A Sustainable Strategy for Co-Melting of Electroplating Sludge and Coal Gasification Slag: Metals Recovery and Vitrified Product Valorization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

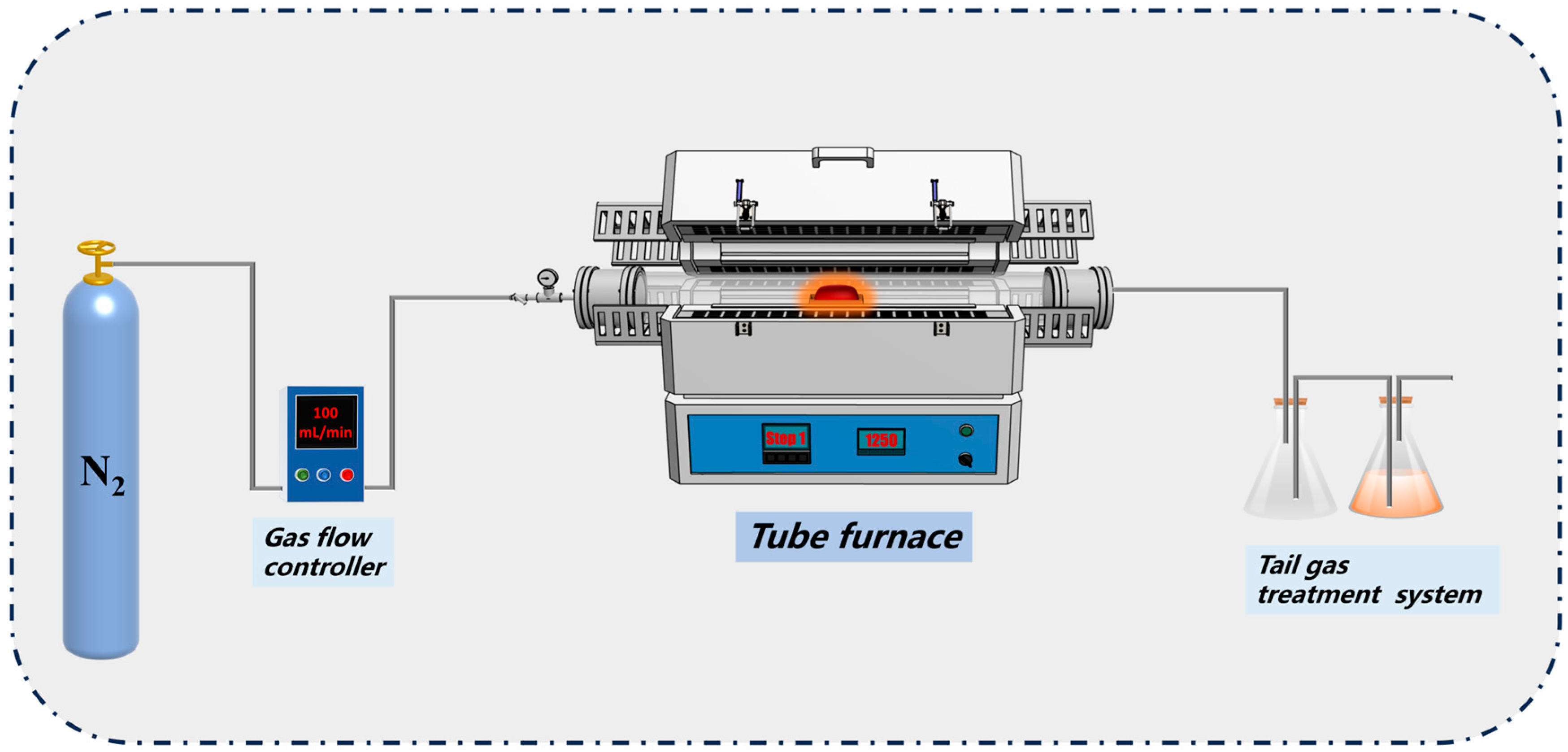

2.2. Co-Melting Experiment

2.3. Analysis and Characterization

2.4. Vitrified Product Heavy Metals Analysis

