SpyCatcher-Multiplicity Tunes Nanoscaffold Hydrogels for Enhanced Catalysis of Regulated Enzymes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Plasmids

2.2. Plasmid Construction

2.3. Cell Culture and Lysate Preparation

2.4. Protein Purification

2.5. Validation of Isopeptide Bonds and Grayscale Analysis

2.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.7. Enzyme Immobilization Assay

2.8. Cell-Free Biosynthesis System (CFBS)

2.9. Pore Size Determination with BET

2.10. Rheology Measurements

2.11. Assay

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

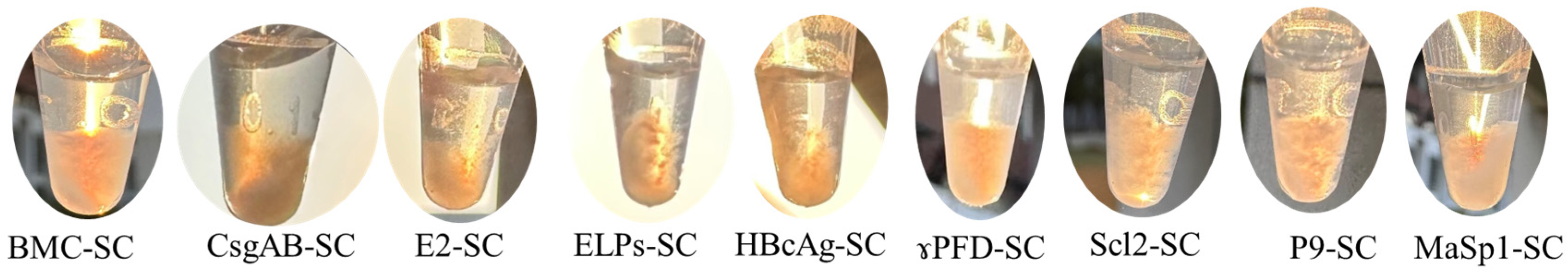

3.1. Design and In Vitro Characterization of Protein Nanoscaffolds Mediated by SpyCatcher

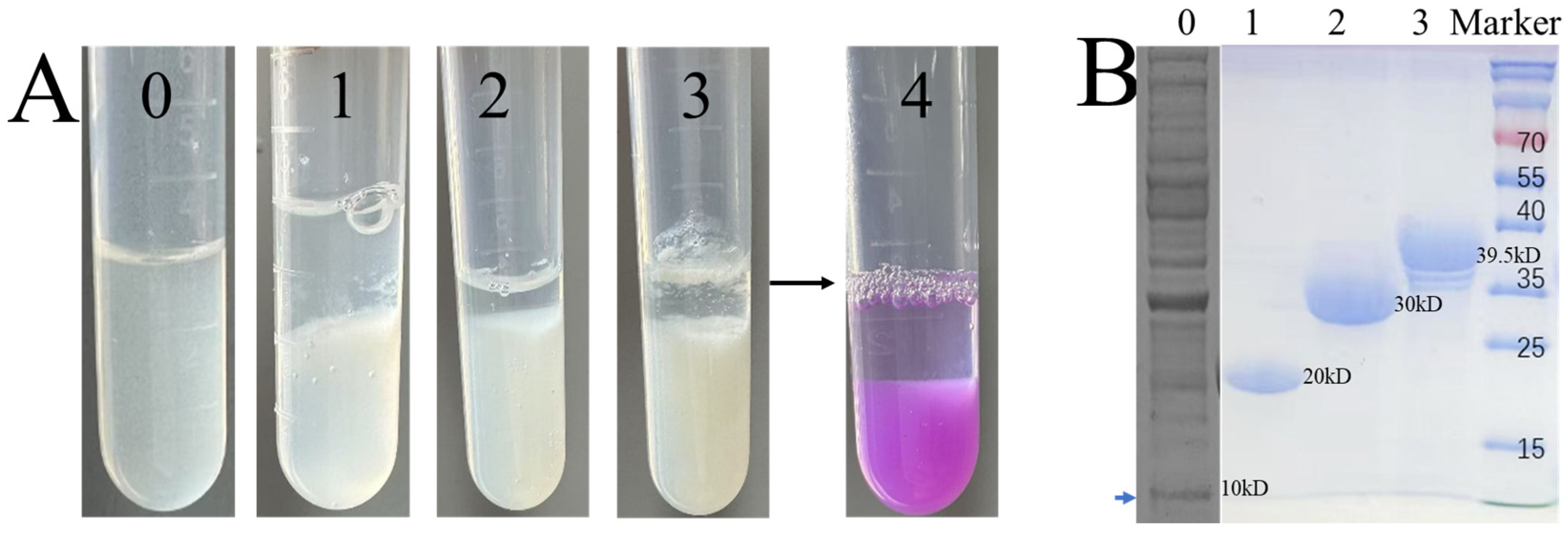

3.2. SpyCatcher Multivalency Enhances P9 Hydrogel Formation

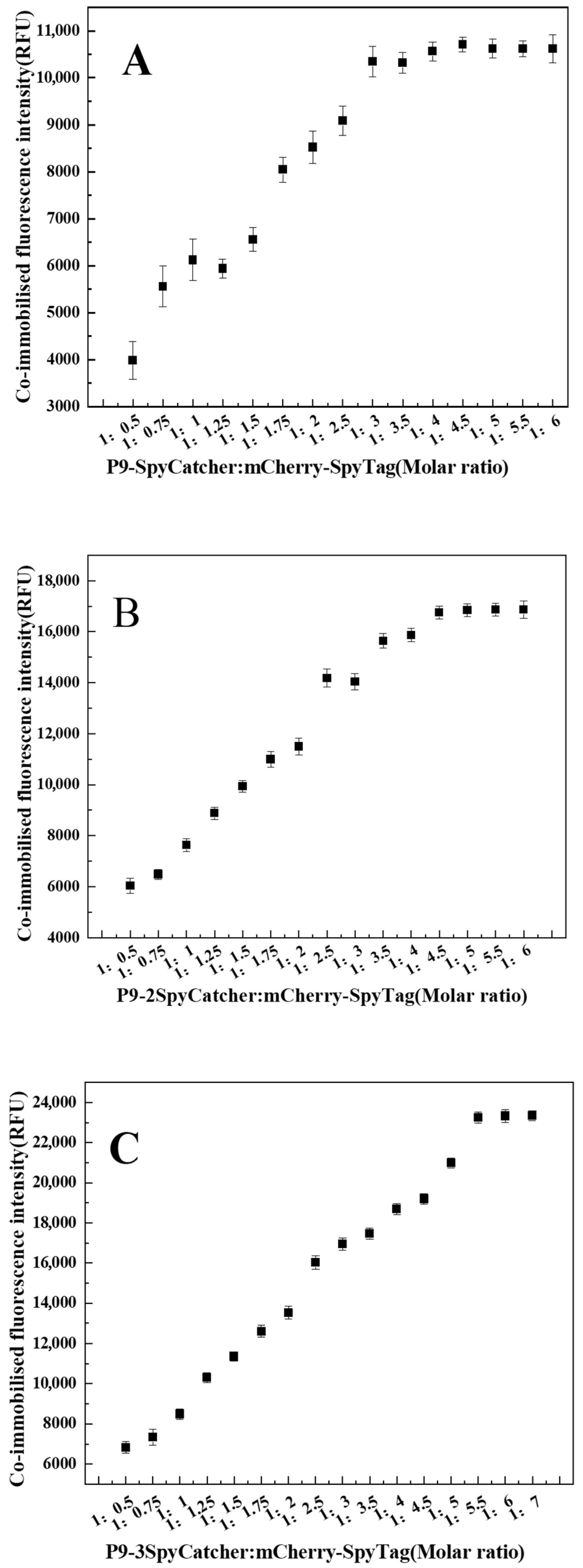

3.3. SpyCatcher-Dependent Enzyme Immobilization Capacity

