1. Introduction

E-government serves multiple purposes, including enhancing administrative efficiency by streamlining processes, promoting democratic governance by facilitating citizen participation and feedback mechanisms, and fostering trust between citizens, the private sector, and governments through increased transparency and accountability [

1]. However, achieving these goals has been difficult due to accessibility problems in many e-government websites [

2]. This has led to increasing demands for assessing the accessibility of e-government websites, which are widely recognized as the main way for governments to interact with citizens [

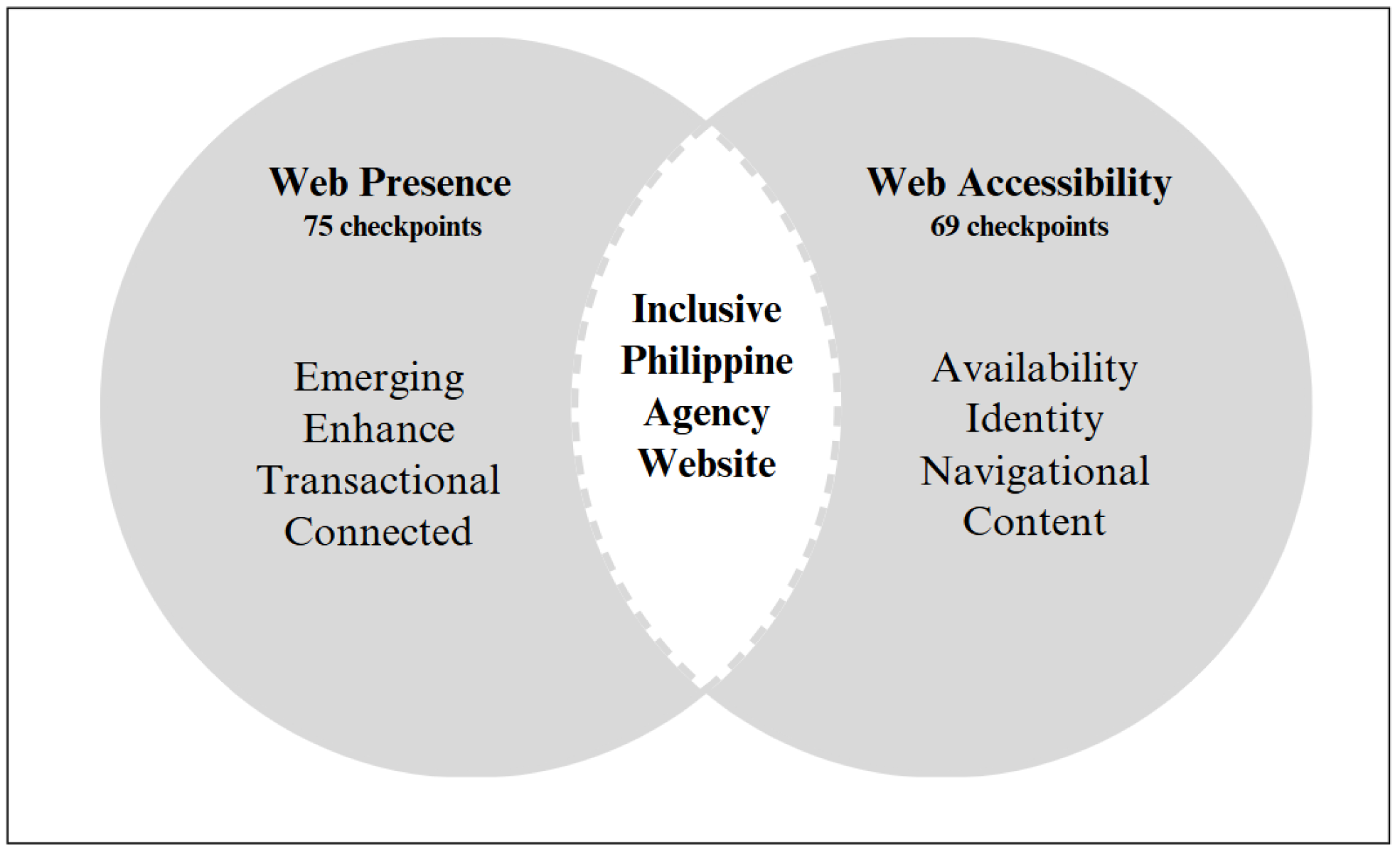

3]. Several studies have investigated the content of government websites, focusing specifically on their web presence and web accessibility [

4,

5,

6,

7]. These studies highlight the critical role of accessible web design in promoting equal opportunities for all users. Research indicates that implementing accessible design features on government websites not only ensures that individuals with disabilities can access information and services but also enhances overall accessibility for all visitors. By incorporating accessible web design principles, government websites can better serve the diverse needs of their citizens and promote inclusivity [

8]. Implementing accessible design features not only accommodates the needs of individuals with disabilities but also enhances the overall user experience for all visitors [

9]. A strong web presence and web accessibility are of utmost importance in effectively serving e-citizens. This ensures that citizens can easily access information and services, fostering transparency and accountability in governance [

10,

11].

Government websites can be checked for accessibility compliance by following Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0 standards, which include providing text alternatives, ensuring keyboard accessibility, and making content easy to understand [

4,

12,

13]. Furthermore, web accessibility ensures that individuals with disabilities can equitably perceive, comprehend, navigate, and engage with websites and digital tools [

14]. By adhering to the WCAG standards and considering accessibility principles, government websites can enhance the overall user experience and ensure that all citizens, regardless of abilities, can effectively access information and utilize online services. Various approaches have been utilized to conduct these studies, encompassing both automated and manual approaches. According to [

15], automated tools can be just as effective as manual methods in pinpointing web accessibility problems. Most studies used automated methods, utilizing popular tools such as the Web Accessibility Evaluation (WAVE) Tool, Google Lighthouse, and Test d’Accessibilitat Web (TAW) [

16,

17,

18,

19].

In the Philippines, the legal basis of web accessibility can be traced back to several laws and policies. The most notable among these is the Republic Act No. 7277, or the Magna Carta for Persons with Disabilities (PWDs) [

20]. This law mandates the government to ensure that PWDs are provided with equal opportunities, particularly in the field of education, employment, and accessibility to public facilities and services, including information and communication technology. The National Council on Disability Affairs issued the Implementing Rules and Regulations of the Magna Carta, which explicitly states that “all government websites shall comply with the guidelines on web accessibility” [

21]. Additionally, the Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT) issued Memorandum Circular 004 (2017), a policy that provides guidelines on the implementation of web accessibility in government websites [

22]. The memorandum circular provides specific guidelines for achieving web accessibility, including the use of alternative text for non-text content, the provision of captions and transcripts for multimedia content, and the use of descriptive links and headings. It also requires government agencies to conduct regular accessibility audits of their websites and web-based applications to ensure compliance with the WCAG 2.0 Level AA. Moreover, the memorandum circular mandates the establishment of a web accessibility compliance team within each government agency, responsible for ensuring compliance with web accessibility guidelines and conducting regular accessibility audits of the agency’s website [

23]. These laws and policies serve as the legal basis for the implementation of web accessibility standards in the Philippines, particularly for the benefit of PWDs. According to the 2010 Census of Population and Housing in the Philippines, 1.44 million individuals, or 1.57% of the 92.1 million household population, have a disability [

24,

25].

