1. Introduction

Continuous and stable drainage and production of CBM wells are the core prerequisites for ensuring high and stable production [

1,

2,

3]. Unplanned shutdowns caused by faults not only interrupt production, but also cause irreversible damage to reservoir permeability, significantly affecting the productivity of CBM wells [

4,

5,

6]. Fang Xiaojie [

7] conducted a comparative analysis of the relationship between the number of production interruptions and productivity and found that the daily gas production decreases to varying degrees after shutdown. Through experiments on coal–sand mixture intrusion into propped fractures, Zhang Xitu [

8] found that a shutdown has a significant impact on the permeability of the near end of propped fractures.

Previous studies have been carried out on the types and causes of fault-induced shutdowns. Zhang Yue [

9] pointed out that sand production leads to frequent shutdowns of CBM wells in thin interbedded formations. Based on the CBM production practice in the Hancheng area of the Ordos Basin, Yao Zheng [

10] found that coal–sand mixture causes downhole faults such as poor drainage, progressing cavity pump (PCP) leakage, and pump sticking. Based on on-site drainage feedback, Cai Wenbin [

11] found that coal–sand mixture mainly affects drainage from the pressure reduction stage to the gas production increase stage, and easily leads to pump sticking and pump burial. Han Guoqing [

12] found that the water production characteristics of CBM wells vary significantly in different production stages. Different water production characteristics affect the migration and sedimentation of coal–sand mixture, thereby influencing the shutdown cycle. Gas channeling easily induces shutdowns due to dry friction and cavitation of artificial lift equipment [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Previous studies have mostly focused on analyzing the causes of individual fault types and discussing corresponding prevention and control measures, without conducting differentiated research in combination with the production stages of coalbed methane (CBM) wells.

To clarify the types of shutdowns and their primary controlling factors across different production stages of coalbed methane (CBM) horizontal wells, this study focuses on 25 high-frequency shutdown horizontal wells in Huabei Oilfield—specifically shallow horizontal wells with a depth of less than 1200 m, which all commenced production between 2020 and 2025, had a daily gas production ranging from 3000 m

3/d to 12,000 m

3/d, and adopted the progressing cavity pump (PCP) as the mechanical production method. It comprehensively summarizes the fault types, root causes, and shutdown cycles of shutdowns, and based on the production stage division method proposed by Tao et al. (2018) [

1], reveals the stage differences in the main controlling factors of fault-induced shutdowns, and proposes stage-specific technical measures for shutdown prevention. This study is conducive to cost reduction and efficiency improvement throughout the life cycle of CBM horizontal wells.

