Recent Advances in Data-Driven Methods for Degradation Modeling Across Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

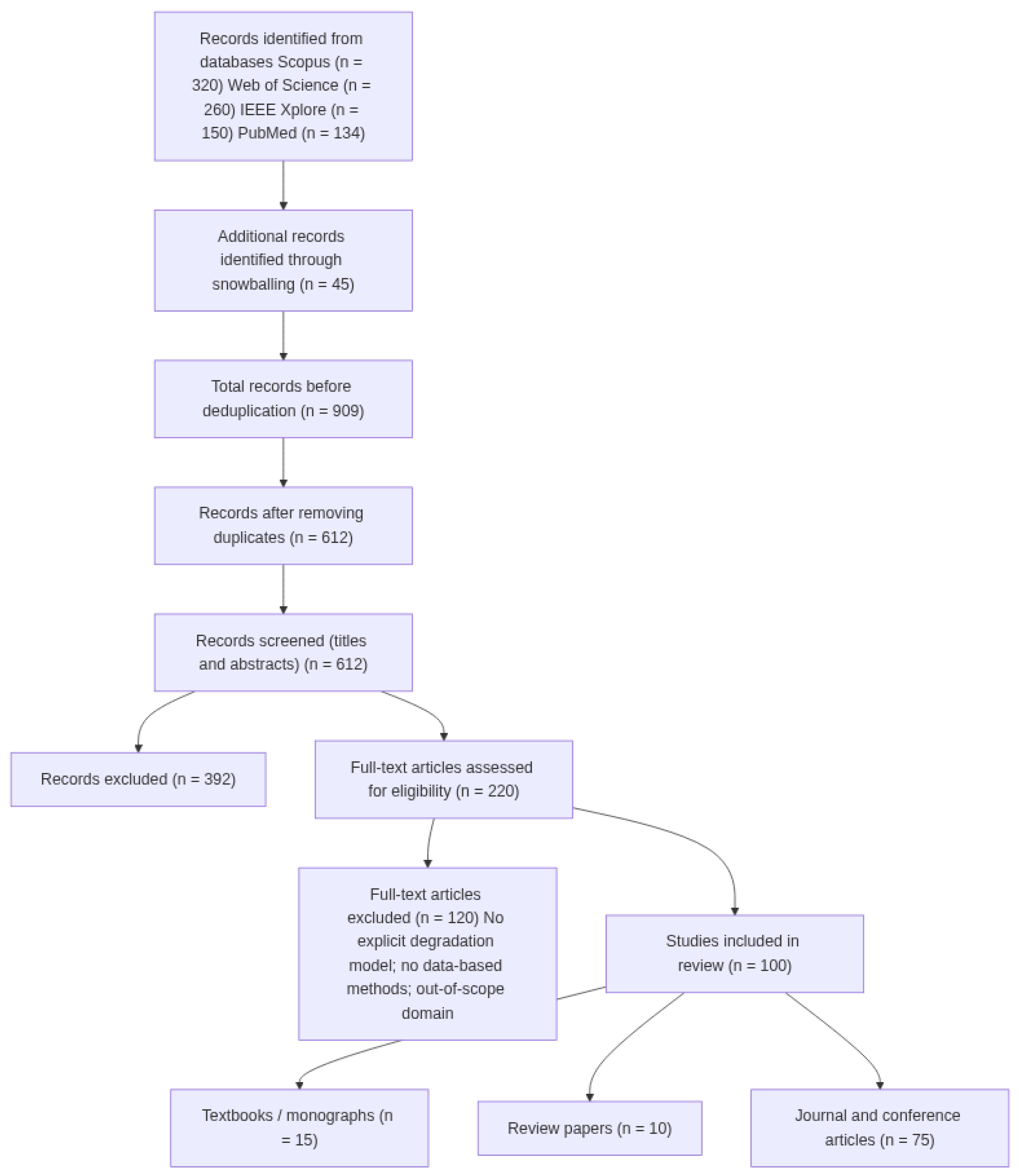

2. Review Methodology

2.1. Databases and Search Strategy

(degradation OR ageing OR aging OR “remaining useful life” OR RUL) AND (model* OR predict* OR prognos* OR “health index”)

AND (Bayesian OR stochastic OR “gamma process” OR “Wiener process” OR “hidden Markov” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “Gaussian process”)

AND (material* OR engineering OR “power system” OR medical OR clinical OR tissue OR organ)

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Screening

- Peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, books or book chapters in English.

- Explicit focus on modeling of a degradation process, understood as a time-evolving loss of function, performance, or structural integrity.

- Use of data-based, statistical, stochastic, or machine learning methods (possibly in combination with physical or knowledge-based components).

- Application within materials science, engineering systems, or medicine (as defined in Section 3).

- Purely physical or mechanistic models without any statistical or data-driven inference component.

- Works dealing exclusively with reliability or maintenance optimization without modeling an explicit degradation trajectory.

- Studies focused on domains outside the scope of this review (e.g., software reliability, database degradation, general quality-management systems, or purely cognitive/psychiatric models).

- Non-scholarly documents such as theses, technical reports, patents, and non-English publications.

2.3. Data Extraction and Categorization

- Application domain (materials science, engineering, medicine) and specific use case (e.g., corrosion, fatigue, power electronics, spinal disk degeneration).

- Type of degradation indicator (direct physical measurement, derived health index, clinical score, etc.).

- Primary model family (statistical inference, stochastic degradation process, dynamic prediction model, machine learning, or hybrid/physics-informed).

- Data characteristics (sample size, sampling frequency, dimensionality, presence of censored or missing observations).

- Reported performance metrics (when available), such as prediction error, classification accuracy, or reliability-related measures.

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Degradation Across Applications

