Research on Integration Methods for Particle Position Updating in the Discrete Element Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Packing Test Design

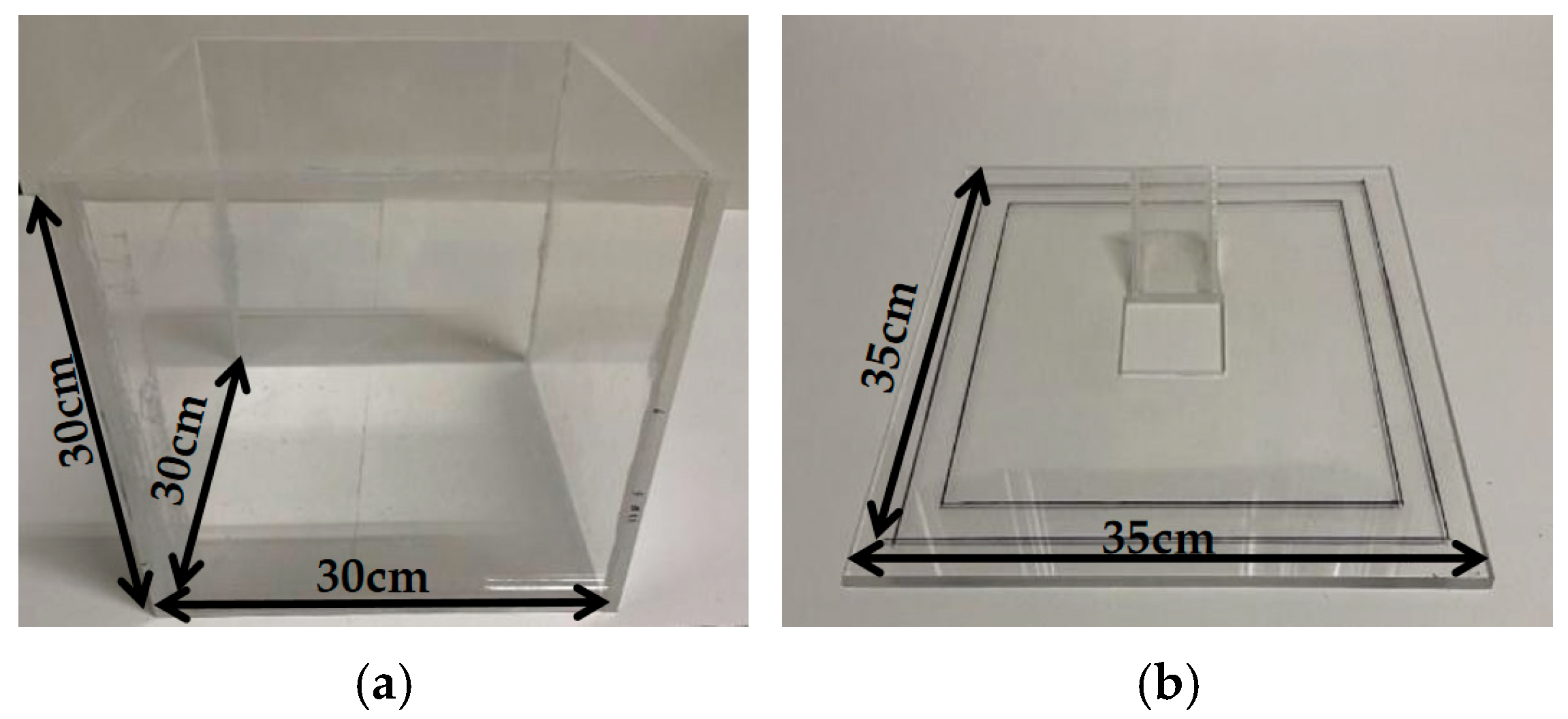

2.1. Test Objects

2.2. Test Equipment and Materials

3. Contact Determination and Contact Force Model

3.1. Phase I Contact Determination

3.2. Phase II Contact Determination

3.3. Element Contact Force Calculation

4. Comparison and Analysis of Simulation and Test Results

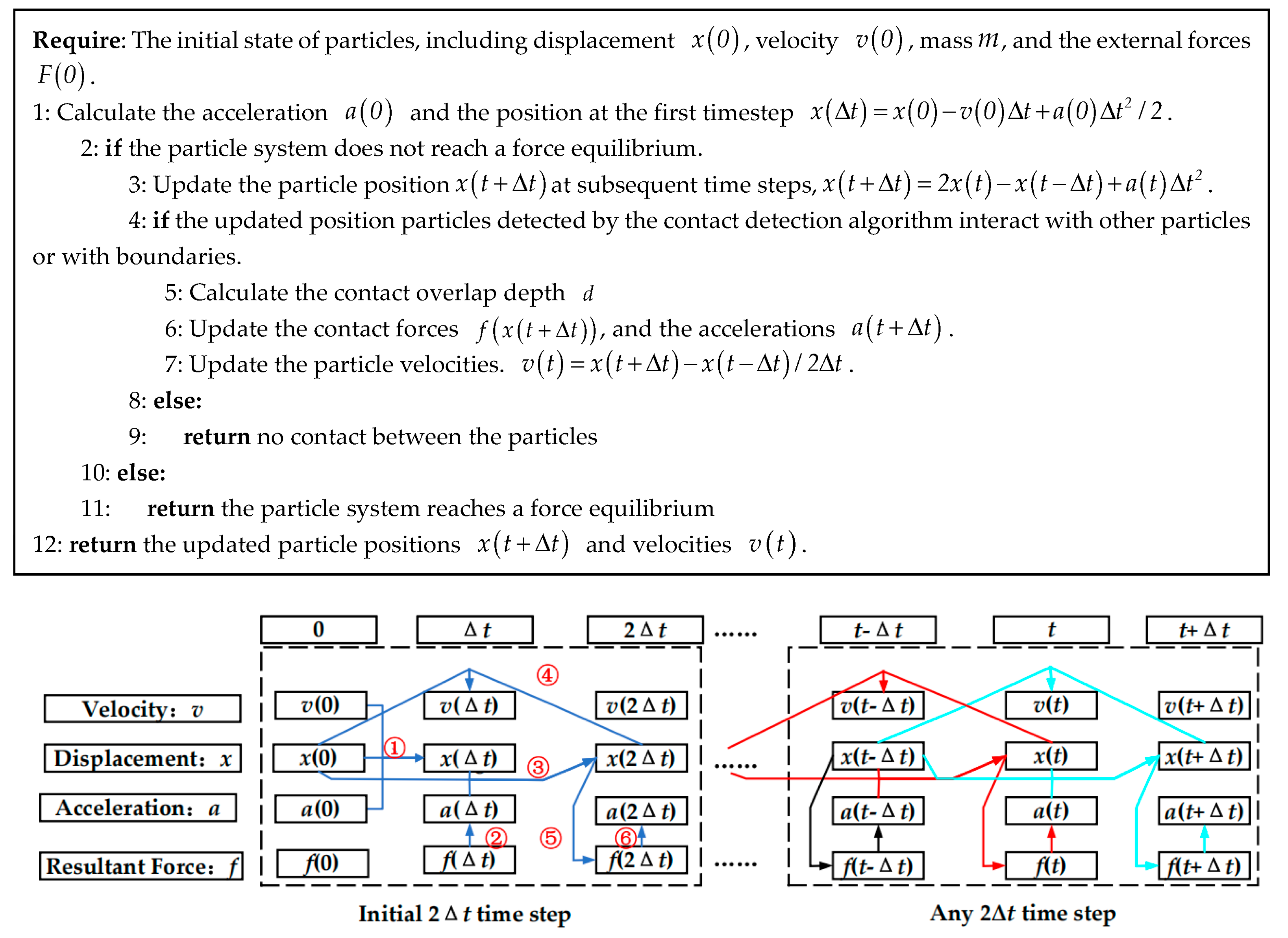

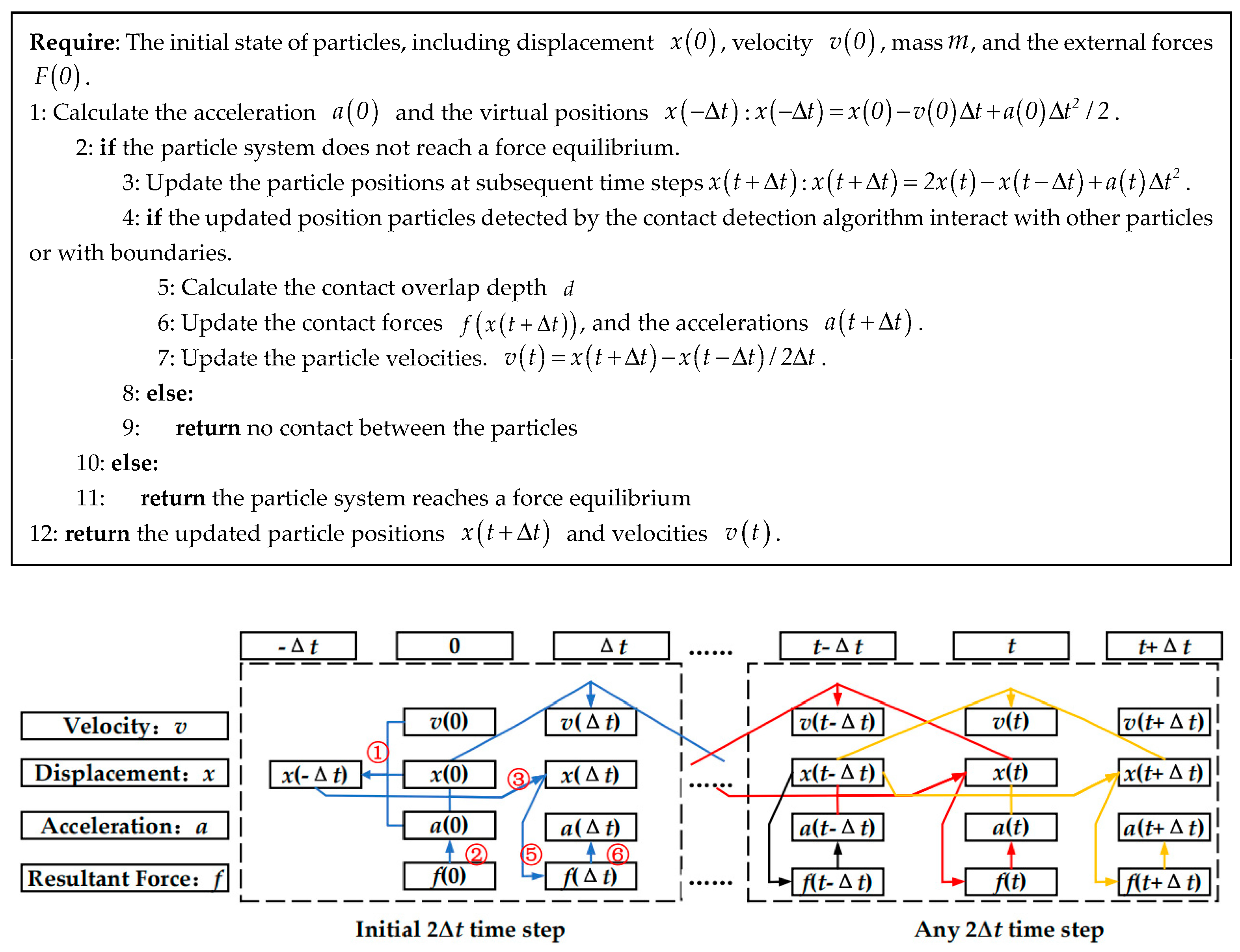

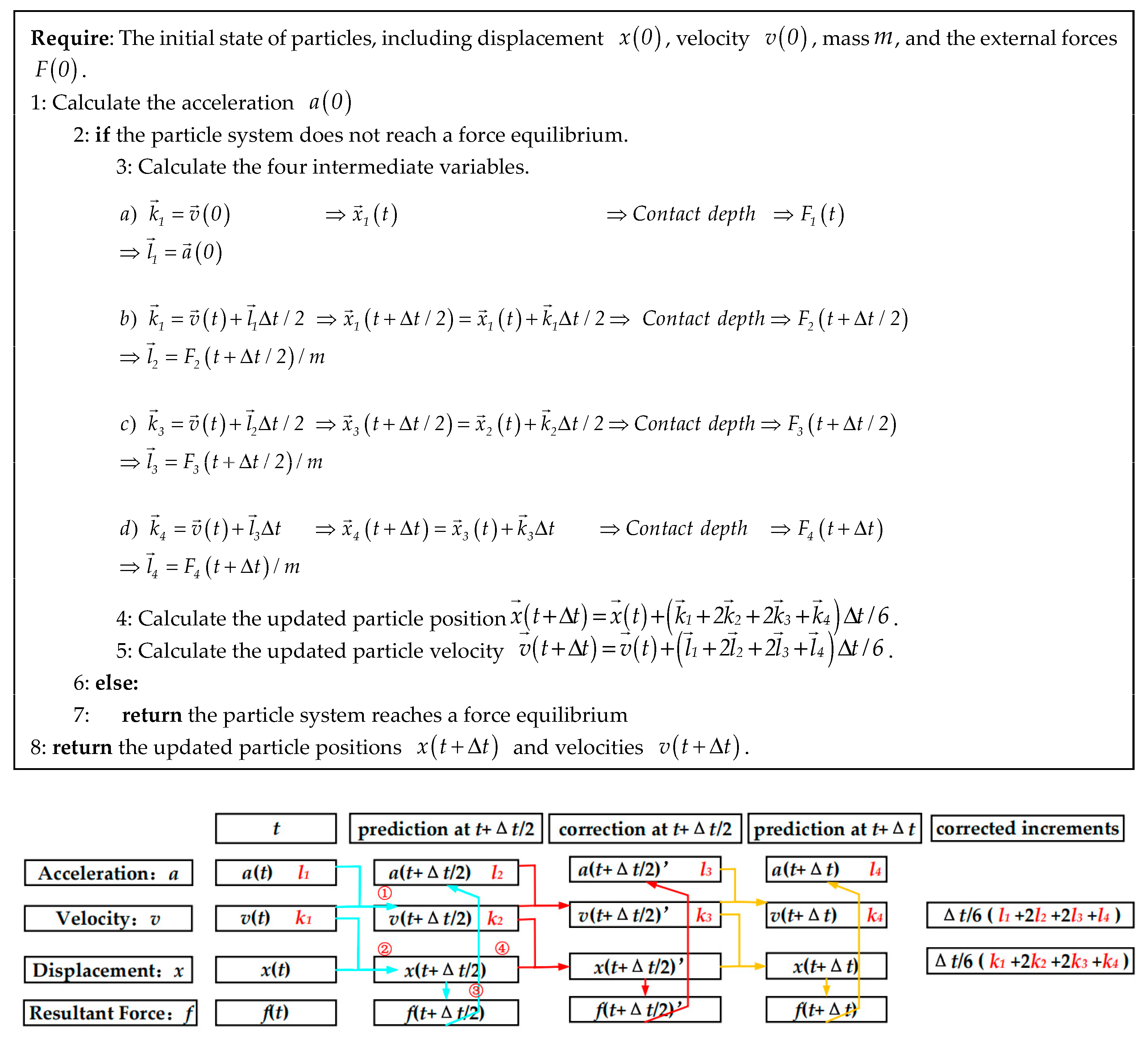

4.1. Code Implementation of Numerical Simulation

4.2. Numerical Simulation Parameter Setup

4.3. Comparison and Analysis of Simulation Results with Experimental Data

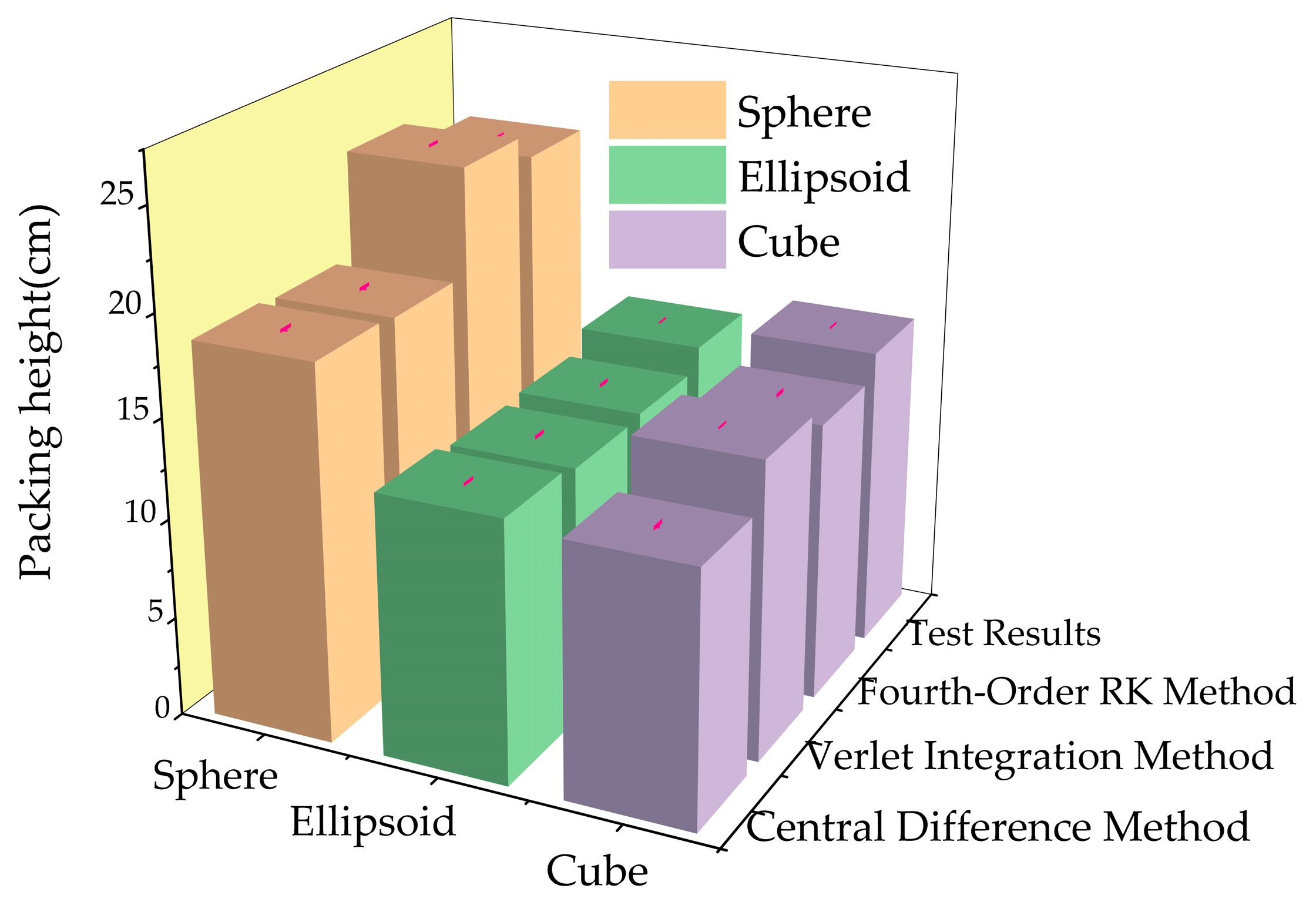

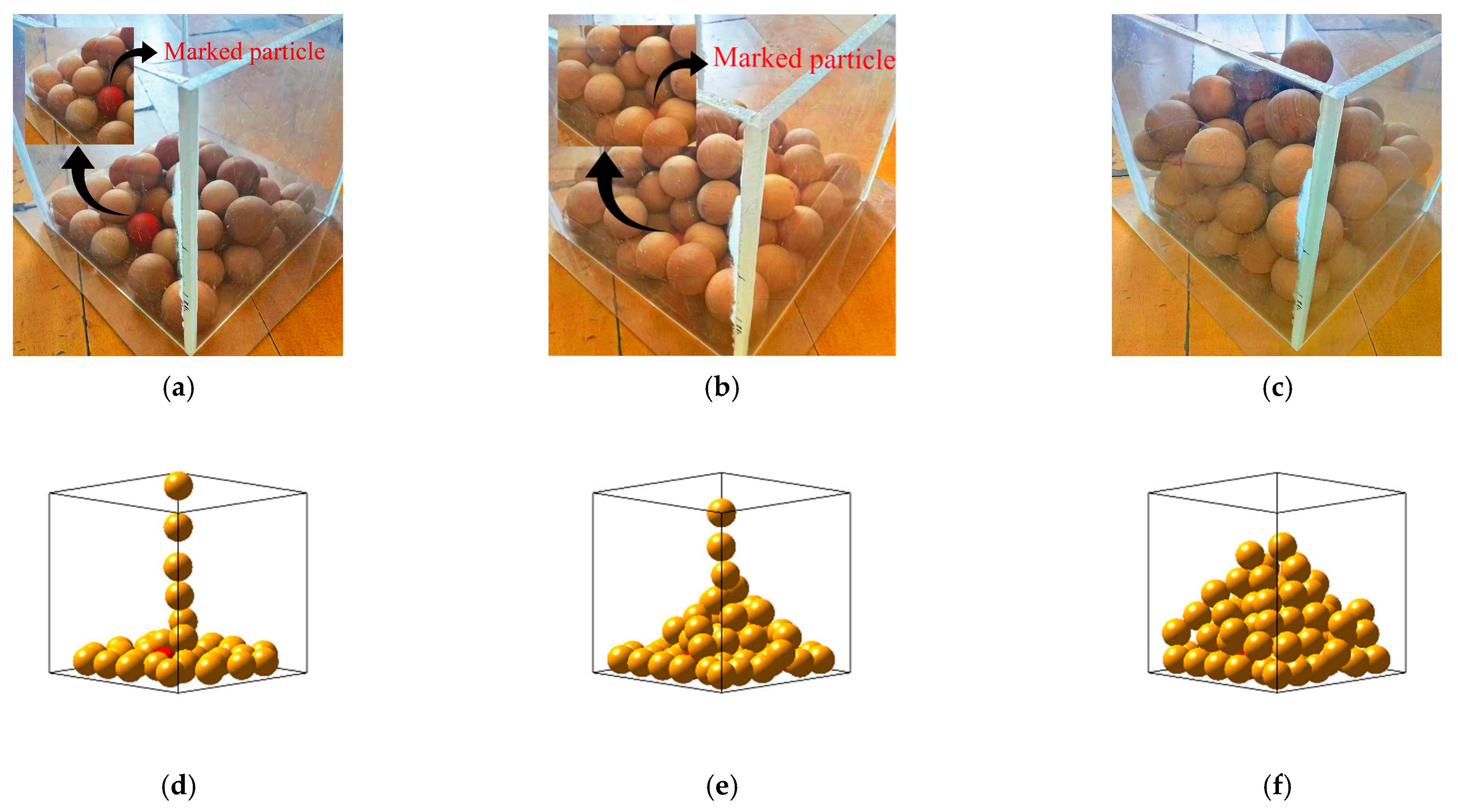

4.3.1. Comparative Analysis of Stacking Morphology

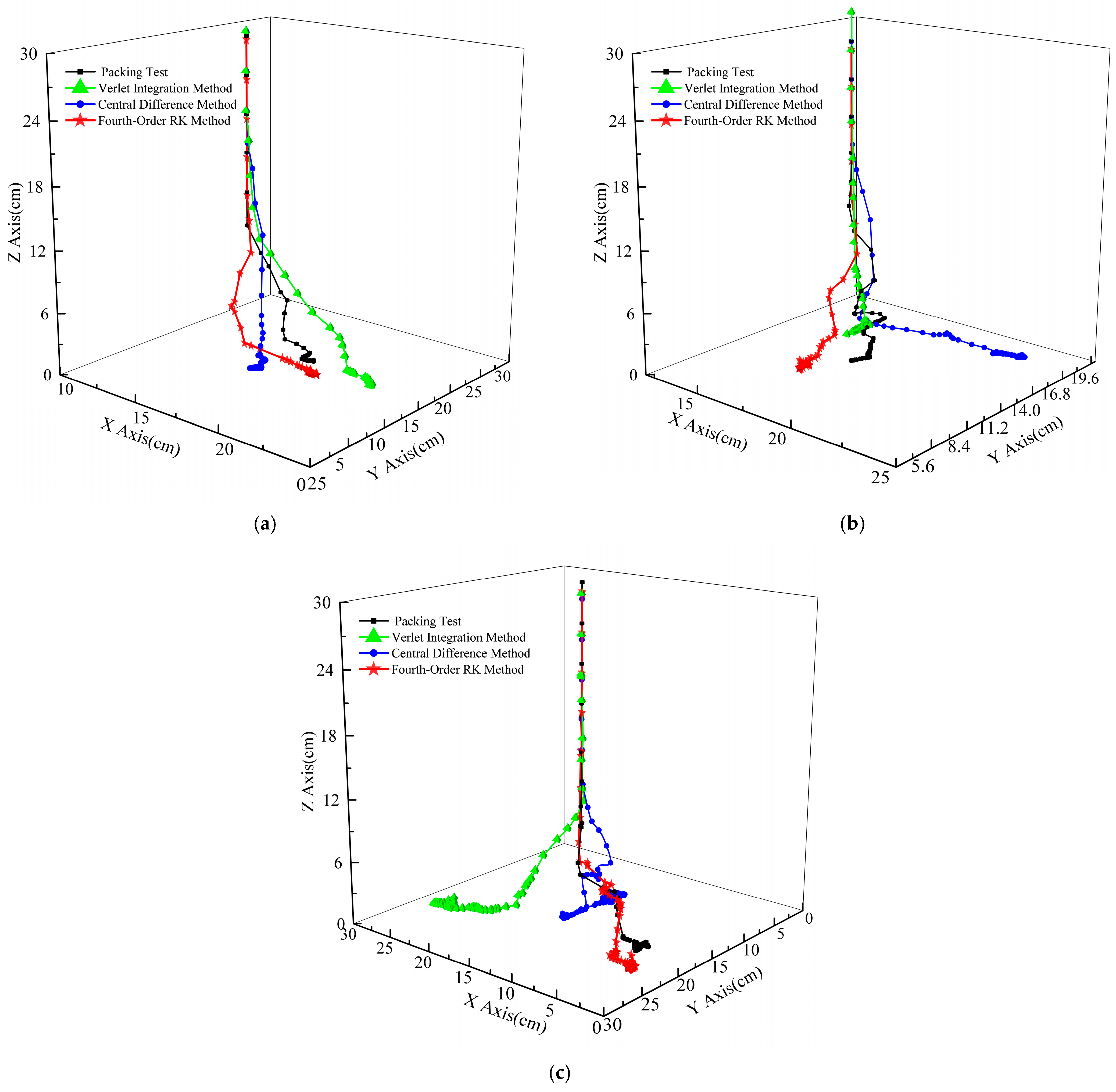

4.3.2. Comparison Analysis of the Packing Process

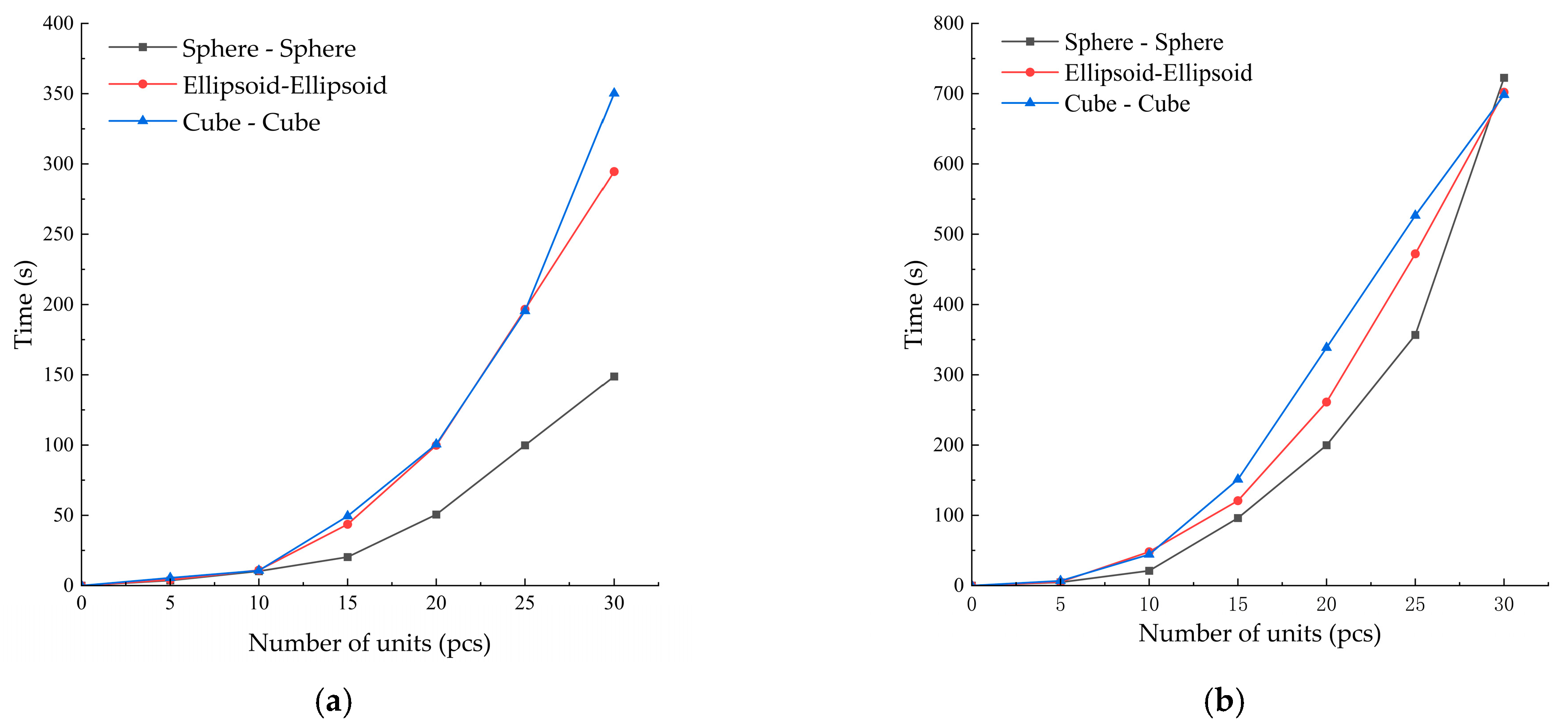

