Quantifying Weather’s Share in Dynamic Grid Emission Factors via SHAP: A Multi-Timescale Attribution Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Preprocessing

2.1.1. Dataset Description

2.1.2. Preprocessing Workflow

2.1.3. Data Splitting Strategy

2.2. Model Architecture and Training

2.2.1. Theoretical Basis for Model Selection

- High Efficiency with Large-Scale Data: Our dataset consists of high-resolution, city-level hourly time series. LightGBM’s histogram-based algorithm and Gradient-based One-Side Sampling (GOSS) technique significantly accelerate the training process and reduce memory consumption compared to traditional Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT) or Random Forests, making it highly scalable for our data volume [16].

- Superior Accuracy and Handling of Non-linearity: The relationships between meteorological variables, temporal features, and carbon intensity are complex and inherently non-linear. LightGBM, through its leaf-wise growth strategy, effectively captures these intricate interactions and non-linear patterns, often yielding higher accuracy than linear models (e.g., Lasso, Ridge Regression) and comparable or better performance than other tree-based ensembles like XGBoost, especially on large datasets.

- Robustness and Practicality: The model exhibits strong robustness to outliers and multicollinearity, which are common in meteorological data (e.g., temperature and humidity can be correlated). This is a practical advantage over models like Support Vector Machines (SVMs) or neural networks, which often require more meticulous data scaling and are more sensitive to hyperparameter tuning.

- Synergy with SHAP for Interpretability: A core contribution of this work is interpretable attribution. Tree-based models like LightGBM have a native and computationally efficient integration with the SHAP framework via the TreeSHAP algorithm [17]. This allows for exact and fast calculation of Shapley values, which is computationally prohibitive for many other model classes (e.g., neural networks) where approximate SHAP methods are necessary. This synergy was a decisive factor in our model selection.

2.2.2. Theory of Hyperparameter Optimization

- Number of trees: ;

- Learning rate: ;

- Maximum tree depth: ;

- Minimum number of samples per leaf node: .

2.2.3. Theory of Training Process

2.3. SHAP Attribution Framework

2.3.1. Principle of SHAP Value Calculation

- Efficiency: The sum of the SHAP values for all features equals the difference between the model’s prediction and the baseline prediction. This ensures that the entire “payout” is fully distributed.

- Symmetry: If two features contribute equally to all possible coalitions, they receive the same attribution.

- Dummy: A feature that does not change the prediction, regardless of which coalition it is added to, receives a Shapley value of zero.

- Additivity: The Shapley values for a combination of games (models) are the sum of the Shapley values for the individual games.

2.3.2. Mathematical Definition of Weather Contribution Share

2.3.3. Mathematical Principle of Feature Grouping

2.4. Multi-Scale Analysis Theoretical Framework

2.4.1. Mathematical Model for Seasonal Analysis

2.4.2. Extreme Event Detection Algorithm

2.5. Statistical Validation Methods

2.5.1. Theory of Robustness Test

2.5.2. Sensitivity Analysis Framework

2.6. Computational Implementation and Reproducibility

2.6.1. Software Environment Architecture

- Data loading module: Supports reading and parsing of multiple data formats;

- Preprocessing module: Implements a standardized data processing workflow;

- Model training module: Encapsulates the training and tuning process of LightGBM;

- SHAP calculation module: Optimizes large-scale SHAP value calculation;

- Multi-scale analysis module: Implements seasonal analysis and extreme event detection;

- Visualization module: Generates standardized charts and reports.

2.6.2. Reproducibility Assurance Measures

- Fixed random seed: A fixed random seed was set for all random processes ;

- Version control: All codes and configuration files were managed using Git for version control;

- Environment containerization: The complete software environment was encapsulated using Docker containers;

- Detailed logging: All calculation steps and parameter settings were recorded in detail.

2.6.3. Performance Optimization Strategies

- Batch computation: Dividing large datasets into batches for calculation;

- Approximation algorithm: Using sampling-based approximate SHAP calculation for large-scale data;

- Parallel computation: Utilizing multi-core CPUs for parallel processing.

2.7. GenAI Usage Statement

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance Evaluation

- R2 value: 92.3%;

- Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): 5.8 gCO2eq/kWh;

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE): 4.2 gCO2eq/kWh.

