1. Introduction

Ontologies are formal representations of knowledge that describe the concepts in a knowledge domain, their relationships, and associated instances. They provide a structured framework for representing and reasoning about knowledge, supporting areas such as knowledge representation, artificial intelligence (AI), and data management. In knowledge representation and AI, ontologies help standardize terminology and organize domain knowledge in large datasets, enabling automated reasoning tasks such as inference, problem-solving, and theorem proving [

1,

2,

3]. They often serve as advanced thesauri for query expansion, improving search effectiveness and interoperability [

4,

5]. In data management, ontologies are central to data integration by supporting the unification of heterogeneous data sources [

6] and enhancing concept recognition. A key approach is

ontology-based data access, which uses ontologies to enable reasoning over large datasets—typically stored in databases—to answer complex queries [

7].

Ontologies are widely used to represent structured knowledge across various domains. In biology, the

Gene Ontology (GO) [

8] and the

Sequence Ontology (SO) [

9] provide standardized annotations for genes and sequences. In medicine, the

Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) [

10], the

Disease Ontology (DO) [

11], and

MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) [

12] support standardized indexing and search of biomedical literature and clinical data. In the legal domain, ontologies such as

LKIF-Core [

13] and

LOTED2 [

14] support legal reasoning and document management. When no ontology exists for a given domain, one can often be developed to capture its core concepts and relationships.

A persistent challenge in working with ontologies is their size and complexity. Many widely used ontologies—such as GO and HPO—contain hundreds of thousands of concepts, making them difficult to navigate, search, and understand, particularly for non-expert users. Using such ontologies effectively requires

exploratory learning, a process through which users build mental models by identifying key concepts, understanding their relationships, and uncovering structural patterns [

15]. This process often involves locating

landmarks (central or well-known concepts), following

routes (chains of related concepts), and exploring

neighborhoods (clusters of semantically related concepts).

Exploratory learning over ontologies often involves two core activities: searching for relevant concepts and querying to express complex information needs. Search is typically based on keyword matching against concept labels or textual descriptions in the ontology. While simple to use, such methods frequently fail due to vocabulary mismatch, ambiguity, or variation in phrasing. On the other end of the spectrum, formal query languages such as SPARQL [

16], OWL-QL [

17], SeRQL [

18], and SPARQL-DL [

19] offer expressive power but require users to understand both the ontology’s structure and the syntax of the query language. These limitations make them difficult to use, especially for non-experts, and the results often require further interpretation. As a result, users exploring large ontologies are left with few practical options when their information needs are vague, evolving, or difficult to articulate precisely.

To address this gap, we propose a querying approach that strikes a balance between expressiveness and simplicity. Instead of writing formal queries, users define new concepts by composing existing primitive concepts in the ontology using set operators—conjunction, disjunction, and negation. These user-defined composite concepts are treated as fuzzy queries and are compared against the ontology to retrieve the most semantically similar primitive concepts. This supports intuitive interaction, flexible query construction, and approximate matching—even when the target composite concept is not explicitly defined in the ontology or when the query is underspecified or partially conflicting. Our approach enables users, particularly non-experts, to express their intent using simple, interpretable building blocks while still benefiting from the structure and semantics of the ontology. We now illustrate this with an example.

Example 1. To illustrate our querying approach, consider a physician, whom we refer to as the user, exploring HPO to investigate a patient’s symptoms: difficulty speaking and swallowing, with no indication of immune dysfunction. The user suspects a neuromuscular issue but is unsure of the precise terminology.

Through browsing and personal knowledge, the user finds three relevant primitive concepts:

Slurred speech (HP_0001350),

Dysphagia (difficulty or discomfort in swallowing, HP_0002015), and

Abnormality of the immune system (HP_0002715). Using our interface, they define a composite query concept

:

This concept captures the co-occurrence of speech and swallowing difficulties while explicitly excluding immune-related causes. Such a combination is not explicitly defined in the ontology and would typically yield no results using standard (non-fuzzy) query tools.

Using our fuzzy querying approach, the system interprets this as a soft concept and returns the most similar known phenotypes. These may include Pseudobulbar paralysis (HP_0007024), referring to a neurological condition, which exhibits some of the patient’s symptoms, or Abnormal esophagus physiology (HP_0025270), referring to structural abnormalities of the patient’s esophagus, which could lead to food entering the airway. Both are relevant concepts to the user’s intent and could be difficult to find through keyword search alone.

This scenario is provided solely to illustrate ontology exploration and similarity-based concept retrieval and does not make claims for diagnostic or clinical usage.

To implement our querying approach, we represent ontologies as fuzzy ontologies with fuzzy interpretations, where each concept is treated as a fuzzy set assigning a membership degree to each element in the interpretation domain. Given an ontology, we use existing fuzzy reasoners to construct such interpretations that approximately satisfy the ontology’s axioms. Based on these interpretations, we introduce a novel method for generating ontology embeddings, where each concept is represented as a vector of membership degrees over a fixed, ordered set of domain elements. This allows us to precompute embeddings for all primitive concepts offline. At query time, when a user defines a composite concept using conjunction, disjunction, or negation over known primitives, its embedding is computed by applying the corresponding fuzzy operations element-wise to the membership vectors. This compositional capability enables flexible query construction and is not supported by existing ontology embedding methods. The resulting embeddings also support efficient similarity computations (e.g., cosine similarity) between user-defined composite concepts and existing primitive concepts in the ontology, enabling approximate matching even when no exact concept exists.

We implement this querying approach in FuzzyVis, a visual system for ontology exploration. In addition to standard features such as keyword search and typical ontology views, FuzzyVis provides a complex interactive visualization with features such as fisheye distortion and annotation for navigating large ontologies. Users can build visual queries by collecting relevant primitive concepts and combining them using logical operations such as conjunction, disjunction, and negation. The system computes the embedding of the resulting composite concept and returns the most similar primitive concepts as suggestions. Beyond querying, FuzzyVis supports interactive exploration by linking search, query results, and navigation. Concepts returned in results can be located in the primary visualization, and collected concepts can be reused across queries. By combining fuzzy ontology embeddings, query answering, and an intuitive visual interface, FuzzyVis enables non-experts to query and explore large ontologies effectively. It supports exploratory learning through flexible query construction, approximate matching, and structural similarity, addressing key limitations of existing ontology querying tools.

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work.

Section 3 introduces the necessary preliminaries and background concepts.

Section 4 presents our fuzzy ontology embeddings and describes our querying approach based on these embeddings.

