Fast Risk Assessment for Receiving-End Power Grids with High Penetration of Renewable Energy Based on the Fault Transient Evolution Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

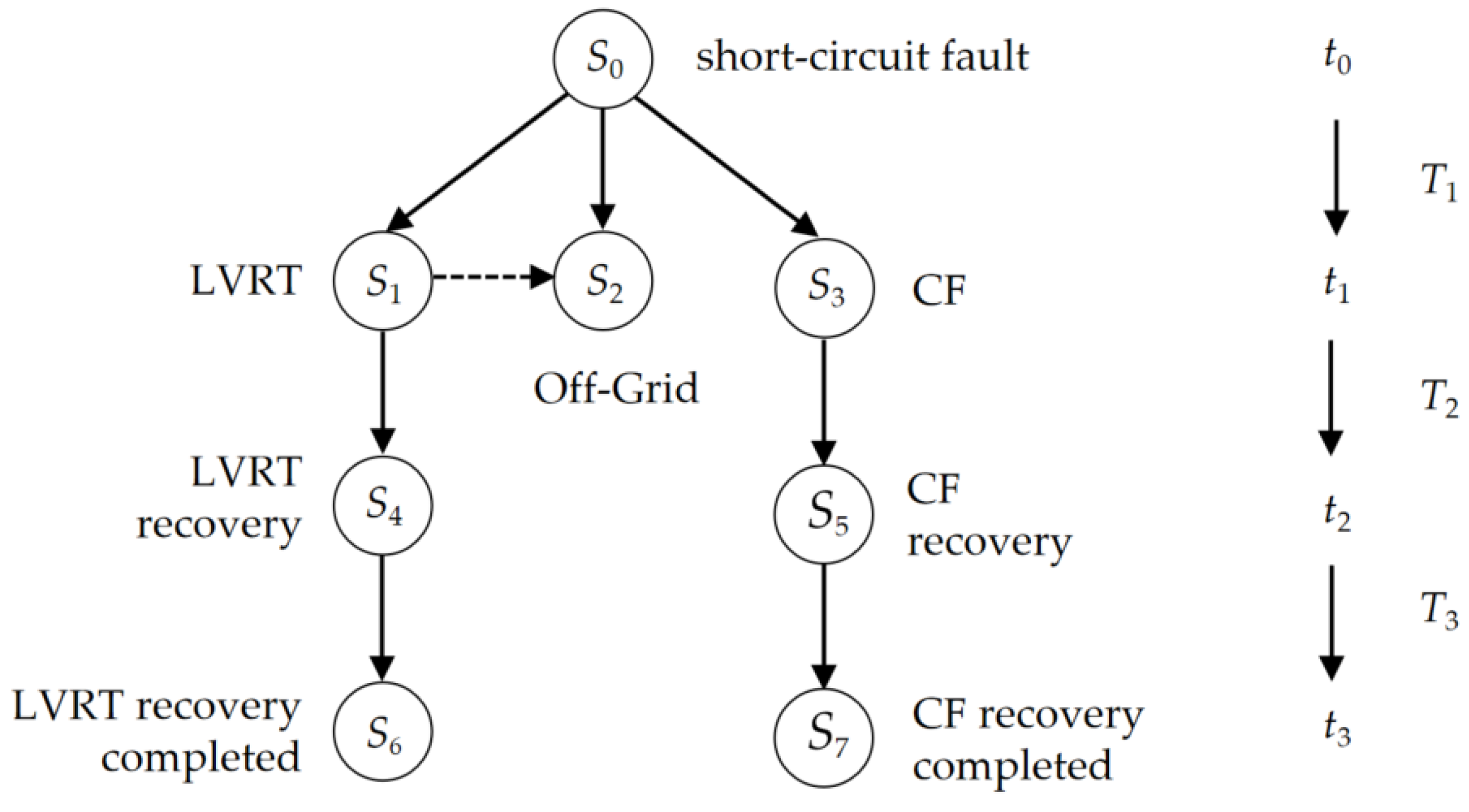

- This paper constructs a directed weighted graph to describe the transient evolution process following a short-circuit fault. By thoroughly analyzing the state transition logic of renewable energy LVRT, renewable energy tripping, and DC CF, we define key temporal parameters to quantify the duration of different states.

- This paper also constructs state transition models and temporal feature models that map the initial short-circuit fault to the transient response of renewable energy and DC equipment. Leveraging these models, we successfully generate complete fault evolution scenarios.

- Based on the fault event state transitions logic and key temporal parameters, this paper proposes a phased simplified calculation method for equivalent active power loss. This methodology achieves rapid risk assessment during the fault transient evolution process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analysis of the Fault Transient Evolution Processes