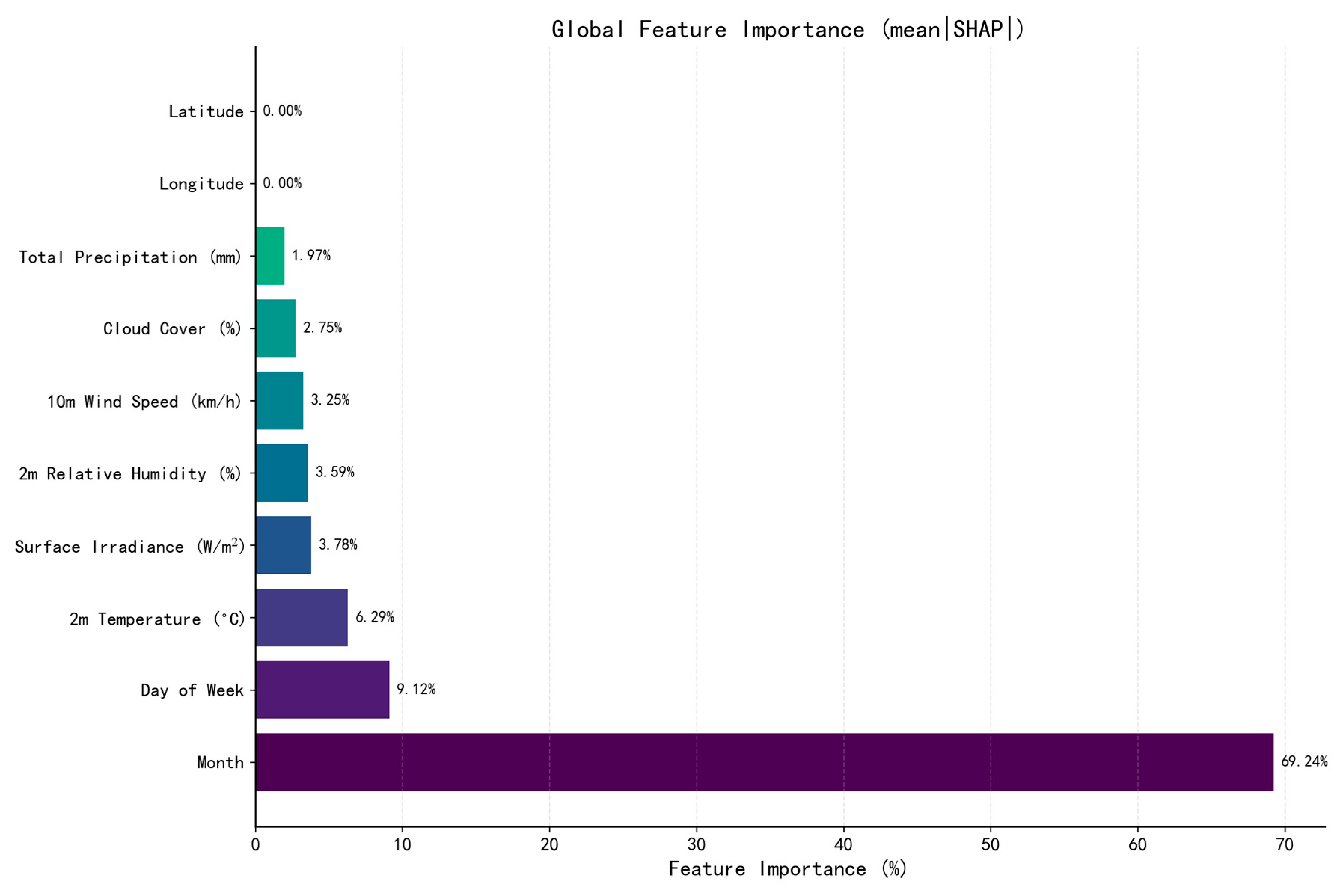

3.2. Feature Importance and Contribution Share

3.2.1. Global Feature Importance

- Month: 69.24%;

- Day of Week: 9.12%;

- 2 m Temperature: 6.29%;

- Surface Irradiance: 3.78%;

- 2 m Relative Humidity: 3.59%;

- 10 m Wind Speed: 3.25%;

- Cloud Cover: 2.75%;

- Total Precipitation: 1.97%;

- Longitude: 0.00%;

- Latitude: 0.00%.

