State of Charge Estimation for Lithium-Ion Batteries: An Online Method Combining Deep Neural Network and Adaptive Kalman Filter

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A novel CNN-LSTM-AKF hybrid neural network architecture is proposed to deliver stable and accurate SOC estimations under low-temperature conditions and varying initial states, leveraging AKF to stabilize the model’s SOC outputs.

- (2)

- The model is evaluated from two perspectives: assessing SOC estimation performance across different temperatures and initial values, followed by comprehensive error analysis.

- (3)

- Through systematic comparison of three model variants—LSTM, LSTM-AKF, and CNN-LSTM-AKF—the proposed architecture demonstrates enhanced accuracy, superior adaptability, and robust performance.

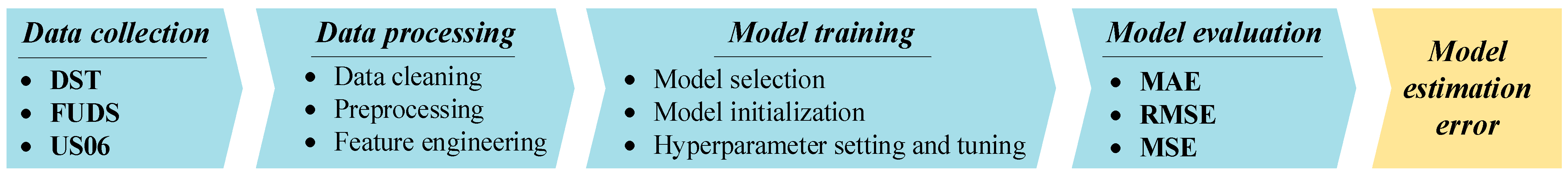

2. Battery SOC Fundamentals and Data Processing

2.1. Battery SOC Fundamentals

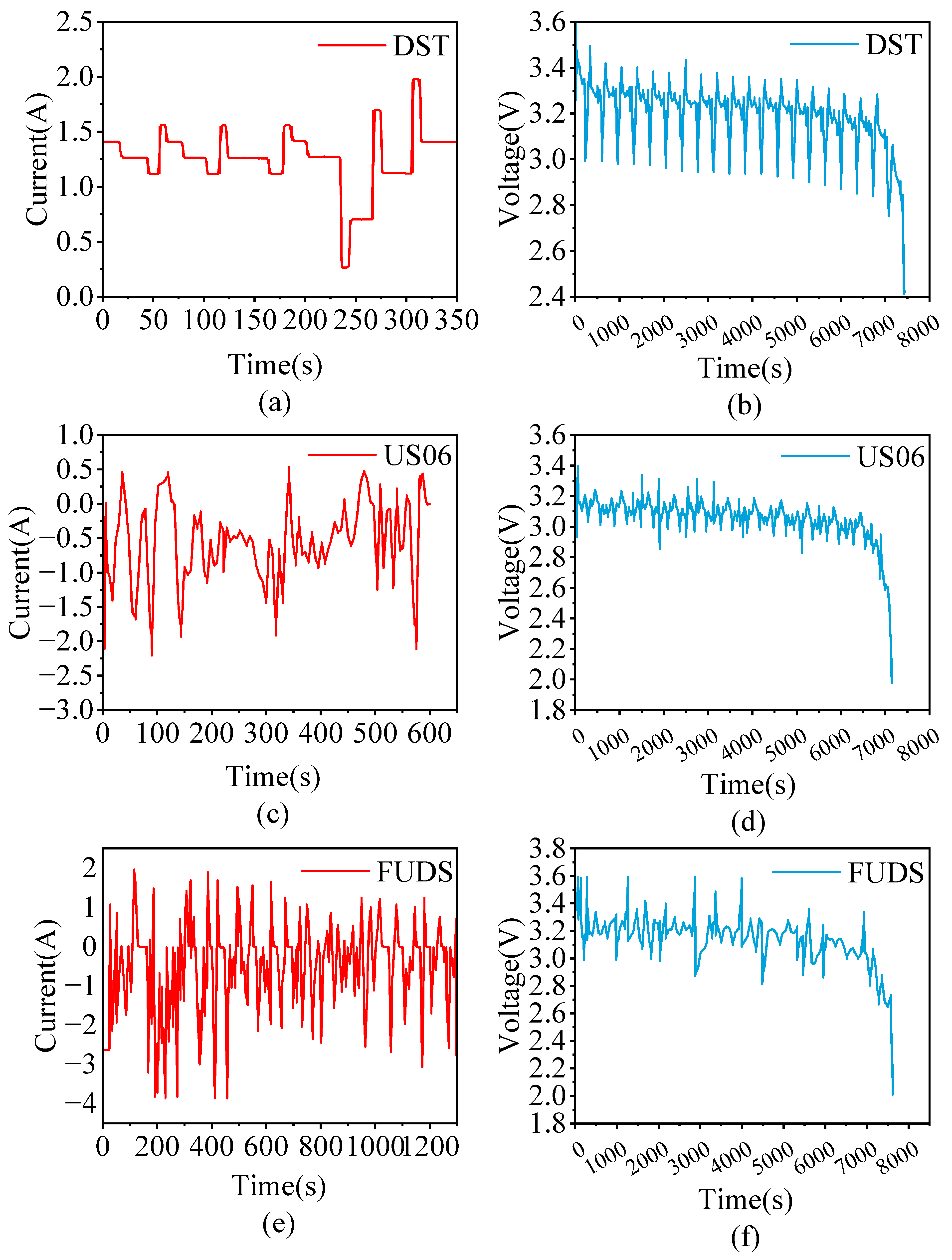

2.2. Data Processing

- (1)

- Data Acquisition: Data loading and preprocessing were executed employing libraries including Pandas and NumPy.

