Abstract

This study aims to conduct a bibliometric analysis of reputational risk and sustainability. The research was conducted using the Scopus database, which returned 88 publications published during 2001–2020, revealing that the amount of research output within this field is limited, and more research output should be conducted in the field of reputational risk and sustainability. We identified nine research streams: reputation risk, reputation risk and sustainability, supply chain management, social responsibility, reputation risk management, strategic approach, sustainable development, corporate sustainability and risk assessment. This bibliometric analysis provides managerial and policy implications for sustainability consideration of reputational risk with perceptions to advance knowledge in this important research field.

1. Introduction

This decade saw a rise in corporate sustainability reporting (Frost et al. 2005), which represents a trend in social and environmental accounting. Sustainability reporting deals not only with the present generation but also with future generations in regards to fiscal, environmental, and social success. Academic literature has established theories that aim to provide an explanatory context for increased accountancy in the social and environmental field, with the latest major development probably being the RRM thesis (Bebbington et al. 2008a).

The validity hypothesis (Parker 2005), perhaps the most prominent of theories, interprets environmental and social accounting as an improvement in traditional accounting and reporting in comparison to more radical theories. The critical legitimacy theory, however, has a lack of precision as Parker (Parker 2005) points out, that the RRM theory has a “greater clarity structure” of reporting purposes as contrasted with the theory of legitimacy in the case of corporate social responsibility (CSR). The study of the RRM proposes that CSR reporting should not only be interpreted as a reputational connection but as part of a corporate-led RRM (Bebbington et al. 2008a). The thesis will allow one to understand the operationalization of the relationship between sustainability and RRM in a business environment.

A mixed analysis of the work of Babington (Bebbington et al. 2008a; Unerman 2000) attacked Adams for not distinguishing himself from the philosophy of legitimacy. The subtle difference is whether or not authority exists, whereas credibility is comparatively significant (Bebbington et al. 2008a). The real point of dispute, though, tends to be that legitimacy can be perceived as relative and has been used for reputation in social and environmental accounting. Babington (Unerman 2000) states that this has happened only rarely in social accounts, although Adams (Adams and Larrinaga-González 2007) insists that “the connections of credibility with news have been extensively examined”. In either case, the researcher suggests that the RRM study will lead to the need, and interpretation “of what happens in organizations, of the dynamics and interdependence of organizational systems, beyond the current theory of lawfulness” itself.

Hopwood (Hopwood 2009) notes that businesses are engaged in using environmental monitoring to “facilitate the creation of a modern and varied business brand”, rather than merely to enhance their credibility. It offers a set of examples that demonstrate that environmental reporting in the industry seems more to concentrate on actual actions and performance than policy (Hopwood 2009). ACCA’s results from Australia and New Zealand (2007) also indicate a commitment to presence rather than action following sustainability studies. It emerges from this that credibility cannot be enough to explain how sustainability reports tend to be more driven by brand and prestige issues than by transparency.

Reputation is the contemporary business’s most important commodity. Well, the known will lead to several promising results. Businesses with a solid, good reputation retain consumers and create market satisfaction, hire and sustain high-level staff, build long-term relationships with vendors, attract new buyers, obtain funding at reduced prices and deter future rivals from joining the industry. Since the investor expects that these businesses will achieve long-term profit and future prosperity, they have higher costs and market values. The respectable valuation varies between 20% and 90% of the overall market value of the company (de Castro et al. 2004). In their report, Wang and Smith (Wang and Smith 2008) contrasted a sample of the sizes of control companies (de Castro et al. 2004) with high prestige (from the list of American’s Most Admired companies). They noticed that the company’s prestige grows by about $1.3 trillion above the average and suggested that the market-value increase is attributed to the high-profile companies’ growth in financial results and lower leverage (lower financial risk). Powerful, optimistic credibility undeniably offers the company certain observable advantages. However, reputation is a double-edged sword: on the one hand, a good reputation brings benefits to all stakeholders and, on the other hand, it places the business at risk of reputation (Eccles et al. 2007). The higher the credibility, the greater the likelihood that its harm would arise. It follows that the demands and aspirations for a highly regarded business are greater than for the one with little opinion. Therefore, any fault or slip is much more and painfully felt in terms of the former. The errors of a reputation-poor subject are best taken or should also be taken. We claim then that such an organization would have been expected. According to the principle “the bigger you get, the higher you fall” (Honey 2009), the businesses with exceedingly high prestige are, thus, burdened with greater risk of liability. If all of the stakeholder groups’ expectations are not met, so the company’s confidence will diminish and credibility will deteriorate. There would tend to be a crisis scenario that has unwanted economic consequences as well as psychological or social effects (Valackienė and Virbickaitė 2011). In light of this, reputation risk detecting and minimizing risk is a priority problem in the control of this risk.

Reputations affect various social circumstances, particularly those where actors make or are obliged to decide (Bromley 2000). These judgments may refer to the appreciation or values assigned to a particular object or person or group of social actors, the trustworthiness and efficiency of local hospitals or investment opportunities, worker performance, the successful care of the individual, the consistency of the teaching in schools or consumer goods brands or whether a meeting or location met their standards. Thus, human judgments and behavior appear to be precipitated by “reputational awareness” and experiences (Bromley 2000).

Once formed, it represents the status or respect of a certain object, individual, social category, commodity, organization, town, and the like (Bromley 2000). The prestige represents a collection of assumptions, principles, and beliefs. Renowned mechanisms are primarily discursive and focused on the sharing of images, perceptions, rumors, listening, and explanations of experience between social actors. The creation and distribution of reputations in social networks and throughout the organizational and social sphere are primarily driven by micro-processes (O’Callaghan 2007). For instance, a big organization with competing and contrast views on a certain reputational object may appear in one field or, if appropriate, several fields. Over time, these perceptions either settle and become accepted and then are constantly repeated or decline over time until they are completely lost or revived by changes in events or situations. For starters, the Bristol tragedy was marked by two opposing sets of convictions regarding the credibility of medical practitioners (Kewell 2006). There are several convictions that child cardiac pediatric procedure is favorable and state that Bristol’s pediatric surgical team’s success is consistent with usual expectations of a “center of excellence”. However, an alternative approach appeared after new physicians and surgeons from other excellence centers in England and abroad, roughly 1988–1994, were admitted to the hospital. These recent entrant experts acknowledged that the success standards of other centers of expertise in the discipline are dangerously short of the fields encountered. These “recruits” to the Bridge Frontier Institute have, importantly, been able to see all the threats that their time-served counterparts cannot see (Weick 1995). This case, thus, highlights the common disparity in social players’ views of prestige, popularity, and esteem. It also highlights the risks of prestige.