Despite these policies, the overall accessibility of the Philippine government websites remains a concern. According to the United Nations E-Government Development Index, the Philippines ranks 73rd globally in e-government development [

26]. This ranking reflects the country’s progress in digital governance but also underscores the need for further improvement in accessibility. In this context, evaluating the accessibility of government websites is essential to determine whether accessibility challenges stem from design and compliance issues or broader factors related to the digital divide. This ensures that web accessibility remains essential in promoting inclusivity and equal access to government services and digital resources. Governments must prioritize accessibility improvements to accommodate the needs of persons with disabilities, thereby fostering a more inclusive digital environment.

As such, this study aims to contribute to the existing knowledge by evaluating the web presence and accessibility of e-government websites in the Philippines. This endeavor is particularly significant considering the limited understanding of e-government website accessibility within the country. Ensuring equitable access to government services for all citizens, including those with visual, auditory, dexterity, and cognitive impairments, is imperative. This evaluation is important because it will help identify any barriers or challenges that may exist and provide recommendations for improving accessibility. Having an accessible website supports government agencies in their commitment to serving all members of the public equally.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

The evaluation of web accessibility for government agencies in the Philippines highlights critical areas for improvement in compliance with the Government Website Template Design guidelines and the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0 established by the World Wide Web Consortium.