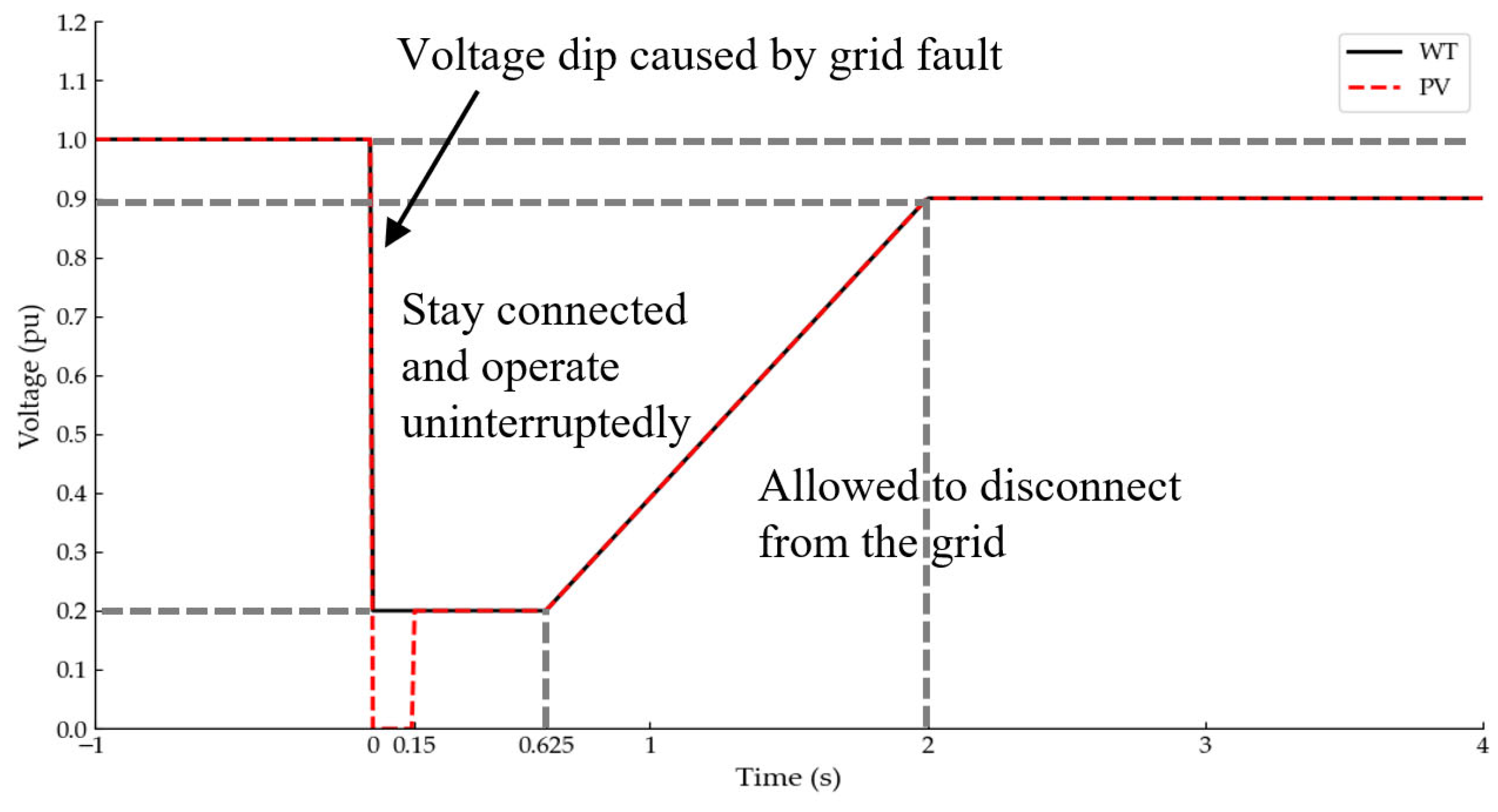

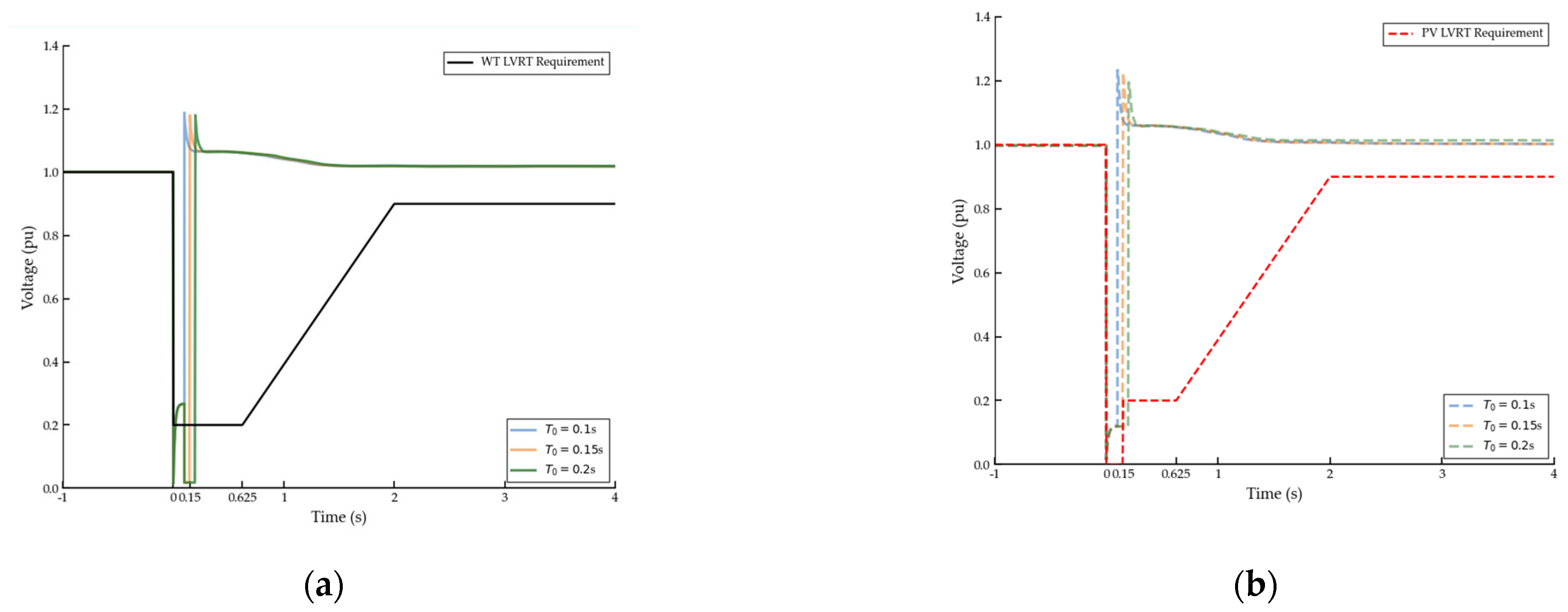

2.1.1. Renewable Energy LVRT

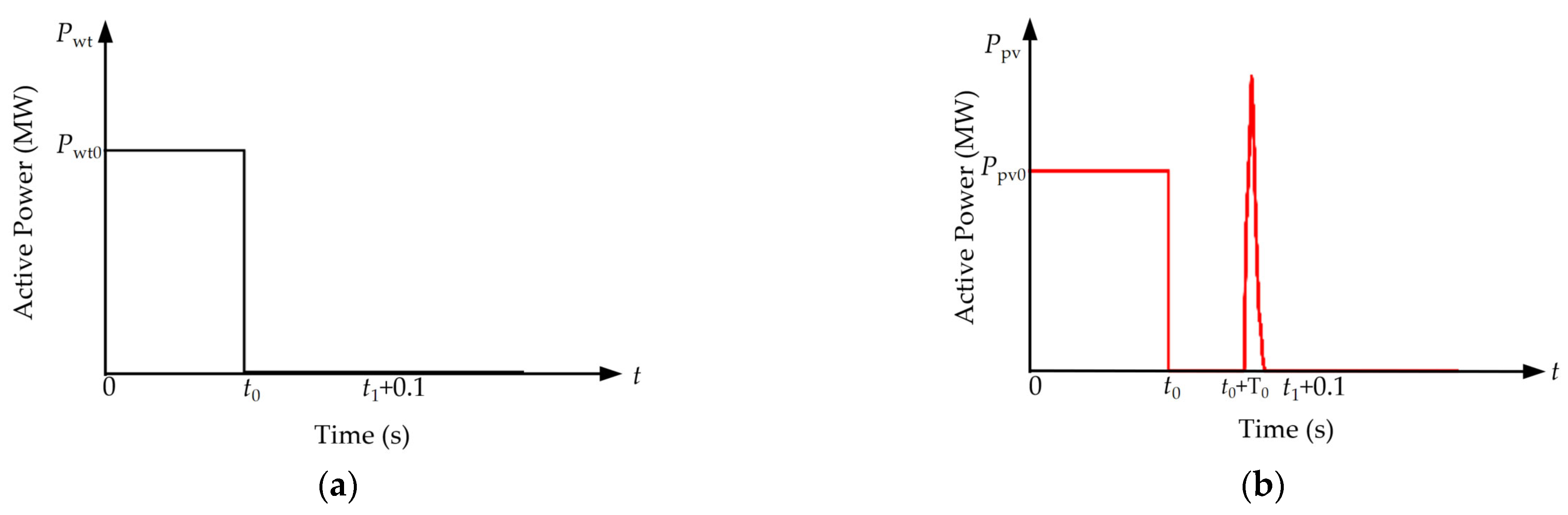

2.1.2. Renewable Energy Tripping

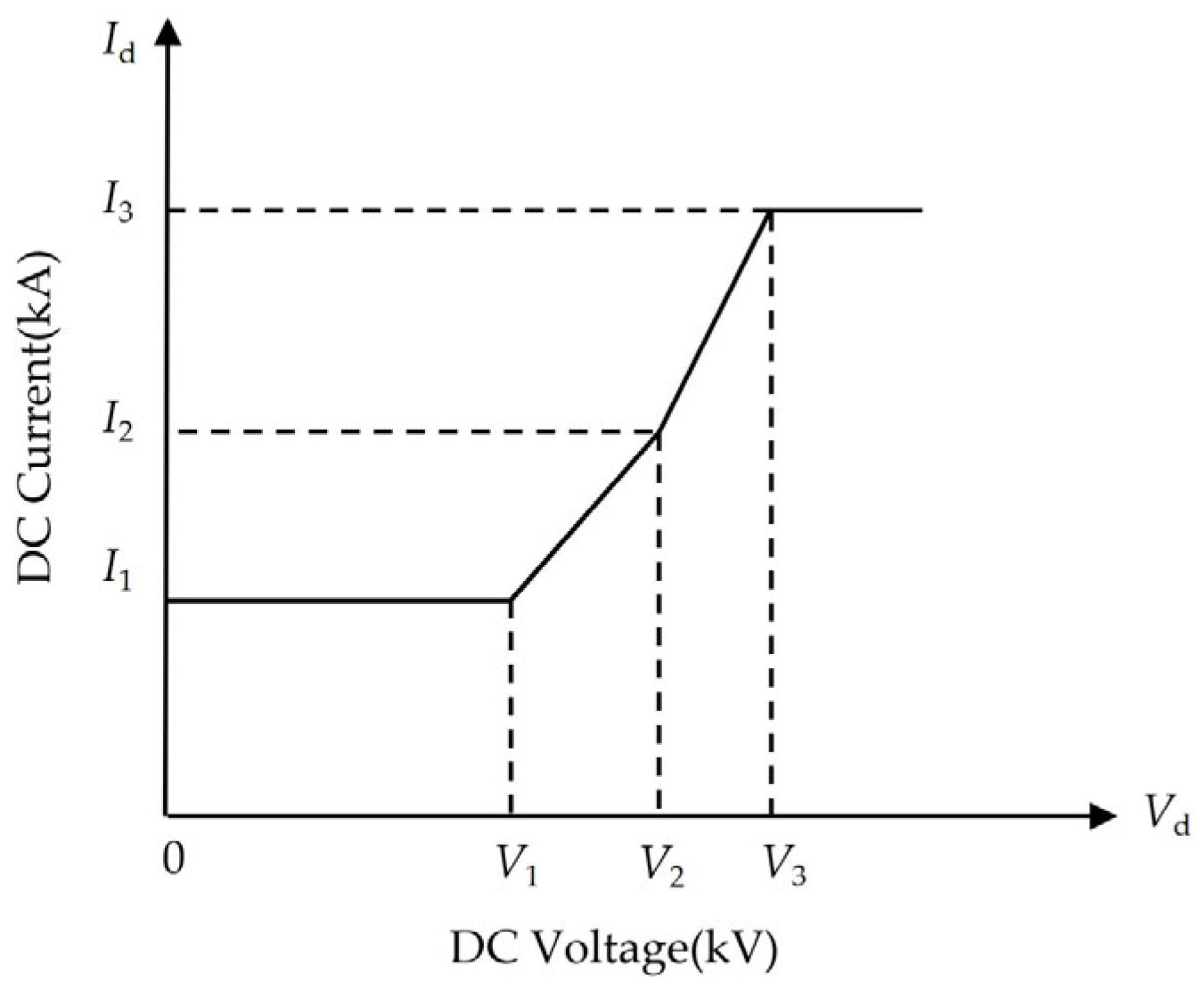

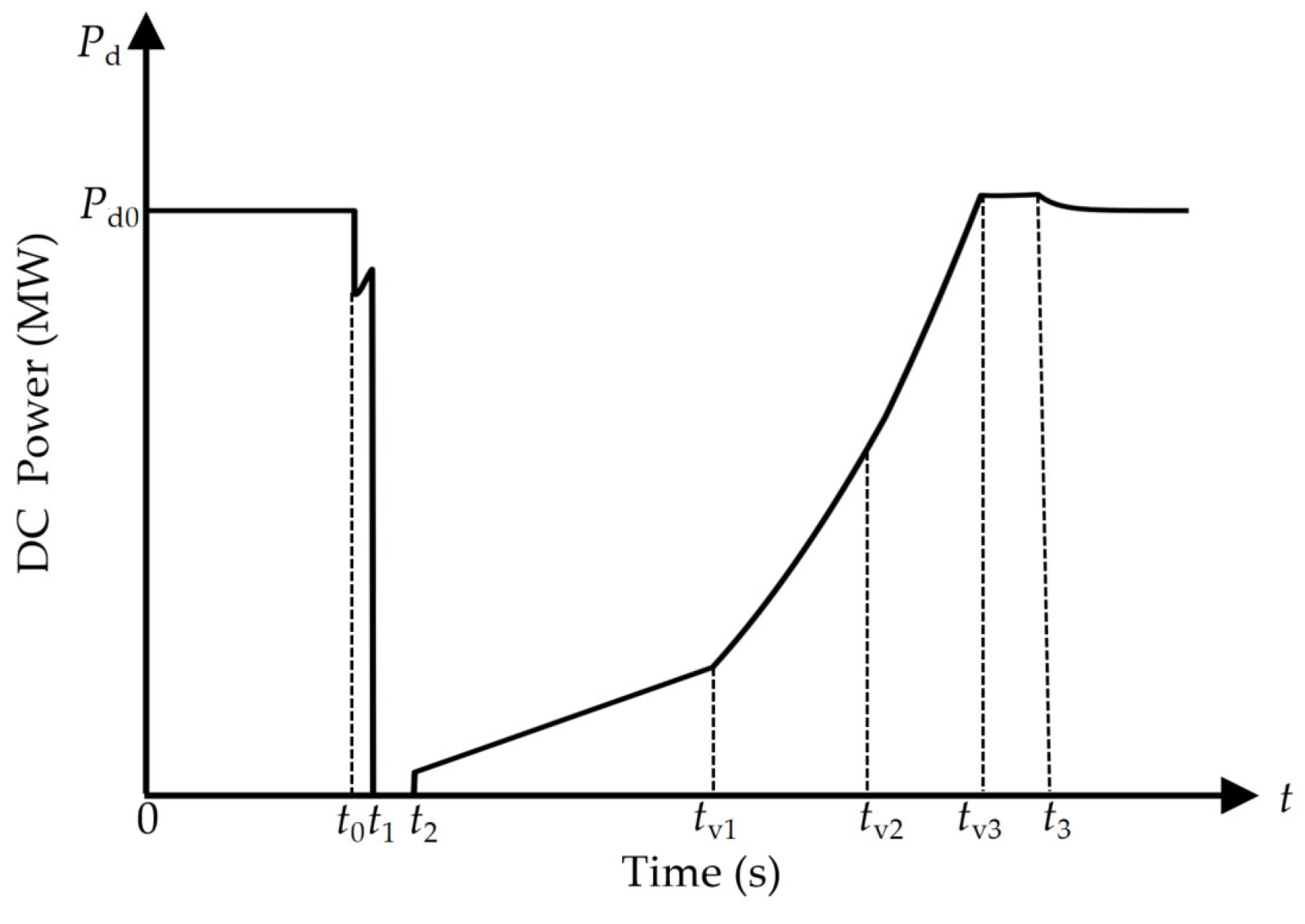

2.1.3. DC Commutation Failure

2.1.4. Fault Transient Evolution Process

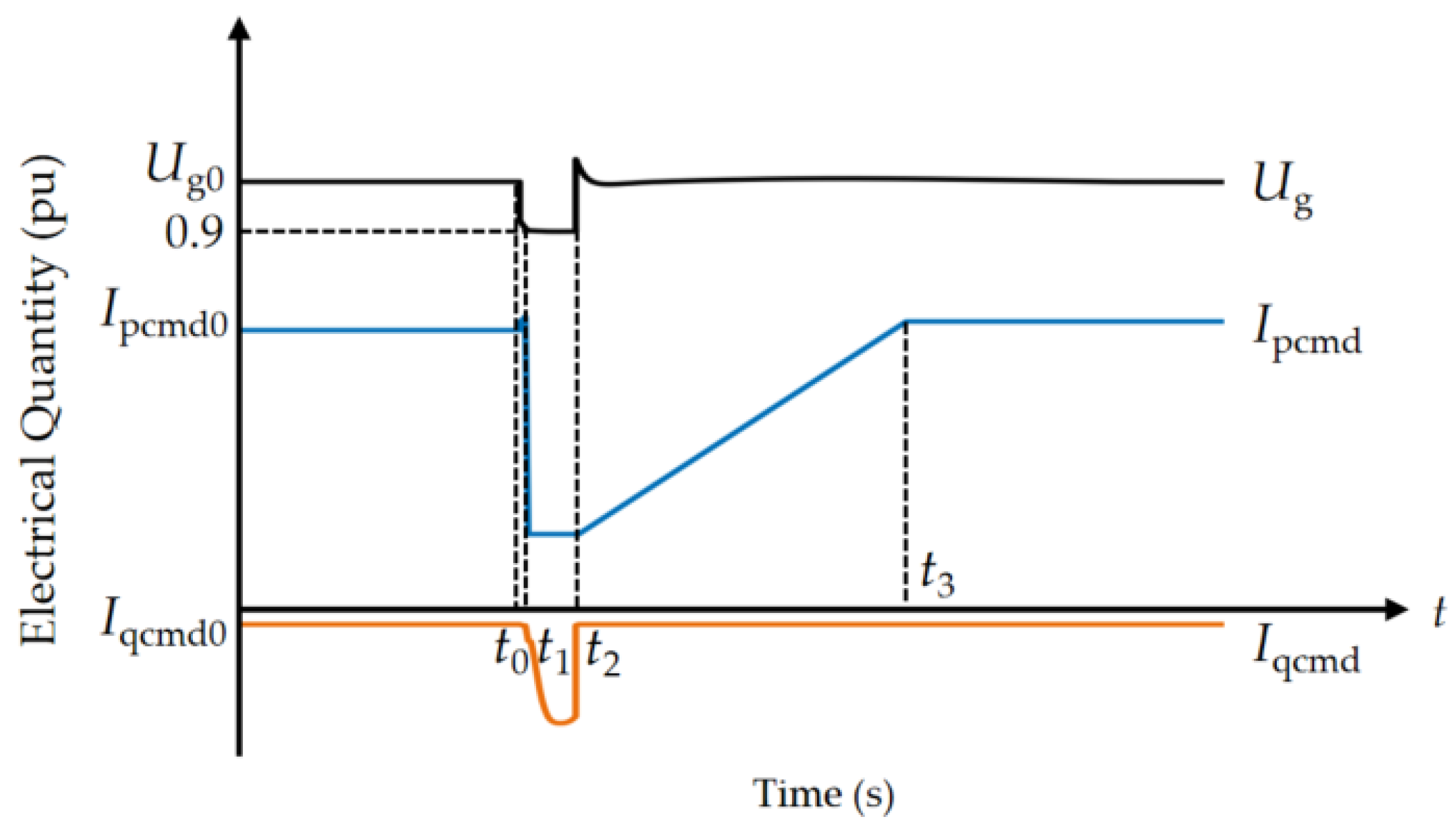

- t0: The moment the initial short-circuit fault occurs.

