Study of the Oxidative Stability of Chia Oil (Salvia hispanica L.) at Various Concentrations of Alpha Tocopherol

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chia Seeds

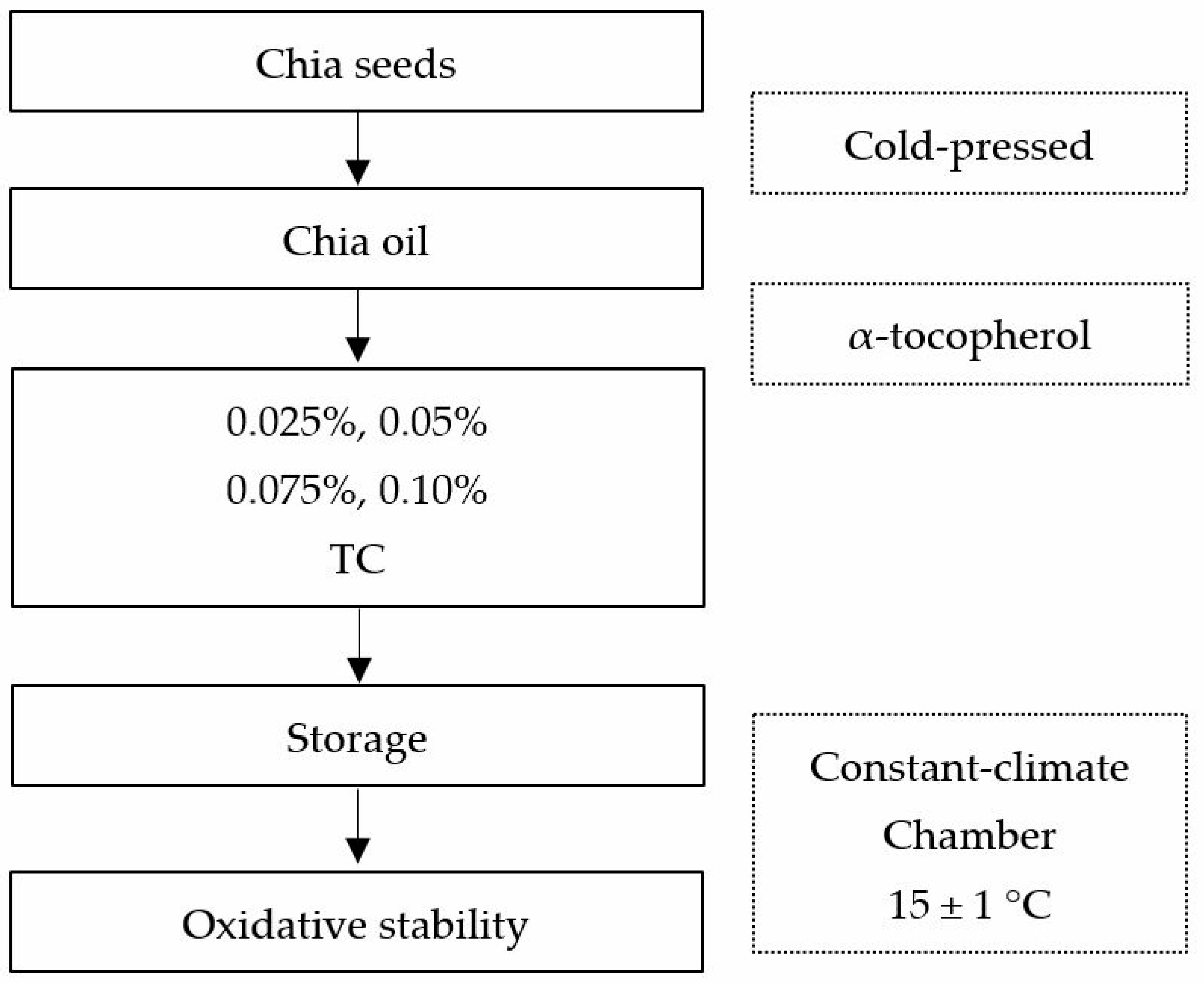

2.2. Experimental Design, Sample Preparation, and Environmental Controls

2.3. Antioxidant Addition and Storage Conditions

2.4. Accelerated Oxidation Analysis (Oxitest Reactor)

2.5. Peroxide Value

2.6. Faty Acid Determination

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Extraction Yield

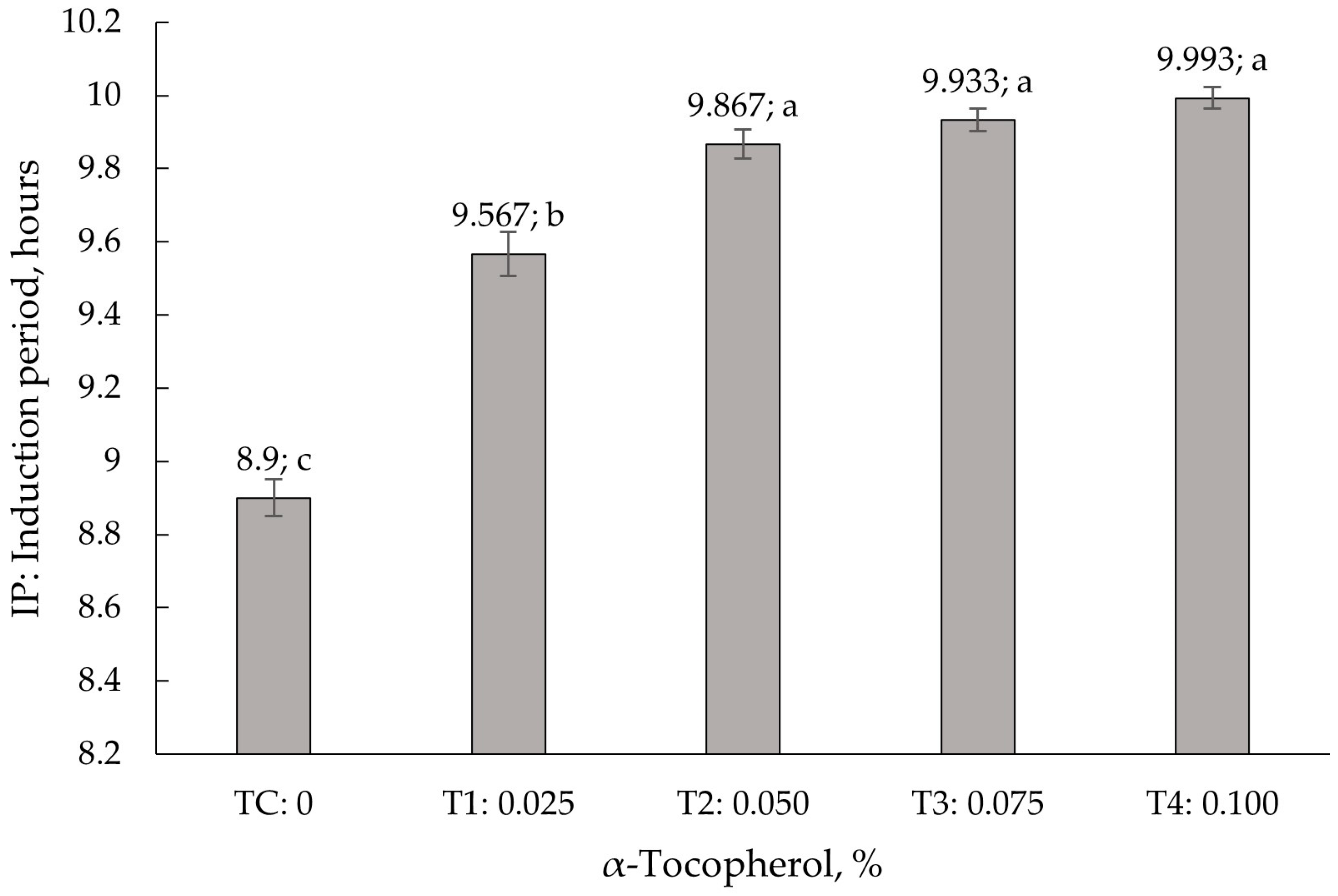

3.2. Accelerated Shelf-Life Study

3.3. Fatty Acid Profile

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaur, S.; Kumar, Y.; Singh, V.; Kaur, J.; Panesar, P.S. Cold Plasma Technology: Reshaping Food Preservation and Safety. Food Control 2024, 163, 110537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordón, M.G.; Meriles, S.P.; Ribotta, P.D.; Martinez, M.L. Enhancement of Composition and Oxidative Stability of Chia (Salvia hispanica L.) Seed Oil by Blending with Specialty Oils. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella-Martínez, C.; Gea-Quesada, A.; Sayas-Barberá, E.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.Á.; Fernández-López, J.; Viuda-Martos, M. Improving the Lipid Profile of Beef Burgers Added with Chia Oil (Salvia hispanica L.) or Hemp Oil (Cannabis sativa L.) Gelled Emulsions as Partial Animal Fat Replacers. LWT 2022, 161, 113416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariutti, L.R.B.; Rebelo, K.S.; Bisconsin-Junior, A.; de Morais, J.S.; Magnani, M.; Maldonade, I.R.; Madeira, N.R.; Tiengo, A.; Maróstica, M.R.; Cazarin, C.B.B. The Use of Alternative Food Sources to Improve Health and Guarantee Access and Food Intake. Food Res. Int. 2021, 149, 110709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.; Cabrera, M.C.; Olivero, R.; del Puerto, M.; Terevinto, A.; Saadoun, A. The Incorporation of Chia Seeds (Salvia hispanica L.) in the Chicken Diet Promotes the Enrichment of Meat with n-3 Fatty Acids, Particularly EPA and DHA. Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4, 100416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa Özcan, M.; Al-Juhaimi, F.Y.; Mohamed Ahmed, I.A.; Osman, M.A.; Gassem, M.A. Effect of Different Microwave Power Setting on Quality of Chia Seed Oil Obtained in a Cold Press. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczyński, B.; Kobus-Cisowska, J.; Taczanowski, M.; Kmiecik, D.; Gramza-Michałowska, A. The Chemical Composition and Nutritional Value of Chia Seeds—Current State of Knowledge. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L.G.; Bordignon Junior, I.J.; Vieira da Silva, R.; Mossmann, J.; Reinehr, C.O.; Brião, V.B.; Colla, L.M. Processed Cheese with Inulin and Microencapsulated Chia Oil (Salvia hispanica). Food Biosci. 