2. Fault Types and Causes

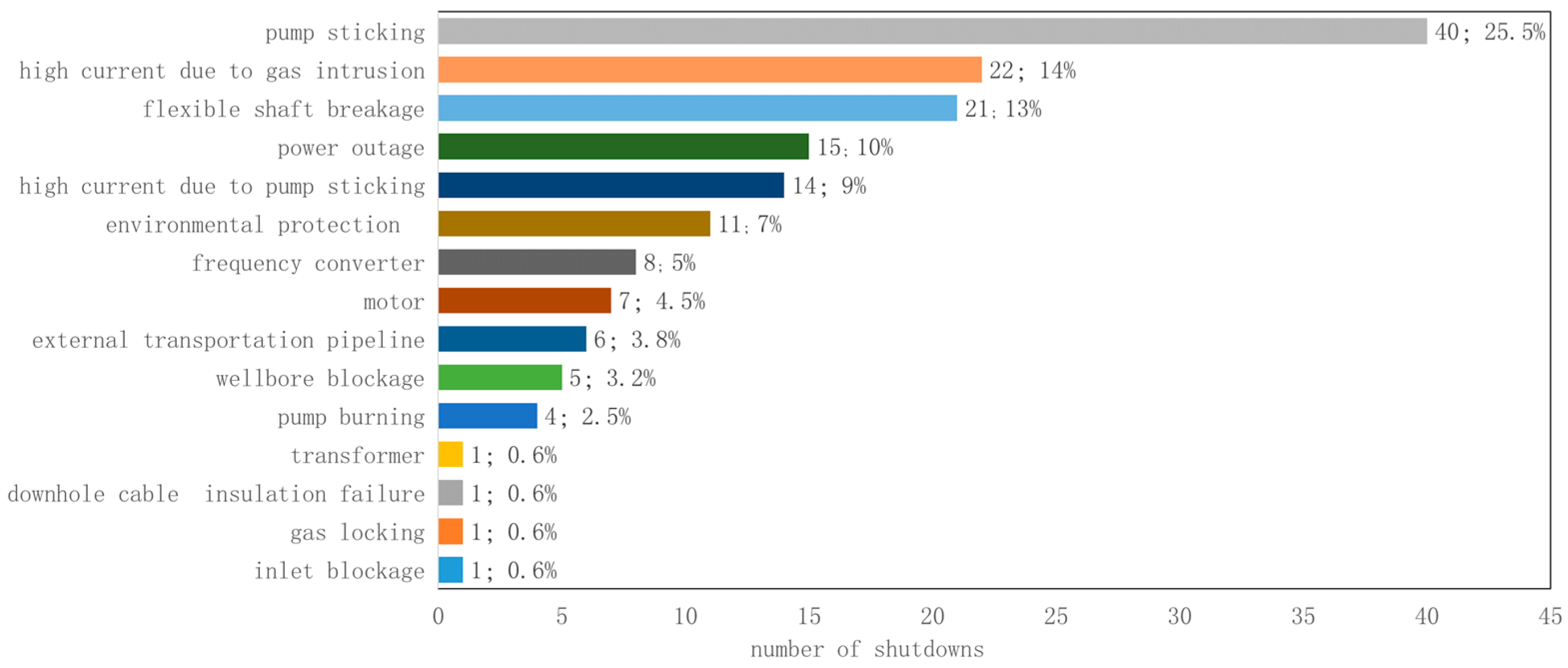

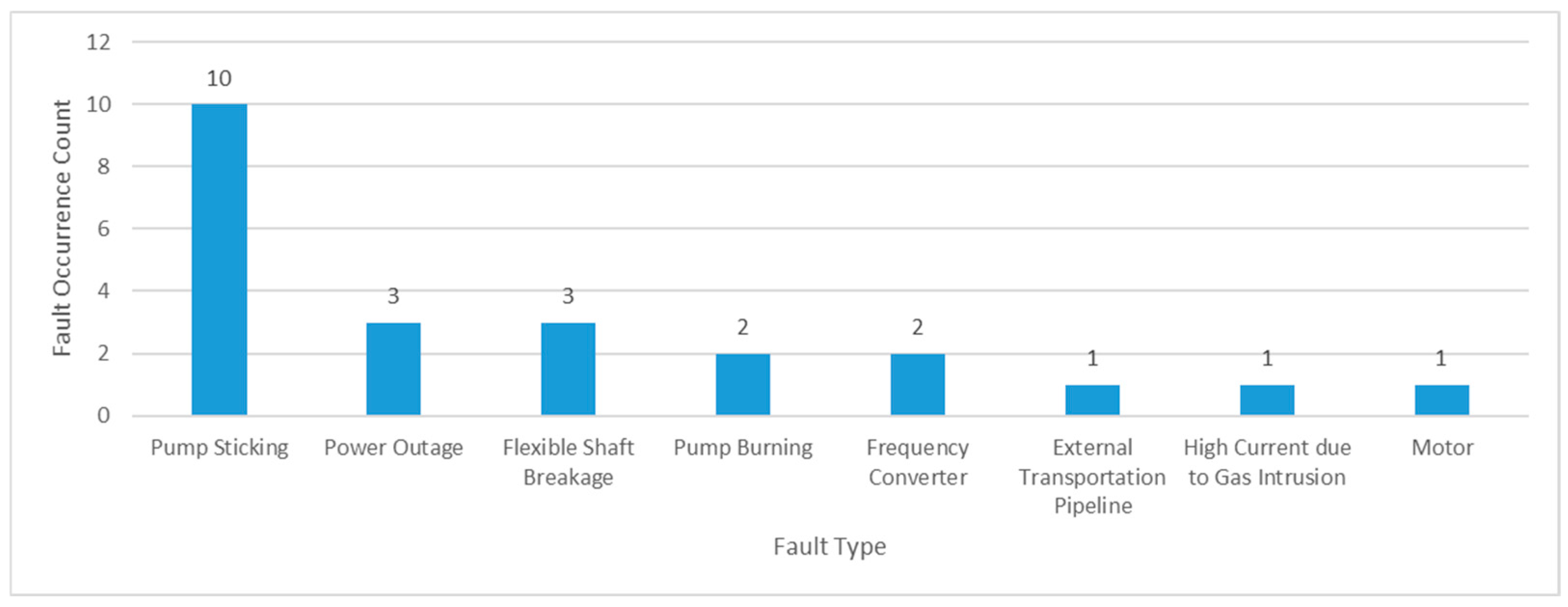

A total of 15 fault types and 157 shutdown incidents were counted from the pump inspection records. The number of shutdowns for different fault types is shown in

Figure 1. It can be seen from the figure that pump sticking is the most common fault type, followed by excessive current and flexible shaft breakage. According to the fault inducements, the 15 fault types are divided into four categories: coal–sand mixture-related faults, gas intrusion-related faults, supporting equipment faults, and other faults.

