Torsional Stick–Slip Modeling and Mitigation in Horizontal Wells Considering Non-Newtonian Drilling Fluid Damping and BHA Configuration

Abstract

1. Introduction

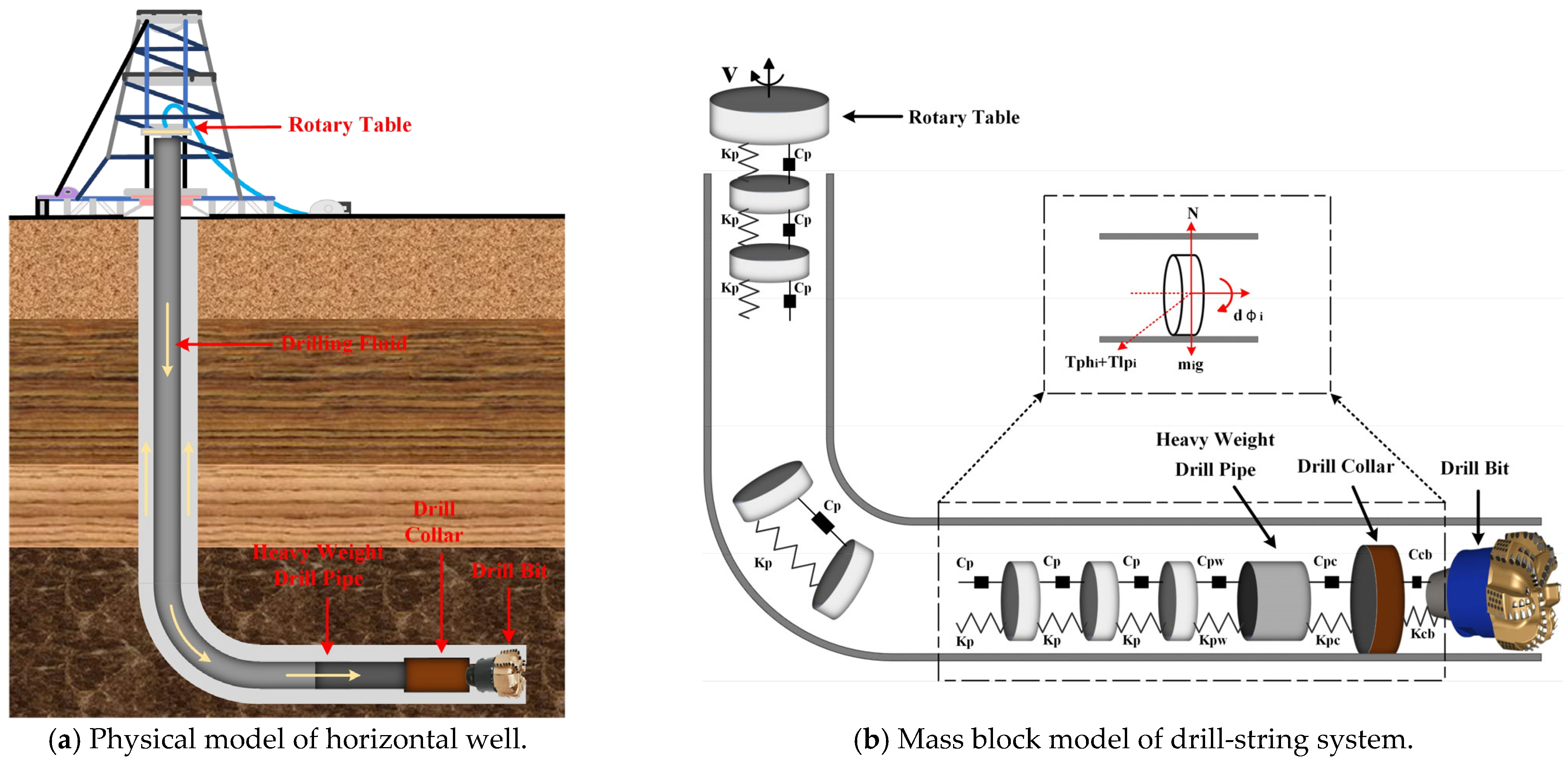

2. Stick–Slip Vibration Model of Horizontal-Well Drill-String System

2.1. Establishment of Stick–Slip Vibration Model

- (1)

- The influence of lateral vibration on torsional vibration is disregarded.

- (2)

- The effect of an oil-based drilling fluid on the drill string is equivalent to a non-Newtonian rheological damping force.

- (3)

- The drill bit, drill collars, heavyweight drill pipe (HWDP), and drill pipe are considered N mass blocks with concentrated inertia, connected by springs and dampers.

- (4)

- The friction between the drill bit and the rock is represented by a concentrated friction torque.

2.1.1. Friction Torque

2.1.2. Drill-String System Parameters

- (1)

- Drill-string stiffness coefficient, K:

- (2)

- Drill-string damping coefficient, C:

- (3)

- Moment of inertia, J:

