1. Introduction

Mineral resources play a very important role in the world economy [

1]. Meanwhile, large-scale mining operations are prone to safety issues [

2]. As the depth and scale of metal mining continue to expand [

3], the surrounding rock of roadways is subjected to increasingly severe conditions including high in situ stress [

4], elevated temperatures, high water pressure, and mining-induced disturbances [

5]. These factors make roadway support operations paramount for ensuring underground safety production [

6]. The acceptance inspection of support quality is directly related to the stability of mining production and personnel safety, constituting an indispensable critical link in safety management [

7]. However, traditional support acceptance primarily relies on manual methods conducted through visual inspection, manual measurement, and sounding. This approach is not only inefficient but also highly susceptible to the complex underground environment and the subjective state of inspectors, leading to difficulties in guaranteeing the accuracy and consistency of acceptance results. As the scale of mining expands, the limitations of manual inspection become increasingly apparent, creating an urgent industry demand for the development of intelligent and automated support quality acceptance technologies.

Computer vision-based intelligent detection technology offers a viable solution to the aforementioned problems. However, the underground mine environment suffers from severely insufficient illumination [

8,

9]. Captured rock bolt images commonly exhibit issues such as low brightness, blurred details, and color distortion, which significantly constrain the performance of subsequent object detection algorithms. To overcome the bottleneck of low-light image quality, researchers have proposed various enhancement algorithms. Nevertheless, these methods still demonstrate notable limitations when dealing with the complex scenarios encountered underground [

10,

11]. That can be broadly categorized into three types:

(1) Physics-based and supervised learning methods, such as RetinexNet [

12,

13,

14] and its variants, which employ CNNs to decompose images into illumination and reflectance components based on Retinex theory [

15]. However, they are prone to color cast and detail blur under complex lighting conditions. RetinexFormer integrates Retinex priors with Transformers [

16,

17,

18], achieving excellent enhancement effects, but its high computational cost makes real-time deployment on underground edge devices challenging. Methods like LightenNet [

19] and KinD [

20], while reducing computational demands, heavily rely on synthetic data, leading to poor generalization in real underground scenarios and susceptibility to artifacts.

(2) Unsupervised learning and Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-based methods, such as EnlightenGAN [

21,

22], circumvent the need for paired data. However, their enhancement quality depends heavily on carefully designed prior loss functions, often resulting in under-enhancement, over-enhancement, or unstable outcomes in complex underground environments, thus exhibiting relatively poor reliability.

(3) Curve estimation and lightweight optimization-based methods, such as SCI [

23] and Zero-DCE [

24,

25], achieve rapid enhancement by estimating mapping curves but tend to lose details and introduce color distortion under extreme low-light or high-noise conditions. RUAS [

26] relies on handcrafted priors, limiting its generalization capability. Sparse-based methods are sensitive to noise and prone to artifacts. Approaches like NeRCO [

27] and DRBN [

28] lack stability under complex lighting, often causing local over-exposure or under-enhancement. URetinex-net [

29] faces real-time performance bottlenecks. General restoration models like Restormer [

30] and MIRNet [

31] are not well-adapted to low-light characteristics and involve substantial computational overhead. Although PromptIR [

32] shows progress in generalization and detail preservation, it still lacks specific optimization for underground low-light scenes.

In summary, existing methods struggle to achieve an effective balance between generalization capability and detail preservation, failing to fully meet the practical requirements for intelligent rock bolt detection in underground mines. Specifically, models relying on synthetic data or generic priors exhibit weak generalization in real underground environments, while those with strong detail reconstruction capabilities are often computationally complex or inadequately model low-light characteristics, making it difficult to stably retain fine rock rod features under complex illumination.

Given the practical needs of the mining industry, this study aims to design a low-light image enhancement algorithm specifically tailored for underground environments, capable of improving overall image quality while accurately preserving rock bolt details.

Low-light image enhancement algorithm has been applied to rock bolt detection in underground mines. To comprehensively evaluate the algorithm’s performance, we conducted not only traditional image quality assessment (using metrics such as PSNR and SSIM) and visual comparisons, but also designed a task-driven validation experiment based on the YOLOv8 object detection model. By comparing the mAP@0.5, Precision, and Recall metrics for bolt detection tasks on images before and after enhancement, we comprehensively demonstrate the effectiveness and practical value of our algorithm from an application perspective. The main contributions of this detection model can be summarized as follows:

(1) A Lighting Extraction Module based on the Retinex physical model is introduced, which computes illumination priors from the image and utilizes parallel convolutional layers to extract spatial features, explicitly decomposing an illumination map that characterizes the distribution of light. This mechanism provides a robust and physically meaningful illumination representation for subsequent processing.

