2. Theory Underpinning Methodologies of Calculation

Both explicit debt and pensions are serviced by national productive capacity and both are deducted from production, before that is available for other uses. These are outflows from production, in a way that is very similar to debt service.

This similarity is often ignored, appealing to legal differences between bonds and pension promises. While debt is certain and contractual

2, pensions are contingent and uncertain. Regardless of this aspect, pensions are like bonds: a contributor earns the right to a lifelong income stream

3. This analogy argues for the two types of debt to be expressed in common units at a point of time.

Feldstein (

1974), used life cycle consumption theory to derive a concept of social security wealth juxtaposed to measured wealth; his measure included valuation of the flow of PAYG pensions as a stock.

Understanding, valuing, and communicating outstanding promises are issues important for firms, but also for sovereign states.

As far as firms are concerned, employer-sponsored plans, especially if underfunded, could operate as cheap employment remuneration and could disguise a firm’s true performance. The International Financial Reporting Standards-19

4 sets out how firms should report and service outstanding debt commitments (

Tinios 2011). Pension obligations are treated as loans granted to the firm by the workforce, the future beneficiaries. This loan must be serviced and represents a current charge on the operating account. All quoted firms in the EU need to account for pension commitments. However, no such disclosure obligation exists for State pensions, whether funded or unfunded (PAYG). The equivalent stock measure (Public Sector Accounting Standards 39

5), is only used sporadically by European countries, such as Austria, Spain, and Sweden (

Schmidthuber and Hilgers 2019).

As far as the State system is concerned, expressing PAYG public pensions comparably to prefunded pensions stumbles on theoretical considerations. PAYG is by nature ‘myopic’; funds will be collected only when needed. This treats pension promises similarly to current consumption; no forward provision is made, say, for food, even though we are certain to need it. In this way, should we examine obligations existing today, future pensions are bound to be unfunded; uncovered obligations should surprise no one. However, as

Barr (

2001) states, the issue concerns the future tax capacity of the State

6. If that is unlimited or, at least not constrained, there should be no need to worry about the existence of future claims on it. If, however, we suspect that either tax capacity is limited or if there are bounds to how far or how quickly taxes can be raised to pay for future pensions, prudence argues for planning ahead. This means being able to aggregate obligations arising from explicit debt with implicit ones generated by pension promises.

This point implies that interpreting valuations of outstanding obligations is not exhausted either by legal or by accounting considerations; instead, it should be a matter of judgment, taking into account future potential and societal priorities. The question of sustainability thus needs to be approached in a wider spirit; quantification should play a key role, though it should ultimately be subject to judgment.

However, it may be, the methodology is clear: Expenditure projections, if available, must be set against expected revenue, in a fashion analogous to how companies record their pension obligations. The crucial decision is how to deal with counterfactuals. The method, essentially, would stand bond finance practice on its head: unlike debt, where the stock of debt leads to a flow of debt servicing, we start by projecting flows, i.e., computing flow deficits/surpluses. We would then need to aggregate by discounting to calculate a stock of outstanding implicit debt. This can be compared to outstanding debt obligations to give an estimate of total commitments. Given the centrality of debt in the motivation of the exercise, maintaining comparability between the two debt concepts—explicit and implicit—should play a role in deciding details of the methodology.

We would therefore need to proceed in two steps:

The first step is to calculate flow excess cash requirements—by subtracting pension promises from earmarked (dedicated) revenue. We here treat expenditure as senior—the opposite of the usual PAYG logic of state pensions. We assume that, once a promise is legislated, it needs to be kept; this allows us to use the characteristics of the pension system to cost a time structure of promises. The question of which promises can be taken as firm determines the nature of actuarial models to be used. We can understand this process, alternatively, as progressively widening the groups to whom promises are examined. We start from those already collecting a pension; we add to them those currently working; finally, the widest definition includes all those who will work in the future if the system continues in its current form. The latter assumption (open population) is coterminous with a requirement that a system must be sustainable for the foreseeable future, which can be taken as a requirement for the system operator.

Expenditure needs to be balanced with dedicated revenue

7. That is more uncertain, as it depends on future tax capacity, itself dependant on the existence of other claims, such as explicit bond debt. What we need to capture is how far meeting obligations in the future demands additional fiscal effort. Though ‘extra future effort’ is a matter of judgement, a legal approximation interprets firm commitments of resources as funds not necessitating new legislation to increase revenue. The legal viewpoint could appeal to a government rationality assumption: when a legislature passes a tax to cover a future obligation, its continued collection over time should not be in question. Any foreseeable deteriorations, such as demography must have been factored in

8.

