Combining Fuzzy Cognitive Maps and Metaheuristic Algorithms to Predict Preeclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. ML Models for Predicting PE

2.2. ML Models for Predicting IUGR

2.3. FCM-Based Models for Predicting PE and IUGR

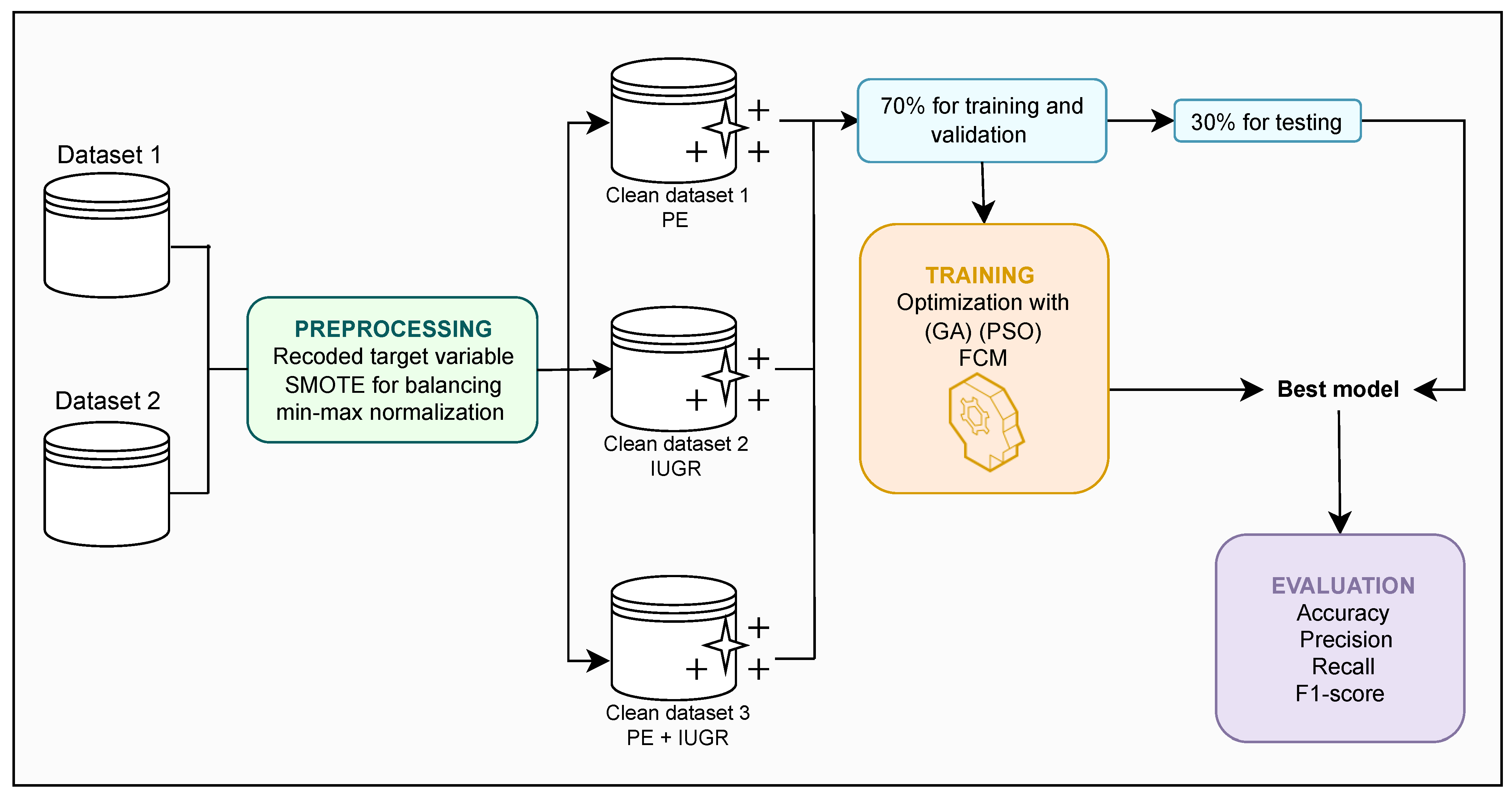

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Datasets

3.1.1. Description of Dataset 1

3.1.2. Description of Dataset 2

3.1.3. Description of the Dataset 3

3.2. Data Preprocessing

3.3. Model Construction

3.3.1. Fuzzy Sets

3.3.2. FCM

3.3.3. FCM-PSO

| Algorithm 1: FCM-PSO |

|

3.4. FCM-GA

| Algorithm 2: FCM-GA |

|

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

3.5.1. Accuracy

3.5.2. Precision

3.5.3. Recall

3.5.4. F1-Score

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Predictive Performance of the Developed Models

