1. Introduction

1.1. Concept and Motivation

Against the macroeconomic backdrop in which medium- and long-term planning serves as an essential instrument for guiding national economic and social development [

1], China is accelerating the transformation of its energy system and the establishment of electricity market mechanisms. In 2025, the National Development and Reform Commission and the National Energy Administration jointly issued the Basic Rules for Electricity Market Metering and Settlement (NDRC Energy Regulation [2025] No. 976), marking the fundamental establishment of a unified national metering and settlement system. This provides institutional safeguards for the efficient operation of a multi-level electricity market [

1,

2]. With the large-scale integration of renewable energy units, the inherent volatility and intermittency of their output, coupled with the prevailing situation of high investment and low returns, have placed increasing demands on system flexibility and highlighted the urgent need for scalable and economically viable regulation resources. In this context, pumped storage power plants, as critical infrastructure for enhancing system flexibility, are experiencing significant development opportunities. According to Zhang et al. [

3], the installed capacity of pumped storage is expected to reach 62 GW by 2025 and further expand to 120 GW by 2030. However, as high-quality sites for pure pumped storage plants become increasingly scarce, developing hybrid pumped storage power plants (HPSPs)—which combine conventional hydropower stations with pumped storage units—has emerged as a key strategy to overcome site constraints [

4], enhance system flexibility, and support the efficient integration of renewable energy at scale [

5].

HPSPs integrate the generation capabilities of conventional hydropower units with the storage capabilities of reversible units. Compared with pure pumped storage plants, they offer wider regulation ranges and longer regulation cycles, enabling more flexible participation in electricity market transactions across multiple time scales. This allows HPSPs to deliver low-cost, reliable flexibility services to the power system, offering considerable comprehensive benefits and development potential.

1.2. Literature Review

At present, numerous scholars have conducted in-depth studies on the optimal scheduling of HPSPs. For example, Zhang et al. [

6] considered weekly time scales under extreme scenarios of sustained high and low output from wind and photovoltaic sources and demonstrated that HPSPs can effectively reduce the variance of residual load. Liu et al. [

7] proposed a short-term peak-shaving optimization model for HPSPs retrofitted from cascade hydropower plants, showing that they significantly reduce the peak–valley difference in residual load compared with conventional cascaded plants. Guo et al. [

8] analyzed changes in peak-shaving characteristics after retrofitting cascade hydropower plants into HPSPs in the Yellow River basin, emphasizing benefits for the coordinated development of basin-wide hydropower. Luo et al. [

9] investigated the joint operation of HPSPs and wind power, constructing detailed models for both conventional and pumped storage units to provide insights into multi-energy coordinated scheduling. These studies primarily focus on satisfying grid load requirements and exploring short- to medium-term scheduling strategies. However, they have not fully addressed the competitive participation of HPSPs alongside other generation resources within the unified national electricity market.

From another perspective, extensive research has been conducted on the interrelationships among capacity configuration, market mechanisms, and capacity pricing. Li et al. [

10] proposed an optimization method for the capacity allocation of wind–solar–hydro–storage systems based on coordination between capacity and spot markets, which effectively enhances reliable capacity and market revenues. Wang et al. [

11] explored unit capacity optimization in retrofitted cascade HPSPs to improve peak-shaving performance. Zhang et al. [

12] adopted a multi-energy complementary perspective, considering the coupling between water inflows and electricity generation, and proposed a two-stage decision-making method that coordinates operational optimization with capacity configuration under market rules. Ma et al. [

13] introduced a combined scenario generation method that captures uncertainties in renewable generation and water inflows, identifying optimal capacity configuration through life-cycle comprehensive evaluation. Wang, et al. [

14] further examined short-term multi-market participation of HPSPs in spot and ancillary service markets, developing optimization models under wet, normal, and dry hydrological scenarios. Nevertheless, these studies have mainly concentrated on planning and capacity decision-making stages, while research addressing post-construction market participation and bidding strategies remains limited.

Internationally, Birkeland and AlSkaif [

15] and Fatras et al. [

16] conducted comparative analyses of electricity market research in China and abroad, particularly contrasting the Nordic electricity market with that of China. Favaro et al. [

17] proposed a neural network-constrained optimization model for pumped storage scheduling, which generates physically feasible day-ahead dispatch plans in energy and reserve markets. Dogan et al. [

18] introduced a hybrid linear–nonlinear hydropower reservoir optimization model that improves initialization of nonlinear programming problems, significantly reducing iteration counts and computational time. While Wang Peng, Zhang Yushan, Ding et al. [

19] established a multi-agent game-theoretic framework analyzing PSP participation in electricity markets and identified three distinct game relationships, it does not address bidding strategies specific to HPSPs acting as independent market entities. Abdolahi et al. [

20] incorporated risk analysis into a congestion management model, enhancing the alignment of decisions with the risk preferences of practical system operators. Zhang et al. [

21] investigated the synergistic effects of a hybrid clean energy storage strategy combining pumped storage and hydrogen storage in multi-market participation. These studies offer valuable methods for solving pumped storage scheduling models, but lack evaluation of the benefits and value of HPSPs—either independently or in conjunction with other resources—in supporting the operation of modern power systems.

Existing research on HPSPs still faces the following limitations.

(1) Most studies focus on short-term spot markets, neglecting the long-term regulation capability and extended regulation cycles enabled by large storage capacities, thereby underestimating the revenue potential of HPSPs in medium- and long-term markets.

(2) In spot markets, conventional pumped storage is typically regarded as a “regulator” and acts as a price taker during scheduling. In contrast, HPSPs can participate in mid- to long-term contracts to hedge against price volatility, and their influence on price formation should not be overlooked; however, related mechanisms have not been systematically examined.

(3) In joint operations with renewable energy, existing studies emphasize the overall benefits of the alliance but often disregard the individual economic performance of HPSPs as independent market participants.

1.3. Novelties and Contribution

In light of the above background and research gaps, this paper introduces mid- to long-term contracts for difference (CfDs) and investigates the operational and bidding strategies of HPSPs in day-ahead energy and frequency regulation markets under a full-capacity bidding framework in a high-penetration wind and solar environment.

The introduction of CfD establishes a financial linkage that naturally couples medium and long-term markets with spot electricity markets. The financial nature of CfD enables generators to lock in long-term price signals while retaining full physical operational flexibility in the spot market, thereby effectively addressing the prevalent research gap of focusing exclusively on short-term market operations [

22]. Furthermore, the coordinated operation across medium/long-term and spot markets empowers plants to develop more strategic bidding behaviors based on the secured baseline revenue from CfD, overcoming the conventional simplification of treating them as price-takers. This integrated approach enhances bidding flexibility in the spot market and subsequently expands the plant’s capability to participate in ancillary service markets such as frequency regulation, enabling coordinated optimization across multiple temporal scales and market products, thereby significantly improving overall market competitiveness and profitability [

23].

The main contributions of this paper are reflected in the following three aspects:

(1) Proposed Methodology

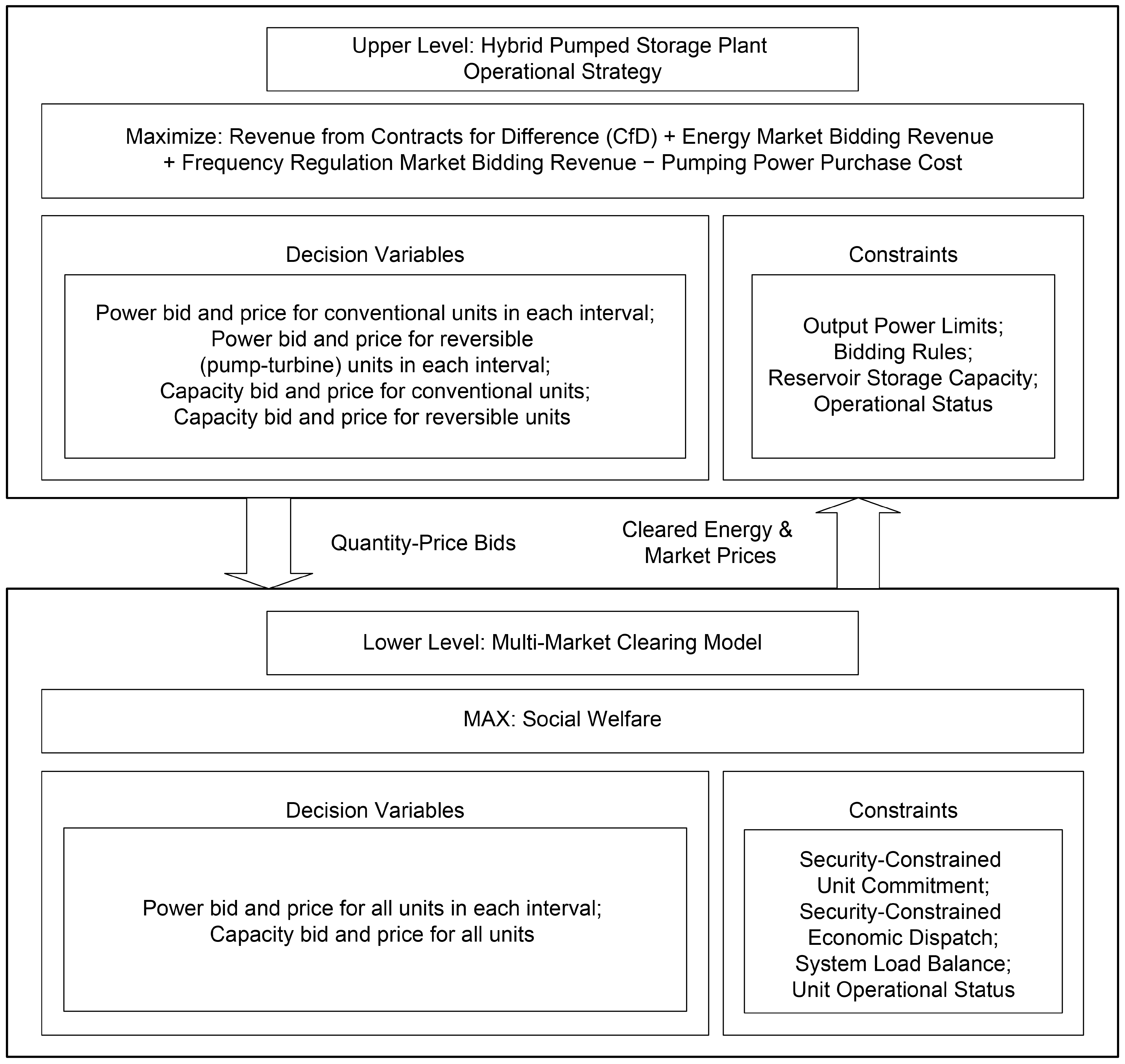

A novel bi-level optimization framework is developed to formulate the coordinated multi-market operation of HPSPs, explicitly incorporating mid- to long-term CfDs. The upper level maximizes plant revenue by integrating spatiotemporal coupling characteristics, short-term operational constraints, and non-decreasing stepwise bidding curves. The lower level minimizes total social cost through a joint clearing mechanism for spot energy and frequency regulation markets, incorporating CfDs settlement rules.

(2) Multi-Market Coupling Mechanism

The proposed model seamlessly integrates mid- to long-term, day-ahead energy, and frequency regulation markets under a full-capacity bidding framework. It effectively ad-dresses the coupling challenges between multiple market mechanisms and complex operational constraints, enabling HPSPs to optimize capacity allocation and bidding strategies across heterogeneous temporal scales and market products.

(3) Model Validation and Results

A hybrid solution strategy combining commercial solvers with genetic algorithms is implemented to efficiently solve the complex bi-level model. Case studies demonstrate the model’s effectiveness, quantifying how ancillary service participation enhances profitability. Results show significantly improved market performance, with bidding behaviors aligning closely with price dynamics, validating the model’s practical applicability.

1.4. Paper Organization

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 establishes the multi-market framework, detailing the coordination mechanism between medium- and long-term CfDs and short-term markets.

Section 3 formulates the bi-level optimization model, with the upper level focusing on HPSP revenue maximization and the lower level addressing social welfare optimization.

Section 4 elaborates on the hybrid solution methodology, particularly the NSGA-II implementation and parameter configuration.

Section 5 presents comprehensive case studies validating the model’s effectiveness and analyzing the economic impact of multi-market participation. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes key findings and

Section 7 suggests future research directions.

4. Model Solution Approach

The proposed bi-level model constitutes a multi-stage optimization problem incorporating complex hydroelectric and power system constraints. To solve this problem efficiently, a hybrid approach is adopted that integrates the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) with a commercial mathematical programming solver.

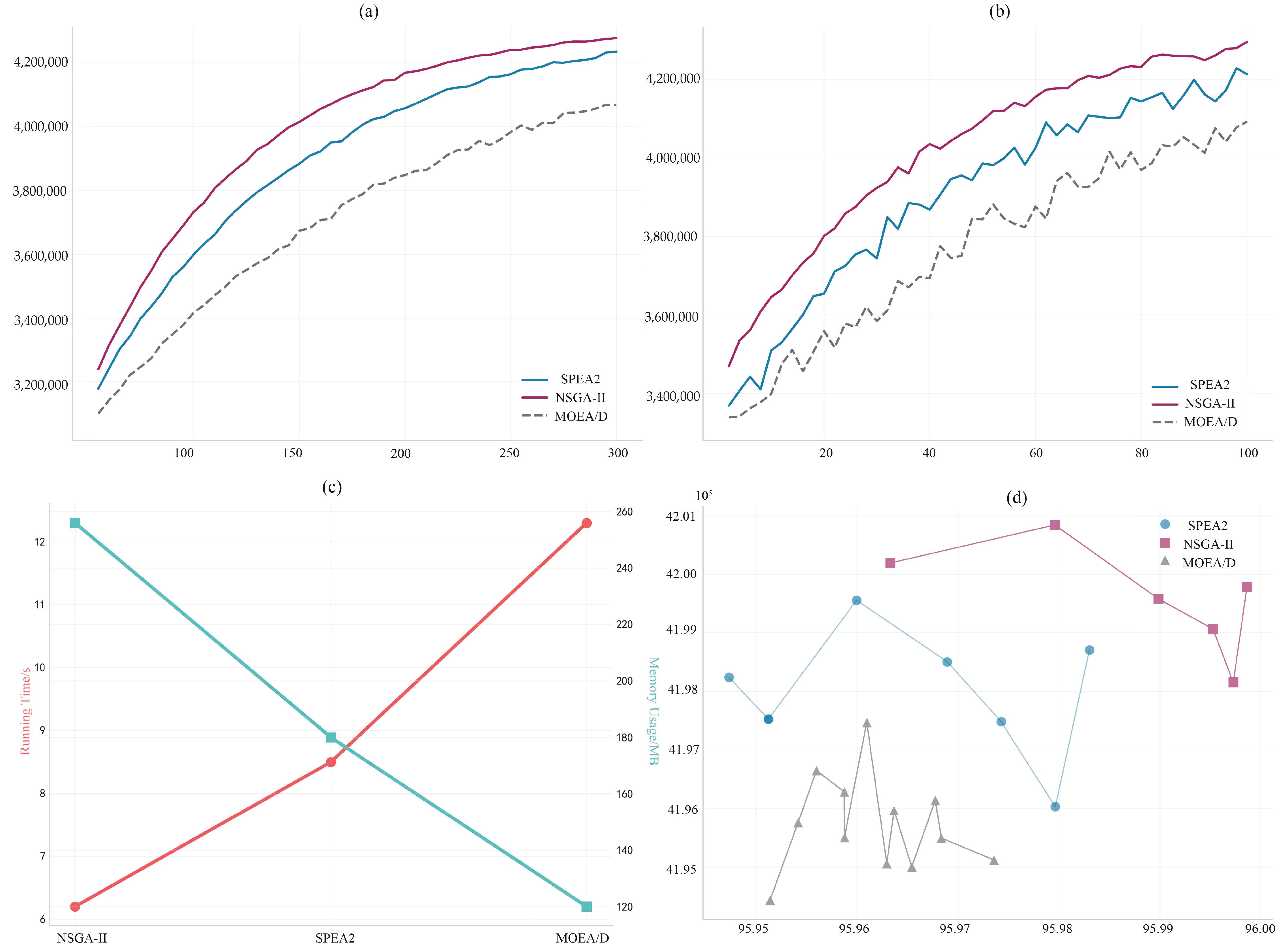

In solving this bi-level electricity market optimization problem, the NSGA-II algorithm demonstrates superior applicability compared to MOEA/D and SPEA2. Unlike the decomposition-based mechanism of MOEA/D, NSGA-II employs a non-dominated sorting approach that requires no predefined weight vectors, enabling more natural handling of the complex trade-offs between revenue and social costs while avoiding solution bias caused by improper weight settings [

42]. Compared to SPEA2, NSGA-II features a fast non-dominated sorting mechanism with lower computational complexity, significantly enhancing solution efficiency while maintaining population diversity—a crucial advantage for computationally expensive bi-level optimization problems. Furthermore, the uniformly distributed Pareto front generated by NSGA-II’s crowding distance operator, combined with its robustness in handling complex constraints, makes it an ideal choice for solving such multi-objective electricity market problems [

43].