(2) A Prompt Illumination Block is designed, which leverages illumination features as dynamic prompts to guide the model in adaptively focusing on global scene structures and local rock rod details, thereby achieving scene-aware image enhancement.

(3) A powerful sampling module is introduced, enhancing the feature extraction performance of the Transformer module. Down-sampling extracts multi-scale information, preserves global structure, and reduces noise; up-sampling balances global and local features, improving overall detail recovery.

4. Results

To rigorously evaluate the performance of the proposed PromptHDR algorithm, extensive experiments are conducted on the self-constructed Roadway Support Low-light Dataset. This section is organized into three parts: first, a qualitative visual comparison with state-of-the-art methods is provided to intuitively demonstrate the enhancement effects; second, quantitative results using PSNR and SSIM metrics are presented for objective performance comparison; finally, ablation studies are detailed to validate the contribution of each core component within the PromptHDR architecture.

4.1. Qualitative Results

A qualitative comparison between the proposed PromptHDR algorithm and other low-light enhancement methods is presented in

Figure 3. When visually compared against high-quality reference images acquired with artificial lighting, it is observed that on the roadway low-light image dataset: the enhanced results from EnlightenGAN and KinD exhibit issues with dark color tones; Zero-DCE suffers from significant noise amplification; URetinex-Net demonstrates severe color distortion; and although PromptIR shows some improvement in details, it still falls short of the reference image in terms of overall brightness and color naturalness. In contrast, the proposed PromptHDR algorithm most closely approximates the reference image in color fidelity, brightness uniformity, and edge sharpness, achieving the best visual enhancement performance.

Figure 4 further displays the enhancement results of the PromptHDR algorithm on the roadway low-light dataset. Through direct comparison with the original low-light images and their corresponding reference images, it can be intuitively observed that the enhanced results exhibit excellent performance in color fidelity, noise suppression, and control of color distortion. This further confirms the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm in restoring the authentic visual attributes of the images.

A comparative analysis in both 2D and 3D HSV color space was conducted on normal-light, low-light, and enhanced images of the same scene, with results shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. The enhanced image distribution exhibits minimal differences from the normal-light image distribution, with a significant improvement in the V-channel while maintaining structural consistency in the H and S distributions. This validates the effectiveness of the enhancement method in brightness recovery and color restoration.

4.2. Quantitative Results

To ensure fair and reproducible comparisons, all competing methods were evaluated under identical conditions. For approaches that provide publicly available pre-trained models (including EnlightenGAN, KinD, URetinex-net, Restormer, PromptIR, and MIRNet), the official pre-trained weights are used in this study. For methods without available pre-trained models (such as SCI, Zero-DCE, Sparse, RUAS, NeRCO, and DRBN), models are re-trained on our roadway support low-light dataset training set until convergence. By comparing the proposed method against other excellent supervised/unsupervised low-light enhancement methods on the same test set, the quantitative results—including PSNR, SSIM, and additionally introduced perceptual metrics (NIQE, LPIPS, BRISQUE)—are presented in

Table 2. The experimental results demonstrate that the PromptHDR algorithm achieves competitive performance across multiple evaluation metrics, with particularly outstanding performance in terms of PSNR and SSIM metrics.

As can be clearly observed from the quantitative results in

Table 2, the proposed PromptHDR algorithm comprehensively surpasses existing advanced methods in terms of image reconstruction quality. In the PSNR metric, PromptHDR achieved the highest score of 24.19 dB, demonstrating a slight yet consistent lead over the next best performers, MIRNet (24.14 dB) and PromptIR (23.62 dB), while realizing substantial performance gains compared to traditional methods such as SCI (14.78 dB) and Zero-DCE (16.76 dB). Regarding the SSIM metric, which measures structural similarity, PromptHDR also ranked first with the highest score of 0.839, outperforming not only MIRNet (0.830) and PromptIR (0.832) but also surpassing URetinex-net (0.835) and DRBN (0.834) by a significant margin.

