Trajectory Tracking Control of Hydraulic Flexible Manipulators Based on Adaptive Robust Model Predictive Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

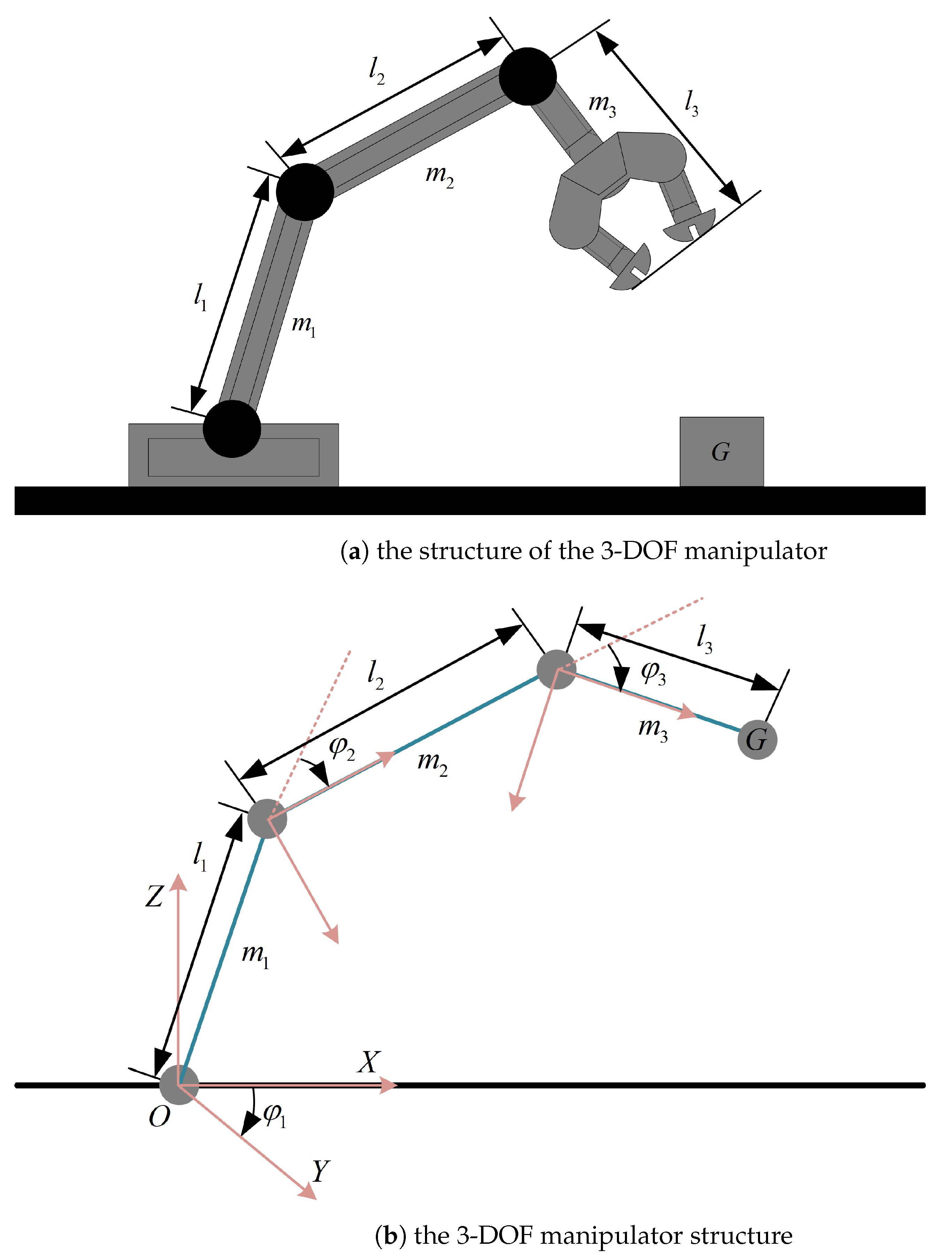

2. Modeling

2.1. Dynamic Model of the Three-Degree-of-Freedom Manipulator

2.2. Discrete State-Space Equation of the Three-Degree-of-Freedom Manipulator

3. Adaptive Parameter Estimation

3.1. Adaptive Update Law for Model Parameters

3.2. Stability Analysis

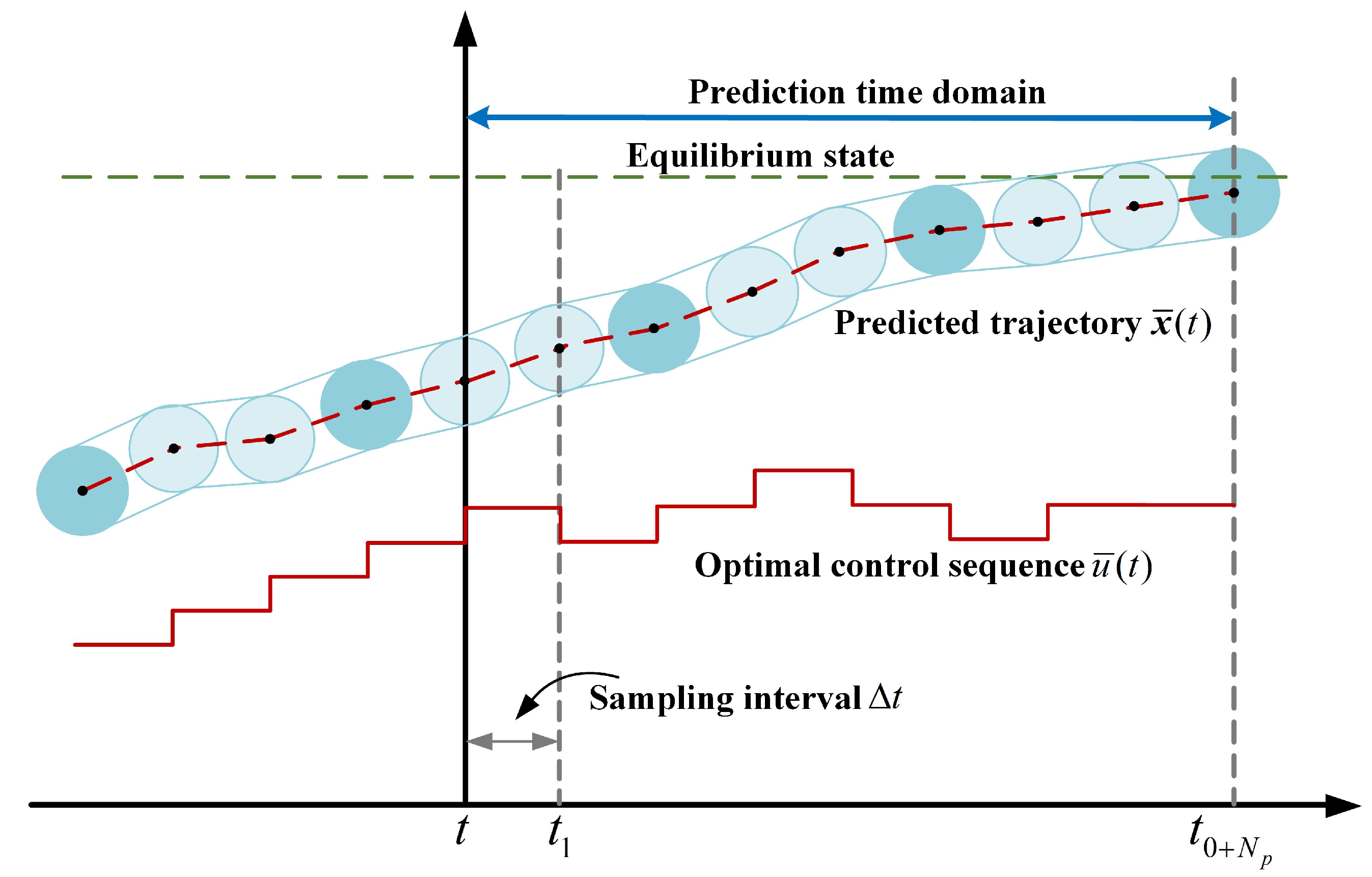

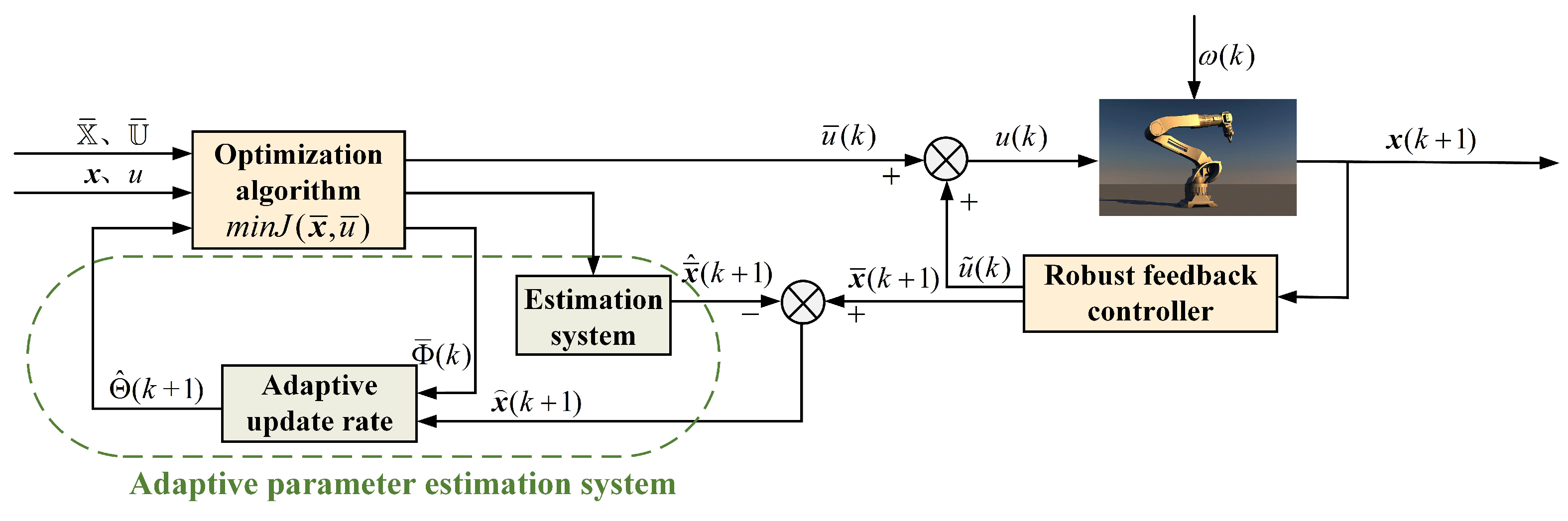

4. Adaptive Robust Model Predictive Controller

4.1. Design of Adaptive Robust Predictive Controller

4.2. Stability Analysis

5. Simulation Experiments

5.1. Simulation Parameter Settings

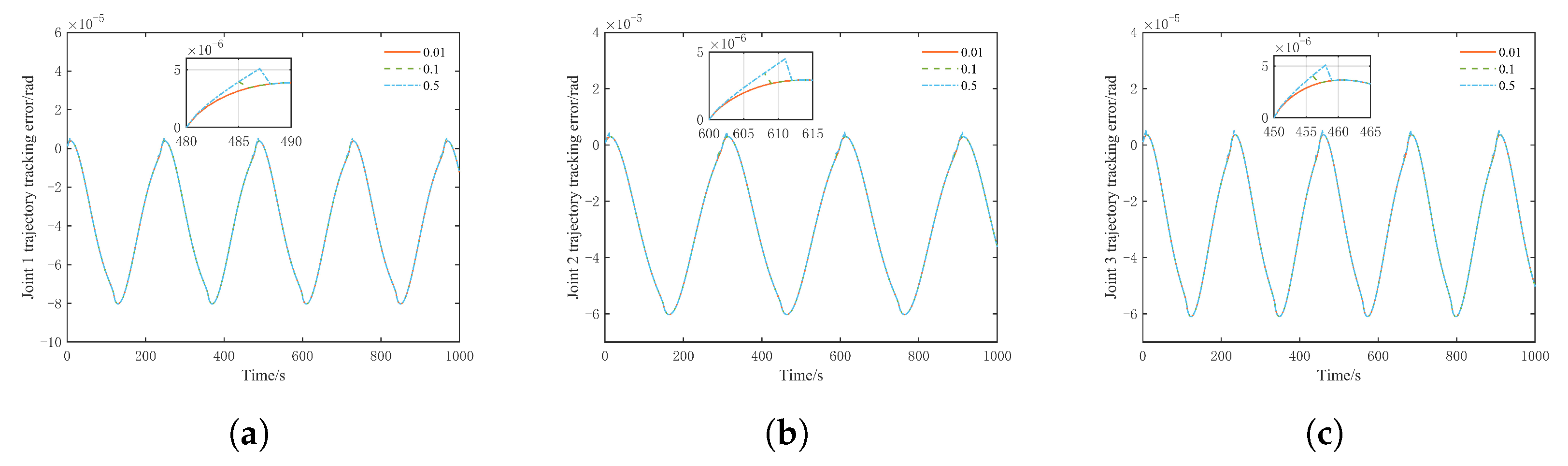

5.2. Parameter Discussion Experiment

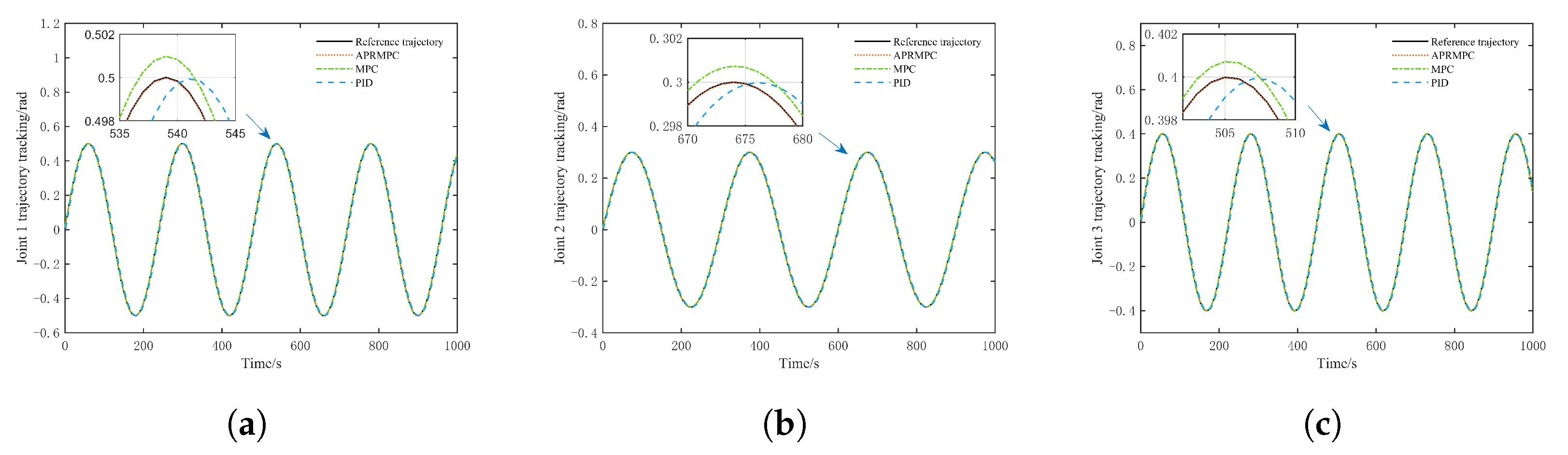

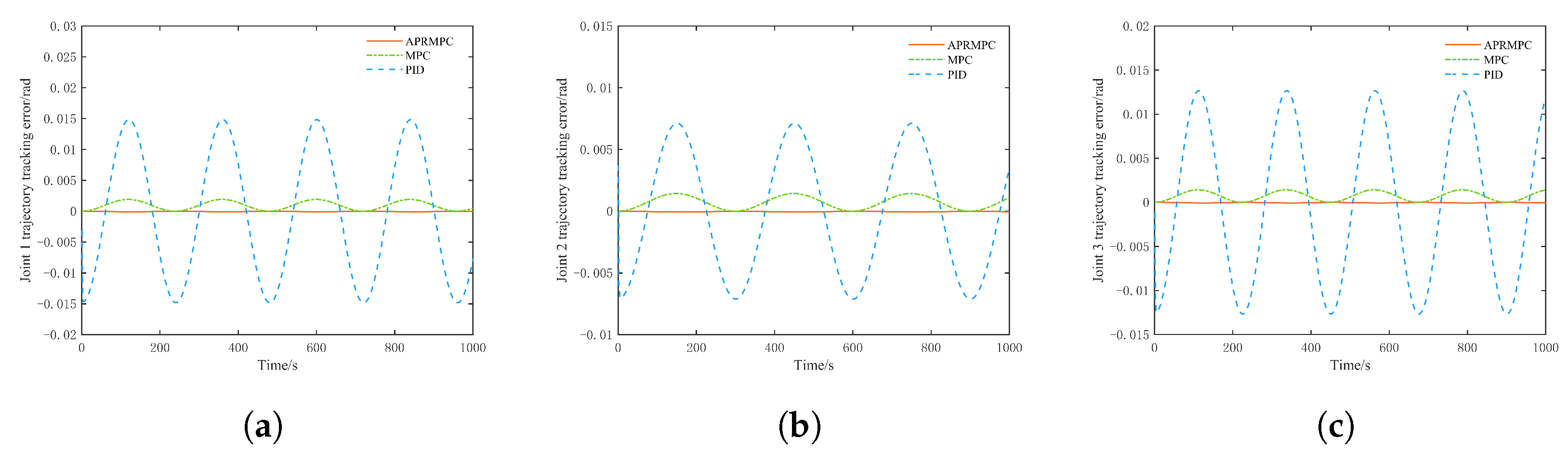

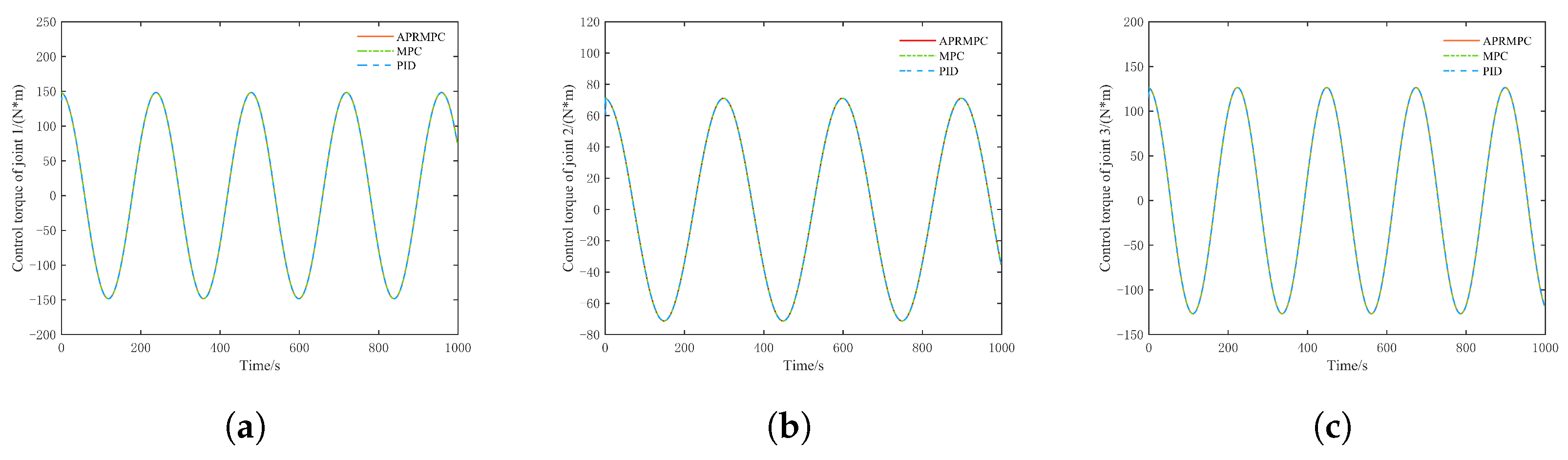

5.3. Trajectory Tracking Control Without Unknown Disturbances

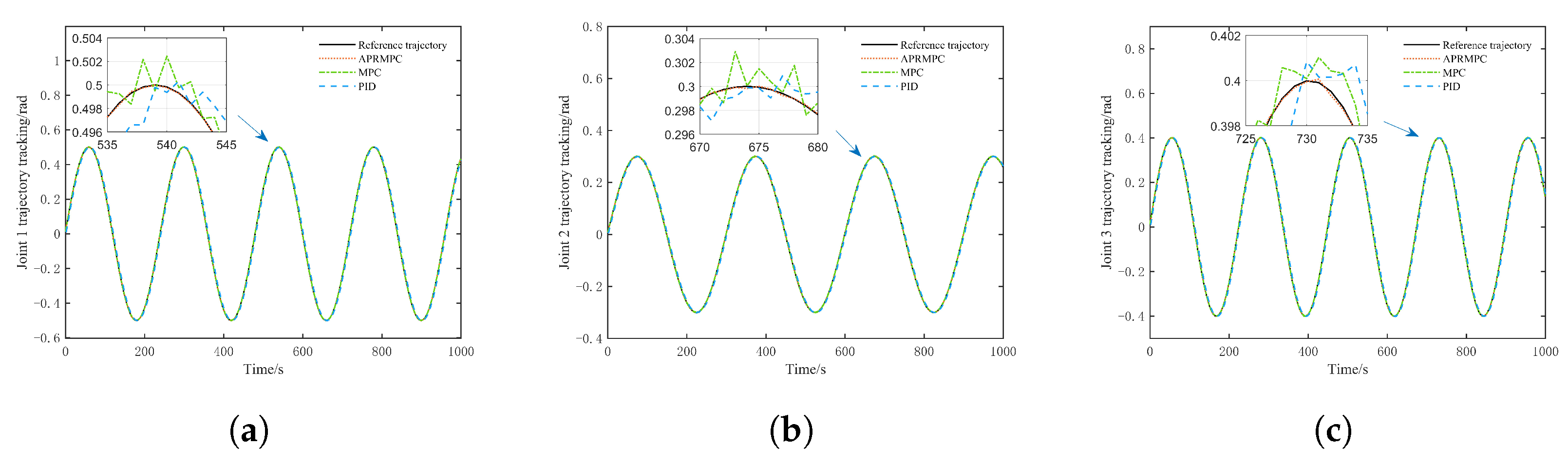

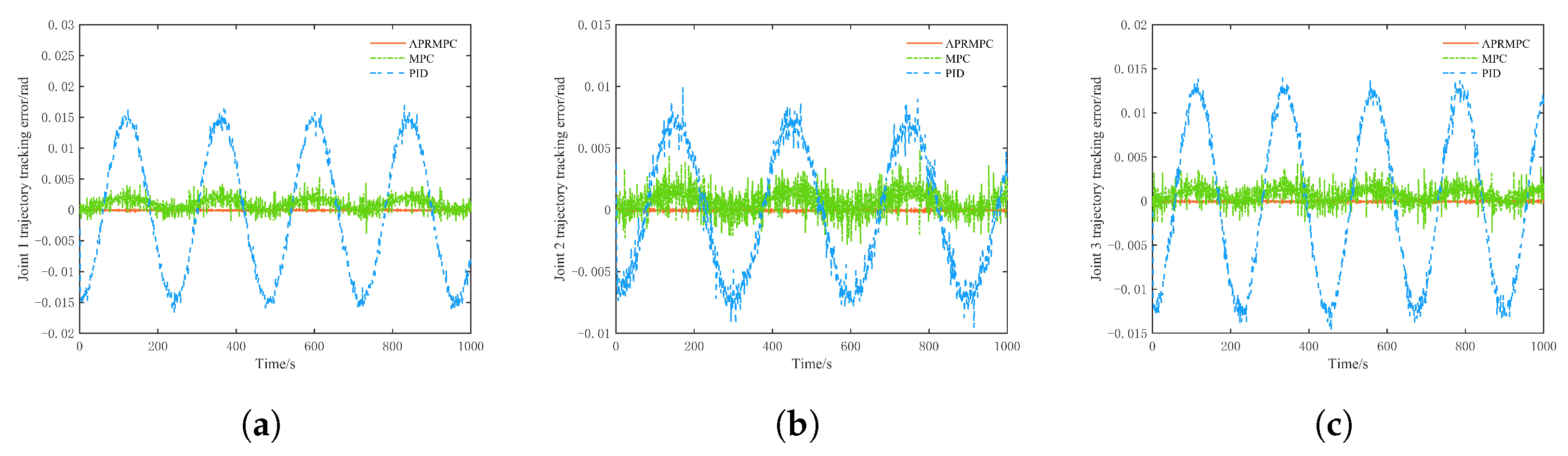

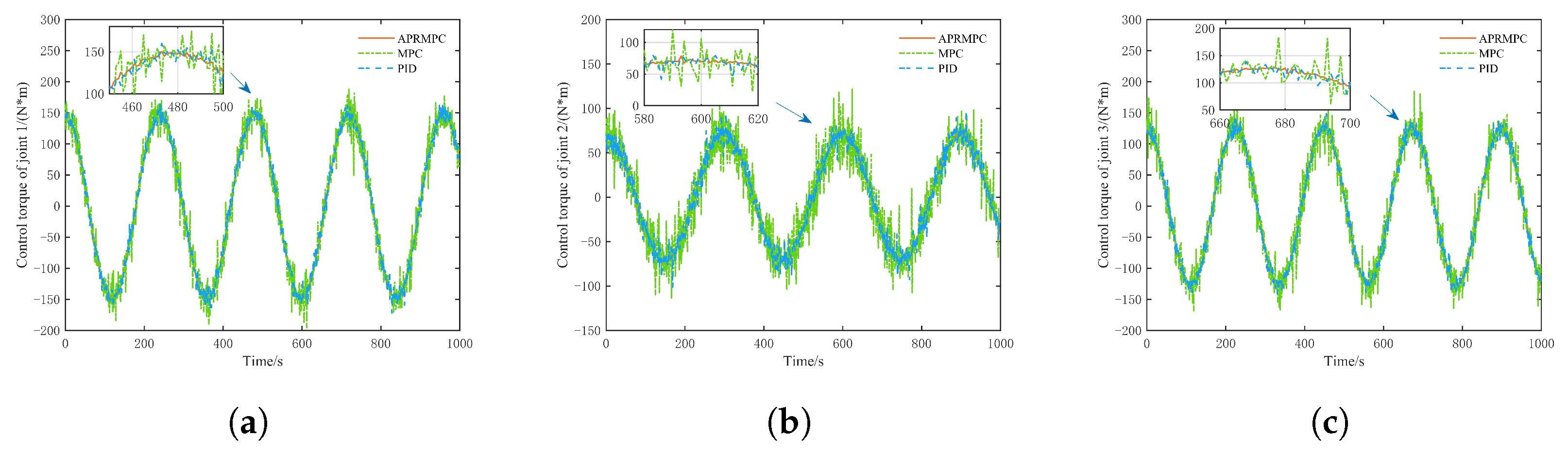

