Prescribed Performance Output Feedback Control of the Independent Metering Electro-Hydraulic System

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The K-filter theory is innovatively applied to the load port of the IMS, which realizes the accurate estimation of the unmeasurable state quantity in the system, provides the necessary state information for the subsequent control, and overcomes the dependence of the traditional full state feedback on the sensor.

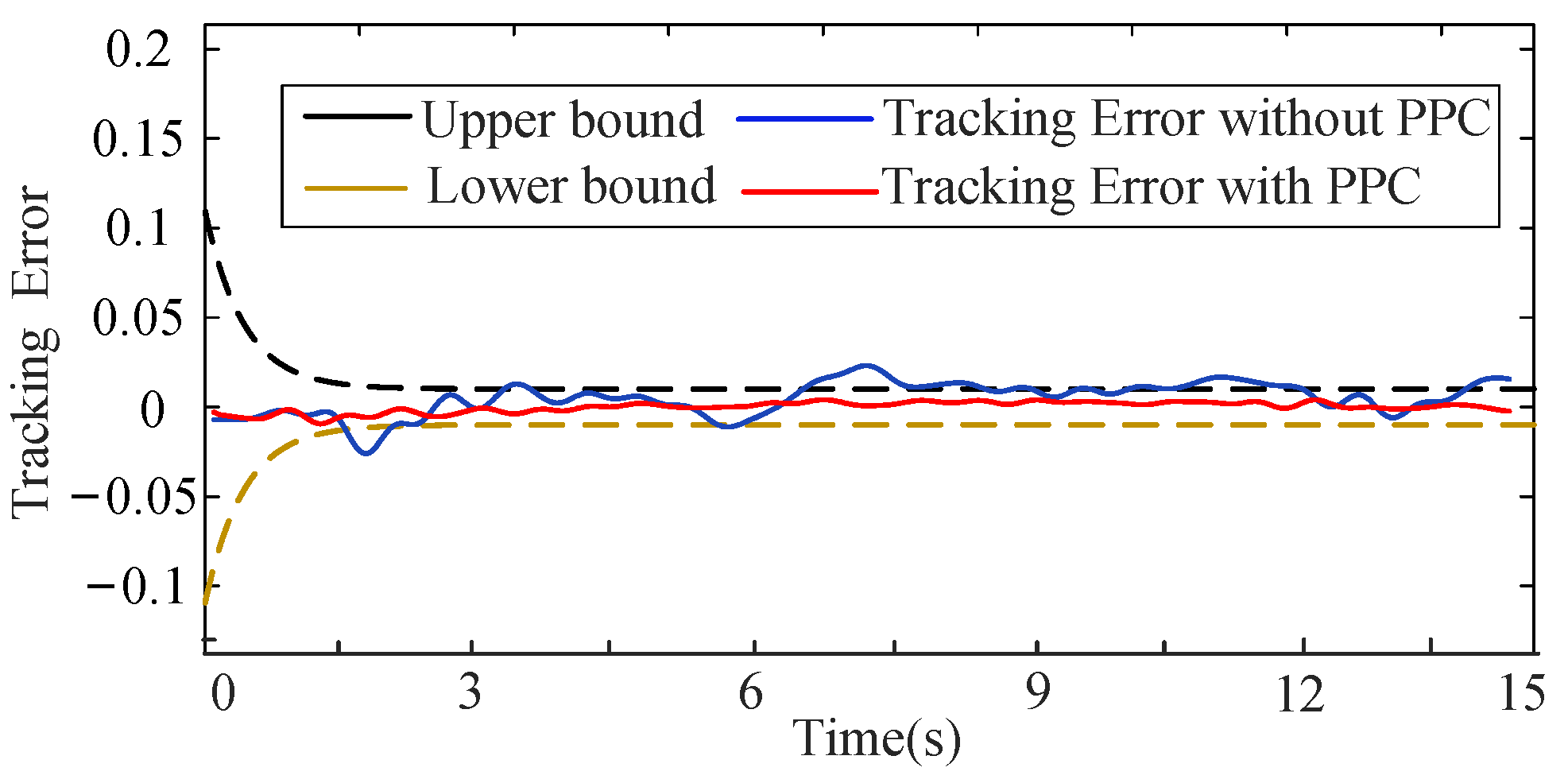

- The FLS is used to adaptively compensate for the unmodeled dynamics and external disturbances of the system, and the PPC is introduced to ensure that all state errors are strictly constrained within the preset performance function boundary within the set time, which effectively improves the control accuracy and robustness of the system.

- The DSC method is used to simplify the backstepping design process and alleviate the ‘computational explosion’ problem. In addition, the oil return pressure controller is specially designed to actively maintain the oil return back pressure at a low level, which reduces the energy loss on the oil return path of the system, thus improving the energy utilization efficiency of the system as a whole.