- (2)

- Data Cleansing: Incomplete entries were eliminated through deletion of rows/columns containing missing values or appropriate imputation techniques.

- (3)

- Preprocessing: Voltage, current, and temperature parameters were normalized using the min-max scaling method. This technique confines the data to a predetermined scale defined by max_num and min_num parameters, mathematically expressed as:

- (4)

- Feature Engineering: Feature selection was performed using the SelectKBest algorithm from the Scikit-learn framework. This method retains the k most relevant features from the feature set by evaluating the statistical relationship between each feature and the target variable through the f_regression scoring function, ultimately preserving the features with the highest statistical scores.

3. Design and Implementation of Hybrid Neural Network Models

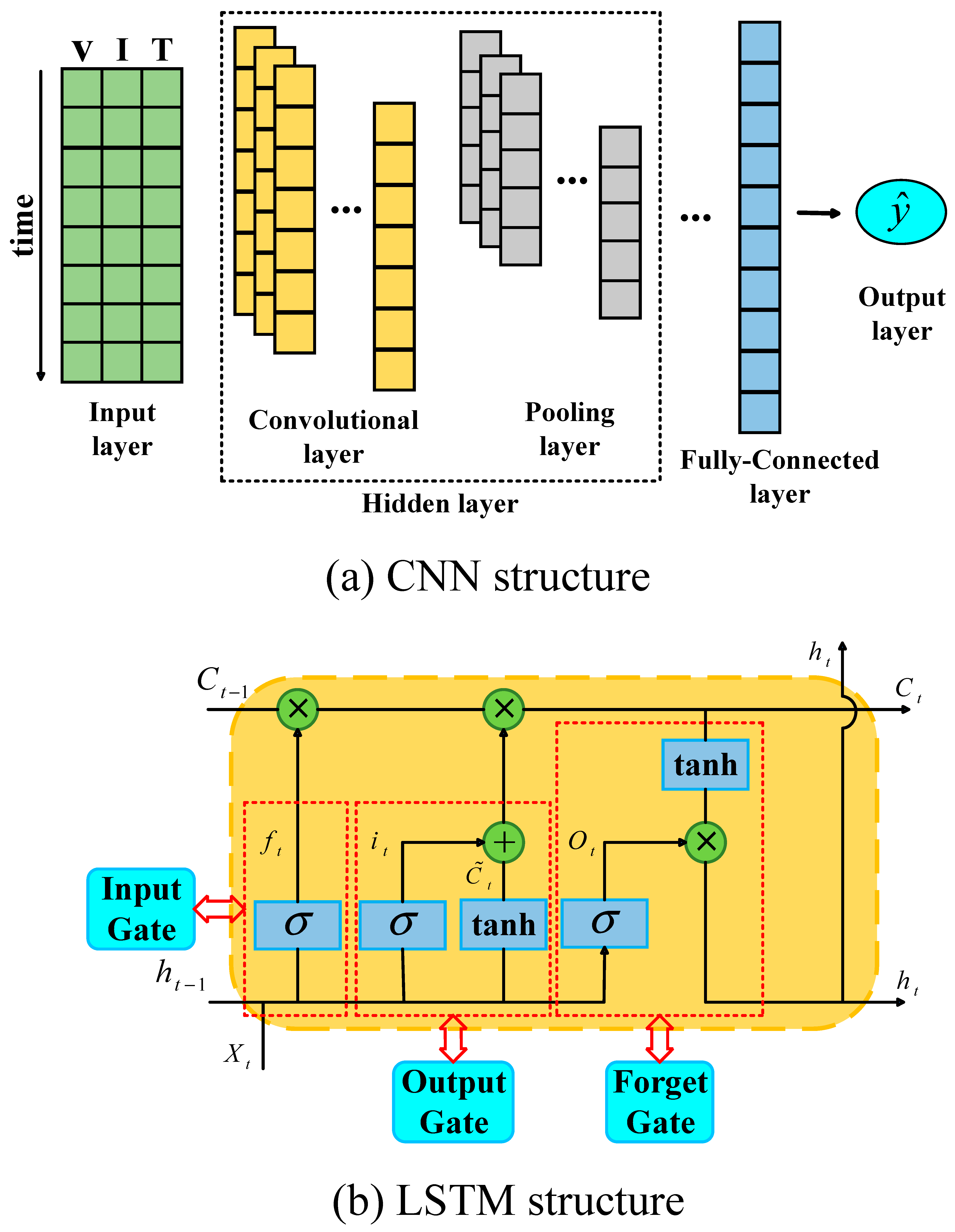

3.1. LSTM

- (1)

- Forget Gate: This mechanism modulates the retention and elimination of information within the memory cell by integrating current input with the preceding hidden state to generate its activation output . The operational principle follows the expression:where denotes the sigmoid activation function; designates the weight matrix of the forget gate; represents the bias term; and the operator denotes the concatenation operation between vectors and .

- (2)

- Input Gate: This component regulates the integration of incoming data , determining which elements should be incorporated into the memory cell. The sigmoid layer generates a gating signal that scales inputs to a continuous spectrum between 0 and 1, where unity indicates complete retention and zero represents total suppression. Through a complementary pathway, the tanh activation produces a candidate vector containing potential state modifications.where denotes the sigmoid activation function; and represent the parameter matrices of the input gate; and signify the bias vectors.

- (3)

- Output Gate: This component determines which segments of the cell state should be emitted as the final output. The operational procedure involves first processing the cell state through a tanh activation function to constrain values within the [−1,1] range, then performing element-wise multiplication with the output from the sigmoid gate to generate the ultimate output .where denotes the weight matrix of the output gate, and represents its corresponding bias vector.