2.4.1. Leaching Toxicity Test

2.4.2. Environmental Risk Assessment

3. Results and Discussion

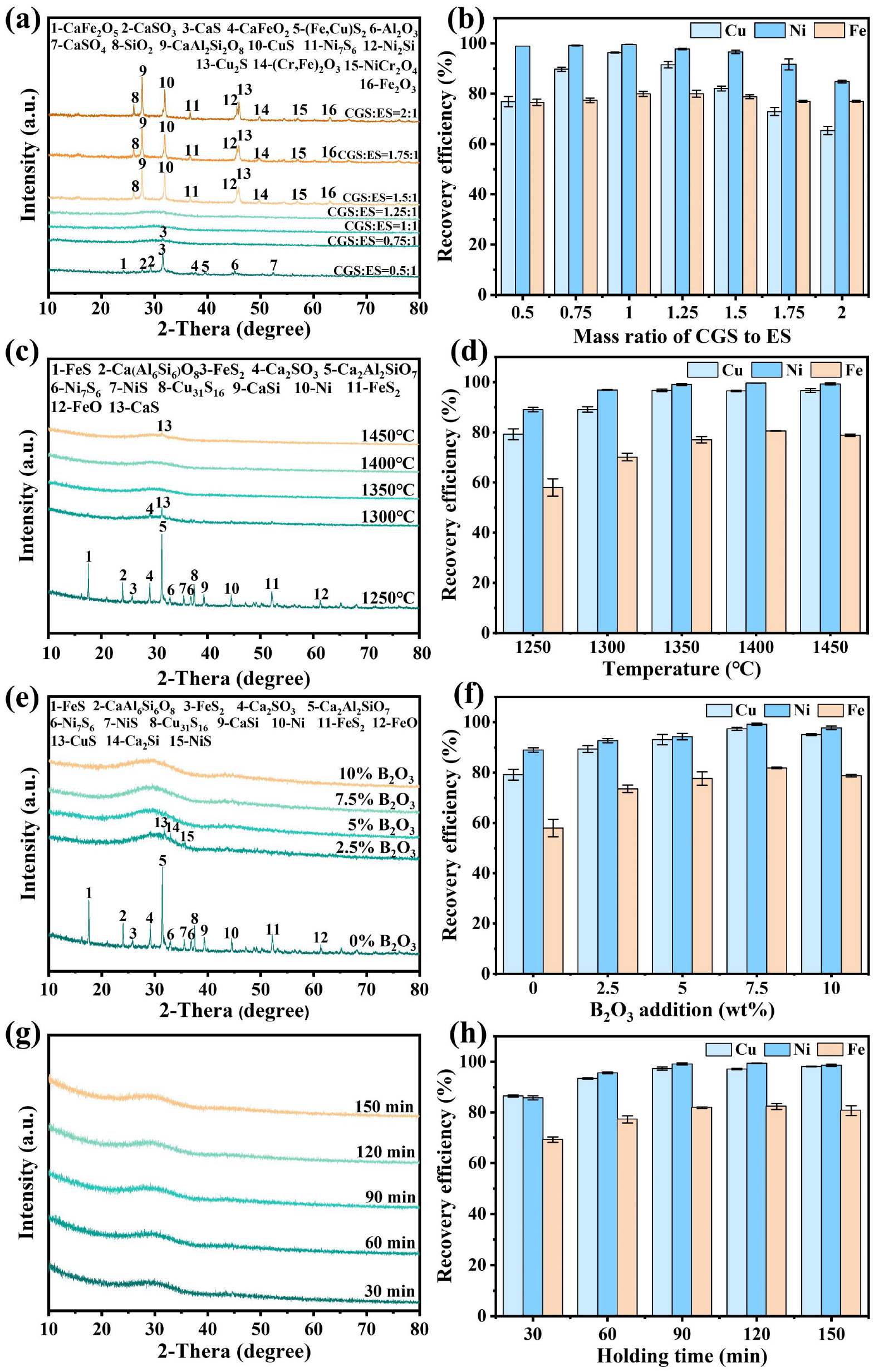

3.1. Phase Transformation and Metal Recovery

3.1.1. Effect of CGS to ES Mass Ratio

3.1.2. Effect of Smelting Temperature

3.1.3. Effect of B2O3 Addition

3.1.4. Effect of Holding Time