As shown in the classification diagram of different shutdown types (

Figure 2), coal–sand mixture-related issues are the core inducement of shutdowns, accounting for 52% of the total shutdowns. Continuous accumulation of coal–sand mixture in the wellbore can block the wellbore annulus, causing bottom-hole pressure buildup and thus reducing gas production. Wetted coal–sand mixture has strong adhesion and is easy to attach to the surface of the sand control screen at the liquid inlet, blocking the liquid inlet channel and preventing the annulus liquid from being discharged. As a result, the CBM well shuts down due to a continuous increase in bottom-hole pressure (see

Figure 3). Most of the coal–sand mixture entering the gas-sand anchor settles in the sand settling pipe at the bottom, but a small part of the coal–sand mixture is carried by the liquid phase and retained in the cavity of the PCP. With the increase in retained coal–sand mixture in the pump cavity, the rotation resistance of the flexible shaft increases, which easily causes jamming or current protection shutdown due to excessive current. The blocked coal–sand mixture is randomly distributed in the pump cavity, resulting in uneven stress on the flexible shaft of the PCP, which is prone to fatigue damage and fracture.

Gas intrusion is the second major cause of shutdowns, accounting for 22% of the total shutdowns. In horizontal wellbores, the gas–liquid two-phase flow pattern is pseudo-slug flow [

18,

19], which is characterized by gas slugs in the wellbore and liquid backflow at the bottom. At low gas–liquid ratios, gas enters the PCP in the form of bubbles; due to the low gas content, it has little impact on the PCP. At high gas–liquid ratios, the gas separation efficiency of the gas-sand anchor is low, and gas enters the pump cavity continuously, causing dry friction. The rubber stator of the PCP expands when heated under long-term dry friction, leading to excessive current or even pump burning and subsequent shutdown. When the gas content in the PCP is too high, the PCP cannot start due to gas locking.

During production, in addition to the main shutdowns caused by coal–sand mixture and gas intrusion, there are also shutdowns caused by supporting equipment faults (such as motor frequency converter damage, downhole cable insulation failure, and wellsite transformer faults) and other factors (such as power outages, external transportation pipeline pressure buildup, and environmental protection policies). These two types of shutdown factors are irrelevant to well conditions; they may occur in any well and have strong uncertainty.

3. Impact Degree of Faults

Analyzing the shutdown days of faults can characterize the impact degree of different faults on production. The actual fault handling time is easily affected by special working conditions, such as extended processing cycles of scarce accessories and inability to conduct on-site operations due to severe weather (e.g., heavy rain), resulting in significant random fluctuations in the single shutdown duration of the same fault type. Therefore, in this study, the total shutdown days of the same fault type were averaged to effectively eliminate such accidental factors and ensure that the analysis results are more consistent with the essential impact characteristics of the faults.

