Optimizing the Agitation Position in a Continuous Stirring Settler: A CFD-PBM Strategy for Enhanced Liquid–Liquid Separation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

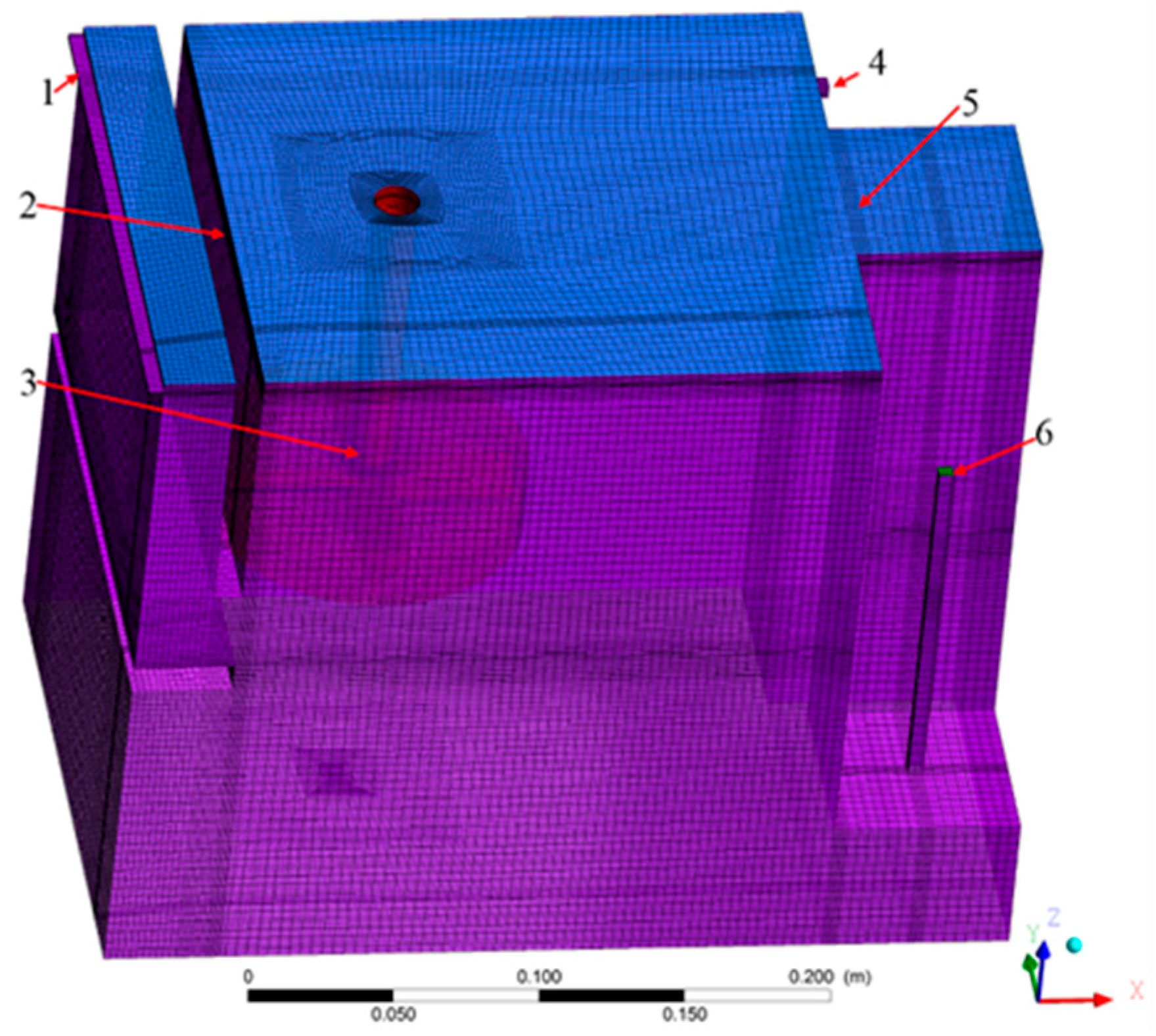

2.1. Computational Approach

2.1.1. Numerical Method

2.1.2. Governing Equations

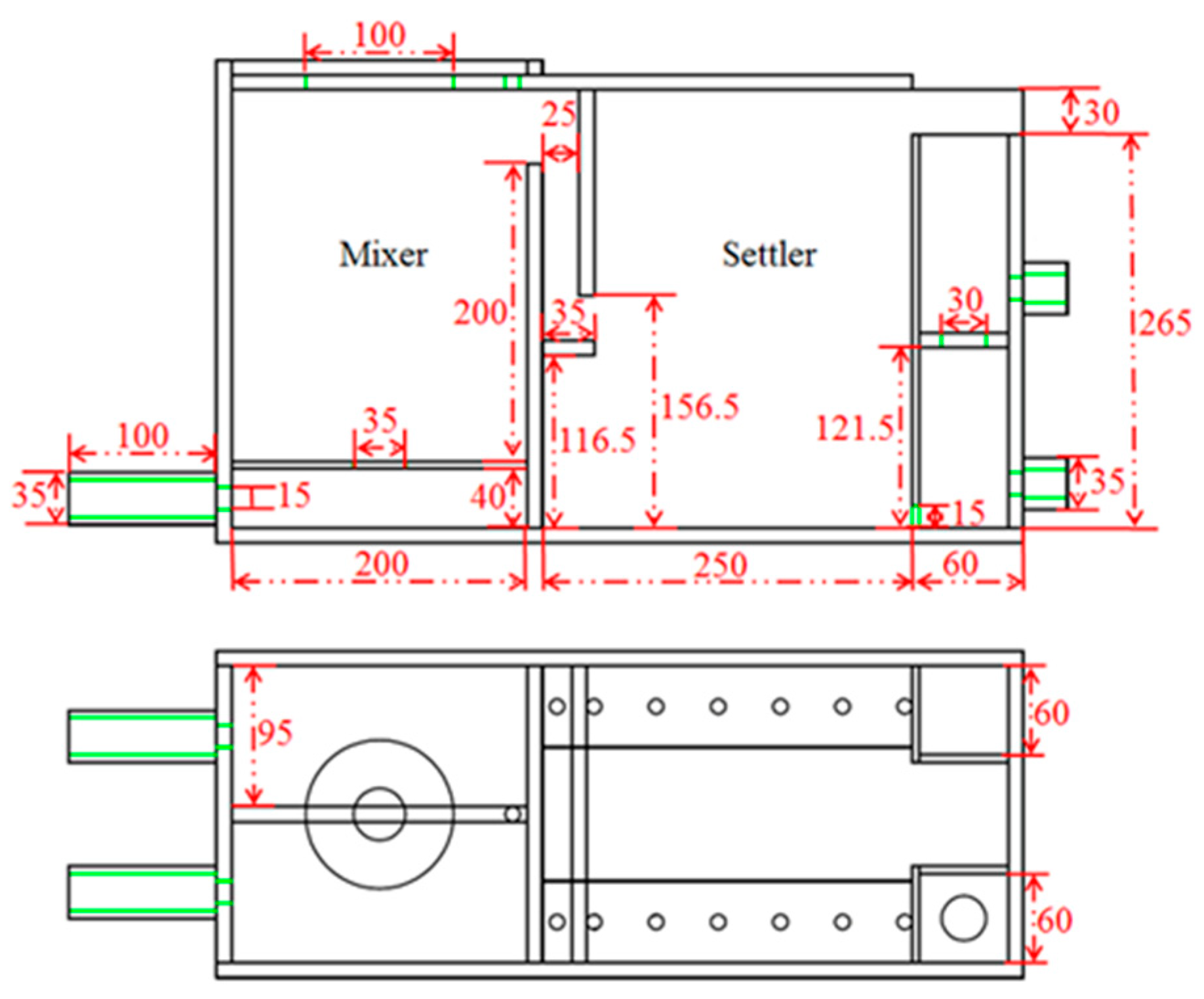

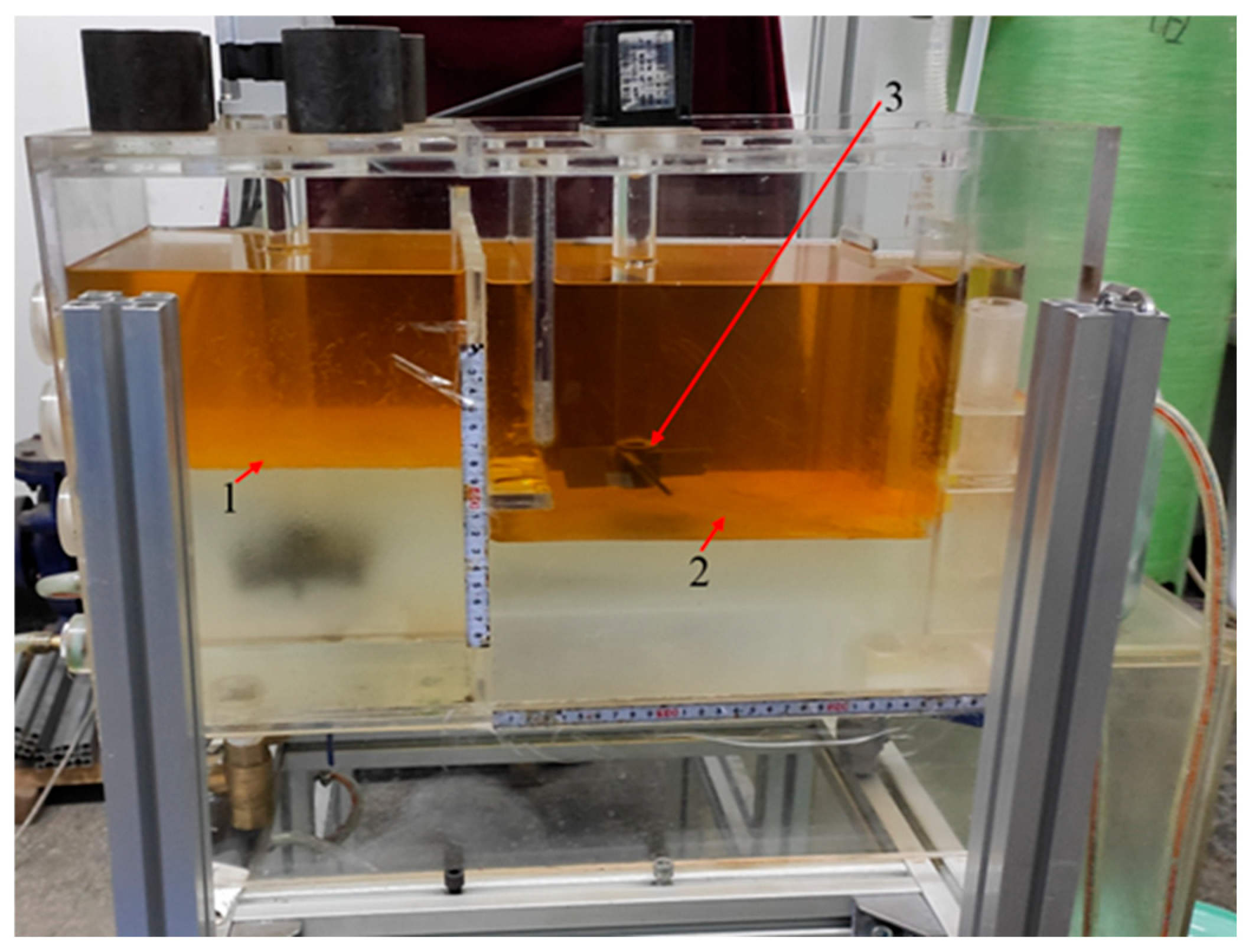

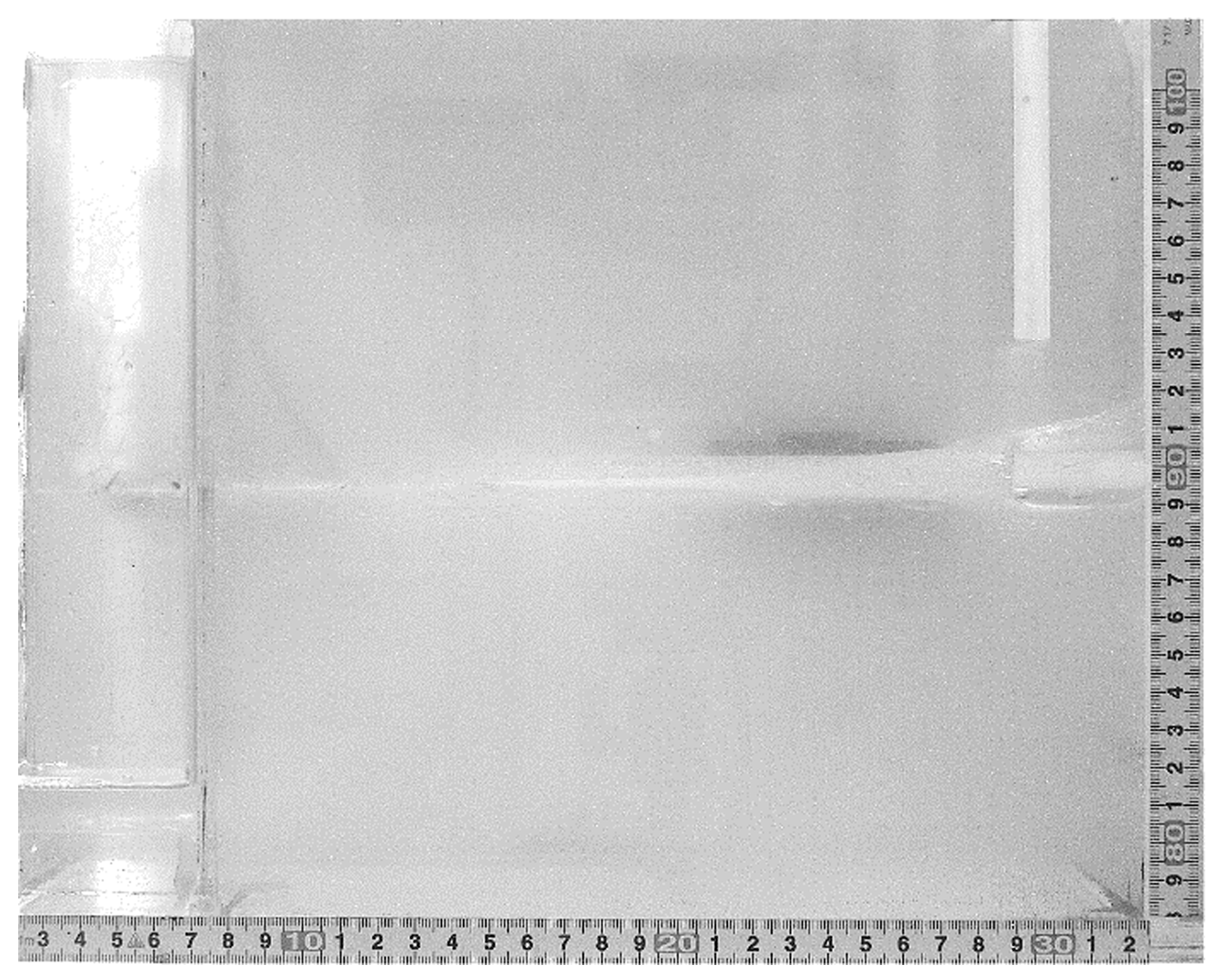

2.2. Experimental Setup and Method

3. Results and Discussion

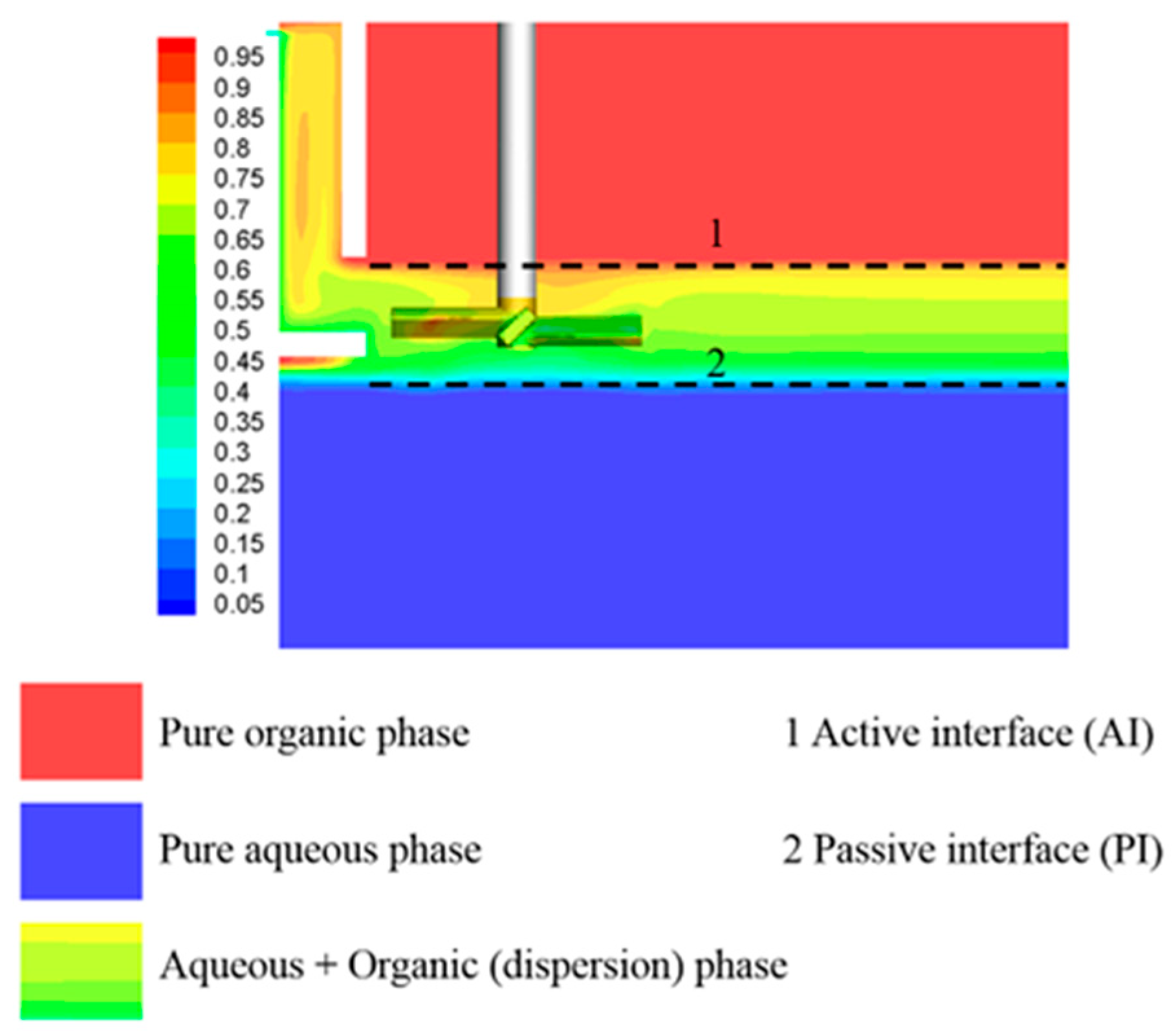

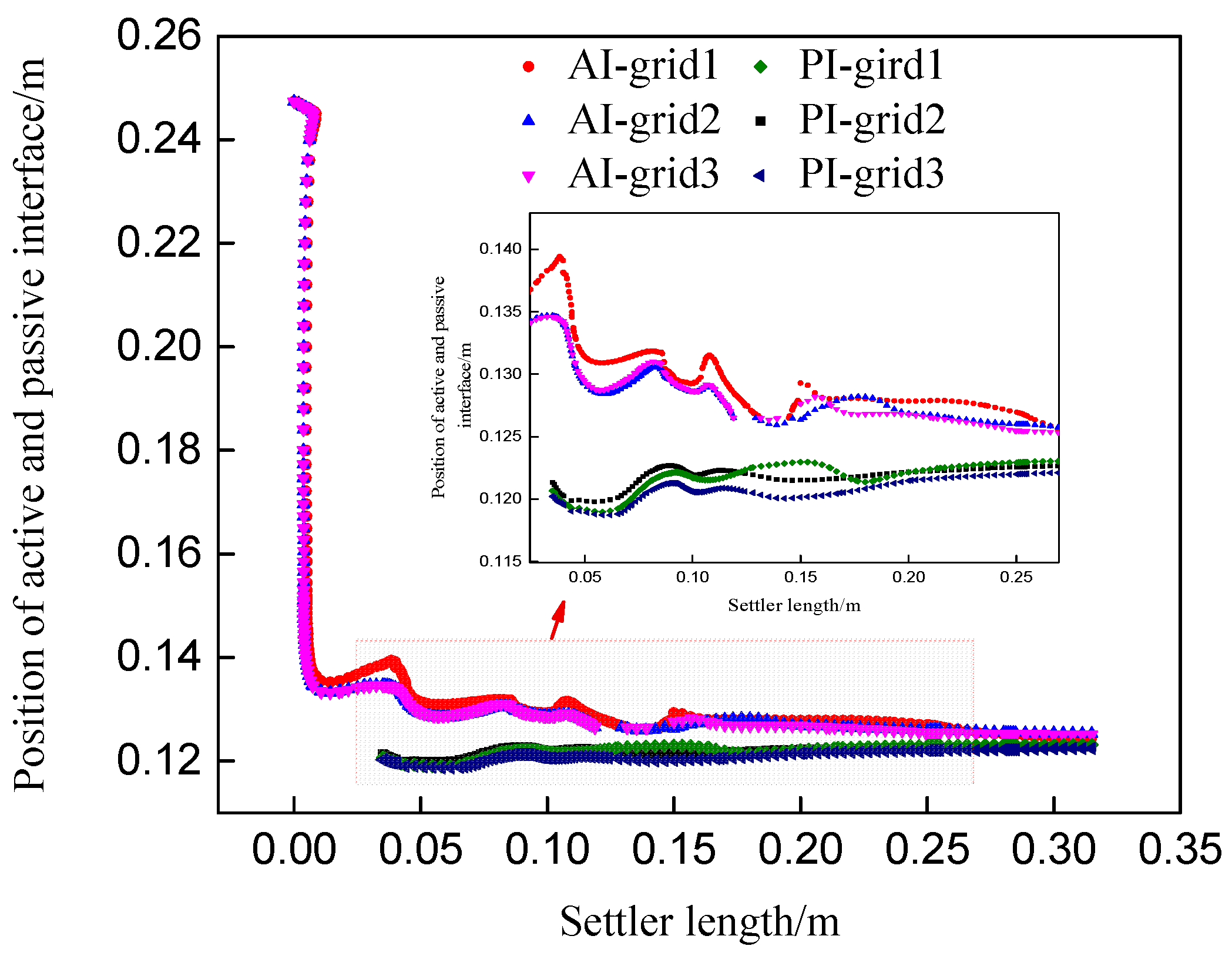

3.1. Preliminary Research

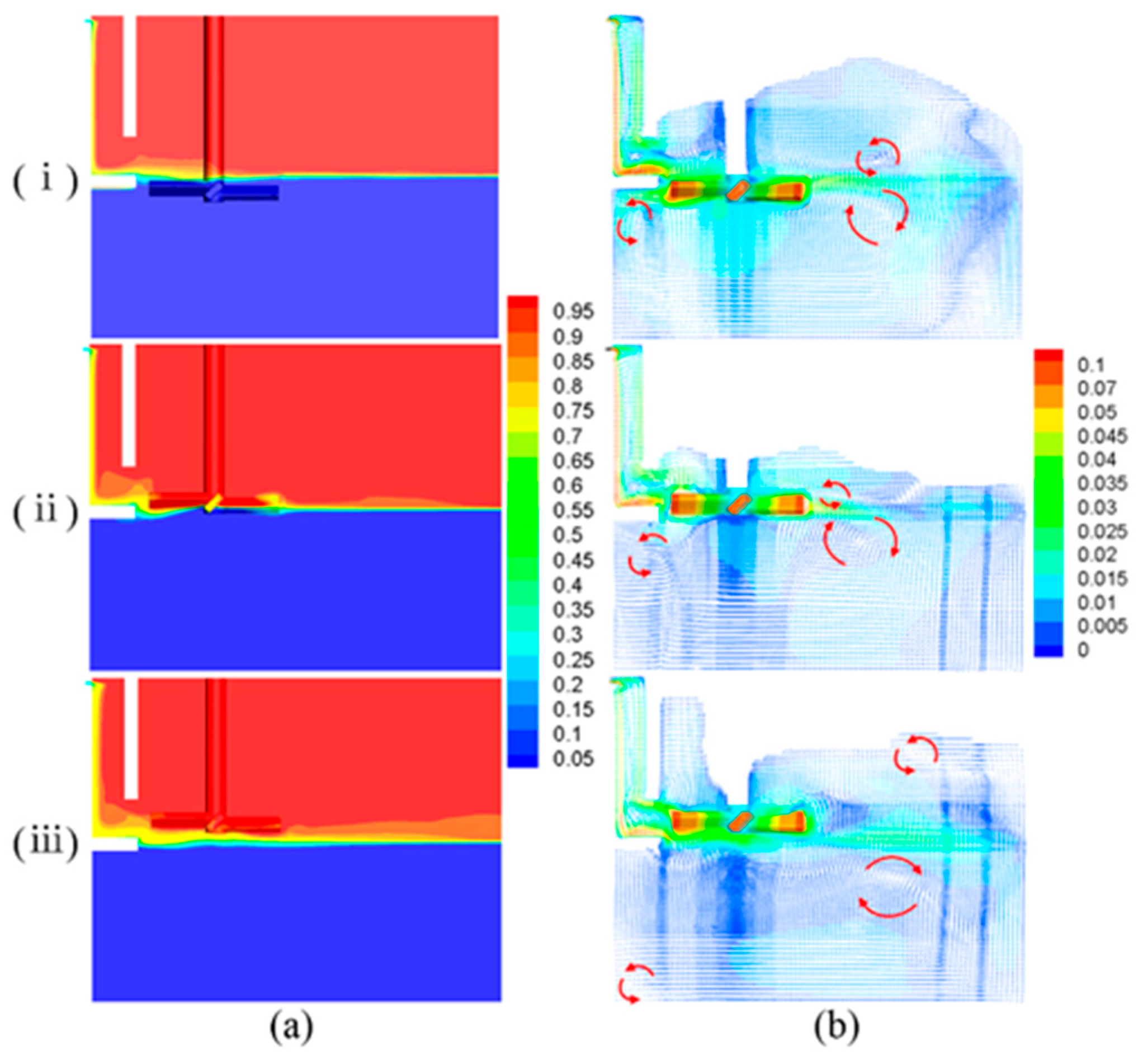

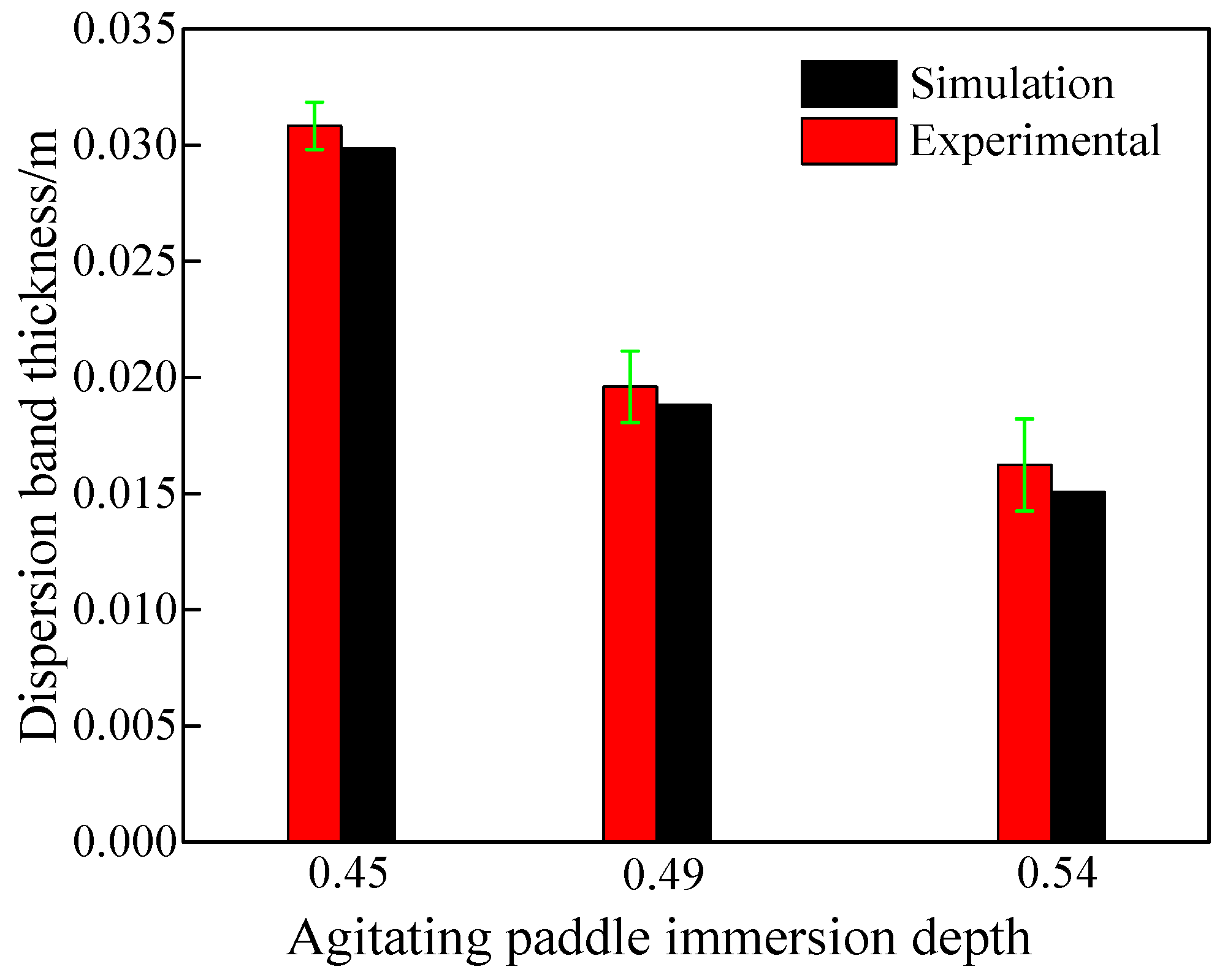

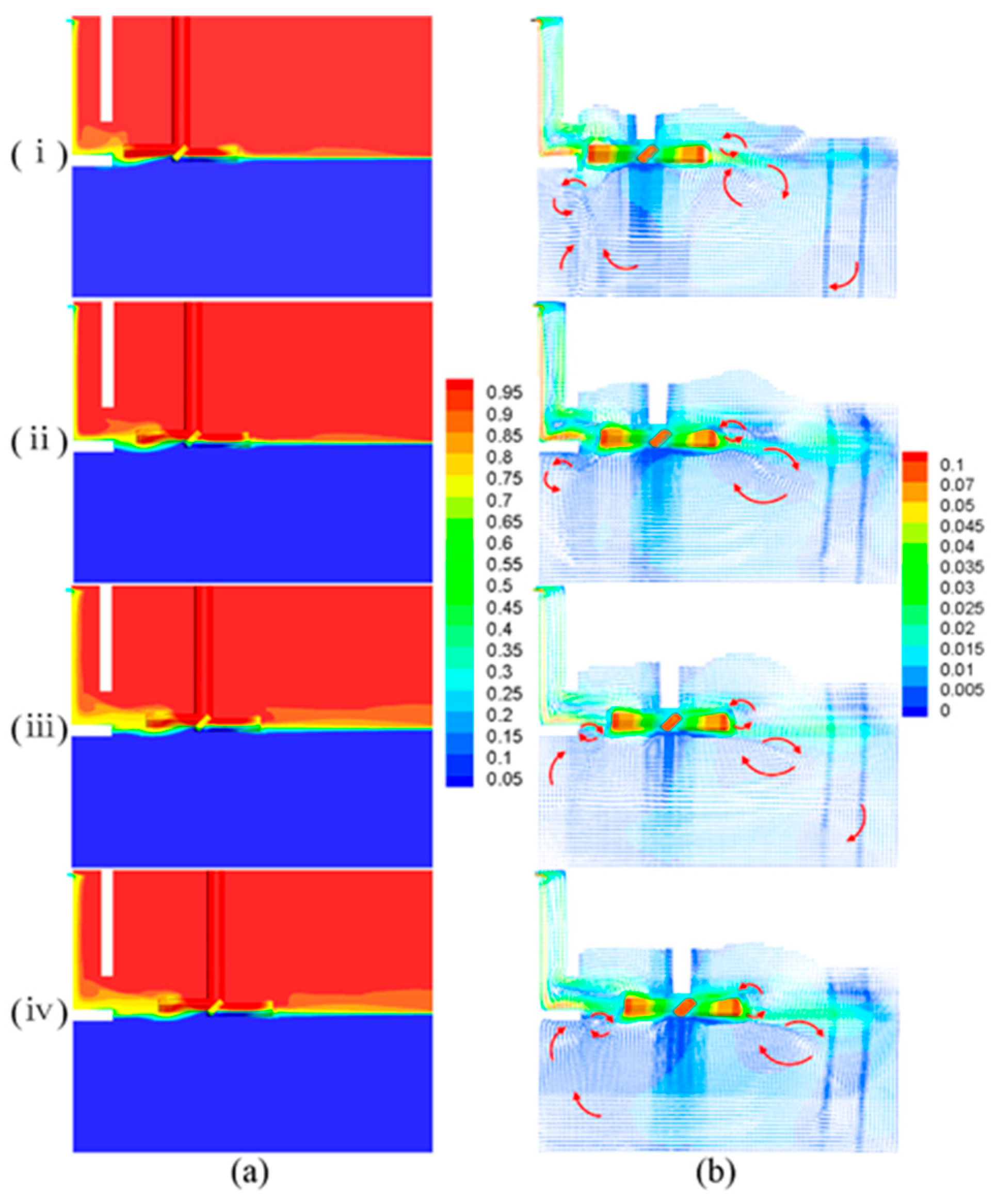

3.2. Effect of Agitating Paddle Immersion Depth on Dispersion Band Thickness

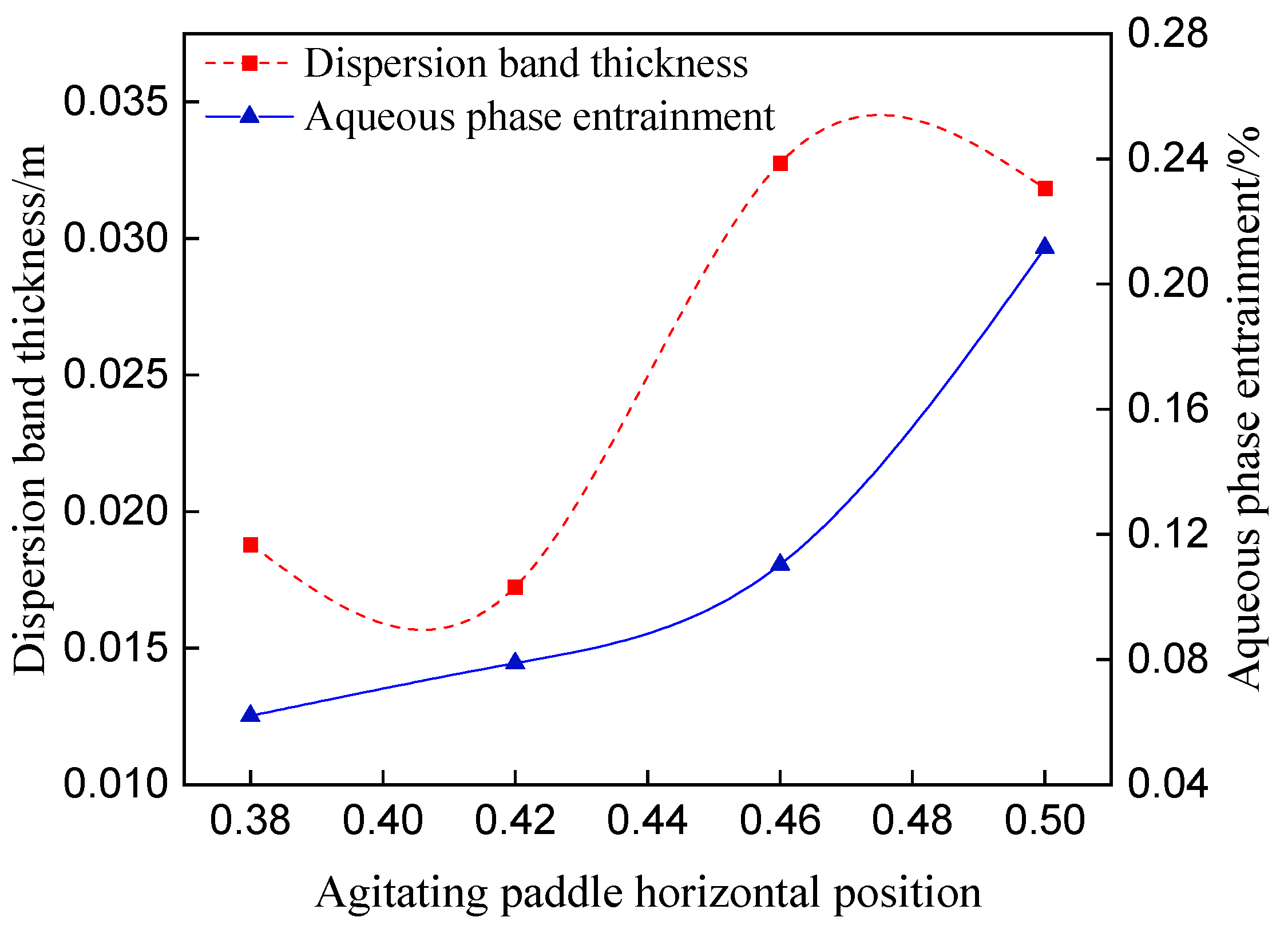

3.3. Effect of Agitating Paddle Horizontal Position on Dispersion Band Thickness

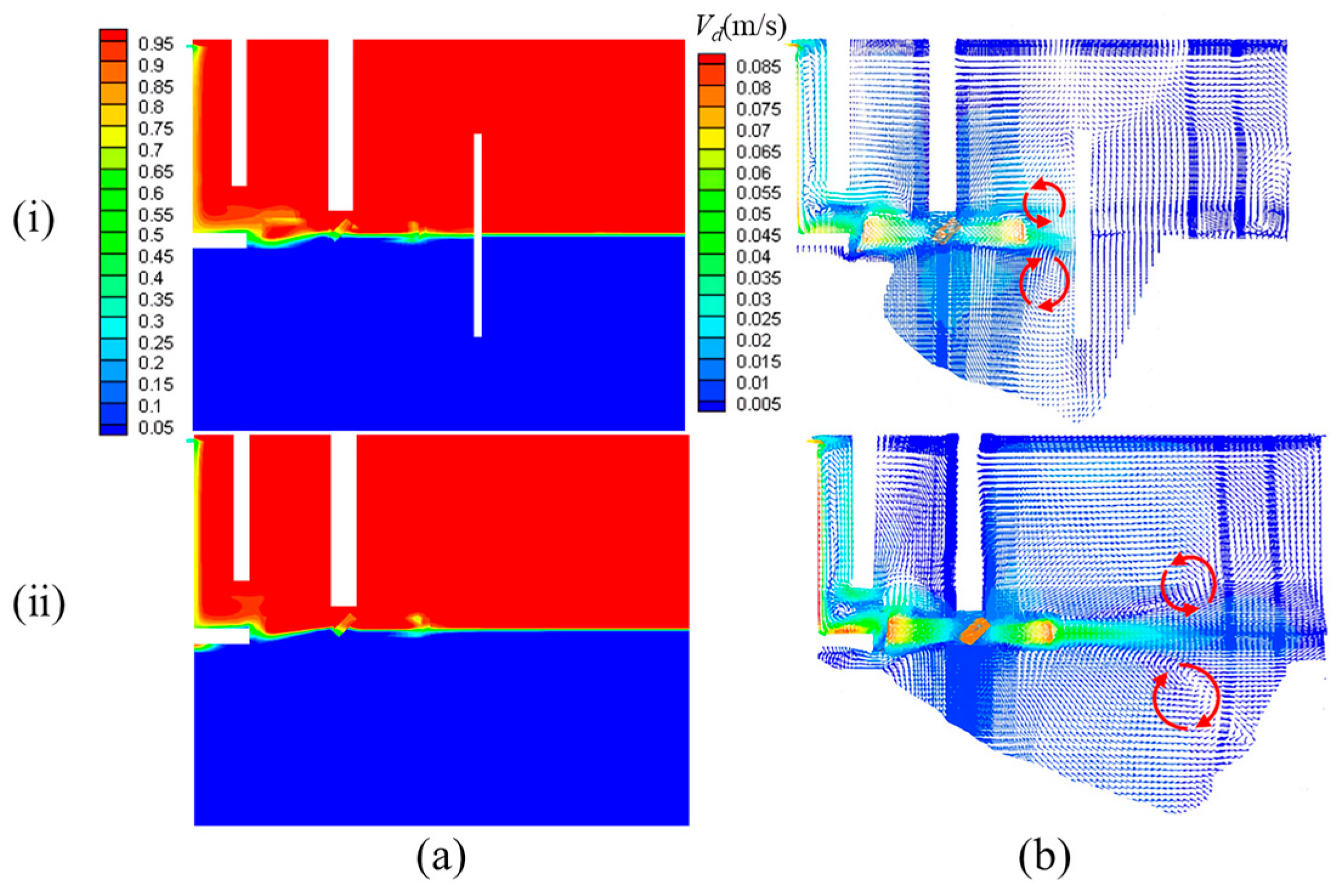

3.4. Effect of Baffle on Dispersion Band Thickness

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salehi, H.; Maroufi, S.; Nekouei, R.K.; Sahajwalla, V. Solvent extraction systems for selective isolation of light rare earth elements with high selectivity for Sm and La. Rare Met. 2025, 44, 2071–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.M.; Shi, D.; Peng, X.W.; Xie, S.L.; Li, J.F.