1. Introduction

Low-permeability reservoirs represent a critical frontier in global petroleum resource development, with their efficient exploitation holding strategic importance for energy security [

1,

2]. Characterized by low permeability (typically below 50 mD) and fine pore throats (mostly under 1 μm), these reservoirs exhibit significant threshold pressure gradients, pronounced non-Darcy flow behavior, and strong heterogeneity. These inherent properties pose major challenges, including low displacement efficiency, suboptimal recovery rates, and a rapid water cut rise following water breakthrough during water flooding operations [

3].

Significant research has been conducted on oil–water relative permeability curves and flow mechanisms in low-permeability reservoirs [

4,

5,

6]. These formations are characterized by high irreducible water saturation, a narrow two-phase flow region, rapid decline in oil-phase permeability, and early water breakthrough, with increased permeability generally improving development outcomes [

7,

8]. For cores with comparably low permeability, the coupling effect of permeability and pressure gradient reduces both irreducible water and residual oil saturation, expands the two-phase flow region, and enhances displacement efficiency phenomena primarily attributed to capillary and boundary layer effects [

9].

The “triple porosity system” in such reservoirs leads to a distinct residual oil distribution: large pores are water-dominated, medium pores are oil-enriched, and micropores contain irreducible oil. Proposed strategies include injecting high-salinity water to alter wettability and employing unsteady water injections to leverage imbibition. Comparative studies further reveal that light oil reservoirs exhibit high oil-phase permeability, very low water-phase permeability, and a limited co-flow zone, whereas low-permeability reservoirs display dual-high characteristics high irreducible water saturation and high residual oil saturation along with rapidly declining oil-phase permeability and a narrow two-phase flow region [

10]. Clarifying oil–water two-phase flow mechanisms is essential for improving recovery efficiency, making accurate characterization of flow behavior and optimization of water flooding strategies central scientific challenges in developing low-permeability reservoirs.

Based on previous research and the actual geological and fluid conditions of a typical low-permeability block in the Oilfield, this study systematically investigates the characteristics of oil–water relative permeability curves and non-Darcy flow behaviors through experimental and theoretical approaches. The research comprises three main components: (1) Determining the quasi-threshold pressure gradient the minimum normalized pressure gradient required to initiate fluid flow in low-permeability reservoirs under varying physical properties and water saturation conditions, and developing a mathematical model that dynamically characterizes this gradient by incorporating the corrected permeability and water saturation; (2) Establishing a novel relative permeability computation model for unsteady-state water flooding based on non-Darcy flow theory, which dynamically integrates the quasi-threshold pressure gradient; (3) Comparing and validating the proposed model against the traditional Johnson-Bossler-Naumann (JBN) method, which calculates relative permeability curves from unsteady-state experimental data and serves as a fundamental input for numerical simulation, productivity forecasting, and development planning. The findings are expected to provide a more reliable theoretical basis and practical guidance for optimizing water flooding strategies in low-permeability reservoirs, thereby contributing to improved recovery of oil and gas resources.

2. Methods and Procedures

2.1. Experimental Materials

For this study, native core samples were obtained from a low-permeability reservoir block exhibiting typical characteristics of such formations, with permeabilities ranging from 10 to 50 mD and burial depths between 2500 and 3000 m. Reservoirs within this interval display strong heterogeneity and sensitivity, along with a high initial water saturation of approximately 40%, consistent with common features of low-permeability systems. To ensure mineralogical and physical consistency, all cores were selected from the same sedimentary unit. Four representative native core samples were used in the experiments, which were conducted at 50 °C. The experimental oil was prepared by blending crude oil with neutral kerosene to achieve a viscosity of 6.44 mPa·s, while the experimental water was a synthetic formation brine formulated with NaCl and CaCl2 at a total salinity of 50,000 mg/L.

2.2. Experimental Methodology

The experiments were performed following the Chinese National Standard *GB/T 28912-2012* [

11] for measuring oil–water relative permeability via the unsteady-state method. Under simulated reservoir temperature, pressure, and salinity conditions, water flooding tests were conducted on core samples. After establishing irreducible water saturation, oil was displaced by constant-rate water injection. During this process, cumulative oil and water production as well as the corresponding pressure drop across the core were recorded. The Johnson-Bossler-Naumann (JBN) method was then applied to these production and pressure differential data to calculate oil and water relative permeability values at different water saturations. Discrete data points derived from this processing were used to construct the oil–water relative permeability curves.

2.3. Experimental Procedure

The experimental procedure consisted of three main phases: (1) Vacuum Saturation with Water: Core samples were subjected to vacuum saturation using water. (2) Establishing Irreducible Water Saturation: Simulated oil was injected to achieve irreducible water saturation. (3) Water Flooding and Data Processing: Oil displacement was performed via water flooding, followed by data processing to generate relative permeability curves.

Detailed Steps: (1) Core Preparation: Dry core samples were weighed to determine dry weight, and gas permeability was measured. (2) Vacuum Saturation and Water Permeability: Cores were vacuum-saturated with water for at least 24 h. Following saturation, 20 pore volumes (PV) of simulated formation water were injected to displace resident water. Water permeability was then measured, wet weight was recorded, and pore volume and porosity were calculated. (3) Oil Saturation and Irreducible Water Saturation: Simulated oil was injected until no further water production was observed after displacing more than 20 PV. The volume of produced water was used to calculate irreducible water saturation, and oil permeability at this saturation was determined. (4) Water Flooding Experiment: Water flooding was performed at a constant rate of 0.1 mL/min. Data on oil, water, and total liquid production, as well as pressure, were recorded at equal liquid production intervals. After water breakthrough, the recording frequency was increased. (5) Experiment Termination: The flooding process was terminated when the water cut consistently exceeded 99.95% over three consecutive recording intervals.