On no-reference image quality assessment metrics, PromptHDR likewise exhibited performance. For the NIQE index, PromptHDR achieved the lowest value of 0.70, significantly outperforming URetinex-net (0.75), MIRNet (0.76), and PromptIR (0.78), indicating that its enhancement results are closer to high-quality images in terms of naturalness and visual comfort. In the perceptual similarity metric LPIPS, PromptHDR led with the lowest error score of 0.2384, compared to MIRNet (0.2536) and PromptIR (0.2718), revealing its advantage in preserving image semantic content and perceptual quality. Furthermore, for the blind image quality assessment metric BRISQUE, PromptHDR achieved the lowest score of 16.59, markedly superior to URetinex-net (17.83) and MIRNet (18.92), further validating its effectiveness in suppressing noise and artifacts while enhancing overall visual quality. These results demonstrate that PromptHDR not only improves the signal-to-noise ratio of images but also more effectively preserves structural information, achieving state-of-the-art performance in both pixel-level fidelity and perceptual structural similarity.

To further evaluate the practical utility of the proposed method, the model complexity and computational efficiency of PromptHDR are compared against other competing methods. All experiments were conducted under the same hardware environment (see

Table 3), with a uniform input image resolution of 128 × 128. Number of parameters (Params) and floating-point operations (GFLOPs) are used to measure model complexity, and used frames processed per second (FPS) as the indicator for runtime efficiency.

4.3. Ablation Study

To rigorously evaluate the contribution of each core component within the complex PromptHDR architecture, a comprehensive ablation study was conducted. Eight variant models are structured by incrementally removing or adjusting the key proposed modules—namely the Lighting Extraction Module (LEM), the Sampling Module (comprising HWD and DySample), and the Mamba-based Prompt Block. All variants were trained and evaluated on the same Roadway Support Low-light Dataset under identical settings. The quantitative results, summarized in

Table 4, unequivocally demonstrate the necessity and effectiveness of each component, with the complete PromptHDR model achieving the highest performance.

The quantitative results in

Table 4 provide compelling evidence for the contribution of each module. The baseline model (Architecture 1), which lacks all three proposed components, serves as a reference point. The performance increment observed in Architectures 2, 3, and 4 reveals the individual impact of the LEM, Sampling, and Prompt modules, respectively. For instance, the introduction of the Lighting Extraction Module (Architecture 2) alone brought a notable gain in PSNR, underscoring its role in mitigating color distortion by providing explicit illumination priors. The Sampling Module (Architecture 3) contributed the most significant single-module performance jump, highlighting its critical function in multi-scale feature fusion for detail preservation. The incorporation of the Prompt Block (Architecture 4) also provided a clear benefit, validating its ability to guide the enhancement process using illumination features.

More importantly, the combinations of these modules (Architectures 5–7) show that their effects are complementary. The synergy is most potent in the full model (Architecture 8), which integrates all components and achieves the peak performance (PSNR: 24.19, SSIM: 0.839). The fact that no incomplete architecture could match the full model’s performance strongly suggests that each module addresses a distinct and critical aspect of the low-light enhancement challenge underground—illumination non-uniformity, detail loss at different scales, and context-aware feature refinement—and that their co-design is essential for optimal results.