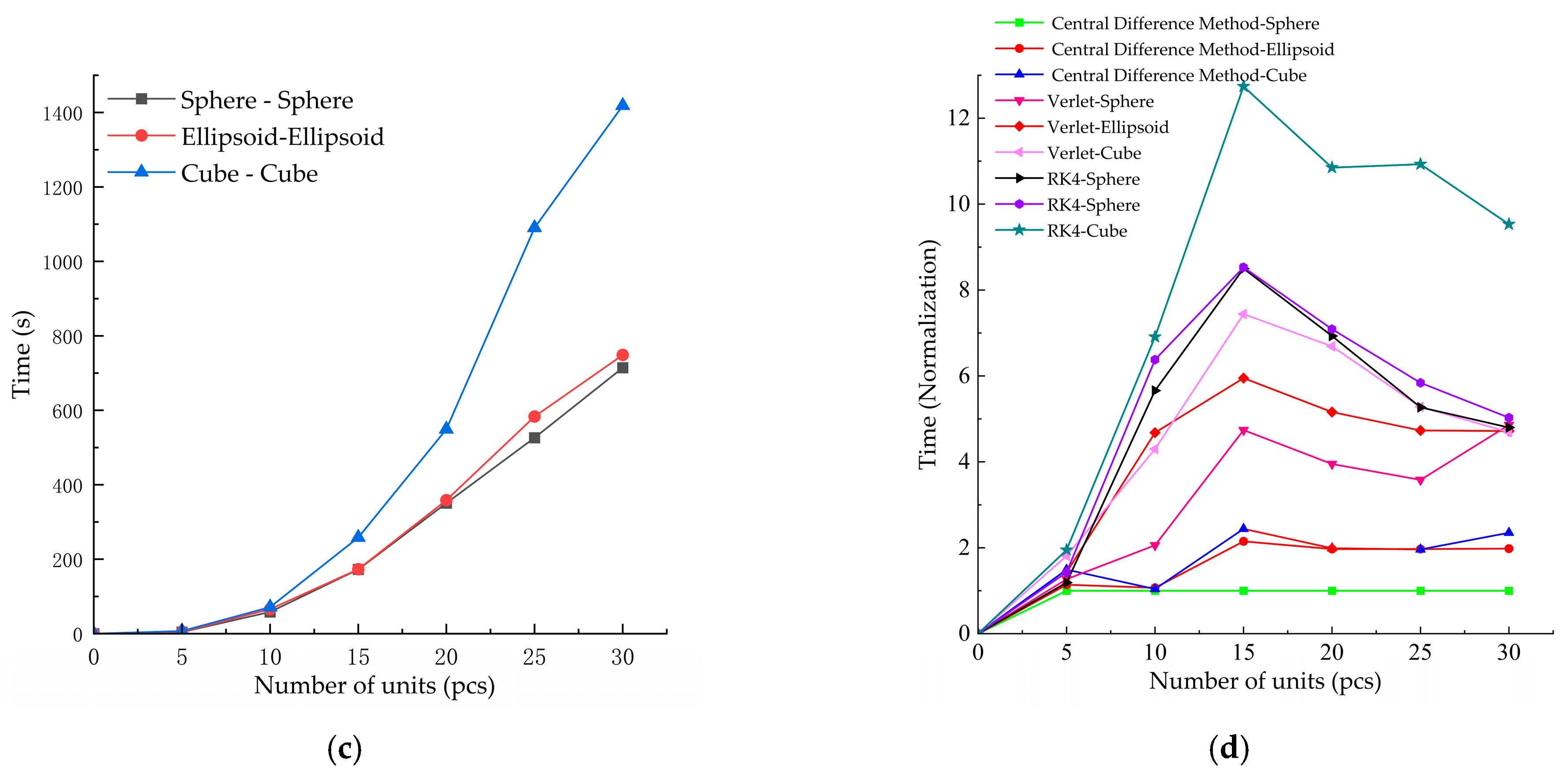

4.3.3. Comparison and Analysis of Computational Efficiency

5. Conclusions and Future Work

- (1)

- The fourth-order Runge–Kutta method exhibits the highest accuracy, with a packing height error of only 5.72% for spheres. However, it is the least efficient, requiring approximately 2–3 times the computational time of the central difference method. It is recommended for high-precision simulations and complex contact scenarios.

- (2)

- The central difference method achieves the lowest error for ellipsoidal particles (6.20%) and the highest computational efficiency, making it suitable for large-scale systems or simulations where efficiency is prioritized. However, it shows larger errors in cube packing (16.37%), and is therefore recommended for vertical displacement predictions in simple contact scenarios.

- (3)

- The Verlet method’s accuracy is comparatively lower for spheres and ellipsoids, and it is thus recommended for scenarios involving large instantaneous contact forces.