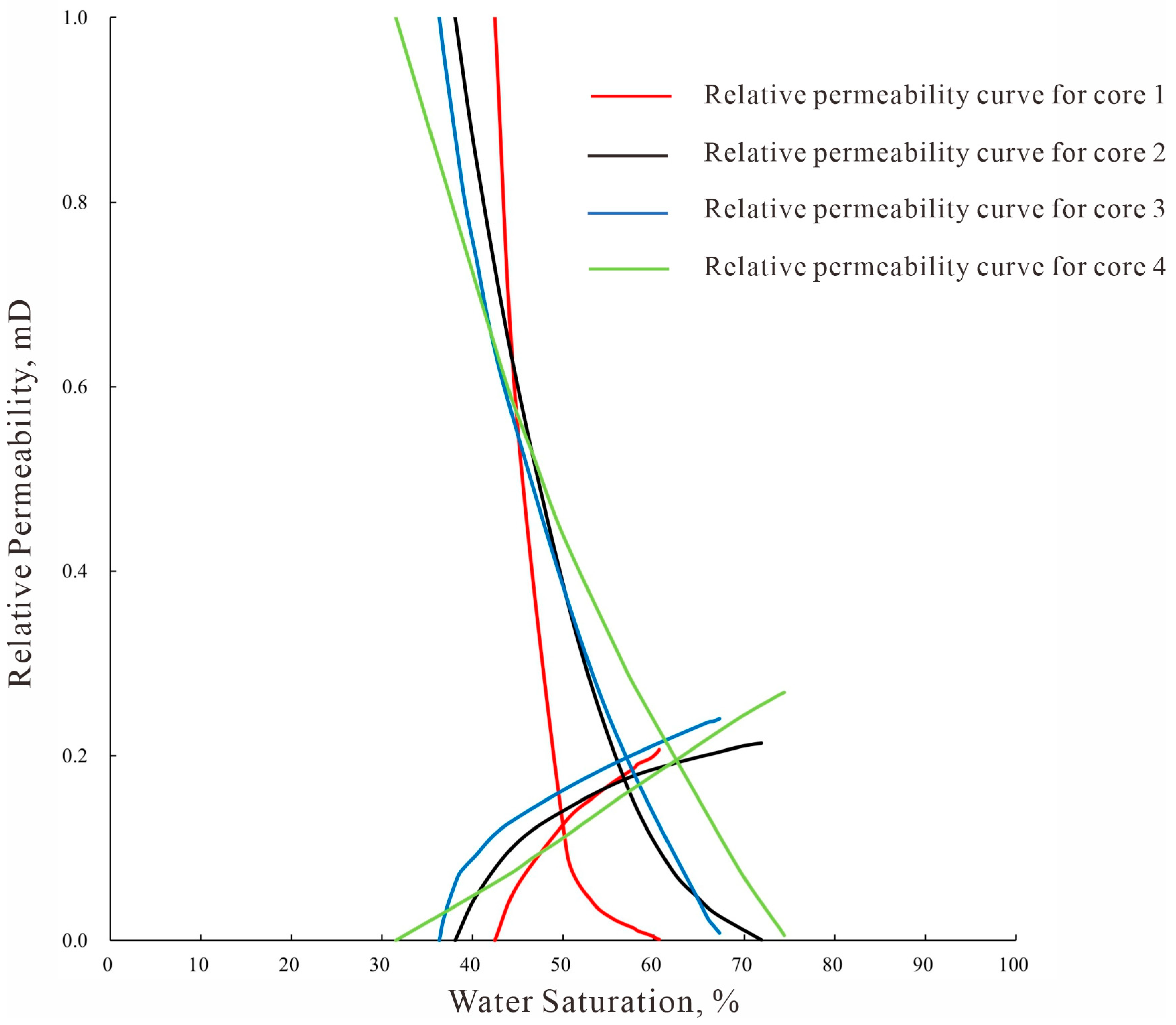

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the experimental data, each core flooding test was conducted under strictly controlled and consistent conditions. For each core sample, the entire water flooding process was performed once due to the time-intensive nature of the experiments and the use of native cores. However, key parameters such as porosity, absolute permeability, and initial fluid saturations were measured multiple times to confirm consistency prior to the displacement experiment. The discrete relative permeability data points obtained via the JBN method were fitted using a smoothing algorithm to generate continuous curves, which helps to mitigate the impact of random experimental scatter. The high consistency observed in the trends of the relative permeability curves across cores with similar permeability ranges (as shown in

Figure 1) further supports the robustness of our experimental approach.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

Core samples from the target reservoir block were selected to conduct four sets of oil–water relative permeability tests under varying permeability conditions at an experimental temperature of 50 °C. The experimental data is summarized in

Table 1.

3.1. Data Processing

In the analysis of unsteady-state oil–water relative permeability experiments, the JBN method and its modified versions are widely employed due to their established applicability [

12,

13]. However, practical application of the unsteady-state method often yields limited and scattered data points owing to experimental constraints and operational variables [

14,

15]. To address this limitation, we processed and analyzed the experimentally obtained relative permeability data using both the conventional JBN method and an improved version.

The data processing methodology was conducted as follows:

The oil phase relative permeability is calculated as follows:

The water phase relative permeability is calculated as follows:

The relative injectivity capacity is calculated as follows:

The water saturation at the core outlet is calculated as follows:

where

: Oil cut, dimensionless;

: Value of oil phase relative permeability, decimal;

: Value of water phase relative permeability, decimal;

: Value of dimensionless cumulative oil production, expressed as a fraction of pore volume;

: Value of dimensionless cumulative liquid production, expressed as a fraction of pore volume;

: Water phase viscosity, mPa·s;

: Oil phase viscosity, mPa·s;

: Value of relative injectivity;

: Value of liquid production rate at the core outlet at time

, cm

3/s;

: Value of oil production rate at the core outlet at the initial time, cm

3/s;

: Value of initial driving pressure difference, MPa;

: Value of displacement pressure difference at time

, MPa;

: Value of water saturation at the core outlet, decimal;

: Value of irreducible water saturation in the core, decimal.

3.2. Oil–Water Relative Permeability Curves and Characteristic Analysis

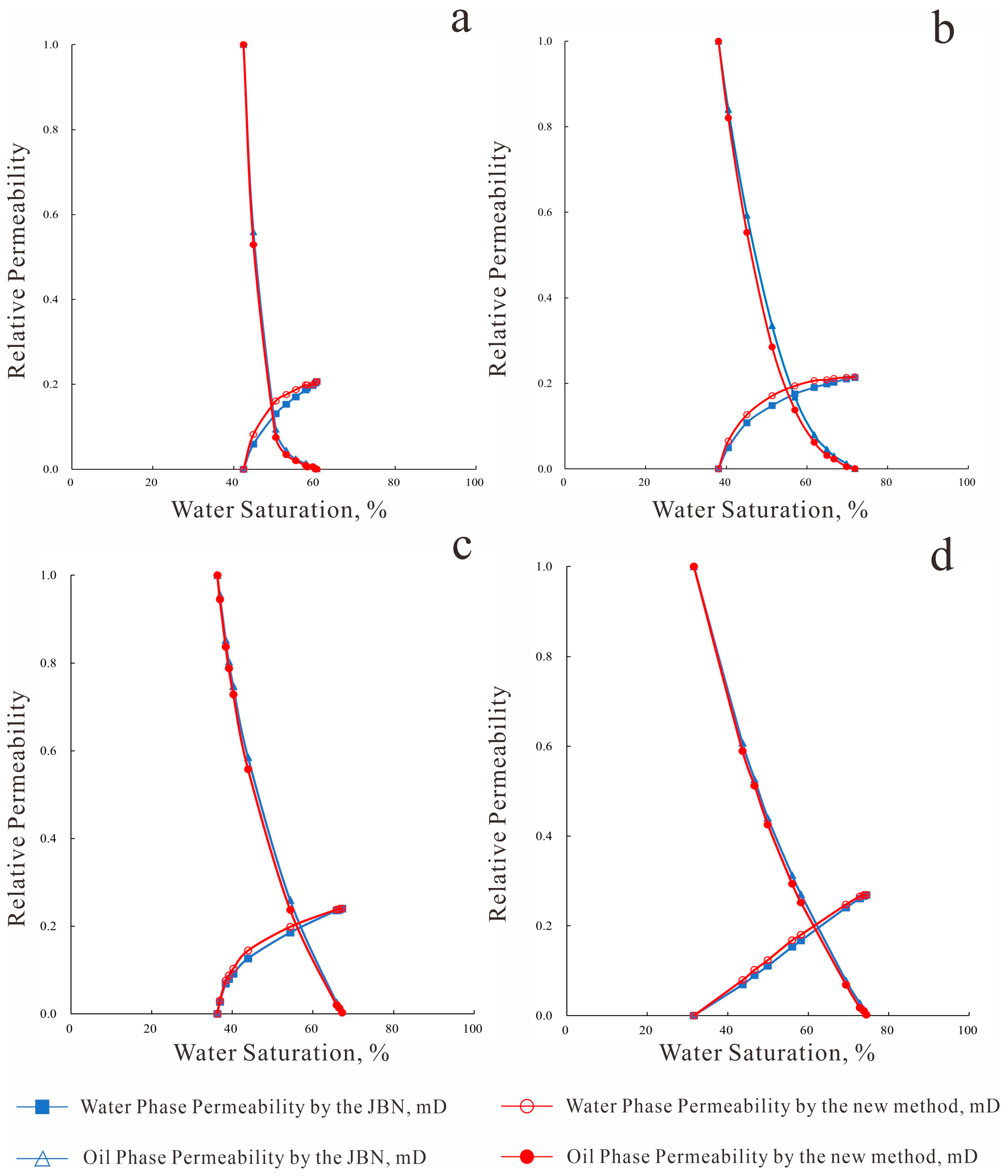

The relative permeability curves derived from data processing of the four core samples are presented in

Figure 1. Based on the morphology of the water-phase relative permeability curves, the oil–water relative permeability curves can be categorized into three types [

16,

17]: (1) Concave-downward water-phase curve, (2) Linear water-phase curve, (3) Concave-upward water-phase curve.

