Experimental Study on Proppant Transport and Distribution in Asymmetric Branched Fractures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Apparatus

2.2. Experimental Materials

2.3. Experimental Scheme

2.4. Dimensionless Parameters

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Proppant Distribution Evolution

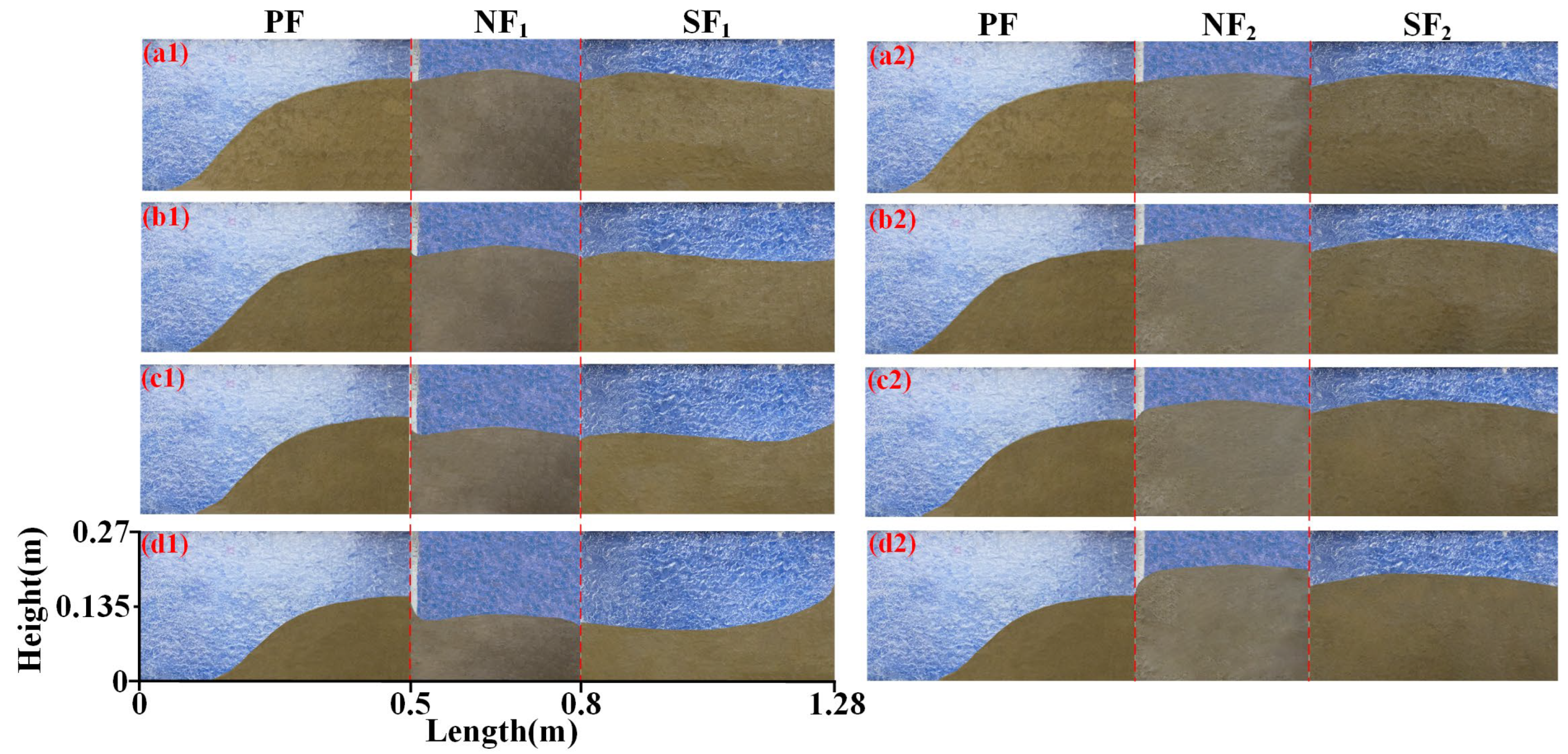

3.2. Proppant Distribution with NF1 at the Bottom

