Production of Lipids and Carotenoids in Coccomyxa onubensis Under Acidic Conditions in Raceway Ponds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Algae Strain and Cultivation Conditions

2.2. Outdoor Cultivation Experiments

2.3. Light and Transmission Electron Microscopy

2.4. Photosystem II Quantum Yield

2.5. Specific Growth Rate and Productivity

2.6. Gravimetric Analysis

2.7. Pigment Analysis

2.8. Fatty Acid Profile and Total Lipid Analysis

2.9. Statistics

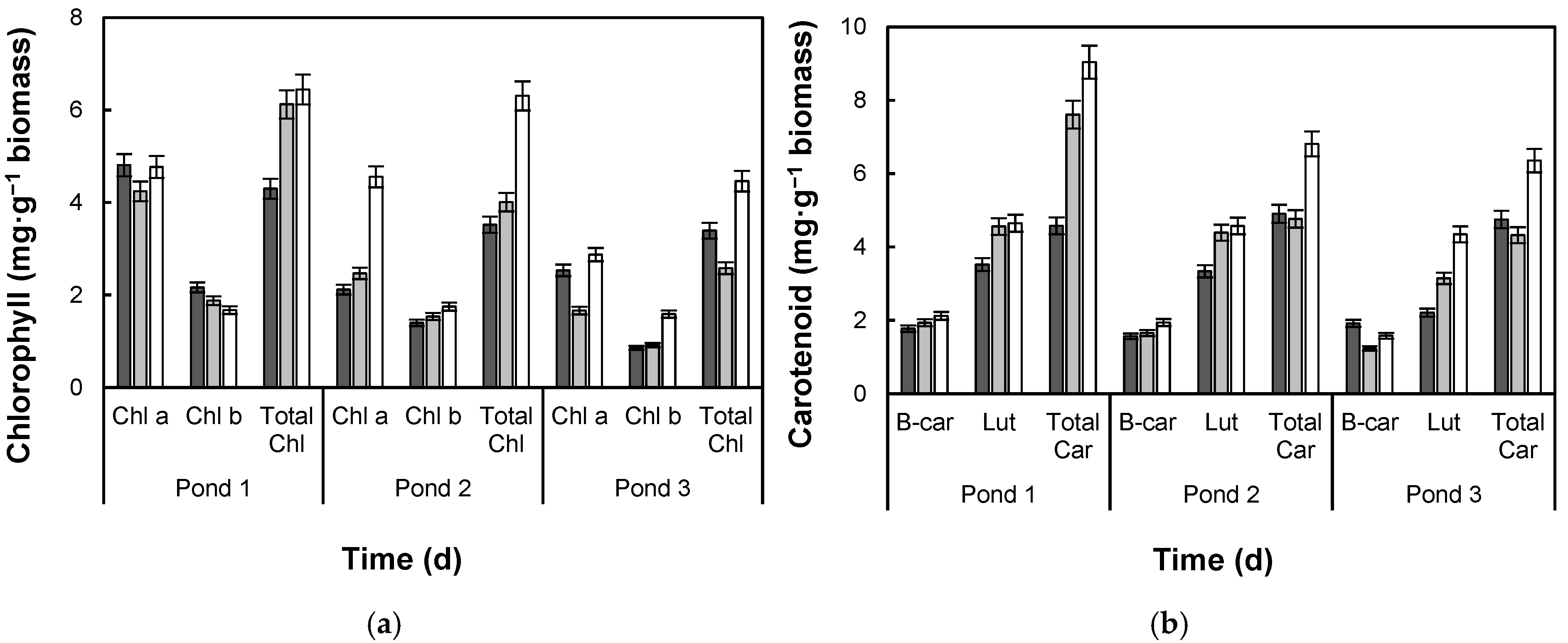

3. Results

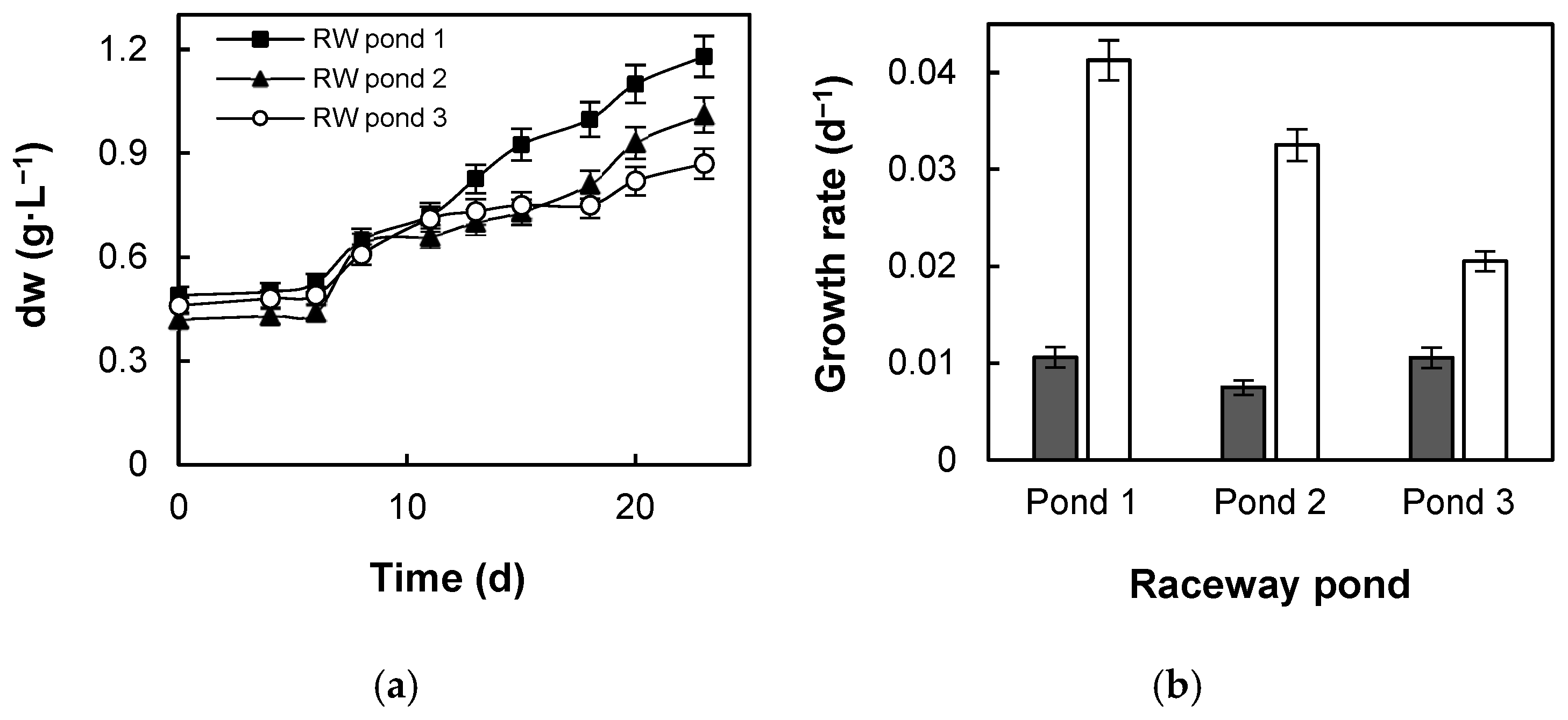

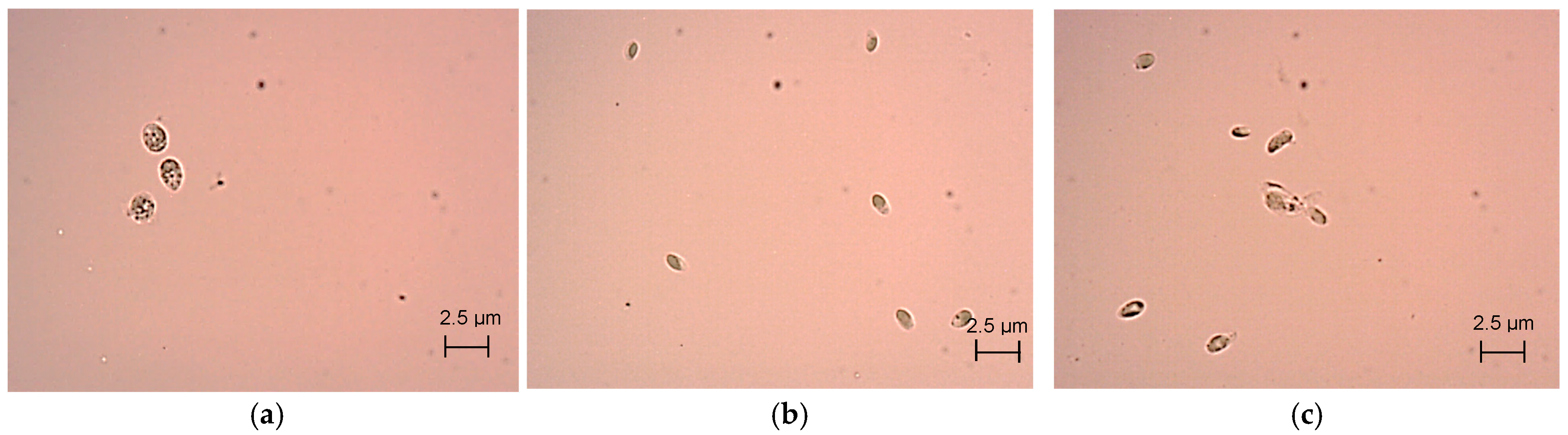

3.1. Coccomyxa Onubensis Biomass Production and Growth Kinetics in Raceway Ponds

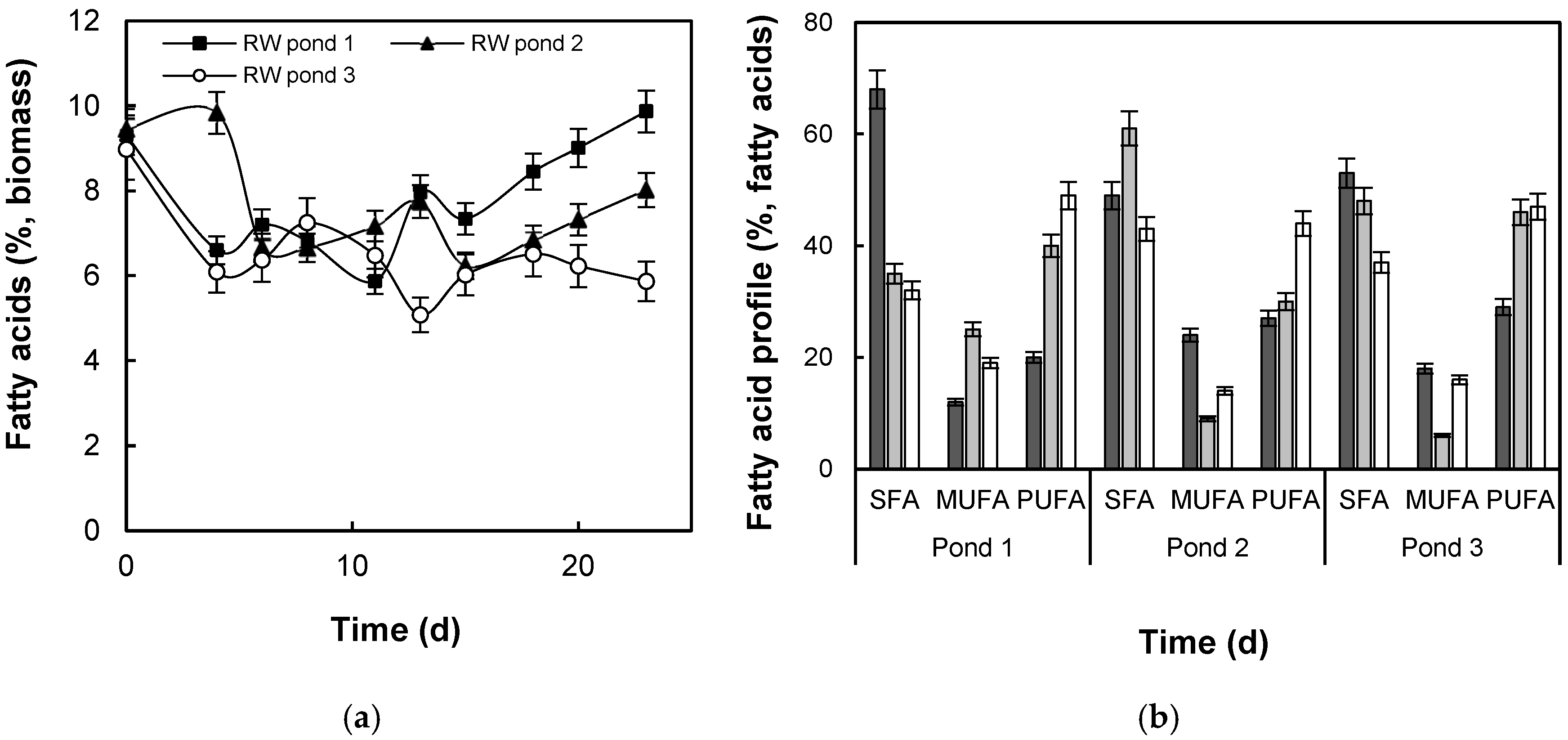

3.2. Lipid Production and Fatty Acid Composition

4. Discussion

4.1. Coccomyxa Onubensis Biomass Production and Growth Kinetics in Raceway Ponds

4.2. Lipid Production and Fatty Acid Composition