- (4)

- Cell State Update: The cell state represents a fundamental innovation in LSTM architecture, maintaining persistent information flow throughout the sequential chain with minimal linear transformation. This design enables nearly lossless propagation of contextual information across extended time periods. The memory content undergoes strategic modification through coordinated gating operations, where updates are systematically applied based on outputs from both forget and input gates.where denotes the memory cell’s state from the preceding time step.

3.2. CNN

3.3. AKF

- (1)

- Initial Parameter Configuration

- (2)

- Priori Estimation

- (3)

- Posterior Estimation and State Update

- (4)

- Adaptive Noise Covariance Matching

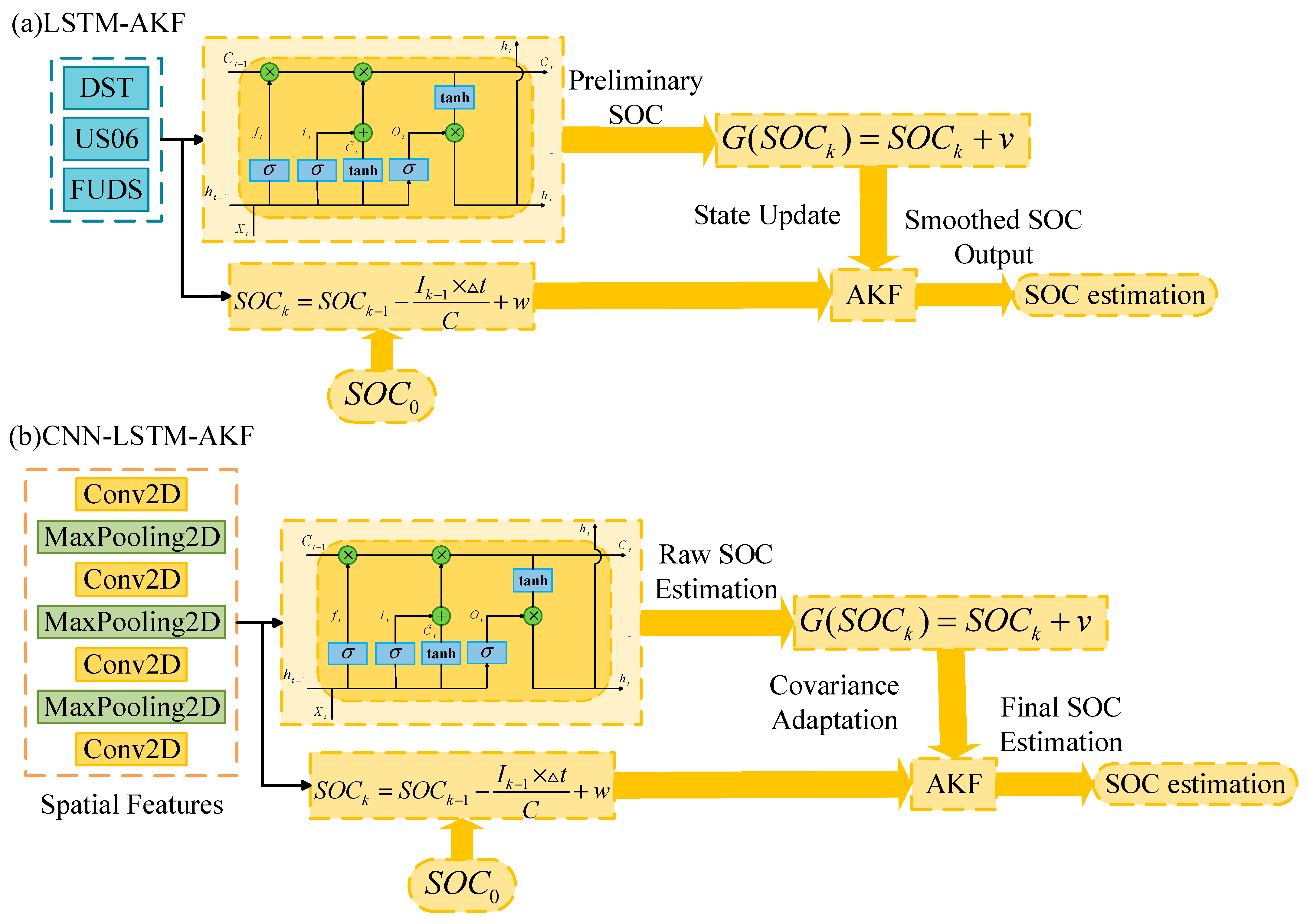

3.4. LSTM-AKF and CNN-LSTM-AKF

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Evaluation Metrics

