Multiscale Pore Structure and Heterogeneity of Deep Medium-Rank Coals in the Eastern Ordos Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting and Experiments Methods

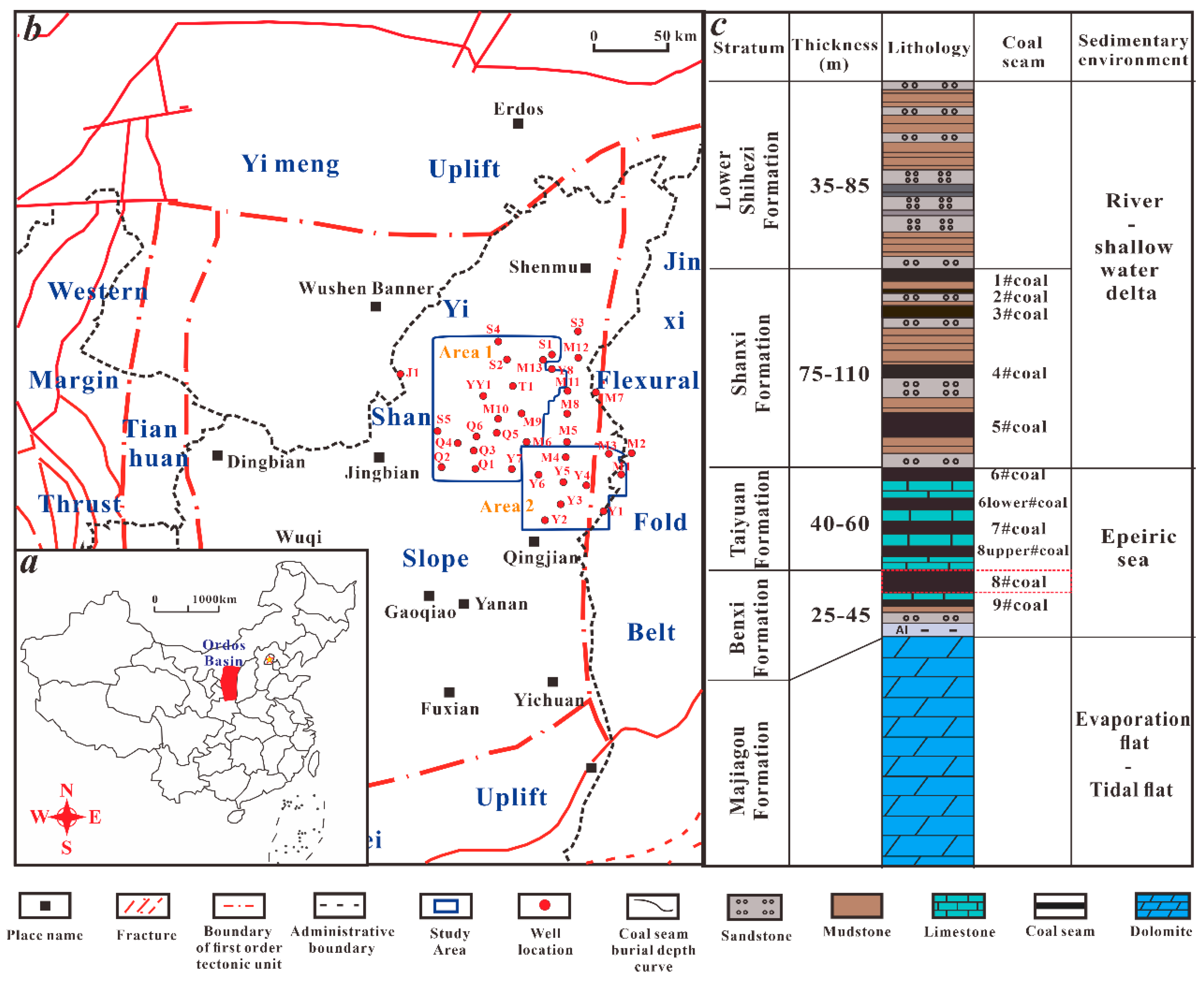

2.1. Geological Setting

