Primary Constitution and Proximal Analysis of Three Fabaceae by the Thermogravimetric and Chemical Methods for Their Potential Use as Bioenergy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Preparation

2.2. Primary Constitution and Proximal Analysis by the TGA-DTG and Chemical Methods

2.2.1. Thermogravimetric Method (TGA-DTG)

2.2.2. Chemical Method

2.3. Higher Heating Value

2.4. Elemental and Inorganic Analyses

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Primary Constitution: Proximal Analysis by the Thermogravimetric and Chemical Methods

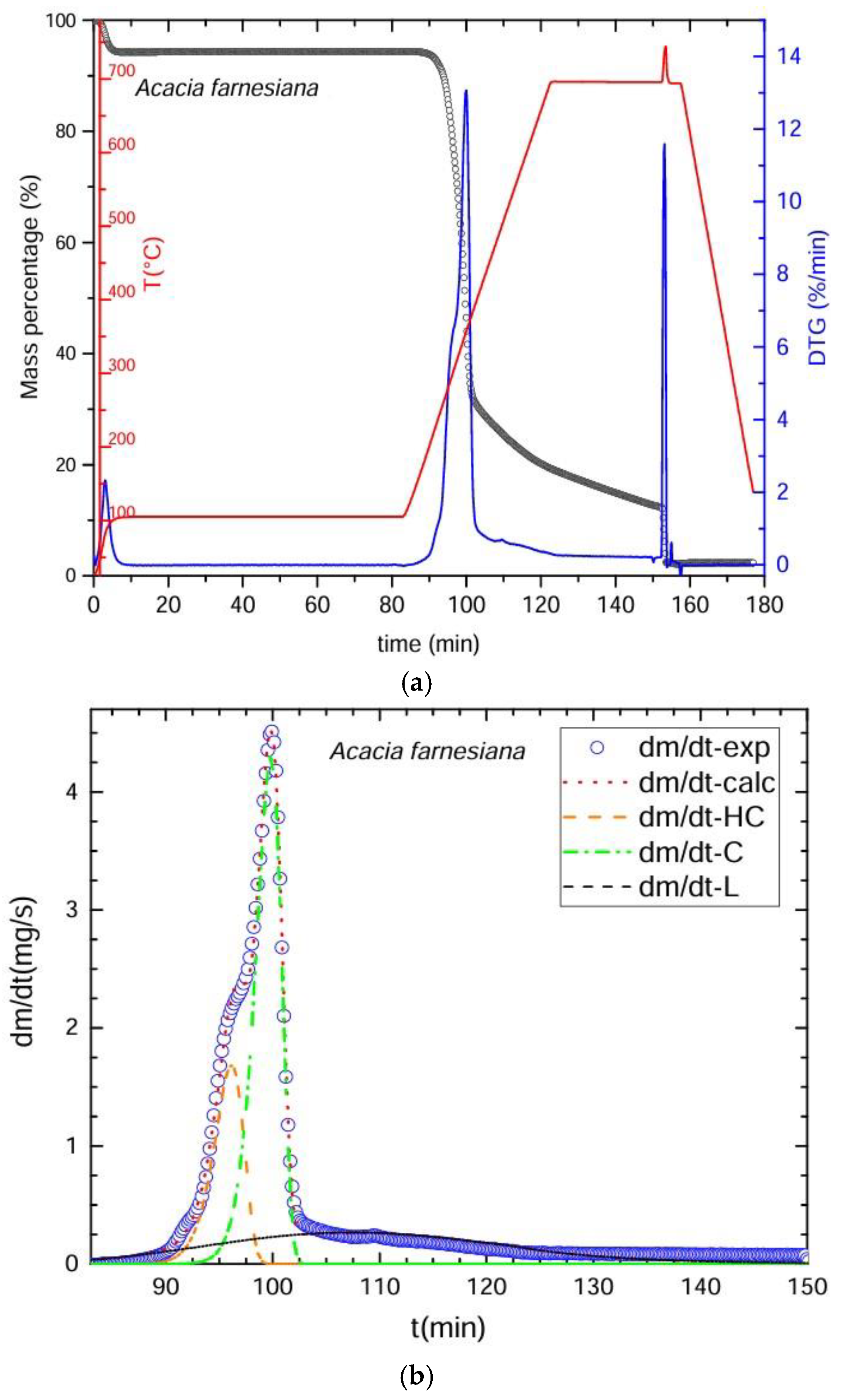

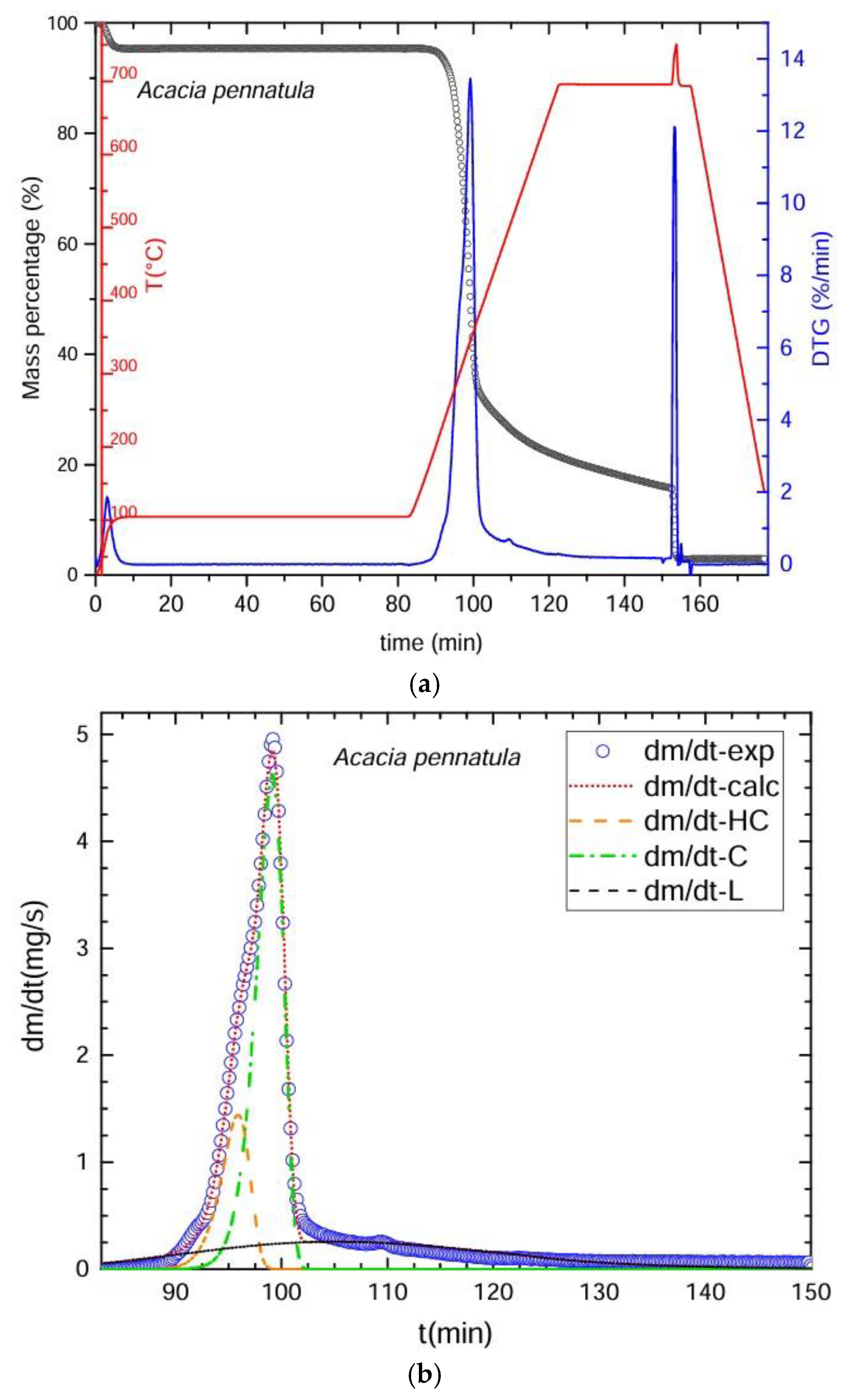

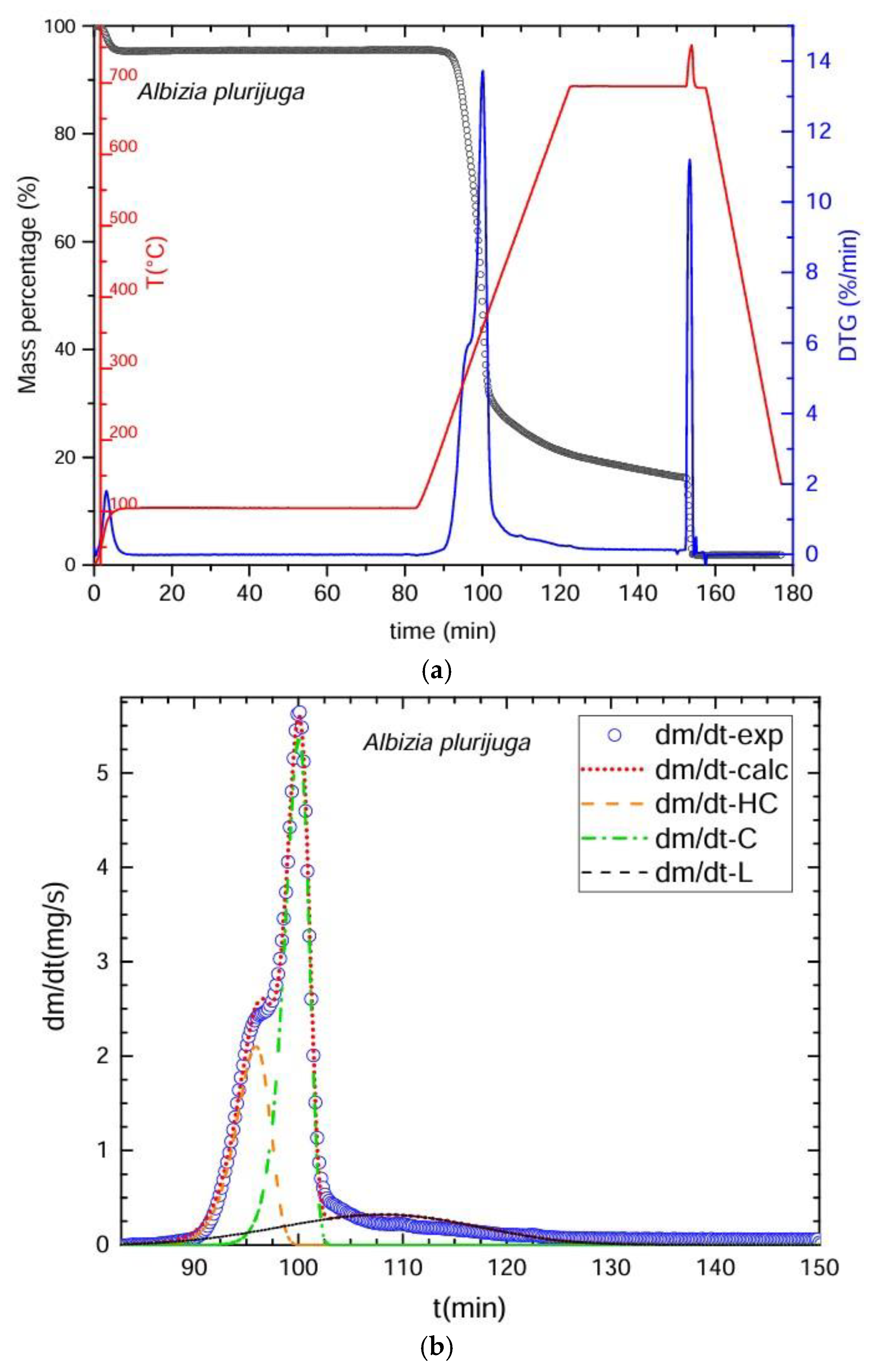

3.2. Thermogravimetric Process

3.3. Deconvolution of the DTG Curves

3.4. Higher Heating Value

3.5. Elemental and Inorganic Elemental Analyses

3.5.1. Elemental Analysis

3.5.2. Microanalysis of Ash

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rego, F.; Dias, A.P.S.; Casquilho, M.; Rosa, F.C.; Rodrigues, A. Fast determination of lignocellulosic composition of poplar biomass by thermogravimetry. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 122, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniza, R.; Chen, W.H.; Kwon, E.E.; Bach, Q.V.; Hoang, A.T. Lignocellulosic biofuel properties and reactivity analyzed by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) toward zero carbon scheme: A critical review. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 22, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, J.; Kovács, S.; Oláh, J.; Divéki, Z.; Balázs, E. Bioeconomy: Biomass and biomass-based energy supply and demand. New Biotechnol. 2021, 60, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Tera, O.A.; López-Sosa, L.B.; Pintor-Ibarra, L.F.