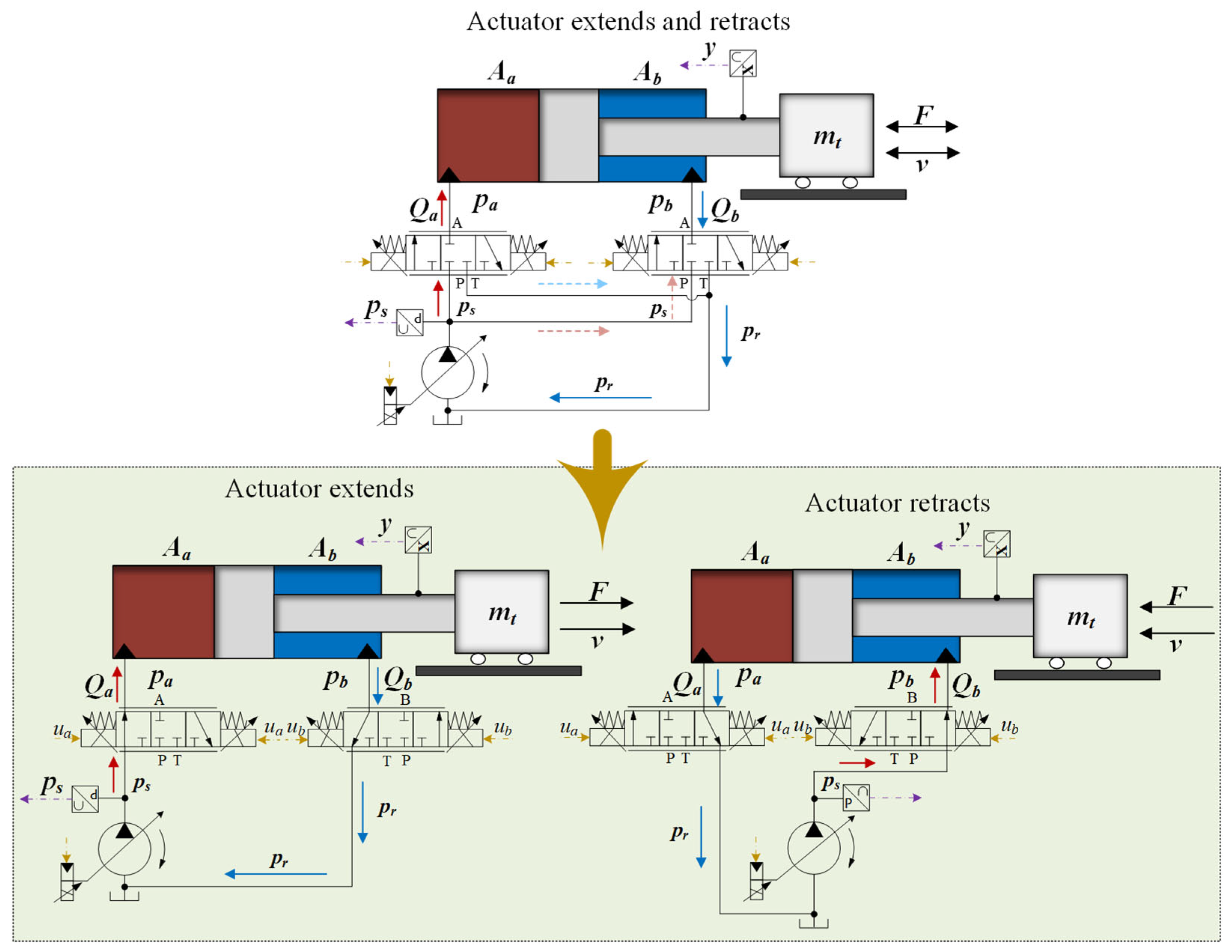

2. System Model Description and Preliminary Explanation

2.1. Kinetic Model of Hydraulic Systems

2.2. A Survey of Fuzzy Logic Systems