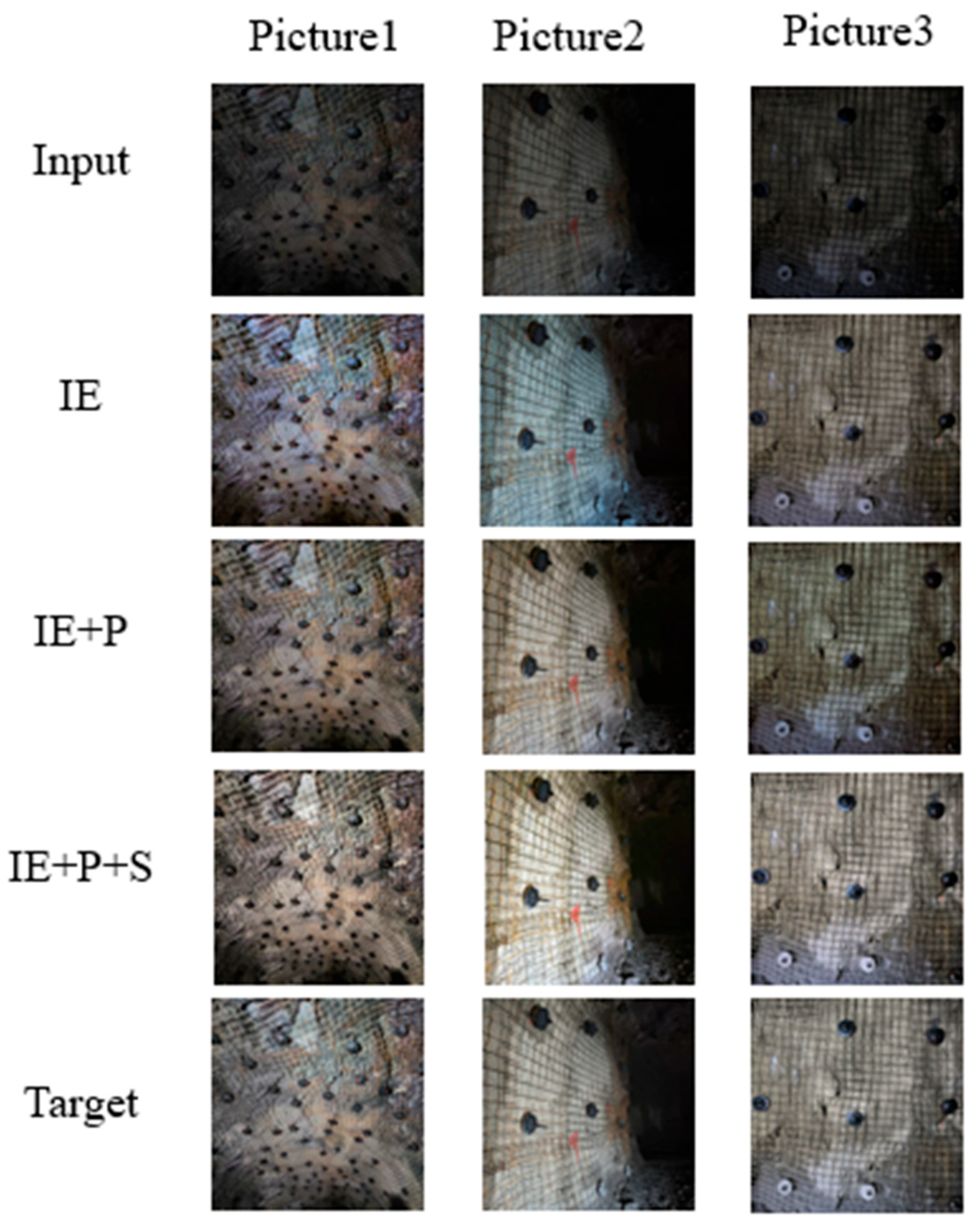

The visual comparisons in

Figure 7 provide an intuitive understanding of how each module progressively refines the output. The variant employing only the Lighting Extraction Module (Architecture 2) establishes a baseline with improved color uniformity, yet it still exhibits blurred details and insufficient local contrast around rock bolt features. Subsequently, the introduction of the Mamba-based Prompt Block (Architecture 6) leads to a perceptible recovery of finer textures and edges, as the model adaptively focuses on critical local details guided by the illumination features. Ultimately, the complete PromptHDR model (Architecture 8), which integrates the Sampling Module, produces the most visually pleasing result by successfully balancing global brightness with local sharpness. This final output clearly reveals rock bolt structures (e.g., nuts and washers) while maintaining natural color rendition and suppressing noise. The observed progressive visual improvement aligns with the quantitative metrics and solidifies the claim that each module is indispensable for achieving the final high-quality enhancement.

An internal ablation study on the Sampling Module itself further justifies its design. As quantified in

Table 5, using only HWD downsampling or only DySample upsampling results in a performance drop compared to their joint use. This empirically confirms that the two components form a cohesive unit: effective downsampling is crucial for creating a multi-scale feature hierarchy and reducing computational burden, while high-fidelity upsampling is equally critical for reconstructing a high-resolution output with preserved details. Their combination is fundamental to the success of the U-shaped network in our task.

4.4. Bolt Detection Performance Evaluation

The aforementioned ablation studies have verified the effectiveness of the core components internally. However, the ultimate value of our work lies in its improvement of practical application tasks. Therefore, we next proceed to the downstream bolt detection experiment to form a complete chain of reasoning from methodology to application.

We employed the high-performing and widely adopted YOLOv8 model as the benchmark detector. The specific experimental settings are as follows.

4.4.1. Dataset and Evaluation Metrics

To ensure the acquisition of authentic and undistorted visual features of bolts in the detection model, a detection dataset was constructed using 400 original normal-illumination images with corresponding bolt annotations. Data augmentation was deliberately avoided to maintain precise correspondence between bounding boxes and image content, as well as to preserve the authenticity of illumination conditions. The dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and test sets following an 8:1:1 ratio for training a YOLOv8m model with adequate bolt recognition capability. The training procedure extended over 300 epochs with input images resized to 640 × 640 pixels, resulting in a stable and converged model. Detailed system configurations employed during training are provided in

Table 1.

