Abstract

The importance of business analytics (BA) in driving knowledge generation and business innovation has been widely discussed in both the academic and business communities. However, empirical research on the relationship between knowledge orientation and business analytics capabilities in driving business model innovation remains scarce. Drawing on the knowledge-based view and dynamic capabilities theory, this study develops a model to investigate the interplay between knowledge orientation and BA capabilities in driving business model innovation. It also explores the moderating role of industry type on this relationship. To test the model, data were collected from a cross-sectional sample of 207 firms (high-tech and non-high-tech industries). Descriptive and structural equation modeling (SEM) were used to test the hypotheses. The findings showed that knowledge orientation and BA capabilities are significantly and positively related to business model innovation. Knowledge commitment, shared vision, and open-mindedness are significantly and positively related to BA perception and recognition capabilities and BA integration capabilities. BA capabilities mediated the relationship between knowledge orientation and business model innovation. The path mechanism of knowledge orientation → BA capabilities → business model innovation shows that industry type has a moderating effect on knowledge orientation and BA capabilities, as well as BA capabilities and business model innovation. This study provides empirically proven insights and practical guidance on the dynamics and mechanisms of BA and organizational knowledge capabilities and their impact on business model innovation.

1. Introduction

The utilization of business analytics (BA) in extracting valuable insights from large amounts of unstructured data has become a key driver of business growth and innovation in today’s business landscape. A study by the MIT Center for Digital Business found that companies that use analytics to make decisions have a 5–6% higher productivity growth rate compared to those that do not use analytics [1]. Leading companies such as Amazon, Facebook, and Alibaba have implemented BA to gain a competitive advantage and drive growth [2,3]. For instance, Amazon uses BA to analyze customer data to improve its product recommendations, increase operational efficiency, and enhance the customer experience, resulting in a 30% increase in sales. Similarly, Facebook uses BA to analyze user data to improve its advertising targeting and increase revenue, resulting in a 40% increase in advertising revenue. Alibaba uses BA to analyze data from its e-commerce platforms to improve supply chain management, increase operational efficiency, and drive growth, resulting in a 20% increase in revenue. Traditional industries such as General Electric and Haier have also recognized the importance of BA in driving business model transformation and innovation, with GE’s use of data analytics resulting in a 15% increase in operational efficiency and Haier’s use of data analytics resulting in a 25% increase in customer satisfaction [2,4]. With the increasing availability of data and advancements in technology, the significance of BA in driving business growth and innovation will only continue to increase.

Previous studies have reported that the implementation of BA can lead to improved decision-making, enhanced operational efficiency, and increased revenue [5,6]. Additionally, research has also highlighted the importance of having a clear strategy and the right organizational structure in place to effectively utilize BA [7,8]. The proliferation of information technology and the emergence of vast amounts of data have led to ongoing advancements in organizational structures, with the benefits of business analysis (BA) becoming a crucial driver for companies as they strive to analyze and extract knowledge from the growing abundance of data. This is in line with the knowledge-based perspective of organizations, which posits that knowledge orientation is a dynamic process of discovering, utilizing, and generating knowledge within an organization, as well as valuing continual responsiveness to external changes [5]. Organizations that adopt a knowledge-oriented culture, characterized by a questioning attitude and disruptive innovation of existing ideas and models, are better positioned to benefit from BA. BA has the potential to facilitate business value reconstruction by challenging established cognitive frameworks, business models, and organizational behavior. As such, organizations must approach BA’s demands for change with an open-minded and inclusive attitude, dynamic intellectual thinking, and innovative organizational behavior [6,9]. Before employing BA capabilities to reconstruct business models, organizations must first master and acquire BA methodologies, and be able to use BA in their business processes [10,11]. However, before utilizing BA to reconstruct business models, organizations must first master and acquire the necessary methodologies and be able to effectively integrate BA into their business processes [12]. Thus, this study posits that in order to effectively master, adapt, and learn BA and its key values, organizations must develop a knowledge-oriented culture, establish a clear vision for organizational knowledge, and maintain an open mindset towards knowledge orientation. Additionally, organizations should internalize BA capabilities to understand, identify, analyze, integrate, and gain insight into the data they have accumulated. Finally, they should continually and incrementally facilitate business model innovation based on BA capabilities in order to stay competitive in an ever-changing business landscape.

The extant research on BA and its impact on business model innovation has illuminated the potential of BA in fostering organizational knowledge and innovation. However, there is a paucity of research that specifically examines the nexus between knowledge orientation and BA capabilities in driving business model innovation. Despite the disruptive nature of this technology, there remains a dearth of understanding of the practical implementation of BA in achieving actual business benefits through business model innovation [13]. Previous research has primarily delved into understanding the inherent mechanisms of business model innovation promoted by business analytics (BA) and the contextual factors that influence organizations to undertake such innovation [5,6]. However, these studies have presented unresolved queries pertaining to the capabilities and underlying factors of BA-based business model innovation, as well as the dynamics and processes through which BA capabilities drive business model innovation [14,15,16]. Consequently, a persistent and critical research question that must be addressed is: How can organizations cultivate and utilize BA capabilities to foster business model innovation in a dynamic environment characterized by the rapid evolution of information technology and the proliferation of fragmented data?

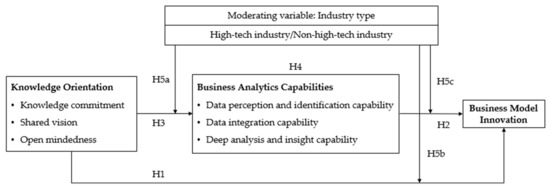

To address the aforementioned research questions, this study draws on the theoretical lens of knowledge view and dynamic capabilities of firms [7,17,18] to systematically investigate the intrinsic relationship and influence mechanism of knowledge orientation → BA capabilities → business model innovation. To this end, this study developed a theoretical model that delves into the association between knowledge orientation, business analytics capabilities, and business model innovation, while also exploring the moderating effect of industry type (i.e., high-tech and non-high-tech) on the aforementioned influencing mechanism and relationship. The proposed model was validated through the use of exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, utilizing a sample of 271 company questionnaires. Hypotheses were subsequently tested through the application of multi-group moderating analysis and structural equation modelling (SEM) [19].

The findings from the present study reveal that there exists a significant and positive correlation between knowledge orientation and business model innovation capabilities, with the former being a vital antecedent to the latter. Additionally, it was established that the constructs of knowledge commitment, shared vision, and open-mindedness are positively and significantly associated with Business Architecture (BA) perception and recognition capabilities, as well as BA integration capabilities. However, shared vision, open-mindedness, and deep analysis were found to be positively and significantly related to insight capability. Furthermore, the study posits that BA capability plays a mediating role in the relationship between knowledge orientation and business model innovation, thereby illuminating the causal path mechanism of knowledge orientation → BA capability → business model innovation. The research also uncovered that industry type exerts a moderating effect on the relationship between knowledge orientation and BA capability yet has no bearing on the relationship between knowledge orientation and business model innovation. The implications of these findings suggest that firms should adopt differentiated strategies for the development of their BA capabilities and initiatives, which should be contingent on the type of business model innovation they seek to achieve. Furthermore, these initiatives should take into consideration the knowledge motivation and knowledge culture of the organization.