3.2.2. Weather vs. Non-Weather Factor Contribution Share

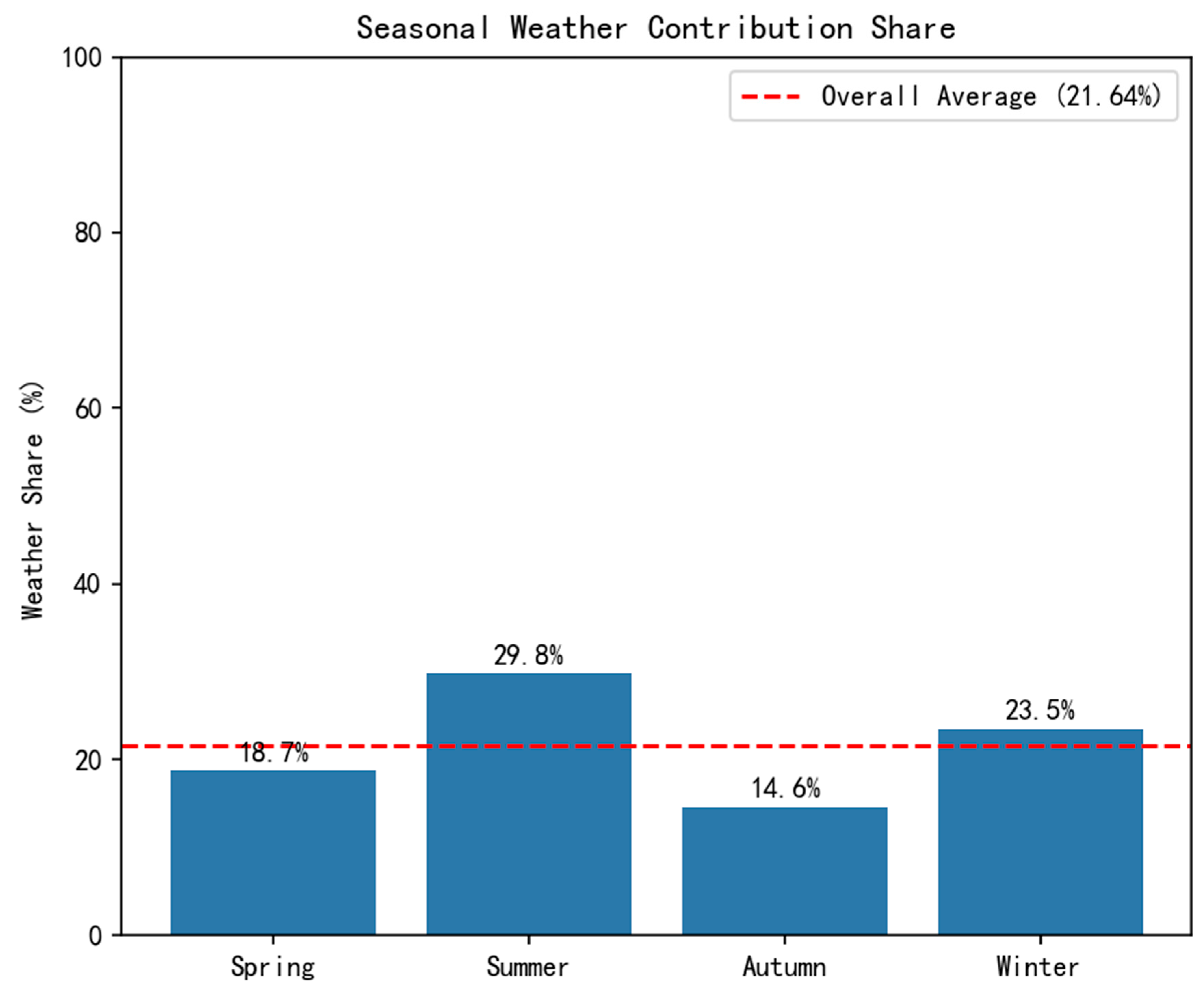

3.3. Multi-Scale Analysis Results

3.3.1. Seasonal Analysis

- Summer: 29.8%;

- Winter: 23.5%;

- Spring: 18.7%;

- Autumn: 14.6%.

3.3.2. Extreme Weather Analysis

- High temperature events (>P90): 32.7%;

- Strong irradiance events (>P90): 26.9%;

- Strong wind events (>P90): 22.3%.