Core evaluation metrics in object detection were documented as comprehensive indicators for algorithm performance assessment, including Precision, Recall, and mean Average Precision (mAP). Precision quantifies the prediction accuracy of detected instances, while Recall measures the model’s coverage capability of true positive cases, representing the proportion of correctly identified positives among all actual positives. The mean Average Precision (mAP), calculated as the macro-average of Average Precision (AP) across all categories, serves as a crucial benchmark for model evaluation—higher mAP values indicate superior overall detection accuracy.

where N represents the total number of all categories; TP denotes the number of correctly predicted positive samples; FP indicates the number of negative samples incorrectly predicted as positive; and FN refers to the number of positive samples incorrectly predicted as negative.

4.4.2. Comparative Experimental Results and Analysis

To focus on the most representative comparisons and clearly present the core differences in task performance, the pre-trained YOLOv8 model weights were held fixed during the evaluation, and a set of five key conditions was established for performance recording. These include original low-light images (serving as the performance lower-bound baseline), normal-light images (serving as the performance upper-bound reference), along with test set images enhanced by two high-performing mainstream algorithms, KinD and PromptIR, respectively, and finally, those enhanced by the proposed PromptHDR method. This setup forms a comprehensive and efficient evaluation framework, spanning from baseline and competitor methods to our proposed approach. The quantitative results of the downstream task validation are presented in

Table 6.

As shown in

Table 6, compared to the various evaluation metrics obtained from the original low-light images, all image enhancement methods, when used as a preprocessing step, improve bolt detection performance to varying degrees. This confirms the necessity of image enhancement in low-light environments. Furthermore, among all the compared algorithms, the proposed PromptHDR algorithm achieves dominantly superior performance, with an mAP of 87.97%, while maintaining the highest precision and a competitive recall rate. Compared to the second-best performer, PromptIR, PromptHDR achieves an absolute improvement of 5.4% in mAP, fully demonstrating that the visual features restored by PromptHDR-enhanced images are more aligned with the requirements of the target detection model. Finally, it is noteworthy that the detection performance on low-light images processed by PromptHDR most closely approaches the performance upper bound obtained directly on ideal normal-light images (in terms of mAP). This indicates that our method effectively bridges the gap between low-light conditions and ideal visual perception.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the challenges of low illumination, detail blur, and color distortion in rock bolt images captured in dark underground mining environments by proposing PromptHDR, a low-light image enhancement algorithm based on the Transformer architecture. The algorithm employs a lighting extraction module to explicitly model illumination distribution, effectively suppressing color distortion caused by non-uniform lighting; introduces a prompt module that integrates Mamba with illumination features to enhance the model’s contextual understanding of tunnel scenes and its ability to preserve bolt details; and constructs a sampling module comprising DySample and HWD components to achieve high-quality image reconstruction through multi-scale feature fusion. Experiments on a real-world underground tunnel low-light dataset demonstrate that PromptHDR achieves PSNR and SSIM values of 24.19 dB and 0.839, respectively, outperforming several mainstream methods and exhibiting superior visual enhancement effects.

Validation experiments based on YOLOv8 demonstrate that images enhanced by PromptHDR attain a bolt detection mAP of 87.97%, while maintaining the highest precision and a competitive recall rate, significantly outperforming all compared methods. This successfully establishes a complete, closed-loop argument from ‘image quality enhancement’ to ‘detection performance improvement,’ thereby providing compelling evidence for the algorithm’s practical value in the intelligent construction of mines

Although PromptHDR performs well in low-light image enhancement, it still has certain limitations when dealing with the complex and variable real-world underground conditions. In environments filled with dust and haze, light undergoes spatially varying degradation patterns due to multiple scattering and absorption, leading to decreased overall image contrast and increased noise. As the current model does not explicitly model such physical degradation processes, the enhancement effectiveness might be constrained. Furthermore, the algorithm is relatively sensitive to motion blur caused by equipment vibration or movement, lacking explicit modeling and compensation mechanisms for motion blur, which could affect the accurate identification of bolt structures in dynamic scenarios.

Looking forward, we will proceed with our research from the following aspects: On the one hand, we will explore integrated optimization frameworks that combine dehazing, deblurring, and low-light enhancement to improve the model’s robustness and generalization in scenarios with composite degradations. On the other hand, we will focus on the lightweight design and engineering optimization of the algorithm, promoting its integration into embedded platforms and inspection robotic systems. This aims to achieve real-time and reliable visual enhancement in underground low-light environments, ultimately serving the goals of intelligent mine construction and safe, efficient production.