2.2. Experimental Methods

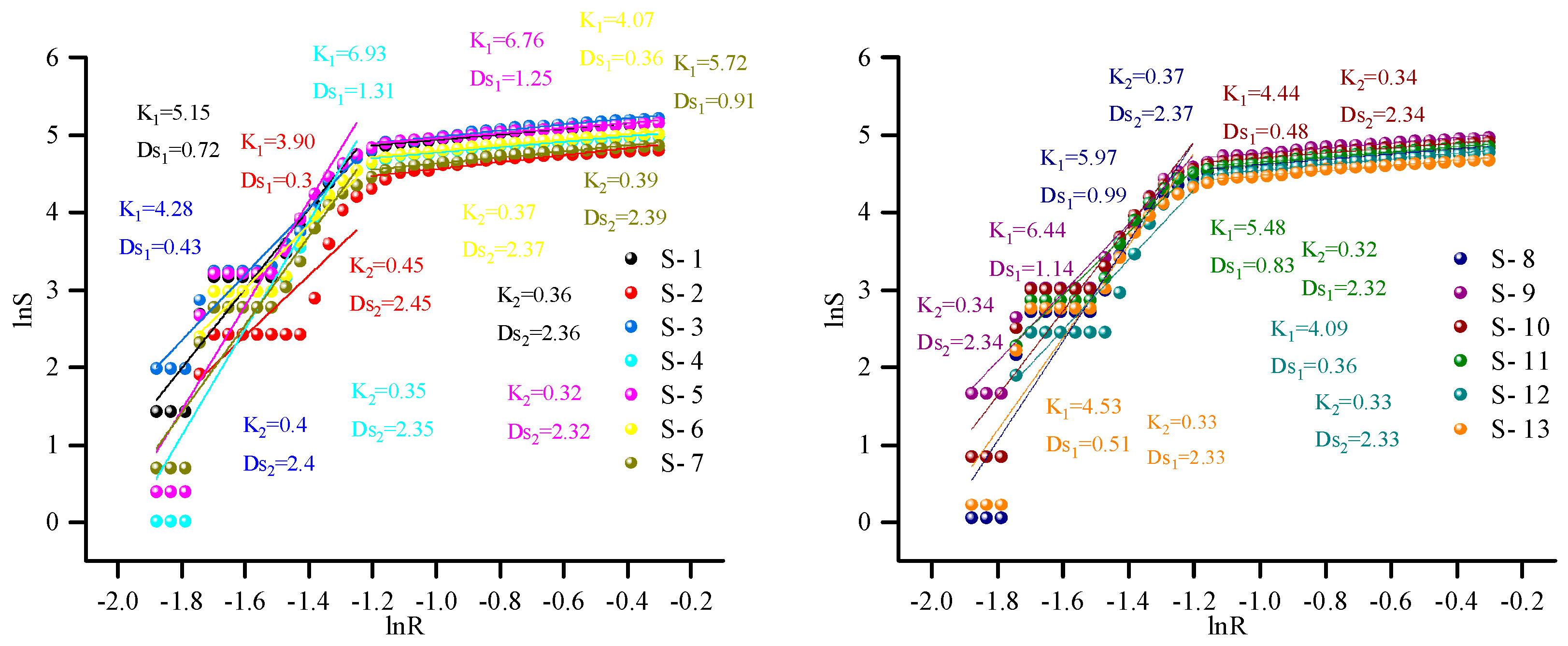

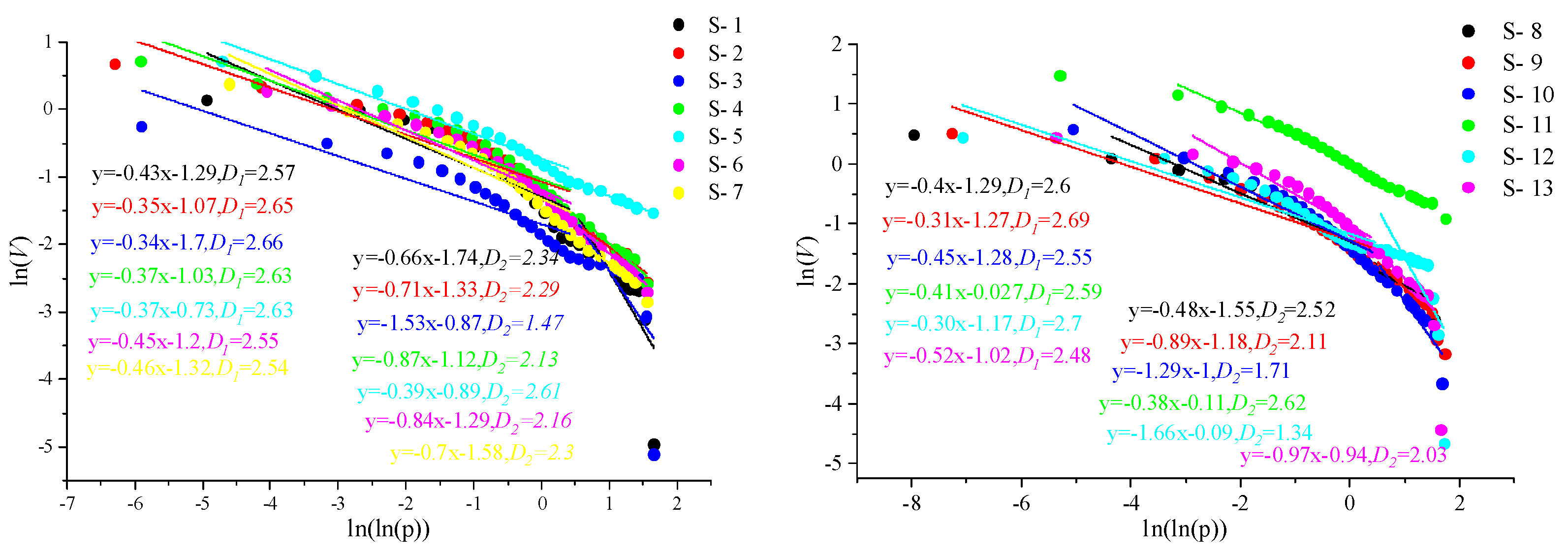

2.3. Fractal Theories

3. Results and Discussion

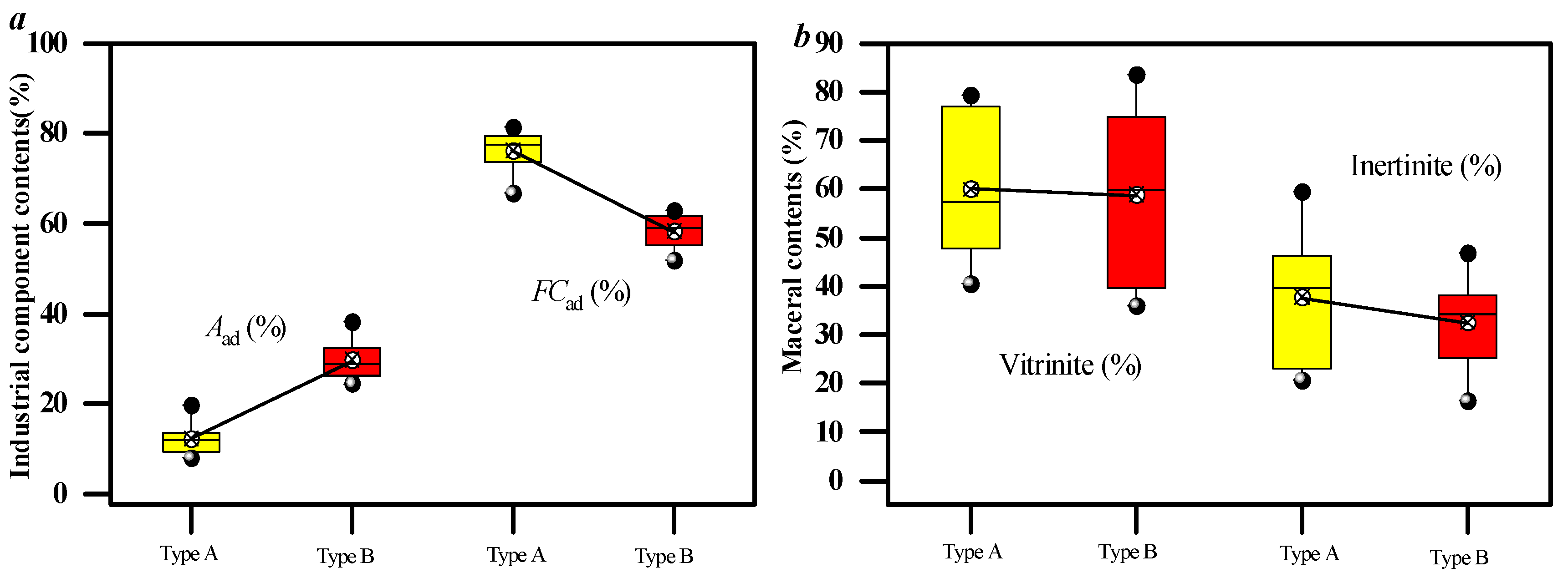

3.1. Basic Geological Characteristics

