Abstract

Wine and food tourism has increasingly embraced the principles of the circular economy and sustainability. During the bottle-fermented production of sparkling wine, yeast encapsulated in calcium alginate beads gradually loses viability. After the secondary alcoholic fermentation, these beads are usually discarded. This pilot-scale study investigates how the wasted beads can be valorised by incorporating them into vegan vinaigrettes. The vegan vinaigrettes were developed on a laboratory scale with distinct flavour profiles, all containing 3.5% (w/w) calcium alginate beads: mint (V-Air), seaweed (V-Water), spicy (V-Fire) and mushroom (V-Earth). Forty untrained panellists assessed the samples on a nine-point hedonic scale and with Just-About-Right (JAR) scale. Viscosity and colour were also measured in the final samples. Vf-Fire and Vf-Earth vinaigrettes stood out in terms of overall appreciation, particularly colour and consistency, with Vf-Earth receiving the highest average score (7.10 ± 1.58). The presence of alginate beads was well appreciated, with an average score of 6.26 ± 2.14. Across all formulations, the average pH decreased from 3.75 ± 0.01 to 3.37 ± 0.01. This pH reduction benefits food safety. These vegan vinaigrettes offer a sustainable and innovative alternative for reusing sparkling winemaking waste as a by-product, with strong potential for gastronomic appeal among wine or food tourists.

1. Introduction

The evolution of gastronomy has been driven by a constant quest for creativity and adaptation to emerging trends such as sustainability and the circular economy. This has led to a greater emphasis on maximising the value of food by-products [1]. Gastronomic valorisation helps reduce food waste and contributes to environmental sustainability, economic growth and cultural innovation in the food sector. Although this approach may seem modern, it revives traditional domestic economy practices. These practices are adapted to current challenges of overproduction, excessive consumption and their environmental impacts [1,2]. In this context, collaboration between chefs, academia, and entrepreneurs has been essential in optimising the use of underutilised ingredients. This joint effort has also played a key role in convincing the population to adhere to this trend, transforming these ingredients into new, high-value resources or products [2].

For example, in Spain, the Wine Routes project has served not only as a tourism enhancer but also as a policy instrument for local development. Empirical studies indicate that wine tourism can foster sustainable growth in rural areas by enhancing local identity and increasing regional income, despite limited evidence of employment gains. These findings are consistent with broader sustainable development frameworks in rural economies. Within these frameworks, the integration of circular practices into industries such as gastronomy and wine production has shown potential for revitalising underexplored resources and territories [3].

Through the lens of economic, social, cultural, environmental and political affairs, wine tourism can, therefore, emerge as a sustainability driver for the wine industry due to its capacity to improve business performance and environmental awareness and to enhance community values and relations network [4]. Wine Routes are privileged tools for organising and promoting wine tourism [5]. These are tourist itineraries that highlight the wine regions of the country, allowing visitors to explore wine-producing areas, taste local wines, learn about the wine production process and enjoy local culture and cuisine concerning the wines of each region.

Currently, in Portugal, there are 31 Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), and 14 Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) distributed across 14 wine regions: Vinhos Verdes, Trás-os-Montes, Douro, Távora-Varosa, Dão, Bairrada, Beira Interior, Lisbon, Tejo, Península de Setúbal, Alentejo, Algarve, Madeira and Azores. The Bairrada region, a wine-producing Appellation of Origin in Portugal, is the country’s largest producer of sparkling wines [6].

The specificity of food and wine in a particular region can serve as a motive that connects consumers to a particular geographic area [7]. Associating local gastronomy with wines, i.e., oenogastronomy, contributes to enhancing the identity and competitiveness of destinations. In fact, oenogastronomy is an important factor related to the development of wine tourism [8].

The use of immobilised yeasts for the second fermentation of sparkling wines can reduce and simplify some oenological practices, such as riddling and disgorging [9]. During the secondary fermentation of sparkling wine, encapsulated yeasts in calcium alginate beads can be used to aid the remuage process. After disgorgement, the yeast cells lose cellular viability and, for this reason, the alginate beads are discarded for wastewater treatment. Despite their widespread use in sparkling wine production, the potential for reusing these beads has been largely overlooked. Exploring innovative strategies to repurpose this material adds value to an underutilised waste product. Moreover, it contributes to broader sustainability goals within the wine industry, aligning with circular economy principles and helping to reduce environmental impact.

During the 2023/24 production cycle, at least 37,460 hL of sparkling wine were produced in Bairrada [6] and part of it was made with beads. Given the edibility of the calcium alginate beads and their established use in molecular gastronomy [9], calcium alginate beads represent a winery waste with unexplored gastronomic potential. Innovative valorisation of wine-related by-products, as explored in this study, may offer a scalable response to the need for added value [10] and product diversification within wine tourism initiatives, an element highlighted as critical for long-term sustainability in comparable European regions [3].

In this context, the development of gastronomic products that complement or evoke the sensory universe of wine, particularly those used in food pairings or tasting experiences, has gained increasing relevance [11]. Among such products, vinaigrettes stand out for their versatility and could by easily used within wine-focused dining experiences. Typically composed of oil and vinegar (thus forming an emulsion), vinaigrettes provide an adaptable matrix for innovation, often enhanced with herbs, spices, or other ingredients. Beyond their common use as salad dressings, they also function as cold sauces or marinades, offering multiple avenues for creative integration into wine tourism experiences [12].

In the literature, studies focused on vinaigrettes are scarce. Despite this, research on the physico-chemical and rheological properties of mustard-based vinaigrette salad dressings was conducted by Lozano-Gendreau and Vélez-Ruiz [13]. Various formulations were analysed over a four-week storage period, assessing factors such as acidity, emulsion stability and flow behaviour. Additionally, a study on recipes and consumer acceptance of vinaigrettes with uvilla (Physalis peruviana L.) was published by Cadena and Coyago [14].

The following key points summarise the objectives and contributions of this study regarding the development of innovative vinaigrettes using calcium alginate beads:

- The study introduces an innovative approach to vinaigrette formulation by integrating calcium alginate beads, supporting circular economy and food sustainability.

- Calcium alginate beads, a by-product of sparkling wine production, are repurposed into value-added ingredients for vegan vinaigrettes.

- Exploratory consumer research is conducted to evaluate consumer acceptance of the developed vinaigrettes.

- The purposed approach promotes waste reduction and aligns with circular economy principles.

- It also opens new opportunities for product development in wine and food tourism, particularly in the Bairrada region and other wine-producing areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of the Vinaigrettes

The total amount of 600 g of calcium alginate beads was collected immediately after the disgorgement of sparkling wine bottles, with careful separation from the metal caps and bidules.

