Technology Readiness Level Assessment of Pleurotus spp. Enzymes for Lignocellulosic Biomass Deconstruction

Abstract

1. Introduction

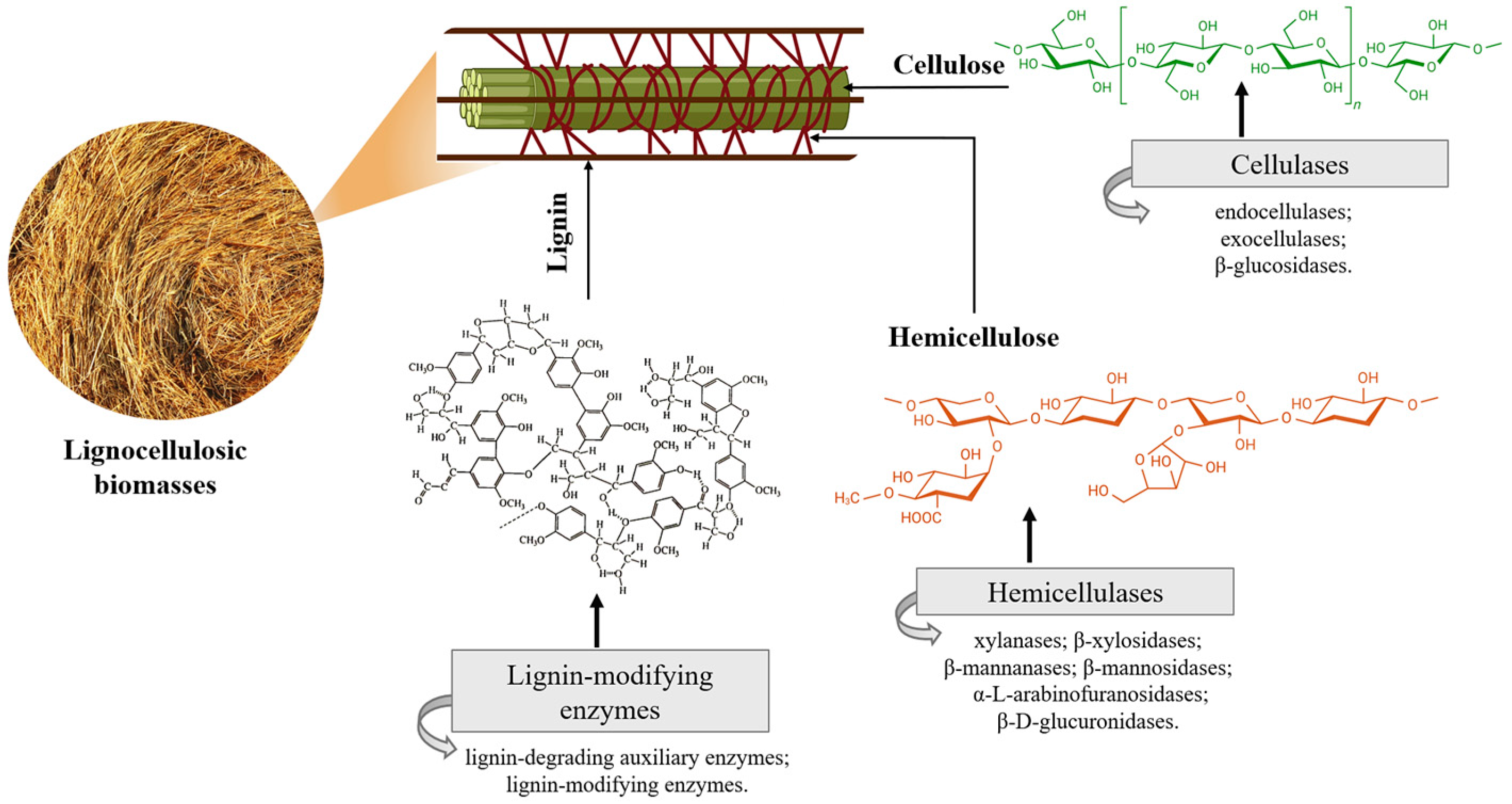

2. Lignocellulosic Biomasses

2.1. Enzymes Involved in Lignocellulosic Biomass Degradation

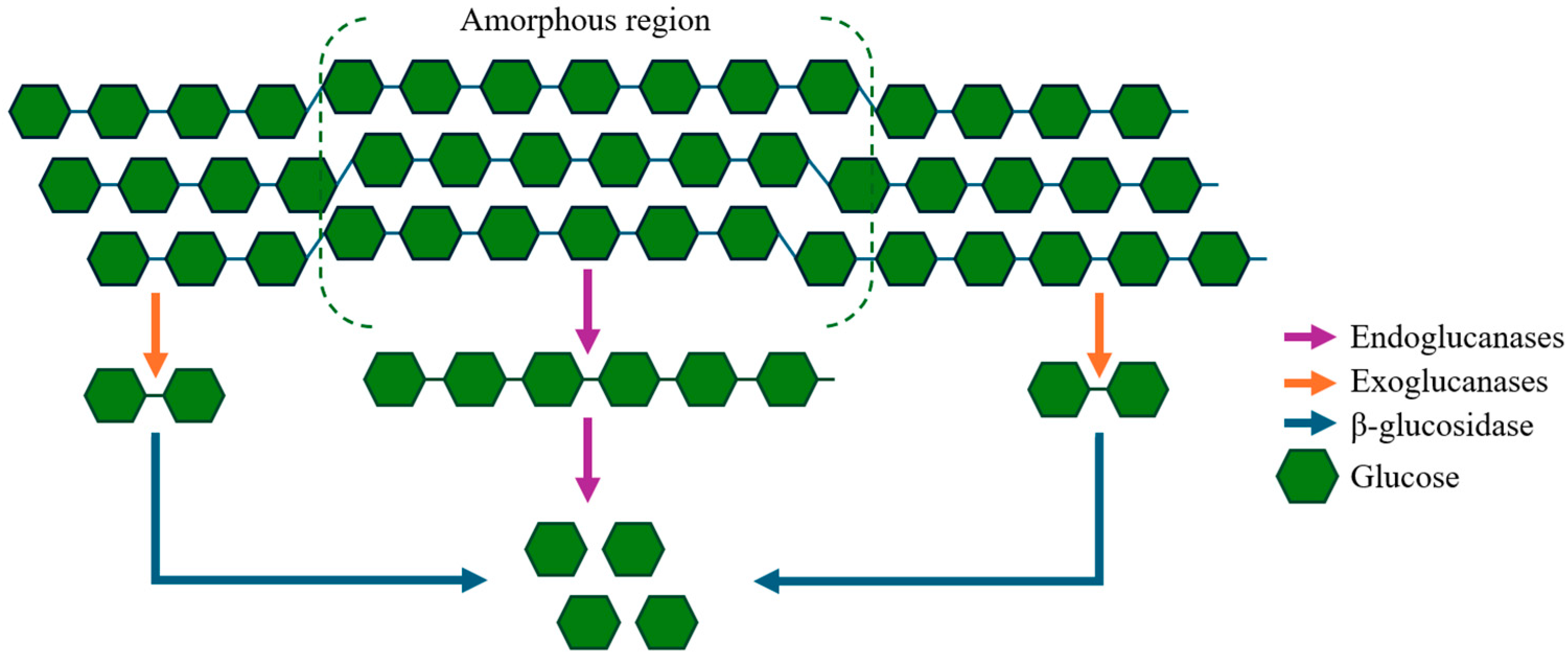

2.1.1. Cellulases

2.1.2. Hemicellulases

2.1.3. Lignin-Modifying Enzymes

3. Technological Maturity of the Platform

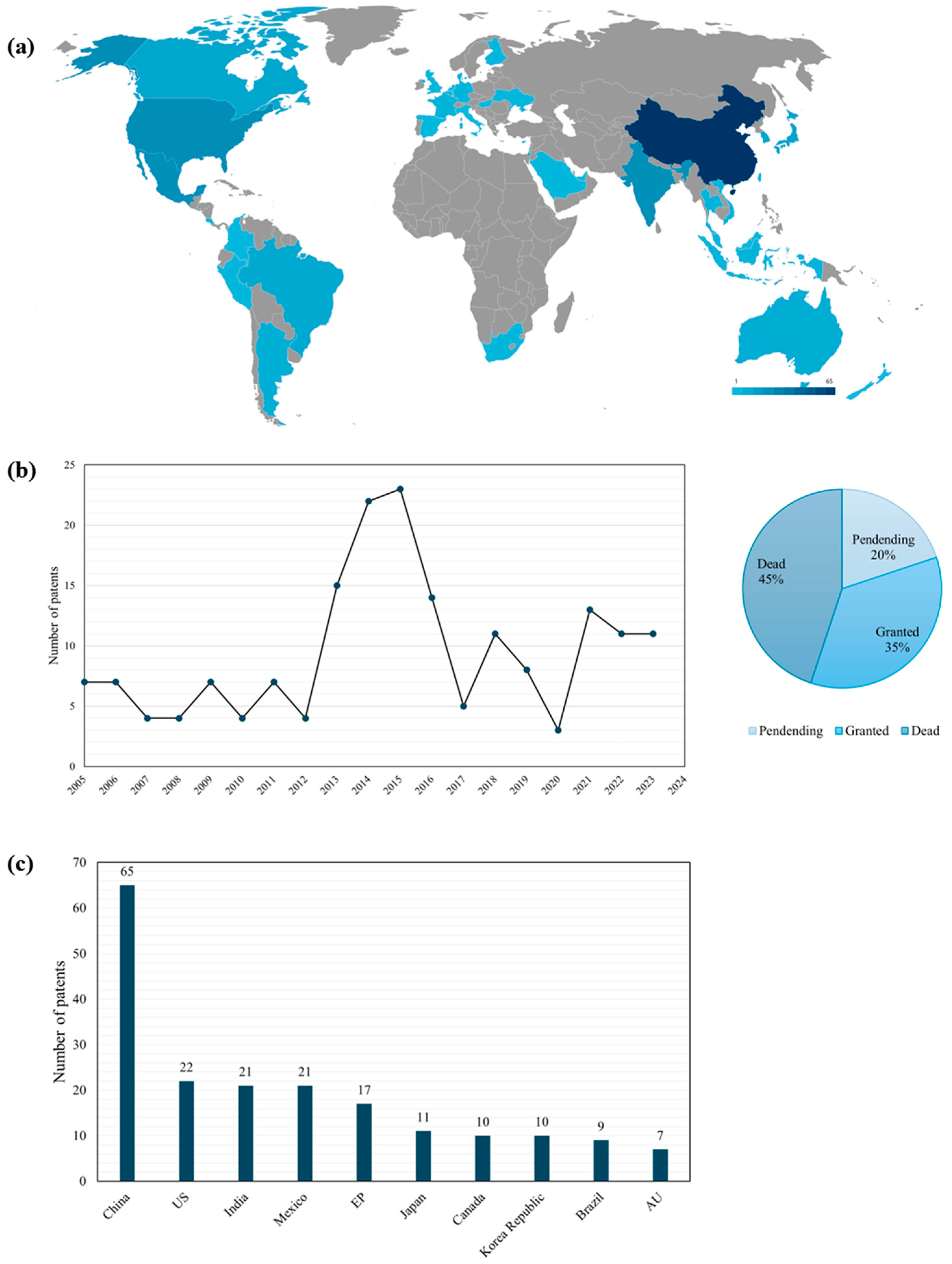

3.1. A Prospection on Patent Bases

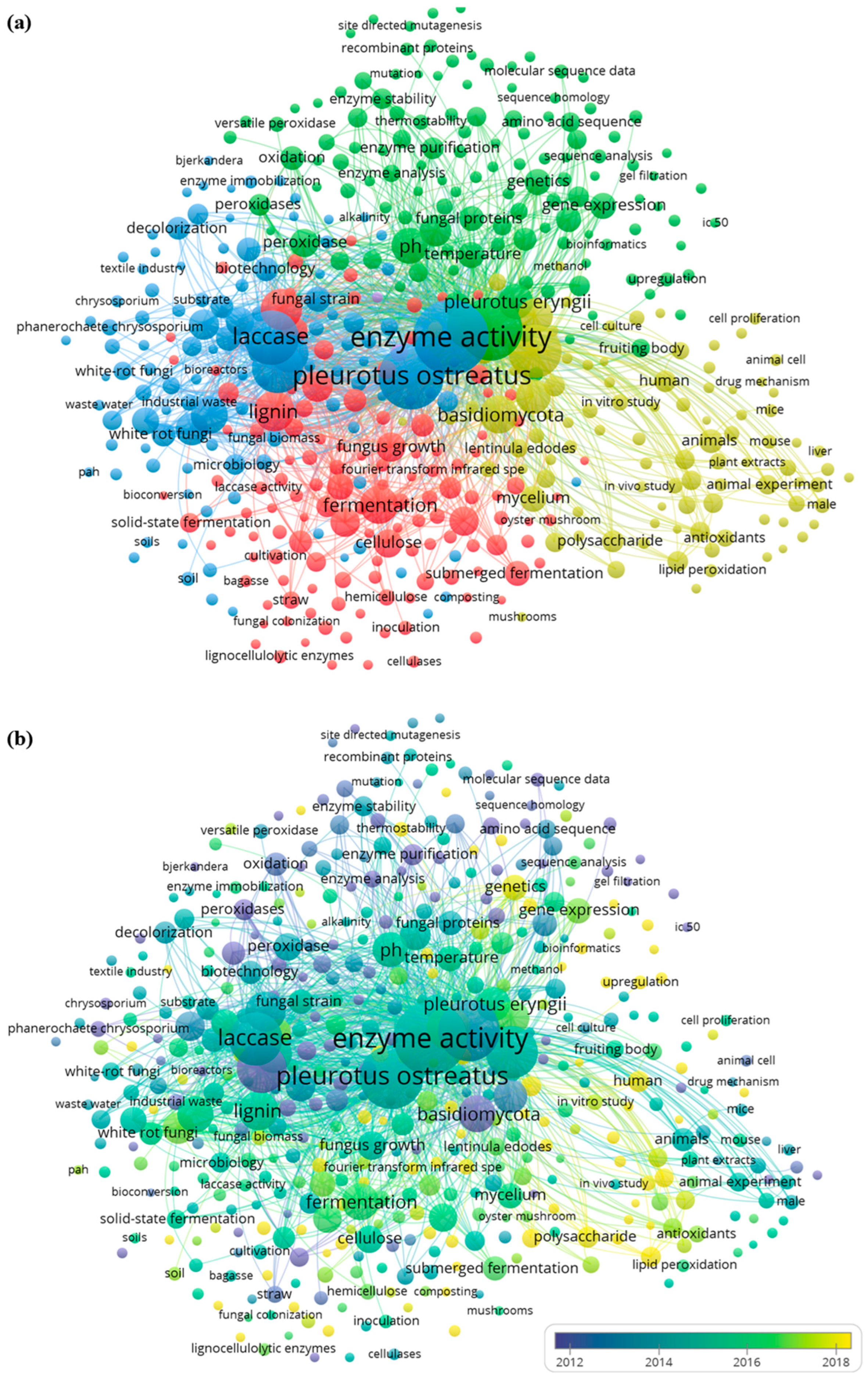

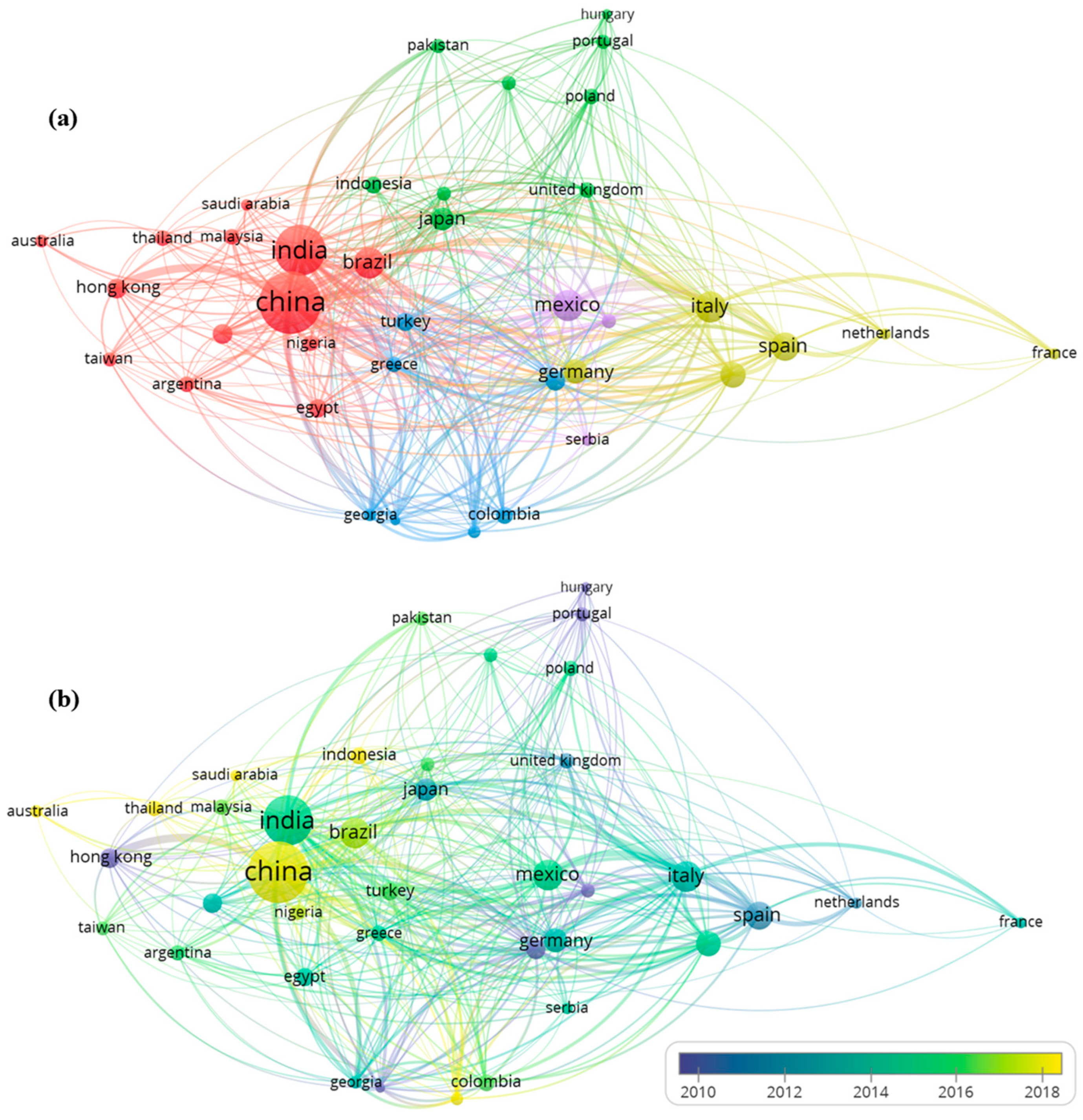

3.2. A Bibliometric Assessment

3.3. Technology Readiness Level

| Microorganism | Carbon Source/Inducer | pH | T (°C) | Agitation (rpm) | Aeration (vvm) | Days | FPase (U mL−1) | CMCase (U mL−1) | Xylanase (U mL−1) | Laccases (U mL−1) | LiP (U mL−1) | MnP (U mL−1) | TRL | Year | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. pulmonarius | Malt extract | - | 24 | 150 | - | 3 | - | 50.0 | 60.0 | - | 14 | - | 3 | 2024 | [34] |

| P. pulmonarius | Malt extract + CMC-Na | - | 24 | 150 | - | 3 | - | 85.0 | - | - | - | - | 3 | 2024 | [34] |

| P. pulmonarius | Malt extract + xylan | - | 24 | 150 | - | 3 | - | - | 60.0 | - | - | - | 3 | 2024 | [34] |