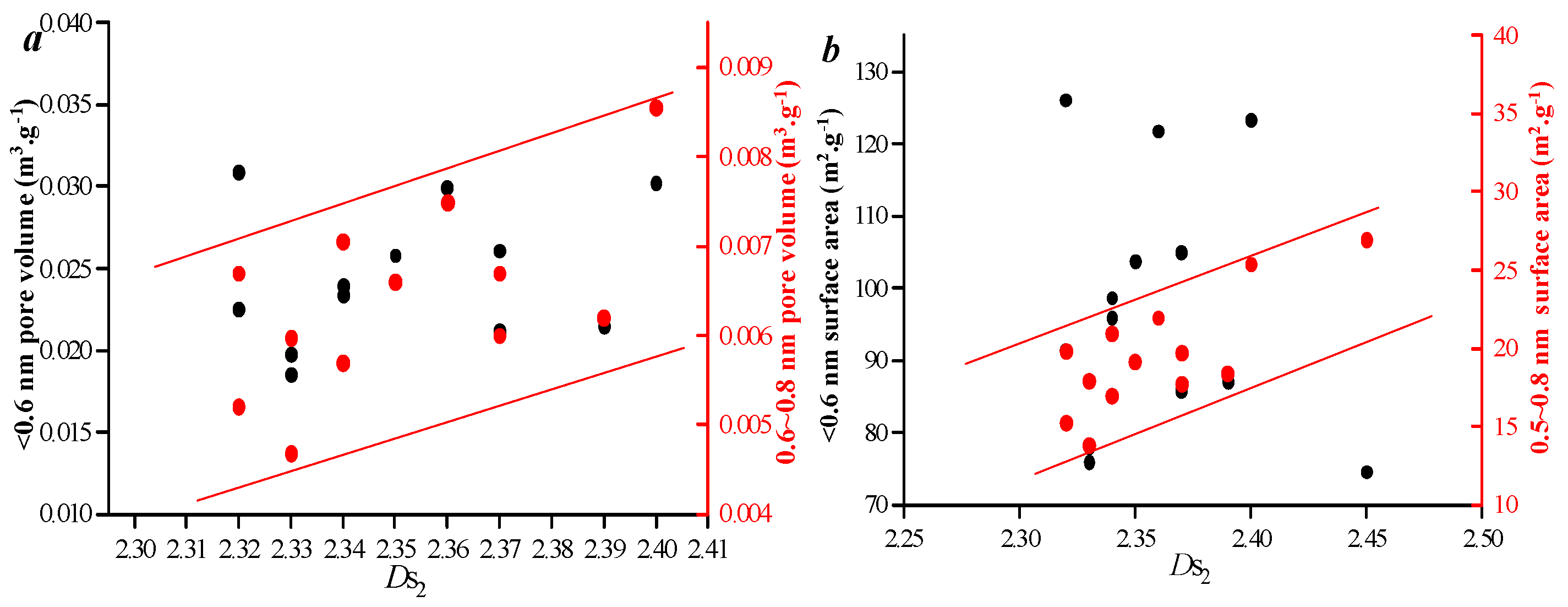

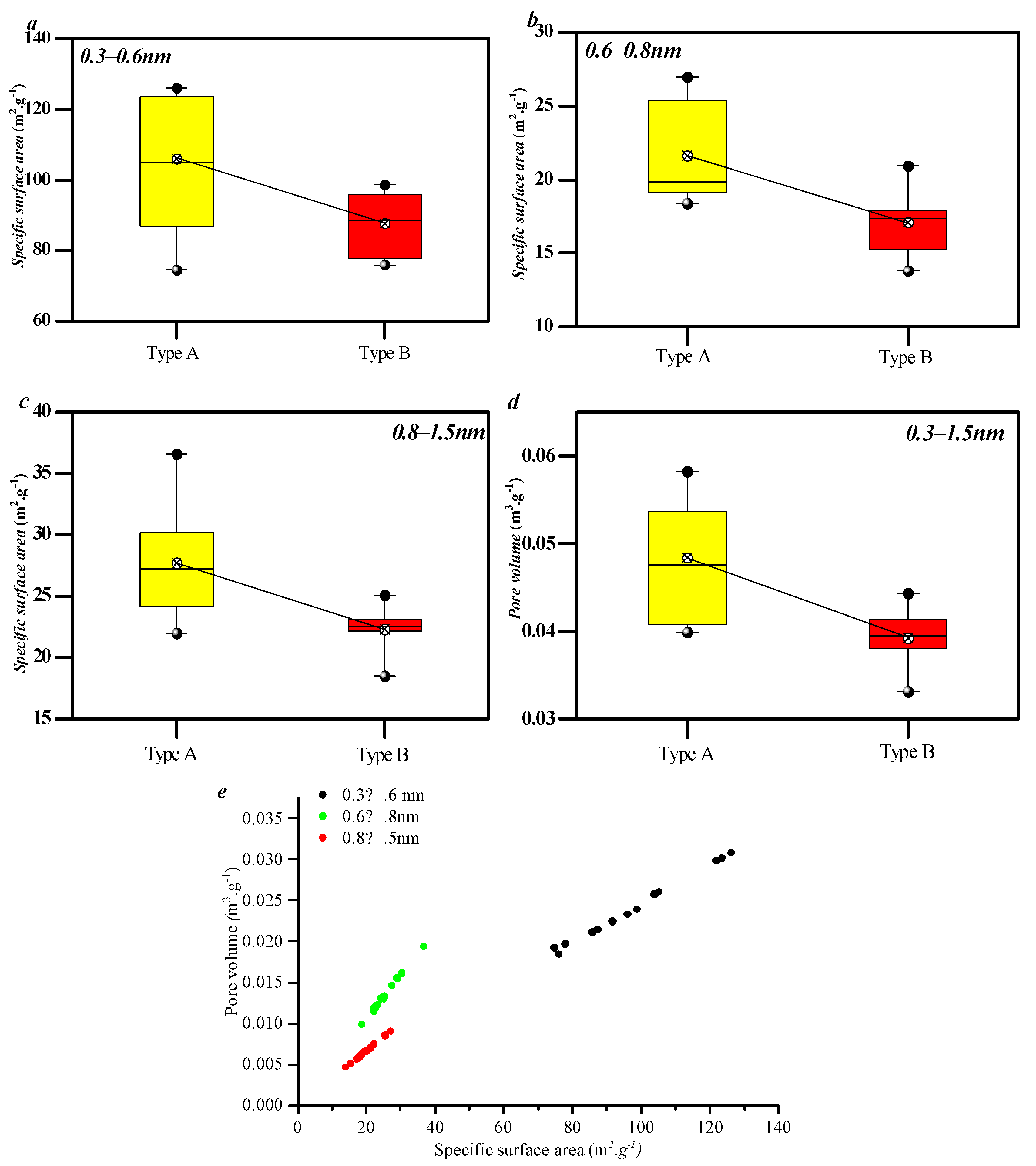

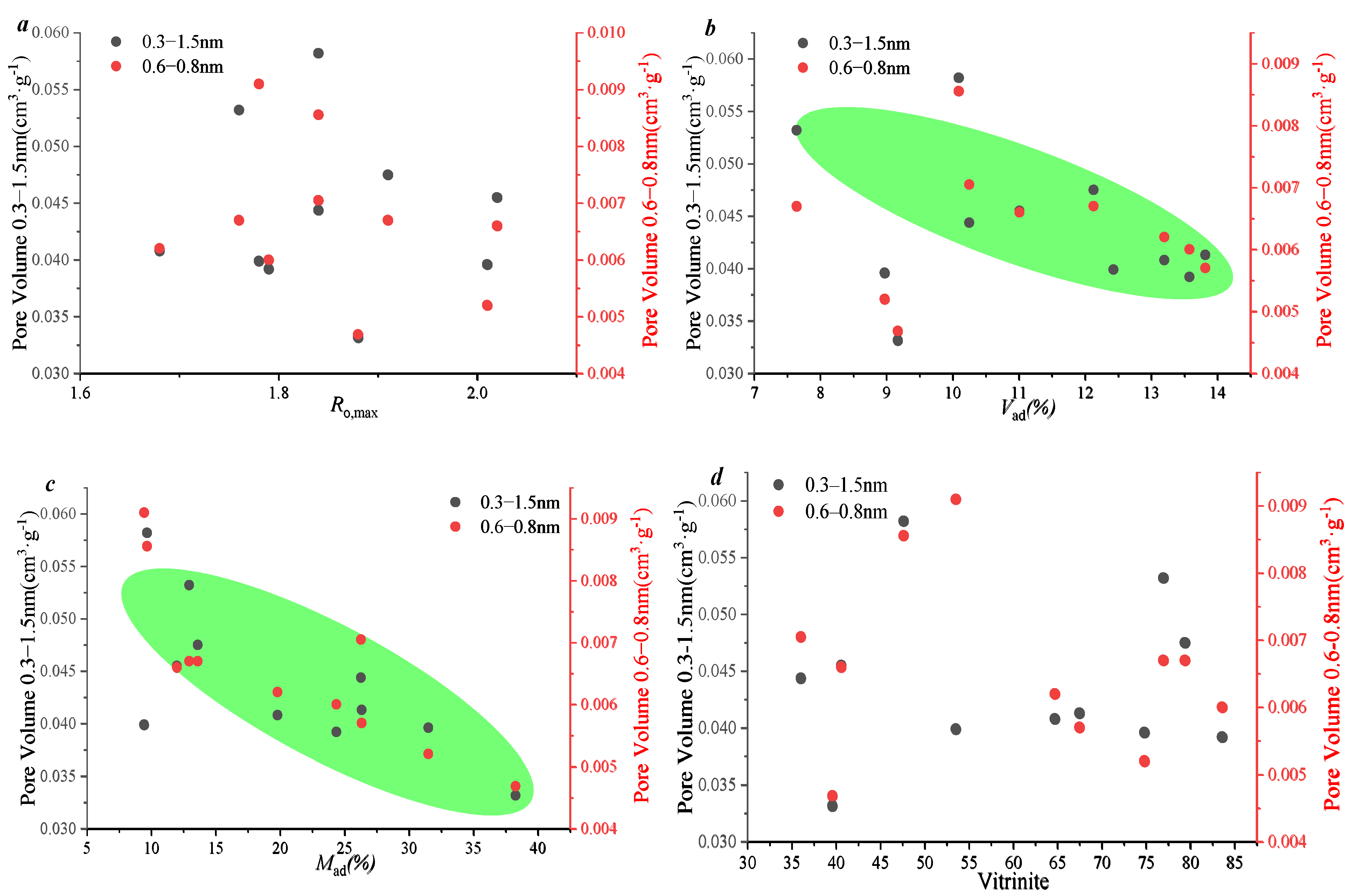

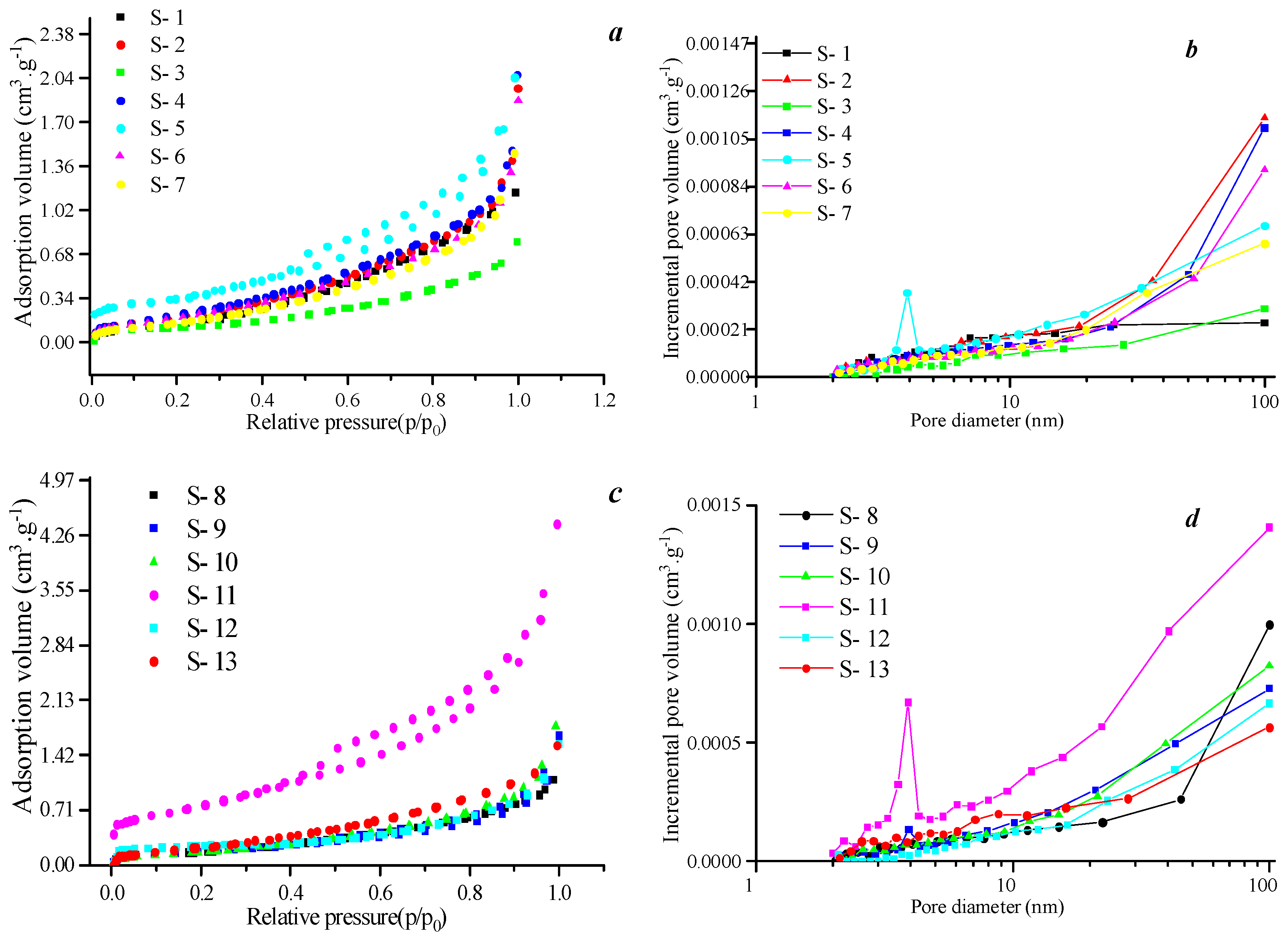

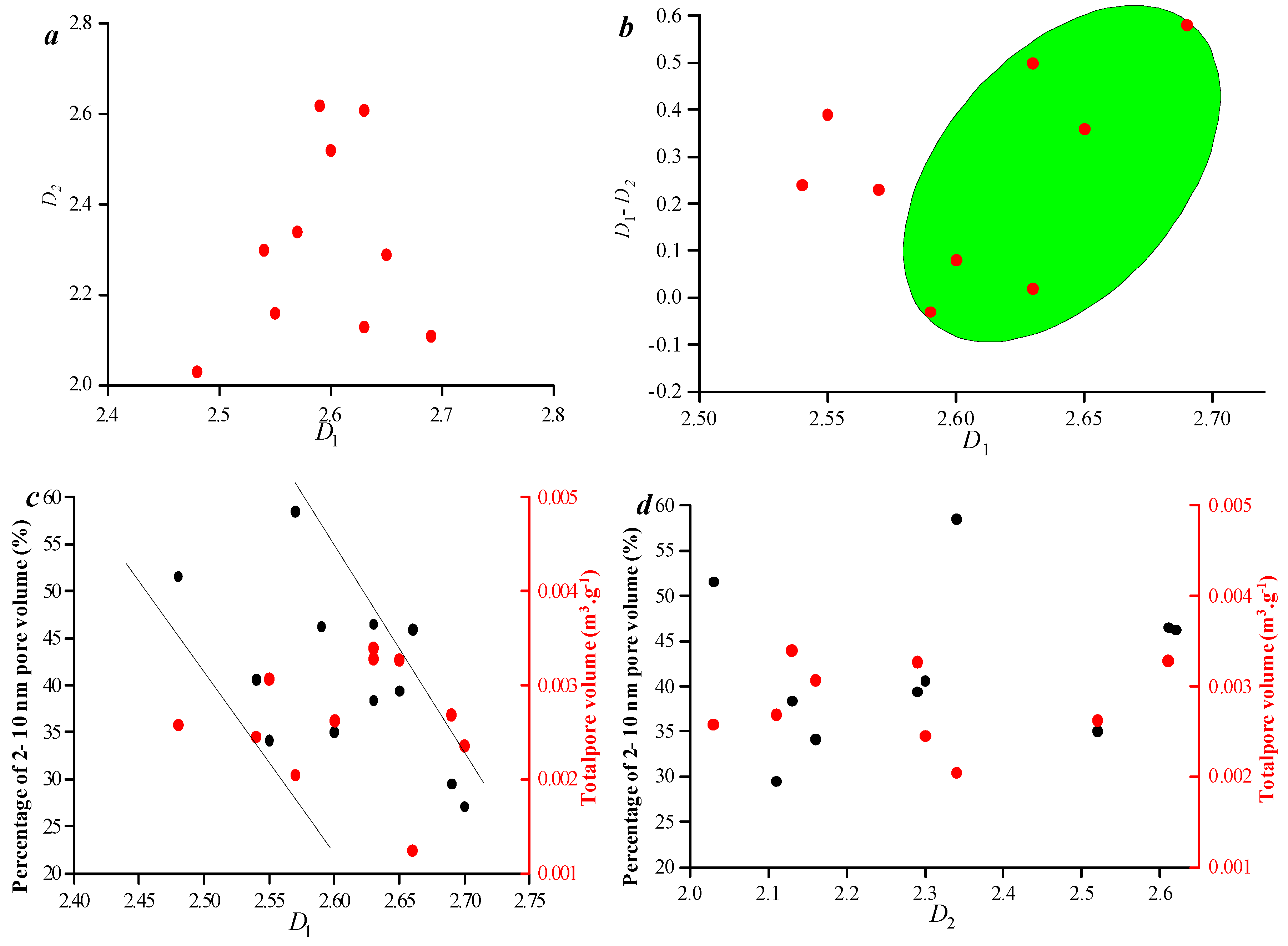

