Graphene-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks for Advanced Wastewater Treatment: A Review of Synthesis, Characterization, and Micropollutant Removal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Summary on Structure and Properties

2.1. Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs)

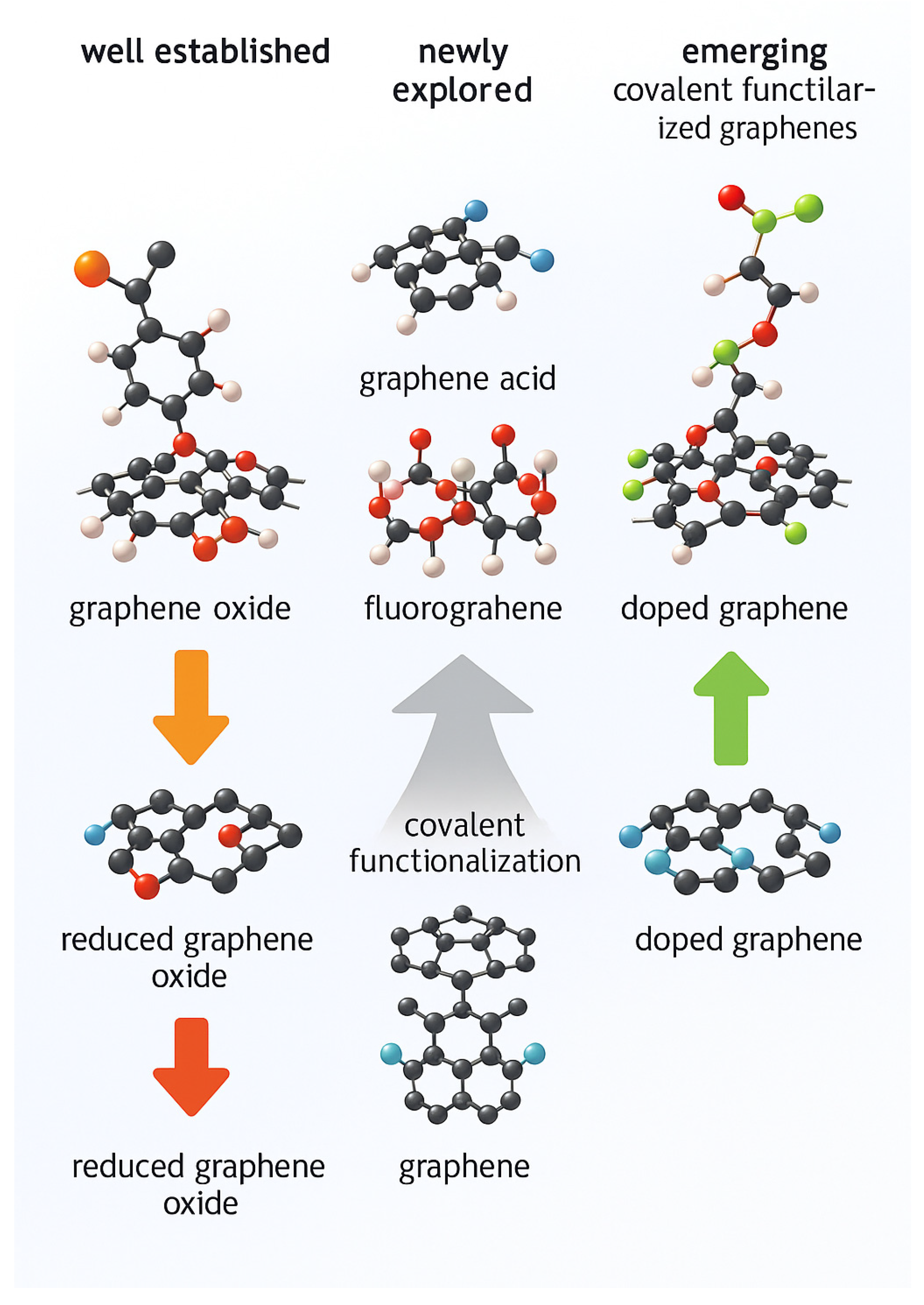

2.2. Graphene

2.3. Graphene/MOFs

2.4. Specific Examples of G@MOFs for Water Treatment

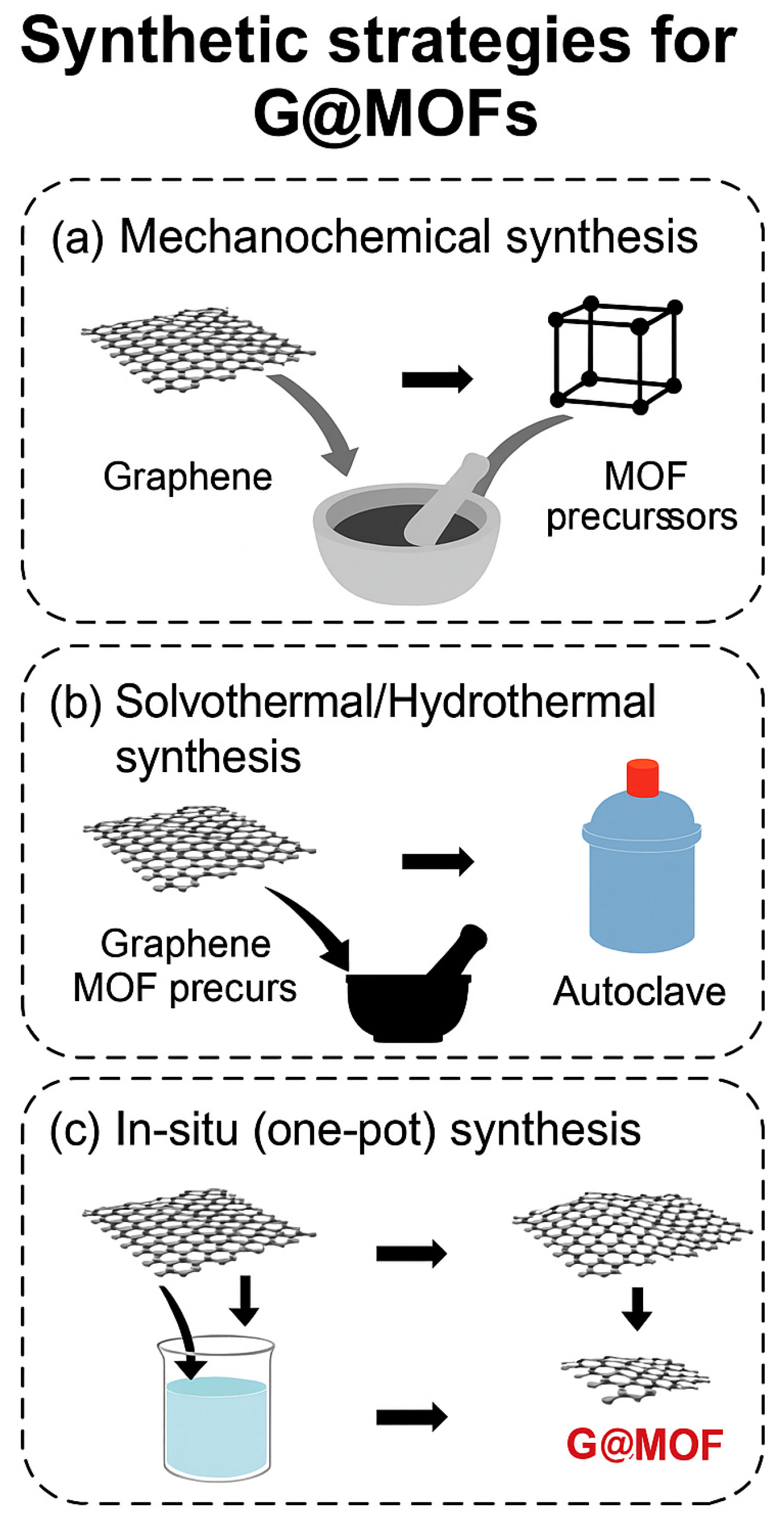

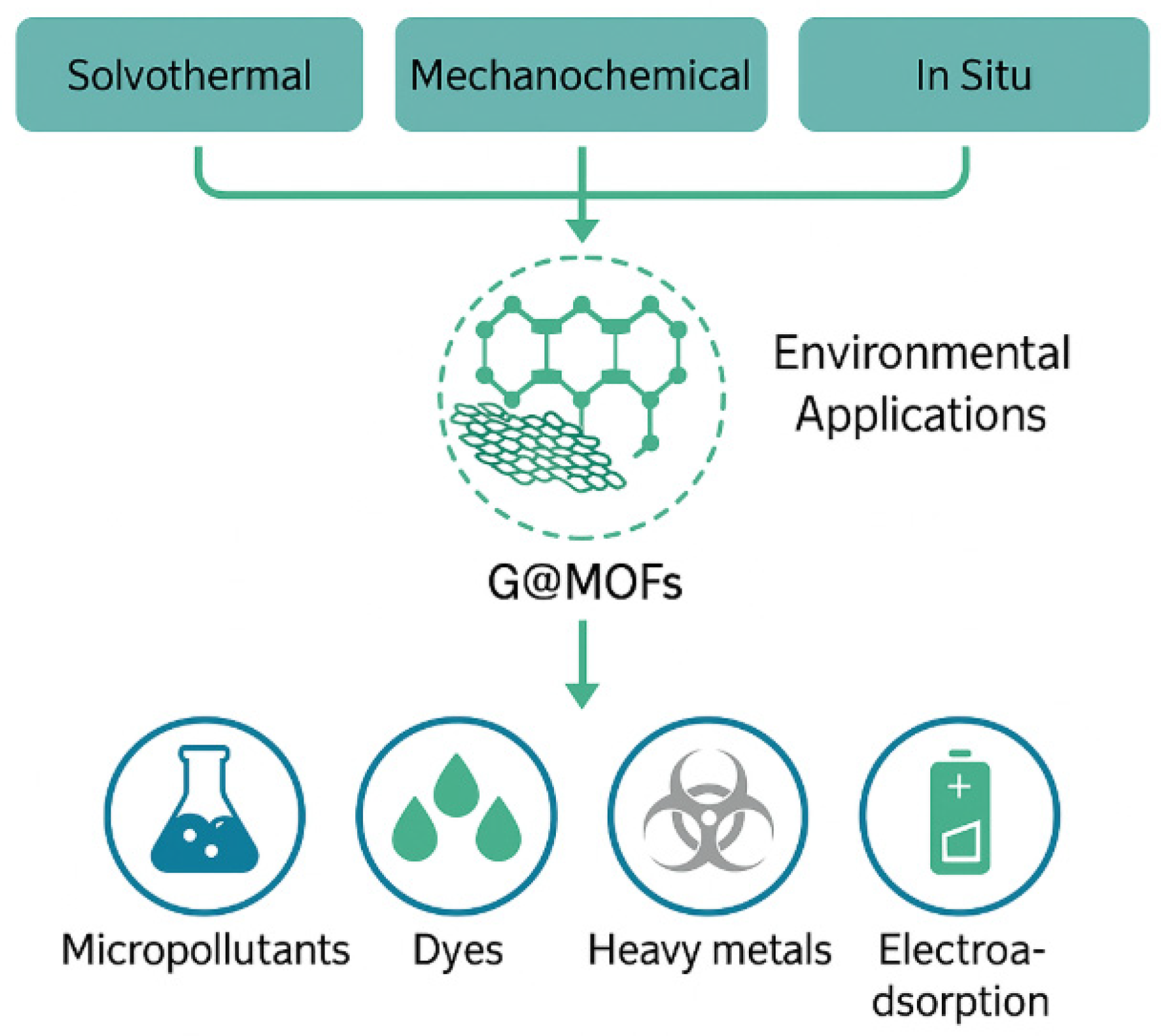

3. Synthetic Strategies for GMOFs

4. G@MOFs Characterization and Importance

4.1. Characterization Techniques

4.1.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

4.1.2. Spectroscopy

4.1.3. Electronic Microscopy

4.1.4. Nitrogen Adsorption–Desorption Analysis

4.2. Importance of Characterization

5. Environmental Applications of GMOFs

6. Micropollutant Removal with GMOFs

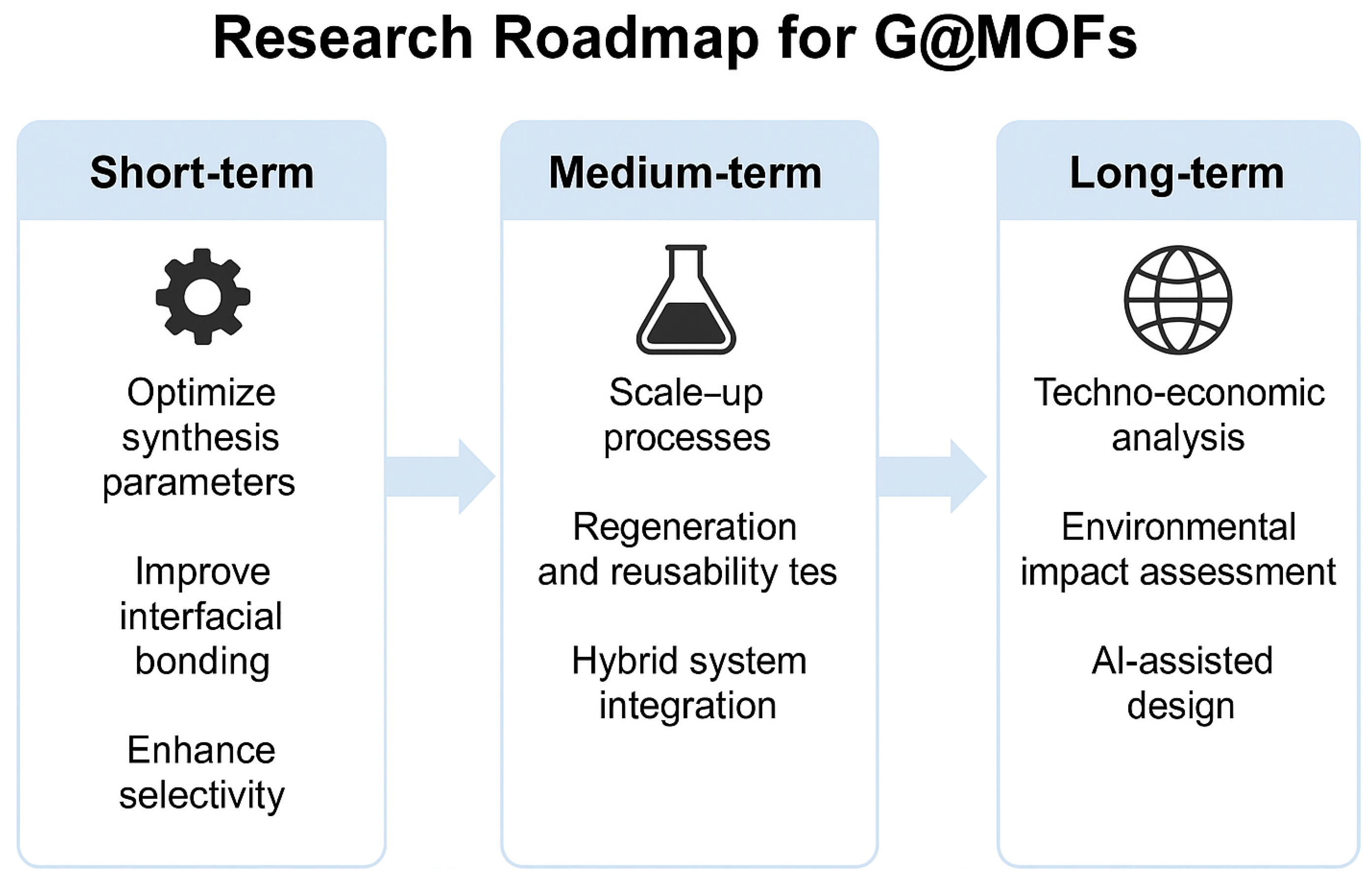

7. Future Prospects and Developments

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shinde, S.K.; Kim, D.Y.; Kumar, M.; Murugadoss, G.; Ramesh, S.; Tamboli, A.M.; Yadav, H.M. MOFs-graphene composites synthesis and application for electrochemical supercapacitor: A review. Polymers 2022, 14, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Tang, Y.; Cao, W.; Cui, Y.; Qian, G. Highly efficient encapsulation of doxorubicin hydrochloride in metal–organic frameworks for synergistic chemotherapy and chemodynamic therapy. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 4999–5006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajdari, F.B.; Kowsari, E.; Shahrak, M.N.; Ehsani, A.; Kiaei, Z.; Torkzaban, H.; Ershadi, M.; Eshkalak, S.K.; Haddadi-Asl, V.; Chinnappan, A. A review on the field patents and recent developments over the application of metal organic frameworks (MOFs) in supercapacitors. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 422, 213441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhout, S.; Haboubi, K.; El Abdouni, A.; El Hammoudani, Y.; Haboubi, C.; Dimane, F.; Hanafi, I.; Elyoubi, M.S. Appraisal of Groundwater Quality Status in the Ghiss-Nekor Coastal Plain. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 24, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, A.K.; Joshi, K.K.; Bachheti, A.; Vashishth, D.S. Impact of water pollution on waterbirds: A Review. Environ. Conserv. J. 2025, 26, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgin, J.; Ramos, C.G.; de Oliveira, J.S.; Dehmani, Y.; El Messaoudi, N.; Meili, L.; Franco, D.S.J.S. A critical review of the advances and current status of the application of adsorption in the remediation of micropollutants and dyes through the use of emerging bio-based nanocomposites. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñafiel, R.; Flores Tapia, N.E.; Mayacela Rojas, C.M.; Lema Chicaiza, F.R.; Pérez, L. Electrocoagulation Coupled with TiO2 Photocatalysis: An Advanced Strategy for Treating Leachates from the Degradation of Green Waste and Domestic WWTP Biosolids in Biocells. Processes 2025, 13, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazaiza, M.Y.D.; Alzghoul, T.M.; Nassani, D.E.; Bashir, M.J.K. Natural Coagulants for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment: Current Global Research Trends. Processes 2025, 13, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, G.; Wang, B. Regulating defective sites for pharmaceuticals selective removal: Structure-dependent adsorption over continuously tunable pores. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 442, 130025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, N.; Gong, X.; Sun, W.; Yu, C. Advanced applications of Zr-based MOFs in the removal of water pollutants. Chemosphere 2021, 267, 128863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gethami, W.; Qamar, M.A.; Shariq, M.; Alaghaz, A.N.M.; Farhan, A.; Areshi, A.A.; Alnasir, M.H. Emerging environmentally friendly bio-based nanocomposites for the efficient removal of dyes and micropollutants from wastewater by adsorption: A comprehensive review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 2804–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, E.; Lee, S.; Kang, E.; Kim, Y.; Choe, W. Metal-organic frameworks as advanced adsorbents for pharmaceutical and personal care products. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 425, 213526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, J.; Ramesh, K.; Chellam, P.V. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) as a catalyst for advanced oxidation processes—Micropollutant removal. In Advanced Materials for Sustainable Environmental Remediation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Liang, K. Nanobiohybrids: Synthesis strategies and environmental applications from micropollutants sensing and removal to global warming mitigation. Environ. Res. 2023, 232, 116317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achoukhi, I.; El Hammoudani, Y.; Dimane, F.; Haboubi, K.; Bourjila, A.; Haboubi, C.; Benaissa, C.; Elabdouni, A.; Faiz, H. Investigating Microplastics in the Mediterranean Coastal Areas—Case Study of Al-Hoceima Bay, Morocco. