Development and Characterization of Pinhão Extract Powders Using Inulin and Polydextrose as Prebiotic Carriers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Preparation of the Extract from Pinhão Almond

2.1.2. Preparation of the Extract for Drying

2.2. Physicochemical Characterization of the Powders

2.3. Powder Properties

2.3.1. Density

2.3.2. Fluidity and Cohesiveness

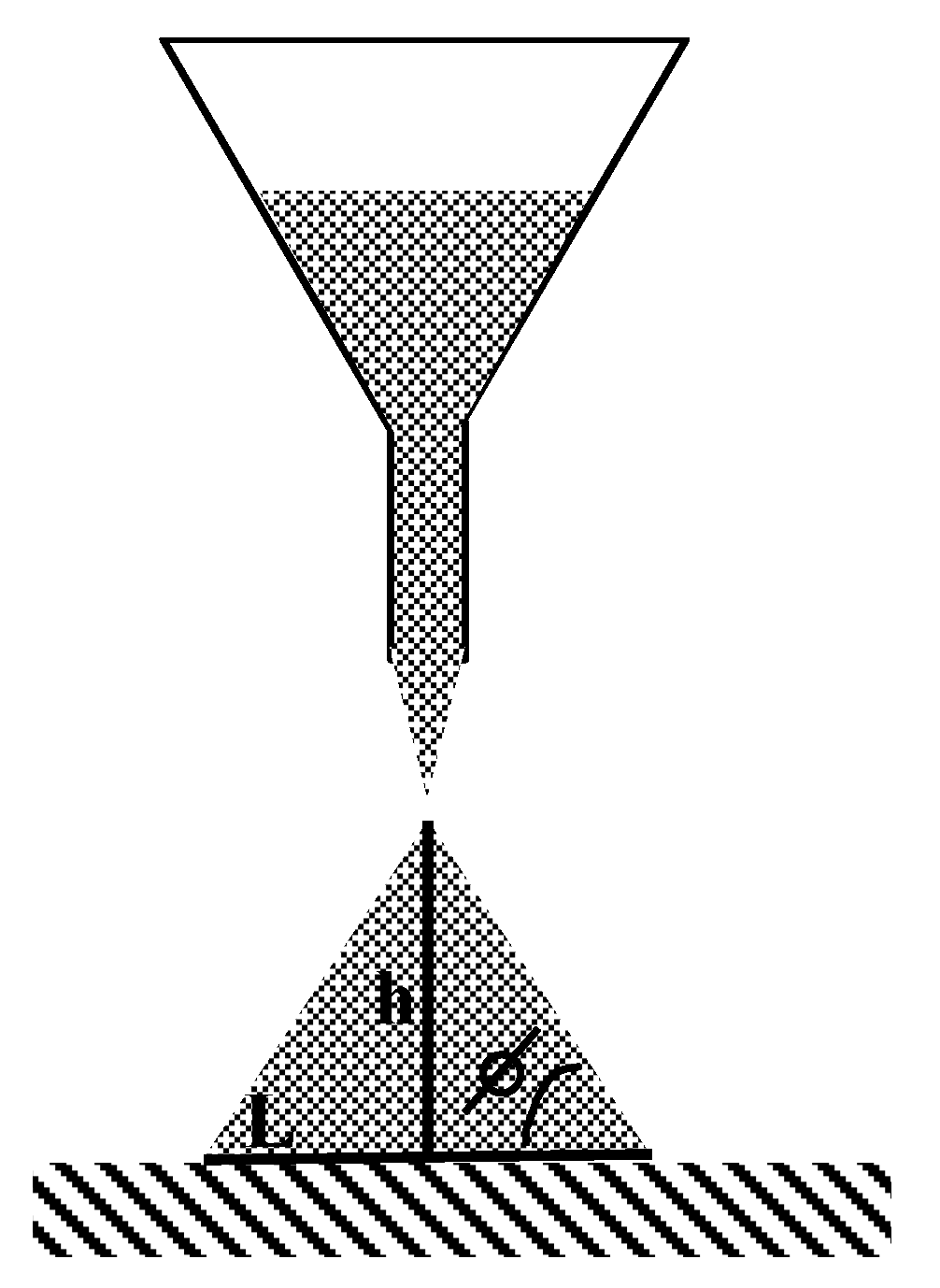

2.3.3. Flowability

2.4. Rehydration Properties

2.4.1. Wettability (WI)

2.4.2. Solubility

2.4.3. Dispersibility

2.5. Powder Yield

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.7. Individual Phenolic Compounds