3.2. Data-Based Degradation Modeling

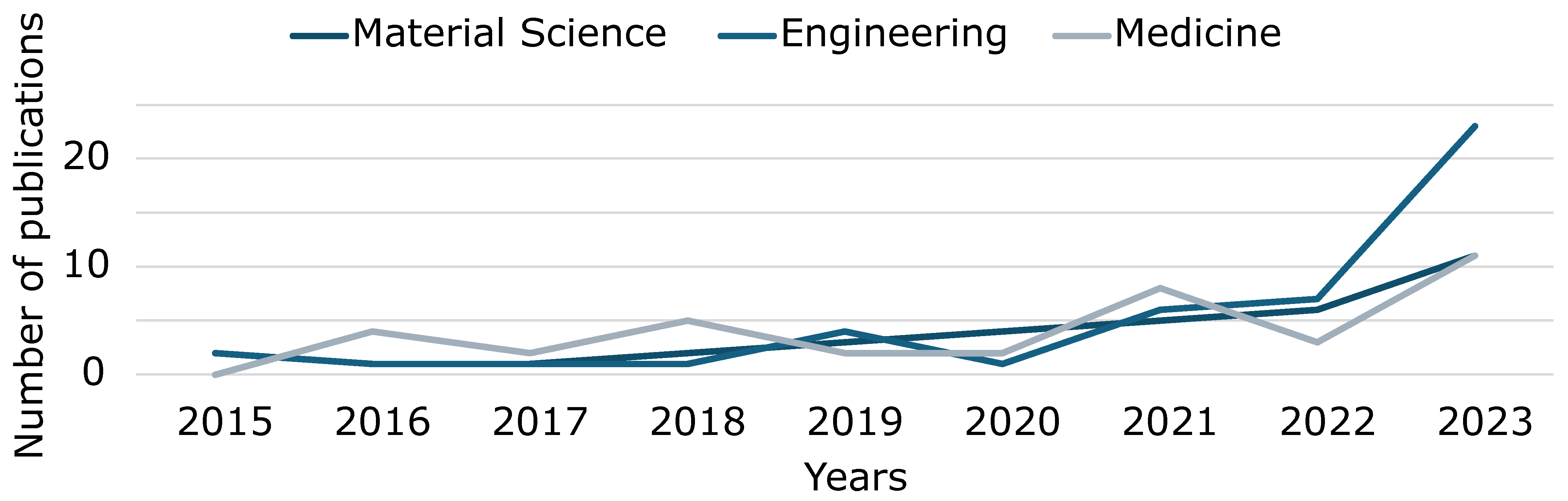

4. Background Analysis

4.1. Existing Reviews of Data-Based Degradation Modeling Methods

4.2. Comparative Analysis Across Years

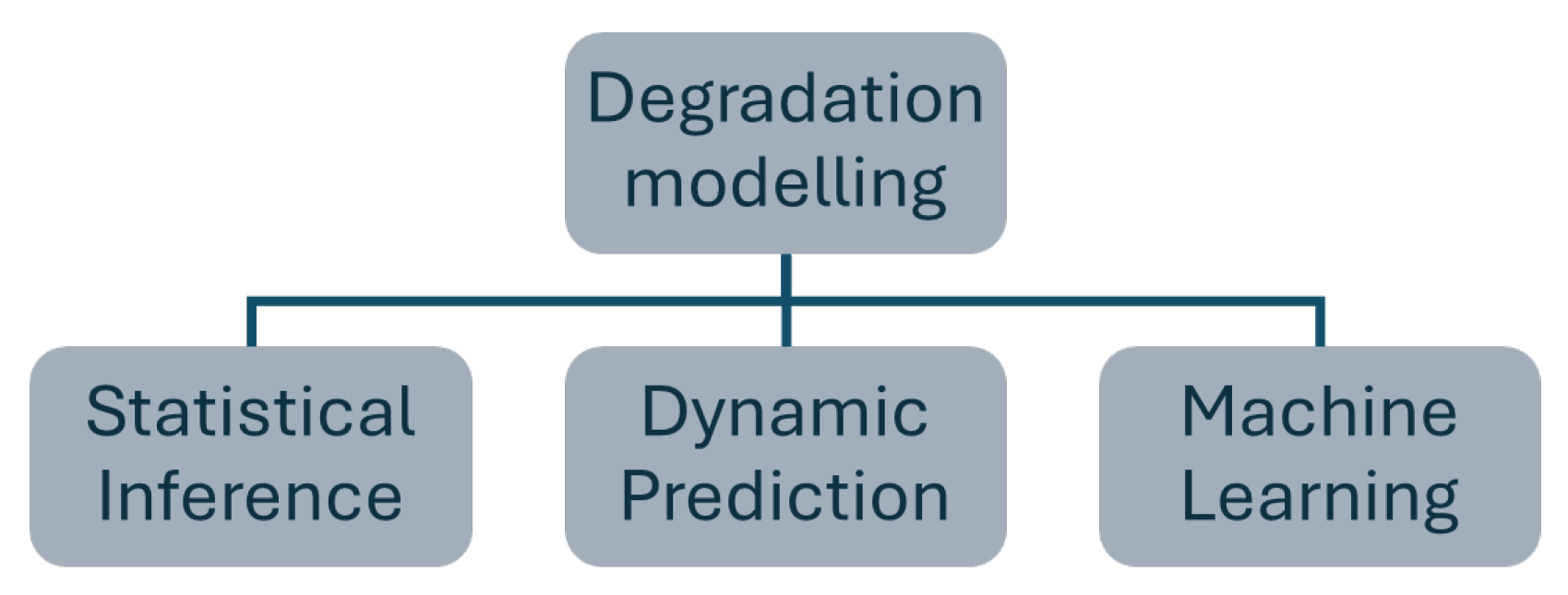

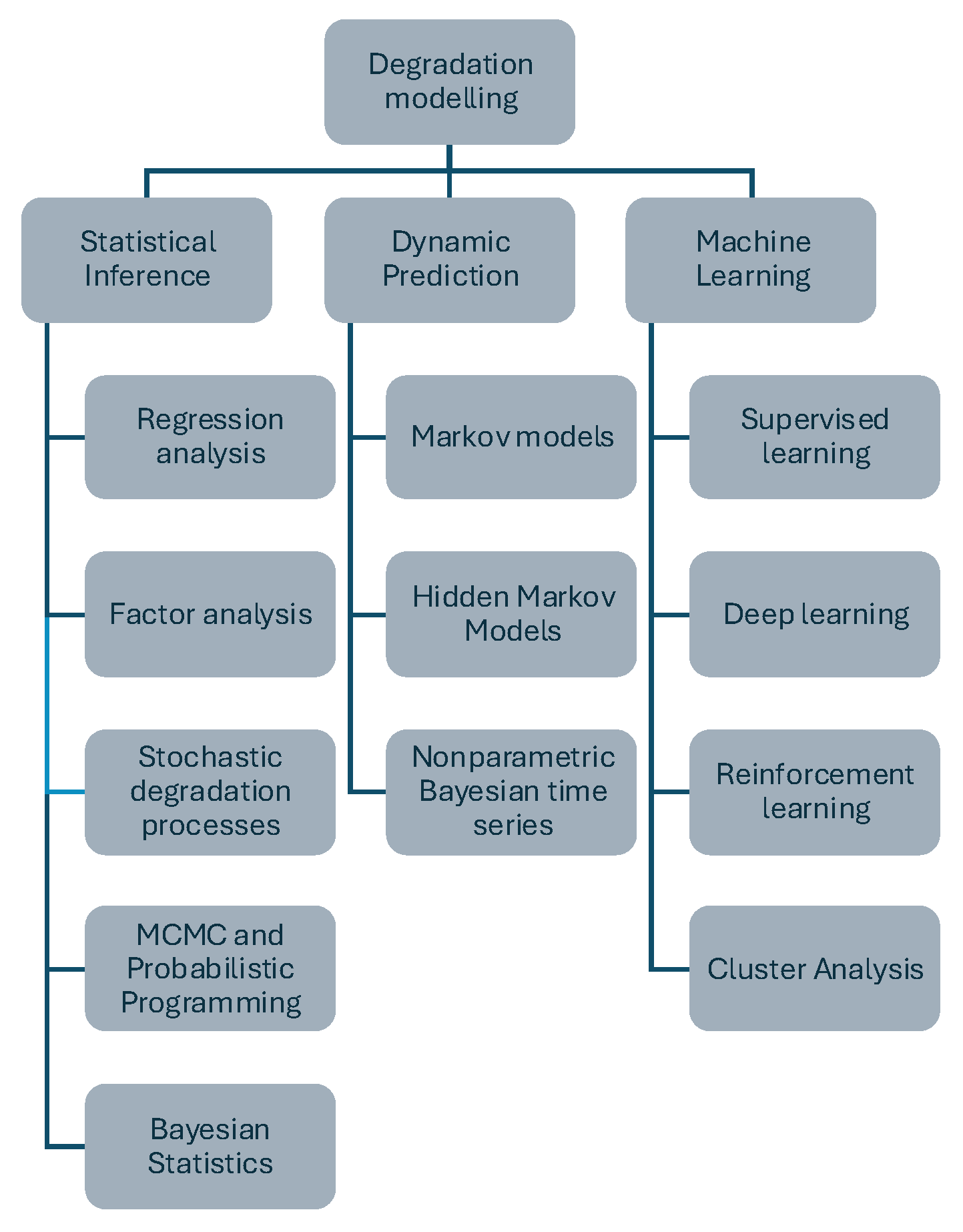

5. Classification with Respect to Methods

5.1. Statistical Inference

5.1.1. Regression Analysis

- Key advantages: simplicity, parameter interpretability (effect of each covariate on degradation), availability of closed-form estimators in the linear–Gaussian case, and well-established diagnostic tools.

- Limitations: reliance on linearity, independence, and homoscedasticity assumptions; sensitivity to extrapolation beyond the observed range; and potential misspecification when degradation dynamics are strongly nonlinear or regime-switching.

- Usage: In the power industry, regression analysis precisely describes degradation processes by identifying the relationship between process variables and degradation [52]. This allows for the rapid prediction of degradation based on known process parameters, optimizing maintenance activities.

5.1.2. Stochastic Degradation Processes

5.1.2.1. Gamma Process

5.1.2.2. Wiener Process

5.1.2.3. Inverse Gaussian and Related Processes

- Key advantages: natural representation of cumulative damage in continuous time; explicit modeling of uncertainty in degradation rate; closed-form results for failure probabilities and remaining useful life; parameters often have clear physical interpretation.

- Limitations: require careful selection of process family (gamma, Wiener, IG); parameter estimation may be difficult with sparse or noisy observations; incorporating covariates or complex operating conditions may require hierarchical or hybrid extensions.

- Usage: Gamma and Wiener processes are widely used for modeling monotonic or noisy degradation in materials (e.g., corrosion, fatigue), engineering systems (e.g., bearings, insulation, electronics), and selected biomedical indicators. They form the basis for reliability analyses and hybrid Bayesian–stochastic degradation models [3,54].

5.1.3. Factor Analysis

- Principal axis factoring, which iteratively estimates communalities and solves eigenvalue problems on the reduced correlation matrix.

- Maximum likelihood (ML), which finds estimates by maximizing the Gaussian log-likelihood under , where is the sample covariance.

- Key advantages: dimensionality reduction, uncovering latent constructs, and parsimonious modeling.

- Limitations: identifiability issues, sensitivity to distributional assumptions, and subjective choice of number of factors [55].

- Usage: In engineering processes, factor analysis can be used to identify groups of process variables [56]. They have a significant impact on degradation, leading to a better understanding of the degradation process.

5.1.4. Bayesian Statistics

- Point estimates, e.g., the posterior mean .

- Credible intervals, defined by .

- Posterior predictive distribution for a new observation ,

- Key advantages: coherent uncertainty quantification, flexible modeling of complex structures, and direct probability statements about parameters.

- Limitations: computational intensity, sensitivity to prior choices, and challenges in high-dimensional settings.

- Usage: In the context of dynamic degradation processes of biologically active substances, Bayesian statistics is used to update knowledge about degradation parameters based on clinical trial results [1,59]. This allows patient-specific variability in physiological parameters to be incorporated into the model and improves prediction of future degradation states, which is crucial for dosing and safety assessment.

5.1.5. Markov Chain Monte Carlo and Probabilistic Programming

- Key advantages: flexibility to model arbitrary posteriors, efficient exploration in high dimensions (HMC), and automatic uncertainty quantification.

- Limitations: convergence diagnostics required, choice of integrator step-size and path length in HMC, and potentially high computational cost.

- Usage: In the context of variable energy conditions, MCMC accounts for uncertainties in modeling the degradation of biologically active substances [29]. It enables effective prediction of future degradation states based on previous observations.

5.2. Dynamic Prediction

5.2.1. Markov Models

- Key advantages: simple formulation, closed-form n-step predictions, and well-studied theory of long-run behavior.

- Limitations: state-space discretization may be coarse, and the loss of history beyond the current state may oversimplify gradual degradation [62].

- Usage: In the context of discontinuous energy processes, Markov models are important for modeling abrupt degradation and considering dynamic changes in the degradation process, especially under changing energy conditions [63]. They also allow for the inclusion of nonlinear relationships between process variables and degradation.

5.2.2. Hidden Markov Models

- Initial distribution .

- Transition matrix with .

- Emission probabilities (or density for continuous ).

- Filtering/likelihood: via the forward recursion .

- Decoding: the Viterbi algorithm finds .

- Learning: Baum–Welch (EM) updates by maximizing the data likelihood.

- Key advantages: ability to model unobserved regimes, efficient inference via dynamic programming.

- Limitations: choice of state-space size, assumption of conditional independence of observations [66].

- Usage: In the context of discontinuous energy processes, Hidden Markov Models are important for modeling abrupt degradation [67]. It helps consider dynamic changes in the degradation process, especially under changing energy conditions.

5.2.3. Nonparametric Bayesian Time Series Modeling

5.2.3.1. Dirichlet Process Mixtures

5.2.3.2. Gaussian Process Regression

5.2.3.3. Prophet

- Key advantages: automatic changepoint detection, interpretable components, and scalability to large datasets.

- Limitations: assumes additive structure, may struggle with highly irregular dynamics, and limited probabilistic uncertainty beyond the MAP fit.

5.3. Machine Learning

5.3.1. Supervised Learning

- Regression: , predicting continuous degradation measures (e.g., wear rate).

- Classification: , labeling discrete states (e.g., “healthy” vs. “faulty”).

- Key advantages: direct use of labeled data, flexibility across tasks, and mature theory for generalization (e.g., VC-dimension, Rademacher complexity).

- Limitations: requires substantial labeled data, is sensitive to label noise, and has the potential for overfitting without proper regularization [72].

- Usage: In the power industry, supervised learning methods enable adaptive modeling of degradation [73]. It considers changing process conditions, and optimizing maintenance operations.

5.3.2. Deep Learning

- Key advantages: automatic feature learning, state-of-the-art predictive performance in large datasets, and flexible architectures for diverse data modalities.

- Limitations: large data and computational requirements, potential overfitting, and reduced interpretability of learned features [76].

- Usage: In the field of power engineering, deep learning facilitates advanced pattern recognition in modeling degradation and predicting energy processes [34]. It enables adaptive modeling of degradation risk in energy processes.

5.3.3. Reinforcement Learning

- is the state space, the action space.

- is the transition probability.

- is the immediate reward.

- is the discount factor.

- Q-learning (off-policy)

- Policy gradient (on-policy): optimize via

- Key advantages: learns adaptive policies without explicit system models; handles stochastic, nonstationary environments.

- Limitations: sample-inefficient; high variance in gradient estimates; requires careful tuning of hyperparameters [77].

- Usage: In the field of power engineering, reinforcement learning is used for adaptive degradation modeling [78]. It considers dynamic changes in the degradation process, especially under changing energy conditions.

5.3.4. Cluster Analysis

5.3.4.1. K-Means Clustering

5.3.4.2. Hierarchical Clustering

- Key advantages: no need for labeled data; can discover unknown structure; interpretable via centroids or dendrograms.

- Limitations: choice of K or cut-height is subjective; sensitive to scaling and noise; may find only spherical clusters (for K-means) or be computationally expensive ( for naive hierarchical implementations) [80].

- Usage: In the power industry, cluster analysis helps reduce data complexity by identifying important factors influencing degradation processes [81]. It enables mathematical modeling of various degradation cases, contributing to a better understanding of degradation processes.