Specifically, the NSGA-II algorithm is used to iteratively update the generation and pumping schedules, as well as the bidding strategies, of the HPSP, while the market clearing problem is solved using a commercial solver (e.g., CPLEX) to determine energy and ancillary service clearing prices and quantities.

By maintaining a diverse Pareto-optimal solution set, the method captures the trade-offs between the upper- and lower-level objectives. The application of an elitist strategy and fast non-dominated sorting ensures that the evolutionary process consistently advances toward high-quality solution regions. A crowding-distance operator is employed to preserve population diversity and prevent premature convergence. In addition, a two-layer chromosome encoding scheme is designed to directly represent the coupling between upper-level bidding strategies and lower-level unit commitment decisions. A constraint-repair mechanism is applied to efficiently manage complex operational constraints, such as ramping limits, minimum up/down times, and reservoir balance, thereby ensuring that the resulting schedules are both economically efficient and technically feasible within a finite number of iterations.

The solution procedure is as follows.

Set the population size N = 100, maximum number of generations , crossover probability , and mutation probability . Randomly generate the initial population, where each individual represents a bidding strategy of the HPSP: including generation, pumping, and ancillary service offers over the entire scheduling horizon.

- 2.

Inner-Level Optimization (Social Cost Minimization)

For each individual in the outer population, fix the bidding strategy () as boundary conditions, and solve the lower-level model using a MILP solver. The solution yields unit commitment and dispatch decisions , , spot market clearing prices , ancillary service prices , and total social procurement cost C.

- 3.

Computation of Bi-Level Objective Values

The upper-level objective (HPSP revenue) is given by:

The lower-level objective is the total social cost C.

Construct the bi-objective minimization vector:

- 4.

Fast Non-Dominated Sorting

Perform fast non-dominated sorting on the population to identify Pareto dominance relationships and classify individuals into Pareto fronts, where Rank 1 corresponds to the best non-dominated front.

- 5.

Crowding Distance Calculation

For individuals in the same Pareto front, compute the normalized crowding distance in the objective space:

- 6.

Selection

Apply binary tournament selection: randomly select two individuals and choose the one with the lower Rank; if both individuals have the same Rank, select the one with the greater crowding distance.

- 7.

Genetic Operators

Simulated Binary Crossover:

- 8.

Elitist Preservation

Merge the parent and offspring populations (resulting in a total size of 2N), perform non-dominated sorting on all individuals, and construct the next generation by selecting individuals in order of increasing Rank. If multiple individuals share the same Rank, prioritize those with higher crowding distances.

- 9.

Termination Criterion

The algorithm terminates when either the maximum number of generations () is reached or the Pareto front converges, as indicated by a hypervolume change rate below ϵ. If neither condition is met, return to Step 2 and continue the evolutionary process.

5. Case Study and Numerical Analysis

5.1. Parameter Settings

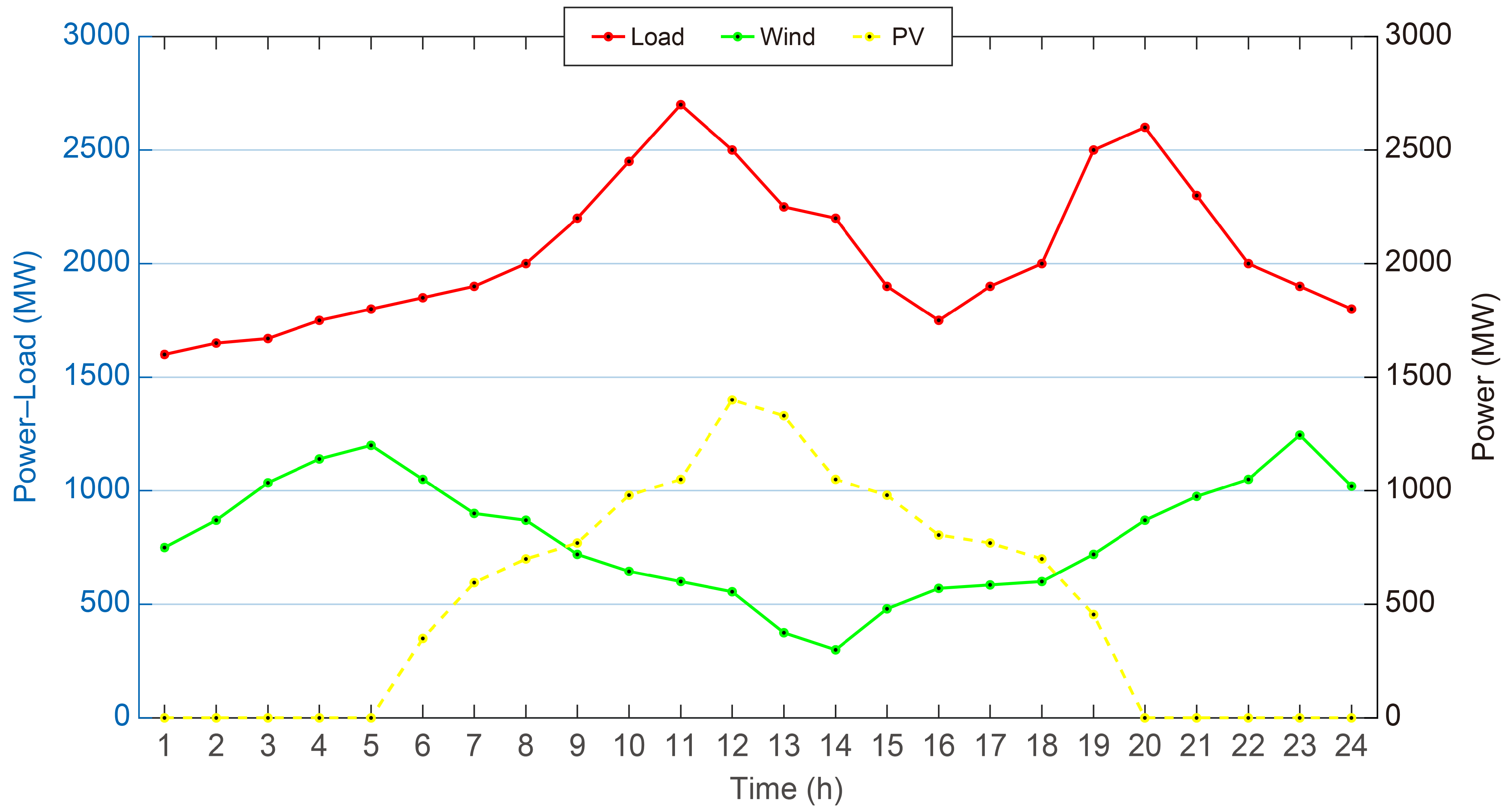

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed model, a 24 h scheduling horizon is considered. The system load profile is proportionally scaled to match the total system generation capacity. An HPSP, along with nearby wind farms, photovoltaic (PV) plants, and thermal power plants, is selected as the case study system.

The HPSP reservoir has a total storage capacity of , with a normal water level of 355 m and a dead water level of 330 m. The station is equipped with conventional generating units with a total installed capacity of 500 MW and reversible units with a capacity of 300 MW. A bilateral long-term CfD is assumed, with a contracted electricity price of 450 CNY/MWh and a contracted energy quantity of 3840 MWh. These contractual parameters were determined based on historical CfD data from the normal water storage period of the plant, representing characteristic values for contract price and volume.

