Scheduling Optimization of Special Cable Production Workshop with AMR Constraints

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Literature Review

2. Problem Formulation Under AMR Constraints

2.1. Workshop Environment and Scheduling Requirements

- (1)

- All AMRs are at the scheduling center at time zero, and different AMRs do not interfere with each other during the transportation process.

- (2)

- All workpieces are in the warehouse at time zero.

- (3)

- The same machine can only process one workpiece at a specific time, and once the processing process starts, it cannot be interrupted.

- (4)

- AMR only performs one transportation task at a time and immediately executes the next task after the current task is completed.

- (5)

- Different workpieces have the same priority, but there are sequence constraints between the processes of the same workpiece.

- (6)

- When adjacent processes of the same workpiece are processed by the same machine, AMR transportation is not required.

- (7)

- The size of the machine’s buffer is unlimited, and the processing order of the workpieces in the buffer is determined by the decoding scheme.

- (8)

- All AMRs and machines are available at the start time.

- (9)

- These assumptions follow common practice in initial studies on AMR-constrained FJSP and represent well-organized shop floors with sufficiently large intermediate buffers and pre-planned collision-free routes. They allow us to focus on the core temporal coupling between machine processing and AMR transportation, which forms the foundation for subsequent extensions to more complex logistics environments.

- (10)

- Among the modeling assumptions introduced in this study, the use of unlimited intermediate buffers warrants specific clarification. In many cable production workshops, intermediate storage areas are designed with ample space and regulated by pull-based scheduling rules, making blocking between machines relatively rare under normal operating conditions. The infinite buffer assumption therefore provides a reasonable first-order approximation for such industrial settings and allows the analysis to focus on the temporal integration of AMR transportation and machine processing. Incorporating finite buffer capacities would require additional blocking constraints, queue state variables, and machine idle propagation rules, significantly increasing the complexity of both modeling and decoding. For this reason, the present study retains the infinite buffer assumption as a modeling baseline and instead performs sensitivity analysis on other operational assumptions that are more frequently adjustable in practice, such as AMR fleet size and travel time variations. Extending the model to explicitly account for finite buffers remains an important direction for future work.

- (11)

- In this study, an infinite buffer assumption is adopted in the main model to highlight the temporal coupling between machine processing and AMR transportation. However, in practical production systems, intermediate buffers are often finite, and blocking phenomena may occur under high-load or space-limited conditions. Specifically, finite buffer capacity may introduce the following effects: (i) direct blocking, where a completed operation cannot be released from the upstream machine because the downstream buffer is full, leading to forced machine idleness or processing resequencing; (ii) propagation of waiting, where local congestion propagates through subsequent stages and amplifies the impact of AMR delivery delays; and (iii) stronger AMR–machine coupling, in which the timing of AMR arrivals becomes more critical when buffer capacity is limited, potentially changing the optimal coordination pattern between AMRs and machines.

- (12)

- From a qualitative perspective, under low-to-moderate system loads, introducing moderate buffer limits is expected to increase the absolute makespan and total equipment load, while the relative performance advantage of the proposed improved SSA over the traditional SSA is likely to be preserved. In contrast, under extremely tight buffer settings (i.e., near-zero buffer) or very high system loads, blocking-induced cascading delays may fundamentally alter the scheduling structure, requiring explicit modeling of buffer occupancy constraints and state variables.

2.2. Mathematical Model Formulation

2.3. Mathematical Model

- (1)

- Minimize the maximum completion time

- (2)