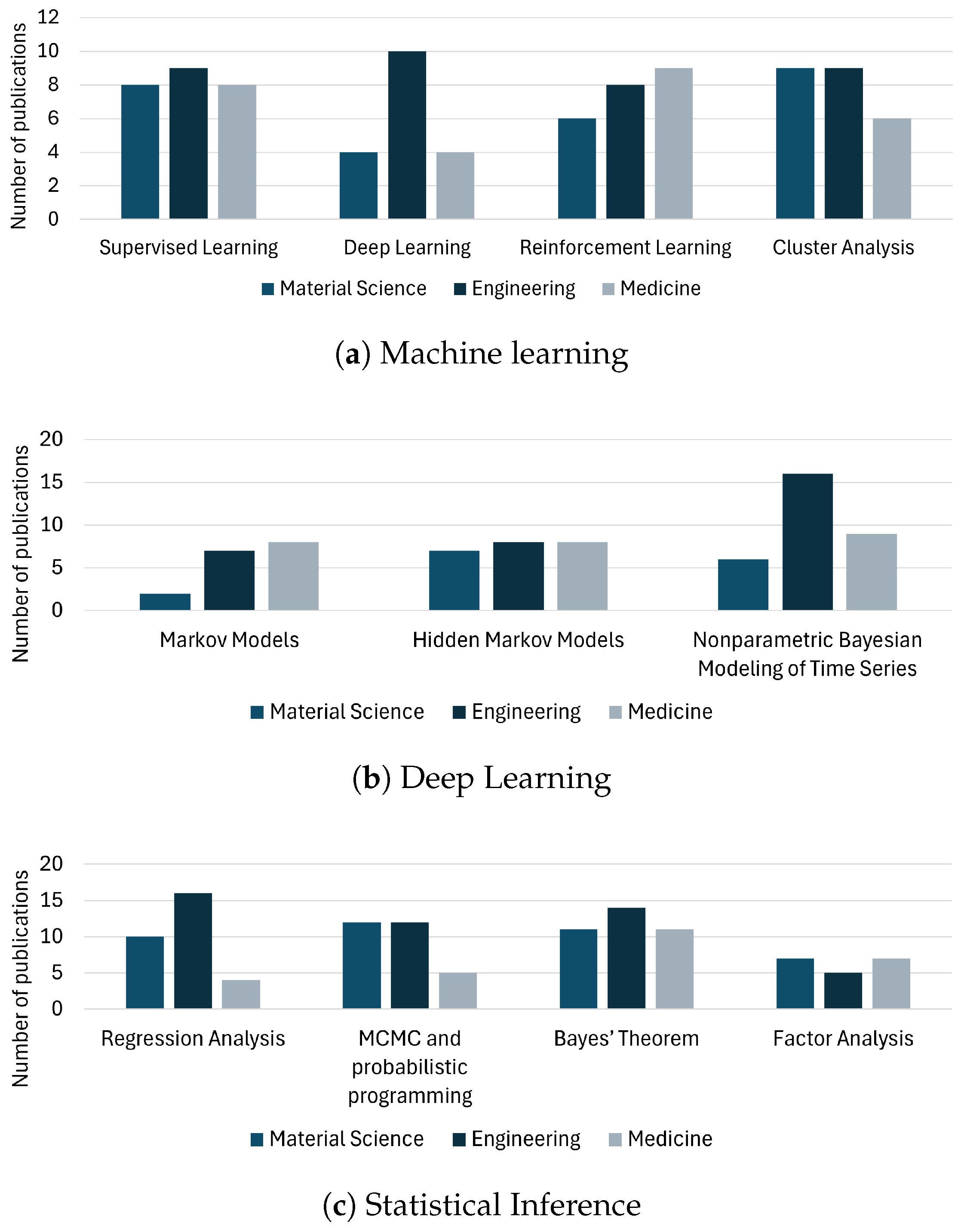

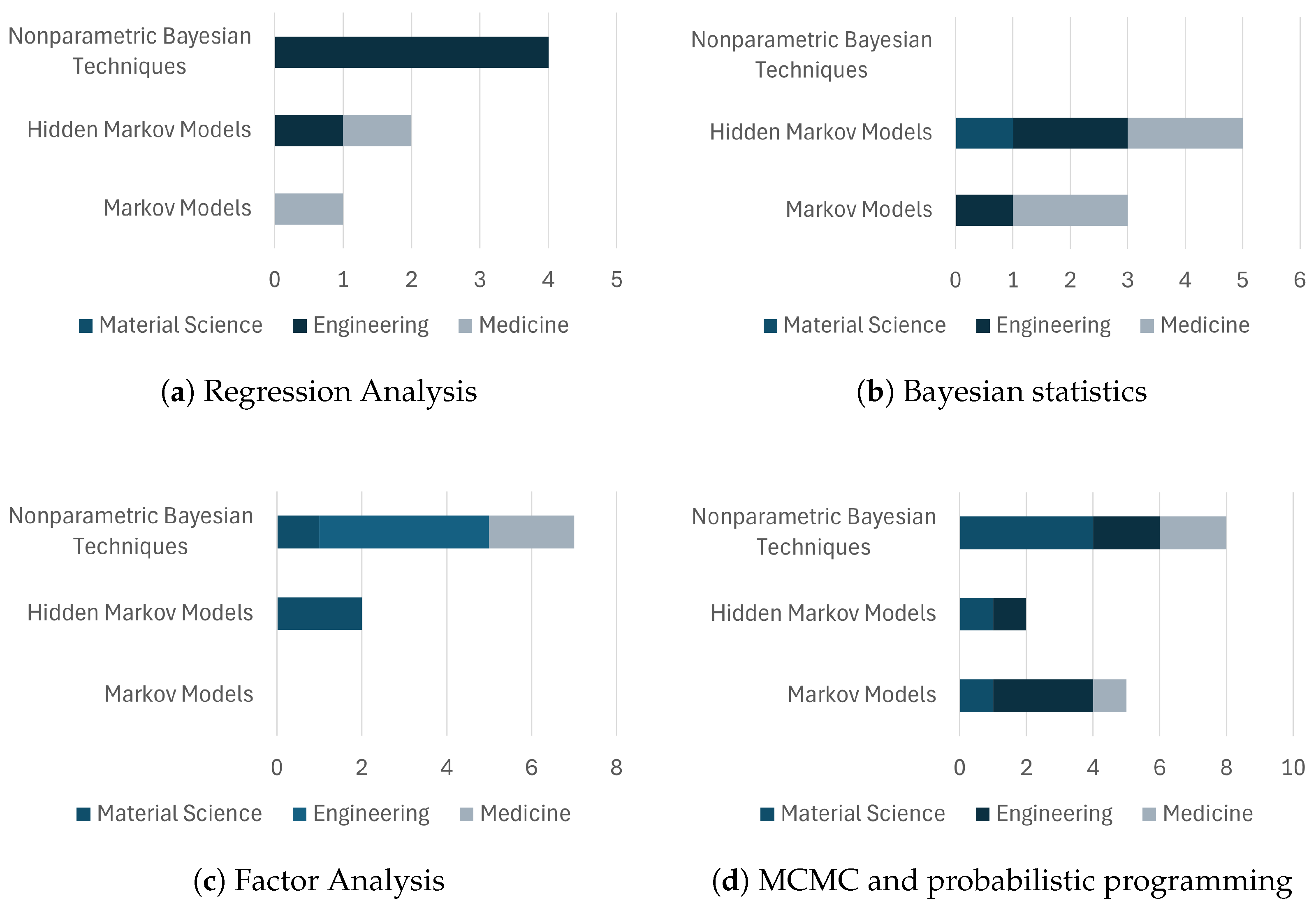

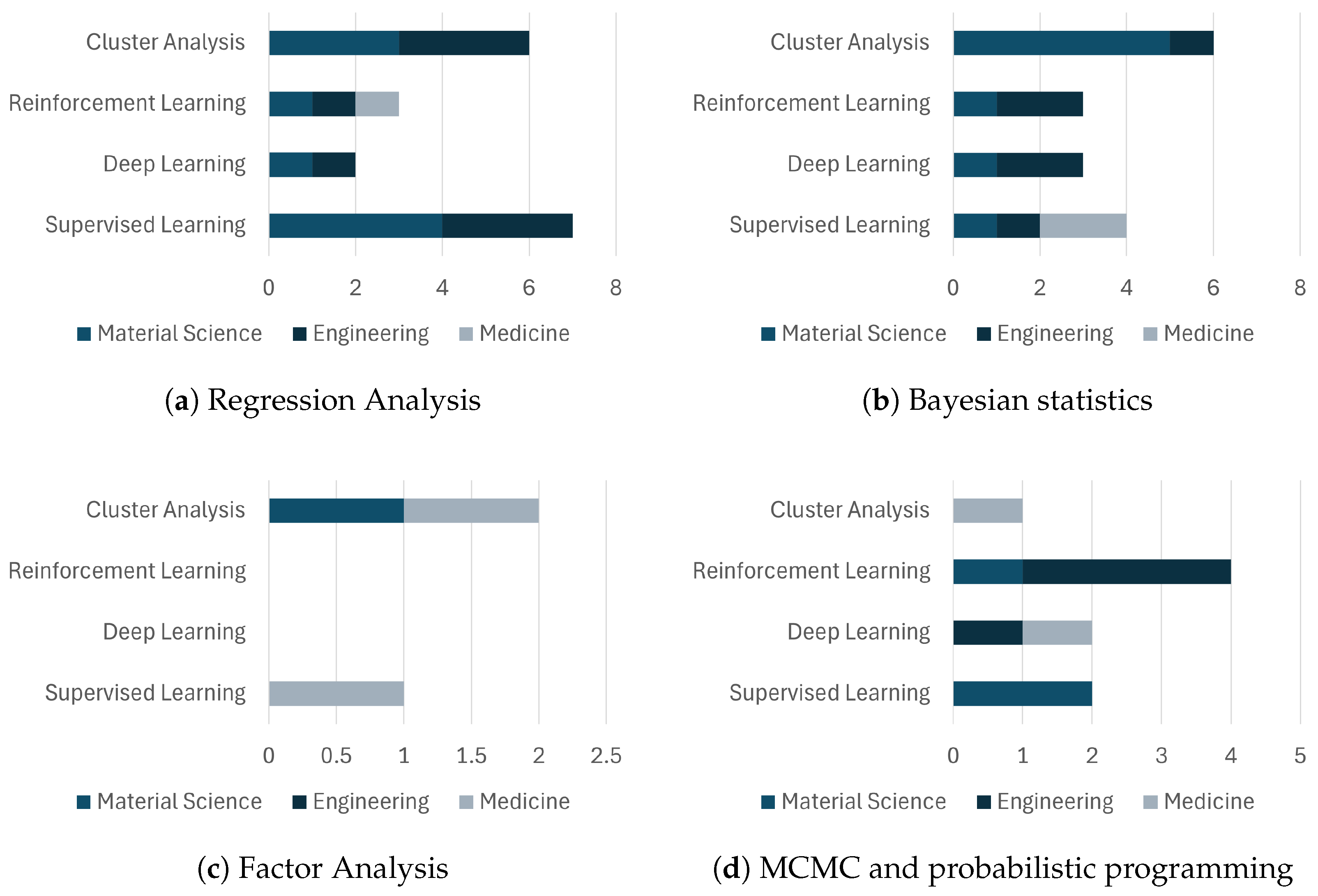

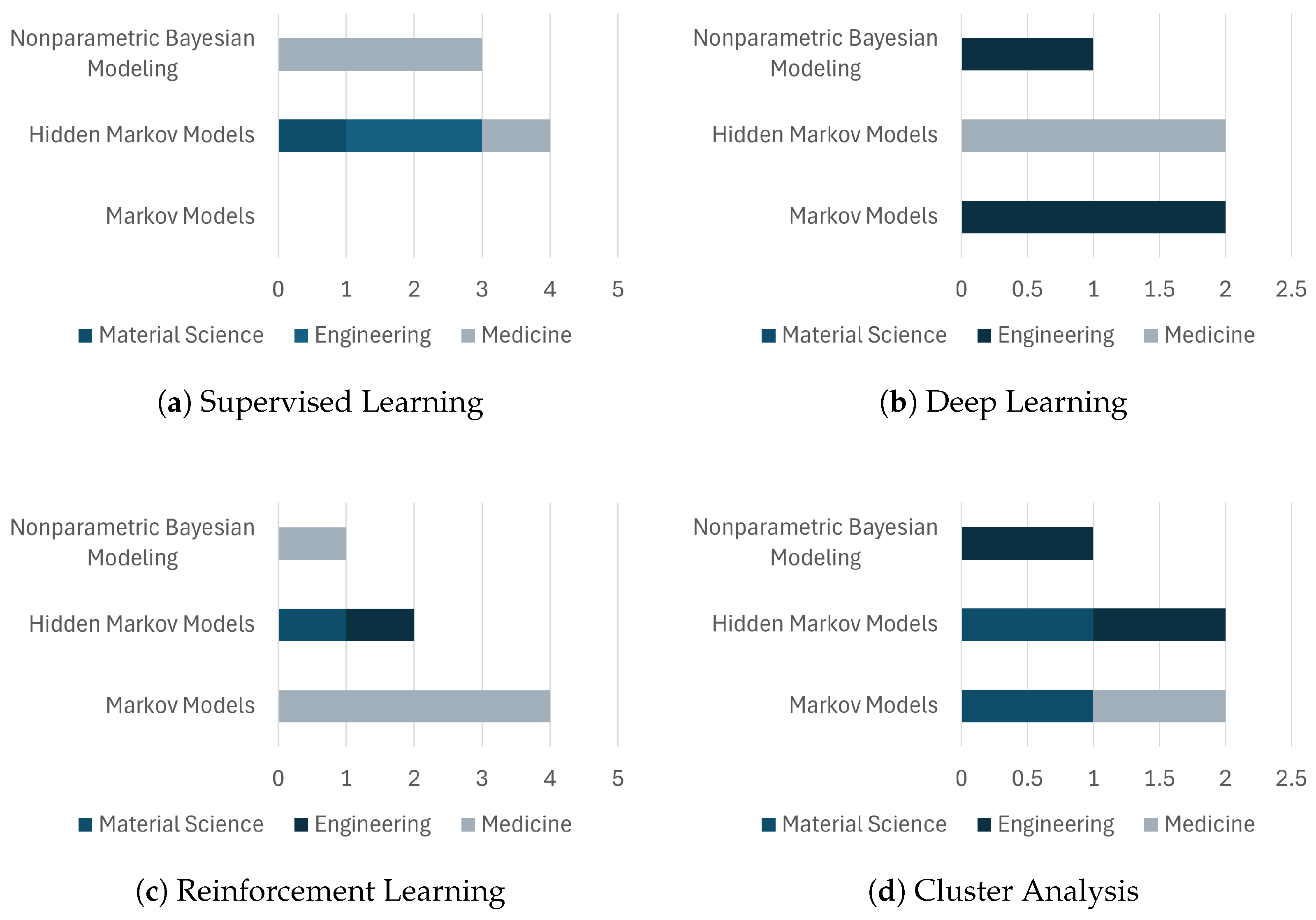

6. Classification of Methods and Their Usage Across Applications

6.1. Individual Methods

6.1.1. Statistical Inference Usage

6.1.2. Dynamic Prediction Usage

6.1.3. Machine Learning Usage

6.2. Method Selection Guidelines Across Data Types and Degradation Scenarios

6.3. Hybrid Methods

6.3.1. Statistical Inference and Dynamic Prediction

6.3.2. Statistical Inference and Machine Learning

6.3.3. Dynamic Prediction and Machine Learning

7. Discussion and Challenges

7.1. Discussion

7.2. Open Challenges

- Data quality, missingness, and heterogeneity.

- 2.

- Limited availability of benchmark datasets.

- 3.

- Uncertainty quantification and reliability of predictions.

- 4.

- Integration of physics-based and data-driven models.

- 5.

- Real-time and scalable degradation modeling.

- 6.

- Cross-domain generalization.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ISO | ISO |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| MCMC | Markov Chain Monte Carlo |

| HMC | Hamiltonian Monte Carlo |

| HMM | Hidden Markov Model |

| PPL | Probabilistic Programming Language |

| GP | Gaussian Process |

| DP | Dirichlet Process |

| MAP | Maximum a Posteriori (estimation) |

| EM | Expectation–Maximization (algorithm) |

| MDP | Markov Decision Process |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory (network) |

| RUL | Remaining Useful Life |

| VC | Vapnik–Chervonenkis (dimension) |

| H2S | Hydrogen sulfide |

References

- Shahraki, A.F.; Yadav, O.P.; Liao, H. A Review on Degradation Modelling and Its Engineering Applications. Int. J. Perform. Eng. 2017, 13, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pech, M.; Vrchota, J.; Bednar, J. Predictive Maintenance and Intelligent Sensors in Smart Factory: Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Noortwijk, J.M. A Survey of the Application of Gamma Processes in Maintenance. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2009, 94, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, N.; Ab-Samat, H.; Prasetyo, B.T. Maintenance strategies and energy efficiency: A review. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2023, 29, 640–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaime-Barquero, E.; Bekaert, E.; Olarte, J.; Zulueta, E.; Lopez-Guede, J.M. Artificial Intelligence Opportunities to Diagnose Degradation Modes for Safety Operation in Lithium Batteries. Batteries 2023, 9, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papargyri, L.; Theristis, M.; Kubicek, B.; Krametz, T.; Mayr, C.; Papanastasiou, P.; Georghiou, G.E. Modelling and experimental investigations of microcracks in crystalline silicon photovoltaics: A review. Renew. Energy 2020, 145, 2387–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagorowska, M.; Wu, O.; Ottewill, J.R.; Reble, M.; Thornhill, N.F. A survey of models of degradation for control applications. Annu. Rev. Control 2020, 50, 150–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Equeter, L.; Ducobu, F.; Riviere-Lorphevre, E.; Serra, R.; Dehombreux, P. An Analytic Approach to the Cox Proportional Hazards Model for Estimating the Lifespan of Cutting Tools. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2020, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.H.; Song, S.; Tao, L.; Qin, Z.; Wu, Z.; Gao, Z.; Wang, J.; Hu, W.; Behnamian, Y.; Luo, J.L. Material degradation assessed by digital image processing: Fundamentals, progresses, and challenges. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 53, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, S.; Initiative, T.A.D.N. A Novel Coupling Model of Physiological Degradation and Emotional State for Prediction of Alzheimer’s Disease Progression. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 10993-13:2010; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices. Part 13: Identification and Quantification of Degradation Products from Polymeric Medical Devices. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- ISO 10993-1:2018; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices. Part 1: Evaluation and Testing Within a Risk Management Process. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO 14971:2019; Medical Devices—Application of Risk Management to Medical Devices. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO 13485:2016; Medical Devices—Quality Management Systems—Requirements for Regulatory Purposes. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 55000:2024; Asset Management—Overview, Principles and Terminology. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- ISO 9001:2015; Quality Management Systems—Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- ISO 14001:2015; Environmental Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- ISO 50001:2018; Energy Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO 15156-1:2020; Petroleum and Natural Gas Industries—Materials for Use in H2S-Containing Environments in Oil and Gas Production — Part 1: General Principles for Selection of Cracking-Resistant Materials. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- ISO 6892-1:2019; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing. Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO 11469:2016; Plastics—Generic Identification and Marking of Plastics Products. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Habib, M.K.; Ayankoso, S.A.; Nagata, F. Data-Driven Modeling: Concept, Techniques, Challenges and a Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA), Takamatsu, Japan, 8–11 August 2021; pp. 1000–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Solomatine, D.; See, L.; Abrahart, R. Data-Driven Modelling: Concepts, Approaches and Experiences. In Practical Hydroinformatics: Computational Intelligence and Technological Developments in Water Applications; Abrahart, R.J., See, L.M., Solomatine, D.P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Chapter 2; pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Stoica, P.; Selen, Y. Model-order selection: A review of information criterion rules. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2004, 21, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Saleh, J.H. Machine learning for reliability engineering and safety applications: Review of current status and future opportunities. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 211, 107530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, S.; van der Vaart, A. Fundamentals of Nonparametric Bayesian Inference; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 1–646. [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas, R.O. Bayesian Inference: Observations and Applications; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heard, N. An Introduction to Bayesian Inference, Methods and Computation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–169. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, K.R. Introduction to Bayesian Statistics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 1–249. [Google Scholar]