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 24, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.; Zaheer, B.; Sajid, F.; Ibrahim, A.; Shah, A.A.; Chandio, A.D. Exploring the Synergistic Effects of Ni-MOF@ PANI/GO Ternary Nanocomposite for High-Performance Supercapacitor Electrodes. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Mashkoor, F.; Nasar, A. Development, characterization, and utilization of magnetized orange peel waste as a novel adsorbent for the confiscation of crystal violet dye from aqueous solution. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 10, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, T.A.; Mustaqeem, M.; Khaled, M. Water treatment technologies in removing heavy metal ions from wastewater: A review. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2022, 17, 100617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzani, A.; El Hammoudani, Y.; Dimane, F.; Tahiri, M.; Haboubi, K. Characterization of Leachate and Assessment of the Leachate Pollution Index—A Study of the Controlled Landfill in Fez. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2024, 25, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Du, G.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Song, W.; Sheng, Q.; Luo, Y. Label-free fluorescence aptasensor for the detection of patulin using target-induced DNA gates and TCPP/BDC-NH2 mixed ligands functionalized Zr-MOF systems. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 217, 114723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wu, S.; Wu, Y.; Sun, B.; Zhang, P.; Tang, K. Lipase AK from Pseudomonas fluorescens immobilized on metal organic frameworks for efficient biosynthesis of enantiopure (S)− 1-(4-bromophenyl) ethanol. Process Biochem. 2023, 124, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouabdallah, A.; El Hammoudani, Y.; Dimane, F.; Haboubi, K.; Rhayour, K.; Benaissa, C. Impact of Waste on the Quality of Water Resources—Case Study of Taza City, Morocco. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2023, 24, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, A.; Manteghi, F. Metal-organic framework composites for water splitting. In Applications of Metal-Organic Framework Composites; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 277–310. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y.; Sun, D.; Li, J.; Ostovan, A.; Wang, X.; Ma, J.; You, J.; Muhammad, T.; Chen, L.; Arabi, M. The metal-and covalent-organic frameworks-based molecularly imprinted polymer composites for sample pretreatment. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 178, 117830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ma, J.; Cheng, J.; Wu, G.; Wang, S.; Huang, C.; Li, J.; Chen, L.J.L. Metal–Organic Framework-Based Composites for the Adsorption Removal of Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances from Water. Langmuir 2024, 40, 2815–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Duan, W.; Ma, H.; Su, J.; Liu, S.; Qiao, Y.; Zheng, R.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y. Enhanced prediction of tetracycline adsorption capacity in metal–organic frameworks using cross-layer ResNet. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378, 134707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Salazar, M. Adsorption of Methylene Blue, Congo Red, and Methyl Orange in Aqueous Solutions by MOF Co-Cl and Co-Br. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Nuevo León, Mexico, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, Y.; Yuan, P.J.C.; Physicochemical, S.A.; Aspects, E. Optimization of electrospun amidoximated siliceous mesocellular foam-cellulose membranes for selective extraction of uranium. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 707, 135898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademi, G.; Mohammadi, H.; Simon, D. Gradient-based multi-objective feature selection for gait mode recognition of transfemoral amputees. Sensors 2019, 19, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, V.F.; Malek, N.I.; Kailasa, S.K. Review on Metal–Organic Framework Classification, Synthetic Approaches, and Influencing Factors: Applications in Energy, Drug Delivery, and Wastewater Treatment. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 44507–44531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Ma, J.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, L. Functional metal–organic frameworks as adsorbents used for water decontamination: Design strategies and applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 6747–6771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, S.; Wu, G.; Arabi, M.; Tan, F.; Guan, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, L. Preparation of magnetic metal-organic frameworks with high binding capacity for removal of two fungicides from aqueous environments. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 90, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaramulu, K.; Mukherjee, S.; Morales, D.M.; Dubal, D.P.; Nanjundan, A.K.; Schneemann, A.; Masa, J.; Kment, S.; Schuhmann, W.; Otyepka, M. Graphene-based metal–organic framework hybrids for applications in catalysis, environmental, and energy technologies. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 17241–17338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, D.; Rakhi Mol, K.; Anand, G.; Nandamol, P.; Das, D.; Porel, M. Environmental pollutants such as endocrine disruptors/pesticides/reactive dyes and inorganic toxic compounds metals, radionuclides, and metalloids and their impact on the ecosystem. In Biotechnology for Environmental Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 391–442. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, S.; Chandra, A.; Kumar, V.; Bharti, S. Environmental pollutants: Endocrine disruptors/pesticides/reactive dyes and inorganic toxic compounds metals, radionuclides, and metalloids and their impact on the ecosystem. In Biotechnology for Environmental Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 55–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi, N.; Mir, M.A.; Chang, S.K.; Abdelli, N.; Hasnain, S.M.; Ali Khan, M.A.; Andrews, K. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products as emerging contaminants: Environmental fate, detection, and mitigation strategies. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2025, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latosińska, J.; Grdulska, A. A Review of Methods for the Removal of Endocrine-Disrupting Compounds with a Focus on Oestrogens and Pharmaceuticals Found in Wastewater. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, M.; Raji, S.; Al-Fatesh, H.; Czermak, P.; Ebrahimi, M. The occurrence of micropollutants in the aquatic environment and technologies for their removal. Processes 2025, 13, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagatee, S.; Priyadarshini, S.; Kumbhar, M.M.; Tudu, J.; Das, A.P. An insight into implementing advanced techniques for the removal of emerging micropollutants from wastewater. In Decarbonization of Wastewater Pollutants as a Sustainable Solution; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2026; pp. 331–352. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Sun, D.; Wen, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Song, Z.; Liu, H.; Ma, J.; Chen, L. Molecularly imprinted polymers and porous organic frameworks based analytical methods for disinfection by-products in water and wastewater. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 124249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Schukraft, G.E.; L’Hermitte, A.; Xiong, Y.; Brillas, E.; Petit, C.; Sirés, I. Mechanism and stability of an Fe-based 2D MOF during the photoelectro-Fenton treatment of organic micropollutants under UVA and visible light irradiation. Water Res. 2020, 184, 115986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Chen, C.; Shen, W.; Quan, H.; Chen, S.; Xie, S.; Luo, X.; Guo, L. MOF-derived magnetic porous carbon-based sorbent: Synthesis, characterization, and adsorption behavior of organic micropollutants. Adv. Powder Technol. 2017, 28, 1769–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heu, R.; Ateia, M.; Awfa, D.; Punyapalakul, P.; Yoshimura, C. Photocatalytic degradation of organic micropollutants in water by Zr-MOF/GO composites. J. Compos. Sci. 2020, 4, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Ma, J.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Jiang, B.; Luo, S.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Guan, Y.; Chen, L. Cationic metal-organic frameworks as an efficient adsorbent for the removal of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid from aqueous solutions. Environ. Res. 2020, 186, 109542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboubi, K.; El Abdouni, A.; El Hammoudani, Y.; Dimane, F.; Haboubi, C. Estimating biogas production in the controlled landfill of fez (morocco) using the land-gem model. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2023, 22, 1813–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuhadiya, S.; Suthar, D.; Patel, S.; Dhaka, M. Metal organic frameworks as hybrid porous materials for energy storage and conversion devices: A review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 446, 214115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abednatanzi, S.; Derakhshandeh, P.G.; Depauw, H.; Coudert, F.X.; Vrielinck, H.; Van Der Voort, P.; Leus, K. Mixed-metal metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 2535–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mahy, J.G.; Lambert, S.D. Adsorption and Photo(electro)catalysis for Micropollutant Degradation at the Outlet of Wastewater Treatment Plants: Bibliometric Analysis and Challenges to Implementation. Processes 2025, 13, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, P.; Li, K.; Zhao, S.; Chen, M.; Pan, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Zeolite Imidazole Frame-67 (ZIF-67) and Its Derivatives for Pollutant Removal in Water: A Review. Processes 2025, 13, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hankari, S.; Bousmina, M.; El Kadib, A. Biopolymer@ metal-organic framework hybrid materials: A critical survey. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2019, 106, 100579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Yan, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.C.; Jiang, H.L. Metal–organic framework-based hierarchically porous materials: Synthesis and applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 12278–12326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Lee, J.; Karakoti, A.; Bahadur, R.; Yi, J.; Zhao, D.; AlBahily, K.; Vinu, A. Emerging trends in porous materials for CO2 capture and conversion. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 4360–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Peng, L.; Bulut, S.; Queen, W.L. Recent advances of MOFs and MOF-derived materials in thermally driven organic transformations. Chem. A Eur. J. 2019, 25, 2161–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, Q.L.; Zou, R.; Xu, Q. Metal-organic frameworks for energy applications. Chem 2017, 2, 52–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zeb, A.; Xu, Z.; Sahar, S.; Zhou, J.E.; Lin, X.; Wu, Z.; Reddy, R.C.K.; Xiao, X.; Hu, L. Fe-based metal-organic frameworks and their derivatives for electrochemical energy conversion and storage. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 494, 215335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R.C.K.; Lin, J.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, C.; Lin, X.; Cai, Y.; Su, C.Y. Progress of nanostructured metal oxides derived from metal–organic frameworks as anode materials for lithium–ion batteries. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 420, 213434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Liang, T.; Shi, M.; Chen, H. Graphene-like two-dimensional materials. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 3766–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, A.; Cheng, H.M.; Enoki, T.; Gogotsi, Y.; Hurt, R.H.; Koratkar, N.; Kyotani, T.; Monthioux, M.; Park, C.R.; Tascon, J.M. All in the graphene family–A recommended nomenclature for two-dimensional carbon materials. Carbon 2013, 65, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, C. Review of chemical vapor deposition of graphene and related applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2329–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Alshammari, Y.; Majeed, S.A.; Al-Nasrallah, E. Chemical vapour deposition of graphene—Synthesis, characterisation, and applications: A review. Molecules 2020, 25, 3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Pang, J.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Sun, D.; Ibarlucea, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, D. Synthesis of wafer-scale graphene with chemical vapor deposition for electronic device applications. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2021, 6, 2000744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.A.; Bashir, S.; Ramesh, K.; Ramesh, S. A comprehensive review: Super hydrophobic graphene nanocomposite coatings for underwater and wet applications to enhance corrosion resistance. FlatChem 2022, 31, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnaiah, K.; Gurushankar, K.; Kannan, K.; Asadi, A.; Dinesh, S.; Thangamani, C. Magnetic nanoparticles for immobilization of enzyme and their applications—A review. Int. J. Pharm. Res. 2020, 12, 2689–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Garaj, S.; Bianco, A.; Ménard-Moyon, C. Controlling covalent chemistry on graphene oxide. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2022, 4, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.K.; Singh, P.K.; Sharma, K. Electrochemical synthesis and characterization of thermally reduced graphene oxide: Influence of thermal annealing on microstructural features. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 103950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, P.A. Heteroatom Codoped Graphene: The Importance of Nitrogen. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 45935–45961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Shin, W.I.; Chen, H.; Lee, S.M.; Manickam, S.; Hanson, S.; Zhao, H.; Lester, E.; Wu, T.; Pang, C.H. A recent trend: Application of graphene in catalysis. Carbon Lett. 2021, 31, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.N.U.Z.; Qureshi, W.A.; Ali, R.N.; Shaosheng, R.; Naveed, A.; Ali, A.; Yaseen, M.; Liu, Q.; Yang, J. Contemporary advances in photocatalytic CO2 reduction using single-atom catalysts supported on carbon-based materials. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 323, 103068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardyanti, N.; Susanto, H.; Kusuma, F.A.; Budihardjo, M.A. A Bibliometric Review of Adsorption Treatment with an Adsorbent for Wastewater. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Zang, M.; Cheng, Y.; Qi, H. Graphene-based photocatalysts for degradation of organic pollution. Chemosphere 2023, 341, 140038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, B.; Khalil, A.M.; Zhang, S.; Memon, F.A. Investigating the Potential of Greener-Porous Graphene for the Treatment of Organic Pollutants in Wastewater. C 2023, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrahal, M.; Belouatek, A. Application of synthesized graphene in the treatment of wastewater. Desalination Water Treat. 2023, 306, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Gu, Y.; Tang, P.; Liu, L. Electrochemical Sensor Based on Magnetic Molecularly Imprinted Polymer and Graphene-UiO-66 Composite Modified Screen-printed Electrode for Cannabidiol Detection. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2022, 17, 220562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silveira, P.H.P.M.; Ribeiro, M.P.; Silva, T.T.; Lima, A.M.; Lemos, M.F.; Oliveira, A.G.B.A.M.; Nascimento, L.F.C.; Gomes, A.V.; Monteiro, S.N. Effect of Alkaline Treatment and Graphene Oxide Coating on Thermal and Chemical Properties of Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Fibers. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 12168–12181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.A.; Arain, M.B.; Soylak, M. Nanomaterials-based solid phase extraction and solid phase microextraction for heavy metals food toxicity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 145, 111704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, M.; Hu, F.; Wu, J.; Xu, L.; Xu, G.; Jian, Y.; Peng, X. Controllable construction of hierarchical TiO2 supported on hollow rGO/P-HC heterostructure for highly efficient photocatalysis. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 598, 124831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokoena, D.R.; George, B.P.; Abrahamse, H. Enhancing breast cancer treatment using a combination of cannabidiol and gold nanoparticles for photodynamic therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, L.; Amariei, G.; Ezugwu, C.I.; Faraldos, M.; Bahamonde, A.; Mosquera, M.E.G.; Rosal, R. Zirconium-based Metal-Organic Frameworks for highly efficient solar light-driven photoelectrocatalytic disinfection. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 285, 120351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Wang, K.Y.; Welton, C.; Feng, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Kang, Z.; Zhou, H.C.; Wang, R. Aluminum metal–organic frameworks: From structures to applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 489, 215175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Frick, J.J.; Davey, A.K.; Dods, M.N.; Carraro, C.; Senesky, D.G.; Maboudian, R. Synthesis and characterization of UiO-66-NH2 incorporated graphene aerogel composites and their utilization for absorption of organic liquids. Carbon 2023, 201, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nangare, S.; Patil, S.; Patil, A.; Deshmukh, P.; Patil, P. Bovine serum albumin-derived poly-l-glutamic acid-functionalized graphene quantum dots embedded UiO-66-NH2 MOFs as a fluorescence ‘On-Off-On’magic gate for para-aminohippuric acid sensing. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2023, 438, 114532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, N.; Wang, Y.; Nunna, B.B.; Lee, E.S. N-Doped Graphene (NG)/MOF (ZIF-8)-Based/Derived Materials for Electrochemical Energy Applications: Synthesis, Characteristics, and Functionality. Batteries 2024, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczęśniak, B.; Borysiuk, S.; Choma, J.; Jaroniec, M. Mechanochemical synthesis of highly porous materials. Mater. Horiz. 2020, 7, 1457–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Tang, Y.; Huang, X.; Pang, H. Recent advances and challenges of metal–organic framework/graphene-based composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 230, 109532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, C.; Seredych, M.; Bandosz, T.J. Revisiting the chemistry of graphite oxides and its effect on ammonia adsorption. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 9176–9185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, C.; Bandosz, T.J. MOF–graphite oxide composites: Combining the uniqueness of graphene layers and metal–organic frameworks. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 4753–4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Luo, D.; Wu, K.; Zhou, X.P. Metal–organic frameworks with the gyroid surface: Structures and applications. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 4757–4764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadidi, M.; Rostamabadi, H.; Moreno, A.; Jafari, S.M. Nanoencapsulation of essential oils from industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) by-products into alfalfa protein nanoparticles. Food Chem. 2022, 386, 132765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; You, Z.; Hou, C.; Liu, L.; Xiao, A. An electrochemical sensor based on amino magnetic nanoparticle-decorated graphene for detection of cannabidiol. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkson, B.J. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for materials characterization. In Materials Characterization Using Nondestructive Evaluation (NDE) Methods; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 17–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mkilima, T.; Zharkenov, Y.; Utepbergenova, L.; Abduova, A.; Sarypbekova, N.; Smagulova, E.; Abdukalikova, G.; Kamidulla, F.; Zhumadilov, I. Harnessing graphene oxide-enhanced composite metal-organic frameworks for efficient wastewater treatment. Water Cycle 2024, 5, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkilima, T.; Zharkenov, Y.; Utepbergenova, L.; Smagulova, E.; Fazylov, K.; Zhumadilov, I.; Kirgizbayeva, K.; Baketova, A.; Abdukalikova, G. Carwash wastewater treatment through the synergistic efficiency of microbial fuel cells and metal-organic frameworks with graphene oxide integration. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9, 100582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, J.R.; de Sousa Pereira, M.V.; Ribeiro, I.S.; de Araújo Andrade, T.; de Carvalho, J.P.; de Tarso Garcia, P.; Junior, C.A.L. Multifunctional and eco-friendly nanohybrid materials as a green strategy for analytical and bioanalytical applications: Advances, potential and challenges. Microchem. J. 2023, 194, 109331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sakkaf, M.K.; Basfer, I.; Iddrisu, M.; Bahadi, S.A.; Nasser, M.S.; Abussaud, B.; Drmosh, Q.A.; Onaizi, S.A. An Up-to-Date Review on the Remediation of Dyes and Phenolic Compounds from Wastewaters Using Enzymes Immobilized on Emerging and Nanostructured Materials: Promises and Challenges. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Pavlish, J. Novel dry cooling technology for power plants. Conc. Sol. Power Program Rev. 2013, 2013, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Kausar, A.; Ahmad, I. Graphene-MOF hybrids in high-tech energy devices—present and future advances. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 5, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Z.; Feng, K.; Tang, B.; Wu, P. Surface decoration of amino-functionalized metal–organic framework/graphene oxide composite onto polydopamine-coated membrane substrate for highly efficient heavy metal removal. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 2594–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Liu, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Li, R.; Liu, L.; Wang, J. Interfacial growth of a metal–organic framework (UiO-66) on functionalized graphene oxide (GO) as a suitable seawater adsorbent for extraction of uranium (VI). J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 17933–17942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Ge, M.; Huang, J.; Lai, Y.; Lin, C.; Zhang, K.; Meng, K.; Tang, Y. Constructing multifunctional MOF@ rGO hydro-/aerogels by the self-assembly process for customized water remediation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 11873–11881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Liang, J.; Dong, L.; Chai, J.; Zhao, N.; Ullah, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, D.; Imtiaz, S.; Shan, G.; et al. Self-assembly of 2D-metal–organic framework/graphene oxide membranes as highly efficient adsorbents for the removal of Cs+ from aqueous solutions. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 40813–40822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, M.S.; Subramaniyan, V.; Bhattacharya, J.; Parthiban, C.; Chand, S.; Singh, N.P. A GO-CS@ MOF [Zn (BDC)(DMF)] material for the adsorption of chromium (VI) ions from aqueous solution. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 152, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, T.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Aggarwal, S. Removal of arsenic (III) from aqueous solution using metal organic framework-graphene oxide nanocomposite. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantaray, P.K.; Madras, G.; Bose, S. Water remediation aided by a graphene-oxide-anchored metal organic framework through pore-and charge-based sieving of ions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 7, 1580–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantaray, P.K.; Baloda, S.; Madras, G.; Bose, S. Nanodelivery in scrolls-based nanocarriers: Efficient constructs for sustainable scavenging of heavy metal ions and inactivate bacteria. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 18775–18784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, N.; Zheng, X.; Li, Q.; Gong, C.; Ou, H.; Li, Z. Construction of lanthanum modified MOFs graphene oxide composite membrane for high selective phosphorus recovery and water purification. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 565, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, D.; Wu, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C. Magnetic metal organic frameworks/graphene oxide adsorbent for the removal of U(VI) from aqueous solution. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2020, 162, 109160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, T.A.; Le, G.H.; Vu, H.T.; Nguyen, K.T.; Quan, T.T.; Nguyen, Q.K.; Tran, H.T.; Dang, P.T.; Vu, L.D.; Lee, G.D. Highly photocatalytic activity of novel Fe-MIL-88B/GO nanocomposite in the degradation of reactive dye from aqueous solution. Mater. Res. Express 2017, 4, 035038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yuan, X.; Zhong, H.; Wang, H.; Jiang, L.; Zeng, G.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y. Highly efficient adsorption of Congo red in single and binary water with cationic dyes by reduced graphene oxide decorated NH2-MIL-68 (Al). J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 247, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Guo, X.; Ying, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhong, C. Composite ultrafiltration membrane tailored by MOF@GO with highly improved water purification performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 313, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, J.; Vossoughi, M.; Mahmoodi, N.M.; Alemzadeh, I. Synthesis of metal-organic framework hybrid nanocomposites based on GO and CNT with high adsorption capacity for dye removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 326, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Chen, D.; Wei, F.; Chen, N.; Liang, Z.; Luo, Y. Removal of Congo red dye from aqueous solution with nickel-based metal-organic framework/graphene oxide composites prepared by ultrasonic wave-assisted ball milling. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 39, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanhaei, M.; Mahjoub, A.R.; Safarifard, V. Sonochemical synthesis of amide-functionalized metal-organic framework/graphene oxide nanocomposite for the adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solution. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018, 41, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Chen, D.; Wei, F.; Chen, N.; Liang, Z.; Luo, Y. Synthesis of graphene oxide/metal–organic frameworks hybrid materials for enhanced removal of Methylene blue in acidic and alkaline solutions. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 93, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shi, Z.; Zhu, H.; Hong, W.; Xie, F.; Sun, K. Adsorption of azo dyes from aqueous solution by the hybrid MOFs/GO. Water Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 1728–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Wang, J.; Huang, F.; Xue, Y.; Cai, N.; Liu, J.; Chen, W.; Yu, F. Synergistic effect of adsorption coupled with catalysis based on graphene-supported MOF hybrid aerogel for promoted removal of dyes. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 34552–34559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenhaut, T.; Hermans, S.; Filinchuk, Y. Green synthesis of a large series of bimetallic MIL-100 (Fe,M) MOFs. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 3847–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasopoulou, A.; Furukawa, H.; Barnett, B.R.; Jiang, H.Z.; Long, J.R.; Breunig, H.M. Technoeconomic analysis of metal–organic frameworks for bulk hydrogen transportation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 1083–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, H.; Cordova, K.E.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. The chemistry and applications of metal-organic frameworks. Science 2013, 341, 1230444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argyropoulos, G.; Zampetoglou, K.; Spachos, T.; Soupilas, A.; Papadakis, N.; Grammatikopoulos, G. Pilot-Scale Study of Advanced Wastewater Treatment Processes by EYATH SA. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Georgios-Argyropoulos/publication/262818454_Pilot-scale_study_of_advanced_wastewater_treatment_processes_by_EYATH_SA/links/54273f440cf2e4ce940a2e5e/Pilot-scale-study-of-advanced-wastewater-treatment-processes-by-EYATH-SA.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Seabra, A.B.; Paula, A.J.; de Lima, R.; Alves, O.L.; Durán, N. Nanotoxicity of Graphene and Graphene Oxide. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2014, 27, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arsenov, D.; Beljin, J.; Jović, D.; Maletić, S.; Borišev, M.; Borišev, I. Nanomaterials as endorsed environmental remediation tools for the next generation: Eco-safety and sustainability. J. Geochem. Explor. 2023, 253, 107283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhang, P.; Sharma, V.K.; Ma, X.; Zhou, H.C. Metal-organic frameworks for environmental applications. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2021, 2, 100348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Synthesis Method | Main Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanochemical (solid-state) | Grinding of MOF precursors with graphene or its derivatives using mortar, pestle, or ball-milling | Simple, solvent-free, fast, and environmentally friendly; easily scalable | Often yields lower crystallinity and weaker MOF–graphene bonding; limited control of morphology | Energy storage devices, gas adsorption, simple adsorbents |