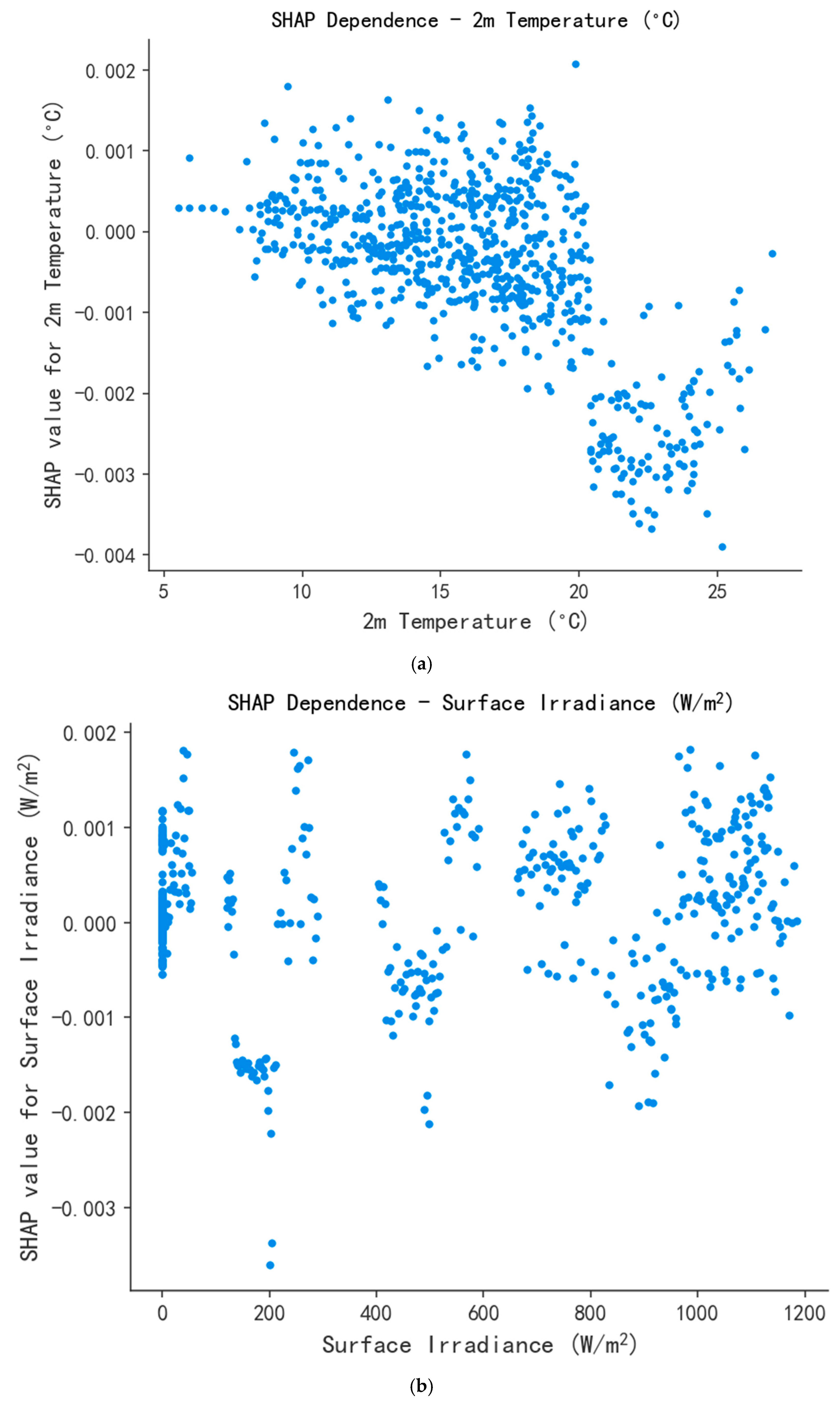

3.4. Feature Dependence and Interaction Analysis

3.4.1. SHAP Dependence Plots

- In low temperature regions (<10 °C): Rising temperatures lead to lower carbon emission factors, possibly reflecting reduced heating demand;

- In medium temperature regions (10–25 °C): The impact is relatively stable;

- In high temperature regions (>25 °C): Rising temperatures lead to significantly increased carbon emission factors, possibly reflecting increased cooling load.