2.1.3. Drilling-Fluid Damping

2.1.4. Stick–Slip Vibration Grade

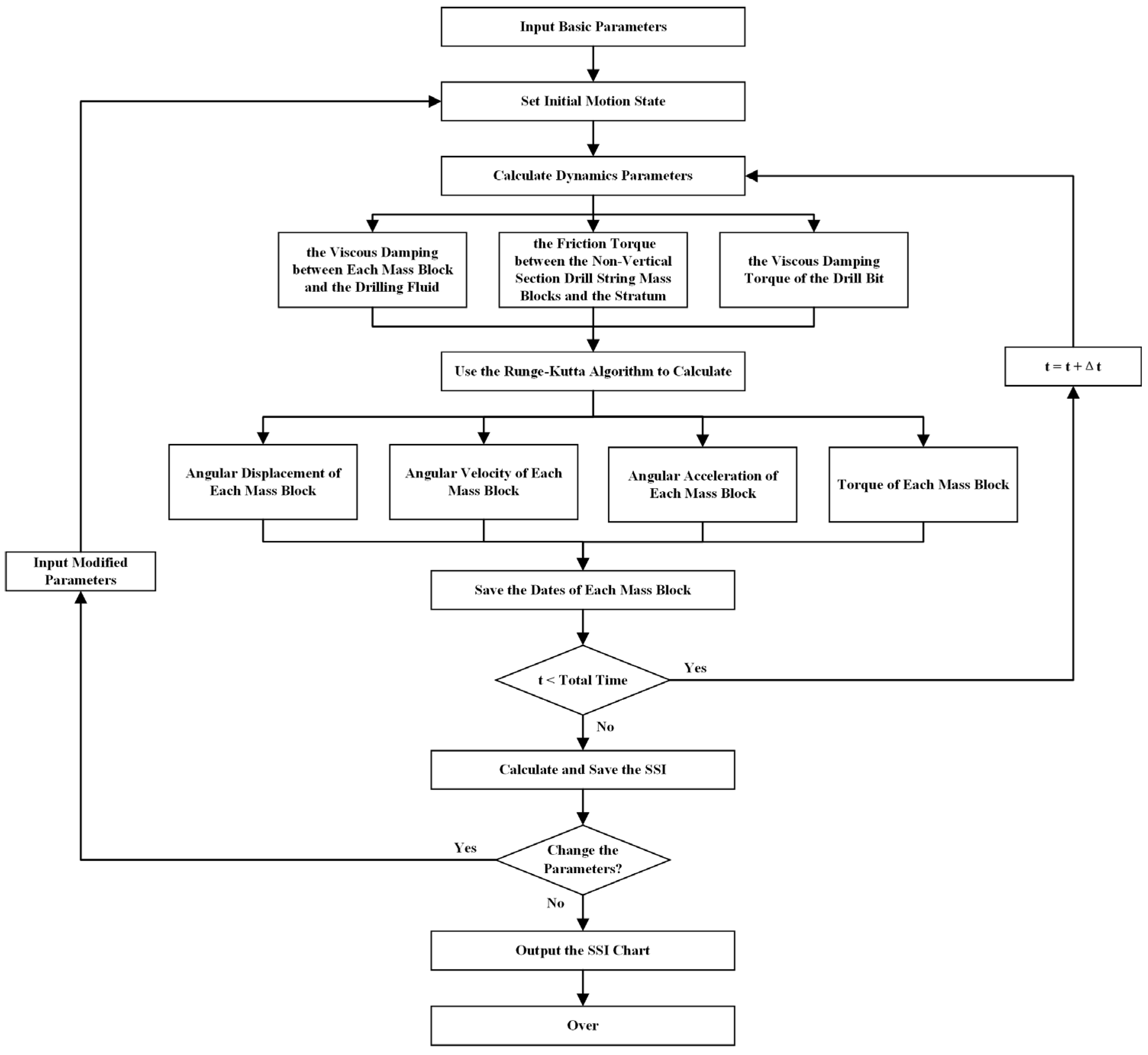

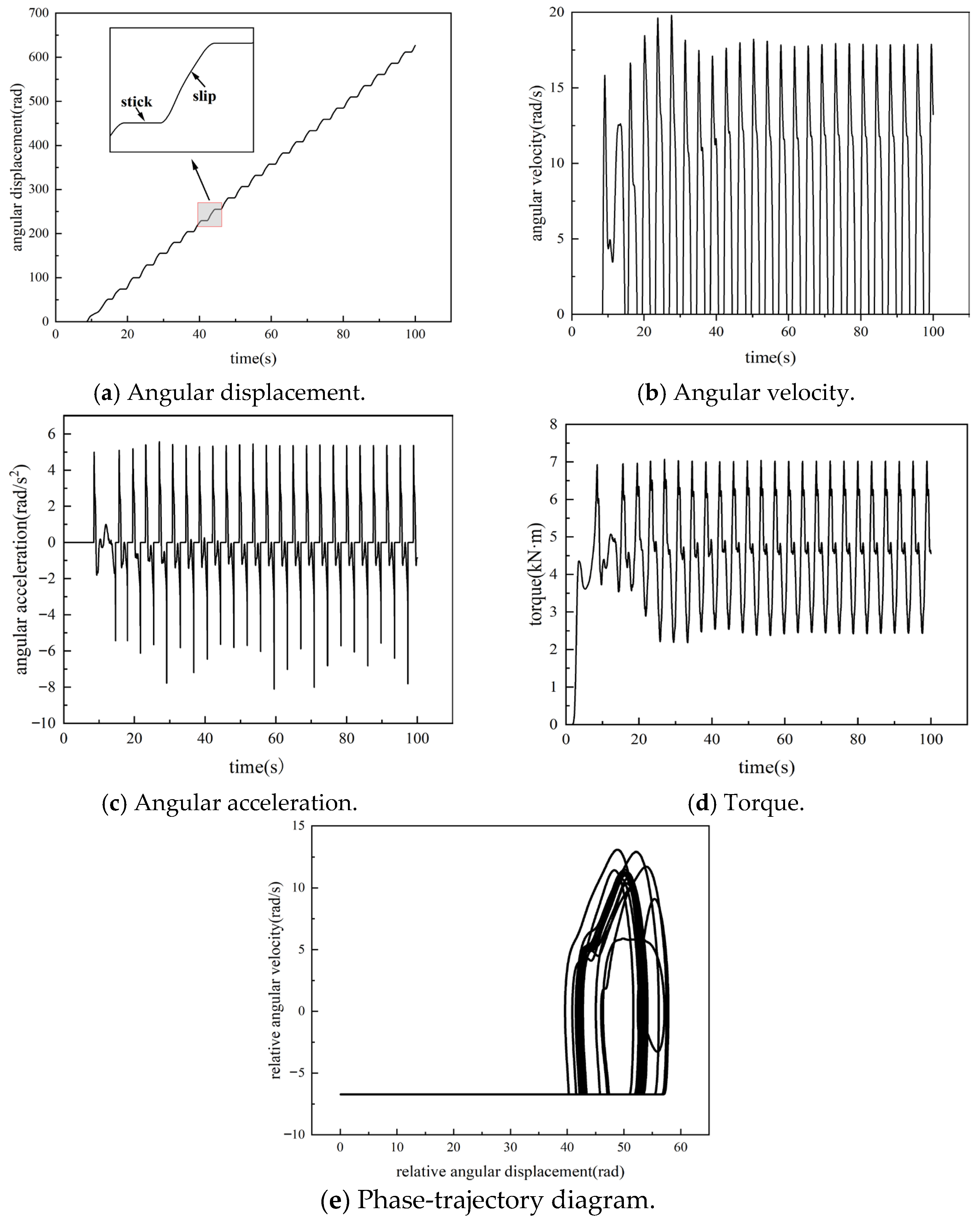

2.2. Solution of the Stick–Slip Vibration Model

