γ-Valerolactone Pulping as a Sustainable Route to Micro- and Nanofibrillated Cellulose from Sugarcane Bagasse

Abstract

1. Introduction

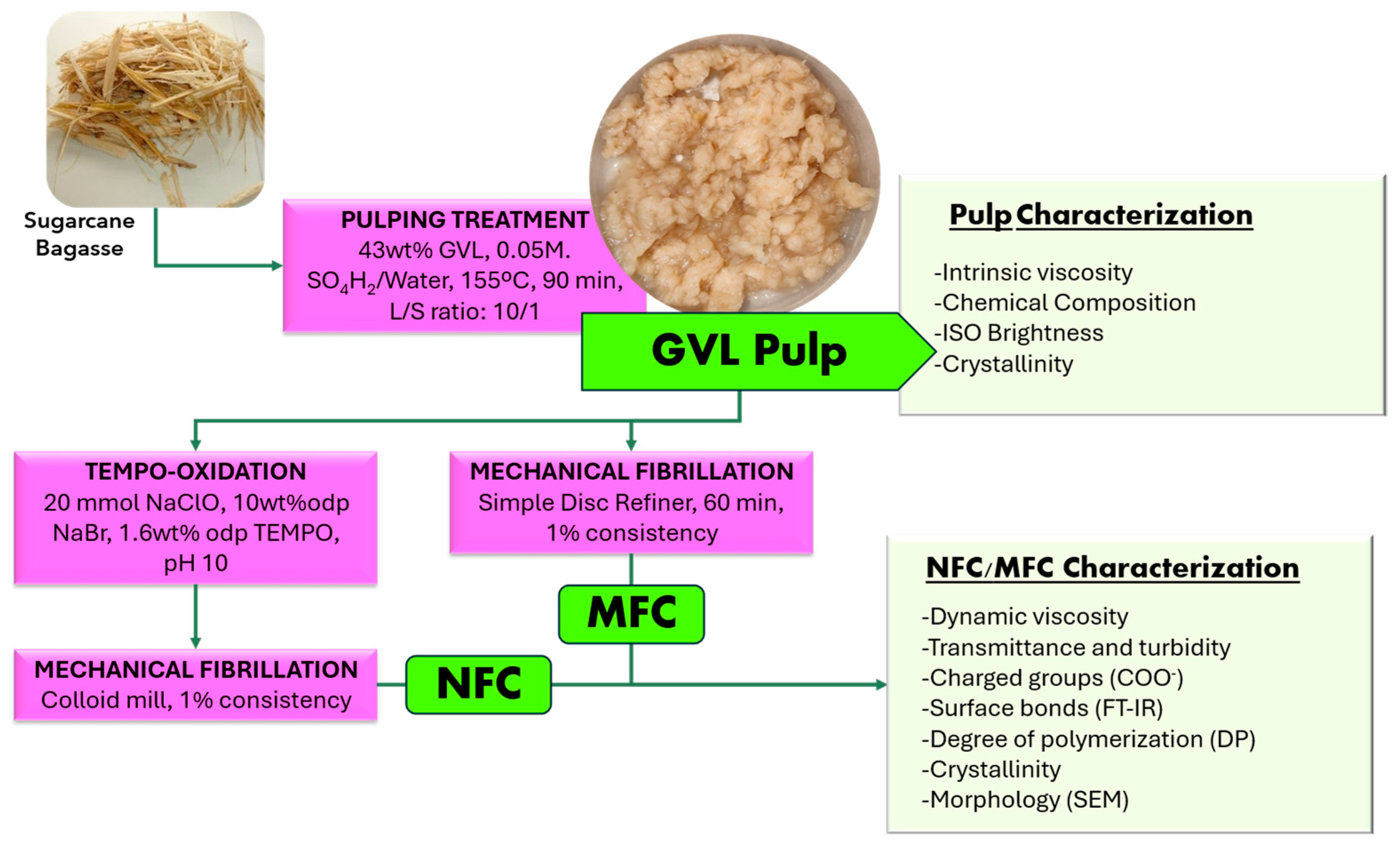

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. GVL Process Conditions, Characterization, and Scaling-Up