2.8. Multi-Element Profile

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of the Powders

3.2. Properties of the Powders

3.3. Power Yield

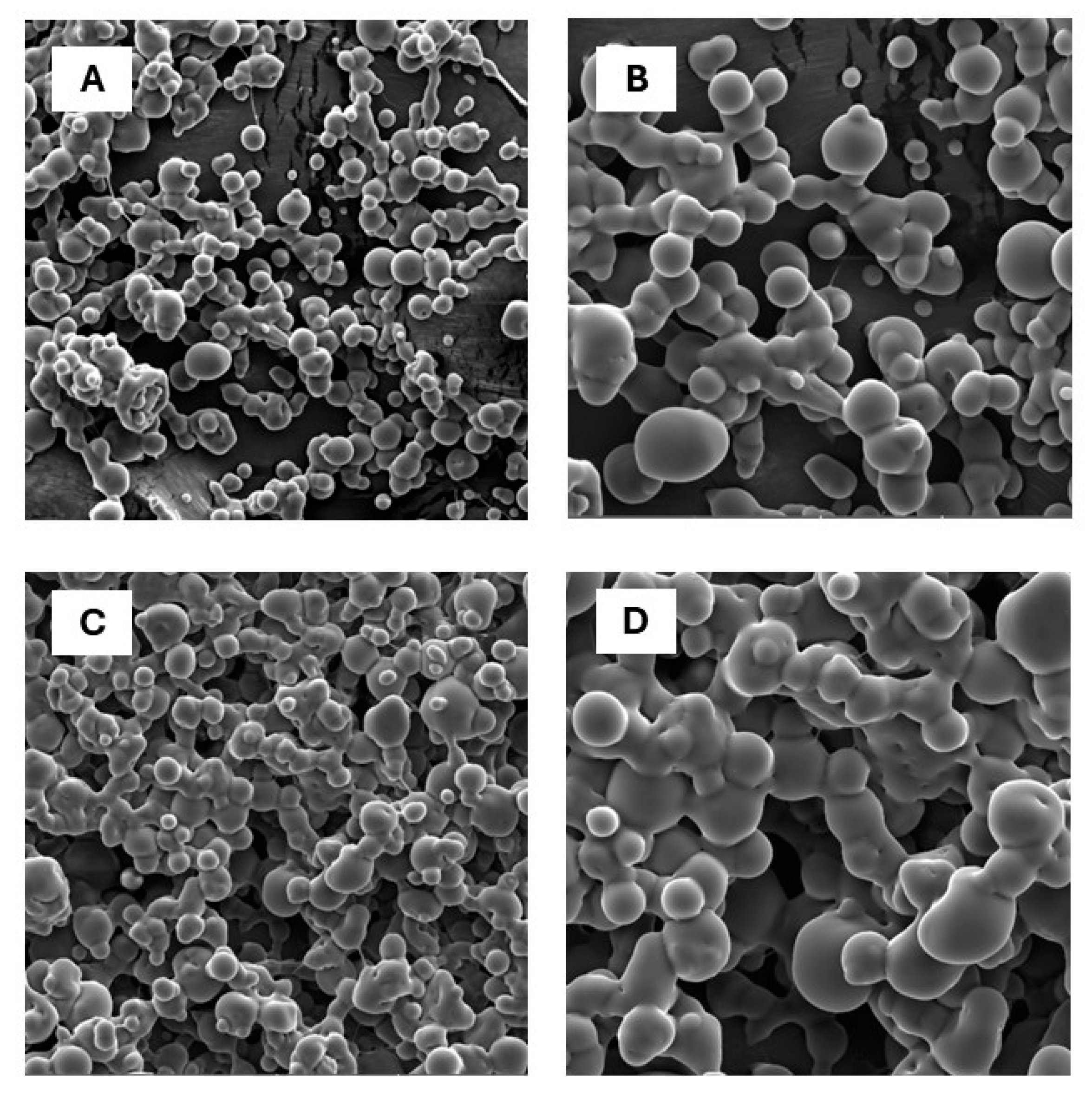

3.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy

3.5. Individual Phenolic Compounds

3.6. Multi-Element Profile

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barbosa, J.Z.; dos Santos Domingues, C.R.; Poggere, G.C.; Motta, A.C.V.; dos Reis, A.R.; de Moraes, M.F.; Prior, S.A. Elemental Composition and Nutritional Value of Araucaria Angustifolia Seeds from Subtropical Brazil. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 1073–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrillon, R.G.; Helm, C.V.; Mathias, A.L. Araucaria Angustifolia and the Pinhão Seed: Starch, Bioactive Compounds and Functional Activity—A Bibliometric Review. Ciência Rural 2023, 53, e20220048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadori, N.M.; da Conceição das Mercês, Z.; Evangelista, S.M.; Cochlar, T.B.; de Oliveira Rios, A.; de Oliveira, V.R. Overview of the Potential of Pine Nuts (Araucaria angustifolia) in New Food Options and Films: An Approach on Quality, Versatility and Sustainability. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 6916–6924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embrapa Florestas Valor Nutricional do Pinhão. Available online: http://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/handle/doc/1108204 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Rezende, Y.R.R.S.; Nogueira, J.P.; Narain, N. Microencapsulation of Extracts of Bioactive Compounds Obtained from Acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC) Pulp and Residue by Spray and Freeze Drying: Chemical, Morphological and Chemometric Characterization. Food Chem. 2018, 254, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Júnior, M.E.; Araújo, M.V.R.L.; Martins, A.C.S.; dos Santos Lima, M.; da Silva, F.L.H.; Converti, A.; Maciel, M.I.S. Microencapsulation by Spray-Drying and Freeze-Drying of Extract of Phenolic Compounds Obtained from Ciriguela Peel. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula Silva, C.R.; de Abreu Figueiredo, J.; Campelo, P.H.; Silveira, P.G.; das Chagas do Amaral Souza, F.; Yoshida, M.I.; Borges, S.V. Spray Drying of Aqueous South American Sapote (Matisia cordata) Extract: Influence of Dextrose Equivalent and Dietary Fiber on Physicochemical Properties. Food Bioproc. Tech. 2025, 18, 4658–4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marafon, K.; Pereira-Coelho, M.; da Silva