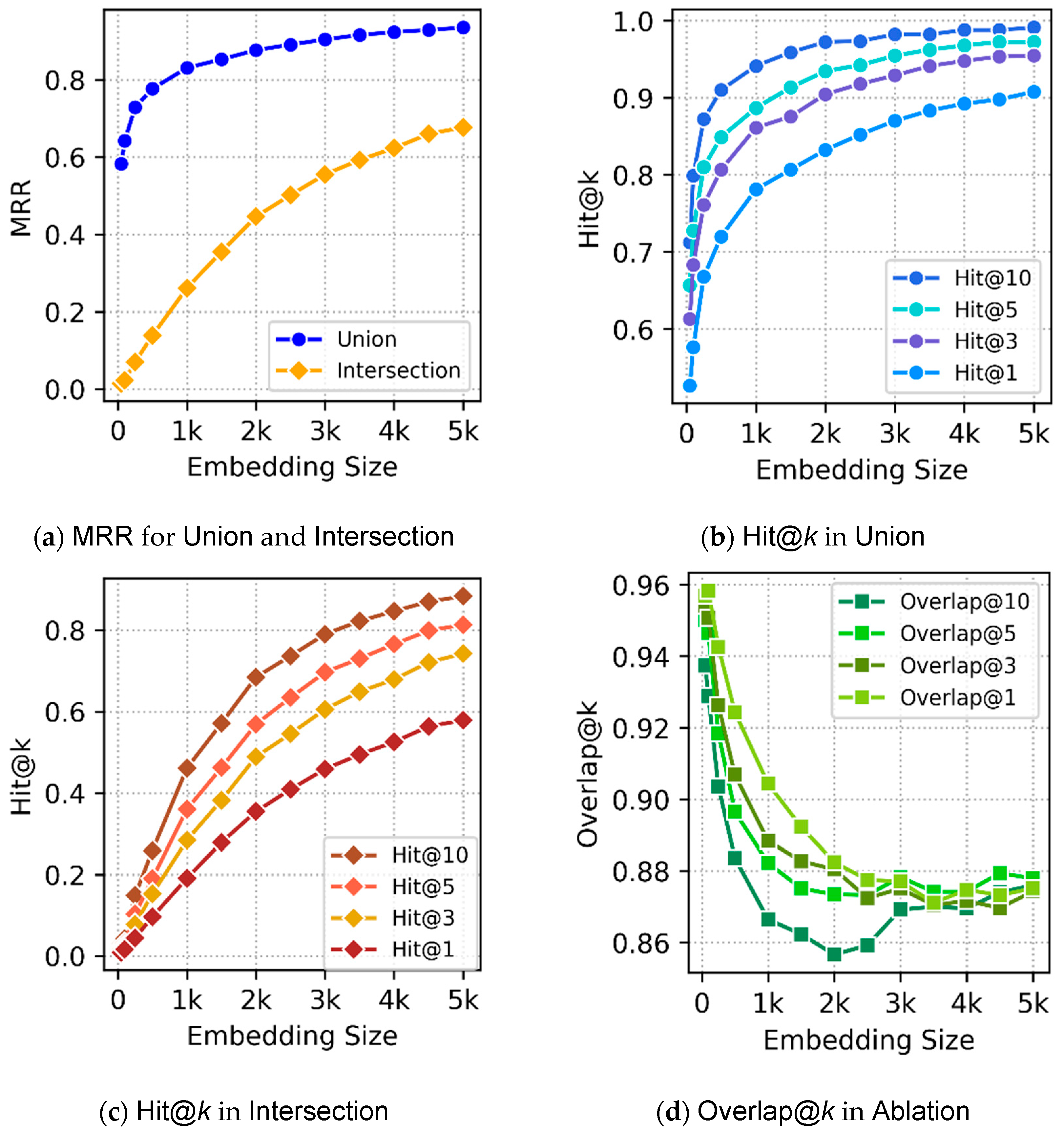

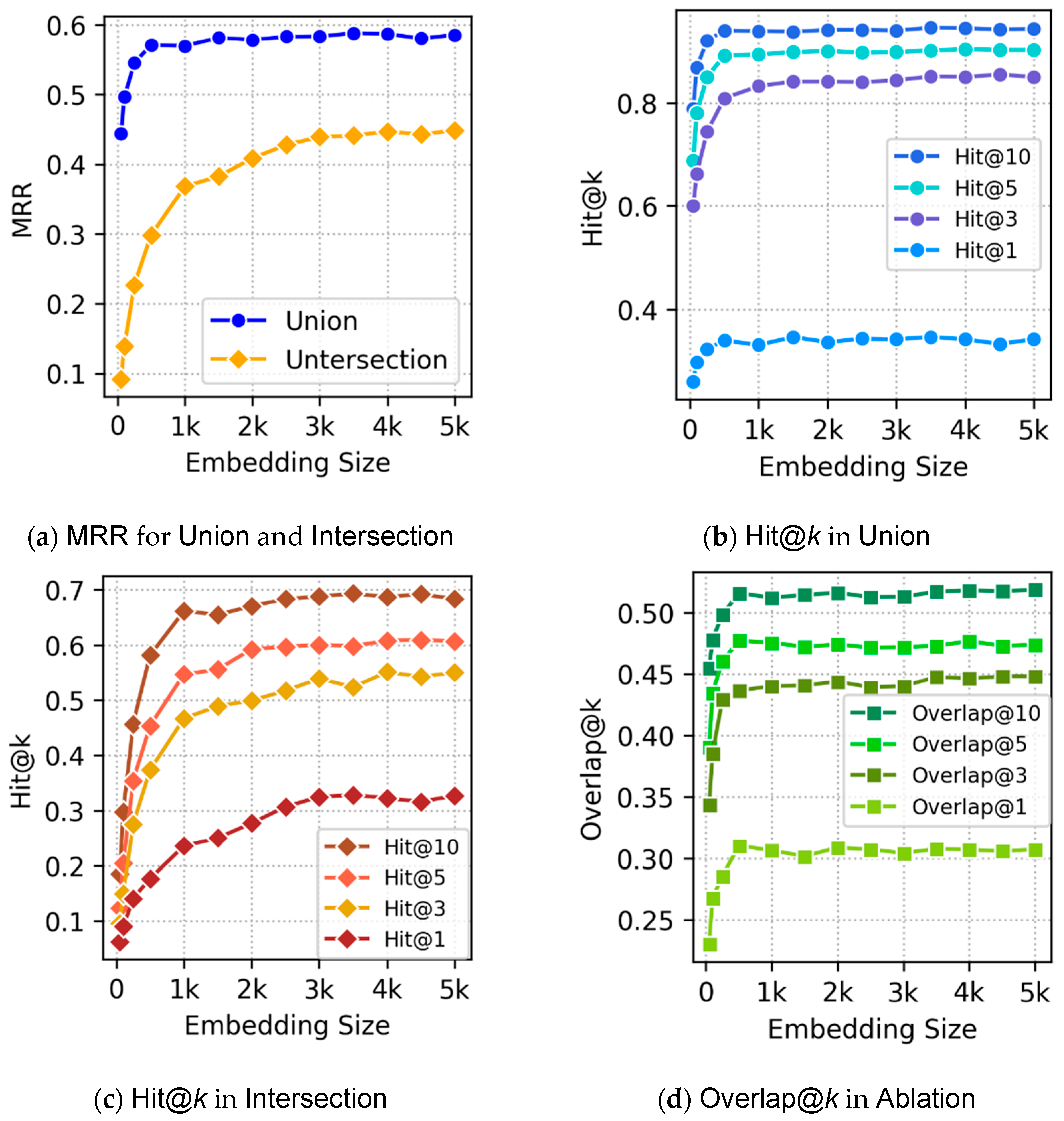

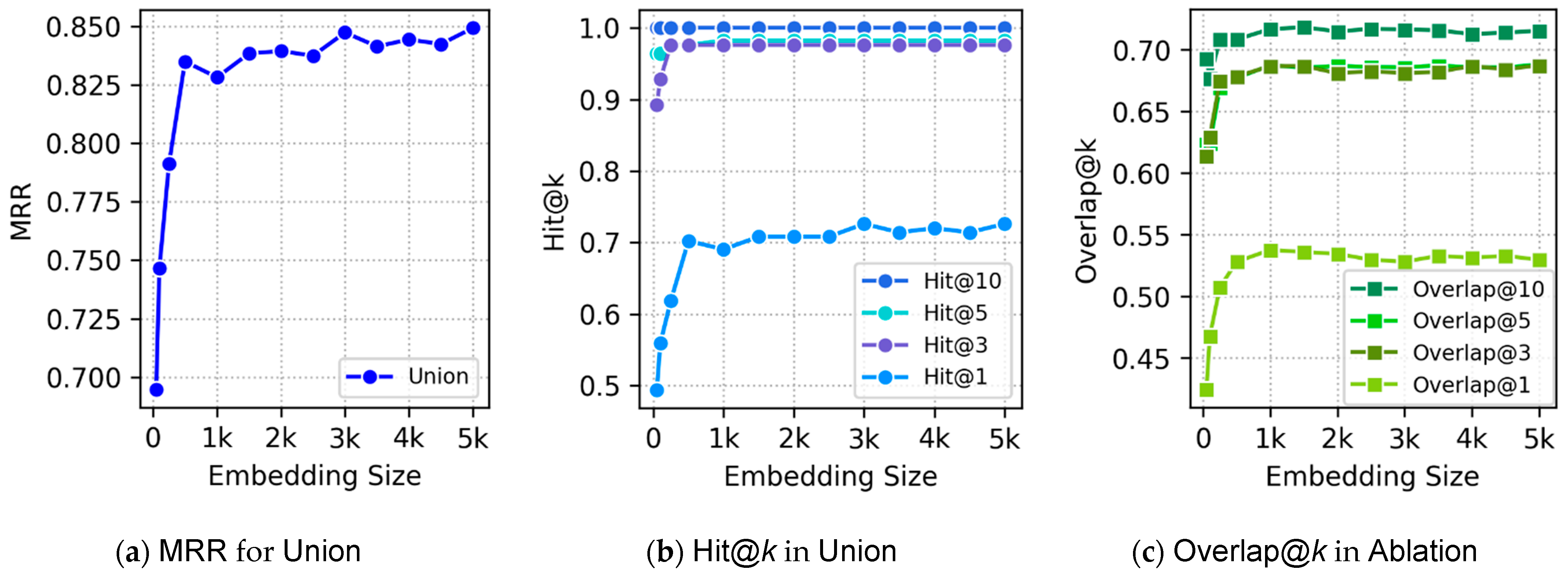

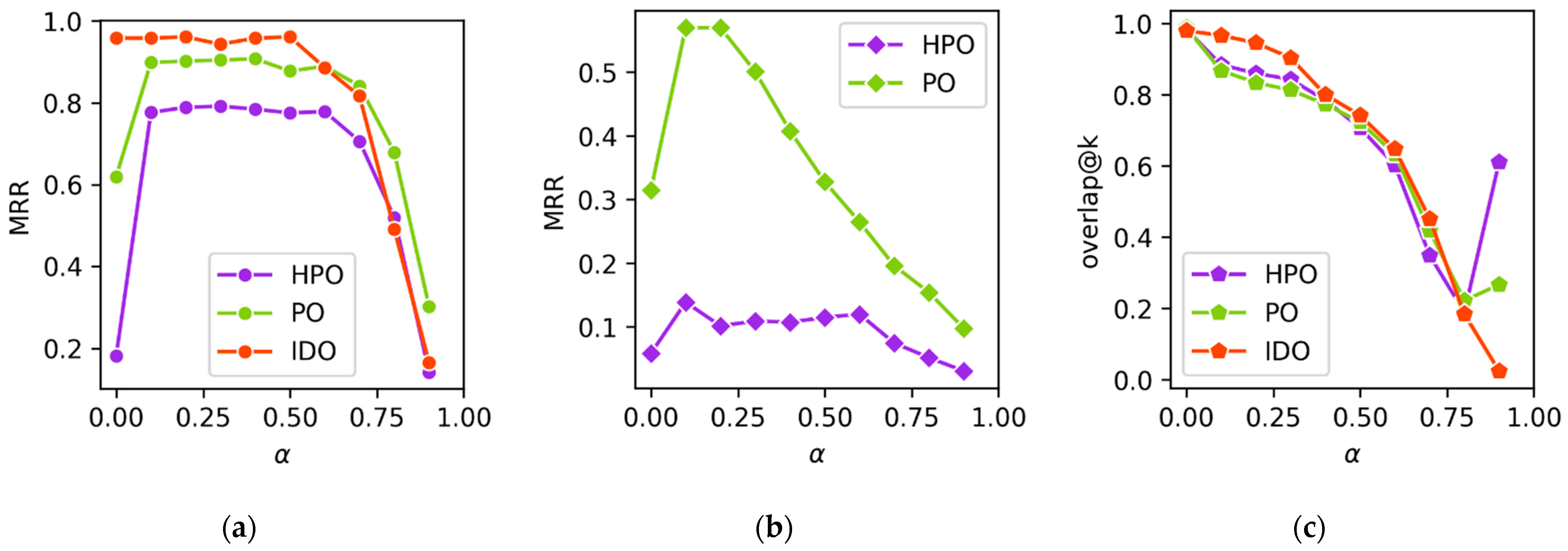

Section 5 discusses experimental evaluation of our embeddings.

Section 6 details the FuzzyVis system, its implementation, and practical use cases.

Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines future directions.

4. Ontology Querying Using Fuzzy Ontology Embeddings

We now formalize our embedding framework and describe how fuzzy interpretations enable semantically grounded concept similarity search over large ontologies.