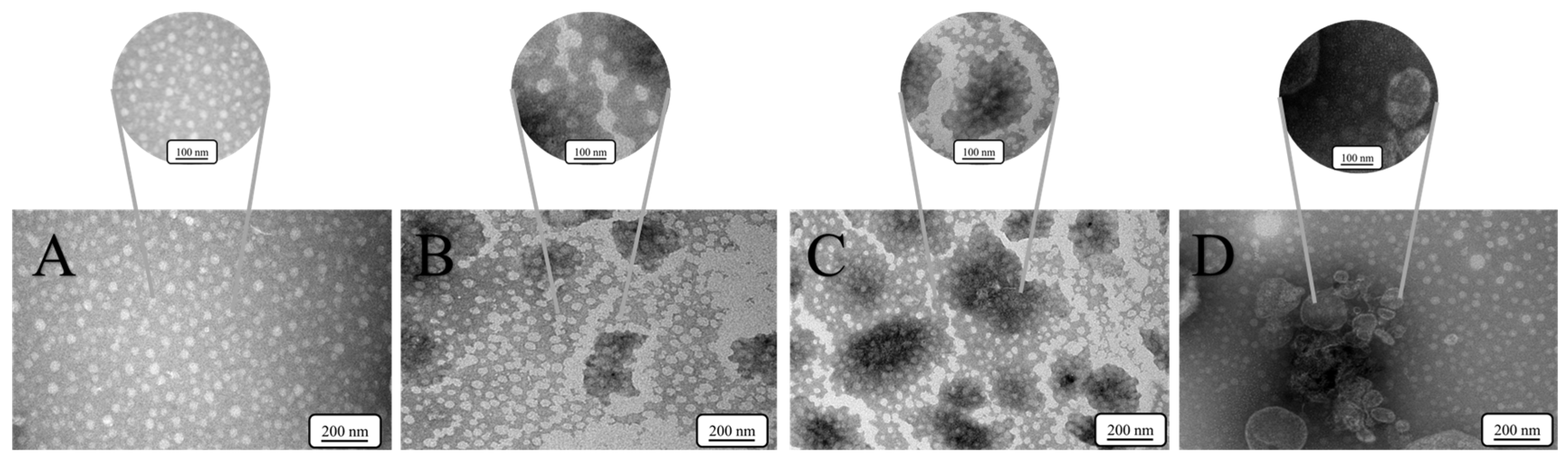

3.4. Nanostructural Evolution Mediated by SpyCatcher Valency

- P9-SpyCatcher: Linear chain-like aggregates via pairwise interactions (Figure 4B).

- P9-2SpyCatcher: Networked clusters exhibiting significantly increased crosslinking density, as measured by the total length of interconnected P9 monomers (approximately 68.4% increase) (Figure 4C).

- P9-3SpyCatcher: Dense microdomains exhibiting reduced interparticle spacing (Figure 4D).