5.4. Trajectory Tracking Control Under Unknown Disturbances

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hewing, L.; Wabersich, K.P.; Menner, M. Learning based model predictive control: Toward safe learning in control. Annu. Rev. Control Robot. Auton. Syst. 2020, 3, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Cao, G.H.; Zhang, P.F.; Ma, Z.H.; Zhao, L.J.; Chen, J.N. Dynamic Analysis and Lightweight Design of 3-DOF Apple Picking Manipulator. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2023, 54, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.R.; Yang, L.J.; Li, J.; Jiao, X.L.; Zheng, H. Kinematics Analysis and Simulation of Automatically Tracking Dental Surgery Lamp. J. Syst. Simul. 2021, 33, 2864–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.M.; Lin, Y.; Xi, F. Calibration-based iterative learning control for path tracking of industrial robots. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 2921–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, J.; Koivumäki, J.; Caldwell, D.G. A survey on control of hydraulic robotic manipulators with projection to future trends. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2017, 22, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinoco, V.; Silva, M.F.; Santos, F.N. A review of advanced controller methodologies for robotic manipulators. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2025, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajwad, S.A.; Iqbal, J.; Ullah, M.I. A systematic review of current and emergent manipulator control approaches. Front. Mech. Eng. 2015, 10, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.W.; Gan, T.; Chu, T.L. Arbitrary iterative initial value suppression control based on time varying terminal sliding mode. Control Theory Technol. 2023, 40, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Loucif, F.; Kechida, S.; Sebbagh, A. Whale optimizer algorithm to tune PID controller for the trajectory tracking control of robot manipulator. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2020, 42, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Li, Q.; Fu, G. Design and control simulation analysis of tender tea bud picking manipulator. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobayen, S.; Tchier, F.; Ragoub, L. Design of an adaptive tracker for n-link rigid robotic manipulators based on super-twisting global nonlinear sliding mode control. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2017, 48, 1990–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Liu, J.X.; Wang, L.Z. Research on non-singular fast integral terminal sliding mode trajectory tracking control of six-axis manipulator. J. Syst. Simul. 2025, 37, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Zerdali, E.; Rivera, M.; Wheeler, P. A review on weighting factor design of finite control set model predictive control strategies for ac electric drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 9967–9981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. Model Predictive Control-Based Obstacle Avoidance for a 3-DOF Robotic Manipulator. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Jin, L.; Hu, B. Data-driven model predictive control for redundant manipulators with unknown model. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2024, 54, 5901–5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthusamy, P.K.; Niu, Z.; Lochan, K. Design of intelligent fuzzy neural network control for variable stiffness actuated manipulator for uncertain payload. IEEE Access 2024, 14, 160299–160314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, O. Adaptive fuzzy neural network-based finite time prescribed performance control for uncertain robotic systems with actuator saturation. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 12171–12190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Kötting, P.; Soloperto, R. A robust adaptive model predictive control framework for nonlinear uncertain systems. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2021, 31, 8725–8749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereida, K.; Brunke, L.; Schoellig, A.P. Robust adaptive model predictive control for guaranteed fast and accurate stabilization in the presence of model errors. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2021, 31, 8750–8784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Sui, Z.; Peng, H.; Xu, F.