The present study makes a threefold contribution to the existing literature on business analytics (BA) and business model innovation.

- Firstly, it enhances the existing theoretical understanding of the relationship between BA capabilities, knowledge orientation, and business model innovation by providing empirical evidence of the positive influence of BA capabilities and knowledge orientation on business model innovation, as well as the intrinsic relationship between knowledge orientation and BA capabilities.

- Secondly, it sheds light on the moderating effect of industry type, specifically highlighting the differential impact of high-tech and non-high-tech industries on the relationship between knowledge orientation and BA capabilities, and between BA capabilities and business model innovation.

- Lastly, it offers practical implications for companies to develop appropriate strategies to improve their BA capabilities by taking into account their knowledge dynamics and organizational culture.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a comprehensive overview of the theoretical foundations and the development of hypotheses that guide the research. Section 3 describes the research methodology adopted in the study, including the design and procedures used to collect and analyze data. Section 4 presents a detailed account of the study’s findings, including the results of statistical analyses and any other relevant information. Section 5 provides an in-depth examination of the study’s findings, highlighting their implications for both academic research and practical applications. Section 6 concludes the study by discussing the limitations, potential avenues for future research, and overall conclusions drawn from the current investigation.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Knowledge Orientation

Market dynamics are continually changing as a result of dynamic rivalry and innovation, and the relevance of knowledge is rising. To respond to the growth of the knowledge-based economy, businesses must form knowledge-based organizations and cultivate a knowledge-based culture. Knowledge orientation, as a crucial component of the corporate value system, encourages employees to learn new and creative knowledge through knowledge sharing and information interchange among employees, across organizational levels, and between enterprises. Nieves, et al. [17] classified knowledge orientation into three components: commitment to knowledge, shared vision, and open-mindedness. According to Zheng, et al. [18], knowledge orientation is a systematic organizational behavior that encompasses a dynamic cycle of information identification and acquisition, knowledge sharing and exchange, and knowledge development and application. In a study of complex consumer goods firms, Ashaari, et al. [20] found that collaborative, firm-led knowledge-oriented behavior can reduce unconscious time loss, increase a firm’s knowledge possibilities, and accelerate the pace of knowledge. Based on a multilevel theoretical framework, Ashrafi, et al. [21] investigated the impact of organizational knowledge and employee perceived knowledge on systematic problem solving and found that perceived knowledge mechanisms based on employee knowledge representation and knowledge coding, as well as organizational capture knowledge mechanisms, can assist employees in solving systematic problems at work.

Scholars have investigated the link between knowledge orientation and organizational innovation in traditional industrial organizations as well as high-tech information technology companies. The findings imply that knowledge orientation is crucial for transforming organizational behavior, boosting organizational competitiveness [5,6], and organizational innovation performance [8,22]. Chaudhuri, et al. [23] conducted an empirical study of the relationship between organizational knowledge orientation and team creativity. Chen, et al. [24] empirically investigated the mechanism of knowledge orientation on organizational innovation using empirical evidence from the Japanese hospitality industry and found that knowledge orientation in hospitality firms can have a significant positive impact on service innovation in organizational innovation via the mediating variable of organizational structure. According to the empirical findings of Ciampi, et al. [25], basic practices have an indirect impact on firm performance of manufacturing firms through exploratory and exploitative knowledge. In contrast, the core practices have an impact on firm performance through exploratory knowledge. Clauß, et al. [26] explored the link between knowledge orientation and order fulfillment performance in online and multichannel commerce from the perspective of organizational knowledge using machine search techniques. They found that knowledge orientation based on machine search and programming approaches promotes innovative performance and increases order fulfillment efficiency by 5%. According to De-Arteaga, et al. [27], knowledge orientation is critical in a climate where most small businesses are fast becoming outdated owing to dynamic technology iterations. Knowledge orientation influences growth dynamics through enhancing organizational innovation performance and customer satisfaction. By boosting organizational innovation performance and consumer happiness, it builds the groundwork for long-term success.

2.2. Business Analytics (BA) Capabilities

Early data analysis methods, such as regression and factor analysis, paved the way for BA. It requires mining data from high-speed data streams and sensor data for real-time analysis [3]. As such, it is an interdisciplinary discipline that draws on computer science, data science, statistics, and mathematical modeling. BA is a systematic process that involves collecting and analyzing business data, developing a statistical model to explain phenomena (descriptive analytics), developing a model to predict future outcomes based on variable inputs (predictive analytics), and developing a model to optimize or simulate outcomes based on changes in inputs (prescriptive analytics) [28].

To generate business insights and knowledge from enterprise data, BA uses statistical techniques such as regression, factor analysis, multivariate statistics, and machine learning. This activity requires careful planning and organization of the entire data analysis process, as it involves a wide range of internal and external data sources, enabling business executives to make informed decisions. In addition, strong data management capacity is required to build BA capabilities and successfully employ BA to transform a company’s perspective and restructure its business model [12,29]. Krishnamoorthi, et al. [30] define BA capability as an organization’s means of obtaining, cleanse, manage, and analyze vast volumes of data. O’Neill, et al. [31] devised the BA capability (BAC) paradigm by combining BA, information systems, and information technology. Kristoffersen, et al. [32] established the direct and indirect benefits of BA capability on enhancing company performance. Kumar, et al. [33] developed a visual BA cognitive capability model based on the structure of large competitive markets, allowing users to recognize asymmetric competitive elements and various submarkets in big visual markets. According to Lateef, et al. [34], among the BA competency categories, BA predictive capability may positively contribute to an organization’s sustainability goals and assist organizations in identifying prospects for business value and business model innovation.

Consistent with previous research, BA is a multifaceted and systematic capability that includes BA perception and identification, data integration, and deep analysis and understanding. In terms of the value creation process of BA applied to business model innovation, the volume, complexity, and pace of growth of BA in the digital economy age have far outpaced the conventional method of collecting data. BA has been incorporated into all elements of the company value chain, including upstream and downstream, as a new production component, driving the transformation and innovation of the original business model [25]. While BA is necessary to rebuild the components of a company’s business model, an enterprise must also be able to recognize, sense, integrate, analyze, exploit, and gain insight through BA in order to properly utilize BA for business model innovation. As a result, this study contends that in the age of the BA-driven digital economy, BA may be utilized to establish and reinvent business models. BA capability is one of the criteria for business model innovation in the data-driven digital economy. The development and cultivation of BA capability has an important impact on changes in the value orientation, value production, and value capture of business models, thus supporting the overall innovation of business models. However, existing research results lack systematic answers to the relationship between BA capabilities and business model innovation, and therefore, more in-depth research is needed.