2.3. NFC/MFC Production

2.4. NFC/MFC Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

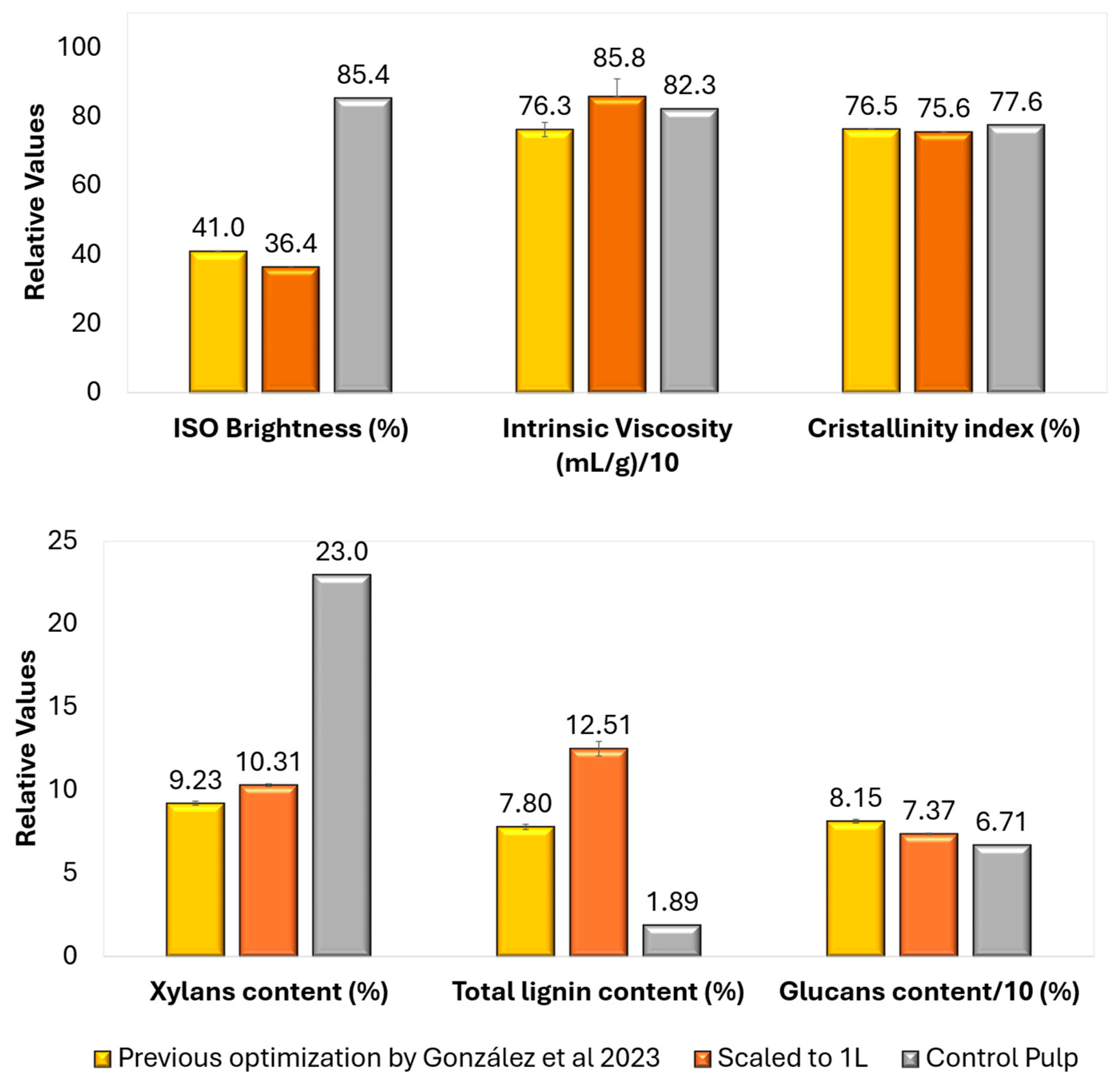

3.1. Pulps Characterization

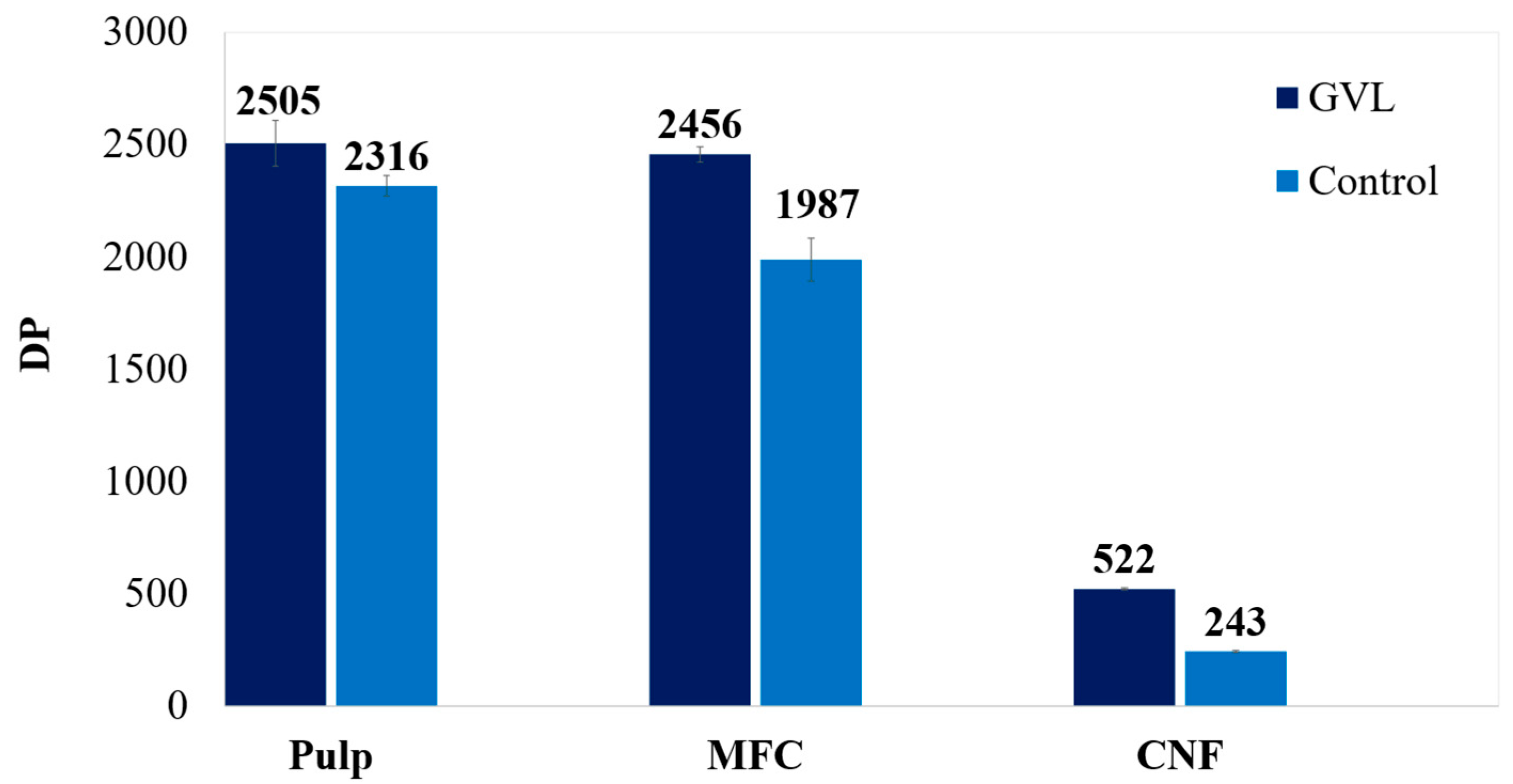

3.2. Purely Mechanical Fibrillation of GVL Pulps for MFC Production

3.3. Surface Oxidation of GVL Fibers for NFC Production

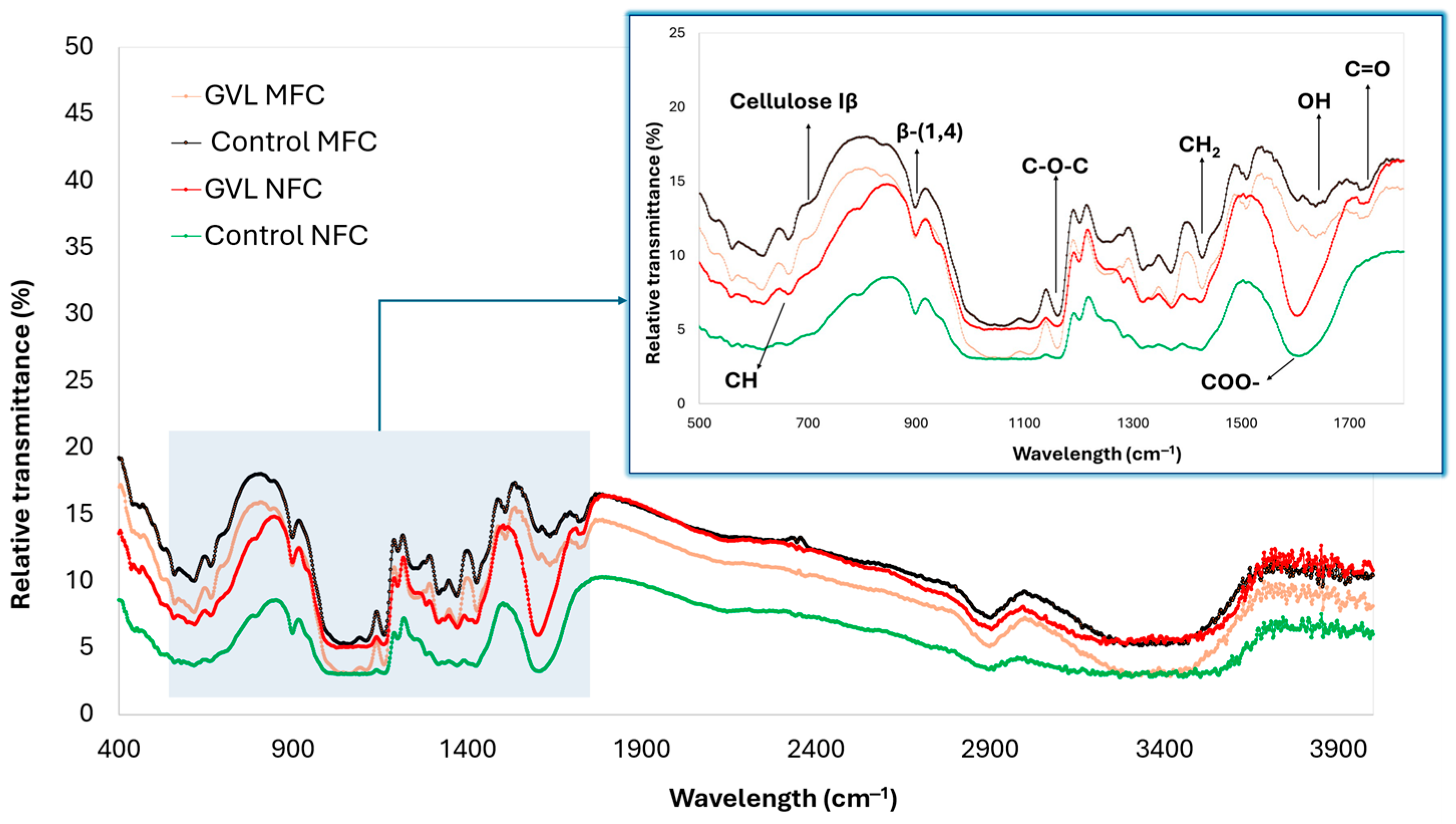

3.4. DP, Crystallinity, and FTIR for MFC and NFC

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DPv | Degree of polymerization |

| CI | Crystallinity index |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| GVL | γ-Valerolactone |

| MFC | Microfibrillated cellulose |

| NFC | Nanofibrillated cellulose |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| Soda–AQ | Soda–anthraquinone |

| TCF | Total chlorine-free bleaching |

| TEMPO | 2,2,6,6-tetrametil-1-piperidiniloxi |

References

- Yankov, D. Fermentative Lactic Acid Production from Lignocellulosic Feedstocks: From Source to Purified Product. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 823005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Q.; Qi, X.; Zhen, M.; Qian, H.; Nie, Y.; Bai, C.; Zhang, S.; Bai, X.; Ju, M. Biorefinery Roadmap Based on Catalytic Production and Upgrading 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 119–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, G.; Ehman, N.; Felissia, F.E.; Area, M.C. Strategies towards a Green Solvent Biorefinery: Efficient Delignification of Lignocellulosic Biomass Residues by Gamma-Valerolactone/Water Catalyzed System. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 205, 117535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê, H.Q.; Pokki, J.-P.; Borrega, M.; Uusi-Kyyny, P.; Alopaeus, V.; Sixta, H. Chemical Recovery of γ-Valerolactone/Water Biorefinery. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 15147–15158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Ma, Q.; Zhu, J.Y.; Martin Alonso, D.; Runge, T. GVL Pulping Facilitates Nanocellulose Production from Woody Biomass. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 5316–5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granatier, M.; Lê, H.Q.; Ma, Y.; Rissanen, M.; Schlapp-Hackl, I.; Diment, D.; Zaykovskaya, A.; Pokki, J.-P.; Balakshin, M.; Louhi-Kultanen, M.; et al. Gamma-Valerolactone Biorefinery: Catalyzed Birch Fractionation and Valorization of Pulping Streams with Solvent Recovery. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehdi, H.; Fábos, V.; Tuba, R.; Bodor, A.; Mika, L.T.; Horváth, I.T. Integration of Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalytic Processes for a Multi-Step Conversion of Biomass: From Sucrose to Levulinic Acid, γ-Valerolactone, 1,4-Pentanediol, 2-Methyl-Tetrahydrofuran, and Alkanes. Top. Catal. 2008, 48, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Granollers Mesa, M.; Scapens, D.; Osatiashtiani, A. Advances in Sustainable γ-Valerolactone (GVL) Production via Catalytic Transfer Hydrogenation of Levulinic Acid and Its Esters. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 16494–16517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momayez, F.; Hedenström, M.; Stagge, S.; Jönsson, L.J.; Martín, C. Valorization of Hydrolysis Lignin from a Spruce-Based Biorefinery by Applying γ-Valerolactone Treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 359, 127466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, S.; Hedjazi, S.; Lê, H.Q.; Abdulkhani, A.; Sixta, H. High-Purity Cellulose Production from Birch Wood by γ-Valerolactone/Water Fractionation and IONCELL-P Process. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 288, 119364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Wang, M.; Ma, T.; Li, Z. Enhancing the Potential Production of Bioethanol with Bamboo by γ-Valerolactone/Water Pretreatment. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 16942–16954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevorah, R.M.; Huynh, T.; Vancov, T.; Othman, M.Z. Bioethanol Potential of Eucalyptus Obliqua Sawdust Using Gamma-Valerolactone Fractionation. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 250, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Q.; Wang, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Jiang, F.; Zhou, Z.; Cheng, D.; Dai, L. Nanocellulose Prepared with γ-Valerolactone Pretreatment and Its Enhancement in Colored Paper. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 135732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lê, H.Q.; Dimic-Misic, K.; Johansson, L.-S.; Maloney, T.; Sixta, H. Effect of Lignin on the Morphology and Rheological Properties of Nanofibrillated Cellulose Produced from γ-Valerolactone/Water Fractionation Process. Cellulose 2018, 25, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois-Correa, J.A. Depithers for Efficient Preparation of Sugar Cane Bagasse Fibers in Pulp and Paper Industry. Ing. Investig. Tecnol. 2012, 8, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, N.D.; Siddiah, C.H. Characteristics of Bagasse Based Paper and Pulp; Indian Pulp & Paper Technical Association: Saharanpur, India, 1966; pp. 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sluiter, A.; Hames, B.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D.; Crocker, D. Determination of Structural Carbohydrates and Lignin in Biomass. In Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP); National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 5351-1:2010; Pulps-Determination of Limiting Viscosity Number in Cupri-Ethylenediamine (CED) Solution. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Swizterland, 2010.