The alginate beads were frozen and stored at −20 ± 2 °C until the moment of their use. The alginate beads were tested under different conditions to assess their sensory characteristics and determine possible applications in products. When tasted immediately after defrosting, both submerged and not submerged in water, they exhibited a slightly firm texture and an acidic flavour resulting from the sparkling wine. However, after remaining outside the aqueous medium for just one hour, the texture exhibited a noticeable decline in palatability. It became excessively hard to bite into, a characteristic even more pronounced following oven-induced dehydration. When boiled for thirty minutes, provided they remained in the liquid medium, beads maintained properties like those of non-boiled submerged samples. Based on this, it was concluded that the ideal product would need to have relatively liquid consistency to preserve the best characteristics of the beads. This is also important because choosing uncooked beads is a more sustainable production choice.

The goal of our work was to repurpose beads into a new product, to prevent winery waste. In fact, the primary goal is to create a new, sensory-acceptable product with the contribution of the beads. To achieve this goal, the beads should have been processed to maintain their sensory characteristics, such as visual appearance, acidity and texture. The matrix vinaigrette was chosen as it aligned with the objective: vinaigrettes are sauces with a liquid texture, typically containing suspended ingredients, like mustard seeds or aromatic herbs. By applying the same suspension strategy, the beads can be appreciated for their visual appearance and texture.

Subsequently, the aim was to create vinaigrette formulations distinct from those available on the market and appealing to consumers, particularly wine and food tourists. Therefore, a concept was developed to create a line of four vinaigrette sauces inspired by the four elements of nature (Figure 1). For the vinaigrette inspired by the air element, a mint flavour was chosen to evoke the fresh perception of the natural breeze (V-Air), the water element vinaigrette with a seaweed flavour (V-Water), the fire vinaigrette with a spicy flavour (V-Fire) and the earth element vinaigrette with a mushroom flavour (V-Earth) [10]. This innovative vinaigrette concept is grounded in the sensory association of the four classical elements—air, water, fire and earth—with specific flavour profiles, offering a multi-sensory experience that is currently absent in commercial vinaigrettes. By aligning each element with a representative ingredient (mint, seaweed, chilli and mushroom), the formulations aim to evoke distinct perceptual responses linked to nature-inspired stimuli.

Figure 1.

The four vegan vinaigrettes: Vf-Air, Vf-Water, Vf-Earth and Vf-Fire.

The ingredients used in the formulations were sourced from commercially available products, ensuring consistency across all formulation trials. To develop the proposed new vinaigrette sauces with alginate beads suspended in the sauce, various tests were conducted, experimenting with different formulations and varying ingredient quantities. Each trial was assessed to refine the recipes, aiming to achieve products with desirable organoleptic properties. The infusions were prepared one day before the vinaigrette formulation and in the case of the final version of the formulations.

Before preparing the vinaigrettes, the infusions whose ingredients and proportions are presented in Table 1 were prepared with the following steps:

Table 1.

Infusion formulation in different liquid media for each initial (Vi) and final (Vf) vinaigrettes.

- The liquid medium of the infusion was heated to 40 °C;

- Subsequently, the respective ingredients were added and kept in contact with the liquid medium for 30 min;

- After this period, the mixture was blended to obtain a more homogeneous composition;

- Exceptionally, the V-Air sample was infused for only 2 min. This infusion was strained instead of blended, as prolonged exposure to mint leaves resulted in a bitter taste and unpleasant texture.

Once the infusions preparation was completed, the vinaigrette formulations were prepared, whose ingredients and quantities are described in Table 2. For each vinaigrette, all premeasured ingredients were added simultaneously (except the calcium alginate beads) into a blender; each mixture was processed until proper emulsification was achieved and complete hydration of the xanthan gum was ensured.

Table 2.

First (Vi) and final (Vf) versions of the four vinaigrette formulations.

Finally, beads were added to the vinaigrettes. Specifically, for every 100 g of vinaigrette, an additional 4 g (+4% w/w) of alginate beads were incorporated in the initial formulations, and 3.5% (w/w) in the final formulations.

After several tests to understand the organoleptic characteristics of the basic vinaigrette proportions (water, oil, vinegar), how to infuse the intended ingredients in these liquid media according to their matrix and the hydration of xanthan gum, the first version of each vinaigrette formulation (Vi) was established, as shown in Table 2, along with the final version (Vf). Xanthan gum is a useful ingredient in salad dressings, such as vinaigrettes for its ability to emulsify, thicken and stabilise the consistency. It helps prevent separation of oil and vinegar, suspends solids like herbs and spices and creates a smooth texture [15,16]. The samples Vi and Vf were performed in triplicate and stored in sterilised glass jars in the refrigerator (6 ± 2 °C) until analysis.

2.2. Physicochemical Analysis

The pH of the vinaigrette samples was determined using a potentiometer (Hach Sension + pH3, Hach Company, Loveland, CO, USA), following the International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV) method OIV-MA-AS313-15, traditionally used for wine analysis, as well as the titratable acidity, which was assessed using the titrimetric method, following the OIV method OIV-MA-AS313-01.

The viscosity of the samples was measured using a rotational viscometer (Brookfield, Model DV-E, AMETEK, Middleboro, MA, USA) at a controlled temperature of 16.35 ± 0.90 °C. This temperature was chosen because it is closest to the tasting temperature in sensory analysis. The viscosity measurements were performed at a constant shear rate of 10 rpm for 15 s, ensuring stabilisation before recording the final value.

The CIELAB L*a*b* and CIE L*C*h° colour spaces were used to evaluate the colour of the samples. It includes the lightness coefficient L* (ranges from black = 0 to white = 100), a* (position on the red–green axis, with positive values indicating redness and negative values indicating greenness), and b* (position on the yellow–blue axis, with positive values indicating yellowness and negative values indicating blueness). From these, the derived parameters C* (chroma, indicating colour saturation or intensity) and h° (hue angle, expressed in degrees, red-purple = 0°; yellow = 90°; bluish-green = 180°; blue = 270°) were obtained [17,18]. These measurements were carried out using a colourimeter (model CR200b, Minolta Corp., Ramsey, NJ, USA).

2.3. Sensory Evaluation

The hedonic sensory analysis aimed to evaluate the acceptance and preference of the final formulations of the four vinaigrettes, with the goal of understanding whether the vinaigrettes containing beads have market potential.

For this research, data protection measures were implemented to ensure compliance with European legal regulations. This study received prior approval from the Ethics Committee of the Polytechnic University of Coimbra (approval reference: D36/2024) on 25 September 2024. Written informed consent was obtained from all volunteers participating in the sensory analysis.