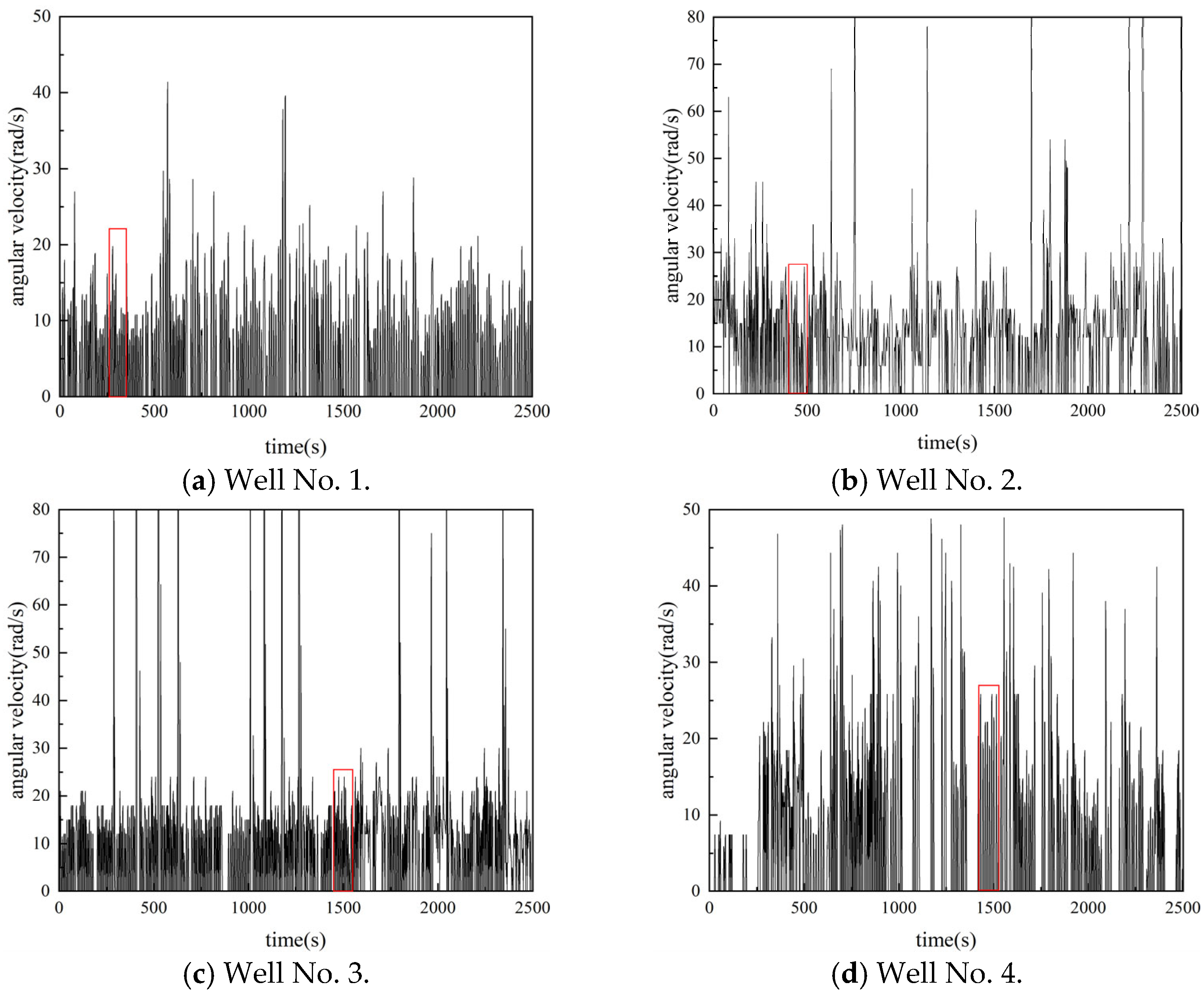

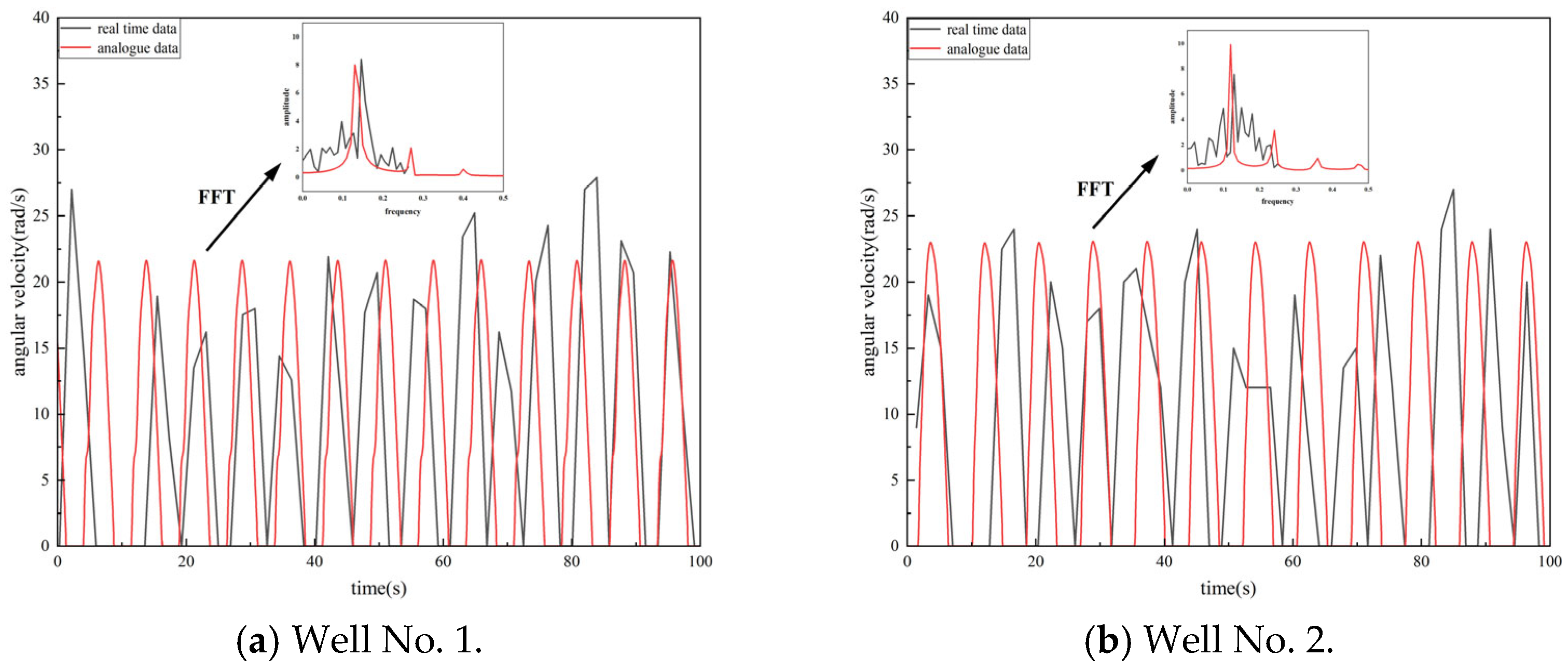

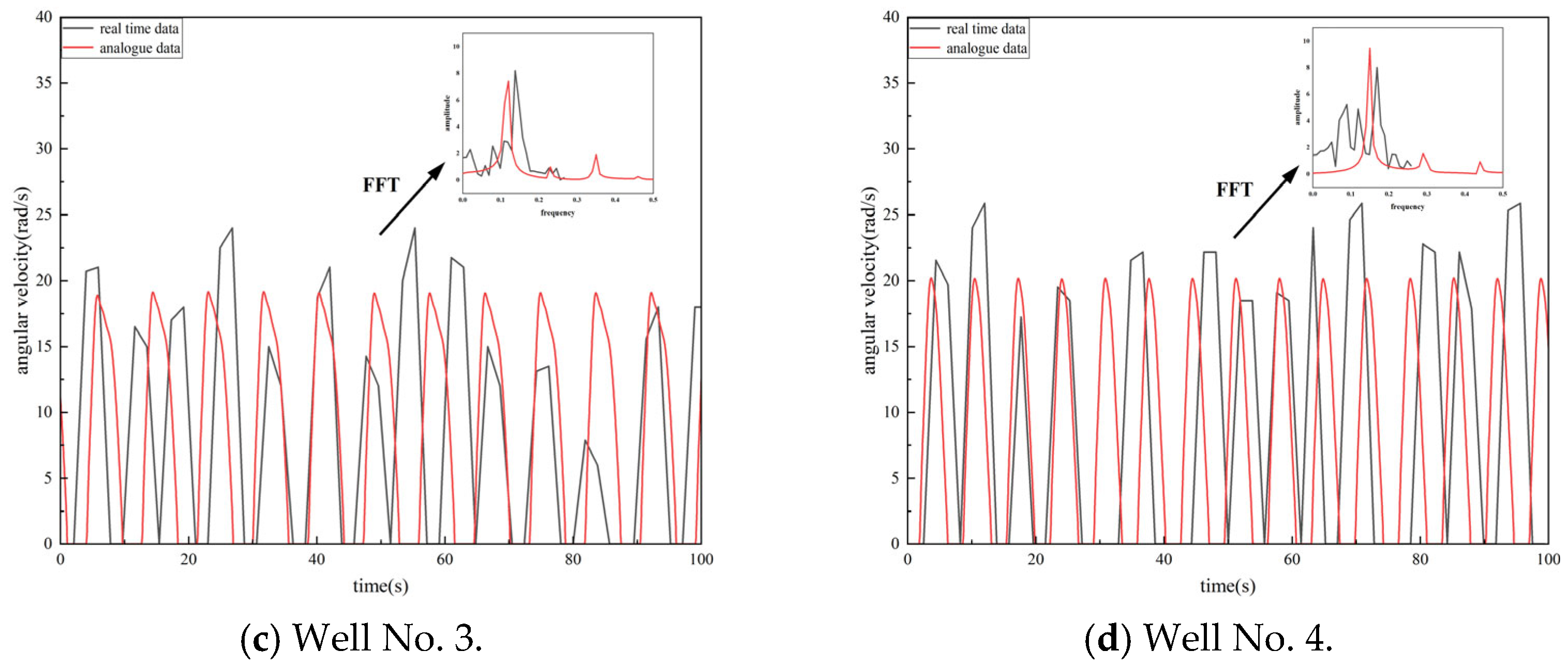

2.3. Verification of the Stick–Slip Vibration Model