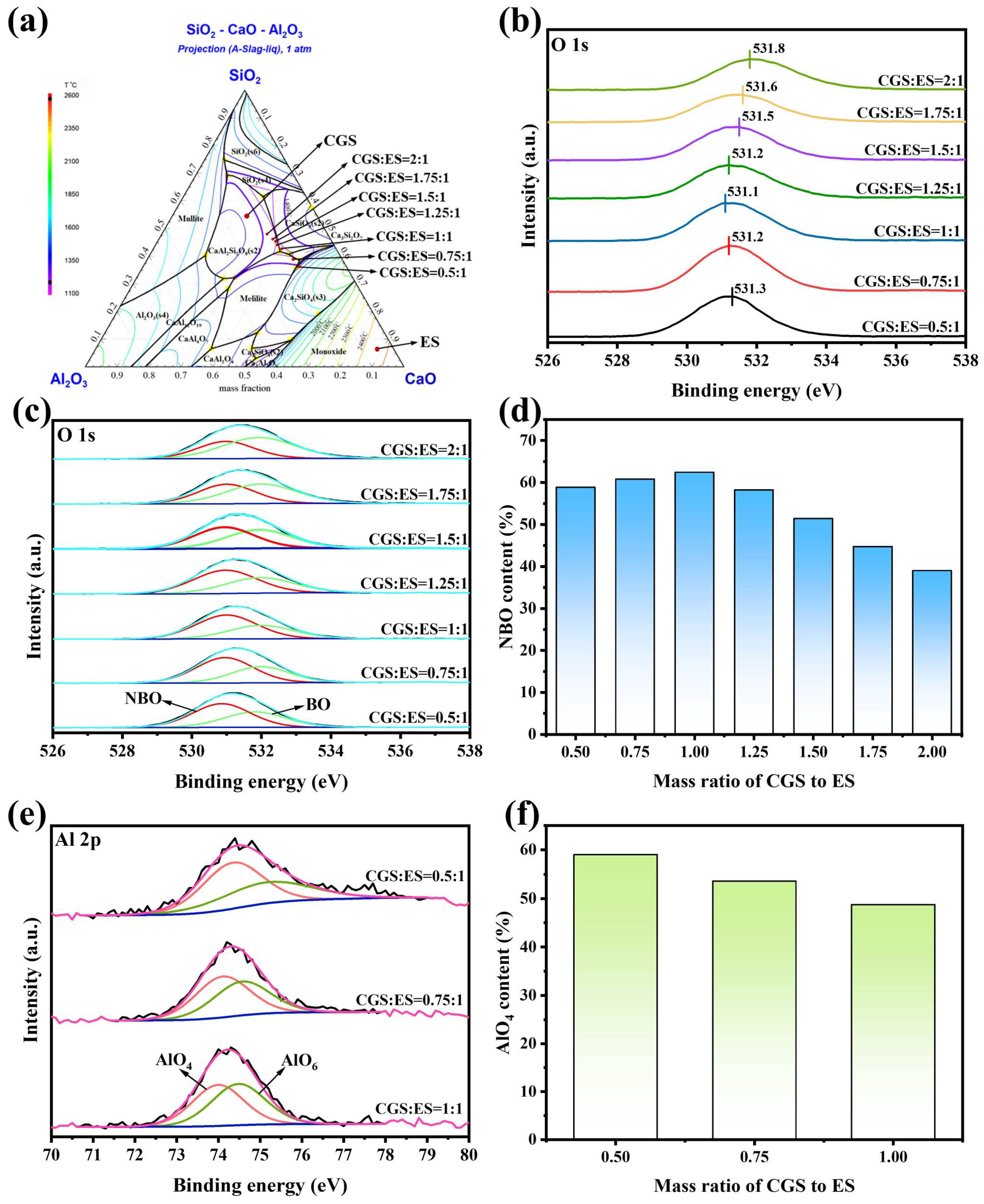

3.2. Synergistic Mechanism of Co-Melting

3.2.1. Activation of Potential Components in Silicate Network for Favorable Melt

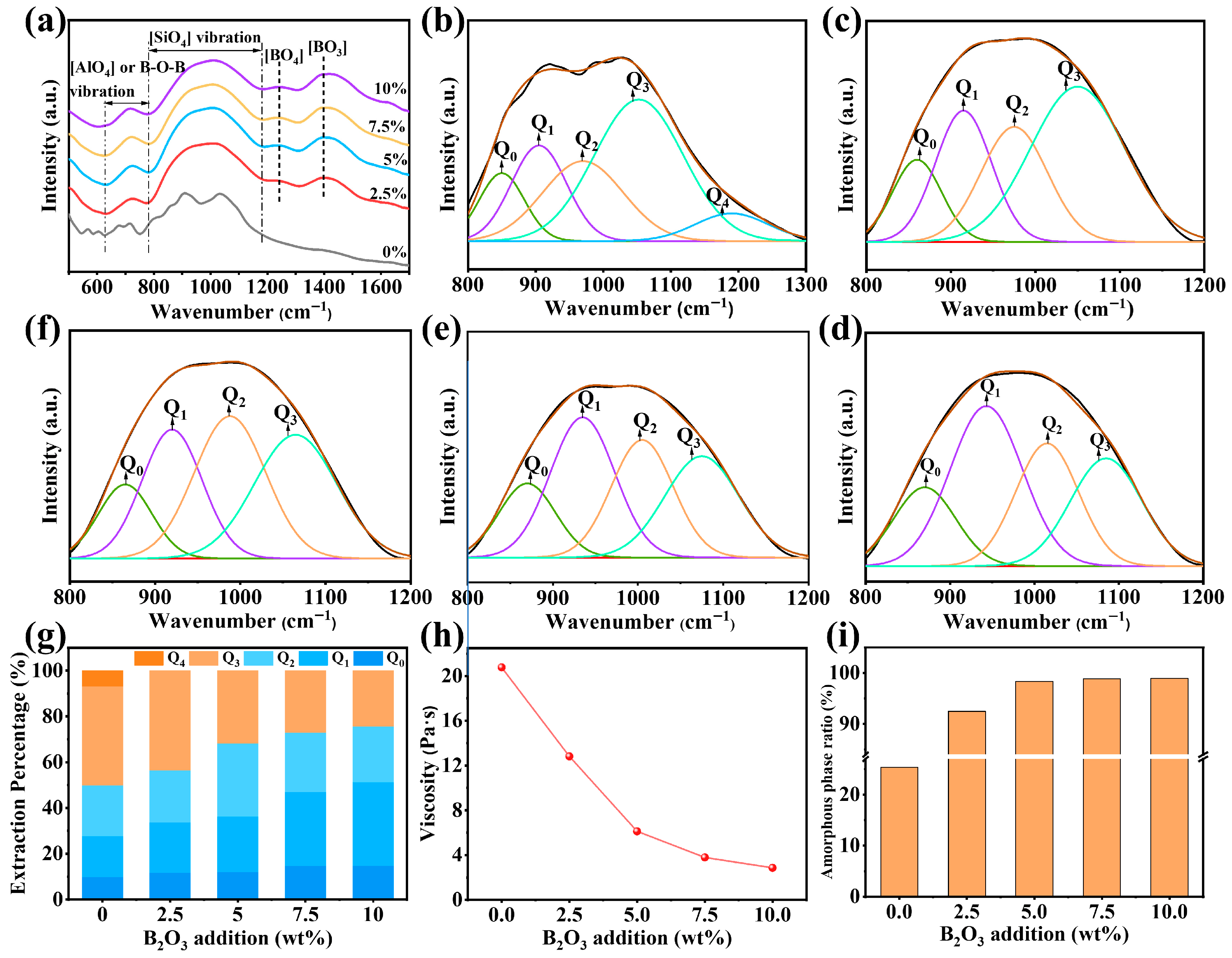

3.2.2. Positive Effects of B2O3 on Vitrification and Silicate Network Depolymerization

3.3. Mechanism of Metals Recovery as Alloy During Co-Melting

3.4. Harmless Vitrified Product Valorization

3.5. Implications

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- When ES and CGS were co-melted at a mass ratio of 1:1 with 7.5 wt% B2O3 at 1250 °C for 90 min, vitrification was achieved, and 97.3% Cu, 99.2% Ni, and 81.8% Fe were simultaneously recovered.