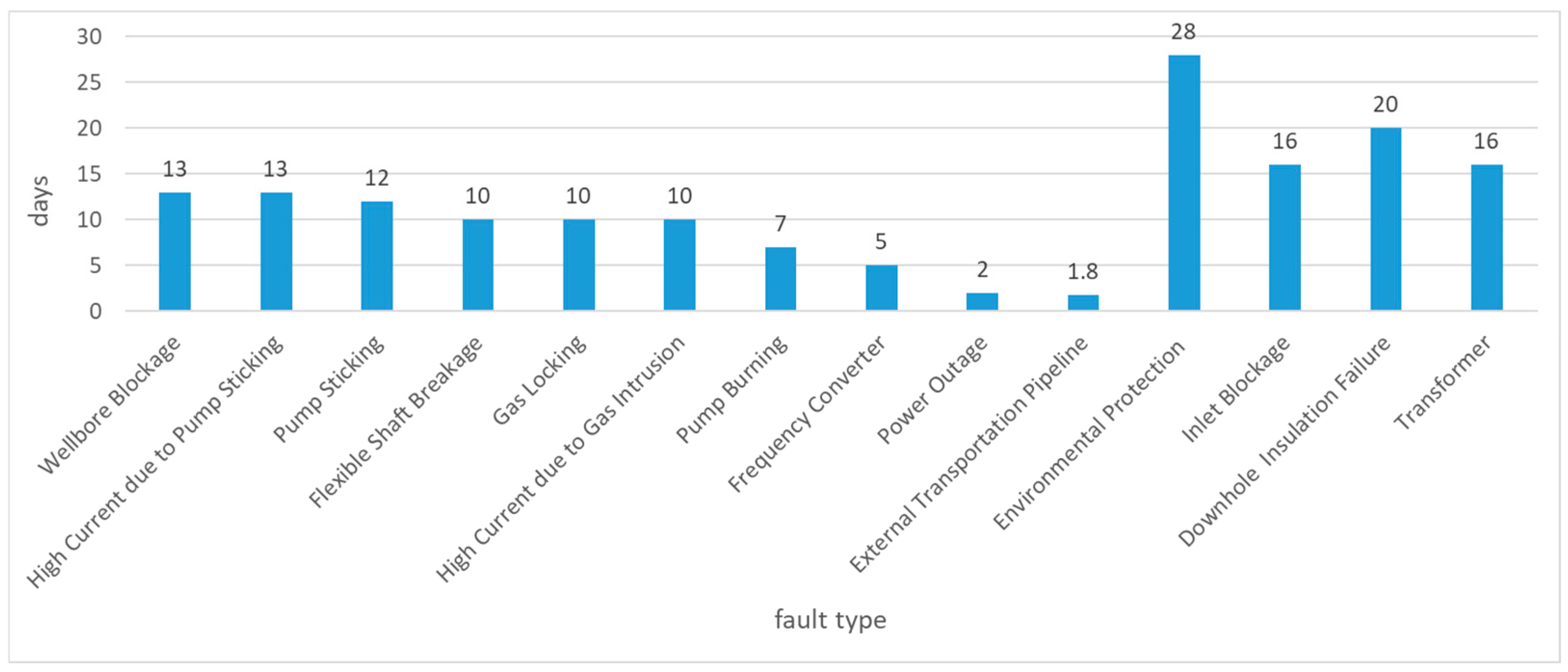

As shown in

Figure 4, the handling of faults caused by coal–sand mixture (e.g., wellbore blockage, pump sticking, and flexible shaft breakage) takes the longest time, which are 13 days, 12 days, and 10 days, respectively. After wellbore blockage and pump sticking occur, production resumption measures such as positive circulation well washing, reverse circulation well washing, and reinjection are usually adopted; if the above measures fail to eliminate the fault or a large amount of coal–sand mixture is determined to exist downhole, further sand washing operations are required. The fault elimination process is complex and time-consuming. The average shutdown time for gas locking and high current caused by gas intrusion is also as long as 10 days, but the shutdown time for pump burning faults is only 7 days. For pump burning faults, the PCP must be replaced immediately to resume the production of the CBM well, which saves the time required to pull out the pipe string and attempt production resumption. The replacement of damaged frequency converters involves the customization of accessories, with an average time of up to 5 days. Environmental protection issues result in the longest average shutdown duration, reaching 28 days. However, shutdowns caused by environmental protection issues all occur in the water drainage stage, which only affects the continuity of water drainage and does not directly affect the gas well production. Therefore, the impact of shutdowns caused by environmental protection issues on the production of CBM wells can be ignored. Inlet blockage, downhole cable insulation failure, and transformer faults each occurred only once, so their shutdown times are not representative.