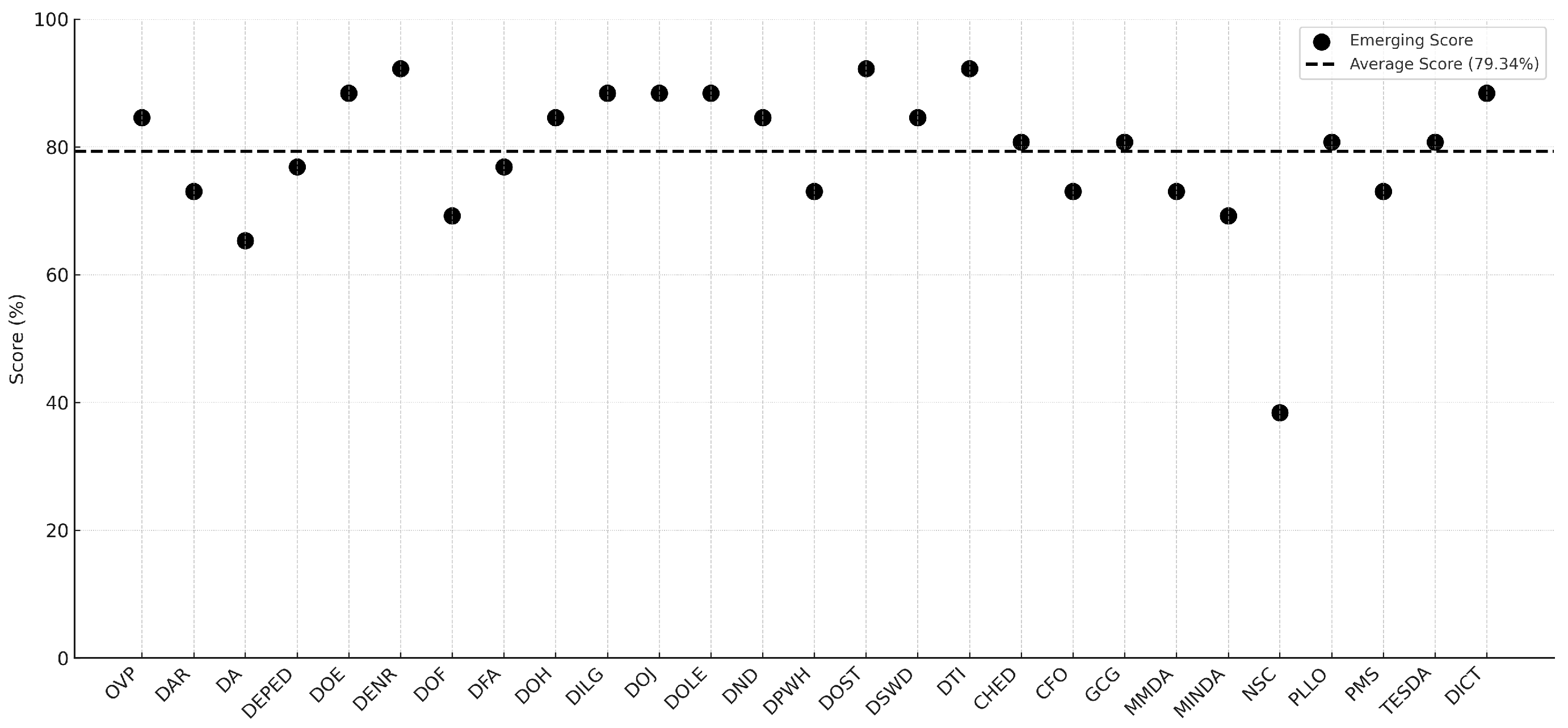

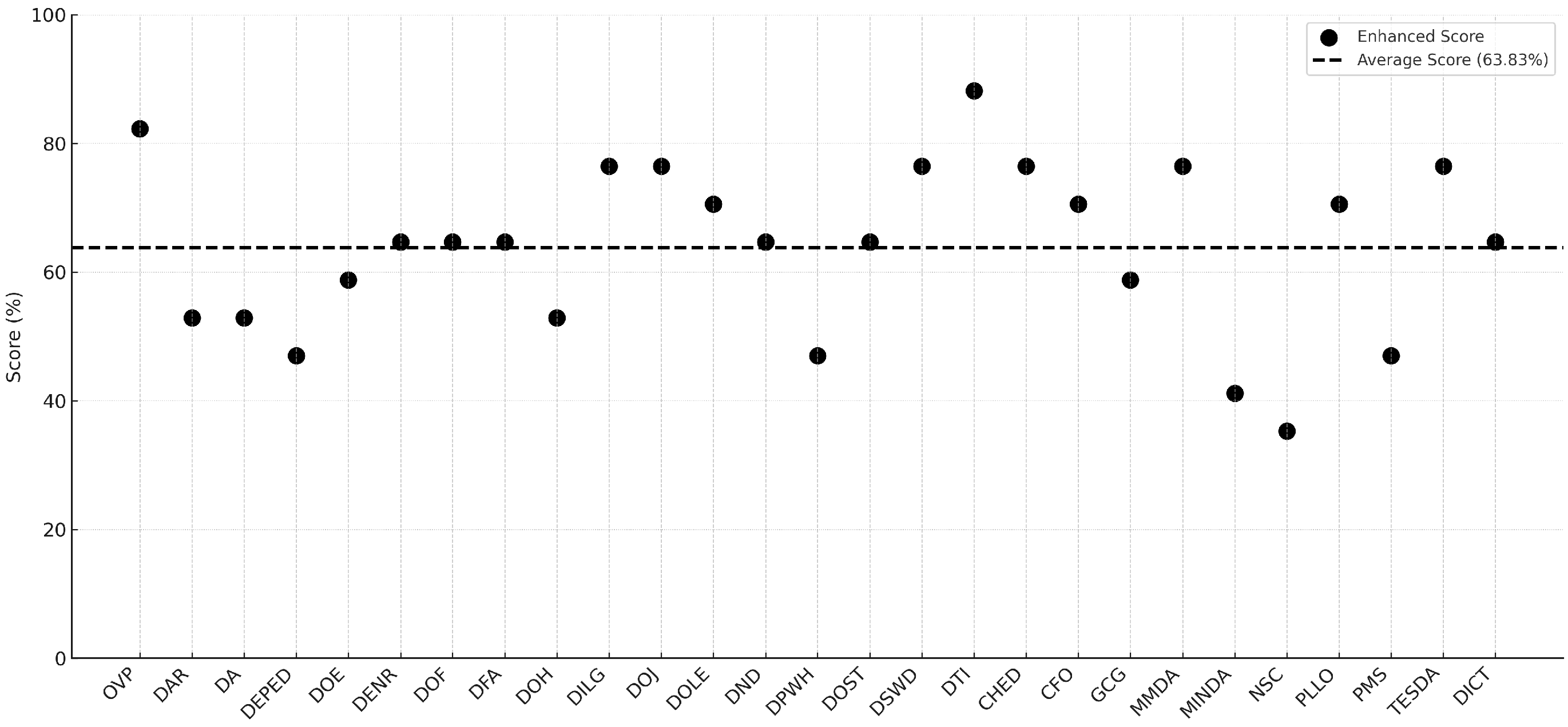

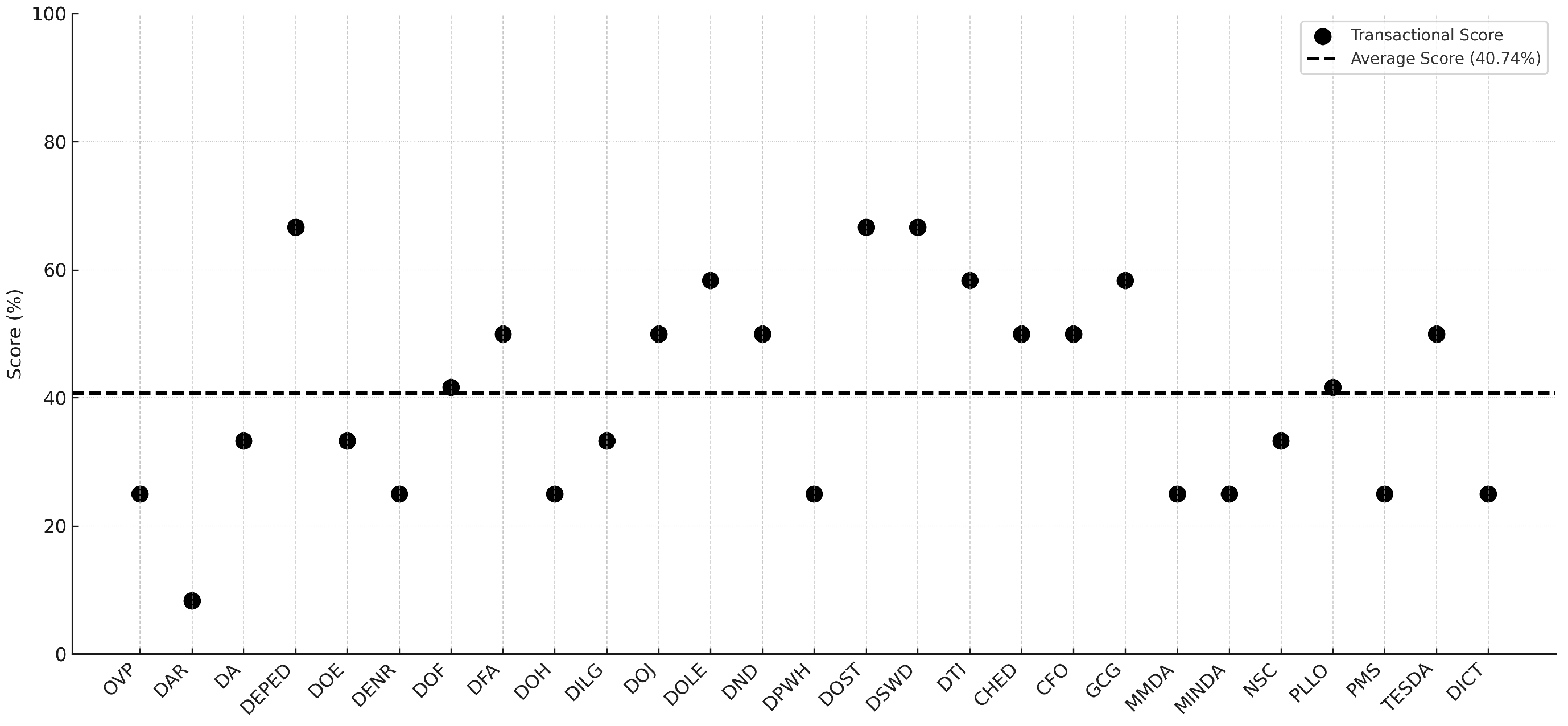

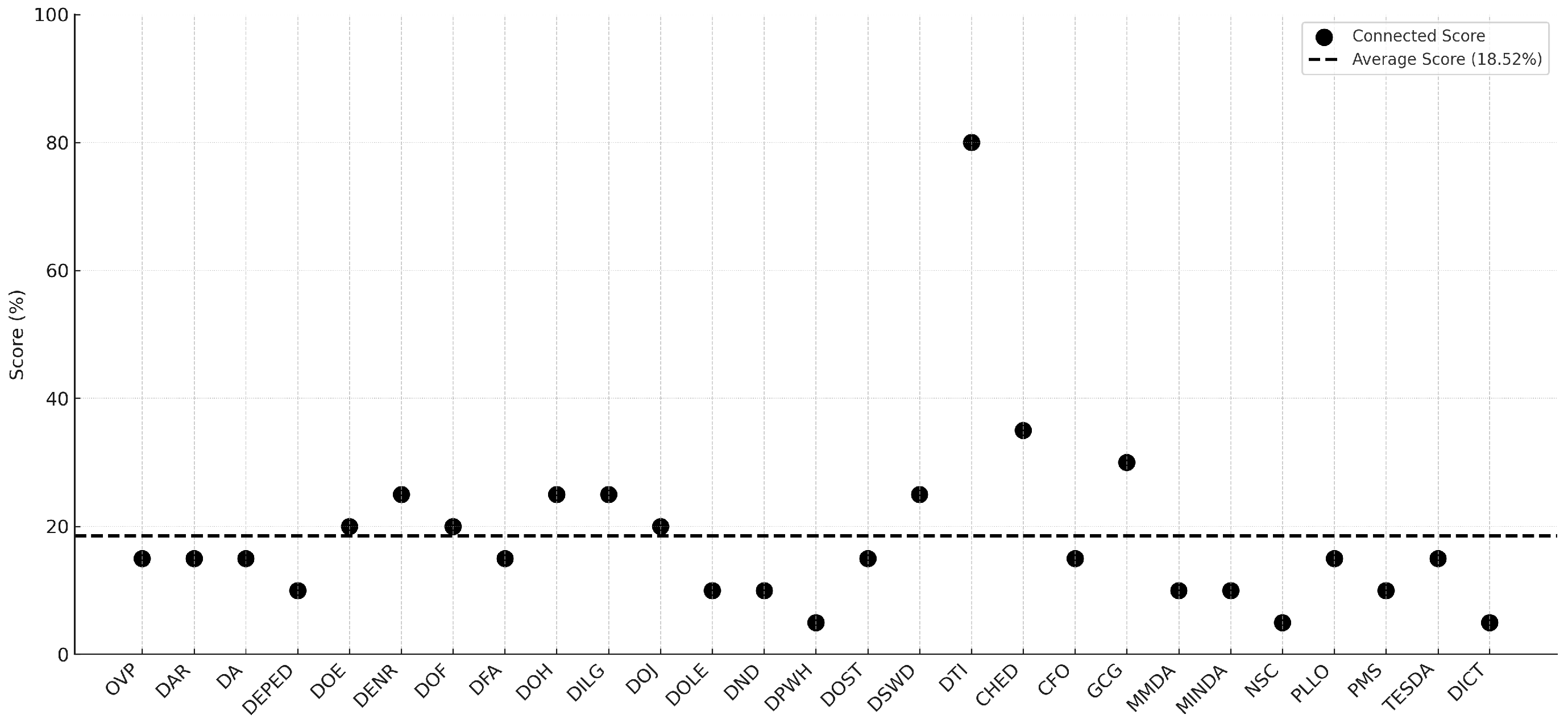

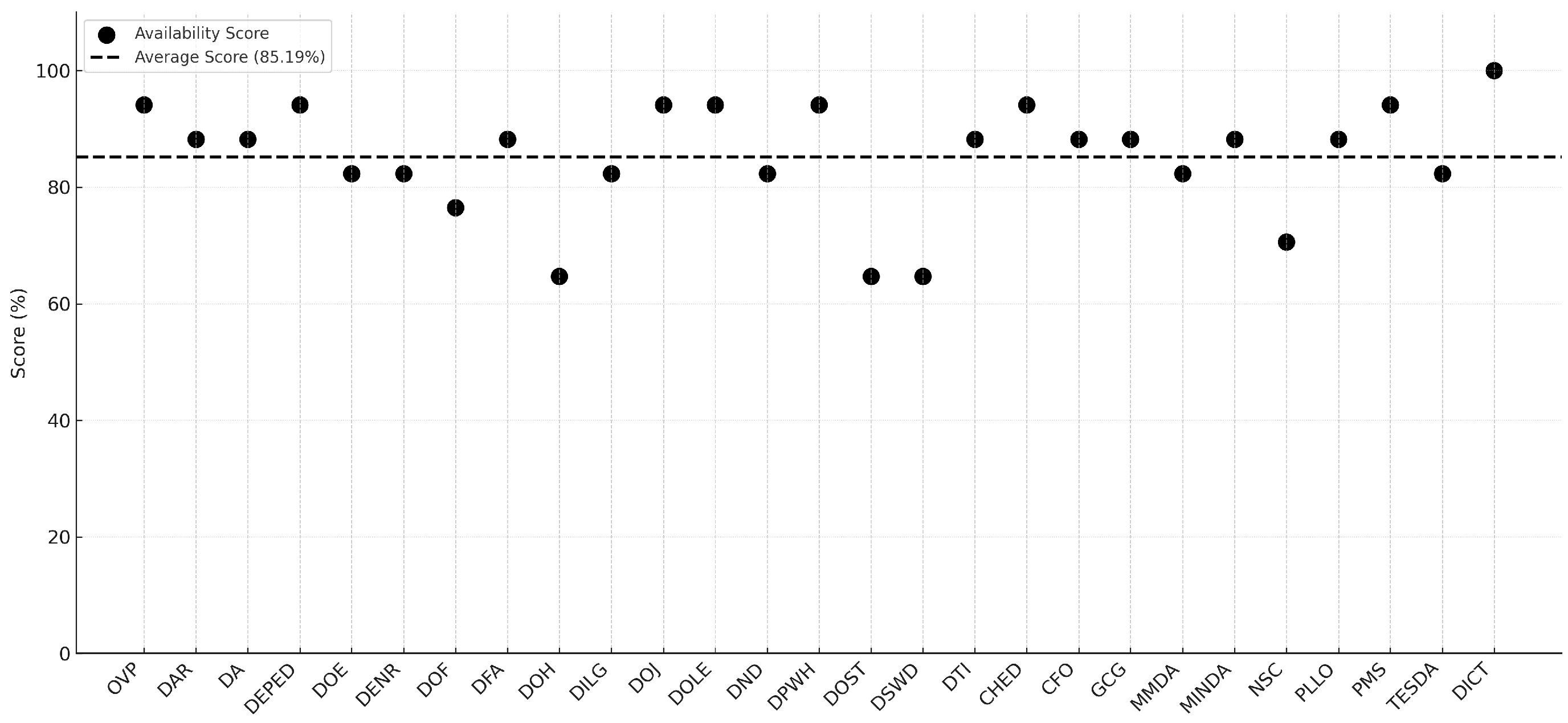

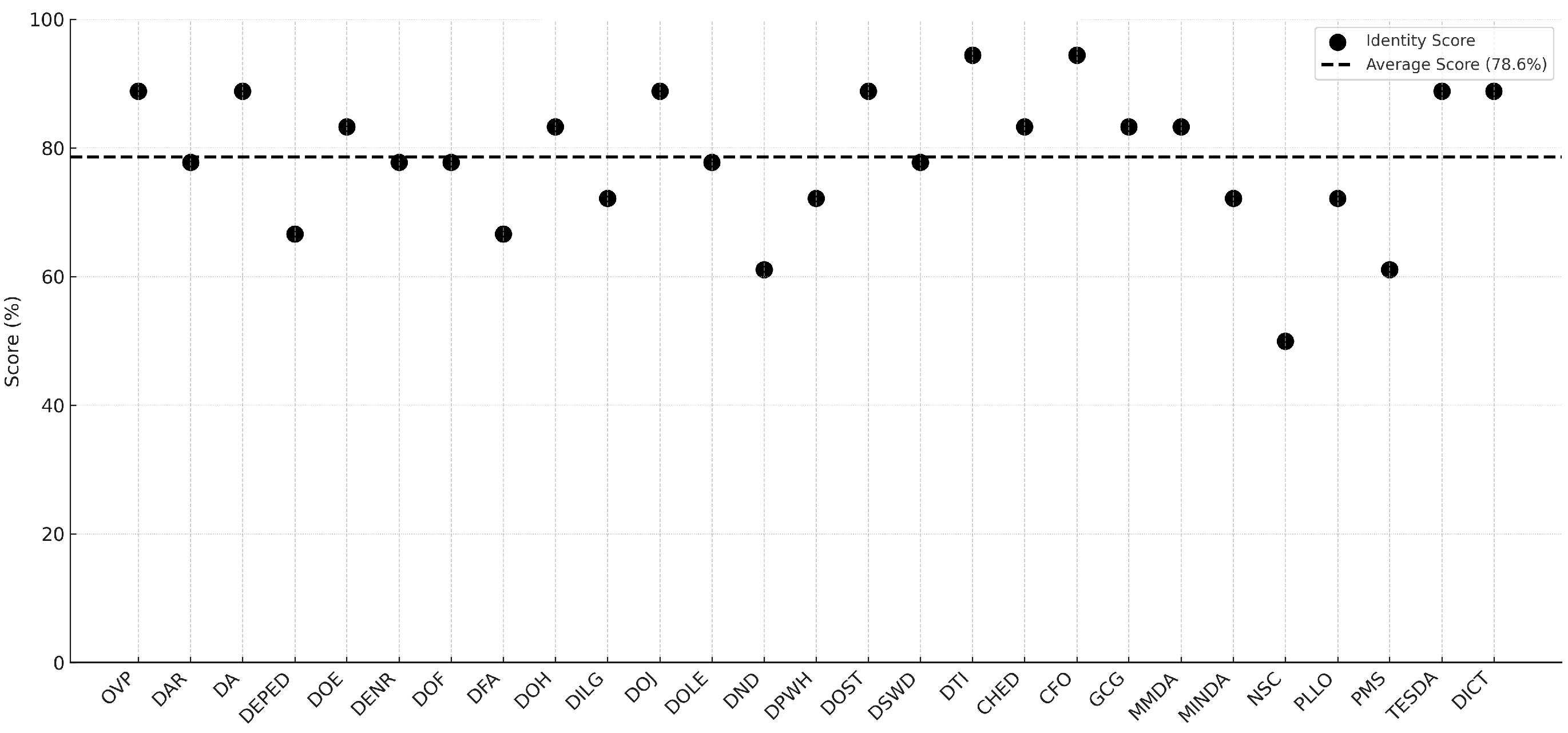

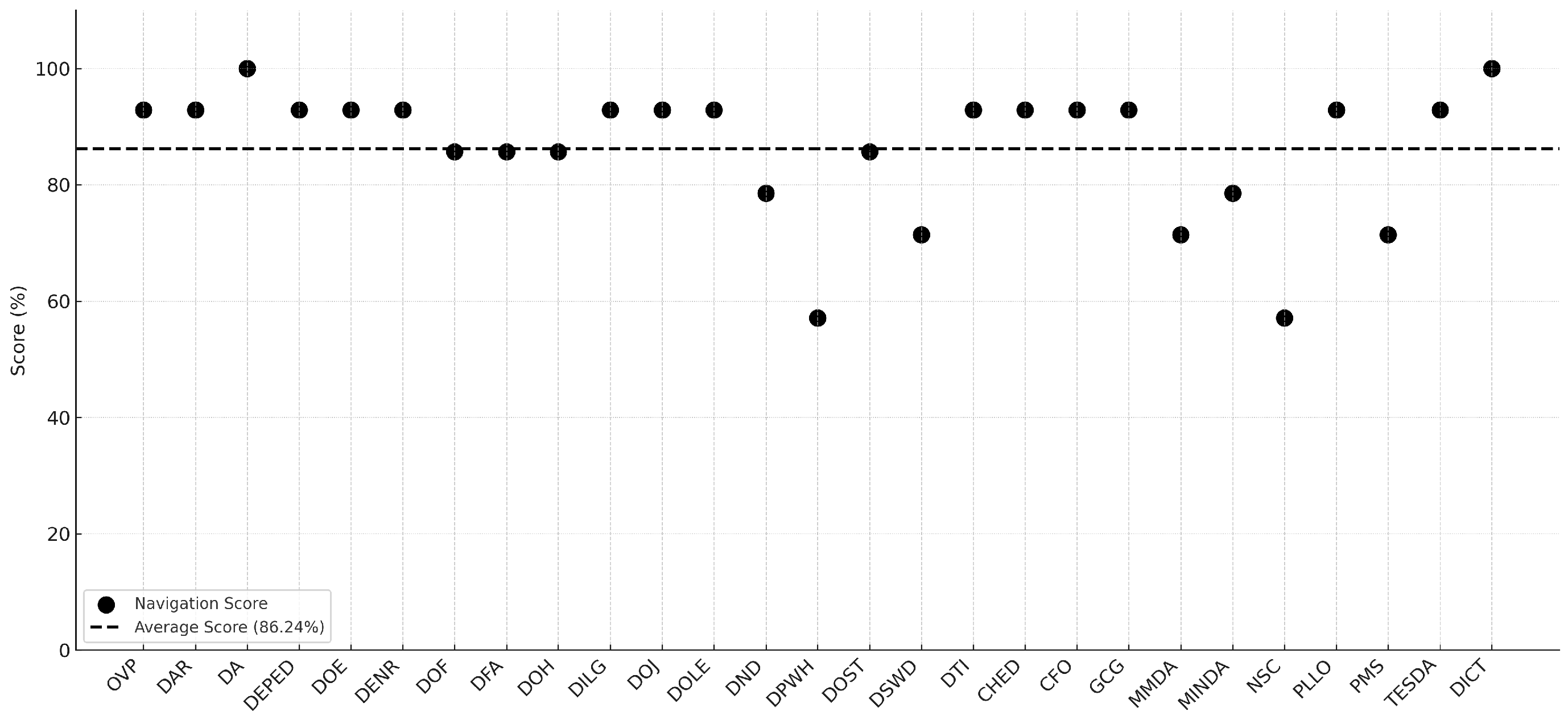

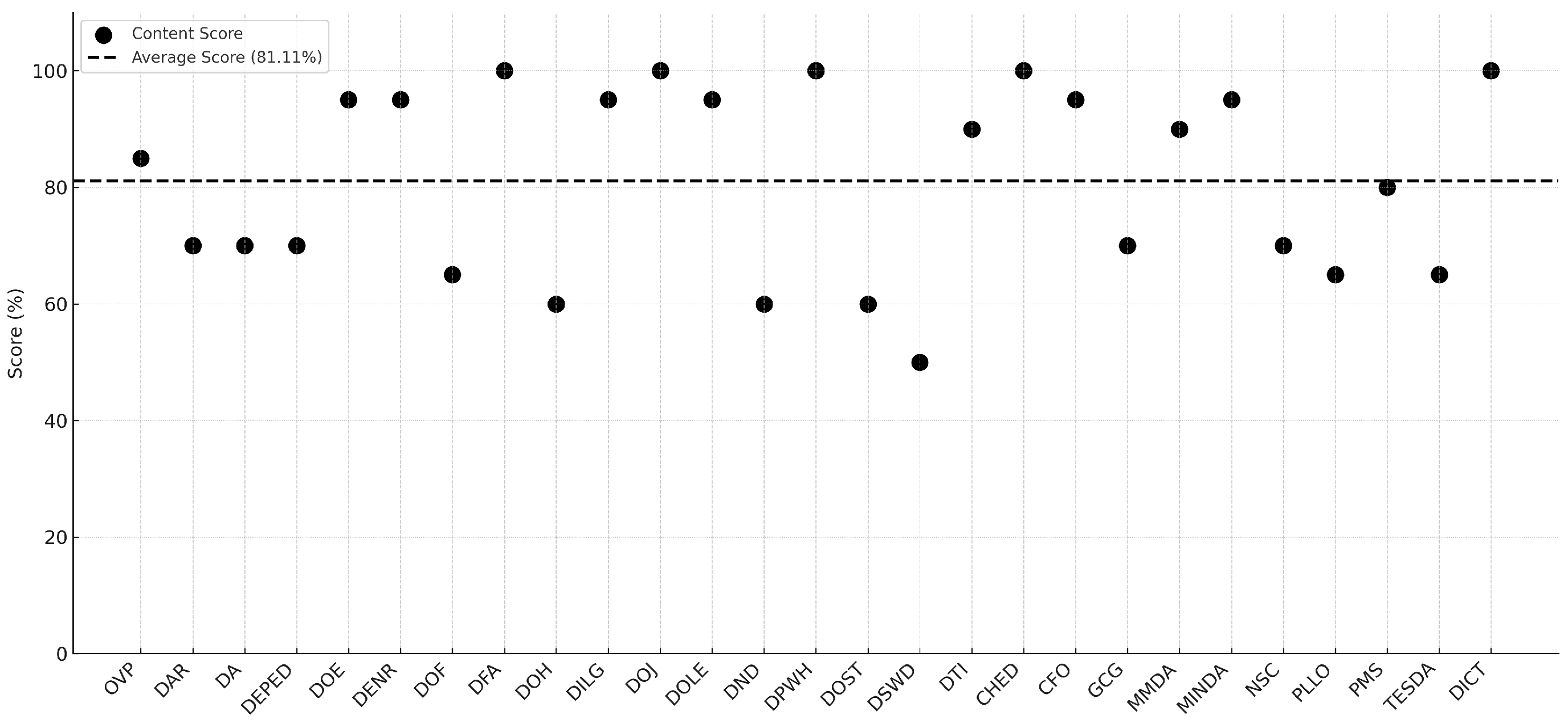

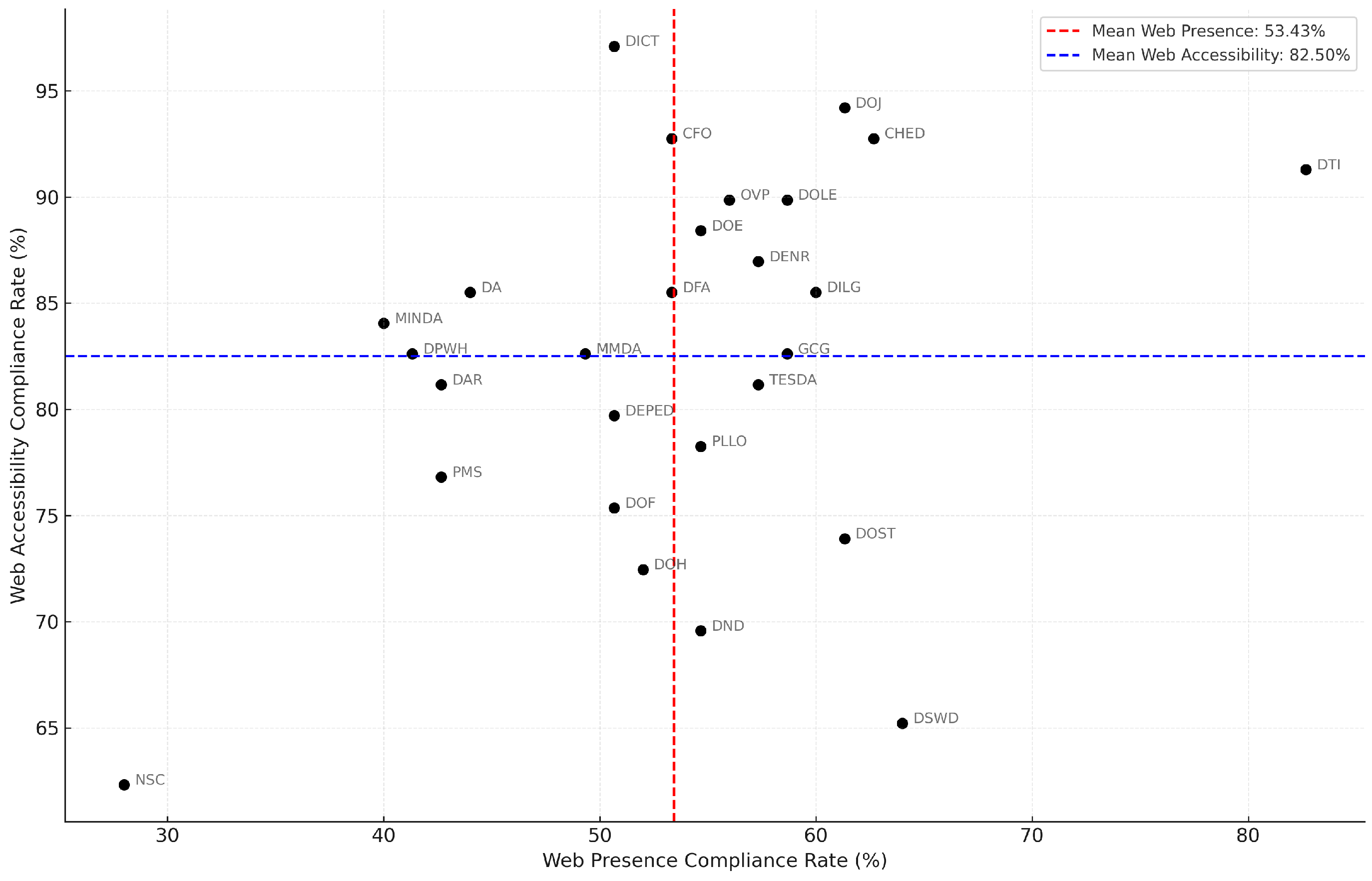

The findings revealed significant discrepancies between web presence and web accessibility. Compliance rates for web presence ranged from 28% to 82.67%, with an average of 53.43%. Notable