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henchion, M.; Hayes, M.; Mullen, A.M.; Fenelon, M.; Tiwari, B. Future Protein Supply and Demand: Strategies and Factors Influencing a Sustainable Equilibrium. Foods 2017, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goiris, K.; Muylaert, K.; Voorspoels, S.; Noten, B.; De Paepe, D.; Baart, G.J.E.; De Cooman, L. Detection of flavonoids in microalgae from different evolutionary lineages. J. Phycol. 2014, 50, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, L.; Tsao, R. Chemistry and biochemistry of dietary carotenoids: Bioaccessibility, bioavailability and bioactivities. J. Food Bioact. 2020, 10, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gálvez, A.; Viera, I.; Roca, M. Carotenoids and Chlorophylls as Antioxidants. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schüler, L.M.; Santos, T.; Pereira, H.; Duarte, P.; Katkam, N.G.; Florindo, C.; Schulze, P.S.C.; Barreira, L.; Varela, J.C.S. Improved production of lutein and β-carotene by thermal and light intensity upshifts in the marine microalga Tetraselmis sp. CTP4. Algal Res. 2020, 45, 101732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santin, A.; Russo, M.T.; Ferrante, M.I.; Balzano, S.; Orefice, I.; Sardo, A. Highly Valuable Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids from Microalgae: Strategies to Improve Their Yields and Their Potential Exploitation in Aquaculture. Molecules 2021, 26, 7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, C.; Mitra, M.; Bhayani, K.; Bharadwaj, S.V.V.; Ghosh, T.; Dubey, S.; Mishra, S. Abiotic stresses as tools for metabolites in microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 244, 1216–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Lan, C.Q.; Horsman, M. Closed photobioreactors for production of microalgal biomasses. Biotechnol. Adv. 2012, 30, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, P.; Meier, L.; Pfeffer, A.; Krüger, K.; Oropeza Vargas, J.E.; Weuster-Botz, D. Lab-scale photobioreactor systems: Principles, applications, and scalability. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 45, 791–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasanasathian, A.; Peng, C.-A. Algal Photobioreactor for Production of Lutein and Zeaxanthin. In Bioprocessing for Value-Added Products from Renewable Resources; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 491–505. [Google Scholar]

- Merino, N.; Aronson, H.S.; Bojanova, D.P.; Feyhl-Buska, J.; Wong, M.L.; Zhang, S.; Giovannelli, D. Living at the Extremes: Extremophiles and the Limits of Life in a Planetary Context. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavasi, V.; Soru, S.; Cao, G. Extremophile Microalgae: The potential for biotechnological application. J. Phycol. 2020, 56, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimmler, H. Acidophilic and Acidotolerant Algae. In Algal Adaptation to Environmental Stresses: Physiological, Biochemical and Molecular Mechanisms; Rai, L.C., Gaur, J.P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 259–290. [Google Scholar]