| P. pulmonarius | Malt extract + lignin | - | 24 | 150 | - | 3 | - | - | - | 12 | - | 3 | 2024 | [34] | |

| P. pulmonarius | Malt extract | - | 24 | 150 | - | 7 | - | 15.0 | 30.0 | - | 11 | - | 3 | 2024 | [34] |

| P. pulmonarius | Malt extract + CMC-Na | - | 24 | 150 | - | 7 | - | 40.0 | - | - | - | - | 3 | 2024 | [34] |

| P. pulmonarius | Malt extract + xylan | - | 24 | 150 | - | 7 | - | - | 65.0 | - | - | - | 3 | 2024 | [34] |

| P. pulmonarius | Malt extract + lignin | - | 24 | 150 | - | 7 | - | - | - | - | 37 | - | 3 | 2024 | [34] |

| P. ostreatus 202 | Toquilla straw + glucose | - | 30 | 100 | - | 14 | - | - | - | 1261.11 1 | - | - | 3 | 2024 | [60] |

| P. sajor caju | Sucrose | 6.5 | 28 | 150 | - | 7 | - | - | - | 13.70 1 | - | - | 3 | 2024 | [61] |

| P. ostreatus 2175 | Mandarin peels | 6.0 | 27 | 160 | - | 14 | - | 3.40 | 1.80 | 10.20 | - | - | 3 | 2018 | [62] |

| P. ostreatus 2175 | Olive tree sawdust | 6.0 | 27 | 160 | - | 14 | - | 4.10 | 7.80 | 5.80 | - | - | 3 | 2018 | [62] |

| P. ostreatus 2175 | Olive pomace | 6.0 | 27 | 160 | - | 14 | - | 2.0 | 2.10 | 8.40 | - | - | 3 | 2018 | [62] |

| P. ostreatus 2175 | Olive mill wastewater + sup. | 6.0 | 27 | 160 | - | 14 | - | 0.4 | 0.20 | 21.90 | - | - | 3 | 2018 | [62] |