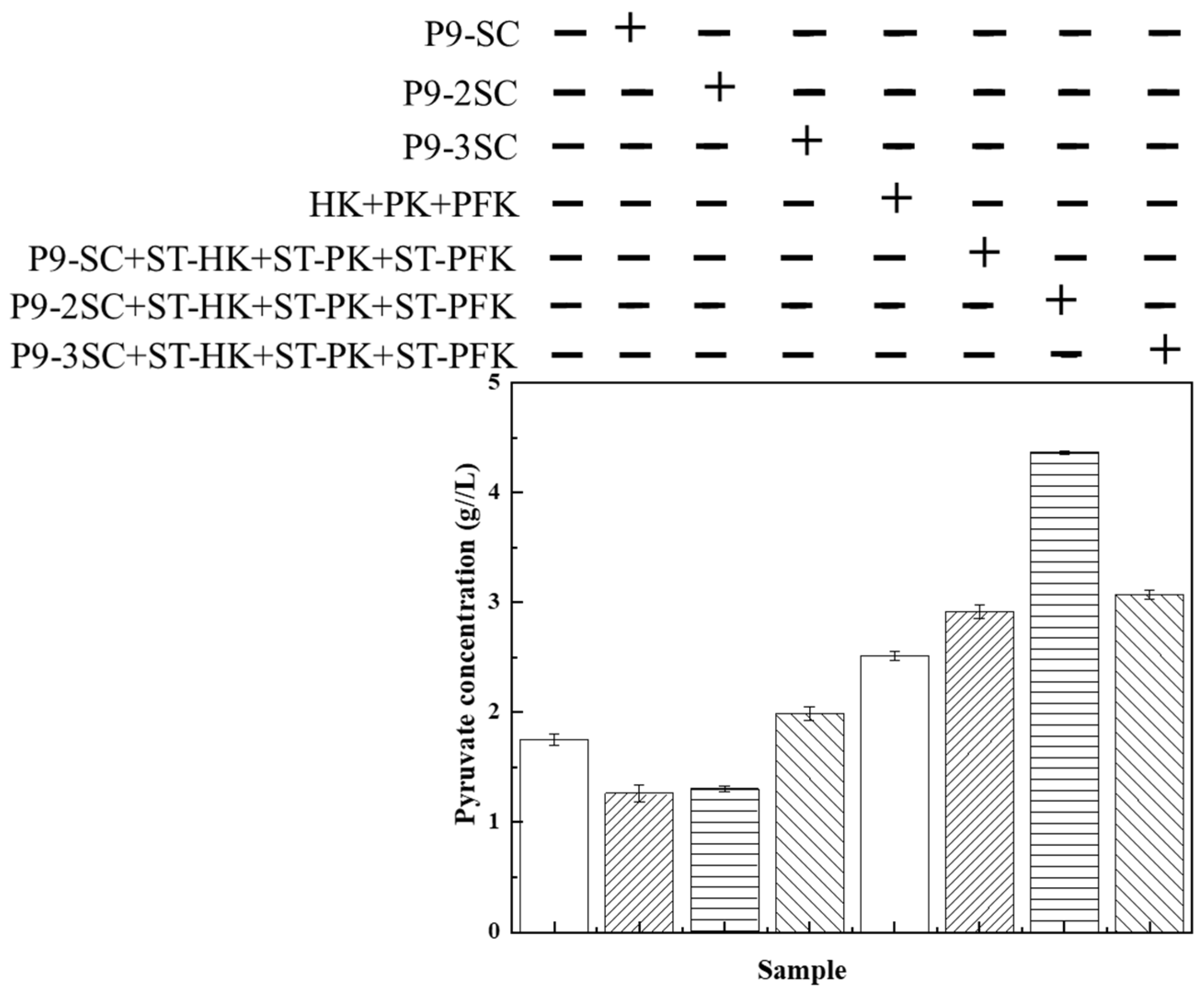

3.5. CFBS-Driven Rational Engineering for Pyruvate Production

3.6. Rheological Properties of SpyCatcher-Mediated Protein Hydrogels

3.7. Structural Characteristics of SpyCatcher-Mediated Protein Hydrogels

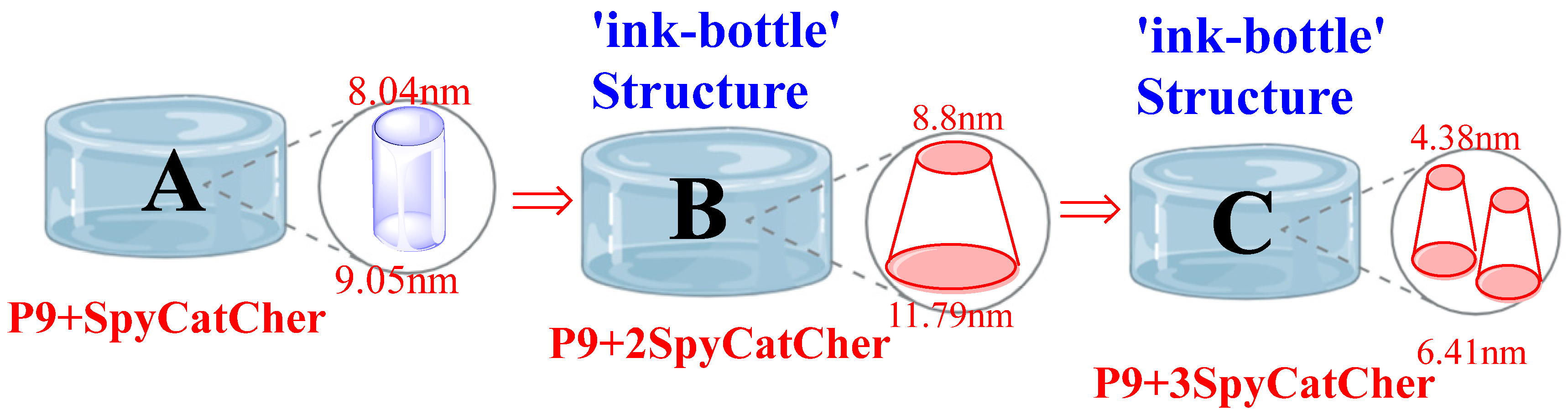

- P9-SpyCatcher: The adsorption (9.50 nm) and desorption (8.04 nm) pore diameters are similar (difference = 1.46 nm), indicating uniform pore channels. This uniformity allows enzyme molecules to fully enter and freely orient within the pores, enhancing catalytic performance.

- P9-2SpyCatcher: The significant difference between adsorption (11.8 nm) and desorption (8.81 nm) pore diameters (Δ = 2.99 nm) is characteristic of an “ink-bottle pore” structure (wide cavity + narrow pore neck). In the field of biomaterials, ‘ink-bottle type materials’ exhibit adsorption hysteresis due to pore blocking caused by the necessity to pass through narrow openings [29]. However, if pore blocking is absent in the ink-bottle geometry, its significance in other contexts warrants re-evaluation [30], such as in enzyme immobilization of P9-2SpyCatcher. The large cavity size (11.8 nm) may accommodate more enzyme molecules, potentially contributing to its greater efficacy in regulating enzyme activity compared to P9-SpyCatcher.

- P9-3SpyCatcher: The significantly higher BJH adsorption pore diameter (6.41 nm) relative to the BET value (3.31 nm) (ratio = 1.94) indicates a hierarchical micro-mesoporous structure. This structure combines abundant micropores (sensitive to BET analysis) with mesopores (BJH adsorption = 6.41 nm), rendering it suitable for small molecule adsorption/catalysis. However, the smaller pore dimensions make it prone to clogging following enzyme immobilization.