- (2)

- The synergistic mechanism of CaO, Al2O3, and B2O3 in the silicate network was investigated through characterization. Active species CaO, [AlO6], and [BO3] promoted the depolymerization of the complex Si-O network structure, thereby facilitating crystal phase melting and enhancing melt fluidity.

- (3)

- The co-melting of ES and CGS simultaneously reduced Cu, Ni, and Fe oxides to metals and sulfurized them into matte phases, both of which were subsequently incorporated into the alloy phase as a solid solution. Moreover, the favorable melting environment promoted efficient metal recovery.

- (4)

- Residual heavy metals such as Cu, Ni, Cr, and Zn in the vitrified product were effectively immobilized, and a high-performance glass-ceramic was prepared by heat-treating the vitrified product at 850 °C for 120 min.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, J.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, C.; Zhang, G.; Cao, Z.; Li, Q.; Wang, M.; Guan, W.; Wu, S. Complete Recycling of Valuable Metals from Electroplating Sludge: Green and Selective Recovery of Chromium. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 467, 143484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajoria, S.; Vashishtha, M.; Sangal, V.K. Treatment of Electroplating Industry Wastewater: A Review on the Various Techniques. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 72196–72246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, H.; Zhao, H.; Tang, J.; Gong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Gao, B. Immobilization of Hexavalent Chromium in Contaminated Soils Using Biochar Supported Nanoscale Iron Sulfide Composite. Chemosphere 2018, 194, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Ji, X.; Xu, X.; Xu, C.; Qi, X.; Wang, G.; Zhang, S.; Cai, J.; Lv, G.; Yang, Z.; et al. Sustainable and Selective Recovery of Copper from Electroplating Sludge via Choline Chloride-Citric Acid Deep Eutectic Solvent: Mechanistic Elucidation and Process Intensification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 376, 134195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Tang, R.; Zhou, H. Bioleaching of Copper-Containing Electroplating Sludge. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 285, 112133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Gong, X.; Wang, Z. Sustainable Electrochemical Recovery of High-Purity Cu Powders from Multi-Metal Acid Solution by a Centrifuge Electrode. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z. Approaches for Electroplating Sludge Treatment and Disposal Technology: Reduction, Pretreatment and Reuse. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 349, 119535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, F.; Manila, A.A.; Choi, A.E.S.; Lu, M.C. Electroplating Sludge Handling by Solidification/Stabilization Process: A Comprehensive Assessment Using Kaolinite Clay, Waste Latex Paint and Calcium Chloride Cement Additives. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manage. 2019, 21, 1505–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochem, L.F.; Casagrande, C.A.; Bizinotto, M.B.; Aponte, D.; Rocha, J.C. Study of the Solidification/Stabilization Process in a Mortar with Lightweight Aggregate or Recycled Aggregate. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 326, 129415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Fang, Z.; Qian, Y.; Huang, Z.; Ye, Y.; Yan, J. A Pilot-Scale Study and Evaluation of the Melting Process and Vitrification Characteristics of Electroplating Sludge by Oxygen Enrichment Melting. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 451, 142023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wei, G.; Liu, H.; Gong, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J. Comparative Study of Electroplating Sludge Reutilization in China: Environmental and Economic Performances. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 106598–106610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnemans, K.; Jones, P.T.; Manjón Fernández, Á.; Masaguer Torres, V. Hydrometallurgical Processes for the Recovery of Metals from Steel Industry By-Products: A Critical Review. J. Sustain. Metall. 2020, 6, 505–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanito, R.C.; Bernuy-Zumaeta, M.; You, S.-J.; Wang, Y.-F. A Review on Vitrification Technologies of Hazardous Waste. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 316, 115243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, X.; Yu, J.; Xu, C.; Wu, Y.; Pan, D.; Senthil, R.A. An Overview of the Comprehensive Utilization of Silicon-Based Solid Waste Related to PV Industry. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 169, 105450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, H.; Hu, J. Co-Treatment of Electroplating Sludge, Copper Slag, and Spent Cathode Carbon for Recovering and Solidifying Heavy Metals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 126020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Zhu, N.; Li, F.; Li, F.; Leng, W.; Xi, Y.; Wu, P.; Zhang, S. Preparation of Microcrystalline Glass by Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Fly Ash: Heavy Metals Crystallization Mechanism. Environ. Res. 2025, 277, 121567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Feng, D.; Bai, C.; Sun, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, F.; Chang, G.; Qin, Y. Thermal Synergistic Treatment of Municipal Solid Waste Incineration (MSWI) Fly Ash and Fluxing Agent in Specific Situation: Melting Characteristics, Leaching Characteristics of Heavy Metals. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 233, 107311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Shi, W.; Shi, Y.; Chen, D.; Liu, B.; Chu, C.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Chen, G. Plasma Vitrification and Heavy Metals Solidification of MSW and Sewage Sludge Incineration Fly Ash. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 408, 124809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurashima, K.; Matsuda, K.; Kumagai, S.; Kameda, T.; Saito, Y.; Yoshioka, T. A Combined Kinetic and Thermodynamic Approach for Interpreting the Complex Interactions during Chloride Volatilization of Heavy Metals in Municipal Solid Waste Fly Ash. Waste Manage. 2019, 87, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Ge, J.; Wu, Z.; Lin, J.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, Q.; Liu, X. One-Step Extraction of CuCl2 from Cu-Ni Mixed Electroplating Sludge by Chlorination-Mineralization Surface-Interface Phase Change Modulation. Surf. Interfaces 2023, 37, 102535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Tang, R.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Su, P.; Zhang, W. Stabilization of Electroplating Sludge with Iron Sludge by Thermal Treatment via Incorporating Heavy Metals into Spinel Phase. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, F.; Wu, S.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Qian, G. Heavy Metal Leaching and Distribution in Glass Products from the Co-Melting Treatment of Electroplating Sludge and MSWI Fly Ash. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 232, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Li, L.; Huang, M.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Xu, Z.; Lei, Y. Treating Waste with Waste: Metals Recovery from Electroplating Sludge Using Spent Cathode Carbon Combustion Dust and Copper Refining Slag. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 838, 156453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, L.; He, J.; Lei, Y. Waste Control by Waste: Metals Recovery from Electroplating Sludge via a Chlorination Roasting Followed by Silicothermic Reduction Using Solar-Grade Silicon Cutting Waste. Waste Manage. 2025, 194, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Y.; Li, Y.; Jiao, S.-Q.; Zhang, G.-H. Recovery of Cu-Fe-S Matte from Electroplating Sludge via the Sulfurization-Smelting Method. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, L.; Wen, G.; Liu, F.; Wang, F.; Barati, M. A Combined Computational-Experimental Study on the Effect of Na2O on the Fluoride Volatilization in Molten Slags. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 342, 117499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Li, F.; Li, X.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, N.; Wu, P.; Dang, Z. Volcanic Eruption-Inspired Co-Melting Treatment of Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Fly Ash. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 207, 107672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikfar, S.; Parsa, A.; Bahaloo-Horeh, N.; Mousavi, S.M. Enhanced Bioleaching of Cr and Ni from a Chromium-Rich Electroplating Sludge Using the Filtrated Culture of Aspergillus niger. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Tahir, M.H.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, J. Modification and Resource Utilization of Coal Gasification Slag-Based Material: A Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, K.; He, X.; Zhang, L. Overview of the Triple Attributes and Their Connections of Coal Gasification Slag in China: Resources, Materials, and Environment. Fuel 2025, 400, 135646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Xuan, W.; Cao, C.; Zhang, J. A Review of Sustainable Utilization and Prospect of Coal Gasification Slag. Environ. Res. 2023, 238, 117186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 18046-2017; Ground granulated blast furnace slag used for cement and concrete. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- HJ/T 299-2007; Solid Waste-Extraction Procedure for Leaching Toxicity-Sulfuric Acid & Nitric Acid Method. Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Nemati, K.; Bakar, N.K.A.; Abas, M.R.; Sobhanzadeh, E. Speciation of Heavy Metals by Modified BCR Sequential Extraction Procedure in Different Depths of Sediments from Sungai Buloh, Selangor, Malaysia. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 192, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Yao, W.; Li, R.; Ali, A.; Du, J.; Guo, D.; Xiao, R.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Awasthi, M.K. Effect of Pyrolysis Temperature on Chemical Form, Behavior and Environmental Risk of Zn, Pb and Cd in Biochar Produced from Phytoremediation Residue. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 249, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Huang, Y.; Pang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Cheng, H.; Gao, J.; Zuo, W.; Zhou, H. A Study of the Stabilization and Solidification of Heavy Metals in Co-Vitrification of Medical Waste Incineration Ash and Coal Fly Ash. Waste Manage. 2024, 186, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Sun, S.; Tu, G.; Xiao, F. Co-Treatment of Spent Automotive Catalyst and Cyanide Tailing via Vitrification and Smelting-Collection Process for Platinum Group Metals Recovery. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Dong, C.; Zhao, Y.; Xing, T.; Hu, X.; Wang, X. Effect of B2O3 on the Melting Characteristics of Model Municipal Solid Waste Incineration (MSWI) Fly Ash. Fuel 2021, 283, 119278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.; Li, B.; Wei, Y. A Novel Approach for the Recovery and Cyclic Utilization of Valuable Metals by Co-Smelting Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries with Copper Slag. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Gu, C.; Lyu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Bao, Y. The Effect of CaO/Al2O3 and SiO2 on the Structure and Properties of Rare Earth Bearing-Aluminosilicate System: A Molecular Dynamic Study. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 424, 127037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xu, W.; Qin, W.; Lei, J.; Dong, Z.; Liang, Y. Arsenic Removal from Copper Slag Matrix by High Temperature Sulfide-Reduction-Volatilization. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 415, 125642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Song, Q.; Xu, Z. Mechanism of PGMs Capture from Spent Automobile Catalyst by Copper from Waste Printed Circuit Boards with Simultaneous Pollutants Transformation. Waste Manage. 2024, 186, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, Z.; Huang, J.; Li, J.; Feng, H.; Wang, X.; Yin, X. Effect of F Content on the Structure, Viscosity and Dielectric Properties of SiO2-Al2O3-B2O3-RO-TiO2 Glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2021, 563, 120817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, H.; Dai, W.; Cang, D. Influence of Al2O3 Content on Microstructure and Properties of Different Binary Basicity Slag Glass Ceramics. Adv. Appl. Ceram. 2014, 113, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, M.; Baccaro, S.; Sharma, G.; Singh, D.; Thind, K.S.; Singh, D.P. Radiation Effects on PbO–Al2O3–B2O3–SiO2 Glasses by FTIR Spectroscopy. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2009, 267, 817–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, M.O. Bond Characterization in Cementitious Material Binders Using Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, M.; Wang, T.; Wei, C. Effect of B2O3 and Basic Oxides on Network Structure and Chemical Stability of Borosilicate Glass. Ceramics 2024, 7, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Mclean, A. Effects of Na2O Additions to Copper Slag on Iron Recovery and the Generation of Ceramics from the Non-Magnetic Residue. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 399, 122845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, Y.; Zhu, N.; Huang, J.; Li, X.; Shen, W.; Wu, P. Na2O Induced Stable Heavy Metal Silicates Phase Transformation and Glass Network Depolymerization. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 135009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Y.; Zhang, G.-H.; Chou, K.-C. Recovery of High-Grade Copper Matte by Selective Sulfurization of CuO-Fe2O3SiO2-CaO System. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 13, 1676–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Masters, I.; Das, A. In-Depth Evaluation of Laser-Welded Similar and Dissimilar Material Tab-to-Busbar Electrical Interconnects for Electric Vehicle Battery Pack. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 70, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Zhou, S.; Chen, J.; Zeng, X.; Han, Y.; Qin, J.; Huang, Y.; Lin, F.; Yu, X.; Liao, S.; et al. A Novel Method for Efficiently Recycling Platinum Group Metals and Copper by Co-Smelting Spent Automobile Catalysts with Waste-Printed Circuit Boards. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Shen, B.; Ma, J.; Liu, L. Preparation and Characterization of Fully Waste-Based Glass-Ceramics from Incineration Fly Ash, Waste Glass and Coal Fly Ash. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 21638–21647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tao, H.; Yu, Q.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Co-Gasification and Melting Behavior of Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Fly Ash and Rice Husk. Fuel 2025, 398, 135548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Guo, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, Y. Enhancing Waste Treatment: Co-Melting of MSWI Fly Ash and Biomass Ash for Lower Melting Point and Efficient Vitrification. J. Energy Inst. 2025, 120, 102102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Huang, Y.; Song, H.; Liu, H.; Shi, H.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, Y.; Kai, L. A Study on Heavy Metal Solidification and Migration in Co-Vitrification of Fly Ash and Furnace Bottom Ash from Hazardous Waste. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 119700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, I.-C.; Kuo, Y.-M.; Lin, C.; Wang, J.-W.; Wang, C.-T.; Chang-Chien, G.-P. Electroplating Sludge Metal Recovering with Vitrification Using Mineral Powder Additive. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 58, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Lou, B.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, S. Reduction of Iron from Red Mud with Aluminum Dross to Capture Heavy Metals from Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Fly Ash into Alloy. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Si | Al | Cu | Ni | Fe | Cr | Zn | C | S | O | Others | |