2.3. Knowledge-Based View and Dynamic Capabilities

The concept of knowledge-based view (KBV) [18] of the firm posits that a firm’s competitiveness and performance is dependent on its ability to create, acquire, and utilize knowledge assets. This view emphasizes the importance of a firm’s intangible assets, such as its knowledge base and organizational capabilities, in creating and sustaining a competitive advantage. The dynamic capabilities theory builds on the KBV by emphasizing the importance of a firm’s ability to adapt and continuously renew its knowledge assets in response to changes in the business environment [17]. Business model innovation (BMI), in turn, is closely linked to both KBV and dynamic capabilities, as it requires a firm to continuously create, transfer, and integrate new knowledge in order to develop and implement new business models that can create value for customers and generate growth for the firm. Therefore, the relationship between KBV, dynamic capabilities, and business model innovation is one of mutual reinforcement, where a firm’s ability to innovate its business model is heavily dependent on its knowledge-based capabilities and dynamic capabilities.

Scholars have argued that a firm’s knowledge assets and capabilities, such as its understanding of customer needs and its ability to create new products and services, are crucial in developing new business models. Furthermore, the knowledge-based view theory highlights the importance of a firm’s ability to manage and leverage its knowledge assets through mechanisms such as knowledge creation, transfer, and integration to drive business model innovation. In order to effectively innovate its business model, a firm must be able to integrate knowledge across various competencies within the innovation environment and collaborate with external partners to exchange and combine different combinations of knowledge. This requires a holistic approach to managing knowledge and innovation ecosystems and a three-stage innovation value chain closely linked to knowledge-related capabilities [35]. By effectively leveraging its knowledge assets, a firm can continuously adapt and innovate its business model to stay competitive in an ever-changing market.

The literature has shown that there is a strong relationship between KBV and BMI. Scholars have argued that a firm’s knowledge assets and capabilities are critical enablers of BMI and that KBV can provide a useful framework for understanding how firms can create and exploit new business models. For example, a firm that has a strong knowledge base in a particular technology or industry may be better equipped to identify and capitalize on new business opportunities. Furthermore, a firm’s organizational capabilities, such as its ability to manage and leverage its knowledge assets, can play a crucial role in the successful implementation of new business models. Oesterreich, et al. [13] proposed an ecosystem approach for knowledge creation and diffusion, focusing on the interplay of socio-economic factors in shaping the co-evolution of knowledge and the economy. Hansen and Birkinshaw suggested that the innovation process can be broken down into three stages, each requiring different types of knowledge and partners. Turgut, et al. [36] argued that knowledge is difficult to measure directly and suggested that it is easier to identify and access different sources of knowledge. Many studies have shown that knowledge-based capabilities are closely related to long-term competitive advantage and business model innovation outcomes.

The knowledge-based dynamic capabilities (KBDC) framework combines the knowledge-based view of the firm, and the dynamic capabilities view to understand how organizations can create and sustain competitive advantage. KBDC is defined as the ability of a firm to acquire, generate and combine knowledge resources to sense, explore and address changes in the business environment [1]. However, despite the growing interest in this framework, there is limited research on KBDC, and conflicts on the true meaning and application of the term exist [30,32]. One of the gaps in this area of study relates to the application of KBDC in the context of business model innovation and analytics. While the knowledge-based view emphasizes the importance of knowledge assets in creating and sustaining competitive advantage, and the dynamic capabilities view focuses on the ability of the firm to adapt to changing environments, there is a lack of research on how these concepts can be applied to the process of business model innovation and how analytics can be used to support this process. This gap in research highlights the need for further exploration of the relationship between KBDC, business model innovation, and analytics.

3. Research Model and Hypotheses Development

3.1. Knowledge Orientation and Business Model Innovation

By developing a knowledge-based organizational culture, knowledge orientation helps companies to create knowledge, which is an important driver of growth for emerging companies [10]. This enables them to understand market changes and competitors’ actions, as well as new technological trends, in order to create superior new products and services [37]. The rapid development of information technologies such as artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and blockchain has created an overload of massive amounts of information. The digital economy has ushered in new concepts of business models and new tools for market operations. In response, organizations need to follow the trend and realize the value of acquiring, sharing, and creating knowledge on a knowledge-oriented basis so that they can collectively cope with change and invariance. The goal of corporate change and invariance is to break down intellectual and organizational barriers with an open and inclusive mind and creative thinking, to grasp the initiative behind changes in information and data, and to provide new ideas for long-term value generation. According to Clauß, et al. [26], new organizations operating in a high-tech context must build both an entrepreneurial and a strong knowledge orientation. Companies with a strong entrepreneurial orientation in a BA-supported high-tech context have a greater growth rate worldwide.

Business model innovation, as an act of strategic change at the firm level, reconfigures a company’s existing business model and market structure by overturning established norms and changing the nature of competition. It represents a change in the fundamental mindset and operating system of the company [8]. The source of innovation is business model innovation. The origin and starting point of business model innovation is new ideas. Knowledge absorption and generation of organizational knowledge based on knowledge orientation will become an important basis for business model innovation [38]. Business model innovation aided by knowledge orientation is an important component of business performance. Business model innovation supported by knowledge orientation creates the inventive capacity of the organization and contributes to its performance [10]. Gu, et al. [11] argued that knowledge orientation has a significant impact on business model innovation and can improve organizational innovation performance. Hsu, et al. [12] found that organizational knowledge orientation manifested as experimentation, risk-taking, exposure to external environment, communication, and participation has a good impact on product innovation effectiveness. Kaewnaknaew, et al. [39] conducted an empirical study on the mechanism of the role of open knowledge in business model innovation based on knowledge orientation and found that open knowledge outside the industry of high-tech enterprises has a greater contribution to business model innovation.

According to prior research findings, firms can only sustain innovation acuity in today’s era of expanding information technology and BA value by building an organizational knowledge mentality and culture that is open to sharing, fosters questioning, and exalts innovation [30,40]. Maintaining innovative acumen in a changing environment fosters business model innovation by constructing multiple business model features in terms of value orientation, value generation and delivery, and value capture [41]. As a result, based on Zheng, et al. [18] taxonomy of knowledge orientation dimensions, the following hypotheses are offered in this study:

H1:

Knowledge orientation has a significant positive effect on business model innovation.

H1a:

Knowledge commitment has a significant positive effect on business model innovation.

H1b:

Shared vision has a significant positive effect on business model innovation.

H1c:

Open-mindedness has a significant positive effect on business model innovation.

3.2. BA Capabilities and Business Model Innovation

As a multidimensional concept, BA capability includes three dimensions: data perception and identification capability, data integration capability, and deep analysis and insight capability [31,32,34]. From the perspective of dynamic capabilities, the dynamic evolution and enhancement of the three dimensions of BA capabilities also present a dynamic evolution mechanism for the transformation and innovation of business models.

First, in the era of BA-driven digital economy, enterprise business model innovation requires keen data perception and recognition capabilities. Enterprises can recognize the value of BA that affects business model innovation and establishes the organizational identity of BA business application through the perception of BA that penetrates into all dimensions of the business model. Enterprises can comprehensively understand the current development status and cutting-edge trends of BA technology in the context of rapid evolution of information technology and exponential and iterative development of technology. By identifying business-valuable data resources from the large amount of unstructured data, BA can be developed and utilized to extract useful information and knowledge. At the same time, companies can improve their ability to detect and identify BA as a resource and technology when using business models. The ability to recognize and identify BA when companies are dealing with business models can have a significant impact on the strategic awareness, business thinking, and organizational vision of decision makers at the thinking level. This will help entrepreneurs to improve their self-awareness and decision-making innovation, which will continuously drive the evolution and innovation of their business models According to Chester et al. [38], the goal of business model innovation is to produce new business value in an uncertain market environment. The ability to recognize the complex and changing environment and technological agility is an important and necessary prerequisite for business model innovation.