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y. Model-Free Adaptive Sliding Mode Control Scheme Based on DESO and Its Automation Application. Processes 2024, 12, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Sui, Z.; Xu, F. Posture Control of Hydraulic Flexible Second-Order Manipulators Based on Adaptive Integral Terminal Variable-Structure Predictive Method. Sensors 2025, 25, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Sui, Z.; Wei, X. Singular Perturbation Decoupling and Composite Control Scheme for Hydraulically Driven Flexible Robotic Arms. Processes 2025, 13, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, Z.; Cao, Y.; Yang, H.; Fu, Y.; Tan, C. Predictive Sliding Mode Control for High-Speed Trains via Adaptive Extended State Observer Under Input Constraints: A Model-Free Scheme. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, Z.; Yang, H.; Sui, Z.; Tan, C.; Fu, Y. Data-Driven Sliding Mode Optimal Control for Multi-Power Unit High-Speed Train: A Composite Approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2025, 10, 4279–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhong, L.; Yang, H.; Zhou, L. Distributed cooperative tracking control strategy for virtual coupling trains: An event-triggered model predictive control approach. Processes 2023, 11, 3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Peng, J.; Zhang, R.; Chen, B.; Zhou, F.; Yang, Y.; Gao, K.; Huang, Z. Adaptive model predictive control for cruise control of high-speed trains with time-varying parameters. J. Adv. Transp. 2019, 2019, 7261726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, S.; Shen, C.; Lyu, L.; Zhang, J.; Yao, B. Observer-Based Adaptive Robust Precision Motion Control of a Multi-Joint Hydraulic Manipulator. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2024, 11, 1213–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Symbols | Values/Units |

|---|---|---|

| Mass of Link 1 | ||

| Mass of Link 2 | ||

| Mass of Link 3 | ||

| Length of Link 1 | ||

| Length of Link 2 | ||

| Length of Link 3 | ||

| Gravitational Acceleration | g |

| Joint | (rad) | (rad) | (rad) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joint 1 | |||

| Joint 2 | |||

| Joint 3 |

| Control Algorithm | RMSE | IAFV |

|---|---|---|

| APRMPC | ||

| MPC | ||

| PID |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, J.; Wu, L.; Sui, Z. Trajectory Tracking Control of Hydraulic Flexible Manipulators Based on Adaptive Robust Model Predictive Control. Processes 2025, 13, 3638. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113638

Jiang J, Wu L, Sui Z. Trajectory Tracking Control of Hydraulic Flexible Manipulators Based on Adaptive Robust Model Predictive Control. Processes. 2025; 13(11):3638. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113638

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Jinwei, Li Wu, and Zhen Sui. 2025. "Trajectory Tracking Control of Hydraulic Flexible Manipulators Based on Adaptive Robust Model Predictive Control" Processes 13, no. 11: 3638. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113638

APA StyleJiang, J., Wu, L., & Sui, Z. (2025). Trajectory Tracking Control of Hydraulic Flexible Manipulators Based on Adaptive Robust Model Predictive Control. Processes, 13(11), 3638. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113638