| ES | 21.39 | 0.97 | 1.05 | 4.70 | 7.43 | 4.08 | 0.51 | 0.63 | 4.05 | 3.80 | 41.51 | 9.88 |

| CGS | 13.24 | 19.88 | 9.13 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 8.76 | 0.28 | 0.05 | 5.59 | 0.18 | 39.61 | 3.07 |

| Index | Sample | Heavy Metal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | Ni | Fe | Cr | Zn | ||

| RAC | Raw sample (%) | 67.84 | 35.75 | 0.68 | 10.86 | 63.98 |

| Vitrified product (%) | ND | 7.52 | 2.87 | 5.46 | ND | |

| RI | Raw sample | 168.184 | ||||

| Vitrified product | 19.10 | |||||

| Category | Detail | Amount (kg) | Cost (USD/Ton) | Profit (USD) | Carbon Emission Factor (kg CO2/Ton) | Carbon Emission (kg CO2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource | ES | 500 | 200 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| CGS | 500 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| B2O3 | 75 | −300 | −22.5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Electricity | 400 kW h | −0.1 USD/kW h | −40 | 0.58 kg CO2/kW h | 232 | |

| Labor cost | Laborer | 2 | −5 USD | −10 | 2 kg CO2/human | 4 |

| Product | Glass ceramic | 710 | 50 | 35.5 | −7.76 | −5.51 |

| Alloy | 113 | 5000 | 565 | −1990 | −224.87 | |

| Profit | 633 | Carbon emission | 5.62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leng, W.; Zhu, N.; Li, F.; Wei, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Wu, P. A Sustainable Strategy for Co-Melting of Electroplating Sludge and Coal Gasification Slag: Metals Recovery and Vitrified Product Valorization. Processes 2025, 13, 3935. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123935

Leng W, Zhu N, Li F, Wei X, Zhang S, Li W, Wu P. A Sustainable Strategy for Co-Melting of Electroplating Sludge and Coal Gasification Slag: Metals Recovery and Vitrified Product Valorization. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3935. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123935

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeng, Wei, Nengwu Zhu, Fei Li, Xiaorong Wei, Sihai Zhang, Wanqi Li, and Pingxiao Wu. 2025. "A Sustainable Strategy for Co-Melting of Electroplating Sludge and Coal Gasification Slag: Metals Recovery and Vitrified Product Valorization" Processes 13, no. 12: 3935. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123935

APA StyleLeng, W., Zhu, N., Li, F., Wei, X., Zhang, S., Li, W., & Wu, P. (2025). A Sustainable Strategy for Co-Melting of Electroplating Sludge and Coal Gasification Slag: Metals Recovery and Vitrified Product Valorization. Processes, 13(12), 3935. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123935