- ISO 2470-1:2016; Paper, Board and Pulps-Measurement of Diffuse Blue Reflectance Factor. Part 1: Indoor Daylight Conditions (ISO Brightness). The International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Swizterland, 2016.

- Saito, T.; Isogai, A. TEMPO-Mediated Oxidation of Native Cellulose. The Effect of Oxidation Conditions on Chemical and Crystal Structures of the Water-Insoluble Fractions. Biomacromolecules 2004, 5, 1983–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehman, N.; Ponce de León, A.; Felissia, F.E.; Area, M.C. Towards Biodegradable Barrier Packaging: Production of Films for Single-Use Primary Food Liquid Packaging. Bioresources 2022, 17, 5215–5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx-Figini, M. Significance of the Intrinsic Viscosity Ratio of Unsubstituted and Nitrated Cellulose in Different Solvents. Angew. Makromol. Chem. 1978, 72, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinoda, R.; Saito, T.; Okita, Y.; Isogai, A. Relationship between Length and Degree of Polymerization of TEMPO-Oxidized Cellulose Nanofibrils. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, L.; Creely, J.J.; Martin, A.E.; Conrad, C.M. An Empirical Method for Estimating the Degree of Crystallinity of Native Cellulose Using the X-Ray Diffractometer. Text. Res. J. 1959, 29, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, E.; Rol, F.; Bras, J.; Rodríguez, A. Production of Lignocellulose Nanofibers from Wheat Straw by Different Fibrillation Methods. Comparison of Its Viability in Cardboard Recycling Process. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 118083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Díaz, P. Influence of Mixing and Heat Transfer in Process Scale-Up. Master’s Thesis, Department of Engineering Sciences and Mathematics, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, I.; Compagnoni, M. Chemical Reaction Engineering, Process Design and Scale-up Issues at the Frontier of Synthesis: Flow Chemistry. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 296, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermsdorff, G.B.; Escobar, E.L.N.; da Silva, T.A.; Filho, A.Z.; Corazza, M.L.; Ramos, L.P. Ethanol Organosolv Pretreatment of Sugarcane Bagasse Assisted by Organic Acids and Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 300, 120263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Tan, X.; Miao, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ragauskas, A.J.; Zhuang, X. Mild Organosolv Pretreatment of Sugarcane Bagasse with Acetone/Phenoxyethanol/Water for Enhanced Sugar Production. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Maibam, P.D.; Singh, S.; Rajulapati, V.; Goyal, A. Sequential Pretreatment of Sugarcane Bagasse by Alkali and Organosolv for Improved Delignification and Cellulose Saccharification by Chimera and Cellobiohydrolase for Bioethanol Production. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehman, N.; Rodriguez Rivero, G.; Area, M.C.; Felissia, F. Dissolving Pulps by Oxidation of the Cellulosic Fraction of Lignocellulosic Waste. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2017, 51, 864–870. [Google Scholar]