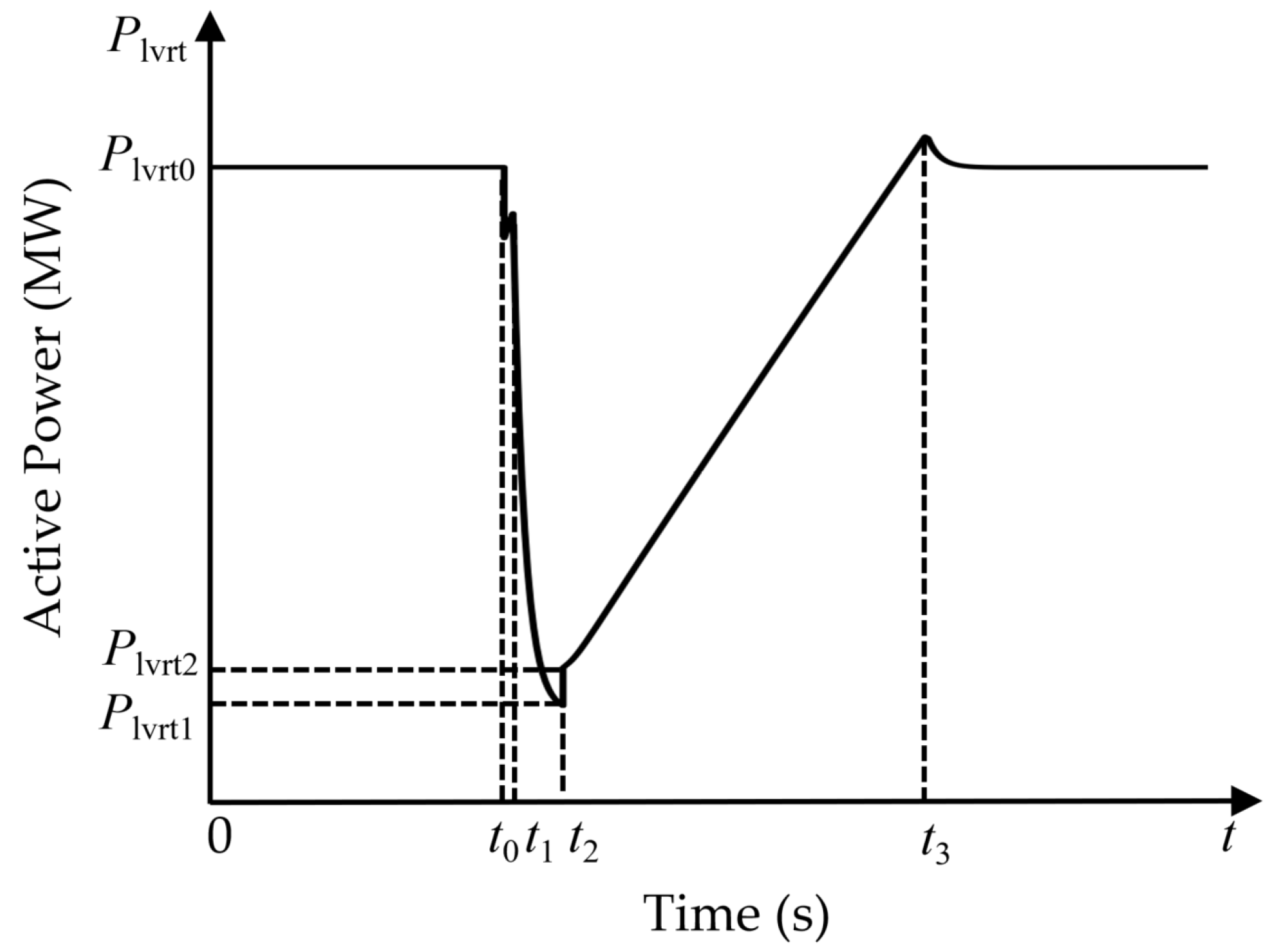

- t1: The starting moment the equipment switches from the normal operation state to the fault operation state, such as the moment the renewable energy unit enters the LVRT state (shown in Figure 2), the instant the renewable energy PCC voltage exceeds the limit (shown in Figure 3), and the moment DC commutation failure occurs (shown in Figure 5).

