Comprehensive Evaluation of Directional Hydraulic Fracturing for Roof Pressure Relief and Disaster Prevention Based on Integrated Multi-Parameter Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting and Mining Conditions

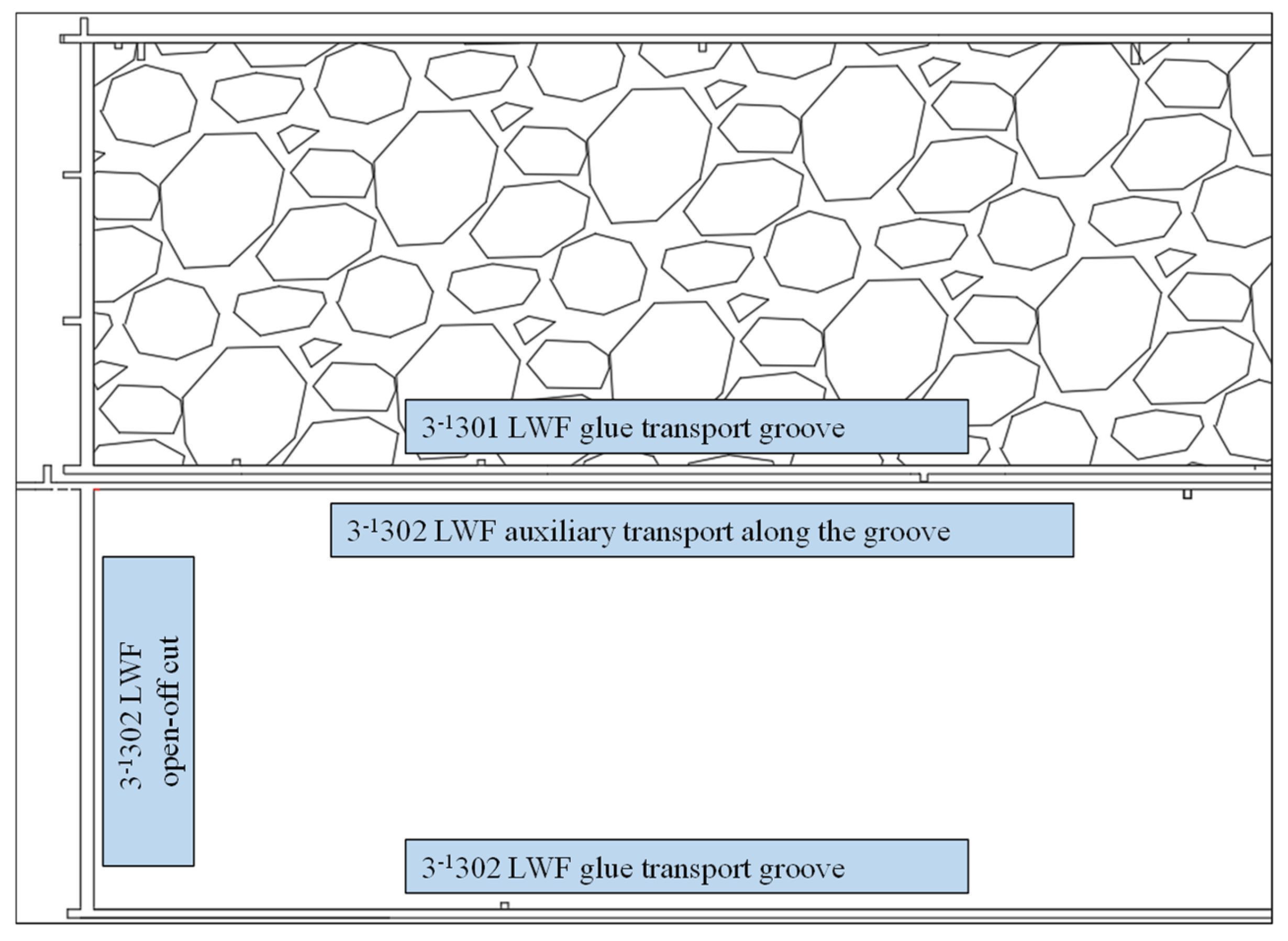

2.1. Layout of 3-1302 Longwall Face

2.2. Engineering Geological Condition

3. Directional Long Borehole Hydraulic Fracturing Roof Pressure Relief Scheme

3.1. Hydraulic Fracturing Pressure Relief Mechanism

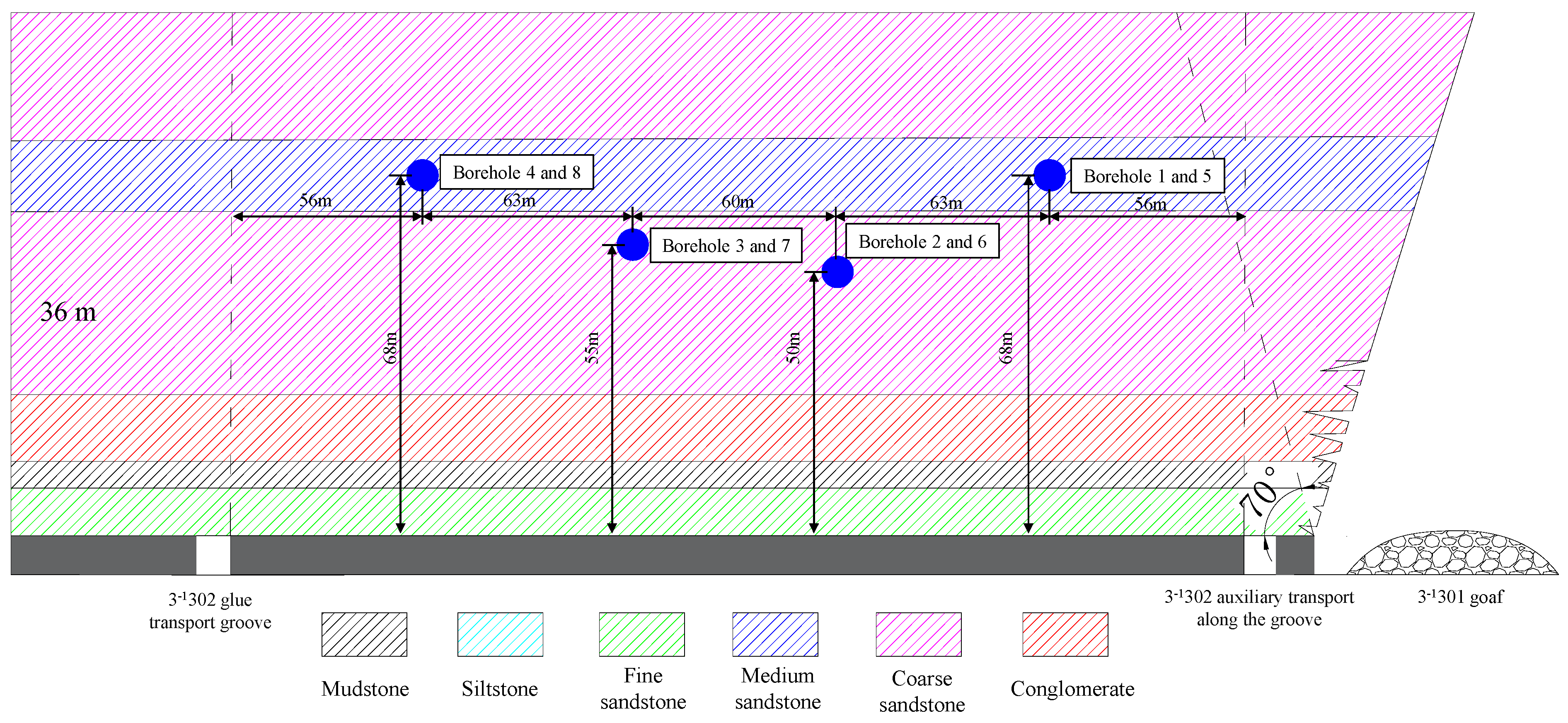

3.2. Hydraulic Fracturing Pressure Relief Strata Selection