Samples were evaluated by the panel members according to the principles and methodologies outlined in the following ISO standards for sensory analysis: ISO 4121:2003, ISO 5492:2008, ISO 11136:2014 and ISO 6658:2017 [19,20,21,22].

An exploratory consumer study was carried out involving a sensory panel composed of 40 untrained assessors, with ages ranging from 17 to 60 years (mean age = 26.5 years). Age information was not disclosed by 5% of the participants (n = 2). In terms of gender distribution, 47.5% identified as male (n = 19), 42.5% as female (n = 17), 2.5% identified as other (n = 1) and 5% chose not to report their gender (n = 2). Among the participants, 65% (n = 26) reported regular consumption of vinaigrette sauce, whereas 35% (n = 14) indicated that they did not consume it regularly. Regarding the perception of the beads in the samples, 85% (n = 34) of the assessors reported detecting their presence, 12.5% (n = 5) did not perceive them and 2.5% (n = 1) did not provide a response.

During the sensory evaluation, a small number of untrained participants did not provide responses to one or more questions, despite being instructed to complete all items before tasting the samples. This type of missing data is not uncommon in studies involving untrained assessors, particularly when multiple sensory attributes are assessed or when the evaluation process is unfamiliar. These instances were recorded and accounted in the analysis, highlighting a real-world aspect of consumer testing where occasional non-responses may occur despite clear instructions.

The four samples were assigned random 3-digit codes before being presented to the tasters, who were unaware of the type of vinaigrette or its formulation.

To ensure that the tasting experience was as consistent as possible among the tasters, it was necessary to taste the vinaigrettes in their pure form. However, due to the structure of their formulation and to reduce microbiological risks, the vinaigrettes contained a considerable amount of vinegar.

There is no specific ISO standard that defines an exact tasting temperature exclusively for vinaigrettes. For example, ISO 11136:2014 recommends that products should be evaluated at the temperature at which they are typically consumed, to ensure realistic and reliable sensory analysis. Consequently, the samples were served at 16 ± 1 °C, not too cold, to minimise the impact of high acidity on the sensory evaluation.

On the tasting sheet, the tasters were instructed to sample the vinaigrettes from left to right, taking small amounts with a spoon and cleansing their palate with a toast between each sample.

In the first part of the sensory test, the tasters evaluated each attribute of the vinaigrettes on a structured hedonic scale from 1 to 9, where 1 corresponded to “dislike very much” and 9 to “like very much”. The evaluated attributes included colour, visual appearance, aroma intensity, flavour intensity, flavour balance, consistency, presence of calcium alginate beads and overall appreciation.

The next part included a preference test, where subjects were asked to indicate their preferred sample and provide a brief explanation of their choice. A purchase intention assessment was also performed and the procedure was previously described [10].

Finally, the subjects were asked to rate, on a JAR scale from 1 to 5 (1 = too weak, 2 = weak, 3 = just right, 4 = strong and 5 = too strong), how closely each sample matched the ideal final flavour.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative results were expressed as Mean ± SD (standard deviation) or percentage (%). Data processing and analysis, including Student t-test, one-way analysis of variance ANOVA (p < 0.05) and post hoc Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05), were performed using the Real Statistics Resource Pack version Rel 9.5.5 (released 21 June 2025) in Microsoft® Excel® 365 (version 2505).

3. Results

3.1. Analytical Characterisation of the Initial and Final Vinaigrettes

The results presented in Table 3 indicate that the pH values of the Vi samples ranged from 3.46 ± 0.01 (Vi-Fire) to 3.88 ± 0.01 (Vi-Earth), demonstrating a slightly acidic profile typical of vinaigrette products. In the Vf formulations, the pH values varied between 3.20 ± 0.01 (Vf-Fire) and 3.58 ± 0.01 (Vf-Earth), reflecting an overall lower pH range in the improved formulations.

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties of vinaigrette samples in initial (Vi) and final (Vf) formulations, including pH, titratable acidity and viscosity.

Regarding titratable acidity, the Vi samples showed values between 0.41% (Vi-Air) and 0.62% (Vi-Water), where the Vf samples displayed higher acidity levels, with the Vf-Water sample reaching 1.05%. These findings indicate a relevant increase in acidity across the enhanced formulations.

Viscosity measurements were only recorded for the Vf samples, ranging from 2.10 ± 0.21 mPa·s (Vf-Earth) to 7.35 ± 0.07 mPa·s (Vf-Water). This range suggests that the samples exhibit differences in viscosity, which may be perceptible to the tasters during the sensory evaluation.

Table 4 shows the CIELAB colour coordinates (L*, a*, b*) and derived parameters (C* and h°) for the four samples analysed. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 10), corresponding to five measurements from each of two independently prepared duplicates per sample.

Table 4.

Colour determination (CIELAB colour space) of final vinaigrettes ( ± SD) (n = 10).

Among the samples, Vf-Fire exhibited the highest values of L*, b*, C* and h°, indicating a lighter and more saturated yellow hue, while Vf-Water showed the lowest L* and h° values, suggesting a darker appearance. The samples that showed the greatest heterogeneity, as indicated by higher standard deviations, were primarily Vf-Earth, followed by Vf-Water. In contrast, Vf-Fire demonstrated the lowest standard deviation values, reflecting greater homogeneity in b* coordinate and h° angle. Moreover Vf-fire showed the highest intensity colour with C* of 26.10 and the lowest one was observed in Vf-Air, with only 6.90 average chroma.

3.2. Sensorial Analysis of the Final Vinaigrette Samples

Each of the four vinaigrette samples was assigned a unique code, which was used to identify the sample on the corresponding sensory test score sheet. The following attributes were evaluated on a hedonic nine-point scale: colour, visual appearance, aroma intensity, flavour intensity, flavour balance, consistency, presence of beads and overall appreciation. The higher the value used on the scale, the greater the liking of that attribute by the tasters. Table 5 presents the scores (average ± standard deviation) given by the tasters for the final four formulations.

Table 5.

Hedonic characterisation of the final vegan vinaigrettes formulations ( ± SD) (n = 40).

Vf-Fire has the highest average score for colour (7.60) and visual appearance (7.30), suggesting it is the most visually appealing. On the other hand, Vf-Water ranks lowest in both categories. Vf-Fire has the highest flavour intensity (6.72), followed by Vf-Earth (6.45), while Vf-Air has the lowest (5.95). This result suggests that Vf-Fire may evoke a stronger gustatory response. Flavour balance average scores are relatively uniform, with Vf-Earth ranking highest (6.53), indicating a more harmonious flavour perception, however without significant statistical difference. Aroma intensity was higher in Vf-air and lower in Vf-Water. This result can be explained by the presence of mint in Vf-air which present a natural strong aroma intensity.