- t2: The starting moment the equipment switches from the fault operation state to the fault recovery state.

- t3: The moment the equipment switches from the fault recovery state back to the normal operation state.

2.2. Fault Evolution Scenario Generation Based on State Transition and Temporal Features Models

2.2.1. Sample Set Construction

- (1)

- Determination of Output Labels

- (2)

- Selection of Input Features

2.2.2. Construction of State Transition and Temporal Feature Models

- (1)

- XGBoost Algorithm

- (2)

- Model Training

- (3)

- Model Evaluation Metrics

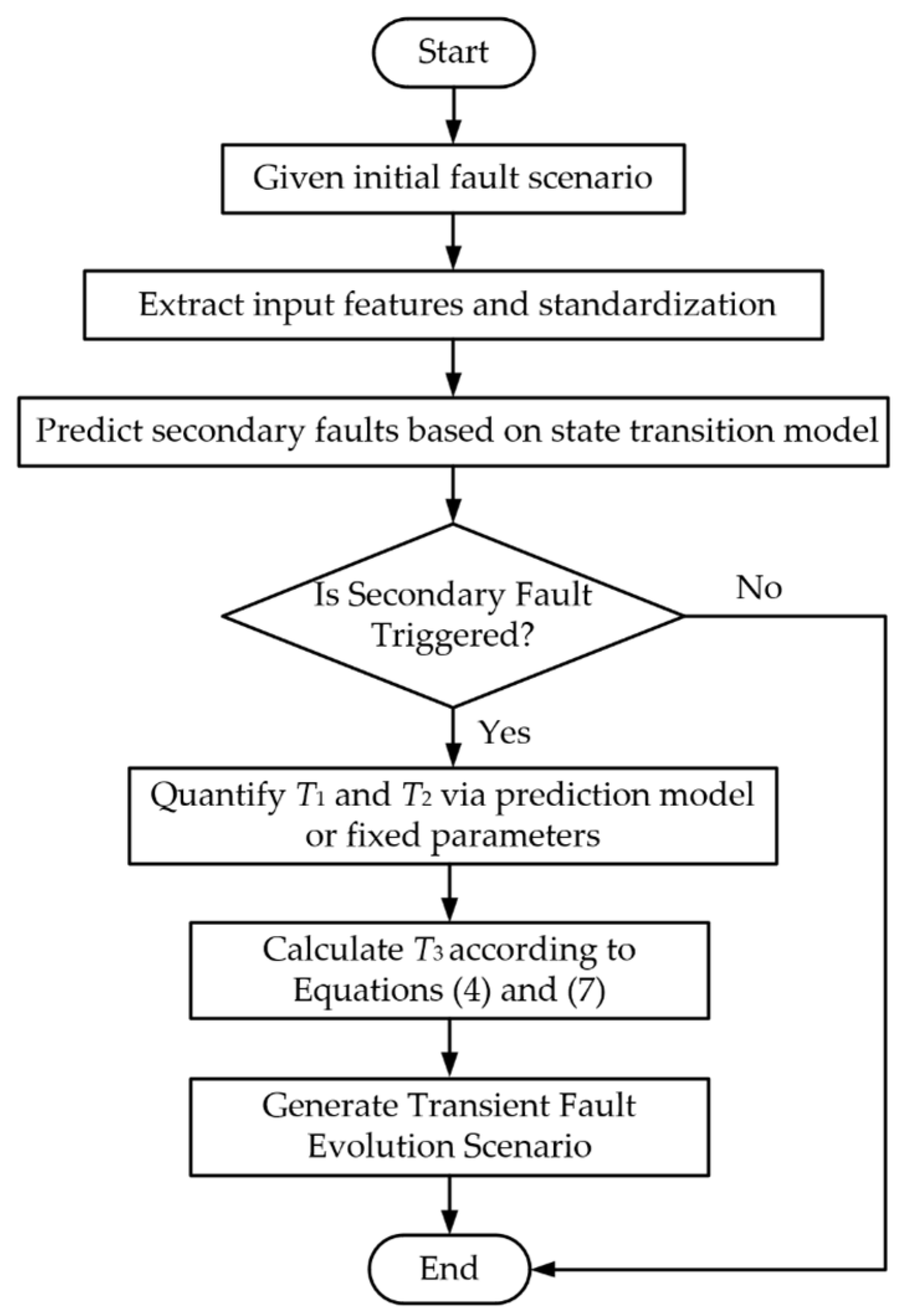

2.2.3. Fault Evolution Scenario Generation

- Predict secondary faults: Input the features into the state transition model. For renewable energy equipment, first predict whether a tripping event occurs. If tripping occurs, the subsequent judgment is terminated. If tripping does not occur, further prediction is made as to whether LVRT occurs. For DC equipment, the prediction of whether CF occurs is performed in parallel.

- Quantify temporal feature parameters: For WT and PV predicted to trip, T1 is set to 0 and 0.15 s, respectively. For renewable energy units judged to undergo LVRT, T1 and T2 are predicted based on the temporal feature model. For DC equipment, where CF is predicted, T1 is predicted, and T2 is set to the fault duration value of 0.2 s. T3 is calculated according to Equations (4) and (7) by using the equipment’s control parameters in all cases.

- Generate fault transient evolution scenario: Integrate the initial fault information, the sequence of subsequent fault states for each equipment, and the temporal feature parameters. Then, obtain the fault evolution path for each renewable energy unit and DC device, ultimately generating the complete fault evolution scenario.

2.3. Risk Assessment of the Fault Transient Evolution Process

2.3.1. Renewable Energy LVRT Risk

- Stage 1 (t0 to t1): Under severe transient disturbance, the voltage of most renewable energy units drops below the LVRT threshold of 0.9 pu. immediately upon fault occurrence, meaning T1 tends to be zero. Additionally, some renewable energy units may initiate LVRT due to voltage drop during the fault duration, where T1 is relatively short. Furthermore, under the effect of electrical control, the reduction in active power is minor, so the risk value for this stage is approximated as zero:

- 2.

- Stage 2 (t1 to tcl): In this stage, the active current is restricted to a lower level, and the active power rapidly decreases to a minimum value, Plvrt1. The recovery initiation moment t2 depends on the depth of the voltage drop: if the drop is deep, t2 equals the fault clearance moment tcl; if the drop is mild, the station may recover in advance using its own reactive power support capability, so t2 < tcl. Theoretically, t2 is the end moment of LVRT, but in the case where t2 < tcl, the voltage maintains at approximately 0.9 pu during the period t2 to tcl; thus, the power is considered to remain stable at Plvrt1. Therefore, to simplify the calculation, the upper limit of integration is taken as tcl, and the equivalent power loss for this stage is as follows:where α is a coefficient, when t2 = tcl, α is 1; when t2 < tcl, α is 0.5, indicating a slow decrease in active power to Plvrt1. The value of Plvrt1 depends on whether T1 = 0: when T1 = 0, Plvrt1 ≈ 0; when T1 ≠ 0, Plvrt1 ≈ 0.9 kp1Plvrt0.

- 3.

- Stage 3 (tcl to t3): In this stage, the renewable energy unit enters the recovery state. After the fault is cleared, the voltage maintains at approximately 1.0 pu, and the active current gradually recovers from the endpoint of the LVRT process at a certain slope. Therefore, the equivalent power loss for this stage is as follows:where Plvrt2 is the active power at the instant of fault clearance, with a value of kp1Plvrt0; and = t3 − tcl.

2.3.2. Renewable Energy Tripping Risk

2.3.3. DC Commutation Failure Risk

- Stage 1 (t0 to t1): The duration of the transient process T1 in this stage is short, and under the control of the DC, the reduction in active power is minor. Therefore, the risk value for this stage is assumed to be zero:

- 2.

- Stage 2 (t1 to t2): During the commutation failure, the active power rapidly drops and remains at zero. The risk for this stage is as follows:

- 3.

- Stage 3 (t2 to t3): In this stage, the DC enters the recovery state. During the t2 to tv3 phase, the active power gradually recovers from zero. This recovery can be calculated using the analytical expressions in Equations (6) and (7), based on the VDCOL curve and the recovery control strategy. In the tv3 to t3 phase, the DC power basically recovers to its initial steady-state value, and the system operates in constant power mode, so the power loss is approximated as zero. Therefore, the equivalent power loss for this stage is as follows:

3. Results

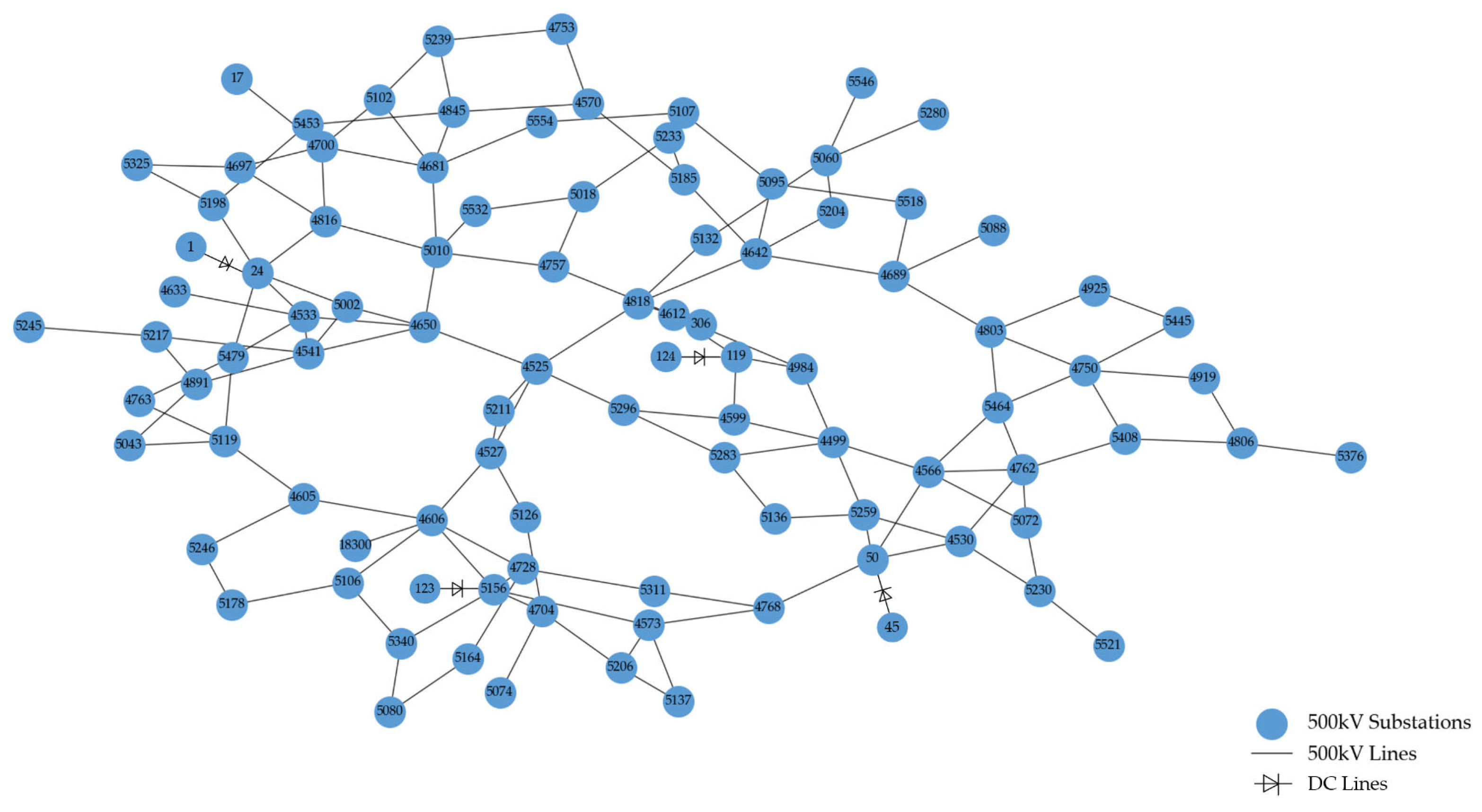

3.1. Simulation Case

3.2. Performance Assessment of State Transition and Temporal Feature Models

3.2.1. Performance Metrics of State Transition and Temporal Feature Models

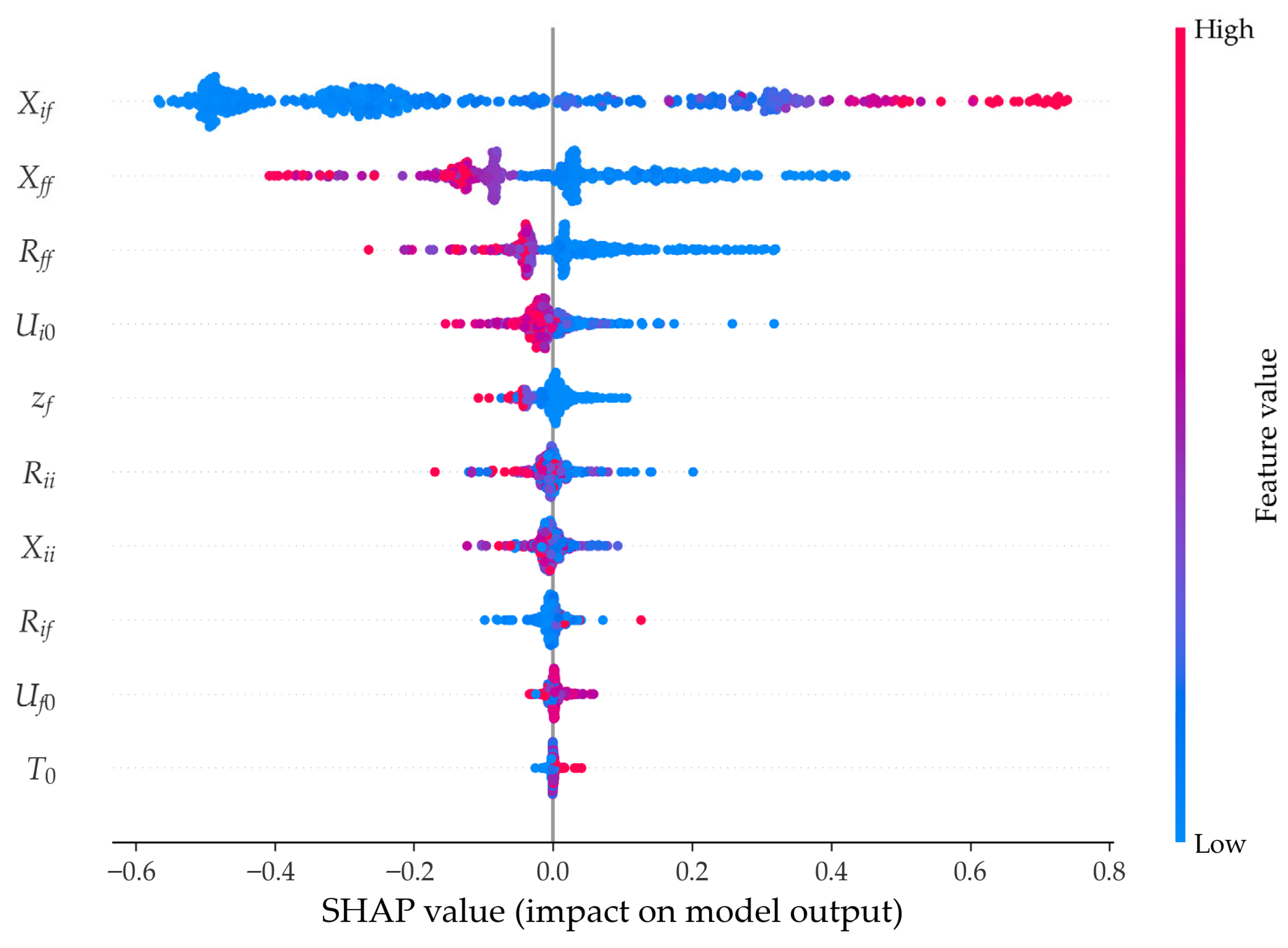

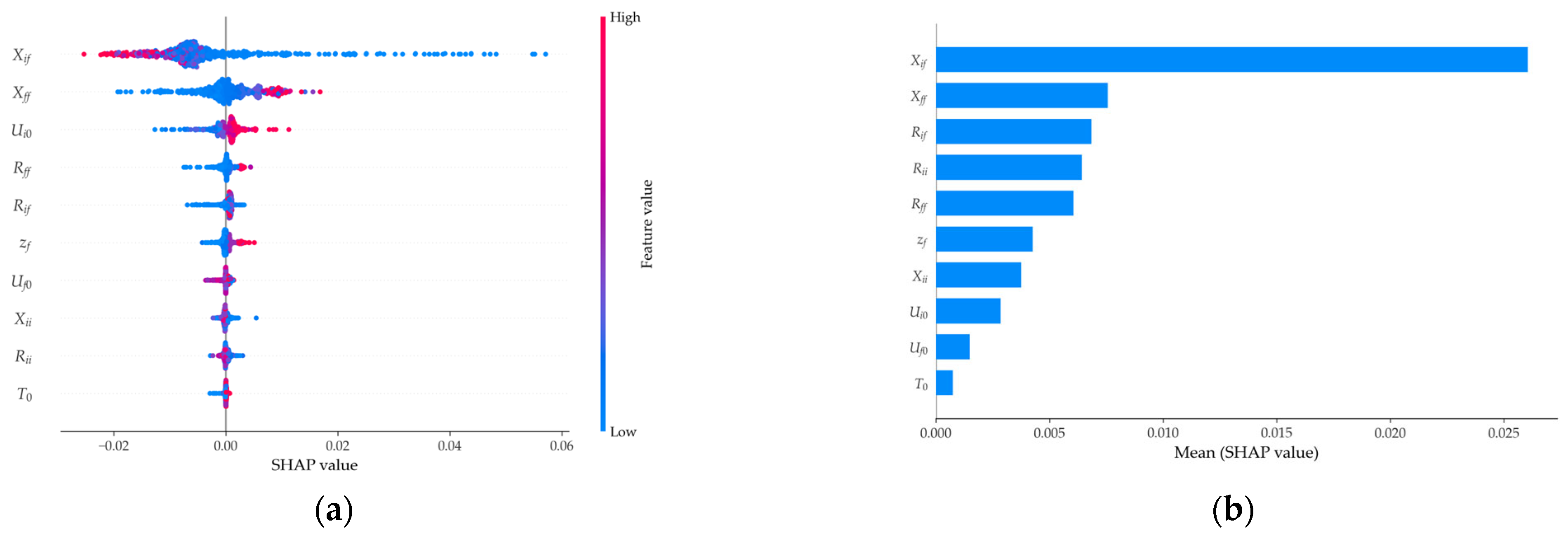

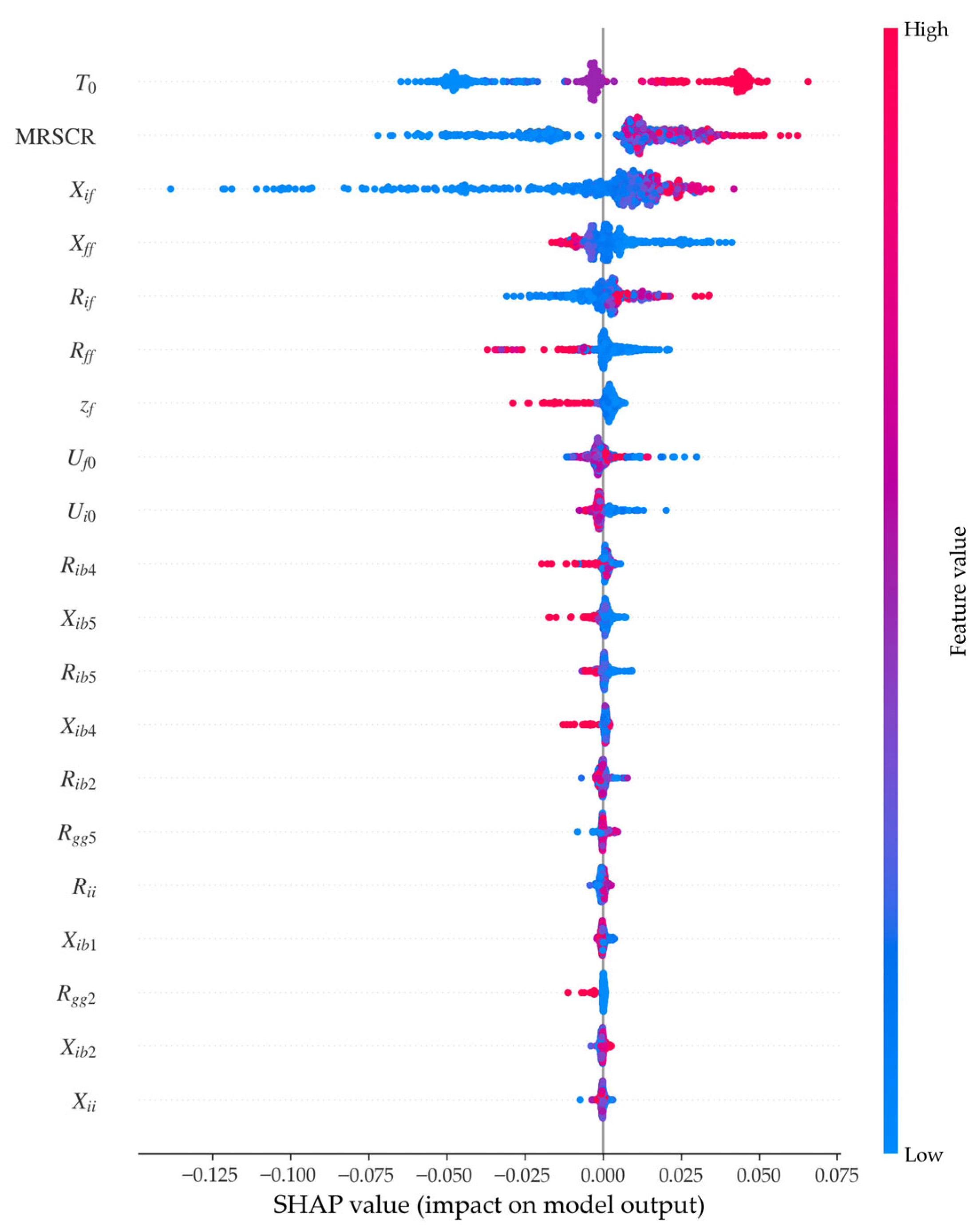

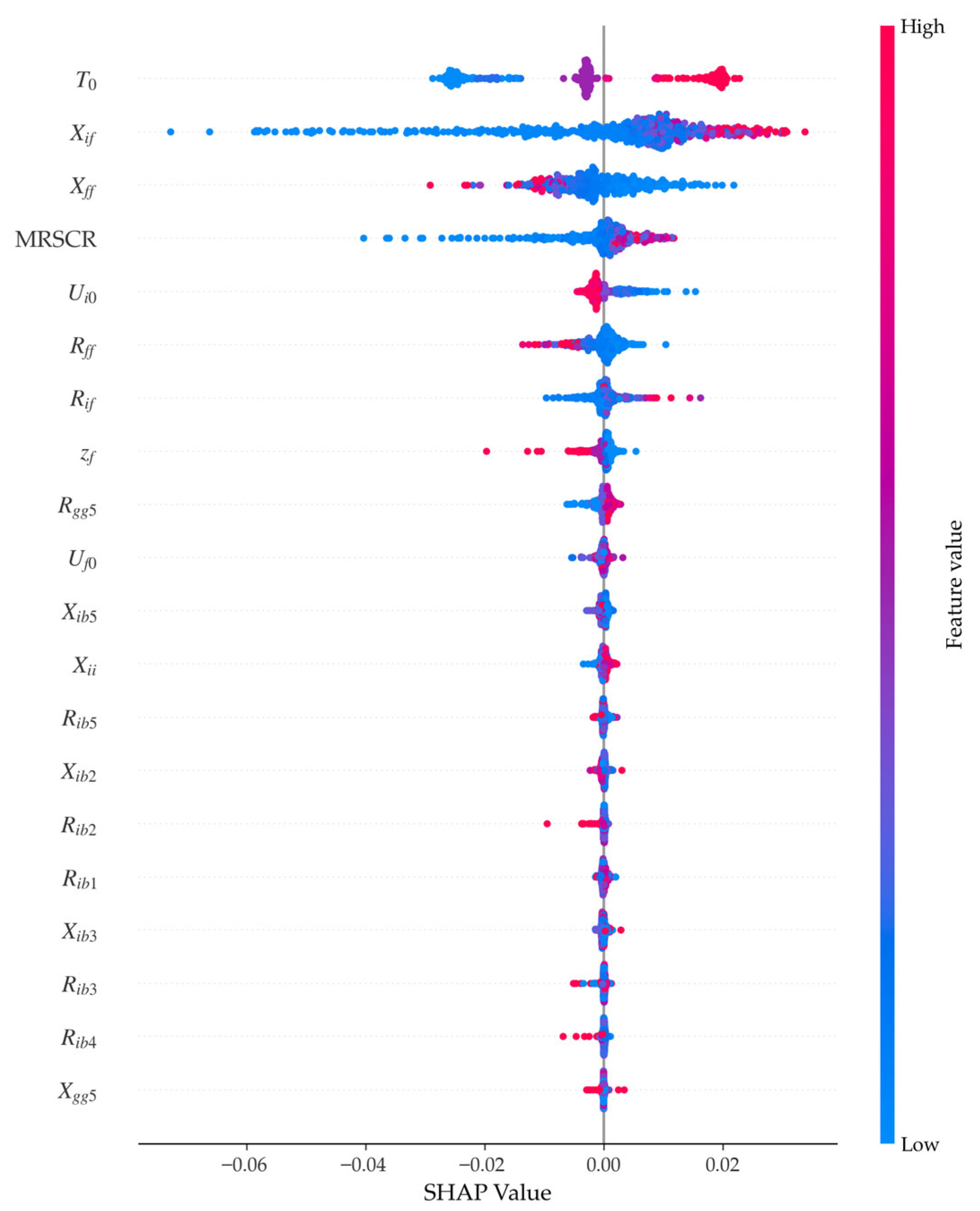

3.2.2. Model Interpretation Based on SHAP

3.2.3. Results of Risk Assessment for the Transient Evolution Process

3.2.4. Fast Risk Assessment Results Based on Fault Evolution Path

- (1)

- Initial fault 1: the fault line is a 500 kV line (5132, 4818), the fault duration is 0.11 s, and the fault grounding impedance is 0.005 pu.

- (2)

- Initial fault 2: the fault line is a 220 kV line (5418, 18,330), the fault duration is 0.14 s, and the fault grounding impedance is 5.6 × 10−5 pu.

4. Conclusions

- Validation using a provincial grid case study demonstrates that the proposed fault transient evolution path prediction method, based on state transition and temporal feature models, not only effectively identifies critical events like renewable energy LVRT but also quantifies key temporal parameters, thereby yielding the complete transient evolution scenario following the fault.

- The proposed phased simplified calculation of the equivalent power loss method can rapidly and effectively quantify the risk associated with complex transient evolution processes, holding significant importance for supporting quick decision making and developing emergency control strategies.

- Feature importance analysis indicates that the triggering of subsequent faults is primarily influenced by mutual impedance. The duration of LVRT is no longer solely determined by fault severity but is largely affected by system strength, fault duration, and the supporting capability of critical nodes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model | Max Depth | Learning Rate | α * | λ * | Subsample * | Colsample * _Bytree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State transition model-LVRT * | 6 | 0.102 | 0.976 | 0.779 | 0.915 | 0.763 |

| Temporal feature model-LVRT T1 | 5 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Temporal feature model-WF LVRT T2 | 4 | 0.171 | 0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Temporal feature model-PV LVRT T2 | 6 | 0.1 | 0 | 1.0 | 0.848 | 0.7 |