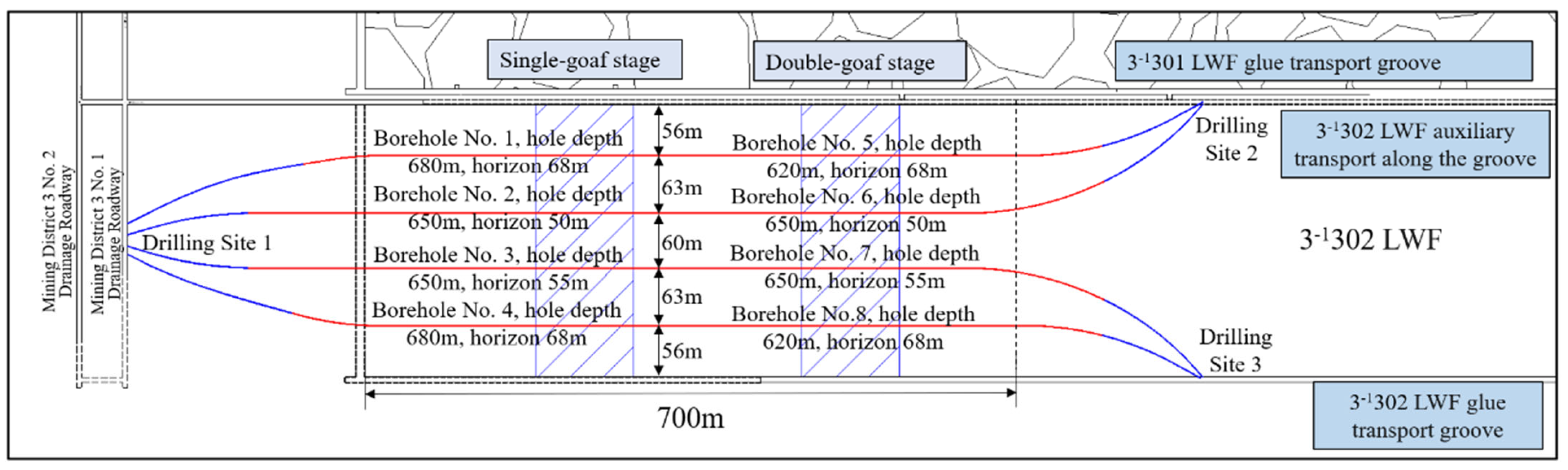

3.3. Hydraulic Fracturing Roof Pressure Relief Design

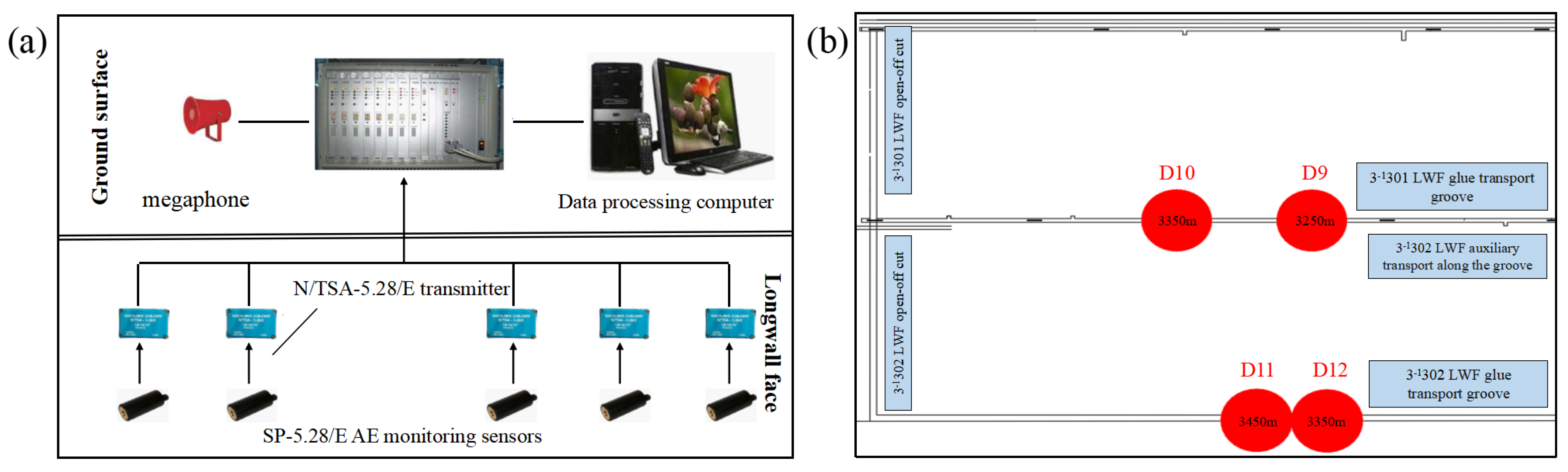

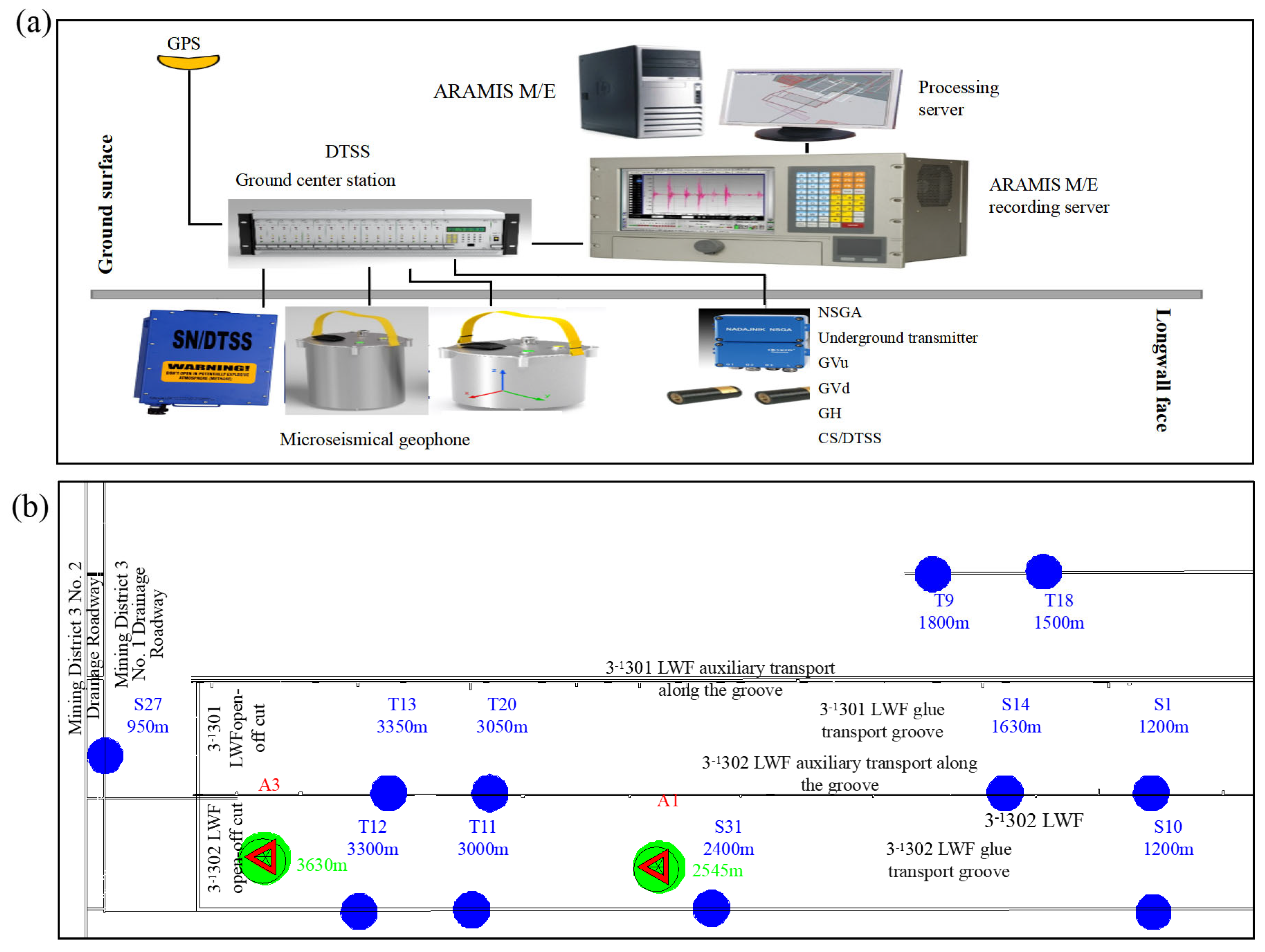

4. Monitoring Methods

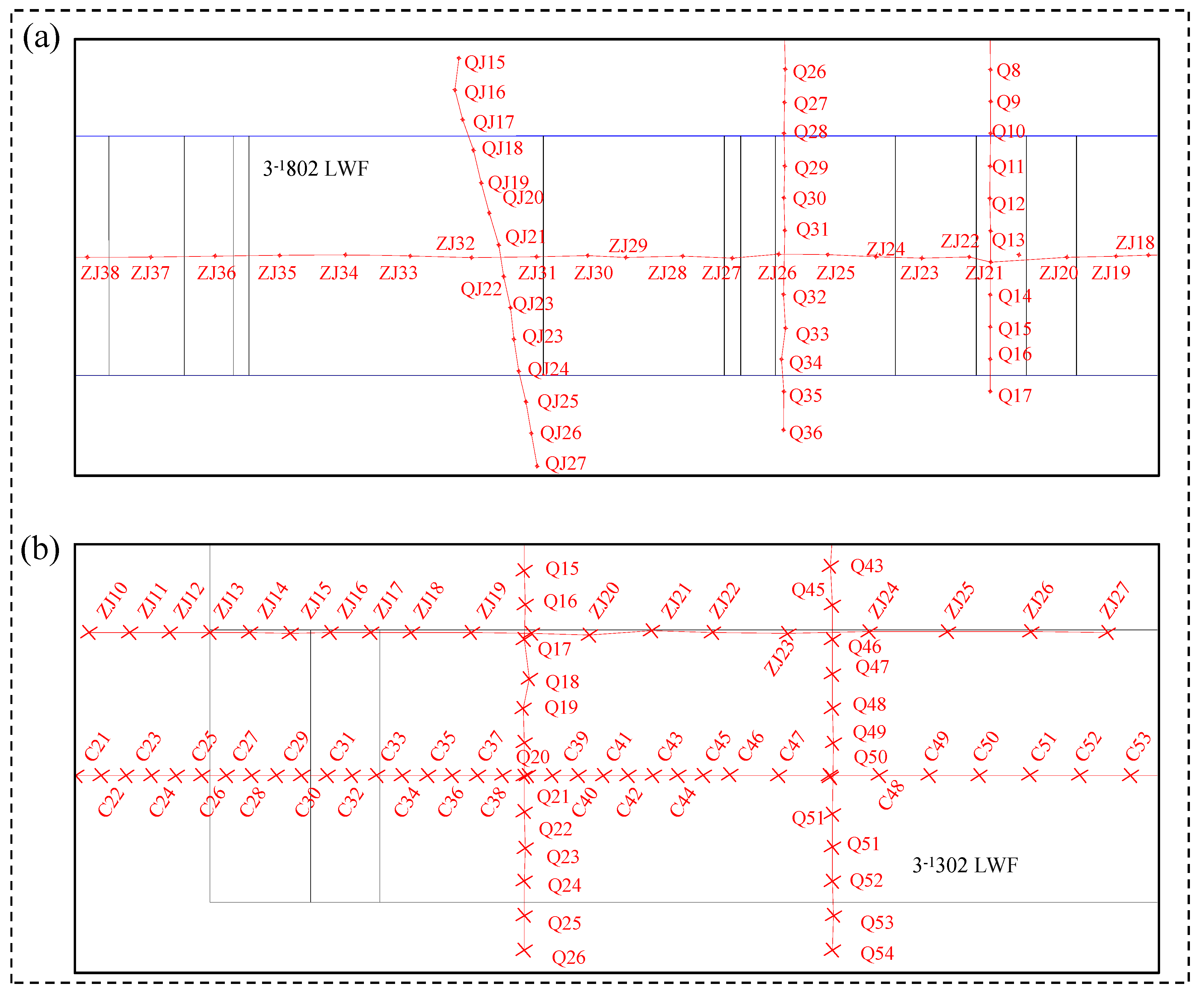

4.1. The Overview of the 3-1802 LWF

4.2. The Layout of the Monitoring System

5. Results and Discussion

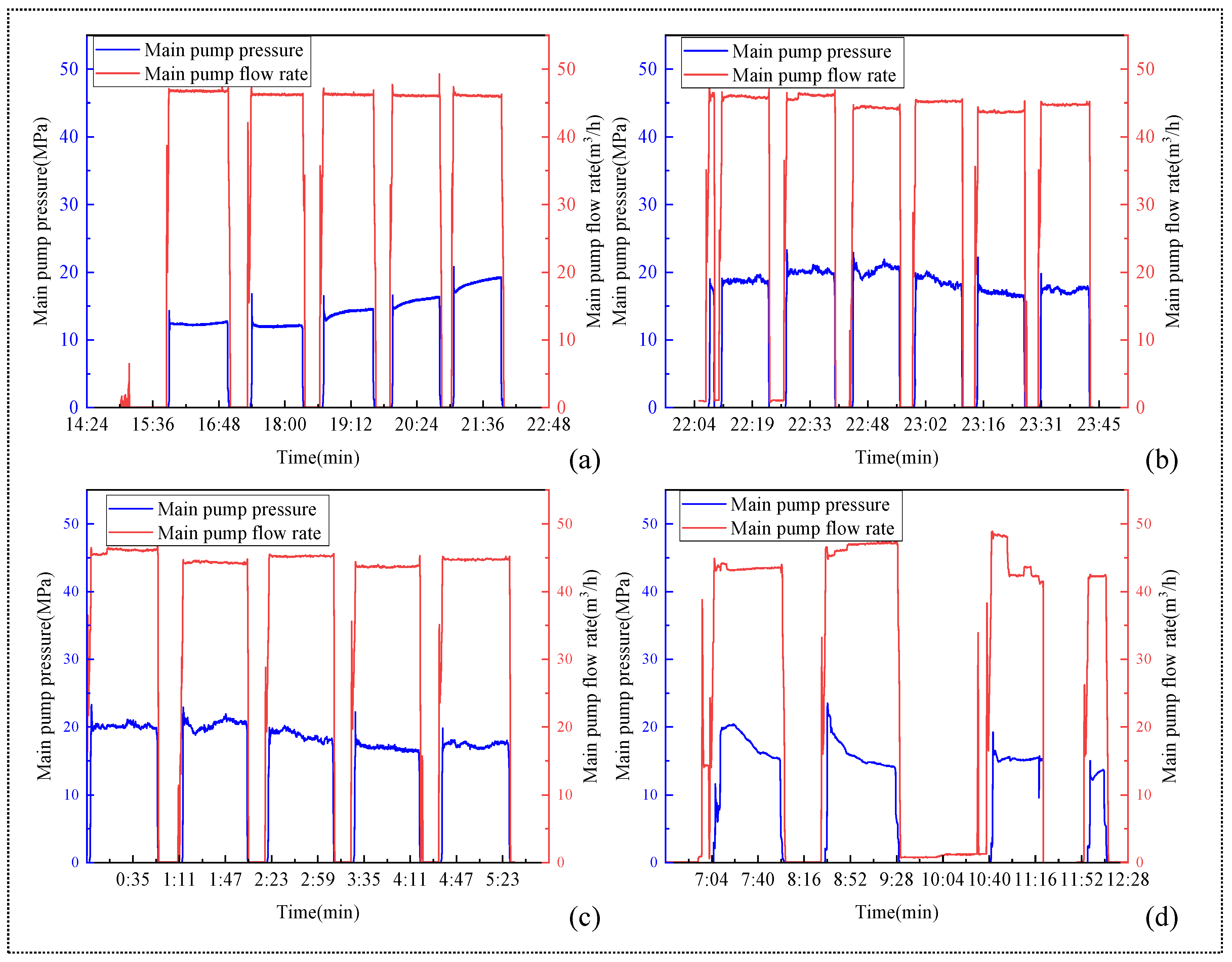

5.1. Hydraulic Fracturing Construction Record Curve

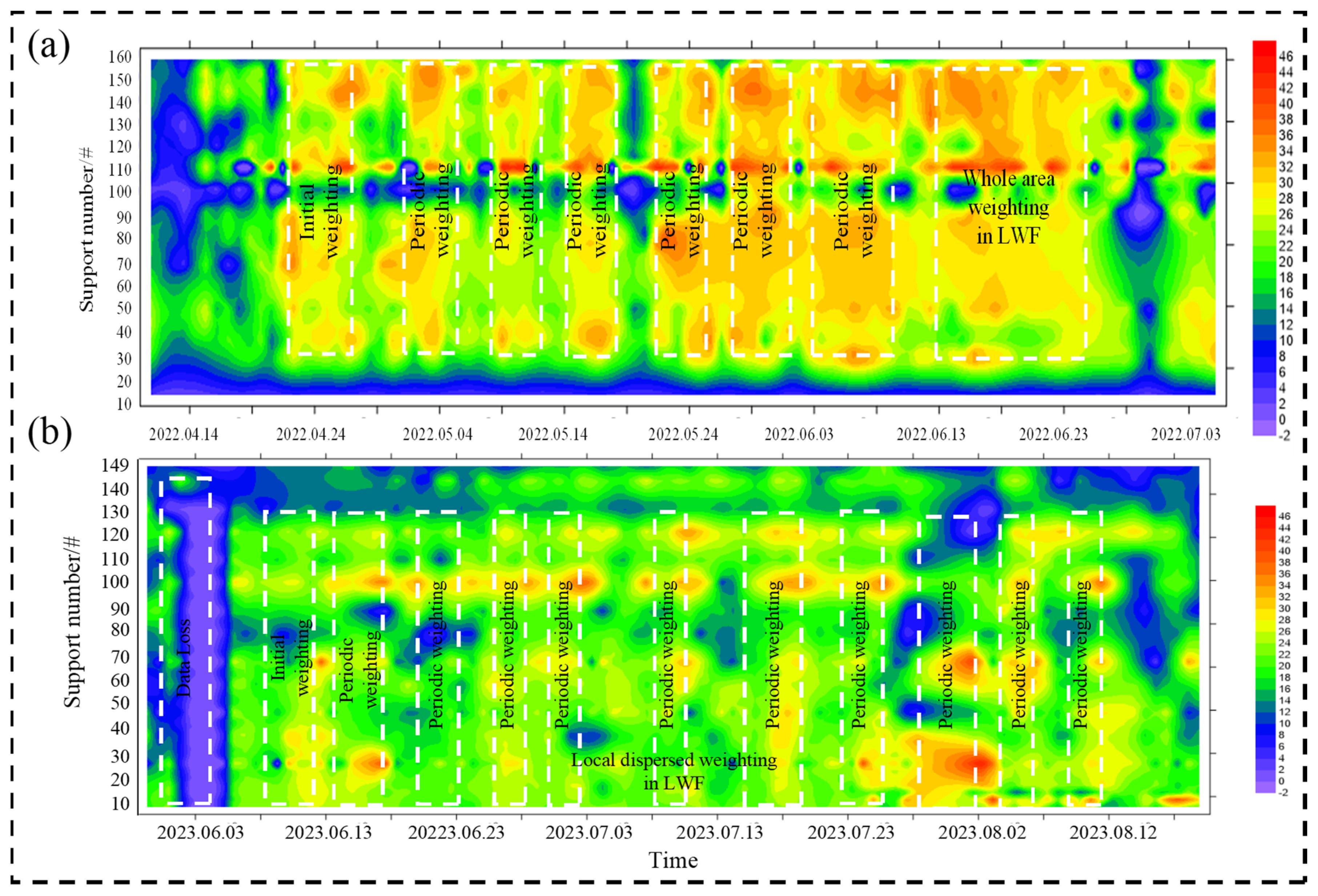

5.2. Evolution Characteristics of Working Resistance of Hydraulic Supports in LWF