3.2.1. Concave-Downward Water-Phase Curve

The oil–water relative permeability curves for Core 1 (2.99 mD), Core 2 (7.33 mD), and Core 3 (26.62 mD) all display a characteristic concave-downward shape in the water-phase curve. This shape reflects a progressively slower increase in water-phase relative permeability as water saturation rises. Such behavior is commonly associated with clay-rich formations, in which sensitivity-induced damage during water flooding can compromise pore structure stability, diminish flow capacity, and ultimately restrict the improvement of effective water-phase permeability.

3.2.2. Linear Water-Phase Curve

The oil–water relative permeability curve of Core 4 (permeability: 34.40 mD) exhibits an approximately linear increase in water-phase relative permeability with rising water saturation. This linear trend is commonly associated with clay-bearing formations, where hydration and swelling of clay minerals during water flooding leads to structural alterations in pore networks, thereby modifying flow pathways and limiting further enhancement of effective water-phase permeability.

3.2.3. Concave-Upward Water-Phase Curve

This type of curve was not observed in the current experimental study.

Both linear and concave-downward water-phase relative permeability curves are considered atypical in conventional reservoir analysis. The mechanisms underlying these anomalous curves can be analyzed as follows: significant variations in physical properties within low-permeability reservoirs cause injected water to initially enter preferential flow pathways (larger pores), resulting in a rapid initial increase in water-phase relative permeability. As water injections continue (increasing both duration and volume), water gradually propagates into secondary pore networks (smaller pores), substantially increasing flow resistance. During the later stages of displacement, the predominant flow channels become water-occupied, while residual oil moves as dispersed oil droplets. When these droplets pass through narrow pore throats, the Jamin effect is readily triggered, creating additional resistance that impedes the flow of both phases and consequently slows or stagnates the growth of water-phase relative permeability [

6].

Enhanced reservoir heterogeneity and lower absolute permeability intensify these flow resistance effects. Furthermore, the typically high oil–water viscosity ratios in low-permeability reservoirs exacerbate microscopic fingering phenomena, leading to characteristic non-piston-like displacement patterns during water flooding. The interplay between heterogeneity and viscosity ratio governs the degree of deviation in curve morphology. A moderate combined influence tends to produce linear water-phase relative permeability curves, whereas pronounced synergistic effects more likely result in concave-downward water-phase curves [

18,

19].

A comparative analysis of the four core samples with varying permeabilities reveals that higher permeability corresponds to more favorable oil–water flow characteristics (

Figure 1), which are manifested in three key aspects. First, cores with enhanced permeability demonstrate higher water-phase relative permeability and an elevated equipermeability point. Second, improved pore connectivity in these cores leads to reduced irreducible water saturation and lower residual oil saturation. Third, examination of the two-phase flow region across Cores 1–4 indicates that increased permeability not only expands the two-phase co-flow range but also shifts the equipermeability point toward higher water saturations.

4. Research on Seepage Mechanisms in Low-Permeability Reservoirs

Both in experimental and theoretical studies, the threshold pressure gradient is widely employed to characterize flow behavior in low-permeability reservoirs. This parameter provides a theoretical foundation for describing nonlinear flow through low-permeability porous media [

20,

21,

22]. When determining oil–water relative permeability in such reservoirs, the classical JBN method is generally modified by incorporating the threshold pressure gradient. This adjustment enables a more accurate representation of relative permeability behavior under low-velocity non-Darcy flow conditions [

23]. To describe non-Darcy flow, a modified Darcy’s law incorporating “apparent permeability” can be employed. This approach utilizes a dynamic permeability value that maintains the form of the classical equation while accurately characterizing nonlinear flow characteristics [

23].

To further elucidate two-phase flow mechanisms in low-permeability reservoirs, this study begins by designing and conducting experimental measurements of the quasi-threshold pressure gradient during two-phase flow through low-permeability sandstone cores under varied physical properties and water saturation conditions. A mathematical model describing the two-phase quasi-threshold pressure gradient was established by correlating the injected liquid water cut with the normalized quasi-threshold pressure gradient, effectively coupling rock physical parameters with water saturation.

Building on non-Darcy flow theory, we subsequently developed a computational model for estimating relative permeability during unsteady-state water flooding in low-permeability sandstone reservoirs that incorporates the dynamic quasi-threshold pressure gradient. By integrating this gradient characterization model with the relative permeability calculation framework, we ultimately established a novel methodology for determining oil–water relative permeability under unsteady-state conditions in such reservoirs. The resulting oil–water relative permeability curves enable systematic analysis of two-phase flow behavior in low-permeability sandstones. Comparative assessment with the traditional Johnson-Bossler-Naumann (JBN) method confirms the rationality and superiority of the proposed model in representing low-velocity non-Darcy flow phenomena.

4.1. Characterization Method for Two-Phase Flow Threshold Pressure Gradient in Low-Permeability Sandstone Cores

4.1.1. Flow Characteristics at Different Water Saturations in Low-Permeability Sandstone Cores

In the quasi-threshold pressure gradient measurements for low-permeability sandstone cores, we used native core samples and maintained the experimental temperature at 50 °C. The test fluids included simulated oil prepared by blending crude oil with kerosene to achieve a viscosity of 6.44 mPa·s and synthetic formation water. The water cut of the injected fluid (denoted as F

w to distinguish it from the produced water cut f

w discussed subsequently) was controlled by adjusting the oil–water ratio, with values set at 0%, 27%, 53%, 76%, and 100%. The relationship between in situ water saturation in the core and the injected fluid water cut F

w follows an established mathematical model [

23]:

where

: Water saturation, %;

: Irreducible water saturation, %;

: Maximum water saturation, %;

: Water content in the injected fluid, %.