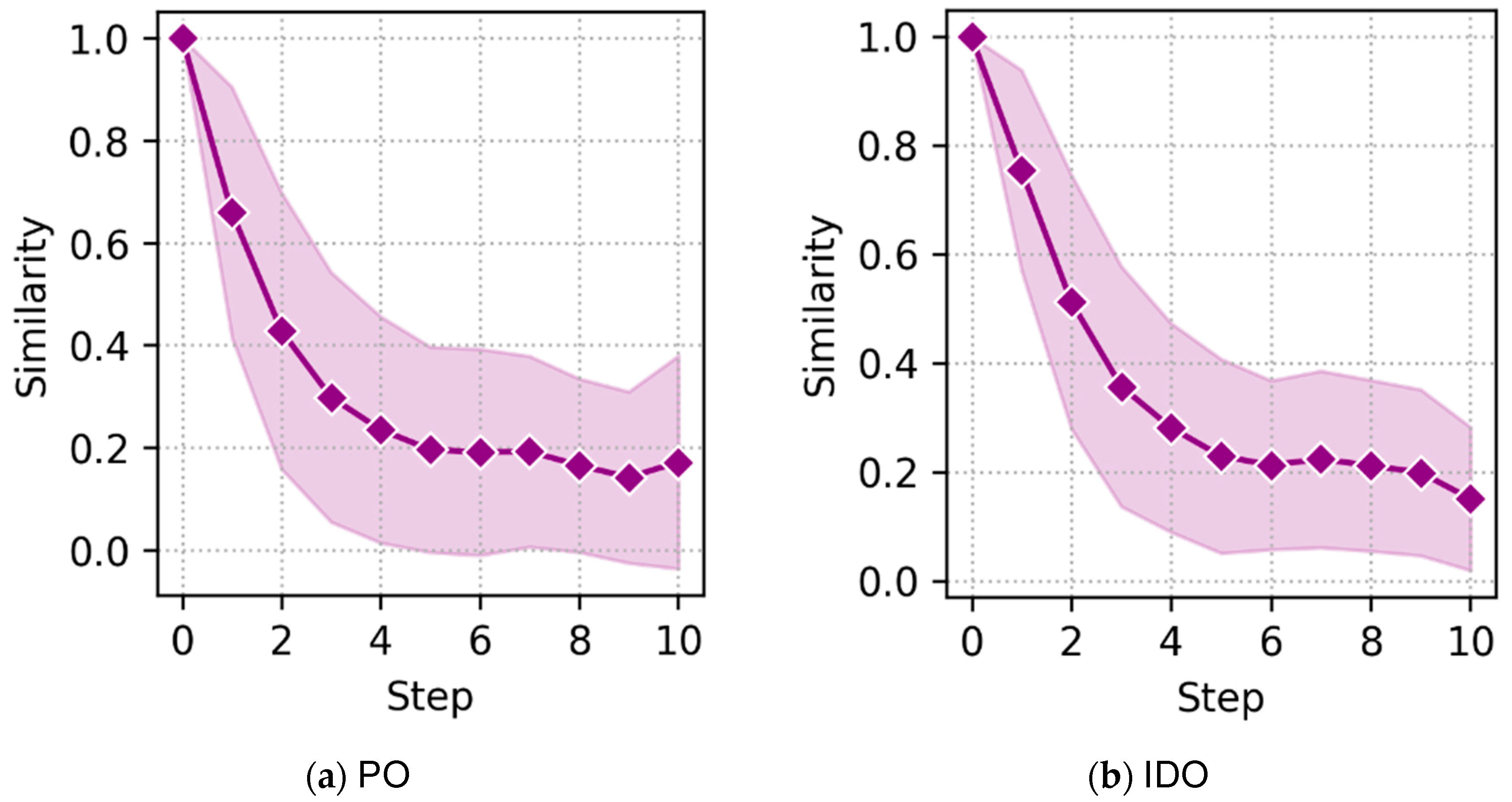

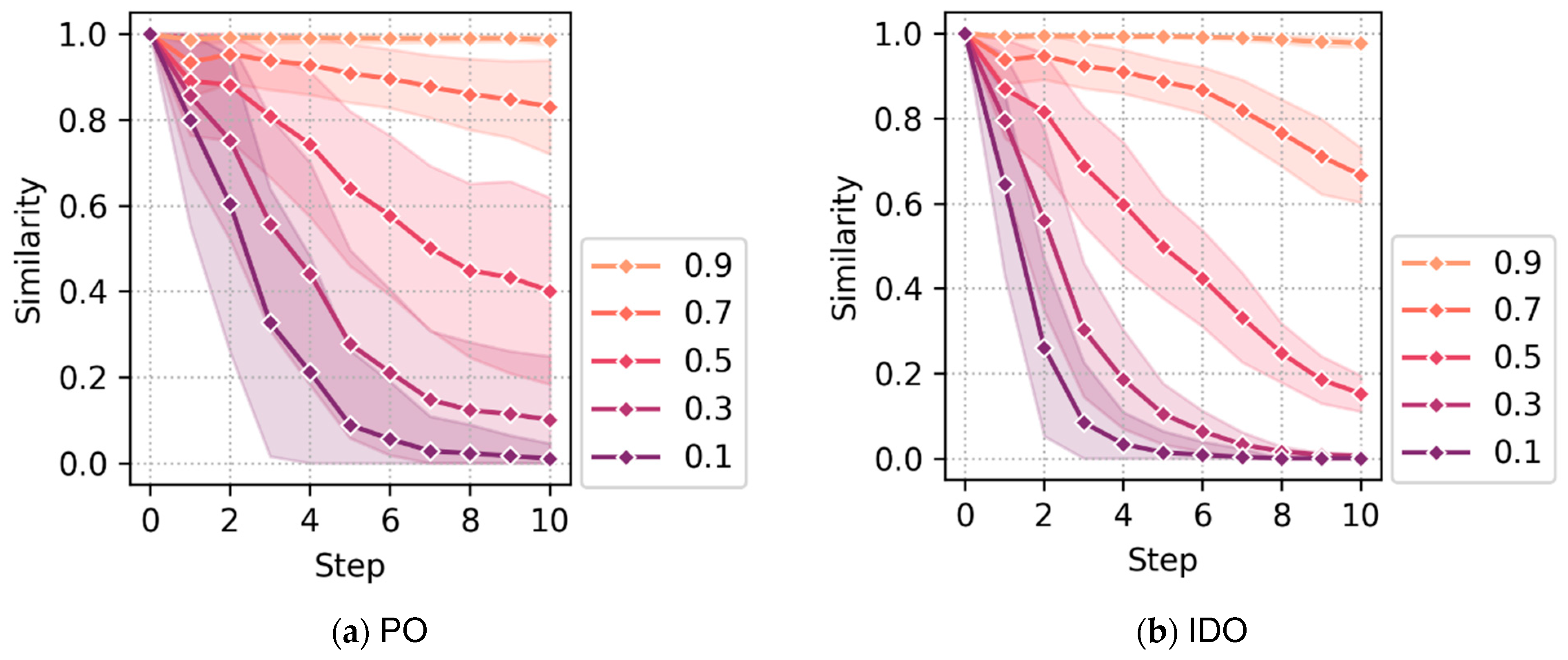

4.4. α-Embeddings for Hierarchical Ontologies

Many real-world ontologies, especially in biomedicine, exhibit a hierarchical structure: concepts are organized along taxonomic “is-a” relationships, and the subsumption relation naturally induces a partial order. For such ontologies, the hierarchical organization strongly encodes semantic proximity—concepts that are close in the hierarchy should receive similar embeddings, whereas distant concepts should be semantically separated. To exploit this structure in a principled yet efficient way, we introduce -interpretations: synthetic fuzzy interpretations that capture hierarchical similarity through a controlled decay parameter. Before defining them formally, we first formalize what it means for an ontology to be hierarchical.

Definition 3 (Hierarchical Ontology). Let

be an ontology with concept set , and let denote the subsumption relation on induced by the TBox . We say that is hierarchical if defines a partial order, meaning it is reflexive ( for all ), antisymmetric (if and

, then ), and transitive (if and

, then ). If each concept has at most one direct parent (i.e., at most one such that and no intermediate concept lies between them), then the hierarchy forms a tree. If concepts may have multiple direct parents, the hierarchy forms a polyhierarchy or a DAG taxonomy.

This definition captures both strict taxonomic trees (e.g., IDO [

74]) and more general DAG-shaped ontologies with multiple inheritance (e.g., HPO), while ensuring the absence of cycles and the validity of subsumption as a partial order.

We now define a synthetic fuzzy interpretation tailored for hierarchical ontologies. This interpretation explicitly encodes semantic proximity along the hierarchy through a decay parameter .

Definition 4 (α-Interpretation). Let

be hierarchical and let be a chosen finite domain. An-interpretation of is a fuzzy interpretation constructed as follows. For each domain element

:

Select a leaf concept .

Set to .

For every other leaf concept

, set

, where

is the minimum number of edges from

and

, over all shared ancestors, of the larger of their distances to that ancestor.

For any internal concept

with children

, define the following:where is a fuzzy union aggregation (e.g., probablistic sum).

This definition applies directly to tree-shaped hierarchies. For polyhierarchies (multiple inheritance), the same rules apply, with aggregation over all parents via

. Algorithm 2 outlines the high-level procedure for constructing an

-interpretation over a hierarchical ontology.

| ) |

| 1: | |

| 2: | do |

| 3: | | uniformly at random |

| 4: | | |

| 5: | | for all other leaves do |

| 6: | | | |

| 7: | | for all internal node in bottom-up order do |

| 8: | | | |

| 9: | |

By construction, an -interpretation satisfies all subsumption axioms of a hierarchical ontology. Indeed, whenever , the membership degree of any domain element to the parent concept is obtained via a fuzzy union of the membership degrees of its children, ensuring for all . Thus, is an exact model of any ontology whose only axioms are taxonomic subsumptions. For ontologies containing additional axioms (e.g., disjointness, existential restrictions, value constraints), an -interpretation may satisfy those axioms only to a degree, depending on the hierarchy structure and the chosen decay and aggregation functions. Nevertheless, for hierarchical ontologies—the primary focus of our use cases— provides a coherent and semantically grounded interpretation that preserves the intended taxonomic semantics.

We chose to adopt a decaying membership function for

-embeddings, specifically

, for its ease of computation, its non-reliance on any ontology-specific concept properties (e.g., descriptions), and its membership decaying exponentially as distance increases, which emphasizes local neighborhoods without doing so for distant concepts. In the literature, exponential decay functions are regularly used for graphing and taxonomy [

75,

76,

77].

Once an

-interpretation

is fixed, embeddings for primitive and composite concepts follow directly from the general definition in

Section 4.1.

Definition 5 (

-Interpretation). For any concept

, the

-embedding of

isComposite concept embeddings are computed via the recursive rules in Definition 2, using the same fuzzy operators as those used to construct the -interpretation. Using the same fuzzy operators (, , ) at the interpretation and embedding stages preserves semantic consistency and aligns embedding computations with the underlying fuzzy semantics for best performance.