- Minimize the total equipment load

3. Methodology

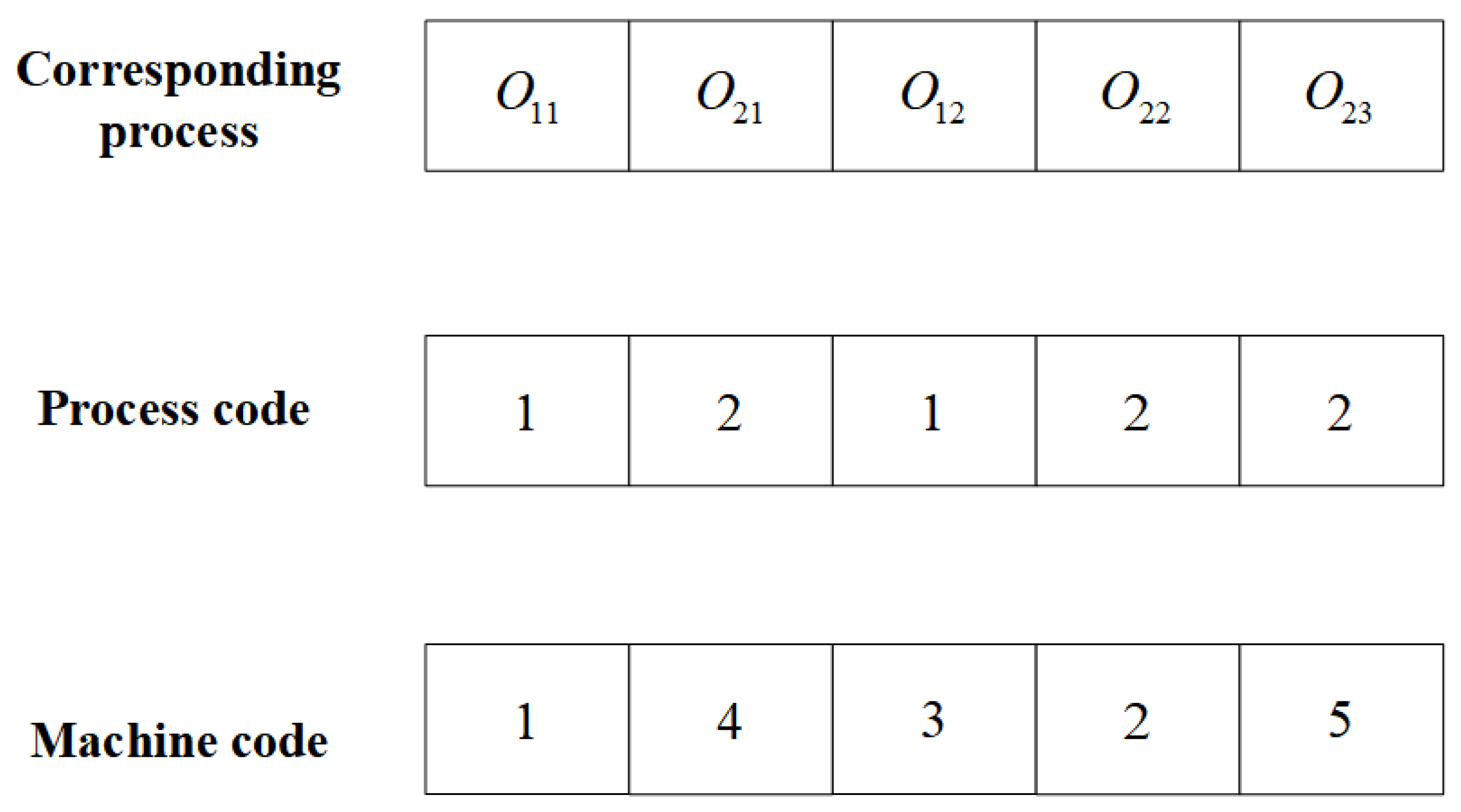

3.1. Solution Representation and Encoding Scheme

3.2. Decoding Procedure and Mathematical Definitions

| Algorithm 1: title Partial decoding process |

|

Input: OS—operation sequence MS—machine sequence t_iwj—processing time of process O_iw on machine j d(m1, m2)—AMR travel time between machines m1 and m2 (model input) t_iw-1^e—end time of previous process O_i, w-1 t_iwk^e-1—end time of the last task executed by AMR k Output: t_iwj^s, t_iwj^e—start and end times of process O_iw Ct_iwk^b, Ct_iwk^e, Lt_iwk^b, Lt_iwk^e—AMR timing variables At_iwk—total AMR transportation duration for O_iw Initialize MEnd[j] = 0 for each machine j Initialize t_iwk^e-1 = 0 for each AMR k Initialize Ct_iwk^b, Ct_iwk^e, Lt_iwk^b, Lt_iwk^e = 0 For each position p in OS: Identify process O_iw from OS(p) Determine assigned machine j = MS(p) Read processing time t_iwj Obtain t_iw-1^e # Step 1: AMR feasibility check CandidateSet = ∅ For each AMR k: empty_load_time = d(previous_machine, j) If t_iwk^e-1 + empty_load_time ≤ t_iw-1^e: Add k to CandidateSet # Step 2: AMR selection If CandidateSet ≠ ∅: Select AMR k with minimum (empty_load_time/loaded_time) Else: Select AMR k with minimum travel time d(·) # Step 3: compute AMR timing Ct_iwk^b = t_iwk^e-1 Ct_iwk^e = Ct_iwk^b + empty_load_time Lt_iwk^b = max(Ct_iwk^e, t_iw-1^e) Lt_iwk^e = Lt_iwk^b + loaded_time t_iwk^e-1 = Lt_iwk^e At_iwk = (Ct_iwk^e - Ct_iwk^b) + (Lt_iwk^e - Lt_iwk^b) # Step 4: machine timing t_iwj^s = max(MEnd[j], Lt_iwk^e) t_iwj^e = t_iwj^s + t_iwj MEnd[j] = t_iwj^e End For Return all machine times and AMR timing variables |