- Au, S.K. Operational Modal Analysis: Modeling, Bayesian Inference, Uncertainty Laws; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–542. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, D.; Cemgil, A.T.; Chiappa, S. Bayesian Time Series Models; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; Volume 9780521196765. [Google Scholar]

- Ceniga, L. Analytical Models of Coherent-Interface-Induced Stresses in Composite Materials III; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–150. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, S. Deep Reinforcement Learning: Fundamentals, Research and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–514. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, T. Machine Learning Foundations: Supervised, Unsupervised, and Advanced Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–391. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J. Nonlinear Time Series: Semiparametric and Nonparametric Methods; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1–237. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, C. Reinforcement Learning Aided Performance Optimization of Feedback Control Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–127. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, M. Probability and Statistics for Computer Scientists, Third Edition; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 1–465. [Google Scholar]

- Riguzzi, F. Foundations of Probabilistic Logic Programming: Languages, Semantics, Inference and Learning, 2nd ed.; River Publishers: Gistrup, Denmark, 2022; pp. 1–505. [Google Scholar]

- Theodoridis, S. Machine Learning: A Bayesian and Optimization Perspective, Second Edition; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S.; Gelman, A.; Jones, G.L.; Meng, X.L. Handbook of Markov Chain Monte Carlo; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; pp. 1–592. [Google Scholar]

- Alimi, O.A.; Meyer, E.L.; Olayiwola, O.I. Solar Photovoltaic Modules’ Performance Reliability and Degradation Analysis—A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghout, T.; Benbouzid, M. A Systematic Guide for Predicting Remaining Useful Life with Machine Learning. Electronics 2022, 11, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Tayyebi, M.; Yarigarravesh, M.; Hu, G. A review of magnesium corrosion in bio-applications: Mechanism, classification, modeling, in-vitro, and in-vivo experimental testing, and tailoring Mg corrosion rate. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 12158–12181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Yang, J.; Yang, M.; Wang, D. An Improved Generic Hybrid Prognostic Method for RUL Prediction Based on PF-LSTM Learning. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 3509121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.; Kumbhar, G. Detection, Measurement, and Classification of Partial Discharge in a Power Transformer: Methods, Trends, and Future Research. IETE Tech. Rev. 2018, 35, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, S. Contemporary Machine Learning Approaches Towards Biomechanical Analysis in the Diagnosis and Prognosis Prediction of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review. Undergrad. Res. Nat. Clin. Sci. Technol. J. 2024, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakurkar, P.S.; Vora, D.; Patil, S.; Mishra, S.; Kotecha, K. Data-driven approach for AI-based crack detection: Techniques, challenges, and future scope. Front. Sustain. Cities 2023, 5, 1253627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Tomovic, M.M.; Zhang, C. Erosion degradation characteristics of a linear electro-hydrostatic actuator under a high-frequency turbulent flow field. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2018, 31, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, R.B.K. Degradation in gas turbine systems. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2001, 123, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C.; Peck, E.A.; Vining, G.G. Introduction to Linear Regression Analysis, 5th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Si, X.; Hu, C.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, J. Online remaining-useful-life estimation with a Bayesian-updated expectation-conditional-maximization algorithm and a modified Bayesian-model-averaging method. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2021, 64, 112205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejaoui, I.; Bruneo, D.; Xibilia, M.G. A Data-Driven Prognostics Technique and RUL Prediction of Rotating Machines Using an Exponential Degradation Model. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies, CoDIT 2020, Prague, Czech Republic, 29 June–2 July 2020; pp. 703–708. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Z.S.; Xie, M. Stochastic modelling and analysis of degradation for highly reliable products. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2015, 142, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, D.J.; Knott, M.; Moustaki, I. Latent Variable Models and Factor Analysis: A Unified Approach, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Hong, Y.; Jin, R. Nonlinear general path models for degradation data with dynamic covariates. Appl. Stoch. Model. Bus. Ind. 2016, 32, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Wang, B.; Hong, Y.; Ye, Z. General Path Models for Degradation Data With Multiple Characteristics and Covariates. Technometrics 2021, 63, 354–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A.; Carlin, J.B.; Stern, H.S.; Dunson, D.B.; Vehtari, A.; Rubin, D.B. Bayesian Data Analysis, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dadash, A.H.; Björsell, N. Optimal Degradation-Aware Control Using Process-Controlled Sparse Bayesian Learning. Processes 2023, 11, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, R.M. MCMC Using Hamiltonian Dynamics. In Handbook of Markov Chain Monte Carlo; Brooks, S., Gelman, A., Jones, G.L., Meng, X.L., Eds.; Chapman & Hall/CRC: London, UK, 2011; pp. 113–162. [Google Scholar]