- Abiusi, F.; Trompetter, E.; Pollio, A.; Wijffels, R.H.; Janssen, M. Acid Tolerant and Acidophilic Microalgae: An Underexplored World of Biotechnological Opportunities. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 820907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.L.; Huss, V.A.R.; Montero, Z.; Torronteras, R.; Cuaresma, M.; Garbayo, I.; Vílchez, C. Phylogenetic characterization and morphological and physiological aspects of a novel acidotolerant and halotolerant microalga Coccomyxa onubensis sp. nov. (Chlorophyta, Trebouxiophyceae). J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 3269–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, F.; Forján, E.; Vázquez, M.; Montero, Z.; Bermejo, E.; Castaño, M.Á.; Toimil, A.; Chagüaceda, E.; García-Sevillano, M.Á.; Sánchez, M.; et al. Microalgae as a safe food source for animals: Nutritional characteristics of the acidophilic microalga Coccomyxa onubensis. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 60, 30472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, W. Ecophysiology of algae living in highly acidic environments. Hydrobiologia 2000, 433, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canelli, G.; Abiusi, F.; Vidal Garcia, A.; Canziani, S.; Mathys, A. Amino acid profile and protein bioaccessibility of two Galdieria sulphuraria strains cultivated autotrophically and mixotrophically in pilot-scale photobioreactors. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 84, 103287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.-L.; Montero, Z.; Cuaresma, M.; Ruiz-Domínguez, M.-C.; Mogedas, B.; Nores, I.G.; del Valle, M.; Vílchez, C. Outdoor Large-Scale Cultivation of the Acidophilic Microalga Coccomyxa onubensis in a Vertical Close Photobioreactor for Lutein Production. Processes 2020, 8, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tizzani, R.; Barberi, G.; Mohamadnia, S.; Angelidaki, I.; Facco, P.; Sforza, E. Design of Dynamic Experiments (DoDE) to optimize the lutein production by Coccomyxa onubensis in a novel high-cell density reactor. Algal Res. 2025, 89, 104062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirooka, S.; Tomita, R.; Fujiwara, T.; Ohnuma, M.; Kuroiwa, H.; Kuroiwa, T.; Miyagishima, S. Efficient open cultivation of cyanidialean red algae in acidified seawater. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaquero, I.; Mogedas, B.; Ruiz-Domínguez, M.C.; Vega, J.M.; Vílchez, C. Light-mediated lutein enrichment of an acid environment microalga. Algal Res. 2014, 6, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M.P.; Lundgren, D.G. Studies on the chemoautotrophic iron bacterium Ferrobacillus ferrooxidans. I. An improved medium and a harvesting procedure for securing high cell yields. J. Bacteriol. 1959, 77, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutner, S.H.; Provasoli, L.; Schatz, A.; Haskins, C.P. Some Approaches to the Study of the Role of Metals in the Metabolism of Microorganisms. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 1950, 94, 152–170. [Google Scholar]

- Robles, M.; Torronteras, R.; Ostojic, C.; Oria, C.; Cuaresma, M.; Garbayo, I.; Navarro, F.; Vílchez, C. Fe (III)-Mediated Antioxidant Response of the Acidotolerant Microalga Coccomyxa onubensis. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuler, M.L.; Kargi, F. Bioprocess Engineering: Basic Concepts, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: Singapore, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Robles, M.; Garbayo, I.; Wierzchos, J.; Vílchez, C.; Cuaresma, M. Effect of low-frequency ultrasound on disaggregation, growth and viability of an extremotolerant cyanobacterium. J. Appl. Phycol. 2022, 34, 2895–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostovová, I.; Byrtusová, D.; Rapta, M.; Babák, V.; Márová, I. The variability of carotenoid pigments and fatty acids produced by some yeasts within Sporidiobolales and Cystofilobasidiales. Chem. Pap. 2021, 75, 3353–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, A. Biological Principles of Mass Cultivation. In Handbook of Microalgal Culture; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 125–177. [Google Scholar]