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gaspar-Morales, E.A.; Waterston, A.; Sadqi, M.; Diaz-Parga, P.; Smith, A.M.; Gopinath, A.; Andresen Eguiluz, R.C.; de Alba, E. Natural and engineered isoforms of the inflammasome adaptor ASC form noncovalent, pH-responsive hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 5563–5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Z.; Jeon, J.; Jiang, B.; Subramani, S.V.; Li, J.; Zhang, F. Protein-based hydrogels and their biomedical applications. Molecules 2023, 28, 4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordbar-Khiabani, A.; Gasik, M. Smart hydrogels for advanced drug delivery systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wu, A.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, H.; Zhu, P.; Mao, Y. Recent progress of nanomaterials-based composite hydrogel sensors for human–machine interactions. Discov. Nano 2025, 20, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.; Meyer, L.E.; Kara, S. Enzyme immobilization in hydrogels: A perfect liaison for efficient and sustainable biocatalysis. Eng. Life Sci. 2022, 22, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.S.; Khademhosseini, A. Advances in engineering hydrogels. Science 2017, 356, eaaf3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-López, C.; Alegre-Cebollada, J. Protein Hydrogels: The swiss army knife for enhanced mechanical and bioactive properties of biomaterials. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.P.; Yin, X.; Huang, M.Y.; Li, T.Y.; Long, X.F.; Li, Y.; Niu, F.X. A self-assembling γPFD-SpyCatcher hydrogel scaffold for the coimmobilization of SpyTag-enzymes to facilitate the catalysis of regulated enzymes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 19940–19947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glover, D.J.; Clark, D.S. Oligomeric assembly is required for chaperone activity of the filamentous γ-prefoldin. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 2985–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, F.X.; Yan, Z.B.; Huang, Y.B.; Liu, J.Z. Cell-free biosynthesis of chlorogenic acid using a mixture of chassis cell extracts and purified spy-cyclized enzymes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7938–7947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, J.C.; Wilson, S.C.; Bernstein, S.L.; Kerfeld, C.A. Biogenesis of a bacterial organelle: The carboxysome assembly pathway. Cell 2013, 155, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Dee, D.R.; Liu, B. Structural insight into Escherichia coli csgA amyloid fibril assembly. mBio 2024, 15, e00419–e00424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milne, J.L.S.; Wu, X.; Borgnia, M.J.; Lengyel, J.S.; Brooks, B.R.; Shi, D.; Perham, R.N.; Subramaniam, S. Molecular structure of a 9-MDa icosahedral pyruvate dehydrogenase subcomplex containing the E2 and E3 enzymes using cryoelectron microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 4364–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Cao, S.; Liu, M.; Kang, W.; Xia, J. Self-assembled multienzyme nanostructures on synthetic protein scaffolds. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 11343–11352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatema, K.; Snowden, J.S.; Watson, A.; Sherry, L.; Ranson, N.A.; Stonehouse, N.J.; Rowlands, D.J. A VLP vaccine platform comprising the core protein of hepatitis B virus with N-terminal antigen capture. Int. J. Biol. 2025, 305, 141152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Keene, D.R.; Bujnicki, J.M.; Höök, M.; Lukomski, S. Streptococcal scl1 and scl2 proteins form collagen-like triple helices. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 27312–27318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyytinen, O.L.; Starkova, D.; Poranen, M.M. Microbial production of lipid-protein vesicles using enveloped bacteriophage phi6. Microb. Cell Fact. 2019, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foong, C.P.; Higuchi-Takeuchi, M.; Malay, A.D.; Oktaviani, N.A.; Thagun, C.; Numata, K. A marine photosynthetic microbial cell factory as a platform for spider silk production. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berckman, E.A.; Chen, W. Self-assembling protein nanocages for modular enzyme assembly by orthogonal bioconjugation. Biotechnol. Prog. 2021, 37, e3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fierer, J.O.; Rapoport, T.A.; Howarth, M. Structural analysis and optimization of the covalent association between SpyCatcher and a Peptide Tag. J. Mol. Biol. 2014, 426, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Fang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Duan, L.; Liu, K.; Sun, F. Clickable, Thermally responsive hydrogels enabled by recombinant spider silk protein and spy chemistry for sustained neurotrophin delivery. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2413957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Desai, M.S.; Wang, T.; Lee, S.W. Elastin-based thermoresponsive shape-memory hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; Ahn, G.; Jung, R.; Muckom, R.J.; Glover, D.J.; Clark, D.S. Engineering bioorthogonal protein-polymer hybrid hydrogel as a functional protein immobilization platform. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 11467–11470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgriff-Hernandez, E.; Hahn, M.S.; Russell, B.; Wilems, T.; Munoz-Pinto, D.; Browning, M.B.; Rivera, J.; Höök, M. Bioactive hydrogels based on designer collagens. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 3969–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Fang, J.; Xue, B.; Fu, L.; Li, H. Engineering protein hydrogels using SpyCatcher-SpyTag chemistry. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 2812–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westermeier, R. Electrophoresis in Practice: A Guide to Methods and Applications of DNA and Protein Separations; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Y.; Jung, H.; Lim, D. Bacteriophage membrane protein P9 as a fusion partner for the efficient expression of membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 2015, 108, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Wang, W.; Guo, T.; Long, X.; Niu, F. Cell-free Escherichia coli synthesis system based on crude cell extracts: Acquisition of crude extracts and energy regeneration. Processes 2022, 10, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, E.; Chmiel, G.; Patrykiejew, A.; Sokołtowski, S. Pore closure effect on adsorption hysteresis in slit-like pores. Phys. Lett. A 1994, 189, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkisov, L.; Monson, P.A. Modeling of adsorption and desorption in pores of simple geometry using molecular dynamics. Langmuir 2001, 17, 7600–7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

) No scaffolds; (

) No scaffolds; ( ) P9-SC scaffold; (

) P9-SC scaffold; ( ) P9-2SC scaffold; (

) P9-2SC scaffold; ( ) P9-3SC scaffold.

) P9-3SC scaffold.

) No scaffolds; (

) No scaffolds; ( ) P9-SC scaffold; (

) P9-SC scaffold; ( ) P9-2SC scaffold; (

) P9-2SC scaffold; ( ) P9-3SC scaffold.