- Tamssaouet, F.; Nguyen, K.T.; Medjaher, K.; Orchard, M.E. System-level failure prognostics: Literature review and main challenges. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part O J. Risk Reliab. 2023, 237, 524–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, J.R. Markov Chains; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Lange, K. Composition Markov chains of multinomial type. Adv. Appl. Probab. 2009, 41, 270–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bulinski, Z.; Orlande, H.R. Estimation of the non-linear diffusion coefficient with Markov Chain Monte Carlo method based on the integral information. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 2017, 27, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, S.; Guo, Y.; Chu, Y. Robust adaptive output-feedback control for a class of nonlinear systems with time-varying actuator faults. Int. J. Adapt. Control. Signal Process. 2010, 24, 743–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiner, L.R. A Tutorial on Hidden Markov Models and Selected Applications in Speech Recognition. Proc. IEEE 1989, 77, 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.B.; Zhang, J.X.; Zhou, Z.J.; Si, X.S.; Hu, C.H. Estimating Remaining Useful Life for Degrading Systems with Large Fluctuations. J. Control. Sci. Eng. 2018, 2018, 9182783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, S.; Quang, T.L.; Holub, O.; Endel, P. Real-time monitoring energy efficiency and performance degradation of condensing boilers. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 136, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.; Letham, B. Forecasting at scale. Am. Stat. 2018, 72, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Yang, Q.; King, C.B.; Hong, Y. A General Accelerated Destructive Degradation Testing Model for Reliability Analysis. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2019, 68, 1272–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ma, Y. Ensemble Machine Learning: Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 1–329. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, A.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Q.; Sun, G.; He, J.; Lin, S. Remaining Useful Life Prediction for Rotating Machinery Based on Optimal Degradation Indicator. Shock Vib. 2017, 2017, 6754968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, R.; Gong, W.; Chen, Y. Model-driven degradation modeling approaches: Investigation and review. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2020, 33, 1137–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, W.J.d.S. Shallow and Deep Artificial Neural Networks for Structural Reliability Analysis. ASCE-ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Part B Mech. Eng. 2020, 6, 041006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Samaranayake, L.; Longo, S. Degradation Control for Electric Vehicle Machines Using Nonlinear Model Predictive Control. IEEE Trans. Control. Syst. Technol. 2018, 26, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Pan, R.; Hong, Y. Copula-based reliability analysis of degrading systems with dependent failures. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Safety 2020, 193, 106618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, L.; Rousseeuw, P.J. Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- de Lima, M.J.; Paredes Crovato, C.D.; Goytia Mejia, R.I.; da Rosa Righi, R.; de Oliveira Ramos, G.; André da Costa, C.; Pesenti, G. HealthMon: An approach for monitoring machines degradation using time-series decomposition, clustering, and metaheuristics. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 162, 107709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, A.; Madheswaran, D.K.; Kumar, N.M. A critical assessment on functional attributes and degradation mechanism of membrane electrode assembly components in direct methanol fuel cells. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Sen, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Khan, M.U.; Mao, L.; Jiang, F.; Xu, T.; Zhang, G.; et al. Addressing sodium ion-related degradation in SHJ cells by the application of nano-scale barrier layers. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2024, 264, 112604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Bravo, G.; Vite-Torres, M.; Godínez-Salcedo, J. Corrosion rate and wear mechanisms comparison for AISI 410 stainless steel exposed to pure corrosion and abrasion-corrosion in a simulated marine environment. Tribol. Ind. 2019, 41, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Luo, X.; Chen, Q. Degradation of Steel Rebar Tensile Properties Affected by Longitudinal Non-Uniform Corrosion. Materials 2023, 16, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, V.A.; Karlsson, L.; Wessman, S.; Fuertes, N. Effect of sigma phase morphology on the degradation of properties in a super duplex stainless steel. Materials 2018, 11, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeller-Plumhoff, B.; Laipple, D.; Slominska, H.; Iskhakova, K.; Longo, E.; Hermann, A.; Flenner, S.; Greving, I.; Storm, M.; Willumeit-Römer, R. Evaluating the morphology of the degradation layer of pure magnesium via 3D imaging at resolutions below 40 nm. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 4368–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mahdi, H.; Leahy, P.G.; Morrison, A.P. Experimentally derived models to detect onset of shunt resistance degradation in photovoltaic modules. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Yuan, M.M.; Qiao, W.J.; Li, N.N.; Du, B. Mechanical Degradation of Q345 Weathering Steel and Q345 Carbon Steel under Acid Corrosion. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 6764915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessio, R.P.; Andre, N.M.; Goushegir, S.M.; dos Santos, J.F.; Mazzaferro, J.A.E.; Amancio-Filho, S.T. Prediction of the mechanical and failure behavior of metal-composite hybrid joints using cohesive surfaces. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 24, 101205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, S.; Sofiani, F.M.; Chaudhuri, S.; Balbin, J.; Larrosa, N.; De Waele, W. Investigation of the effect of pitting corrosion on the fatigue strength degradation of structural steel using a short crack model. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2023, 51, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, S.; Wei, D.; Si, L.; Yu, K.; Yan, K. Dynamics simulation-driven fault diagnosis of rolling bearings using security transfer support matrix machine. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 243, 109882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, T.; Verma, K. Reliability based computational model for stochastic unit commitment of a bulk power system integrated with volatile wind power. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 244, 109949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Li, Y.F. Out-of-distribution detection-assisted trustworthy machinery fault diagnosis approach with uncertainty-aware deep ensembles. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 226, 108648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osara, J.A.; Bryant, M.D. A thermodynamic model for lithium-ion battery degradation: Application of the degradation-entropy generation theorem. Inventions 2019, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, P.; Zhang, A.; Sui, X.; Wang, D.; Yin, L.; Wen, Z. Analysis of Performance Degradation in Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on a Lumped Particle Diffusion Model. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 32884–32891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchurov, N.I.; Dedov, S.I.; Malozyomov, B.V.; Shtang, A.A.; Martyushev, N.V.; Klyuev, R.V.; Andriashin, S.N. Degradation of lithium-ion batteries in an electric transport complex. Energies 2021, 14, 8072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroe, D.I.; Swierczynski, M.; Kær, S.K.; Teodorescu, R. Degradation Behavior of Lithium-Ion Batteries During Calendar Ageing - The Case of the Internal Resistance Increase. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2018, 54, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oria, C.; Méndez, C.; Carrascal, I.; Ferreño, D.; Ortiz, A. Degradation of the compression strength of spacers made of high-density pressboard used in power transformers under the influence of thermal ageing. Cellulose 2023, 30, 6539–6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunathilake, D.; Vilathgamuwa, M.; Mishra, Y.; Corry, P.; Farrell, T.; Choi, S.S. Degradation-Conscious Multiobjective Optimal Control of Reconfigurable Li-Ion Battery Energy Storage Systems. Batteries 2023, 9, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Deshpande, R.D.; Pan, J.; Cheng, Y.T.; Battaglia, V.S. Electrode side reactions, capacity loss and mechanical degradation in lithium-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, A2026–A2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Luo, Y.; Peng, Y.; Peng, X.; Pecht, M. Lithium-ion battery remaining useful life estimation based on nonlinear AR model combined with degradation feature. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Prognostics and Health Management Society, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 23–27 September 2012; pp. 336–342. [Google Scholar]