4. Improved SSA for Workshop Scheduling

4.1. Pareto-Based Sorting Mechanism

4.2. Elite Population Strategy

4.3. Adaptive Population Scaling

4.4. Algorithm Implementation Framework

| Algorithm 2: Improved SSA pseudocode |

| Input: N, T, ST, discoverer_prob, follower_prob, guard_prob Output: EliteArchive (Pareto optimal solutions) Initialize population P with N individuals EliteArchive ← ∅ for t = 1 to T do for each individual in P do Calculate F1 (makespan) using Equation (3) Calculate F2 (total equipment load) using Equation (4) end for [Fronts, Crowding] = ParetoSort(P) EliteArchive = UpdateEliteArchive(Fronts[1], EliteArchive) // Fronts[1] contains non-dominated solutions α = k ⋅ sin( (t/T) ⋅ π/2 ) // Equation (18) d_num = α ⋅ N // Equation (19) f_num = (1 − α) ⋅ N // Equation (20) // Assign roles based on Pareto rank and crowding Discoverers = SelectTopIndividuals(Fronts, d_num) Followers = SelectNextIndividuals(Fronts, f_num, d_num) Guards = RemainingIndividuals(Fronts, d_num + f_num) UpdateDiscovererPositions(Discoverers) UpdateFollowerPositions(Followers) UpdateGuardPositions(Guards) P = Combine(Discoverers, Followers, Guards) end for return EliteArchive Function ParetoSort(Population): // Non-dominated sorting Fronts = [] CurrentFront = FindNonDominated(Population) while CurrentFront ≠ ∅ do Fronts.append(CurrentFront) Remaining = Population \ CurrentFront CurrentFront = FindNonDominated(Remaining) end while // Crowding distance calculation for each front for each Front in Fronts do for each individual in Front do Calculate harmonic-mean crowding distance D_hm using Equation (17) end for Sort Front by D_hm descending end for return [Fronts, Crowding] |

4.5. Small-Scale Instance Validation Based on MIP

5. Experimental Study

5.1. Case Introduction and Data

5.2. Results and Comparative Analysis

5.3. Hyperparameter Sensitivity (Parameter Sweeps) and Robustness Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMRs | Autonomous Mobile Robots |