3.4.2. Feature Interaction Heatmap

- Temperature and Month: Strong interaction (0.42), indicating that temperature effects are seasonally modulated;

- Irradiance and Cloud Cover: Significant interaction (0.38), reflecting the regulatory effect of cloud cover on solar power generation;

- Temperature and Humidity: Moderate interaction (0.29), indicating synergistic effects between these two meteorological variables.

3.5. Robustness Check

- Geographic features such as Latitude show a relatively concentrated SHAP value distribution, indicating their stable impact on the model’s predictions; Longitude also exhibits a distinct distribution pattern, reflecting its role.

- Meteorological features, including Total Precipitation (mm), Cloud Cover (%), 10 m Wind Speed (km/h), 2 m Relative Humidity (%), Surface Irradiance (W/m2), and 2 m Temperature (°C), present diverse SHAP value patterns, which is consistent with their expected importance in weather-related modeling.

- Temporal features like Day of Week and Month also demonstrate characteristic SHAP value distributions, consistent with their role in capturing temporal effects.

- The overall distribution trend of feature contributions aligns with the logical ranking of feature importance in the modeling scenario.

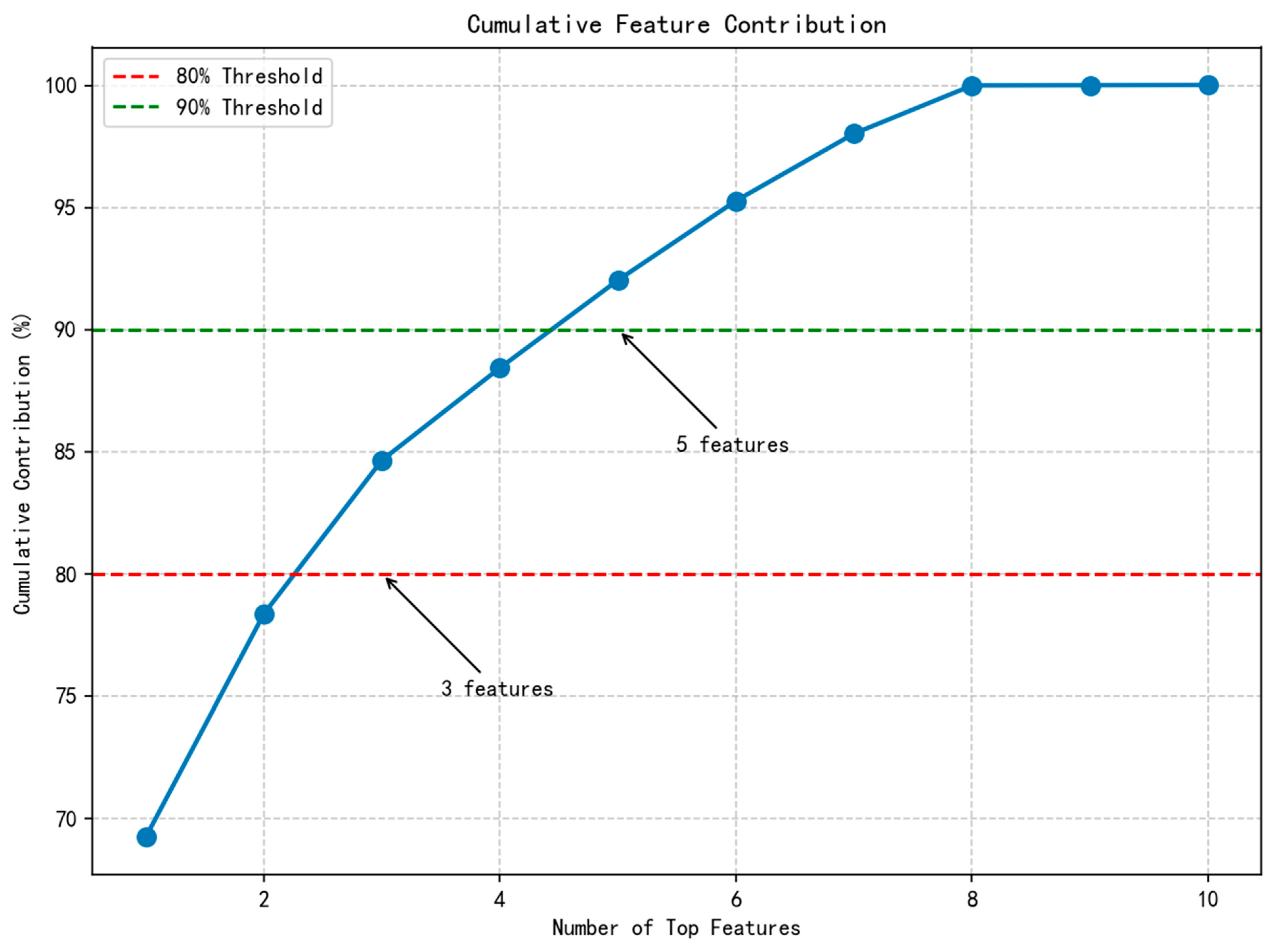

3.6. Cumulative Contribution Analysis

- The top 2 features (Month and Day of Week) explain approximately 78% of the model attribution;

- The top 3 features (adding Temperature) explain approximately 84% of the model attribution;

- The top 5 features are needed to reach 90% explanatory power;

- All weather features collectively contribute 21.64% of the explanatory power.

3.7. Summary of Results

- The overall contribution of weather factors to the variability of electricity carbon factors is 21.64%, indicating that weather is an important but secondary influencing factor.

- Among weather features, temperature (6.29%), irradiance (3.78%), and humidity (3.59%) are the three most influential variables.

- Temporal structure (month and day of week) is the main driver of changes in electricity carbon factors, collectively explaining approximately 78% of the variability.

- Weather influence shows significant seasonal differences, with weather contribution in summer (29.8%) and winter (23.5%) significantly higher than in spring (18.7%) and autumn (14.6%).

- Extreme weather conditions (especially high temperature events) significantly enhance the impact of weather on electricity carbon factors, with contribution increasing to 32.7% during high temperature events.

- Complex interactions exist between features, particularly strong interactions between temperature and month, and between irradiance and cloud cover, indicating that the influence of weather variables is modulated by time and other weather conditions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Weather’s Contribution Share