Second, the integrity and level of business model innovation is determined by BA’s integration capabilities. According to Oesterreich, et al. [13], digital transformation in a BA-supported digital economy requires companies to rethink and develop their business models. In addition, increased resource allocation and data integration will have a substantial impact on the design and implementation of business model aspects. This process determines whether business model innovation will succeed or fail. This also makes it necessary for companies, especially SMEs, to achieve business model innovation by developing and using data integration techniques. BA is a significant strategic resource in the practice of organizations, covering soft and hard aspects such as BA mining tools, BA analysis technology, BA business application, and BA talent building. BA integration and coordination based on the aforementioned factors will have a positive influence on business model planning, reconstruction, and execution. Companies may, for example, iterate and generate digital goods and services based on BA by integrating BA resources from upstream and downstream of production, logistics, marketing, and supply chain, and connecting them with consumer demands. In addition to modifying the original product structure, transactions and payment methods, new profit models and revenue structures are developed, reconfiguring the corporate value capture mechanism and forming corporate business model innovations [14].

Third, BA’s deep analysis and insight capabilities are critical to applying BA to business models and shaping business value. It is also an important driver throughout the identification, analysis, reconfiguration, and value invention of business models. According to Rana, et al. [15], BA changes not only the breadth but also the depth of information value, introducing new perspectives and new ways for organizations to produce new value and serve new needs. In the framework of Industry 4.0 innovation, Rao, et al. [16] analyzed business models. They found that the breadth of BA analysis and insight can enable digital transformation of business models by reconfiguring business models, optimizing internal and external processes, improving customer relationships, and developing new value or smart products and services through disruptive business models. Daradkeh [42] believed that in-depth insight and analysis of BA can help companies seize business hotspots and make important decisions in a timely manner. According to Daradkeh [43], the development of blockchain technology has injected new IT drivers for business model innovation. On the one hand, enterprises can realize the innovation of convergence between novelty, efficiency and complementarity in value creation based on blockchain technology. On the other hand, blockchain technology can help enterprises switch between locking, bundling, and imitating barriers to value acquisition, thus achieving innovation and upgrading of business models. Therefore, based on the above theoretical deduction of the relationship between BA capability and business model innovation, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H2:

BA capabilities have a significant positive effect on business model innovation.

H2a:

Data perception and identification capability has a significant positive effect on business model innovation.

H2b:

Data integration capability has a significant positive effect on business model innovation.

H2c:

Deep analysis and insight capability has a significant positive effect on business model innovation.

3.3. Knowledge Orientation and BA Capabilities

Recent studies have demonstrated that organizations with a strong knowledge orientation tend to possess higher BA capabilities [14,16,31]. This is because a knowledge-oriented organization places a high value on the acquisition and utilization of information and expertise, which enables the effective use of data and analytics in decision-making. Furthermore, a knowledge-oriented organization is more likely to have systems and processes in place to support the collection and analysis of data, which is essential for the development of BA capabilities. However, the relationship between knowledge orientation and BA capabilities is not solely one-directional. BA capabilities can also enhance an organization’s knowledge orientation by providing access to more accurate and relevant information, which can inform decision-making and problem-solving [40]. The integration of BA capabilities into an organization’s knowledge management processes can also improve the efficiency and effectiveness of knowledge acquisition and utilization. However, since the optimal balance between knowledge orientation and BA capabilities will vary depending on the specific goals and needs of the organization, organizations should carefully consider their unique circumstances when developing and implementing knowledge management and BA strategies [44].

Business analytics can be seen as a dynamic capability that can assist companies to successfully address digital opportunities and challenges. Therefore, companies must have dynamic capabilities to adjust in dynamic competitive markets where change is the only constant. BA capabilities are seen as a dynamic capability that can assist companies to successfully address digital opportunities and challenges [7,23]. Moreover, during the formation and development of BA capabilities, companies should change their mindset and form organizational knowledge mechanisms to meet the challenges of new technology development and BA applications. Therefore, enterprises should strengthen the important value of knowledge commitment to adapt to the dynamic environment and establish a development vision of shared digital economy-driven business model innovation. Through the construction of an open mindset, an organizational environment and behavior pattern of active knowledge seeking, shared knowledge seeking, and knowledge creation will be formed to continuously expand the boundaries of organizational capabilities.

During the formation and development of BA capabilities, companies should change their mindset and form organizational knowledge mechanisms to meet the challenges of new technology development and BA applications [45]. Through the construction of an open mindset, an organizational environment and behavior pattern of active knowledge seeking, shared knowledge seeking, and knowledge creation will be formed to continuously expand the boundaries of organizational capabilities [46]. Additionally, a knowledge-oriented organization is more likely to have systems and processes in place to support the collection and analysis of data, a crucial aspect of developing BA capabilities [33,41]. Therefore, enterprises should strengthen the important value of knowledge commitment to adapt to the dynamic environment and establish a development vision of shared digital economy-driven business model innovation. However, there is a gap in literature regarding the specific mechanisms through which a knowledge orientation leads to enhanced BA capabilities. Further research is required to understand the underlying process and the optimal balance of knowledge orientation and BA capabilities for achieving organizational performance.

To meet the challenges of dynamic technological changes and markets, organizations must continuously develop their BA capabilities such as perception, identification, integration, analysis, and insight to face dynamic technological advances and market demands. Therefore, knowledge orientation, including three aspects of knowledge commitment, shared vision, and mindset, is essential to improve BA capabilities and organizational performance. Using data from 317 companies, Shi, et al. [47] experimentally investigated the relationship between knowledge orientation and dynamic capabilities. Soluk, et al. [48] investigated the mechanisms of exploratory and exploitative knowledge on dynamic capabilities. They found that firms need to combine exploratory and exploitative knowledge to discover the value of new technology applications through exploitative knowledge and to enhance dynamic capabilities through exploratory knowledge. The results of Olabode, et al. [14] study the relationship between knowledge orientation, and BA dynamic capabilities in digital education showed that knowledge orientation based on organizational and employee personalization offers the possibility of improving BA capabilities, socio-educational digital innovation, and equity. Firms engaged in educational services can continuously improve BA capabilities to meet teaching and knowledge requirements and educational equity by continuously customizing knowledge and applying knowledge analysis, BA resources, and stakeholder feedback. Based on the above theoretical derivation of the interplay between knowledge orientation and BA capabilities, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H3:

Knowledge orientation has a significant positive effect on BA capabilities.

H3a:

Knowledge commitment has a significant positive effect on data awareness and recognition ability.

H3b:

Knowledge commitment has a significant positive effect on data integration capability.