| P. ostreatus | CMC | 5.5 | 27 | 120 | - | 10 | 34.1 | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 2017 | [63] |

| P. ostreatus | Molasses | 6.2 | 25 | 150 | - | 10 | - | - | - | 10.18 1 | 14.3 | 1.3 | 3 | 2021 | [64] |

| P. florida | Glucose | - | 28 | 150 | - | 21 | - | - | - | 12.11·10−6 | 19.56·10−6 | ~13·10−6 | 3 | 2021 | [65] |

| P. djamor | Glucose | - | 28 | 150 | - | 21 | - | - | - | 14.05·10−6 | 10.64·10−6 | 19.19·10−6 | 3 | 2021 | [65] |

| P. ostreatus | Glucose | - | 28 | 150 | - | 21 | - | - | - | ~9·10−6 | ~10.5·10−6 | 16.36·10−6 | 3 | 2021 | [65] |

| P. citrinopileatus U16–23 | Glucose + green light | - | 28 | - | - | 12 | 1.11 | 1.36 | 11.33 | 12.73 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [59] |

| P. djamor U16–20 | Glucose + green light | - | 28 | - | - | 12 | - | - | 2.34 | 10.99 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [59] |

| P. djamor U16–25 | Glucose + green light | - | 28 | - | - | 12 | - | - | 3.81 | 33.52 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [59] |

| P. djamor U16–28 | Glucose + green light | - | 28 | - | - | 12 | - | 0.05 | 4.27 | 29.41 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [59] |

| P. eryngii U16–30 | Glucose + green light | - | 28 | - | - | 12 | 0.59 | 0.32 | 9.38 | 10.57 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [59] |

| P. eryngii U16–22 | Glucose + green light | - | 28 | - | - | 12 | 1.01 | 1.64 | 14.13 | 22.12 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [59] |

| P. pulmonarius U16–21 | Glucose + green light | - | 28 | - | - | 12 | 1.21 | 1.90 | 13.72 | 21.01 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [59] |

| P. eryngii | Tannic acid | 4.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 748.55 1 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [66] |

| P. florida | Tannic acid | 4.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 736.88 1 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [66] |

| P. sajor caju | 2,6 Dimethoxyphenol | 4.5 | 30 | 180 | - | 25 | - | - | - | 725.44 1 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [66] |

| P. eryngii | 2,6 Dimethoxyphenol | 4.0 | 30 | 180 | - | 25 | - | - | - | 709.80 1 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [66] |

| P. florida | 2,6 Dimethoxyphenol | 4.5 | 30 | 180 | - | 25 | - | - | - | 718.33 1 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [66] |

| P. sajor caju | 2,6 Dimethoxyphenol | 4.5 | 30 | 180 | - | 25 | - | - | - | 725.64 1 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [66] |

| P. eryngii | Copper sulphate | 4.5 | 30 | 180 | - | 25 | - | - | - | 589.91 1 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [66] |

| P. florida | Copper sulphate | 4.0 | 30 | 180 | - | 25 | - | - | - | 574.50 1 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [66] |

| P. sajor caju | Copper sulphate | 4.5 | 30 | 180 | - | 25 | - | - | - | 525.74 1 | - | - | 4 | 2021 | [66] |

| P. eryngii KS004 | Cu2+ | 6.0 | 26 | 150 | - | 8 | - | - | - | 381.10 1 | - | - | 4 | 2024 | [67] |

| P. sajor caju | Pulp wash from orange | 5.0 | 28 | 180 | - | 8 | - | - | - | 126.50 | - | 16.1 | 4 | 2020 | [58] |

| P. foridanus | De-oiled microalgal biomass | 4.9 | 24.7 | 115 | - | 15 | - | - | - | 80.50 | - | - | 4 | 2022 | [68] |

| P. eryngii-3 | Corn flour | 6.0 | 27 | 150 | - | 7 | - | - | - | 6.10 | - | - | 4 | 2022 | [69] |

| P. ostreatus M2191 | Kraft lignin | 7.5 | 20-22 | 100 | - | 3 | - | - | 446.30 1 | - | - | 4 | 2025 | [70] | |

| P. ostreatus LGAM 1123 | Wine lees + glucose | 6.0 | 28 | 200 | 2 | 11 | - | - | - | 54.80 | - | - | 5 | 2024 | [56] |

| P. ostreatus 9506 | Glucose | natural | 28 | 300 | 4 | 8 | - | - | - | 2.27 | - | - | 5 | 2015 | [57] |

