Solubility and Exsolution Behavior of CH4 and CO2 in Reservoir Fluids: Implications for Fluid Compositional Evolution—A Case Study of Ledong 10 Area, Yinggehai

Abstract

1. Introduction

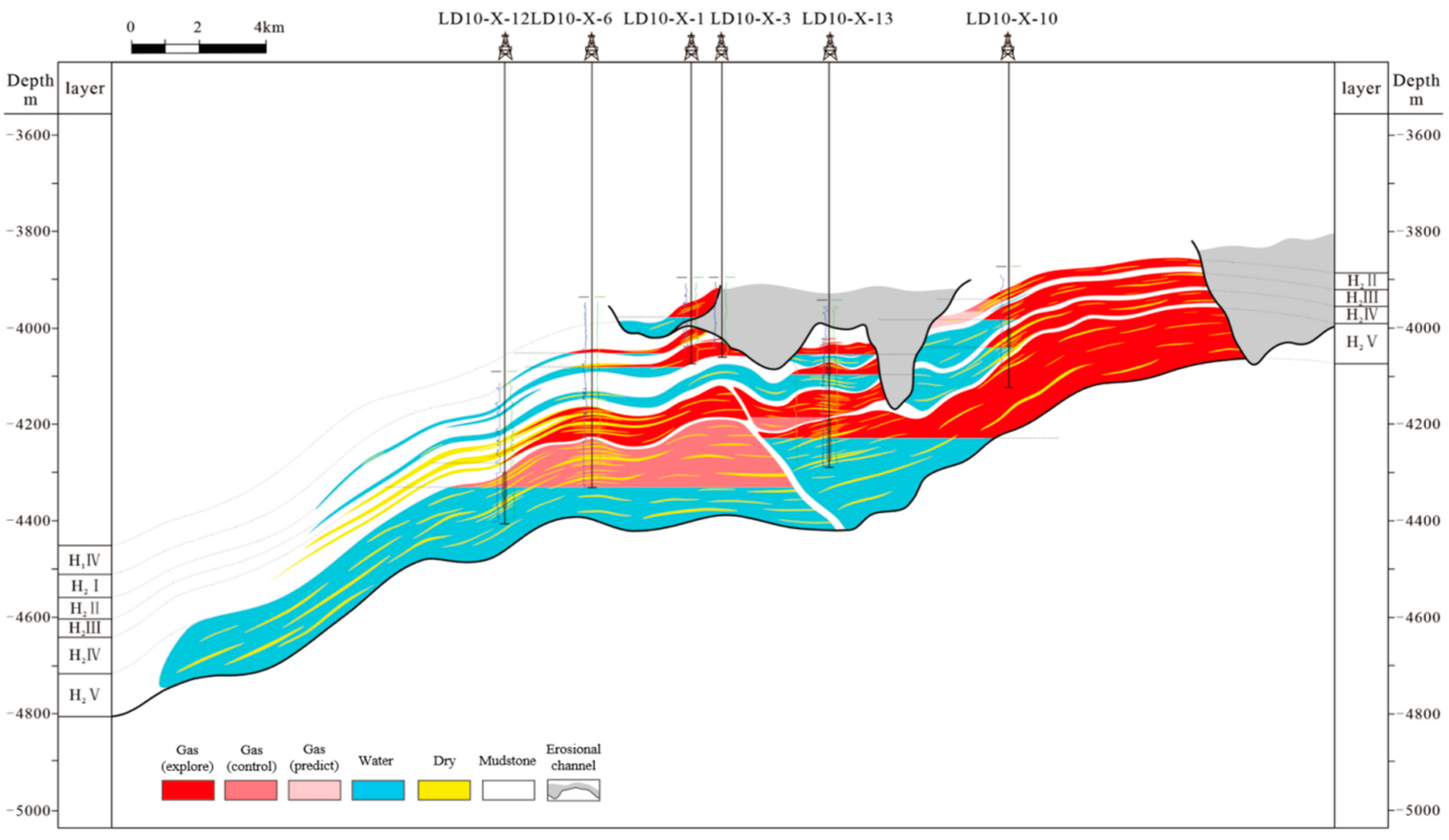

2. Geological Characteristics of the LD10-X Gas Field

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Methods

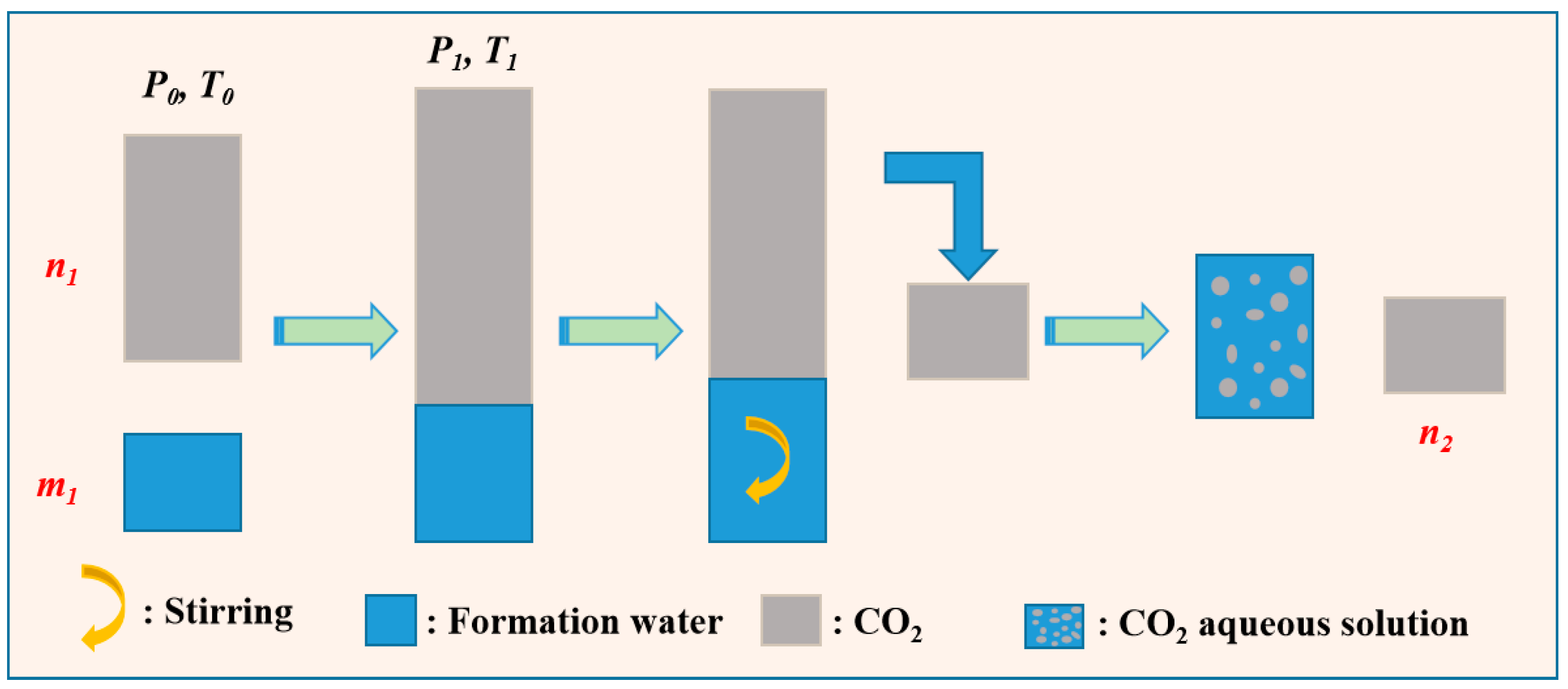

3.2.1. Measurement of CO2 Solubility

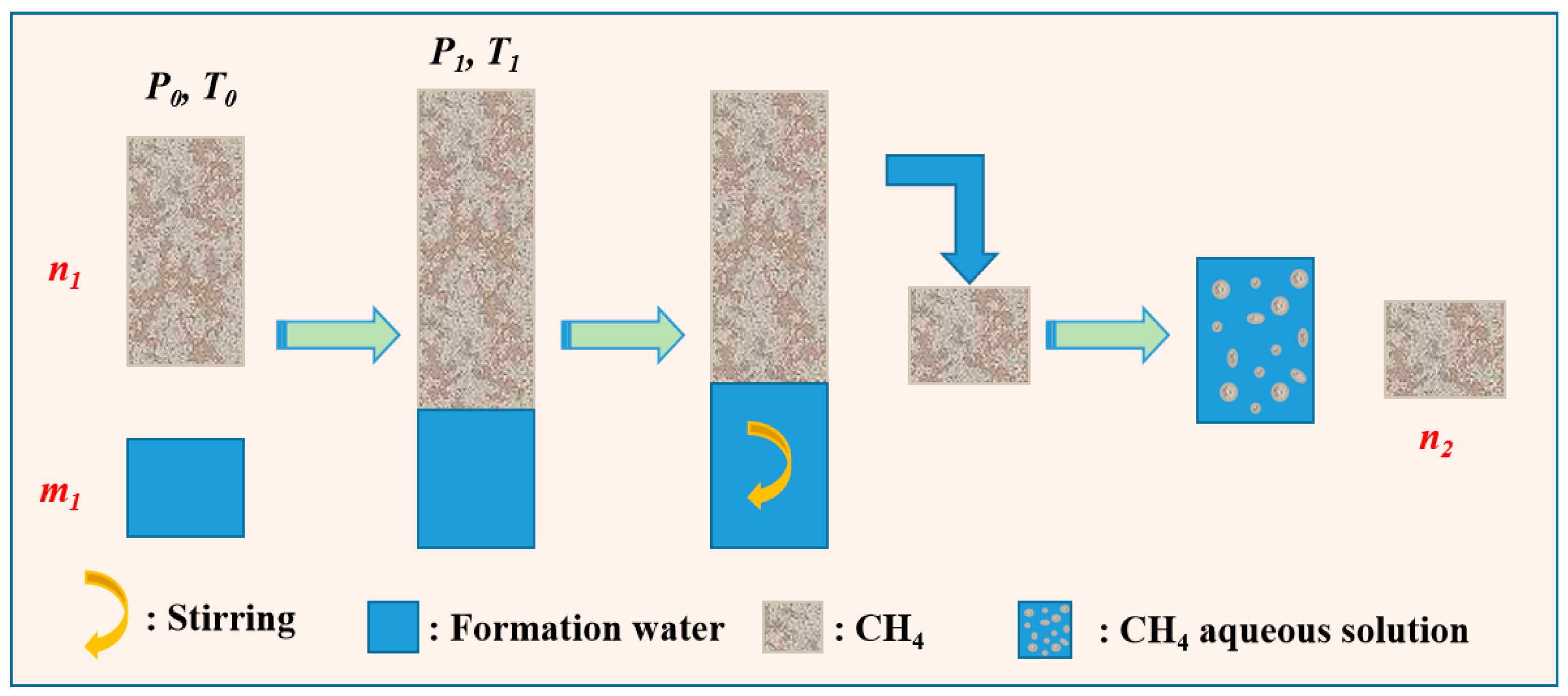

3.2.2. Measurement of CH4 Solubility

3.2.3. Measurement of Exsolution of CO2

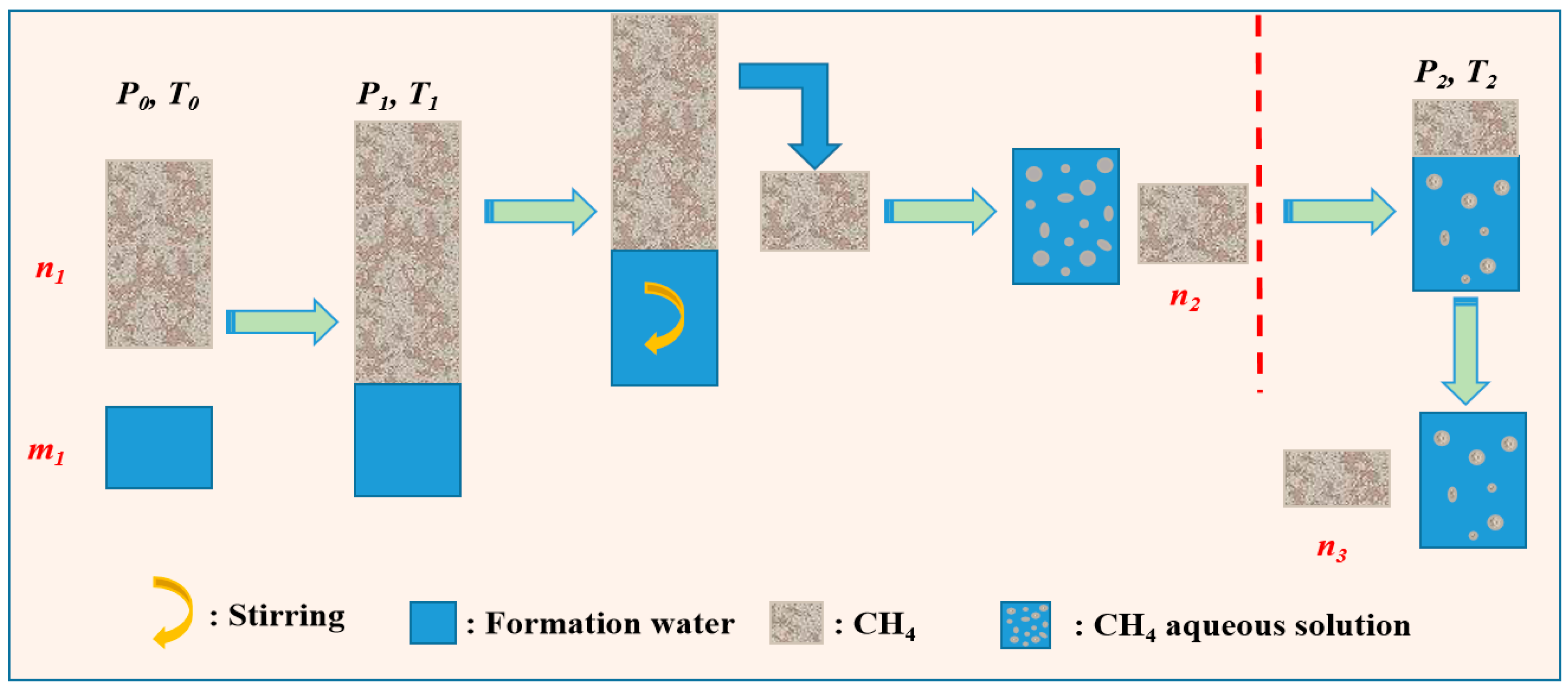

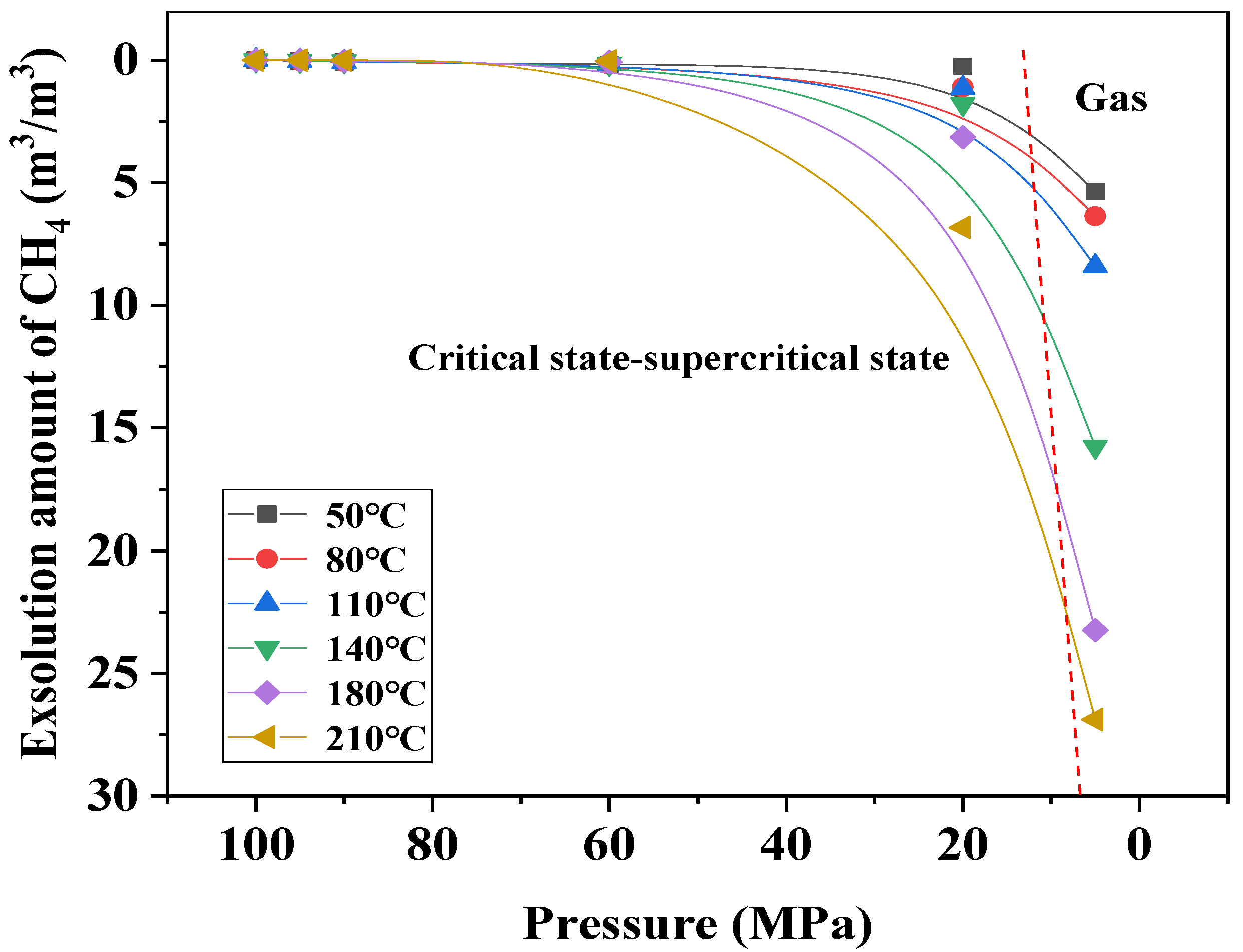

3.2.4. Measurement of Exsolution of CH4

4. Results and Discussion

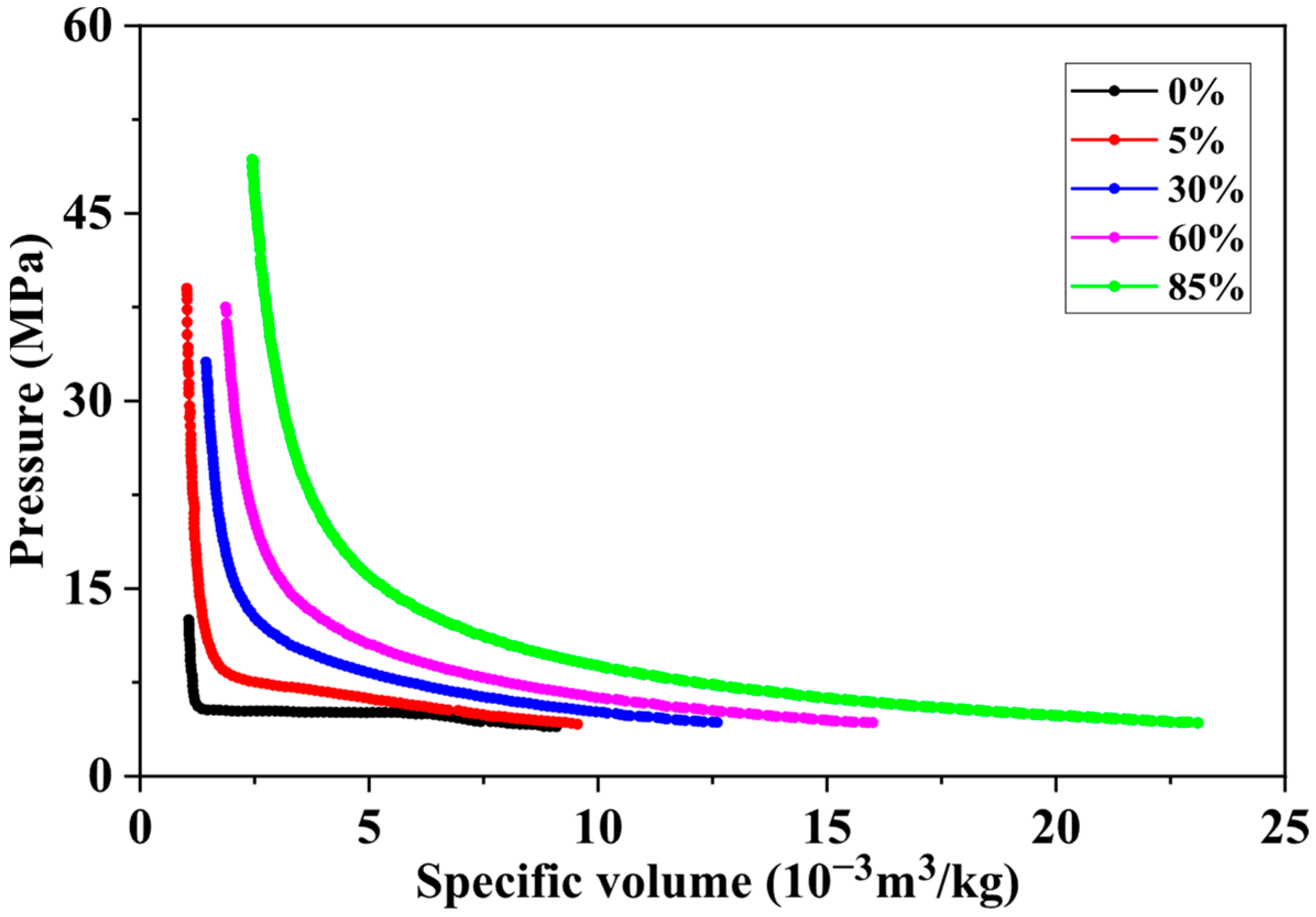

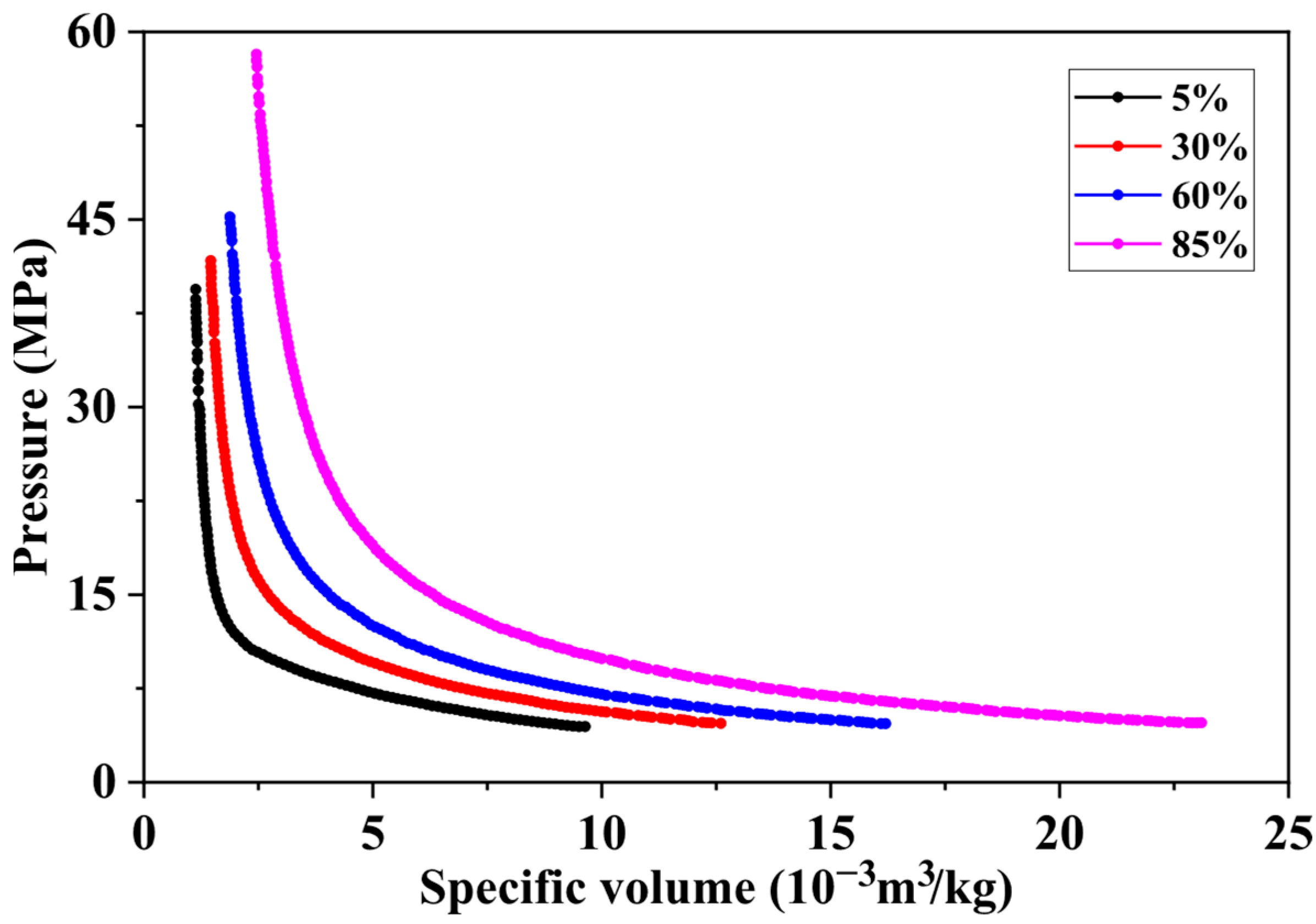

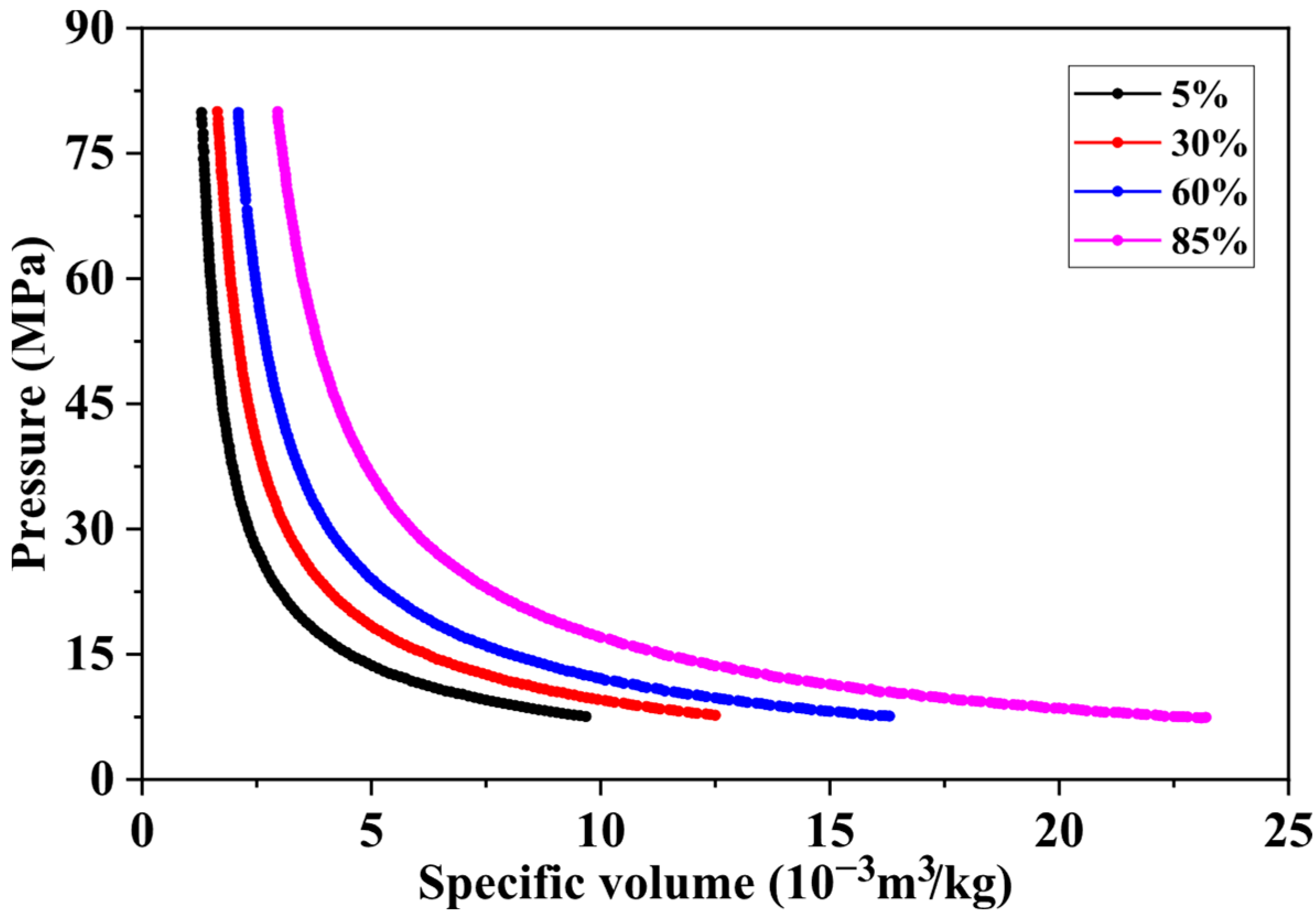

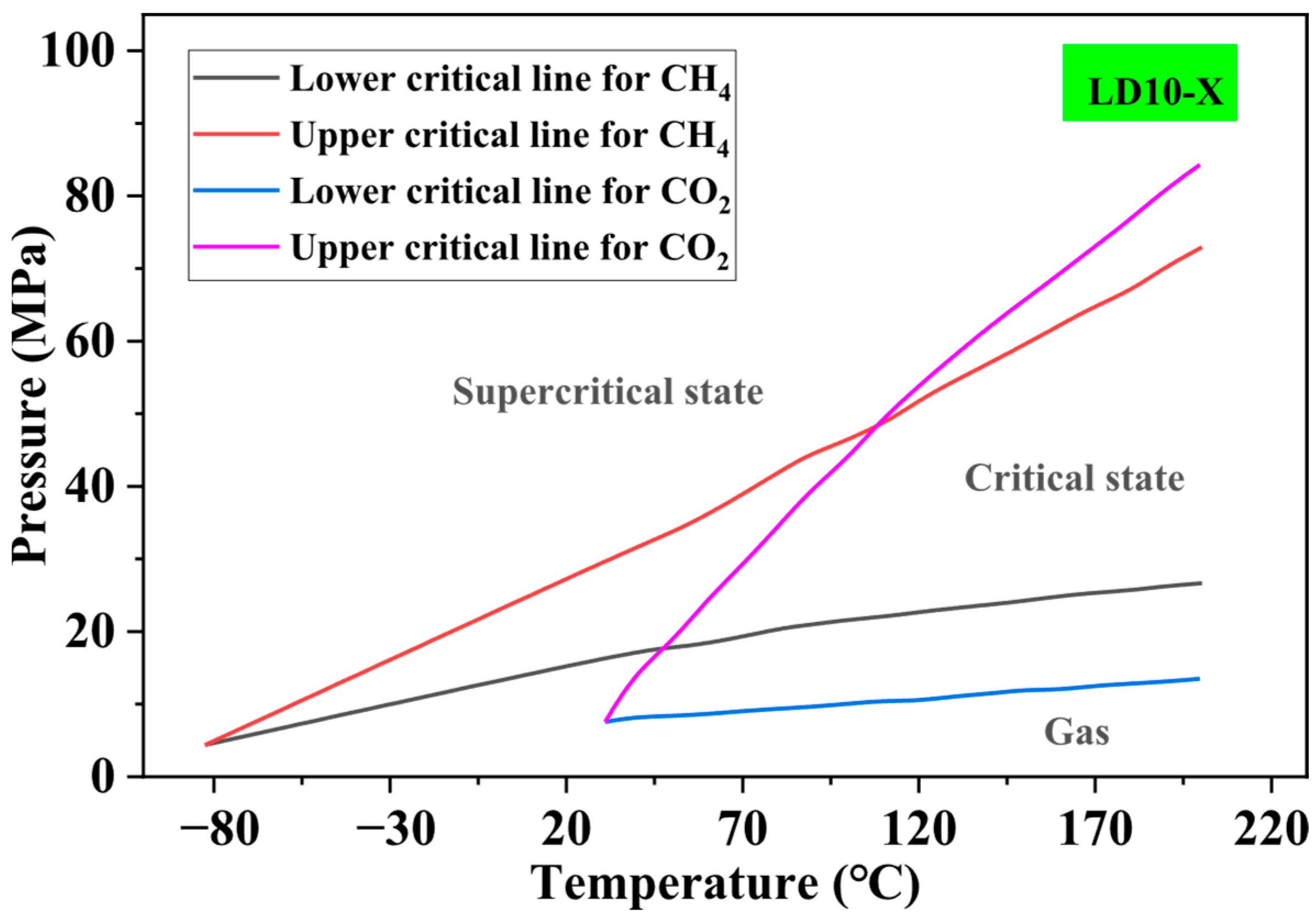

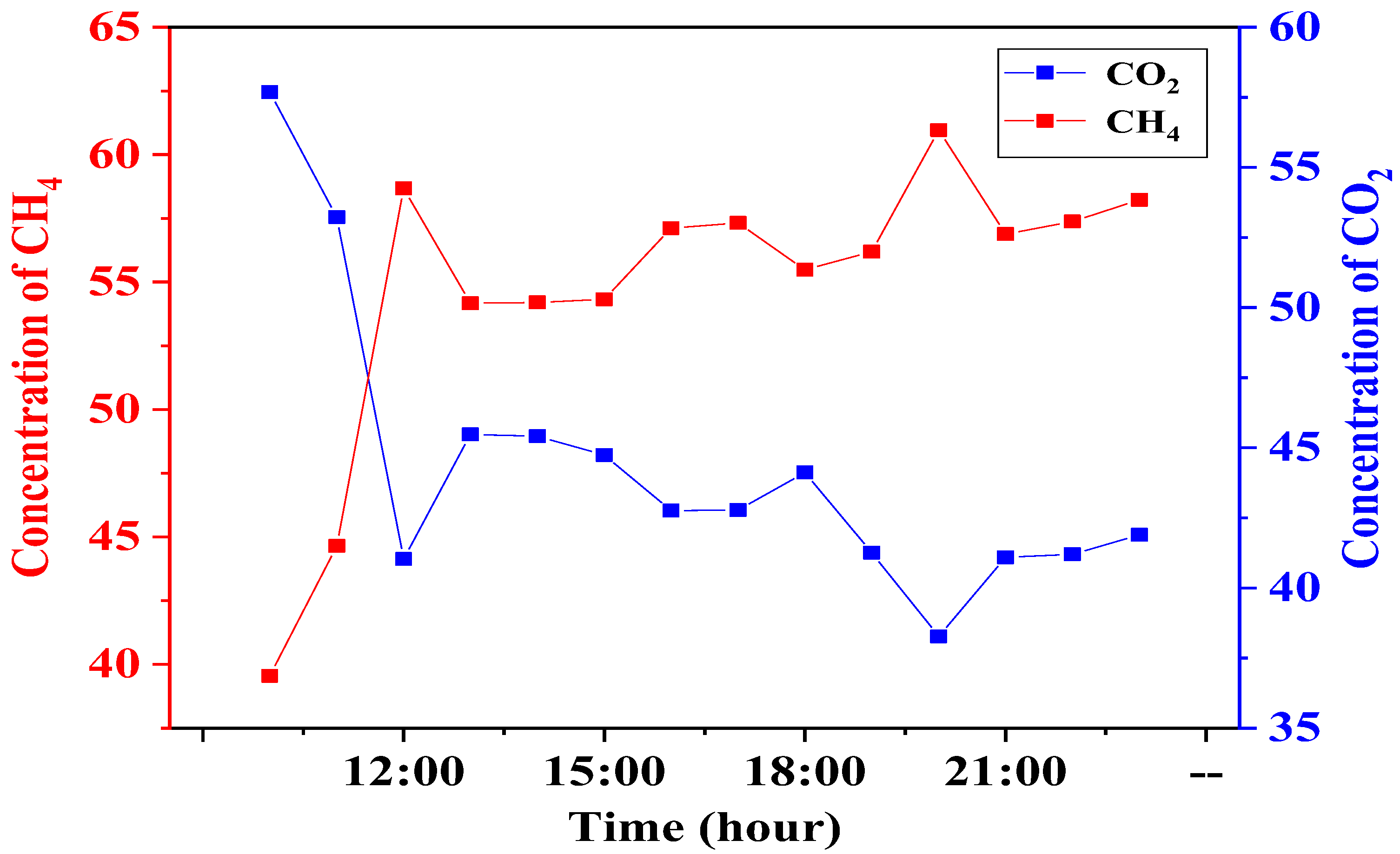

4.1. Study on Fluid Phase Characteristics of the LD10-X Gas Field

4.2. Study on the Solubility Law of CH4 and CO2 in Formation Water

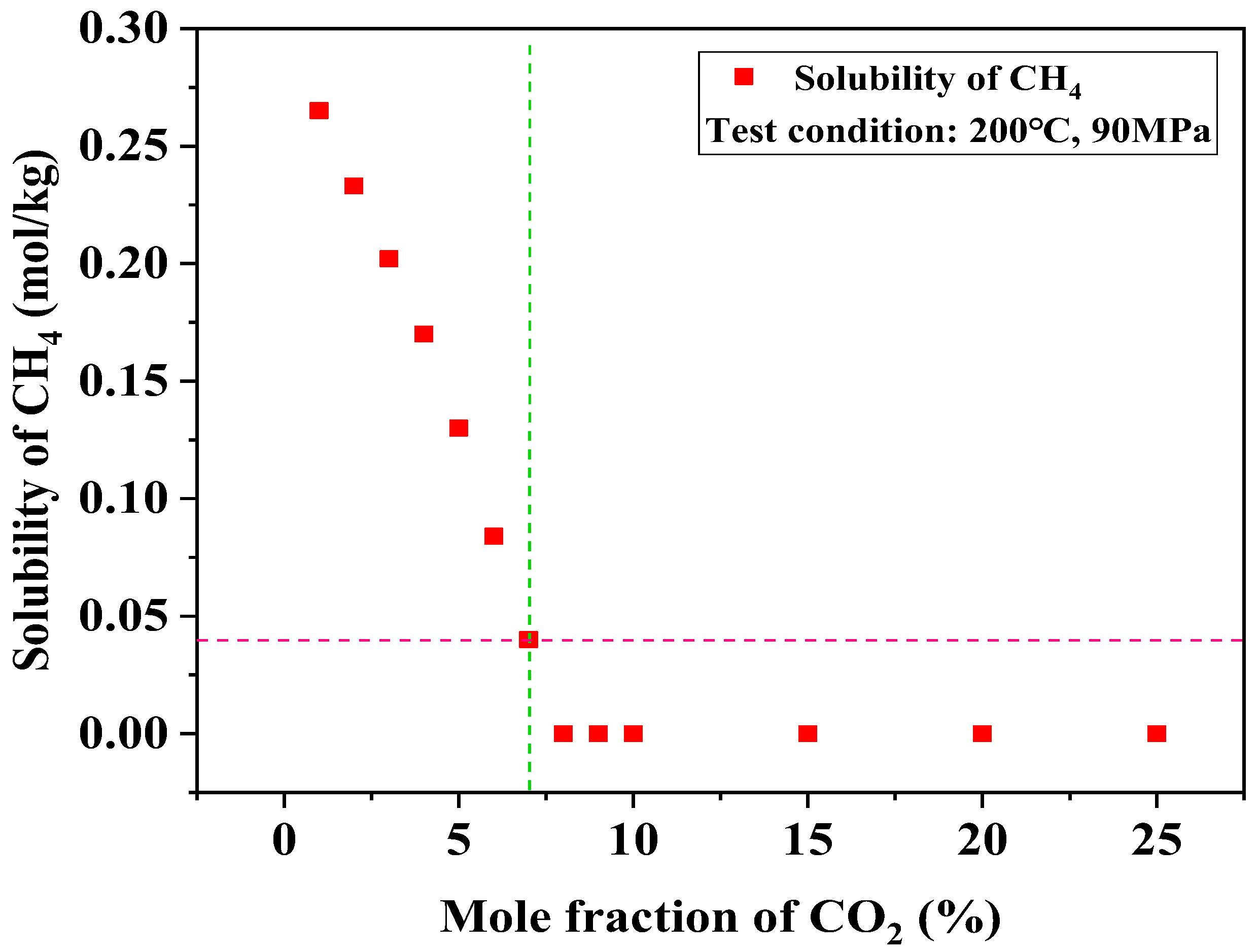

4.2.1. The Effect of CO2 and CH4 Mixing Ratio on Solubility

4.2.2. The Effect of CO2 and CH4 Solubility Sequence on Solubility

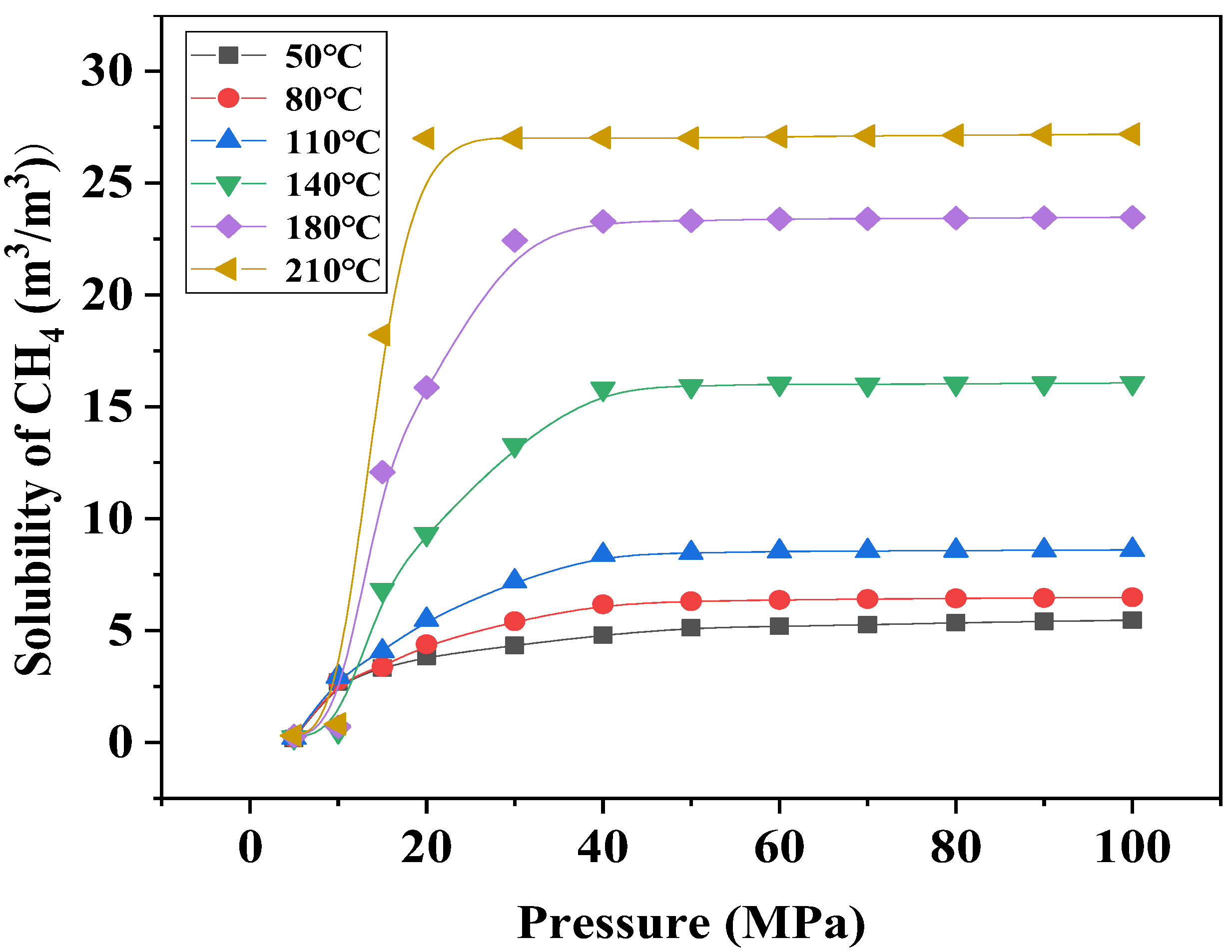

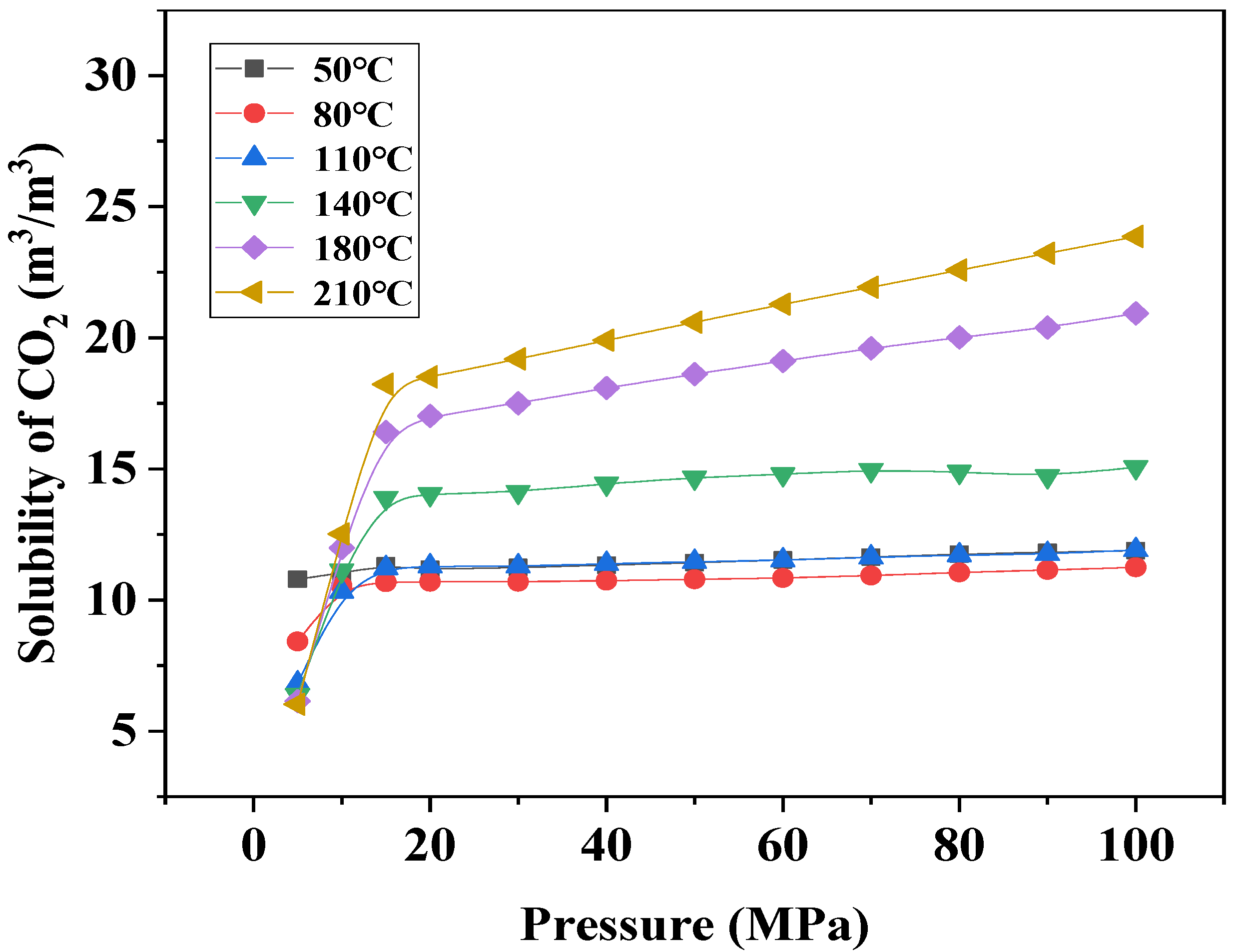

4.2.3. The Solubility of CO2 and CH4 with Temperature and Pressure

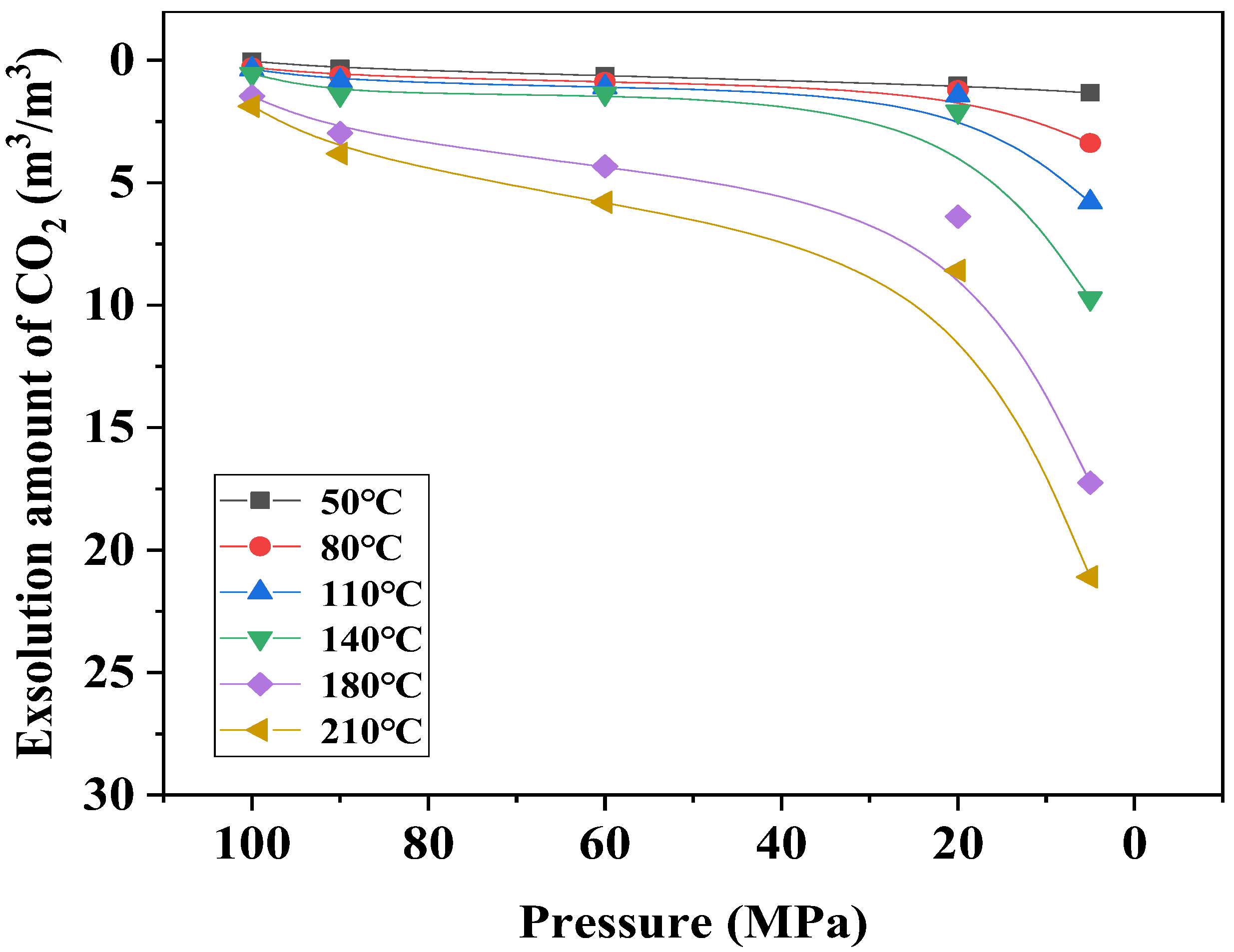

4.3. Study on the Exsolution Law of CO2 and CH4

4.4. Application Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kurnia, K.A.; How, C.J.; Matheswaran, P.; Noh, M.H.; Alamsjah, M.A. Insight into the molecular mechanism that controls the solubility of CH4 in ionic liquids. R. Soc. Chem. 2020, 44, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Jiang, P.X.; He, D.; Chen, X.; Xu, R. Experimental investigation on the behavior of supercritical CO2 during reservoir depressurization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 15, 8869–8876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, C.M.; Doughty, C.; Spycher, N. The role of CO2 in CH4 exsolution from deep brine: Implications for geologic carbon sequestration. Greenh. Gases Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Li, R.; Ma, J.; He, D.; Jiang, P. Effect of mineral dissolution/precipitation and CO2 exsolution on CO2 transport in geological carbon storage. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2056–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Huang, Z.L.; Huang, B.J.; Yuan, J.; Tong, C. The solution and exsolution characteristics of natural gas components in water at high temperature and pressure and their geological meaning. Pet. Sci. 2012, 9, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huang, X.; Guo, X.; Zhou, X.; Shen, C.; Lu, X.; Qi, Z.; Xiao, Q.; Yan, W. Effects of water invasion law on gas wells in high temperature and high pressure gas reservoir with a large accumulation of water-soluble gas. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2019, 62, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Wang, M.; Wang, H. Adsorption characteristics of CH4 and CO2 in shale at high pressure and temperature. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 18527–18536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.Z.; Duan, X.G.; Chang, J.; Bo, Y.; Huang, Y. Investigation of CH4/CO2 competitive adsorption-desorption mechanisms for enhanced shale gas production and carbon sequestration using nuclear magnetic resonance. Energy 2023, 278, 127964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Shen, T.T.; Lin, W.S.; Gu, A.; Ju, Y. Experimental determination of CO2 solubility in liquid CH4/N2 mixtures at cryogenic temperatures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 9403–9408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruusgaard, H.; Beltran, J.G.; Servio, P. Solubility measurements for the CH4 + CO2 + H2O system under hydrate–liquid–vapor equilibrium. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2010, 296, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.F.; He, L.Y.; Fan, Z.Q.; He, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Z. Investigation of gas solubility and its effects on natural gas reserve and production in tight formations. Fuel 2021, 295, 120507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, U.; Shah, J.K. Monte Carlo simulations of pure and mixed gas solubilities of CO2 and CH4 in nonideal ionic liquid-ionic liquid mixtures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 