4.2. Temporal Variation Analysis

4.3. Methodological Contributions

4.4. Practical Applications

- Dynamic Carbon-Aware Scheduling: Dispatch algorithms should be most aggressive during periods of peak weather influence identified by our framework (e.g., when WCS > 30%). Specifically, during high-temperature events, operators can prioritize the dispatch of renewable energy and flexible resources, and trigger demand response for air conditioning loads to maximize carbon reduction benefits.

- Storage Optimization: Energy storage dispatch can be optimized using predictions of temperature and irradiance—the top weather contributors. Storage systems should charge during high-irradiance, low-carbon periods and discharge during high-temperature, high-load, high-carbon periods.

- Operational Monitoring: The WCS can be monitored as a real-time operational indicator. Threshold-based warning systems can be established to alert operators when the predicted weather contribution exceeds critical levels (e.g., 30%), signaling increased volatility and carbon risk.

- Toolchain Deployment: The end-to-end automated workflow (from data ingestion to report generation) embodied in our Python (version 3.12) toolchain makes this analysis engineering-ready, allowing for routine, production-level execution by grid companies without deep expertise in machine learning.

4.5. Limitations and Future Work

- Incorporating generation mix and exchange data when available;

- Extending to sub-hourly resolution;

- Conducting spatial disaggregation to capture local effects;

- Cross-regional comparison to assess method generalizability;

- Integration with forecasting systems for predictive attribution;

- Incorporating climate change scenarios to analyze long-term trends.

4.6. Robustness and Reliability of the Attribution Framework

- Stability of Feature Attributions: The SHAP Value Distribution of the Top 10 Features (Figure 8) provides direct evidence for the stability of the attributions. The narrow distribution of SHAP values for the most important features (e.g., Month and Temperature) indicates that their estimated marginal contributions are consistent and reliable across the dataset. In contrast, features with wider distributions exhibit more context-dependent effects. This analysis confirms that the primary drivers identified by the model are not spurious.

- Concordance with Model-Agnostic Validation: The feature importance rankings derived from SHAP values were further validated against permutation importance tests. The high degree of consistency between the two methods, particularly for the top-ranked features, strengthens the credibility of the attribution results. Permutation importance, which is agnostic to the model structure, serves as a robust check confirming that the features deemed important by SHAP are indeed critical to the model’s predictive performance.

