1. Introduction

Fake news is unconfirmed or exaggerated or distorted news based on uncertainty and dissemination. There is a strong relationship between the development of the Internet and fake news. The rise and popularity of online social media networks such as Weibo and Twitter have made the dissemination of information more rapid, extensive and convenient, which has provided new platforms and channels for the generation, dissemination and influence of fake news, and has become a breeding ground for it. Compared with traditional media, online media spread faster, which aggravates the speed and scope of the spread of fake news. The Internet also provides an environment of anonymity and virtuality, which allows people to express their views and disseminate information more freely. This anonymity and virtuality makes the dissemination of fake news more convenient, while also increasing the possibility that the makers of fake news can evade responsibility and traceability.

The massive amount and diversity of information in the network era make people face information overload and screening difficulties. When acquiring information, it is often easy to be misled by fake news, which is likely to have a serious impact on people’s lives. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, rumors about a nationwide lockdown in the United States led to panic buying of groceries and toilet paper, which disrupted supply chains, widened the supply-demand gap, and increased food insecurity among socio-economically disadvantaged and other vulnerable populations [

1]. Such incidents illustrate how social media platforms like Twitter (now X) and Weibo can accelerate the diffusion of misinformation through rapid reposting and algorithmic amplification. Studies have shown that false news on Twitter spreads “farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly” than true news [

2], highlighting the urgent need for automated fake news detection on these platforms. To curb the timely spread of fake news, automatic detection methods have been introduced and have emerged as a critical task in the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP).

Fake news may take different characteristics and forms across different social networking platforms and domains. Many early research works on fake news detection have been devoted to identifying fake news by extracting text features and employing machine learning techniques such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) [

3], Random Forest [

4] and Decision Tree [

5]. These methods can identify fake news to some extent. However, they mainly rely on feature engineering, which is usually data-dependent and cannot handle emerging fake news. As a result, these models often suffer from weak generalization ability and poor robustness.

