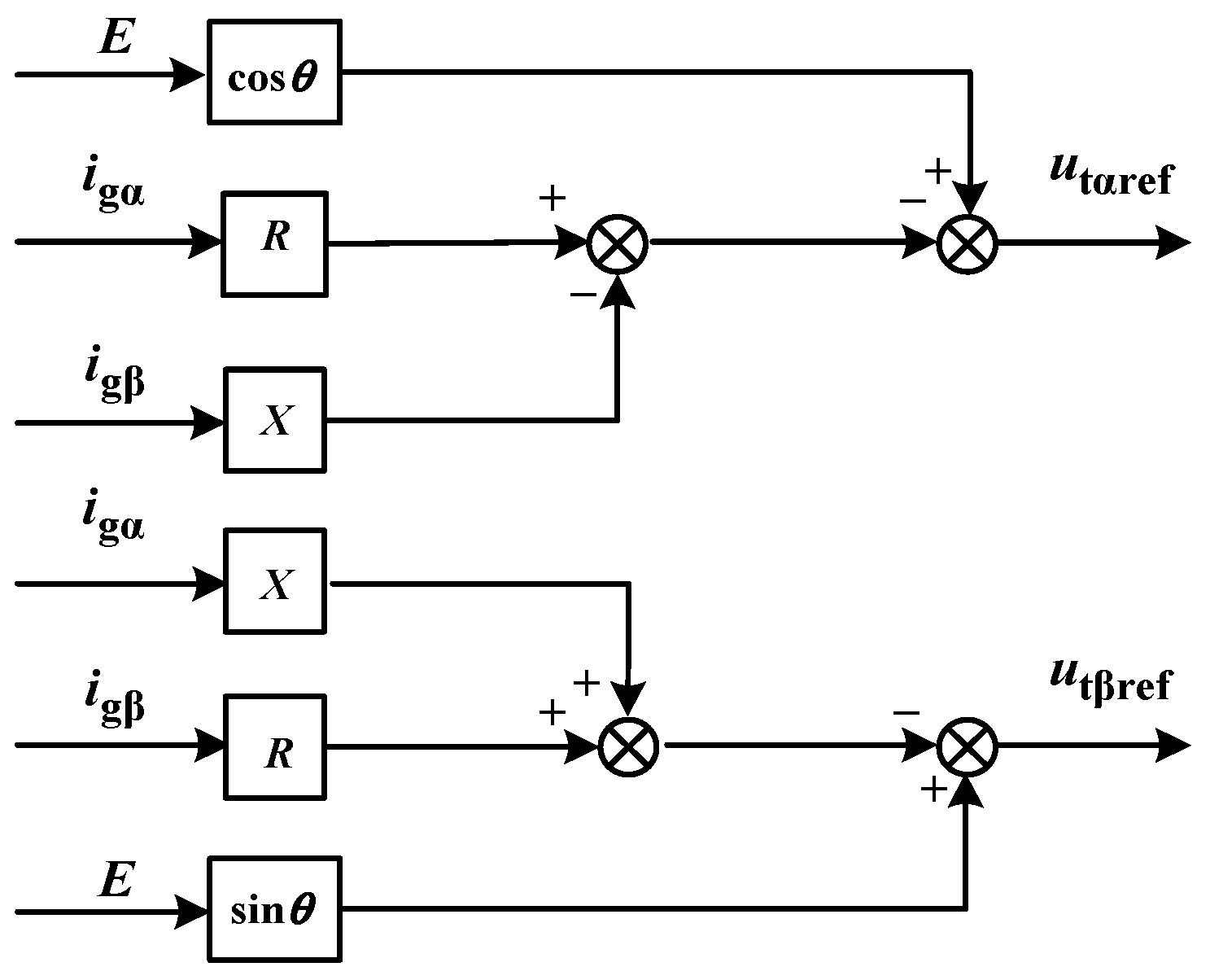

Without voltage-reactive negative feedback regulation, the new KG value during LVRT simultaneously enhances voltage and reactive power output. Physically, Mfif is the VSG’s magnetic flux; this method essentially freezes the reactive-voltage droop link and increases magnetic flux to raise the VSG’s internal potential, expanding the internal-grid potential difference for higher reactive output. Notably, raising internal potential during faults exacerbates overcurrent, so the strategy must be paired with adaptive virtual impedance overcurrent suppression to prevent current over-limit under severe voltage dips.

This study adopts the “Synchronous Reference Frame (SRF)-based positive-sequence extraction method” for fault detection.

The process involves transforming the three-phase PCC voltage uabc into αβ-frame voltages via Clark transformation then converting them into dq-frame components ud, uq using SRF transformation synchronized with the grid’s rated angular frequency ω0. These components are low-pass-filtered (5 Hz cutoff) to eliminate interference, obtaining the positive-sequence voltage amplitude . Droop control is frozen when U1 < 0.9 p.u. and restored otherwise.

(1) Small-signal modeling: Substitute frozen droop control into the VSG small-signal model, derive the characteristic equation, and analyze the impact of Dq on the system’s dominant poles.

(2) Results: When Dq = 5, the real part of the dominant pole = −0.12. When Dq = 10, the real part of the dominant pole = −0.28. When Dq > 15, the real part of the dominant pole = −0.05. Thus, Dq = 10 is selected to balance stability margin and response speed.

4.3. Simulation Verification of Improved Reactive Power Support Method

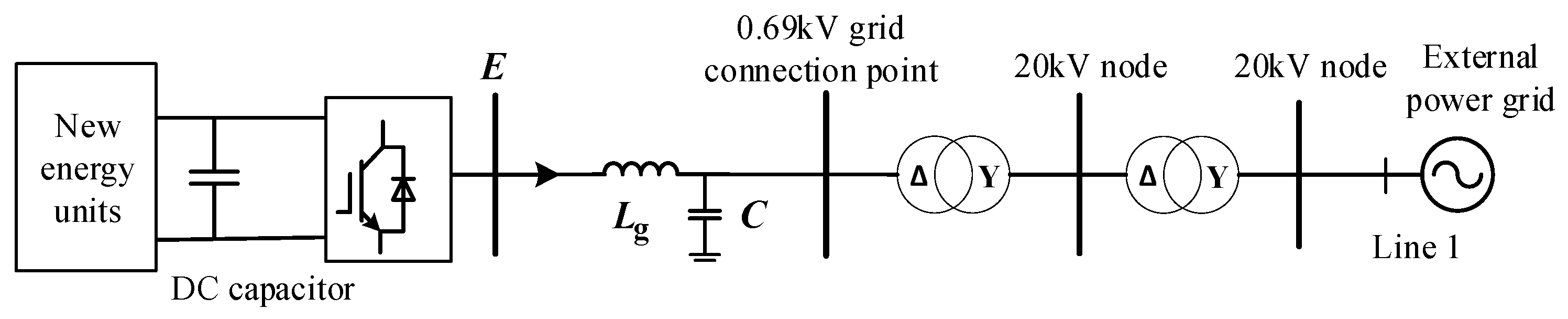

The system simulation model depicted in

Figure 7 and the parameters listed in

Table 1 were utilized. The effectiveness of the proposed reactive power support method was validated by simulating three different voltage sag conditions: mild, moderate, and severe.