- Norsker, N.-H.; Barbosa, M.J.; Vermuë, M.H.; Wijffels, R.H. Microalgal production—A close look at the economics. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishi, M.; Tanaka, K.; Akizuki, S.; Toda, T. Development of a gas-permeable bag photobioreactor for energy-efficient oxygen removal from algal culture. Algal Res. 2021, 60, 102543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbayo, I.; Torronteras, R.; Forján, E.; Cuaresma, M.; Bejarano, C.; Mogedas, B.; Ruiz-Dominguez, M.C.; Márquez, M.; Vaquero, I.; Fuentes-Cordero, J.L.; et al. Identification and physiological aspects of a novel carotenoid-enriched, metal-resistant microalga isolated from an acidic river in Huelva (Spain). J. Phycol. 2012, 48, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancucheo, I.; Johnson, D. Acidophilic algae isolated from mine-impacted environments and their roles in sustaining heterotrophic acidophiles. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schüler, L.M.; Schulze, P.S.C.; Pereira, H.; Barreira, L.; León, R.; Varela, J. Trends and strategies to enhance triacylglycerols and high-value compounds in microalgae. Algal Res. 2017, 25, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-España, J.; Falagán, C.; Ayala, D.; Wendt-Potthoff, K. Adaptation of Coccomyxa sp. to Extremely Low Light Conditions Causes Deep Chlorophyll and Oxygen Maxima in Acidic Pit Lakes. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquero, I.; Ruiz-Domínguez, M.C.; Mogedas, B.; Vílchez, C.; Vega, J.M. Production of Lutein-enriched Biomass by Growing Coccomyxa sp. (strain onubensis; Chlorophyta) under Spring Outdoor Conditions of Southwest Spain. J. Adv. Biotechnol. 2016, 6, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Fan, J.; Zhou, C.; Xu, C. Chloroplast lipid biosynthesis is fine-tuned to thylakoid membrane remodeling during light acclimation. Plant Physiol. 2020, 185, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wan, C.; Mehmood, M.A.; Chang, J.-S.; Bai, F.; Zhao, X. Manipulating environmental stresses and stress tolerance of microalgae for enhanced production of lipids and value-added products–A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 244, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházková, G.; Brányiková, I.; Zachleder, V.; Brányik, T. Effect of nutrient supply status on biomass composition of eukaryotic green microalgae. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 1359–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Hulatt, C.J.; Wijffels, R.H.; Kiron, V. Growth and LC-PUFA production of the cold-adapted microalga Koliella antarctica in photobioreactors. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 981–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Media | Aeration | |

|---|---|---|

| Raceway pond 1 | 2 × NPK | Air bubbled (2 L·min−1) |

| Raceway pond 2 | NPK | Air bubbled (2 L·min−1) |

| Raceway pond 3 | NPK | No aeration |

| Time (min) | Mobile Phase A (%) | Mobile Phase B (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 100 | 0 |

| 13.0 | 0 | 100 |

| 19.0 | 0 | 100 |

| 20.0 | 100 | 0 |

| 25.0 | 100 | 0 |

| Productivity | RW Pond 1 | RW Pond 2 | RW Pond 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass (g·L−1·d−1) | 0.031 ± 0.003 a | 0.025 ± 0.003 b | 0.018 ± 0.001 c |

| Chlorophyll (mg·g−1·d−1) | 0.107 ± 0.01 a | 0.139 ± 0.002 b | 0.053 ± 0.002 c |

| Carotenoid (mg·g−1·d−1) | 0.223 ± 0.03 a | 0.0952 ± 0.001 b | 0.080 ± 0.003 c |

| Fatty acid (mg·g−1·d−1) | 0.151 ± 0.004 a | 0.066 ± 0.002 b | 0.009 ± 0.001 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szotkowski, M.; Robles, M.; Fuentes, J.L.; Holub, J.; Cuaresma, M.; Márová, I.; Ruiz-Domínguez, M.C.; Torronteras, R.; Dávila, J.; Garbayo, I.; et al. Production of Lipids and Carotenoids in Coccomyxa onubensis Under Acidic Conditions in Raceway Ponds. Processes 2025, 13, 4041. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124041

Szotkowski M, Robles M, Fuentes JL, Holub J, Cuaresma M, Márová I, Ruiz-Domínguez MC, Torronteras R, Dávila J, Garbayo I, et al. Production of Lipids and Carotenoids in Coccomyxa onubensis Under Acidic Conditions in Raceway Ponds. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4041. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124041

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzotkowski, Martin, María Robles, Juan Luis Fuentes, Jiří Holub, María Cuaresma, Ivana Márová, Mari Carmen Ruiz-Domínguez, Rafael Torronteras, Javier Dávila, Inés Garbayo, and et al. 2025. "Production of Lipids and Carotenoids in Coccomyxa onubensis Under Acidic Conditions in Raceway Ponds" Processes 13, no. 12: 4041. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124041

APA StyleSzotkowski, M., Robles, M., Fuentes, J. L., Holub, J., Cuaresma, M., Márová, I., Ruiz-Domínguez, M. C., Torronteras, R., Dávila, J., Garbayo, I., & Vílchez, C. (2025). Production of Lipids and Carotenoids in Coccomyxa onubensis Under Acidic Conditions in Raceway Ponds. Processes, 13(12), 4041. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124041