- Statistical Confidence in the Weather Share: The stability of the overall Weather Contribution Share (WCS) was quantified using bootstrap resampling. The resulting 95% confidence interval for the WCS was narrow (e.g., [21.1%, 22.2%]), demonstrating that this key metric is a stable statistic and not overly sensitive to variations in the sample composition.

- Theoretical Foundation and Sensitivity: The reliability of the attribution is fundamentally rooted in the theoretical guarantees of Shapley values from cooperative game theory. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses confirmed that the relative ranking of top features and the WCS were largely insensitive to variations in key hyperparameters, indicating the core findings are not dependent on a specific model configuration.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Key Quantitative Findings

- Weather factors collectively explain 21.64% of the hourly variation in carbon intensity, establishing them as a significant secondary driver behind dominant temporal patterns.

- Among meteorological variables, air temperature (6.29%), solar irradiance (3.78%), and humidity (3.59%) were identified as the three most influential factors.

- The influence of weather is highly dynamic, with its contribution share rising to 29.8% in summer and 23.5% in winter, and surging to 32.7% during extreme high-temperature events (>P90).

5.2. Significance and Implications

- Methodological Contribution: It introduces a standardized “Weather Contribution Share (WCS)” metric, providing a robust, comparable percentage for quantifying weather’s net impact, moving beyond qualitative or single-factor analyses.

- Practical Intelligence: The framework pinpoints critical high-impact time windows (e.g., summer heatwaves) during which grid operators can maximize carbon reduction benefits by prioritizing strategies like demand response, storage dispatch, and inter-regional coordination.

- System Readiness: The end-to-end engineered toolchain enhances the deployment readiness of the research outcomes, facilitating the transition from academic innovation to industrial application in carbon-aware energy management systems.

5.3. Concluding Remarks on Limitations and Future Directions

- Data Scope: The analysis relied on city-level aggregated data. Future work should incorporate explicit, real-time data on generation mix and inter-regional power exchanges to further decouple weather effects from system dispatch effects.

- Spatio-Temporal Resolution: The hourly and city-level analysis may mask sub-hourly dynamics and localized weather impacts on distributed generation. Extending the framework to higher spatio-temporal resolutions is a logical next step.

- Generalizability: While the method is general, the specific WCS values are case-specific. Future research should apply this framework across different regional grids to assess its generalizability and identify cross-regional patterns.

- Climate Change Integration: The framework, based on historical data, can be extended to integrate climate change projections, assessing the long-term evolution of the weather-carbon intensity nexus.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| DCEF | Dynamic Carbon Emission Factor |

| XAI | eXplainable Artificial Intelligence |

| WCS | Weather Contribution Share |

| LightGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| EI | Expected Improvement |