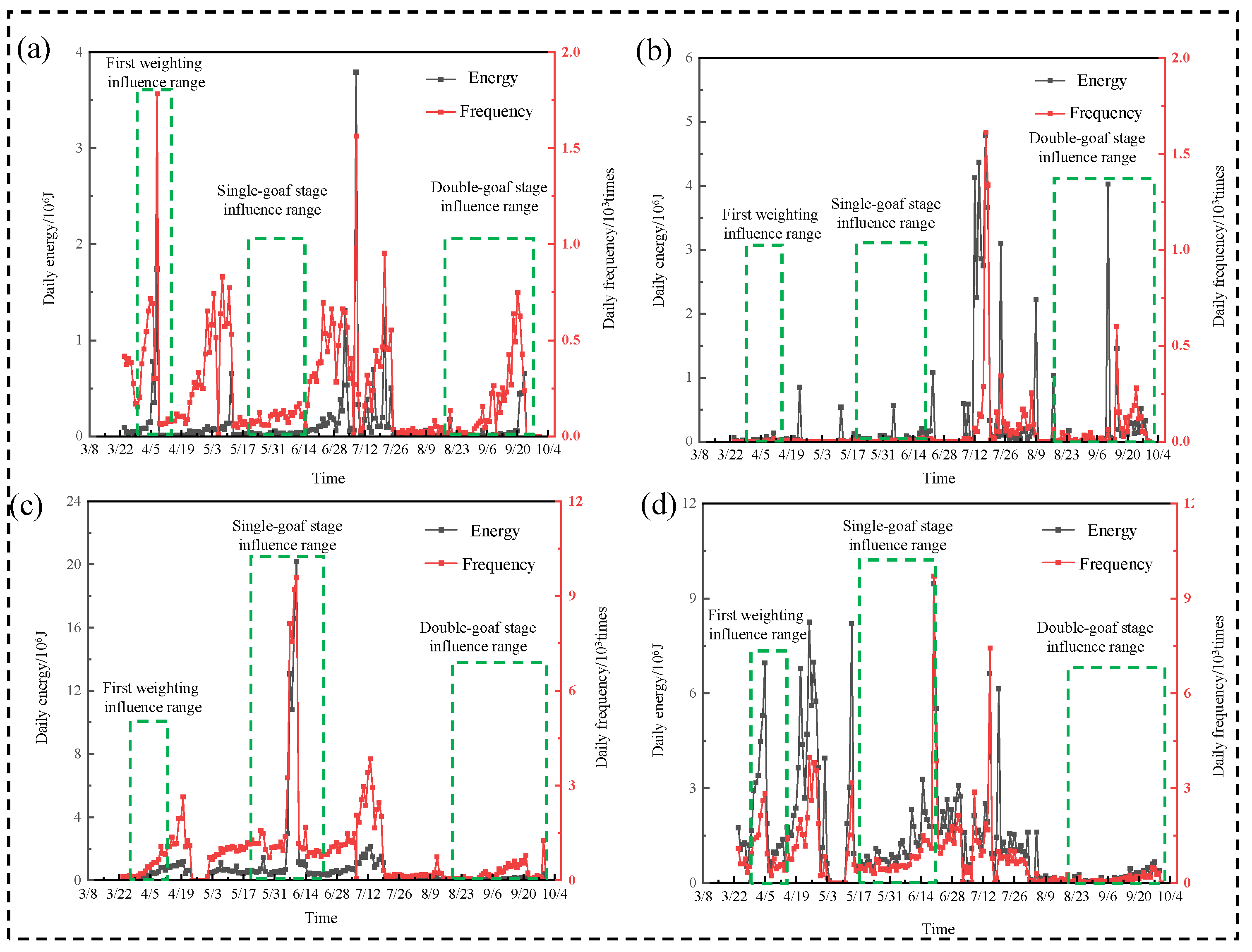

5.3. AE Monitoring Results Analysis

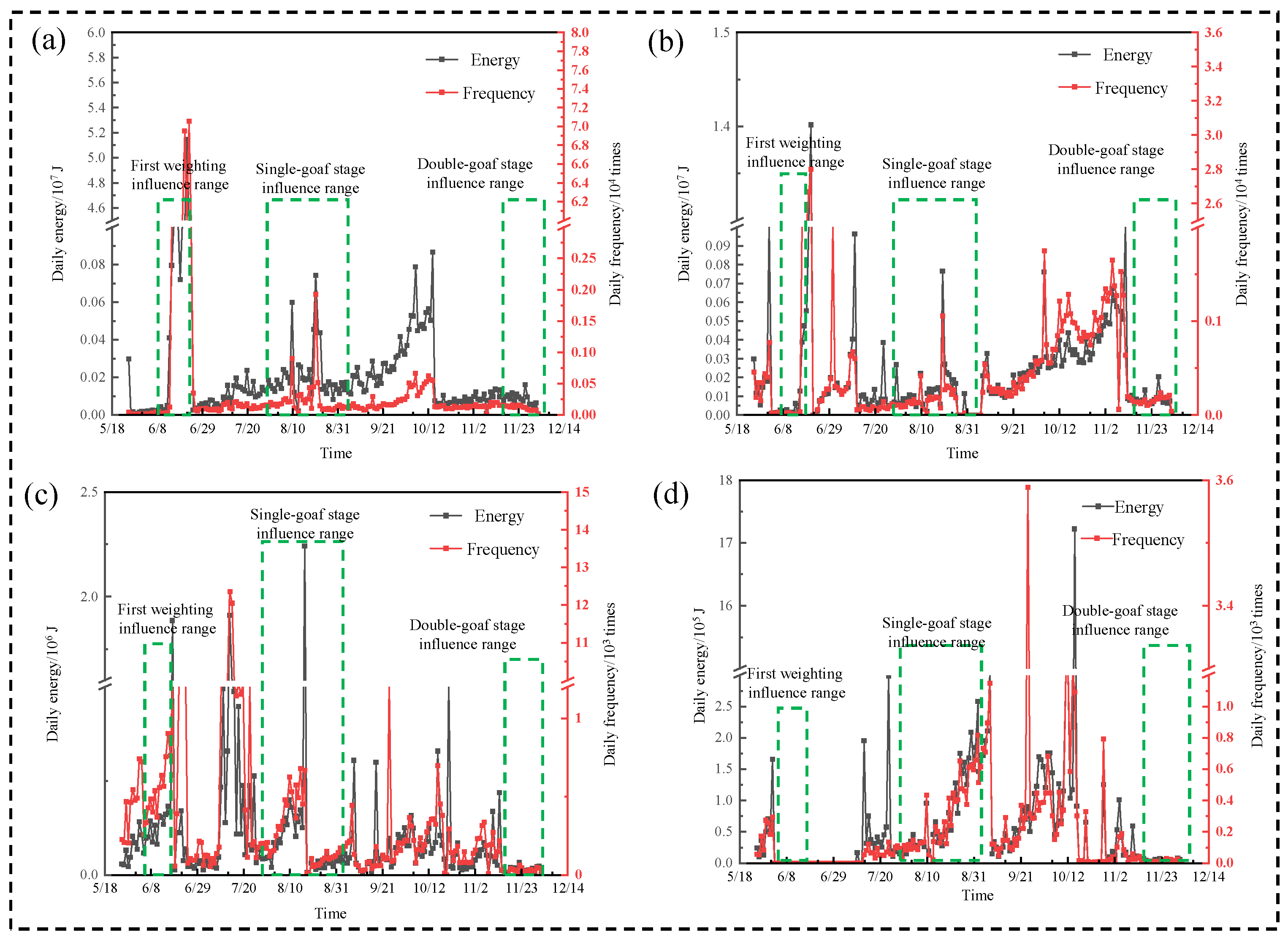

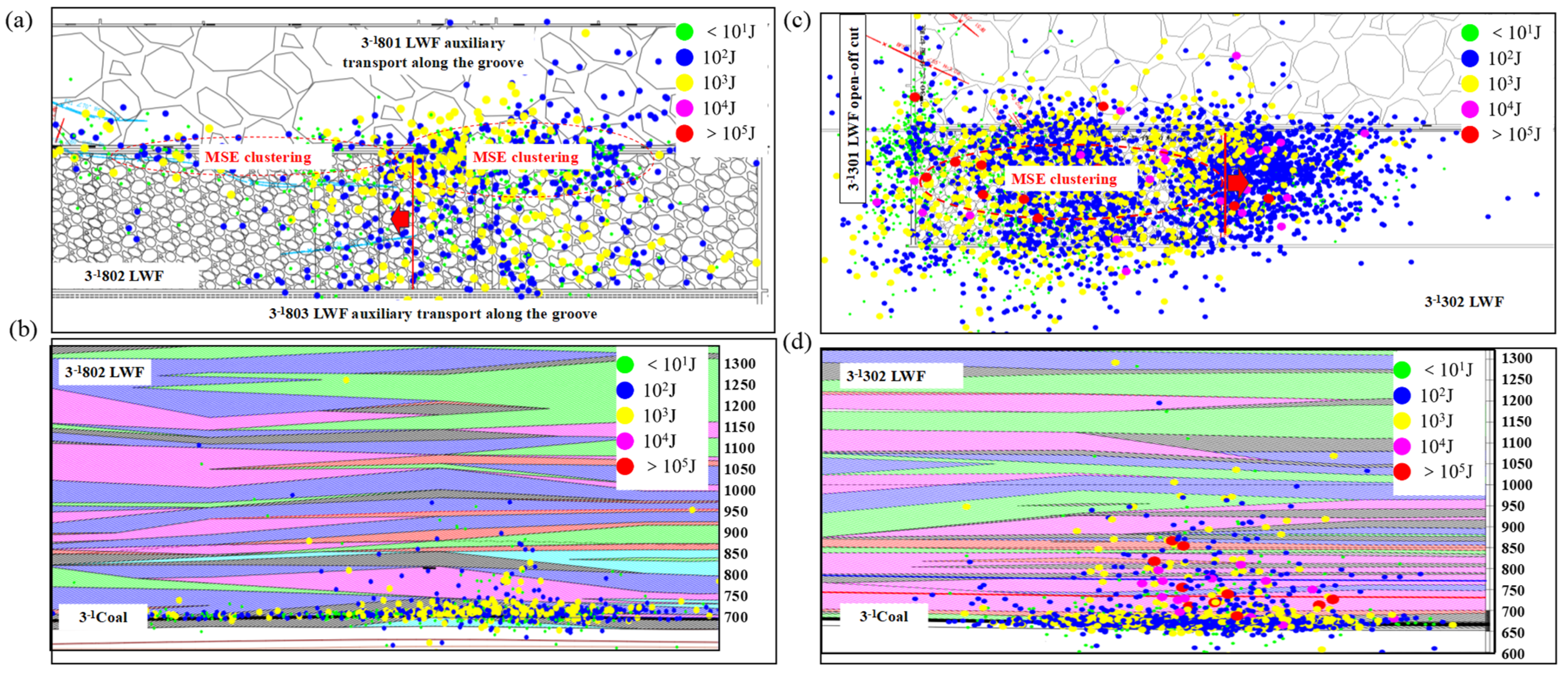

5.4. MS Monitoring Results Analysis

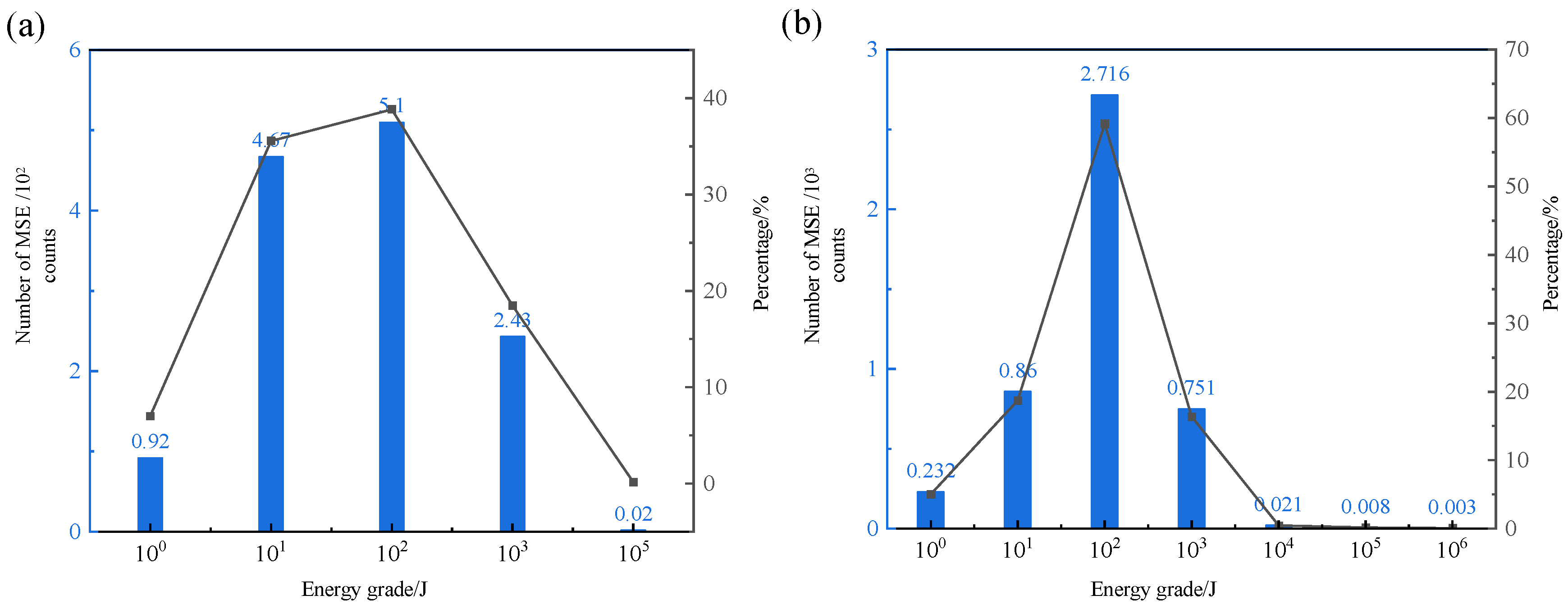

5.4.1. Comparative Analysis of the Number of MSE

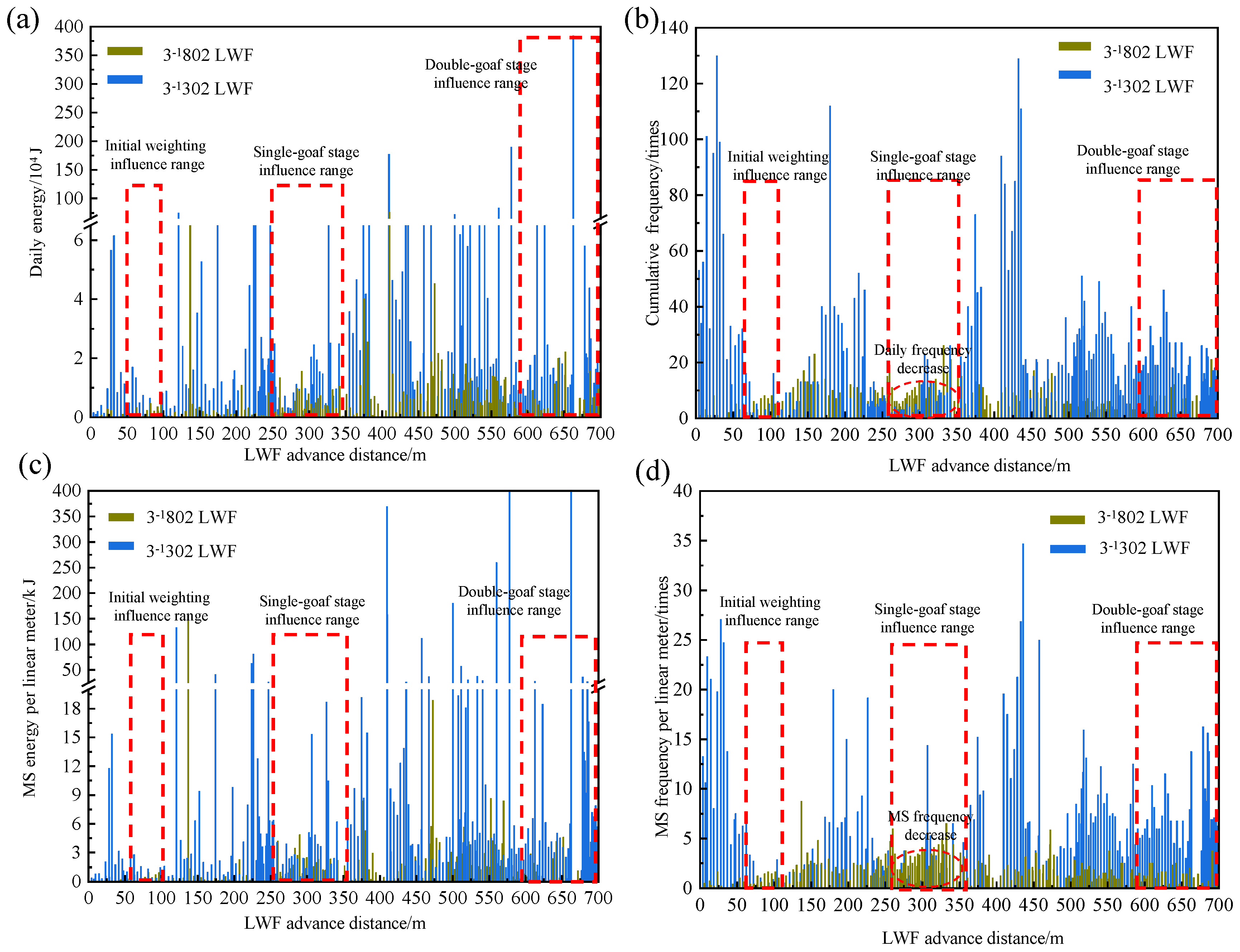

5.4.2. Evolution Characteristics of Roof Cracks Based on MS Daily Energy and Frequency

5.4.3. The Spatial Distribution Pattern of MS Activity Under the Influence of HF

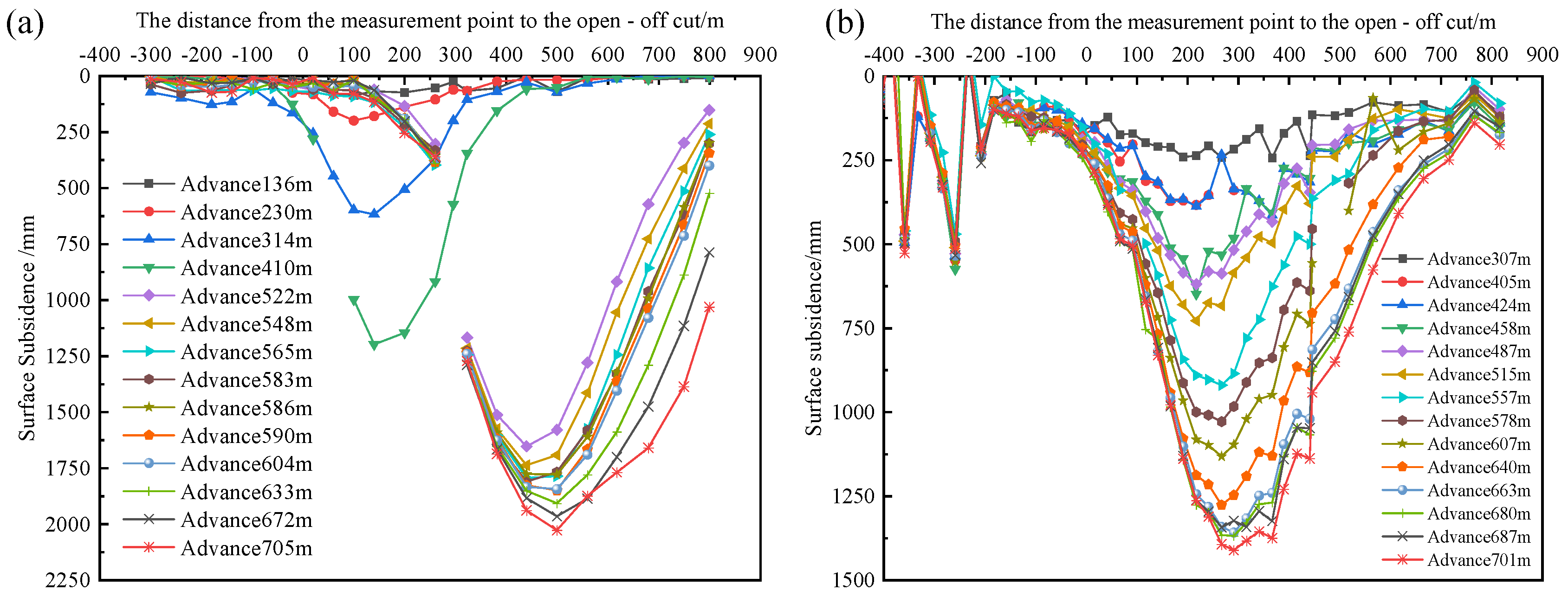