3.2. Adsorption Pore Distribution and Heterogeneity

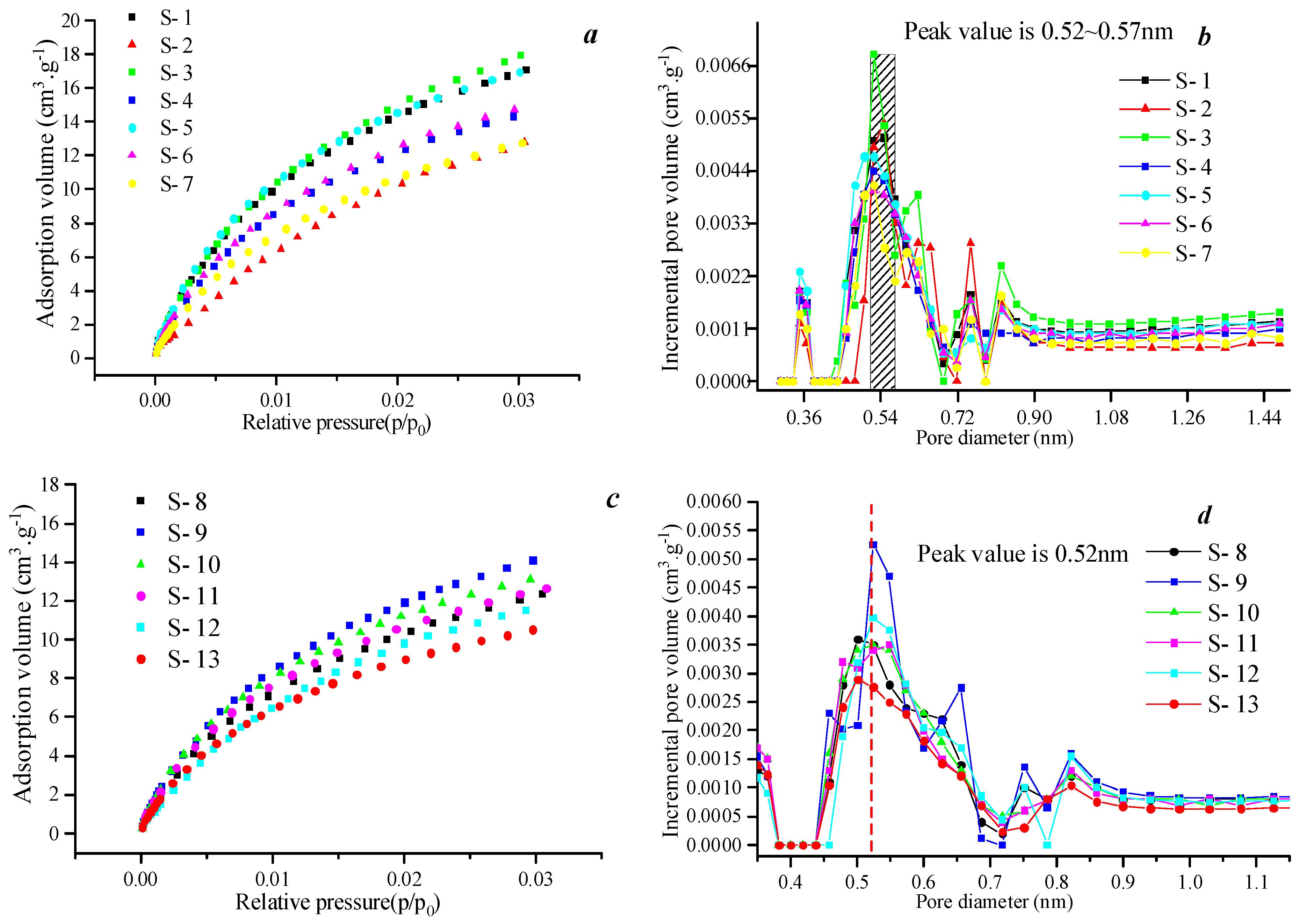

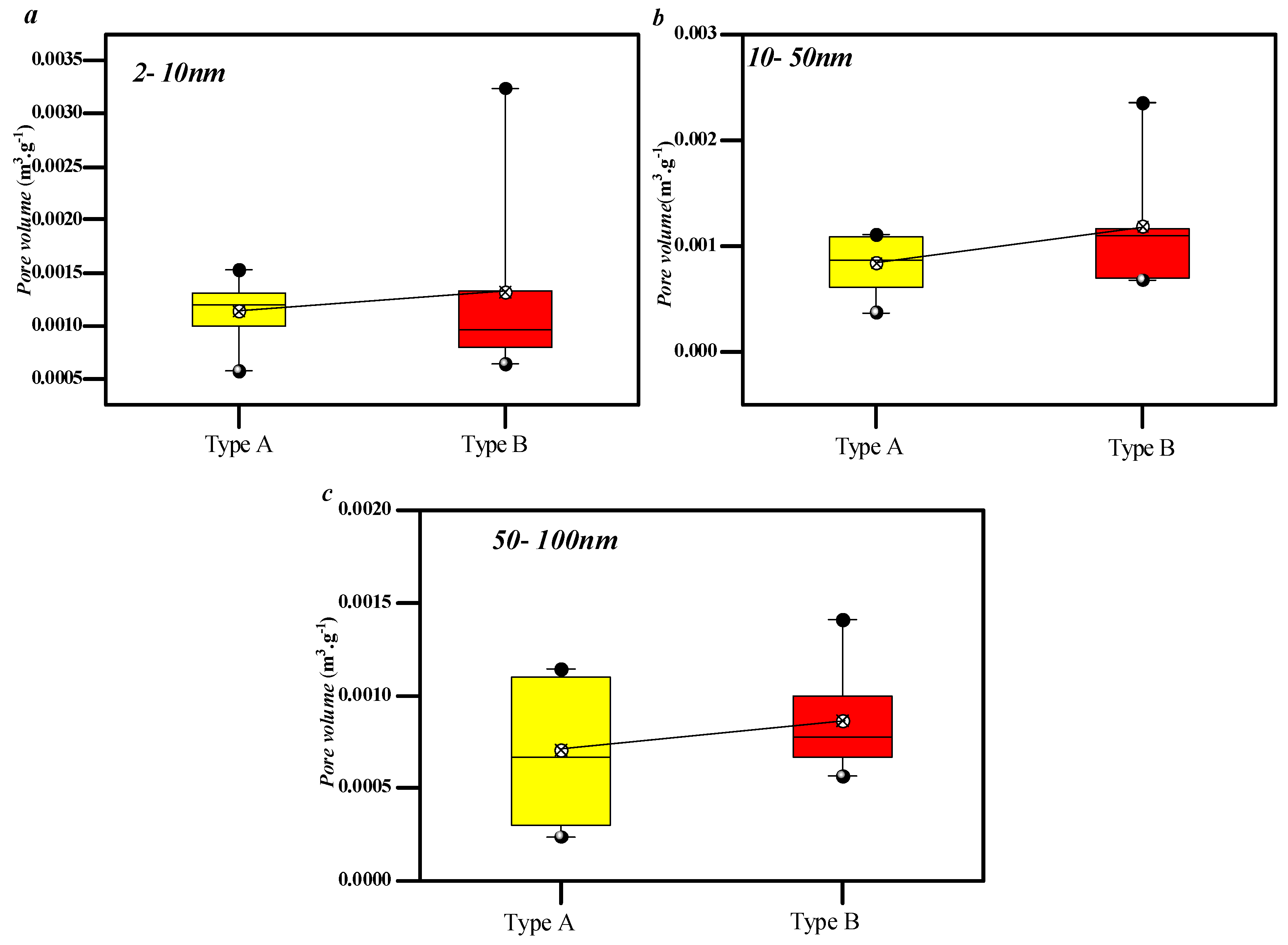

3.2.1. Microporous Structure of All Samples with Different Ash Content

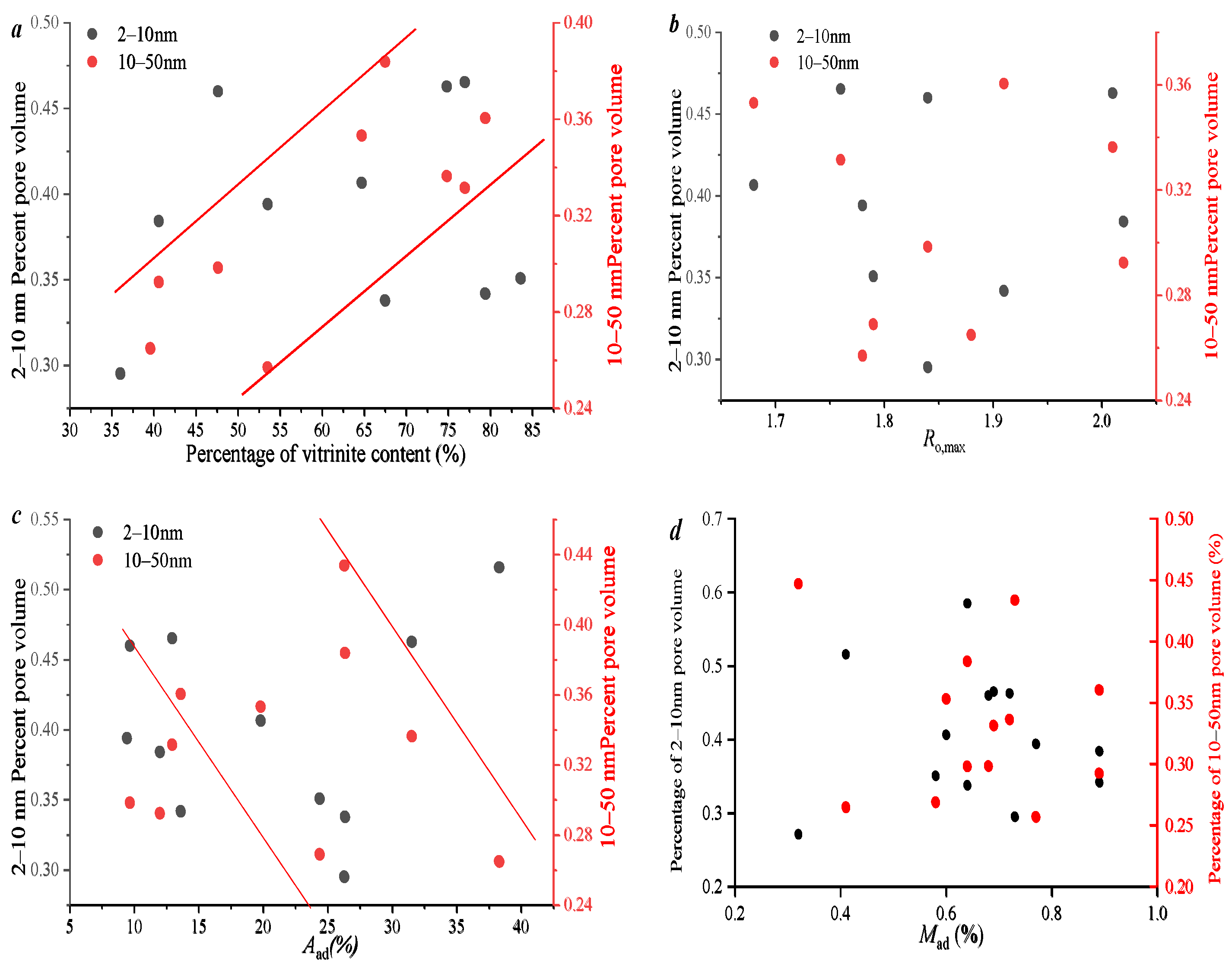

3.2.2. Mesoporous Structure of All Samples with Different Ash Content

4. Conclusions

- There is a significant negative correlation between ash content and both the specific surface area and volume of micropores, while a clear diminishing effect on mesopore volume is also demonstrated. These effects are primarily attributed to the filling and blocking by inorganic minerals, which constitute the main mechanism for the reduction in pore space.