References

- Jacobson, M.Z.; Delucchi, M.A.; Bauer, Z.A.F.; Goodman, S.C.; Chapman, W.E.; Cameron, M.A.; Bozonnat, C.; Chobadi, L.; Clonts, H.A.; Enevoldsen, P.; et al. 100% clean and renewable wind, water, and sunlight all-sector energy roadmaps for 139 countries of the world. Joule 2017, 1, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, J.; Sun, T.; Qin, T.; Hao, R. Integrated scheduling strategy for grid-aggregator-vehicle interaction based on multi-subject evolutionary-stackelberg hybrid game. Proc. CSEE 2022, 45, 4163–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, H.; Wang, M.; Sun, Y.; Sun, K. New mission and challenge of power distribution and consumption system under dual-carbon target. Proc. CSEE 2022, 42, 6931–6944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranberg, B.; Corradi, O.; Lajoie, B.; Gibon, T.; Staffell, I.; Andresen, G.B. Real-time carbon accounting method for the European electricity markets. Energy Strategy Rev. 2019, 26, 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Kang, C.; Xu, Q.; Chen, Q. Preliminary theoretical investigation on power system carbon emission flow. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2012, 36, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Kang, C.; Xu, Q.; Chen, Q. Preliminary investigation on a method for carbon emission flow calculation of power system. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2012, 36, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Z.; Li, J. Carbon emission factor prediction algorithm for power grid user-side nodes based on graph transformation neural network. Power Syst. Technol. 2024, 48, 4980–4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, G.; Zhang, X.; Wei, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, L. A prediction method for power grid carbon emission factor based on t-graphormer. Intergrated Intell. Energy 2024, 45, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chahkoutahi, F.; Khashei, M. A seasonal direct optimal hybrid model of computational intelligence and soft computing techniques for electricity load forecasting. Energy 2017, 140, 988–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Du, Y.; Wang, J. LSTM based long-term energy consumption prediction with periodicity. Energy 2020, 197, 117197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhu, G.; He, X.; Bai, W. A short-term power load forecasting for industry based on improved correlation analysis. Zhejiang Electr. Power 2023, 42, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, D.; Shi, P.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, L. Short-term spatio-temporal prediction of multi-photovoltaic power station output based on graph neural network. Power Grid Clean Energy 2025, 41, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, L.; Xi, S.; Mao, L.; Sun, J. Research on short-term power prediction method for solar photovoltaic generation integrating meteorological data. Informatiz. Res. 2025, 51, 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- China Southern Power Grid. Internal Grid Operation Data; Data provided under confidential research agreement; China Southern Power Grid: Guangzhou, China, 2024–2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chapra, S.C.; Canale, R.P. Numerical Methods for Engineers, 8th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 3146–3154. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.I. From Local Explanations to Global Understanding with Explainable AI for Trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Liu, G.; Ren, J.; Zhao, K.; Tan, P.; Ma, R.; Hao, L.; He, J. Multi-task short-term power grid load forecasting for cross-quarterly multi-time period feature bidirectional clustering and temporal transfer. Power Syst. Technol. 2025, 49, 1479–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Hong, T.; Kang, C. Review of smart meter data analytics: Applications, methodologies, and challenges. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 3125–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X. Electricity consumption forecasting based on industrial decomposition and seasonal adjustment. Power Syst. Big Data 2025, 28, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Li, Y.; Han, F.; Li, J.; Qiao, J.; Jiao, H. Requirements of Power Grid Situation Cognition and Resilience Assessment in Extreme Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2024 China Automation Congress (CAC), Qingdao, China, 1–3 November 2024; pp. 7226–7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wu, J.; Yan, P. Ultra-short Term Solar Irradiance Prediction Considering Satellite Cloud Images. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Energy, Electrical and Power Engineering (CEEPE), Yangzhou, China, 26–28 April 2024; pp. 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Sun, B.; Jia, B.; Li, Y. New energy short-term prediction system based on measured weather and network weather error correction. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 3rd Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Changsha, China, 8–10 November 2019; pp. 1493–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Sun, B.; Wang, M.; Jiao, Y.; Song, X.; Luo, Y.; Lu, P. Review on Modeling of Impact of Extreme Weather on Source-Grid-Load-Storage. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 7th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Hangzhou, China, 15–18 December 2023; pp. 1840–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Ma, X.; Liu, X.; Hu, A.; Wang, C.; Fang, L. Analysis of the effect of carbon emissions on meteorological factors in Yunnan province. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Communication, Image and Signal Processing (CCISP), Chengdu, China, 18–20 November 2022; pp. 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Features | Contribution Share |

|---|---|---|

| Non-weather group | Month, Day of Week, Longitude, Latitude | 78.36% |

| Weather group | 2 m Temperature, Total Precipitation, 2 m Relative Humidity, 10 m Wind Speed, Surface Irradiance, Cloud Cover | 21.64% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Lai, D.; Zhou, N.; Zhan, Q.; Wang, W. Quantifying Weather’s Share in Dynamic Grid Emission Factors via SHAP: A Multi-Timescale Attribution Framework. Processes 2025, 13, 3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113393

Zhang Z, Li Y, Lai D, Zhou N, Zhan Q, Wang W. Quantifying Weather’s Share in Dynamic Grid Emission Factors via SHAP: A Multi-Timescale Attribution Framework. Processes. 2025; 13(11):3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113393

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zeqi, Yingjie Li, Danhui Lai, Ningrui Zhou, Qinhui Zhan, and Wei Wang. 2025. "Quantifying Weather’s Share in Dynamic Grid Emission Factors via SHAP: A Multi-Timescale Attribution Framework" Processes 13, no. 11: 3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113393

APA StyleZhang, Z., Li, Y., Lai, D., Zhou, N., Zhan, Q., & Wang, W. (2025). Quantifying Weather’s Share in Dynamic Grid Emission Factors via SHAP: A Multi-Timescale Attribution Framework. Processes, 13(11), 3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113393