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G.; Morales-Máximo, M. Evaluation of Bursera cuneata Schltdl. wood residues for use as densified biofuels. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón Correa, A.; Dorantes Hernández, F.; Mejía Valencia, S.; Alamilla Fonseca, L.N. Características Macroscópicas, Propiedades y Usos de la Madera de Especies Nativas y Exóticas de México; Comisión Nacional Para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO): Mexico City, Mexico, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rico-Arce, M.L.; Gale, S.L.; Maxted, N. A taxonomic study of Albizia (Leguminosae: Mimosoideae: Ingeae) in Mexico and Central America. An. Jard. Bot. Madr. 2008, 65, 255–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Casillas, R.; López-López, M.C.; Becerra-Aguilar, B.; Dávalos-Olivares, F.; Satyanarayana, K.G. Obtaining dissolving grade cellulose from the huizache (Acacia farnesiana L. Willd.) plant. BioResources 2019, 14, 3301–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolinar-Hidalgo, F.; Honorato-Salazar, J.A.; Colotl-Hernández, G. Caracterización energética de la madera de Acacia pennatula Schltdl. & Cham. y Trema micrantha (L.) Blume. Rev. Mex. Cienc. For. 2017, 8, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintor-Ibarra, L.F.; Méndez-Zetina, F.D.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G.; Alvarado-Flores, J.J. Capítulo 5: Caracterización proximal de los biocombustibles sólidos. In Aplicaciones Energéticas de la Biomasa: Perspectivas para la Caracterización Local de Biocombustibles Sólidos; Universidad Intercultural Indígena de Michoacán: Pátzcuaro, Mexico, 2023; pp. 87–116. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado Flores, J.J.; Alcaraz Vera, J.V.; Ávalos Rodríguez, M.L.; Rutiaga Quiñones, J.G.; Valencia Espino, J.; Guevara Martínez, S.J.; Ríos, E.T.; Zarraga Aguado, R. Kinetic, thermodynamic, FT-IR, and primary constitution analysis of Sargassum spp. from Mexico: Potential for hydrogen generation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 30107–30127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agu, O.S.; Tabil, L.G.; Mupondwa, E.; Emadi, B.; Cree, D. Pelletization and quality evaluation of torrefied selected biomass with microwave absorber. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Jia, D.; Evrendilek, F.; Liu, J. Pyrolytic Valorization of Polygonum multiflorum Residues: Kinetic, Thermodynamic, and Product Distribution Analyses. Processes 2025, 13, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintor-Ibarra, L.F.; Alvarado-Flores, J.J.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G.; Alcaraz-Vera, J.V.; Ávalos-Rodríguez, M.L.; Moreno-Anguiano, O. Chemical and Energetic Characterization of the Wood of Prosopis laevigata: Chemical and Thermogravimetric Methods. Molecules 2024, 29, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, D.; Urueña, A.; Piñero, R.; Barrio, A.; Tamminen, T. Determination of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin content in different types of biomasses by thermogravimetric analysis and pseudocomponent kinetic model (TGA-PKM method). Processes 2020, 8, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Negrín, A.M.; López-González, L.M.; Casdelo-Gutiérrez, N.L. Pretratamientos aplicados a biomasas lignocelulósicas: Una revisión de los principales métodos analíticos utilizados para su evaluación. Rev. Cuba. De Química 2022, 34, 87–110. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen, R.C. The chemical composition of wood. Chem. Solid Wood 1984, 207, 57–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, H.O.; Câmara, A.B.F.; Campos, L.M.A.; de Carvalho, L.S. Novel methodology for lignocellulose composition, polymorphism and crystallinity analysis via deconvolution of differential thermogravimetry data. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 31, 1915–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldarriaga, J.F.; Aguado, R.; Pablos, A.; Amutio, M.; Olazar, M.; Bilbao, J. Fast characterization of biomass fuels by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). Fuel 2015, 140, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalante, J.; Chen, W.H.; Tabatabaei, M.; Hoang, A.T.; Kwon, E.E.; Lin, K.Y.A.; Saravanakumar, A. Pyrolysis of lignocellulosic, algal, plastic, and other biomass wastes for biofuel production and circular bioeconomy: A review of thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 169, 112914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TAPPI T264 cm-97; Preparation of Wood for Chemical Analysis. TAPPI Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2000.

- ASTM E11-20; Standard Specification for Woven Wire Test Sieve Cloth and Test Sieves. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D5142-90; Standard Test Methods for Proximate Analysis of the Analysis Sample of Coal and Coke by Instrumental Procedures. West Conshohocken: PA, USA, 1998.

- ASTM D4442-20; Standard Test Methods for Direct Moisture Content Measurement of Wood and Wood-Based Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D1102-84; Standard Test Method for Ash in Wood. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- ASTM E872–82; Standard Test Method for Volatile Matter in the Analysis of Particulate Wood Fuels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- Van Soest, P.V.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNE-EN ISO 18125; Biocombustibles Sólidos. Determinación del Poder Calorífico. Asociación Española de Normalización y Certificación (AENOR): Madrid, Spain, 2018.

