Numerical Simulation Study of Air Flotation Zone of Horizontal Compact Swirling Flow Air Flotation Device

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model Development

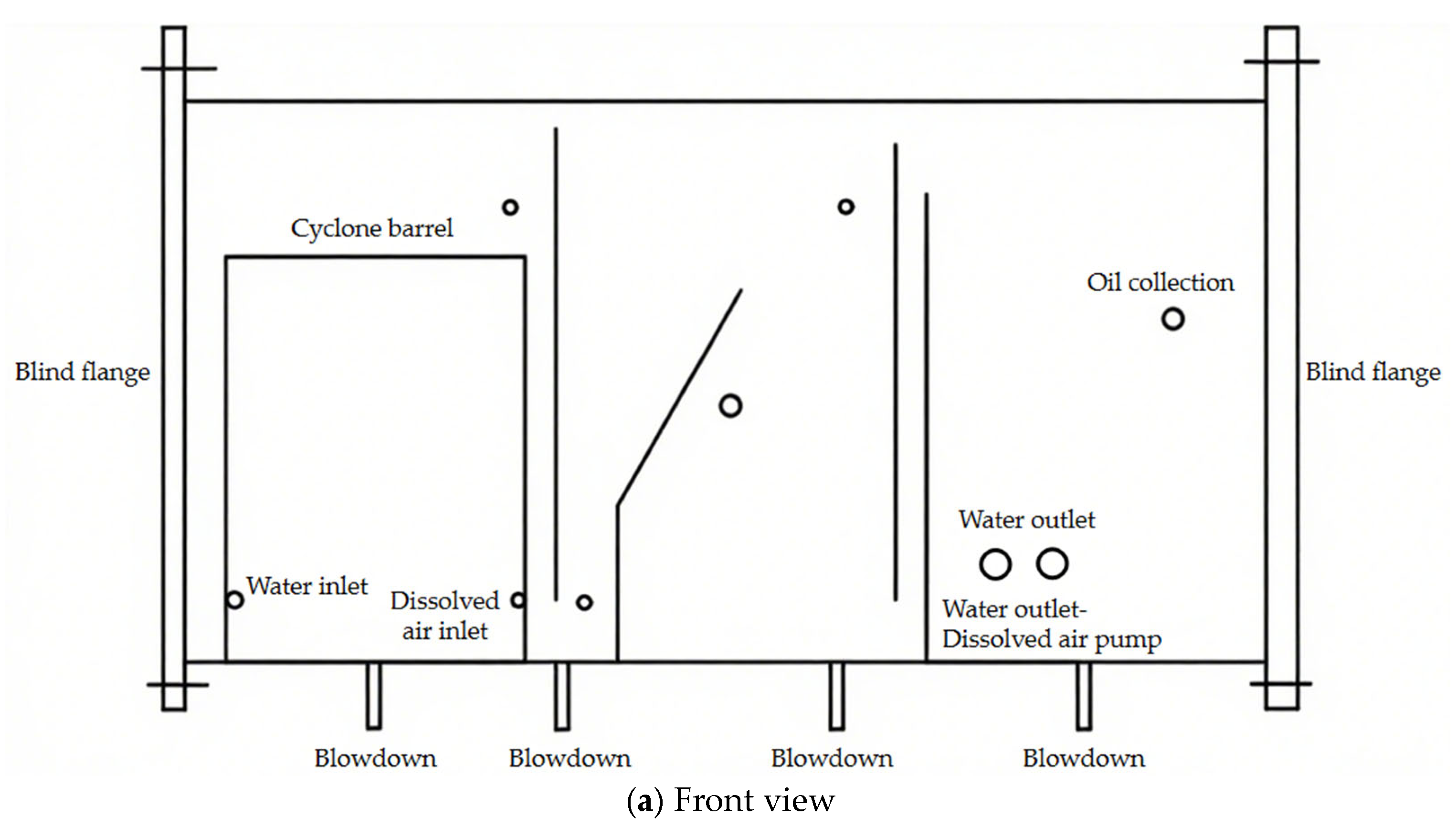

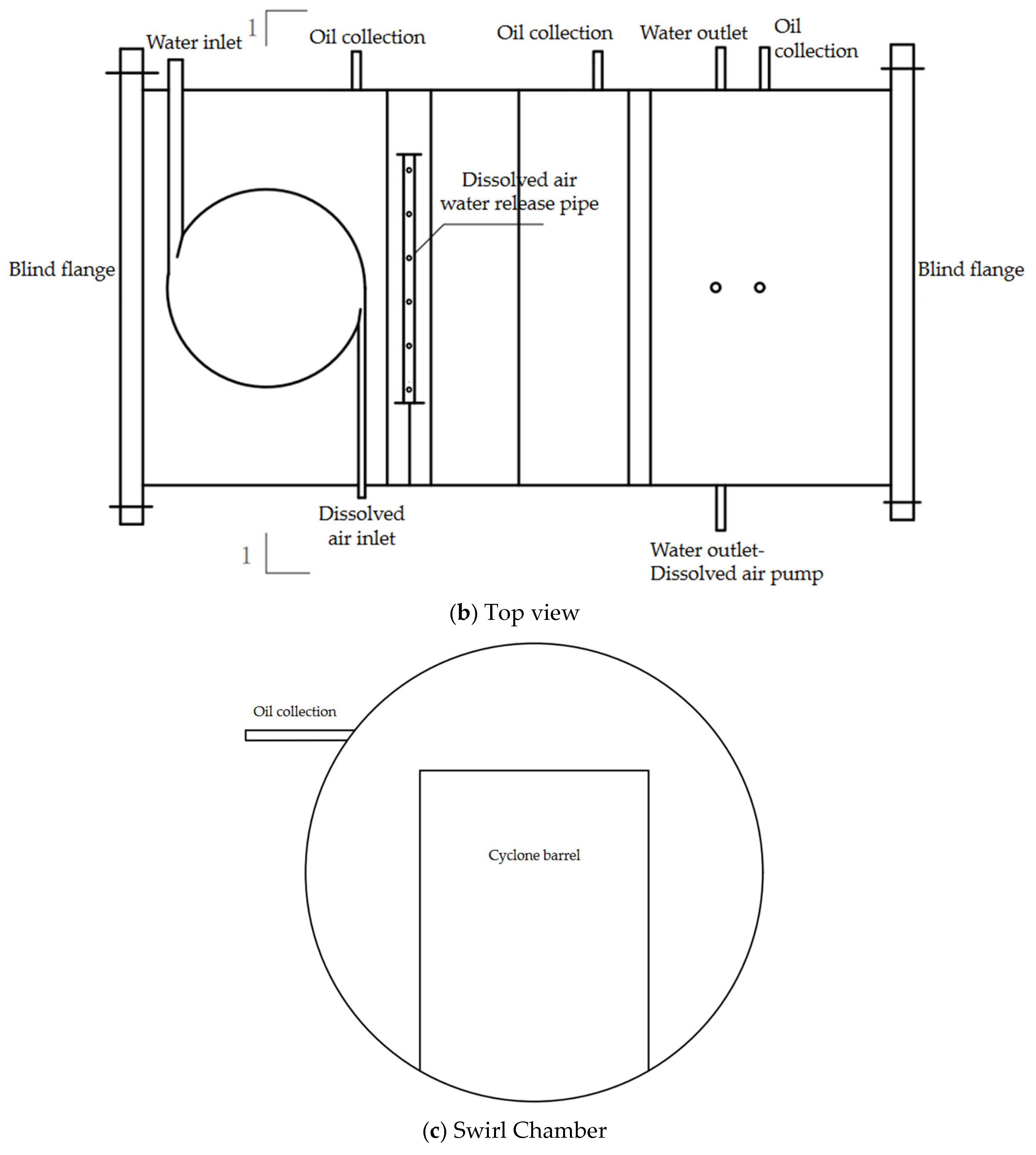

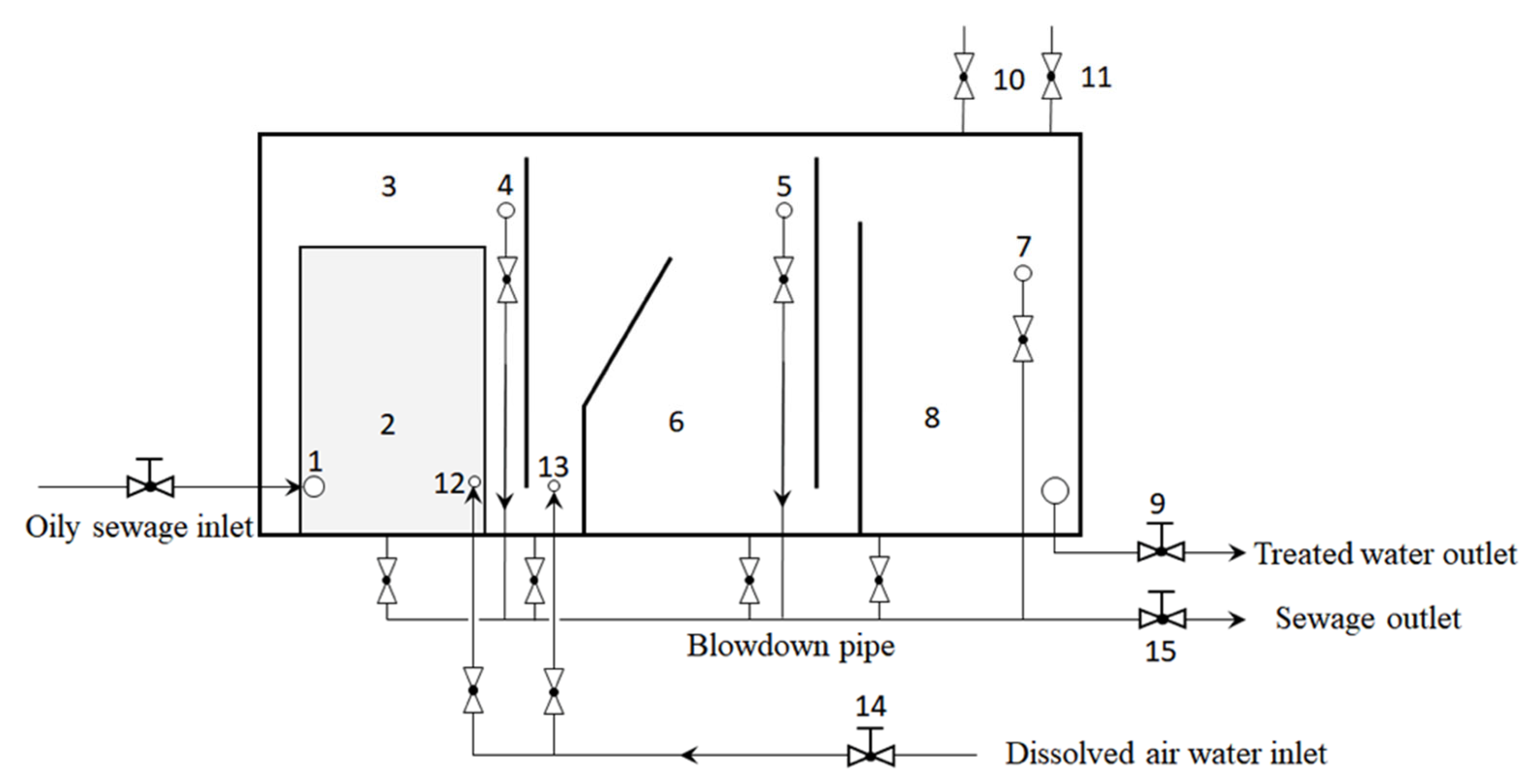

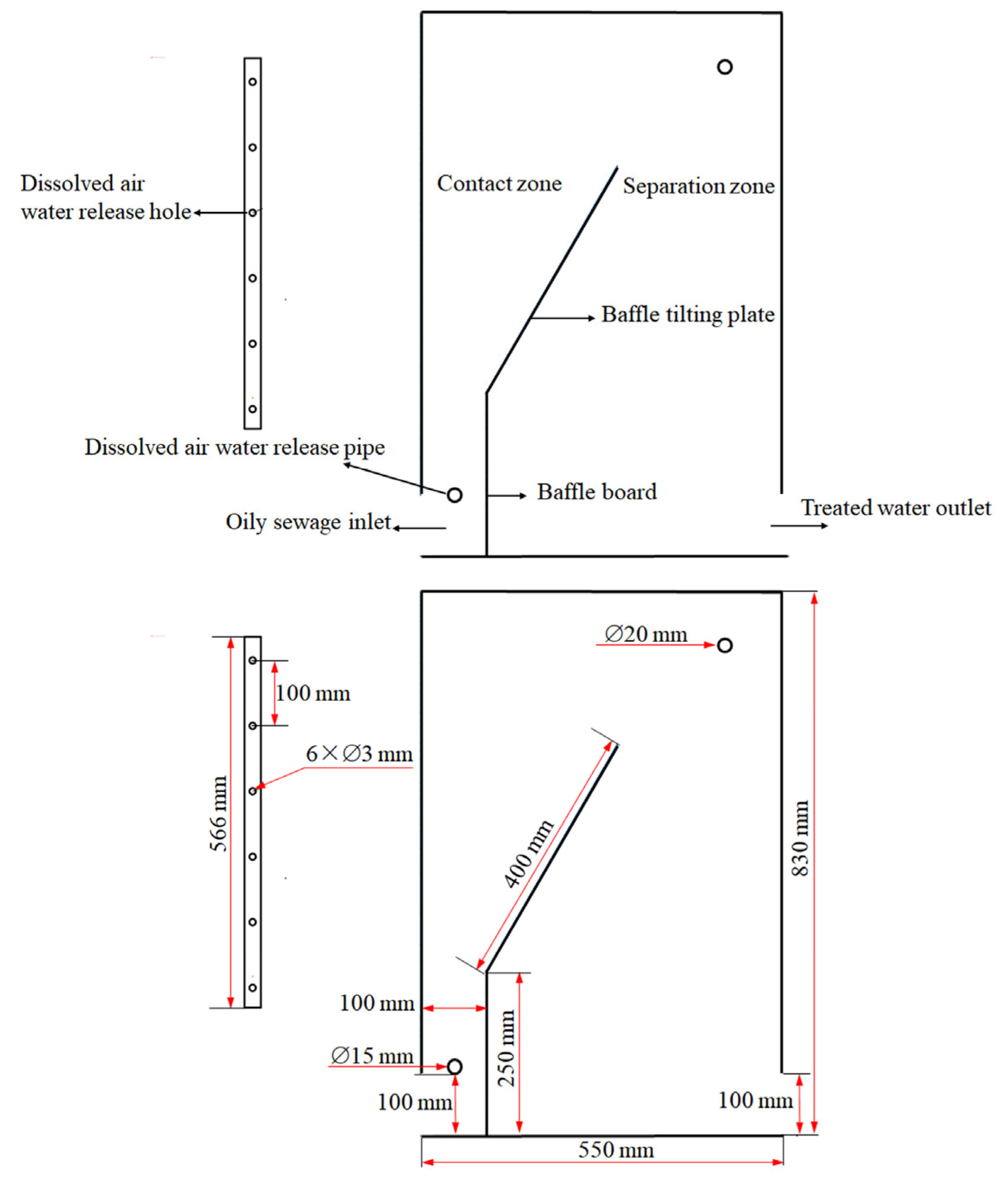

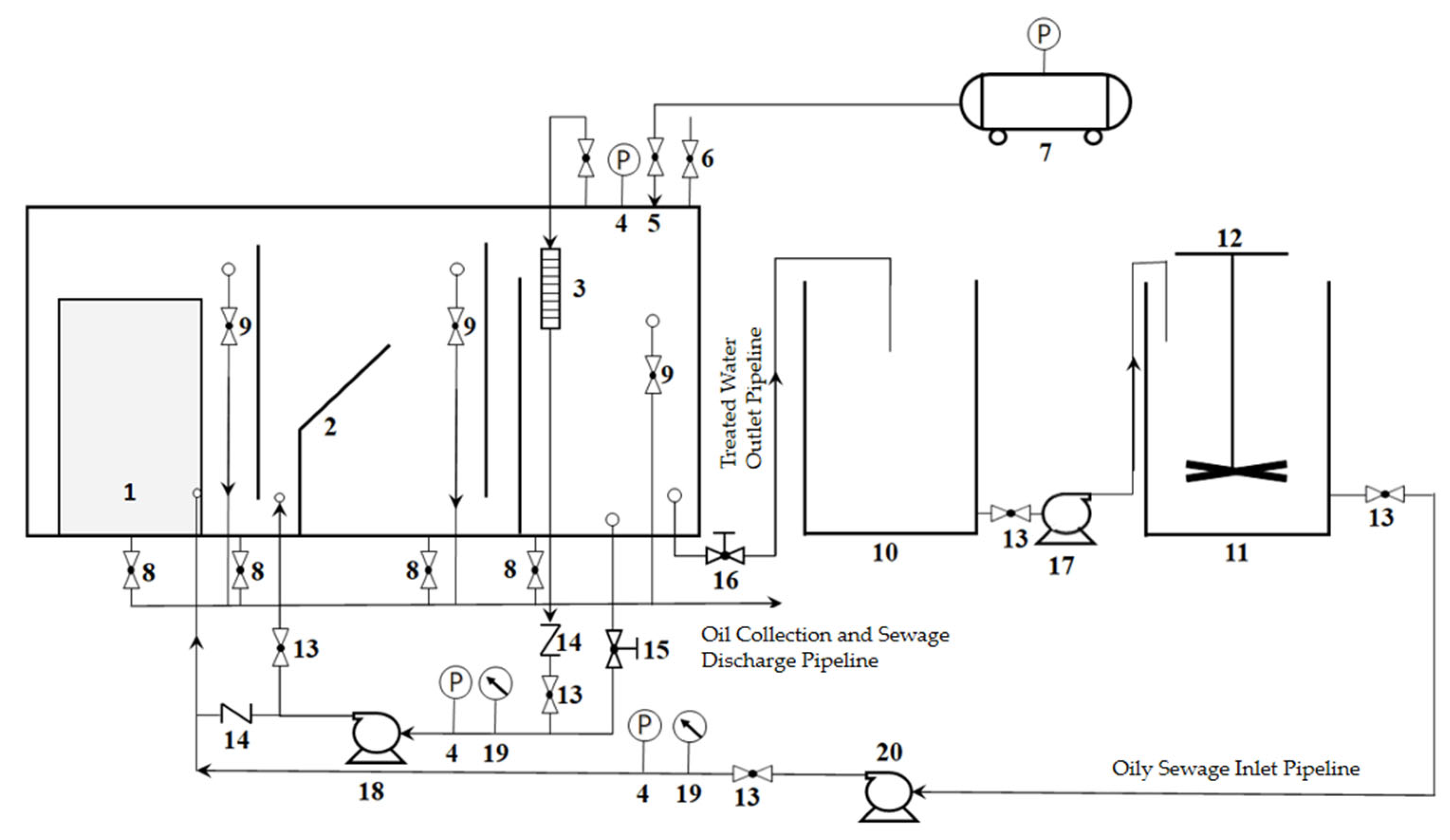

2.1. Geometric Model Building

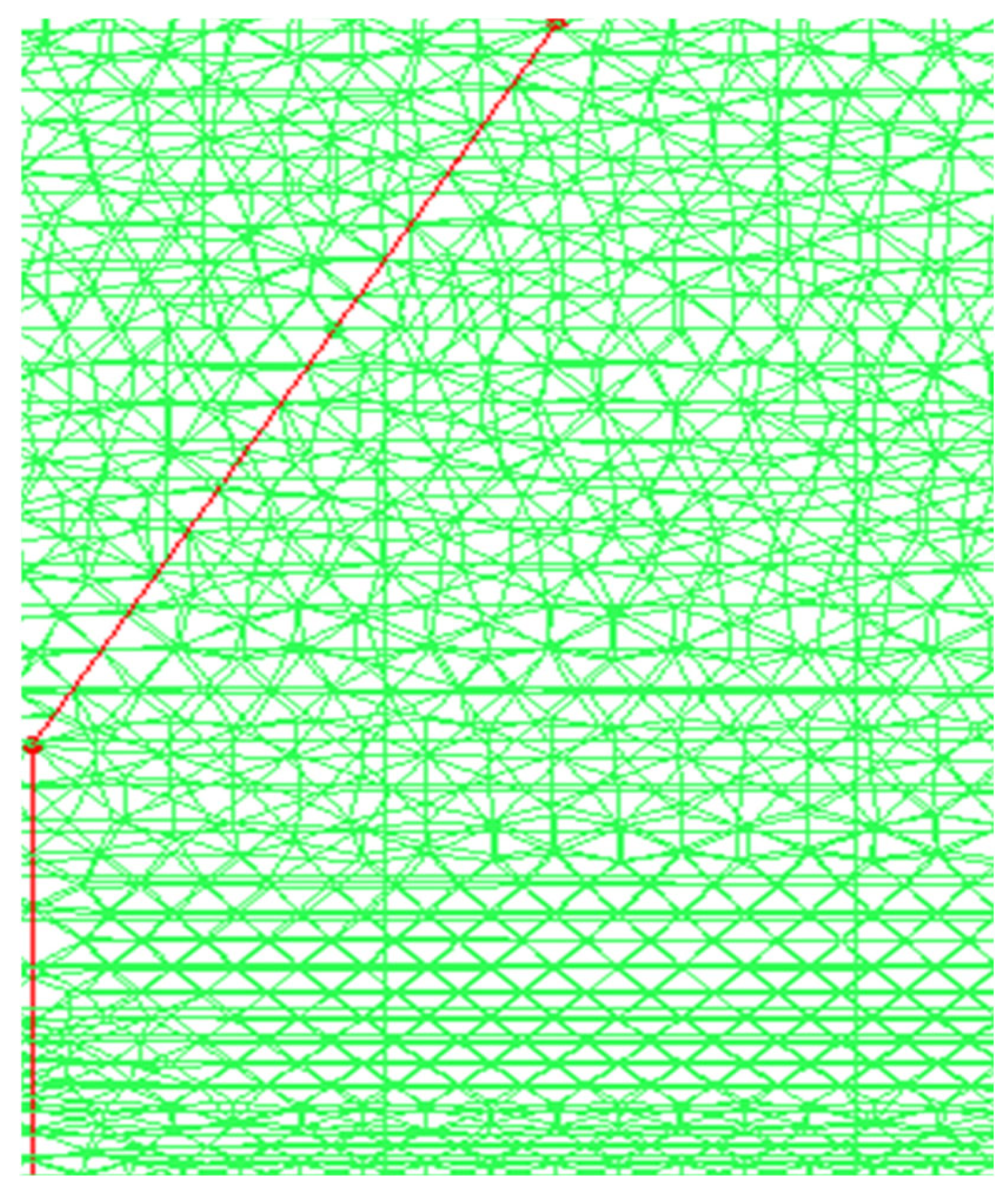

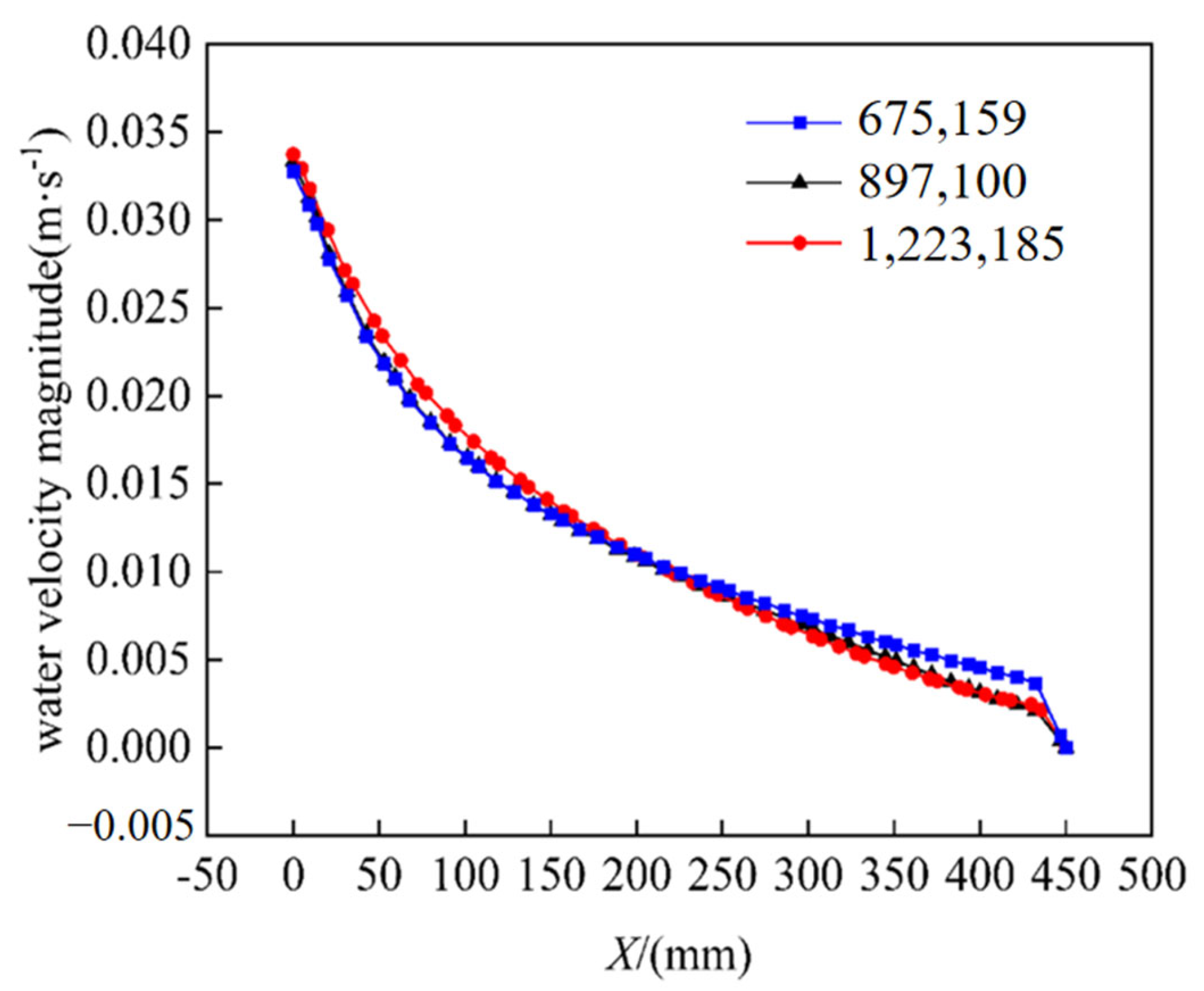

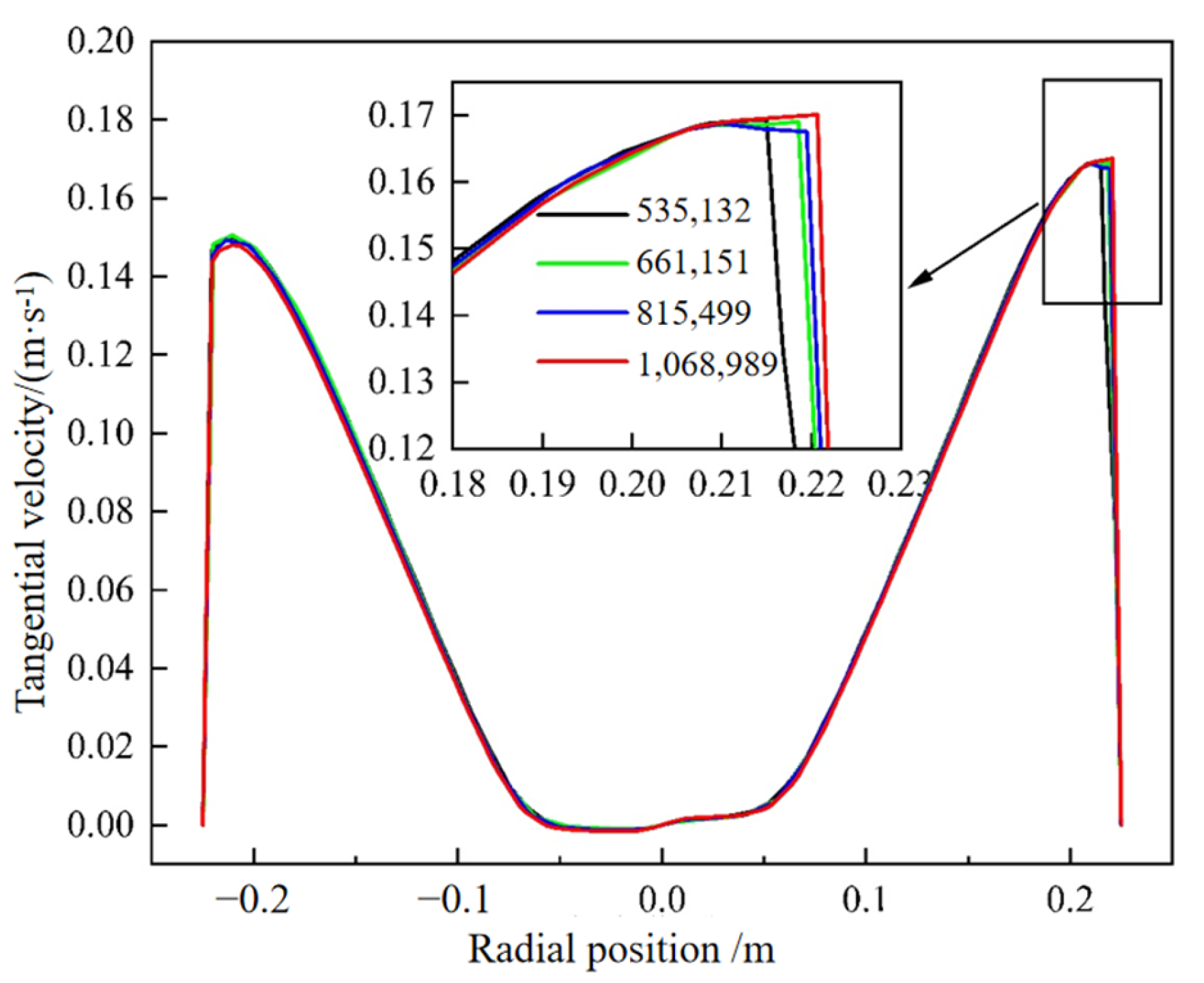

2.2. Meshing and Grid Independence Verification

3. Numeric Calculation Method

3.1. Multiphase Flow Model

3.2. Turbulence Model

3.3. Effect of Air Holdup on Flow Field

3.4. Grid Verification

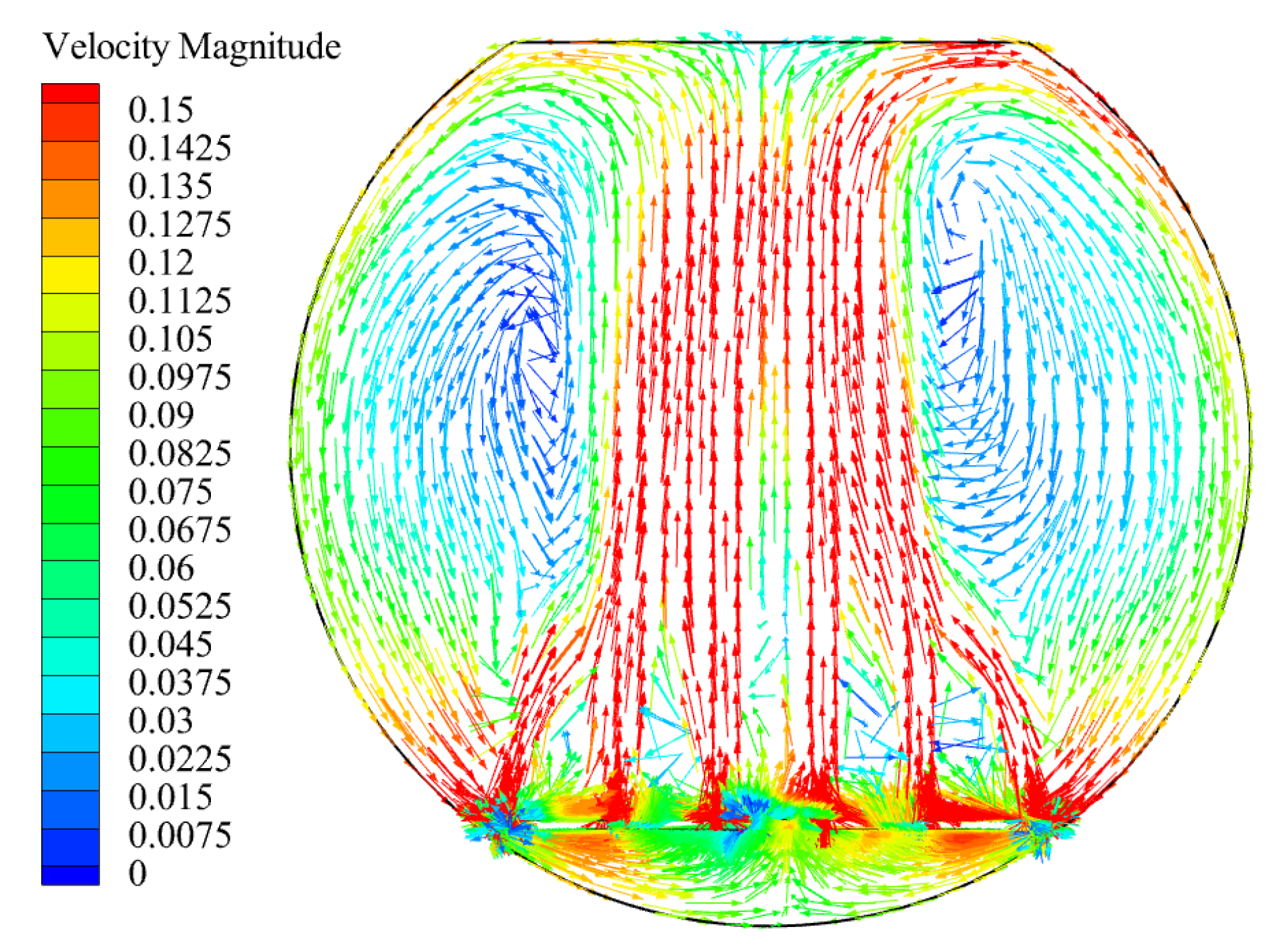

4. Results: Distribution Characteristics of Flow Field in Air Flotation Zone

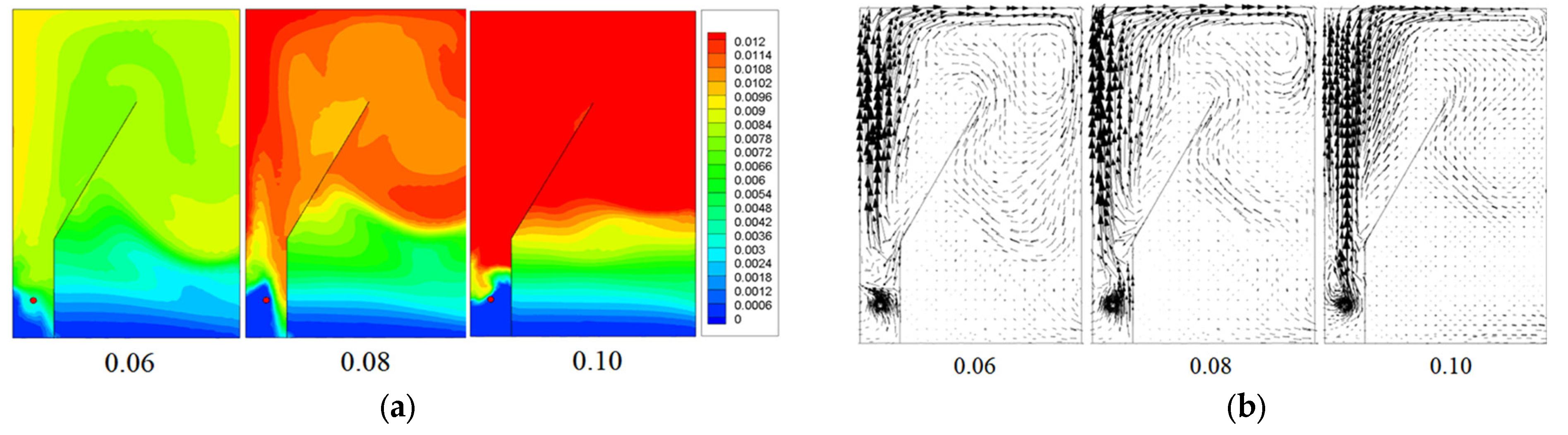

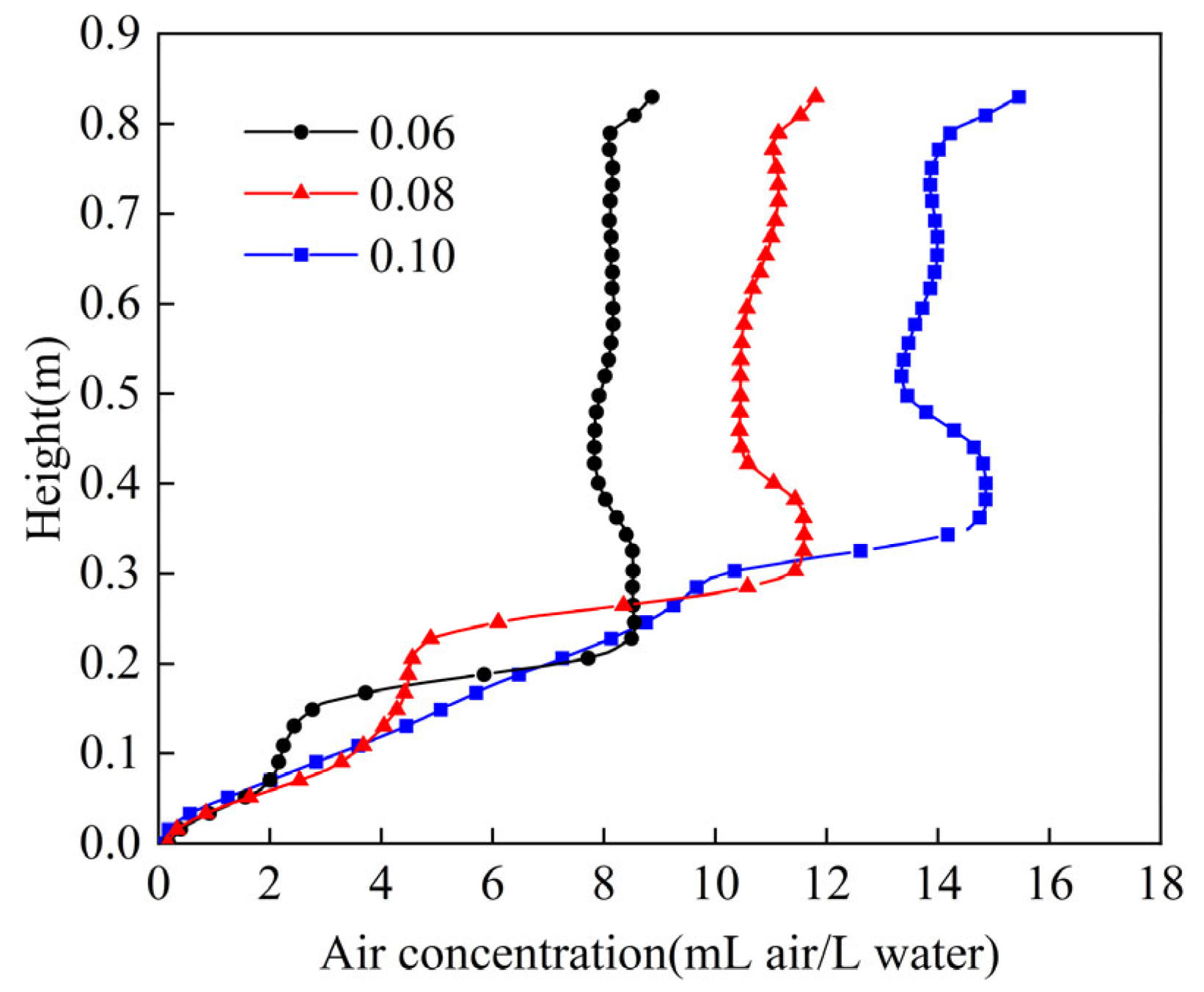

4.1. Effect of Air Holdup on Flow Field

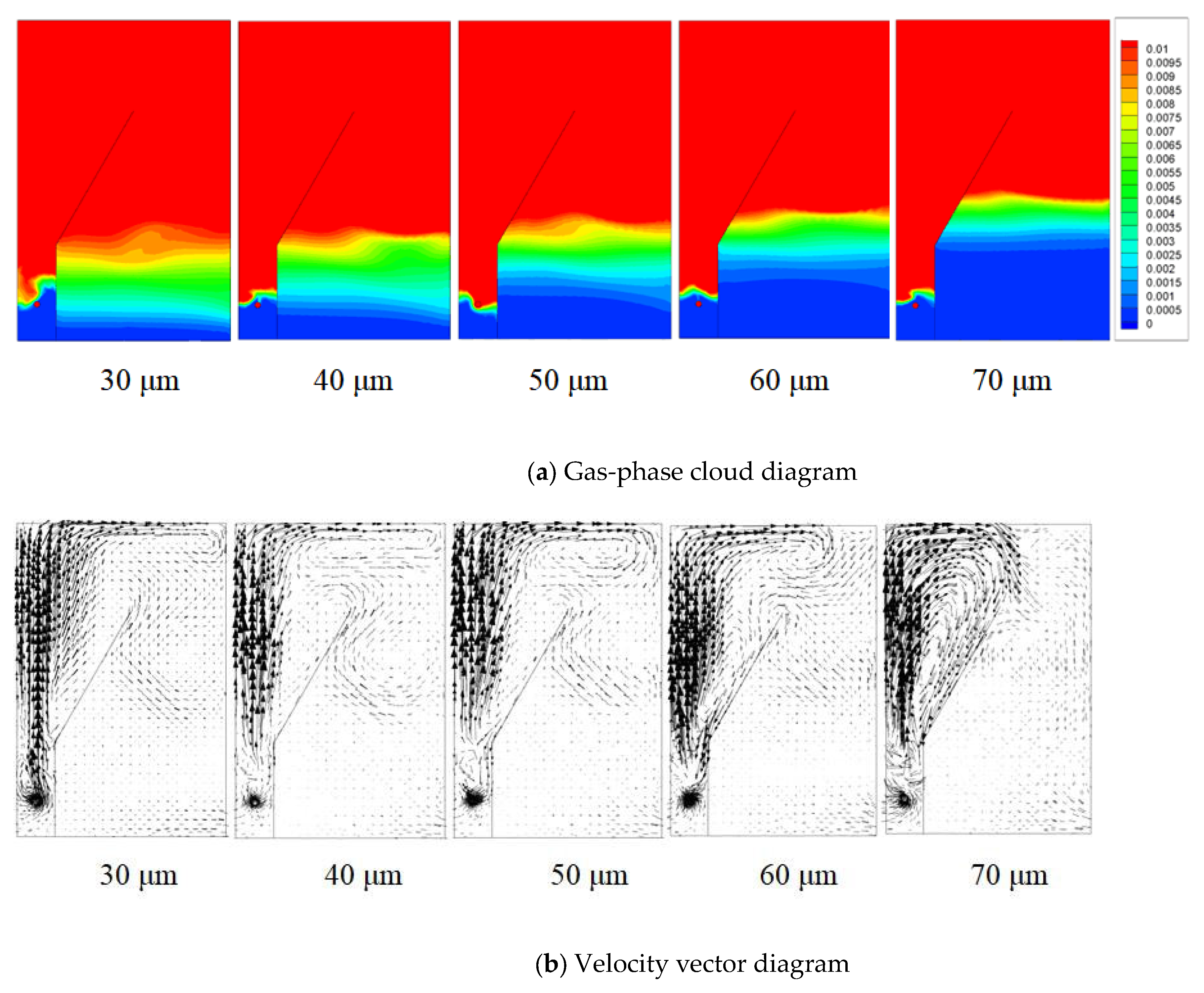

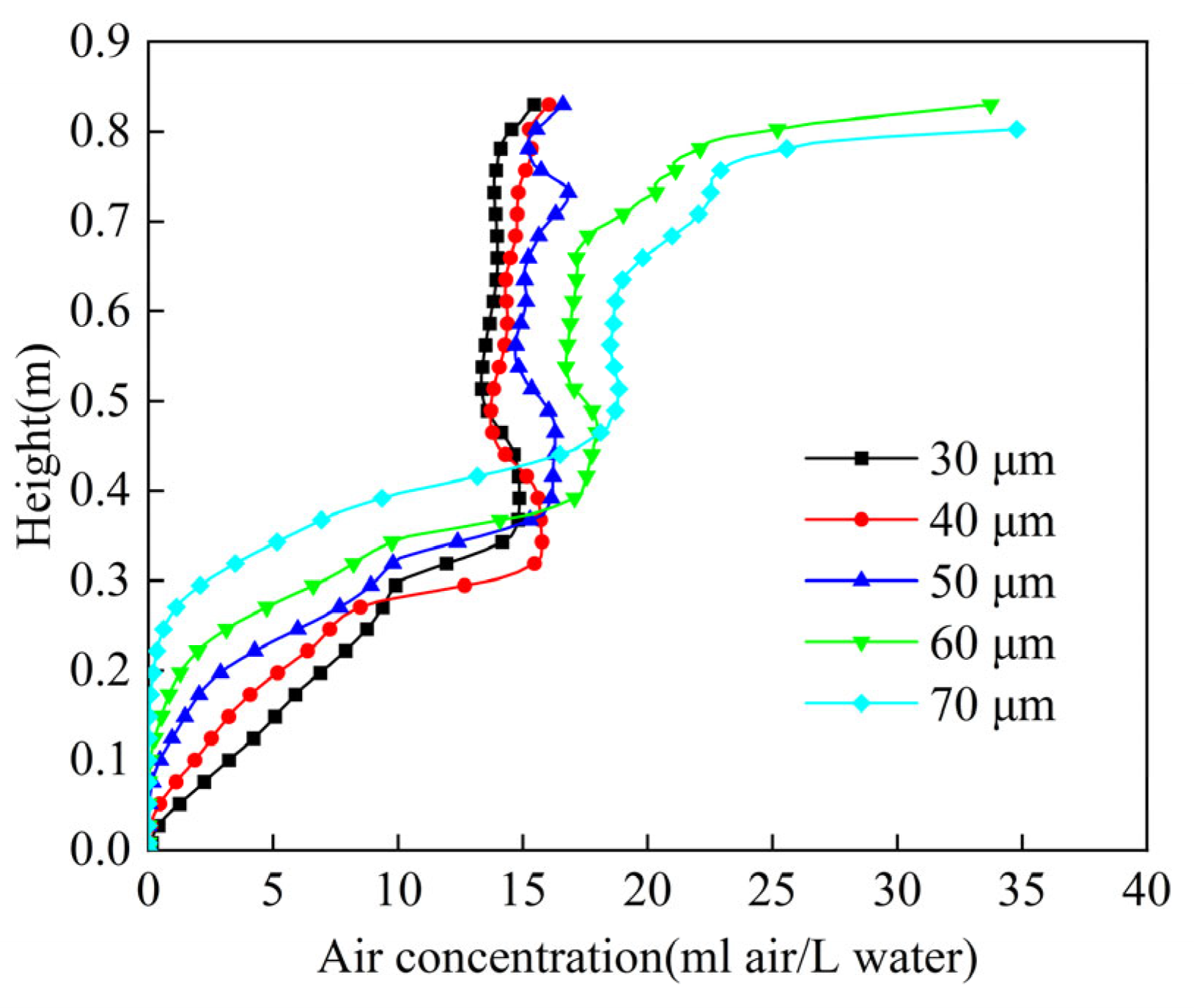

4.2. Effect of Bubble Size on the Flow Field

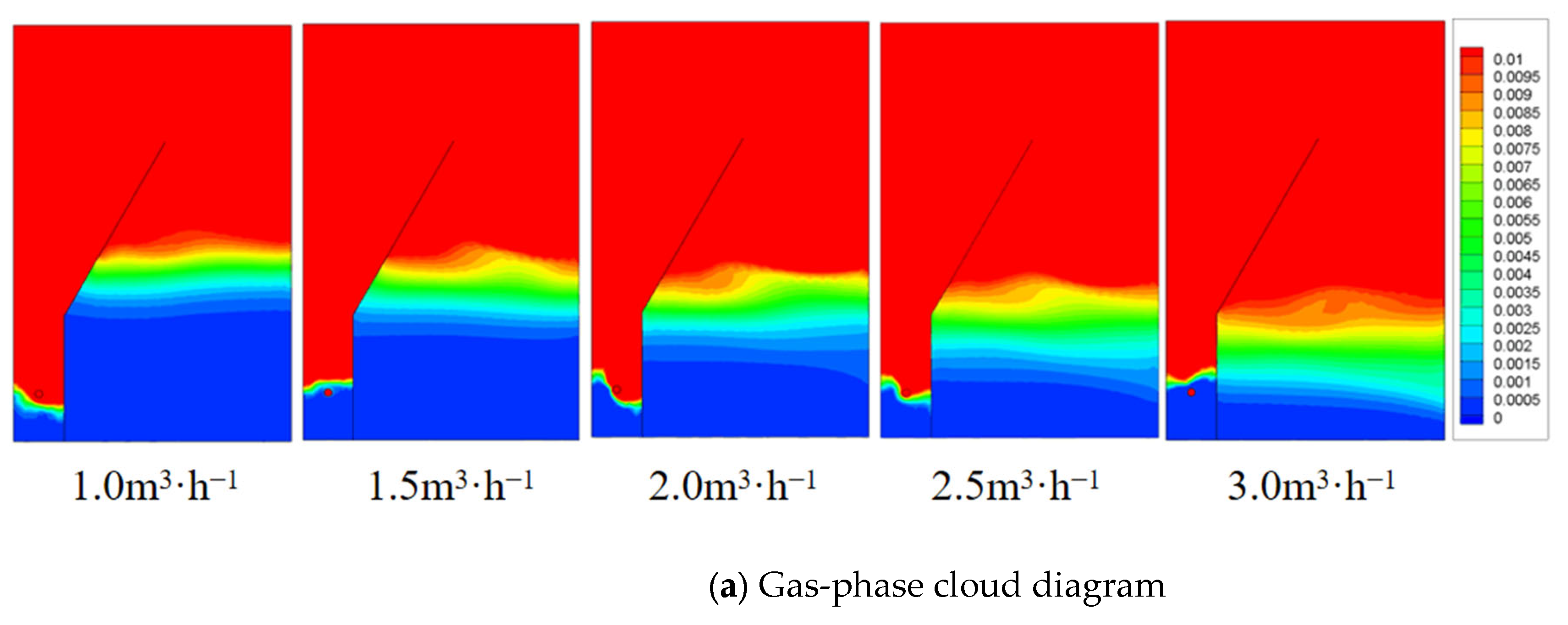

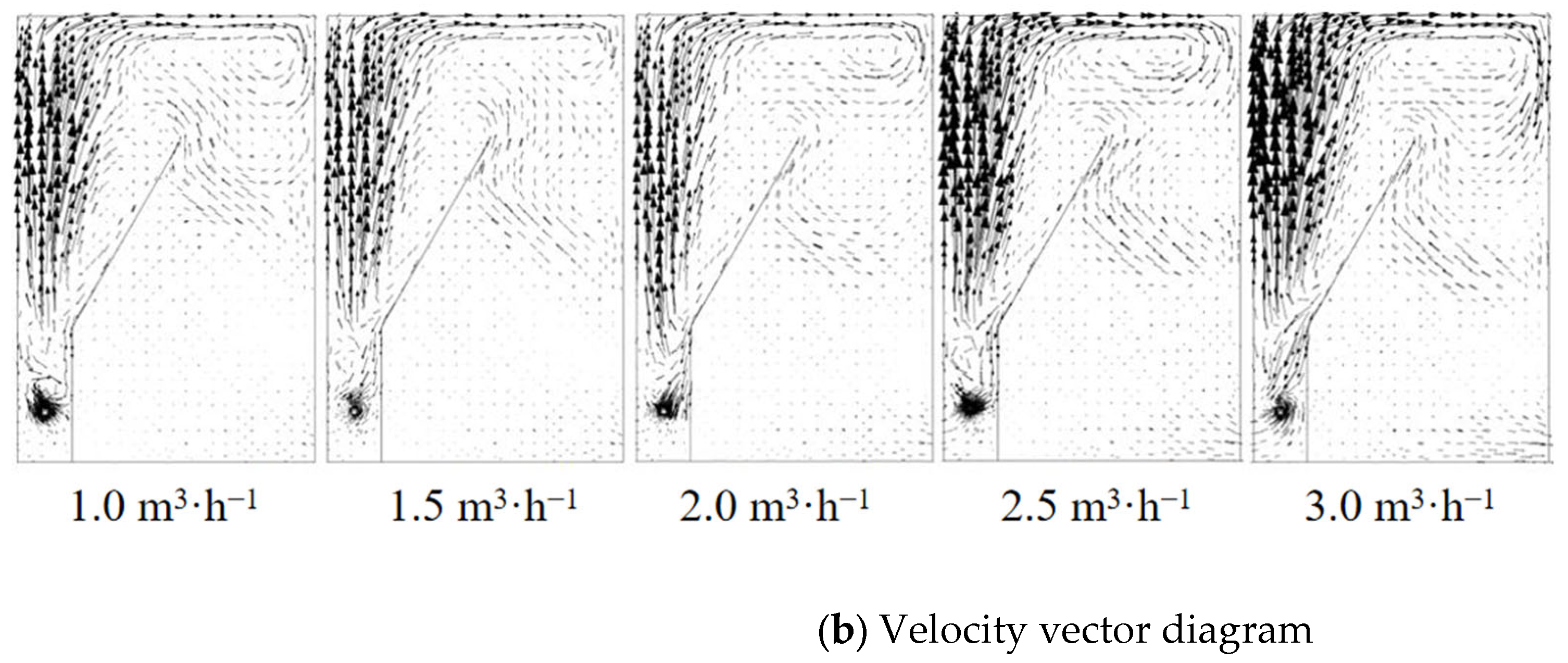

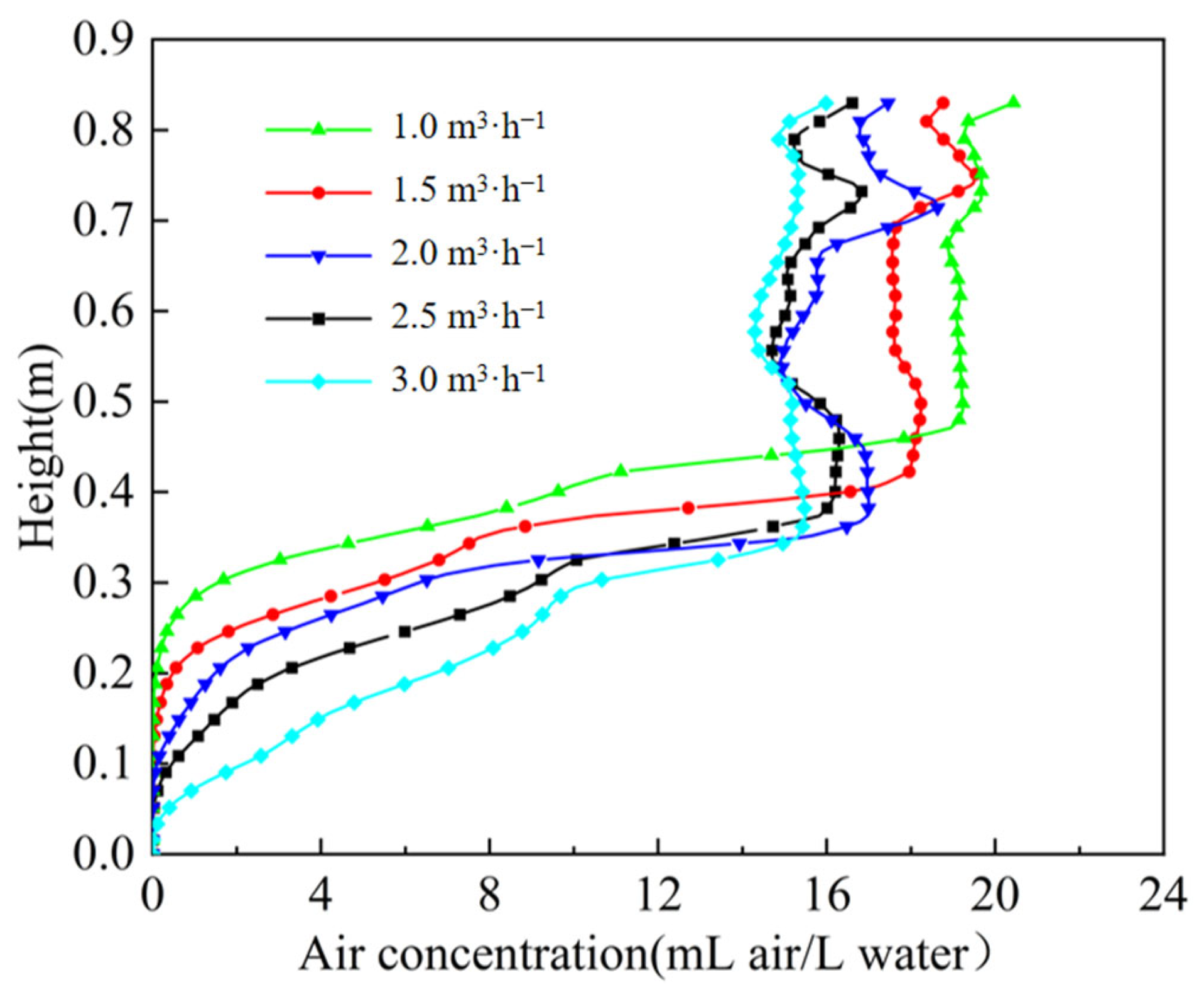

4.3. Effect of Treatment Capacity on the Flow Field

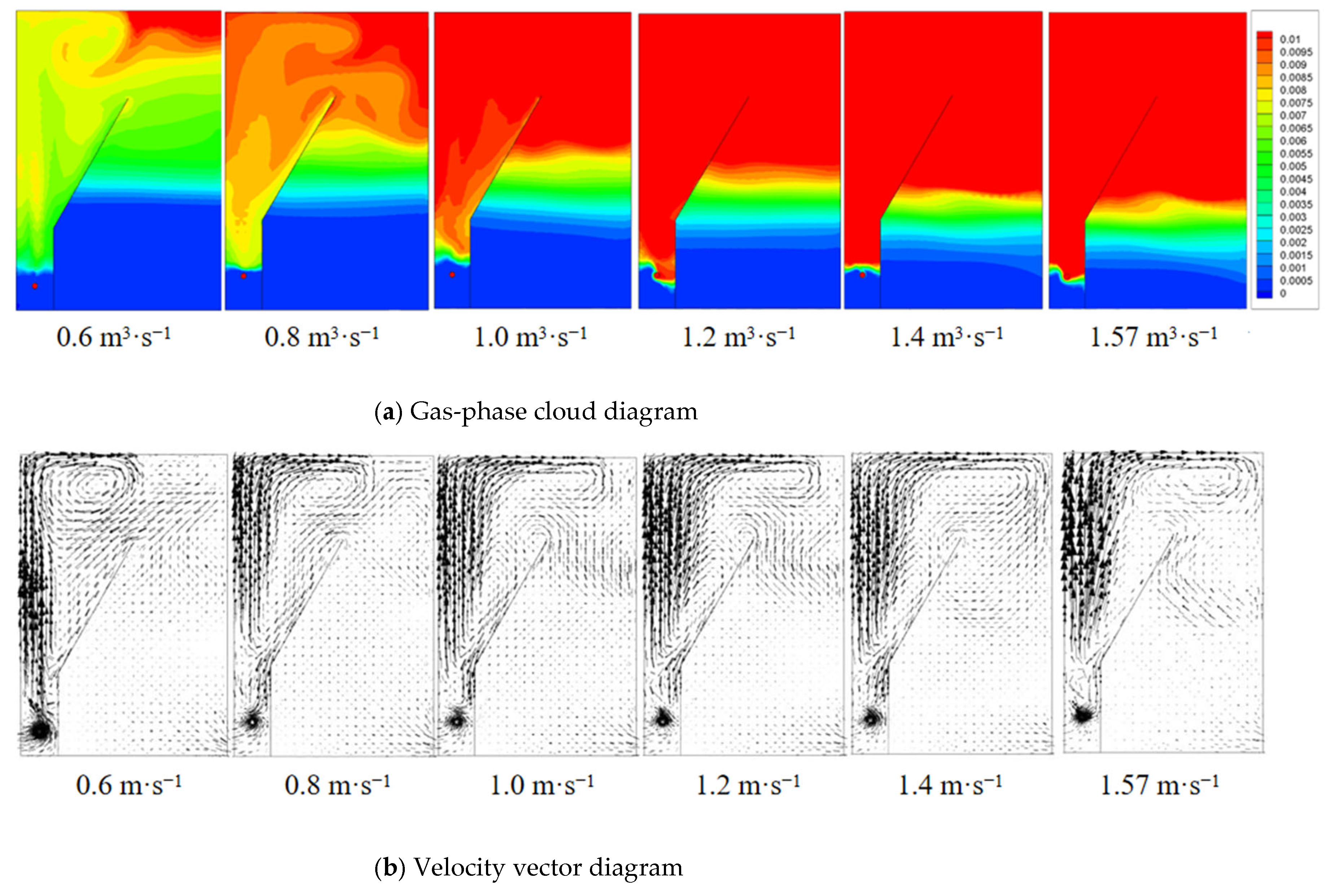

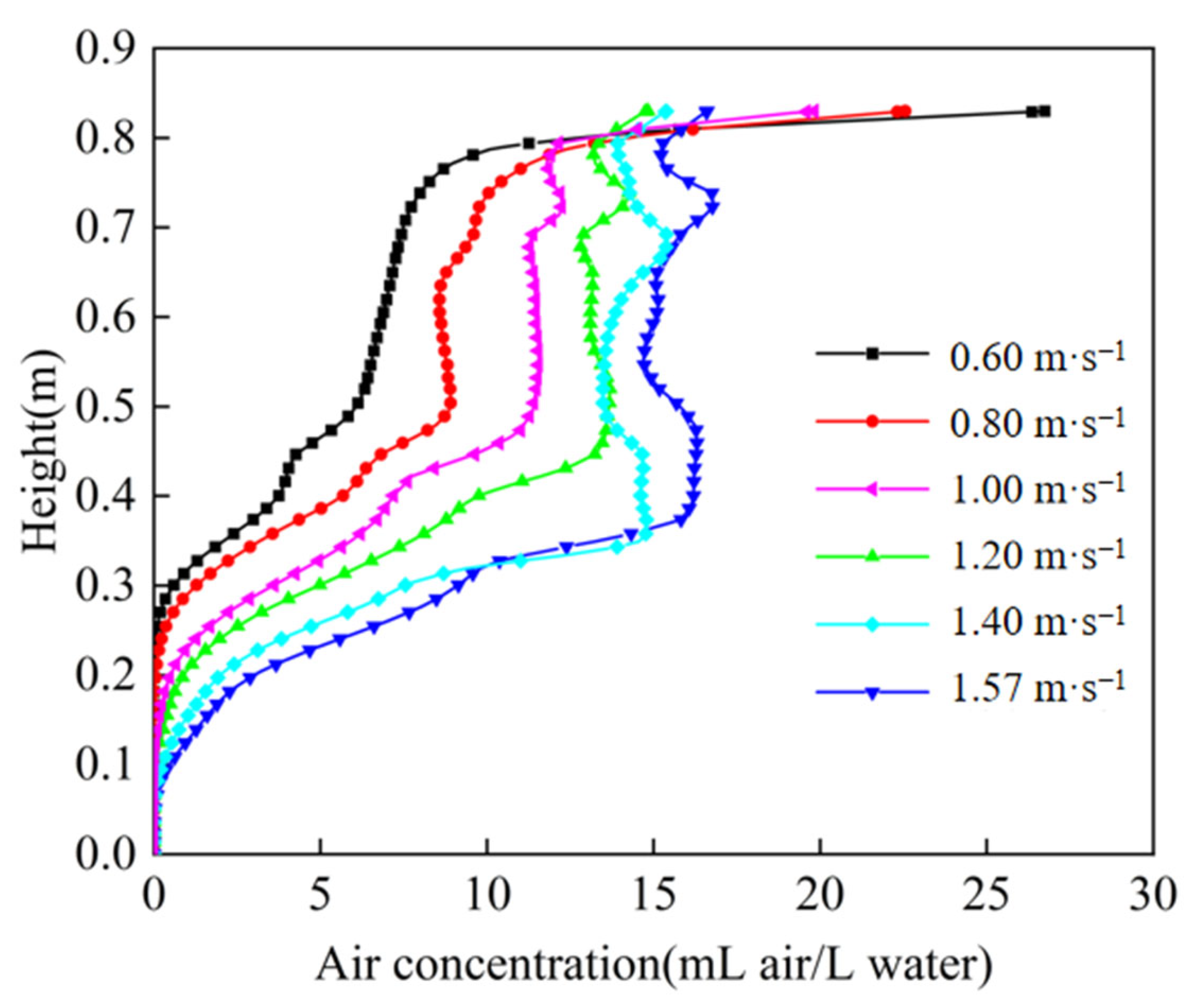

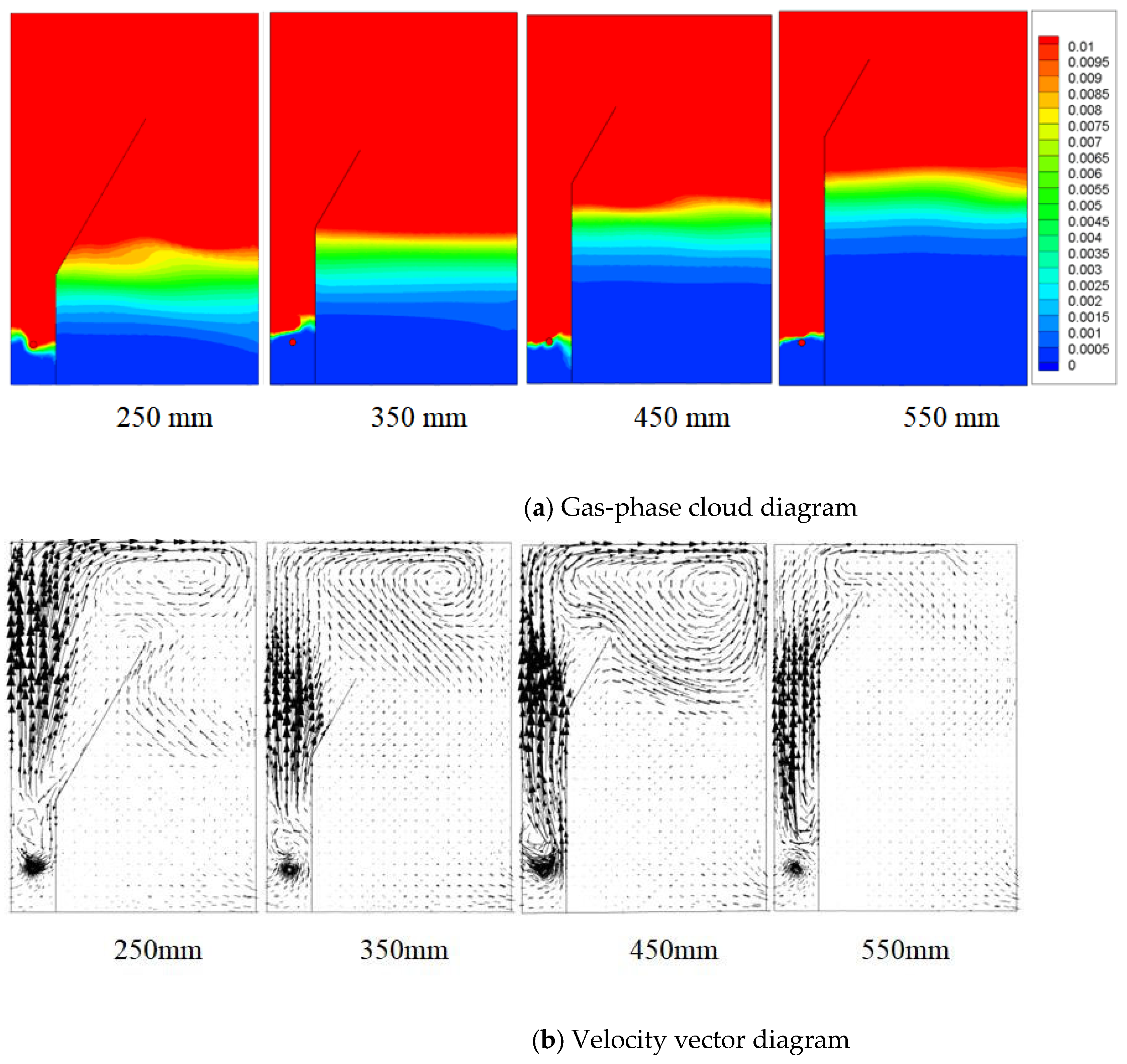

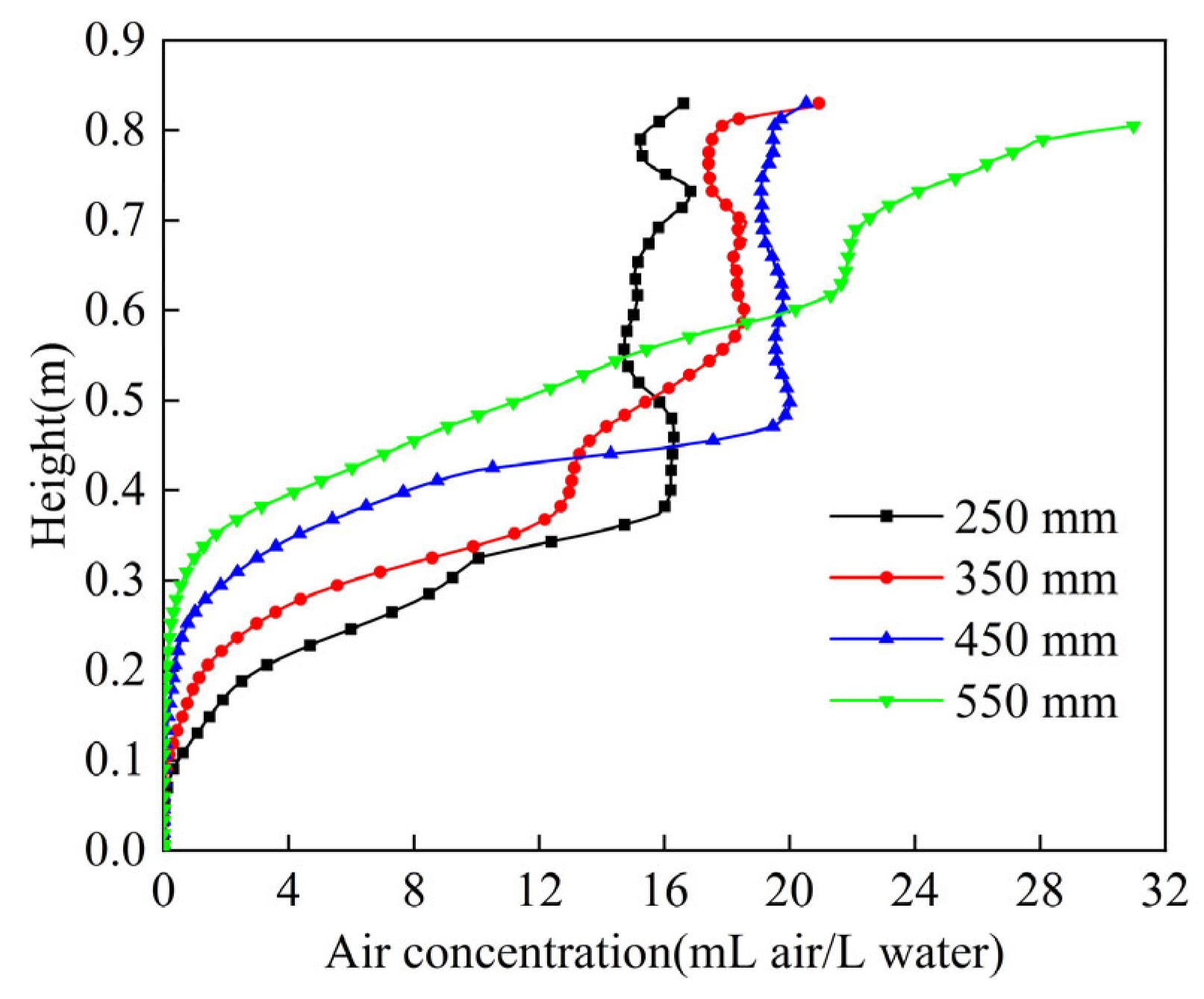

4.4. Effect of Dissolved Air Water Velocity on the Flow Field

4.5. Effect of Baffle Height on the Flow Field

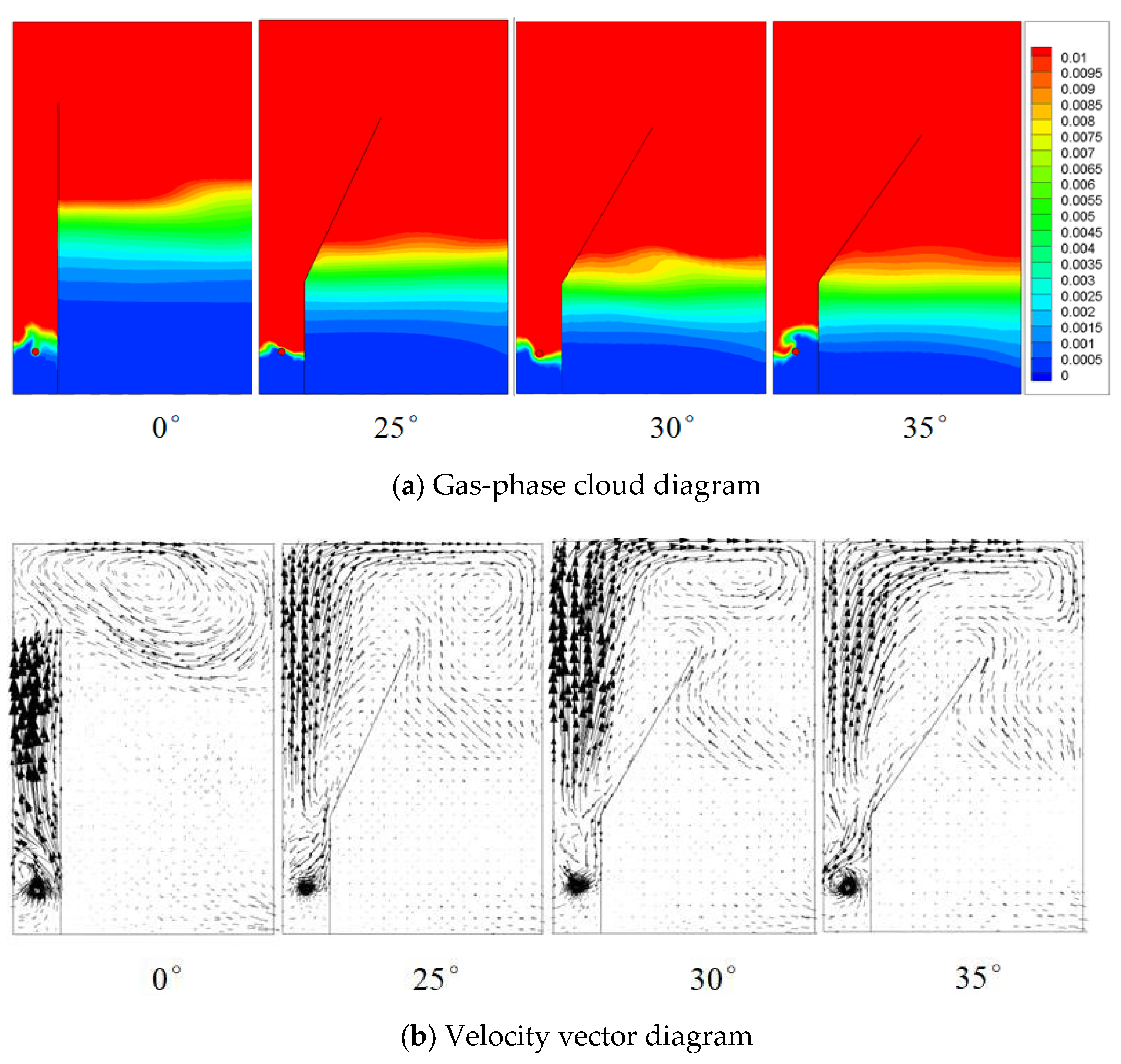