4.1.1. Predictive Performance of the Models for PE

4.1.2. Predictive Performance of Models for IUGR

4.1.3. Predictive Performance of Models for PE + IUGR

4.2. Analysis of the Relationships of the Best FCM Model in Each Dataset

4.2.1. FCM-PSO Relationships in the Prediction of PE

4.2.2. Relationships of FCM-GA in the Prediction of IUGR

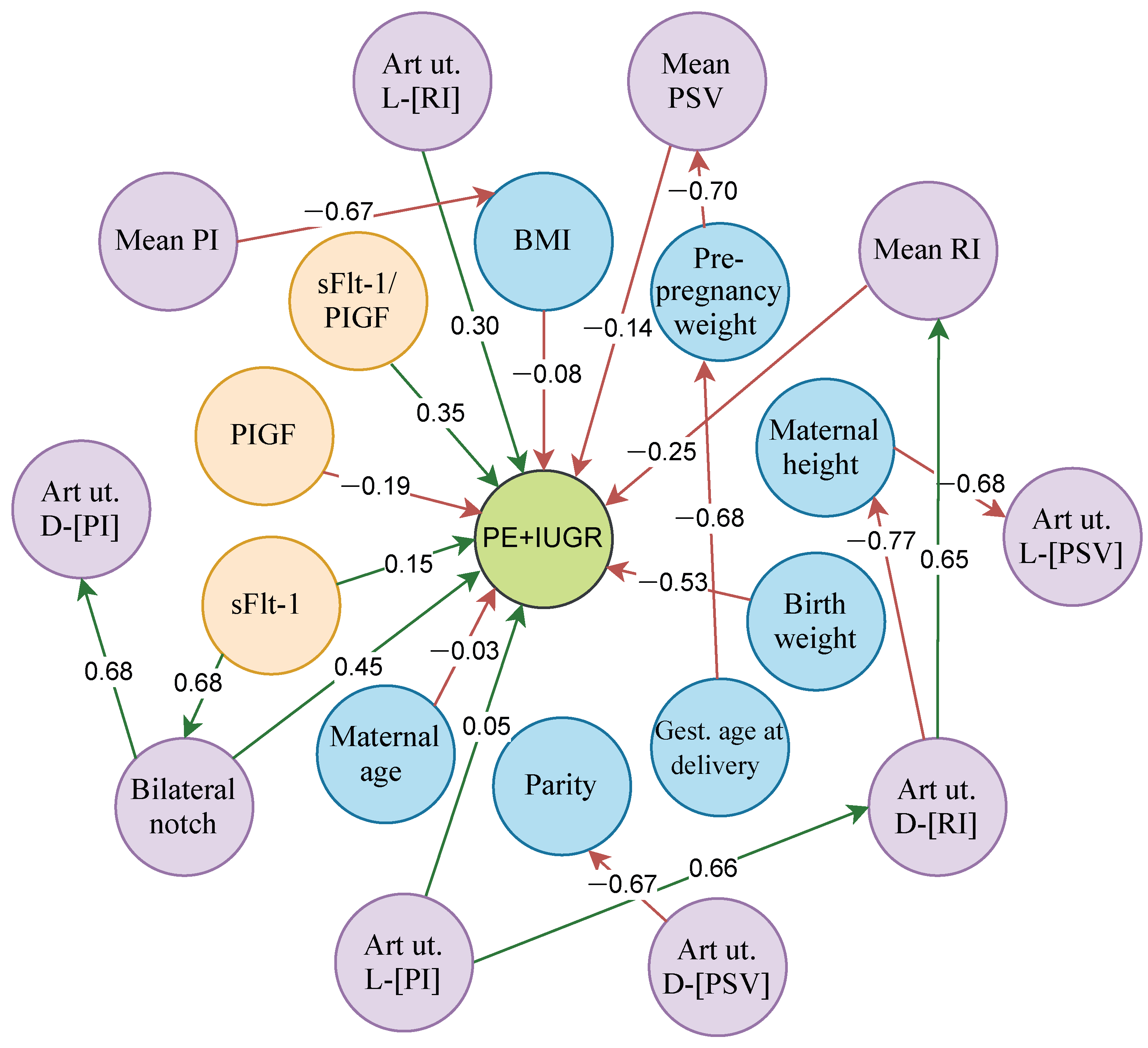

4.2.3. Relationships of FCM-PSO in the Prediction of PE + IUGR

4.3. Comparison with Other ML Models

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Umapathy, A.; Chamley, L.W.; James, J.L. Reconciling the distinct roles of angiogenic/anti-angiogenic factors in the placenta and maternal circulation of normal and pathological pregnancies. Angiogenesis 2020, 23, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herraiz, I.; Llurba, E.; Verlohren, S.; Galindo, A.; on behalf of the Spanish Group for the Study of Angiogenic Markers in Preeclampsia. Update on the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Preeclampsia with the Aid of the sFlt-1/PlGF Ratio in Singleton Pregnancies. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2018, 43, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez Zegarra, R.; Ghi, T.; Lees, C. Does the use of angiogenic biomarkers for the management of preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction improve outcomes?: Challenging the current status quo. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 300, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, U.; Olsson, M.; Kristensen, K.; Åkerström, B.; Hansson, S. Review: Biochemical markers to predict preeclampsia. Placenta 2012, 33, S42–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoots, M.H.; Bourgonje, M.F.; Bourgonje, A.R.; Prins, J.R.; Van Hoorn, E.G.; Abdulle, A.E.; Muller Kobold, A.C.; Van Der Heide, M.; Hillebrands, J.L.; Van Goor, H.; et al. Oxidative stress biomarkers in fetal growth restriction with and without preeclampsia. Placenta 2021, 115, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomimatsu, T.; Mimura, K.; Matsuzaki, S.; Endo, M.; Kumasawa, K.; Kimura, T. Preeclampsia: Maternal Systemic Vascular Disorder Caused by Generalized Endothelial Dysfunction Due to Placental Antiangiogenic Factors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, L.; De Gier, S.; Vogelvang, T.E.; Veerbeek, J.H.; Franx, A.; Van Rijn, B.B.; Nikkels, P.G. Prevalence of placental bed spiral artery pathology in preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction: A prospective cohort study. Placenta 2024, 156, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACOG. Fetal Growth Restriction: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 227. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 137, e16–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, A.; Neves, E.; Guimarães, J.; Braga, J.; Vasconcelos, C. Th17 / Treg ratio: A prospective study in a group of pregnant women with preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2023, 159, 104122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, R.; Devanesan, B.P.; Srijana; Sreedevi, N. Prevalence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, associated factors and pregnancy complications in a primigravida population. Gynecol. Obstet. Clin. Med. 2023, 3, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerovasili, E.; Sarantaki, A.; Bothou, A.; Deltsidou, A.; Dimitrakopoulou, A.; Diamanti, A. The role of vitamin D deficiency in placental dysfunction: A systematic review. Metab. Open 2025, 25, 100350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Wu, B.; Chen, X.; Wei, W.; Yao, X. Diagnostic biomolecules and combination therapy for pre-eclampsia. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2022, 20, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueras, F.; Caradeux, J.; Crispi, F.; Eixarch, E.; Peguero, A.; Gratacos, E. Diagnosis and surveillance of late-onset fetal growth restriction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, S790–S802.