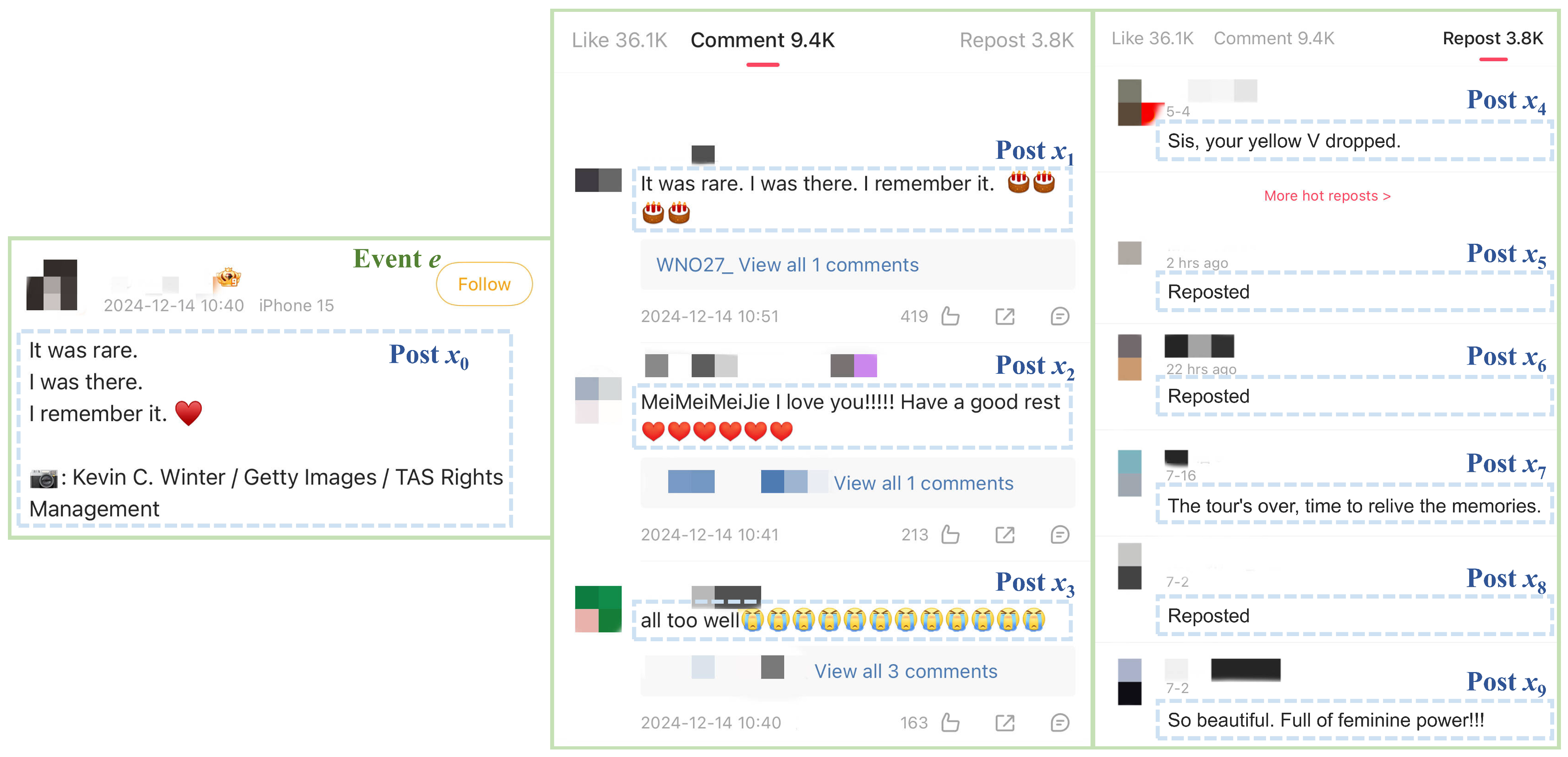

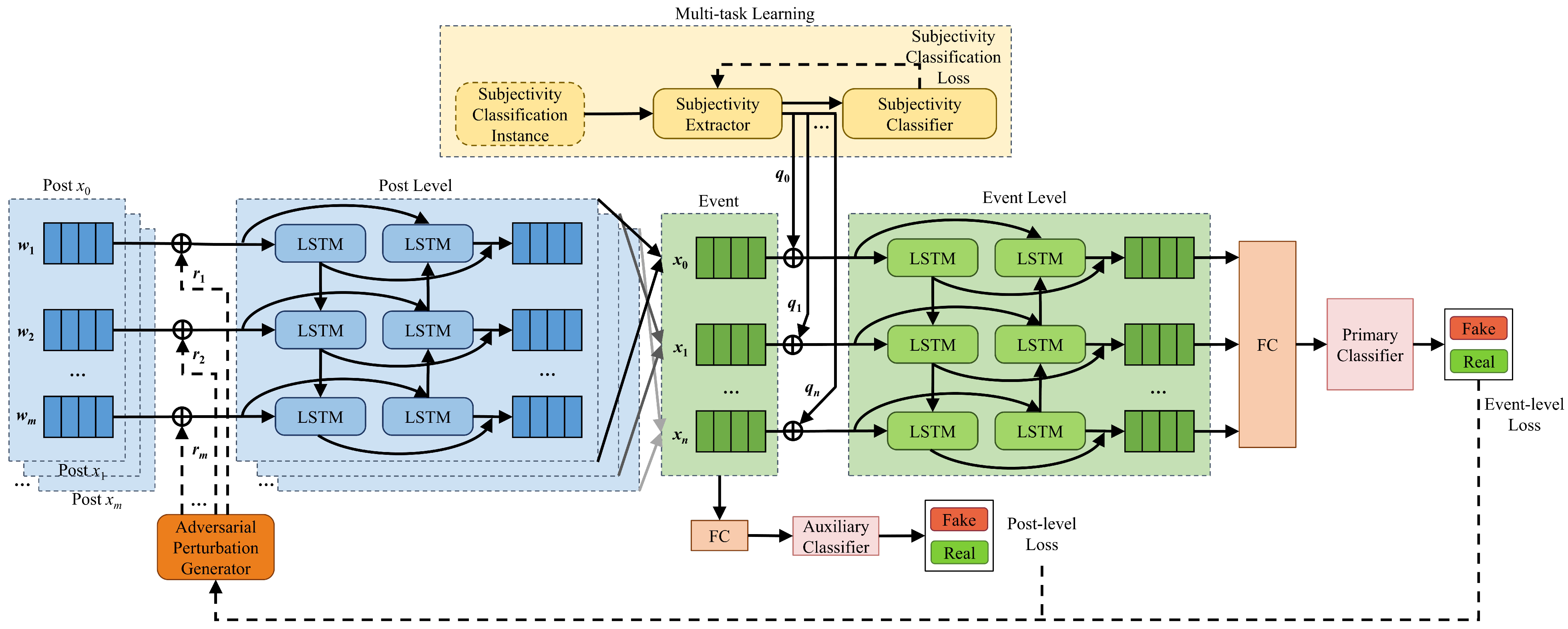

To this end, a new language detection model is designed to enhance the topic adaptivity and robustness of the automatic fake news detection model. A hierarchical architecture is constructed to divide the training data into a post level and an event level. The post level contains the source message post along with all the replies and retweets, while an event in the event level is defined as a collection of a source message post and its replies and retweets. By training the input data separately on these two hierarchies, in order to improve the cross-topic robustness of the model.