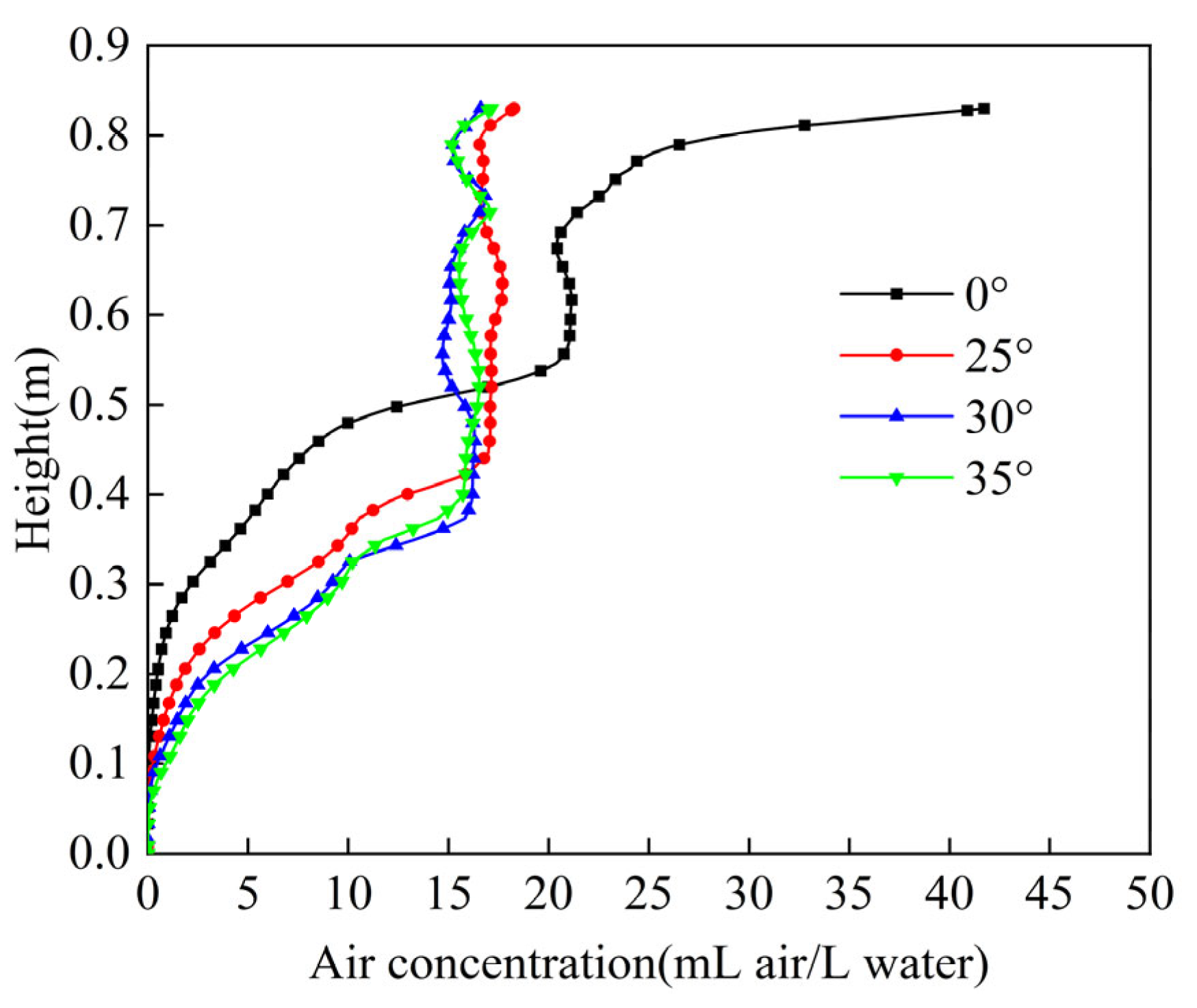

4.6. Effect of Baffle Inclination on the Flow Field

5. Oil–Gas–Water Three-Phase Flow Field Simulation

5.1. Numerical Calculation Method

5.1.1. Multiphase Flow Model

5.1.2. Turbulence Model

5.1.3. Effect of Air Holdup on Flow Field

5.2. Flow Field Distribution Characteristics

5.3. Influence of Inlet Parameters on Oil Removal Efficiency

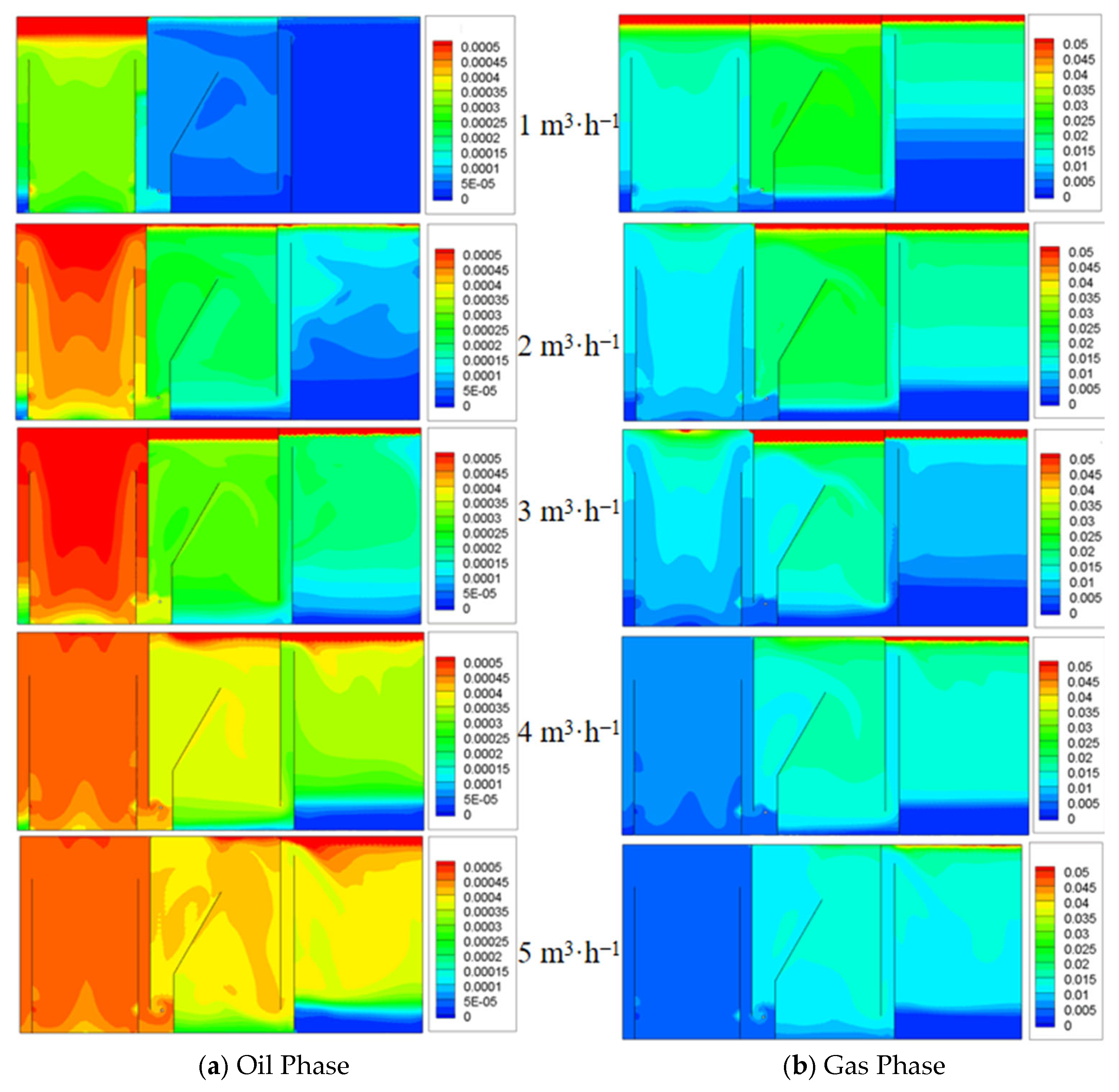

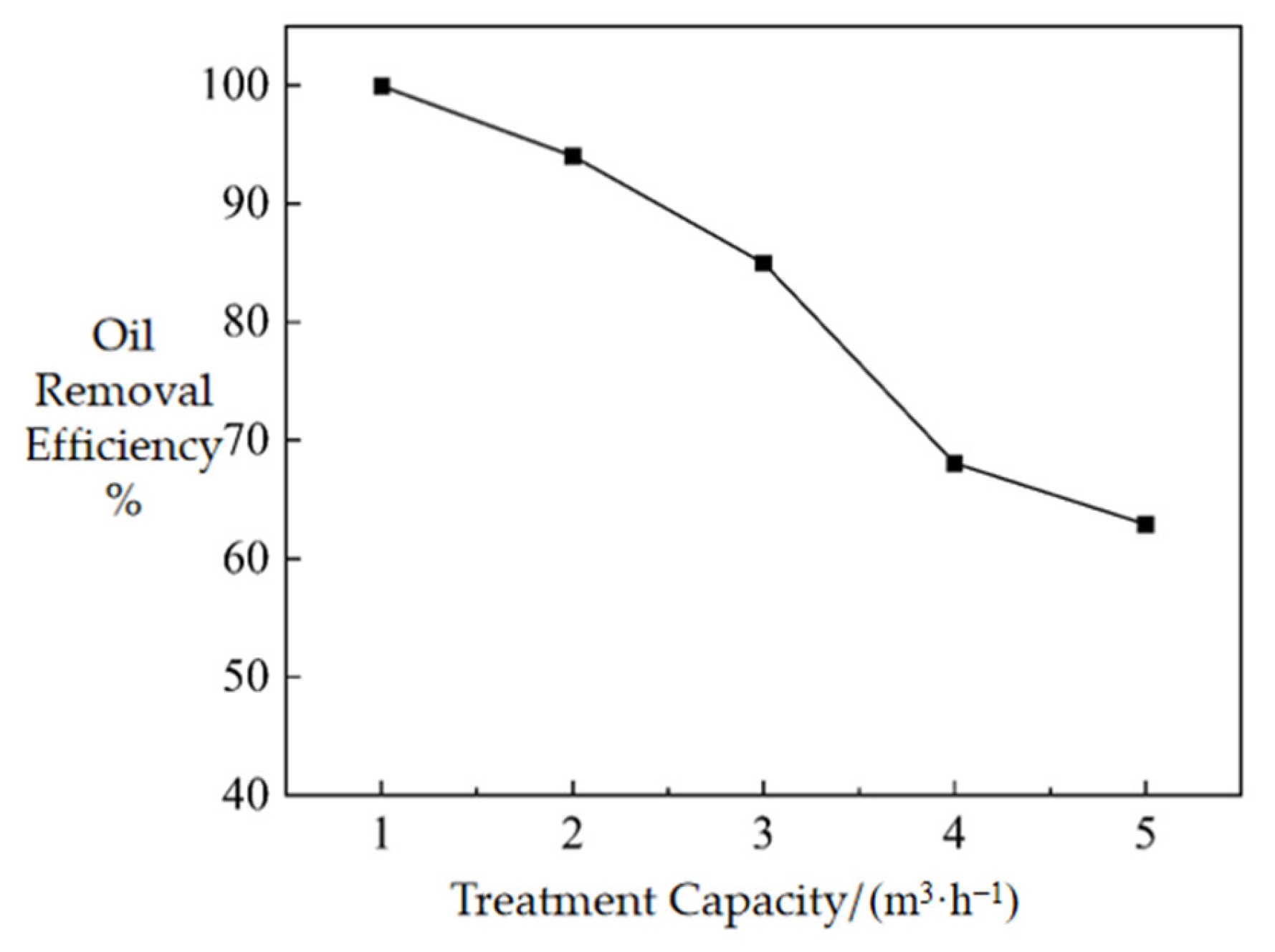

5.3.1. Treatment Capacity

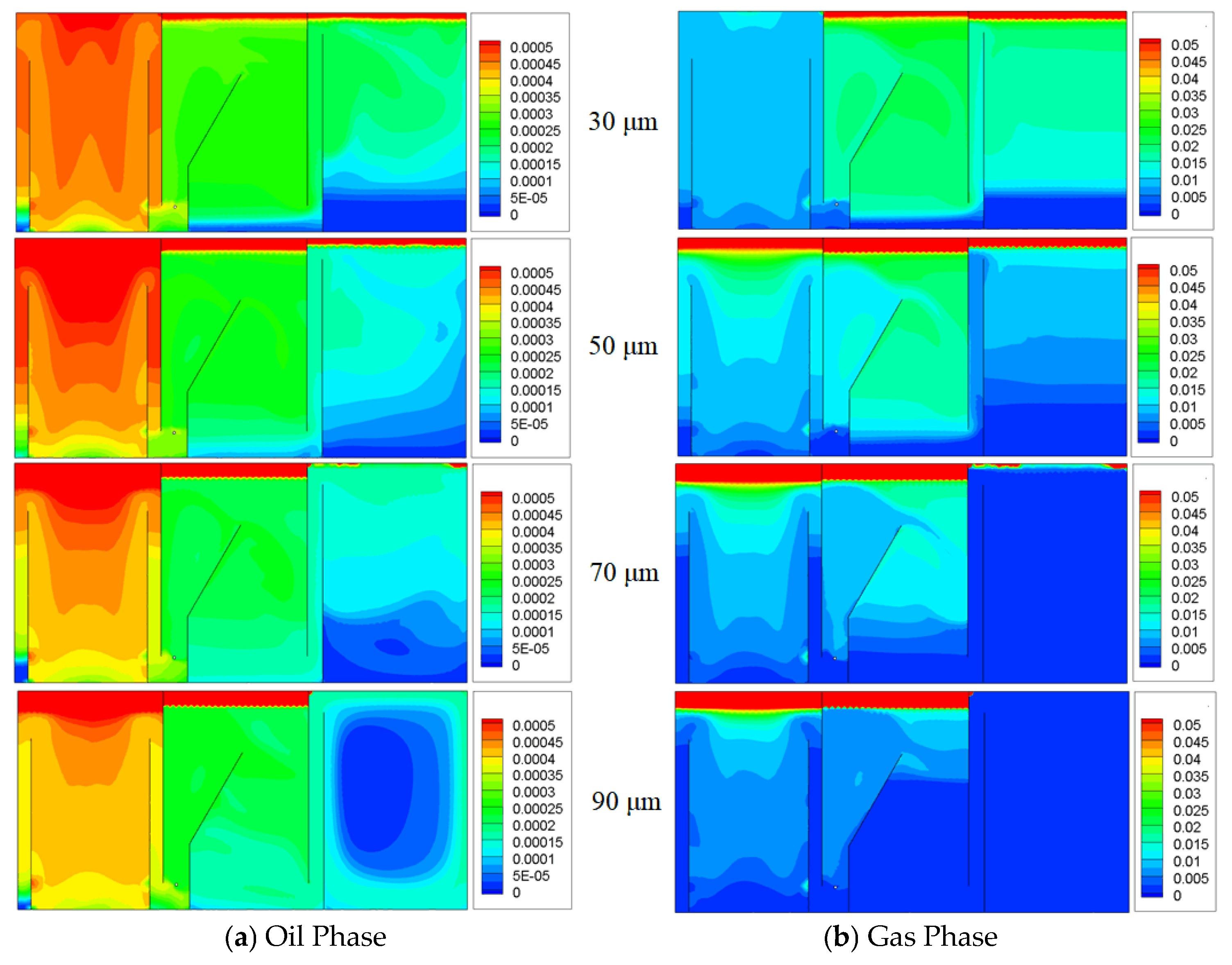

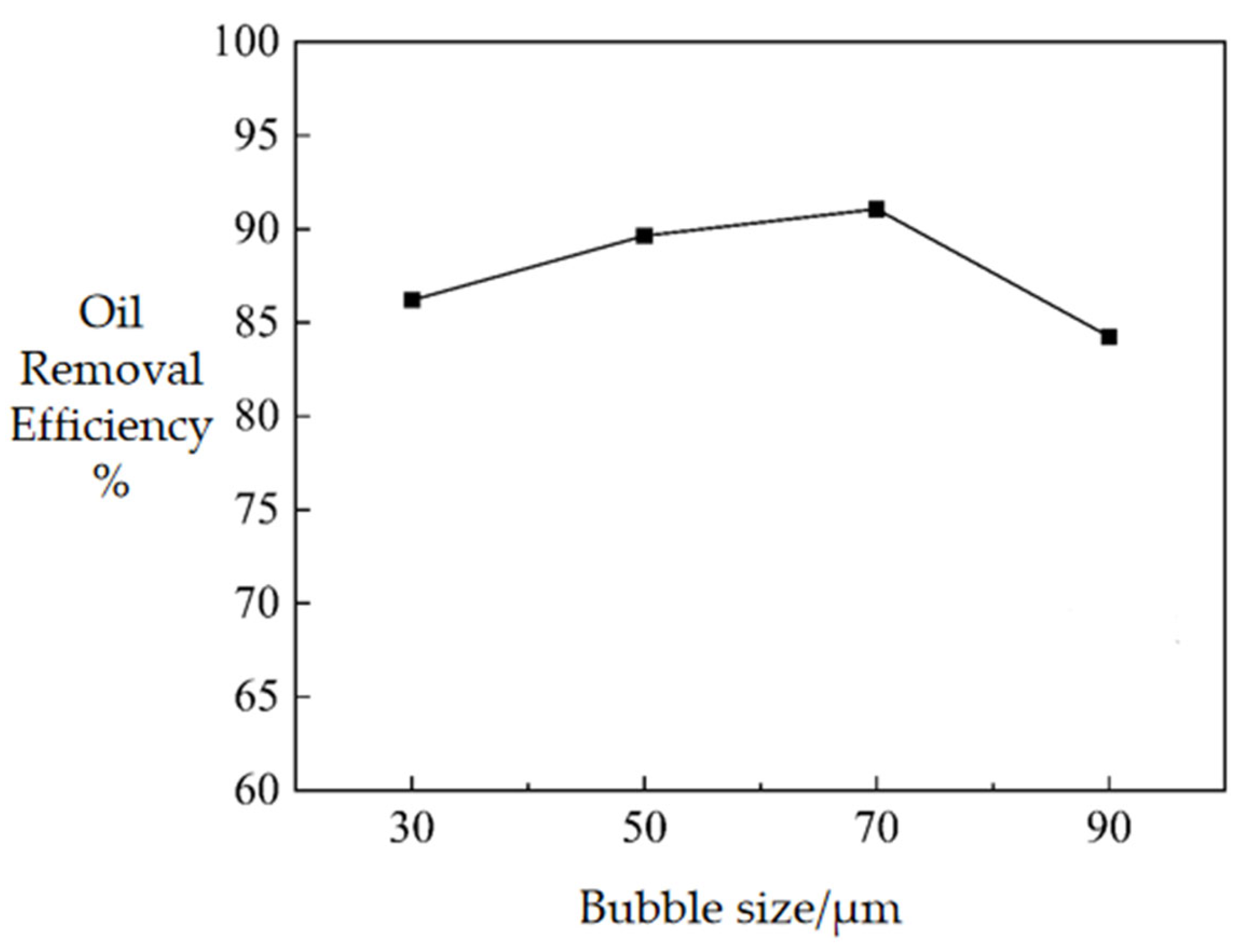

5.3.2. Bubble Size

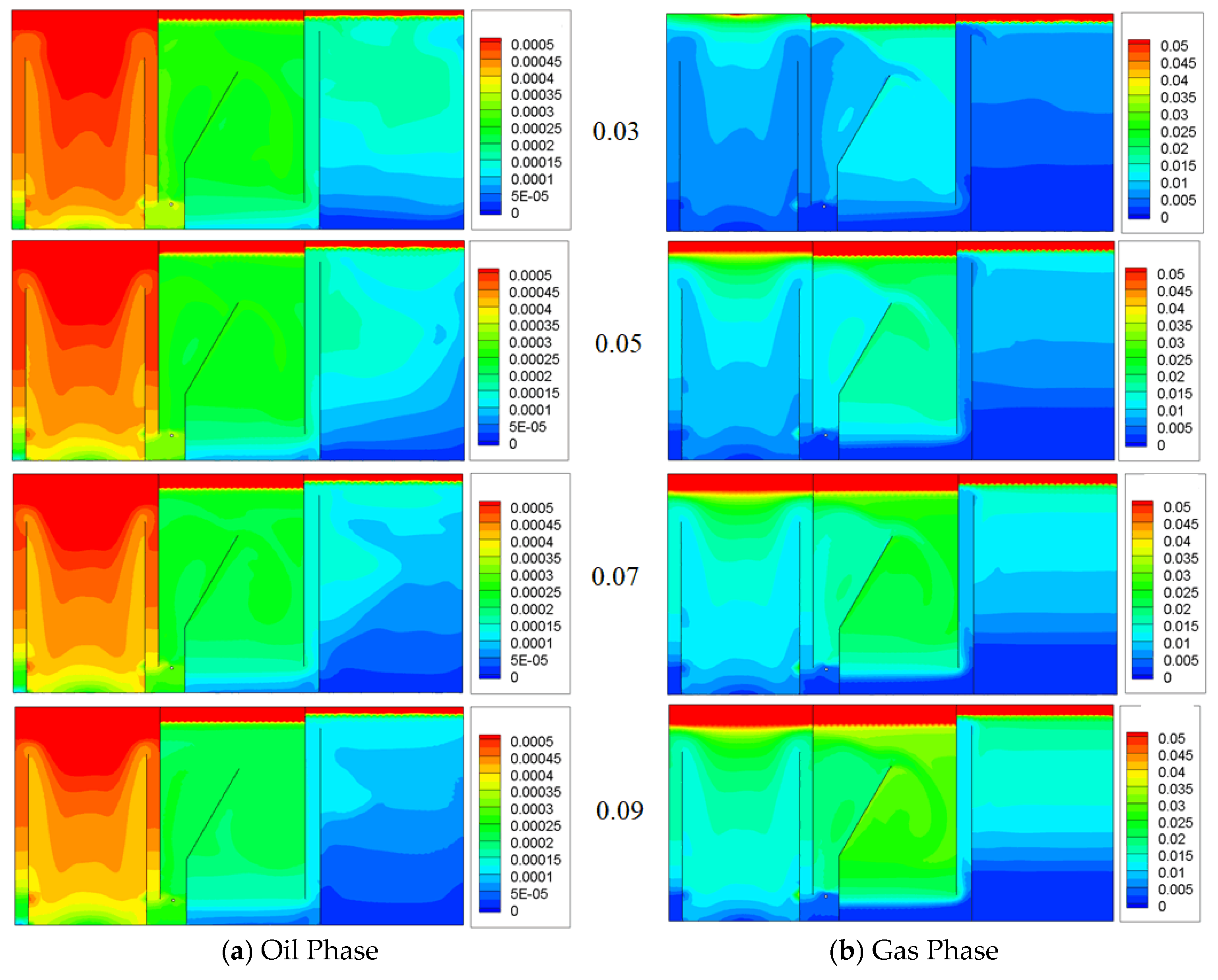

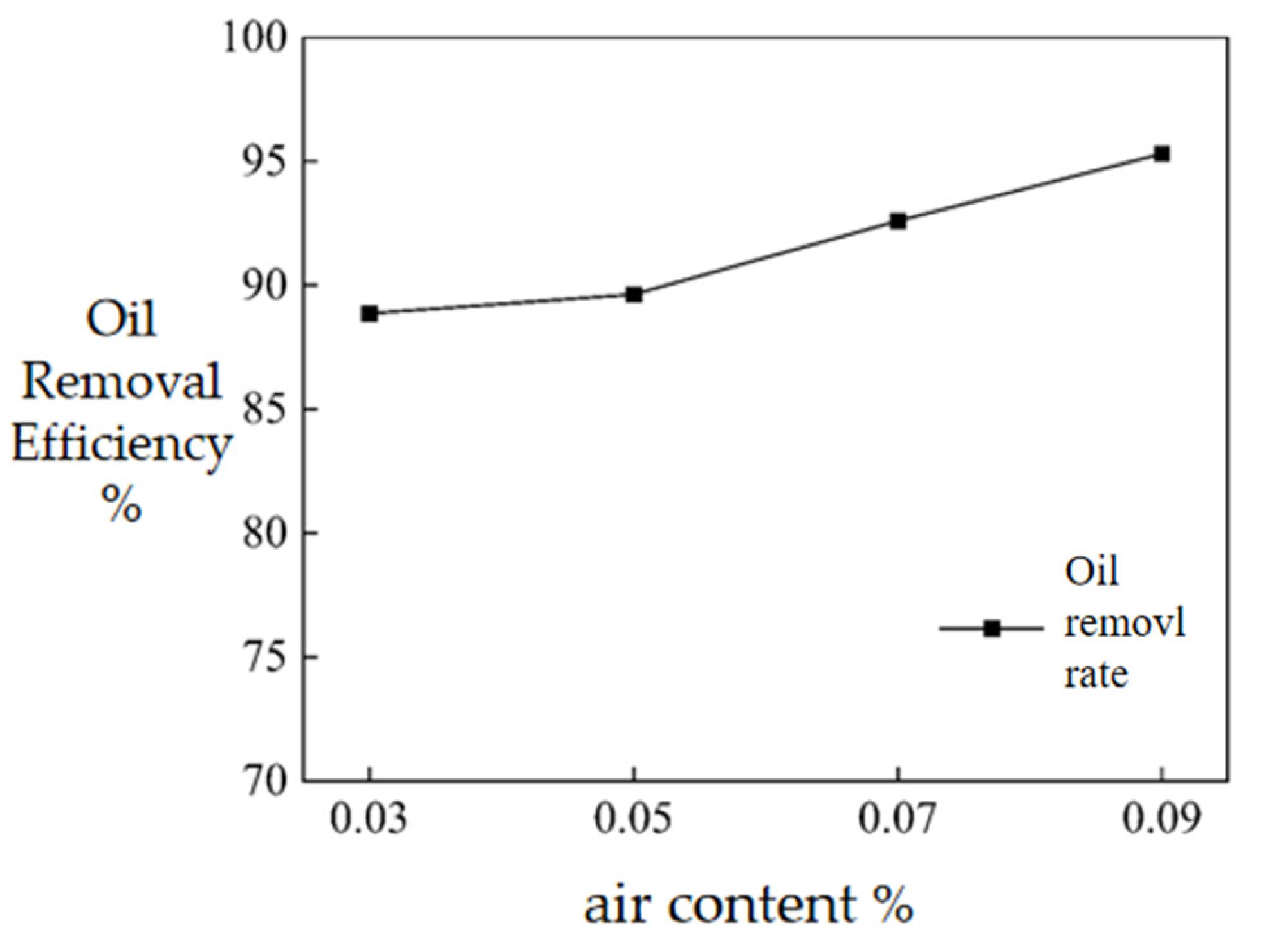

5.3.3. Inlet Gas Fraction

6. Experimental Verification

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- Oil removal efficiency decreases with increasing unit throughput. At a flow rate of 1 m3·h−1, the promotional effect on air flotation is minimal. Thus, the optimal flow rate is 2 m3·h−1, which is consistent with the optimal flow rate obtained for the flotation zone.

- (2)

- Oil removal efficiency first increases and then decreases with increasing bubble diameter, with the highest oil–water separation efficiency achieved at a bubble diameter of 70 μm.

- (3)

- Oil removal efficiency increases with increasing inlet gas holdup. Within the simulated range, the maximum oil–water separation efficiency occurs at a gas–oil ratio of 0.09, which is close to the optimal gas–oil ratio of 0.1 for the flotation zone.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Al-Kaabi, M.A.; Ashfaq, M.Y.; Da’na, D.A. Produced water characteristics, treatment and reuse: A review. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 28, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvoh, B.K.; Asdahl, S.; Rabe, K.; Ergon, R.; Halstensen, M. Online estimation of reject gas and liquid flow rates in compact flotation units for produced water treatment. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2012, 24, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Han, X.; Kong, H.; Liang, C. Research on the centrifugal flotation technique and its application in oily wastewater treatment. Environ. Eng. 2011, 29, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Su, K. Experimental Research on Bubble Distribution and Performance of Swage Oil Removal in Closed Flotation Device; China University of Petroleum: Qingdao, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sport, M.C. Design and operation of dissolved-gas flotation equipment for the treatment of oilfield produced brines. J. Pet. Technol. 1970, 22, 918–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundh, M.; Jönsson, L.; Dahlquist, J. Experimental studies of the fluid dynamics in the separation zone in dissolved air flotation. Water Res. 2000, 34, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakghomi, B.; Lawryshyn, Y.; Hofmann, R. Importance of flow stratification and bubble aggregation in the separation zone of a dissolved air flotation tank. Water Res. 2012, 46, 4468–4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakghomi, B.; Lawryshyn, Y.; Hofmann, R. A model of particle removal in a dissolved air flotation tank: Importance of stratified flow and bubble size. Water Res. 2015, 68, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edzwald, J.K. Dissolved air flotation and me. Water Res. 2010, 44, 2077–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edzwald, J.K. Developments of high rate dissolved air flotation for drinking water treatment. J. Water Supply Res. Technol. AQUA 2007, 56, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Liu, G.; Li, R.; Zhou, J. Study on influencing factors of gas flotation oily wastewater treatment process. J. Filtr. Sep. 2010, 20, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y. Experimental Research of Closed Circulation Flotation Degreasing Device; China University of Petroleum: Qingdao, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P. Research on Advection-Type Pressurized Dissolved Air Flotation Water Treatment; Zhengzhou University: Zhengzhou, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D. Experimental Study of Oily Wastewater Treatment with Multiphase Pump Dissolved Air Flotation; China University of Petroleum: Qingdao, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Research on Oil-water Separation Technology with the Advection-type Pressurized Dissolved Air Flotation; China University of Petroleum: Qingdao, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, A.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, X. Influencing factors and mechanism of separation of emulsified oil by dissolved air floatation. Technol. Water Treat. 