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkiewicz, J.; Darmochwał-Kolarz, D.A. Biomarkers for Early Prediction and Management of Preeclampsia: A Comprehensive Review. Med. Sci. Monit. 2024, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, M.; Peker, S. Preeclampsia prediction via machine learning: A systematic literature review. Health Syst. 2024, 14, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljameel, S.S.; Alzahrani, M.; Almusharraf, R.; Altukhais, M.; Alshaia, S.; Sahlouli, H.; Aslam, N.; Khan, I.U.; Alabbad, D.A.; Alsumayt, A. Prediction of Preeclampsia Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models: A Review. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2023, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, I.D.; Papandrianos, N.I.; Papathanasiou, N.D.; Papageorgiou, E.I. Fuzzy Cognitive Map Applications in Medicine over the Last Two Decades: A Review Study. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiruneh, S.A.; Vu, T.T.T.; Rolnik, D.L.; Teede, H.J.; Enticott, J. Machine Learning Algorithms Versus Classical Regression Models in Pre-Eclampsia Prediction: A Systematic Review. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2024, 26, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjbar, A.; Montazeri, F.; Ghamsari, S.R.; Mehrnoush, V.; Roozbeh, N.; Darsareh, F. Machine learning models for predicting preeclampsia: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE. Hypertension in pregnancy: Diagnosis and management. Hypertension in Pregnancy. 2019. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133 (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- ACOG. Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 222. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 135, e237–e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Luo, Y. Preeclampsia and its prediction: Traditional versus contemporary predictive methods. J.-Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2024, 37, 2388171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.; Agrawal, N.; Prasad, S.; Talwar, S.; Khatuja, R.; Jain, S.; Sehgal, N.P.; Malik, N.; Khatuja, J.; Madan, N. Prediction of Preeclampsia Using Machine Learning: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiruneh, S.A.; Rolnik, D.L.; Teede, H.J.; Enticott, J. Prediction of pre-eclampsia with machine learning approaches: Leveraging important information from routinely collected data. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2024, 192, 105645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansbacher-Feldman, Z.; Syngelaki, A.; Meiri, H.; Cirkin, R.; Nicolaides, K.H.; Louzoun, Y. Machine-learning-based prediction of pre-eclampsia using first-trimester maternal characteristics and biomarkers. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 60, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhee, J.H.; Lee, S.; Park, Y.; Lee, S.E.; Kim, Y.A.; Kang, S.W.; Kwon, J.Y.; Park, J.T. Prediction model development of late-onset preeclampsia using machine learning-based methods. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Duan, H.; Zhao, G.; Zheng, M.; Hu, Y. Prediction model of preeclampsia using machine learning based methods: A population based cohort study in China. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1345573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rescinito, R.; Ratti, M.; Payedimarri, A.B.; Panella, M. Prediction Models for Intrauterine Growth Restriction Using Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Lin, H.; Shao, M.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, D. Integrating SHAP analysis with machine learning to predict postpartum hemorrhage in vaginal births. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2025, 25, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgani, E.; Stylios, C.D.; Manis, G.; Georgopoulos, V.C. Timed Fuzzy Cognitive Maps for Supporting Obstetricians’ Decisions. In Proceedings of the 6th European Conference of the International Federation for Medical and Biological Engineering; Dubrovnik, Croatia, 7–11 September 2014; Lacković, I., Vasic, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; Volume 45, pp. 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, I.; Paredes-Solís, S.; Loutfi, D.; Dion, A.; Cockcroft, A.; Andersson, N. Fuzzy cognitive mapping and soft models of indigenous knowledge on maternal health in Guerrero, Mexico. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campero-Jurado, I.; Robles-Camarillo, D.; Ruiz-Vanoye, J.A.; Xicoténcatl-Pérez, J.M.; Díaz-Parra, O.; Salgado-Ramírez, J.C.; Marroquín-Gutiérrez, F.; Ramos-Fernández, J.C. Fuzzy Logic Prediction of Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy Using the Takagi–Sugeno and C-Means Algorithms. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazate Chuga, Z.R.; Chamorro Nazate, J.V.; Guerrero Morán, P.E. Modeling risk factors in preeclampsia for late pregnancies using fuzzy cognitive maps. Salud Cienc. Tecnol.-Ser. Conf. 2024, 3, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos, W.; García, R.; Aguilar, J. Multistage Training of Fuzzy Cognitive Maps to Predict Preeclampsia and Fetal Growth Restriction. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 136779–136792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, S.; Akram, M. Medical decision support systems based on Fuzzy Cognitive Maps. Int. J. Biomath. 2019, 12, 1950069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabjan-Vodusek, V.; Kumer, K.; Osredkar, J.; Verdenik, I.; Gersak, K.; Premru-Srsen, T. Correlation between uterine artery Doppler and the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio in different phenotypes of placental dysfunction. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2019, 38, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Chen, L.; Meng, X.; Chen, Y. Risk factors and foetal growth restriction associated with expectant treatment of early-onset preeclampsia. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 3249–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, C.; Öztayşi, B.; Onar, S.Ç. A Comprehensive Literature Review of 50 Years of Fuzzy Set Theory. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2016, 9, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poczeta, K.; Papageorgiou, E.I.; Gerogiannis, V.C. Fuzzy Cognitive Maps Optimization for Decision Making and Prediction. Mathematics 2020, 8, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosko, B. Fuzzy cognitive maps. Int. J.-Man-Mach. Stud. 1986, 24, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the ICNN’95—International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Raja, J.B.; Pandian, S.C. PSO-FCM based data mining model to predict diabetic disease. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 196, 105659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obbu, B.S.; Jabeen, Z. Integrated Fuzzy Cognitive Map and Chaotic Particle Swarm Optimization for Risk Assessment of Ischemic Stroke. Int. J. Comput. Exp. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmeron, J.L.; Rahimi, S.A.; Navali, A.M.; Sadeghpour, A. Medical diagnosis of Rheumatoid Arthritis using data driven PSO–FCM with scarce datasets. Neurocomputing 2017, 232, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, L.M. Theory of genetic algorithms. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2001, 259, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhijawi, B.; Awajan, A. Genetic algorithms: Theory, genetic operators, solutions, and applications. Evol. Intell. 