3. Analysis of Factors That Affect Stick–Slip Vibration in the Horizontal-Well Drill-String System

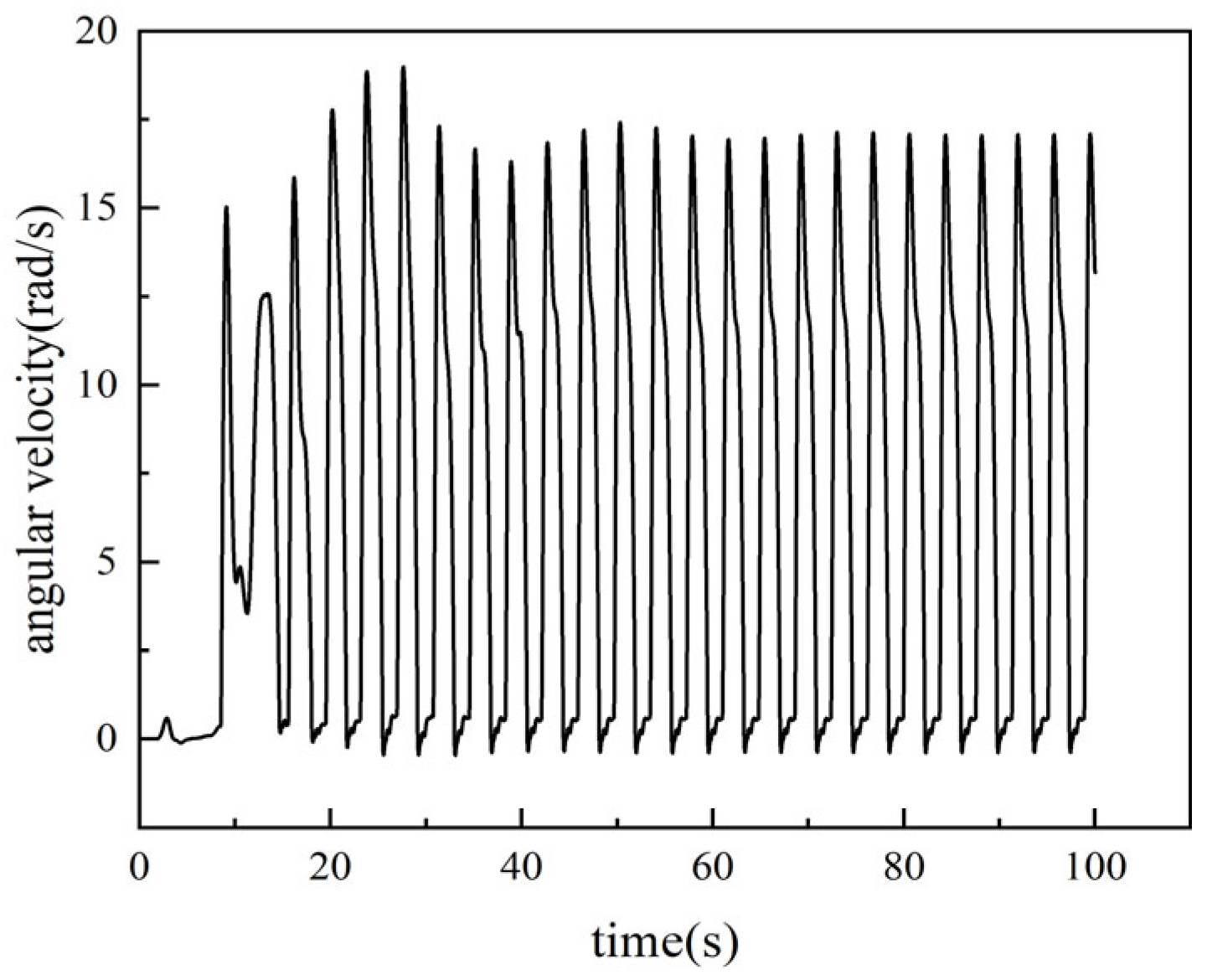

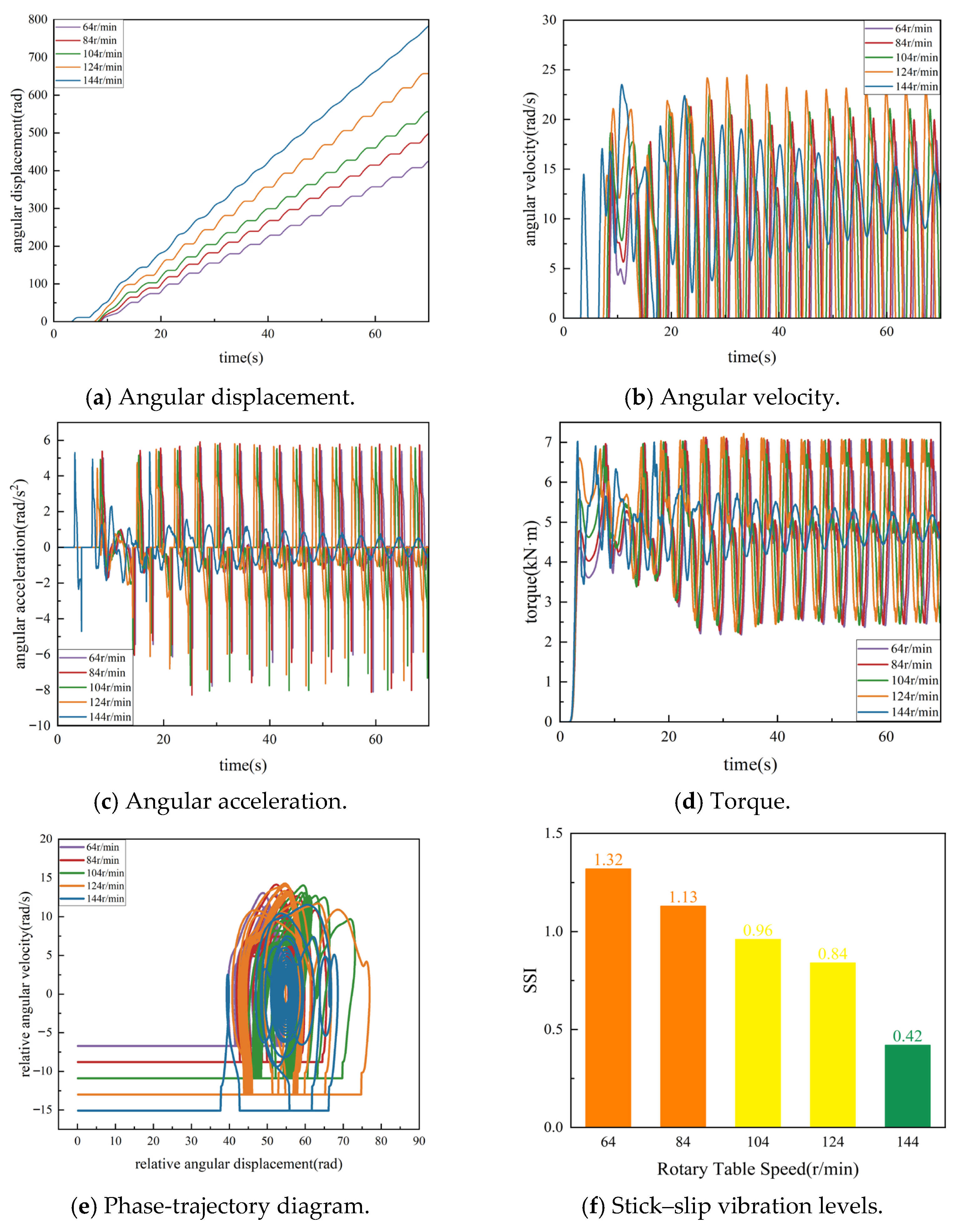