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Zhang, L.C.; Niu, Y.; Chen, G.; Li, L.J. Lithium extraction from carbonate-rich Salt Lake brine using HBTA/TBP system. Rare Met. 2024, 43, 6717–6729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanassova, M. Thenoyltrifluoroacetone: Preferable molecule for solvent extraction of metals—Ancient twists to new approaches. Separations 2022, 9, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, S.; Adavodi, R.; Hosseini, M.R.; Veglio’, F. Efficient metal extraction from dilute solutions: A review of novel selective separation methods and their applications. Metals 2024, 14, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.Z. Application of complete counter-current mixer-settler in plants. Chin. J. Rare Met. 1998, 22, 60–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kostanyan, A.E.; Voshkin, A.A. Modeling of analytical, preparative and industrial scale counter-current chromatography separations. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1713, 464534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, N.; Oishi, Y.; Osanai, S.; Kusumoto, K.; Kikura, H.; Kawai, H. Assessment of silica sand behavior around rotating square rod in cylindrical container via ultrasonic velocity profiling. J. Vis. 2025, 28, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, H.P.; He, Y.; Muller, F.L.; Bayly, A.E.; Ashe, R.; Karras, A.; Hassanpour, A.; Bourne, R.A.; Fairweather, M.; Hunter, T.N. Physical and numerical characterisation of an agitated tubular reactor (ATR) for intensification of chemical processes. Chem. Eng. Process.