5.5. Evolution Characteristics of SFS

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Establishment of a Multi-Dimensional Evaluation System: A three-dimensional chain monitoring system was successfully established, integrating support pressure response, spatiotemporal evolution of microseismic events, and surface subsidence laws. This system enables a comprehensive and quantitative assessment of the HFRPRT effectiveness, moving beyond single-parameter evaluations to provide a holistic view of the roof behavior after fracturing.

- (2)

- Significant Weakening of Thick-Hard Overlying Strata and Alleviation of Dynamic Pressure: The application of directional hydraulic fracturing successfully induced large-scale weakening of the THOS. This intervention transformed the overburden stress transfer mechanism from a rigid, large-scale cantilever structure to a more flexible, segmented one. Consequently, the periodic weighting interval at the 3-1302 LWF was reduced to approximately 12 m (a 25% reduction compared to the non-fractured 3-1802 LWF), the influencing range of weighting was shortened to about 15 m (25% reduction), and the peak weighting intensity was lowered to around 32 MPa (21.95% reduction). This confirms that HFRPRT effectively mitigates the intensity of mining-induced dynamic pressure.

- (3)

- Promotion of Micro-Fracturing and Prevention of Energy Accumulation: The analysis of Acoustic Emission (AE) and Microseismic (MS) data provides critical insights into the fracturing mechanism. Following HFRPRT, the daily AE energy and event count increased dramatically by 154% and 636%, respectively. This signifies that hydraulic fracturing actively promoted the propagation of internal micro-fractures within the THOS before large-scale mining-induced stresses occurred. The MS monitoring further revealed a shift in the energy distribution pattern, with lower-energy second-order level events becoming predominant (59.16%), while the proportion of high-energy events (above fourth-order) was minimal (0.46%). This indicates a transition from catastrophic, high-energy releases to frequent, low-energy ruptures, substantially reducing the risk of dynamic hazards like rockbursts.

- (4)