The system also includes three thermal power plants. Due to their relatively high generation costs, their bidding prices are set significantly higher than those of other market participants. To reflect cost structure heterogeneity, each thermal power plant submits energy bids equal to its installed capacity. Detailed parameters of the thermal units are presented in

Table 1.

Additionally, one PV plant and one wind farm are connected to the system. Their stochastic output characteristics are shown in

Figure 3. On the demand side, only power quantities are submitted, without price bids, and the declared power demand follows the forecasted load profile.

The spot market bidding curve is designed with reference to actual market conditions in a specific region. The bidding and offering rules for the frequency regulation market are summarized in

Table 2. For frequency regulation units that do not participate in market bidding, a default bid price of 6 CNY/MW is assumed.

5.2. Comparative Analysis of Algorithm Performance

Figure 4 presents a comparative analysis of the performance metrics among three multi-objective evolutionary algorithms: MOEA/D, NSGA-II, and SPEA2. The results demonstrate that although NSGA-II requires the highest memory consumption, it achieves superior convergence speed and produces higher-quality Pareto-optimal solutions compared to the other two algorithms. These findings validate the rationality of selecting NSGA-II for solving the proposed bilevel optimization problem and offer valuable insights for algorithm design in addressing similar complex optimization challenges in the future.

5.3. Market Clearing Results of the Power Plant

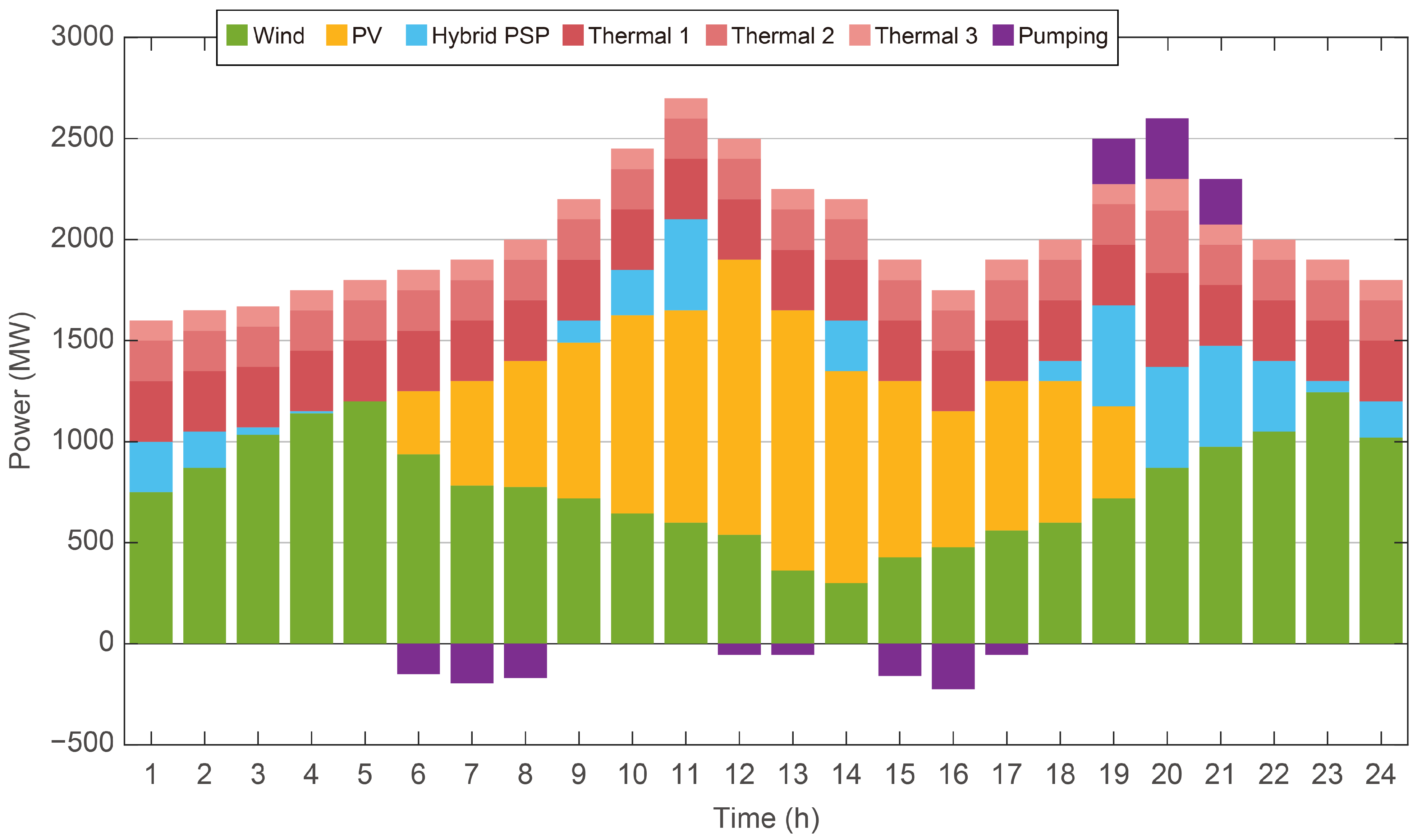

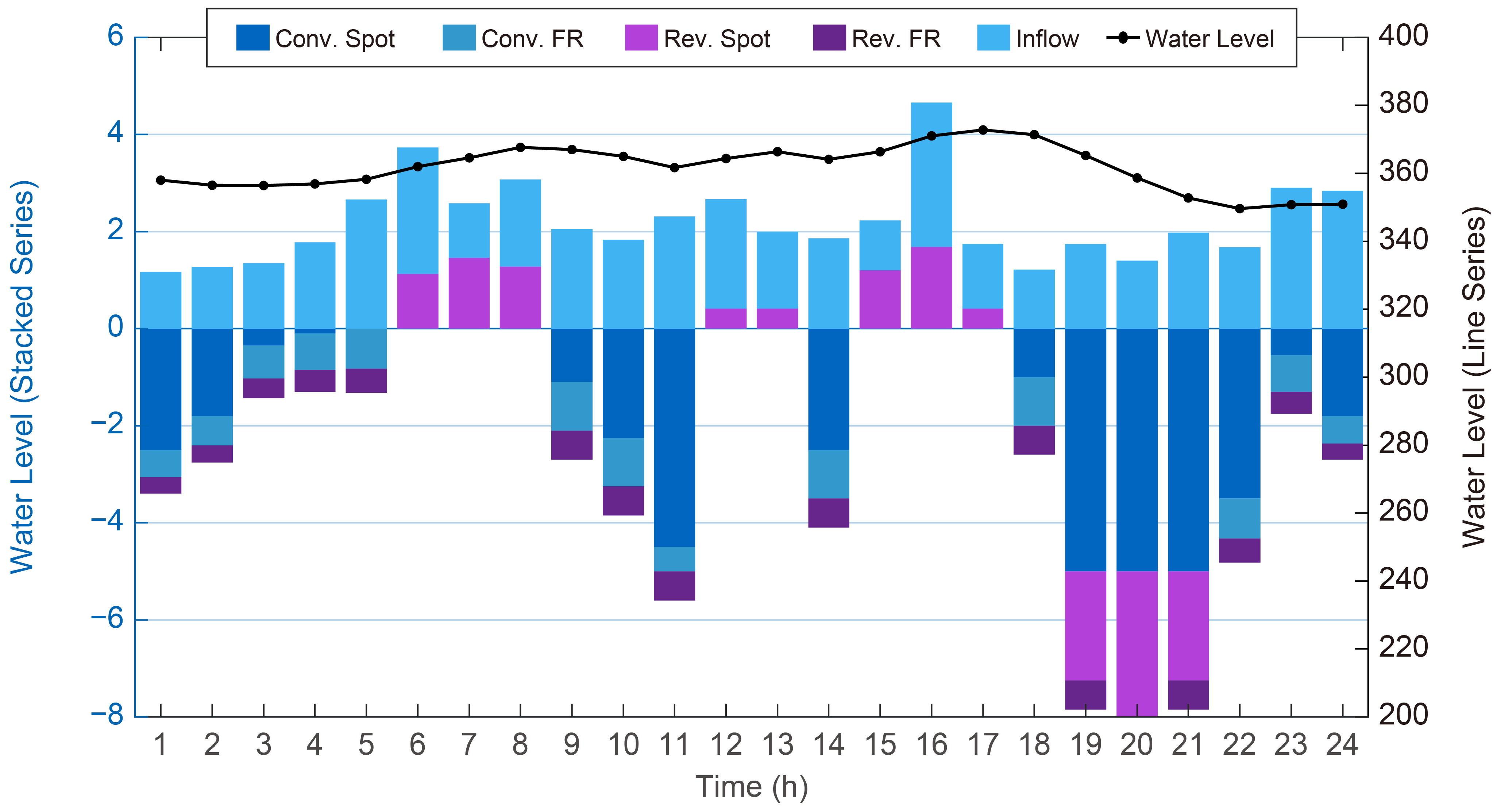

The awarded electricity quantities of different units in the spot and frequency regulation markets are shown in