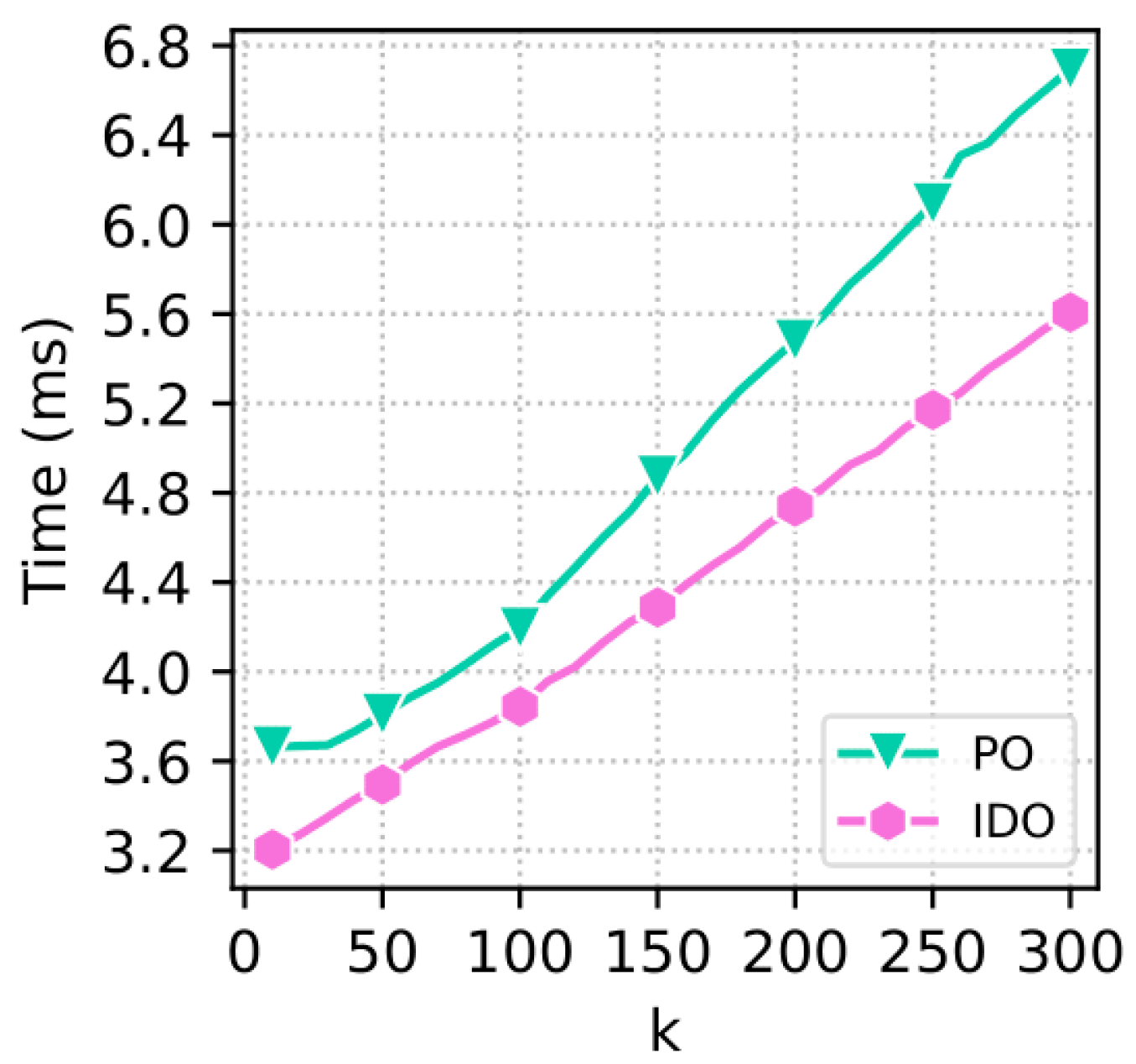

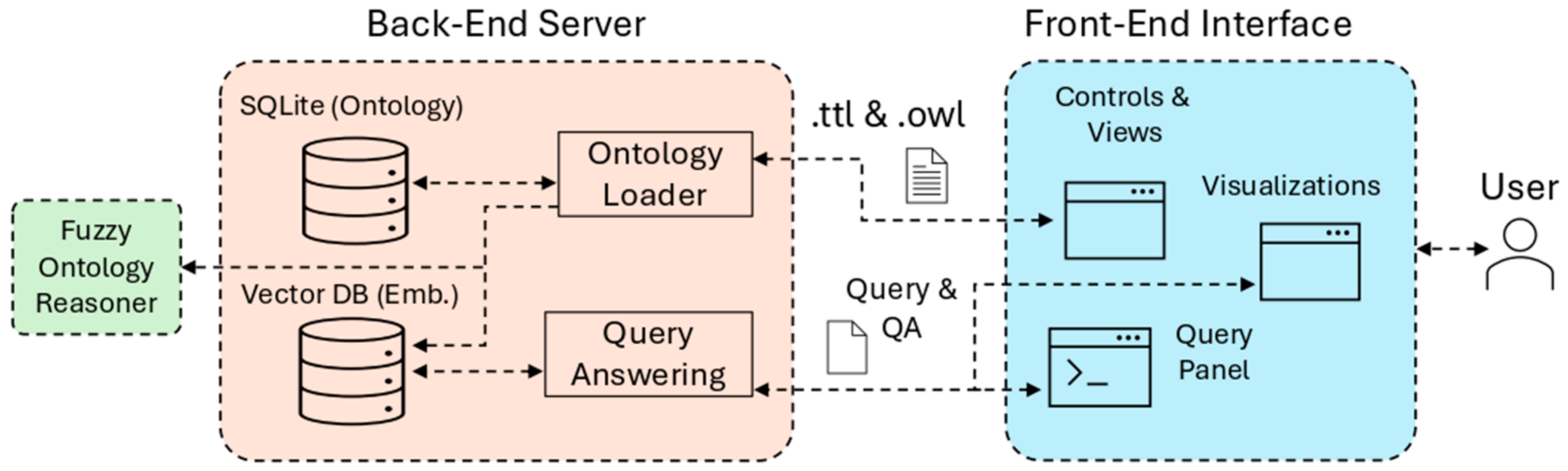

6. The FuzzyVis System

In this section, we present our prototype system,

FuzzyVis.

Section 6.1 describes its architecture and important implementation details.

Section 6.2 further discusses the back-end server functionality.

Section 6.3 does the same for the front-end interface. Lastly,

Section 6.4 explores the prior Example 1 in greater depth as a usage scenario that shows how FuzzyVis supports ontology exploration and search through visual query building and approximate reasoning. FuzzyVis is a research prototype and is not approved for clinical diagnostic use.

6.3. Front-End Interface

The front-end is composed of several regions consisting of panels and controls that support interactive ontology exploration.

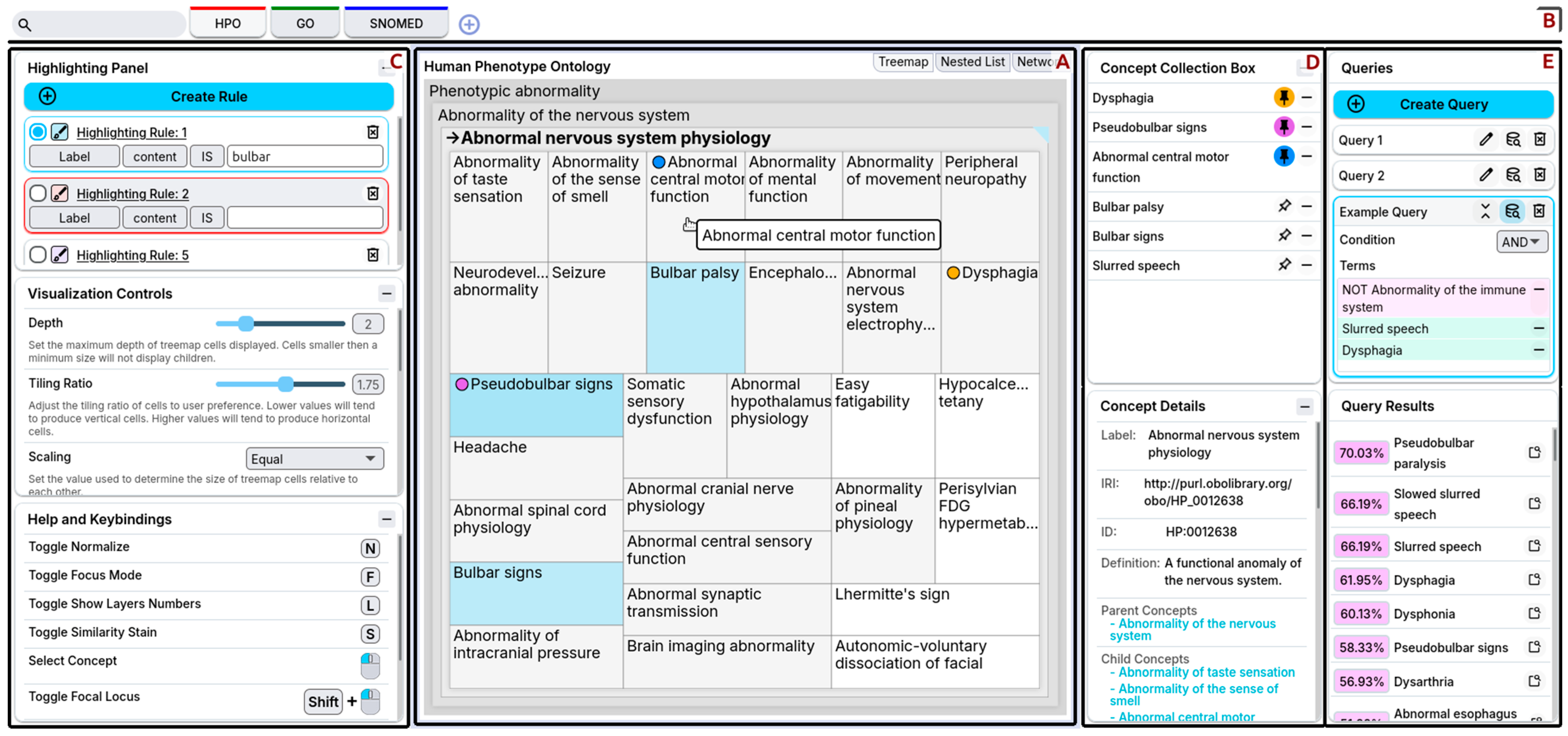

Figure 9 shows an overview of the front-end interface as seen by the user. The primary visualization takes up the central region of the interface and is the user’s primary means of navigating the ontology (

Figure 9A). Users can change between different visualizations—treemaps, nested lists, and network graphs—in this central region. The second region (

Figure 9B), the top header, provides quick access for concept search, switching between loaded ontologies, and loading ontologies. Users can manipulate the behavior and control the presentation using the visualization controls in the leftmost region (

Figure 9C). The first of the rightmost regions (

Figure 9D) is the concept panels, where users can store concepts for future use and look at concept details. The second rightmost region (

Figure 9E) is the query building panels, where users define queries and examine their results. FuzzyVis’s front-end is compatible with all major web browsers.