- A clear primary–secondary relationship exists in the influences of industrial and maceral components. Among the proximate analysis components, only ash content plays a dominant regulatory role in pore structure, while the effects of moisture and volatile matter are weak or non-existent. Among maceral components, vitrinite specifically regulates mesopore development without significantly affecting micropores. This further clarifies the “ash-dominant, vitrinite-assisted” pattern governing pore development in low-to-medium maturity coals.

- The results indicate that the ash content of deep coal samples in the study area constrains the microporous structure of coal samples and has a significant impact on the methane adsorption and desorption characteristics of deep coal samples. Under the same conditions, the influence of thermal evolution degree on the pore and fracture structure of deep coal samples is relatively weak. This also means that in the process of deep coalbed methane development, special attention should be paid to the industrial components caused by differences in coal forming environments, which have a significant impact on the gas content in coal.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.X.; Wu, C.J.; Li, Y.; Li, J.B.; Feng, C.J.; Li, B.; Wen, Z.G.; Liu, X.N. Coal-forming sedimentary model and its control on vertical reservoir heterogeneity of the upper carboniferous Benxi formation in Ordos basin, China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.L.; Qiu, F.; Shu, L.Y.; Huo, Z.G.; Li, Z.T.; Cai, Y.D. Reservoir Properties and Gas Potential of the Carboniferous Deep Coal Seam in the Yulin Area of Ordos Basin, North China. Energies 2025, 18, 3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.W.; Chen, S.D.; Tang, D.Z.; Hou, K. Occurrence, Origin, and Infill Modification Effects of Minerals in Deep Coals in the Ordos Basin, China. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 22885–22903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.X.; Wang, H.C.; Sun, B.; Ouyang, Z.Y.; Dou, W.; Wang, B.; Lai, P.; Hu, Z.P.; Luo, B.; Yang, M.M.; et al. Pore Size Distribution and Fractal Characteristics of Deep Coal in the Daning-Jixian Block on the Eastern Margin of the Ordos Basin. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 32837–32852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.P.; Wang, Z.C.; Hu, D.P.; Wang, Y.; Huo, M.X.; Mu, X.Y.; Han, S.B. Gas-bearing evaluation of deep coal rock in the Yan’an gas field of the Ordos Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1438834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cui, M.R.; Zhang, J.J.; Liu, L.H.; Qu, J.; Li, W. Experimental study on dynamic occurrence and migration of gas and water in deep coal measure reservoirs in Yan’an area of Eastern Ordos Basin. Fuel 2026, 405, 136654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.K.; Wang, B.; Yu, X.N.; Tang, W.; Yu, M.N.; You, C.L.; Yang, J.H.; Wang, T.; Deng, Z. Comparative Study on Full-Scale Pore Structure Characterization and Gas Adsorption Capacity of Shale and Coal Reservoirs. Processes 2025, 13, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cai, Y.D.; Liu, D.M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, K.C.; Jiang, K.; Zhang, X.B.; Sun, X.L.; Wei, H.P. Full-scale pore structure and its impact on methane adsorption in deep coal reservoirs of the Zijinshan area, Eastern Ordos Basin. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 086618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Liu, D.M.; Cai, Y.D.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, F.R. Geological Control Mechanism of Coalbed Methane Gas Component Evolution Characteristics in the Daning-Jixian Area, Ordos Basin, China. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 19639–19652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; He, S.; Zheng, S.; Bai, Y.; Chen, W.; Meng, Y.; Jin, S.; Yao, H.; Jia, X. Critical tectonic events and their geological controls on deep buried coalbed methane accumulation in Daning-Jixian Block, eastern Ordos Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 17, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.T.; Yang, C.; Zheng, S.; Bai, Y.D.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.F.; Tian, W.G.; Sun, S.S.; Jin, S.W.; Wang, J.H.; et al. Geochemical characteristics of produced fluids from CBM wells and their indicative significance for gas accumulation in Daning-Jixian block, Ordos Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 17, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.M.; Hou, S.H.; Wang, X.J.; Yuan, Y.D.; Dang, Z.; Tu, M.K. Geological and hydrological controls on the pressure regime of coalbed methane reservoir in the Yanchuannan field: Implications for deep coalbed methane exploitation in the eastern Ordos Basin, China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2024, 294, 104619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.J.; Jia, C.Z.; Pang, X.Q.; Lin, J.; Zhang, C.L.; Ma, X.Z.; Qi, Z.G.; Chen, J.Q.; Hong, P.; Tao, H.; et al. Upper Paleozoic total petroleum system and geological model of natural gas enrichment in Ordos Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, D.Z.; Li, S.; Cao, D.Y.; Liu, J.C. Deciphering multiple controls on mesopore structural heterogeneity of paralic organic-rich shales: Pennsylvanian-Lower Permian Taiyuan and Shanxi formations, Weibei Coalfield, southwestern North China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 195, 107613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.F.; Dong, D.Z.; Qiu, Z.; Wu, C.J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.M.; Liu, D.X.; Deng, Z.; Zhou, S.W.; Pan, S.Q. Sedimentology and geochemistry of Carboniferous-Permian marine-continental transitional shales in the eastern Ordos Basin, North China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2021, 571, 110389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, B.; Tian, H.N.; Sun, J.Y.; Liu, L.; Liang, X.; Chen, B.L.; Yu, B.S.; Zhang, Z. Multilayer Gas-Bearing System and Productivity Characteristics in Carboniferous-Permian Tight Sandstones: Taking the Daning-Jixian Block, Eastern Ordos Basin, as an Example. Energies 2025, 18, 2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.X.; Zhang, X.L.; Ma, L.; Wu, H.C.; Ashraf, M.A. Geological Characteristics of Unconventional Gas in Coal Measure of Upper Paleozoic Coal Measures in Ordos Basin, China. Earth Sci. Res. J. 2016, 20, Q1–Q5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.W.; Shen, Y.Y.; van Loon, A.; Raji, M.; Zhang, Z.H.; Song, G.Z.; Ren, Z.H.; Wang, Y.J.; Wang, D.D. Sequence stratigraphy of the Middle Jurassic Yan’an formation (NE Ordos Basin, China), relationship with climate conditions and basin evolution, and coal maceral’s characteristics. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 10, 1086298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.J.; Lv, D.W.; Hower, J.C.; Zhang, Z.H.; Raji, M.; Tang, J.G.; Liu, Y.M.; Gao, J. Geochemical characteristics and paleoclimate implication of Middle Jurassic coal in the Ordos Basin, China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 144, 104848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.B.; Fan, L.Y.; Yan, X.X.; Zhou, G.X.; Zhang, H.; Jing, X.Y.; Zhang, M.B. Enrichment conditions and resource potential of coal-rock gas in Ordos Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 1122–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.Y.; Veerle, V.; Zhang, J.J.; Chen, S.B.; Chang, X.C.; Du, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, C.T.; Luo, J.H.; Quan, F.K.; et al. Control mechanism of pressure drop rate on coalbed methane productivity by using production data and physical simulation technology. Fuel 2026, 406, 137060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.; Zhang, J.; Lv, D.; Vandeginste, V.; Chang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D.; Han, S.; Liu, Y. Effect of water occurrence in coal reservoirs on the production capacity of coalbed methane by using NMR simulation technology and production capacity simulation. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 243, 213353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yang, W.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Xu, W.L.; Gong, D.Y.; Jin, H.; Song, W.; Liu, G.; Zhang, C.L.; Huang, S.P. Research progresses in geological theory and key exploration areas of coal-formed gas in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 1435–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Xiao, L.; Li, P.; Arbuzov, S.I.; Ding, S.L. Occurrence mode of selected elements of coal in the Ordos Basin. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2019, 37, 1680–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yaari, A.; Ching, D.L.C.; Sakidin, H.; Muthuvalu, M.S.; Zafar, M.; Haruna, A.; Merican, Z.M.A.; Yunus, R.B.; Al-Dhawi, B.N.S.; Jagaba, A.H. The effects of nanofluid thermophysical properties on enhanced oil recovery in a heterogenous porous media. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9, 100556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.B.; Li, Q.; Sun, F.R.; Yin, T.T.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z.H.; Qiu, F.; Zhou, K.Y.; Chen, J.M. Geological Controls on Gas Content of Deep Coal Reservoir in the Jiaxian Area, Ordos Basin, China. Processes 2024, 12, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Wang, H.S.; Dilcher, D.L.; Bugdaeva, E.; Tan, X.; Li, T.; Na, Y.L.; Sun, C.L. Middle Jurassic Plant Diversity and Climate in the Ordos Basin, China. Paleontol. J. 2019, 53, 1216–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.J.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Dong, J.L.; Zhang, M.H. Deep coal seams and water-bearing structures detection with CSAMT lateral constraint inversion technique in Ordos basin. Appl. Geophys. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.Q.; Ji, P.; Lai, G.L.; Chi, C.Q.; Liu, Z.S.; Wu, X.L. Diverse microbial community from the coalbeds of the Ordos Basin, China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012, 90, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Wang, K.L.; Dong, G.D.; Zhou, X.Z.; Chen, Y.H.; Zhuang, Y.P.; Gao, X.; Du, X.W. Geochemical Characteristics and Paleoenvironmental Significance of No. 5 Coal in Shanxi Formation, Central-Eastern Ordos Basin (China). Minerals 2025, 15, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Wei, C.T.; Luo, J.H.; Lu, G.W.; Quan, F.K.; Zheng, K.; Peng, Y.J. Volume and Surface Distribution Heterogeneity of Nano-pore in Coal Samples by CO2 and N2 Adsorption Experiments. Acta Geol. Sin.-Engl. Ed. 2020, 94, 1662–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.M.; Sun, H.T.; Zhang, D.M.; Yang, K.; Li, X.L.; Wang, D.K.; Li, Y.N. Experimental study of effect of liquid nitrogen cold soaking on coal pore structure and fractal characteristics. Energy 2023, 275, 127470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.X.; Cheng, Y.P.; Hu, B.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, C.H.; Yi, M.H.; Wang, L. Effects of coal pore structure on methane-coal sorption hysteresis: An experimental investigation based on fractal analysis and hysteresis evaluation. Fuel 2020, 269, 117438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, G.W.; Shi, Y.J.; Zhao, T.P.; Pang, X.J.; Fan, X.C.; Qin, Z.Q.; Fan, X.Q. Pore structure and fractal characteristics of Ordovician Majiagou carbonate reservoirs in Ordos Basin, China. Aapg Bull. 2019, 103, 2573–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Classification | Depth (m) | Sample No. | Aad | Mad | FCad | Vitrinite | Liptinite | Inertinite | Ro,max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3083.18 | S1 | 7.95 | 0.77 | 81.32 | 57.44 | 2.42 | 40.14 | 1.9 |