-Process Intensif. 2022, 179, 109067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.S.; Tang, Q.; Wang, Y.D.; Fei, W.Y. Structural optimization of a settler via CFD simulation in a mixer-settler. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 995–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.N.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Han, J.C.; Wu, C.C.; Gong, J. Comparison of turbulent flow characteristics of liquid-liquid dispersed flow between CFD simulations and direct measurements with particle image velocimetry. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 125, 1209–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanarangam, K.; Yang, W.; Barnard, K.; Kelly, N.; Robinson, D. Flow mapping of full scale solvent extraction settlers using pulsed Doppler UVP technique. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 104, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, G.L.; Mohanarangam, K.; Yang, W.; Robinson, D.J.; Barnard, K.R. Flow pattern assessment and design optimisation for an industrial solvent extraction settler through in situ measurements and CFD modelling. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2016, 109, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.K.; Singh, K.; Shenoy, K.; Buwa, V.V. Numerical simulations of liquid-liquid flow in a continuous gravity settler using OpenFOAM and experimental verification. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 310, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.K.; Buwa, V.V. Effects of geometry and internals of a continuous gravity settler on liquid–liquid separation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 13929–13944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahakal, P.A.; Patwardhan, A.W. CFD modeling of liquid–liquid batch-stirred tank at high organic to aqueous phase ratios. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 19323–19340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milot, J.F.; Duhamet, J.; Gourdon, C.; Casamatta, G. Simulation of a pneumatically pulsed liquid-liquid extraction column. Chem. Eng. J. 1990, 45, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.L.; Chen, J.Q.; Liu, M.L.; Ji, Y.P.; Ding, G.D.; Zhang, L. CFD simulation of oil–water separation characteristics in a compact flotation unit by population balance modeling. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2017, 38, 1435–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.H.; Zhang, T.A.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Zhang, Z.M.; Zhu, S. CFD-PBM Simulation and PIV Measurement of Liquid–Liquid Flow in a Continuous Stirring Settler. JOM 2019, 71, 4500–4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaker, A.H.; Buwa, V.V. Separation of liquid–liquid dispersion in a batch settler: CFD-PBM simulations incorporating interfacial coalescence. AIChE J. 2020, 66, e16983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, N.; Singh, K.; Patwardhan, A.