| Temporal feature model-CF T1 | 3 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Renewable Energy Station | Plvrt0 (MW) | Prediction T1 (s) | Simulation T1 (s) | Prediction T2 (s) | Simulation T2 (s) | T3 (s) | Rlvrt (MW) | Rlvrt,sim (MW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WF 18315 | 87.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.085 | 0.11 | 1.055 | 3.185 | 3.211 |

| WF 18316 | 87.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 1.585 | 6.643 | 7.024 |

| WF 18321 | 87.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.705 | 2.279 | 2.287 |

| WF 18322 | 87.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.99 | 3.452 | 3.547 |

| WF 21131 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 1.06 | 4.931 | 4.732 |

| WF 21154 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 1.24 | 4.049 | 4.192 |

| WF 21206 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 0.075 | 0.11 | 0.705 | 2.150 | 0.003 |

| WF 21208 | 87.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 1.39 | 5.241 | 5.472 |

| WF 21209 | 87.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.075 | 0.11 | 1.05 | 3.146 | 3.062 |

| WF 21210 | 87.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 1.22 | 4.126 | 4.255 |

| WF 21211 | 87.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.075 | 0.11 | 0.705 | 2.240 | 2.199 |

| WF 21240 | 105 | 0 | 0 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.825 | 4.187 | 3.725 |

| WF 21241 | 87.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.085 | 0.11 | 1.415 | 5.346 | 5.522 |

| WF 21242 | 87.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 1.055 | 3.172 | 3.085 |

| WF 21243 | 87.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 1.405 | 5.329 | 5.576 |

| WF 21244 | 87.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.095 | 0.11 | 0.845 | 2.660 | 2.637 |

| PV 21044 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 0.105 | 0.11 | 0.94 | 3.604 | 3.761 |

| PV 21045 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 0.100 | 0.11 | 1.055 | 3.095 | 3.082 |

| PV 21046 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 0.090 | 0.11 | 0.885 | 2.278 | 2.201 |