Adversarial training is applied at the post level, where the model is exposed to a variety of adversarial samples during training. Adversarial training enables the model to learn how to recognize and respond to these samples, thus improving its robustness and generalization ability.

References [

6,

7,

8,

9] discuss the psychological activities involved when people post fake news and disseminate fake news on online social media. These studies reveal the important role of subjectivity and objectivity of information in identifying fake news. The subjectivity and objectivity of information refers to the presence of words that contain strong personal feelings in the information. On social media platforms, in order to make fake news more misleading, its publishers often adopt an objective tone that mimics authentic information [

8], whereas people who do not believe in the fake news or who are aware of the truth tend to refute the fake news with subjective comments in which emotional attitudes are evident [

9]. Reference [

10] further validates the reliability of the findings of the appeal study by introducing personal emotional information.

Inspired by the researches [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10], a multi-task learning module is added to the event level of the model. This module helps the model to understand the external knowledge related to the subjectivity and objectivity of the information and enables the HAMFD model to capture the subjectivity and objectivity of the information in the post texts. External knowledge can guide the model to learn in a more logical direction, thereby improving the generalization ability of the model. This helps the model to perform better on new data and not just achieve a state of fit on the training data.

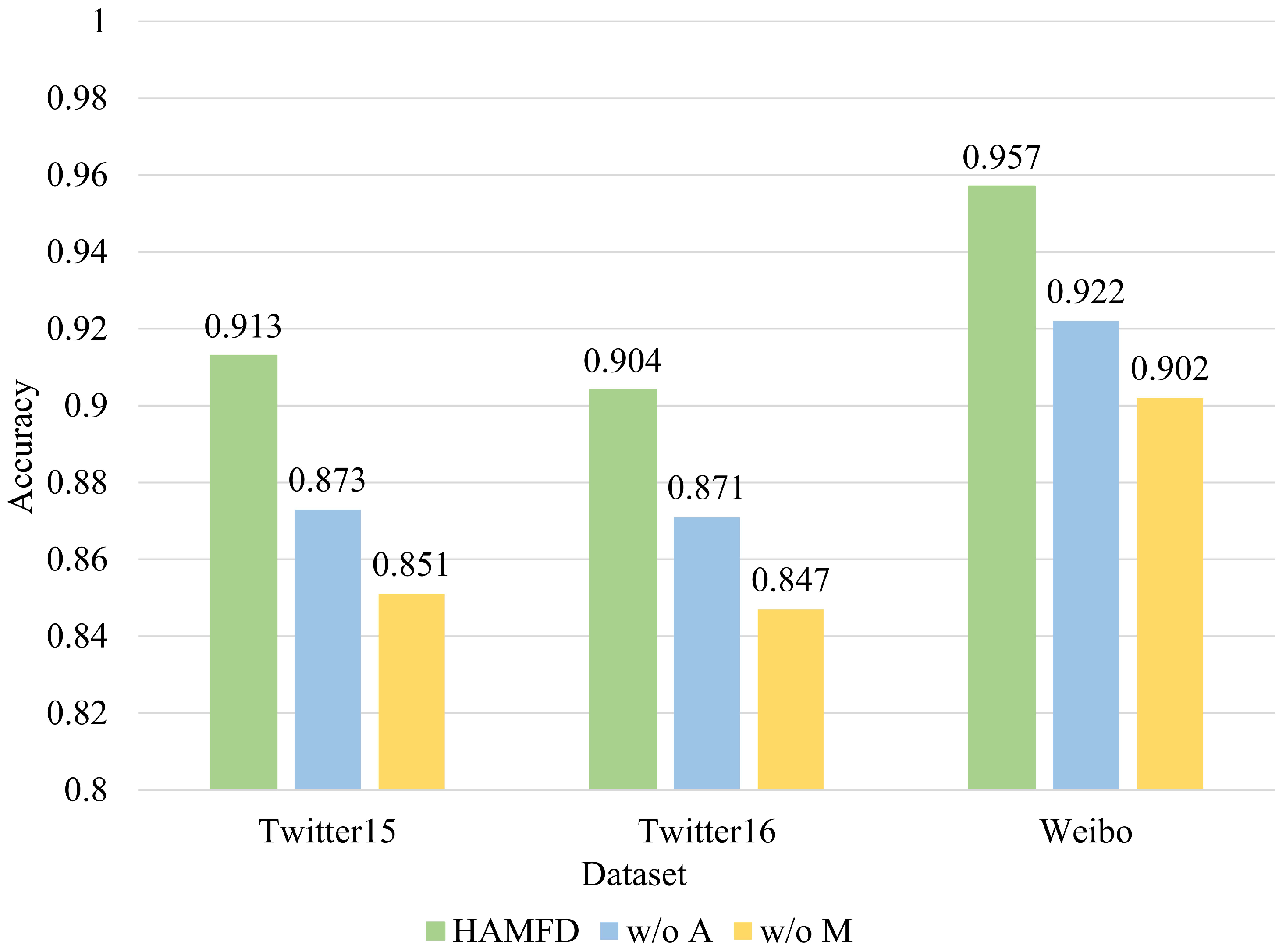

In this study, adversarial training and multi-task learning are applied to the post level and event level of the model, respectively. The post loss and event loss are obtained by setting the auxiliary classifier and the main classifier. The two losses are combined to obtain the adversarial perturbation parameters, which are fed into the post level to enhance the robustness and generalization ability of the model. External knowledge related to the subjectivity and objectivity of information is introduced through multi-task learning to enhance the robustness across topics of the model.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- 1.

This work introduces a hierarchical approach that applies adversarial training at the post level and multi-task learning at the event level.

- 2.

The problem of poor robustness and weak topic adaptive ability of the fake news detection model are addressed through the external knowledge related to the subjectivity and objectivity of information introduced by the adversarial training and multi-task learning modules.

- 3.

It is proved through experiments that the proposed method achieves the effect of enhancing the robustness and topic adaptive ability of the model, and the proposed model outperforms the current state-of-the-art models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.; methodology, Y.S.; software, Y.S.; validation, Y.S. and D.Y.; formal analysis, Y.S.; investigation, Y.S.; resources, Y.S.; data curation, Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.S. and D.Y.; visualization, Y.S.; supervision, D.Y.; project administration, D.Y.; funding acquisition, D.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62377009).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The Twitter15, Twitter16, and Weibo datasets are available from

https://www.dropbox.com/s/46r50ctrfa0ur1o/rumdect.zip?dl=0 (accessed on 18 November 2025). The English subjectivity dataset is available at

http://www.cs.cornell.edu/people/pabo/movie-review-data/ (accessed on 18 November 2025). The Chinese subjectivity dataset used in this study was derived by translating and manually refining the English subjectivity dataset; the processed version is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, which have greatly improved the quality of this manuscript. The authors also acknowledge the support of colleagues from the research group for their constructive discussions during the course of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| HAMFD | Hierarchical Adversarial Multi-task Fake News Detection |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| HMM | Hidden Markov Model |

| CRF | Conditional Random Field |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| ERD | Early Rumor Detection |

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Network |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| Acc. | Accuracy |