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Shenoy, K. CFD-PBM simulations of a pulsed sieve plate column. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2019, 111, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, S.; Sheibat-Othman, N.; Marchisio, D.; Buffo, A.; Charton, S. Description of droplet coalescence and breakup in emulsions through a homogeneous population balance model. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 354, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, A.; de Souza, L.; Illner, M.; Hohl, L.; Kraume, M.; Repke, J.-U.; Thévenin, D. Simulating separation of a multiphase liquid-liquid system in a horizontal settler by CFD. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2017, 167, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Meng, X.H.; Zhang, R.; Liu, H.Y.; Xu, C.M.; Liu, Z.C.; Klusener, P.A. Droplet size distribution and droplet size correlation of chloroaluminate ionic liquid–heptane dispersion in a stirred vessel. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 268, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhou, H.; Jing, S.; Lan, W.J.; Li, S.W. CFD–PBM simulation of two-phase flow in a pulsed disc and doughnut column with directly measured breakup kernel functions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 201, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedipour, M.; Puttinger, S.; Doppelhammer, N.; Pirker, S. Investigation on turbulence in the vicinity of liquid-liquid interfaces—Large eddy simulation and piv experiment. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 198, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rave, K.; Hermes, M.; Hundshagen, M.; Skoda, R. Assessment of scale-adaptive turbulence modeling in coupled CFD-PBM 3D flow simulations of disperse liquid-liquid flow in a baffled stirred tank with particular emphasis on the dissipation rate. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 270, 118509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.H.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Zhang, T.A.; Zhang, Z.M.; Zhu, S. Liquid–liquid flow in a continuous stirring settler: CFD-PBM simulation and experimental verification. JOM 2019, 71, 1650–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, L.; Zhang, Z.M.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Wang, S.C.; Zhang, T.A.; Liu, Y. Numerical simulation of enhanced oil-water separation in a three-stage double-stirring extraction tank. China Pet. Process. Petrochem. Technol. 2015, 17, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, S.; Yan, L.; Zhang, T. Numerical Simulation on Multiphase Fluid Dynamic in High Efficient Clarification and Extraction Tank with Double Stirring. Chin. J. Rare Met. 2015, 39, 540–545. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.C.; Zhang, T.A.; Zhang, Z.M.; Chao, L.