gaps were found in the transactional and connected stages, where engagement and interactive services should be more robust. To improve their web presence, government agencies must focus on addressing low-compliance areas, such as missing ALT tags in the availability section, incomplete contact information in the identity section, unclear navigation features in the navigation section, and inadequate meta descriptions or form labels in the content section. The connected web presence stage, which represents a fully integrated digital ecosystem, showed a concerning 0% compliance rate, highlighting significant issues with system interoperability and seamless online services. Overall, the compliance rates for web presence across all government agencies remain critically low, underscoring the urgent need to enhance integration, data sharing, and interoperability.

In contrast, web accessibility scored higher, with compliance rates ranging from 62.32% to 97.1% and an average of 82.5%. This suggests that while significant progress has been made in ensuring websites are accessible to users, there are still areas in need of improvement. Some government agencies in the Philippines have already adopted mobile integration to enhance service accessibility and citizen engagement. However, despite these advancements, many agencies still lack fully responsive designs or dedicated mobile applications, as reflected in the navigation section of the web accessibility evaluation. This underscores the need for government agencies to expand their digital strategies, ensuring seamless mobile responsiveness and multi-platform accessibility to cater to a diverse and growing digital user base.

A comparative analysis of web presence and web accessibility further underscores this need. Although web accessibility scores remain high, web presence compliance is relatively lower. This indicates that many government agencies have prioritized accessibility improvements but may still need to strengthen their digital services and visibility. A well-structured and user-friendly website is crucial, but without expanded online services, mobile accessibility, and transactional features, the full potential of digital governance remains underutilized.