4.2. Estimation Performance of LSTM-AKF Across Temperature Conditions

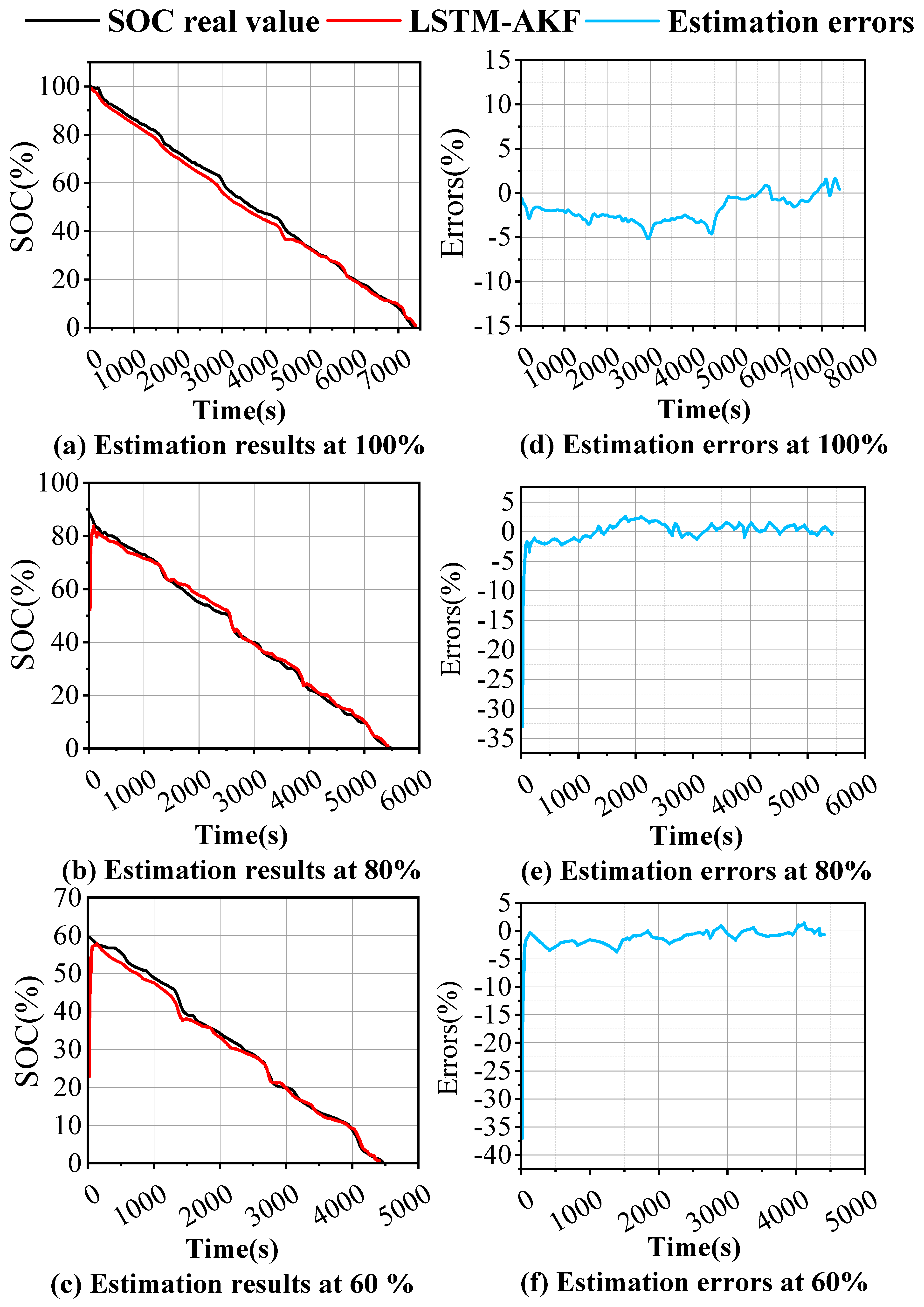

4.3. LSTM-AKF Estimation Accuracy Across Varying Initial SOC Conditions

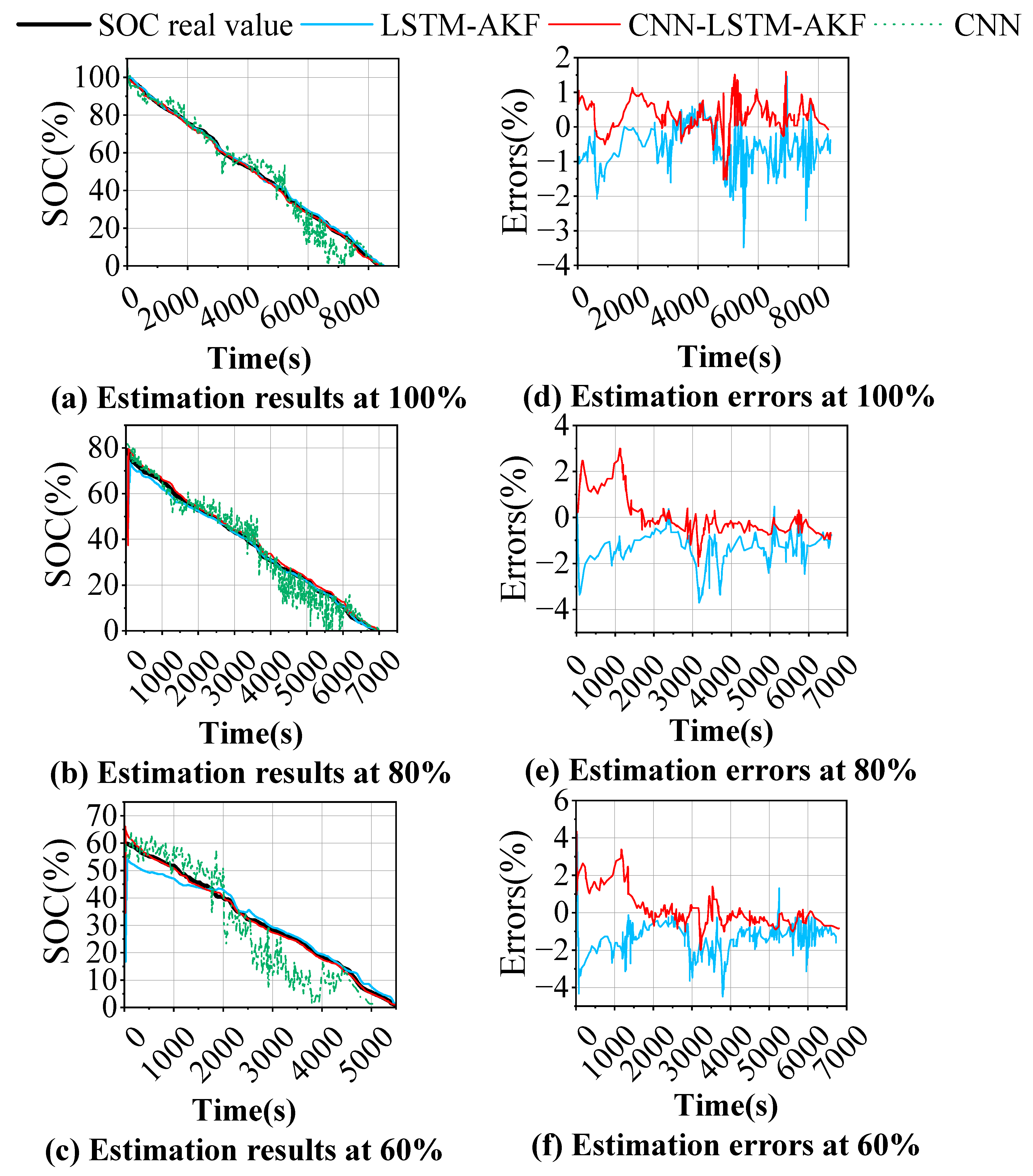

4.4. CNN-LSTM-AKF Estimation Accuracy Across Varying Initial SOC Conditions

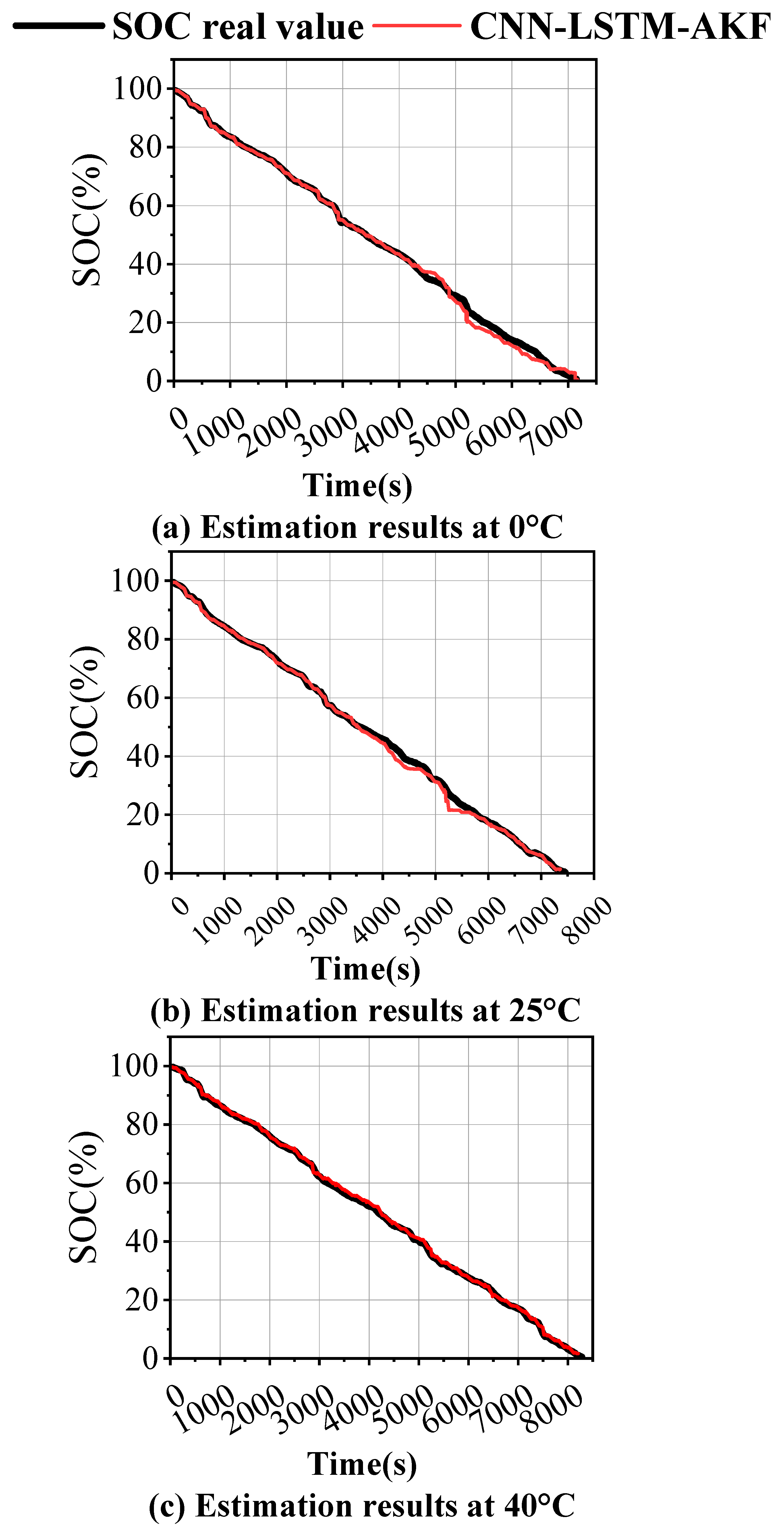

4.5. Estimation Performance of CNN-LSTM-AKF Across Temperature Conditions

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary

- (1)

- The investigation focuses on LSTM architecture enhancement through integration with Adaptive Kalman Filter theory, establishing a novel LSTM-AKF framework. This hybrid configuration enables dynamic recalibration of noise statistics through autonomous adjustment of process and measurement noise covariance matrices, effectively addressing battery data nonlinearity and parameter time-variance to achieve improved SOC estimation precision and robustness. Under FUDS testing conditions, the LSTM-AKF framework demonstrates marked error reduction across low-to-moderate temperature ranges (0 °C to 40 °C), reaching optimal performance at 30 °C with recorded RMSE and MAE values of 1.27% and 0.93%, respectively—significantly outperforming standalone LSTM results of 2.37% RMSE and 1.87% MAE. While both architectures exhibit slight performance degradation at 50 °C, the overall temperature-dependent error progression follows a characteristic pattern of initial decline followed by subsequent increase. Identical experimental protocols using DST datasets reveal consistent behavioral trends, confirming the stabilizing effect of AKF filtering on LSTM outputs while validating the hybrid model’s thermal adaptability and generalization capability across varying operational conditions.