| Solvothermal/ Hydrothermal | Reaction of metal salts and organic linkers with dispersed graphene materials in solvent under elevated temperature and pressure | Produces highly crystalline structures with strong interfacial bonding; tunable porosity and functionalization | Solvent-intensive; time-consuming; potential agglomeration if poorly dispersed | Adsorption of dyes and pharmaceuticals; photocatalysis; sensing |

| In situ/One-pot growth | Simultaneous formation of MOF on graphene surface through coordination between metal ions and oxygen groups of graphene oxide | Strong chemical interface; uniform MOF growth; good reproducibility | --------- | Catalysis, pollutant degradation, and electrochemical applications |

| Removed Pollutant | G@MOFS Composite | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cu (II) | IRMOF-3/GO | [97] |

| U(VI) (ppb and ppm level removal) | GO-COOH/UiO-66 | [98] |

| Pb (II), Cd (II) | ZIF-8/rGA | [99] |

| Cs+ (192.14 mg·g−1) | GO/2D-Co-MOF-60 membrane | [100] |

| Cr (VI) | GO-CS@MOF [Zn (BDC)(DMF)] | [101] |

| As (III) | MIL-53(Al)-GO | [102] |

| Na (I), Ca (II), Mg (II) | P+GO-anchored HKUST-1 | [103] |

| As (III), Pb (II) | dpGNS-encapsulated DMOF-1 | [104] |

| Total phosphorus | La-mof-1 GO membrane | [105] |

| U (VI) | Fe3O4@HKUST-1/GO | [106] |

| Methylene blue | ZIF-8/rGA | [99] |

| Reactive red dye (RR195) | Fe-MIL-88B/GO | [107] |

| Congo red | NH2-MIL-68(Al)/RGO | [108] |

| Methyl orange, direct red 80 | UiO-66@GO/PES membrane | [109] |

| Malachite green | ZIF-8@GO | [110] |

| Congo Red | Ni BTC@GO | [111] |

| Methylene blue | GO-TMU-23c | [112] |

| Methylene blue | 6% GO/Ni-BTC | [113] |

| Azo dyes: amaranth, sunset yellow, carmine | MIL-101/GO | [114] |

| Methylene blue | MIL-100(Fe)/graphene hybrid aerogel (MG-HA) | [115] |

| G@MOFS Composite | qmax (mg·g−1) | Removal Efficiency (%) | pH | Contact Time (min) | Recyclability (Cycles) | Regeneration Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZIF-8/rGA | 332 | 99 | 5.5 | 60 | 5 | Ethanol wash | [99] |

| GO-COOH/UiO-66 | 250 | 95 | 6.0 | 45 | 5 | pH adjustment | [98] |

| Fe-MIL-88B/GO | 200 | 95 | 7.0 | 120 | 4 | Thermal treatment | [107] |

| MIL-53(Al)-GO | 150 | 98 | 5.0 | 90 | 3 | Acid/base cycling | [102] |

| MIL-100(Fe)/Graphene Aerogel | 450 | 97 | 6.5 | 30 | 5 | Ultraviolet irradiation | [115] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

El Hammoudani, Y.; Achoukhi, I.; Haboubi, K.; El Youssfi, A.; Benaissa, C.; Bourjila, A.; Touzani, A.; El Ahmadi, K.; El Allaoui, H.; El Kasmi, A.; et al. Graphene-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks for Advanced Wastewater Treatment: A Review of Synthesis, Characterization, and Micropollutant Removal. Processes 2026, 14, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010117

El Hammoudani Y, Achoukhi I, Haboubi K, El Youssfi A, Benaissa C, Bourjila A, Touzani A, El Ahmadi K, El Allaoui H, El Kasmi A, et al. Graphene-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks for Advanced Wastewater Treatment: A Review of Synthesis, Characterization, and Micropollutant Removal. Processes. 2026; 14(1):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010117

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl Hammoudani, Yahya, Iliass Achoukhi, Khadija Haboubi, Abdellah El Youssfi, Chaimae Benaissa, Abdelhak Bourjila, Abdelaziz Touzani, Kawthar El Ahmadi, Hasnae El Allaoui, Achraf El Kasmi, and et al. 2026. "Graphene-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks for Advanced Wastewater Treatment: A Review of Synthesis, Characterization, and Micropollutant Removal" Processes 14, no. 1: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010117

APA StyleEl Hammoudani, Y., Achoukhi, I., Haboubi, K., El Youssfi, A., Benaissa, C., Bourjila, A., Touzani, A., El Ahmadi, K., El Allaoui, H., El Kasmi, A., & Dimane, F. (2026). Graphene-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks for Advanced Wastewater Treatment: A Review of Synthesis, Characterization, and Micropollutant Removal. Processes, 14(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010117