| PV 21068 | 126 | 0 | 0 | 0.100 | 0.11 | 1.41 | 7.749 | 8.049 |

| PV 21069 | 70 | 0 | 0 | 0.105 | 0.11 | 0.89 | 1.934 | 1.825 |

| PV 21096 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 0.090 | 0.11 | 0.99 | 3.314 | 3.44 |

| PV 21100 | 33.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.100 | 0.11 | 0.585 | 0.861 | 0.918 |

| PV 21101 | 126 | 0 | 0 | 0.100 | 0.11 | 1.575 | 9.567 | 10.064 |

| PV 21106 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 0.095 | 0.11 | 1.235 | 4.049 | 4.172 |

| PV 21111 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 0.095 | 0.11 | 0.705 | 2.201 | 2.234 |

| PV 21114 | 100.8 | 0 | 0 | 0.105 | 0.11 | 0.88 | 2.759 | 2.63 |

| PV 21123 | 100.8 | 0 | 0 | 0.100 | 0.11 | 1.23 | 4.859 | 4.986 |

| PV 21136 | 126 | 0 | 0 | 0.095 | 0.11 | 0.585 | 2.488 | 2.453 |

| PV 21137 | 126 | 0 | 0 | 0.095 | 0.11 | 0.935 | 5.330 | 5.641 |

| PV 21145 | 105 | 0 | 0 | 0.100 | 0.11 | 1.045 | 3.838 | 3.869 |

| PV 21150 | 105 | 0 | 0 | 0.110 | 0.11 | 1.24 | 5.712 | 5.219 |

| PV 21153 | 70 | 0 | 0 | 0.090 | 0.11 | 0.88 | 1.890 | 1.843 |

| PV 21160 | 168 | 0 | 0 | 0.105 | 0.11 | 1.405 | 10.332 | 10.72 |

| PV 21177 | 140 | 0 | 0 | 0.105 | 0.11 | 0.59 | 2.817 | 2.698 |

| PV 21191 | 126 | 0 | 0 | 0.085 | 0.11 | 1.06 | 4.605 | 4.595 |

| PV 21200 | 126 | 0 | 0 | 0.080 | 0.11 | 0.985 | 4.905 | 5.048 |

| PV 21219 | 140 | 0.01 | 0.025 | 0.090 | 0.11 | 0.685 | 3.062 | 2.355 |

| PV 21220 | 140 | 0.01 | 0.025 | 0.090 | 0.11 | 0.685 | 3.062 | 2.354 |

| PV 21221 | 140 | 0.01 | 0.025 | 0.090 | 0.11 | 1.22 | 6.629 | 5.938 |

| PV 21222 | 140 | 0.01 | 0.025 | 0.090 | 0.11 | 1.41 | 8.540 | 8.05 |

| PV 21301 | 91 | 0 | 0 | 0.080 | 0.11 | 0.585 | 1.763 | 1.724 |

| PV 21313 | 175 | 0 | 0 | 0.085 | 0.11 | 1.22 | 8.282 | 8.581 |

| PV 21314 | 175 | 0 | 0 | 0.085 | 0.11 | 0.875 | 4.681 | 4.538 |

| PV 21370 | 210 | 0 | 0 | 0.100 | 0.11 | 0.7 | 5.502 | 5.602 |

| PV 21371 | 210 | 0 | 0 | 0.100 | 0.11 | 1.12 | 10.479 | 10.975 |

| PV 21372 | 175 | 0 | 0 | 0.105 | 0.11 | 0.815 | 5.924 | 6.139 |

| PV 21377 | 175 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.080 | 0.11 | 1.05 | 5.967 | 6.497 |

| PV 21378 | 175 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.080 | 0.11 | 0.7 | 4.130 | 4.707 |

| PV 21379 | 175 | 0 | 0 | 0.085 | 0.11 | 1.255 | 10.649 | 11.41 |

| PV 21380 | 175 | 0 | 0 | 0.085 | 0.11 | 1.22 | 8.282 | 8.647 |

| PV 21389 | 140 | 0 | 0 | 0.100 | 0.11 | 1.265 | 8.676 | 9.182 |

| PV 21390 | 140 | 0 | 0 | 0.100 | 0.11 | 1.59 | 10.724 | 11.207 |

| PV 21391 | 140 | 0 | 0 | 0.100 | 0.11 | 0.7 | 3.668 | 3.749 |

| PV 21392 | 105 | 0 | 0 | 0.085 | 0.11 | 1.26 | 6.413 | 6.841 |

| PV 21393 | 105 | 0 | 0 | 0.085 | 0.11 | 1.395 | 6.332 | 6.662 |

References

- Tang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Blaabjerg, F. Power electronics: The enabling technology for renewable energy integration. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 8, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademola-Idowu, A.; Zhang, B. Frequency stability using MPC-based inverter power control in low-inertia power systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 36, 1628–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, K.; Jain, S.K.; Padhy, P.K. Inertia estimation in modern power system: A comprehensive review. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 211, 108222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Li, G.; Zhang, R.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, T.; Li, X. Frequency control and optimal operation of low-inertia power systems with HVDC and renewable energy: A review. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 39, 4279–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatziargyriou, N.; Milanovic, J.; Rahmann, C.; Ajjarapu, V.; Canizares, C.; Erlich, I.; Hill, D.; Hiskens, I.; Kamwa, I.; Pal, B.; et al. Definition and classification of power system stability—Revisited & extended. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 36, 3271–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J.; Swami, A.K.; Jately, V.; Azzopardi, B. A comprehensive review of control strategies to overcome challenges during LVRT in PV systems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 121804–121834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsmadi, Y.M.; Xu, L.; Blaabjerg, F.; Ortega, A.J.P.; Abdelaziz, A.Y.; Wang, A.; Albataineh, Z. Detailed investigation and performance improvement of the dynamic behavior of grid-connected DFIG-based wind turbines under LVRT conditions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2018, 54, 4795–4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Hu, J.; Tang, W.; Song, G. Fault current analysis of type-3 WTs considering sequential switching of internal control and protection circuits in multi time scales during LVRT. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 6894–6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yao, J.; Liu, Y.; Pei, J.; Huang, S.; Chen, Z. Coupling mechanism analysis and transient stability assessment for multiparalleled wind farms during LVRT. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2021, 12, 2132–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Yao, J.; Liu, R.; Zeng, D.; Sun, P.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y. Characteristic analysis and risk assessment for voltage–frequency coupled transient instability of large-scale grid-connected renewable energy plants during LVRT. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 67, 5515–5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Qiao, Y.; Lu, Z. Cascading tripping out of numerous wind turbines in China: Fault evolution analysis and simulation study. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, 22–26 July 2012; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, B.; Sun, D.; Liu, D.; Zhou, Y. Identification method of cascading failure in high-proportion renewable energy systems based on deep learning. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Q.; Xue, Y. Quantitative assessment for commutation security based on extinction angle trajectory. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean. Energy 2020, 9, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsaeidi, S.; Dong, X.; Tzelepis, D.; Said, D.M.; Dysko, A.; Booth, C. A predictive control strategy for mitigation of commutation failure in LCC-based HVDC systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 34, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, X.P.; Yang, C. Series capacitor compensated AC filterless flexible LCC HVDC with enhanced power transfer under unbalanced faults. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 34, 3069–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Cai, Z.; Li, X.; Yu, C. Assessment of commutation failure in HVDC systems considering spatial-temporal discreteness of AC system faults. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2018, 6, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Li, Y.; Gole, A.M.; Duan, X. Computationally efficient and accurate approach for commutation failure risk areas identification in multi-infeed LCC-HVDC systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 35, 5238–5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Li, F. A novel evaluation method for the risk of simultaneous commutation failure in multi-infeed HVDC-systems that considers DC current rise. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 131, 107051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Tan, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Cai, Z.; Chen, Z. A hierarchical identification method of commutation failure risk areas in multi-infeed LCC-HVDC systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 39, 2093–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, L.; Karangelos, E.; Wehenkel, L. Recent developments in machine learning for energy systems reliability management. Proc. IEEE 2020, 108, 1656–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Caro, F.; Collin, A.J.; Giannuzzi, G.M.; Pisani, C.; Vaccaro, A. Review of data-driven techniques for on-line static and dynamic security assessment of modern power systems. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 130644–130673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandil, T.; Harris, A.; Das, R. Enhancing Fault Detection and Classification in Wind Farm Power Generation Using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) by Leveraging LVRT Embedded in Numerical Relays. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 104828–104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wu, D.; Botterud, A.; Yao, R.; Kang, C. Searching for critical power system cascading failures with graph convolutional network. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 2021, 8, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, M.-H.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Wu, X.; Hu, W.-X. Data-driven prediction method for characteristics of voltage sag based on fuzzy time series. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 134, 107394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, W.; Zhang, L. Real-time cascading failure risk evaluation with high penetration of renewable energy based on a graph convolutional network. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 38, 4122–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.A.; El-Hay, E.A.; Elkholy, M.M. An overview and case study of recent low voltage ride through methods for wind energy conversion system. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 183, 113521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahela, O.P.; Gupta, N.; Khosravy, M.; Patel, N. Comprehensive overview of low voltage ride through methods of grid integrated wind generator. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 99299–99326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-L.; Wu, Y.-K.; Chen, C.-K.; Wang, C.-H.; Chen, W.-T.; Cho, L.-I. A review of the low-voltage ride-through capability of wind power generators. Energy Procedia 2017, 141, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Standard GB/T 19963.1-2021; Technical Specification for Connecting Wind Farm to Power System—Part 1: On Shore Wind Power. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021. Available online: https://openstd.samr.gov.cn/bzgk/gb/newGbInfo?hcno=F0127C2B431AC283CD6ED17CE67F8E46 (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Chinese Standard GB/T 19964-2012; Technical Requirements for Connecting Photovoltaic Power Station to Power System. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2012. Available online: https://openstd.samr.gov.cn/bzgk/gb/newGbInfo?hcno=C14E31064526020C79250E150D261E1B (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- IEEE Std 2800TM–2022; IEEE Standard for Interconnection and Interoperability of Inverter-Based Resources (IBRs) Interconnecting with Associated Transmission Electric Power Systems. IEEE Standards Association: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Woodford, D.A. HVDC Transmission; Manitoba HVDC Research Centre: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1998; Volume 18, Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267938723_HVDC_Transmission (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Sun, H.; Xu, S.; Xu, T.; Guo, Q.; He, J.; Zhao, B.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Definition and index of short circuit ratio for multiple renewable energy stations. Proc. CSEE 2021, 41, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundur, P.; Paserba, J.; Ajjarapu, V.; Andersson, G.; Bose, A.; Canizares, C.; Hatziargyriou, N.; Hill, D.; Stankovic, A.; Taylor, C.; et al. Definition and classification of power system stability IEEE/CIGRE joint task force on stability terms and definitions. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2004, 19, 1387–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ye, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. STEPS: A portable dynamic simulation toolkit for electrical power system studies. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 36, 3216–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature Name | Symbol | Feature Description |