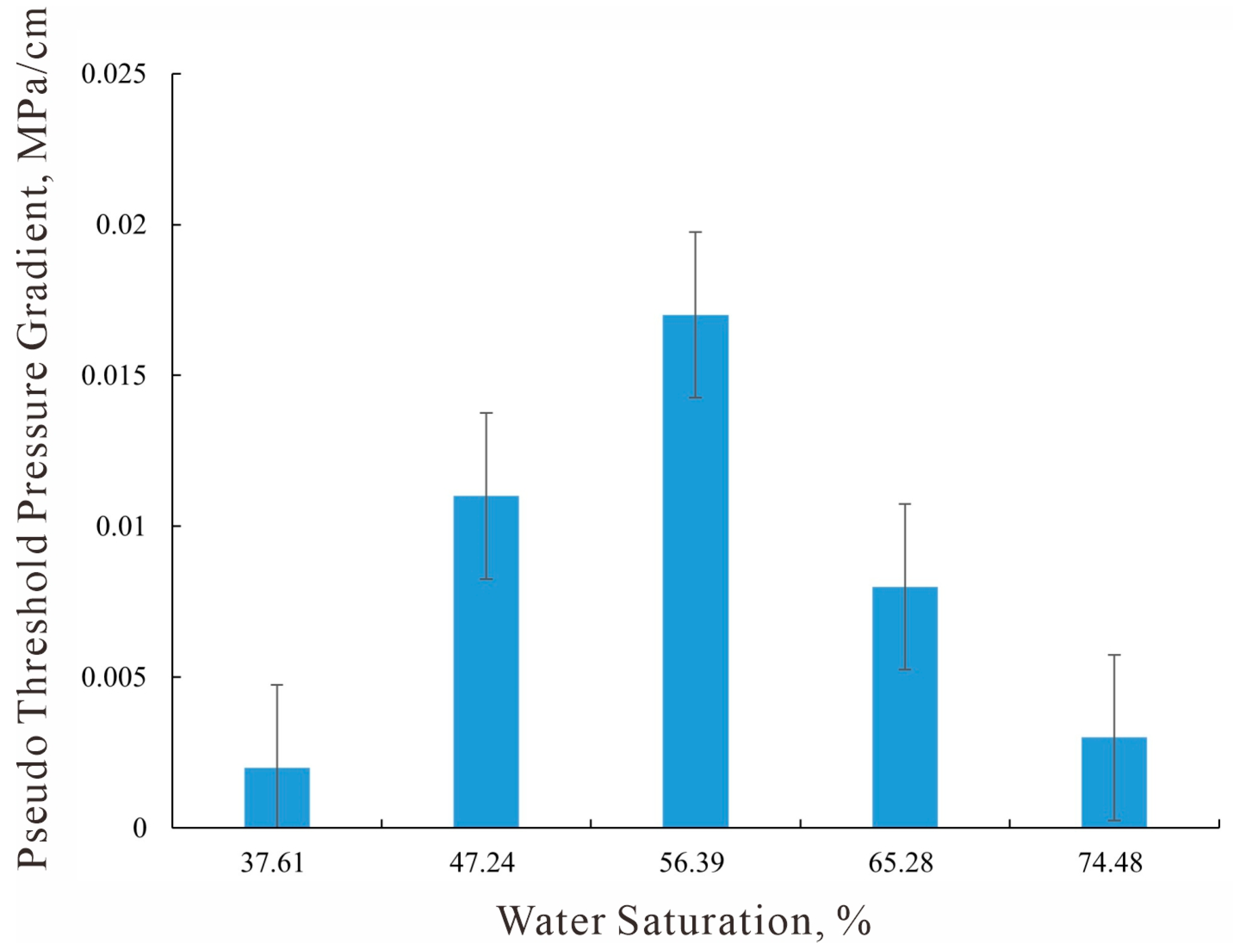

Figure 2 presents the oil–water two-phase flow characteristics of a typical low-permeability sandstone core at different water saturations (37.61%, 47.24%, 56.39%, 65.28%, and 74.48%). The results demonstrate that while the oil phase flow generally follows Darcy’s law at irreducible water saturation with no significant nonlinearity, distinct non-Darcy flow behavior emerges during the two-phase flow stage. This nonlinear characteristic substantially diminishes by the residual oil stage. As further revealed in

Figure 3, the pseudo threshold pressure gradient exhibits a unimodal trend with increasing water saturation, rising initially before declining and peaking at a specific saturation level.

4.1.2. Characterization Method for Quasi-Threshold Pressure Gradient in Low-Permeability Sandstone Cores

In low-permeability porous media reservoirs, gas flow exhibits a slip effect, making it difficult for air permeability to fully characterize the true seepage capacity of the core. However, the permeability corrected by the Klinkenberg method can more accurately reflect the fluid permeability of the core [

24]. Therefore, this paper fits the corrected permeability with the experimental results of the maximum pseudo-startup pressure gradient. As shown in

Figure 4, around the corrected permeability of 10 mD, the maximum pseudo-startup pressure gradient exhibits two distinct trends with increasing corrected permeability: before 10 mD, the maximum pseudo-startup pressure gradient decreases sharply, while after 10 mD, the decline becomes more gradual. To better reflect this variation, an empirical relationship was derived through segmented fitting as follows [

23]:

where

: Maximum pseudo threshold pressure gradient in two-phase flow, MPa/cm;

: The corrected permeability of the core, mD.

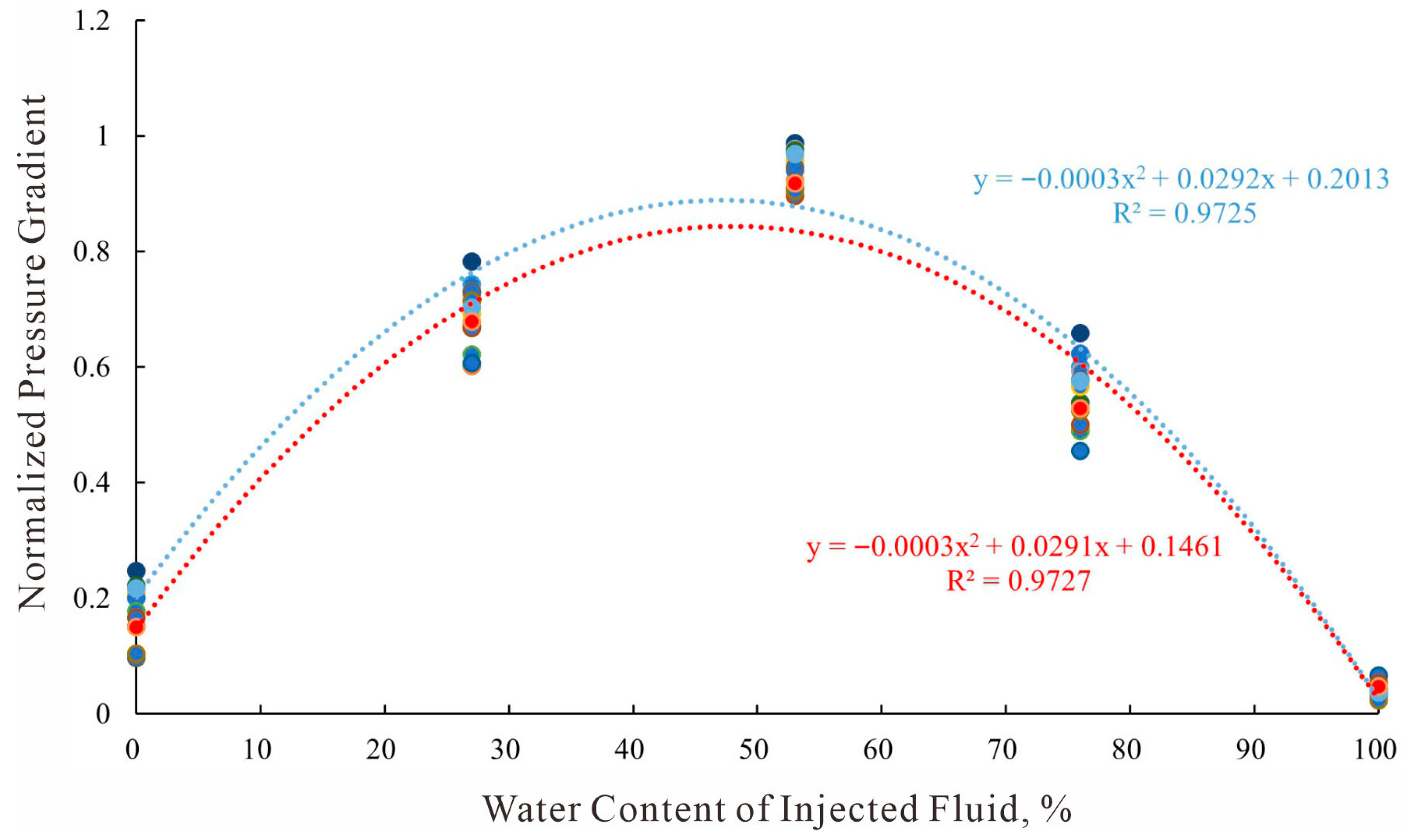

The pseudo threshold pressure gradient for each core at different water saturations was normalized (by dividing by the corresponding maximum pseudo threshold pressure gradient), and the normalized results were plotted against the water content percentage (F