- Maryana, R.; Nakagawa-izumi, A.; Kajiyama, M.; Ohi, H. Environment-Friendly Non-Sulfur Cooking and Totally ChlorineFree Bleaching for Preparation of Sugarcane Bagasse Cellulose. J. Fiber Sci. Technol. 2017, 73, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.M.; Pinto, I.S.S.; Machado, L.; Gando-Ferreira, L.; Quina, M.J. Sustainability of Kraft Pulp Mills: Bleaching Technologies and Sequences with Reduced Water Use. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 125, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granatier, M.; Schlapp-Hackl, I.; Lê, H.Q.; Nieminen, K.; Pitkänen, L.; Sixta, H. Stability of Gamma-Valerolactone under Pulping Conditions as a Basis for Process Optimization and Chemical Recovery. Cellulose 2021, 28, 11567–11578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, S.M.; Nada, A.M.A.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Tawfik, H. Soda Anthraquinone Pulping of Bagasse. Holzforschung 1988, 42, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Agrawal, S.; Nagpal, R.; Mishra, O.P.; Bhardwaj, N.; Mahajan, R. Production of Eco-Friendly and Better-Quality Sugarcane Bagasse Paper Using Crude Xylanase and Pectinase Biopulping Strategy. 3 Biotech 2023, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pere, J.; Pääkkönen, E.; Ji, Y.; Retulainen, E. Influence of the Hemicellulose Content on the Fiber Properties, Strength, and Formability of Handsheets. Bioresources 2018, 14, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafari Petroudy, S.R.; Ghasemian, A.; Resalati, H.; Syverud, K.; Chinga-Carrasco, G. The Effect of Xylan on the Fibrillation Efficiency of DED Bleached Soda Bagasse Pulp and on Nanopaper Characteristics. Cellulose 2015, 22, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, G.; Ehman, N.V.; Aguerre, Y.S.; Henríquez-Gallegos, S.; da Fonte, A.P.N.; Muniz, G.I.B.; Pereira, M.; Carneiro, M.E.; Vallejos, M.E.; Felissia, F.E.; et al. Quality of Microfibrillated Cellulose Produced from Unbleached Pine Sawdust Pulp as an Environmentally Friendly Source. Waste Biomass Valorization 2022, 13, 1609–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybysz Buzała, K.; Kalinowska, H.; Borkowski, J.; Przybysz, P. Effect of Xylanases on Refining Process and Kraft Pulp Properties. Cellulose 2018, 25, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.C.; Mendonça, M.C.; Damásio, R.A.P.; Zidanes, U.L.; Mori, F.A.; Ferreira, S.R.; Tonoli, G.H.D. Influence of Hemicellulose Content of Eucalyptus and Pinus Fibers on the Grinding Process for Obtaining Cellulose Micro/Nanofibrils. Holzforschung 2019, 73, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, Q.; Song, X.; Qin, C.; Wang, S.; Li, K. Effects of Residual Lignin on Mechanical Defibrillation Process of Cellulosic Fiber for Producing Lignocellulose Nanofibrils. Cellulose 2018, 25, 6479–6494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, Q.; Song, X.; Qin, C.; Wang, S.; Li, K. Effects of Residual Lignin on Composition, Structure and Properties of Mechanically Defibrillated Cellulose Fibrils and Films. Cellulose 2019, 26, 1577–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, K.L.; Venditti, R.A.; Rojas, O.J.; Habibi, Y.; Pawlak, J.J. A Comparative Study of Energy Consumption and Physical Properties of Microfibrillated Cellulose Produced by Different Processing Methods. Cellulose 2011, 18, 1097–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, E.; Peresin, M.S.; Sampson, W.W.; Hoeger, I.C.; Vartiainen, J.; Laine, J.; Rojas, O.J. Comprehensive Elucidation of the Effect of Residual Lignin on the Physical, Barrier, Mechanical and Surface Properties of Nanocellulose Films. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 1853–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanhikoski, S.; Solala, I.; Lahtinen, P.; Niemelä, K.; Vuorinen, T. Fibrillation and Characterization of Lignin-Containing Neutral Sulphite (NS) Pulps Rich in Hemicelluloses and Anionic Charge. Cellulose 2020, 27, 7203–7214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbe, M.A.; Tayeb, P.; Joyce, M.; Tyagi, P.; Kehoe, M.; Dimic-Misic, K.; Pal, L. Rheology of Nanocellulose-Rich Aqueous Suspensions: A Review. Bioresources 2017, 12, 9556–9661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, R.; Trovatti, E.; Pimenta, M.T.B.; Carvalho, A.J.F. Microfibrillated Cellulose from Sugarcane Bagasse as a Biorefinery Product for Ethanol Production. J. Renew. Mater. 2018, 6, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, M.I.; Makarov, I.S.; Golova, L.K.; Gromovykh, P.S.; Kulichikhin, V.G. Rheological Properties of Aqueous Dispersions of Bacterial Cellulose. Processes 2020, 8, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei-Sabet, S.; Martinez, M.; Olson, J. Shear Rheology of Micro-Fibrillar Cellulose Aqueous Suspensions. Cellulose 2016, 23, 2943–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, S.; Yatirajula, S.K.; Saxena, V.K. Evaluation of Linear and Nonlinear Rheology of Microfibrillated Cellulose. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2021, 18, 1401–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenker, M.; Schoelkopf, J.; Gane, P.; Mangin, P. Influence of Shear Rheometer Measurement Systems on the Rheological Properties of Microfibrillated Cellulose (MFC) Suspensions. Cellulose 2018, 25, 961–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iotti, M.; Gregersen, Ø.W.; Moe, S.; Lenes, M. Rheological Studies of Microfibrillar Cellulose Water Dispersions. J. Polym. Environ. 2011, 19, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karppinen, A.; Saarinen, T.; Salmela, J.; Laukkanen, A.; Nuopponen, M.; Seppälä, J. Flocculation of Microfibrillated Cellulose in Shear Flow. Cellulose 2012, 19, 1807–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, P.