- Alteration of Overburden Failure Patterns and Mitigation of Surface Subsidence: The spatial distribution of MSE demonstrated that the fracturing treatment significantly enhanced the vertical extent of rock failure, with events propagating up to 300 m above the coal seam. This ensured the timely caving of higher-level THOS, facilitating the release of high elastic energy in a controlled manner. As a result, the load-bearing capacity of the pressure arch was altered, leading to a more gradual overburden failure process. This was directly evidenced by the mitigation of surface subsidence, where the maximum SFS at the 3-1302 LWF was only 69.58% of that observed at the 3-1802 LWF for the same advance distance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deng, Q.; Zhao, F.; Li, H.; Yin, J.; Zhang, T.; Wei, J. Technology and practice of the roof-caving of hydraulic fracturing in a fully mechanized caving face. Therm. Sci. 2021, 25, 2117–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Li, Q. Collaborative movement characteristics of overlying rock and loose layer based on block–particle discrete-element simulation method. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2025, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Jiang, F.; Dou, L.; Ju, Y. State of the art review on mechanism and prevention of coal bumps in China. J. China Coal Soc. 2014, 39, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; He, J.; Cao, A.Y.; Gong, S.Y.; Cai, W. Rock burst prevention methods based on theory of dynamic and static combined load induced in coal mine. J. China Coal Soc. 2015, 40, 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, E. Rockburst mechanism in coal rock with structural surface and the microseismic (MS) and electromagnetic radiation (EMR) response. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 124, 105396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, E.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Song, D.; Qiu, L. Rock burst monitoring by integrated microseismic and electromagnetic radiation methods. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2016, 49, 4393–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Han, L.; Wu, K.; Lu, L.; Tian, W.; Cui, Z. Characteristics of stress sources and comprehensive control strategies for surrounding rocks of gob-side driving entry in extra thick coal seam. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2024, 52, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, C.; Ren, Z. Parameter determination and effect evaluation of gob-side entry retaining by directional roof cutting and pressure releasing. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 156, 107847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, X.; Bai, J.; Wu, B.; Wang, G.; Li, J.; Chen, D. Study on hydraulic fracture propagation in hard roof under abutment pressure. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2022, 55, 6321–6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Xia, Y.; Gao, J. Study on anti-impact effect of hydraulic fracturing for long holes in medium and high thick hard roof. Saf. Coal Mines 2023, 54, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Yuan, L.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhou, A.; Shu, L. Square-form structure failure model of mining-affected hard rock strata: Theoretical derivation, application and verification. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, E.; Ge, M.; Liu, J. The fracture mechanism and acoustic emission analysis of hard roof: A physical modeling study. Arab. J. Geosci. 2015, 8, 1895–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Zhang, F.; Liu, X.; Feng, D.; Zhang, P. Experimental study of impact of crustal stress on fracture pressure and hydraulic fracture. Rock Soil Mech. 2016, 37, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wu, G.; Zhang, H.; Gao, S.; Sun, Z. Hydraulic fracture initiation and propagation in deep coalbed methane reservoirs considering weak plane: CT scan testing. Gas Sci. Eng. 2024, 125, 205286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Han, P.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, L.; Wang, F. Acoustic emission and splitting surface roughness of sandstone in a Brazilian splitting test under the influence of water saturation. Eng. Geol. 2024, 329, 107369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, J.A.R.; Sanchez, E.C.M.; Roehl, D.; Pereira, L.C. Hydro-mechanical modeling of hydraulic fracture propagation and its interactions with frictional natural fractures. Comput. Geo Tech. 2019, 111, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoto, N.; Chen, Y.; Nishihara, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Yano, S.; Watanabe, S.; Morishige, Y.; Kawakata, H.; Akai, T.; Kurosawa, I.; et al. Monitoring hydraulically-induced fractures in the laboratory using acoustic emissions and the fluorescent method. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2018, 104, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Gong, F.; Luo, Y. A new quantitative method to identify the crack damage stress of rock using AE detection parameters. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2021, 80, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jia, C.; Yang, C.; Zeng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Heng, S.; Wang, L.; Hou, Z. Propagation of hydraulic fissures and bedding planes in hydraulic fracturing of shale. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2015, 34, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Hydraulic fracture propagation in naturally fractured reservoirs: Complex fracture or fracture networks. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2019, 68, 102911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, G.; Chai, H.; Su, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Mechanism of rockburst prevention for directional hydraulic fracturing in deep-hole roof and effect test with multi-parameter. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2019, 36, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Zhang, S.; Qu, Z.; Zhou, T.; Xiao, Y.; Gao, J. Experimental study of hydraulic fracturing for shale by stimulated reservoir volume. Fuel 2014, 128, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F. Influence of hydraulic fracturing of strong roof on mining-induced stress-insight from numerical simulation. J. Min. Strat. Control Eng. 2021, 3, 023032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Zhou, L.; Li, H.; Lu, Y. A three-dimensional numerical investigation of the propagation path of a two-cluster fracture system in horizontal wells. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 173, 1222–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, C.; He, J.; Yang, Q.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, S.; Rui, X.; Zhan, Y.; Ren, B. A coupled simulation method of hydraulic fracturing for relieving mining pressure under hard roof based on DEM method. J. China Soc. 2025, 50, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Kang, H. Pressure relief mechanism and experiment of directional hydraulic fracturing in reused coal pillar roadway. J. China Coal Soc. 2017, 42, 1130–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Kang, H. Hydraulic fracturing initiation and propagation and propagation. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2013, 32, 3169–3179. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; He, J. Failure analysis of flexible formwork concrete wall in gob-side entry and its control measures with roof cutting technology. J. Geophys. Eng. 2025, 22, 909–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, N.; Si, G.; Zhao, M. Experimental study on mechanical properties and failure behaviour of the pre-cracked coal-rock combination. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2021, 80, 2307–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Yu, Q. Patterns of influence of parallel rock fractures on the mechanical properties of the rock–coal combined body. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, J. Principle and application of stress transfer of weak structure body in coal-rock mass cracking. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2022, 39, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Song, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Huang, H.; Lin, Z.; Yao, B. Design and field evaluation of hydraulic fracturing bore holes for terminal mining faces. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, L.; Xu, S. Application and effectiveness evaluation of hydraulic fracturing for roadway pressure relief in coal mines. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2025, 44, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Jiang, P.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Liu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Li, W.; Gao, F.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Roadway soft coal control technology by means of grouting bolts with high pressure-shotcreting in synergy in more than 1000 m deep coal mines. J. China Coal Soc. 2021, 46, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Feng, Y. Hydraulic fracturing technology and its applications in strata control in underground coal mines. Coal Sci. Technol. 2017, 45, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Duan, H.F. Study of roof control by hydraulic fracturing in full-mechanized caving mining with high strength in extra-thick coal layer. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2014, 33, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Xu, J. Surface stepped subsidence related to top-coal caving longwall mining of extremely thick coal seam under shallow cover. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2015, 78, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Zuo, Y.; Song, X.; Wen, P.; Han, Y. Effect of Man-Made Weak Plane on Hydraulic Fracturing of Hard and Stable Roof. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2016, 12, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; He, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. A new criterion for a toughness-dominated hydraulic fracture crossing a natural frictional interface. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 2617–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Research on low-damage mining method and mechanism of overlying thick and hard rock strata structure regulation. J. Min. Strat. Control Eng. 2024, 6, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drill Hole Number | Design Length (m) | Horizontal Distance 3-1302 Auxiliary Transportation Channel Production Assistance (m) | Final Hole Height (m) | Turning Length (m) | Horizontal Hole Length (m) | Fracturing Section Length (m) | Number of Segments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 680 | 56 | 68 | 280 | 400 | 480 | 16 |

| #2 | 650 | 119 | 50 | 230 | 420 | 510 | 17 |

| #3 | 650 | 179 | 55 | 200 | 450 | 510 | 17 |

| #4 | 680 | 242 | 68 | 280 | 400 | 480 | 16 |

| #5 | 620 | 56 | 68 | 180 | 440 | 540 | 18 |

| #6 | 650 | 119 | 50 | 230 | 420 | 570 | 19 |

| #7 | 650 | 179 | 55 | 230 | 420 | 570 | 19 |

| #8 | 620 | 242 | 68 | 180 | 440 | 540 | 18 |

| Coal Face | Monitoring Items | Total | <10 J | 101 J | 102 J | 103 J | 104 J | 105 J | 106 J |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-1802 | Number of MSE/each | 1314 | 92 | 467 | 510 | 243 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Proportion of MSE | / | 7% | 35.54% | 38.81% | 18.49% | 0 | 0.15% | 0 | |

| 3-1302 | Number of MSE/each | 4591 | 232 | 860 | 2716 | 751 | 21 | 8 | 3 |

| Proportion of MSE | / | 5.05% | 18.73% | 59.16% | 16.36% | 0.46% | 0.17% | 0.07% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hu, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C. Comprehensive Evaluation of Directional Hydraulic Fracturing for Roof Pressure Relief and Disaster Prevention Based on Integrated Multi-Parameter Monitoring. Processes 2026, 14, 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010118

Hu S, Zhang H, Zhang C. Comprehensive Evaluation of Directional Hydraulic Fracturing for Roof Pressure Relief and Disaster Prevention Based on Integrated Multi-Parameter Monitoring. Processes. 2026; 14(1):118. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010118

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Shuwei, Hualei Zhang, and Cun Zhang. 2026. "Comprehensive Evaluation of Directional Hydraulic Fracturing for Roof Pressure Relief and Disaster Prevention Based on Integrated Multi-Parameter Monitoring" Processes 14, no. 1: 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010118

APA StyleHu, S., Zhang, H., & Zhang, C. (2026). Comprehensive Evaluation of Directional Hydraulic Fracturing for Roof Pressure Relief and Disaster Prevention Based on Integrated Multi-Parameter Monitoring. Processes, 14(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010118