58, 22569–22578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yu, J.; Shi, H.; Guo, J.; Liu, D.; Lin, J.; Song, S.; Wu, H.; Gong, J. Study of methane solubility calculation based on modified Henry’s law and BP neural network. Processes 2024, 12, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirrahi, M.; Azin, R.; Hassanzadeh, H.; Moshfeghian, M. Mutual solubility of CH4, CO2, H2S, and their mixtures in brine under subsurface disposal conditions. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2012, 324, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ye, J.; Li, M.; Pan, L.; Zhang, Y. Investigation of the law of natural gas phase behavior during the migration and reservoir formation. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 8013034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvam, O.; Sarkisov, L. Solubility prediction in mixed solvents: A combined molecular simulation and experimental approach. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2019, 484, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Han, C.; Yu, L.; Wang, Y.; Gao, X.; Yang, K.; Zhang, L. Solubility of H2S-CH4 mixtures in calcium chloride solution: Insight from molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 407, 125225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.H.; Zhang, T.; Sun, S.Y.; Gong, L. Ab initio insights into the CO2 adsorption mechanisms in hydrated silica nanopores. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 313, 121741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, T.D.; Smith, N.O.; Nagy, B. Solubility of natural gases in aqueous salt solution nitrogen in aqueous NaCl at high pressures. Geochim. Cosm. Acta 1966, 30, 617–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, J.R.; Smith, N.O.; Nagy, B. Solubility of natural gases in aqueous salt solutions—I: Liquids surfaces in the system CH4-H2O-NaCl2-CaCl2 at room temperatures and at pressures below 1000 psia. Geochim. Cosm. Acta 1961, 24, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.O.; Kelemen, S.; Nagy, B. Solubility of natural gases in aqueous salt solutions—II: Nitrogen in aqueous NaCl, CaCl2, Na2SO4 and MgSO4 at room temperatures and at pressures below 1000 psia. Geochim. Cosm. Acta 1962, 26, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zhou, J.P.; Xian, X.F.