w) of the injected fluid (

Figure 5). Based on the two segments of data points in

Figure 5, a regression analysis was performed, yielding the following relationship [

23]:

where

: Normalized pseudo threshold pressure gradient, dimensionless.

As shown in

Figure 5, the normalized pseudo threshold pressure gradient exhibits a significant correlation with F

w (correlation coefficients R

12 = 0.9725, R

22 = 0.9727). By combining Equations (6)–(8), a relational expression describing the quantitative relationship between the pseudo threshold pressure gradient in two-phase flow and the core’s corrected permeability and water saturation can be derived:

where

: Pseudo threshold pressure gradient in two-phase flow, MPa/cm.

Equation (9) provides the mathematical representation of the pseudo threshold pressure gradient for oil–water two-phase flow in low-permeability sandstone cores.

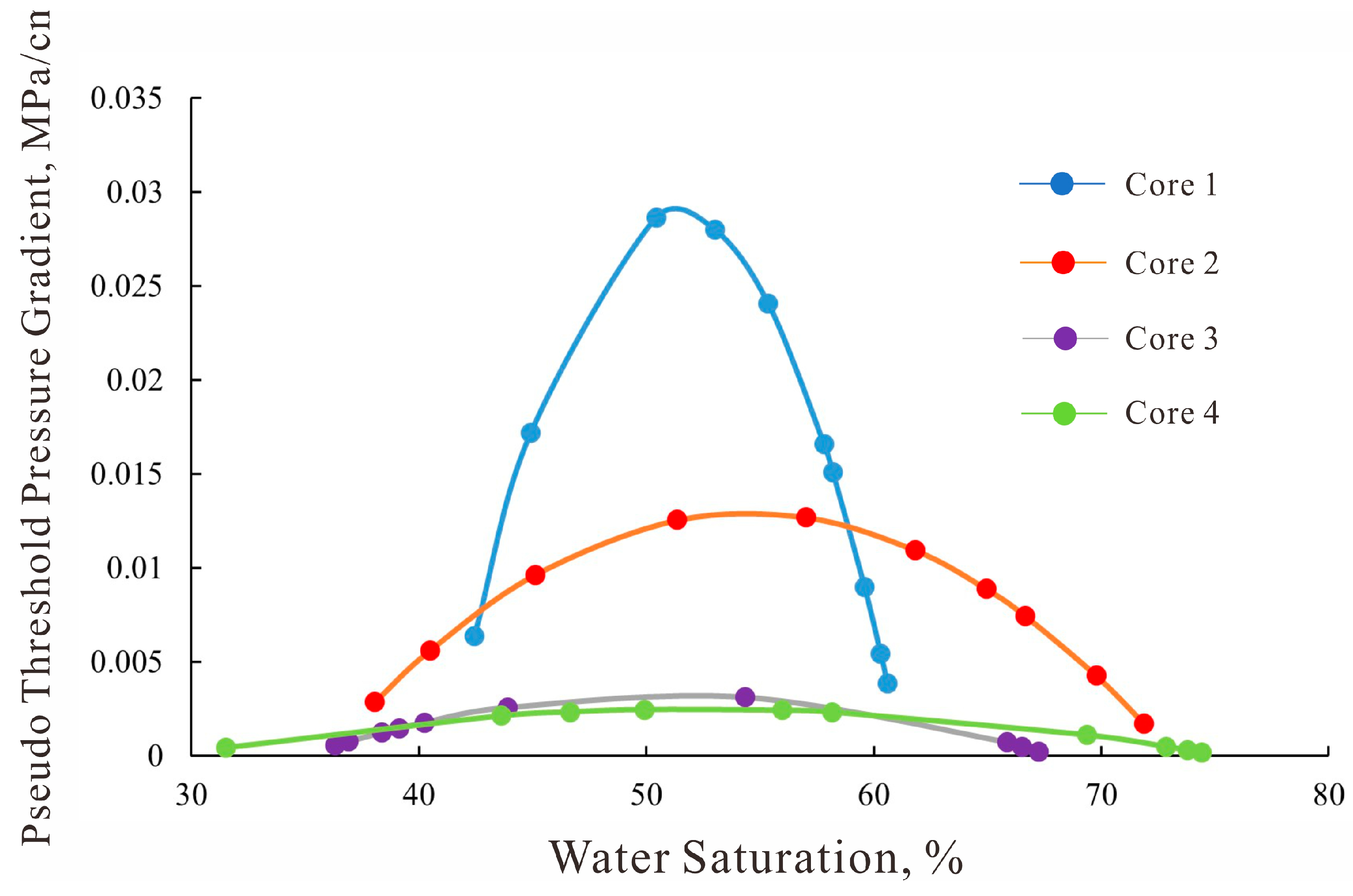

Figure 6 displays the simulated pseudo threshold pressure gradient under varying water saturations for four low-permeability sandstone cores with different permeabilities. The results indicate that the pseudo threshold pressure gradient decreases with increasing core permeability, while following a nonlinear trend initially rising and then declining as water saturation increases. This behavioral pattern is in general agreement with the experimental measurements.

4.2. Calculation Method for Oil–Water Relative Permeability in Low-Permeability Cores

In low-permeability sandstone reservoirs, fluid flow often deviates from Darcy’s law, and its motion equation must be characterized using a piecewise function [

25]. To accurately describe such oil–water two-phase flow processes, a threshold pressure gradient is introduced to construct a mathematical model for oil–water two-phase flow [

26].

The model is based on the following fundamental assumptions: (1) The medium is incompressible and saturated with oil, water, or both oil and water. (2) During the flow process, water and oil are immiscible, incompressible Newtonian fluids, and exhibit a dynamic threshold pressure gradient λ. (3) The one-dimensional high-pressure constant-rate displacement experiment neglects the effects of capillary pressure and gravity. (4) The pseudo threshold pressure gradient in two-phase flow only affects the initial value of fluid flow. During the flow process, the relationship between displacement velocity and pressure gradient remains within the quasi-linear region of non-Darcy flow. Therefore, under certain conditions, the Buckley-Leverett equation and the generalized Darcy’s law hold valid in the derivation process [

27,

28,

29].

4.2.1. Apparent Viscosity—Pore Volume Injected Relationship Equation

Darcy’s law incorporating the threshold pressure gradient:

where

;

: water flow velocity, cm/s;

: oil flow velocity, cm/s;

: absolute permeability of the core, mD;

: water phase relative permeability, dimensionless;

: oil phase relative permeability, dimensionless;

: viscosity of water, mPa·s;

: viscosity of oil, mPa·s;

: threshold pressure gradient of the water phase, MPa/cm;

: threshold pressure gradient of the oil phase, MPa/cm.