2017, 43, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundh, M.; Jönsson, L.; Dahlquist, J. The influence of contact zone configuration on the flow structure in a dissolved air flotation pilot plant. Water Res. 2002, 36, 1585–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; del Pozo, D.F.; Torfs, E.; Rehman, U.; Yu, D.; Nopens, I. Numerical simulation on the effects of bubble size and internal structure on flow behavior in a DAF tank: A comparative study of CFD and CFD-PBM approach. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2021, 7, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaahmadi, A. Dissolved Air Flotation-Numerical Investigation of the Contact Zone on Geometry, Multiphase Flow and Needle Valves; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Haarhoff, J.; Edzwald, J.K. Dissolved air flotation modelling: Insights and shortcomings. J. Water Supply Res. Technol. AQUA 2004, 53, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J. Influence of bubble size on the fluid dynamic behavior of a DAF tank: A 3D numerical investigation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 495, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Kim, H.; Kuk, J.W.; Chung, J.D.; Park, S.; Kwon, E.E. Micro-bubble flow simulation of dissolved air flotation process for water treatment using computational fluid dynamics technique. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 256, 112050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jin, X.; Yang, S.; Wang, G.; Xu, L.; Jin, P.; Shi, X.; Shi, Y. Interactions between flocs and bubbles in the separation zone of dissolved air flotation system. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 761, 143222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondelind, M.; Sasic, S.; Pettersson, T.J.R.; Karapantsios, T.D.; Kostoglou, M.; Bergdahl, L. Setting up a numerical model of a DAF tank: Turbulence, geometry, and bubble size. J. Environ. Eng. 2010, 136, 1424–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondelind, M.; Sasic, S.; Kostoglou, M.; Bergdahl, L.; Pettersson, T.J. Single-and two-phase numerical models of Dissolved Air Flotation: Comparison of 2D and 3D simulations. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2010, 365, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostoglou, M.; Karapantsios, T.D.; Matis, K.A. CFD model for the design of large scale flotation tanks for water and wastewater treatment. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 6590–6599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Long, X. Analysis of the influencing factors on oil removal efficiency in large-scale flotation tanks: Experimental observation and numerical simulation. Energies 2020, 13, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Yang, W.; Geng, S.; Gao, F.; He, T.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Q. Modeling of Microbubble Flow and Coalescence Behavior in the Contact Zone of a Dissolved Air Flotation Tank Using a Computational Fluid Dynamics–Population Balance Model. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 16989–17000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.P.; Batista, J.N.M.; Béttega, R. Application of population balance equations and interaction models in CFD simulation of the bubble distribution in dissolved air flotation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 577, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, W.; Yan, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. Regulation of bubble size in flotation: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104070. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R. Numerical Simulation of Oil-Water Separation Process in Combined Three-Phase Separator; China University of Petroleum: Qingdao, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Treatment Capacity | Oily Wastewater Inlet (kg·s−1) | Oil Collection 1 (kg·s−1) | Oil Collection 2 (kg·s−1) | Treated Water Outlet (kg·s−1) | Oil Removal Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 m3·h−1 | 1.21 × 10−4 | 1.07 × 10−5 | 1.44 × 10−5 | 7.34 × 10−8 | 99.94% |

| 2 m3·h−1 | 2.42 × 10−4 | 1.95 × 10−5 | 8.80 × 10−5 | 1.45 × 10−5 | 94.03% |

| 3 m3·h−1 | 3.63 × 10−4 | 2.82 × 10−5 | 1.62 × 10−5 | 5.45 × 10−5 | 84.98% |

| 4 m3·h−1 | 4.84 × 10−4 | 3.05 × 10−5 | 2.53 × 10−5 | 1.55 × 10−4 | 68.06% |

| 5 m3·h−1 | 6.05 × 10−4 | 3.62 × 10−5 | 3.17 × 10−5 | 2.24 × 10−4 | 62.92% |

| Bubble size | Oily Wastewater Inlet (kg·s−1) | Oil Collection 1 (kg·s−1) | Oil Collection 2 (kg·s−1) | Treated Water Outlet (kg·s−1) | Oil Removal Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 μm | 3.02 × 10−4 | 2.28 × 10−5 | 1.35 × 10−5 | 4.17 × 10−5 | 86.20% |

| 50 μm | 3.02 × 10−4 | 2.51 × 10−5 | 1.20 × 10−5 | 3.13 × 10−5 | 89.64% |

| 70 μm | 3.02 × 10−4 | 2.30 × 10−5 | 1.08 × 10−5 | 2.70 × 10−5 | 91.07% |

| 90 μm | 3.02 × 10−4 | 2.12 × 10−5 | 9.94 × 10−5 | 4.76 × 10−5 | 84.26% |