3.1. Effect of Rotary Table Speed

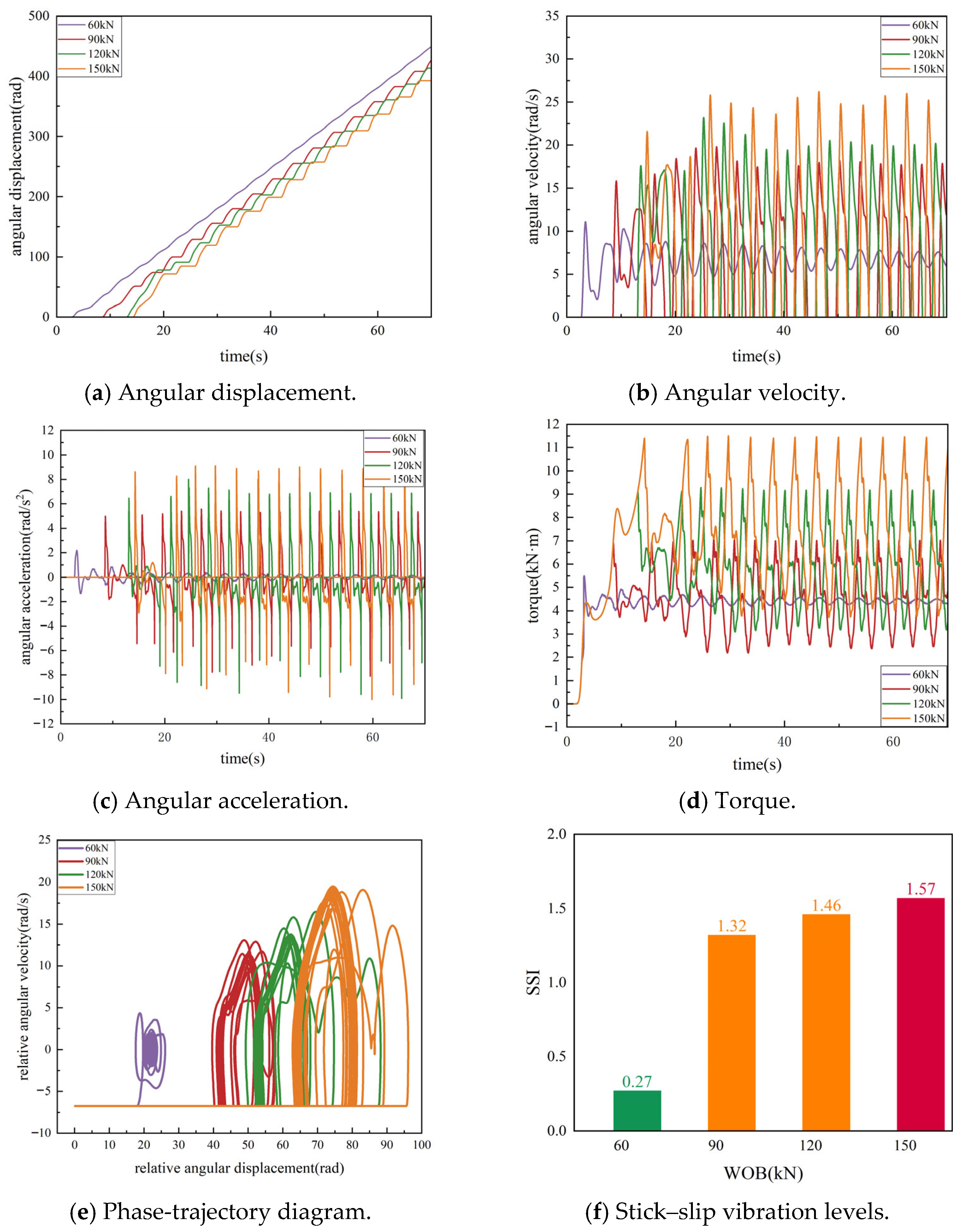

3.2. Effect of WOB

3.3. Effect of BHA

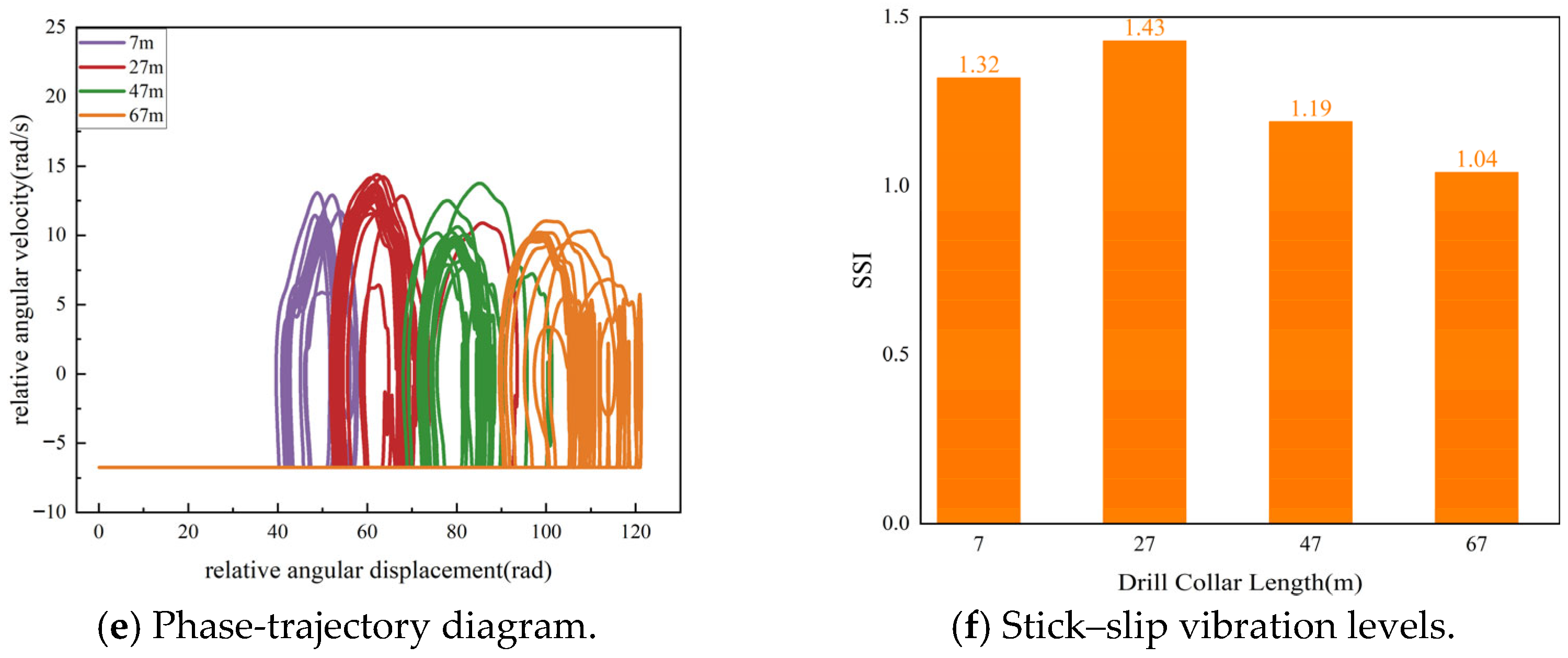