Vf-Fire and Vf-Earth exhibit higher hedonic appreciation of consistency (6.92 and 6.80 mean scores, respectively). According to the comments, tasters found the V-Air sample to be the least consistent, while the V-Water sample was found to be excessively consistent. Nevertheless, no statistically significant differences were found among the four vegan vinaigrettes (p > 0.05).

The appreciation about the presence of beads varies slightly, with Vf-Earth (6.59) and Vf-Air/Water (6.22 and 6.20, respectively) showing slight differentiation between them. Some tasters reported that they did not feel the presence of the beads in some of the samples, despite all the vinaigrettes containing the same amount of alginate beads.

Vf-Earth (7.10) and Vf-Fire (6.95) received the highest overall appreciation scores, likely due to their stronger colour, flavour and consistency attributes. Vf-Air and Vf-Water scored lower, possibly because of their milder sensory characteristics. A statistically significant difference was found between Vf-Water and Vf-Earth (p < 0.05), attributed to the higher average appreciation of Vf-Earth.

It can be concluded that the Vf-Fire and Vf-Earth samples outperform the Vf-Air and Vf-Water samples across most sensory attributes, particularly in visual appearance, flavour intensity and overall appreciation.

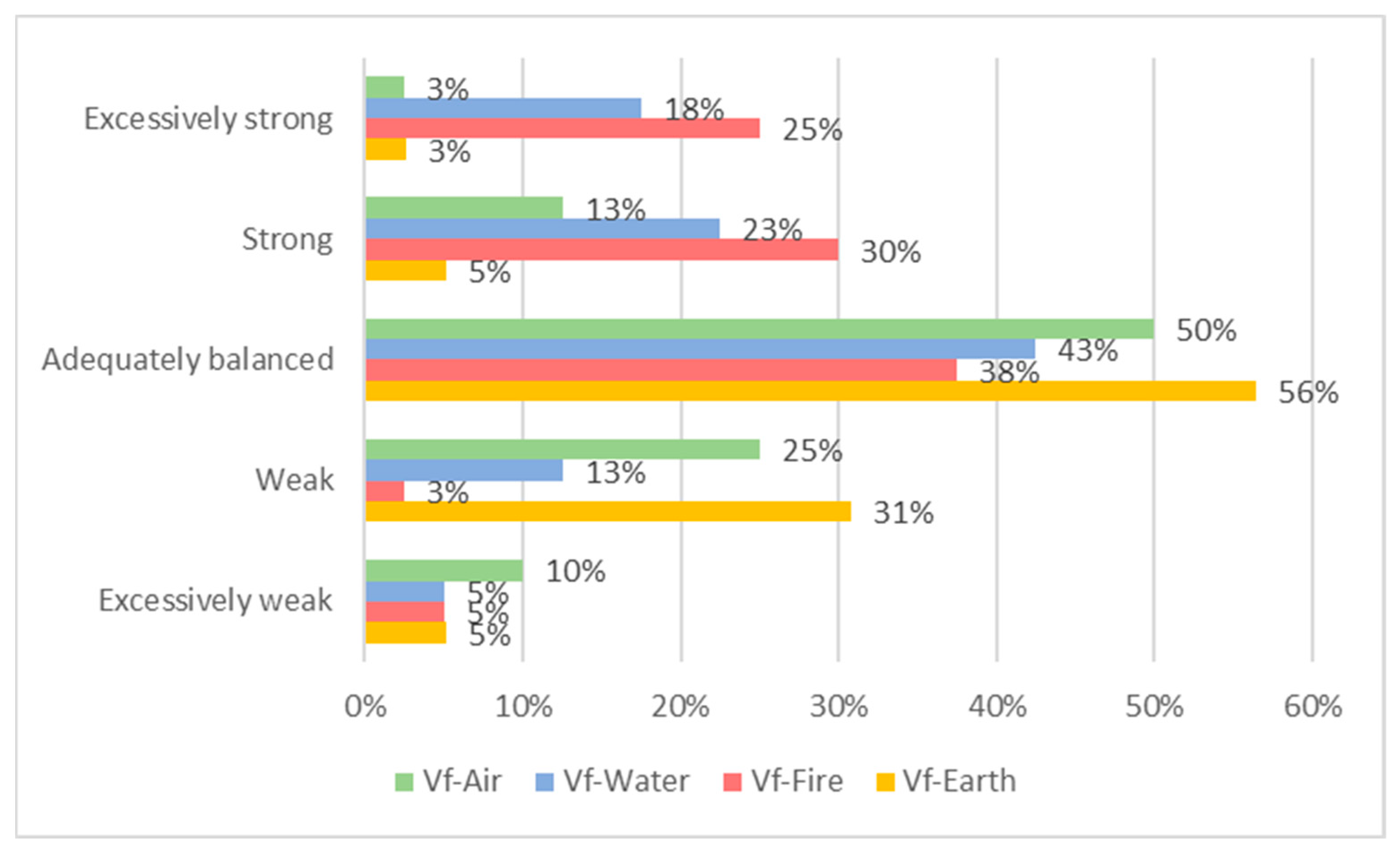

Figure 2 reflects how each vinaigrette variant (Vf-Air, Vf-Water, Vf-Fire, Vf-Earth) aligns with an “ideal” intensity level. The categories range from “Excessively weak” to “Excessively strong”, with “Adequately balanced” representing the ideal target.

Figure 2.

Perception of flavour intensity balance of the four final vinaigrette formulations.

Vf-Earth showed the highest “Adequately balanced” scores, suggesting the most perceived V-Earth as the closest to the ideal intensity. Very low counts in “Excessively weak” or “Excessively strong” indicate that it avoids extremes and meets consumer expectations well.

Vf-Fire revealed notable proportions in “Strong” and “Excessively strong”, implying that this variant’s intensity may be too high for some consumers (Figure 2). A moderate number of responses also fall in “Adequately balanced”, indicating that opinions are somewhat divided—some find it suitably robust, while others see it as overpowering.

Vf-Air exhibits a mix of “Weak”, “Strong”, and “Adequately balanced” ratings, suggesting an inconsistent perception. Higher levels in “Strong” than in “Excessively strong” may indicate that, while potent for some, it is not overwhelmingly intense for most participants.

Finally, Vf-Water ranked in 3rd position with 43% of answers in “Adequately balanced”, option.