Below, we describe the main components of the front-end interface in more detail.

6.3.1. Primary Visualizations

FuzzyVis’s central region contains the primary visualization (

Figure 9A). Here, users see a representation of the ontology to aid them in exploration and understanding. Each component of FuzzyVis serves to modify, control, and navigate the primary visualization, with the back-end providing any information needed by the primary visualization. The primary visualization can take the form of any suitable representation of the ontology. Visualization should meet the following criteria:

Concept Distinguishability. Each concept in the visualization must be distinct and individually identifiable, at a reasonable scale. The density of concepts must be low enough that users can distinguish them. As well, concepts must have some clear identifier—often this is a label.

Consistent. The visualization should represent concepts and relationships in a consistent and identifiable manner.

Dynamic and Interactive. The visualization should react to users’ actions. Static representations may be sufficient for small and simple datasets, but ontologies are often neither small nor simple. Dynamic visualizations adapt to users’ needs and can change to show the ontology information that they are interested in, especially when presenting the entire ontology is impractical.

Property-revealing. The visualization should present secondary information and metadata of concepts. Features such as concept descriptions, depth, subtree size, and metadata contain information necessary to understand the content of ontologies. Users may be unfamiliar with concept labels and require secondary information to understand an ontology.

Space-efficient. The visualization should utilize the available space fully. Some ontologies have a large amount of content and visualizations that make poor use of space, are either sparse or dense to the point of uselessness.

Structure-revealing. The visualization must showcase the primary semantic structure of the ontology. In most cases, this is the concept subsumption hierarchy. One of the primary purposes of ontologies is to express how concepts relate to one another. This information is critical to users’ understanding of ontologies.

Classical visualizations such as nested lists, icicle charts, network graphs, and treemaps only partially meet these requirements. In fact, no single static visualization can satisfy every requirement. Network graphs become unreadable with large numbers of concepts, nested lists waste space, and treemaps struggle to convey secondary information. Our approach addresses these limitations by combining the primary visualization with secondary panels for additional details and utilizing dynamic interactive visualizations. To illustrate how FuzzyVis meets these requirements, we describe the nested-treemap version of the primary visualization.

Nested-treemaps represent concepts as rectangles, place sibling concepts adjacent to each other, and nest child concepts inside their parents’ area to indicate hierarchy. They are well-suited for ontology visualization because they clearly distinguish concepts, are consistent, space-efficient, and structure-revealing. Extending nested-treemaps to be dynamic and interactive allows for the display of secondary properties and addresses the problem of excessive concept density.

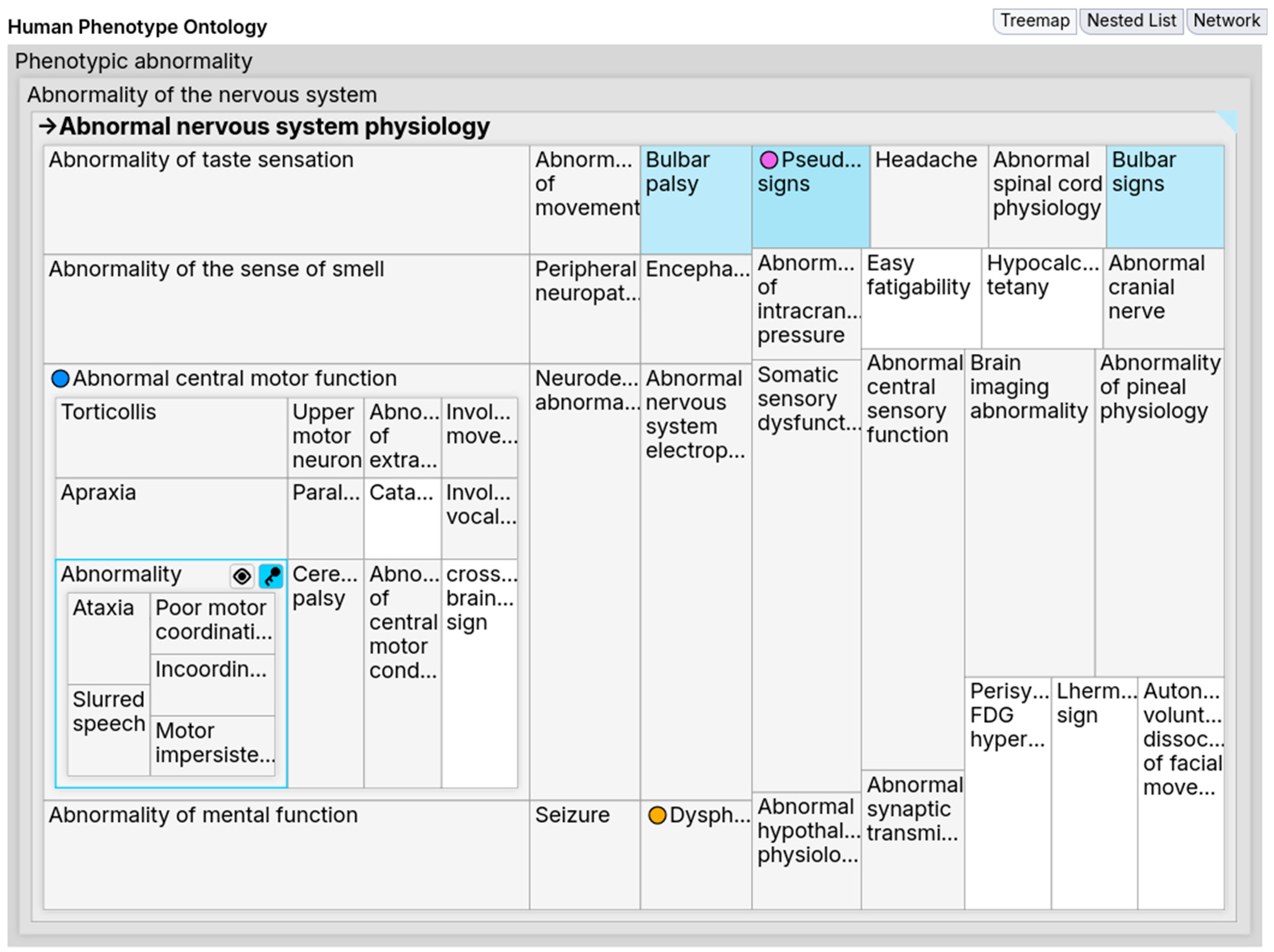

Figure 10 shows FuzzyVis’s nested-treemap (hereafter,

the treemap), which displays concepts within an adjustable distance of a selected concept. As users navigate, the treemap updates to show related concepts and integrates with other FuzzyVis front-end components to support exploration.

Selecting a concept in the treemap refocuses the visualization onto it, allowing users to drill down into its subtree or navigate upward to parent concepts. Users can also drag concepts to other components and pin them for later reference. Pinning creates visual marks that aid in orientation by acting as signposts. These marks help identify when a concept appears in multiple subtrees. For example, in HPO, the Cardiac valve calcification concept is a child of both Cardiovascular calcification and Abnormal heart morphology; when pinned, it becomes more noticeable in both locations, indicating structural overlap. Without such aids, users would need to manually read labels to detect these cases. Once users have collected concepts of interest, they can create queries using the Query Building Panels to guide further exploration.

Users may want to focus on a concept while retaining its context within the ontology. Simply increasing depth causes two issues. One, deeper child concepts receive minimal space, forcing users to mouse over for tooltips to identify them. Two, densely populated subtrees create visual clutter that overwhelms users. Selecting the concept alone does not solve this, as it refocuses the visualization and removes the surrounding context.