Since

, the total flow velocity (which is a constant under constant-rate displacement conditions) can be expressed as:

When the oil phase begins to mobilize, the expression for the pressure gradient can be derived as follows:

Integrating along the core length, the pressure difference across the core can be expressed as:

The dimensionless pressure is defined as

. Substituting

into the equation and simplifying yields:

where

A—Core cross-sectional area, cm

2;

ϕ—Core porosity, decimal.

4.2.2. Fractional Flow Equation

The water cut

is defined as the ratio of the water phase flow rate to the total flow rate:

Substituting Equations (11) and (13) into Equation (14) yields:

To simplify the above equation, two intermediate variables are introduced: the mobility ratio

and the total mobility

. Substituting

and

into Equation (15) and simplifying yields the fractional flow equation:

4.2.3. Introduction of Dimensionless Distance and the Welge Equation

To compute the integral in Equation (15), the dimensionless distance

is introduced, and the limits of integration become 0 to 1:

According to the Welge equation [

30,

31], at the core outlet (

):

And the water saturation profile satisfies:

Transforming the integral variable in Equation (19) from

to

, with the limits of integration changing from

to

:

Define the function

:

Then Equation (23) can be rewritten as:

Let

. Then:

Differentiating Equation (25):

where

Since the frontal water saturation

remains essentially constant after breakthrough,

. Meanwhile,

. Therefore:

The Welge equation is derived based on material balance and its validity does not depend on the specific form of Darcy’s law [

30,

31]. Therefore, even when considering different threshold pressure gradients, the Welge equation still holds. Starting from the outlet water saturation

and differentiating with respect to

:

where the average water saturation

, and thus

. Since

(oil production rate), it follows that:

where

—Irreducible water saturation, dimensionless;

—Injected pore volume, dimensionless;

—Cumulative oil production, mL;

—Pore volume of the core, dimensionless.

Continuing with the differentiation of Equation (20):

Thus, the following can be obtained:

Substituting Equation (33) into Equation (29) and combining it with the function

, we obtain:

Substituting Equation (34) into Equation (27) yields the derivative of

with respect to

:

Combining Equation (26) with the definition of

, and further applying the fractional flow equation along with the introduction of the oil cut

, the simplified form of Equation (35) can ultimately be derived as:

4.2.4. Oil–Water Relative Permeability Calculation Formula

Since

, the formula for oil phase relative permeability can be derived from Equation (36) as:

Furthermore, the ratio of oil–water relative permeability can be obtained from the fractional flow Equation (18):

Therefore, the formula for the oil phase relative permeability is:

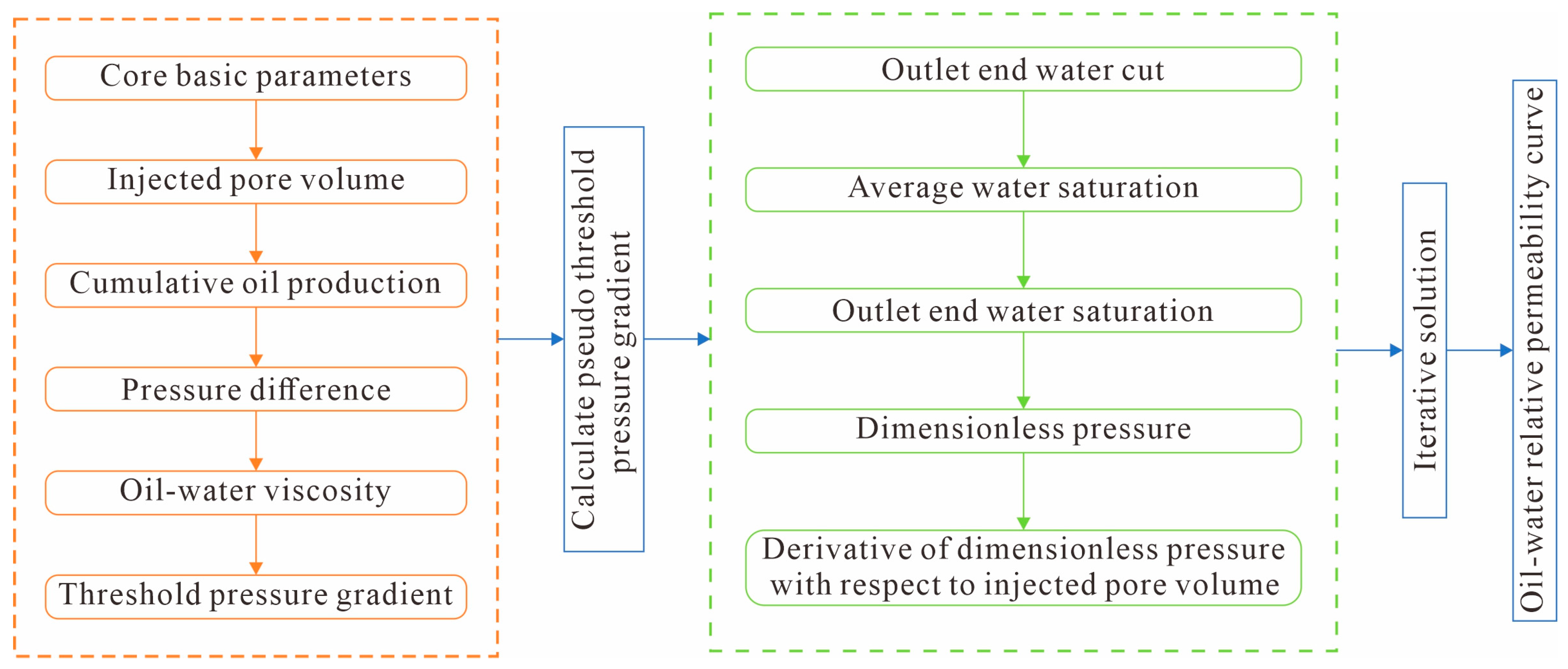

As can be seen from the oil phase relative permeability Formula (37), the first part is entirely consistent with the traditional JBN formula, while the second part is the correction term for the threshold pressure gradient, fully accounting for the influence of the dynamic threshold pressure gradient. The magnitude of the correction term depends on : when , the correction term is less than 1, and the calculated will be smaller than the result from the traditional method, which aligns with experimental observations. When both and are zero, the relative permeability formula simplifies to the traditional JBN form, validating the derivation process. It is important to note that appears on both sides of the equation, necessitating an iterative solution: (1) Use the traditional JBN formula to calculate an initial guess ; (2) Substitute this into the correction term on the right side of the formula to compute a new ; (3) Compare and . If the difference exceeds the preset tolerance, set as the new guess and return to step (2); (4) Iterate until convergence is achieved, yielding the final .

Specific steps for solving oil–water relative permeability: First, obtain a series of experimental parameters through experiments (such as core basic parameters, injected pore volume multiples

, cumulative oil production

, pressure difference

, oil–water viscosities, and threshold pressure gradients, etc.). Next, using the two-phase flow pseudo-threshold pressure gradient characterization method, calculate the pseudo-threshold pressure gradient of the tested core at different water saturations. Then, based on the above experimental parameters, compute the water cut at the core outlet, average water saturation, water saturation at the outlet, dimensionless pressure, and the derivative of dimensionless pressure with respect to injected pore volume multiples at each time point. Finally, determine the oil–water two-phase relative permeability in low-permeability reservoirs using the iterative method. The flowchart is shown in

Figure 7.