Haas, I.C.; da Silva Monteiro Wanderley, B.R.; de Gois, J.S.; Vitali, L.; Luna, A.S.; Canella, M.H.M.; Hernández, E.; de Mello Castanho Amboni, R.D.; et al. An Opportunity for Acerola Pulp (Malpighia emarginata DC) Valorization Evaluating Its Performance during the Block Cryoconcentration by Physicochemical, Bioactive Compounds, HPLC–ESI-MS/MS, and Multi-Elemental Profile Analysis. Food Res. Int. 2024, 176, 113793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinipour, S.L.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Mofid, V.; Soltani, M.; Hosseini, H. Low-calorie Functional Dairy Dessert Enriched by Prebiotic Fibers and High Antioxidant Herbal Extracts: A Study of Optimization and Rheological Properties. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 7829–7841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, M.; Álvarez, K.; Loewe, V. Chemical Composition of Pine Nut (Pinus pinea L.) Grown in Three Geographical Macrozones in Chile. CyTA J. Food 2017, 15, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Liz, G.R.; Verruck, S.; Canella, M.H.M.; Dantas, A.; Garcia, S.G.; Maran, B.M.; Murakami, F.S.; Prudencio, E.S. Stability of Bifidobacteria Entrapped in Goat’s Whey Freeze Concentrate and Inulin as Wall Materials and Powder Properties. Food Res. Int. 2020, 127, 108752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verruck, S.; de Liz, G.R.; Dias, C.O.; de Mello Castanho Amboni, R.D.; Prudencio, E.S. Effect of Full-Fat Goat’s Milk and Prebiotics Use on Bifidobacterium BB-12 Survival and on the Physical Properties of Spray-Dried Powders under Storage Conditions. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.M.; Barbano, D.M. Kjeldahl Nitrogen Analysis as a Reference Method for Protein Determination in Dairy Products. J. AOAC Int. 1999, 82, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chever, S.; Méjean, S.; Dolivet, A.; Mei, F.; Den Boer, C.M.; Le Barzic, G.; Jeantet, R.; Schuck, P. Agglomeration during Spray Drying: Physical and Rehydration Properties of Whole Milk/Sugar Mixture Powders. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 83, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosky, L.; Asp, N.-G.; Furda, I.; Devries, J.W.; Schweizer, T.F.; Harland, B.F. Determination of Total Dietary Fiber in Foods and Food Products: Collaborative Study. J. AOAC Int. 1985, 68, 677–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDF Standard 26A:1993; Dried Milk and Dried Cream—Determination of Water Content. International Dairy Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 1993.