) P9-3SC scaffold.

| Name | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | F- ompT gal dcm lon hsdSB (rB-mB-) λ (DE3 lacI lacUV5-T7 gene 1 ind1 sam7 nin5) | Invitrogen (Waltham, MA, USA) |

| pET32a | Col El ori, lacl, T7 promoter, Ampr | Novagen (Vadodara, India) |

| pET32a-BMC | Fusion protein of BMC from Cyanophyceae to generate: BMC, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-BMC-SpyCatcher | Fusion protein of BMC from Cyanophyceae to a SpyCatcher domain via a (GSG)2 linker to generate: BMC-(GSG)2-SpyCatcher, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-CsgAB | Fusion protein of CsgAB from E. coli to generate: BMC, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-CsgAB-SpyCatcher | Fusion protein of CsgAB from E. coli to a SpyCatcher domain via a (GSG)2 linker to generate: CsgAB-(GSG)2-SpyCatcher, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-E2 | Fusion protein of E2 from Bacillus stearothermophilus (B. stearothermophilus) to generate: E2, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-E2-SpyCatcher | Fusion protein of E2 (B. stearothermophilus) to a SpyCatcher domain via a (GSG)2 linker to generate: E2-(GSG)2-SpyCatcher, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-ELPs | Fusion protein of ELPs from Procambarus clarkii (P. clarkii) to generate: ELPs, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-ELPs-SpyCatcher | Fusion protein of ELPs (P. clarkii) to a SpyCatcher domain via a (GSG)2 linker to generate: ELPs-(GSG)2-SpyCatcher, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-HBcAg | Fusion protein of HBcAg (virus-like particles hepatitis B) to generate: HBcAg, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-HBcAg-SpyCatcher | Fusion protein of HBcAg (virus-like particles hepatitis B) to a SpyCatcher domain via a (GSG)2 linker to generate: HBcAg-(GSG)2-SpyCatcher, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-γPFD | Fusion protein of γPFD from Methanococcus jannaschii (M. jannaschii) to generate: γPFD, T7 promoter, Ampr | [8] |

| pET32a-γPFD-SpyCatcher | Fusion protein of γPFD (M. jannaschii) to a SpyCatcher domain via a (GSG)2 linker to generate: γPFD-(GSG)2-SpyCatcher, T7 promoter, Ampr | [8] |

| pET32a-Scl2 | Fusion protein of Scl2 from Streptococcus to generate: Scl2, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-Scl2-SpyCatcher | Fusion protein of Scl2 from Streptococcus to a SpyCatcher domain via a (GSG)2 linker to generate: Scl2-(GSG)2-SpyCatcher, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-MaSp1 | Fusion protein of MaSp1 from Rhodovulum sulfidophilum (R. sulfidophilum) to generate: MaSp1, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-MaSp1-SpyCatcher | Fusion protein of MaSp1 (R. sulfidophilum) to a SpyCatcher domain via a (GSG)2 linker to generate: MaSp1-(GSG)2-SpyCatcher, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-P9 | Fusion protein of P9 from Pseudomonas phage to generate: P9, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-P9-SpyCatcher | Fusion protein of P9 from Pseudomonas phage to a SpyCatcher domain via a (GSG)2 linker to generate: P9-(GSG)2-SpyCatcher, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-P9-2SpyCatcher | Fusion protein of P9 from Pseudomonas phage with two SpyCatcher domains via (GSG)2 linker to generate: P9-(GSG)2-SpyCatcher-(GSG)2-SpyCatcher, T7 promoter, Ampr | This study |

| pET32a-P9-3SpyCatcher | Fusion protein of P9 from Pseudomonas phage with three SpyCatcher domains via (GSG)2 linker to generate: P9-(GSG)2-SpyCatcher-(GSG)2-SpyCatcher-(GSG)2-SpyCatcher, Ampr | This study |

| pZACBP | Constitute expression vector, p15A ori, P37 promoter, Cmr | [10] |

| pZAC-mCherry-SpyTag | Fusion protein of mCherry (Discosoma sp.) to a SpyTag domain via a (GSG)2 linker to generate: mCherry-(GSG)2-SpyTag-His, P37 promoter, Cmr | [8] |

| pZAC-PK-SpyTag | Fusion protein of pyruvate kinase (E. coli str. K-12 substr. MG1655) to a SpyTag domain via a (GSG)2 linker to generate: PK-(GSG)2-SpyTag-His, P37 promoter, Cmr | [8] |