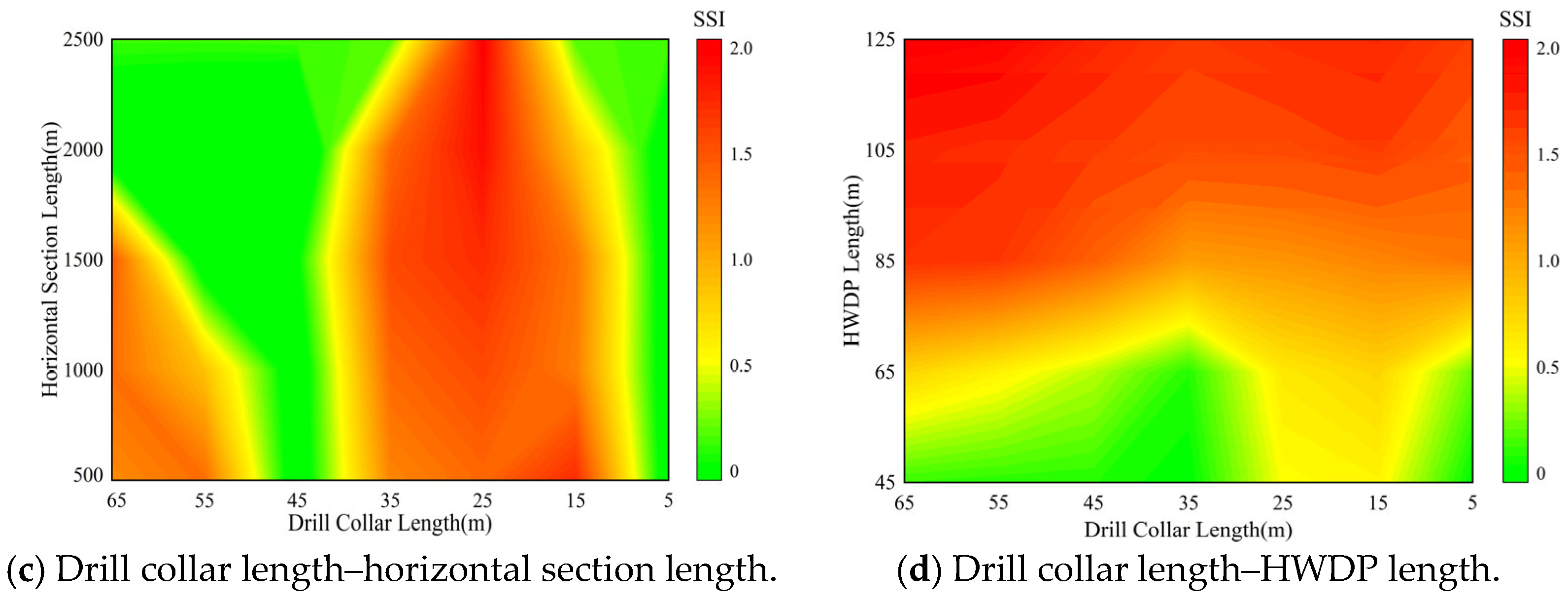

3.3.1. Drill Collar Length

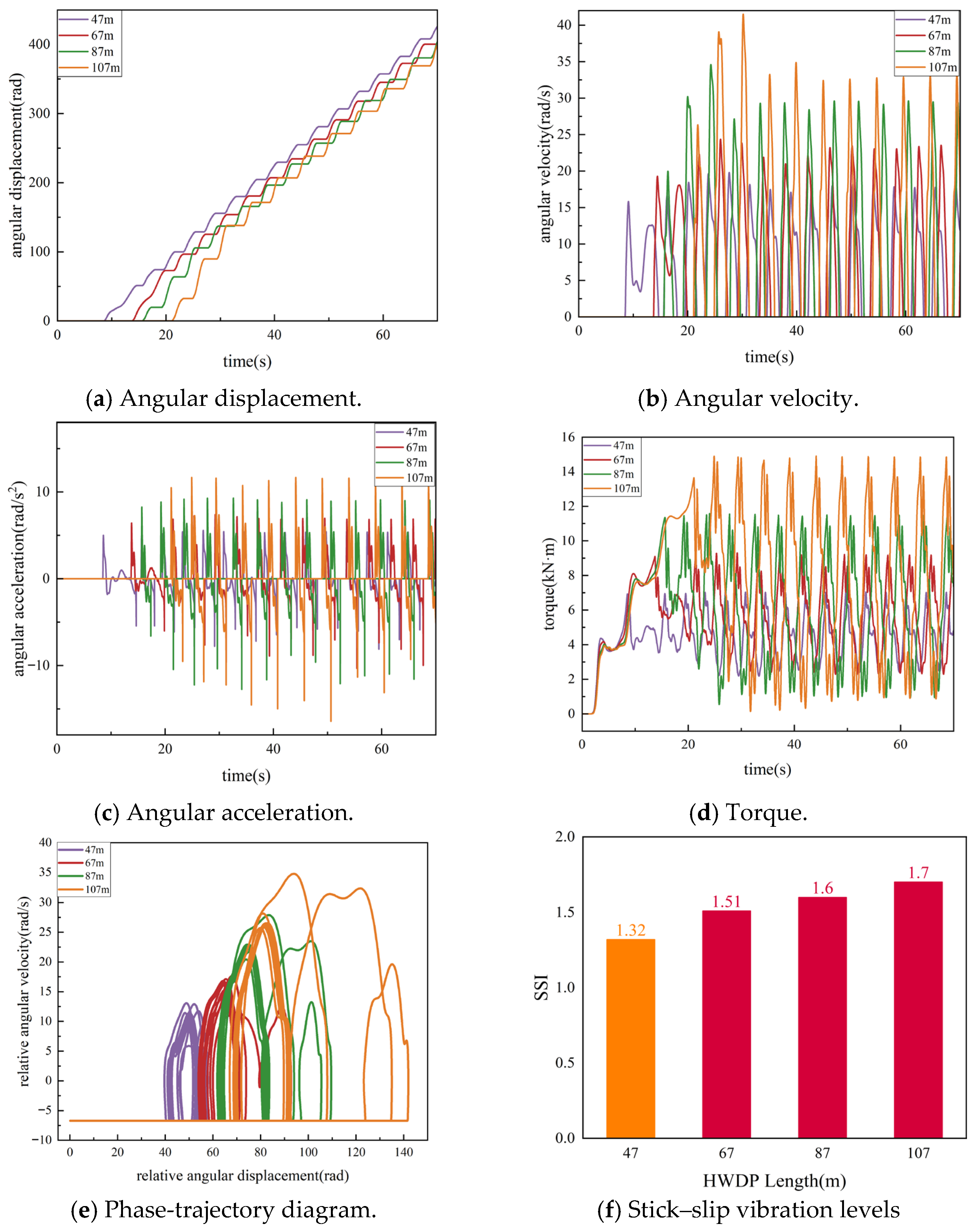

3.3.2. HWDP Length

4. Stick–Slip Vibration-Mitigation Method

- (1)