To fully optimize government websites, agencies must invest in digital transformation efforts, mobile integrations, enhanced interoperability, and strengthened online service capabilities. Future studies are directed to aid government agencies to adopt accessible design principles, conduct regular accessibility audits, collaborate with disability advocacy groups, and integrate assistive technologies into their website evaluation processes to create a more inclusive and efficient digital government ecosystem.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B.J. and A.G.; methodology, P.B.J. and J.J.E.; validation, P.B.J. and J.J.E.; formal analysis, P.B.J., J.J.E. and J.B.; investigation, P.B.J., J.B., J.J.E., N.B. and A.R.A.; resources, P.B.J., J.B., J.J.E. and A.G.; data curation, P.B.J. and J.J.E.; writing—original draft, P.B.J., J.J.E., J.B. and A.G.; writing—review and editing, P.B.J., J.J.E., J.B. and A.G.; visualization, P.B.J. and J.J.E.; supervision, P.B.J. and A.G.; project administration, P.B.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research, including the article processing charge (APC), was funded by the Mindanao State University-Iligan Institute of Technology through the Office of Research Management, under the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Enterprise SO# 00503-2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported and funded by Mindanao State University-Iligan Institute of Technology (MSU-IIT). Their generous contribution was instrumental in enabling us to carry out this study and achieve the research objectives. We express our sincere gratitude to MSU-IIT for their unwavering support in promoting academic excellence and research endeavors. Moreover, while preparing this manuscript, we used ChatGPT (GPT-4o) solely for paraphrasing text to improve clarity and coherence as well as for generating LaTeX code for formatting in Overleaf. However, all analyses, interpretations, and conclusions in this manuscript remain the authors’ original work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grigalashvili, V. E-Government and E-Governance: Various or Multifarious Concepts. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Res. 2022, 5, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, J.P.B.; Avila, L.S.; Mag-iba, M.A.J.; Buman-eg, L.D.; Nacpil Jr, E.E.; Dayrit, D.J.A.; Rodelas, N.C. E-Governance: A Critical Review of E-Government Systems Features and Frameworks for Success. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Res. 2023, 7, 2004–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroudi, M.; Alia, M.; Marashdih, A.W. Evaluation of Accessibility and Usability of Higher Education Institutions’ Websites of Jordan. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Systems (ICICS), Irbid, Jordan, 7–9 April 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sakran, H.O.; Alsudairi, M.A. Usability and Accessibility Assessment of Saudi Arabia Mobile E-Government Websites. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 48254–48275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, G.; Kumar, D.; Singh, M. Assessing the Usability, Accessibility, and Mobile Readiness of E-Government Websites: A Case Study in India. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2022, 21, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legaspi, P.E.; Marigza, R.B. Exploring and Assessing Government Website as an Instrument of E-Governance at the Local Government Level in Pangasinan. ASEAN Multidiscip. Res. J. 2021, 9, 126–141. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhsh, M.; Mehmood, A. Web Accessibility for Disabled: A Case Study of Government Websites in Pakistan. In Proceedings of the 2012 10th International Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan, 17–19 December 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.; Al Mutawaa, A.; Al Tamimi, A.; Al Mansouri, M. Assessing the Readiness of Government and Semi-Government Institutions in Qatar for Inclusive and Sustainable ICT Accessibility: Introducing the MARSAD Tool. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malodia, S.; Dhir, A.; Mishra, M.; Bhatti, Z.A. Future of E-Government: An Integrated Conceptual Framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 173, 121102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lujan-Mora, S.; Navarrete, R.; Penafiel, M. Egovernment and Web Accessibility in South America. In Proceedings of the 2014 First International Conference on eDemocracy and eGovernment (ICEDEG), Quito, Ecuador, 24–25 April 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İşeri, E.İ.; Uyar, K.; İlhan, Ü. The Accessibility of Cyprus Islands’ Higher Education Institution Websites. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 120, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csontos, B.; Heckl, I. Accessibility, Usability, and Security Evaluation of Hungarian Government Websites. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2021, 20, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murah, M.Z.; Ahmed, A. Web Assessment of Libyan Government e-Government Services. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2018, 9, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W3C-WAI. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). Available online: https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/wcag/ (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Iannuzzi, N.; Manca, M.; Paternò, F.; Santoro, C. Usability and Transparency in the Design of a Tool for Automatic Support for Web Accessibility Validation. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2024, 23, 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismailova, R.; Inal, Y. Comparison of Online Accessibility Evaluation Tools: An Analysis of Tool Effectiveness. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 58233–58239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañez-Carvajal, C.; Cervera-Mérida, J.F.; Fernández-Piqueras, R. Web Accessibility Evaluation of Top-Ranking University Websites in Spain, Chile, and Mexico. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2021, 20, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgül, Y. Accessibility, Usability, Quality Performance, and Readability Evaluation of University Websites of Turkey: A Comparative Study of State and Private Universities. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2021, 20, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, S.A.; Shehu, I.S.; Bake, P. Accessibility Evaluation and Performance Analysis of e-Government Websites in Nigeria. J. Adv. Inf. Technol. 2016, 7, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabauatan, A.J. The Politics of Inclusion: Perspectives on Persons with Disabilities in Society; Alexis Jose Cabauatan: Santiago City, Philippines, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Susmerano, E.B.; Yamada, K. Revisiting Auxiliary Social Services for Persons with Disability: The Philippines Case. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2022, 31, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvio, K.B.V. Extending the Evaluation on Philippine E-Government Services on its Accessibility for Disabled Person. In Proceedings of the 2020 Fourth World Conference on Smart Trends in Systems, Security and Sustainability (WorldS4), London, UK, 27–28 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DICT. DICT Memo Circular 2019. Available online: https://www.pwag.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/DICT-Memo-Circular-2019-04-txt-format.txt (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Authority, P.S. Persons with Disability in the Philippines: Results from the 2010 Census. Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/content/persons-disability-philippines-results-2010-census (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Red, G.V.; Palaoag, T.D.; Naz, V.A. Creating a Framework for Care Needs Hub for Persons with Disabilities and Senior Citizens. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations UN E-Government Knowledgebase. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/Data/Country-Information/id/134-Philippines (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Khasawneh, M.A. Digital Inclusion: Analyzing Social Media Accessibility Features for Students with Visual Impairments. Stud. Media Commun. 2023, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Mulet, J.; Sorita, C.; Oriola, B.; Serrano, M.; Jouffrais, C. Remote Graphic-Based Teaching for Pupils with Visual Impairments: Understanding Current Practices and Co-designing an Accessible Tool with Special Education Teachers. Proc. ACM-Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2022, 6, 538–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, N.A. Now You See It: Creating Accessible Online Content for the Blind/Visually Impaired; The University of West Florida: Pensacola, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, D.; Rajput, T.; Rajkumar, A.J.; Lazar, J.; Jain, R.; Morariu, V.I.; Manjunatha, V. Development and Evaluation of a Tool for Assisting Content Creators in Making PDF Files More Accessible. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. 2022, 15, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, A. Low Vision and Color Blindness. In Practical Web Accessibility: A Comprehensive Guide to Digital Inclusion; Ashley Firth: London, UK, 2024; pp. 57–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ohshiro, K.; Cartwright, M. How People Who Are Deaf, Deaf, and Hard of Hearing Use Technology in Creative Sound Activities. In Proceedings of the 24th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Athens, Greece, 23–26 October 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.M.; Lu, C.; Lu, Z.; Carrington, P.; Truong, K.N. An Exploration of Captioning Practices and Challenges of Individual Content Creators on YouTube for People with Hearing Impairments. Proceedings ACM-Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2022, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas Pereira, L.; Coelho, J.; Rodrigues, A.; Guerreiro, J.; Guerreiro, T.; Duarte, C. Authoring Accessible Media Content on Social Networks. In Proceedings of the 24th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Athens, Greece, 23–26 October 2022; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Malalasekara, S.A.P. Breaking Barriers to Computer Accessibility: A Wireless Mouse System for People with Hand Disabilities. Master’s Thesis, Metropolia University of Applied Sciences, Vantaa, Finland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gartland, S.; Flynn, P.; Carneiro, M.A.; Holloway, G.; Fialho, J.d.S.; Cullen, J.; Hamilton, E.; Harris, A.; Cullen, C. The State of Web Accessibility for People with Cognitive Disabilities: A Rapid Evidence Assessment. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alim, S. Web Accessibility of the Top Research-Intensive Universities in the UK. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211056614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, S.F. Improved Access and Participation for Persons with Disabilities in Local Governance. Policy Gov. Rev. 2020, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNASPA. Government to E-government to E-society. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/Home/E-Government-Survey-in-Media/ID/1408/Government-to-E-government-to-E-society (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- DOST-ICT. Government Website Template Design (GWTD) Guidelines. Available online: https://navy.mil.ph/images/DOST%20Government%20Website%20Template%20Design%20(GWTD)%20Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Paul, S. Accessibility analysis using WCAG 2.1: Evidence from Indian e-government websites. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2023, 22, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hujran, O.; Al-Debei, M.M.; Al-Adwan, A.S.; Alarabiat, A.; Altarawneh, N. Examining the antecedents and outcomes of smart government usage: An integrated model. Gov. Inf. Q. 2023, 40, 101783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Benyoucef, M. Usability and credibility of e-government websites. Gov. Inf. Q. 2014, 31, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoverde-Molina, M.; Luján-Mora, S.; Valverde, L. Accessibility of university websites worldwide: A systematic literature review. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2023, 22, 133–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, D.; Favalli, S. Web Accessibility for People with Disabilities in the European Union: Paving the Road to Social Inclusion. Societies 2018, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuaddous, H.Y.; Zalisham, M.; Basir, N. Web Accessibility Challenges. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2016, 7, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Singh, A. Factors Influencing Web Accessibility of Corporate Information: Indian Evidence. Int. J. -Bus. Res. 2020, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S, J.; Marthandan, G. Government to E-government to E-society. J. Appl. Sci. 2010, 10, 2205–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaphle, S. Citizen Charter as Governance Reform Initiative for Quality Services. J. Product. Discourse 2024, 2, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmal, A.J.; Alsaeed, M.; Hamid, S.; Zulait, A.H. Leveraging Social Media in Mobile Government: Enhancing Citizen Engagement and Service Delivery. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 8th International Conference on Engineering Technologies and Applied Sciences (ICETAS), Bahrain, Bahrain, 25–27 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Blythe, S.E. Hungary’s Electronic Signature Act: Enhancing Economic Development with Secure Electronic Commerce Transactions. Inf. Commun. Technol. Law 2007, 16, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indama, V. Digital Governance: Citizen Perceptions and Expectations of Online Public Services. Interdiscip. Stud. Soc. Law Politics 2022, 1, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikwuanusi, U.F.; Onunka, O.; Owoade, S.J.; Uzoka, A. Digital transformation in public sector services: Enhancing productivity and accountability through scalable software solutions. Int. J. Appl. Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 6, 2744–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, E. User-Centered Design to Enhance Accessibility and Usability in Digital Systems. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/386339454_User_centered_design_to_enhance_accessibility_and_usability_in_digital_systems (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Omweri, F. A Systematic Literature Review of E-Government Implementation in Developing Countries: Examining Urban-Rural Disparities, Institutional Capacity, and Socio-Cultural Factors in the Context of Local Governance and Progress towards SDG 16.6. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2024, 8, 1173–1199. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

_Bryant.png)