2.3. Prescribed Performance Control

3. Extended State Observer

4. Controller Design and Stability Analysis

4.1. Adaptive Output Feedback Predetermined Performance Control Design

4.2. Design of Oil Return Pressure Controller

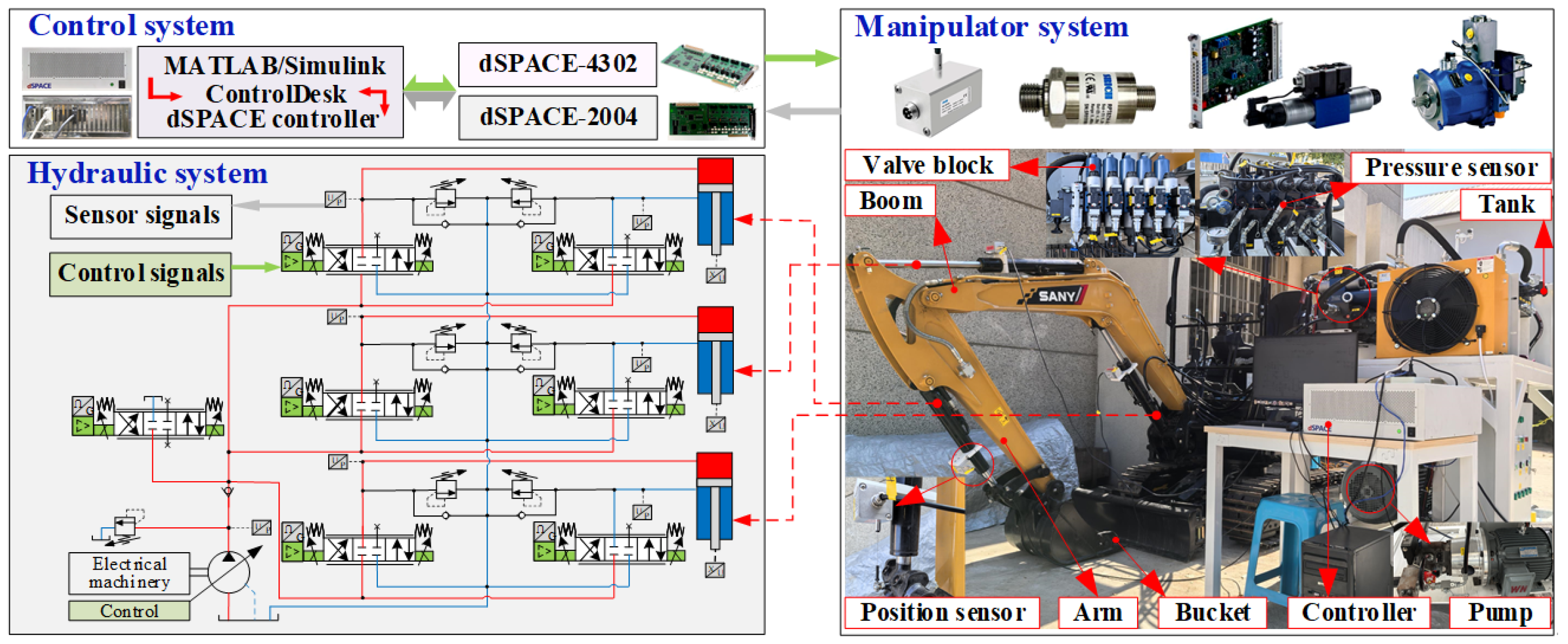

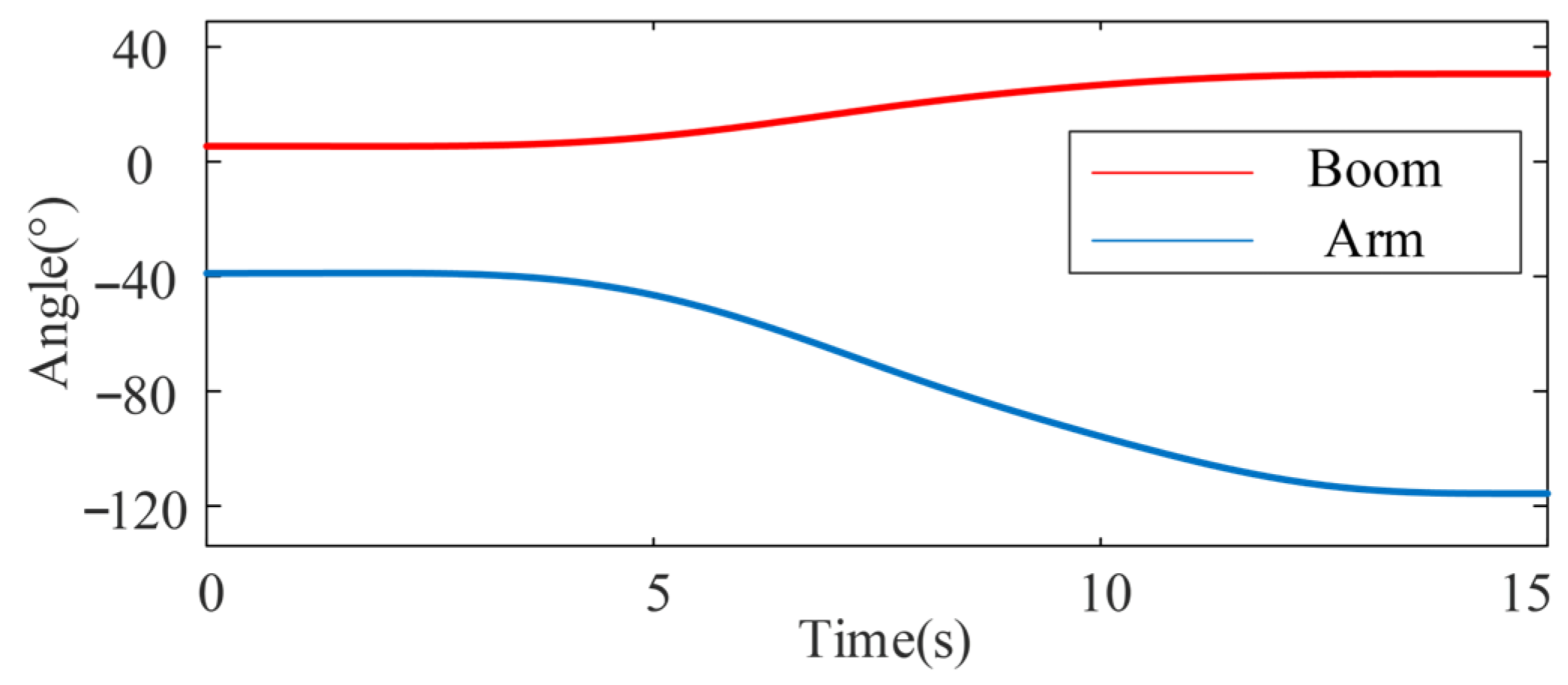

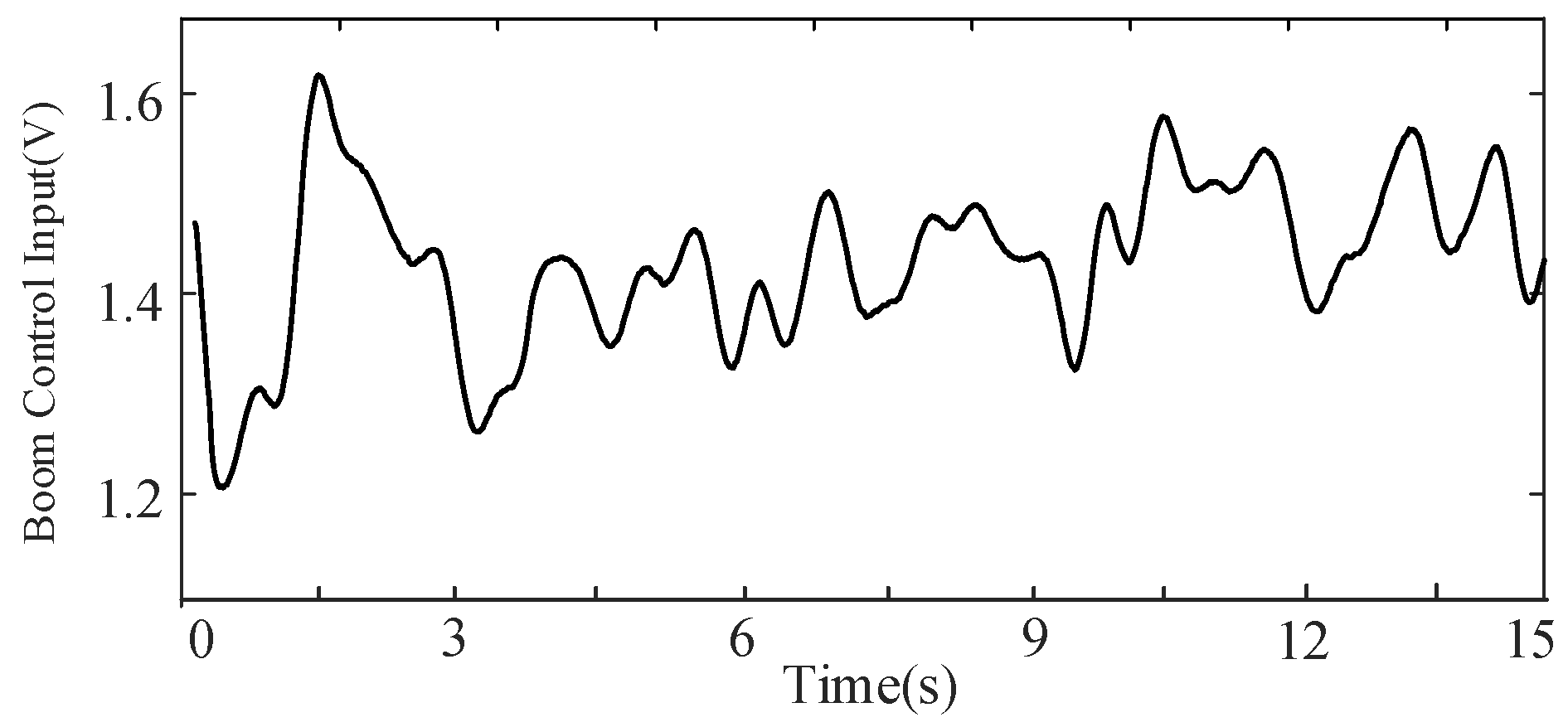