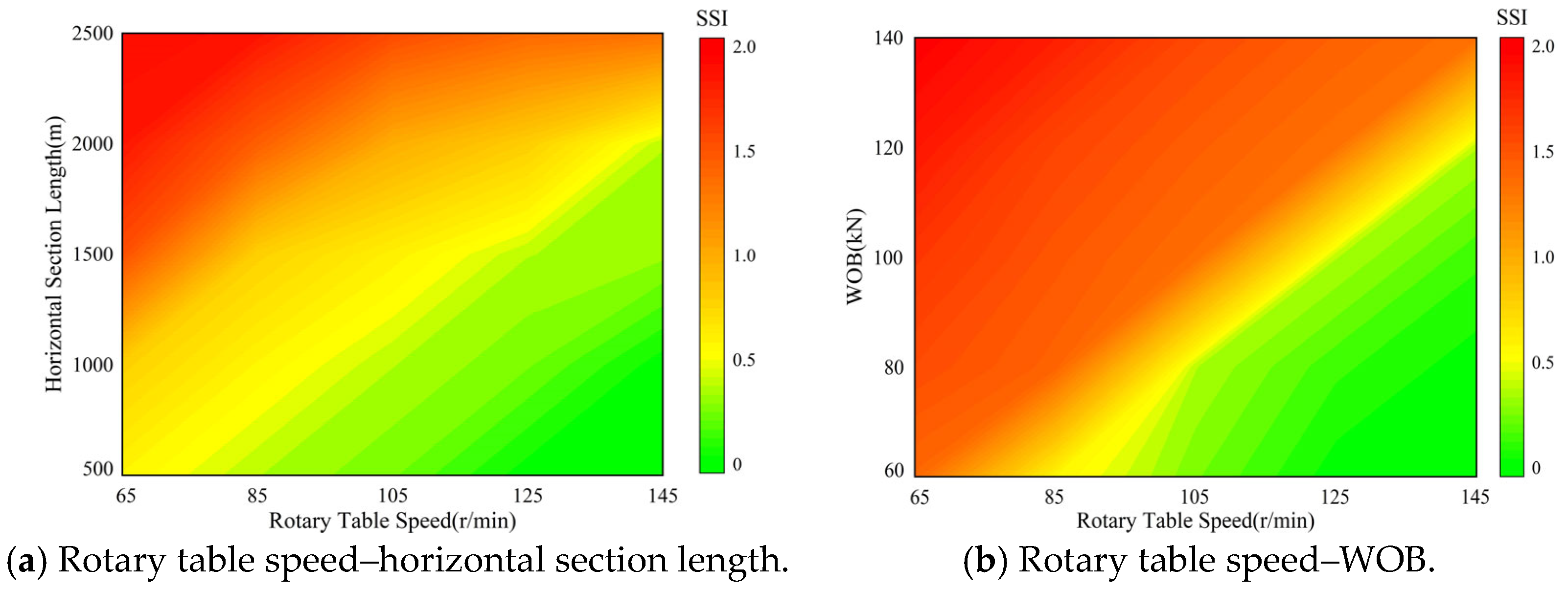

- Improving Drilling Parameters

- (2)

- Optimizing BHA Configuration

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Rotary table speed has a dominant influence on torsional stick–slip. Low rotary speeds lead to long stick durations, large oscillations of bit angular velocity and torque, and a high Stick–Slip Index (SSI), whereas increasing the rotary speed within a suitable range effectively weakens stick–slip. However, excessively high speed may induce severe bit bounce, suggesting that an optimal speed window should be selected rather than simply maximizing speed.

- (2)

- For the case of horizontal well analyzed in this study, the WOB mainly affects stick–slip through the bit–rock interaction. The simulation results show that when WOB is reduced to about 60 kN, the torsional stick–slip vibration at the bit can be effectively eliminated and the SSI approaches zero, indicating that lowering the WOB is an efficient way to suppress stick–slip in this operating condition. However, such a low WOB also reduces the depth of cut and mechanical rate of penetration, implying that, in field practice, a compromise must be made between stick–slip mitigation and drilling efficiency when selecting the WOB.

- (3)

- BHA configuration, particularly drill collar and HWDP lengths, significantly affects the distribution of torsional stiffness and inertia along the string. Appropriately increasing the drill collar and HWDP length improves the rigidity of the lower BHA, smooths the bit rotational response, and reduces SSI, whereas unreasonable configurations may intensify torsional transients. By combining the SSI with the proposed model, stick–slip severity maps are constructed for different combinations of rotary speed, WOB, BHA parameters, and horizontal section length, providing a simple and practical tool for parameter and BHA optimization in horizontal wells.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| V | Rotary table speed | rad/s |

| J | Moment of inertia | kg·m2 |

| K | Spring stiffness | N·m/rad |

| C | Spring damping | N·m·s/rad |

| φ | Angular displacement | rad |

| Angular velocity | rad/s | |

| Angular acceleration | rad/s2 | |

| Tfb | Friction torque between the drill bit and rock | N·m |

| Th | Friction torque between horizontal-section mass blocks and formation | N·m |