- White, R.H. Effect of lignin content and extractives on the higher heating value of Wood. Wood Fiber Sci. 1987, 19, 446–452. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, T.; Márquez, F.; Rodríguez-Mirasol, J.; Rodríguez, J.J. Predicting heating values of lignocellulosics and carbonaceous materials from proximate analysis. Fuel 2001, 80, 1567–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbaş, A. Calculation of higher heating values of biomass fuels. Fuel 1997, 76, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotz, L.; Giazzi, G. Characterization of Pharmaceutical Products by the Thermo Scientific FLASH 2000 Elemental Analyzer; Thermo Fischer Scientific: Milan, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ghetti, P.; Ricca, L.; Angelini, L. Thermal analysis of biomass and corresponding pyrolysis products. Fuel 1996, 75, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcibar-Orozco, J.A.; Josue, D.B.; Ríos Hurtado, J.C.; Rangel Méndez, J.R. Influence of iron content, surface area and charge distribution in the arsenicremoval by activated carbons. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 249, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Studio. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Yu, S.; Kim, M.; Ryu, C. Progressive deconvolution of biomass thermogram to derive lignocellulosic composition and pyrolysis kinetics for parallel reaction model. Energy 2022, 254, 124446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Herrera, F.; Pintor-Ibarra, L.F.; Musule, R.; Nava-Berumen, C.A.; Alvarado-Flores, J.J.; González-Ortega, N.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G. Chemical and energetic properties of seven species of the Fabaceae family. South-East Eur. For. 2023, 14, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Aquino, F.; Jiménez-Mendoza, M.E.; Santiago-García, W.; Suárez-Mota, M.E.; Aquino-Vásquez, C.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G. Energy properties of 22 timber species from Oaxaca, Mexico. South-East Eur. For. 2022, 13, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.S.A.; Mohammad, M.; Sua’it, M.S.; Ahmad, A.; Mohamed, N.S. Novel approach for the utilization of ionic liquid-based cellulose derivative biosourced polymer electrolytes in safe sodium-ion batteries. Polym. Bull. 2021, 78, 5355–5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichosz, S.; Masek, A. Thermal Behavior of Green Cellulose-Filled Thermoplastic Elastomer Polymer Blends. Molecules 2020, 25, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Montemayor, F.J.; López-Badillo, C.M.; Aguilar-González, C.N.; Ávalos-Belmontes, F.; Castañeda-Facio, A.O.; Reyna-Martínez, R.; Neira-Velázquez, M.G.; Soria-Argüello, G.; Navarro-Rodríguez, D.; Delgado-Aguilar, M.; et al. Effect of cold air plasmas on the morphology and thermal stability of bleached hemp fibers. Rev. Mex. De Ing. Química 2020, 19 (Suppl. 1), 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somorin, T.; Parker, A.; McAdam, E.; Williams, L.; Tyrrel, S.; Kolios, A.; Jiang, Y. Pyrolysis characteristics and kinetics of human faeces, simulant faeces and wood biomass by thermogravimetry–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry methods. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 3230–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, A.D. Glucose, not cellobiose, is the repeating unit of cellulose and why that is important. Cellulose 2017, 24, 4605–4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshadri, V.; Westmoreland, P.R. Concerted reactions and mechanism of glucose pyrolysis and implications for cellulose kinetics. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 11997–12013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skreiberg, A.; Skreiberg, Ø.; Sandquist, J.; Sørum, L. TGA and macro-TGA characterisation of biomass fuels and fuel mixtures. Fuel 2011, 90, 2182–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Wang, C.W.; Ong, H.C.; Show, P.L.; Hsieh, T.H. Torrefaction, pyrolysis and two-stage thermodegradation of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin. Fuel 2019, 258, 116168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebringerová, A.; Hromádková, Z.; Heinze, T. Hemicellulose. In Polysaccharides I: Structure, Characterization and Use; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöström, E. Wood Chemistry: Fundamentals and Applications; Academic Press, Inc.: London, UK, 1981; pp. 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Li, W.; Mabon, R.; Broadbelt, L.J. A critical review on hemicellulose pyrolysis. Energy Technol. 2017, 5, 52–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurazzi, N.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Rayung, M.; Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Shazleen, S.S.; Rani, M.S.A.; Abdan, K. Thermogravimetric analysis properties of cellulosic natural fiber polymer composites: A review on influence of chemical treatments. Polymers 2021, 13, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado Flores, J.J.; Pintor Ibarra, L.F.; Mendez Zetina, F.D.; Rutiaga Quiñones, J.G.; Alcaraz Vera, J.V.; Ávalos Rodríguez, M.L. Pyrolysis and Physicochemical, Thermokinetic and Thermodynamic Analyses of Ceiba aesculifolia (Kunth) Britt and Baker Waste to Evaluate Its Bioenergy Potential. Molecules 2024, 29, 4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fengel, D.; Wegener, G. Wood Chemistry, Ultrastructure, Reactions; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 66–222. [Google Scholar]