Reputations reflect intangible properties especially for large organizations that invest heavily in print management and marketing, but also for people who perform their roles in daily life, such as medical professionals (Bromley 1993). The reputational information—an environment in which reputation and its influence are understood—is fundamental to the “sensory” systems of humans (Weick 1995), and probably forms much of our meetings in the social environment (Bromley 1993).

As a social institute or process by which habits are controlled and by which self-monitoring is used (Granovetter 1985). This especially applies to economic behavior that includes trust-enhancing models of trade and reciprocity in itself (Sasaki 2019).

Reputation serves as a foundation for relations of trust and trade and reciprocity between social players, thus, legitimizing intervention. Faith itself creates generally agreed standards of behavior and helps regulate against open usage by the related stakeholders of activities that are believed to be deviant, disloyal, malfeasant, or immoral (Granovetter 1985).

Reputation also leads to the ethical management of human behavior, by establishing, among other forces, trust and by generating the kinds of reputations that people either strive to or care about—exalted, neutral, indifferent, poor, and dubious (Bebbington et al. 2008a). Here, credibility functions as both a type of authority and a social lever that institutionalizes the understanding and imagery of a reputational entity. In the Bristol Royal Infirmary (BRI) situation, both young and existing medical professionals exploited inconsistent views of credibility to further their agenda. The rhetorical fights between these two also had reputed experiences and photographs (Kewell 2006).

The power dimension is recognized in sociology, particularly in the work of Bourdieu, where it is regarded as a source of capital that helps social actors to obtain economic, social, and symbolic influence in social, cultural, policy, and economic development and regulation (Granovetter 1985). This is the most important feature of society.

Reputation is the signaling impact of a reputation’s ongoing presence among the social processes which lead to the establishment of cultural values, laws, and procedures, as (Granovetter 1985) points out. It also involves institutions and behavior regulates, power relations, and individual mental archetypes. As a result, reputational information is latent in human behavior, and we, thus, behave as second nature. Most notably, it is implicit in the “mental models” and scripts used by social actors to formulate and work through behavior in daily life (Kewell 2007).

It is arguably reputation that is key to creating social risk, as well as the social development of other human relations trends such as economic trade. ‘risk construction as an Act consists of the assembling into mental templates or interpretive schemes of thoughts, assumptions, sensations, pictures, images, impressions, and perception of threats, hazards, customs, and laws that help to decide reasonable and likely irrational modes of behavior, both necessary and associated risks’ (McDonald et al. 2005). As a consequence, risk-building is an interconnected mechanism that involves confidence and credibility, developing mainly through an exchange of discourse on the threats, risks, and probabilities among social players. In the case of BRI, for example, “talk” was mostly about credibility. Histories and gossip were shared to help promote conflictive credibility and, thus, combat the disaster among medical experts (Teasdale 2002). The repeated dissemination and sharing of narratives, hearsay, and evidence, and misconceptions added to the integration and institutionalization of the influence of the crisis on legitimacy.

Therefore, a sense of risk must always be in place in some manner if it is to be socially developed. What social players are there to understand and believe about a person, entity, institution, place, or event who anticipates their view of an object and its risks and opportunities? Remembrance can help decide if this idea becomes dreaded, abhorrent, tempting, secure, or harmful (Kewell 2006). Then, this thought sets the stage for action and, depending on the situation, even inaction.

However, Eccles et al. (2007) state that most businesses handle their reputable risks inadequately. It appears to concentrate its efforts on overcoming the risks already posed to its reputation. The management of crisis a preventive strategy intended to minimize damages is not risk management. Companies do not typically notice or appreciate their reputation until they are harmed or destroyed. Then, they are trying to save and reconstruct it. However, this job turned out to be much simpler than the reputation to be built and sustained. This is illustrated by the study findings carried out between North American, European, and Asian business leaders. To the question: What is the most complicated process in reputation management? Development, restoration, or rehabilitation of reputation? A strong majority (66 percent) of respondents reported restoring their credibility, preserving their reputation 24 percent, and building 10 percent only.

The dramatics of reputational damages noted in recent years have led to the substantial rise in prestige and related risk, with the examples that follow: Enron, Arthur Anderson, World Com., Adelphia, and Tyco. Reputation risk is viewed by management and analysts as the greatest danger to the contemporary business research findings among senior risk managers, who have already been quoted, prove the greatest danger for the enterprise performing on the global market among 13 of the selected risk types. The next positions are regulatory danger, human resources risk, IT network risk, risk to the market, loan risk, nation risk, risk finance, terrorism, foreign exchange risk, natural danger hazard risk, political risk, and crime.

The credibility of the organization is multi-faceted and dynamic. Specialists from several fields, including accounting, economics, sociology, psychology, and marketing, make diverse concepts of science and study (Teasdale 2002). The following two should be cited: “a perceptual reflection of the past operations of the organization and the potential viewpoints that will explain the general appeal that the company is making to all its main components/interests as opposed to the other competitor representatives”. From these concepts come a variety of essential reputational qualities.