| SSA | Sparrow Search Algorithm |

| FJS | Flexible Job Shop |

| AGV | Automated Guided Vehicle |

References

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Dynamic complete rescheduling of flexible production workshop under order expedited disturbance. Manuf. Technol. Mach. Tools 2023, 4, 156–162. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, A.K.; Ashraf, M.H. Leveraging autonomous mobile robots for Industry 4.0 warehouses: A multiple case study analysis. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2024, 35, 1168–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Yeong, C.F.; Su, E.L.M. A review on energy efficiency in autonomous mobile robots. Robot. Intell. Autom. 2023, 43, 648–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-F.R.; Yusuf, S.H. Mobile Robot Navigation Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Processes 2022, 10, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. Research on Key Technologies of Automatic Navigation of Indoor Mobile Robots. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Nanjing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S. Research and Implementation of Mobile Robot Autonomous Navigation Applications. Master’s Thesis, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Azouaoui, O.; Ouadah, N.; Mansour, I.; Semani, A.; Aouana, S.; Djafer, C. Soft-computing based navigation approach for a bi-steerable mobile robot. Kybernetes 2013, 42, 241–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Chang, Q. Adaptive Mobile Robot Scheduling in Multiproduct Flexible Manufacturing Systems Using Reinforcement Learning. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2023, 145, 121005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yan, Y.; Hu, Y. Deep reinforcement learning for dynamic scheduling of energy-efficient automated guided vehicles. J. Intell. Manuf. 2024, 35, 3875–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, L.; Cordeau, J.-F.; Gaudioso, M.; Laporte, G. A branch-and-cut algorithm for the quay crane scheduling problem in a container terminal. Nav. Res. Logist. 2006, 53, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oike, S.; Tanaka, T.; Zhu, J.; Saito, Y. Robust Production Scheduling Using Autonomous Distributed Systems. Key Eng. Mater. 2012, 1813, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Hu, G. Job shop scheduling with AGVs under variable processing time. Int. J. Plan. Sched. 2021, 3, 114–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, T.; Inoue, K. Local and random searches for dispatch and conflict-free routing problem of capacitated AGV systems. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2016, 91, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deroussi, L.; Gourgand, M.; Tchernev, N. A simple metaheuristic approach to the simultaneous scheduling of machines and automated guided vehicles. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2008, 46, 2143–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmaguid, T.F.; Nassef, A.O.; Kamal, B.A.; Hassan, M.F. A hybrid GA/heuristic approach to the simultaneous scheduling of machines and automated guided vehicles. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2004, 42, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Song, Y.-J.; Zhang, Z.-S.; Xing, L.-N.; Ma, X.; Li, X.-J. Multi-mobile robots and multi-trips feeding scheduling problem in smart manufacturing system: An improved hybrid genetic algorithm. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2019, 16, 1729881419868126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, C.J. Intelligent scheduling using a neural network model in conjunction with reinforcement learning. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B 2005, 219, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sheu, J.; Teo, C.; Xue, G. Robot Scheduling for Mobile-Rack Warehouses: Human–Robot Coordinated Order Picking Systems. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2022, 31, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayouni, S.M.; Fontes, D.B.M.M.; Gonçalves, J.F. A multistart biased random key genetic algorithm for the flexible job shop scheduling problem with transportation. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2023, 30, 688–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Wang, Y. Scheduling optimization of ship pipe fittings flexible production workshop under dual resource constraints. Ship Eng. 2023, 45, 21–30+166. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Song, B.; Gu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X. Task scheduling method for intelligent warehouse item sorting robot based on improved chimpanzee optimization algorithm. Intell. Decis. Technol. 2025. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/18724981251314390 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Niu, Y. Research on Complex Manufacturing System Scheduling Problem Based on Hybrid Jaya Algorithm. Master’s Thesis, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fragapane, G.; de Koster, R.; Sgarbossa, F.; Strandhagen, J.O. Planning and control of autonomous mobile robots for intralogistics: Literature review and research agenda. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 294, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, T.; Hermann, J.; Kuhn, C.; Palm, D. Review of autonomous mobile robots in intralogistics: State-of-the-art, limitations and research gaps. Procedia CIRP 2024, 130, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Research on Multi-Objective Scheduling Optimization of Green Intelligent Manufacturing Workshop Based on ISSA. Master’s Thesis, Shenyang University, Shenyang, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, T. Study on Scheduling Optimization and Visualization Deduction of Segmented AGV Machining Workshop. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S.; Tang, H.; Li, X. Research on the inverse scheduling problem of flexible machining workshop considering dual resource constraints. China Mech. Eng. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Y. Scheduling of machines and multi-load AGVs in FMS based on differential evolution algorithm. Control. Decis. 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, M.; Zhang, Z.; Mao, K.; Ye, Y.; Pei, F. Digital-twin-based dynamic flexible job shop scheduling problem via multi-agent proximal policy optimisation. Digit. Twin 2025, 2, 2507007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qianfa, G.; Fu, G.U.; Linli, L.; Jianfeng, G. A framework of cloud-edge collaborated digital twin for flexible job shop scheduling with conflict-free routing. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 86, 102672. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S. Research on Optimization of Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem Based on Hybrid Sparrow Search Algorithm. Master’s Thesis, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J.; Shen, B. A novel swarm intelligence optimization approach: Sparrow search algorithm. Syst. Sci. Control. Eng. 2020, 8, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter Symbols | Definition |

|---|---|

| Type of workpieces to be processed | |

| -th workpiece to be processed | |

| The number of machines waiting to start | |

| Waiting for the -th machine to start | |

| The -th AMR | |

| AMR collection | |

| To be processed process | |

| Processing process collection | |

| The -th process of workpiece | |

| Transportation tasks required for process | |

| Processing time of process on machine | |

| The begin time of processing of process on machine | |

| The end time of process on machine | |

| The end time of the -th process of workpiece | |

| The no-load begin time before the AMR executes task | |

| The no-load end time before the AMR executes task | |

| The load begin time before AMR executes task | |

| The load end time before AMR executes task | |

| The end time of the last task executed by AMR | |

| The total time that the AMR takes to execute task | |

| The total time to complete the processing of workpiece | |

| The total machining time for all workpieces | |

| Total load of machines and AMRs |

| Workpiece | Process | Optional Processing Machines | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 7 | 4 | 3 | - | ||