Figure 5. As illustrated, when wind and solar generation account for 63.17% of the total market share, thermal power units operate at their minimum output levels during 95.89% of the scheduling periods. From 01:00 to 05:00, as wind power output gradually increases, conventional hydropower units reduce their generation to prioritize the consumption of renewable energy. Between 06:00 and 08:00, PV generation begins, and although wind generation decreases slightly, the increase in load demand is insufficient to absorb the additional PV output. This results in excess supply and a decline in electricity prices, during which the reversible units shift to pumping mode, with an average pumping power of 170 MW. From 09:00 to 11:00, the rising demand cannot be fully met by thermal and renewable generation alone, requiring conventional hydropower units to increase their output. During the evening peak from 18:00 to 20:00, when demand reaches its highest level and PV generation phases out, the conventional units of the HPSP operate at full capacity. Meanwhile, the reversible units bid near their rated capacity and successfully clear the market during peak hours.

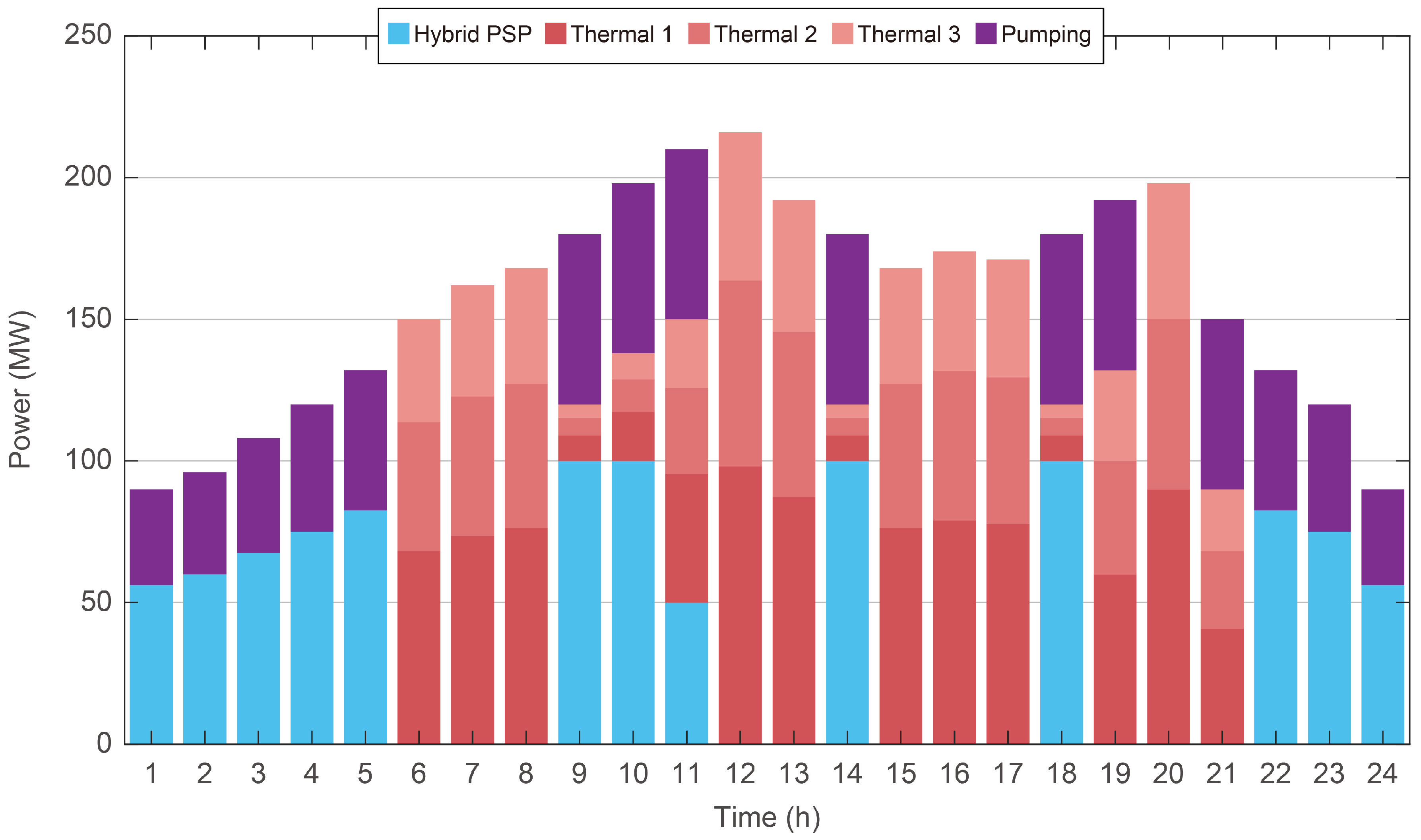

In the frequency regulation market,

Figure 6 shows that hydropower units account for 46.54% of the total market share. Specifically, conventional hydropower units participate at their maximum declared capacity of 100 MW during 66.7% of the time periods, after fulfilling renewable energy absorption requirements. The reversible units also receive frequency regulation awards whenever they are not operating in pumping mode. The only exception occurs at 20:00, when both conventional and reversible units are fully committed in the spot market; under these conditions, frequency regulation is exclusively provided by thermal units.