Some bibliometric studies on risk assessments and management have been conducted in different study fields. Amin et al. (2019) used the bibliometric methodology to analyze research output on process safety and risk analysis, Fu et al. (2021) analyzed Arctic shipping risk management using bibliometric analysis, Nobanee et al. (2021) used a bibliometric method to analyze research output on sustainability and risk management, and Díez-Herrero and Garrote (2020) analyzed flood risk analysis and assessment research output using bibliometric analysis. Braun et al. (2019) conducted systematic and bibliometric methods to analyze the literature on sustainable remediation through the risk management perspective and stakeholder involvement, Xu et al. (2020) analyzed the existing literature on disruption risks in supply chain management using bibliometric analysis methodology, Ganbat et al. (2018) employed the bibliometric method to review the literature on risk management and building information modeling for international construction, and Han et al. (2020) used a bibliometric overview of research trends on heavy metal health risks. Fuentes Cabrera et al. (2019) applied the bibliometric review methodology to analyze the literature on bullying among teens, ethnicity, and race risk factors for victimization. Darabseh and Martins (2020) used a bibliometric study and content analysis on risks and opportunities for reforming construction with blockchain, and Da Silva et al. (2020) conducted a bibliometric method to review research output on data mining and operations research techniques in supply chain risk management; to the best of our knowledge, we did not find any study that employed the bibliometric method to review existing research output on reputational risk and sustainability. By using 88 documents obtained from the Scopus database and analyzed using the VOSviewer, this research addresses several questions related to reputational risk and sustainability: (i) What is the current publication trend of reputational risk and sustainability research? (ii) What are the most influential documents, countries, authors, and journals of reputational risk and sustainability research? (iii) Which topics themes and streams involving reputational risk and sustainability research are the most recent or common among scholars? (iv) What are the directions for future research in the field of reputational risk and sustainability

2. Methods

We used two bibliometric approaches complementary to this. Both approaches were used to evaluate bibliographical data co-occurrences but at various stages and different outcomes. First of all, co-quotation analysis integrates all records in the scholarly reference list with each other and aggregates them into the number of co-occurrences for each pair of articles (Hummon and Dereian 1989). Therefore, as records appear in the same bibliography, they are co-cited. The study of co-citation should expose the practices of a research field, as the widely referenced articles are more likely than the less commonly cited works to co-cite them. As the number of citations was somewhat time-based, ‘classics’ are prominently included in the networks of co-citation, and form the basis for further study. Therefore, co-quotation analytics are “dynamic” since, after the documents are released, the amount of (co-)quoting is not set but may expand over time (Nobanee et al. 2021).

Secondly, bibliographic partners counted the number of sources exchanged in their bibliographies by two (or more) documents (Hummon and Dereian 1989). In comparison to co-citation analysis at the reference level, the bibliographical combination is the feature of referencing records: two documents are related if they share at least one similar reference. The approach is based on existing and recent works as a result of the independent bibliographical coupling from the numbers of citations obtained. The method is “static”, because after the papers were released, the reference lists do not shift. Therefore, as publishing is conducted, the degree to which records are related is apparent (Nobanee 2020).

These variations contributed to distinct but complementary findings in co-citation analyses and bibliographic coupling. Although the composition of the aggregate data is identical, the raw data in symmetric matrices with records such as column and row headers and the number of co-occurrences with the values were reorganized. In co-quote analyses, columns and row headers (e.g., network notes) were quoted and values (e.g., network ties) were co-quoted to each pair of the document(s). This data structure refers to a network layout. The bibliographical coupling method, on the other hand, contributes to network data with citations as nodes and the number of links as connections (Nobanee 2021). These matrices were then used for feedback for a UCINET version 6.581 network analysis. We used the Girvan–Newman clustering technique (Rindova et al. 2005) and the categorical core/periphery partition to detect subgroups within the networks. The network graphs were generated in the form of a NetDraw 2.153 spring embedding algorithm which found lots of articles in Scopus and analyzed their studies and found the following results.

The visualization of leading authors, countries, documents, organizations, and the most frequent keywords was conducted using the VOSviewer software, (Visualizing Scientific Landscapes) as the main source of analysis. This software was developed by the Leiden University Centre for the Science and Technology Studies in the Netherlands. This software is based on an algorithm called “visualization of similarities” or VOS (Van Eck and Waltman 2020; Lulewicz-Sas 2017; Sarkar and Searcy 2016) The VOSviewer software can present the thematic flow of knowledge and identifying information clusters of the analyzed bibliographic data by possessing common characteristics of authors, countries, documents, affiliations, and occurrence of words (Moed 2010; Zhu et al. 2009; Khatib et al. 2021; Radicchi et al. 2004; Li et al. 2020).

3. Results

This section can be divided into subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Document Regarding Keywords

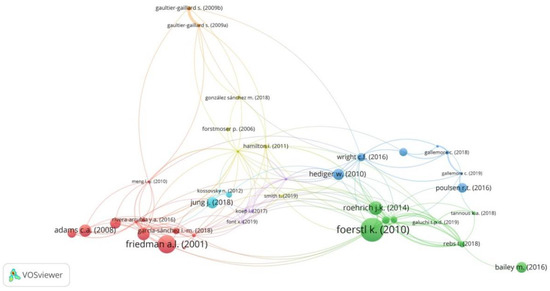

Figure 1 shows the bibliographic coupling network of the most cited documents. This approach is especially suitable to map the study front, as stated in the last section since it is independent of quotes (which only last longer periods). If they share eight or more references with at least three other publications, the nodes representing referenced documents have a relation between them. This threshold was applied to limit the size of the network and to concentrate on scholarly conversations of important interconnections. We extracted the eight research clusters, which are illustrated by various node colors, within this already broad collection of 786 publications. Below, each cluster is listed briefly.

Figure 1.

Document regarding keywords.

Table 1 shows the tabular explanation of the above diagram. Here we can see the name of documents and their number of citations regarding our searched keywords. Figure 2 presents the origins of research papers that can be seen in the following illustration. The concept of corporate integrity is discussed to some degree in all bibliographical coupling network papers. The present study indicates, however, that there is no one-definition consensus (Friedman and Miles 2001). We found that there remains a multi-theoretical basis within the theoretical dimension of corporate reputation research foundations, which ultimately gives rise to the multiple concepts that emerge in recent research (Bailey et al. 2016). A description was the most common finding of the bibliometric review. Lund-Thomsen et al. (2016) concentrate on the signaling impact of the reputation approach towards a resource-oriented reputation as an immaterial commodity that represents fame and respect. Most network work adds other aspects to this concept.