3.4. What Factors Hinder the Advancement of the TRLs?

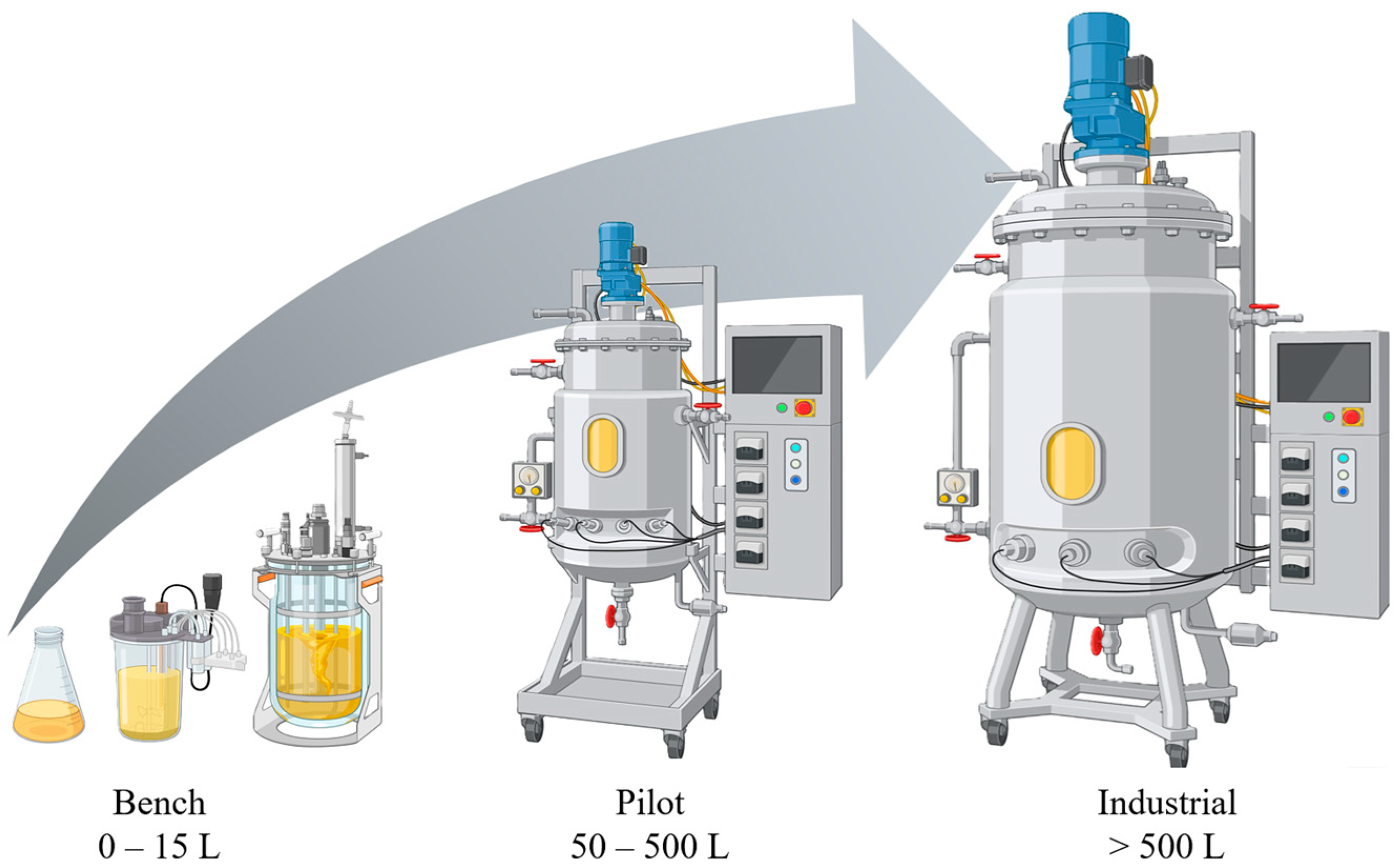

3.4.1. Infrastructure and Costs

3.4.2. Physical Factors

3.4.3. Chemical Factors

3.4.4. Biological Factors

4. Final Considerations and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grand View Research Enzymes Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Type (Industrial, Specialty), By Product (Carbohydrase, Proteases), By Source (Plants, Animals), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2025–2033. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/enzymes-industry/request/rs1 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Huang, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, S. Advances in the Production of Fungi-Derived Lignocellulolytic Enzymes Using Agricultural Wastes. Mycology 2024, 15, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhou, S.; Yu, Q.; Xu, Y. Microbial Saccharification–Biorefinery Platform for Lignocellulose. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 189, 115761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.K.; Xu, C.; Qin, W. Biological Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Biofuels and Bioproducts: An Overview. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janusz, G.; Pawlik, A.; Sulej, J.; Świderska-Burek, U.; Jarosz-Wilkołazka, A.; Paszczyński, A. Lignin Degradation: Microorganisms, Enzymes Involved, Genomes Analysis and Evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 941–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petraglia, T.; Latronico, T.; Pepe, A.; Crescenzi, A.; Liuzzi, G.M.; Rossano, R. Increased Antioxidant Performance of Lignin by Biodegradation Obtained from an Extract of the Mushroom Pleurotus Eryngii. Molecules 2024, 29, 5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, R.C.G.; Brugnari, T.; Bracht, A.; Peralta, R.M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Biotechnological, Nutritional and Therapeutic Uses of Pleurotus Spp. (Oyster Mushroom) Related with Its Chemical Composition: A Review on the Past Decade Findings. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, R.R.; Munafo, J.P.; Salmen, J.; Keen, C.L.; Mistry, B.S.; Whiteley, J.M.; Schmitz, H.H. Mycelium: A Nutrient-Dense Food to Help Address World Hunger, Promote Health, and Support a Regenerative Food System. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 2697–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, A.; Fanelli, F.; Mulè, G.; Moretti, A.; Loi, M. Shedding Light on Pleurotus: An Update on Taxonomy, Properties, and Photobiology. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 295, 128110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmelová, D.; Legerská, B.; Kunstová, J.; Ondrejovič, M.; Miertuš, S. The Production of Laccases by White-Rot Fungi under Solid-State Fermentation Conditions. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 38, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Bajar, S.; Devi, A.; Pant, D. An Overview on the Recent Developments in Fungal Cellulase Production and Their Industrial Applications. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2021, 14, 100652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, C.G. Technology Readiness Levels-National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/somd/space-communications-navigation-program/technology-readiness-levels/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Fang, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; van Lier, J.B.; Spanjers, H. White Rot Fungi Pretreatment to Advance Volatile Fatty Acid Production from Solid-State Fermentation of Solid Digestate: Efficiency and Mechanisms. Energy 2018, 162, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W.D.H.; Gonçalves, T.A.; Uchima, C.A.; dos Reis, L.; Fontana, R.C.; Squina, F.M.; Dillon, A.J.P.; Camassola, M. Comparison of the Production of Enzymes to Cell Wall Hydrolysis Using Different Carbon Sources by Penicillium Echinulatum Strains and Its Hydrolysis Potential for Lignocelullosic Biomass. Process Biochem. 2018, 66, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassaye, S.; Pant, K.K.; Jain, S. Synergistic Effect of Ionic Liquid and Dilute Sulphuric Acid in the Hydrolysis of Microcrystalline Cellulose. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 148, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, A.; Verardi, A.; Lopresto, C.G.; Siciliano, S.; Sangiorgio, P. Lignocellulosic Agricultural Waste Valorization to Obtain Valuable Products: An Overview. Recycling 2023, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, Z.; Sharma, M.; Awasthi, A.K.; Lukk, T.; Tuohy, M.G.; Gong, L.; Nguyen-Tri, P.; Goddard, A.D.; Bill, R.M.; Nayak, S.C.; et al. Lignocellulosic Biorefineries: The Current State of Challenges and Strategies for Efficient Commercialization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 148, 111258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhvi, M.S.; Gokhale, D.V. Lignocellulosic Biomass: Hurdles and Challenges in Its Valorization. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 9305–9320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezania, S.; Oryani, B.; Cho, J.; Talaiekhozani, A.; Sabbagh, F.; Hashemi, B.; Rupani, P.F.; Mohammadi, A.A. Different Pretreatment Technologies of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Bioethanol Production: An Overview. Energy 2020, 199, 117457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Zhang, W.; Ren, S.; Liu, F.; Zhao, C.; Liao, H.; Xu, Z.; Huang, J.; Li, Q.; Tu, Y.; et al. Hemicelluloses Negatively Affect Lignocellulose Crystallinity for High Biomass Digestibility under NaOH and H2SO4 Pretreatments in Miscanthus. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2012, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagoz, P.; Bill, R.M.; Ozkan, M. Lignocellulosic Ethanol Production: Evaluation of New Approaches, Cell Immobilization and Reactor Configurations. Renew. Energy 2019, 143, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Dikshit, P.K.; Sherpa, K.C.; Singh, A.; Jacob, S.; Chandra Rajak, R. Recent Nanobiotechnological Advancements in Lignocellulosic Biomass Valorization: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; de Beeck, B.O.; Thielemans, K.; Ennaert, T.; Snelders, J.; Dusselier, M.; Courtin, C.M.; Sels, B.F. The Role of Pretreatment in the Catalytic Valorization of Cellulose. Mol. Catal. 2020, 487, 110883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, N.; Shreya; Sharma, A.K. Cost-effective Cellulase Production, Improvement Strategies, and Future Challenges. J. Food Process Eng. 2021, 44, e13623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R.; Rai, R.; Bhatt, S.B.; Dhar, P. Technological Road Map of Cellulase: A Comprehensive Outlook to Structural, Computational, and Industrial Applications. Biochem. Eng. J. 2023, 198, 109020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, A.; Jaryal, R.; Bhatia, C.; Singh, N. Elucidating the Potential of Cellulases Isolated from a Locally Isolated Strain (NSF-2) in Paper and Pulp Industry. Clean. Mater. 2022, 6, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsa, G.; Konwarh, R.; Masi, C.; Ayele, A.; Haile, S. Microbial Cellulase Production and Its Potential Application for Textile Industries. Ann. Microbiol. 