3.3. Proppant Distribution with NF1 at the Top

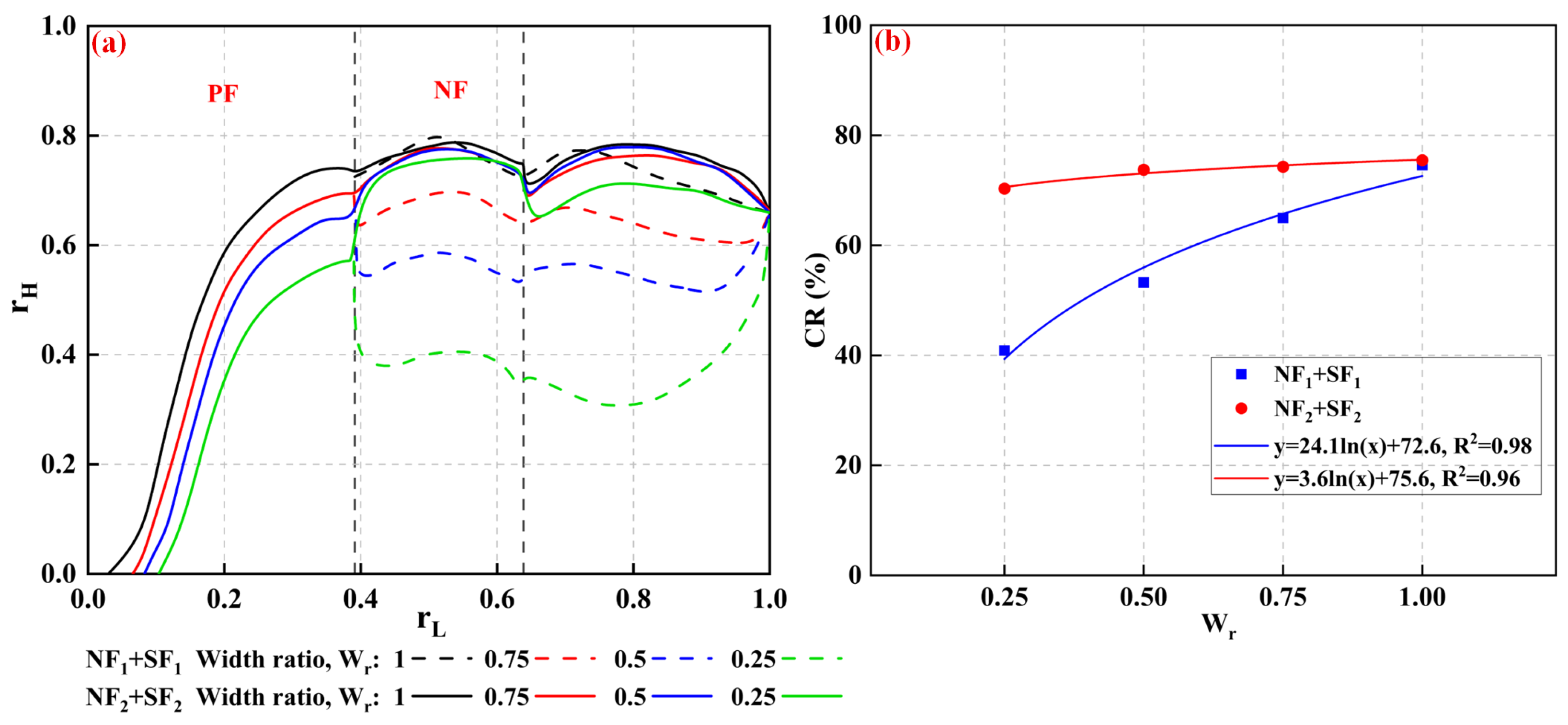

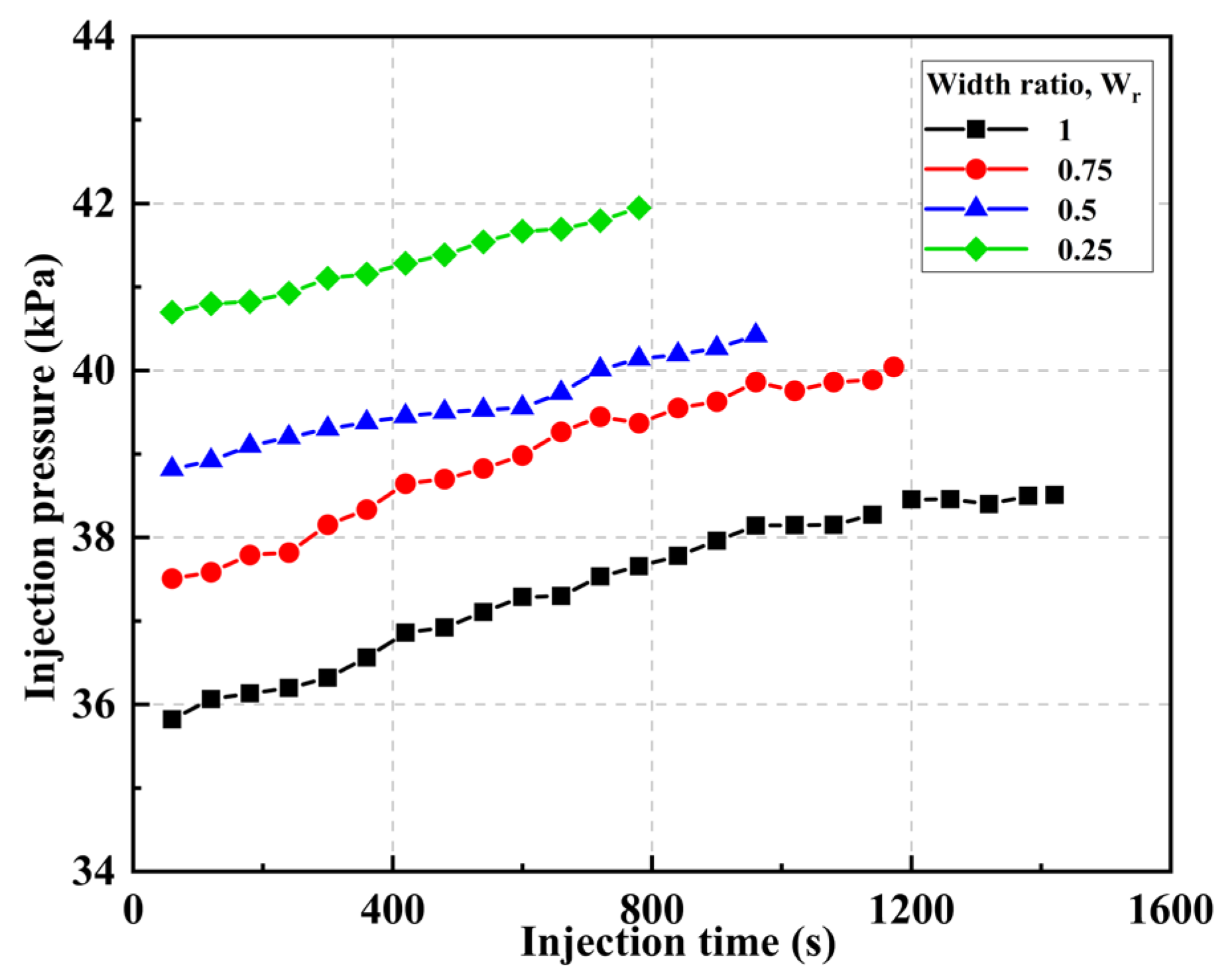

3.4. Effect of Branch Width

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

- At a height ratio of 0.25, the branch is located in the lower section, and sand bridging is likely to occur once the sand bed in the primary fracture reaches a certain height. In naturally fractured reservoirs, it is recommended to increase the proportion of small-sized proppants (e.g., 70/140 or 200 mesh) to ensure smooth transport through narrow fractures and minimize the risk of premature bridging.

- When the branch is located at the upper section, proppants hardly settle to form a bed, leading to closure of the natural fracture. In the later stage of fracturing, lowering the injection rate could enhance particle accumulation in the natural fracture.