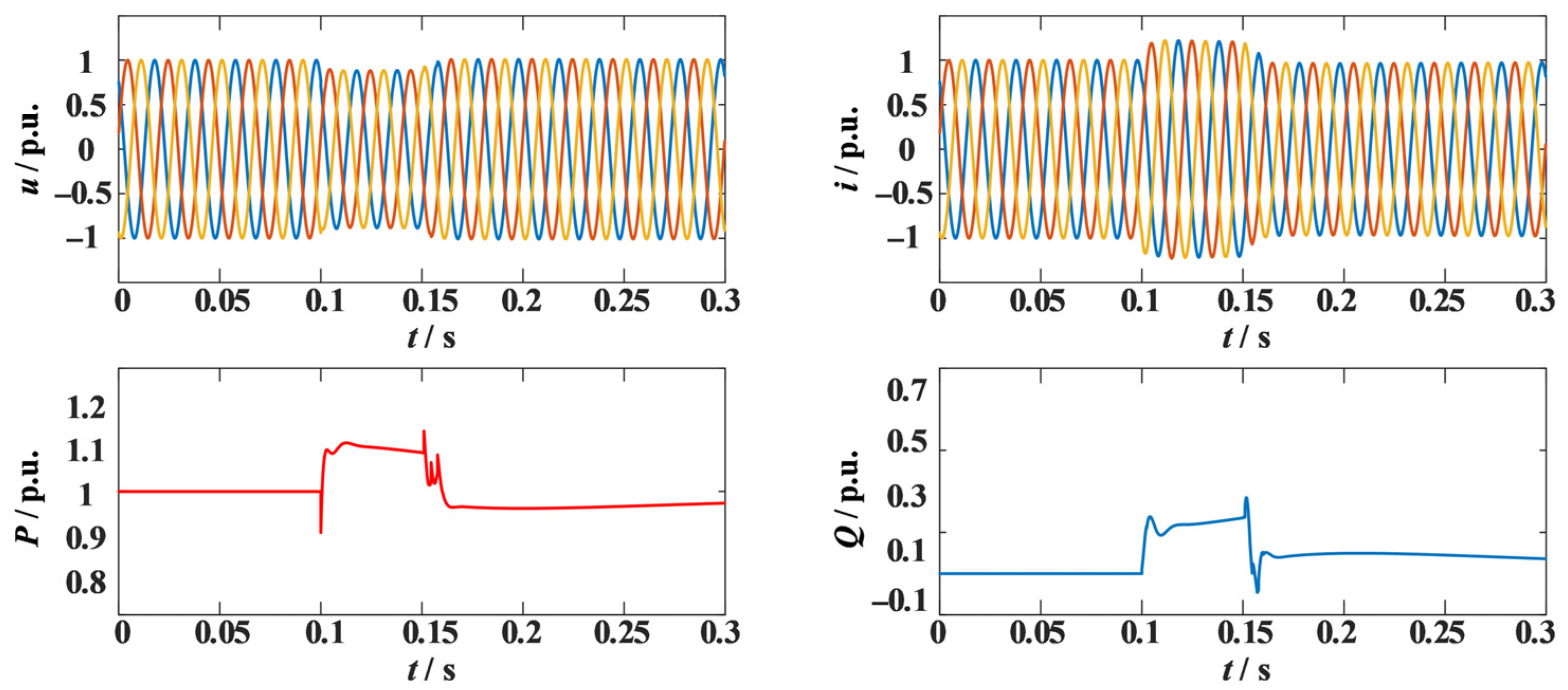

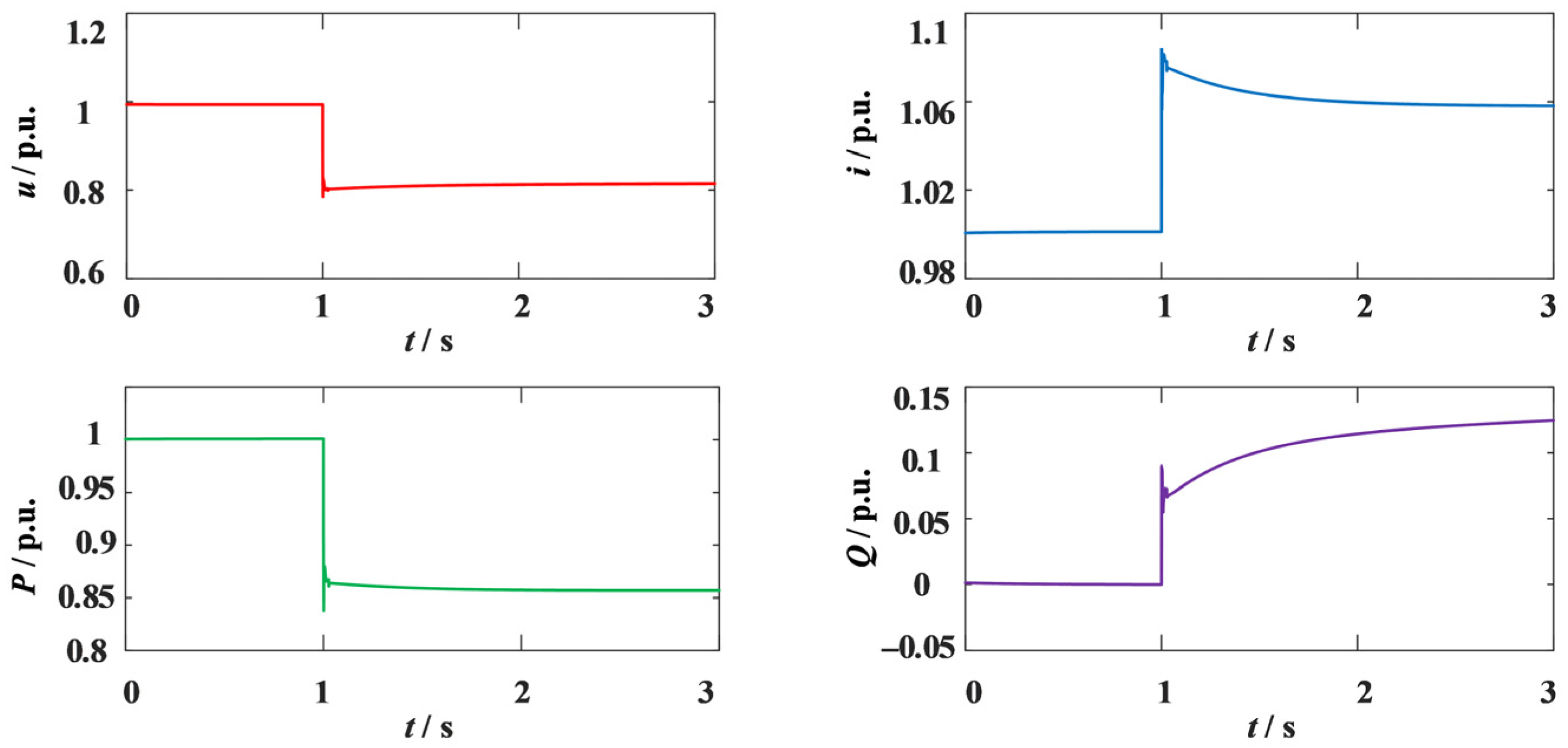

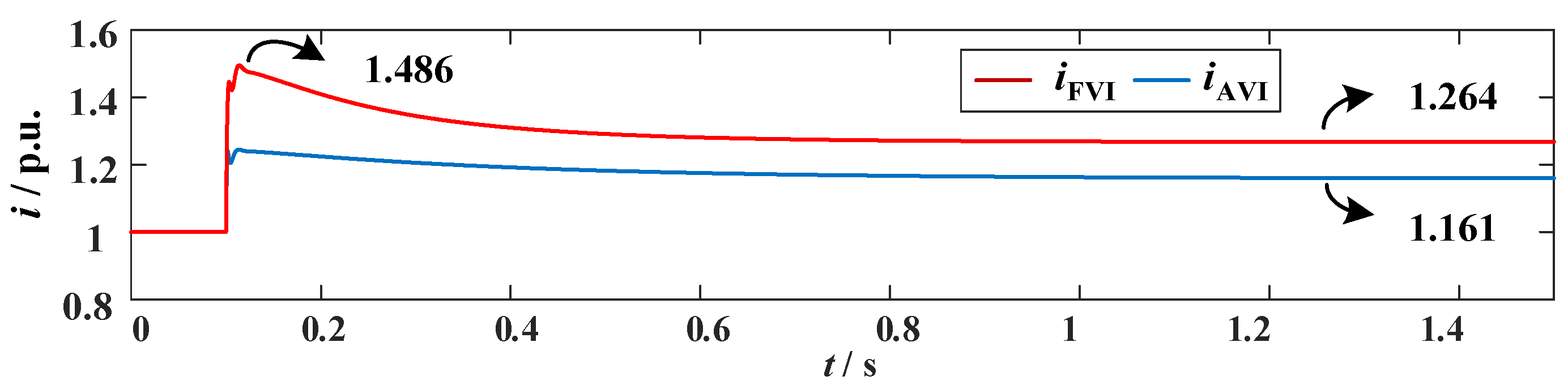

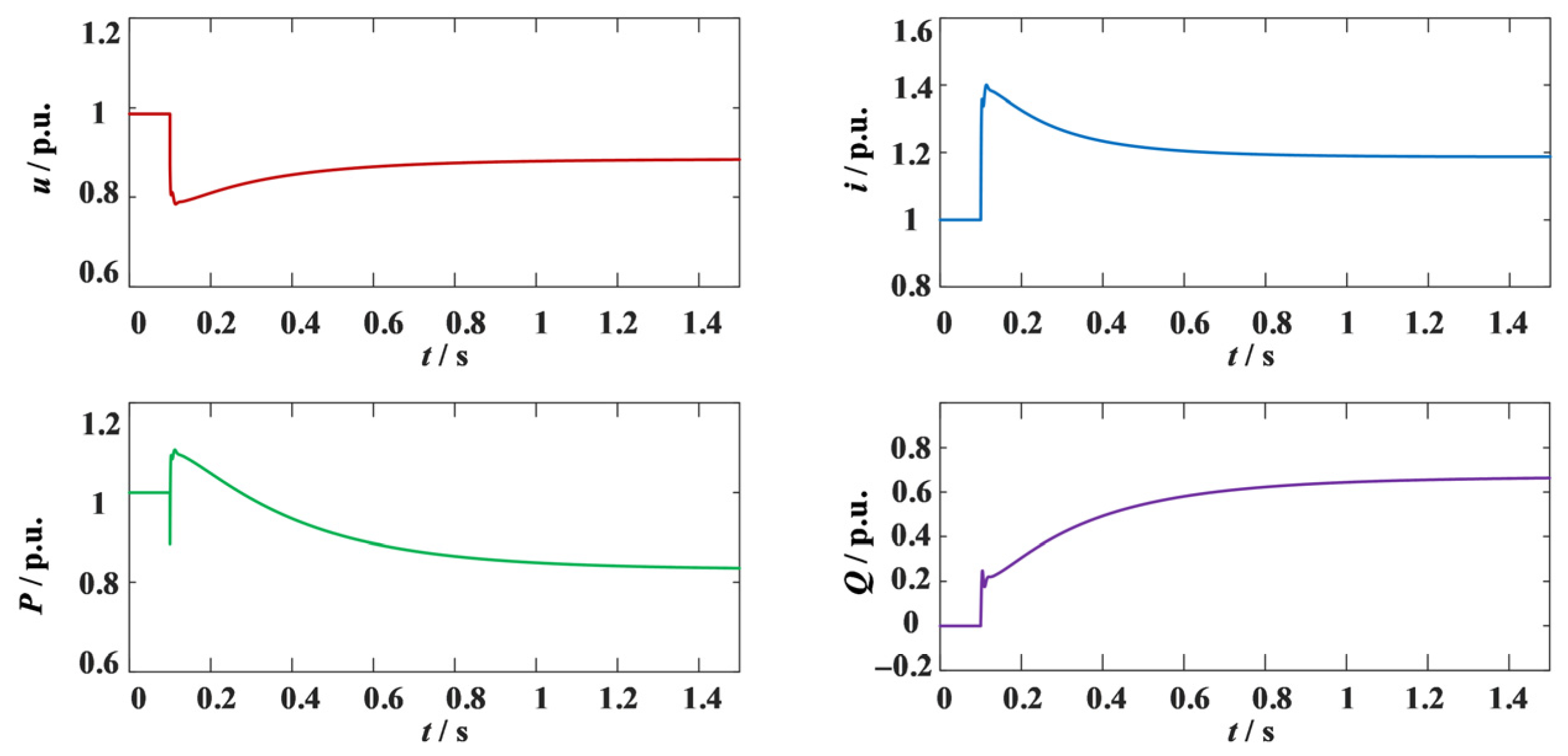

(1) Operating condition 1: mild voltage drop (voltage drop to 70–90%)

A three-phase short-circuit fault occurs at 10% of line 1 at 0.1 s, with a transition impedance of 0.5 +