In summary, these findings suggest that Vf-Earth is the most appealing in terms of intensity balance, whereas Vf-Fire skews toward a bolder flavour profile that some may find excessive. Vf-Water is generally perceived as “strong” or “excessively strong” and Vf-Air occupies the positions of “adequately balanced” (second position, just below Vf-Earth) and the second position in “weak flavour”

The hedonic sensory evaluation of the vinaigrette samples revealed varying preference levels among the tasters, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Tasters’ preferences and reasons for selection.

The Vf-Earth sample was the most preferred, with 37.5% of the panel selecting it as their favourite. The primary reasons cited included its “fresh mushroom flavour”, which was described as “evident and well balanced”, alongside its “excellent consistency”. Tasters also appreciated the sample’s balanced intensity and the harmony between consistency and flavour. Additionally, some participants mentioned its familiar appearance and the well-integrated presence of the alginate beads.

The Vf-Fire sample followed closely, garnering 32.5% preference. It stood out for its spiciness, with tasters highlighting the “attractive colour” and the appealing “small red spots” that contributed to its visual appeal. The flavour was noted as “soft and spicy, with a pleasant ginger note”, and it was described as “exciting to eat”. Tasters also praised its consistency and how the spiciness enhanced the overall sensory experience.

The Vf-Water sample received 15% preference. The tasters appreciated its “pleasant mix of flavours and consistency”, specifically praising the “sea and seafood flavour” that effectively matched the intended taste profile. Some commented positively on how the flavour paired well with the toast, contributing to a balanced taste experience.

Finally, the Vf-Air sample was the least preferred, with 12.5% of the tasters selecting it. Despite the lower preference, it was noted for having a “balanced flavour, identifiable with the type of product, vinegary flavour” and for presenting a “traditional look” that some tasters found appealing. It was also mentioned that the flavour was “milder and easier on the palate, as the reason for preference.

It is worth noting that some tasters commented that the seaweed vinaigrette could have a milder flavour and that the spicy vinaigrette could be less intense. Additionally, others suggested possible pairings or applications, such as in salads, on bread, or as an accompaniment to chips and meat. One tester recommended the spicy sauce with a prawn and mango salad, while another mentioned that the mushroom sample was more versatile for different combinations.

Overall, the preference analysis highlighted distinct sensory attributes driving consumer choice, with balance, consistency and flavour intensity being critical factors influencing the tasters’ decisions.

4. Discussion

Food is a key factor in tourism activity [23]. Nowadays, innovative food and authentic culinary experiences are aspects of promotion to attract tourists.

As a food innovation concept, we decided to relate the formulations of each vinaigrette with the ancient concept of four elements: air, water, earth and fire. According to Habashi [24], the concept of four elements (air, water, earth and fire), consistently mentioned in history of chemistry books as due to Greek philosophers, is shown to have a much older origin and a different meaning. In fact, according to this author, two centuries before Aristotle, the Persian philosopher Zoroaster described these four elements as “sacred”, i.e., essential for the survival of all living beings and, therefore, should be venerated and kept free from any contamination. Later, Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) added to this concept that the properties of substances result from the simultaneous presence of certain fundamental properties. The Aristotelian doctrine was therefore concerned not with what modern chemists call elements but with an abstract conception of certain contrary properties or “qualities”, especially coldness, hotness, dryness and moistness, which may be united in four combinations: dryness and heat (fire), heat and moisture (air), moisture and cold (water) and cold and dryness (earth) [24]. These four combinations were the inspiration for our work, with the four different profile recipes of the vinaigrettes: vinaigrette Fire—with the key character ingredients—piri-piri peppers, black pepper, smoked paprika, garlic and bay leaves to provide spicy and smoky flavour and burning sensation; vinaigrette Air with peppermint leaves to provide a fresh flavour, like the breeze of the wind; vinaigrette Water with dulse and sea lettuce seaweed to provide a salty and umami flavour, like the sea flavour; Vinaigrette Earth—with mushrooms and olive oil to provide umami flavour and earthy characteristics.

The formulation of vinaigrettes using by-products from sparkling wine presents an innovative approach to enhancing the value of waste generated by the wine industry, aligning with the principles of the circular economy [10]. As demonstrated by Dikel & Dikel [25] in the reuse of aquaculture waste in gastronomy, integrating these by-products into vinaigrette production not only reduces waste but also enhances flavour complexity and expands culinary applications.

Beyond its environmental benefits, incorporating sparkling wine by-products may enrich the sensory profile of vinaigrettes. This approach aligns with the concept of circular gastronomy, where waste is repurposed into valuable ingredients, driving both culinary innovation and resource efficiency. As highlighted by Dikel & Dikel [25], such initiatives strengthen the link between gastronomy and sustainability, encouraging more responsible practices without compromising quality or the dining experience.

Furthermore, the implementation of sustainability strategies in gastronomy, such as the valorisation of by-products, can benefit from collaborative initiatives that engage various sectors, including education and tourism, to promote more resilient food systems [2]. These practices reinforce cultural identity and support local economies by producing vinaigrettes from sparkling wine by-products sourced from local producers and using ingredients from national and, in some cases, regional brands. The result is a flavour profile that introduces innovative taste experiences compared to existing market offerings.

For every 770 bottles of sparkling wine produced, approximately 1 kg of alginate beads is generated as a by-product [26], highlighting its potential for large-scale reuse. When incorporated at 3.5% (w/w) in vinaigrette formulations (Table 2), this quantity of beads could yield around 28.5 litres of sauce or 143 packages of 200 g. Given this potential, exploring their application in food products is both environmentally and economically relevant.

In the present study, the initial formulations (Vi) were adjusted to lower concentrations of alginate beads (3.5% w/w) in the final versions (Vf), due to concerns about potential negative consumer perception. However, sensory results revealed that these concerns were unfounded. The final formulations received favourable appreciation scores for the presence of beads, especially Vf-Earth (6.59), followed by Vf-Air (6.22) and Vf-Water (6.20) (Table 5). In addition, some tasters even reported not perceiving the beads in certain samples, despite all formulations containing the same concentration (3.5% w/w). This suggests that the sensory impact of the beads may be influenced by other formulation factors, such as texture or flavour complexity.

Overall, the positive acceptance and occasional imperceptibility of the beads indicate that higher concentrations could be tested in future formulations, further enhancing the valorisation of this winemaking by-product in vinaigrette-type sauces.