4.3. Result Validation

The oil–water relative permeability curves obtained using the new method were systematically compared with those derived from the conventional JBN approach.

Figure 8 presents the measured and calculated oil–water relative permeability curves from both methods. Comparative analysis reveals that the new method generally yields lower oil-phase relative permeability and higher water-phase relative permeability compared to the traditional JBN method. Notably, the discrepancy between the two methods initially increases and then decreases with rising water saturation. Furthermore, as permeability increases, the differences between the curves generated by the new method and the JBN method diminish.

This behavior can be attributed to the incorporation of the threshold pressure gradient in the new algorithm. By quantitatively accounting for the additional pressure drop caused by the pseudo-threshold pressure gradient during data processing, the new method reduces calculated oil-phase relative permeability while increasing water-phase relative permeability. As permeability increases, the additional pressure drops induced by the pseudo-threshold pressure gradient decreases, leading to a gradual convergence between the relative permeability values obtained from the new method and those from the JBN approach.

5. Discussion

This study successfully developed a novel relative permeability model that dynamically incorporates the quasi-threshold pressure gradient, providing a more accurate characterization of two-phase flow in low-permeability sandstone reservoirs. The findings and their implications are discussed within the context of current technological advancements and existing literature.

5.1. Limitations of the Study

While the proposed model demonstrates improved predictive accuracy for characterizing oil–water flow behavior in low-permeability reservoirs, several limitations and underlying assumptions should be acknowledged to guide future research and practical applications [

28,

32,

33].

Assumptions in the Theoretical Model: The derivation of the new relative permeability model is based on several simplifying assumptions, including: (1) the porous medium is rigid and incompressible; (2) both oil and water are immiscible, incompressible Newtonian fluids; (3) capillary and gravitational forces are neglected; and (4) the quasi-threshold pressure gradient primarily influences the flow initiation stage, after which the flow follows a non-Darcy quasi-linear regime. Although these assumptions facilitate model tractability, they may not fully capture the complex multi-physics coupling effects such as rock-fluid interactions, wettability alteration, or time-dependent permeability damage that can occur during long-term water flooding in sensitive low-permeability formations.

Experimental Constraints: The experiments were conducted using native cores from a single reservoir block in the Oilfield, with permeability ranging from 2.99 to 34.40 mD. While this range is representative of many low-permeability sandstone reservoirs, the applicability of the derived empirical relationships (e.g., Equation (9)) to reservoirs with significantly different lithology, higher clay content, or broader permeability ranges (e.g., ultra-tight or fractured reservoirs) remains to be validated. Moreover, all experiments were performed at a constant temperature (50 °C) and with a specific oil–water viscosity ratio. Variations in reservoir temperature, fluid properties, or salinity may influence the quasi-threshold pressure gradient and relative permeability behavior [

34,

35].

Model Applicability and Scalability: The characterization model for the quasi-threshold pressure gradient (Equation (9)) was calibrated using core-scale experimental data. Its direct extrapolation to field-scale simulations requires careful consideration of heterogeneity and upscaling effects. Although the model incorporates dynamic saturation dependent behavior, it does not explicitly account for spatial variability in pore structure or mineral composition, which could lead to localized deviations in threshold behavior. Additionally, the current form of the model is tailored for water-wet or weakly water-wet systems; its performance in oil-wet or mixed-wet low-permeability rocks warrants further investigation [

36,

37,

38].

5.2. Bridging the Gap Between Laboratory Measurements and Field-Scale Predictions

The ultimate value of the dynamic relative permeability model established in this study lies in its ability to accurately predict and optimize field-scale development strategies. Integrating such physically grounded models, derived from core-scale experiments, into reservoir numerical simulators constitutes a critical bridge connecting laboratory findings with practical field applications.

The core of this integration involves incorporating the dynamic quasi-threshold pressure gradient as a variable, dynamically linked to reservoir properties and fluid saturations, into the simulator’s constitutive relationships. The implementation pathway entails modifying the fluid flow equations within the reservoir simulator, extending the traditional Darcy’s law to a non-Darcy flow formulation that includes the threshold pressure gradient. The mathematical model proposed in this study, with its explicit functional form, facilitates integration through user-defined modules or by modifying simulator keywords. Specifically, for each grid block and at each timestep, the simulator can dynamically calculate the corresponding quasi-threshold pressure gradient value based on the block’s corrected permeability and current water saturation, treating it as an additional flow resistance.

This integration approach significantly enhances the simulator’s capability to capture the non-piston-like water displacement behavior characteristic of low-permeability reservoirs. During history matching, this model is expected to more accurately reproduce the water breakthrough time and water cut rise trend in production wells, as it intrinsically accounts for the additional energy loss due to the threshold pressure effect. For development strategy forecasting, the model can provide a more reliable theoretical basis for optimizing pattern design, determining the appropriate range of injection pressure, and planning enhanced oil recovery (EOR) strategies. Consequently, it helps build a more physically accurate “digital twin” of the low-permeability reservoir within the digital domain, thereby supporting more refined and scientific development decisions.

5.3. Implications for EOR and Digital Transformation in Tight Reservoirs

Accurately quantifying two-phase flow behavior is fundamental to designing effective enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques. Our findings indicate that energy loss attributable to the quasi-threshold pressure gradient significantly contributes to low displacement efficiency. This understanding enables the development of targeted EOR strategies to counteract this effect, such as optimizing injection water salinity to minimize clay-induced formation damage or employing viscosified fluids (e.g., polymer solutions) to suppress fingering and improve sweep efficiency. Furthermore, the mathematically robust formulation of our model facilitates its integration into digital twin frameworks for smart field management. Key parameters (a, b, c) in the new model could potentially be inverted from real-time pressure and production data using machine learning algorithms, creating a dynamic, self-calibrating representation of reservoir flow capacity that continuously optimizes development strategies.

6. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the oil–water relative permeability characteristics and seepage mechanisms in low-permeability sandstone reservoirs through integrated experimental and theoretical modeling. The principal conclusions are summarized as follows:

A dynamic quasi-threshold pressure gradient was identified during two-phase flow, which initially increases with water saturation to a peak value before gradually decreasing. A robust mathematical characterization model was successfully established, coupling this gradient with the core’s corrected permeability and water saturation. Building upon this, a novel relative permeability calculation model for unsteady-state water flooding was derived, which dynamically incorporates the quasi-threshold pressure gradient, thereby providing a more accurate description of non-Darcy flow.

Finally, comparative validation confirmed the superiority of the new model over the traditional JBN method. The proposed model yields lower oil-phase relative permeability and higher water-phase relative permeability, with the discrepancy diminishing as permeability increases. This model offers a more reliable theoretical foundation for optimizing water flooding design and predicting production performance in low-permeability reservoirs, with significant implications for enhancing recovery. Future work should focus on extending the model’s applicability to more complex conditions such as fractured, oil-wet systems and varying temperature and salinity environments.