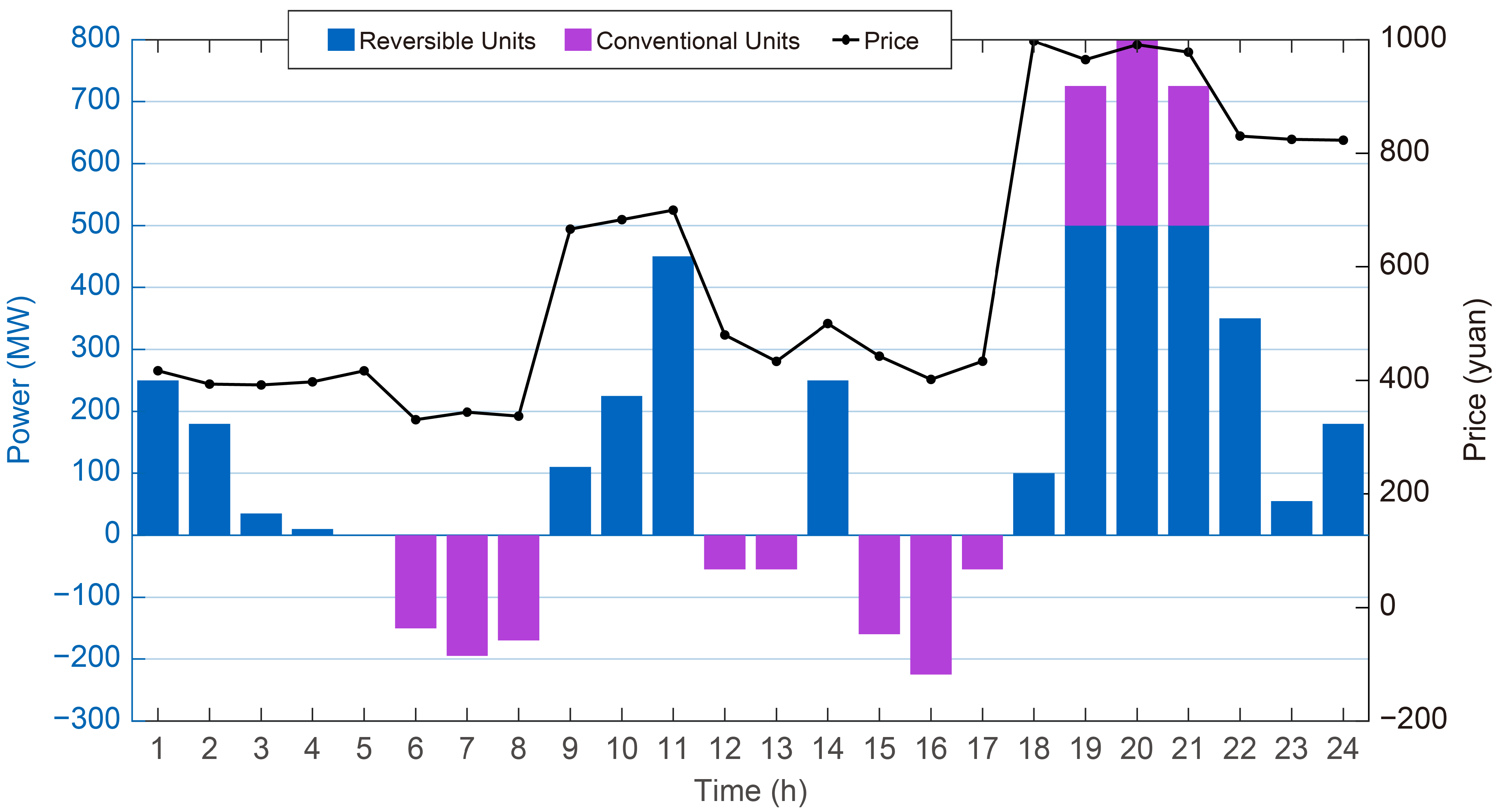

In the spot market,

Figure 7 illustrates that the HPSP generally adopts a strategy of “pumping during low-price hours and generating during high-price hours.” Between 11:00 and 17:00, the HPSP adjusts its operation flexibly in response to real-time price fluctuations, maintaining a dispatch pattern closely aligned with the price trend. From 19:00 to 21:00, after the complete absorption of renewable energy and with thermal units operating at their minimum output levels, the remaining demand is met through a combination of thermal ramp-up and increased hydropower generation. Due to their lower bidding prices, hydropower units are prioritized in market clearing. During this period, both the conventional and reversible units of the HPSP operate at full generation capacity.

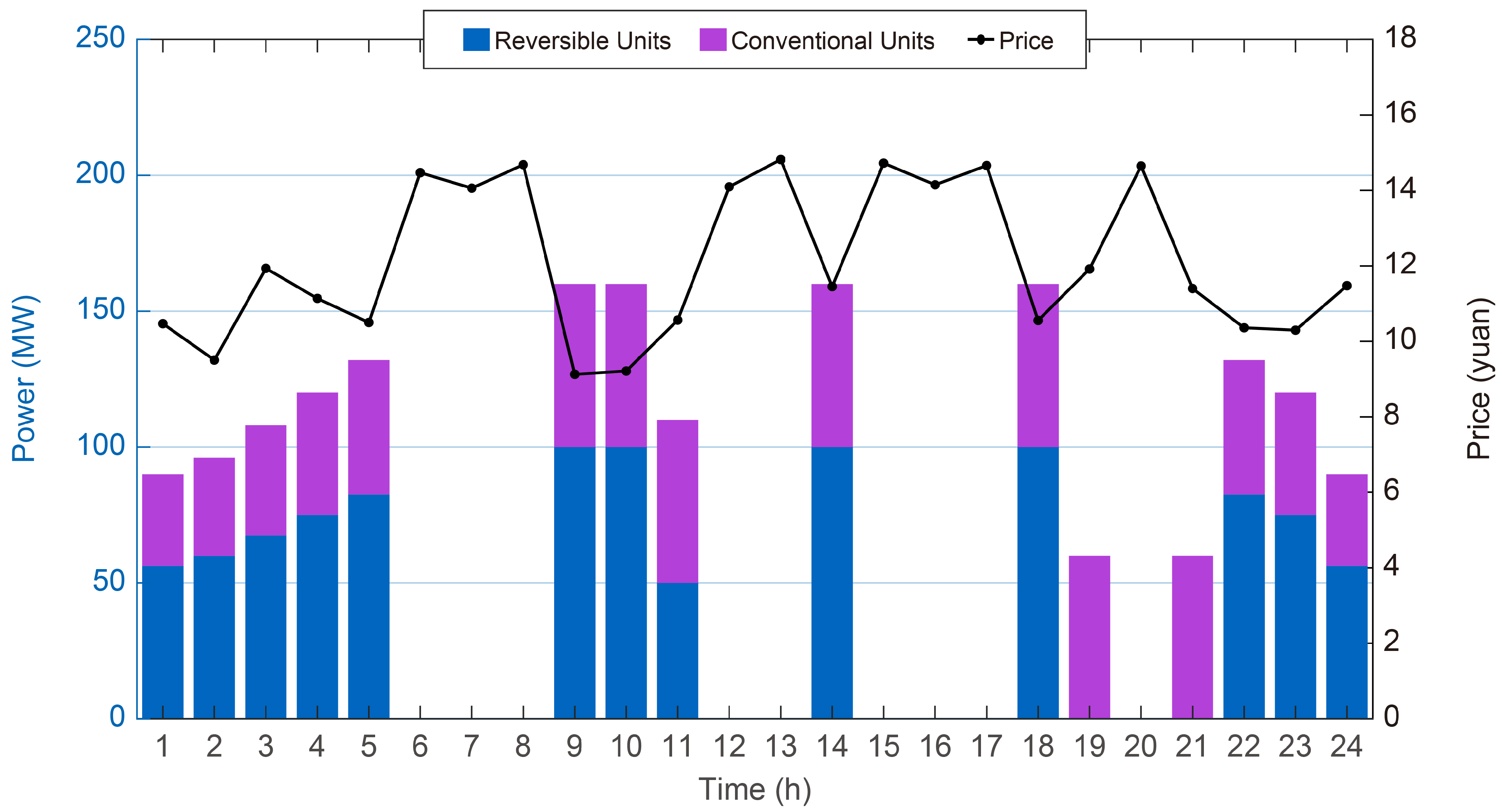

In the frequency regulation market,

Figure 8 indicates that, due to operational constraints, the HPSP cannot provide frequency regulation services during pumping periods. As a result, such services are fully provided by thermal units, leading to relatively higher clearing prices. However, during generating periods, both conventional and reversible units of the HPSP capture a dominant share of the regulation market owing to their operational flexibility and lower regulation costs. Although their bidding prices are slightly above the default clearing value of 6 CNY/MW, they remain substantially lower than those of thermal units, highlighting their competitive advantage and economic efficiency.

5.4. Reservoir Water Level Variations

As shown in

Figure 9, the overall operational strategy of the HPSP is to pump water during periods of abundant renewable generation and low electricity prices, and to release water for generation during peak demand hours—thus achieving temporal energy shifting and value enhancement. Before 08:00, system demand remains low while wind and solar output continues to increase. During this time, the reversible units pump water in conjunction with natural inflows, raising the upper reservoir level to a first peak of approximately 367.6 m. From 09:00 to 11:00, as system demand rises, both conventional and reversible units generate simultaneously, causing the water level to decline to 361.2 m. During 12:00–14:00, the water level stabilizes around 365 m. Between 15:00 and 17:00, reduced demand allows the reversible units to resume pumping, pushing the reservoir level to a second peak of approximately 372.7 m. After 18:00, with PV generation ceasing and limited additional wind output, system demand reaches its evening peak. Both conventional and reversible units operate continuously, lowering the reservoir level to 354.5 m—only 0.97% below its initial level. This operational trajectory demonstrates the multi-timescale flexibility of the HPSP and underscores its critical role in supporting renewable energy integration.