- Poletto, M.; Ornaghi Junior, H.L.; Zattera, A.J. Native cellulose: Structure, characterization and thermal properties. Materials 2014, 7, 6105–6119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chávez-Sifontes, M.; Domine, M.E. Lignin, structure and applications: Depolymerization methods for obtaining aromatic derivatives of industrial interest. Av. En Cienc. E Ing. 2013, 4, 15–46. [Google Scholar]

- Brebu, M.; Vasile, C. Thermal degradation of lignin—A review. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2010, 44, 353–363. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Parra, A.; Bustamante-García, V.; Ngangyo-Heya, M.; Corral-Rivas, J.J. Capítulo 1. Contenido de humedad y calidad de biocombustibles sólidos. In Química de Los Materiales Lignocelulósicos y su Potencial Bioenergético; Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolas de Hidalgo: Morelia, México, 2016; pp. 12–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G.; Pintor-Ibarra, L.F.; Orihuela-Equihua, R.; González-Ortega, N.; Ramírez-Ramírez, M.A.; Carrillo-Avila, N.; Carrillo-Parra, A.; Navarrete-García, M.A.; Ruiz-Aquino, F.; Rangel-Méndez, J.R.; et al. Characterization of Mexican waste biomass relative to energy generation. BioResources 2020, 15, 8529–8553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Mendoza, M.E.; Ruiz-Aquino, F.; Aquino-Vásquez, C.; Santiago-García, W.; Santiago-Juárez, W.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G. Aprovechamiento de leña en una comunidad de la Sierra Sur de Oaxaca, México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. For. 2023, 14, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamanit, A.; Khongphakdi, P.; Tirawanichakul, Y.; Phusunti, N. Investigation of yields and qualities of pyrolysis products obtained from oil palm biomass using an agitated bed pyrolysis reactor. Biofuel Res. J. 2019, 6, 1065–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Sun, R.; Meng, X.; Vorobiev, N.; Schiemann, M.; Levendis, Y.A. Carbon, sulfur and nitrogen oxide emissions from combustion of pulverized raw and torrefied biomass. Fuel 2017, 188, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 16948; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Total Content of Carbon, Hydrogen and Nitrogen. International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2015.

- ISO 16994; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Total Content of Sulfur and Chlorine. International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2016.

- Endriss, F.; Kuptz, D.; Hartmann, H.; Brauer, S.; Kirchhof, R.; Kappler, A.; Thorwarth, H. Analytical Methods for the Rapid Determination of Solid Biofuel Quality. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2023, 95, 1503–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNE-EN 14961-1; Especificaciones y Clases de Combustibles. Parte 1: Requisitos Generales. Asociación Española de Normalización y Certificación (AENOR): Madrid, Spain, 2011.

- UNE-EN ISO 17225-1; Biocombustibles Sólidos. Especificaciones y Clases de Combustibles. Parte 1: Requisitos Generales. Asociación Española de Normalización y Certificación (AENOR): Madrid, Spain, 2020.

- Pintor-Ibarra, L.F.; Carrillo-Parra, A.; Herrera-Bucio, R.; López-Albarrán, P.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G. Physical and chemical properties of timber byproducts from Pinus leiophylla, P. montezumae and P. pseudostrobus for a bioenergetic use. Wood Res. 2017, 62, 849–861. [Google Scholar]

- Obernberger, I.; Thek, G. The Pellet Handbook: The Production and Thermal Utilisation of Pellets; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 16967; Biocombustibles Sólidos—Determinación de Elementos Mayoritarios—Al, Ca, Fe, Mg, P, K, Si, Na y Ti. Beuth Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2015.