- Reddy, R.S.; Ramachandra, C.T.; Hiregoudar, S.; Nidoni, U.; Ram, J.; Kammar, M. Influence of Processing Conditions on Functional and Reconstitution Properties of Milk Powder Made from Osmanabadi Goat Milk by Spray Drying. Small Rumin. Res. 2014, 119, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudeiro, R.L.; Ferreira, M.C. Avaliação de índices de escoabilidade de pós obtidos a partir da secagem de suspensões em leitos de jorro. In Proceedings of the Anais do X Congresso Brasileiro de Engenharia Química; Editora Edgard Blücher: São Paulo, Brazil, 2014; pp. 312–317. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, R.V.d.B.; Borges, S.V.; Botrel, D.A. Gum Arabic/Starch/Maltodextrin/Inulin as Wall Materials on the Microencapsulation of Rosemary Essential Oil. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, T.M.P.; da Silva Haas, I.C.; da Costa, M.A.J.L.; Luna, A.S.; de Gois, J.S.; Amboni, R.D.D.M.C.; Prudencio, E.S. Dairy Powder Enriched with a Soy Extract (Glycine max): Physicochemical and Polyphenolic Characteristics, Physical and Rehydration Properties and Multielement Composition. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 112144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, S.C.; Siow, L.F.; Lee, Y.Y. Yield Optimization of Clean Label Palm Kernel Milk Powder Produced Using Dehumidified Air Spray Drying Technique through Response Surface Methodology: Comparison of Powder Characteristics with Conventional Spray Drying. Powder Technol. 2025, 467, 121512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juranović Cindrić, I.; Kunštić, M.; Zeiner, M.; Stingeder, G.; Rusak, G. Sample Preparation Methods for the Determination of the Antioxidative Capacity of Apple Juices. Croat. Chem. Acta 2011, 84, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.F.R.; da Silva Santos, B.R.; Minho, L.A.C.; Brandão, G.C.; de Jesus Silva, M.; Silva, M.V.L.; dos Santos, W.N.L.; dos Santos, A.M.P. Characterization of the Chemical Composition (Mineral, Lead and Centesimal) in Pine Nut (Araucaria angustifolia (Bertol.) Kuntze) Using Exploratory Data Analysis. Food Chem. 2022, 369, 130672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenço, S.C.; Moldão-Martins, M.; Alves, V.D. Microencapsulation of Pineapple Peel Extract by Spray Drying Using Maltodextrin, Inulin, and Arabic Gum as Wall Matrices. Foods 2020, 9, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, F.; Azevedo, E.S.; Noreña, C.P.Z. Behavior of Inulin, Polydextrose, and Egg Albumin as Carriers of Bougainvillea Glabra Bracts Extract: Rheological Performance and Powder Characterization. J. Food Process Preserv. 2020, 44, e14834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Castejón, M.L.; Bengoechea, C.; Espinosa, S.; Carrera, C. Characterization of Prebiotic Emulsions Stabilized by Inulin and β-Lactoglobulin. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 87, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Narváez, F.; Medina-Pineda, Y.; Contreras-Calderón, J. Evaluation of the Heat Damage of Whey and Whey Proteins Using Multivariate Analysis. Food Res. Int. 2017, 102, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parthasarathi, S.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Enhancement of Oral Bioavailability of Vitamin E by Spray-Freeze Drying of Whey Protein Microcapsules. Food Bioprod. Process. 2016, 100, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisuvor, N.; Chinprahast, N.; Prakitchaiwattana, C.; Subhimaros, S. Effects of Inulin and Polydextrose on Physicochemical and Sensory Properties of Low-Fat Set Yoghurt with Probiotic-Cultured Banana Purée. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 51, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Liao, M.; Qian, Y.; Yuan, X.; Li, J.; Ma, L.; Miao, S.; Reitmaier, M.; Kharaghani, A.; Först, P.; et al. Toward Improving the Rehydration of Dairy Powders: A Comprehensive Review of Applying Physical Technologies. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N.F.N.N.A.; Zubairi, S.I.; Hashim, H.; Yaakob, H. Revolutionizing Spray Drying: An In-Depth Analysis of Surface Stickiness Trends and the Role of Physicochemical Innovations in Boosting Productivity. J. Food Qual. 2024, 2024, 8929464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Miao, S. Physical Properties and Stickiness of Spray-Dried Food Powders. In Spray Drying for the Food Industry; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2024; pp. 551–571. [Google Scholar]