According to Laranjeira et al. [27], a vinaigrette can be considered safe when it has a pH lower than 3.5, a parameter that further reinforces the microbiological stability of the product. After the initial formulation of the four vinaigrettes, subsequent adjustments were made to meet this pH recommendation. This led to the replacement of rice vinegar, which already had a mild flavour, with alcohol vinegar (Table 1 and Table 2). Despite its lower pH, alcohol vinegar provided a smoother organoleptic profile, allowing a higher vinegar concentration without masking the intended infusion flavours in the dressing. As can be seen in Table 3, the reformulation successfully lowered the pH of all samples, except for the V-Earth sample, which did not reach below 3.5, although it remained very close (3.58) and still within values considered safe for consumption.

The results obtained in this study are consistent with data in the literature, which indicate that sauces and vinaigrettes with a pH ≤ 4.4 and a minimum titratable acidity of 0.43% as acetic acid present sufficient toxicity to inhibit foodborne pathogens, due to the predominance of acetic acid and the intrinsically unfavourable conditions for microbial growth [28]. Therefore, although the initial reformulation based on Laranjeira et al. [27] was stricter than necessary, it proved advantageous by enhancing the sensory quality of the vinaigrettes, achieving a more pleasant flavour profile without compromising safety.

Furthermore, as shown in Table 3, all final samples presented titratable acidity levels exceeding 0.43%, complying with safety standards for analogous commercial formulations. Ribeiro [26] compared the Vi samples with three commercial vinaigrettes, which presented titratable acidity levels between 1.31% and 1.98% and pH values ranging from 2.99 to 3.34. Consequently, maintaining strict hygiene during sample preparation, ensuring a pH below 4.4 and achieving a titratable acidity above 0.43% as acetic acid should, in principle, be sufficient to guarantee microbiological safety under appropriate storage conditions and in the absence of post-processing contamination. Although the commercial vinaigrettes analysed by Ribeiro [26] exhibited lower pH values and higher titratable acidity levels than those obtained in this study, the formulated samples still meet the minimum microbiological safety criteria described in the literature. Despite the positive results achieved, the microbial analysis and shelf-life assessment of the vinaigrettes are planned to be addressed in future investigations.

On the other hand, a non-thermal treatment technology such as gamma irradiation may further enhance the microbiological safety of samples. According to Gallo et al. [29], commercial vinaigrette samples treated with gamma rays at doses of 3 kGy and 5 kGy showed no significant differences in pH or sensory acceptance, suggesting that gamma irradiation could be a promising complementary approach to reinforce product safety. Gamma irradiation is relatively sustainable when used for specific food preservation goals. It is not energy-free, but its energy use is concentrated in infrastructure and handling, not in the irradiation itself. It can be seen as part of a diversified food preservation strategy, especially where reducing waste is a priority.

Regarding viscosity, the Vf-Water and Vf-Fire samples exhibited the highest viscosity (Table 3), despite containing the lowest amount of thickener, with 0.21% and 0.23% xanthan gum, respectively. Conversely, the remaining samples displayed similar viscosities, significantly lower than that of the Vf-Fire sample, even with a higher thickener content, where the Vf-Air sample contained 0.33% xanthan gum and the Vf-Earth sample 0.40% (Table 2). As for the Vf-Water sample, which exhibited a higher viscosity discrepancy compared to Vf-Fire, it is important to highlight that the presence of dulse seaweed may have influenced this parameter, as it also acts as a thickening agent [30]. The fact that Vf-Fire was more viscous than the Vf-Earth and Vf-Air samples, despite V-Water containing a lower proportion of oil and olive oil as well as less thickener, may be attributed to the nature of the emulsion or to the possibility that the xanthan gum was not properly hydrated in those samples. Of all the samples, the consistency of Vf-Earth was the most appreciated, making it worthwhile to adjust the remaining formulations to achieve a consistency as similar as possible.

In terms of colour, the analysis of CIELAB L*a*b* and CIE L*C*h° coordinates and related parameters indicated significant variation between the samples (Table 4), with a focus on assessing the visual homogeneity of each formulation. The Vf-Earth and Vf-Water samples showed the highest standard deviations, confirming the initial expectation of greater heterogeneity due to the presence of visible particles, such as dulce seaweed in Vf-Water.

Although Vf-Earth appears to be visually homogeneous, it exhibited high standard deviations in the colour parameters, possibly due to its whitish tone, which enhances the contrast with the suspended alginate beads and makes minor variations more noticeable during measurement.

Vf-Air, which contains crushed mint, was also expected to be heterogeneous, yet it showed relatively low variation, possibly due to a more uniform distribution or lower chromatic contrast between the particles and the surrounding matrix. In contrast, Vf-Fire presented the highest values for L*, b*, C* and h°, along with the lowest variation among replicates, reflecting a high degree of homogeneity.

According to Ferreira [31], the heterogeneity of the sample directly influences the variability of colorimetric parameters. The study highlights that visible particles and variations in the food matrix accentuate differences in colour measurements, particularly in light-toned samples where even subtle contrasts become more noticeable. This accounts for the high variability observed in Vf-Earth and Vf-Water, likely due to the presence of dulse seaweed and alginate beads, which contribute to heterogeneity detected in the colourimetry analysis.

Food tourism offers an appealing opportunity to promote sustainable diets, as it attracts visitors to explore local food cultures, products and activities. It promotes the circular economy, which emphasises waste minimization and resource maximisation. Moreover, it benefits the economy and the environment, but faces challenges from new technologies and consumer preferences [32]. By this, the preferences assessment of vinaigrettes was crucial in our work.

The preference results (Table 6) highlighted the Vf-Earth (37.5% preference) and Vf-Fire (32.5%) samples as the most appreciated by the tasters, possibly due to their flavour intensity and consistency and despite the absence of significant statistical differences. Although all samples had the same content of alginate beads, some tasters indicated they did not notice the beads in these samples, giving the attribute “presence of beads” a lower rating than the others. This result suggests a preference for the presence of the beads. It is considered that this perception may have been influenced not only by the dispersion of the beads but also by the possibility that different viscosity levels, combined with the beads presence among the samples, affected perception.

The Vf-Fire and Vf-Earth samples emerged from the use of JAR scale as the nearest to the ideal vinaigrette flavour profiles (Figure 2). However, V-Earth held a slight advantage, being described as well-balanced, familiar and evocative of fresh Boletus edulis Bull mushrooms, with an ideal consistency (Table 6). Also, one tester noted a subtle sweetness in the mushroom vinaigrette despite no sweetening ingredients being added. The main drawback of Vf-Fire was its spiciness, which some found overpowering, with a few tasters noting that a milder version would have been their top choice. Vf-Water, while having a pleasant flavour, was perceived as too intense, probably due to an excess of seaweed, causing some hesitation and even rejection among tasters. A previous study, Ortegas et al. [33], also applying JAR scales, found that grape pomace products obtained from red and white grapes at a level of 10% could be a good alternative to develop new healthier muffins with high fibre content.