| Thermogravimetry (TGA) | Deconvolution (DTG) | Chemical Method |

|---|---|---|

| Pyrolysis was conducted in an inert atmosphere with nitrogen gas (N2, 99.99% purity) at a flow rate of 20 mL/min. Heating and cooling speeds were 30 °C/min, divided into four stages to complete the proximal analysis. Stage 1: began at 25–100 °C for 80 min to determine the % of moisture. Stage 2: 100–700 °C for 30 min to obtain the amount of fixed carbon. Stage 3: oxygen was applied for 5 min at 700 °C to eliminate organic material residues. Stage 4: cooling from 700 to 25 °C in 20 min. The residue left represented the ash. The % of volatile material was calculated as VM = [100 − (% moisture + % ash + % fixed carbon)]. Over 80,000 pieces of data were obtained from each sample. Time required for the procedure: 160 min/sample. | DTG Deconvolution was used to determine the primary components: cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin. The graphs of the obtained curves were plotted in the Scilab platform. We utilized the ODE subroutine (ordinary differential equations) based on the Adams method for non-rigid ODE problems that integrates the differential equation multiple linear regressions. To calculate the ODE function, a function containing the ordinary differential equations is constructed using arithmetic operators. This is achieved by identifying the number of variables that change over time and the corresponding rates of change that allow the calculation of the percentages of the main components of biomass, i.e., hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin. This is usually the most complex part, because the optimization function must be constructed, i.e., ultimately ensuring that Scilab finds the best possible values for the mathematical model to predict the experimental results. To achieve this, the combination of adjustment parameters that minimizes the value of an error objective function is found, which in this case is the difference between the results calculated with the model and those measured experimentally. The evolution of the temperature over time, the conversion of each polymer, and the overall conversion will then be calculated, and from there, the change ratio predicted by the model with that combination of adjustment parameters can be calculated. Optimization of the kinetic parameters to adjust the experimental results was carried out with the Fminsearch subroutine, based on Nelder and Mead’s algorithm. To calculate the percentages of water, carbon, and ash, the initial mass value is considered, as well as the start and end times of the drying process. Subsequently, the start time of the pyrolysis process is considered, and commands are integrated into Scilab to calculate the percentages of water, carbon, and ash. In addition, conversion factors for mass (grams), time (seconds), and temperature (kelvin) are integrated. The % of extractives was calculated by difference: % extractives = [100 − (% cellulose + % hemicelluloses + % lignin + % ash)]. | The fiber and proximal analyses and the calculations of results were obtained based on anhydrous weight. Neutral detergent fiber (NDF): digestion with 20 g of Na2SO3, 4 mL of α-amylase at 100 °C for 75 min, followed by washing in hot H2O and CH3CH3 with dehydration at 100 °C for 24 h. Acid detergent fiber (ADF): conducted with 20 g of C19H42BrN in 1 L of H2SO4 1 N for 60 min, followed by washing with hot H2O and CH3CH3 and dehydration at 100 °C for 24 h. Insoluble lignin (IL): digestion with H2SO4 at 72% for 90 min, then washing with hot H2O and dehydration at 100 °C for 24 h. Equations (1)–(4) were used to calculate the percentages of extractables, hemicelluloses, lignin and fixed carbon. Time required for the procedure = 76 h per lot of 16 samples. |

| Method | A. farnesiana | A. pennatula | A. plurijuga |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose (%) | |||

| TGA-DTG | 57.49 A,a (±0.51) | 54.19 A,b (±1.78) | 58.73 A,a (±0.74) |

| Chemical | 58.03 A,b (±0.68) | 54.96 A,c (±0.34) | 60.10 A,a (±0.45) |

| Hemicelluloses (%) | |||

| TGA-DTG | 11.03 B,a (±0.21) | 11.41 A,a (±0.54) | 11.15 A,a (±0.10) |

| Chemical | 11.75 A,a (±0.27) | 11.50 A,ab (±0.46) | 10.81 A,b (±0.33) |

| Lignin (%) | |||

| TGA-DTG | 18.98 A,a (±0.01) | 19.20 A,a (±1.49) | 18.06 A,a (±1.08) |

| Chemical | 19.21 A,a (±0.38) | 19.24 A,a (±0.65) | 18.16 A,a (±0.81) |

| Extractives (%) | |||

| TGA-DTG | 12.46 A,a (±0.71) | 15.16 A,a (±3.75) | 12.04 A,a (±1.39) |

| Chemical | 10.78 B,b (±0.17) | 13.96 A,a (±0.12) | 10.73 A,b (±0.29) |

| Ash (%) | |||

| TGA-DTG | 2.30 A,b (±0.01) | 2.90 A,a (±0.11) | 1.41 A,c (±0.21) |

| Chemical | 1.80 B,b (±0.01) | 2.57 B,a (±0.02) | 1.09 A,c (±0.05) |

| Moisture (%) | |||

| TGA-DTG | 5.84 A,a (±0.17) | 3.83 A,b (±0.91) | 4.11 A,b (±0.32) |

| Chemical | 5.35 B,a (±0.23) | 4.36 A,b (±0.17) | 4.50 Ab (±0.17) |

| Fixed carbon (%) | |||

| TGA-DTG | 13.43 B,ab (±0.52) | 12.83 B,b (±0.13) | 14.04 B,a (±0.13) |

| Chemical | 19.07 Aa (±0.08) | 18.26 A,a (±0.83) | 18.24 A,a (±0.25) |

| Volatile material (%) | |||

| TGA-DTG | 78.34 A,b (±0.69) | 80.40 A,a (±0.74) | 80.50 A,a (±0.79) |

| Chemical | 79.12 A,b (±0.07) | 79.15 A,b (±0.82) | 80.67 A,a (±0.25) |

| Calorific Value (MJ/kg) | A. farnesiana | A. pennatula | A. plurijuga |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bomb calorimeter | 19.40 B,a (±0.42) | 18.49 B,b (±0.24) | 19.61 A,a (±0.27) |