- Sundararajan, P.; Moser, J.; Williams, L.; Chiang, T.; Riordan, C.; Metzger, M.; Zhang-Plasket, F.; Wang, F.; Collins, J.; Williams, J. Driving Spray Drying towards Better Yield: Tackling a Problem That Sticks Around. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zortéa-Guidolin, M.E.B.; Demiate, I.M.; de Godoy, R.C.B.; Scheer, A.d.P.; Grewell, D.; Jane, J. Structural and Functional Characterization of Starches from Brazilian Pine Seeds (Araucaria angustifolia). Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 63, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparino, O.A.; Tang, J.; Nindo, C.I.; Sablani, S.S.; Powers, J.R.; Fellman, J.K. Effect of Drying Methods on the Physical Properties and Microstructures of Mango (Philippine ‘Carabao’ Var.) Powder. J. Food Eng. 2012, 111, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Ma, S.; Wang, M.; Feng, X.-Y. Characterization of Free, Conjugated, and Bound Phenolic Acids in Seven Commonly Consumed Vegetables. Molecules 2017, 22, 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Mumper, R.J. Plant Phenolics: Extraction, Analysis and Their Antioxidant and Anticancer Properties. Molecules 2010, 15, 7313–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.M.; Zanqui, A.B.; Souza, A.H.P.; Gohara, A.K.; Gomes, S.T.M.; da Silva, E.A.; Filho, L.C.; Matsushita, M. Extraction of Oil and Bioactive Compounds from Araucaria angustifolia (Bertol.) Kuntze Using Subcritical n-Propane and Organic Solvents. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2016, 112, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, A.U.; Correia, R.; Longo, A.; Nobre, C.; Alves, O.; Santos, M.; Gonçalves, M.; Miranda, I.; Pereira, H. Chemical Composition, Morphology, Antioxidant, and Fuel Properties of Pine Nut Shells within a Biorefinery Perspective. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 14505–14517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, M.F.; Ali, A.; Ain, H.B.U.; Kausar, S.; Khalil, A.A.; Aadil, R.M.; Zeng, X.-A. Bioaccessibility mechanisms, fortification strategies, processing impact on bioavailability, and therapeutic potentials of minerals in cereals. Future Foods 2024, 10, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirhan, H.; Karabudak, E. Effects of Inulin on Calcium Metabolism and Bone Health. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2023, 93, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, F.; Santos Dorneles, M.; Pelayo Zapata Noreña, C. Accelerated Stability Testing and Simulated Gastrointestinal Release of Encapsulated Betacyanins and Phenolic Compounds from Bougainvillea Glabra Bracts Extract. Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malta, D.S.; de Lima, G.G.; Arantes, M.S.T.; de Lacerda, A.E.B.; Mathias, A.L.; Magalhães, W.L.E.; Helm, C.V.; Masson, M.L. Linking Geographical Origin with Nutritional, Mineral, and Visual Proprieties of Pinhão (Araucaria angustifolia Seed) from the South of Brazil. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 4738–4750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucharska-Guzik, A.; Guzik, Ł.; Charzyńska, A.; Michalska-Ciechanowska, A. Influence of Freeze Drying and Spray Drying on the Physical and Chemical Properties of Powders from Cistus creticus L. Extract. Foods 2025, 14, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Daily Value Nutrition and Supplement-Facts Labels. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-facts-label/daily-value-nutrition-and-supplement-facts-labels (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Whisner, C.M.; Castillo, L.F. Prebiotics, Bone and Mineral Metabolism. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2018, 102, 443–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.; Jung, S.-C.; Kwak, K.; Kim, J.-S. The Role of Prebiotics in Modulating Gut Microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandura Jarić, A.; Haramustek, L.; Nižić Nodilo, L.; Vrsaljko, D.; Petrović, P.; Kuzmić, S.; Jozinović, A.; Aladić, K.; Jokić, S.; Šeremet, D.; et al. A Novel Approach to Serving Plant-Based Confectionery—The Employment of Spray Drying in the Production of Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Based Delivery Systems Enriched with Teucrium montanum L. Extract. Foods 2024, 13, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| % CMC | % Inulin | % Polydextrose | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | 0.3 | 30 | |