- A reduction in fracture width significantly increases the injection pressure while decreasing the sand bed area. In naturally fractured reservoirs, this leads to higher operational pressures during fracturing. Increasing fluid viscosity or reducing the injection rate decreases injection pressure and particle transport.

- The bed morphology within asymmetric branch fractures is more irregular than in regular slots, leading to a lower sand bed coverage ratio. The more complex slurry flow in asymmetric fractures can transport particles deeper into the fracture, further reducing coverage. In the later stage of fracturing, lowering the injection rate or using larger-sized proppant can enhance particle settling, improving overall coverage.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A | fracture area, m2 |

| As | sand bed area, m2 |

| CR | coverage ratio, % |

| H | fracture height, m |

| Hr | height ratio |

| Hs | sand bed height, m |

| JRC | Joint Roughness Coefficient |

| L | fracture length, m |

| Ls | sand bed length, m |

| NF | natural fractures |

| NF1 | left branch of natural fractures |

| NF2 | right branch of natural fractures |

| PF | primary fracture |

| rH | normalized height |

| rL | normalized length |

| SF | secondary fractures |

| SF1 | left branch of secondary fractures |

| SF2 | right branch of secondary fractures |

| Wr | width ratio |

References

- Miskimins, J. Hydraulic Fracturing: Fundamentals and Advancements; Society of Petroleum Engineers: The Woodlands, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Chang, Z.; Fu, W.; Muhadasi, Y.; Chen, M. Fracture Initiation and Propagation in a Deep Shale Gas Reservoir Subject to an Alternating-Fluid-Injection Hydraulic-Fracturing Treatment. SPE J. 2019, 24, 1839–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahorich, B.; Olson, J.E.; Holder, J. Examining the Effect of Cemented Natural Fractures on Hydraulic Fracture Propagation in Hydrostone Block Experiments. In SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition; Society of Petroleum Engineers: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2012; p. 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Tang, S.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Xu, J.; Qi, N.; Rui, Z. Physical Simulation of Hydraulic Fracturing of Large-Sized Tight Sandstone Outcrops. SPE J. 2021, 26, 372–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Qu, Z.; Guo, T.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y. Experimental Study on the Transport Law of Different Fracturing Granular Materials in Fracture. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 10886–10898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qu, H.; Lu, Z.; Fei, Y. Experimental investigation of particle transport behaviors and distribution characteristics in a dual-branch fracture with rough surfaces. Powder Technol. 2025, 452, 120602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Gou, H.; Zhang, T.; Zeng, X.; Li, M.; Tang, T. Experiment on proppant transport in near-well area of hydraulic fractures based on PIV/PTV. Powder Technol. 2022, 410, 117833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Wang, R.; Ao, X.; Xue, L.; Liu, Z.; Lin, H. The Investigation of Proppant Particle-Fluid Flow in the Vertical Fracture with a Contracted Aperture. SPE J. 2022, 27, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Mohanty, K.K. Proppant transport study in fractures with intersections. Fuel 2016, 181, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isah, A.; Hiba, M.; Al-Azani, K.; Aljawad, M.S.; Mahmoud, M. A comprehensive review of proppant transport in fractured reservoirs: Experimental, numerical, and field aspects. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 88, 103832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Guo, T.; Qu, Z.; Chen, M.; Dai, C.; Liu, X. Experimental Study on Proppant Transport within Complex Fractures. SPE J. 2022, 27, 2960–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahai, R.; Moghanloo, R.G. Proppant transport in complex fracture networks—A review. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2019, 182, 106199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, L.; Perkins, T.; Wyant, R. The mechanics of sand movement in fracturing. J. Pet. Technol. 1959, 11, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patankar, N.A.; Joseph, D.; Wang, J.; Barree, R.; Conway, M.; Asadi, M. Power law correlations for sediment transport in pressure driven channel flows. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2002, 28, 1269–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodworth, T.R.; Miskimins, J.L. Extrapolation of Laboratory Proppant Placement Behavior to the Field in Slickwater Fracturing Applications. In SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference; Society of Petroleum Engineers: College Station, TX, USA, 2007; p. 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, M.A.; Miskimins, J.L. Slickwater Proppant Transport in Hydraulic Fractures: New Experimental Findings and Scalable Correlation. SPE Prod. Oper. 2018, 33, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Babadagli, T.; Li, H.A.; Develi, K.; Wei, G. Effect of injection parameters on proppant transport in rough vertical fractures: An experimental analysis on visual models. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2019, 180, 380–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahai, R.; Miskimins, J.L.; Olson, K.E. Laboratory Results of Proppant Transport in Complex Fracture Systems. In SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference; Society of Petroleum Engineers: The Woodlands, TX, USA, 2014; p. 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Wang, S.; Duan, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Jin, X. Experimental investigation of proppant settling in complex hydraulic-natural fracture system in shale reservoirs. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 33, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Zeng, Z.; Guo, R. Experimental study of fluid-particle flow characteristics in a rough fracture. Energy 2023, 285, 129380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, R. Estimating joint roughness coefficients. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1979, 16, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Liu, Y.; Lin, H.; Tang, S.; Wang, R.; Xue, L.; Hu, Y. 3D CFD-DEM simulation and experiment on proppant particle-fluid flow in a vertical, nonplanar fracture with bends. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2022, 146, 103873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, T.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Mao, S.; Wu, K. Experimental Study of Proppant Transport in Complex Fractures with Horizontal Bedding Planes for Slickwater Fracturing. SPE Prod. Oper. 2020, Preprint, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, K.G. Application of Fracture Design Based on Pressure Analysis. SPE Prod. Eng. 1988, 3, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yao, J.; Gong, L.; Sun, H.; Liu, W. Numerical simulations of proppant deposition and transport characteristics in hydraulic fractures and fracture networks. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2019, 183, 106401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Length (m) | Height (m) | Width (mm) | Inner Wall | Intersection Angle (°) | Liquid | Proppant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sahai, Miskimins and Olson [18] | P = 1.2 S = 0.3 | 0.6 | 5.4 | Smooth | 90 | Water | Sand |