| - | 9 | 5 | - | - | ||

| 4 | - | - | 5 | 6 | ||

| - | 6 | 4 | 3 | - | ||

| - | 8 | 10 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Machines | LU | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LU | 0 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| 3 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 5 | |

| 5 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 4 | |

| 2 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 6 | |

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 8 | |

| 6 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 0 |

| Task | Machine | AMR | Start | End |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | 0 | 6 | ||

| Empty-load move | — | 0 | 3 | |

| Loaded move | — | 6 | 9 | |

| — | 9 | 13 |

| Machine | Scheduled Operations |

|---|---|

| (2–5), (6–10) | |

| (7–9), (12–14) | |

| (4–8), (8–10), (16–18) |

| 9, 8 | |||

| 6, 9 | |||

| 8 | |||

| 7, 10 | |||

| 6, 10 | |||

| 9, 7 | |||

| 10, 6 | |||

| 3, 5 | |||

| 5, 9 | |||

| 7, 6, 9 | |||

| 6, 8, 8 | |||

| 8, 10, 5 | |||

| 7, 8, 9 | |||

| 7, 7, | |||

| 10, 5, 8 | |||

| 6, 7, 6 | |||

| 6, 7 | |||

| 9, 9 | |||

| 6, 5 | |||

| 4, 5, 6 | |||

| 3, 8 | |||

| 6, 7, 5 | |||

| 8, 4 | |||

| 7, 5 | |||

| 6, 5 |

| Machine | LU | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LU | 0 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 4.8 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 2.4 |

| 3.6 | 0 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 4.8 | 3.6 | 3.6 | |

| 1.2 | 2.4 | 0 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 3.6 | |

| 2.4 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 0 | 4.8 | 1.2 | 4.8 | 2.4 | |

| 4.8 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 4.8 | 0 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 2.4 | |

| 3.6 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 0 | 1.2 | 3.6 | |

| 1.2 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 4.8 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 0 | 4.8 | |

| 2.4 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 4.8 | 0 |

| Algorithm | Improved SSA | Traditional SSA | Improved Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | ||||

| Minimize the maximum completion time | 81.4 | 93.6 | 15.0% | |

| Total equipment load | 41.6 | 56.7 | 36.3% | |

| Metric | Improved SSA (Mean ± std) | Traditional SSA (Mean ± std) | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Makespan | 81.4 ± 2.7 | 93.6 ± 3.4 | p < 0.05 | Significant |

| Total Equipment Load | 41.6 ± 1.9 | 56.7 ± 2.3 | p < 0.05 | Significant |

| Algorithm | HV | IGD |

|---|---|---|

| NSGA-II | 10,551.924 ± 568.574 | 7.238 ± 3.473 |

| SPEA2 | 10,668.714 ± 599.871 | 9.904 ± 4.464 |

| MOEA/D | 10,757.984 ± 379.734 | 5.901 ± 1.709 |

| Improved SSA | 13,347.762 ± 333.665 | 8.220 ± 2.880 |

| AMR Fleet Size | Makespan (min) | Total Equipment Load |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 95.4 | 51.2 |

| 3 | 81.4 | 41.6 |

| 4 | 79.1 | 40.3 |

| 5 | 78.9 | 40.1 |

| Variant | Makespan (Mean ± std) | Total Equipment Load (Mean ± std) |

|---|---|---|

| Improved SSA (Full) | 81.4 ± 2.0 | 41.6 ± 1.5 |

| No Pareto + crowding | 89.5 ± 4.0 | 46.6 ± 3.0 |

| No elite archive | 91.4 ± 8.0 | 45.0 ± 5.0 |

| No adaptive scaling | 86.8 ± 3.0 | 42.4 ± 2.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ni, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tong, Y.; Zhang, H. Scheduling Optimization of Special Cable Production Workshop with AMR Constraints. Processes 2025, 13, 3992. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123992

Ni Z, Wang Y, Tong Y, Zhang H. Scheduling Optimization of Special Cable Production Workshop with AMR Constraints. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3992. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123992

Chicago/Turabian StyleNi, Zhen, Yalin Wang, Yifei Tong, and Hao Zhang. 2025. "Scheduling Optimization of Special Cable Production Workshop with AMR Constraints" Processes 13, no. 12: 3992. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123992

APA StyleNi, Z., Wang, Y., Tong, Y., & Zhang, H. (2025). Scheduling Optimization of Special Cable Production Workshop with AMR Constraints. Processes, 13(12), 3992. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123992