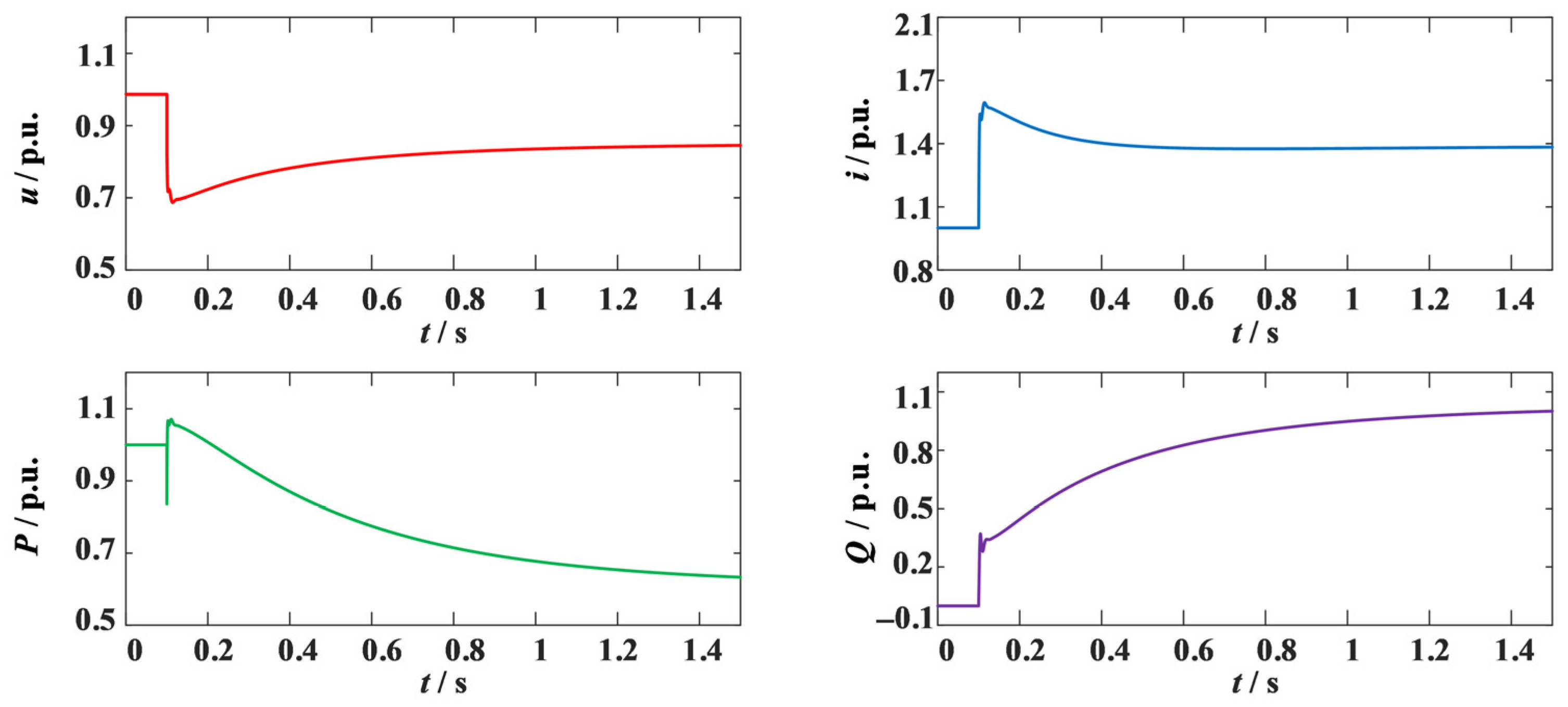

j0.5 Ω. When the reactive power–voltage droop control link is not frozen during the fault, the grid voltage, current, and power conditions are shown in

Figure 21.

After the fault, the grid-tie point voltage dropped to a minimum of 0.7894 p.u., while the converter reactive power continued to rise to 0.6654 p.u. at 1.45 s. Meanwhile, the grid-tie point current remained above 1.2 p.u. for a long time, posing an overcurrent risk to the converter.

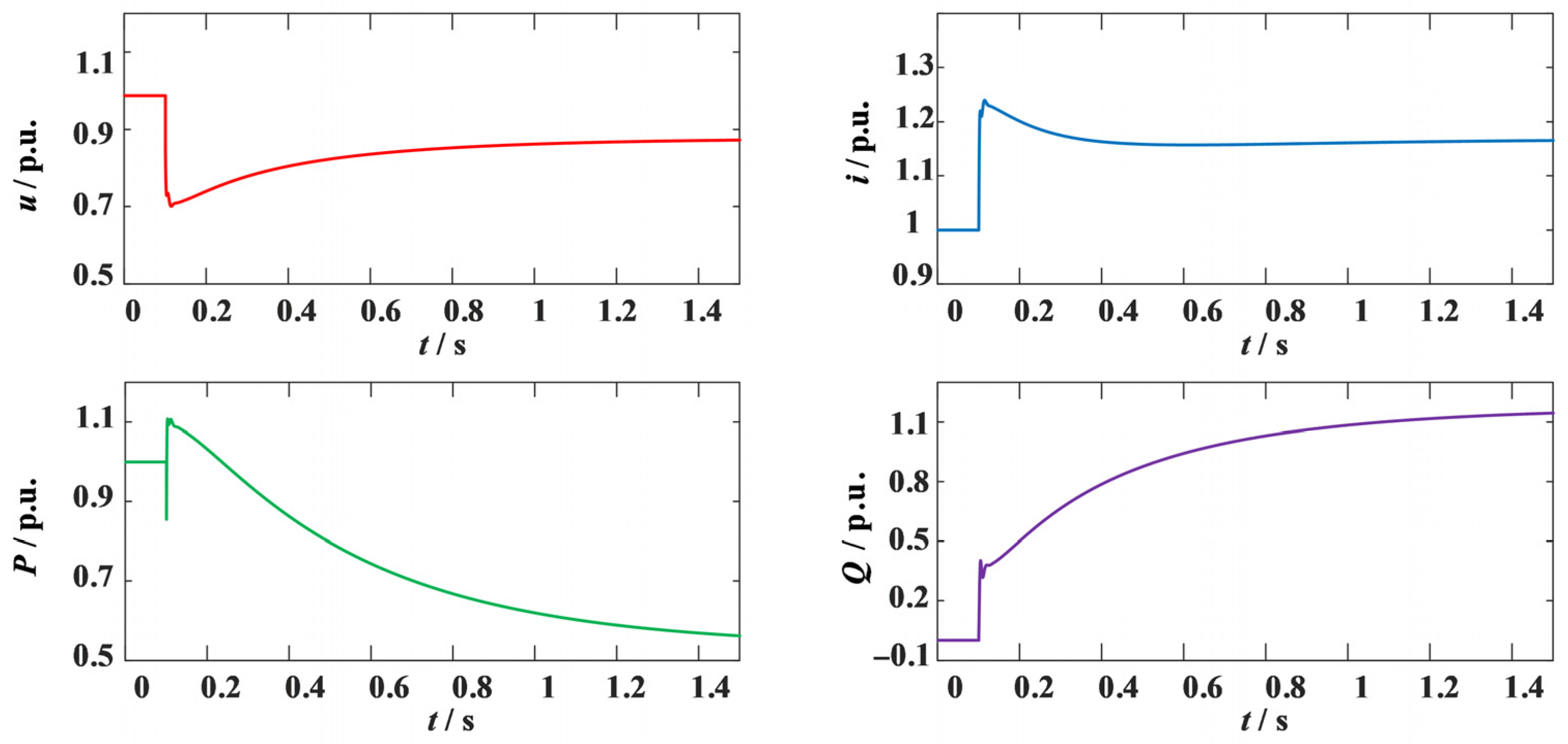

With the proposed fault overcurrent suppression and reactive support method, when the voltage was detected below 0.9 p.u., the reactive-voltage droop control was frozen (KG = 1.014). The adaptive virtual impedance method was adopted with the following parameters: Rv = 0.5 p.u., Xv = 0.1 p.u., additional resistance coefficient Kr = 1.5, additional reactance coefficient Kx = 1.5, and preset current threshold Ilim = 1.05 p.u. The grid-tie point voltage, current, and active and reactive power results are shown in

Figure 22.

As shown in

Figure 22, after using the improved method of fault overcurrent suppression and reactive power support, the adaptive virtual impedance suppresses the fault current and protects the system from overcurrent damage. The improved method of reactive power support freezes the reactive-voltage droop control structure and adjusts the value of

KG to increase the reactive power output of the converter. At 1.45 s, the reactive power increases from 0.6654 p.u. to 0.7431 p.u., an increase of 11.68%. Without the risk of overcurrent, the converter provides more sufficient reactive power support. The steady-state current THD is 2.3%, and the frozen droop control does not increase current harmonics.