- (2)

- To assess the resilience and generalization capability of the proposed methodology under varying initial conditions, the estimation performance of LSTM-AKF was examined across different initialization states. With full initialization (100% SOC), minimal initial deviation was observed. However, when initialized at 80% or 60% SOC levels, the framework demonstrated suboptimal performance during initial estimation phases, characterized by delayed convergence toward actual measurements and elevated aggregate error. These findings indicate that the LSTM-AKF architecture requires further refinement to effectively handle diverse initial SOC conditions.

- (3)

- To address the convergence latency of LSTM-AKF under varying initial SOC conditions while enhancing estimation precision, adaptability, and robustness, a hybrid CNN-LSTM-AKF architecture was developed. This integrated framework leverages CNN’s proficiency in spatial pattern recognition, LSTM’s temporal modeling capabilities, and AKF’s output oscillation suppression. Systematic evaluation was conducted using the US06 driving profile with initial SOC values spanning 100%, 80%, 60%, and 40%. Experimental results demonstrate accelerated initial response and superior tracking capability compared to standalone LSTM-AKF, with consistent performance excellence across all initialization scenarios. The proposed architecture maintained maximum RMSE below 1.56% and MAE under 0.77%, establishing new benchmarks for initialization robustness.

- (4)

- To systematically evaluate thermal effects on the proposed framework, the CNN-LSTM-AKF architecture was validated using FUDS operational profiles. Experimental observations revealed elevated RMSE and MAE readings at lower temperature regimes (0 °C and 10 °C). As temperatures increased through the 20 °C to 40 °C spectrum, estimation precision progressively improved with descending error metrics. Although a minor error resurgence occurred at 50 °C, the recorded deviations remained comparatively lower than those documented at 0 °C, 10 °C, 20 °C, and 30 °C benchmarks. These findings demonstrate consistent SOC estimation capability across cryogenic, ambient, and elevated thermal conditions, confirming the framework’s operational resilience across diverse thermal environments.

5.2. Future Work

- (1)

- Extreme Low-Temperature Validation: Testing the model’s performance in environments below −10 °C, which are critical for electric vehicles in frigid climates, to further challenge its low-temperature adaptability.

- (2)

- Aging and Generalization: Investigating the model’s accuracy throughout the entire battery lifecycle by incorporating state-of-health (SOH) estimation and evaluating its generalization capability to different battery chemistries and formats. Addressing these aspects will be crucial for the deployment of the model in real-world, long-term BMS applications.