4. Stage Differences of Faults

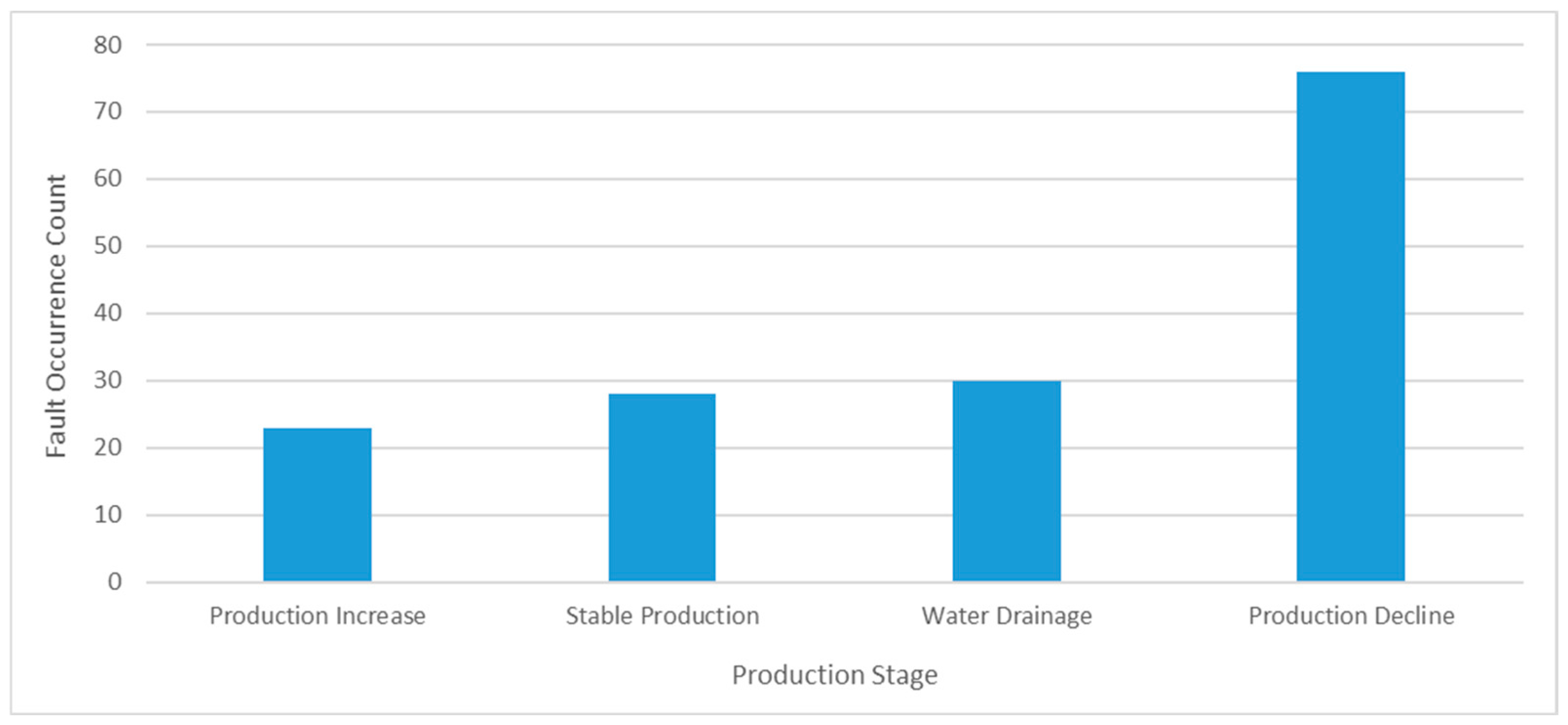

It can be seen from the number of faults in different production stages (

Figure 5) that the number of faults increases with the progress of production time. Among them, the production decline stage has the most faults, reaching 68 times, which is the most frequent among all fault types in terms of occurrence count.

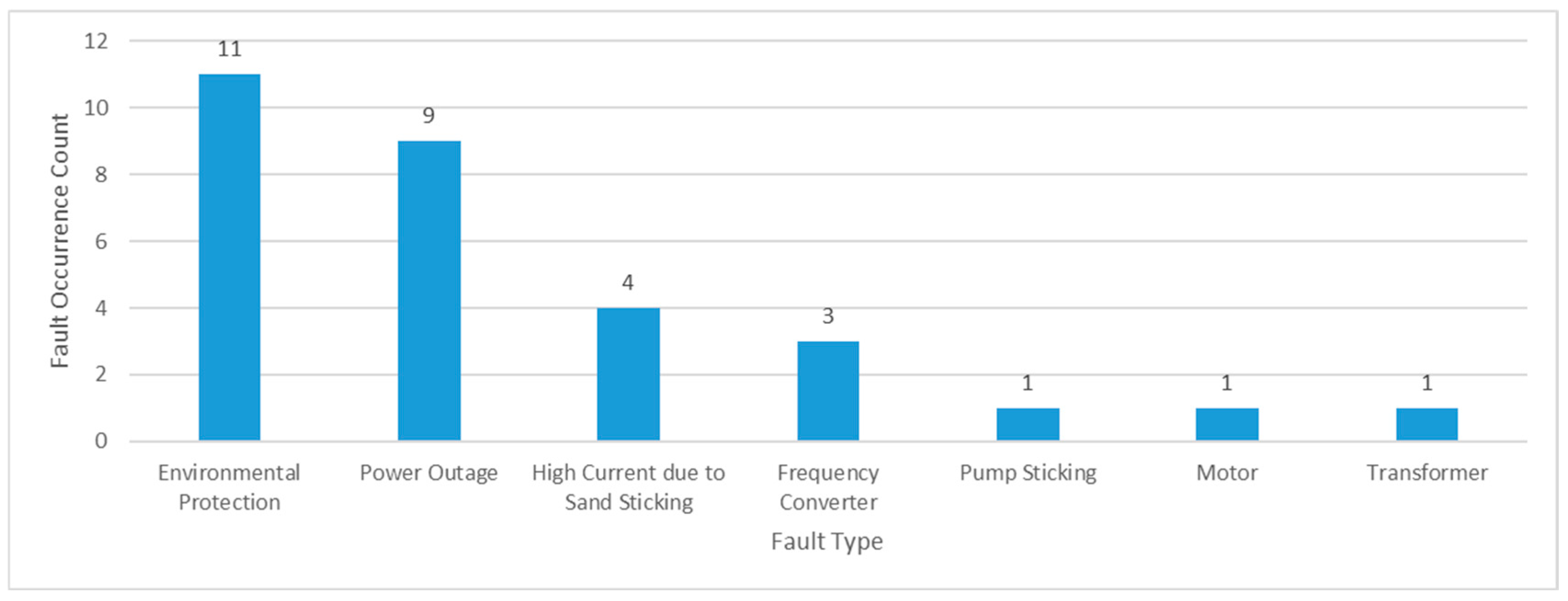

The number of fault occurrences in the water drainage stage is shown in

Figure 6. Supporting equipment such as frequency converters and transformers only failed five times, indicating that the operation site has strong logistics support capabilities. Shutdowns caused by environmental protection and power outages reached 20 times, which are the main causes of shutdowns in the water drainage stage. The three fault types of high current due to pump sticking and motor damage are all caused by coal–sand mixture, resulting in a total of eight shutdowns, accounting for only 5% of the total shutdowns. Since CBM wells have not yet entered stable gas production during the water drainage stage and no actual natural gas output is generated, shutdowns caused by factors such as environmental protection and power outages will not result in direct losses of natural gas production. Among the fault types induced by formation sand, high current due to pump sticking accounts for the largest proportion; such faults involve downhole operations and cause significant financial losses. Therefore, in the water drainage stage, the water drainage rate should be properly controlled to reduce coal–sand mixture detachment caused by velocity sensitivity.