2023, 73, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyilmaz, G.; Gunay, E. Clarification of Apple, Grape and Pear Juices by Co-Immobilized Amylase, Pectinase and Cellulase. Food Chem. 2023, 398, 133900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, B.C.; Sethi, B.K.; Mishra, R.R.; Dutta, S.K.; Thatoi, H.N. Microbial Cellulases–Diversity & Biotechnology with Reference to Mangrove Environment: A Review. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2017, 15, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasekara, S.; Ratnayake, R. Microbial Cellulases: An Overview and Applications. Cellulose 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, N.; Kumar, B.; Agrawal, K.; Verma, P. Current Perspective on Production and Applications of Microbial Cellulases: A Review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasunuma, T.; Okazaki, F.; Okai, N.; Hara, K.Y.; Ishii, J.; Kondo, A. A Review of Enzymes and Microbes for Lignocellulosic Biorefinery and the Possibility of Their Application to Consolidated Bioprocessing Technology. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 135, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Tewari, R.; Rana, S.S.; Soni, R.; Soni, S.K. Cellulases: Classification, Methods of Determination and Industrial Applications. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016, 179, 1346–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xing, J.; Li, X.; Lu, X.; Liu, G.; Qu, Y.; Zhao, J. Review of Research Progress on the Production of Cellulase from Filamentous Fungi. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, A.K.; Chandrasekhar, G.; Silva, M.B.; Silvério Da Silva, S. The Realm of Cellulases in Biorefinery Development. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2012, 32, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, F.; Fatima, T.; Ibrar, R.; Shabbir, I.; Shah, F.I.; ul Haq, I. Trends in the Development and Current Perspective of Thermostable Bacterial Hemicellulases with Their Industrial Endeavors: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 265, 130993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujibo, H.; Takada, C.; Wakamatsu, Y.; Kosaka, M.; Tsuji, A.; Miyamoto, K.; Inamori, Y. Cloning and Expression of an α-L -Arabinofuranosidase Gene (StxIV) from Streptomyces Thermoviolaceus OPC-520, and Characterization of the Enzyme. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2002, 66, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malgas, S.; van Dyk, J.S.; Pletschke, B.I. A Review of the Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Mannans and Synergistic Interactions between β-Mannanase, β-Mannosidase and α-Galactosidase. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 31, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, T.; Gerday, C.; Feller, G. Xylanases, Xylanase Families and Extremophilic Xylanases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, V.; Saini, J.K.; Singh, S.; Nain, L.; Kuhad, R.C. Arabinofuranosidases: Characteristics, Microbial Production, and Potential in Waste Valorization and Industrial Applications. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 304, 123019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Líter, J.A.; de Eugenio, L.I.; Nieto-Domínguez, M.; Prieto, A.; Martínez, M.J. Hemicellulases from Penicillium and Talaromyces for Lignocellulosic Biomass Valorization: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 324, 124623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, M.; Patel, S.A.H.; Phutela, U.G.; Dhawan, M. Comparative Analysis of Ligninolytic Potential among Pleurotus Ostreatus and Fusarium Sp. with a Special Focus on Versatile Peroxidase. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 4, 1348–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sar, T.; Marchlewicz, A.; Harirchi, S.; Mantzouridou, F.T.; Hosoglu, M.I.; Akbas, M.Y.; Hellwig, C.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Resource Recovery and Treatment of Wastewaters Using Filamentous Fungi. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Chen, Y.; Peng, L.; Gu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Shi, G.; Zhang, K. Method for Preparing Laccase by Liquid Fermentation of Pleurotus Ferulae. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/CN102604902A/en (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Qi, A.; Jing, S.; Meiling, H.; Baokai, C.; Fei, Z.; Ruifeng, M.; Yucheng, D. Enzyme Liquid Containing High-Activity Lignocellulolytic Enzymes and Preparation Method of Enzyme Liquid. Available online: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/056730603/publication/CN105886486A (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Dongai, R.; Jisheng, N.; Qianxiang, B.; Junxiu, Z.; Linzhu, W. Method for Culturing Laccase Based on Pleurotus Eryngii Liquid State Fermentation. Available online: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/091606949/publication/CN118256461A (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Agustinho, B.C.; Daniel, J.L.P.; Zeoula, L.M.; Ferraretto, L.F.; Monteiro, H.F.; Pupo, M.R.; Ghizzi, L.G.; Agarussi, M.C.N.; Heinzen, C.; Lobo, R.R.; et al. Effects of Lignocellulolytic Enzymes on the Fermentation Profile, Chemical Composition, and in Situ Ruminal Disappearance of Whole-Plant Corn Silage. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99, skab295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, S.G.; Faraco, V.; Amore, A.; Letti, L.A.J.; Thomaz Soccol, V.; Soccol, C.R. Statistical Optimization of Laccase Production and Delignification of Sugarcane Bagasse by Pleurotus Ostreatus in Solid-State Fermentation. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 181204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, R.; Ionata, E.; Marcolongo, L.; Vandenberghe, L.P.d.S.; La Cara, F.; Faraco, V. Optimization of Arundo Donax Saccharification by (Hemi)Cellulolytic Enzymes from Pleurotus Ostreatus. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 951871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Pan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Lin, Z. Efficient Conversion of Tea Residue Nutrients: Screening and Proliferation of Edible Fungi. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 9, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasudhevan, P.; Kalaimurugan, D.; Ganesan, S.; Akbar, N.; Dixit, S.; Pu, S. Enhanced Biocatalytic Laccase Production Using Agricultural Waste in Solid-State Fermentation by Aspergillus Oryzae for p-Chlorophenol Degradation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sales, J.C.S.; Santos, A.G.; de Castro, A.M.; Coelho, M.A.Z. A Critical View on the Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Microbial Plastics Biodegradation. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsky, R.; Sabharwall, P.; Hartvigsen, J.; O’Brien, J. Comparative Review of Hydrogen Production Technologies for Nuclear Hybrid Energy Systems. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2020, 123, 103317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekmatmehr, H.; Esmaeili, A.; Pourmahdi, M.; Atashrouz, S.; Abedi, A.; Ali Abuswer, M.; Nedeljkovic, D.; Latifi, M.; Farag, S.; Mohaddespour, A. Carbon Capture Technologies: A Review on Technology Readiness Level. Fuel 2024, 363, 130898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, G.; Batalha, N.; Kumar, A.; Bhaskar, T.; Konarova, M. Recent Advances in Liquefaction Technologies for Production of Liquid Hydrocarbon Fuels from Biomass and Carbonaceous Wastes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 115, 109400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakratsas, G.; Antoniadis, K.; Athanasiou, P.E.; Katapodis, P.; Stamatis, H. Laccase and Biomass Production via Submerged Cultivation of Pleurotus Ostreatus Using Wine Lees. Biomass 2023, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Sun, J.; Tian, B.; Wang, H. A Novel Stirrer Design and Its Application in Submerged Fermentation of the Edible Fungus Pleurotus Ostreatus. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 38, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.D.; Nascimento, V.R.S.; Meneses, D.B.; Vilar, D.S.; Torres, N.H.; Leite, M.S.; Vega Baudrit, J.R.; Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Bharagava, R.N.; et al. Fungal Biosynthesis of Lignin-Modifying Enzymes from Pulp Wash and Luffa Cylindrica for Azo Dye RB5 Biodecolorization Using Modeling by Response Surface Methodology and Artificial Neural Network. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 399, 123094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, N.L.; Avelino, K.V.; Halabura, M.I.W.; Marim, R.A.; Kassem, A.S.S.; Linde, G.A.; Colauto, N.B.; do Valle, J.S. Use of Green Light to Improve the Production of Lignocellulose-Decay Enzymes by Pleurotus Spp. in Liquid Cultivation. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2021, 149, 109860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, K.; Hidrobo, G.; Félix, N.E. Delignification of Toquilla Straw Pulp (Carludovica Palmata) with a Ligninolytic Enzyme Extract Obtained from Pleurotus Ostreatus and ABTS as a Mediator. Waste Biomass Valorization 2024, 15, 6121–6129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, S.; Samuchiwal, S.; Dalvi, V.; Malik, A. Exploring Fungal-Mediated Solutions and Its Molecular Mechanistic Insights for Textile Dye Decolorization. Chemosphere 2024, 360, 142370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisashvili, V.; Kachlishvili, E.; Asatiani, M.D. Efficient Production of Lignin-Modifying Enzymes and Phenolics Removal in Submerged Fermentation of Olive Mill by-Products by White-Rot Basidiomycetes. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2018, 134, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okereke, O.E.; Akanya, H.O.; Egwim, E.C. Purification and Characterization of an Acidophilic Cellulase from Pleurotus Ostreatus and Its Potential for Agrowastes Valorization. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 12, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambatkar, N.; Jadhav, D.D.; Deshmukh, A.; Sattikar, P.; Wakade, G.; Nandi, S.; Kumbhar, P.; Kommoju, P.-R. Functional Screening and Adaptation of Fungal Cultures to Industrial Media for Improved Delignification of Rice Straw. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 155, 106271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illuri, R.; Kumar, M.; Eyini, M.; Veeramanikandan, V.; Almaary, K.S.; Elbadawi, Y.B.; Biraqdar, M.A.; Balaji, P. Production, Partial Purification and Characterization of Ligninolytic Enzymes from Selected Basidiomycetes Mushroom Fungi. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 7207–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, P.; Sanyal, D.; Dey, P. Optimization of Growth Conditions for Enhancing the Production of Microbial Laccase and Its Application in Treating Antibiotic Contamination in Wastewater. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharghi, S.; Ahmadi, F.S.; Kakhki, A.M.; Farsi, M. Copper Increases Laccase Gene Transcription and Extracellular Laccase Activity in Pleurotus Eryngii KS004. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenthamara, D.; Sivaramakrishnan, M.; Ramakrishnan, S.G.; Esakkimuthu, S.; Kothandan, R.; Subramaniam, S. Improved Laccase Production from Pleurotus Floridanus Using Deoiled Microalgal Biomass: Statistical and Hybrid Swarm-Based Neural Networks Modeling Approach. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Feng, J.; Wang, S.; Cao, Y.; Shen, Y. Enhancement of Hyphae Growth and Medium Optimization for Pleurotus Eryngii-3 under Submerged Fermentation. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewage, I.S.R.; Golovko, O.; Hultberg, M. Spawn-Based Pellets of Pleurotus Ostreatus as an Applied Approach for the Production of Laccase in Different Types of Water. J. Microbiol. Methods 2025, 229, 107092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mello, A.F.M.; de Souza Vandenberghe, L.P.; Herrmann, L.W.; Letti, L.A.J.; Burgos, W.J.M.; Scapini, T.; Manzoki, M.C.; de Oliveira, P.Z.; Soccol, C.R. Strategies and Engineering Aspects on the Scale-up of Bioreactors for Different Bioprocesses. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanuf. 2024, 4, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.-H.; Wang, M.-Y.; Yang, L.-H.; Tong, L.-L.; Guo, D.-S.; Ji, X.-J. Optimization and Scale-Up of Fermentation Processes Driven by Models. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaspyridi, L.-M.; Katapodis, P.; Gonou-Zagou, Z.; Kapsanaki-Gotsi, E.; Christakopoulos, P. Optimization of Biomass Production with Enhanced Glucan and Dietary Fibres Content by Pleurotus Ostreatus ATHUM 4438 under Submerged Culture. Biochem. Eng. J. 2010, 50, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reihani, S.F.S.; Khosravi-Darani, K. Influencing Factors on Single-Cell Protein Production by Submerged Fermentation: A Review. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudekula, U.T.; Doriya, K.; Devarai, S.K. A Critical Review on Submerged Production of Mushroom and Their Bioactive Metabolites. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Han, L.-R.; He, H.-W.; Sang, B.; Yu, D.-L.; Feng, J.-T.; Zhang, X. Effects of Agitation, Aeration and Temperature on Production of a Novel Glycoprotein GP-1 by Streptomyces Kanasenisi ZX01 and Scale-Up Based on Volumetric Oxygen Transfer Coefficient. Molecules 2018, 23, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perveen, I.; Bukhari, B.; Sarwar, A.; Aziz, T.; Koser, N.; Younis, H.; Ahmad, Q.; Sabahat, S.; Tzora, A.; Skoufos, I. Applications and Efficacy of Traditional to Emerging Trends in Lacto-Fermentation and Submerged Cultivation of Edible Mushrooms. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 29283–29302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, P.B.; Sowers, T. Temperature Dependence of Metabolic Rates for Microbial Growth, Maintenance, and Survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 4631–4636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radchenkova, N.; Yaşar Yıldız, S. Advanced Optimization of Bioprocess Parameters for Exopolysaccharides Synthesis in Extremophiles. Processes 2025, 13, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šnajdr, J.; Baldrian, P. Temperature Affects the Production, Activity and Stability of Ligninolytic Enzymes InPleurotus Ostreatus AndTrametes Versicolor. Folia Microbiol. 2007, 52, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, E.; Gonser, A.; Zadrazil, F. Influence of Incubation Temperature on Activity of Ligninolytic Enzymes in Sterile Soil ByPleurotus Sp. AndDichomitus Squalens. J. Basic Microbiol. 2000, 40, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquinas, N.; Chithra, C.H.; Bhat, M.R. Progress in Bioproduction, Characterization and Applications of Pullulan: A Review. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 12347–12382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunamneni, A.; Ballesteros, A.; Plou, F.J.; Alcalde, M. Fungal Laccase—A Versatile Enzyme for Biotechnological Applications Fungal Laccase—A Versatile Enzyme for Biotechnological Applications. In Communicating Current Research and Educational Topics and Trends in Applied Microbiology; Formatex Research Center: Badajoz, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Germec, M.; Turhan, I. Effect of PH Control and Aeration on Inulinase Production from Sugarbeet Molasses in a Bench-Scale Bioreactor. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2023, 13, 4727–4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzouridou, F.; Roukas, T.; Kotzekidou, P. Effect of the Aeration Rate and Agitation Speed on β-Carotene Production and Morphology of Blakeslea Trispora in a Stirred Tank Reactor: Mathematical Modeling. Biochem. Eng. J. 2002, 10, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giavasis, I.; Harvey, L.M.; McNeil, B. The Effect of Agitation and Aeration on the Synthesis and Molecular Weight of Gellan in Batch Cultures of Sphingomonas Paucimobilis. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2006, 38, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez Arango, C.; Nieto, I.J. Cultivo Biotecnológico de Macrohongos Comestibles: Una Alternativa En La Obtención de Nutracéuticos. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2013, 30, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazenda, M.L.; Seviour, R.; McNeil, B.; Harvey, L.M. Submerged Culture Fermentation of “Higher Fungi”: The Macrofungi. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 63, 33–103. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, K.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Khan, A.W.; Normakhamatov, N.; Wang, Z. Characterization, Optimization, and Scaling-up of Submerged Inonotus Hispidus Mycelial Fermentation for Enhanced Biomass and Polysaccharide Production. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 197, 1534–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krull, R.; Wucherpfennig, T.; Esfandabadi, M.E.; Walisko, R.; Melzer, G.; Hempel, D.C.; Kampen, I.; Kwade, A.; Wittmann, C. Characterization and Control of Fungal Morphology for Improved Production Performance in Biotechnology. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 163, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagianni, M. Fungal Morphology and Metabolite Production in Submerged Mycelial Processes. Biotechnol. Adv. 2004, 22, 189–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.-J. Recent Advances in Bioreactor Engineering. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2010, 27, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrone, F.; O’Connor, K.E. Cultivation of Filamentous Fungi in Airlift Bioreactors: Advantages and Disadvantages. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 109, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvigne, F.; Lecomte, J. Foam Formation and Control in Bioreactors. In Encyclopedia of Industrial Biotechnology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tiso, T.; Demling, P.; Karmainski, T.; Oraby, A.; Eiken, J.; Liu, L.; Bongartz, P.; Wessling, M.; Desmond, P.; Schmitz, S.; et al. Foam Control in Biotechnological Processes—Challenges and Opportunities; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 4, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Tinoco-valencia, R.; Gómez-cruz, C.; Galindo, E.; Serrano-carreón, L. Toward an Understanding of the Effects of Agitation and Aeration on Growth and Laccases Production by Pleurotus Ostreatus. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 177, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazir, M.; Iram, A.; Cekmecelioglu, D.; Demirci, A. Approaches for Producing Fungal Cellulases Through Submerged Fermentation. Front. Biosci. 2024, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iram, A.; Özcan, A.; Yatmaz, E.; Turhan, İ.; Demirci, A. Effect of Microparticles on Fungal Fermentation for Fermentation-Based Product Productions. Processes 2022, 10, 2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisashvili, V. Submerged Cultivation of Medicinal Mushrooms: Bioprocesses and Products (Review). Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2012, 14, 211–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Chen, H. High-Density Mammalian Cell Cultures in Stirred-Tank Bioreactor without External PH Control. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 231, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogalski, J.; Szczodrak, J.; Janusz, G. Manganese Peroxidase Production in Submerged Cultures by Free and Immobilized Mycelia of Nematoloma Frowardii. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Włodarczyk, A.; Krakowska, A.; Sułkowska-Ziaja, K.; Suchanek, M.; Zięba, P.; Opoka, W.; Muszyńska, B. Pleurotus Spp. Mycelia Enriched in Magnesium and Zinc Salts as a Potential Functional Food. Molecules 2020, 26, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Contreras, S.; Avalos-de la Cruz, D.A.; Lizardi-Jiménez, M.A.; Herrera-Corredor, J.A.; Baltazar-Bernal, O.; Hernández-Martínez, R. Production of Ligninolytic and Cellulolytic Fungal Enzymes for Agro-Industrial Waste Valorization: Trends and Applicability. Catalysts 2024, 15, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Tsai, M.-L.; Nargotra, P.; Chen, C.-W.; Kuo, C.-H.; Sun, P.-P.; Dong, C.-D. Agro-Industrial Food Waste as a Low-Cost Substrate for Sustainable Production of Industrial Enzymes: A Critical Review. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussatto, S.I. Brewer’s Spent Grain: A Valuable Feedstock for Industrial Applications. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 1264–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisashvili, V.; Penninckx, M.; Kachlishvili, E.; Asatiani, M.; Kvesitadze, G. Use of Pleurotus Dryinus for Lignocellulolytic Enzymes Production in Submerged Fermentation of Mandarin Peels and Tree Leaves. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2006, 38, 998–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, I.U.; Bilal Saeed, M.; Nawaz, A.; Mustafa, Z.; Akram, F. Strain Improvement of Aspergillus Oryzae for Enhanced Biosynthesis of Phytase through Chemical Mutagenesis. Pakistan J. Bot. 2022, 54, 2347–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.H.; Cilli, E.M.; Ernandes, J.R. Structural Complexity of the Nitrogen Source and Influence on Yeast Growth and Fermentation. J. Inst. Brew. 2002, 108, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datsomor, O.; Yan, Q.; Opoku-Mensah, L.; Zhao, G.; Miao, L. Effect of Different Inducer Sources on Cellulase Enzyme Production by White-Rot Basidiomycetes Pleurotus Ostreatus and Phanerochaete Chrysosporium under Submerged Fermentation. Fermentation 2022, 8, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, N.; Vlăduț, V.; Biriș, S.-Ș. Sustainable Valorization of Waste and By-Products from Sugarcane Processing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Yu, J.; Ma, Y.; Cai, L.; Zheng, L.; Gong, W.; Liu, Q. Corn Steep Liquor: Green Biological Resources for Bioindustry. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 3280–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veiter, L.; Rajamanickam, V.; Herwig, C. The Filamentous Fungal Pellet—Relationship between Morphology and Productivity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 2997–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Ó.J.; Montoya, S.; Vargas, L.M. Polysaccharide Production by Submerged Fermentation. In Polysaccharides; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 451–473. [Google Scholar]