H3c:

Knowledge commitment has a significant positive effect on deep analysis and insight capability.

H3d:

Shared vision has a significant positive effect on data perception and recognition.

H3e:

Shared vision has a significant positive effect on data integration capability.

H3f:

Shared vision has a significant positive effect on deep analysis and insight.

H3g:

Open-mindedness has a significant positive effect on data perception and recognition.

H3h:

Open-mindedness has a significant positive effect on data integration ability.

H3i:

Open-mindedness has a significant positive effect on deep analysis and insight.

3.4. Mediating Role of BA Capabilities

The ability to leverage BA capabilities is critical to transforming companies and facilitating business model innovation. However, recognizing the importance of Bas and improving their capabilities requires building a knowledge organization and maintaining a dynamic knowledge environment [14,32]. First, BA disrupts existing business paradigms by developing new ways of thinking and creating company value. Companies must be aware of the business benefits of the BA and create BA capabilities by focusing on internal organizational knowledge. Second, in the BA-driven digital economy, according to resource theory and dynamic capability theory, organizations must not only acquire BA, but also perceive and identify valid and economically relevant data from unstructured, heterogeneous, and huge data. This requires organizations to have excellent BA capabilities. Otherwise, the benefits of BA will not be realized, but will become a burden and responsibility for the organization. In the above influential relationship between knowledge orientation, BA capabilities, and business model innovation, companies improve BA capabilities through knowledge commitment, shared vision, and open knowledge orientation. Firms discover new business value through BA integration capabilities and reposition consumers to understand their demand preferences and create new products and services for them. Based on the in-depth analysis and insight of BA, new profit models and forward-looking strategic business layout are explored and established so as to better serve the business model innovation and strategic practice of enterprises and gradually form competitive advantages with enterprise characteristics. Therefore, it can be speculated that in the transmission mechanism of knowledge orientation → BA capability → business model innovation, the knowledge mechanism constructed by knowledge orientation ensures the adaptability and continuous improvement of BA capability of enterprises. In turn, the enhancement of BA capability further promotes the innovation and transformation of enterprise business models. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed in this study:

H4:

BA capabilities mediate the relationship between knowledge orientation and business model innovation.

3.5. Moderating Effect of Industry Type

In the context of digital economy, the innovation of business models based on BA is considered to be an inevitable choice for high-tech industrial enterprises such as new energy companies, Internet companies, and e-commerce companies, and has also been studied by scholars [36,44]. However, as new technologies such as BA, cloud computing, and 5G continue to penetrate and influence the development of digital transformation of traditional enterprises, traditional enterprises also need to advance their business models based on the requirements of BA and the challenges of digital transformation [2,8,11]. In the process of digital transformation of traditional enterprises, traditional enterprises also need to promote business model innovation based on the requirements of BA and the challenges of digital transformation [33,38,49]. What kind of differences exist in the transmission mechanism of knowledge orientation → BA capabilities → business model innovation among different industrial attributes and different types of enterprises? So far, no research has been able to provide a systematic answer.

This study draws on the research paradigm of relevant scholars [9,34,50] to further examine the moderating effect of industry type (high-tech industry and non-high-tech industry) on the relationship between knowledge orientation → BA capabilities → business model innovation. Specifically, this study examines the moderating effect of industry type on knowledge orientation and BA capabilities, the moderating effect of industry type on knowledge orientation and business model innovation, and the moderating effect of industry type on BA capabilities and business model innovation, so as to better answer the generality and specificity of BA-driven business model innovation in enterprises of different industry types. According to Nieves, et al. [17], enterprises in high-tech industries mainly include electronic information, biology and new medicine, aerospace, new materials, high-tech services, new energy and energy conservation, resources and environment, advanced manufacturing, and automation. In contrast, firms in non-high-tech industries mainly refer to general manufacturing and service firms [40]. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5:

Industry type moderates the relationship between knowledge orientation, BA capabilities, and business model innovation.

H5a:

Industry type has a moderating effect on the relationship between knowledge orientation and BA capabilities.

H5b:

Industry type has a moderating effect on the relationship between knowledge orientation and business model innovation.

H5c:

Industry type has a moderating effect on the relationship between BA capabilities and business model innovation.

Based on the above analysis and theoretical discussion, the theoretical model of this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Data Collection

This study primarily used questionnaires to collect data. The questionnaires were distributed purposively to ensure that the firms asked had the expertise and capability to use BA for business model innovation. The analysis conducted in this study was based on senior business analytics professionals (see Table 1). These professionals are drawn from Fortune 500 companies in the United Arab Emirates, many of which are headquarters of leading global multinational technology and service companies in the MENA region, and also include government departments and semi-state agencies with advanced analytical capabilities. The sample of firms (high-tech and non-high-tech industries) was obtained from the Dubai Chamber of Commerce and Industry (https://www.dubaichamber.com/en/home/ (accessed on 21 January 2023)) in the United Arab Emirates. It should be emphasized that a potential limitation of any survey is the target population, which has the potential to introduce bias into the findings, as well as to influence the true population beyond the sample population in judging the generalizability of the findings. In this study, we deliberately targeted senior individuals who have an organizational perspective on any possible impact of investments and activities in and around business analytics, as the key research question was to test the correlation between the generated knowledge orientation and BA capabilities present in the organization and their impact on business model innovation.

Table 1.

Distribution of sample characteristics (n = 207).

The questionnaires were distributed and collected in three ways: first, through the online platform of Questionnaire Star; second, by distributing and collecting the questionnaires from MBA students on site; third, through the MBA alumni group; the electronic version of the questionnaires was sent to the respondents. The data were collected between June and October 2022. A total of 700 questionnaires were distributed in this study, and 286 questionnaires were returned, with a sample return rate of 41.5%. Through screening, 79 invalid questionnaires that were incomplete or had obvious similarities were excluded, and 207 valid questionnaires were obtained. Among them, 147 belonged to enterprises in high-tech industries and 130 belonged to enterprises in non-high-tech industries. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted on the data from the three sources, and it was found that there were no significant differences in the data collection methods and sampling firms, thus they could be combined for analysis.

4.2. Variable Measurements

To ensure content validity of the survey, the variables were measured mainly based on established scales that have been published and applied in previous studies. The knowledge orientation variables included three dimensions: knowledge commitment, shared vision, and openness. These scales were largely adapted from Chaithanapat, et al. [8] and included 18 items, of which six measured knowledge commitment, six measured shared vision, and six measured openness. BA capabilities were measured in three dimensions: data perception and recognition, data integration, and deep analysis and insight. These items were mainly derived from the studies of Kristoffersen, et al. [41], Kristoffersen, et al. [32], and Munir, et al. [51]. Among them, data perception and identification included five items, data integration included five items, and deep analysis and insight included seven items. The measures of business model innovation were mainly adapted from the study by Nieves, et al. [17], which measured business model innovation in terms of value repositioning, value transfer and acquisition network reconfiguration, and value proposition innovation. As shown in Table 2, each item in the questionnaire was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 is strongly agree and 5 is strongly disagree.

Table 2.

Results of reliability and convergent validity tests.