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Liu, Y. Effect of stirring on oil-water separation in rare earth mixer-settler. China Pet. Process. Petrochem. Technol. 2014, 16, 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, C.; Zhang, Z.M.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Zhang, T.A. Numerical simulation on fluid flow characteristics of the settler in high efficient clarification and extraction tank with double stirring. J. Northeast. Univ. Nat. Sci. 2014, 35, 1570. [Google Scholar]

- Morsi, S.; Alexander, A. An investigation of particle trajectories in two-phase flow systems. J. Fluid Mech. 1972, 55, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Y.; Gao, Z.M.; Buffo, A.; Podgorska, W.; Marchisio, D.L. Droplet breakage and coalescence in liquid–liquid dispersions: Comparison of different kernels with EQMOM and QMOM. AIChE J. 2017, 63, 2293–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsouris, C.; Tavlarides, L.L. Breakage and coalescence models for drops in turbulent dispersions. AIChE J. 1994, 40, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instrument Name | Manufacturer | Precision |

|---|---|---|

| Metallographic microscope (MIT500) | Chongqing Optec Instrument Co., Ltd. Chongqing, China | 0.5 μm |

| High-speed camera i-speed 3 | Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan | 10,000 frames per second |

| Interfacial Tensiometers DVT50 | Kruss Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China | 0.001 mN/m |