5.3. Practical Implementation Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Z.; Song, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Shi, B.; He, J.; Li, J. Unveiling the electrochemical degradation behavior of 18650 lithium-ion batteries involved different humidity conditions. J. Power Sources 2025, 630, 236185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, R.; Du, X.; Zhao, K.; Qie, X.; Zhang, X. Does Low-Carbon City Construction Promote Integrated Economic, Energy, and Environmental Development? An Empirical Study Based on the Low-Carbon City Pilot Policy in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Lakshmi, G.S.; Amir, M.; Ahmad, M.; Suhaib, M. Advancement in battery health monitoring methods for electric vehicles: Battery modelling, state estimation, and internet-of-things based methods. J. Power Sources 2025, 633, 236414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzelis, A.; Linders, K.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Mouli, G.R.C. Analysis of vehicle-integrated photovoltaics and vehicle-to-grid on electric vehicle battery life. J. Power Sources 2025, 631, 236117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veza, I.; Syaifuddin, M.; Idris, M.; Herawan, S.G.; Yusuf, A.A.; Fattah, I.M.R. Electric Vehicle (EV) Review: Bibliometric Analysis of Electric Vehicle Trend, Policy, Lithium-Ion Battery, Battery Management, Charging Infrastructure, Smart Charging, and Electric Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X). Energies 2024, 17, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.; Green, J.; Bugryniec, P.; Brown, S.; Dwyer-Joyce, R. Battery age monitoring: Ultrasonic monitoring of ageing and degradation in lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2025, 631, 236174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Wen, S.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, B.; Wu, G.; Zhu, M. Multi-model deep learning-based state of charge estimation for shipboard lithium batteries with feature extraction and Spatio-temporal dependency. J. Power Sources 2025, 629, 235983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolrasol, M.G.; Ayob, A.; Lipu, M.H.; Ansari, S.; Kiong, T.S.; Saad, M.H.M.; Ustun, T.S.; Kalam, A. Advanced data-driven fault diagnosis in lithium-ion battery management systems for electric vehicles: Progress, challenges, and future perspectives. eTransportation 2024, 22, 100374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Z.; Li, J.; Yan, H.; Zhang, C.; Liu, F. Real-Time Online Estimation Technology and Implementation of State of Charge State of Uncrewed Aerial Vehicle Lithium Battery. Energies 2024, 17, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Guo, Y.; Chen, B. A Review of Lithium-Ion Battery State of Charge Estimation Methods Based on Machine Learning. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Knapp, M.; Sørensen, D.R.; Heere, M.; Darma, M.S.; Müller, M.; Mereacre, L.; Dai, H.; Senyshyn, A.; Wei, X.; et al. Investigation of capacity fade for 18650-type lithium-ion batteries cycled in different state of charge (SoC) ranges. J. Power Sources 2021, 489, 229422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, S.; Fan, Y.; Xia, L.; Qiu, J. A novel fuzzy-extended Kalman filter-ampere-hour (F-EKF-Ah) algorithm based on improved second-order PNGV model to estimate state of charge of lithium-ion batteries. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 2022, 50, 3811–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Zhu, G.; Wang, J.V.; Luo, B.; Kang, J. Comparison of robustness of different state of charge estimation algorithms. J. Power Sources 2020, 478, 228767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Shi, Q.; Shen, L.; Chen, C.; Lu, W.; Xu, C. A hybrid neural network based on KF-SA-Transformer for SOC prediction of lithium-ion battery energy storage systems. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1424204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Wang, Z.; Hou, E.; Liu, G.; Cai, Y. Online Estimation of Open Circuit Voltage Based on Extended Kalman Filter with Self-Evaluation Criterion. Energies 2022, 15, 4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Vera, E.D.; Valdez-Resendiz, J.E.; Escobar, G.; Guillen, D.; Rosas-Caro, J.C.; Sosa, J.M. Data-Driven Modeling and Open-Circuit Voltage Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Xu, L.; Deng, Z.; Xie, Y.; Li, J.; Hu, X. A novel nonlinearity-aware adaptive observer for estimating surface concentration and state of charge of lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2024, 602, 234373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fu, R. Stability Analysis of EKF-Based SOC Observer for Lithium-Ion Battery. Energies 2023, 16, 5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goshtasbi, A.; Zhao, R.; Wang, R.; Han, S.; Ma, W.; Neubauer, J. Enhanced equivalent circuit model for high current discharge of lithium-ion batteries with application to electric vertical takeoff and landing aircraft. J. Power Sources 2024, 620, 235188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.; Huang, Y.; Liu, S.; Yu, Q.; Shen, W.; Xiong, R. A novel lithium-ion battery state of charge estimation method based on the fusion of neural network and equivalent circuit models. Appl. Energy 2023, 348, 121578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Tian, W.; Yue, J.; Su, F. Lithium-ion battery heterogeneous electrochemical-thermal-mechanical multiphysics coupling model and characterization of microscopic properties. J. Power Sources 2025, 629, 235970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Peng, Q.; Meng, J.; Liu, T.; Peng, J.; Teodorescu, R. A physics-informed neural network approach to parameter estimation of lithium-ion battery electrochemical model. J. Power Sources 2024, 621, 235271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, T.H.; Singh, S. Advanced integration of bidirectional long short-term memory neural networks and innovative extended Kalman filter for state of charge estimation of lithium-ion battery. J. Power Sources 2025, 628, 235893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ahmed, R.; Habibi, S. State-of-health estimation for lithium-ion batteries based on electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurements combined with unscented Kalman filter. J. Power Sources 2025, 625, 235450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Fan, X. Online parameters identification and state of charge estimation for lithium-ion batteries based on improved central difference particle filter. J. Energy Storage 2023, 70, 107987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qu, Z.; Xu, T.; Wang, Y.; Fan, X.; Jiang, H.; Yuan, C.; Chen, L. SOC estimation based on the gas-liquid dynamics model using particle filter algorithm. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 22913–22925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Cui, N.; Cui, W.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, C. Receding horizon control based energy management strategy for PHEB using GRU deep learning predictive model. eTransportation 2022, 13, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesidhar, D.V.S.R.; Chandrashekhar, B.; Green, R.C., II. A review on data-driven SOC estimation with Li-Ion batteries: Implementation methods & future aspirations. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, T.; Belnarsch, A.; Bilfinger, P.; Ratzke, W.; Lienkamp, M. Collaborative training of deep neural networks for the lithium-ion battery aging prediction with federated learning. eTransportation 2023, 18, 100294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L. A generic fusion framework integrating deep learning and Kalman filter for state of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries: Analysis and comparison. J. Power Sources 2024, 623, 235493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, C.; Lu, C.; Xuan, D. State-of-charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries using convolutional neural network with self-attention mechanism. J. Electrochem. Energy Convers. Storage 2022, 20, 031010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Jiang, B.; Wei, X.; Dai, H. A Systematic and Comparative Study of Distinct Recurrent Neural Networks for Lithium-Ion Battery State-of-Charge Estimation in Electric Vehicles. Energies 2023, 16, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hou, J.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, Y. Study of SOC Estimation by the Ampere-Hour Integral Method with Capacity Correction Based on LSTM. Batteries 2022, 8, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Hu, C.; Cheng, F. State of Charge and State of Energy Estimation for Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on a Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network. J. Energy Storage 2021, 37, 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, C.; He, H.; Yang, S. Stacked bidirectional long short-term memory networks for state-of-charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries. Energy 2020, 191, 116538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Liang, F.; Yang, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W.; Li, K.; Yang, J. Multi- forword-step state of charge prediction for real-world electric vehicles battery systems using a novel LSTM-GRU hybrid neural network. eTransportation 2024, 20, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Liao, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, L. State-of-charge estimation of lithium-ion battery: Joint long short-term memory network and adaptive extended Kalman filter online estimation algorithm. J. Power Sources 2024, 604, 234451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ren, S.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D. A novel fault prediction method based on convolutional neural network and long short-term memory with correlation coefficient for lithium-ion battery. J. Energy Storage 2023, 62, 106811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Yu, Q.; Liu, S.; Zhou, G.; Shen, W. State of charge estimation for lithium-ion batteries based on cross-domain transfer learning with feedback mechanism. J. Energy Storage 2023, 70, 108037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Peng, W.; Yang, F. An LSTM-SA model for SOC estimation of lithium-ion batteries under various temperatures and aging levels. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Wang, J.; Yan, D.; Li, Y.; Tang, X. Novel state of charge estimation method of containerized Lithium–Ion battery energy storage system based on deep learning. J. Power Sources 2024, 624, 235609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, P.; Sundaresan, S.; Kumar, P.; Pattipati, K.R.; Balasingam, B. Open-Circuit Voltage Models for Battery Management Systems: A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 6803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CALCE. Lithium-Ion Battery Experimental Data [EB/OL]. Battery Data|Center for Advanced Life Cycle Engineering. Available online: https://calce.umd.edu/battery-data (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Yuan, T.; Gao, F.; Bai, J.; Sun, H. A lithium-ion battery state of health estimation method utilizing convolutional neural networks and bidirectional long short-term memory with attention mechanisms for collaborative defense against false data injection cyber-attacks. J. Power Sources 2025, 631, 236193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Nominal Capacity | 3.0 Ah |