2020, 37, 100731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marco, A.E.; Ixtaina, V.Y.; Tomás, M.C. Effect of Ligand Concentration and Ultrasonic Treatment on Inclusion Complexes of High Amylose Corn Starch with Chia Seed Oil Fatty Acids. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 136, 108222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.L.; Martínez, F.P.; Ferreira, S.B.; Kaiser, C.R. A Complete Evaluation of Thermal and Oxidative Stability of Chia Oil. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 130, 1307–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez Hrnčič, M.; Ivanovski, M.; Cör, D.; Knez, Ž. Chia Seeds (Salvia hispanica L.): An Overview—Phytochemical Profile, Isolation Methods, and Application. Molecules 2019, 25, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goergen, P.C.H.; Lago, I.; Scheffel, L.G.; Rossato, I.G.; Roth, G.F.M.; Durigon, A.; Pohlmann, V. Development of Chia Plants in Field Conditions at Different Sowing-Date. Comun. Sci. 2022, 13, e3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xingú López, A.; González Huerta, A.; De La Cruz Torrez, E.; Sangerman Jarquín, D.M.; Orozco De Rosas, G.; Arriaga, M.R. Chía (Salvia hispanica L.) Situación Actual y Tendencias Futuras. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2017, 8, 1619–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandán, J.P.; Izquierdo, N.; Acreche, M.M. Oil and Protein Concentration and Fatty Acid Composition of Chia (Salvia hispanica L.) as Affected by Environmental Conditions. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 177, 114496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Kim, I.; Jung, S.; Lee, J. Oxidative Stability of Chia Seed Oil and Flax Seed Oil and Impact of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) and Garlic (Allium cepa L.) Extracts on the Prevention of Lipid Oxidation. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2021, 64, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettel, V.; Hitzmann, B. Applications of Chia (Salvia hispanica L.) in Food Products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 80, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizones Ruiz-Henestrosa, V.M.; Ribourg, L.; Kermarrec, A.; Anton, M.; Pilosof, A.; Viau, M.; Meynier, A. Emulsifiers Modulate the Extent of Gastric Lipolysis during the Dynamic in Vitro Digestion of Submicron Chia Oil/Water Emulsions with Limited Impact on the Final Extent of Intestinal Lipolysis. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 124, 107336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Candela, I.; Gomez-Caturla, J.; Cardona, S.C.; Lora-García, J.; Fombuena, V. Novel Compatibilizers and Plasticizers Developed from Epoxidized and Maleinized Chia Oil in Composites Based on PLA and Chia Seed Flour. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 173, 111289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C. Consumo de Aceites Vegetales y el Comportamiento del Nivel Plasmático de Vitamina E en Población Adulta: Revisión de Literatura; Pontificia Universidad Javeriana: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020; pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Doert, M.; Grebenteuch, S.; Kroh, L.W.; Rohn, S. A Ternary System of α-Tocopherol with Phosphatidylethanolamine and l-Ascorbyl Palmitate in Bulk Oils Provides Antioxidant Synergy through Stabilization and Regeneration of α-Tocopherol. Food Chem. 2022, 391, 133084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, I.; Hussain, N.; Coorey, R.; Ghani, M.A. Optimization and Characterization of Chia Seed (Salvia hispanica L.) Oil Extraction Using Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 45, 101430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzaneda, F. Evaluación de La Producción de Dos Variedades de Chia (Salvia hispánica L.), En Dos Densidades de Siembra. Apthapi 2015, 1, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Čechovičienė, I.; Kazancev, K.; Hallmann, E.; Sendžikienė, E.; Kruk, M.; Viškelis, J.; Tarasevičienė, Ž. Supercritical CO2 and Conventional Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Different Cultivars of Blackberry (Rubus fruticosus L.) Pomace. Plants 2024, 13, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoss, K.; Glavač, N.K. Supercritical CO2 Extraction vs. Hexane Extraction and Cold Pressing: Comparative Analysis of Seed Oils from Six Plant Species. Plants 2024, 13, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homroy, S.; Chopra, R.; Singh, P.K.; Dhiman, A.; Chand, M.; Talwar, B. Role of Encapsulation on the Bioavailability of Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Zhong, H.J.; Ambigaipalan, P. Antioxidants: Regulatory Status. In Bailey’s Industrial Oil and Fat Products; Shahidi, F., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-0-471-38460-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kolnik, S.; Wood, T. Role of Vitamin E in Neonatal Neuroprotection: A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Life 2022, 12, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Mu, Z.; Lv, X.; Wang, Z.; Dong, A.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, H. A Review on Improving the Oxidative Stability of Pine Nut Oil in Extraction, Storage, and Encapsulation. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskoś, K.; Waligórski, P.; Pisulewska, E.; Janowiak, F.; Sadura-Berg, I.; Czyczyło-Mysza, I.M. Herbal Maceration Modulates Fatty Acid Profile of Cold-Pressed Oils and Preserves Antioxidant Activity during Long-Term Storage. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 38592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.; Ramos, M.; Silva, M.; Briceño, J.; Álvarez, M. Effect of the Temperature Prior to Extraction on the Yield and Fatty Acid Profile of Morete Oil (Mauritia flexuosa L. f.). La Granja 2022, 35, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musakhanian, J.; Rodier, J.-D.; Dave, M. Oxidative Stability in Lipid Formulations: A Review of the Mechanisms, Drivers, and Inhibitors of Oxidation. AAPS PharmSciTech 2022, 23, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, F.S.; Tekin-Cakmak, Z.H.; Karasu, S.; Aksoy, A.S. Oxidative Stability of the Salad Dressing Enriched by Microencapsulated Phenolic Extracts from Cold-Pressed Grape and Pomegranate Seed Oil by-Products Evaluated Using OXITEST. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e57220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, M.; Pitirollo, O.; Ornaghi, P.; Corradini, C.; Cavazza, A. Valorization of Agro-Industrial Byproducts: Extraction and Analytical Characterization of Valuable Compounds for Potential Edible Active Packaging Formulation. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 33, 100900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Mettodo Oficial 981.12. pH of Acidified Foods First; AOAC: Rockville, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tirado, D.F.; Montero, P.M.; Acevedo, D. Estudio Comparativo de Métodos Empleados Para La Determinación de Humedad de Varias Matrices Alimentarias. Inf. Tecnológica 2015, 26, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Method 940.28 Fatty Acids (Free) in Crude and Refined Oils; AOAC: Rockville, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, A. NTE INEN 38: Grasas y Aceites Comestibles: Determinación de La Acidez; Instituto Ecuatoriano de Normalización (INEN): Quito, Ecuador, 1973; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ellefson, W.C. Fat Analysis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 299–314. ISBN 978-3-319-45776-5. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo, W.; Quinteros, M.F.; Carpio, C.; Morales, D.; VÁsquez, G.; Álvarez, M.; Silva, M. Identification of Fatty Acids in Sacha Inchi Oil (Cursive Plukenetia Volubilis L.) from Ecuador. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2018, 11, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, M.D.; Magallanes, L.M.; Grosso, N.R.; Pramparo, M.d.C.; Gayol, M.F. Optimisation of Omega-3 Concentration and Sensory Analysis of Chia Oil. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 154, 112635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Nadeem, M.; Imran, M.; Khan, M.K.; Mushtaq, Z.; Asif, M.; Din, A. Effect of Microcapsules of Chia Oil on Ømega-3 Fatty Acids, Antioxidant Characteristics and Oxidative Stability of Butter. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, M.; Carpio, C.; Morales, D.; Álvarez, M.; Silva, S.; Carrillo, W. Content of Nutrients Component and Fatty Acids in Chia Seeds (Salvia hispanica L.) Cultivated in Ecuador. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2018, 11, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, H. A Systematical Review of Processing Characteristics of Chia Seed: Changes in Physicochemical Properties and Structure. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 103813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, R.V.; Leyes, E.A.R.; González Canavaciolo, C.V.L.; López Hernández, C.O.D.; Rivera Amita, M.M.; González Sanabia, M.L. Características Preliminares Del Aceite de Semillas de Salvia hispanica L. Cultivadas En Cuba. Rev. Cuba. Plantas Med. 2013, 18, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, R.F.M.; El-Anany, A.M. Physico-Chemical Characteristics, Nutritional Quality, and Oxidative Stability of Cold-Pressed Chia Seed Oil, Date Palm Seed Oil, along with Their Binary Mixtures. Cogent Food Agric. 2025, 11, 2466061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabni, A.; Bañares, C.; Torres, C.F. Study of the Oxidative Stability via Oxitest and Rancimat of Phenolic-Rich Olive Oils Obtained by a Sequential Process of Dehydration, Expeller and Supercritical CO2 Extractions. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1494091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Superti, F.; Russo, R. Alpha-Lipoic Acid: Biological Mechanisms and Health Benefits. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nain, C.W.; Berdal, G.; Thao, P.T.P.; Mignolet, E.; Buchet, M.; Page, M.; Larondelle, Y. Green Tea Extract Enhances the Oxidative Stability of DHA-Rich Oil. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsena, Y.P.; Vongsvivut, J.; Adhikari, R.; Adhikari, B. Physicochemical and Thermal Characteristics of Australian Chia Seed Oil. Food Chem. 2017, 228, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodoira, R.M.; Penci, M.C.; Ribotta, P.D.; Martínez, M.L. Chia (Salvia hispanica L.) Oil Stability: Study of the Effect of Natural Antioxidants. LWT 2017, 75, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, M.C.; Favati, F.; Di Cairano, M.; Galgano, F.; Labella, R.; Scarpa, T.; Condelli, N. Shelf-Life Evaluation and Nutraceutical Properties of Chia Seeds from a Recent Long-Day Flowering Genotype Cultivated in Mediterranean Area. LWT 2018, 87, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefla, K.; Ruales, J. Diseño de Una Planta Para La Extracción de Aceite Vegetal Comestible de Las Semillas de Chía (Salvia Hispanical) Mediante Prensado. Ph.D. Thesis, Escuela Politécnica Nacional, Quito, Ecuador, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Frolova, Y.; Sobolev, R.; Kochetkova, A. Antioxidant Activity and Oxidative Stability of Flaxseed and Its Processed