Table 1.

Document regarding keywords.

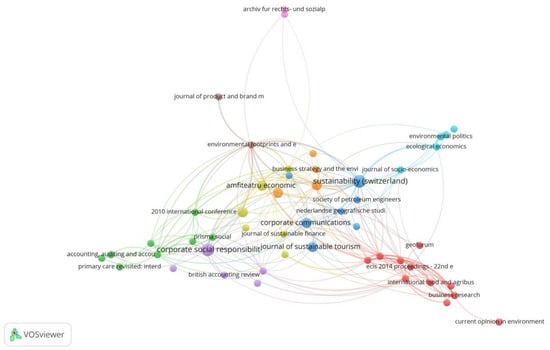

Figure 2.

Sources of research articles.

3.2. Sources of Research Articles

Table 2 also provides publications that include a range of different credibility meanings. Some writers established their credibility definition based on their evaluations. Authors (Vlasic 2012) outlined three concepts: to be known, to be known about something, and to be generalized. The two dimensions of reputation, perceived efficiency and importance, are described by authors (Rindova et al. 2006). Walker (Walker 2010) gives core credibility qualities of perception, the sum of all stakeholders, and comparability as a product of two attributes—consistency of time and a positive to negative continuum. Figure 3 indicates to see those researchers and authors of research studies who have worked on our topic and keywords.

Table 2.

Sources of searched documents.

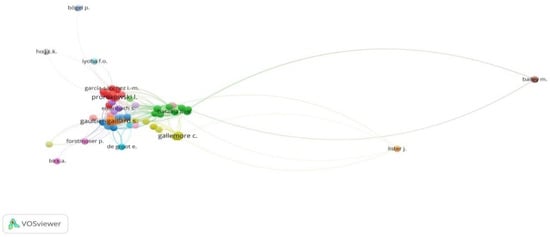

Figure 3.

Search regarding authors.

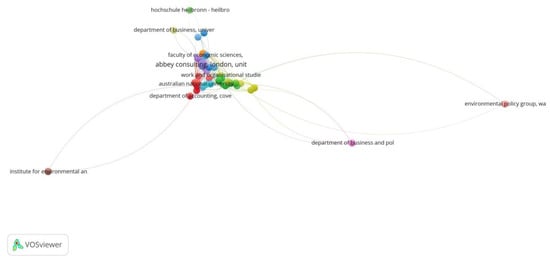

3.3. Organizations Regarding Keywords

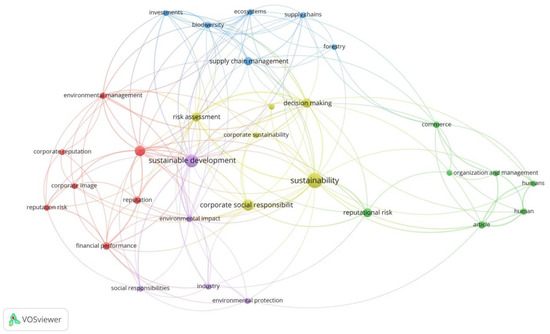

Table 3 presents the names of authors concerning their documents cited in multiple studies as well regarding our keywords, Figure 4 presents the VOSviewer of those organizations who worked on and researched our topic-related keywords. We can see the nodes and their connectivity related to these organizations. Table 4 presents the name of organizations and their citations with the ranks, and Figure 5 shows the keywords searched for publications according to the countries. The nodes show the links regarding our searched keywords. For a static explanation of Figure 5, we see Table 5 which indicates the country-wise searched results regarding our keywords. We can see that in the UK the documents regarding our keywords are 17, which is much higher than in other countries. At the same time, it can also be judged that the rate of citing the articles is also high in that country which is 347. Figure 6 describes the most commonly used keywords to define reputational risk and sustainability documents. The most commonly occurring subjects in the area can be calculated by this research. We looked at the keywords of the writers to carry out the study. We got 520 keywords in our survey (2647 papers). Just 520, which means 52.0 percent, appeared more than once. Specifically, more than 5 times were noticed for 329 keywords, 232 more than 10 times, and just 43 more than 50 times. Table 6 displays these keywords that appear over 20 times. Sustainability is the most recurring keyword for publications in sustainability. In Table 6, the total strength of the links show the number of links between one object and another item and the aggregate strength of links between one item and another. This importance implies that a keyword is significant in the field since a higher value means that it is connected more times with others. These values were used in the VOSviewer to represent the network keyword.

Table 3.

Top cited authors.

Figure 4.

Organizations regarding keywords.

Table 4.

Organizations regarding keywords.

Figure 5.

Country-wise searched result of keywords.

Table 5.

Country-wise searched result of keywords.

Figure 6.

Searched keywords.

Table 6.

Searched keywords.

3.4. Cluster Analysis

Cluster analysis or clustering is the process of grouping a collection of items to make them more like each other in some way than in other groups (clusters) within the same group (called the cluster). The key activity of exploratory data mining is common data processing techniques for many sectors, including pattern recognition, image processing, extraction of information, bioinformatics, image segmentation, computer animation, and machine learning. Our cluster analysis is presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Cluster analysis.

4. Discussion

Various results are worth noting from our bibliometric review; lots of publications and research were studied under Scopus. Next, we see organizational reputation experiments combined with subject-specific conceptualizations in a particular area of study. We are the first to expose and imagine the big picture of management and business studies research on credibility. Secondly, while our research improves and strengthens content reviews for covered literature, our conclusions and observations are confirmed by some of our analyses. For instance, co-citation analyses demonstrate the discipline of credibility analysis in the fields of finance, organizational science, and marketing.The findings of the bibliometric analyses are very real, we assume, because these are reflected in Bergh et al. (Kunitsyna et al. 2018). Not only the theoretical bases but also the value of the neighboring definition, such as image, identification, and status, are seen in the co-citation (Veh et al. 2019). This is important to resolve the gap in the corporate reputation definition since the bibliographic combination study helps one to report the heart and the front line of corporate reputation research systematically. The bibliographic connectivity network demonstrates that current science is primarily observational and contributes to ever-new scientific findings. On the one hand, this results in a build-up of corporate characteristics and perceptions but still contributes to a less accurate concept of what constitutes the image of the business as a whole. Furthermore, derived philosophical work may lead to further organizational credibility study to achieve incorporation.