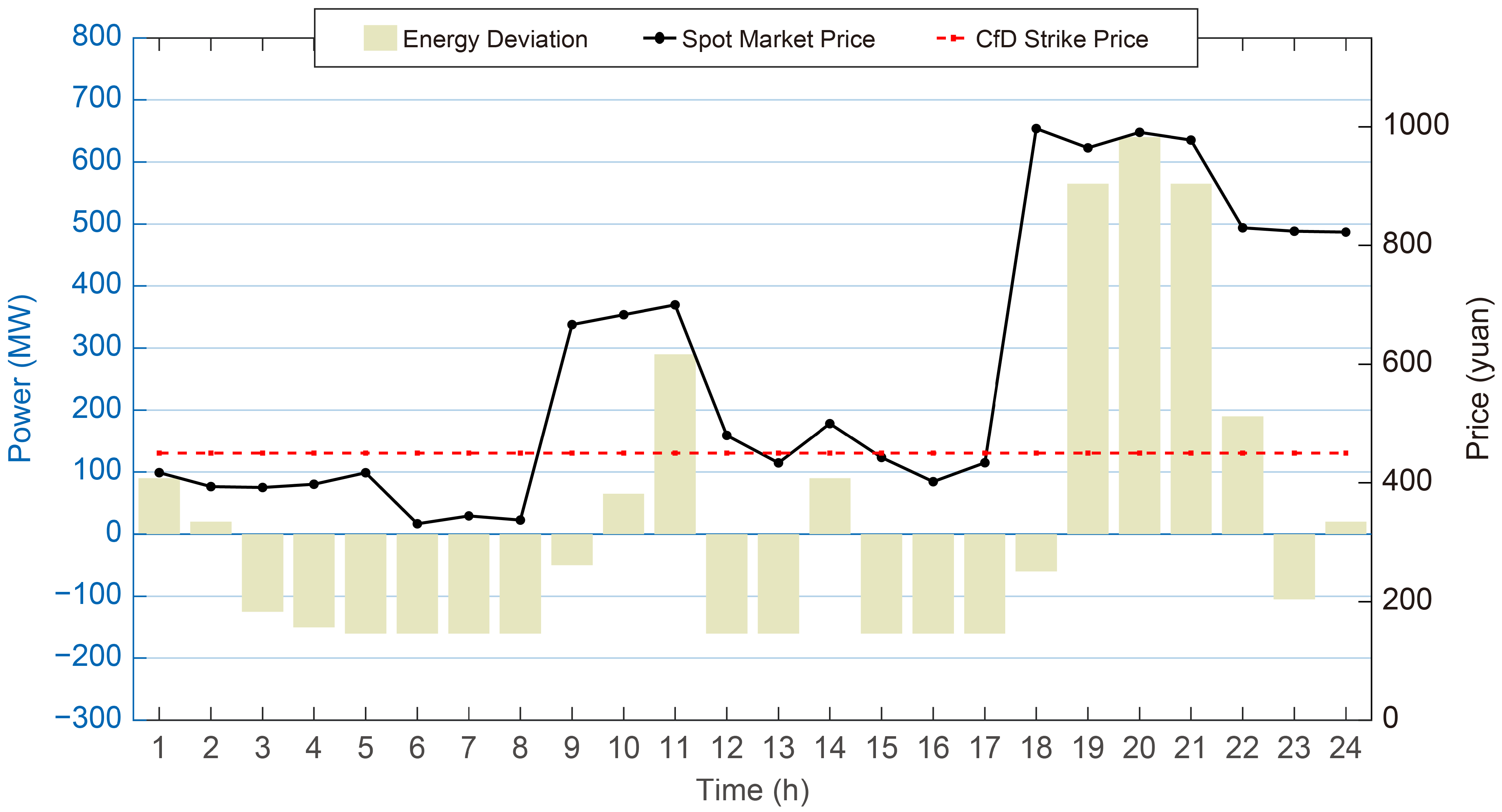

5.5. Contract for Difference Performance Analysis

As illustrated in

Figure 10, the HPSP exhibits four typical CfD compliance states under varying operating conditions.

03:00–08:00: The spot price is lower than the CfD contract price, and the HPSP does not fulfill its contractual output. During this period, abundant renewable generation suppresses market prices. According to CfD settlement rules, the shortfall is treated as though the plant sold electricity at the contract price and repurchased the shortfall at the lower spot price—thereby earning a profit from the price differential.

09:00 and 12:00: Although spot prices exceed the contract price, the HPSP is unable to meet the contracted output. This situation typically arises during periods of load growth when renewable generation dominates but remains insufficient. In such cases, the shortfall results in financial losses, as electricity must be procured at higher spot prices and settled at the lower contract price.

01:00–02:00: The spot price is below the contract price, and the HPSP successfully fulfills its contractual obligations. With lower renewable output, hydropower generation supplies the required energy. Any surplus generation beyond the contracted quantity is sold at the prevailing, lower spot price.

19:00–22:00: The spot price exceeds the contract price, and the HPSP fully satisfies its contractual obligations. This period corresponds to the evening demand peak, characterized by diminished renewable output and heightened system flexibility requirements. Surplus energy is sold at high spot prices, resulting in substantial profits and demonstrating the market incentive of “more generation, more profit.”