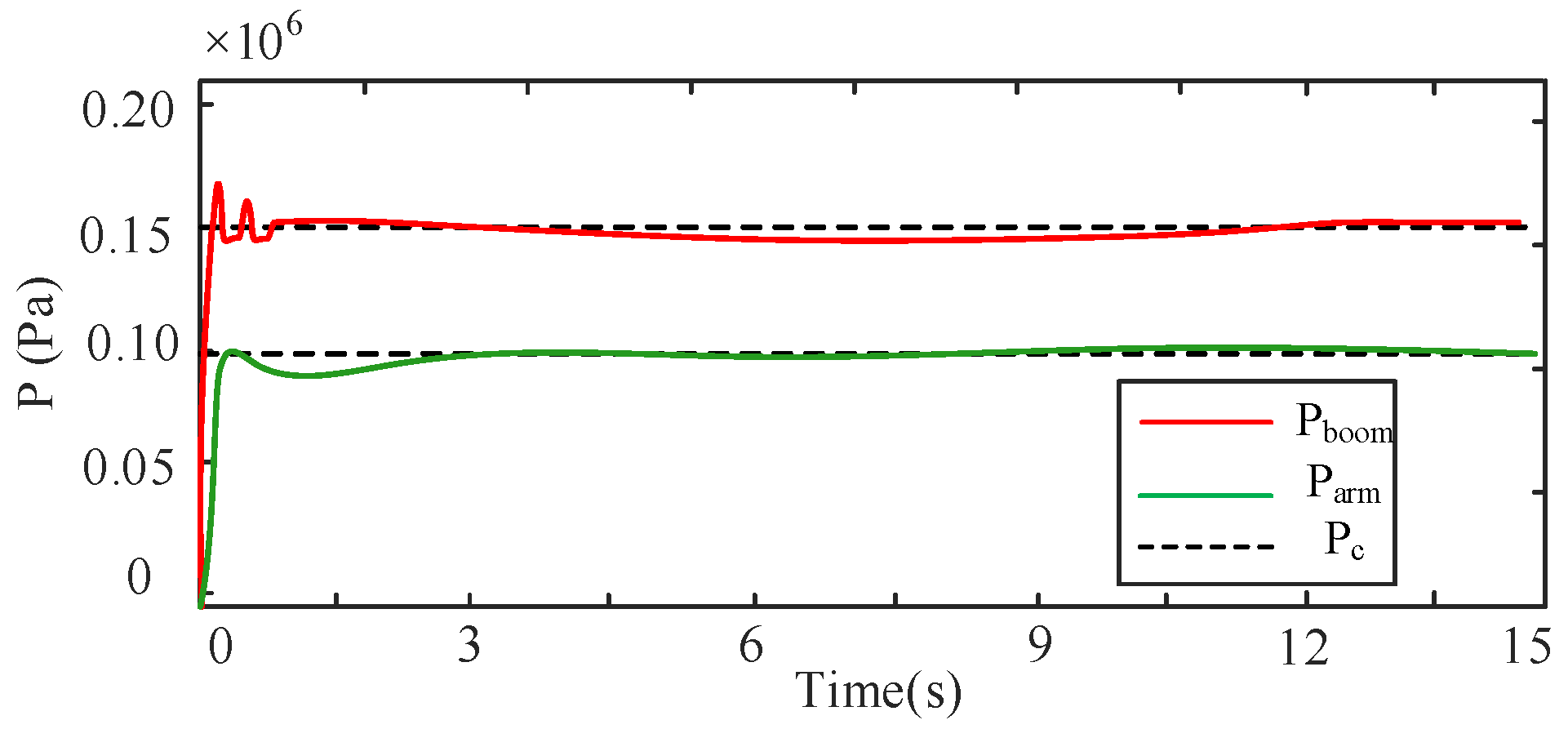

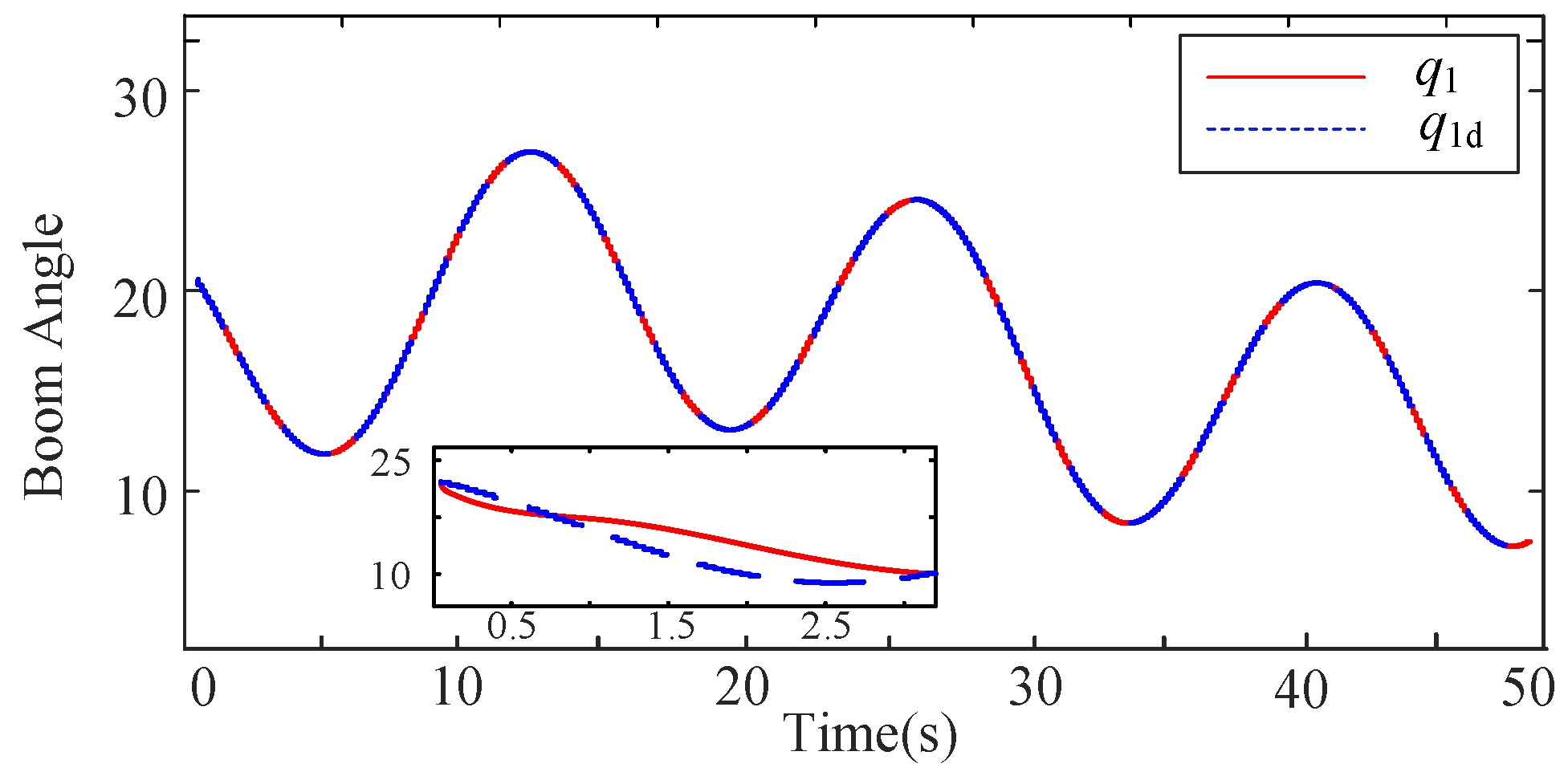

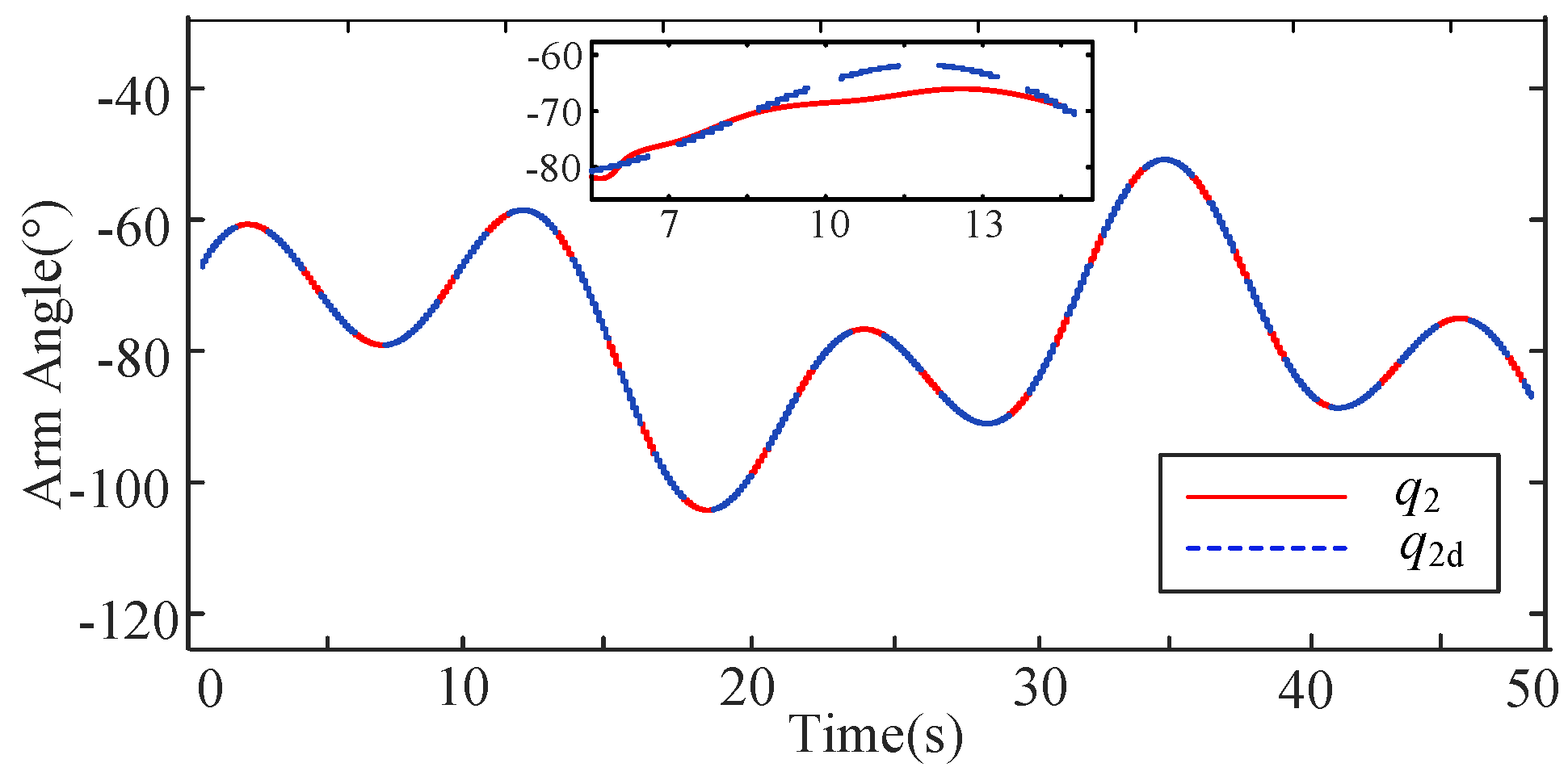

5. Experimental Verification

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| C1 | Proposed Controller (Adaptive Fuzzy Prescribed Performance Control) |

| C2 | Comparative Controller (Without Prescribed Performance Control) |

| DOF | Degree Of Freedom |

| DSC | Dynamic Surface Control |

| ESO | Extended State Observer |

| FLS | Fuzzy Logic System |

| IMS | Independent Metering System (or Load Port Independent Hydraulic System) |