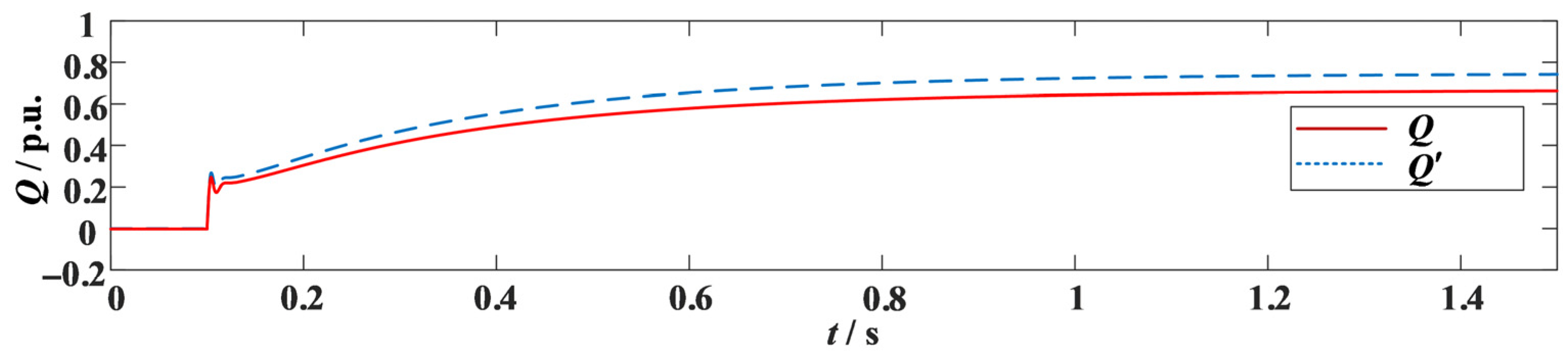

The comparison of reactive power at this time is shown in

Figure 23. The blue dashed line represents the reactive power output by the converter under the improved method, and the red solid line represents the reactive power output by the converter when the reactive-voltage droop control is not frozen. After freezing the reactive-voltage droop control during a fault, the converter outputs more reactive power to support the terminal voltage.

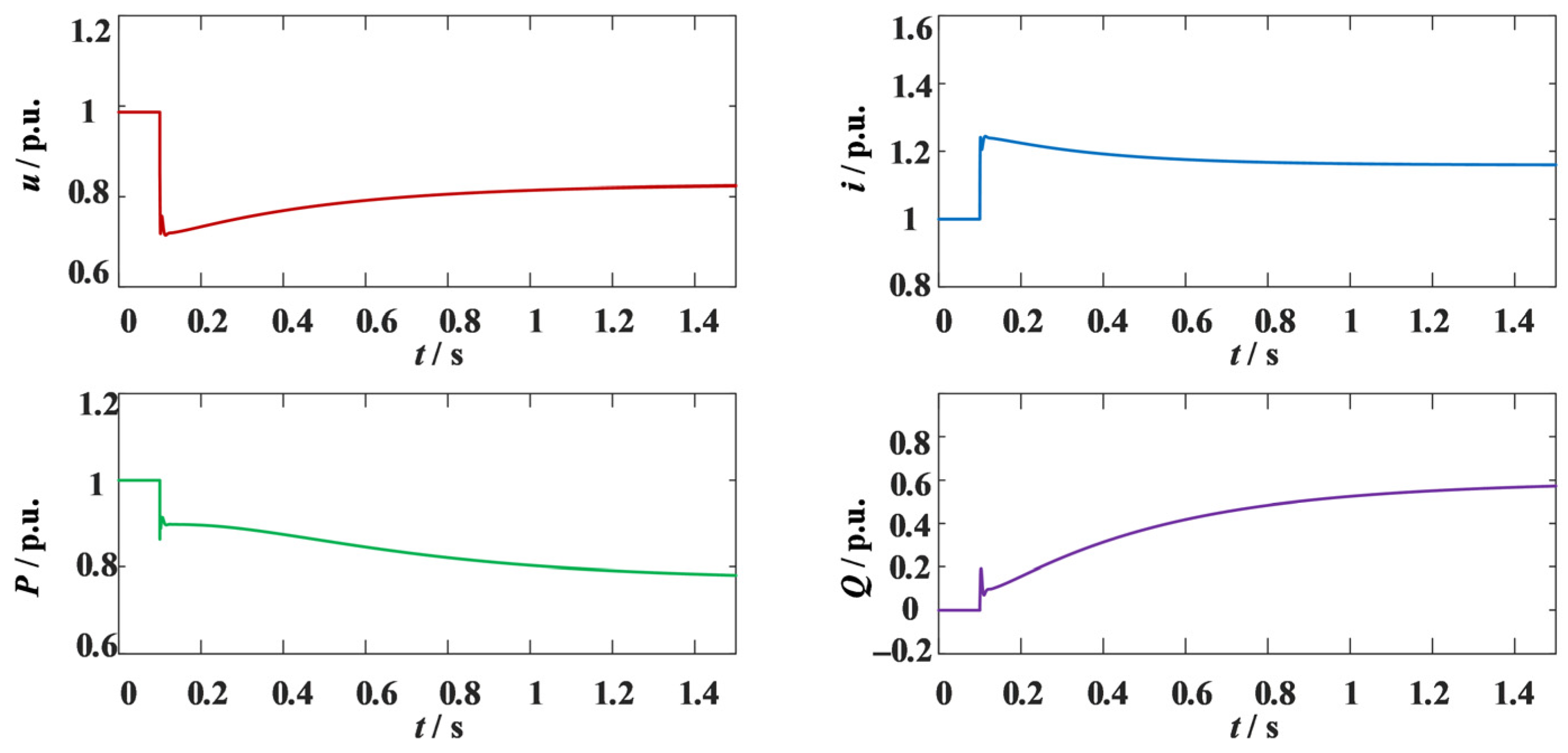

(2) Operating condition 2: moderate voltage drop (voltage drops to 40–70%)

A three-phase short-circuit fault occurs at 35% of line 1 at 0.1 s, with a transition impedance of 1 +

j1 Ω.

Figure 24 shows the voltage, current, and active and reactive power at the grid connection point when the proposed improvement method is not applied. The minimum voltage amplitude drop is 0.6873 p.u. The converter continues to provide reactive power support to increase the voltage, while the active power output continues to decrease and the reactive power continues to increase to raise the terminal voltage. During the fault period, the current amplitude remains above 1.25 p.u. for a long time, posing a serious overcurrent risk to the converter.

When the amplitude of the positive-sequence voltage is detected to be less than 0.9 p.u., it is determined that the system has experienced a fault. The control loop of

Mfi

f is frozen, the fixed value

KG is set to 1.02, and adaptive virtual impedance control is used for overcurrent suppression. At this time, the voltage, current, active power, and reactive power are shown in

Figure 25.

By comparing

Figure 24 and

Figure 25, it can be seen that the improved reactive power support method based on the frozen reactive power–voltage droop link, combined with the adaptive virtual impedance fault overcurrent suppression method, effectively suppresses fault overcurrent while increasing the reactive power output of the grid-connected converter. Taking the time of 1.467 s as an example, the reactive power increases from 1.0 p.u. to 1.142 p.u., an increase of 14.2%. The converter provides more sufficient reactive power support during the fault period while also avoiding fault overcurrent caused by rapid reactive power support. The steady-state current THD is 3.0%, which meets engineering requirements.

Analysis of the current THD control effect:

(1) The LCL filter (L = 0.035 mH, C = 10 μF in

Table 1) can effectively suppress high-frequency harmonics;

(2) The inductive component Xv of the adaptive virtual impedance (e.g., initial value 0.5 p.u.) further suppresses low-order harmonics (e.g., 3rd and 5th);

(3) The frozen droop only adjusts the voltage command amplitude without changing the sinusoidality of the current waveform, so it has no negative impact on THD.