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Lu, Z.; Yin, H. Gas adsorption characteristics changes in shale after supercritical CO2-water exposure at different pressures and temperatures. Fuel 2022, 310, 122260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Huang, Z. Experiments of methane gas solubility in formation water under high temperature and high pressure and their geological significance. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2017, 64, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zheng, D.Q.; Guo, T.M. Solubilities of methane, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and a natural gas mixture in aqueous sodium bicarbonate solutions under high pressure and elevated temperature. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1997, 42, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.K.; Sun, B.J.; Sun, X.H.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Peng, Y. Prediction method for methane solubility in high-temperature and high-pressure aqueous solutions in ultra-deep drilling. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 223, 211522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabipour, N.; Qasem, S.N.; Salwana, E.; Baghban, A. Evolving LSSVM and ELM models to predict solubility of non-hydrocarbon gases in aqueous electrolyte systems. Measurement 2020, 164, 107999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neisani Samani, N.; Miforughy, S.M.; Safari, H.; Mohammadzadeh, O.; Panahbar, M.H.; Zendehboudi, S. Solubility of hydrocarbon and non-hydrocarbon gases in aqueous electrolyte solutions: A reliable computational strategy. Fuel 2019, 241, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhaei-Kohani, R.; Taslimi-Renani, E.; Hadavimoghaddam, F.; Mohammadi, M.-R.; Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. Modeling solubility of CO2-N2 gas mixtures in aqueous electrolyte systems using artificial intelligence techniques and equations of state. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoghi, A.T.; Feyzi, F.; Zarrinpashneh, S.; Alavi, F. Solubility of light reservoir gasses in water by the modified Peng-Robinson plus association equation of state using experimental critical properties for pure water. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2011, 78, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A.; Amar, M.N.; Soltanian, M.R.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, X. Modeling CO2 solubility in water at high pressure and temperature conditions. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 4761–4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guang, W.F.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Zhang, L.; Ranjith, P.; Hao, S.; Liu, X. Confinement effect on transport diffusivity of adsorbed CO2-CH4 mixture in coal nanopores for CO2 sequestration and enhanced CH4 recovery. Energy 2023, 278, 1873–6785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Jiang, B.; Lan, F.J. Competitive adsorption of CO2/N2/CH4 onto coal vitrinite macromolecular: Effects of electrostatic interactions and oxygen functionalities. Fuel 2019, 235, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.L.; Wang, E.Y.; Chen, Y.X. Laboratory experiments of CO2-enhanced coalbed methane recovery considering CO2 sequestration in a coal seam. Energy 2023, 262, 23–38, 125473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhima, A.; De Hemptinne, J.C.; Jose, J. Solubility of hydrocarbons and CO2 mixtures in water under high pressure. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1999, 38, 3144–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, P.R.; Lee, H.H.; Keffer, D.J.; Lee, C.-H. Statistical mechanic and machine learning approach for competitive adsorption of CO2/CH4 on coals and shales for CO2-enhanced methane recovery. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.H.; Huang, B.J. Characteristics and accumulation mechanisms of the Dongfang 13-1 high temperature and overpressured gas field in the Yinggehai Basin, the South China Sea. Sci. China-Earth Sci. 2014, 57, 2799–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taggart, I. Extraction of dissolved methane in brines by CO2 injection: Implication for CO2 sequestration. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2010, 13, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, P. The potential of coupled carbon storage and geothermal extraction in a CO2-enhanced geothermal system: A review. Geotherm. Energy 2020, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.B.; Wang, S.R.; Wei, G.M.; Wang, H.; Zhao, H.; Liang, R. The seepage driving mechanism and effect of CO2 displacing CH4 in coal seam under different pressures. Energy 2024, 293, 130740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.B.; Sun, X.D.; Zhao, K.K.; Lei, C.; Wen, H.; Ma, L.; Shu, C.-M. Deformation mechanism and displacement ability during CO2 displacing CH4 in coal seam under different temperatures. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2022, 108, 104838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Cao, J.; Luo, J.; Li, S.; Wu, S.; Dai, L.; Hou, J.; Mao, Q. Heterogeneity and influencing factors of marine gravity flow tight sandstone under abnormally high pressure: A case study from the Miocene Huangliu formation reservoirs in LD10 area, Yinggehai Basin, South China Sea. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2021, 48, 1048–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.F.; Song, R.Y.; Pei, J.X.; Wu, Q.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, W. CO2 fluid flow patterns near major deep faults: Geochemical and 3D seismic data from the Ying-Qiong basin of the south China sea. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 9962343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Heinemann, N.; Liu, J.; Zhu, W.; Wilkinson, M.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wen, T.; Hao, F.; Haszeldine, R.S. CO2 sequestration by mineral trapping in natural analogues in the Yinggehai basin, south China sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 104, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtaba, M.; Ali, S.; Abaee, M.S. Experimental study on solubility of CO2 and CH4 in the ionic liquid 1-benzyl-3-methylimidazolium nitrate. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2023, 2, 105963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longe, P.O.; Danso, D.K.; Gyamfi, G.; Tsau, J.S.; Alhajeri, M.M.; Rasoulzadeh, M.; Li, X.; Barati, R.G. Predicting CO2 and H2 Solubility in Pure Water and Various Aqueous Systems: Implication for CO2-EOR, Carbon Capture and Sequestration, Natural Hydrogen Production and Underground Hydrogen Storage. Energies 2024, 17, 5723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.N.; Li, R.; Ma, J.; Jiang, P. CO2 Exsolution from CO2 Saturated Water: Core-Scale Experiments and Focus on Impacts of Pressure Variations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 14696–14703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lin, R.Y.; Pan, Y.; Sun, L.; Tang, Y. Experimental analysis and numerical simulation of the stability of geological storage of CO2: A case study of transforming a depleted gas reservoir into a carbon sink carrier. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 34832–34841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.F.; Song, X.H.; Li, X.Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Wei, J.; Zhang, M. Supercritical CO2 injection-induced fracturing in longmaxi shales: A laboratory study. Energies 2025, 18, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.S.; Wang, Y.B.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y. CO2 replacing CH4 behaviors and supercritical conditions. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 4353–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.L. Solubility and Exsolution Study of CO2 and CH4. Ph.D. Dissertation, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.J.; Sang, S.X.; Duan, P.P.; Zhang, J.-C.; Xiang, W.-X.; Xu, A. The effect of the density difference between supercritical CO2 and supercritical CH4 on their adsorption capacities: An experimental study on anthracite in the Qinshui Basin. Pet. Sci. 2022, 19, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, A.; Sartape, R.; Rojas, T.; Dandu, N.K.; Dhakal, P.; Thorat, A.S.; Xie, J.; Bessa, I.; Galante, M.T.; Andrade, M.H.S.; et al. Migration-assisted, moisture gradient process for ultrafast, continuous CO2 capture from dilute sources at ambient conditions. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, M.V.; Bushmin, S.A. Separation of Salts NaCl and CaCl2 in Aqueous-Carbon Dioxide Deep Fluids. Petrology 2024, 32, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynov, S.B.; Porter, R.T.J.; Mahgerefteh, H. Henry’s Law Constants and Vapor-Liquid Distribution Coefficients of Noncondensable Gases Dissolved in Carbon Dioxide. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 8777–8788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blath, J.; Christ, M.; Deubler, N.; Hirth, T.; Schiestel, T. Gas solubilities in room temperature ionic liquids—Correlation between RTiL-molar mass and Henry’s law constant. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 172, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ion Type | Na+ + K+ | Mg2+ | Ca2+ | Cl− | SO42− | HCO3− | Total Salinity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ion Content (mg/L) | 4884 | 6 | 3 | 2177 | 121 | 7100 | 14,848 |

| Well | Layer | Pressure (MPa) | Temperature (K) | CH4 | CO2 | Cl− (mg/L) | Solubility (m3/m3) | Proportion of Solution Gas (%) | Gas Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD10-X-10 | H2IV | 87.079 | 468.42 | 27.05 | 70.98 | 5000 | 47.6 | 0.54 | free gas |

| LD10-X-12 | H2V | 93.985 | 488.35 | 53.01 | 42.93 | 5400 | 41.25 | 100 | solution gas |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, J.; Liang, H.; Li, G. Solubility and Exsolution Behavior of CH4 and CO2 in Reservoir Fluids: Implications for Fluid Compositional Evolution—A Case Study of Ledong 10 Area, Yinggehai. Processes 2025, 13, 2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13092979

Liao J, Liang H, Li G. Solubility and Exsolution Behavior of CH4 and CO2 in Reservoir Fluids: Implications for Fluid Compositional Evolution—A Case Study of Ledong 10 Area, Yinggehai. Processes. 2025; 13(9):2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13092979

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Jin, Hao Liang, and Gang Li. 2025. "Solubility and Exsolution Behavior of CH4 and CO2 in Reservoir Fluids: Implications for Fluid Compositional Evolution—A Case Study of Ledong 10 Area, Yinggehai" Processes 13, no. 9: 2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13092979

APA StyleLiao, J., Liang, H., & Li, G. (2025). Solubility and Exsolution Behavior of CH4 and CO2 in Reservoir Fluids: Implications for Fluid Compositional Evolution—A Case Study of Ledong 10 Area, Yinggehai. Processes, 13(9), 2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13092979