5. Conclusions

This decade saw a rise in corporate sustainability reporting, which represents a trend in social and environmental accounting. Sustainability reports discuss concerns related not only to current generations, but also to future generations in the economic, environmental, and social sectors.

The purpose of this essay was to explore and encourage the scientific interpretation of the term, research into company credibility in management, and market studies. The sheer degree of credibility analysis in management and business studies indicates that this principle resonates in the academic world. Although available review approaches to narrative techniques are qualitative, we used bibliometric methods to perform a comprehensive review. This method is particularly helpful as detailed literary institutions ask scholars to keep up with a rising range of publications. This specifically relates to the credibility of the company. We have extracted a variety of research maps that include orientation both for expert academics in the field and beginners, based on both history and recent developments, and accompanied by network visualizations. However bibliometric approaches are not substituted for thorough analysis and assessment of the results despite their superior objectivity and repeatability compared with qualitative reviews.

This research offers interesting insights on reputational risk and sustainability. The implications of the findings of our paper provide the basis for new applications of reputational risk and sustainability for business practices. Yet, similar to other studies, our research is affected by some limitations. First, the analyses depended on the choice of keywords. Another selection of keywords might have shown different results (Delafenestre 2019). Second, we relied only on the Scopus database as it is considered the most leading database of peer-reviewed articles, conference proceedings, and book chapters (Khatib et al. 2021). Third, the “Matthew Effect” may also have led to biased findings, when highly cited papers are blindly cited without checking their quality (Luther et al. 2020; Ball and Tunger 2005). In the cluster analysis section and Table 7, we converted the suggestions for future research for the analyzed papers into research questions.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. Conceptualization, H.N., M.A., G.A. and S.A.H.; methodology, H.N., M.A., G.A. and S.A.H.; software, H.N., M.A., G.A. and S.A.H.; validation, H.N.; formal analysis, H.N.; investigation, H.N., M.A., G.A. and S.A.H.; resources; data curation, H.N., M.A., G.A. and S.A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A. and S.A.H.; writing—review and editing, H.N. and M.A.; visualization, H.N., G.A. and S.A.H.; supervision, H.N.; project administration, H.N.; funding acquisition, H.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams, Carol. 2008. A commentary on: Corporate social responsibility reporting and reputation risk management. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 21: 337–61. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, Carol, and Geoffrey Frost. 2008. Integrating sustainability reporting into management practices. In Integrating Sustainability Reporting into Management Practices. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 288–302. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, Carol, and Carlos Larrinaga-González. 2007. Engaging with organisations in pursuit of improved sustainability accounting and performance. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 20: 333–55. [Google Scholar]

- Alix-Garcia, Jennifer, Alain De Janvry, and Elisabeth Sadoulet. 2008. The role of deforestation risk and calibrated compensation in designing payments for environmental services. Environment and Development Economics 13: 375–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amin, Md Tanjin, Faisal Khan, and Paul Amyotte. 2019. A bibliometric review of process safety and risk analysis. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 126: 366–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, Luiz Alberto, and Fernando Vinhado. 2016. Reputational Risk Measurement: Brazilian Banks. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2799248 (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Artiach, Tracy, Darren Lee, David Nelson, and Julie Walker. 2010. The determinants of corporate sustainability performance. Accounting & Finance 50: 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Aula, Pekka. 2010. Social media, reputation risk and ambient publicity management. Strategy & Leadership 5: 943–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, Matthew, Eleanor Simpson, and Peter Balsam. 2016. Neural substrates underlying effort, time, and risk-based decision making in motivated behavior. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 133: 233–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balachandran, Kashi, Paolo Taticchi, Janine Hogan, and Sumit Lodhia. 2011. Sustainability reporting and reputation risk management: An Australian case study. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management 19: 267–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, R., and D. Tunger. 2005. Bibliometrische Analysen: Daten, Fakten und Methoden: Grundwissen Bibliometrie für Wissenschaftler, Wissenschaftsmanager, Forschungseinrichtungen und Hochschulen. Jülich: Forschungszentrum Jülich, Zentralbibliothek. [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington, Jan, Carlos Larrinaga-González, and Jose Moneva-Abadía. 2008a. Legitimating reputation/the reputation of legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 21: 371–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington, Jan, Carlos Larrinaga-González, and Jose M. Moneva. 2008b. Corporate social reporting and reputation risk management. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 38: 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bessa-Gomes, Carmen, Stéphane Legendre, and Jean Clobert. 2004. Allee effects, mating systems and the extinction risk in populations with two sexes. Ecology Letters 7: 802–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Adeli Beatriz, Adan William da Silva Trentin, Caroline Visentin, and Antonio Thome. 2019. Sustainable remediation through the risk management perspective and stakeholder involvement: A systematic and bibliometric view of the literature. Environmental Pollution 255: 113221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, Dennis. 2000. Psychological aspects of corporate identity, image and reputation. Corporate Reputation Review 3: 240–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, Dennis Basil. 1993. Reputation, Image and Impression Management. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Budiman, K., F. Y. Arini, and E. Sugiharti. 2020. Disaster recovery planning with distributed replicated block device in synchronized API systems. In Disaster Recovery Planning with Distributed Replicated Block Device in Synchronized API Systems. Bristol: IOP Publishing, p. 032023. [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Rodríguez, Manuel. 2010. Big auditors, private firms and accounting conservatism: Spanish evidence. European Accounting Review 19: 131–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, Martin, and Helen Peck. 2004. Building the resilient supply chain. The International Journal of Logistics Management 15: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clarkson, Peter, Yue Li, Gordon Richardson, and Albert Tsang. 2015. Voluntary External Assurance of Corporate Social Responsibility Reports and the Dow Jones Sustainability Index Membership: International Evidence. Brisbane: UQ Business School, Unpublished Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- de Castro, Gregorio Martin, Pedro López Sáez, and José Emilio Navas López. 2004. The role of corporate reputation in developing relational capital. Journal of Intellectual Capital 5: 575–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delafenestre, Régis. 2019. New business models in supply chains: A bibliometric study. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 47: 1283–99. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, Juliana Bonfim Neves, Pedro Senna, Amanda Chousa, and Ormeu Coelho. 2020. Data mining and operations research techniques in Supply Chain Risk Management: A bibliometric study. Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management 17: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Deen, Anisah, and Llewellyn Leonard. 2015. Exploring potential challenges of first year student retention and success rates: A case of the school of tourism and hospitality, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. African Journal for Physical Health Education, Recreation and Dance 21: 233–41. [Google Scholar]