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cundall, P.A.; Strack, O.D.L. Discussion: A discrete numerical model for granular assemblies. Géotechnique 1980, 30, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, A.; Roeplal, R.; Pang, Y.; Schott, D.L. DEM Modelling of Segregation in Granular Materials: A Review. KONA Powder Part. J. 2023, 41, 78–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, T.; Wang, Z. Review of numerical analysis methods for crushing behavior of particulate materials 1. Chin. J. Mech. 2024, 56, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Karlovšek, J. Calibration and uniqueness analysis of microparameters for DEM cohesive granular material. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2022, 32, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Deng, Q.; Wang, H. Instability behavior of loose granular material: A new perspective via DEM. Granul. Matter 2024, 26, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potyondy, D.O.; Cundall, P.A. A bonded-particle model for rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2004, 41, 1329–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerk, D.D.; Shire, T.; Gao, Z.; McBride, A.T.; Pearce, C.J.; Steinmann, P. A variational integrator for the Discrete Element Method. J. Comput. Phys. 2022, 462, 111253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poot, A.; Kerfriden, P.; Rocha, L.; Meer, F.V.D. A Bayesian approach to modeling finite element discretization error. Stat. Comput. 2024, 34, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Ren, H.; Fan, W.; Zhang, Z. A spacetime variational integration approach to the full discretization of flexible beams based on absolute nodal coordinate formulation. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 1175–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Jin, X.; Wang, X.; Pan, J.; Yang, P. Parallel Computing Method of FEM-DEM with Multiple-time Step Based on Overlapping Boundary. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2023, 54, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, Q.; Jin, X. A Multi-time-step Discrete Element Method for Bar Structures. Chi. J. Comput. Phys. 2022, 39, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Kim, S.; Noh, G. Learned Gaussian quadrature for enriched solid finite elements. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2023, 414, 116188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshraghi1, H.; Amani, E.; Saffar-Avval, M. Coarse-graining algorithms for the Eulerian-Lagrangian simulation of particle-laden flows. J. Comput. Phys. 2023, 493, 112461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T.; Indraratna, B.; Nguyen, T.T.; Rujikiatkamjorn, C. Interactive role of rolling friction and cohesion on the angle of repose through a microscale assessment. Int. J. Geomech. 2023, 23, 04022250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roessler, T.; Katterfeld, A. DEM parameter calibration of cohesive bulk materials using a simple angle of repose test. Particuology 2019, 45, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Thornton, C. A comparison of discrete element simulations and experiments for ‘sandpiles’ composed of spherical particles. Powder Technol. 2005, 160, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Guo, B.; Gao, Z.; Zheng, M.; Yang, H.; Li, D. Sand modeling and parameter calibration based on DEM. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2019, 40, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Khatoon, S.; Yogi, J.; Verma, S.K.; Anand, A. Experimental investigation of segregation in a rotating drum with non-spherical particles. Powder Technol. 2022, 411, 117918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, D.R.; Ottino, J.M.; Lueptow, R.M.; Umbanhowar, P.B. Improved Velocity-Verlet Algorithm for the Discrete Element Method. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2025, 310, 109524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, S. An Explicit Time Integration Method Based on the Verlet Scheme with Improved Characteristics in Numerical Dispersion. J. Eng. Mech. 2024, 150, 04024031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.Y.; Hu, Z.H. On the relation between the velocity- and position-Verlet integrators. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 226101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liao, F.; Ye, Z. On Numerical Integration and Conservation of Cell-Centered Finite Difference Method. J. Sci. Comput. 2024, 100, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.F.; Chen, H.B.; Yue, X.Q.; Long, G.Q. High-order fractional central difference method for multi-dimensional integral fractional Laplacian and its applications. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. 2025, 145, 108711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.B.; Zhang, Z.Y. Numerical Methods Based on Characteristic Centered Finite Difference Procedure for a Class of Nonlinear Evolution Equations. Chin. J. Comput. Phys. 2024, 24, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, D.; Lars, C.; Michael, S.L.; Gregor, J.G.; Manuel, T. Fourth-Order Paired-Explicit Runge-Kutta Methods. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.05470. [Google Scholar]