In our study, Vf-Air, despite being rated second for achieving the desired flavour intensity, ranked only third in terms of positive purchase intention (35%) [12], further highlighting the stronger consumer preference for Vf-Fire and Vf-Earth. In fact, according to Flores et al., 2025 [10]. Vf-Earth showed the strongest positive purchase intention (80%), suggesting that consumers find it most appealing. V-Fire also demonstrates relatively high acceptance (65%). On the opposite side, Vf-Water showed the highest negative purchase intention (54%), followed by Vf-Air (48%).

It is important to emphasise that the four vegan vinaigrettes are highly versatile, as they can be used as accompaniments with several potential gastronomic applications, such as salads, pasta, with fish, meat, or plant-based dishes, cold soups, sandwiches, as a topping in finger-foods and other ready-to-eat foods.

Although Dikel & Dikel [25] highlighted the challenges consumers face in accepting new food products derived from waste and by-products, Højlund & Mouritsen [2] emphasised the importance of involving multiple sectors in the development of new gastronomic strategies to combat food waste, advocating for collaborative approaches that integrate the food industry with education, tourism and culinary culture.

Transforming calcium alginate beads, a by-product of sparkling-wine production into innovative vinaigrettes represents a sustainable zero-waste strategy that aligns with circular economy principles and reduces environmental impact compared to disposal.

Recently, grape pomace, a by-residue from the wine industry, was also studied and purposed as an agro-waste with promising potential for use in the development of innovative functional foods, dietary supplements and cosmetics, aligning with the circular bioeconomy model for its valorisation [34]. Another study, addressed the valorisation of grape pomace to develop plant-based mayonnaise alternatives and salad dressings [35].

From our point of view, offering such innovative, upcycled food products in wine tourism settings enhances the visitor experience by connecting culinary storytelling with ecological responsibility, adding value to wine and food tourism through differentiated sensory experiences grounded in sustainable gastronomy. Vinaigrettes enriched with innovative and some functional ingredients, such as mushrooms [36], halophyte plants such as salicornia [37] or calcium alginate beads from agro-industrial byproducts, represent a promising frontier in functional gastronomy, combining health benefits, sustainability and culinary innovation.

Recently, food waste valorisation has garnered global attention as an effective approach in line with circular economy principles [38]. Moreover, our work is a contribution to existing market trends focused on vegan products, innovative food products and reuse of waste from industry.

Some study limitations were found such as small sensory panel size (40 untrained tasters), lack of microbiological shelf-life data and limited scalability evaluation.

These four vinaigrettes are likely to be more appealing to consumers if introduced through gastronomic events that combine sensory experiences with educational initiatives. Hosting workshops on sustainability and the circular economy in collaboration with academic institutions, alongside chef- and/or sommelier-led show cooking sessions demonstrating how to incorporate these products into different dishes or wine-food pairings, could significantly enhance consumer acceptance. Furthermore, such events would promote greater environmental awareness among suppliers, chefs, sommeliers and consumers, fostering a more sustainable and informed approach to food consumption based on the wine industry by-products.

In future, this work should be complemented by vinaigrettes shelf-life testing, find eco-friendly packaging solutions and pilot marketing studies.

5. Conclusions

The recovery of calcium alginate beads offers a promising approach to valorising sparkling wine production waste, with potential applications in gastronomic products such as vinaigrettes. This study highlights their role in promoting a more circular and sustainable wine and food tourism. The Vf-Earth and Vf-Fire vinaigrettes were the top-performing formulations, while Vf-Air can be highlighted in the context of flavour intensity.

Further research is needed to evaluate the shelf life of the vinaigrettes. Moreover, if the spiciness of the Vf-Fire formulation and the seaweed content in the Vf-Water are reduced, it is highly likely that consumer acceptance will improve.

The innovative vegan vinaigrettes presented in this study could be considered in the future by restaurants, wineries and other stakeholders in the Portuguese Bairrada region or other sparkling wine production countries. Additionally, the development of new food applications can further contribute to the valorisation of calcium alginate beads, within a circular economy framework and in alignment with the principles of food system sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.B., C.F. and C.P.; methodology, G.B., C.F. and C.P.; software, G.B. and C.P.; validation, G.B. and C.P.; formal analysis, C.F. and T.R.; investigation, C.F., T.R., G.B. and I.S.; resources, G.B., C.F., C.P., T.R. and I.S.; data curation, C.F., G.B. and C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.F. and G.B.; writing—review and editing, C.F., G.B., C.P., I.S. and T.R.; visualisation, C.F. and G.B.; supervision, G.B. and C.P.; project administration, G.B. and C.P.; funding acquisition, G.B. and C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors thank the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) for the financial support to the Research Centre for Natural Resources, Environment and Society—CERNAS (UIDB/00681) and to the project UIDB/04129/2020 of LEAF—Linking Landscape, Environment, Agriculture and Food, Research Unit.

Data Availability Statement

The original database is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the tasters who voluntarily took part in the sensory analysis. Jorge Viegas (ESAC/IPC) for analytical support. Adega Cooperativa de Cantanhede Crl, Global Wines S.A., Aromas & Boletos Lda. and Mendes Gonçalves S.A. for some ingredients supply.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Inês Santos was employed by the company Global Wines S.A. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CERNAS | Research Centre for Natural Resources, Environment and Society |

| ESAC/IPC | Coimbra Agriculture School of Polytechnic University of Coimbra |

| FCT | Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology |

| HSD | Honestly Significant Difference |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| JAR | Just-About-Right |