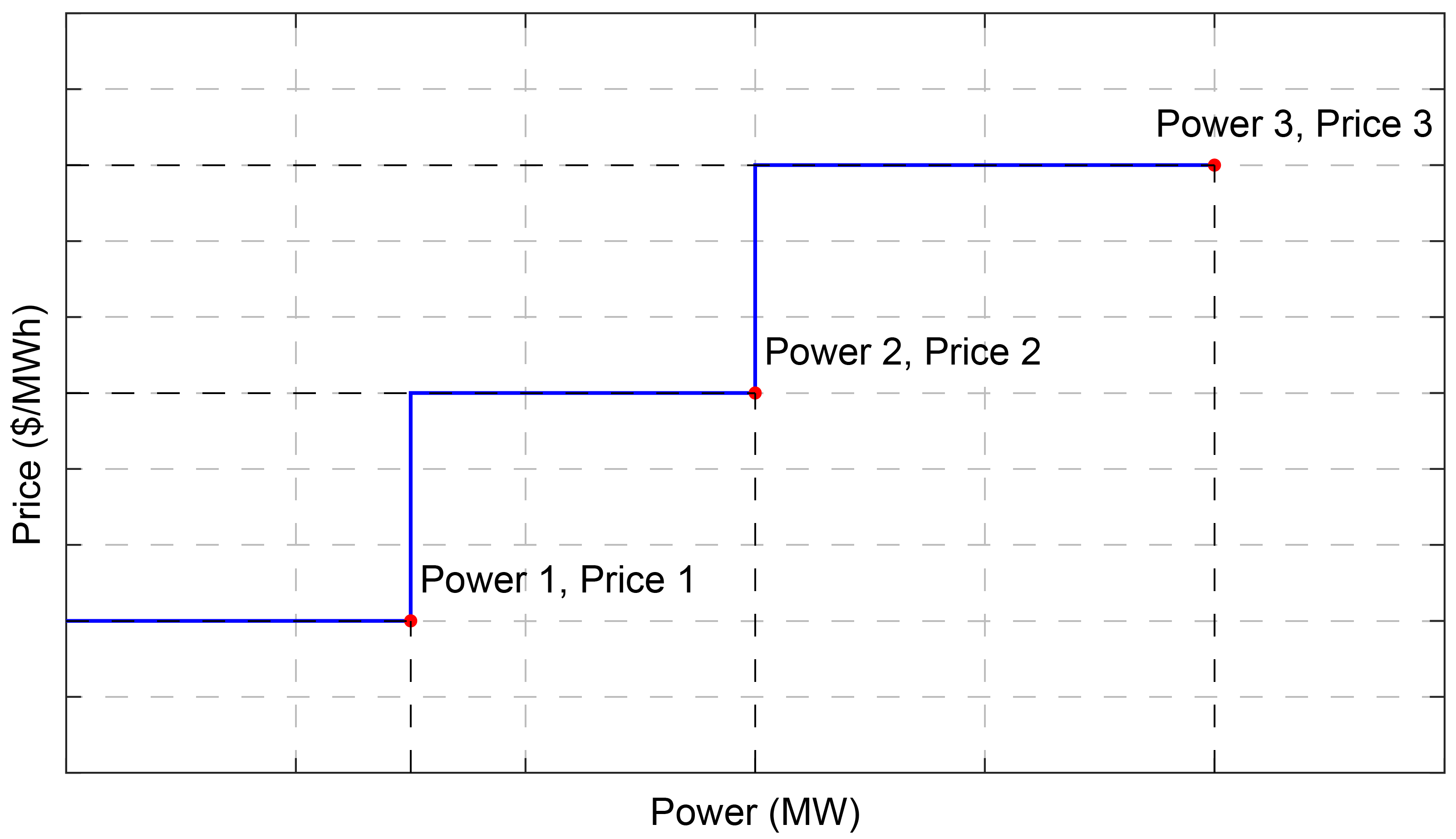

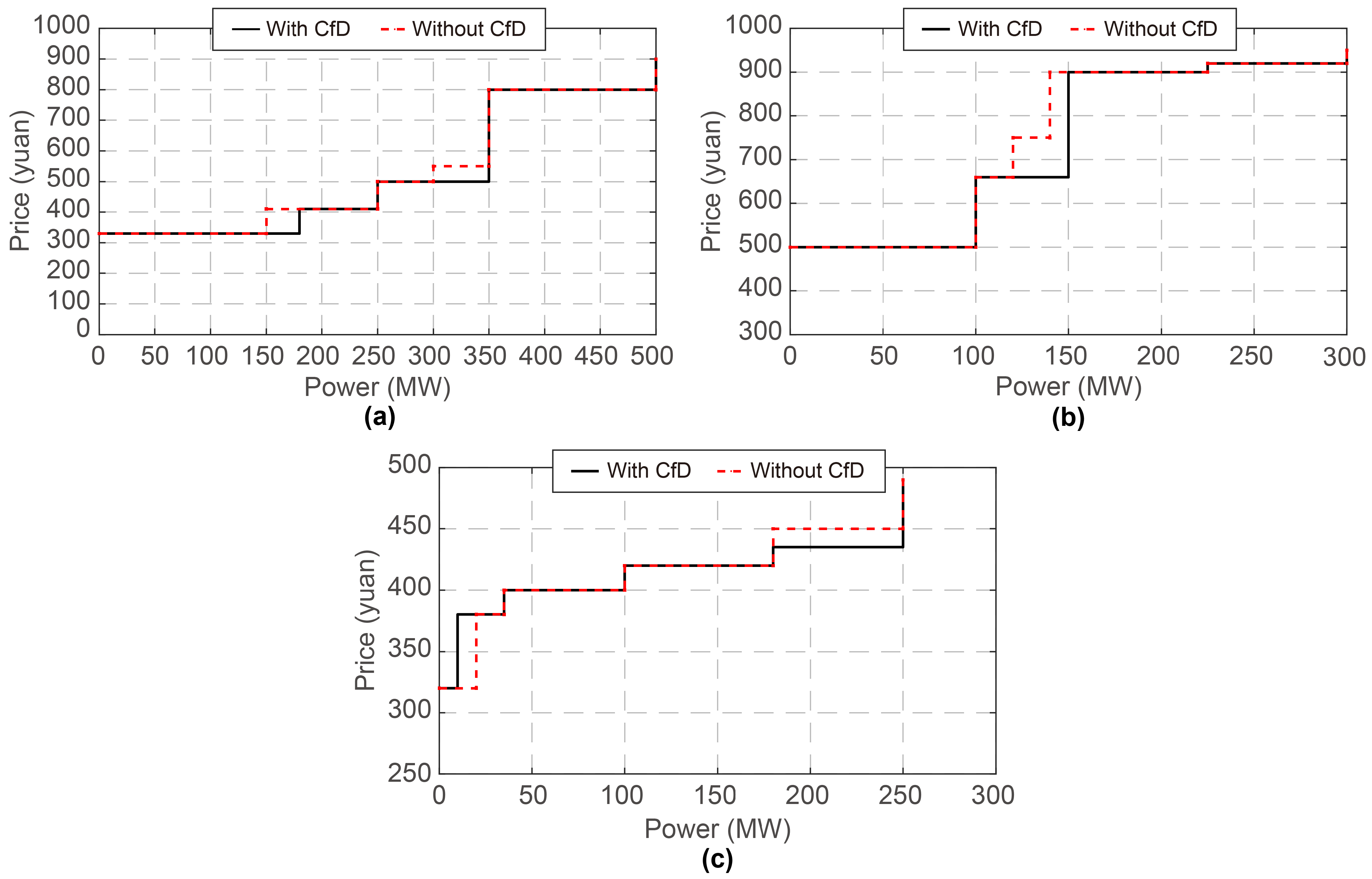

As illustrated in

Figure 11, the number and placement of steps in the bidding curves vary, reflecting differences in both output levels and pricing strategies. Although all models aim to maximize overall utility, the resulting bidding behaviors differ significantly due to the distinct factors considered within each model. Notably, the day-ahead bidding model that incorporates CfD settlement rules has a substantial impact on bidding strategies.

Specifically, aside from pumped storage units—which avoid bidding during off-peak, low-price hours—conventional units exhibit distinct peak–valley bidding patterns depending on the presence of CfDs. For both conventional and pumped storage units, in the absence of CfDs, bidding strategies during peak periods tend to be more aggressive, as there is no contractual price guarantee and plants must rely more heavily on capturing peak–valley price spreads to generate revenue. In contrast, during off-peak periods, the bidding flexibility of conventional units is relatively constrained, resulting in flatter bidding curves.

5.6. Sensitivity Analysis of Revenue to Hydrology and Contract for Differences

Table 3 summarizes the profitability of the HPSP under various market participation scenarios, including CfD, spot, and frequency regulation markets. Results indicate that the plant earns 3.2268 million CNY through participation in the spot market alone. When both CfD and spot market participation are considered, total revenue increases to 4.2962 million CNY. After deducting pumping costs of 0.4095 million CNY, the net revenue rises substantially—representing an improvement of approximately 33.2% compared with the spot-only scenario. Additionally, participation in the frequency regulation market contributes 0.0179 million CNY.

Table 4 illustrates the adaptive bidding strategies employed by the HPSP across different hydrological periods. During the dry season, limited water inflow prompts a defensive strategy, where the plant significantly increases its mid- to long-term CfD allocation to secure stable revenue and mitigate market risks. Consequently, contract-based revenue reaches its peak while spot market earnings remain minimal. In contrast, the wet season, characterized by abundant water resources, facilitates an aggressive strategy. The plant reduces its contracted energy volume to enhance operational flexibility, enabling it to capitalize on high-price opportunities in the spot market and maximize spot revenue. A balanced approach is adopted during normal water storage periods, aiming to harmonize the stability of contracted revenue with the profit potential of the spot market. This study underscores the necessity for the plant to dynamically optimize its energy allocation based on hydrological forecasts to achieve maximum lifecycle profitability.

Table 5 and

Table 6 reveal a significant trade-off between the proportion of CfD-committed energy and the revenue structure of the plant. As the share of contracted energy increases, the corresponding contract revenue grows linearly; however, this marginal gain is counterbalanced by an accelerated decline in spot market revenue. The underlying mechanism is that a higher CfD allocation reduces the flexible energy capacity available for arbitrage (e.g., pumping during low-price periods and generating during high-price periods), thereby constraining the plant’s ability to exploit real-time price fluctuations and capture excess profits. Thus, under given market conditions, an optimal CfD energy ratio exists that maximizes total revenue. Over-reliance on the certainty of contracted volumes may consequently lead to potential losses in overall profitability.

From a structural standpoint, the CfD and spot markets serve as the primary revenue sources, jointly accounting for over 99% of total income. This underscores the central role of the energy market in determining overall profitability. The pumping costs highlight the need for operational efficiency, while ancillary services—although contributing a smaller portion—offer supplementary value by enhancing system flexibility. Overall, the coordinated participation of HPSPs in “CfD + spot + ancillary service” markets not only maximizes economic returns but also provides a stable path toward cost recovery and sustainable operation. Therefore, it is recommended that HPSPs optimize pumping efficiency and strategically coordinate across multiple electricity markets to enhance profitability.

6. Conclusions

a. The proposed bi-level optimization model effectively demonstrates the feasibility and economic advantages of HPSPs participating in coordinated multi-market operations—including long-term contracts, spot markets, and frequency regulation—within a CfD framework. The model offers a robust theoretical foundation and decision-making support for maximizing HPSP revenues under complex market conditions.

b. Simulation results indicate that the integration of CfDs significantly enhances the revenue-generating potential of HPSPs in the spot market, with profits increasing by approximately 33.2% compared to the spot-only participation scenario. By securing contracted electricity volumes and prices, CfDs serve as effective financial instruments for hedging against spot price volatility and improving overall profit stability.

c. In power systems with high penetration of wind and solar generation, HPSPs demonstrate strong adaptability and operational flexibility. They can absorb surplus renewable energy during low-demand periods and release stored energy during peak hours, thereby contributing to system balance and supporting the secure, reliable operation of the grid.