To address this, we implemented a toggle for a focus mode that enables on-the-fly visual distortions. During focus mode, when users mouse over a concept, FuzzyVis applies a discrete Cartesian distortion (often referred to as a fisheye distortion or lens), enlarging its area while preserving relative position. Within the expanded area, the subtree extends, showing the focused concept’s children; users can drill down further by mousing over these until no more space is available. If users want to explore multiple subtrees simultaneously, they can lock a concept as a locus, and the distortion will maintain multiple focal points. Moreover, locked loci can be transformed into a different visualization. For example, a concept cell can be converted to a node network graph or a panel showing class details. In essence, this technique directly addresses the problem of maintaining context while refocusing.

Figure 10 shows an example of focus mode in use. With depth set to two and

Abnormal nervous system physiology selected, no concepts other than its children would be visible. Yet, with focus mode turned on, hovering over

Abnormal central motor function fills the subtree with child concepts. Afterwards, when the user mouses over the child

Abnormality of coordination, the subtree is further extended to show this concept’s children (e.g.,

Slurred speech). This can continue until a leaf node is reached or space runs out, but the user decided this depth was sufficient and locked

Abnormality of coordination as a locus. Focus mode thus offers a dynamic and space-efficient way to explore deeper while maintaining orientation. Furthermore, dynamic distortions can be applied to other kinds of visualizations, such as network graphs and charts.

Users adjust the primary visualization through the Visualization Controls. For nested-treemaps, users can adjust depth, the label content (e.g., depth numbers), tiling methods, concept visibility, and highlighting. Such controls are essential, as different ontologies are best viewed with different settings. For instance, in HPO, Abnormality of the musculoskeletal system dominates the space when scaling is proportional to subtree size, making the smaller Abnormality of the voice nearly invisible. Equal scaling makes both visible, reducing the chance of missing concepts. Furthermore, users can toggle such options to see how the visualization changes—turning equal scaling on and off shows users which concepts take up the majority of an ontology while quickly returning to a view suitable for navigation. These adjustments enable richer exploration without restricting users to suboptimal visualizations.

FuzzyVis’s primary visualization, in conjunction with other front-end panels, provides a spatial overview of ontology structure and semantics. By supporting dynamic, interactive navigation, it helps users quickly form mental models and identify key regions of interest—an essential capability for working with complex knowledge domains where manual inspection would be slow and overwhelming. Ultimately, the primary visualization serves as the main interface through which users interact with and explore ontologies.

6.4. Usage Scenario

The following scenario illustrates how FuzzyVis supports ontology exploration and the practical applications of fuzzy logic queries. FuzzyVis is not intended or approved for use as a clinical diagnostic tool, and this scenario is intended to illustrate the potential of using fuzzy ontology embeddings for visual query building and exploration. We use the HPO for this scenario. We assume the user knows basic medical terms but is unfamiliar with HPO. The embedding used is an

-embedding (as described in

Section 4.4) with

, and embedding

Emb-size = 10,000. At

the embeddings express sibling similarity while not hurting concept distinguishability overmuch. The value for

Emb-size was chosen as it was when HPO started to no longer see minor performance improvements. For fuzzy operators, we use the product t-norm for conjunction, its t-conorm for disjunction, and the standard negator for negation, as these performed best during evaluation of

-embeddings (

Section 5.2.2).

A physician, henceforth the user, has a patient who has difficulty speaking and swallowing, with no history of immune disorders and no signs of infection. To help this patient, the user has two goals. One, they want to identify possible conditions that could explain the symptoms. Two, they wish to learn about any secondary ailments that the patient may experience now or in the future. The user knows that HPO contains information about abnormal conditions, but its size and complexity necessitate the use of an exploratory tool. Thus, the user launches FuzzyVis to explore HPO and help their patient.

After FuzzyVis loads HPO, its front-end—displaying a nested-treemap as the primary visualization—presents the ontology to the user. The user starts their exploration by adjusting the settings in the visualization control panel. First, the user sets cell scaling to be equal, as the relative size of concepts is irrelevant to their goals. Second, the user sets the tiling so that labels are clearly visible. Lastly, they set visible depth to a low value—HPO has many terms, and seeing too many layers is overwhelming. Afterwards, the user creates highlight rules to stain concepts containing voice, speech, or swallowing for quick identification. With the user’s initial setup complete, they can now quickly identify concepts of interest. Users of FuzzyVis can, with little effort, set up the primary visualization in ways that streamline their future searches.

Seeing the Phenotypic abnormality concept, the user selects it and begins their search. During their search, the user encounters concepts related to their patient’s condition. These concepts are pinned (for easier identification) and added to the concept collection for use in queries. To explore more specific concepts, the user activates focus mode to drill into Phenotypic abnormality’s children. They see Abnormality of the voice, and although it does not contain what they are looking for, it is collected for query use regardless. Additionally, the user spots Abnormality of the immune system and adds it to the collection, to be negated in future queries.

Wanting to quickly find something, the user inputs speech into the search bar. Among the results is the concept Slurred speech, which matches the patient’s symptoms. Selecting it takes the user deeper into the ontology, where they then pin it. Unsure of where they are, the user toggles on the depth numbers and sees that Slurred speech is eight layers deep and has no children. Then, the user increases the depth to view the full ancestry and spots that Slurred speech is within the Abnormality of the nervous system subtree. The user selects this broader concept, reduces depth for clarity, and continues exploring.

Already the user has started to identify landmark concepts related to their problem, has learned the routes between them, and is now aware of the neighborhood in the ontology that contains concepts of interest. By quickly identifying this information, the user efficiently narrows the search space. FuzzyVis’s support for rapid, seamless navigation allows users to quickly see concept contents at a glance and freely navigate large ontologies.