| 3401.7 | S2 | 9.43 | 0.73 | 77.41 | 53.52 | 0 | 46.348 | 1.85 | |

| 3100.95 | S3 | 9.66 | 0.89 | 79.36 | 47.62 | 12.59 | 39.8 | 1.88 | |

| 3403.8 | S4 | 11.98 | 0.72 | 76.29 | 40.57 | 0 | 59.42 | 1.84 | |

| 3260.12 | S5 | 12.94 | 0.89 | 78.53 | 76.96 | 0 | 23.06 | 1.84 | |

| 3403.42 | S6 | 13.6 | 0.64 | 73.63 | 79.38 | 0 | 20.76 | 1.76 | |

| 3404.57 | S7 | 19.8 | 0.32 | 66.68 | 64.7 | 0 | 35.29 | 2.01 | |

| B | 3405.6 | S8 | 24.37 | 0.41 | 61.64 | 83.59 | 0 | 16.41 | 1.02 |

| 3109.74 | S9 | 26.28 | 0.69 | 62.78 | 36.01 | 25.87 | 38.11 | 1.78 | |

| 3400.83 | S10 | 26.33 | 0.58 | 59.27 | 67.48 | 0 | 32.54 | 1.91 | |

| 3261.67 | S11 | 31.51 | 0.6 | 58.92 | 74.81 | 0 | 25.13 | 2.02 | |

| 3065.9 | S12 | 32.44 | 0.64 | 55.16 | 52.47 | 11.41 | 36.12 | 1.68 | |

| 3094.08 | S13 | 38.29 | 0.68 | 51.86 | 39.58 | 13.43 | 47 | 1.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qin, Z.; Chen, L.; Li, Z.; Xu, G.; Du, L.; Jia, J.; Yang, J.; Agarwal, V.; Grebby, S. Multiscale Pore Structure and Heterogeneity of Deep Medium-Rank Coals in the Eastern Ordos Basin. Processes 2025, 13, 3912. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123912

Qin Z, Chen L, Li Z, Xu G, Du L, Jia J, Yang J, Agarwal V, Grebby S. Multiscale Pore Structure and Heterogeneity of Deep Medium-Rank Coals in the Eastern Ordos Basin. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3912. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123912

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Zhengyuan, Lu Chen, Zhiguo Li, Guangwei Xu, Lianying Du, Jinlong Jia, Jianxiong Yang, Vivek Agarwal, and Stephen Grebby. 2025. "Multiscale Pore Structure and Heterogeneity of Deep Medium-Rank Coals in the Eastern Ordos Basin" Processes 13, no. 12: 3912. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123912

APA StyleQin, Z., Chen, L., Li, Z., Xu, G., Du, L., Jia, J., Yang, J., Agarwal, V., & Grebby, S. (2025). Multiscale Pore Structure and Heterogeneity of Deep Medium-Rank Coals in the Eastern Ordos Basin. Processes, 13(12), 3912. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123912