- Spitthoff, L.; Wahl, M.S.; Lamb, J.J.; Shearing, P.R.; Vie, P.J.S.; Burheim, O.S. On the Relations between Lithium-Ion Battery Reaction Entropy, Surface Temperatures and Degradation. Batteries 2023, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Deng, B.; Tang, S.; Sun, X.; Fang, P.; Si, X.; Han, X. Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on a Cubic Polynomial Degradation Model and Envelope Extraction. Batteries 2023, 9, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narale, S.B.; Verma, A.; Anand, S. Structure and Degradation of Aluminum Electrolytic Capacitors. In Proceedings of the 2019 National Power Electronics Conference, NPEC 2019, Tiruchirappalli, India, 13–15 December 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kohtz, S.; Zhao, J.; Renteria, A.; Lalwani, A.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Haran, K.S.; Senesky, D.; Wang, P. Optimal sensor placement for permanent magnet synchronous motor condition monitoring using a digital twin-assisted fault diagnosis approach. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 242, 109714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaleshtori, A.E.; Aghaie, A. A novel bearing fault diagnosis approach using the Gaussian mixture model and the weighted principal component analysis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 242, 109720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumanlidağ, D.; Keleş, D.; Oktay, G.; Koşay, C. Effects of vertebral fusion on levels of pro-inflammatory and catabolic mediators in a rabbit model of intervertebral disc degeneration. Acta Orthop. Traumatol. Turc. 2021, 55, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernizzi, L.; Paiardi, C.; Licata, G.; Vitali, T.; Santarelli, S.; Raneli, M.; Manelli, V.; Rizzetto, M.; Gioria, M.; Pasini, M.E.; et al. Glutamine Synthetase 1 Increases Autophagy Lysosomal Degradation of Mutant Huntingtin Aggregates in Neurons, Ameliorating Motility in a Drosophila Model for Huntington’s Disease. Cells 2020, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Yu, P.; Zhu, Y.; Dai, F.; Ma, Z.; Shen, X.; Jiang, H.; Liu, J. Role of Autophagy and Pyroptosis in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Yao, D.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Zeng, W.; Liao, Z.; Chen, E.; Lu, S.; Su, K.; Che, Z.; et al. TAK-715 alleviated IL-1β-induced apoptosis and ECM degradation in nucleus pulposus cells and attenuated intervertebral disc degeneration ex vivo and in vivo. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2023, 25, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.T.; Manuel, L. Uncertainty quantification in low-probability response estimation using sliced inverse regression and polynomial chaos expansion. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 242, 109750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Wang, Y.; Lampkin, S.; Prasad, S.G.; Zhupanska, O.; Davidson, B. Bond strength degradation of adhesive-bonded CFRP composite lap joints after lightning strike. In Proceedings of the 36th Technical Conference of the American Society for Composites 2021: Composites Ingenuity Taking on Challenges in Environment-Energy-Economy, College Station, TX, USA, 20–22 September 2021; Volume 1, pp. 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Amaya-Gómez, R.; Riascos-Ochoa, J.; Muñoz, F.; Bastidas-Arteaga, E.; Schoefs, F.; Sánchez-Silva, M. Modeling of pipeline corrosion degradation mechanism with a Lévy Process based on ILI (In-Line) inspections. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2019, 172, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.; Xie, X.; Lei, Y. Probability-Based Performance Degradation Model and Constitutive Model for the Buckling Behavior of Corroded Steel Bars. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, J. High Temperature Degradation Mechanism of Concrete with Plastering Layer. Materials 2022, 15, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nepal, J.; Chen, H.P.; Alani, A.M. Analytical modelling of bond strength degradation due to reinforcement corrosion. Key Eng. Mater. 2013, 569-570, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P.; Batool, M.; Godoy, A.O.; Singh, R.; Gerteisen, D.; Jankovic, J.; Zamel, N. Impact of Platinum Loading and Layer Thickness on Cathode Catalyst Degradation in PEM Fuel Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2023, 170, 024506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, C.S.; Biswas, G.; Koutsoukos, X. A prognosis case study for electrolytic capacitor degradation in DC–DC converters. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Prognostics and Health Management Society, San Diego, CA, USA, 27 September–1 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lin, C.; Yao, B.; Yang, L.; Ge, H. Intelligent fault diagnosis of rolling bearings with low-quality data: A feature significance and diversity learning method. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 237, 109343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, S.; Ma, L.; Mi, Z. Power transformer oil–paper insulation degradation modelling and prediction method based on functional principal component analysis. IET Sci. Meas. Technol. 2022, 16, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reniers, J.M.; Mulder, G.; Howey, D.A. Review and performance comparison of mechanical-chemical degradation models for lithium-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, A3189–A3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolai, M.; Zanuccoli, M.; Galiazzo, M.; Bertazzo, M.; Sangiorgi, E.; Fiegna, C. Simulation Study of Light-induced, Current-induced Degradation and Recovery on PERC Solar Cells. Energy Procedia 2016, 92, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho, M.; Carvalho, V.; Matos, M.; Fernandes, P.; Castro, A. Computational modeling of lumbar disc degeneration before and after spinal fusion. Clin. Biomech. 2021, 90, 105490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Gao, B.; Zhou, J.; Qiu, X.; Qiu, J.; Chen, T.; Liang, Y.; Gao, W.; Qiu, X.; Lin, Y. Constructing intervertebral disc degeneration animal model: A review of current models. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 1089244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewald, A.; Fuchs, A.; Boegelein, L.; Grunz, J.P.; Kneist, K.; Gbureck, U.; Hoelscher-Doht, S. Degradation and Bone-Contact Biocompatibility of Two Drillable Magnesium Phosphate Bone Cements in an In Vivo Rabbit Bone Defect Model. Materials 2023, 16, 4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Guo, Q.; Yu, J.; Xu, Y. Experimental research on the effect of microRNA-21 inhibitor on a rat model of intervertebral disc degeneration. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, G.; Liu, J.; Lan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Miao, J. Gut microbiota and intervertebral disc degeneration: A bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, K.; Sundar, I.K.; Gerloff, J.; Li, D.; Rahman, I. Lung cellular senescence is independent of aging in a mouse model of COPD/emphysema. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Li, S.; Wu, H.; Gao, R.; Rao, G.; Wang, D.; Chen, Z.; Ma, B.; Wang, H.; Sui, N.; et al. Parkin promotes proteasomal degradation of p62: Implication of selective vulnerability of neuronal cells in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Protein Cell 2016, 7, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Baraldi, P.; Zio, E. A method for fault detection in multi-component systems based on sparse autoencoder-based deep neural networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 220, 108278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, D.; Chiacchio, F.; Cavalieri, S.; Gambadoro, S.; Khodayee, S.M. Predictive maintenance of standalone steel industrial components powered by a dynamic reliability digital twin model with artificial intelligence. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 243, 109859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Su, Z.; Wang, D.; Pan, E. Joint maintenance and spare part ordering from multiple suppliers for multicomponent systems using a deep reinforcement learning algorithm. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 241, 109628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Peng, K.; Jin, Z. A Hybrid Method for Performance Degradation Probability Prediction of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell. Membranes 2023, 13, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabelski, J.; Karpiński, R.; Jonak, J.; Frigione, M. Adhesive Joint Degradation Due to Hardener-to-Epoxy Ratio Inaccuracy under Varying Curing and Thermal Operating Conditions. Materials 2022, 15, 7765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewmala, S.; Kamma, N.; Buakeaw, S.; Limphirat, W.; Nash, J.; Srilomsak, S.; Limthongkul, P.; Meethong, N. Impacts of Mg doping on the structural properties and degradation mechanisms of a Li and Mn rich layered oxide cathode for lithium-ion batteries. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, T.; Chen, Y.; Ying, K.; Jin, X.; Zhan, S. Deterioration mechanism of concrete under long-term elevated temperature in a metallurgic environment: A case study of the Baosteel company. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 14, e00503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, R.; Sawata, K.; Takanashi, R.; Sasaki, Y.; Sasaki, T. Degradation of shear performance of screwed joints caused by wood decay. J. Wood Sci. 2020, 66, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.C.; Ferguson, F.M.; Cai, Q.; Donovan, K.A.; Nandi, G.; Patnaik, D.; Zhang, T.; Huang, H.T.; Lucente, D.E.; Dickerson, B.C.; et al. Targeted degradation of aberrant tau in frontotemporal dementia patient-derived neuronal cell models. eLife 2019, 8, e45457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunsheng, S.; Jiaxiang, Z.; Mo, Y.; Erwei, S.; Jinguang, Z. Reconstruction of fiber Bragg grating strain profile used to monitor the stiffness degradation of the adhesive layer in carbon fiber-reinforced plastic single-lap joint. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2017, 9, 1687814016688575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Kim, N.H.; Choi, J.H. A robust health prediction using Bayesian approach guided by physical constraints. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 244, 109954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, B.; Singhal, A.; Kundu, S.; Ogle, J.P. Analyzing Distribution Transformer Degradation with Increased Power Electronic Loads. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Power and Energy Society Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 16–19 January 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Chen, J.; Quade, K.; Luder, D.; Gong, J.; Sauer, D.U. Battery degradation diagnosis with field data, impedance-based modeling and artificial intelligence. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 53, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Anurag, A.; Anand, S. Evaluation of Vce at inflection point for monitoring bond wire degradation in discrete packaged IGBTs. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 32, 2481–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffmacher, A.; Strahringer, D.; Malasani, S.; Wilde, J.; Kempiak, C.; Lindemann, A. In Situ Degradation Monitoring Methods during Lifetime Testing of Power Electronic Modules. In Proceedings of the Electronic Components and Technology Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 1 June–4 July 2021; Volume 2021, pp. 895–903. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, N.; Sánchez, L.; Anseán, D.; Dubarry, M. Li-ion battery degradation modes diagnosis via Convolutional Neural Networks. J. Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Jiang, L.; Yuan, J. Study of performance degradations in DC–DC converter due to hot carrier stress by simulation. Microelectron. Reliab. 2006, 46, 1840–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Hu, J.; Shao, H.; Hu, J. Federated multi-source domain adversarial adaptation framework for machinery fault diagnosis with data privacy. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 236, 109246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streb, M.; Ohrelius, M.; Siddiqui, A.; Klett, M.; Lindbergh, G. Diagnosis and prognosis of battery degradation through re-evaluation and Gaussian process regression of electrochemical model parameters. J. Power Sources 2023, 588, 233686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Masuda, A.; Marumoto, K.; Ohdaira, K. Mechanistic Understanding of Polarization-Type Potential-Induced Degradation in Crystalline-Silicon Photovoltaic Cell Modules. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2023, 4, 2200167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snuggs, J.W.; Day, R.E.; Bach, F.C.; Conner, M.T.; Bunning, R.A.D.; Tryfonidou, M.A.; Le Maitre, C.L. Aquaporin expression in the human and canine intervertebral disc during maturation and degeneration. JOR Spine 2019, 2, e1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Ríos, P.; Madero-Pérez, J.; Fernández, B.; Hilfiker, S. Targeting the autophagy/lysosomal degradation pathway in Parkinson’s disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016, 14, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala, P.; Vivar, R.; Montalva, R.; Olmos, P.; Meneses, M.; Borzone, G.R. Elastin degradation products in acute lung injury induced by gastric contents aspiration. Respir. Res. 2018, 19, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betancourt, D.; Baldion, P.; Castellanos, J. Resin-dentin bonding interface: Mechanisms of degradation and strategies for stabilization of the hybrid layer. Int. J. Biomater. 2019, 2019, 5268342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, C.; Yang, W.; Feng, P.; Peng, S.; Pan, H. Accelerated degradation of HAP/PLLA bone scaffold by PGA blending facilitates bioactivity and osteoconductivity. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badet, H.; Poineau, F. Corrosion studies of stainless steel 304 L in nitric acid in the presence of uranyl nitrate: Effect of temperature and nitric acid concentration. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Streb, M.; Siddiqui, A.; Klett, M.; Lindbergh, G.; Gudmundson, P. Layer-Resolved Mechanical Degradation of a Ni-Rich Positive Electrode. Batteries 2023, 9, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.S.; Kiran, B.; Sivagami, K.; Govindarajan, D.; Chakraborty, S. Thermal degradation model of used surgical masks based on machine learning methodology. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2023, 144, 104732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmau, A.; Richard, C.; Igual-Muñoz, A. Degradation mechanisms in martensitic stainless steels: Wear, corrosion and tribocorrosion appraisal. Tribol. Int. 2018, 121, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Deng, M.; Xuan, F.Z.; Liu, C.J. Experimental study of thermal degradation in ferritic CrNi alloy steel plates using nonlinear Lamb waves. NDT E Int. 2011, 44, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M.; Takahashi, J.; Yamamoto, T.; Uchida, M.; Tomita, Y. Multi-scale modeling of degradation behavior for crystalline polymer. Zairyo J. Soc. Mater. Sci. 2015, 64, 311–316. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Afsar Dizaj, E.; Kashani, M.M. Nonlinear structural performance and seismic fragility of corroded reinforced concrete structures: Modelling guidelines. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 5374–5403. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Kropka, J.M.; Adolf, D.B.; Spangler, S.; Austin, K.; Chambers, R.S. Mechanisms of degradation in adhesive joint strength: Glassy polymer thermoset bond in a humid environment. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2015, 63, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, J.; Wu, S.; Xie, J. The Mechanical Resistance of Asphalt Mixture with Steel Slag to Deformation and Skid Degradation Based on Laboratory Accelerated Heavy Loading Test. Materials 2022, 15, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Ding, C.; Wang, R.; Shen, C.; Huang, W.; Zhu, Z. Graph embedding deep broad learning system for data imbalance fault diagnosis of rotating machinery. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 240, 109601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wei, H.; Sun, Q. A novel sample selection approach based universal unsupervised domain adaptation for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 240, 109618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Shi, L.; Zhou, K.; Bai, G.; Wang, Z. Knowledge-informed deep networks for robust fault diagnosis of rolling bearings. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 244, 109863. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, Z.; Shu, X.; Xiao, R.; Shen, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Online surface temperature prediction and abnormal diagnosis of lithium-ion batteries based on hybrid neural network and fault threshold optimization. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 243, 109798. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, R.; Meng, Z.; Xu, Q.; Fan, F. Fractional Fourier and time domain recurrence plot fusion combining convolutional neural network for bearing fault diagnosis under variable working conditions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 232, 109076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhao, S.; Wang, H. A Digital Twin Based Estimation Method for Health Indicators of DC–DC Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 2105–2118. [Google Scholar]