2024, 17, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, J. Learning of fuzzy cognitive maps using a niching-based multi-modal multi-agent genetic algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 74, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stach, W.; Kurgan, L.; Pedrycz, W.; Reformat, M. Genetic learning of fuzzy cognitive maps. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2005, 153, 371–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazoglou, G.; Biskas, P. Review and Comparison of Genetic Algorithm and Particle Swarm Optimization in the Optimal Power Flow Problem. Energies 2023, 16, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wihartiko, F.D.; Wijayanti, H.; Virgantari, F. Performance comparison of genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization for model integer programming bus timetabling problem. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 332, p. 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, F.M.; Ariffin, W.N.M.; Jusoh, M.S.; Putri, E.P. A Review of Genetic Algorithm: Operations and Applications. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 40, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Shinar, S.; Cerdeira, A.S.; Redman, C.; Vatish, M. Predictive Performance of PlGF (Placental Growth Factor) for Screening Preeclampsia in Asymptomatic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hypertension 2019, 74, 1124–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, L.; O’Gorman, N.; Palmer, K.R.; Da Silva Costa, F.; Rolnik, D.L. Perspectives on the Use of Placental Growth Factor (PlGF) in the Prediction and Diagnosis of Pre-Eclampsia: Recent Insights and Future Steps. Int. J. Women’s Health 2023, 15, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardini, V.; Santagati, A.A.; Marelli, E.; Casati, M.; Vergani, P.; Cantarutti, A.; Locatelli, A. Decoding placental dysfunction with a new angiogenic classification of PlGF and sFlt-1. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2025, 312, 114539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lei, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Ni, M.; He, B.; Gao, J.; Zheng, P.; Xie, X.; He, C.; Yang, X.; et al. Gestational weight gain of multiparas and risk of primary preeclampsia: A retrospective cohort study in Shanghai. Clin. Hypertens. 2023, 29, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Yuan, P.; Chen, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, M.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, H.; et al. Risk of preeclampsia by gestational weight gain in women with varied prepregnancy BMI: A retrospective cohort study. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 967102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; He, B.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, T.; Gao, Y.; Yao, B. Utility of uterine artery Doppler ultrasound imaging in predicting preeclampsia during pregnancy: A meta-analysis. Med. Ultrason. 2024, 26, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Običan, S.G.; Odibo, L.; Tuuli, M.G.; Rodriguez, A.; Odibo, A.O. Third trimester uterine artery Doppler indices as predictors of preeclampsia and neonatal small for gestational age. J.-Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 33, 3484–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, M.A.; Palmer, K.R.; Hodges, R.J.; Costa, F.D.S.; Rolnik, D.L. Uterine Artery Doppler in Screening for Preeclampsia and Fetal Growth Restriction. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obs./RBGO Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 40, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, C.; Arab, S.; Czuzoj-Shulman, N.; Abenhaim, H.A. Influence of intrauterine growth restriction on caesarean delivery risk among preterm pregnancies undergoing induction of labor for hypertensive disease. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2019, 45, 1860–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinton, A.; Lemaire Tomzack, C.; Merckelbagh, H.; Goffinet, F. Induction of labour with unfavourable local conditions for suspected fetal growth restriction after 36 weeks of gestation: Factors associated with the risk of caesarean. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 50, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubrano, C.; Taricco, E.; Coco, C.; Di Domenico, F.; Mandò, C.; Cetin, I. Perinatal and Neonatal Outcomes in Fetal Growth Restriction and Small for Gestational Age. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aynaoğlu Yıldız, G.; Topdağı Yılmaz, E.P. The association between protein levels in 24-hour urine samples and maternal and neonatal outcomes of pregnant women with preeclampsia. J.-Turk.-Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2022, 23, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour Ghanaei, M.; Amir Afzali, S.; Morady, A.; Mansour Ghanaie, R.; Asghari Ghalebin, S.M.; Rafiei, E.; Kabodmehri, R. Intrauterine Growth Restriction with and without Pre-Eclampsia: Pregnancy Outcome and Placental Findings. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Cancer Res. 2022, 7, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuhaytib, F.A.; AlKishi, N.A.; Alyousif, Z.M. Early Onset Preeclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction: A Case Report. Cureus 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Sun, W.; Deswal, A.; De Lemos, J.A.; McEvoy, J.W.; Hoogeveen, R.C.; Matsushita, K.; Aguilar, D.; Bozkurt, B.; Virani, S.S.; et al. Association of NT-ProBNP, Blood Pressure, and Cardiovascular Events. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yang, X. A Review of Roles of Uterine Artery Doppler in Pregnancy Complications. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 813343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, M.Y.; Syngelaki, A.; Poon, L.C.; Rolnik, D.L.; O’Gorman, N.; Delgado, J.L.; Akolekar, R.; Konstantinidou, L.; Tsavdaridou, M.; Galeva, S.; et al. Screening for pre-eclampsia by maternal factors and biomarkers at 11–13 weeks’ gestation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 52, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, M.; Velandia, D.; Mayeta-Revilla, L.; Bertini, A.; Querales, M.; Pardo, F.; Salas, R. An Explainable Fuzzy Framework for Assessing Preeclampsia Classification. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Yang, X.; Chen, G.; Ding, Y.; Shi, M.; Sun, L.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, T.; Yan, R.; et al. Development of a prediction model on preeclampsia using machine learning-based method: A retrospective cohort study in China. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 896969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilache, I.A.; Scripcariu, I.S.; Doroftei, B.; Bernad, R.L.; Cărăuleanu, A.; Socolov, D.; Melinte-Popescu, A.S.; Vicoveanu, P.; Harabor, V.; Mihalceanu, E.; et al. Prediction of Intrauterine Growth Restriction and Preeclampsia Using Machine Learning-Based Algorithms: A Prospective Study. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Jemes, L.; Oprescu, A.M.; Chimenea-Toscano, Á; García-Díaz, L.; Romero-Ternero, M.D. Machine Learning to Predict Pre-Eclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction in Pregnant Women. Electronics 2022, 11, 3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufriyana, H.; Wu, Y.W.; Su, E.C.Y. Prediction of Preeclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction: Development of Machine Learning Models on a Prospective Cohort. JMIR Med. Inform. 2020, 8, e15411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, H.V.; Long, C.K.; Khanh, P.H.; Trung, H.Q. A Fuzzy Knowledge Graph Pairs-Based Application for Classification in Decision Making: Case Study of Preeclampsia Signs. Information 2023, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Variable | Variable | Concept | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal and fetal variables | Maternal age (years) | C1 | Time lived by the mother. |