| Nominal Voltage | 3.6 V/3.7 V |

| Charge/Discharge Cut-off Voltage | 4.2 V/2.5 V |

| Standard Charging Current | 1.5 A |

| Maximum Continuous Discharge Current | 20 A |

| Charge Termination Current | 50 mA |

| Energy Density | 240 Wh/Kg |

| Discharge Rate | 1 C |

| Ambient Temperature Range | 15 °C to 30 °C |

| Dimensions | cylindrical cell, 18 mm diameter × 65 mm length |

| Weight | about 47 g |

| Applications | Electronic devices, electric vehicles, energy storage systems |

| Test Environment | 8 cu ft thermal chamber, 75 A/5 V universal battery test channels |

| Test Accuracy | Voltage/current measurement accuracy: 0.1% of full scale |

| Partition | Temperature | Dateset |

|---|---|---|

| Training Set | −10 °C, 0 °C, 10 °C, 20 °C, 30 °C and 40 °C | DST, FUDS |

| Test Set 1 | −10 °C | US06 |

| Test Set 2 | 0 °C | US06 |

| Test Set 3 | 10 °C | US06 |

| Test Set 4 | 25 °C | US06 |

| Test Set 5 | 40 °C | US06 |

| Validation Set 1 | 25 °C | FUDS |

| Validation Set 2 | 25 °C | DST |

| Hyperparameter | Parameter Setting |

|---|---|

| Batch size | 128 |

| Iterations | 300 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Dropout Rate | Dropout = 0.1 |

| Learning Rate | 0.001 |

| LSTM layer | 1 layer |

| Number of neurons in LSTM layer | 256 |

| Four-layer convolution | The convolution kernels are in order 16, 32, 64 and 128 |

| Convolution kernel size | 3 × 3 |

| Pooling layer size | 2 × 2 |

| Dataset | Temperature | LSTM-AKF | LSTM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FUDS | RMSE (%) | MAE (%) | RMSE (%) | MAE (%) | |

| 0 °C | 7.08 | 5.55 | 8.83 | 6.70 | |

| 10 °C | 5.13 | 4.32 | 6.61 | 5.24 | |

| 20 °C | 2.07 | 1.55 | 4.54 | 2.46 | |

| 25 °C | 1.30 | 0.96 | 2.70 | 1.95 | |

| 30 °C | 1.27 | 0.93 | 2.37 | 1.87 | |

| 40 °C | 1.35 | 0.92 | 1.67 | 1.16 | |

| 50 °C | 2.27 | 1.81 | 2.21 | 2.43 | |

| Dataset | Temperature | LSTM-AKF | LSTM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DST | RMSE (%) | MAE (%) | RMSE (%) | MAE (%) | |

| 0 °C | 8.83 | 6.70 | 10.76 | 9.56 | |

| 10 °C | 6.61 | 5.24 | 8.94 | 7.82 | |

| 20 °C | 3.74 | 2.46 | 6.25 | 4.93 | |

| 25 °C | 2.70 | 1.95 | 5.20 | 4.12 | |

| 30 °C | 1.98 | 1.83 | 3.56 | 3.17 | |

| 40 °C | 2.07 | 1.66 | 2.63 | 2.44 | |

| 50 °C | 2.21 | 2.43 | 3.79 | 3.21 | |

| SOC Initial Value (%) | RMSE(%) | MAE(%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | LSTM-AKF | CNN-LSTM-AKF | CNN | LSTM-AKF | CNN-LSTM-AKF | |

| 100 | 5.26 | 1.00 | 0.59 | 4.11 | 0.82 | 0.45 |

| 80 | 5.71 | 1.63 | 0.93 | 4.98 | 1.41 | 0.65 |

| 60 | 6.36 | 1.78 | 1.01 | 5.96 | 1.15 | 0.68 |

| 40 | 7.49 | 2.06 | 1.56 | 6.15 | 1.56 | 0.77 |

| Temperature (℃) | RMSE (%) | MAE (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.45 | 1.18 |

| 10 | 1.51 | 1.12 |

| 20 | 1.32 | 0.98 |

| 25 | 0.97 | 0.56 |

| 30 | 0.85 | 0.53 |

| 40 | 0.69 | 0.51 |

| 50 | 0.81 | 0.71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, H.; Zhao, F.; Guo, Y. State of Charge Estimation for Lithium-Ion Batteries: An Online Method Combining Deep Neural Network and Adaptive Kalman Filter. Processes 2025, 13, 3559. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113559

Xu H, Zhao F, Guo Y. State of Charge Estimation for Lithium-Ion Batteries: An Online Method Combining Deep Neural Network and Adaptive Kalman Filter. Processes. 2025; 13(11):3559. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113559

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Hongwen, Feng Zhao, and Yun Guo. 2025. "State of Charge Estimation for Lithium-Ion Batteries: An Online Method Combining Deep Neural Network and Adaptive Kalman Filter" Processes 13, no. 11: 3559. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113559

APA StyleXu, H., Zhao, F., & Guo, Y. (2025). State of Charge Estimation for Lithium-Ion Batteries: An Online Method Combining Deep Neural Network and Adaptive Kalman Filter. Processes, 13(11), 3559. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113559