| E2 | 0.3 | 30 |

| Angle of Repose (°) | Flow Criteria |

|---|---|

| 25–30 | Very free |

| 31–38 | Free |

| 39–45 | Fair |

| 46–55 | Cohesive |

| >55 | Very difficult |

| Physicochemical Parameters | E1 | E2 |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins (g/100 g) | 0.07 a ± 0.10 | 0.07 a ± 0.12 |

| Lipids (g/100 g) | ND | ND |

| Carbohydrates (g/100 g) | 37.00 a ± 0.20 | 26.14 b ± 0.10 |

| Fibers (g/100 g) | 34.10 a ± 0.30 | 24.40 b ± 0.10 |

| Moisture (g/100 g) | 1.35 b ± 0.08 | 1.83 a ± 0.12 |

| Water activity | 0.16 b ± 0.12 | 0.22 a ± 0.10 |

| Asher (g/100 g) | 0.54 a ± 0.13 | 0.52 a ± 0.02 |

| pH | 4.80 a ± 0.15 | 4.72 b ± 0.10 |

| Color parameters | ||

| L* | 96.67 a ± 0.13 | 93.52 b ± 0.21 |

| a* | 2.25 b ± 0.08 | 2.75 a ± 0.11 |

| b* | 7.92 b ± 0.20 | 11.05 a ± 0.21 |

| ∆E | 6.90 a ± 0.20 | 3.25 b ± 0.14 |

| Physical Properties | E1 | E2 |

|---|---|---|

| Loose bulk density (g/cm3) | 0.46 a ± 0.11 | 0.42 b ± 0.10 |

| Tapped bulk density (g/cm3) | 0.54 a ± 0.20 | 0.49 b ± 0.15 |

| Flowability (Carr’s index) (%) | 15.36 a ± 2.00 | 12.86 b ± 0.25 |

| Cohesiveness (Hausner ratio) | 1.18 a ± 0.10 | 1.14 a ± 0.18 |

| Powder Flow (º) | 25.46 b ± 0.31 | 37.70a ± 0.29 |

| Rehydration Properties | ||

| Solubility (%) | 39.11 a ± 0.10 | 39.55 a ± 0.16 |

| Wettability (s) | 213 b ± 3.55 | 551 a ± 7.87 |

| Dispersibility (%) | 57.83 b ± 2.24 | 65.50 a ± 1.08 |

| Phenolic Compounds | E1; E2 | LOQ | LOD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gallic acid (µg/g) | 0.08 ± 0.05 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.001 |

| Protocatechuic acid (µg/g) | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.001 |

| Vanillic acid (µg/g) | 0.81 ± 0.02 | 0.60 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.001 |

| Syringic acid (µg/g) | 0.60 ± 0.01 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.001 |

| Transcinnamic acid (µg/g) | 0.53 ± 0.03 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.001 |

| Caffeic acid (µg/g) | 0.007 ± 0.001 | 0.006 ± 0.001 | 0.002 ± 0.0001 |

| Coumaric acid (µg/g) | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.001 |

| Rutin (µg/g) | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.001 |