| PPC | Prescribed Performance Control |

| PPF | Prescribed Performance Function |

| UUB | Uniformly Ultimately Bounded |

References

- Manring, N.D.; Fales, R.C. Hydraulic Control Systems; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.; Yang, H.; Gong, G.; Liu, H.; Hou, D. Energy saving of cutterhead hydraulic drive system of shield tunneling machine. Autom. Constr. 2014, 37, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xiao, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z. Automatic vision-based calculation of excavator earthmoving productivity using zero-shot learning activity recognition. Autom. Constr. 2023, 146, 104702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, B.; Palmberg, J.O. Individual metering fluid power systems: Challenges and opportunities. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. 2011, 225, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Tafazoli, S. Using Artificial Intelligence in Mining Excavators: Automating Routine Operational Decisions. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2021, 15, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, J.; Ling, J.; Yuan, J. Adaptive backstep controller with extended state observer for load following of nuclear power plant. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2021, 137, 103745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Xin, L.; Li, G.; Pan, J. Design of full-order state observer for two-mass joint servo system based on the fixed gain filter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 10466–10475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Yao, J. Extended-state-observer-based adaptive control of electrohydraulic servomechanisms without velocity measurement. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2019, 25, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.C.; Cuau, L.; Poignet, P.; Zemiti, N. Decoupled model predictive control for path following on complex surfaces. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 2046–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Sun, Q.; Chen, Z. Sliding mode control for electro-hydraulic proportional directional valve-controlled position tracking system based on an extended state observer. Asian J. Control 2021, 23, 1855–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tong, S. Observer-based neuro-adaptive optimized control of strict-feedback nonlinear systems with state constraints. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 3131–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, D.; Kim, W.; Tomizuka, M. High-gain-observer-based integral sliding mode control for position tracking of hydraulic servo systems. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2017, 22, 2695–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, H.; Shi, P. Decentralized adaptive fuzzy tracking control for robot finger dynamics. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2015, 23, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Tao, G.; Jiang, B. Dynamic surface control using neural networks for a class of uncertain nonlinear systems with input saturation. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2015, 26, 2086–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C.; Guan, X. Output feedback stabilization for time-delay nonlinear interconnected systems using neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2008, 19, 673–688. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Ai, C.; Kong, X. PID Control of Hydraulic Robotic Arm Based on Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wu, C.; Song, S.; Tejado, I. Fuzzy wavelet neural adaptive finite-time self-triggered fault-tolerant control for a quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicle with scheduled performance. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 131, 107832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Pan, Y.; Cao, L.; Chen, L. Predefined-Time Fault-Tolerant Consensus Tracking Control for Multi-UAV Systems with Prescribed Performance and Attitude Constraints. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 4058–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Biggs, J.D.; Duan, G. Post-capture attitude control with prescribed performance. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 96, 105572–105589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Chen, M.; Feng, G.; Wu, Q. Disturbance-observer-based adaptive fuzzy tracking control for unmanned autonomous helicopter with flight boundary constraints. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 31, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechlioulis, C.; Rovithakis, G. Robust adaptive control of feedback liearizable IMO nonlinear systems with prescribed performance. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2008, 53, 2090–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhou, Q.; Li, H.; Lu, R. Adaptive prescribed performance control of a flexible-joint robotic manipulator with dynamic uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 52, 12905–12915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, H.; Kong, X.; Ai, C. Mode Switching Control of Independent Metering Fluid Power Systems. ISA Trans. 2025, 158, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Li, C.; Ni, W.; Ma, H. A novel adaptive fuzzy prescribed performance congestion control for network systems with predefined settling time. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C.; Liu, G.; Li, L.; Guan, X. Adaptive fuzzy prescribed performance control for nonlinear switched time-delay systems with unmodeled dynamics. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2017, 26, 1934–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lin, Y. Decentralised adaptive dynamic surface control for a class of interconnected non-linear systems. IET Control Theory Appl. 2012, 6, 1172–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, J.; Yao, J. Neural network-based adaptive asymptotic prescribed performance tracking control of hydraulic manipulators. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2023, 53, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Celler, B.G.; Su, S.W. Neural adaptive backstepping control of a robotic manipulator with prescribed performance constraint. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 30, 3572–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, H.; Yu, J.; Na, J.; Ren, X. Neural-network-based adaptive funnel control for servo mechanisms with unknown dead-zone. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 50, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivumäki, J.; Zhu, W.H.; Mattila, J. Energy-efficient and high-precision control of hydraulic robots. Control Eng. Pract. 2019, 85, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Zhang, J.; Xu, B.; Cheng, M. Programmable hydraulic control technique in construction machinery: Status, challenges and countermeasures. Autom. Constr. 2018, 95, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Joint | Controller | MAE [deg] | STD [deg] | ITAE [deg·s] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boom | C1 (Proposed) | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.5 |

| C2 (w/o PPC) | 0.11 | 0.08 | 8.2 | |

| Arm | C1 (Proposed) | 0.05 | 0.03 | 2.1 |

| C2 (w/o PPC) | 0.15 | 0.10 | 12.5 |

| Actuator | Operational Condition | Controller | Average Return Pressure | Pressure Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boom | Flat-Ground (Figure 11) | C1 (Proposed) | 0.15 | ≈75% |

| Without Pressure Control | ≈0.6 | |||

| Arm | Flat-Ground (Figure 11) | C1 (Proposed) | 0.10 | ≈75% |

| Without Pressure Control | ≈0.4 | |||

| Boom | Complex Trajectory (Figure 14) | C1 (Proposed) | 0.15 | ≈78% |

| Without Pressure Control | ≈0.7 | |||

| Arm | Complex Trajectory (Figure 14) | C1 (Proposed) | 0.10 | ≈67% |

| Without Pressure Control | ≈0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Qi, X. Prescribed Performance Output Feedback Control of the Independent Metering Electro-Hydraulic System. Processes 2025, 13, 4007. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124007

Li Y, Qi X. Prescribed Performance Output Feedback Control of the Independent Metering Electro-Hydraulic System. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4007. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124007

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yuhe, and Xiaowen Qi. 2025. "Prescribed Performance Output Feedback Control of the Independent Metering Electro-Hydraulic System" Processes 13, no. 12: 4007. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124007

APA StyleLi, Y., & Qi, X. (2025). Prescribed Performance Output Feedback Control of the Independent Metering Electro-Hydraulic System. Processes, 13(12), 4007. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124007