| TRL Level | NASA Description [12] | Requirements Proposed in This Paper 1 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Basic principles observed and reported | Bibliographic review and research ideation |

| 2 | Technology concept and/or application formulated | Research planning |

| 3 | Analytical and experimental critical function and/or characteristic proof-of-concept | Flask scale experiments |

| 4 | Component and/or breadboard validation in laboratory environment | Flask scale optimization |

| 5 | Component and/or breadboard validation in relevant environment | Bench scale experiments |

| 6 | System/subsystem model or prototype demonstration in a relevant environment (ground or space) | Pilot scale experiments |

| 7 | System prototype demonstration in a space environment | Production on industrial environment |

| 8 | Actual system completed and “flight qualified” through test and demonstration (ground or space) | Bioproduct or process introduced to the market |

| 9 | Actual system “flight proven” through successful mission operations | Bioproduct or process accepted by consumers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Schein, D.; Escosteguy, O.C.; Pezzini, G.N.; Wancura, J.H.C.; Mazutti, M.A. Technology Readiness Level Assessment of Pleurotus spp. Enzymes for Lignocellulosic Biomass Deconstruction. Processes 2026, 14, 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010112

Schein D, Escosteguy OC, Pezzini GN, Wancura JHC, Mazutti MA. Technology Readiness Level Assessment of Pleurotus spp. Enzymes for Lignocellulosic Biomass Deconstruction. Processes. 2026; 14(1):112. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010112

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchein, Dinalva, Olimpio C. Escosteguy, Gustavo N. Pezzini, João H. C. Wancura, and Marcio A. Mazutti. 2026. "Technology Readiness Level Assessment of Pleurotus spp. Enzymes for Lignocellulosic Biomass Deconstruction" Processes 14, no. 1: 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010112

APA StyleSchein, D., Escosteguy, O. C., Pezzini, G. N., Wancura, J. H. C., & Mazutti, M. A. (2026). Technology Readiness Level Assessment of Pleurotus spp. Enzymes for Lignocellulosic Biomass Deconstruction. Processes, 14(1), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010112