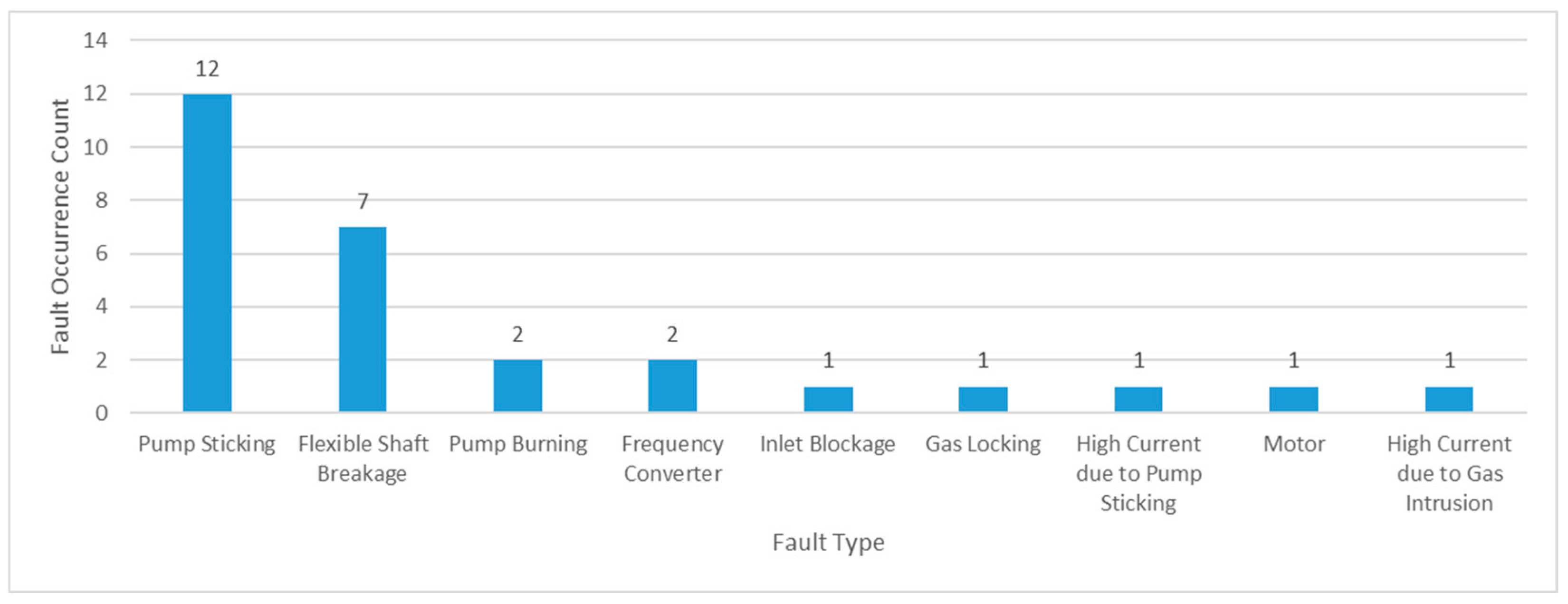

It can be clearly seen from the fault type diagram of the production increase stage (

Figure 7) that pump sticking is the main fault type causing shutdowns in this stage, followed by flexible shaft breakage; both are related to formation sand production. With the increase in gas production in the production increase stage, faults such as pump burning and high current caused by gas intrusion occur, but their proportion is small. In the stable production stage, faults such as pump sticking and flexible shaft breakage caused by formation sand production further increase, accounting for 68% of the total faults during the stable production period, while faults caused by gas intrusion only account for 17%. The gas production is high in the stable production period, but the number of faults caused by gas intrusion does not increase significantly. This is because the research objects are fault wells with high fault frequency; due to the impact of frequent operations, the duration of the stable production period is generally short. Faults that should ideally occur in the stable production period are classified into the production decline stage due to the actual low production. In the production increase stage, gas–water two-phase flow exists in the wellbore, and coal–sand mixture in the annulus is more likely to be carried to the pump. On the basis of controlling the bottom-hole pressure drop rate, downhole coal–sand mixture prevention technologies should be matched, and well washing operations should be carried out regularly to remove the accumulated coal–sand mixture in the wellbore.