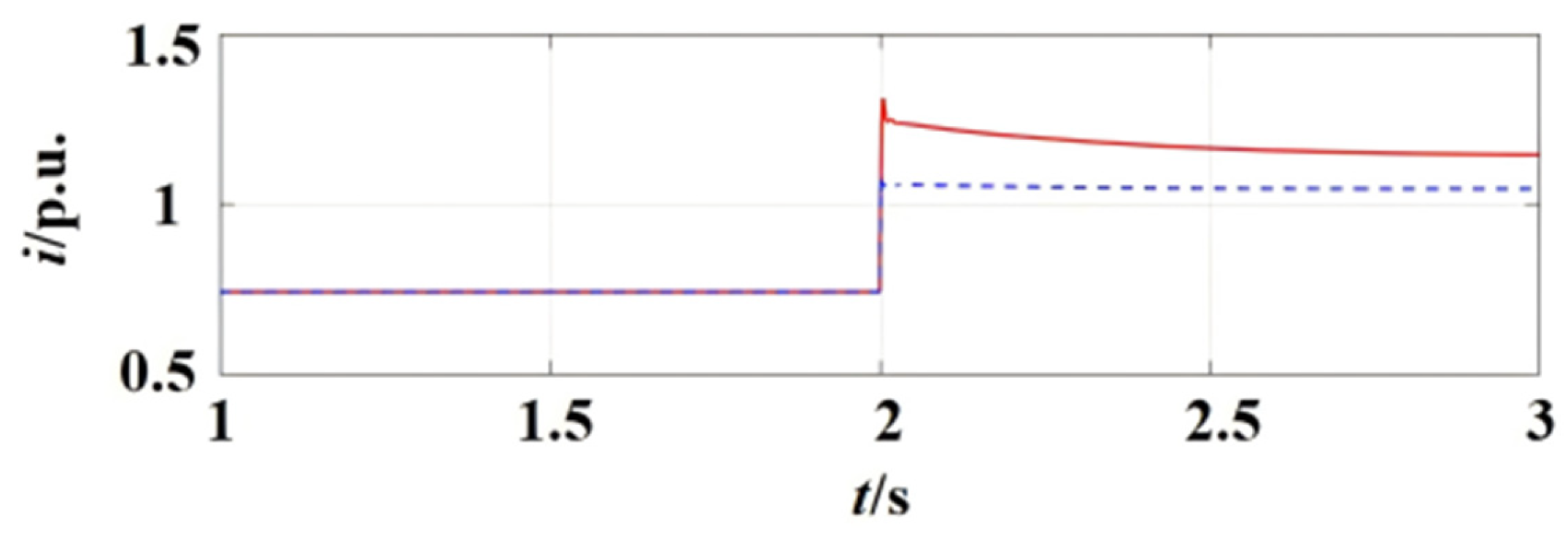

The comparison of reactive power before and after the improvement is shown in

Figure 26. The blue dashed line represents the reactive power output of the converter under the improved method, and the red solid line represents the reactive power output of the converter when the reactive-voltage droop control is not frozen. After freezing the reactive-voltage droop control during a fault, the reactive power output at each time node increases.