| Tong and Mohanty [9] | P = 0.38 S = 0.19 | 0.076 | 2.0 | Smooth | 30, 60, 90 | Water | Sand |

| Wen, Wang and Duan [19] | P = 0.6 S = 0.3 T = 0.6 | 0.4 | 10 | Smooth | 90 | Water Guar gum | Ceramsite |

| Alotaibi and Miskimins [16] | P = 1.2 S = 0.3 | 0.6 | 5.4 | Rough | 90 | Water | Sand |

| Case | Fracture Height (mm) | Panel Position | Fracture Weight (mm) | Height Ratio Hr | Width Ratio Wr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 270 | / | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | NF1 = 202.5 | Bottom | 4 | 0.75 | 1 |

| 3 | NF1 = 135 | Bottom | 4 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 4 | NF1 = 67.5 | Bottom | 4 | 0.25 | 1 |

| 5 | NF1 = 202.5 | Top | 4 | 0.75 | 1 |

| 6 | NF1 = 135 | Top | 4 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 7 | NF1 = 67.5 | Top | 4 | 0.25 | 1 |

| 8 | 270 | / | NF1 = 3 | 1 | 0.75 |

| 9 | 270 | / | NF1 = 2 | 1 | 0.5 |

| 10 | 270 | / | NF1 = 1 | 1 | 0.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, Z.; Qu, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, P.; You, K. Experimental Study on Proppant Transport and Distribution in Asymmetric Branched Fractures. Processes 2025, 13, 3482. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113482

Lu Z, Qu H, Liu Y, Liu Z, Liu S, Zhang P, You K. Experimental Study on Proppant Transport and Distribution in Asymmetric Branched Fractures. Processes. 2025; 13(11):3482. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113482

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Zhitian, Hai Qu, Ying Liu, Zhonghua Liu, Su Liu, Pengcheng Zhang, and Kaige You. 2025. "Experimental Study on Proppant Transport and Distribution in Asymmetric Branched Fractures" Processes 13, no. 11: 3482. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113482

APA StyleLu, Z., Qu, H., Liu, Y., Liu, Z., Liu, S., Zhang, P., & You, K. (2025). Experimental Study on Proppant Transport and Distribution in Asymmetric Branched Fractures. Processes, 13(11), 3482. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113482