| LEAF | Linking Landscape, Environment, Agriculture and Food Research Centre |

| PDO | Protected Designation of Origin |

| PGI | Protected Geographical Indication |

References

- Alessandroni, L.; Bellabarba, L.; Corsetti, S.; Sagratini, G. Valorization of Cynara cardunculus L. Var. Scolymus Processing By-Products of Typical Landrace “Carciofo Di Montelupone” from Marche Region (Italy). Gastronomy 2024, 2, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Højlund, S.; Mouritsen, O.G. Sustainable Cuisines and Taste Across Space and Time: Lessons from the Past and Promises for the Future. Gastronomy 2025, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Vicente, G.; Martín Barroso, V.; Blanco Jiménez, F.J. Sustainable Tourism, Economic Growth and Employment—The Case of the Wine Routes of Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, A.; Silva, P. Sustainable Development Directions for Wine Tourism in Douro Wine Region, Portugal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, L.M.M. As Rotas Dos Vinhos Em Portugal: Estudo de caso da Rota do Vinho da Bairrada. Master’s Thesis, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto da Vinha e do Vinho. Evolution of National Wine Production by Wine Region: Series 2009/2010 to 2023/2024; Instituto da Vinha e do Vinho: Lisboa, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mikinac, K.; Laškarin Ažić, M.; Rašan, D. Enogastronomic Experience: A State-of-the-Art-Review. Int. Sci.-Bus. Conf.–LIMEN 2022, 8, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantsch, L.; Flores, S.S.; Vale, Z.D.N. Local Gastronomy and Wine Geographical Indications (GIs): Framework for Identifying Pairing Potential. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2024, 35, 100856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-García, J.; García-Martínez, T.; Mauricio, J.C.; Moreno, J. Yeast Immobilization Systems for Alcoholic Wine Fermentations: Actual Trends and Future Perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, C.; Ribeiro, T.; Santos, J.; Prista, C.; Botelho, G. Proposal for Upcycling Sparkling Winemaking Waste for Oenogastronomy Tourism. Millenium-J. Educ. Technol. Health 2025, 2, e41097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.S.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. Co-creating wine and food tourism experiences: The case of rota da Bairrada. J. Tour. Dev. 2021, 1, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Barros, A.; Queirós, A.; Pina, A.; Vale, A.; Ramoa, H.; Folha, J.; Carneiro, R. Development of a Solid Vinaigrette and Product Testing. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2013, 11, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Gendreau, M.; Vélez-Ruiz, J. Physicochemical and Flow Characterization of a Mustard-Vinaigrette Salad Dressing. J. Food Sci. Nutr. Res. 2019, 2, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena, P.; Coyago, A. Valoración sensorial de salsas y vinagretas de uvilla para determinar la aceptación de productos. Qual. Rev. Científica 2023, 25, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedinzadeh, S.; Torbati, M.; Azadmard-Damirchi, S. Some Qualitative and Rheological Properties of Virgin Olive Oil- Apple Vinegar Salad Dressing Stabilized With Xanthan Gum. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 6, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N.K.; Omar, W.H.W.; Hussin, A.S.M. Formulation of Natural Hydrocolloids and Virgin Coconut Oil as a Plant-Based Salad Dressing. Carpathian J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 14, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage. Technical Report: Colorimetry, CIE 15:2004; Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage: Vienna, Austria, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, R.G. Reporting of Objective Color Measurements. HortScience 1992, 27, 1254–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 4121:2003; International Organization for Standardization Sensory Analysis–Guidelines for the Use of Quantitative Response Scales. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- ISO 5492:2008; International Organization for Standardization Sensory Analysis–Vocabulary. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- ISO 11136:2014; International Organization for Standardization Sensory Analysis–Methodology–General Guidance for Conducting Hedonic Tests with Consumers in a Controlled Area. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 6658:2017; International Organization for Standardization Sensory Analysis–Methodology–General Guidance. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Okumus, B.; Koseoglu, M.A.; Ma, F. Food and Gastronomy Research in Tourism and Hospitality: A Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habashi, F. Zoroaster and the Theory of Four Elements. Bull. Hist. Chem. 2000, 25, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikel, S.; Dikel, Ç. A Gastronomic Approach to Industrial Aquaculture Waste Utilization. Turk. J. Agric.-Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 12, 1849–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T.C. Controlo Da Qualidade de Vinho e de Vinagretes Formulados Para Valorizar Um Subproduto Da Produção de Vinhos Espumantes. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Politécnico de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Laranjeira, C.; Vaz, J.; Torgal, I.; Faro, M.; Lima, M.; Ribeiro, M.; Henriques, M. Tecnologia vinagreira, desenvolvimento de novos produtos com adição de Physalis peruviana - Vinagrete. Rev. Da UI_IPSantarém 2015, 3, 216–235. Available online: https://revistas.rcaap.pt/uiips/article/view/14376 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Smittle, R.B. Microbiological Safety of Mayonnaise, Salad Dressings, and Sauces Produced in the United States: A Review. J. Food Prot. 2000, 63, 1144–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, J.M.A.S.; Santos, E.M.; Gonçalves, M.L.L.; Sobral, A.P.T.; Raimundo, D.; Nascimento, A.R.; Bussadori, S.K.; Azedo, M.R.; Sabato, S.F. Avaliação sensorial e pH de molhos para saladas tratados por radiação gama. Res. Soc. Dev. 2023, 12, e24212239157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafeuille, B.; Francezon, N.; Goulet, C.; Perreault, V.; Turgeon, S.L.; Beaulieu, L. Impact of Temperature and Cooking Time on the Physicochemical Properties and Sensory Potential of Seaweed Water Extracts of Palmaria palmata and Saccharina longicruris. J. Appl. Phycol. 2022, 34, 1731–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A. Implementação Do Sistema CIELAB Na Avaliação Colorimétrica de Vinhos Brancos e Vinhos Rosados. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Naderi, N.; Naderi, N.; Boo, H.C.; Lee, K.-H.; Chen, P.-J. Editorial: Food Tourism: Culture, Technology, and Sustainability. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1390676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Heras, M.; Gómez, I.; De Pablos-Alcalde, S.; González-Sanjosé, M.L. Application of the Just-About-Right Scales in the Development of New Healthy Whole-Wheat Muffins by the Addition of a Product Obtained from White and Red Grape Pomace. Foods 2019, 8, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, T.; Luís, C.; Câmara, J.S.; Teixeira, J.; Perestrelo, R. Unveiling Potential Functional Applications of Grape Pomace Extracts Based on Their Phenolic Profiling, Bioactivities, and Circular Bioeconomy. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiapelo, L.; Pinna, N.; Blasi, F.; Ianni, F.; Verducci, G.; Cossignani, L. Harnessing Grape Pomace, a Multifunctional By-Product from the Wine Industry for High-Value Salad Dressings. Molecules 2025, 30, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contato, A.G.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Mushrooms in Innovative Food Products: Challenges and Potential Opportunities as Meat Substitutes, Snacks and Functional Beverages. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 156, 104868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroca, M.J.; Flores, C.; Ressurreição, S.; Guiné, R.; Osório, N.; Moreira Da Silva, A. Re-Thinking Table Salt Reduction in Bread with Halophyte Plant Solutions. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoun, A.; Cropotova, J.; Trif, M.; Rusu, A.V.; Bobiş, O.; Nayik, G.A.; Jagdale, Y.D.; Saeed, F.; Afzaal, M.; Mostashari, P.; et al. Consumer Acceptance of New Food Trends Resulting from the Fourth Industrial Revolution Technologies: A Narrative Review of Literature and Future Perspectives. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 972154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).