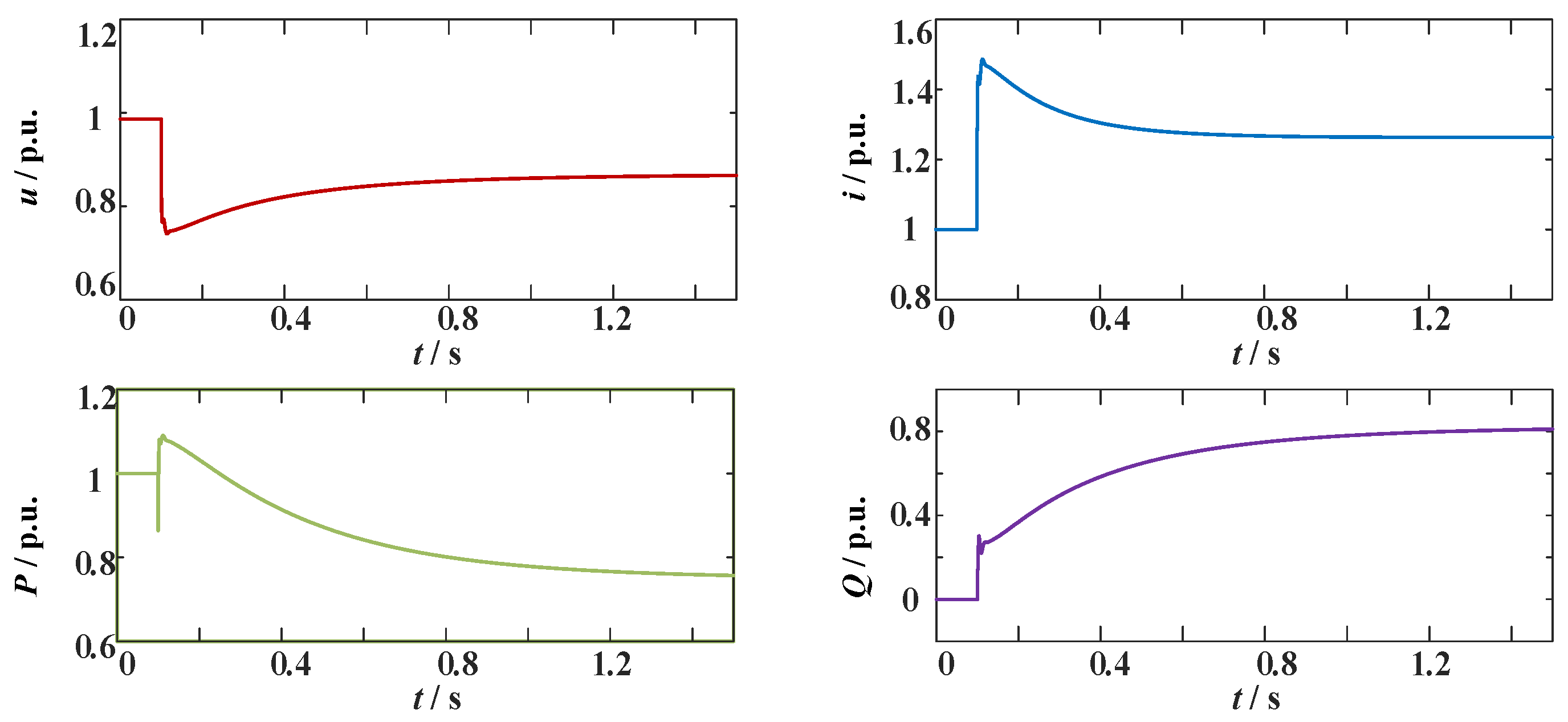

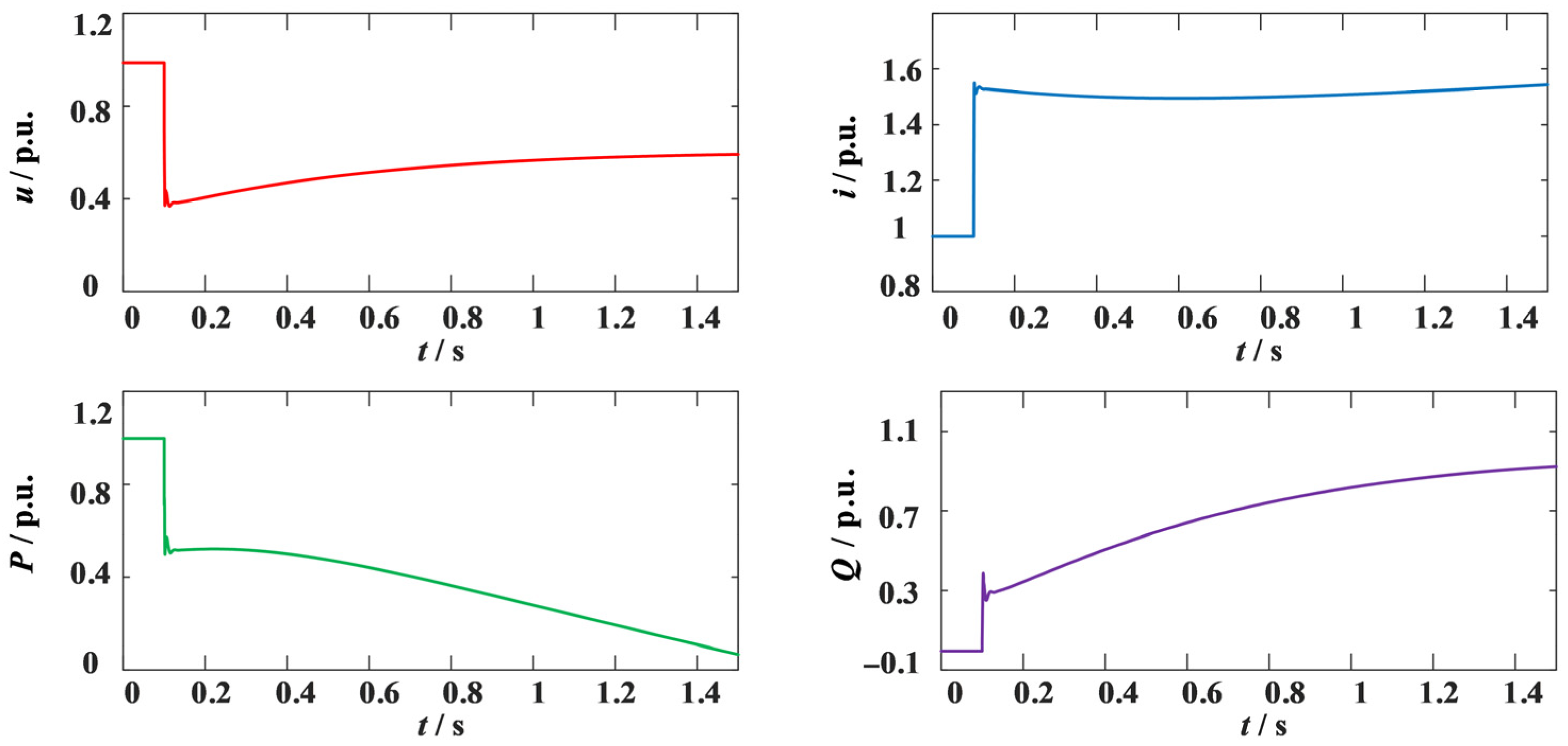

(3) Operating condition 3: severe voltage drop (voltage drops below 40% of rated voltage)

A three-phase short-circuit fault is set to occur at 65% of line 1 at 0.1 s, with a transition resistance set to 1 +

j1 Ω. When the proposed improvement method is not used, the grid-connected voltage, current, and active and reactive power are shown in

Figure 27. The minimum voltage amplitude drop is 0.3687 p.u., and the current amplitude during the fault period is consistently above 1.5 p.u., causing severe overcurrent in the converter and a significant increase in the output reactive power.

At this time, the primary control objective for the converter is to limit the current to prevent the inverter from being burned out, and there is no need to freeze the reactive power loop to increase the reactive power output of the converter. An adaptive virtual impedance control strategy is used to limit the current and remove the fault at 0.3 s. The voltage, current, active power, and reactive power conditions at this time are shown in

Figure 28. The maximum current amplitude is 1.248 p.u. The adaptive virtual impedance control strategy effectively suppresses the fault overcurrent, and the converter provides more reactive power support during the fault. After the fault is removed, the reactive power–voltage droop control link is restored, and the converter returns to normal operation.

Through simulation verification under different voltage sag levels, it can be seen that the reactive power support method based on frozen reactive power–voltage droop control link combined with adaptive virtual impedance fault overcurrent suppression method can effectively function in various fault scenarios, enabling the grid-connected converter to output more reactive power without overcurrent risk.

Existing power grid protection schemes mainly include overcurrent protection, voltage protection, and distance protection. The proposed methods work synergistically with these schemes by suppressing overcurrent and supporting voltage, with the following specific interaction mechanisms:

(4) Interaction with Overcurrent Protection

The traditional converter overcurrent protection threshold is 1.2~1.5 times the rated current:

Minor faults: The adaptive impedance suppresses the current to within 1.05 p.u., avoiding false protection operation;

Severe faults: The current is suppressed to 1.248 p.u., close to the protection threshold, allowing the protection to operate normally according to the set time, with the method not interfering with the protection logic;

Adaptation suggestion: If the protection threshold <1.2 p.u., adjust Ilim to 1.0 p.u. to ensure threshold matching.

(5) Interaction with Overcurrent Protection

The undervoltage protection threshold of the distribution network is 0.85~0.9 p.u.:

When the voltage drops to 0.8~0.9 p.u., the frozen droop control quickly increases reactive power, restoring the voltage to above 0.85 p.u., avoiding protection tripping;

If the method fails and the voltage remains <0.85 p.u., the voltage protection can operate to cut off the fault, forming a “support-backup” mechanism.

(6) Interaction with Distance Protection

Distance protection judges the fault location via line impedance, and the impact of the proposed methods is negligible:

The converter-side impedance increased by the adaptive impedance is much smaller than the line impedance, not causing the protection to misjudge the fault location;

The frozen droop supports the voltage, reducing measurement errors of the protection caused by excessively low voltage.