| Chemical composition | 20.04 A,b (±0.04) | 20.25 A,a (±0.05) | 19.96 A,b (±0.05) |

| Proximal analysis | 20.26 A,a (±0.01) | 19.98 A,b (±0.15) | 20.24 A,a (±0.04) |

| Elementary analysis | 18.00 C,a (±0.08) | 16.87 C,a (±0.39) | 17.75 B,a (±0.82) |

| Element | A. farnesiana | A. pennatula | A. plurijuga | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 46.65 (±0.21) | 43.76 (±0.18) | 45.78 (±1.0) | |

| H | 6.70 (±0.14) | 6.89 (±0.29) | 6.95 (±0.34) | |

| Elementary analysis (%) | O | 46.06 (±0.24) | 48.95 (±0.32) | 46.97 (±1.20) |

| N | 0.42 (±0.14) | 0.31 (±0.14) | 0.21 (±0.09) | |

| S | 0.11 (±0.02) | 0.07 (±0.006) | 0.06 (±0.007) | |

| Ash microanalysis (ppm) | K | 105,019.30 | 150,391.90 | 150,536.02 |

| Ca | 102,885.96 | 73,275.93 | 101,960.59 | |

| P | 9238.77 | 6424.63 | 4400.24 | |

| Sr | 3069.60 | 2362.51 | 3245.48 | |

| Na | 2449.93 | 1390.54 | 8202.02 | |

| Mg | 1140.72 | 578.96 | 1436.26 | |

| S | 2017.05 | 836.61 | 966.02 | |

| Ba | 280.89 | 160.12 | 105.75 | |

| Li | 122.19 | 63.18 | 155.30 | |

| Fe | 112.84 | 103.61 | 195.65 | |

| B | 86.40 | 43.02 | 240.56 | |

| Si | 52.48 | 25.80 | 158.15 | |

| Al | 41.47 | 28.79 | 72.82 | |

| Cu | 41.71 | 26.58 | 41.57 | |

| Mn | 24.82 | 19.41 | 20.91 | |

| Zn | 15.13 | 13.31 | 14.34 | |

| Ni | 1.05 | 5.47 | ˂0.05 | |

| Cr | ˂0.05 | 0.54 | ˂0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pintor-Ibarra, L.F.; Alvarado-Flores, J.J.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G.; Alcaraz-Vera, J.V.; Herrera-Bucio, R.; Ruiz-García, V.M.; Moreno-Anguiano, O. Primary Constitution and Proximal Analysis of Three Fabaceae by the Thermogravimetric and Chemical Methods for Their Potential Use as Bioenergy. Processes 2025, 13, 3907. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123907

Pintor-Ibarra LF, Alvarado-Flores JJ, Rutiaga-Quiñones JG, Alcaraz-Vera JV, Herrera-Bucio R, Ruiz-García VM, Moreno-Anguiano O. Primary Constitution and Proximal Analysis of Three Fabaceae by the Thermogravimetric and Chemical Methods for Their Potential Use as Bioenergy. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3907. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123907

Chicago/Turabian StylePintor-Ibarra, Luis Fernando, José Juan Alvarado-Flores, José Guadalupe Rutiaga-Quiñones, Jorge Víctor Alcaraz-Vera, Rafael Herrera-Bucio, Víctor Manuel Ruiz-García, and Oswaldo Moreno-Anguiano. 2025. "Primary Constitution and Proximal Analysis of Three Fabaceae by the Thermogravimetric and Chemical Methods for Their Potential Use as Bioenergy" Processes 13, no. 12: 3907. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123907

APA StylePintor-Ibarra, L. F., Alvarado-Flores, J. J., Rutiaga-Quiñones, J. G., Alcaraz-Vera, J. V., Herrera-Bucio, R., Ruiz-García, V. M., & Moreno-Anguiano, O. (2025). Primary Constitution and Proximal Analysis of Three Fabaceae by the Thermogravimetric and Chemical Methods for Their Potential Use as Bioenergy. Processes, 13(12), 3907. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123907