5. Results Analysis

5.1. Reliability and Validity Test

To evaluate variables and their associated measures, we conducted reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity tests. In this study, Cronbach’s coefficient and Composite Reliability (CR) were used to test the reliability of each variable (at the construct level). As shown in Table 2, the results show that the Cronbach’s α coefficients for each variable and its dimensions are greater than 0.70, which is higher than the acceptable threshold of 0.60 [52]. The CR of each variable was also above the critical value of 0.70, and therefore, the measures were sufficiently reliable. The reliability of the indicator was assessed by checking whether the variable and item loadings were above a threshold of 0.70. To determine the convergence validity, we checked whether the average variance extracted value (AVE) was above the lower limit of 0.50. The minimum value observed was 0.62, which is considerably above this threshold. In terms of discriminant validity, confirmatory factor analysis was used to test if each indicator’s outer loading was greater than its cross-loadings with other constructs [53]. As presented in Table 2, the normalized factor loadings (λ) for knowledge commitment, shared vision, open mindedness, data perception and identification capability, data integration capability, deep analysis and insight capability, and business model innovation were all above 0.60; all reached the threshold of normalized factor loadings above 0.50. The average variance extracted (AVE) of each variable is also above 0.60, and its square root is greater than 0.70, which is greater than the correlation coefficient of this factor with other factors. Thus, these variables exhibit sufficient discriminant validity.

5.2. Structural Equation Modeling

In this study, the overall theoretical model of the relationship between knowledge orientation, BA capabilities, and business model innovation was fitted with AMOS 22.0 software based on the goodness-of-fit indices tested by structural equation modeling. The results of fitting indices shown in Table 3 indicate that the standard chi-square value (χ2/df) (1.932), comparative fit index CFI (0.921), fit index GFI (0.932), and performance index IFI (0.914) and NNFI (0.907) indices of the model satisfy the requirements of structural equation model testing. Therefore, the overall theoretical model of the relationship between knowledge orientation, BA capabilities, and business model innovation provides a good estimation model to fit the data, and the theoretical model of this study is acceptable.

Table 3.

Results of model fitting indicators.

5.3. Path Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

5.3.1. Relationship between Knowledge Orientation, BA Capabilities, and Business Model Innovation

The theoretical model of this study contains a total of seven research variables. However, because knowledge orientation and BA capabilities are multidimensional variables, hypothesis testing of these variables focused primarily on the examination of their sub-variables. The three components of knowledge orientation constitute three exogenous variables. The three components of BA capabilities constitute three mediating variables that act as both influences and causes of the other exogenous variables. Business model innovation, as an endogenous variable, is a unidimensional variable. Based on the relationship between the variables, 15 paths and corresponding hypotheses in the research model were obtained. The results of the path coefficients and hypothesis tests are shown in Table 4. The path coefficients of all hypotheses, except H3f and H3i, exhibit significant relationships with each other. Thus, H1 and H2 are supported, but H3 is only partially supported.

Table 4.

Results of path coefficients and hypothesis testing.

5.3.2. Mediating Effect of BA Capabilities

This study examines the mediating effect of BA capabilities on the relationship between knowledge orientation and business model innovation by comparing the direct and indirect effects of the variables to verify the mediating effect test rule. The direct effects include the direct effect of the independent variable on the outcome variable and the direct effect of the mediating variable on the outcome variable. The rule for calculating the indirect effect is: indirect effect = direct effect of the independent variable on the mediating variable × direct effect of the mediating variable on the outcome variable [54]. According to the above rules for testing the mediating effect, if both the direct effect of knowledge orientation on business model innovation and the direct effect of BA capabilities on business model innovation are smaller than the effect of knowledge orientation on business model innovation through BA capabilities (i.e., the indirect effect of knowledge orientation on business model innovation), then the mediating effect of BA capabilities on the relationship between knowledge orientation and business model innovation is smaller than the direct effect of knowledge orientation on business model innovation (i.e., the indirect effect of knowledge orientation on business model innovation). The results of the mediating effect test of BA capabilities on the relationship between knowledge orientation and business model innovation are shown in Table 5. The direct effect of knowledge orientation on business model innovation (impact coefficient of 0.758) and the direct effect of BA capabilities on business model innovation (impact coefficient of 0.653) are smaller than the indirect effect of knowledge orientation on business model innovation (1.366 × 0.653 = 0.892). Therefore, the mediating effect of BA capabilities holds and H4 is supported.

Table 5.

Test results of mediating effects of BA capabilities.

5.3.3. Moderating Effect of Industry Type

In this study, a multiple sampling analysis technique was used to investigate the moderating effect of different industry types on the relationship between knowledge orientation, BA capabilities, and business model innovation [19]. Table 6 displays the results of the moderation test of industry type on the relationship between knowledge orientation, BA capabilities, and business model innovation.

Table 6.

Test results of the moderating effect of industry type on the relationship between knowledge orientation, BA capabilities, and business model innovation.

First, the χ2 value in the unconstrained model is 135.87, the correlation coefficient between knowledge orientation and BA capabilities in the subsample of high-tech and non-high-tech firms is set as a relative value, and the other parameter values are estimated freely. Comparing the constrained and unconstrained models, the difference in χ2 values is 3.77, which is significant at the p < 0.05 level, indicating that industry type has a moderating effect on the relationship between knowledge orientation and BA capabilities. This suggests that H5a is supported.

Second, similarly, the χ2 value of the moderating effect of industry type on the relationship between knowledge orientation and business model differs by 1.15 between the constrained and unconstrained models and does not reach a significant level. This indicates that industry type has no moderating effect on the relationship between knowledge orientation and business model innovation; thus, hypothesis H5b is not supported. Third, comparing the constrained and unconstrained models, the χ2 value of the moderating effect of industry type on the relationship between BA capabilities and business model innovation differs by 4.17 and is significant at the p < 0.05 level. This indicates that industry type has a moderating effect on the relationship between BA capabilities and business model innovation. Therefore, hypothesis H5c is supported. The above test results indicate that industry type moderates knowledge orientation and BA capabilities, BA capabilities, and business model innovation, but shows no moderating effect on knowledge orientation and business model innovation. Therefore, hypothesis 5 is only partially supported.

The results of comparing the coefficients of variable paths between high-tech and non-high-tech firms are presented in Table 7. In the case of non-high-tech firms, the coefficients of knowledge orientation and BA capabilities (0.754) and BA capabilities and business model innovation (0.674) are significantly larger than the coefficients of knowledge orientation and BA capabilities (0.417) and BA capabilities and business model innovation (0.347). However, in the case of high-tech companies, the coefficients of knowledge orientation and business model innovation (0.742) and knowledge orientation and business model innovation are significantly greater than the coefficient of knowledge orientation and business model innovation (0.711). This indicates that the influence of knowledge orientation on BA capabilities and the influence of BA capabilities on business model innovation of high-tech industry enterprises is greater than that of non-high-tech industry enterprises. Therefore, under the moderating effect of industry type, the degree of influence of knowledge orientation on BA capabilities and the degree of influence of BA capabilities on business model innovation of high-tech industry enterprises is greater than the influence of knowledge orientation on BA capabilities and the influence of BA capabilities on business model innovation of non-high-tech industry enterprises.