| Tr | Torque transmitted from drill string to bit | N·m |

| Tsb | Maximum static friction torque | N·m |

| Tcb | Coulomb friction torque | N·m |

| ΔV | Zero-velocity interval threshold | rad/s |

| μsb | Maximum static friction coefficient | — |

| μcb | Sliding friction coefficient | — |

| Rb | Drill bit radius | m |

| ρ | Steel density | kg·m3 |

| cl | Damping coefficient per unit length of drill string | N·s/rad |

| G | Shear modulus of steel | Pa |

| Cl | Non-Newtonian rheological damping | N·m·s/rad |

Abbreviations

| BHA | Bottom-hole assembly |

| HWDP | Heavy-weight drill pipe |

| WOB | Weight on bit |

| SSI | Stick–Slip Index |

| HBNR | Herschel–Bulkley non-Newtonian |

| FEM | Finite element method |

| PDC | Polycrystalline diamond compact |

| ROP | Rate of penetration |

| DOF | Degree of freedom |

References

- Xie, D.; Huang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Vaziri, V.; Kapitaniak, M.; Wiercigroch, M. Nonlinear dynamics of lump mass model of drill-string in horizontal well. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 174, 105450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Tang, L.; Yang, Q. A literature review of approaches for stick-slip vibration suppression in oilwell drillstring. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2014, 6, 967952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, D.; Lu, B.; Zeng, Y.; Ding, S.; Zhou, S. A prediction model of the shortest drilling time for horizontal section in extended-reach well. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 182, 106319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, G.; He, K.; Ye, C. Practice and understanding of sidetracking horizontal drilling in old wells in Sulige Gas Field, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2019, 46, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabali, F.; Moradi, H.; Vossoughi, G. Coupling analysis and control of axial and torsional vibrations in a horizontal drill string. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 195, 107534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moraes, L.P.; Savi, M.A. Drill-string vibration analysis considering an axial-torsional-lateral nonsmooth model. J. Sound Vib. 2019, 438, 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, F.; Lobo, D.; Ritto, T.; Pinto, F. Experimental analysis of stick-slip in drilling dynamics in a laboratory test-rig. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 170, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigit, A.S.; Christoforou, A.P. Christoforou. Stick-slip and bit-bounce interaction in oil-well drillstrings. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2006, 128, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divenyi, S.; Savi, M.A.; Wiercigroch, M.; Pavlovskaia, E. Drill-string vibration analysis using non-smooth dynamics approach. Nonlinear Dyn. 2012, 70, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M.; Rideout, D.G.; Butt, S.D. Advantages of an lqr controller for stick-slip and bit-bounce mitigation in an oilwell drillstring. In Proceedings of the ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, Houston, TX, USA, 9–15 November 2012; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2012. Volume 45202. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Di, Q.; Li, N.; Wang, W.; Chen, F. Measurement and simulation of nonlinear drillstring stick-slip and whirling vibrations. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2020, 125, 103528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omojuwa, E.; Osisanya, S.; Ahmed, R. Measuring and controlling torsional vibrations and stick-slip in a viscous-damped drillstring model. In Proceedings of the International Petroleum Technology Conference, Bangkok, Thailand, 15–17 November 2011; IPTC: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Moharrami, M.J.; de Arruda Martins, C.; Shiri, H. Nonlinear integrated dynamic analysis of drill strings under stick-slip vibration. Appl. Ocean. Res. 2021, 108, 102521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wisinger, J.; Dunbar, B.; Propes, C. Identification and mitigation of friction-and cutting-action-induced stick/slip vibrations with PDC bits. SPE Drill. Complet. 2020, 35, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Long, X.; Zheng, X.; Meng, G.; Balachandran, B. Spatial-temporal dynamics of a drill string with complex time-delay effects: Bit bounce and stick-slip oscillations. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 170, 105338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, S.; Yang, Y.; Dai, L. Study of stick-slip suppression and robustness to parametric uncertainty in drill strings containing torsional vibration tool using sliding-mode control. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part K J. Multi-Body Dyn. 2021, 235, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaodong, Z.; Xiaofeng, Z.H.; Shi, H.E. Stability analysis of stick-slip vibration and discussion of vibration reduction method of drill string system. Drill. Prod. Technol. 2015, 2, 89–90. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; Zhong, X.; Liu, S.; Ji, Z.H. Analysis of stick-slip vibration characteristics of deep well drill string. Oil Field Equip. 2018, 47, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Liu, J.; Li, Q. Analysis on Coupled Axial-Torsional Stick Slip Vibration Behaviors of Drill String in Deep Well. China Pet. Mach. 2023, 51, 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Liu, X.; Song, G.; Zhou, S. Non-linear dynamic analysis of drill string system with fluid-structure interaction. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Liu, G.; Zhu, J.; Cai, X.; Men, M.; Liang, L.; Wang, A.; Xu, B. Stick–Slip Prevention of Drill Strings Using Model Predictive Control Based on a Nonlinear Finite Element Reduced-Order Model. Processes 2025, 13, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, P.; Roychoudhury, I.; Chatar, C.; Celaya, J. A Hybrid Physics-Based and Machine-Learning Approach for Stick/Slip Prediction. In Proceedings of the SPE/IADC Drilling Conference and Exhibition, Galveston, TX, USA, 8–10 March 2022; SPE: Richardson, TX, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Elahifar, B.; Hosseini, E. A new approach for real-time prediction of stick–slip vibrations enhancement using model agnostic and supervised machine learning: A case study of Norwegian continental shelf. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2024, 14, 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandikota, R.A.; Chennoufi, N.; Saxena, S.; Schellenberg, B.; Groover, A. Drilling Digital Twin Predicts Drilling Dysfunctions and Performance in Real Time. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2–5 October 2023; SPE: Richardson, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Xue, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Shan, Y. Pattern recognition of stick-slip vibration in combined signals of DrillString vibration. Measurement 2022, 204, 112034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Lu, J.; Li, W.; Xue, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, F. Automated classification of drill string vibrations using machine learning algorithms. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 239, 212995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnopp, D. Computer simulation of stick-slip friction in mechanical dynamic systems. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 1985, 107, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newland, D.E. Mechanical Vibration Analysis and Computation; Courier Corporation: Chelmsford, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Al Dushaishi, M.F.; Nygaard, R.; Stutts, D.S. Effect of drilling fluid hydraulics on drill stem vibrations. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 30, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzek, A.; Shufrin, I.; Pasternak, E.; Dyskin, A.V. Influence of drilling mud rheology on the reduction of vertical vibrations in deep rotary drilling. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2015, 135, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, C.; Millwater, H.; Gray, K. Classification of drilling stick slip severity using machine learning. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 179, 1023–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, J.M.; Yigit, A.S. Modeling and analysis of stick-slip and bit bounce in oil well drillstrings equipped with drag bits. J. Sound Vib. 2014, 333, 6885–6899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zou, Z.; Huang, B.; Ma, L.; Xia, J. Downhole vibration causing a drill collar failure and solutions. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2017, 4, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dareing, D.W. Drill collar length is a major factor in vibration control. J. Pet. Technol. 1984, 36, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.; Al Dushaishi, M.F.; Khan, M.F.M.H. Experimental investigation of drillstring torsional vibration effect on rate of penetration with PDC bits in hard rock. Geothermics 2022, 103, 102410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Z.; Huang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Wu, X.; Li, G.; Song, X. Experimental study on dynamic characteristics of axial-torsional coupled percussive drilling. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 219, 111094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SSI | Stick–Slip Level | Color | Guidance/Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| <0.5 | Low | Green | Can drill normally |

| 0.5–1.0 | Medium | Yellow | For continuous operation over 25 h, risk of failure is medium |

| 1.0–1.5 | High | Orange | For continuous operation over 12 h, risk of failure is high |

| >1.5 | Severe | Red | For continuous operation over 0.5 h, risk of failure is severe |

| Serial Number | Test Well Depth (m) | Kick-Off Point (m) | WOB (kN) | Rotary Table Speed (r/min) | Rotational Viscometer Reading | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| at 3 rpm | at 100 rpm | at 200 rpm | |||||

| 1 | 3815 | 3700 | 74 | 72 | 3 | 30 | 53 |

| 2 | 4750 | 3548 | 132 | 91 | 6 | 32 | 58 |

| 3 | 5195 | 3617 | 79 | 80 | 6 | 32 | 57 |

| 4 | 3910 | 3720 | 73 | 59 | 7 | 40 | 62 |

| Well | Dominant Frequency (Hz) | Error (%) | Amplitude | Error (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Date | Simulated Date | Measured Date | Simulated Date | |||

| Well No. 1 | 0.161 | 0.148 | 8.07 | 8.19 | 8.05 | 8.05 |

| Well No. 2 | 0.140 | 0.132 | 5.71 | 8.12 | 9.77 | 16.88 |

| Well No. 3 | 0.148 | 0.129 | 12.84 | 8.01 | 7.89 | 1.50 |

| Well No. 4 | 0.184 | 0.169 | 8.15 | 7.98 | 9.23 | 15.66 |

| Drilling Sequence | Casing Name | Well Depth (m) | Borehole Size (mm) | Casing O.D. | Casing Down Depth | Casing Roof Depth | Casing I.D. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Spud | Conductor Pipe | 148.60 | 660.40 | 508.00 | 148.19 | 0.00 | 485.70 |

| Second Spud | Surface Casing | 967.00 | 444.50 | 339.70 | 966.70 | 0.00 | 315.32 |

| Third Spud | Intermediate Casing | 2525.00 | 311.20 | 244.50 | 2524.10 | 1346.91 | 220.50 |

| Third Spud | Intermediate Casing | 2525.00 | 311.20 | 250.83 | 1346.91 | 0.00 | 220.51 |

| Name of Drilling Tools × Specification | O.D. (mm) | I.D. (mm) | Length (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDC Bit × Z516 | 215.90 | 0.24 | |

| Rotary Steerable Tool | 172.00 | 4.27 | |

| Stabilizer Joint | 172.00 | 0.82 | |

| MWD Hang-Off Sub | 172.00 | 60.00 | 4.41 |

| Nonmagnetic Drill Collar | 171.50 | 57.20 | 7 |

| Screen Sub | 172.00 | 75.00 | 0.95 |

| Sloped HWDP × S135I | 127.00 | 76.20 | 28.68 |

| Sloped HWDP × S135I | 127.00 | 76.20 | 18.88 |

| Drill Pipe × S135s | 127.00 | 108.60 | 5774.87 |

| Parameter | Well Depth | Kick-Off Point | Rotary Table Speed | WOB | Rotational Viscometer Reading | Dynamic Friction Coefficient | Static Friction Coefficient | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| at 3 rpm | at 100 rpm | at 200 rpm | |||||||

| Value | 5820 m | 3306 m | 64 r/min | 90 kN | 7 | 41 | 69 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, X.; Lin, B.; Meng, F.; Song, X.; Li, Z. Torsional Stick–Slip Modeling and Mitigation in Horizontal Wells Considering Non-Newtonian Drilling Fluid Damping and BHA Configuration. Processes 2025, 13, 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124051

Han X, Lin B, Meng F, Song X, Li Z. Torsional Stick–Slip Modeling and Mitigation in Horizontal Wells Considering Non-Newtonian Drilling Fluid Damping and BHA Configuration. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124051

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Xueyin, Botao Lin, Fanhua Meng, Xuefeng Song, and Zhibin Li. 2025. "Torsional Stick–Slip Modeling and Mitigation in Horizontal Wells Considering Non-Newtonian Drilling Fluid Damping and BHA Configuration" Processes 13, no. 12: 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124051

APA StyleHan, X., Lin, B., Meng, F., Song, X., & Li, Z. (2025). Torsional Stick–Slip Modeling and Mitigation in Horizontal Wells Considering Non-Newtonian Drilling Fluid Damping and BHA Configuration. Processes, 13(12), 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124051