Products: A Review. Science 2025, 7, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiotto, E.N.; Julio, L.M.; Ixtaina, V.Y. Natural Antioxidants in the Preservation of Omega-3-Rich Oils: Applications in Bulk, Emulsified, and Microencapsulated Chia, Flaxseed, and Sacha Inchi Oils. Phytochem. Rev. 2025, 24, 6139–6167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Hwang, H. Understanding the Oxidation of Hemp Seed Oil and Improving Its Stability by Encapsulation into Protein Microcapsules. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 6321–6334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmiecik, D.; Fedko, M.; Siger, A.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł. Nutritional Quality and Oxidative Stability during Thermal Processing of Cold-Pressed Oil Blends with 5:1 Ratio of Ω6/Ω3 Fatty Acids. Foods 2022, 11, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-K.; Cai, D.-J.; Zhao, H.-Y.; Ma, Y.-X.; Cai, X.-S.; Liu, H.-M.; Zhang, R.-Y. Factors Contributing to High Oxidative Stability in Oil from Long-Term Stored Tiger Nut (Cyperus esculentus L.): Endogenous Components. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2025, 114, 102792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, W.A.; Srivastava, K.; Nasibullah, M.; Khan, M.F. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): Sources, Generation, Disease Pathophysiology, and Antioxidants. Discov. Chem. 2025, 2, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatierra-Pajuelo, Y. Optimization of the Nutritional, Textural and Sensorial Characteristics of Cookies Enriched with Chia (Salvia hispánica) and Oil Extracted from Tarwi (Lupinus mutabilis). Sci. Agropecu. 2019, 10, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.-A.; Lee, I.-T.; Tan, C.X.; Wang, S.-T.; Praveen, K.; Lee, W.-J. Dietary Strategies for Optimizing Omega-3 Fatty Acid Intake: A Nutrient Database-Based Evaluation in Taiwan. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1661702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.E.; Lee, J.-S.; Lee, H.G. α-Tocopherol-Loaded Multi-Layer Nanoemulsion Using Chitosan, and Dextran Sulfate: Cellular Uptake, Antioxidant Activity, and in Vitro Bioaccessibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254, 127819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duché, G.; Sanderson, J.M. The Chemical Reactivity of Membrane Lipids. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 3284–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, W.W.; Harwood, J.L. Oxidation of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids to Produce Lipid Mediators. Essays Biochem. 2020, 64, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Seeds Used (g) | Oil Extracted (g) | Oil Extraction Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 16,000 | 3900 | 24.37 |