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, H. Rheology of Cellulose Nanocrystal and Nanofibril Suspensions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 324, 121527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, H.; Gao, M.; Yue, X.; Ni, Y. Redispersion of Dried Plant Nanocellulose: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 294, 119830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinga-Carrasco, G. Optical Methods for the Quantification of the Fibrillation Degree of Bleached MFC Materials. Micron 2013, 48, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Qin, C.; Yang, S.; Song, X.; Wang, S.; Li, K. Enzyme-Assisted Mechanical Grinding for Cellulose Nanofibers from Bagasse: Energy Consumption and Nanofiber Characteristics. Cellulose 2018, 25, 7065–7078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandeirada, C.O.; Merkx, D.W.H.; Janssen, H.-G.; Westphal, Y.; Schols, H.A. TEMPO/NaClO2/NaOCl Oxidation of Arabinoxylans. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 259, 117781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Li, H.; Fu, S.; Lucia, L.A. The Non-Trivial Role of Native Xylans on the Preparation of TEMPO-Oxidized Cellulose Nanofibrils. React. Funct. Polym. 2014, 85, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pääkkönen, T.; Dimic-Misic, K.; Orelma, H.; Pönni, R.; Vuorinen, T.; Maloney, T. Effect of Xylan in Hardwood Pulp on the Reaction Rate of TEMPO-Mediated Oxidation and the Rheology of the Final Nanofibrillated Cellulose Gel. Cellulose 2016, 23, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, B.; Li, Z.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Sheng, N.; Liang, Q.; Wang, H.; Chen, S. A 3D-Printable TEMPO-Oxidized Bacterial Cellulose/Alginate Hydrogel with Enhanced Stability via Nanoclay Incorporation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 238, 116207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.K.; Thakur, M.K.; Gupta, V.K.; Thakur, V.K. Exploring the Role of Nanocellulose as Potential Sustainable Material for Enhanced Oil Recovery: New Paradigm for a Circular Economy. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 183, 1198–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Hyun, J. Rheological Properties of Cellulose Nanofiber Hydrogel for High-Fidelity 3D Printing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 263, 117976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Hirota, M.; Tamura, N.; Isogai, A. Oxidation of Bleached Wood Pulp by TEMPO/NaClO/NaClO2 System: Effect of the Oxidation Conditions on Carboxylate Content and Degree of Polymerization. J. Wood Sci. 2010, 56, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korica, M.; Peršin, Z.; Trifunović, S.; Mihajlovski, K.; Nikolić, T.; Maletić, S.; Fras Zemljič, L.; Kostić, M.M. Influence of Different Pretreatments on the Antibacterial Properties of Chitosan Functionalized Viscose Fabric: TEMPO Oxidation and Coating with TEMPO Oxidized Cellulose Nanofibrils. Materials 2019, 12, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Cheng, W.; Yue, Y.; Xuan, L.; Ni, X.; Han, G. Electrospun Cellulose Nanocrystals/Chitosan/Polyvinyl Alcohol Nanofibrous Films and Their Exploration to Metal Ions Adsorption. Polymers 2018, 10, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanjanzadeh, H.; Park, B.-D. Characterization of Carboxylated Cellulose Nanocrystals from Recycled Fiberboard Fibers Using Ammonium Persulfate Oxidation. J. Korean Wood Sci. Technol. 2020, 48, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.L.; Mandal, H.B.; Sarkar, S.M.; Kabir, M.N.; Farid, E.M.; Arshad, S.E.; Musta, B. Synthesis of Tapioca Cellulose-Based Poly(Hydroxamic Acid) Ligand for Heavy Metals Removal from Water. J. Macromol. Sci. Part Pure Appl. Chem. 2016, 53, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Guerrero, L.; Toxqui-Terán, A.; Pérez-Camacho, O. One-Pot Isolation of Nanocellulose Using Pelagic Sargassum spp. from the Caribbean Coastline. J. Appl. Phycol. 2022, 34, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, A.D. Idealized Powder Diffraction Patterns for Cellulose Polymorphs. Cellulose 2014, 21, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Chen, P.; Li, L.; Nishiyama, Y.; Yang, X. Planar and Uniplanar Orientation in Nanocellulose Films: Interpretation of 2D Diffraction Patterns Step-by-Step. Cellulose 2023, 30, 8151–8159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; Xiang, Z.; Mo, L. Research on Cellulose Nanocrystals Produced from Cellulose Sources with Various Polymorphs. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 33486–33493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Hu, F.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, B.; Chen, K. Isolation and Rheological Characterization of Cellulose Nanofibrils (CNFs) Produced by Microfluidic Homogenization, Ball-Milling, Grinding and Refining. Cellulose 2021, 28, 3389–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Becerra, E.; Osorio, M.; Marín, D.; Gañán, P.; Pereira, M.; Builes, D.; Castro, C. Isolation of Cellulose Microfibers and Nanofibers by Mechanical Fibrillation in a Water-Free Solvent. Cellulose 2023, 30, 4905–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Su, Y.; Xiao, H. Preparation and Characterization of Nanofibrillated Cellulose from Waste Sugarcane Bagasse by Mechanical Force. Bioresources 2020, 15, 6636–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehman, N.V.; Aguerre, Y.S.; Vallejos, M.E.; Felissia, F.E.; Area, M.C. Nanocellulose Addition to Recycled Pulps in Two Scenarios Emulating Industrial Processes for the Production of Paperboard. Maderas, Cienc. Tecnol. 2023, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos, M.E.; Felissia, F.E.; Area, M.C.; Ehman, N.V.; Tarrés, Q.; Mutjé, P. Nanofibrillated Cellulose (CNF) from Eucalyptus Sawdust as a Dry Strength Agent of Unrefined Eucalyptus Handsheets. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 139, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Wang, W.; Teng, A.; Zhang, K.; Ma, Y.; Duan, S.; Li, S.; Guo, Y. Using Cellulose Nanofibers to Reinforce Polysaccharide Films: Blending vs Layer-by-Layer Casting. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 227, 115264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Microfibrillation Time (min) | Dynamic Viscosity (Pa.s) * |