| Pre-pregnancy weight (kg) | C2 | Body weight in kg before becoming pregnant. | |

| Maternal height (m) | C3 | Measurement of the mother’s height. | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | C4 | Weight and height ratio for calculating body mass. | |

| Doppler-related features | Art ut. D-resistance index [RI] | C5 | Measures resistance to diastolic blood flow in the right uterine artery. |

| Art ut. D-pulsatility index [PI] | C6 | Assess resistance to blood flow in the right uterine artery using mean, diastolic, and systolic velocity. | |

| Art ut. D-Peak Systolic Velocity [PSV] | C7 | Maximum velocity reached during systole in the right uterine artery. | |

| Art ut. L-resistance index [RI] | C8 | Measures resistance to diastolic blood flow in the left uterine artery. | |

| Art ut. L-pulsatility index [PI] | C9 | Assess resistance to blood flow in the left uterine artery using mean, diastolic, and systolic velocity. | |

| Art ut. L-Peak Systolic Velocity [PSV] | C10 | Maximum velocity reached during systole in the left uterine artery. | |

| Mean RI | C11 | Average value of the right and left resistance index [RI]. | |

| Mean PI | C12 | Average value of the right and left pulsatility index [PI]. | |

| Mean PSV | C13 | Average value of the right and left peak systolic velocity [PSV]. | |

| Bilateral notch | C14 | Presence or absence of notch in the flow waveform of the uterine arteries. | |

| Maternal and fetal variables | Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | C15 | Weeks between the first day of the mother’s last menstrual period and the birth of the newborn. |

| Parity | C16 | Number of times a woman has been pregnant. | |

| Birth weight | C17 | Weight of the newborn measured after birth. | |

| Biochemical markers | sFlt-1 (µg/L) | C18 | Soluble protein of the Fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor (FLT1) that acts as an antiangiogenic receptor. |

| PIGF (µg/L) | C19 | Protein responsible for normal placental growth. | |

| sFlt-1/ PIGF | C20 | Ratio for assessing the risk of preeclampsia. | |

| Target | PE and PE + IUGR | C21 | Presence or absence of preeclampsia or intrauterine growth restriction. |

| Type of Variable | Variable | Concept | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal and fetal variables | Age (years) | C1 | Length of life since birth. |

| BMI (kg/m2) | C2 | Weight and height ratio for calculating body mass. | |

| Gestational age of delivery (weeks) | C3 | Weeks between the first day of the mother’s last menstrual period and the birth of the newborn. | |

| Gravidity | C4 | Total number of pregnancies a woman has had, regardless of the outcome. | |

| Parity | C5 | Number of pregnancies that have reached a viable stage (>20 weeks of gestation). | |

| Signs and symptoms | Initial onset symptoms (IOS) | C6 | Initial or early symptoms in pregnant women. |

| Gestational age of IOS onset | C7 | Number of weeks elapsed from the first day of the last menstrual period to the onset of initial symptoms. | |

| Interval from IOS onset to delivery | C8 | Weeks elapsed from the onset of symptoms to delivery. | |

| Gestational age of hypertension onset | C9 | Number of weeks elapsed from the first day of the last menstrual period to the onset of hypertension. | |

| Interval from hypertension onset to delivery | C10 | Weeks elapsed from the onset of hypertension to delivery. | |

| Gestational age of edema onset | C11 | Number of weeks elapsed from the first day of the last menstrual period to the onset of edema. | |

| Interval from edema onset to delivery | C12 | Weeks elapsed from the onset of edema to delivery. | |

| Gestational age of proteinuria onset | C13 | Number of weeks elapsed from the first day of the last menstrual period to the onset of proteinuria. | |

| Interval from proteinuria onset to delivery | C14 | Weeks elapsed from the onset of proteinuria to delivery. | |

| Expectant treatment | C15 | Management strategy that aims to prolong pregnancy. | |

| Anti-hypertensive therapy before hospitalization | C16 | Administration of antihypertensive treatment prior to hospitalization. | |