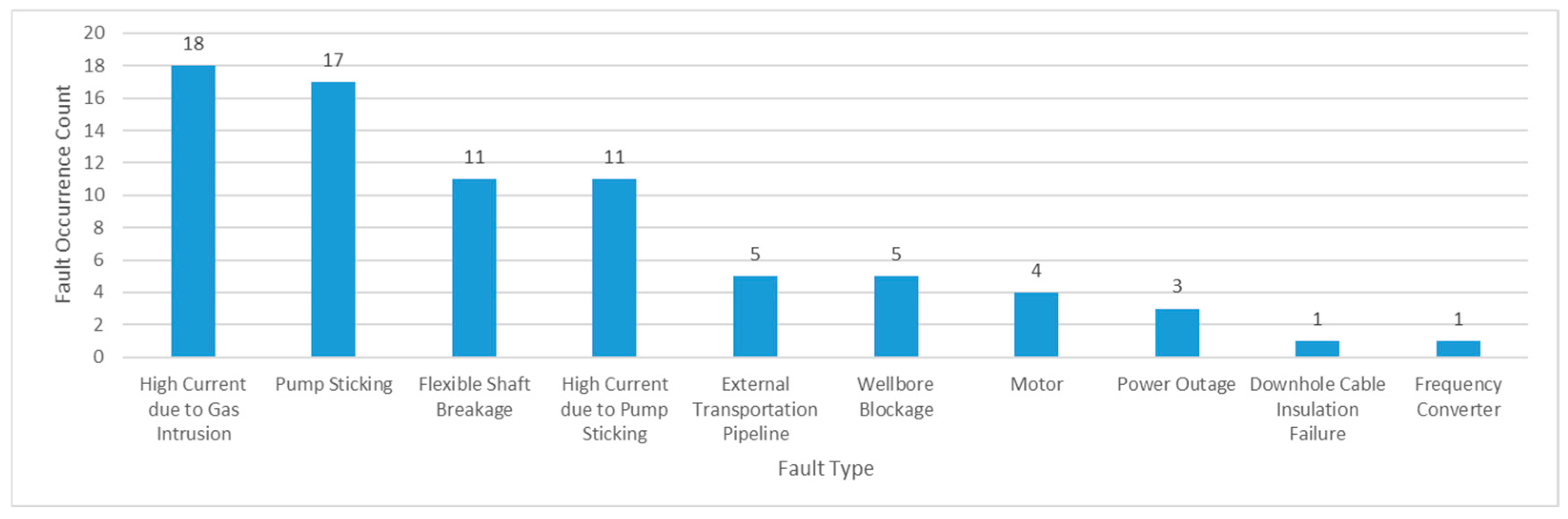

As the formation development enters the middle and late stages, the formation water production decreases significantly, the gas–liquid ratio increases, and gas intrusion problems worsen. Faults caused by gas intrusion also increase sharply. The fault type diagrams during the stable production period and the production decline stage are shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 respectively. As shown in

Figure 9, the number of faults caused by gas intrusion increases from 4 in the stable production period to 18. High current due to gas intrusion becomes the most frequent fault type in the production decline stage. Fault types caused by fracturing sand, such as pump sticking, flexible shaft breakage, high current, and wellbore blockage, account for 58% of the total fault types. Although this proportion is lower than that in the stable production period, they are still the main fault types. On the basis of coal–sand mixture prevention technologies, more efficient gas anchors should be developed to prevent gas intrusion.

5. Conclusions

For 25 CBM horizontal wells with high shutdown frequency in Huabei Oilfield, 15 types of shutdown faults (157 incidents) were identified, which are categorized into four types based on causes: coal–sand mixture -related issues are the core inducement (accounting for 52%), mainly causing wellbore blockage, pump sticking, and flexible shaft breakage; Gas intrusion is the second inducement (accounting for 22%), which easily causes dry friction or gas locking of the PCP under high gas–liquid ratio conditions; supporting equipment faults (accounting for 10%) and other issues (accounting for 20%) have lower contributions and are mostly irrelevant to well conditions.

The impact of faults on production varies significantly: wellbore blockage (13 days), pump sticking (12 days), and flexible shaft breakage (10 days) caused by coal–sand mixture, as well as high current due to gas intrusion (10 days), have the strongest interference; environmental protection issues (28 days) only exist in the water drainage stage and do not affect production; supporting equipment faults (2–5 days) have a short handling cycle and the least interference.

Shutdown faults exhibit obvious stage characteristics: in the water drainage stage, the main controlling factors are environmental protection and power outages, and the core downhole fault is high current due to pump sticking; in the production increase and stable production stages, benefiting from the initial drainage and pressure reduction in the reservoir, coal–sand mixture is extensively produced from the formation in the early stage, making coal–sand mixture-related issues dominant (accounting for 68% in the stable production stage), while gas intrusion faults account for less than 20%; in the production decline stage, as drainage and production proceed, the formation water production decreases significantly in the later stage, leading to a sharp surge in gas intrusion problems (high current due to gas intrusion is the most frequent), and the proportion of coal–sand mixture-related faults decreases to 58% but remains the main inducement.