|---|---|---|

| GVL MFC | 75 | 22.1 ± 0.47 |

| Control MFC | 20 | 22.5 ± 0.88 |

| GVL NFC | Control NFC | |

|---|---|---|

| Carboxylic groups (µeq/g) | 944 ± 1.80 | 1245 ± 6.10 |

| Cationic demand (µeq/g) | 2977 | 2981 |

| Transmittance at 600 nm (%) | 59.8 ± 0.60 | 46.9 ± 0.10 |

| Turbidity (NTU) | 49.4 ± 0.30 | 82.7 ± 0.10 |

| Viscosity at 0.51 s−1 (Pa.s) | 1701 ± 63.8 | 982 ± 149 |

| Viscosity at 5.10 s−1 (Pa.s) | 181 ± 0.67 | 106 ± 0.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González, R.G.; Ehman, N.; Felissia, F.E.; Vallejos, M.E.; Area, M.C. γ-Valerolactone Pulping as a Sustainable Route to Micro- and Nanofibrillated Cellulose from Sugarcane Bagasse. Processes 2025, 13, 4065. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124065

González RG, Ehman N, Felissia FE, Vallejos ME, Area MC. γ-Valerolactone Pulping as a Sustainable Route to Micro- and Nanofibrillated Cellulose from Sugarcane Bagasse. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4065. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124065

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález, Roxana Giselle, Nanci Ehman, Fernando Esteban Felissia, María Evangelina Vallejos, and María Cristina Area. 2025. "γ-Valerolactone Pulping as a Sustainable Route to Micro- and Nanofibrillated Cellulose from Sugarcane Bagasse" Processes 13, no. 12: 4065. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124065

APA StyleGonzález, R. G., Ehman, N., Felissia, F. E., Vallejos, M. E., & Area, M. C. (2025). γ-Valerolactone Pulping as a Sustainable Route to Micro- and Nanofibrillated Cellulose from Sugarcane Bagasse. Processes, 13(12), 4065. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124065