- Erdinc, O.; Vural, B.; Uzunoglu, M. A dynamic lithium-ion battery model considering the effects of temperature and capacity fading. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Clean Electrical Power, Capri, Italy, 9–11 June 2009; pp. 383–386. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, M.S.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Choi, S.; Kwak, S.; Okilly, A.H.; Baek, J. A Fast Loss Model for Cascode GaN-FETs and Real-Time Degradation-Sensitive Control of Solid-State Transformers. Sensors 2023, 23, 4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathribail, P.S.; Vijayakumar, T. Comprehensive Study of MOSFET Degradation in Power Converters and Prognostic Failure Detection Using Physical Model. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. B 2023, 104, 305–317. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Ma, C.Q. Degradation of Polymer Solar Cells: Knowledge Learned from the Polymer:Fullerene Solar Cells. Energy Technol. 2021, 9, 2000920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Kwak, S.; Choi, S. Degradation-Sensitive Control Algorithm Based on Phase Optimization for Interleaved DC–DC Converters. Machines 2023, 11, 624. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Lee, J.; Jung, I.; Lee, Y. Online monitoring of power converter degradation using deep neural network. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.K.; Khan, F.H. Reliability analysis and performance degradation of a Boost converter. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition, Denver, CO, USA, 15–19 September 2013; pp. 5592–5597. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, K.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, E.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Y. An improved second-order kinetic model for degradation analysis of transformer paper insulation under non-uniform thermal field. High Volt. 2023, 8, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi, T.; Sudo, H.; Iwasaki, K.; Tsujimoto, T.; Ito, Y.M.; Iwasaki, N. In Vivo mouse intervertebral disc degeneration model based on a new histological classification. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanino, R.; Tsubata, Y.; Hotta, T.; Okimoto, T.; Amano, Y.; Takechi, M.; Tanaka, T.; Akita, T.; Nagase, M.; Yamashita, C.; et al. Characterization of a spontaneous mouse model of mild, accelerated aging via ECM degradation in emphysematous lungs. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gredic, M.; Karnati, S.; Ruppert, C.; Guenther, A.; Avdeev, S.N.; Kosanovic, D. Combined Pulmonary Fibrosis and Emphysema: When Scylla and Charybdis Ally. Cells 2023, 12, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.; Gansau, J.; Gullbrand, S.E.; Crowley, J.; Cunha, C.; Dudli, S.; Engiles, J.B.; Fusellier, M.; Goncalves, R.M.; Nakashima, D.; et al. Development of a standardized histopathology scoring system for intervertebral disc degeneration in rat models: An initiative of the ORS spine section. JOR Spine 2021, 4, e1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Wu, Z.; Li, L.; Cheng, S.; Chang, J. Genetic analysis of the causal relationship between gut microbiota and intervertebral disc degeneration: A two-sample Mendelian randomized study. Eur. Spine J. 2023, 33, 1986–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.H.; Do, D.H.; Miyazaki, M.; Wei, F.; Yoon, S.H.; Wang, J.C. Rabbit model for in vivo study of intervertebral disc degeneration and regeneration. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2008, 44, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, M.H.; Cho, D.H.; Baek, S.M.; Lee, J.W.; Park, J.H.; Yoo, C.M.; Shin, J.H.; Nam, H.G.; Son, H.G.; Lim, H.J.; et al. Spine-on-a-chip: Human annulus fibrosus degeneration model for simulating the severity of intervertebral disc degeneration. Biomicrofluidics 2017, 11, 064107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassner, A.; Waidelich, L.; Palkowski, H.; Wilde, J.; Mozaffari-Jovein, H. Tribocorrosion Mechanisms of Martensitic Stainless Steels; [Tribokorrosive Mechanismen martensitischer nichtrostender Stähle]. HTM J. Heat Treat. Mater. 2021, 76, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Boyer, A.; Ben Dhia, S. Analysis and modeling of passive device degradation for a long-term electromagnetic emission study of a DC-DC converter. Microelectron. Reliab. 2015, 55, 2061–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, L.; Badr, P.R.; Hoang, P.H.; Ozkan, G.; Papari, B.; Edrington, C.S. Battery Degradation in Electric and Hybrid Electric Vehicles: A Survey Study. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 42431–42462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Yuan, L.; Yin, A.; Zhou, J.; Song, L. A neural-driven stochastic degradation model for state-of-health estimation of lithium-ion battery. J. Energy Storage 2024, 79, 110248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, K.R.; Walter, B.A.; Laudier, D.M.; Krishnamoorthy, D.; Mosley, G.E.; Spiller, K.L.; Iatridis, J.C. Accumulation and localization of macrophage phenotypes with human intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine J. 2018, 18, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, S.; Zhang, G. Three-dimensional structured electrode for electrocatalytic organic wastewater purification: Design, mechanism and role. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 445. [Google Scholar]

- Eremina, G.; Smolin, A.; Xie, J.; Syrkashev, V. Development of a Computational Model of the Mechanical Behavior of the L4–L5 Lumbar Spine: Application to Disc Degeneration. Materials 2022, 15, 6684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.L.; Singh, I.N.; Wang, J.A.; Hall, E.D. Time courses of post-injury mitochondrial oxidative damage and respiratory dysfunction and neuronal cytoskeletal degradation in a rat model of focal traumatic brain injury. Neurochem. Int. 2017, 111, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Yang, S.; Ding, W. Intervertebral Disc Degeneration Induced by Needle Puncture and Ovariectomy: A Rat Coccygeal Model. BioMed Res. Int.l 2021, 2021, 5510124. [Google Scholar]

- Mashshay, A.F.; Hashemi, S.K.; Tavakoli, H. Post-Fire Mechanical Degradation of Lightweight Concretes and Maintenance Strategies with Steel Fibers and Nano-Silica. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglese, A.; Focareta, A.; Schindler, F.; Schön, J.; Lindroos, J.; Schubert, M.C.; Savin, H. Light-induced Degradation in Multicrystalline Silicon: The Role of Copper. Energy Procedia 2016, 92, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goushegir, S.M.; Scharnagl, N.; dos Santos, J.F.; Amancio-Filho, S.T. Durability of metal-composite friction spot joints under environmental conditions. Materials 2020, 13, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, M.; Elmasry, S.; Jackson, A.R.; Travascio, F. Computational Modeling Intervertebral Disc Pathophysiology: A Review. Front. Physiol. 2022, 12, 750668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preis, V.; Biedenbach, F. Assessing the incorporation of battery degradation in vehicle-to-grid optimization models. Energy Inform. 2023, 6, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Szczerska, M.; Kosowska, M.; Gierowski, J.; Cieślik, M.; Sawczak, M.; Jakóbczyk, P. Investigation of the Few-Layer Black Phosphorus Degradation by the Photonic Measurements. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 10, 2202289. [Google Scholar]

- Kareem, A.B.; Hur, J.W. Towards Data-Driven Fault Diagnostics Framework for SMPS-AEC Using Supervised Learning Algorithms. Electronics 2022, 11, 2492. [Google Scholar]

- Calciolari, E.; Ravanetti, F.; Strange, A.; Mardas, N.; Bozec, L.; Cacchioli, A.; Kostomitsopoulos, N.; Donos, N. Degradation pattern of a porcine collagen membrane in an in vivo model of guided bone regeneration. J. Periodontal Res. 2018, 53, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Hong, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Jeon, W.J.; Ha, I.H. IL-1β promotes disc degeneration and inflammation through direct injection of intervertebral disc in a rat lumbar disc herniation model. Spine J. 2021, 21, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunc, D.C.; Van Dijk, M.; Smit, T.; Higham, P.; Burger, E.; Wuisman, P. Three-year follow-up of bioabsorbable PLLA cages for lumbar interbody fusion: In vitro and in vivo degradation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2004, 553, 243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Wang, S.; Wen, P.; Zhao, S. Digital Twin for Degradation Parameters Identification of DC–DC Converters Based on Bayesian Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Prognostics and Health Management, Detroit, MI, USA, 7–9 June 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, Y.; Hori, N.; Kumagai, S. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy on the performance degradation of LiFePO4/graphite lithium-ion battery due to charge-discharge cycling under different c-rates. Energies 2019, 12, 4507. [Google Scholar]

- Sacramento, A.; Ramirez-Como, M.; Balderrama, V.S.; Garduno, S.I.; Estrada, M.; Marsal, L.F. Inverted Polymer Solar Cells Using Inkjet Printed ZnO as Electron Transport Layer: Characterization and Degradation Study. IEEE J. Electron Devices Soc. 2020, 8, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Galatioto, J.; Rao, S.; Ramirez, F.; Costa, K.D. Losartan Attenuates Degradation of Aorta and Lung Tissue Micromechanics in a Mouse Model of Severe Marfan Syndrome. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 44, 2994–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmounedi, N.; Bahloul, W.; Aoui, M.; Sahnoun, N.; Ellouz, Z.; Keskes, H. Original animal model of lumbar disc degeneration. Libyan J. Med. 2023, 18, 2212481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famouri, S.; Bagherian, A.; Shahmohammadi, A.; George, D.; Baghani, M.; Baniassadi, M. Refining anticipation of degraded bone microstructures during osteoporosis based on statistical homogenized reconstruction method via quality of connection function. Int. J. Comput. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 9, 2050023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wei, K.; Ding, Y.; Ahati, P.; Xu, H.; Fang, H.; Wang, H. M2a Macrophage-Secreted CHI3L1 Promotes Extracellular Matrix Metabolic Imbalances via Activation of IL-13Rα2/MAPK Pathway in Rat Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 666361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, C.K.; Hsiao, H.Y.; Tsai, Y.J.; Hsu, C.M.; Tu, Y.K. Influence of Simulated State of Disc Degeneration and Axial Stiffness of Coupler in a Hybrid Performance Stabilisation System on the Biomechanics of a Spine Segment Model. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, P.; de Wild, J.; Aninat, R.; Weber, T.; Vermang, B.; Schmitz, J.; Theelen, M. In-depth analysis of potential-induced degradation in a commercial CIGS PV module. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 2023, 31, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yit, T.W.; Hassan, R.; Zakaria, N.H.; Kasim, S.; Moi, S.H.; Khairuddin, A.R.; Amnur, H. Transformer in mRNA Degradation Prediction. Int. J. Inform. Vis. 2023, 7, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykal, H.H.; Neser, G. Synergistic Performance Degradation of Marine Structural Elements: Case Study of Polymer-Based Composite and Steel Hybrid Double Lap Joints. Pol. Marit. Res. 2023, 30, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Lu, T.; Deng, M. Bond Degradation Mechanism and Constitutive Relationship of Ribbed Steel Bars Embedded in Engineered Cementitious Composites under Cyclic Loading. Materials 2023, 16, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tao, L.; Li, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, L. A Two-State-Based Hybrid Model for Degradation and Capacity Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries with Capacity Recovery. Batteries 2023, 9, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.F.; Kaushik, B.; Rahmani, M.K.I.; Ahmed, M.E. Stacked Deep Dense Neural Network Model to Predict Alzheimer’s Dementia Using Audio Transcript Data. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 32750–32765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Zhu, P.; Zhang, L.; Yang, H. A novel rat tail disc degeneration model induced by static bending and compression. Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 2021, 4, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.W.; Liu, Y.J.; Li, X.N.; Han, M.M.; Yu, H.Y.; Hong, H.Y.; Zhang, L.F.; Xing, L.; Jiang, H.L. An Autologous Macrophage-Based Phenotypic Transformation-Collagen Degradation System Treating Advanced Liver Fibrosis. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2306899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Xu, Y.; Lu, S.; Gao, Y.; Deng, Y. Bone mesenchymal stem cell extracellular vesicles delivered miR let-7-5p alleviate endothelial glycocalyx degradation and leakage via targeting ABL2. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokeem, L.S.; Garcia, I.M.; Melo, M.A. Degradation and Failure Phenomena at the Dentin Bonding Interface. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, D.B.; Davies, B.J.V.; Scott, S.B.; Aguadero, A.; Ryan, M.P.; Stephens, I.E.L. Probing Degradation in Lithium Ion Batteries with On-Chip Electrochemistry Mass Spectrometry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202315357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Yi, Z.; Chen, B.R.; Tanim, T.R.; Dufek, E.J. Rapid failure mode classification and quantification in batteries: A deep learning modeling framework. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 45, 1002–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Application | Definitions from ISO Standards |