|---|---|---|

| Fault grounding impedance | zf | Fault information |

| Fault duration | T0 | |

| Mutual impedance between the equipment bus and the fault bus | Rif + jXif | |

| Equivalent impedance at the fault bus | Rff + jXff | Grid strength |

| Equivalent impedance at the equipment bus | Rii + jXii | |

| Pre-fault steady-state voltage at the fault bus | Uf0 | Grid operating condition |

| Pre-fault steady-state voltage at the renewable energy and DC bus | Ui0 |

| Feature Name | Symbol | Feature Description |

|---|---|---|

| Generator bus self-impedance | Rgg + jXgg | Supporting capability of the equipment’s adjacent area |

| Mutual impedance between equipment and near-area bus | Rib + jXib | |

| Multiple renewable energy stations short-circuit ratio | MRSCRi | |

| Active current coefficient during LVRT | kp1 | Renewable energy LVRT related control coefficients |

| Reactive current coefficient during LVRT | kq1 | |

| Active current coefficient during LVRT recovery | kp2 |

| State Transition Models | Machine Learning Model | Acc (%) | Pre (%) | Re (%) | F1 (%) | Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVRT | Logistic regression | 96.04% | 94.53% | 95.63% | 95.08% | 0.326 |

| Neural network | 97.33% | 95.10% | 98.39% | 96.72% | 3.058 | |

| SVM | 96.51% | 95.14% | 96.20% | 95.67% | 5.230 | |

| XGBoost | 99.36% | 98.63% | 99.78% | 99.20% | 1.839 | |

| WF Tripping | Logistic regression | 99.18% | 98.21% | 100% | 99.10% | 0.003 |

| PV Tripping | Logistic regression | 98.80% | 98.18% | 99.08% | 98.63% | 0.002 |

| CF | Logistic regression | 99.04% | 97.00% | 99.44% | 98.17% | 0.009 |

| Temporal Feature Models | Machine Learning Model | RMSE (ms) | MAE (ms) | R2 | Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVRT T1 | Linear regression | 18.82 | 10.14 | 0.11 | 0.004 |

| Neural network | 8.82 | 3.60 | 0.80 | 5.449 | |

| SVM | 12.69 | 4.17 | 0.59 | 9.462 | |

| XGBoost | 4.52 | 0.85 | 0.95 | 0.844 | |

| WT LVRT T2 | Linear regression | 42.80 | 29.34 | 0.53 | 0.006 |

| Neural network | 19.92 | 9.93 | 0.90 | 4.012 | |

| SVM | 19.20 | 10.88 | 0.91 | 0.634 | |

| XGBoost | 6.82 | 2.21 | 0.99 | 0.355 | |

| PV LVRT T2 | Linear regression | 41.52 | 27.22 | 0.48 | 0.041 |

| Neural network | 22.84 | 12.22 | 0.84 | 10.054 | |

| SVM | 25.74 | 17.81 | 0.80 | 7.674 | |

| XGBoost | 8.41 | 3.15 | 0.98 | 1.311 | |

| CF T1 | Linear regression | 33.20 | 24.26 | 0.37 | 0.002 |

| Neural network | 22.22 | 12.90 | 0.72 | 0.282 | |

| SVM | 10.18 | 7.74 | 0.94 | 0.117 | |

| XGBoost | 7.54 | 3.17 | 0.97 | 0.148 |

| Renewable Energy Station | Plvrt0 (MW) | kp1 | T0 (s) | T1 (s) | T2 (s) | T3 (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV 21130 | 84 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 1.565 |

| PV 21085 | 86.54 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.015 | 0.085 | 0.67 |

| WF 21171 | 76.72 | 0.4 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.005 | 1.07 |

| WF 21306 | 91 | 0.2 | 0.18 | 0 | 0.18 | 1.57 |

| Renewable Energy Station | Rlvrt1 (MW) | Rlvrt2 (MW) | Rlvrt3 (MW) | Rlvrt (MW) | Rlvrt,sim (MW) | Absolute Difference (MW) | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV 21130 | 0 | 0.84 | 5.916 | 6.756 | 6.707 | 0.049 | 0.73 |

| PV 21085 | 0 | 0.537 | 2.029 | 2.566 | 2.395 | 0.171 | 7.14 |

| WF 21171 | 0 | 0.270 | 2.221 | 2.491 | 2.599 | 0.108 | 4.16 |

| WF 21306 | 0 | 1.638 | 5.715 | 7.353 | 7.216 | 0.137 | 1.90 |

| Renewable Energy Station | Poff0 (MW) | T0 (s) | Roff1 (MW) | Roff (MW) | Roff,sim (MW) | Absolute Difference (MW) | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WF 21304 | 91 | 0.15 | 0.91 | 91.91 | 91.956 | 0.046 | 0.05% |

| WF 21306 | 91 | 0.18 | 0.91 | 91.91 | 91.956 | 0.046 | 0.05% |

| PV 21300 | 56 | 0.2 | 1.12 | 57.12 | 56.983 | 0.137 | 0.24% |

| DC | Pcf0 (MW) | T0 (s) | T1 (s) | T2 (s) | T3 (s) | tv3 (s) | Rcf1 (MW) | Rcf2 (MW) | Rcf3 (MW) | Rcf (MW) | Rcf,sim (MW) | Absolute Difference (MW) | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (124,119) | 1274.97 | 0.15 | 0 | 0.2 | 2.255 | 3.2 | 0 | 25.499 | 171.497 | 196.997 | 195.946 | 1.051 | 0.54% |

| (45,50) | 1856.25 | 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 3 | 3.957 | 0 | 37.125 | 332.914 | 370.039 | 373.872 | 3.833 | 1.03% |

| Evaluation Dimension | Evaluation Metric | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Fault identification results | Acc (%) | 98.25% |

| Re (%) | 100% | |

| Pre (%) | 98.25% | |

| Temporal parameter prediction results | RMSE T1 (s) | 0.0044 |

| MAE T1 (s) | 0.0014 | |

| RMSE WF-T2 (s) | 0.0248 | |

| MAE WF-T2 (s) | 0.0225 | |

| RMSE PV-T2 (s) | 0.0180 | |

| MAE PV-T2 (s) | 0.0159 | |

| Risk assessment | Absolute Difference (MW) | 2.992 |

| Relative Error (%) | 1.08% |

| Renewable Energy Station | Fault Prediction Result | LVRT T1 Prediction Result (s) | LVRT T2 Prediction Result (s) | Simulation Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WF 21227 | Tripping | —— | —— | 1.1 s tripping |

| WF 21228 | Tripping | —— | —— | 1.1 s tripping |

| WF 21238 | LVRT | 0 | 0.14 | 1 s LVRT, 1.14 s enters recovery state, 1.99 s enters normal operation state |

| WF 21239 | LVRT | 0 | 0.14 | 1 s LVRT, 1.14 s enters recovery state, 2.2 s enters normal operation state |

| PV 21125 | LVRT | 0 | 0.14 | 1 s LVRT, 1.14 s enters recovery state, 2.265 s enters normal operation state |

| PV 21139 | LVRT | 0 | 0.14 | 1 s LVRT, 1.14 s enters recovery state, 2.735 s enters normal operation state |

| Renewable Energy Station | Roff (MW) | Rlvrt (MW) | Roff,sim (MW) | Rlvrt,sim (MW) | Absolute Difference (MW) | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WF 21227 | 70.7 | —— | 70.735 | —— | 0.035 | 0.05% |

| WF 21228 | 70.7 | —— | 70.735 | —— | 0.035 | 0.05% |

| WF 21238 | —— | 2.233 | —— | 2.433 | 0.2 | 8.22% |

| WF 21239 | —— | 5.451 | —— | 5.901 | 0.45 | 7.63% |

| PV 21125 | —— | 6.195 | —— | 6.136 | 0.059 | 0.96% |

| PV 21139 | —— | 4.809 | —— | 4.622 | 0.187 | 4.05% |

| total | 141.4 | 18.688 | 141.47 | 19.092 | 0.474 | 0.30% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Qiu, S.; Peng, Y.; Li, C.; Tian, H.; Ma, C. Fast Risk Assessment for Receiving-End Power Grids with High Penetration of Renewable Energy Based on the Fault Transient Evolution Process. Processes 2026, 14, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010120

Qiu S, Peng Y, Li C, Tian H, Ma C. Fast Risk Assessment for Receiving-End Power Grids with High Penetration of Renewable Energy Based on the Fault Transient Evolution Process. Processes. 2026; 14(1):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010120

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiu, Shanshan, Yixuan Peng, Changgang Li, Hao Tian, and Changhui Ma. 2026. "Fast Risk Assessment for Receiving-End Power Grids with High Penetration of Renewable Energy Based on the Fault Transient Evolution Process" Processes 14, no. 1: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010120

APA StyleQiu, S., Peng, Y., Li, C., Tian, H., & Ma, C. (2026). Fast Risk Assessment for Receiving-End Power Grids with High Penetration of Renewable Energy Based on the Fault Transient Evolution Process. Processes, 14(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010120