- Darabseh, Mohammad, and João Poças Martins. 2020. Risks and Opportunities for Reforming Construction with Blockchain: Bibliometric Study. Civil Engineering Journal 6: 1204–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Herrero, Andrés, and Julio Garrote. 2020. Flood risk analysis and assessment, applications and uncertainties: A bibliometric review. Water 12: 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, Grahame. 2006. Reputation risk: It is the board’s ultimate responsibility. Journal of Business Strategy 27: 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, Grahame. 2014. The curious case of corporate tax avoidance: Is it socially irresponsible? Journal of Business Ethics 124: 173–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, Thomas, and Kai Hockerts. 2002. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment 11: 130–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, Robert, Scott Newquist, and Roland Schatz. 2007. Reputation and its risks. Harvard Business Review 85: 104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El Ansari, Walid, Derrick Ssewanyana, and Christiane Stock. 2018. Behavioral health risk profiles of undergraduate university students in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland: A cluster analysis. Frontiers in Public Health 6: 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fan, Yiyi, and Mark Stevenson. 2018. A review of supply chain risk management: Definition, theory, and research agenda. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 48: 205–30. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, Peter. 2004. Supply chain risk management. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 9: 183–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerstl, Kai, Carsten Reuter, Evi Hartmann, and Constantin Blome. 2010. Managing supplier sustainability risks in a dynamically changing environment—Sustainable supplier management in the chemical industry. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 16: 118–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, Alberto. 2010. How credible are mining corporations’ sustainability reports? A critical analysis of external assurance under the requirements of the international council on mining and metals. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 17: 355–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Andrew, and Samantha Miles. 2001. Socially responsible investment and corporate social and environmental reporting in the UK: An exploratory study. British Accounting Review 33: 523–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Andrew, and Samantha Miles. 2004. Debate papers: Stakeholder theory and communication practice. Journal of Communication Management 9: 95. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, Geoff, Stewart Jones, Janice Loftus, and Sandra Van Der Laan. 2005. A survey of sustainability reporting practices of Australian reporting entities. Australian Accounting Review 15: 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S., F. Goerlandt, and Y. Xi. 2021. Arctic shipping risk management: A bibliometric analysis and a systematic review of risk influencing factors of navigational accidents. Safety Science 139: 105254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes Cabrera, Arturo, Antonio José Moreno Guerrero, José Santiago Pozo Sánchez, and Antonio-Manuel Rodríguez-García. 2019. Bullying among teens: Are ethnicity and race risk factors for victimization? A bibliometric research. Education Sciences 9: 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ganbat, Tsenguun, Heap-Yih Chong, Pin-Chao Liao, and You-Di Wu. 2018. A bibliometric review on risk management and building information modeling for international construction. Advances in Civil Engineering 2018: 8351679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gössling, Stefan. 2020. Risks, resilience, and pathways to sustainable aviation: A COVID-19 perspective. Journal of Air Transport Management 89: 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, Mark. 1985. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology 91: 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guruswamy Damodaran, Rajesh, and Patrick Vermette. 2018. Decellularized pancreas as a native extracellular matrix scaffold for pancreatic islet seeding and culture. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine 12: 1230–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Ruru, Beihai Zhou, Yuanyi Huang, Xiaohui Lu, Shuo Li, and Nan Li. 2020. Bibliometric overview of research trends on heavy metal health risks and impacts in 1989–2018. Journal of Cleaner Production 276: 123249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häni, Fritz. 2007. Global agriculture in need of sustainability assessment. In From Common Principles to Common Practice, Proceedings and Outputs of the First Symposium of the International Forum on Assessing Sustainability in Agriculture (INFASA), Bern, Switzerland, 16 March 2006. Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development, Zollikofen: Swiss College of Agriculture, pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Michael, Stefan Gossling, and Daniel Scott. 2015. The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Harland, Christine, Richard Brenchley, and Helen Walker. 2003. Risk in supply networks. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 9: 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasseldine, John, Aly Salama, and Steven Toms. 2005. Quantity versus quality: The impact of environmental disclosures on the reputations of UK Plcs. The British Accounting Review 37: 231–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Havierniková, Katarína, and Marcel Kordoš. 2019. Selected risks perceived by SMEs related to sustainable entrepreneurship in case of engagement into cluster cooperation. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 6: 1680–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hediger, Werner. 2010. Welfare and capital-theoretic foundations of corporate social responsibility and corporate sustainability. The Journal of Socio-Economics 39: 518–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, Hannes, Martin C. Schleper, and Constantin Blome. 2018. Conflict minerals and supply chain due diligence: An exploratory study of multi-tier supply chains. Journal of Business Ethics 147: 115–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honey, Garry. 2009. A Short Guide to Reputation Risk. Aldershot: Gower Publishing, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood, Anthony. 2009. Accounting and the environment. Accounting, Organizations and Society 34: 433–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Barbara, Linda Van Horn, Judith Hsia, JoAnn E. Manson, Marcia L. Stefanick, Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller, Lewis H. Kuller, Andrea Z. LaCroix, Robert D. Langer, and Norman L. Lasser. 2006. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease: The Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. JAMA 295: 655–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummon, Norman, and Patrick Dereian. 1989. Connectivity in a citation network: The development of DNA theory. Social Networks 11: 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, Dragan, Mia Djulbegovic, Jae Hung Jung, Eu Chang Hwang, Qi Zhou, Anne Cleves, Thomas Agoritsas, and Philipp Dahm. 2018. Prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 362: k3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jain, Nitin, Birgit Stiller, Imran Khan, Vadim Makarov, Christoph Marquardt, and Gerd Leuchs. 2014. Risk analysis of Trojan-horse attacks on practical quantum key distribution systems. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 21: 168–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jukka, Hallikasa. 2004. Karvonenb Iris, Pulkkinenb Urho, Virolainenc Veli-Matti, Tuominena Markku. Risk management Processes in Supplier Networks International Journal of Production Economics 90: 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow, Florence, and James A. Robison. 1996. Long-term satisfying marriages: Perceptions of contributing factors. American Journal of Family Therapy 24: 153–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kewell, Beth J. 2006. Language games and tragedy: The Bristol Royal Infirmary disaster revisited. Health, Risk & Society 8: 359–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kewell, Beth. 2007. Linking risk and reputation: A research agenda and methodological analysis. Risk Management 9: 238–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Omera, Martin Christopher, and Bernard Burnes. 2009. The role of product design in global supply chain risk management. In Supply Chain Risk. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 137–53. [Google Scholar]