Table 7.

Comparative analysis of the path coefficients of the relationship between knowledge orientation, BA capabilities, and business model innovation in enterprises of different industry types.

6. Discussion

Based on the knowledge-based view and dynamic capabilities of the firm, this study examines the interactions among BA capabilities, knowledge orientation, and business model innovation, and empirically tests the moderating effect of industry type on these interactions. The main findings of this study are as follows.

First, both knowledge orientation and BA capabilities have a significant positive relationship with business model innovation. The positive impact of knowledge orientation on business model innovation is supported by the significant positive relationship between the three sub-dimensions of knowledge orientation: knowledge commitment, shared vision and open-mindedness, and business model innovation. All three sub-dimensions of BA capabilities (data perception and identification, data integration, and deep analysis and insight) have a significant positive relationship with business model innovation. These findings are strategically important and suggest that BA, as an important resource and asset, does not by itself lead to the development of business model innovation. On the contrary, BA capabilities must be utilized to improve each component of the business model or the overall system to promote the transformation and innovation of the business model. Therefore, enterprises should not only pay attention to the precipitation and accumulation of BA resources, but should also strengthen the cultivation of BA capabilities, which is an important factor affecting whether the potential value of BA can be tapped and utilized. This is also one of the inevitable ways to promote the innovation of enterprise business model.

Second, the relationship between knowledge orientation and BA capabilities was partially supported. The three sub-dimensions of knowledge commitment, shared vision, and open-mindedness had significant positive correlations with two sub-dimensions of BA capabilities (data perception and identification capabilities and data integration capabilities). In addition, the knowledge orientation sub-dimension of knowledge commitment had a significant positive relationship with the deep analysis and insight sub-dimension of BA capabilities. However, shared vision and open-mindedness did not have a significant positive effect on deep analysis and insight capability. This may be due to the fact that BA competency, as a dynamic capability [12,29,50], requires a systematic process of knowledge and cultivation, based on the awareness, reflection, exploration, and insight of potential, emerging, and applied information technology and external business transformations to BA technologies. Among them, data perception and identification capabilities are the prerequisite capabilities for data integration capabilities. Data integration capability is a prerequisite for deep analysis and insight capability. As a result, it forms an evolutionary process from data perception and recognition capability to data integration capability to deep analysis and insight capability. The accumulation process of quantitative change causes qualitative change. The improvement of enterprise BA deep analysis and insight capability stimulates the accumulation of enterprise data perception capability and data integration capability, which interacts and evolves in a cycle at a new level. In addition, in the context of the big data era where the digital economy drives business model transformation and innovation, the combination of deep analysis and insight capabilities and business model innovation is also influenced by many dynamic factors, such as the organizational vision of the company, the mental model of managers, the size of the company, and the expansion of business boundaries [9]. Deep analysis and insight capabilities are among the most important capabilities for companies to drive BA-based business model innovation [55]. Shared vision and open-mindedness, as important components of organizational culture, have been internalized as fundamental organizational requirements that drive growth and development throughout the company. Therefore, they have no direct impact on BA’s deep analysis and insight capabilities [56].

Third, BA capabilities play a mediating role in the relationship between knowledge orientation and business model innovation, showing a path mechanism of knowledge orientation → BA capabilities → business model innovation. This finding indicates that, on the one hand, knowledge orientation and organizational knowledge behavior based on knowledge orientation are important driving forces for BA competency cultivation, development, and growth. Although BA brings new ways of thinking, development concepts, organizational resources, production factors, and business opportunities, companies will not be able to recognize the value of BA if they do not establish a knowledge-oriented organizational culture. In addition, they will not be able to explore and integrate the business value of BA through analytical knowledge and insight to form new business opportunities. Therefore, a high degree of knowledge orientation within the enterprise will promote BA capabilities, thus facilitating the smooth development of BA from perception and identification to integration and application.

On the other hand, the improvement of BA capability is a necessary condition for the success of BA-based business model innovation. Business model innovation includes three aspects: value proposition, value creation, and value delivery. The improvement of BA capability will help enterprises to perceive, identify, integrate, analyze, and insight BA. Through the combination of BA and consumer demand, new value positioning and value proposition are formed, new consumer value is created for customers, and the value delivery mechanism of digitalization, industry chain integration, and profit innovation is realized. Thus, the business model innovation embedded through BA promotes the value-added and dynamic sustainable development of the enterprise. According to Munir, et al. [51], the cultivation status of BA capabilities is the key to whether a firm can capture and exploit the business value of BA. It is also an important part of the business model innovation process of an enterprise. Having BA is not valuable to the organization; only by structuring the knowledge, properly examining the business prospects hidden in these data, translating it into business models, and encouraging business model innovation can BA generate meaningful value for the enterprise.

Finally, industry type has a moderating effect on knowledge orientation and BA capabilities as well as BA capabilities and business model innovation. However, it does not moderate the relationship between knowledge orientation and business model innovation. First, the effect of knowledge orientation on BA capabilities of high-tech industry firms is greater than the effect of knowledge orientation on BA capabilities of non-high-tech industry firms. Second, the degree of influence of BA capabilities of high-tech industry enterprises on business model innovation is greater than the influence of BA capabilities of non-high-tech industry enterprises on business model innovation. Third, the degree of knowledge orientation’s influence on business model innovation is higher in both high-tech and non-high-tech enterprises. Therefore, although there is a significant effect of knowledge orientation on BA capabilities and BA capabilities on business model innovation in different industrial environments, the effect of knowledge orientation on BA capabilities and BA capabilities on business model innovation is stronger in high-tech enterprises. In the process of improving dynamic capabilities and promoting knowledge-based business model innovation, the effect of knowledge orientation on BA capabilities and BA capabilities on business model innovation is stronger.

7. Managerial Implications

The findings from this study provide several implications for companies in the digital economy to establish a knowledge-oriented organizational culture, enhance BA competencies, and promote business model transformation and innovation based on BA capabilities.

First, the findings from this study suggest that firms should elevate the building of knowledge-based organizations to the strategic level of the company. They also need to develop a vision-sharing system within the organization through communication and dissemination, and cultivate employees’ mindset of being open, inclusive, and proactive in adapting and embracing change. To create an organizational climate and knowledge environment of trust, sharing, and openness, organizations should establish horizontal and vertical mechanisms for sharing knowledge, technology, and information among employees, teams, and departments so that employees are willing to innovate and enjoy innovation.

Second, this study emphasizes the importance of BA capacity building and vigorously improving enterprises’ cognitive identification, data integration, and deep analysis and insight capabilities of BA. Enterprises should widely promote new technologies and concepts such as BA, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and blockchain, and their business application values to their employees. Enterprises should pay attention to the cognition and adoption of BA technology and strengthen the integration of BA technology with existing technology systems. At the same time, we should pay attention to the construction of BA talents and digital economy talents and establish a professional talent training system for enterprises through internal training and external introduction in order to cope with the dynamic evolution of BA technology.