| Digital viscometer LC-NDJ-5S | LACHOI Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd. Shaoxing, China | ±2% |

| Condition | Dispersion Band Thickness/m | Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Comparison group | 0.0188 | - |

| Immersion depth optimization | 0.0151 | −19.7% |

| Horizontal position optimization | 0.0173 | −7.9% |

| With baffle | 0.0191 | 1.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, X.; Zhang, T.; Mu, W. Optimizing the Agitation Position in a Continuous Stirring Settler: A CFD-PBM Strategy for Enhanced Liquid–Liquid Separation. Processes 2025, 13, 2536. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13082536

Guo X, Zhang T, Mu W. Optimizing the Agitation Position in a Continuous Stirring Settler: A CFD-PBM Strategy for Enhanced Liquid–Liquid Separation. Processes. 2025; 13(8):2536. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13082536

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Xuhuan, Tingan Zhang, and Wangzhong Mu. 2025. "Optimizing the Agitation Position in a Continuous Stirring Settler: A CFD-PBM Strategy for Enhanced Liquid–Liquid Separation" Processes 13, no. 8: 2536. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13082536

APA StyleGuo, X., Zhang, T., & Mu, W. (2025). Optimizing the Agitation Position in a Continuous Stirring Settler: A CFD-PBM Strategy for Enhanced Liquid–Liquid Separation. Processes, 13(8), 2536. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13082536