- Khlif, Hichem, and Mohsen Souissi. 2010. The determinants of corporate disclosure: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management 18: 198–219. [Google Scholar]

- Khatib, Saleh FA, Dewi Fariha Abdullah, Ernie Hendrawaty, and Ahmed Elamer. 2021. A bibliometric analysis of cash holdings literature: Current status, development, and agenda for future research. Management Review Quarterly 2021: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoepfel, Ivo. 2001. Dow Jones Sustainability Group Index: A global benchmark for corporate sustainability. Corporate Environmental Strategy 8: 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenjan, Joop. 2015. Public–private partnerships for green infrastructures. Tensions and challenges. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 12: 30–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kunitsyna, Natalia, Igor Britchenko, and Igor Kunitsyn. 2018. Reputation risks, value of losses and financial sustainability of commercial banks. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 5: 943–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, Stéphane, and François Coderre. 2013. Determinants of GRI G3 application levels: The case of the fortune global 500. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 20: 182–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Songdi, Louise Spry, and Tony Woodall. 2020. Corporate social responsibility and corporate reputation: A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Industrial and Systems Engineering 14: 1041–45. [Google Scholar]

- Linnenluecke, Martina, and Andrew Griffiths. 2010. Corporate sustainability and organizational culture. Journal of World Business 45: 357–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linterman, Michelle, Wim Pierson, Sau Lee, Axel Kallies, Shimpei Kawamoto, Tim Rayner, Monika Srivastava, Devina Divekar, Laura Beaton, and Jennifer Hogan. 2011. Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells control the germinal center response. Nature Medicine 17: 975–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lulewicz-Sas, Agata. 2017. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Light of Management Science–Bibliometric Analysis. Procedia Engineering 182: 412–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund-Thomsen, Peter, René Taudal Poulsen, and Rob Ackrill. 2016. Corporate social responsibility in the international shipping industry: State-of-the-art, current challenges and future directions. The Journal of Sustainable Mobility 3: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luther, Laura, Victor Tiberius, and Alexander Brem. 2020. User Experience (UX) in business, management, and psychology: A bibliometric mapping of the current state of research. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 4: 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, Kurt, Sonja Grabner-Kräuter, and Sonja Bidmon. 2008. Risk aversion and brand loyalty: The mediating role of brand trust and brand affect. Journal of Product & Brand Management Journal of Product & Brand Management 17: 154–62. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Ruth, Justin Waring, and Stephen Harrison. 2005. ‘Balancing risk, that is my life’: The politics of risk in a hospital operating theatre department. Health, Risk & Society 7: 397–411. [Google Scholar]

- Moed, Henk. 2010. Measuring Contextual Citation Impact of Scientific Journal. Journal of Informetrics 4: 265–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morrish, Sussie, Morgan Miles, and Michael Jay Polonsky. 2011. An exploratory study of sustainability as a stimulus for corporate entrepreneurship. Corporate social Responsibility and Environmental Management 18: 162–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobanee, Haitham. 2020. Big Data in Business: A Bibliometric Analysis of Relevant Literature. Big Data 8: 459–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobanee, Haitham. 2021. A Bibliometric Review of Big Data in Finance. Big Data 9: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobanee, Haitham, Fatima Youssef Al Hamadi, Fatma Ali Abdulaziz, Lina Subhi Abukarsh, Aysha Falah Alqahtani, Shayma Khalifa Alsubaey, Sara Mohamed Alqahtani, and Hamama Abdulla Almansoori. 2021. A Bibliometric Analysis of Sustainability and Risk Management. Sustainability 13: 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, Terry. 2007. Disciplining Multinational Enterprises: The Regulatory Power of Reputation Risk. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donovan, Gary, Andrew Owen, Steve Bird, Edward Kearney, Alan M. Nevill, David W. Jones, and Kate Woolf-May. 2005. Changes in cardiorespiratory fitness and coronary heart disease risk factors following 24 wk of moderate-or high-intensity exercise of equal energy cost. Journal of Applied Physiology 98: 1619–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Orchiston, Caroline. 2012. Seismic risk scenario planning and sustainable tourism management: Christchurch and the Alpine Fault zone, South Island, New Zealand. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20: 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Lee. 2005. Social and environmental accountability research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 47: 777–80. [Google Scholar]

- Patrignani, Claudia, P. Richardson, O. V. Zenin, R. -Y. Zhu, A. Vogt, S. Pagan Griso, L. Garren, D. E. Groom, M. Karliner, and D. M. Asner. 2016. Review of particle physics, 2016–2017. Chinese Physics C 40: 100001. [Google Scholar]