| pZAC-HK-SpyTag | Fusion protein of hexokinase (E. coli str. K-12 substr. MG1655) to a SpyTag domain via a (GSG)2 linker to generate: HK-(GSG)2-SpyTag-His, P37 promoter, Cmr | [8] |

| pZAC-PFK-SpyTag | Fusion protein of 6-phosphofructokinase (E. coli str. K-12 substr. MG1655) to a SpyTag domain via a (GSG)2 linker to generate: PFK-(GSG)2-SpyTag, P37 promoter, Cmr | [8] |

| Protein | NCBI Reference Sequence | Description | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMC | WP_010872077.1 | Bacterial microcompartment protein demonstrating structural mimicry of icosahedral viral capsids in Cyanophyceae | [11] |

| CsgAB | WP_119912935.1 | Self-assembling amyloid fibril protein (E. coli) | [12] |

| E2 | 1B5S_A | Thermostable nano-cage protein from B. stearothermophilus pyruvate dehydrogenase complex | [19] |

| ELPs | UWL85471.1 | Elastin-mimetic polypeptide derived from P. clarkii | [14] |

| HBcAg | UXP87744.1 | Icosahedral VLP-forming hepatitis B core antigen | [15] |

| γPFD | WP_015732617.1 | Linear oligomeric architecture from M. jannaschii | [9] |

| Scl2 | WP_165363174.1 | Streptococcus-derived collagen-like domain protein | [16] |

| P9 | NP_620342.1 | Phage-encoded membrane protein forming spherical vesicles in Pseudomonas | [17] |

| MaSp1 | AAS67615.1 | Bioengineered dragline silk protein from R. sulfidophilum | [18] |

| Sample | P9-SpyCatcher | P9-2SpyCatcher | P9-3SpyCatcher | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Character | ||||

| Structural Strength (G’) | High (~11 Pa) | Moderate (~1.42 Pa) | Low (~0.32 Pa) | |

| Viscous/Elastic Ratio (tan δ) | Low (~0.36) | Moderate (~0.38) | High (~0.38–0.48) | |

| Zero-shear Viscosity (η0) | High | Moderate | Low | |

| Structural Stability | Very Stable | Stable | Relatively Stable | |

| Yield Stress | High | Moderate | Low | |

| Shear-thinning Behavior | Observed | Observed | Observed | |

| Parameter | P9-SpyCatcher | P9-2SpyCatcher | P9-3SpyCatcher |

|---|---|---|---|

| BET Average Pore Width (4V/A a)/nm | 7.32 ± 0.13 nm | 12.14 ± 0.11 nm | 3.31 ± 0.12 nm |

| BJH Avg. Pore Diameter (4V/A a, Ads b)/nm | 9.50 ± 0.13 nm | 11.79 ± 0.11 nm | 6.41 ± 0.12 nm |

| BJH Avg. Pore Diameter (4V/A a, Des c)/nm | 8.04 ± 0.13 nm | 8.80 ± 0.11 nm | 4.38 ± 0.12 nm |

| BJH Ads-Des Difference/nm | 1.46 nm | 2.99 nm | 2.03 nm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yin, X.; Liao, B.; Li, H.; Huang, M.-Y.; Niu, F.-X. SpyCatcher-Multiplicity Tunes Nanoscaffold Hydrogels for Enhanced Catalysis of Regulated Enzymes. Processes 2025, 13, 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124009

Yin X, Liao B, Li H, Huang M-Y, Niu F-X. SpyCatcher-Multiplicity Tunes Nanoscaffold Hydrogels for Enhanced Catalysis of Regulated Enzymes. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124009

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Xue, Bei Liao, Hui Li, Ming-Yue Huang, and Fu-Xing Niu. 2025. "SpyCatcher-Multiplicity Tunes Nanoscaffold Hydrogels for Enhanced Catalysis of Regulated Enzymes" Processes 13, no. 12: 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124009

APA StyleYin, X., Liao, B., Li, H., Huang, M.-Y., & Niu, F.-X. (2025). SpyCatcher-Multiplicity Tunes Nanoscaffold Hydrogels for Enhanced Catalysis of Regulated Enzymes. Processes, 13(12), 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124009