This study clarifies the evolution law of faults throughout the life cycle, provides data support for stage-specific shutdown prevention, and can reduce reservoir damage and productivity loss, contributing to cost reduction and efficiency improvement of CBM horizontal wells.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. and B.F.; methodology, L.Z.; software, C.Z.; validation, L.Z., B.F. and C.W.; formal analysis, B.L.; investigation, G.H. and G.W.; resources, M.Q.; data curation, C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Z.; writing—review and editing, B.F.; visualization, B.L.; supervision, C.W.; project administration, M.Q.; funding acquisition, G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Liping Zhao, Bin Fan, Chunsheng Wu, Cong Zhang, Bin Liu, and Mengfu Qin were employed by the Shanxi CBM Exploration and Development Branch, PetroChina Huabei Oilfield Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Tao, J.J.; Li, Y.P.; Yang, C.L.; Zhang, J.B.; Shen, J. Drainage and extraction control and optimization of gas production in a high coal rank coalbed gas well in Southern Qinshui basin. Saf. Coal Mines 2018, 49, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, B.F.; Kang, Y.S.; Liu, N.; Sun, L.Z.; Gu, J.Y.; Sun, H.S. Influencing factors of drainage dynamics of CBM wells and primary drainage rate optimization in east Yunnan-western Guizhou area. J. China Coal Soc. 2018, 43, 1716–1727. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.D.; Shi, J.T.; Hao, P.L.; Wang, Y.C.; Cao, J.T.; Wang, T.; Fa, Q.W.; Zhang, Y.F. Study on optimal design of reasonable drainage system for deep coalbed methane (CBM) wells—Taking the Shenfu block in the eastern margin of the ordos basin as an example. Geol. Explor. 2024, 60, 850–862. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.A.; Cao, L.H.; Du, C.X. Study on CBM production mechanism and control theory of bottom-hole pressure and coal fines during CBM well production. J. China Coal Soc. 2014, 39, 1927–1931. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, H.G.; Zhu, G.H.; Wu, J. Formation conditions and main controlling factors of deep coalbed methane in Linxing area, eastern Ordos Basin. J. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2025, 36, 1603–1617. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.L.; Wang, Y.B.; Wang, L.; Zhao, S.H. Development characteristics of coal fines and their influence on production in Shizhuang Area of Qinshui Basin. Saf. Coal Mines 2023, 54, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.J.; Wu, C.F.; Liu, X.L.; Zhang, S.S.; Liu, N.N. Productivity characteristics and influencing factors of coalbed methane wells in Yuwang block of Laochang mining area in eastern Yunnan and western Guizhou provinces. J. Henan Polytech. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2020, 39, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.T.; Hu, S.Y.; Wu, X.; Li, G.F.; Feng, G.R.; Wang, Y.F.; Chen, Z.Y. Study on the dynamic influence law of coal fines invasion on propped fracture permeability. J. China Coal Soc. 2024, 49, 2338–2346. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.J.; Li, Y.W.; Wu, X.D.; Jiang, S.X.; Gu, F.; Cui, J.Y.; Gao, Y. Research on sand control in thin interbed CBM wells. Saf. Coal Mines 2024, 55, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.; Cao, D.Y.; Xiong, X.Y.; Wei, Y.C.; Wang, X.L.; Zhang, A.X. Forecast of coal fines-related downhole failures based on monitoring dynamometer card. J. China Coal Soc. 2015, 40, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.B.; Wang, J.L.; Zhang, Y.J.; Zhou, D.S.; Lei, X. Current status and prospects of deep coalbed methane (cbm) drainage technology. Coal Eng. 2025, 57, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Han, G.Q.; Ling, K.G.; Zhang, H. Smart de-watering and production system through real-time water level surveillance for coal-bed methane wells. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 31, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.F.; Wang, R.Y. Study on gas drilling technology and supporting technology for L-type horizontal well in Panhe Block. Coal Sci. Technol. 2019, 47, 132–137. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, R.H.; Huang, Z.W.; Liu, H.Y.; Liu, X.H.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.H. Improvement and field application of electric submersible screw pump lifting technology for horizontal wells in Qingcheng shale oil area. Drill. Prod. Technol. 2024, 47, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, L.P.; Jia, H.M.; Qin, M.F.; Zhang, W.S.; Ji, Y.B.; Yuan, S. Application of drainage technology for L-shaped coalbed methane horizontal well in Southern Qinshui Basin. Coal Sci. Technol. 2025, 53, 304–314. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, M.; Peng, J.; Ge, H.; Ji, W.; Li, X.; Wang, Q. Rock fabric of lacustrine shale and its influence on residual oil distribution in the Upper Cretaceous Qingshankou Formation, Songliao Basin. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 7151–7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Meng, M.; Deng, K.; Bao, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, X. A quick method for appraising pore connectivity and ultimate imbibed porosity in shale reservoirs. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.B.; Liu, Y.H.; Fan, H.C.; Luo, C.C.; Xu, M.J.; Wu, N.; Jiang, J.H.; Rui, J. Experimental Investigation of the Effect of Lateral Trajectory on Flow Stability in Horizontal Gas Wells. In Proceedings of the GOTECH, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 21–23 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Brito, R.; Pereyra, E.; Sarica, C. Effect of well trajectory on liquid removal in horizontal gas wells. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 156, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).