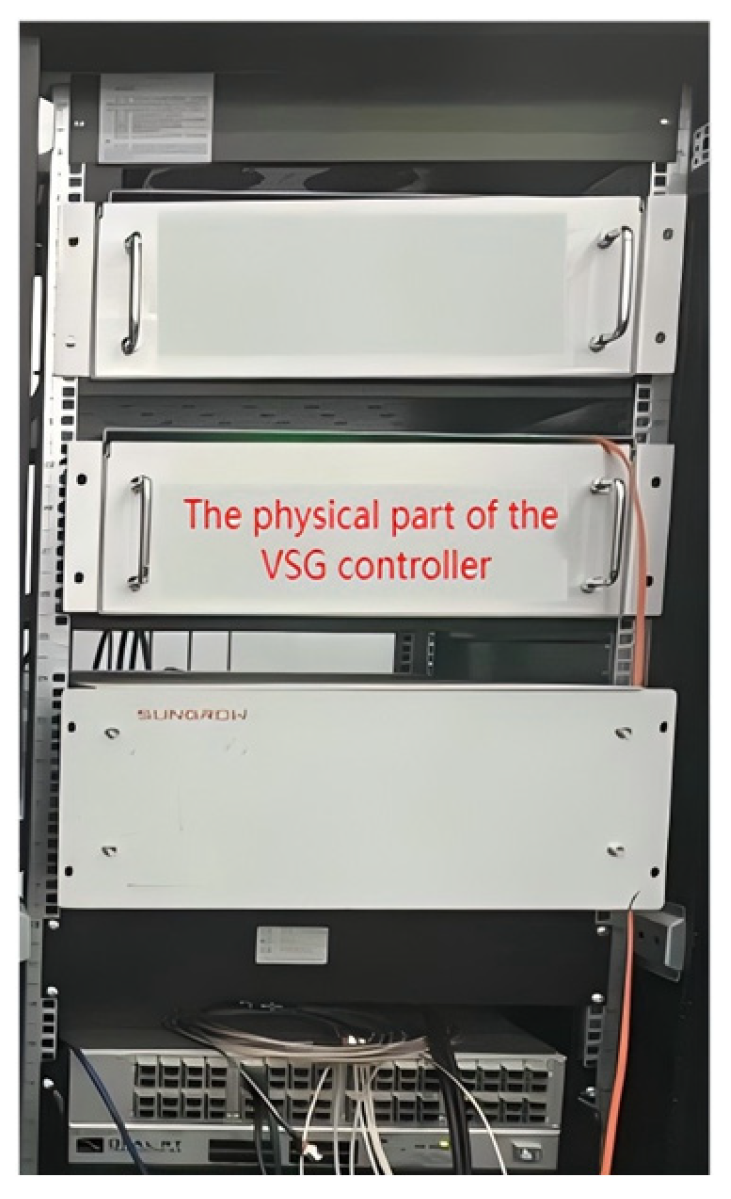

4.4. Low-Voltage Ride-Through Verification Based on Hardware-in-the-Loop Experiments

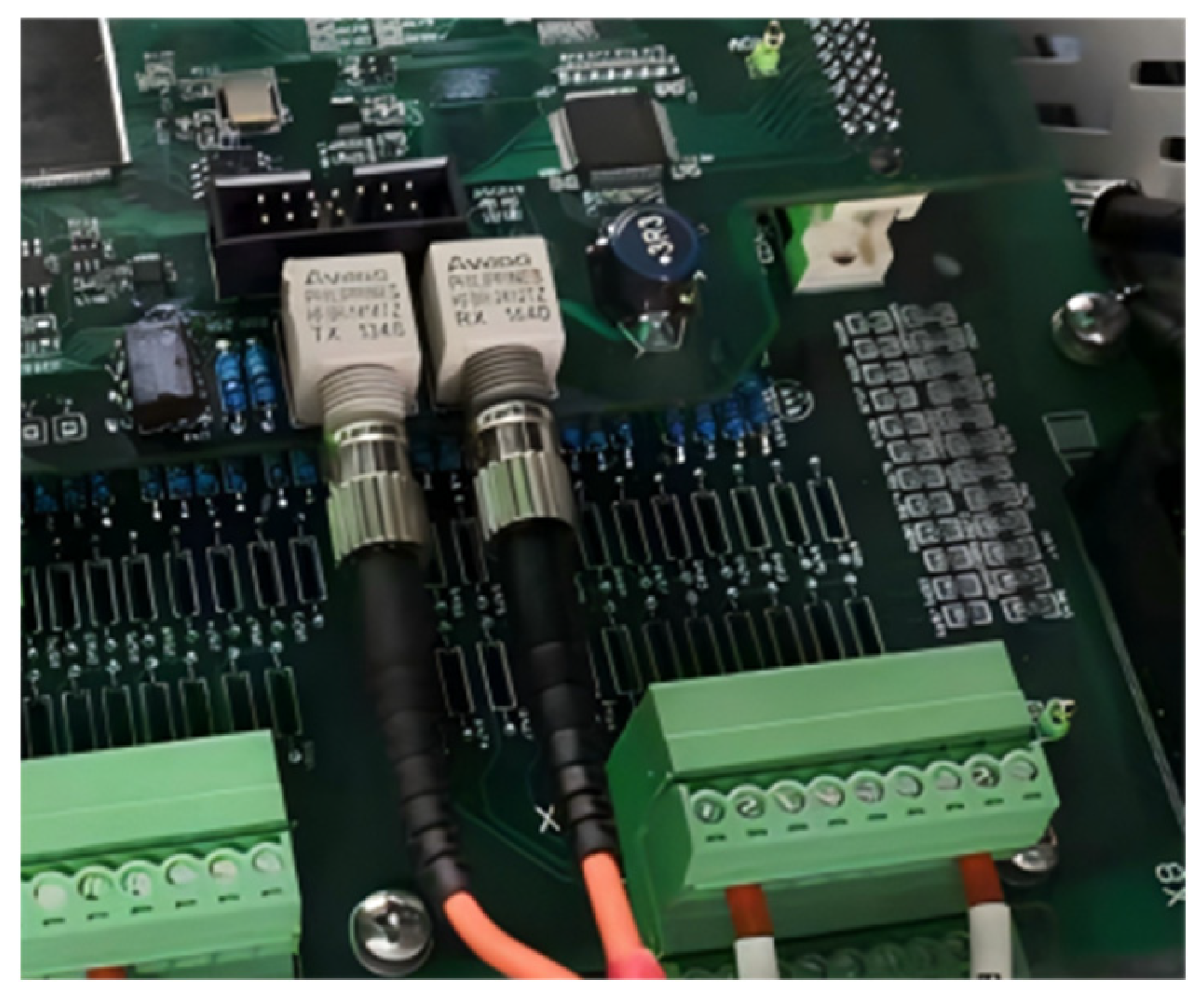

To verify the correctness of the quantitative virtual impedance design method proposed in this paper, a hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) semi-physical simulation experimental platform was established using RT-LAB 2024.1.8 software. The HIL simulation platform mainly consists of a PC, an RT-LAB-based real-time digital simulator, and VSG controller hardware. The physical hardware of the HIL simulation platform and the logical principles of each component are illustrated in

Figure 29. The VSG controller is a physical hardware unit, while other logical components are integrated into the simulation model of the real-time digital simulator.

The main circuit model of the VSG grid-connected system was constructed through simulation on the RT-LAB software platform. The simulation part achieves integration and data sharing with the controller hardware via the real-time digital simulator. After setting the control parameters of the controller hardware, the controller calculates PWM control signals based on the operational data transmitted from RT-LAB and sends these signals to the real-time digital simulator, ultimately realizing complete system control. The controller hardware features a sampling and control cycle of 4 kHz, and the frequency of space vector pulse width modulation (SVPWM) is also 4 kHz. This high sampling and control frequency ensures the real-time performance between the hardware control unit and the virtual simulation model of the main circuit.

The VSG controller hardware transmits data with the Real-Time Digital Simulator (RTDS) via a DB37 connecting cable. It receives real-time data such as current and voltage from the RTDS, calculates the PWM modulating wave signals based on its own control parameters and the operating status of the main circuit, and ultimately completes the real-time simulation of the entire system. The DB37 connecting cable interface and the fiber optic interface on the PC terminal are shown in

Figure 30.

The specific parameters of the hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) experiment are consistent with

Table 1.

Figure 31 illustrates the variation in the fault current when the point of common coupling (PCC) voltage drops to 0.70 p.u. At this juncture, it can be observed from the figure that the current during the fault is constrained, thereby achieving the grid-forming inverter’s low-voltage ride-through capability under symmetrical faults.

Figure 32 illustrates the reactive power variation under this condition. With the proposed low-voltage ride-through (LVRT) control strategy, the power output during the fault period can reach the set value within an extremely short time.

Table 6 presents the peak fault currents of the VSG under hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) experiments with different voltage sag depths. It can be concluded from the experimental results that with the proposed low-voltage ride-through (LVRT) control strategy, all peak currents can be effectively limited, which verifies the correctness of the proposed control strategy.

We designed a comparison table of the deviations of core indicators between the simulation and HIL experiments under the same fault scenario (PCC voltage 0.7 p.u.). As shown in

Table 7.

(1) Summary of deviation causes: The simulation model ignores hardware delays and sampling noise, leading to slightly worse HIL results than the simulation.

(2) Model correction plan: Add a “hardware delay module” and a “Gaussian noise module” in subsequent simulations to reduce the deviation rate between the simulation and HIL to within 3%.

(3) Engineering implications: Hardware calibration is required in practical deployment to reduce noise impact, and PWM dead time should be optimized to improve reactive support capability.