| Past history | C17 | Previous history of hypertension. | |

| Maximum systolic blood pressure (mm/Hg) | C18 | Highest blood pressure value when the heart contracts. | |

| Maximum diastolic blood pressure (mm/Hg) | C19 | Highest blood pressure value when the heart relaxes between beats. | |

| Reasons for delivery | C20 | Indications for termination of pregnancy. | |

| Mode of delivery | C21 | The way in which birth occurs. | |

| Routine laboratory tests | Maximum BNP value (pg/mL) | C22 | Highest result for B-type natriuretic peptide. |

| Maximum creatinine value (µmol/L) | C23 | Highest creatinine result. | |

| Maximum uric acid value (µmol/L) | C24 | Highest uric acid result. | |

| Maximum proteinuria value (mg/24 h) | C25 | Highest result for proteinuria in 24-h urine sample. | |

| Maximum total protein value (g/L) | C26 | Highest total proteinuria result. | |

| Maximum albumin value (g/L) | C27 | Highest albumin result. | |

| Maximum ALT value (UI/L) | C28 | Highest alanine aminotransferase result. | |

| Maximum AST value (UI/L) | C29 | Highest aspartate aminotransferase result. | |

| Maximum platelet value | C30 | Highest platelet count. | |

| Target | Fetal weight | C31 | Fetal weight at birth. |

| Technique | Hyperparameter | Configuration Options |

|---|---|---|

| FCM | Activation function Inference function | Sigmoid, Hyperbolic tangent Kosko, Modified Kosko, Rescaled |

| PSO | Population Size Iteration Steps | Random values between 15–199 Random values between 16–500 |

| Technique | Hyperparameter | Configuration Options |

|---|---|---|

| FCM | Activation function Inference function | Sigmoid, Hyperbolic tangent Kosko, Modified Kosko, Rescaled |

| GA | Population Size Random mutation Flat Crossover | Random values between 11–199 Random values between 0.01–1.0 Random values between 0.01–1.0 |

| Dataset | Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Population Size | Iteration Steps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | FCM- PSO | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 54 | 64 |

| FCM- GA | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 83 | 120 | |

| IUGR | FCM- PSO | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 196 | 74 |

| FCM- GA | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 136 | 120 | |

| PE+ IUGR | FCM- PSO | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 36 | 24 |

| FCM- GA | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 24 | 120 |

| Study | Prediction | Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salinas et al. [71] | PE | Fuzzy Model-GA | 0.91 | 0.60 | 0.88 | 0.71 |

| Liu et al. [72] | PE | RF | 0.74 | 0.82 | 0.42 | 0.56 |

| Vasilache et al. [73] | PE | RF | 0.96 | 0.63 | - | 0.74 |

| Hoyos et al. [34] | PE | FCM + PSO | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.82 |

| Gómez-Jemes et al. [74] | PE + IUGR | RF | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.85 |

| Sufriyana et al. [75] | PE + IUGR | CVR | 0.90 | - | - | - |

| Our work | PE | FCM + PSO | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García, M.P.; Díaz-Meza, J.D.; Hoyos, K.; Pacheco, B.; García, R.; Hoyos, W. Combining Fuzzy Cognitive Maps and Metaheuristic Algorithms to Predict Preeclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Informatics 2025, 12, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics12040141

García MP, Díaz-Meza JD, Hoyos K, Pacheco B, García R, Hoyos W. Combining Fuzzy Cognitive Maps and Metaheuristic Algorithms to Predict Preeclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Informatics. 2025; 12(4):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics12040141

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía, María Paula, Jesús David Díaz-Meza, Kenia Hoyos, Bethia Pacheco, Rodrigo García, and William Hoyos. 2025. "Combining Fuzzy Cognitive Maps and Metaheuristic Algorithms to Predict Preeclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction" Informatics 12, no. 4: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics12040141

APA StyleGarcía, M. P., Díaz-Meza, J. D., Hoyos, K., Pacheco, B., García, R., & Hoyos, W. (2025). Combining Fuzzy Cognitive Maps and Metaheuristic Algorithms to Predict Preeclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Informatics, 12(4), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics12040141

_Bryant.png)