| Bubble Size | Oily Wastewater Inlet (kg·s−1) | Oil Collection 1 (kg·s−1) | Oil Collection 2 (kg·s−1) | Treated Water Outlet (kg·s−1) | Oil Removal Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.03 | 3.02 × 10−4 | 2.28 × 10−5 | 1.22 × 10−5 | 3.36 × 10−5 | 88.87% |

| 0.05 | 3.02 × 10−4 | 2.51 × 10−5 | 1.20 × 10−5 | 3.13 × 10−5 | 89.64% |

| 0.07 | 3.02 × 10−4 | 2.62 × 10−5 | 1.11 × 10−5 | 2.24 × 10−5 | 92.61% |

| 0.09 | 3.02 × 10−4 | 2.71 × 10−5 | 1.04 × 10−5 | 1.42 × 10−5 | 95.31% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Xiao, X.; Yao, M.; Hai, L.; Men, H.; Jiang, W.; Liu, Y. Numerical Simulation Study of Air Flotation Zone of Horizontal Compact Swirling Flow Air Flotation Device. Processes 2025, 13, 3848. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123848

Zhang L, Xiao X, Yao M, Hai L, Men H, Jiang W, Liu Y. Numerical Simulation Study of Air Flotation Zone of Horizontal Compact Swirling Flow Air Flotation Device. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3848. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123848

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Lei, Xiaolong Xiao, Mingxiu Yao, Leiyou Hai, Huiyun Men, Wenming Jiang, and Yang Liu. 2025. "Numerical Simulation Study of Air Flotation Zone of Horizontal Compact Swirling Flow Air Flotation Device" Processes 13, no. 12: 3848. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123848

APA StyleZhang, L., Xiao, X., Yao, M., Hai, L., Men, H., Jiang, W., & Liu, Y. (2025). Numerical Simulation Study of Air Flotation Zone of Horizontal Compact Swirling Flow Air Flotation Device. Processes, 13(12), 3848. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123848