- Posselt, Tim, and Kai Förstl. 2011. Success Factors in New Service Development: A Literature Review. Nürnberg: Fraunhofer Center for Applied Research and Supply Chain Service, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Radicchi, Filippo, Claudio Castellano, Federico Cecconi, Vittorio Loreto, and Domenico Parisi. 2004. Defining and identifying communities in networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101: 2658–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rämet, Jussi, Anne Tolvanen, Ismo Kinnunen, Anne Törn, Markku Orell, and Pirkko Siikamäki. 2016. Sustainable Tourism. Working Paper. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Anne-Tolvanen/publication/292146686_Sustainable_tourism/links/56aa730d08ae8f38656638b7/Sustainable-tourism.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Reuter, Carsten, Foerstl Hartmann, and Constantin Blome. 2010. Sustainable global supplier management: The role of dynamic capabilities in achieving competitive advantage. Journal of Supply Chain Management 46: 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindova, Violina, Ian Williamson, Antoaneta Petkova, and Joy Marie Sever. 2005. Being good or being known: An empirical examination of the dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of organizational reputation. Academy of Management Journal 48: 1033–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rindova, Violina, Timothy Pollock, and Mathew Hayward. 2006. Celebrity firms: The social construction of market popularity. Academy of Management Review 31: 50–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roberts, Kathryn, Yongjin Li, Debbie Payne-Turner, Richard C. Harvey, Yung-Li Yang, Deqing Pei, Kelly McCastlain, Li Ding, Charles Lu, and Guangchun Song. 2014. Targetable kinase-activating lesions in Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine 371: 1005–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Roehrich, Jens, Michael Lewis, and Gerard George. 2014. Are public–private partnerships a healthy option? A systematic literature review. Social Science & Medicine 113: 110–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, Soumodip, and Cory Searcy. 2016. Zeitgeist or chameleon? A quantitative analysis of CSR definitions. Journal of Cleaner Production 135: 1423–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, Masamichi. 2019. Trust in Contemporary Society. Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Schwemmer, Martin, and Annemarie Kübler. 2016. The logistics profile of the German chemical industry. Journal of Business Chemistry 13: 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Daniel, Stefan Gössling, C. Michael Hall, and Paul Peeters. 2016. Can tourism be part of the decarbonized global economy? The costs and risks of alternate carbon reduction policy pathways. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 24: 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, Richard. 2000. Tourism and sustainable development: Exploring the theoretical divide. Journal of Sustainable tourism 8: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, Tom D., Chris Doucouliagos, and Stephen B. Jarrell. 2008. Meta-regression analysis as the socio-economics of economics research. The Journal of Socio-Economics 37: 276–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Kun, Rui Wan, and Victor Y. Song. 2018. Pyramidal structure, risk-taking and firm value: Evidence from Chinese local SOE s. Economics of Transition 26: 401–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaffield, Joanne, David Evans, and Daniel Welch. 2018. Profit, reputation and ‘doing the right thing’: Convention theory and the problem of food waste in the UK retail sector. Geoforum 89: 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Täube, Florian, Florian Schock, and Michael Migendt. 2012. The role of capital types for firm evolution in nascent industries: Examining entrepreneur-vc nexus and public policy influence in cleantech (summary). Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 32: 8. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Christopher S., Joshua D. Zimmerman, and James I. Nelson. 2009. Managing New Product Development and Supply Chain Risks: The Boeing 787 Case. Milton: Taylor & Francis, pp. 74–86. [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale, G. M. 2002. Learning from Bristol: Report of the public inquiry into children’s heart surgery at Bristol Royal Infirmary 1984–1995. British Journal of Neurosurgery 16: 211–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, Linda Lisa Maria, and Hanna Leipämaa-Leskinen. 2015. Pre-loved luxury: Identifying the meanings of second-hand luxury possessions. Journal of Product & Brand Management 24: 57–45. [Google Scholar]

- Unerman, Jeffrey. 2000. Methodological issues-Reflections on quantification in corporate social reporting content analysis. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 13: 667–81. [Google Scholar]

- Unerman, Jeffrey. 2008. Strategic reputation risk management and corporate social responsibility reporting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 21: 362–64. [Google Scholar]

- Valackienė, Asta, and Rūta Virbickaitė. 2011. Conceptualization of crisis situation in a company. Journal of Business Economics and Management 12: 317–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Eck, Nees Jan, and Ludo Waltman. 2020. VOSviewer Manual. Leiden: Univeristeit Leiden, pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Vlasic, Goran. 2012. Concept of Reputation: Different Perspectives And Robust Empirical Understandings/Koncept Ugled Poduzeca: Teorijske Perspektive I Empirijski Pokazatelji. Trziste=Market 24: 219. [Google Scholar]

- Veh, Annika, Markus Göbel, and Rick Vogel. 2019. Corporate reputation in management research: A review of the literature and assessment of the concept. Business Research 12: 315–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, Kent. 2010. A systematic review of the corporate reputation literature: Definition, measurement, and theory. Corporate Reputation Review 12: 357–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Helen, Stefan Seuring, Joseph Sarkis, and Robert Klassen. 2014a. Sustainable operations management: Recent trends and future directions. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Helen, Stefan Seuring, Joseph Sarkis, Robert Klassen, Jens K. Roehrich, Johanne Grosvold, and Stefan U Hoejmose. 2014b. Reputational risks and sustainable supply chain management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 34: 695–719. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Kun, and Murphy Smith. 2008. Does corporate reputation translate into higher market value? Journal of Strategic Marketing 18: 201–21. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Olaf, Roland W. Scholz, and Georg Michalik. 2010. Incorporating sustainability criteria into credit risk management. Business Strategy and the Environment 19: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, Karl E. 1995. Sensemaking in Organizations. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Chris F. 2016. Leveraging reputational risk: Sustainable sourcing campaigns for improving labour standards in production networks. Journal of Business Ethics 137: 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Song, Xiaotong Zhang, Lipan Feng, and Wenting Yang. 2020. Disruption risks in supply chain management: A literature review based on bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Production Research 58: 3508–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Suzanne, and Swati Nagpal. 2013. Meeting the growing demand for sustainability-focused management education: A case study of a PRME academic institution. Higher Education Research & Development 32: 493–506. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Shanfeng, Ichigaku Takigawa, Jia Zeng, and Hiroshi Mamitsuka. 2009. Field Independent Probabilistic Model for Clustering Multi-field Documents. Information Processing and Management 45: 555–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).