- Maneechay, P.; Khatbanjong, S.; Pochai, N.; Vongkok, A. Combination of the Fourth-Order Runge-Kutta and an Explicit Finite Difference Method for an Advection-Diffusion Equation. Eng. Lett. 2025, 33, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Krivovichev, G.V. Stability Optimization of Explicit Runge–Kutta Methods with Higher-Order Derivatives. Algorithms 2024, 17, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilber, H.M.; Hughes, T.J.R.; Taylor, R.L. Improved numerical dissipation for time integration algorithms in structural dynamics. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1977, 5, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairer, E.; Lubich, C.; Wanner, G. Geometric Numerical Integration: Structure Preserving Algorithms for Ordinary Differential Equations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 817–821. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio, R.; Giordano, G.; Paternoster, B. Numerical conservation issues for stochastic Hamiltonian problems. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 2425, p. 090007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H. Construction of higher order symplectic integrators. Phys. Lett. A 1990, 150, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Y.; Xu, W.J.; Zhou, Q. DEM contact model for spherical and polyhedral particles based on energy conservation. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 153, 105072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indraratna, B.; Lackenby, J.; Christie, D. Effect of confining pressure on the degradation of ballast under cyclic loading. Geotechnique 2005, 55, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundall, P.A. Formulation of a three-dimensional distinct element model—Part I. A scheme to detect and represent contacts in a system composed of many polyhedral blocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1988, 25, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezami, E.G.; Hashash, Y.M.A.; Zhao, D. A fast contact detection algorithm for 3-D discrete element method. Comput. Geotech. 2004, 31, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Ran, Y. A Fast Slicing Method for Colored Models Based on Colored Triangular Prism and OpenGL. Micromachines 2025, 16, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, F.; Kazei, V.; Li, W. Understanding 3D seismic data visualization with C++, OpenGL and GLSL. Comput. Geosci. 2024, 191, 105681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, S.; Yang, M.; Wu, H.; Li, J. GFNS: An OpenGL-based tool for shield tunneling simulation in 3D complex stratum. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 167, 106111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, C.; Bray, J.D. Selecting a suitable time step for discrete element simulations that use the central difference time integration scheme. Eng. Comput. 2004, 21, 278–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruggel-Emden, H.; Simsek, E.; Rickelt, S.; Wirtz, S.; Scherer, V. Review and extension of normal force models for the Discrete Element Method. Powder Technol. 2007, 171, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Serial Number | Name | Type | Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sphere 1 |  | Diameter: 4.8 cm |

| 2 | Sphere 2 |  | Diameter: 5.6 cm |

| 3 | Ellipsoid |  | Tri-axial Length: 4 cm, 4 cm, 5.6 cm |

| 4 | Cube 1 |  | Edge Length: 3.5 cm |

| 5 | Cube 2 |  | Edge Length: 4 cm |

| The Name of the Parameter | Size |

|---|---|

| Density (kg/m3) | 600 |

| Elastic modulus (GPa) | 0.03 |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.14 |

| Angle of internal friction (°) | 20 |

| (N·s/m) | 0.07 |

| (N·s) | 0.07 |

| Translational damping coefficient (N·s/m) | 50 |

| Rotational damping coefficient (N·s/m) | 80 |

| (s) | 1 × 10−6 |

| (N/m) | 1.25 × 107 |

| (N/m) | 1.25 × 106 |

| Specimen Shape | Central Difference Method | Verlet Integration Method | Fourth-Order Runge–Kutta Method | Test Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sphere | Height (cm) | 18.72 | 18.53 | 23.83 | 22.54 ± 0.5 |

| Error (%) | 17 | 17.8 | 5.7 | — | |

| RMSE | 3.46 | 3.63 | 1.17 | — | |

| Ellipsoid | Height (cm) | 13.07 | 12.74 | 12.91 | 13.94 ± 0.5 |

| Error (%) | 6.2 | 8.6 | 1.6 | — | |

| RMSE | 0.78 | 1.08 | 0.93 | — | |

| Cube | Height (cm) | 12.62 | 14.85 | 13.93 ± 0.3 | 15.09 ± 0.5 |

| Error (%) | 16.4 | 1.6 | 7.7 | — | |

| RMSE | 2.22 | 0.20 | 1.03 | — | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y. Research on Integration Methods for Particle Position Updating in the Discrete Element Method. Processes 2025, 13, 4024. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124024

Liu J, Zhang P, Wang Y. Research on Integration Methods for Particle Position Updating in the Discrete Element Method. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4024. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124024

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jun, Pengbo Zhang, and Yue Wang. 2025. "Research on Integration Methods for Particle Position Updating in the Discrete Element Method" Processes 13, no. 12: 4024. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124024

APA StyleLiu, J., Zhang, P., & Wang, Y. (2025). Research on Integration Methods for Particle Position Updating in the Discrete Element Method. Processes, 13(12), 4024. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124024