Third, this study concludes that enterprises should adequately utilize the power of BA capabilities in the conduction of organizational knowledge orientation and business model innovation. In the process of promoting business model innovation, enterprises should improve BA’s perception and identification ability, data integration ability, and deep analysis and insight ability through knowledge orientation. On the basis of improving BA’s ability, it promotes local and overall innovation of business model. This is also an inevitable way for enterprises to enhance business model innovation and achieve sustainable development through BA capability in dynamic and uncertain markets.

Finally, the findings from this research show that both high-tech and non-high-tech enterprises need to pay a great deal of attention to the role of knowledge orientation in the process of business model innovation, enhance BA capability through knowledge orientation, and promote business model transformation and innovation. In contrast, traditional industrial enterprises should actively promote industrial upgrading and enterprise transformation to realize the transformation from traditional technology and traditional manufacturing to digitalization, smart manufacturing, and other high-tech enterprises so as to better cope with the challenges of BA, improve BA capability, and finally realize business model innovation in the digital economy era.

8. Conclusions

Drawing on knowledge orientation and dynamic capability theory, this study examines the direct relationship between knowledge orientation, BA capability, and business model innovation. In addition, this study examines the mediating role of BA capabilities in knowledge orientation and business model innovation, as well as the moderating role of industry type. The results show that knowledge orientation and BA capabilities are significantly and positively related to business model innovation, while knowledge commitment, shared vision, and open-mindedness are significantly and positively related to BA perception and recognition capabilities and BA integration capabilities. However, shared vision, open-mindedness, and deep analysis were significantly and positively related to insight capability. BA capability has a mediating role in the relationship between knowledge orientation and business model innovation, showing the path mechanism of knowledge orientation → BA capability → business model innovation. Industry type has a moderating effect on knowledge orientation and BA capability but has no effect on the relationship between knowledge orientation and business model innovation. The results of this study suggest that firms should develop different strategies to develop their BA capabilities and initiatives. Doing so depends heavily on the type of business model innovation they aim to achieve. In addition, these initiatives should consider the knowledge motivation and knowledge culture of the firm.

9. Research Limitations and Future Directions

While the findings from this study provide important insights into the relationship between knowledge orientation and BA capabilities in driving business model innovation, this study inevitably has some limitations. First, this study only considers business model innovation as a unidimensional concept. However, many scholars have mentioned that business model innovation is a systematic and holistic innovation at the firm level, which involves the interaction of various factors within the business model [21]. Second, in this study, BA capabilities must traverse an evolutionary process from data perception and recognition to data integration to deep analysis and insight. The process of quantitative change leading to qualitative change is one in which the three sub-dimensions impact and interact with one another, rather than being unconnected and parallel. Third, this study does not investigate the link between the dimensions of BA capability, which might be enhanced in the future to supplement the theoretical model presented in this work. Finally, most of the empirical data in this study were collected through survey instruments. This may lead to an overestimation of the applicability of BA and business model innovation in organizations.

As the business landscape continues to evolve, the concept of business model innovation will become increasingly multidimensional in nature. In the future, it will be necessary to study business model innovation from multiple perspectives in order to fully grasp the impact of knowledge orientation and business architecture (BA) capability on each dimension of innovation and the interactions among them.

One way to enhance the external validity of these findings is by incorporating objective data published by business model innovation index reports from global research institutions or publicly traded firms. This approach would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the nuances of business model innovation and the factors that contribute to its success. Additionally, by leveraging data from a wide range of sources, researchers can gain a more nuanced understanding of how different dimensions of business model innovation interact with one another, and how these interactions can be leveraged to drive growth and success in the future.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Mikalef, P.; Krogstie, J.; Pappas, I.; Pavlou, P. Exploring the relationship between big data analytics capability and competitive performance: The mediating roles of dynamic and operational capabilities. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Ahmad, I.; Rana, N.; Khan, I. An Empirical Investigation on Business Analytics in Software and Systems Development Projects. Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 24, 1145–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daradkeh, M. Innovation in Business Intelligence Systems: The Relationship between Innovation Crowdsourcing Mechanisms and Innovation Performance. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Serv. Sect. (IJISSS) 2022, 14, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Baghdadi, E.; Alrub, A.; Rjoub, H. Sustainable Business Model and Corporate Performance: The Mediating Role of Sustainable Orientation and Management Accounting Control in the United Arab Emirates. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M.; Ahmed, M.; Haider, S.; Sajjad, M. Expanding competitive advantage through organizational culture, knowledge sharing and organizational innovation. Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, M.; Shokouhyar, S. The role of big data analytics capabilities in bolstering supply chain resilience and firm performance: A dynamic capability view. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 35, 1621–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda, G.; Vera, D. Dynamic capabilities and operational capabilities: A knowledge management perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaithanapat, P.; Punnakitikashem, P.; Oo, N.C.K.K.; Rakthin, S. Relationships among knowledge-oriented leadership, customer knowledge management, innovation quality and firm performance in SMEs. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, H.; Shahzad, M. Business analytics competencies in stabilizing firms’ agility and digital innovation amid COVID-19. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreras-Méndez, J.; Olmos-Peñuela, J.; Salas-Vallina, A.; Alegre, J. Entrepreneurial orientation and new product development performance in SMEs: The mediating role of business model innovation. Technovation 2021, 108, 102325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, V.; Zhou, B.; Cao, Q.; Adams, J. Exploring the relationship between supplier development, big data analytics capability, and firm performance. Ann. Oper. Res. 2021, 302, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.; Hsin, Y.; Shiue, F. Business analytics for corporate risk management and performance improvement. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 315, 629–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterreich, T.; Anton, E.; Teuteberg, F. What translates big data into business value? A meta-analysis of the impacts of business analytics on firm performance. Inf. Manag. 2022, 59, 103685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabode, O.; Boso, N.; Hultman, M.; Leonidou, C. Big data analytics capability and market performance: The roles of disruptive business models and competitive intensity. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, N.; Chatterjee, S.; Dwivedi, Y.; Akter, S. Understanding dark side of artificial intelligence (AI) integrated business analytics: Assessing firm’s operational inefficiency and competitiveness. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2022, 31, 364–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, D.; Provodnikova, A. Analysing the role of business analytics adoption on effective entrepreneurship. In Proceedings of the 2021: International Conference on Business and Integral Security (IBIS) 2021, online, 25 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nieves, J.; Haller, S. Building dynamic capabilities through knowledge resources. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Zhang, W.; Du, J. Knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and innovation in networked environments. J. Knowl. Manag. 2011, 15, 1035–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Risher, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaari, M.; Singh, K.; Abbasi, G.; Amran, A.; Liebana-Cabanillas, F. Big data analytics capability for improved performance of higher education institutions in the Era of IR 4.0: A multi-analytical SEM & ANN perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 173, 121119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, A.; Zare Ravasan, A. How market orientation contributes to innovation and market performance: The roles of business analytics and flexible IT infrastructure. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2018, 33, 970–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Mani, V. Analyzing the mediating role of organizational ambidexterity and digital business transformation on industry 4.0 capabilities and sustainable supply chain performance. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 27, 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]