|---|---|

| Medicine | ISO 10993-13:2010—the standard outlines methods for identifying and quantifying degradation products from polymeric medical devices, focusing on chemical alterations of the finished device [11]. |

| ISO 10993-1:2018—the standard provides a framework for the biological evaluation of medical devices, including considerations for degradation and its impact on biocompatibility [12]. | |

| ISO 14971:2019—the standard addresses the application of risk management to medical devices, including risks associated with material degradation over time [13]. | |

| ISO 13485:2016—the standard specifies requirements for a quality management system where an organization needs to demonstrate its ability to provide medical devices that consistently meet customer and regulatory requirements, including those related to degradation [14]. | |

| Engineering | ISO 55000:2024—the standard provides an overview of asset management, including the management of degradation in engineering components to ensure reliability and performance [15]. |

| ISO 9001:2015—the standard outlines quality management principles that include monitoring and managing degradation in engineering processes and products [16]. | |

| ISO 14001:2015—the standard focuses on environmental management systems, which include considerations for material degradation and its environmental impacts [17]. | |

| ISO 50001:2018—the standard provides a framework for managing energy performance, which includes addressing degradation in materials and systems to improve energy efficiency [18]. | |

| Material Science | ISO 15156-1:2020—the standard provides guidelines for materials used in oil and gas production, addressing degradation mechanisms such as corrosion and their impact on material selection [19]. |

| ISO 6892-1:2019—the standard specifies the method for tensile testing of metallic materials, which includes considerations for degradation effects on mechanical properties [20]. | |

| ISO 11469:2016—the standard provides guidelines for the identification of plastics and their degradation characteristics, focusing on environmental impacts [21]. | |

| ISO 14040:2006—the standard outlines principles and a framework for life cycle assessment, which includes evaluating material degradation throughout the product life cycle [22]. |

| Ref. | Method | Application |

|---|---|---|

| [27] | regression analysis, Bayesian statistics | CNC machines |

| [28] | Markov Chain Monte Carlo, Bayesian statistics | machining tools |

| [33] | Markov Chain Monte Carlo, hidden Markov models | composite materials |

| [34] | supervised learning, deep learning | building materials |

| [35] | cluster analysis, regression analysis | industrial equipment |

| [36] | nonparametric Bayesian modeling of time series, Bayesian statistics | infrastructure systems such as bridges or highways |

| [29] | hidden Markov models, regression analysis | railway track geometry |

| [30] | Markov Chain Monte Carlo, Bayesian statistics | industrial machinery |

| [37] | Markov Chain Monte Carlo, supervised learning | brushless direct current motor |

| [38] | hidden Markov models, nonparametric Bayesian modeling of time series | machinery under different stressors |

| [39] | Markov Chain Monte Carlo, Bayesian statistics | metal components used in construction |

| [40] | hidden Markov models, nonparametric Bayesian modeling of time series | concrete structures |

| [31] | Bayesian statistics, regression analysis | structural components under stress |

| [32] | nonparametric Bayesian modeling of time series, Markov Chain Monte Carlo | modal properties of structural systems |

| [41] | Markov Chain Monte Carlo, Bayesian statistics | engineering assets and materials |

| Author | Ref. | Year | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firdaus, N., Ab-Samat, H., Prasetyo, B.T. | [4] | 2023 | defect detection model, Markovian model, machine learning-based predictive model |

| Jaime-Barquero, E., Bekaert, E., Olarte, J., Zulueta, E., Lopez-Guede, J.M. | [5] | 2023 | accelerated life testing model, physical-based model, machine learning-based model |

| Alimi, O.A., Meyer, E.L., Olayiwola, O.I. | [42] | 2022 | manual visual assessment model, condition monitoring model, statistical data analysis model |

| Berghout, T., Benbouzid, M. | [43] | 2022 | supervised learning model, unsupervised learning model, deep learning model |

| Zhao, S., Tayyebi, M., Mahdireza Yarigarravesh, Hu, G. | [44] | 2023 | mechanistic model, stochastic model, statistical model |

| Xue, K., Yang, J., Yang, M., Wang, D. | [45] | 2023 | machine learning model, statistical model, data-driven model |

| Papargyri, L., Theristis, M., Kubicek, B., Papanastasiou, P., Georghiou, G.E. | [6] | 2020 | statistical model, machine learning model, simulation model |

| Mondal, M., Kumbhar, G.B. | [46] | 2018 | neural network-based model, Monte Carlo simulation model, time series forecasting model |

| Zhang, M., Yang, S. | [47] | 2024 | support vector clustering model, deep learning model, statistical model |

| Chakurkar, P.S., Vora, D., Patil, S., Mishra, S., Kotecha, K. | [48] | 2023 | anomaly detection model, condition monitoring model, time-series analysis model |

| Method | Material Science | Engineering | Medicine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical inference | 25 | 41 | 34 |

| Dynamic prediction | 21 | 36 | 28 |

| Machine learning | 23 | 31 | 27 |

| Method | Material Science | Engineering | Medicine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Analysis | [82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91] | [92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107] | [108,109,110,111] |

| Factor Analysis | [112,113,114,115,116,117,118] | [119,120,121,122,123] | [124,125,126,127,128,129,130] |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo + probabilistic programming | [90,118,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140] | [103,120,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150] | [151,152,153,154,155] |

| Bayesian statistics | [87,115,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164] | [101,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178] | [108,125,126,128,179,180,181,182,183,184,185] |

| Method | Material Science | Engineering | Medicine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Markov models | [139,186] | [141,149,150,178,187,188,189] | [153,179,182,190,191,192,193,194] |

| Hidden Markov Models | [113,117,131,157,195,196,197] | [102,144,170,171,198,199,200,201] | [110,181,183,185,192,202,203,204] |

| Nonparametric Bayesian Time Series Modeling | [114,134,135,136,137,138] | [97,98,100,104,119,121,122,123,147,148,168,172,187,205,206,207] | [129,130,151,155,208,209,210,211,212] |

| Method | Material Science | Engineering | Medicine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | [82,84,85,86,132,140,159,196] | [95,96,99,106,174,199,201,213,214] | [127,180,184,204,208,210,211,215] |

| Deep Learning | [83,88,158,216] | [92,143,165,167,175,176,188,205,214,217] | [152,202,203,218] |

| Reinforcement Learning | [89,91,116,133,156,195] | [105,142,145,146,166,173,177,200] | [109,124,190,193,209,219,220,221,222] |

| Cluster analysis | [112,160,161,162,163,164,186,197,216] | [93,94,107,169,189,198,206,223,224] | [154,194,215,218,220,222] |

| Scenario | Typical Data Characteristics | Recommended Methods | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monotonic physical degradation (e.g., corrosion, crack growth, insulation aging) | Low- to medium-frequency measurements of a scalar damage indicator; strictly increasing or nearly monotonic trajectories; moderate sample size | Stochastic degradation processes (gamma, inverse Gaussian); parametric or Bayesian regression on time and covariates | Gamma/IG processes naturally represent cumulative monotonic damage and allow analytical RUL estimates; regression captures covariate effects on the degradation rate [3,54]. |

| Noisy, non-monotonic degradation with recovery effects | Dense or irregular time series; measurement noise and reversible effects (e.g., capacity recovery, load-dependent stiffness) | Wiener processes with drift; Gaussian process regression; state-space models | Drift–diffusion processes and GP regression model smooth but non-monotonic trajectories and provide uncertainty bands; state-space models separate latent degradation from measurement noise. |

| Abrupt regime changes or switching between health states | Time series or event sequences with sudden changes in behavior; latent operating modes; possibly sparse measurements | Markov models; Hidden Markov Models; switching state-space models | Markov and HMM frameworks explicitly represent transitions between discrete degradation states or regimes and are well suited for fault/health-state classification and prognosis. |

| High-dimensional sensor data (vibration, images, multichannel signals) | A large number of correlated features; possibly a high sampling rate; labels for health states or failures available for part of the data | Supervised machine learning (tree ensembles, SVMs, shallow ANNs); deep learning (CNNs, RNNs/LSTMs) for sufficiently large datasets | ML methods automatically extract nonlinear features from multivariate signals and achieve high predictive performance for health-state classification and RUL estimation, at the cost of interpretability and data requirements. |

| Small datasets with substantial uncertainty | Limited number of units or short time series; censored or missing observations; need for uncertainty quantification | Bayesian statistical models; hierarchical regression; stochastic degradation processes with Bayesian inference | Bayesian and hierarchical models can borrow strength across units, propagate parameter uncertainty, and provide credible intervals for degradation trajectories and RUL, which is crucial in high-reliability settings. |

| Complex operating conditions and multiple covariates | Multiple environmental and loading variables; mixture of continuous and categorical covariates; possible interactions | Generalized linear and additive models; mixed-effects models; hybrid physics–data models | These models flexibly incorporate covariates and random effects, capturing heterogeneity between units and linking physical understanding with data-driven components. |

| Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical inference | Regression analysis | Fast computation, Easily interpretable | Linear relationships, Strong assumptions |

| Factor analysis | Interpretability | Highest expert knowledge requirements | |

| MCMC & probabilistic programming | Specification of complicated models, | Mostly Bayesian applications, Computational costs | |

| Bayesian statistics | Most flexibility, interpretability | Computational problems, untraceablity of direct analytical formulas | |

| Dynamic prediction | Markov models | Widely understood, Good short term predictions | Limited long term accuracy |

| Hidden Markov models | Improved prediction quality, more flexibility | Difficult interpretability | |

| Bayesian time series | Ease of application (esp. Prophet), decomposition of effects | Computational costs | |

| Machine learning | Supervised learning | Flexibility, wide adoption | Difficult interpretability, large dataset requirements |

| Deep learning | Flexibility, predictive performance | High dataset requirements, no interpretability, computational costs | |

| Reinforcement learning | Very promising results | High dataset requirements, no interpretability, computational costs | |

| Cluster analysis | Limited expert knowledge required, detection of atypical cases | Data requirements, Problems with traceability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jarosz-Kozyro, A.; Baranowski, J. Recent Advances in Data-Driven Methods for Degradation Modeling Across Applications. Processes 2025, 13, 3962. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123962

Jarosz-Kozyro A, Baranowski J. Recent Advances in Data-Driven Methods for Degradation Modeling Across Applications. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3962. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123962

Chicago/Turabian StyleJarosz-Kozyro, Anna, and Jerzy Baranowski. 2025. "Recent Advances in Data-Driven Methods for Degradation Modeling Across Applications" Processes 13, no. 12: 3962. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123962

APA StyleJarosz-Kozyro, A., & Baranowski, J. (2025). Recent Advances in Data-Driven Methods for Degradation Modeling Across Applications. Processes, 13(12), 3962. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123962