| 16,200 | 4000 | 24.69 |

| 17,680 | 4250 | 24.03 |

| Mean ± standard deviation for 3 replicates | 24.42 ± 2.18 | |

| Physicochemical Parameter | Control Treatment, CT | With 0.05% α-Tocopherol, T2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t = 0 Months | t = 15 Months | t = 0 Months | t = 15 Months | |

| Moisture (%) | 0.116 ± 0.015 | 0.860 ± 0.006 | 0.067 ± 0.003 | 0.176 ± 0.004 |

| Hydrogen potential (pH) | 4.560 ± 0.036 | 3.070 ± 0.070 | 4.200 ± 0.050 | 3.883 ± 0.015 |

| Acidity index (% OA) | 0.308 ± 0.056 | 0.509 ± 0.007 | 0.279 ± 0.004 | 0.465 ± 0.005 |

| Peroxide value (meq O2/Kg) | 3.460 ± 0.159 | 10.267 ± 0.115 | 2.042 ± 0.010 | 5.543 ± 0.004 |

| Compound Number | Common Name | Abbreviation | [40] | [49] | [50] | [59] | Control Oil, 0 Months | Control Oil, 15 Months | 0.05% α-Tocopherol, 15 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Palmitic acid | C16:0 | 7.226 | 7.22 | 7.46 | 8.54 | 7.23 ± 0.14 a | 8.34 ± 0.03 b | 8.60 ± 0.10 b |

| 2 | Stearic acid | C18:0 | 2.91 | 3.54 | - | 3.37 | 2.22 ± 0.16 a | 2.80 ± 0.02 b | 2.56 ± 0.06 b |

| 3 | Oleic acid | C18:1n9c | 7.395 | 7.10 | 7.18 | 10.24 | 5.61 ± 0.25 b | 6.26 ± 0.03 a | 6.10 ± 0.01 a |

| 4 | Linoleic acid | C18:2n6c | 19.708 | 18.74 | 20.1 | 18.69 | 19.39 ± 0.17 a | 17.88 ± 0.06 b | 17.71 ± 0.07 b |

| 5 | Linolenic acid | C18:3n3 | 62.76 | 63.23 | 61.8 | 54.08 | 65.55 ± 0.09 a | 64.72 ± 0.07 c | 65.03 ± 0.19 b |

| Saturated fatty acids | 9.45 ± 0.30 a | 11.14 ± 0.05 b | 11.16 ± 0.12 b | ||||||

| Monounsaturated fatty acids | 5.61 ± 0.25 b | 6.26 ± 0.03 a | 6.10 ± 0.01 a | ||||||

| Polyunsaturated fatty acids | 84.95 ± 0.08 a | 82.60 ± 0.05 b | 82.74 ± 0.12 b | ||||||

| Ratio of saturated to unsaturated fatty acids | 0.10 ± 0.01 a | 0.13 ± 0.01 b | 0.13 ± 0.01 b | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Briceño, J.; Vásquez, C.; Guayta, J.; Ramírez, C.; Altuna, J.; Silva, M. Study of the Oxidative Stability of Chia Oil (Salvia hispanica L.) at Various Concentrations of Alpha Tocopherol. Processes 2025, 13, 3887. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123887

Briceño J, Vásquez C, Guayta J, Ramírez C, Altuna J, Silva M. Study of the Oxidative Stability of Chia Oil (Salvia hispanica L.) at Various Concentrations of Alpha Tocopherol. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3887. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123887

Chicago/Turabian StyleBriceño, Jorge, Carlos Vásquez, Janeth Guayta, Carlos Ramírez, José Altuna, and Mónica Silva. 2025. "Study of the Oxidative Stability of Chia Oil (Salvia hispanica L.) at Various Concentrations of Alpha Tocopherol" Processes 13, no. 12: 3887. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123887

APA StyleBriceño, J., Vásquez, C., Guayta, J., Ramírez, C., Altuna, J., & Silva, M. (2025). Study of the Oxidative Stability of Chia Oil (Salvia hispanica L.) at Various Concentrations of Alpha Tocopherol. Processes, 13(12), 3887. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123887