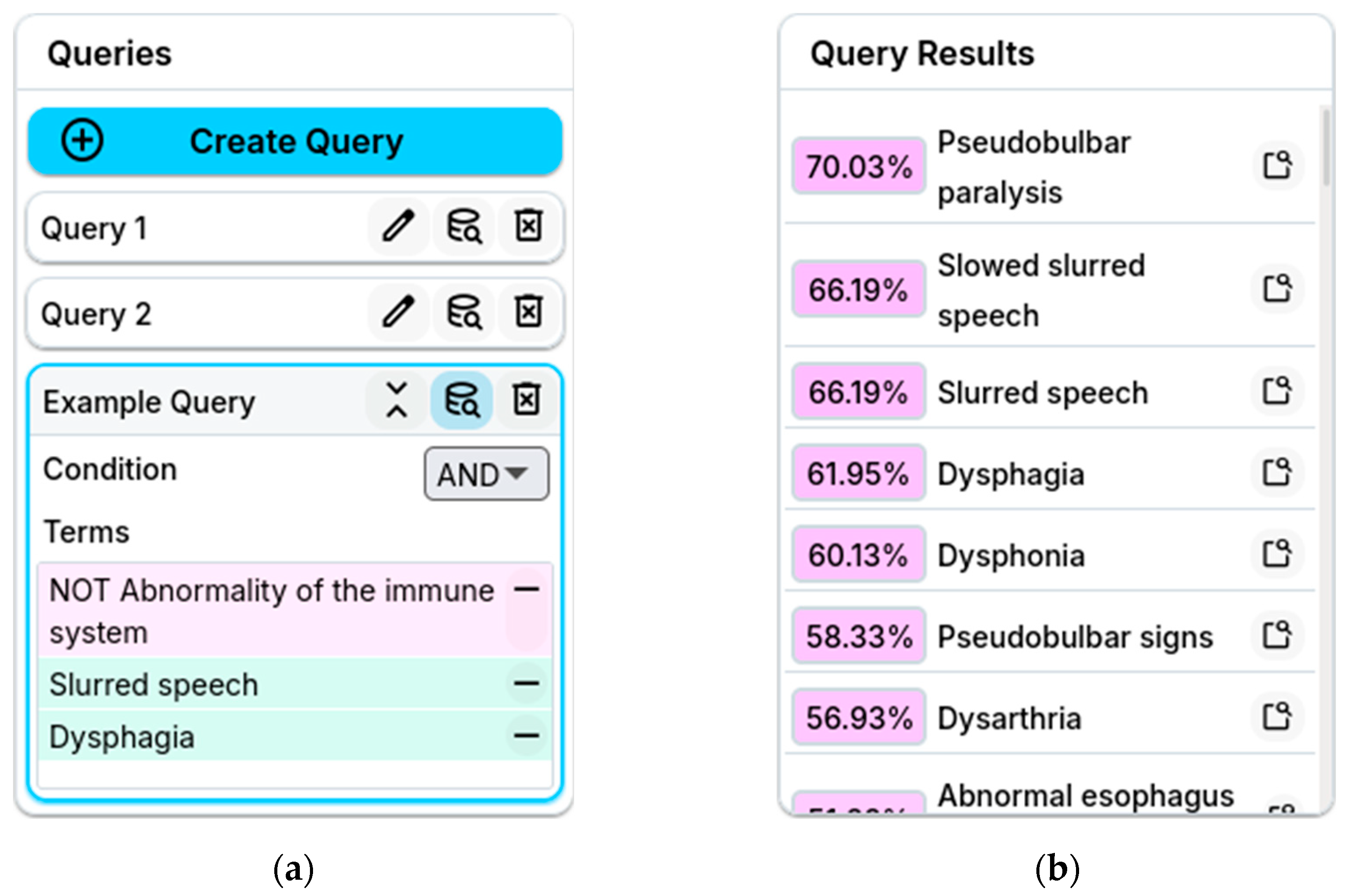

The user’s exploration continues until, within

Abnormality of the nervous system‘s child concept

Abnormal nervous system physiology, they encounter

Dysphagia. The focus mode alternative views and concept details panel show the user that

Dysphagia is the medical term for difficulty swallowing. Combined with the earlier discovery of

Slurred speech, the user feels ready to construct queries. The user formulates their query as the presence of

Slurred speech and

Dysphagia while excluding

Abnormality of the immune system. They do this by dragging concepts from the collection to the query building panel to form the composite concept

1:

The user submits their query, FuzzyVis’s back-end instantly resolves it, and the front-end updates to show the results. Among these results are concepts such as

Pseudobulbar paralysis,

Pseudobulbar signs, and

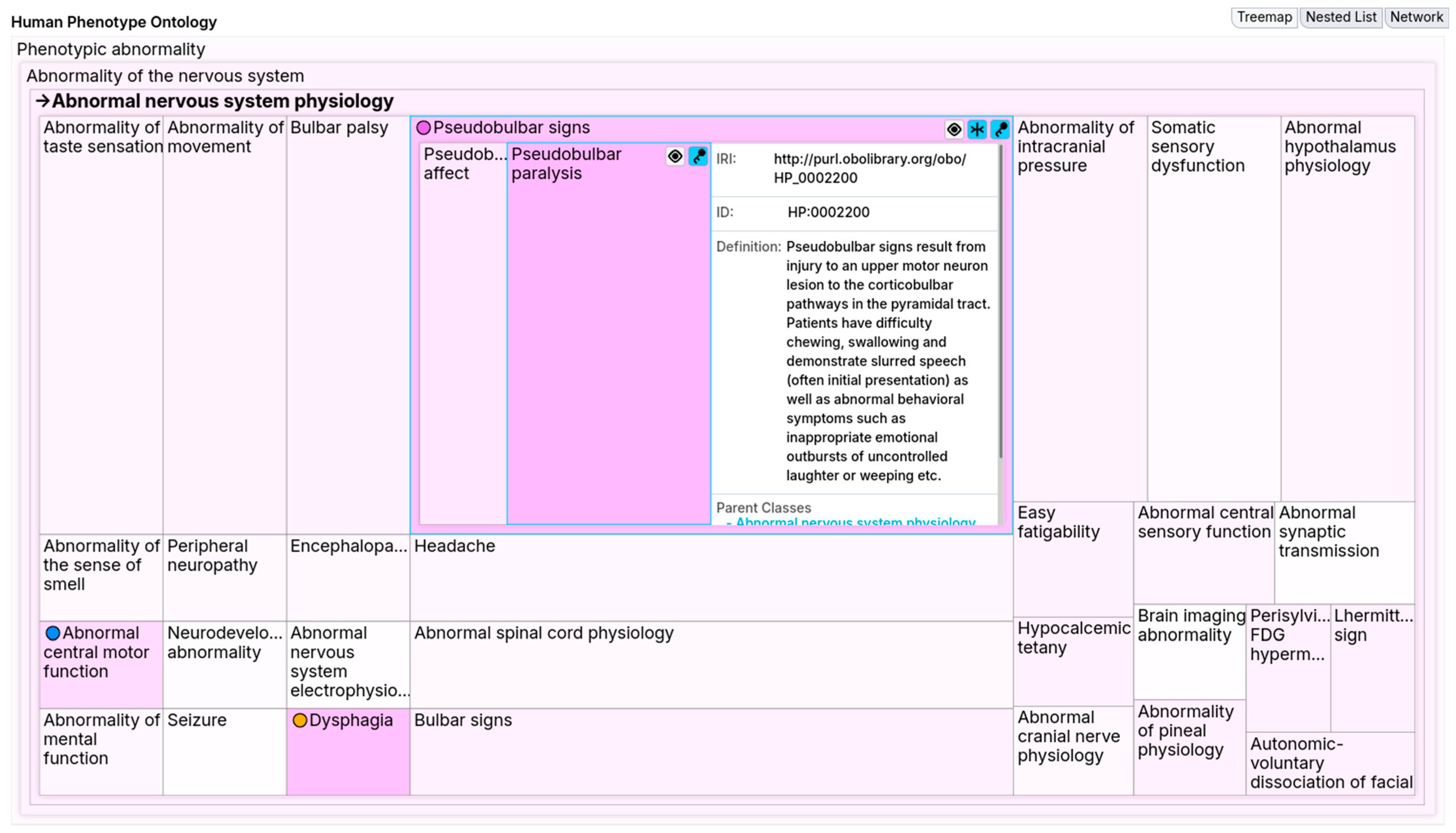

Abnormal esophagus physiology. Wanting to locate these concepts, the user enables the similarity stain and spots the highlighted

Pseudobulbar signs. Using the focus mode, the user locks and splits

Pseudobulbar signs to expand it and see its details. Notably, this reveals

Pseudobulbar paralysis within

Pseudobulbar signs.

Figure 12 shows the combined effect of this similarity stain and focus mode, highlighting the pseudobulbar concepts. These pseudobulbar concepts point to neurological causes that explain the patient’s symptoms. On the other hand,

Abnormal esophagus physiology offers an alternative explanation for the symptoms.

These results have now narrowed down potential causes that the user can investigate to diagnose their patient. Such concepts would have been difficult to find with keyword search, as the user’s vocabulary does not match the ontology’s precisely. Moreover, the user would have been unable to find these concepts with SPARQL queries for this same reason. With FuzzyVis, users build queries visually by dragging and dropping concepts and other queries, without needing to type exact labels. Furthermore, nesting queries helps users separate the components of their queries into understandable segments and construct complex concepts. By supporting fuzzy queries, FuzzyVis enables users to find relevant concepts even when their requests are imprecise.

An example of an imprecise query is the user’s search for secondary ailments. The user creates this query by updating their original one to exclude

Abnormality of the voice. In a non-fuzzy system, excluding

Abnormality of the voice while searching for conditions related to speech and swallowing might seem counterintuitive or overly restrictive. However, because the

-embedding captures fuzzy membership across the ontology, the query can still yield useful insights. The new query narrows the focus to concepts returned by the original that are unrelated to

Abnormality of the voice. The updated query

2 is:

Submitting 2 returns concepts related to digestive issues, which is expected since Dysphagia belongs to the Abnormal esophagus physiology subtree under Abnormality of the digestive system. This suggests the patient’s condition may affect the digestive system. The fuzzy ontology embeddings preserve such relationships even in complex composite concepts. Armed with this knowledge, the user can further question their patient to narrow down their condition. The user asks about irritability and emotional outbursts to check for Pseudobulbar signs, and inspects the throat to check for Abnormal esophagus physiology.

This scenario demonstrates how FuzzyVis’s features and fuzzy ontology embeddings enable effective ontology exploration. Without prior knowledge of HPO’s structure or query languages like SPARQL, the user was able to find relevant concepts and understand their relationships. The interface’s interactive visualizations allow the user to build queries visually, while fuzzy logic supports the creation of useful queries even without expert knowledge. Together, these capabilities present a flexible and user-friendly approach to exploring ontological information.