| Quercetin (µg/g) | 0.70 ± 0.01 | 0.60 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.001 |

| Elements (μg/g) | E1 | E2 |

|---|---|---|

| Ca | 42.60 a ± 0.80 | 36.50 b ± 0.30 |

| Cu | Present | Present |

| Fe | 9.40 b ± 2.60 | 25.00 a ± 1.80 |

| K | 1209.60 b ± 9.70 | 1379.80 a ± 22.80 |

| Mg | 82.80 a ± 2.00 | 73.80 b ± 0.70 |

| Mn | Present | Present |

| Na | 614.70 a ± 5.70 | 600.20 b ± 8.60 |

| P | 236.20 b ± 7.50 | 271.40 a ± 4.50 |

| S | Present | Present |

| Sr | <LOD | <LOD |

| Zn | 4.30 b ± 1.40 | 12.50 a ± 1.60 |

| Al | <LOD | <LOD |

| Cd | <LOD | <LOD |

| Co | <LOD | <LOD |

| Cr | <LOD | <LOD |

| Pb | <LOD | <LOD |

| Se | <LOD | <LOD |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Marafon, K.; Carvalho, A.C.F.; Prestes, A.A.; de Souza, C.K.; Andrade, D.R.M.; Helm, C.V.; Pereira, F.N.; Tedeschi, P.; de Gois, J.S.; Prudencio, E.S. Development and Characterization of Pinhão Extract Powders Using Inulin and Polydextrose as Prebiotic Carriers. Processes 2026, 14, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010119

Marafon K, Carvalho ACF, Prestes AA, de Souza CK, Andrade DRM, Helm CV, Pereira FN, Tedeschi P, de Gois JS, Prudencio ES. Development and Characterization of Pinhão Extract Powders Using Inulin and Polydextrose as Prebiotic Carriers. Processes. 2026; 14(1):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010119

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarafon, Karine, Ana Caroline Ferreira Carvalho, Amanda Alves Prestes, Carolina Krebs de Souza, Dayanne Regina Mendes Andrade, Cristiane Vieira Helm, Fernanda Nunes Pereira, Paola Tedeschi, Jefferson Santos de Gois, and Elane Schwinden Prudencio. 2026. "Development and Characterization of Pinhão Extract Powders Using Inulin and Polydextrose as Prebiotic Carriers" Processes 14, no. 1: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010119

APA StyleMarafon, K., Carvalho, A. C. F., Prestes, A. A., de Souza, C. K., Andrade, D. R. M., Helm, C. V., Pereira, F. N., Tedeschi, P., de Gois, J. S., & Prudencio, E. S. (2026). Development and Characterization of Pinhão Extract Powders Using Inulin and Polydextrose as Prebiotic Carriers. Processes, 14(1), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010119