Author Contributions

Validation, Z.Y.; Investigation, L.Z.; Resources, H.Y.; Data curation, H.Y., Y.W. and Z.Y.; Writing—original draft, B.L., Z.Y. and L.Z.; Writing—review & editing, B.L.; Project administration, B.L., H.Y. and Y.W.; Funding acquisition, B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Open Foundation Project of Research and Development Center for the Sustainable Development of Continental Sandstone Mature Oilfield by National Energy Administration: “Research on Experimental Analysis and Quantitative Characterization of Water Injection Resistance in Low-Permeability Reservoirs (33550000-22-ZC0613-0206)”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Baoyou Guo, Chuan Jing, and Jun Chen for their help in data analysis. Special acknowledgment is extended to the Research and Development Center for the Sustainable Development of Continental Sandstone Mature Oilfield by National Energy Administration for providing the experimental facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Hongmin Yu and Youqi Wang were employed by the Sinopec Petroleum Exploration and Production Research Institute. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Li, N.; Zhu, S.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Long, B.; Chen, F.; Wang, E.; Feng, W.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Fracturing-flooding technology for low permeability reservoirs: A review. Petroleum 2024, 10, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhadi, D.; Ali, J.A.; Hama, S.M. Advanced Techniques for Improving the Production of Natural Resources from Unconventional Reservoirs: A State-of-the-Art Review. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 10853–10876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.L.; Zhou, B.B.; Issakhov, M.; Gabdullin, M. Advances in enhanced oil recovery technologies for low permeability reservoirs. Pet. Sci. 2022, 19, 1622–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, B.; Wang, Y.; Yu, M.; Yang, M.; Meng, W.; Yi, H.; et al. A comprehensive model for oil-water relative permeabilities in low-permeability reservoirs by fractal theory. Fractals 2020, 28, 2050055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, S.M.; Sohrabi, M. Relative permeabilities hysteresis for oil/water, gas/water and gas/oil systems in mixed-wet rocks. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 161, 559–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.A.; Zendehboudi, S.; Dusseault, M.B.; Chatzis, I. Evolving simple-to-use method to determine water-oil relative permeability in petroleum reservoirs. Petroleum 2016, 2, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Tang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Characterization of extra low-permeability conglomerate reservoir and analysis of three-phase seepage law. Processes 2023, 11, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teige, G.M.; Thomas, W.L.; Hermanrud, C.; Øren, P.E.; Rennan, L.; Wilson, O.B.; Nordgård Bolås, H.M. Relative permeability to wetting-phase water in oil reservoirs. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2006, 111, B12204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ren, Z.; Li, P.; Liu, J. Microscopic pore-throat structure variability in low-permeability sandstone reservoirs and its impact on water-flooding efficacy: Insights from the Chang 8 reservoir in the Maling Oilfield, Ordos Basin, China. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2024, 42, 1554–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Huang, K.; Ma, C.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Y. Analysis of relative permeability curves under different reservoir conditions. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2012, 12, 3340–3343. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 28912-2012; Determination of Oil-Water Relative Permeability by Unsteady-State Method. National Standards of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Li, K.; Luo, M.; Wang, J. Improvement of JBN method and corresponding calculation and plotting software. Pet. Explor. Dev. 1994, 21, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, D. Processing method for unsteady-state relative permeability experimental data. J. Southwest Pet. Univ. (Sci. Technol. Ed.) 2014, 36, 110–116. [Google Scholar]

- Shahverdi, H.; Sohrabi, M.; Jamiolahmady, M. A new algorithm for estimating three-phase relative permeability from unsteady-state core experiments. Transp. Porous Media 2011, 90, 911–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Li, A.; Fu, S.; Wang, S. Experimental study on the oil-water relative permeability relationship for tight sandstone considering the nonlinear seepage characteristics. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 161, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhametdinova, A.; Yunusov, T.; Bakulin, D.; Grishin, P.; Cheremisin, A. Experimental Study of Two-Phase Fluid Flow and Relative Permeability in Low-Permeability Rocks. In Proceedings of the SPE Gas & Oil Technology Showcase and Conference 2025, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 21–23 April 2025; SPE: Richardson, TX, USA, 2025. D021S026R002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tang, H.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Y. Analysis and application of oil-water relative permeability curves in the middle-deep reservoir of Nanpu No.2 Structure. Pet. Geol. Eng. 2015, 29, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Xi, W.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, Y. Analysis and Evaluation of Oil-water Relative Permeability Curves. Open Pet. Eng. J. 2015, 8, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, R.S.; Tareen, M.Y.K.; Mengel, A.; Shah, S.A.R.; Iqbal, J. Simulation study of relative permeability and the dynamic capillarity of waterflooding in tight oil reservoirs. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2020, 10, 1891–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, E.; Liu, C. Theory of oil-water two-phase flow with threshold pressure gradient and calculation method of development indicators. Pet. Explor. Dev. 1998, 25, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Song, F.; Liu, C.; Li, F. One-dimensional transient pressure analysis for low-permeability media with threshold pressure gradient. Appl. Math. Mech. 1999, 20, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Liu, P.; Xu, G.; Zhang, L.; Nie, J. Study on threshold pressure gradient of polymer flooding in low-permeability reservoirs. J. China Univ. Pet. (Ed. Nat. Sci.) 2015, 39, 126–130. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, B.; Miskimins, J.L. A new technique for accurately measuring two-phase relative permeability under non-Darcy flow conditions. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2015, 127, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Li, A.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, K.; Chen, M. Experimental study on unsteady-state gas permeability considering slip effect. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2015, 26, 733–736. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, E.; Liu, C. Mathematical model for nonlinear flow in low-permeability reservoirs and its application. Acta Pet. Sin. 2001, 22, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Fang, F.; Song, K.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Cao, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Bian, C. Research progress on the method of determining gas-water relative permeability curve in unconventional reservoirs. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2025, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K. Study on Calculation Methods and Patterns of Relative Permeability Curves in Low-Permeability Reservoirs. Master’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Doster, F.; Hilfer, R. Generalized Buckley-Leverett theory for two-phase flow in porous media. New J. Phys. 2011, 13, 123030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spayd, K.; Shearer, M. The Buckley-Leverett equation with dynamic capillary pressure. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2011, 71, 1088–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, R. A further study on Welge equation. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2018, 36, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sarihi, A.; You, Z.; Behr, A.; Genolet, L.; Kowollik, P.; Zeinijahromi, A.; Bedrikovetsky, P. Admissible parameters for two-phase coreflood and Welge-JBN method. Transp. Porous Media 2020, 131, 831–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schembre, J.M.; Kovscek, A.R. A technique for measuring two-phase relative permeability in porous media via X-ray CT measurements. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2003, 39, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvazdavani, M.; Masihi, M.; Ghazanfari, M.H. Monitoring the influence of dispersed nano-particles on oil-water relative permeability hysteresis. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2014, 124, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, B.S.; Rashidi, F.; Babadagli, T. Temperature effects on the heavy oil/water relative permeabilities of carbonate rocks. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2007, 59, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudle, B.H.; Slobod, R.L.; Brownscombe, E.R. Further developments in the laboratory determination of relative permeability. J. Pet. Technol. 1951, 3, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanbakhsh, A.; Shahverdi, H.; Sohrabi, M. Gas/oil relative permeability normalization: Effects of permeability, wettability, and interfacial tension. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2016, 19, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goda, H.M.; Behrenbruch, P. Using a modified Brooks-Corey model to study oil-water relative permeability for diverse pore structures. In Proceedings of the SPE Asia Pacific Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition 2004, Perth, Australia, 20–22 October 2004; SPE: Richardson, TX, USA, 2004. SPE-88538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, N.; Cullick, A.S.; Honarpour, M.M. Effective relative permeability in scale-up and simulation. In Proceedings of the SPE Rocky Mountain Petroleum Technology Conference/Low-Permeability Reservoirs Symposium 1995, Denver, CO, USA, 20–22 March 1995; SPE: Richardson, TX, USA, 1995. SPE-29592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).