| Prec. | Precision |

| Rec. | Recall |

| F1 | F1 Score |

| NR | Non-Rumor |

| FR | False Rumor |

| TR | True Rumor |

| UR | Unverified Rumor |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

References

- Tasnim, S.; Hossain, M.M.; Mazumder, H. Impact of Rumors and Misinformation on COVID-19 in Social Media. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2020, 53, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vosoughi, S.; Roy, D.; Aral, S. The spread of true and false news online. Science 2018, 359, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rosas, V.; Kleinberg, B.; Lefevre, A.; Mihalcea, R. Automatic Detection of Fake News. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.07104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Cha, M.; Jung, K.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y. Prominent Features of Rumor Propagation in Online Social Media. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 13th International Conference on Data Mining, Dallas, TX, USA, 7–10 December 2013; pp. 1103–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Yu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, M. Automatic Detection of Rumor on Sina Weibo. In Proceedings of the MDS ’12: Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD Workshop on Mining Data Semantics, Beijing, China, 12–16 August 2012; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Einwiller, S.A.; Kamins, M.A. Rumor Has It: The Moderating Effect of Identification on Rumor Impact and the Effectiveness of Rumor Refutation. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 2248–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFonzo, N.; Bourgeois, M.J.; Suls, J.; Homan, C.; Stupak, N.; Brooks, B.P.; Ross, D.S.; Bordia, P. Rumor clustering, consensus, and polarization: Dynamic social impact and self-organization of hearsay. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 49, 378–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Huang, H.; Su, B.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, B. Dynamic 8-state ICSAR rumor propagation model considering official rumor refutation. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2014, 415, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosnow, R.L. Inside rumor: A personal journey. Am. Psychol. 2016, 46, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Huang, Z.; Li, B.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, Z.; Li, D. SIFTER: A Framework for Robust Rumor Detection. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2022, 30, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, C.; Mendoza, M.; Poblete, B. Information credibility on Twitter. In Proceedings of the WWW ’11: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on World Wide Web, Hyderabad, India, 28 March–1 April 2011; pp. 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Nourbakhsh, A.; Li, Q.; Fang, R.; Shah, S. Real-time rumor debunking on Twitter. In Proceedings of the CIKM ’15: Proceedings of the 24th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Melbourne, Australia, 18–23 October 2015; pp. 1867–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fan, Z.; Zheng, J.; Liu, Q. An improving deception detection method in computer-mediated communication. Networks 2012, 7, 1811–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Yang, S.; Zhu, K.Q. False rumors detection on Sina Weibo by propagation structures. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 31st International Conference on Data Engineering, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 13–17 April 2015; pp. 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosoughi, S. Automatic Detection and Verification of Rumors on Twitter; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vosoughia, S.; Mohsenvand, M.N.; Roy, D. Rumor Gauge: Predicting the veracity of rumors on Twitter. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2017, 11, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubiaga, A.; Liakata, M.; Procter, R.; Bontcheva, K.; Tolmie, P. Towards Detecting Rumours in Social Media. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1504.04712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pi, D.; Chen, J.; Xie, M.; Cao, J. Rumor detection based on propagation graph neural network with attention mechanism. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 158, 113595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Vo, B.; Jo, J.; Nguyen, Q.V.H. JUDO: Just-in-time rumour detection in streaming social platforms. Inf. Sci. 2021, 570, 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Ma, J.; Yeo, C.K. BCMM: A novel post-based augmentation representation for early rumour detection on social media. Pattern Recognit. 2021, 113, 107818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Meng, J. PostCom2DR: Utilizing information from post and comments to detect rumors. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 189, 116071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Sun, X.; Meng, Q.; Yang, X.; Lee, Y.; Cao, J. Nowhere to Hide: Online Rumor Detection Based on Retweeting Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 35, 4887–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Dou, Z.H.Y.; Yan, Y. Rumor detection on social media through mining the social circles with high homogeneity. Inf. Sci. 2023, 642, 119083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, T.; Xiao, X.; Xu, T.; Zhao, P.; Huang, W.; Rong, Y.; Huang, J. Rumor Detection on Social Media with Bi-Directional Graph Convolutional Networks. Proc. Aaai Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelke, S.; Attar, V. Rumor Detection in Social Network Based on User, Content and Lexical Features. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 17347–17368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Dan, Z.; Dong, F.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, Y. A Rumor Detection Method Based on Adaptive Fusion of Statistical Features and Textual Features. Information 2022, 13, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, J.; Socher, R.; Manning, C. GloVe: Global Vectors for Word Representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014; pp. 1534–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Gao, W.; Mitra, P.; Kwon, S.; Jansen, B.J.; Wong, K.F.; Cha, M. Detecting rumors from microblogs with recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the 25th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), New York, NY, USA, 9–15 July 2016; pp. 3818–3824. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/proceedings/10.5555/3061053 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Pang, B.; Lee, L. A sentimental education: Sentiment analysis using subjectivity summarization based on minimum cuts. In Proceedings of the ACL ’04: Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics, Barcelona, Spain, 21–26 July 2004; pp. 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Gao, W.; Wei, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wong, K.-F. Detect Rumors Using Time Series of Social Context Information on Microblogging Websites. In Proceedings of the CIKM ’15: Proceedings of the 24th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Melbourne, Australia, 18–23 October 2015; pp. 1751–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Gao, W.; Wong, K.F. Detect Rumors in Microblog Posts Using Propagation Structure via Kernel Learning. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 July–4 August 2017; pp. 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Gao, W.; Wong, K.F. Rumor Detection on Twitter with Tree-structured Recursive Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Melbourne, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 1980–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.F.B. Early Detection of Fake News on Social Media Through Propagation Path Classification with Recurrent and Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-18), New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; pp. 354–361. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.5555/3504035.3504079 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).