Can this legal approach accommodate the notion of needing additional fiscal effort? Deciding what does and what does not demand extra effort calls for judgment, which sometimes may override official pronouncements. Otherwise, any shortfall could be made up by fiat—substituting wishful thinking for economics

9. Similarly, if international comparisons are attempted, coordinated assumptions are called for—otherwise any ‘problem’ could be solved by choosing the right assumptions. We should thus approach the definition of ‘revenue’ with a critical eye.

The second step in the calculation involves aggregation, turning flows into stocks. This process must be guided by the need to examine implicit together with external debt. Discounting is a key influence. On the one hand comparisons with external debt (and dynamic efficiency) argue for positive discount rates. On the other, dealing with the interests of future generations in welfare economics implies lower (or even zero) discount rates

10. In any case, at this stage of the discussion, it is important to be aware of the salience of discount rates, and hence consider a range of rates.

Operationalising the concept of implicit debt, R. Holzmann argues in favour of explicit IPD calculations by expanding generational accounting through modelling pension systems. He also considers the use of implicit debt as a measure of the ambition and effectiveness of pension reform. (

Holzmann 1990;

Holzmann et al. 2004;

Deboeck and Eckerfelt 2020).

Franco (

1995) considers which promises can be taken as firm and unalterable. He distinguishes

three concepts of liability which correspond to three progressively widening actuarial models:

Accrued-to-date liabilities (ADL). Obligations granted already for work already supplied plus pensions due to current pensioners.

Closed group liabilities (CGL)—adds to ADL future obligations to those currently working.

Open group liabilities (OGL)—adds to CGL all who will work in the future (open population)

The appropriate assumption as to scope depends on who is doing the projection and for what purpose, as these considerations determine the appropriate view as to which decisions can be taken as given exogenously.

For example, Eurostat generalises from National Accounts methodology which necessitates accounting for the implications of observed past events. The new ESA, includes ‘Table 29’, which catalogues estimates for 2015 (

Eurostat 2018). This publishes for all EU member states Accrued to Date Liabilities for all unfunded social insurance schemes and for General Government Employees (see

Deboeck and Eckerfelt 2020 and the next section).

Arguably, when the projection is conducted by the system operator (the State), interest shifts in the continued operation of schemes; it thus focuses on issues of fairness and sustainability. This is because the State has an ongoing constitutional obligation to provide social insurance for the foreseeable future, if not in perpetuity.

IAA (

2018) outlines other limitations of a closed group approach: an inability to assess the full impact of pension reforms, pension scheme maturity, and bias for or against a particular financing approach. Two systems with the same accrued-to-date obligations on a closed-group can have very different sustainability issues, especially if demographics differ. In these cases,

only OGL should be appropriate.

Variations of this methodology have been applied in many studies, for example:

Hagemann and Nicoletti (

1989);

Van den Noord and Herd (

1993);

Kuné et al. (

1993),

Chand and Jaeger (

1996);

Kane and Palacios (

1996),

Frederiksen (

2001),

Kuné (

2000),

Holzmann et al. (

2004),

Heidler et al. (

2009),

Novy-Marx and Rauh (

2011),

Beltrametti and Della Valle (

2011), and

Ponds et al. (

2012) for a variety of contexts. Of particular importance are studies on the EU which will be compared later on, namely

Obořil (

2015),

Doležal (

2012),

Kaier and Müller (

2013), and

Soto et al. (

2011). Special attention will be accorded in what follows

Deboeck and Eckerfelt (

2020), whose starting point, the 2018 EU Ageing Working Group (AWG) projections, coincides with the 2018 calculations of the current study.

Comparisons are difficult, due to divergences in coverage, time frames, discounting but also assumptions on demographics, macroeconomics or future wage growth. An important difference is how future wage growth is treated: Projected Benefit Obligation (PBO) fully accounts for expected increases whereas Accrued Benefit Obligation (ABO) is more conservative, disregards them, and typically yields lower estimates. Differences in inflation assumptions and the range of pension features captured (e.g., disability, survivors, past reforms, indexation) must be added to these. The next section discusses findings of studies of European data conducted in the last decade, in order to gauge the extent to which IPD has been brought under control.

3. Using EU Ageing Working Group Projections to Calculate Implicit Debt

The Ageing Working Group (AWG) of the EU was set up by DG ECFIN in 2000 to coordinate long term fiscal policy. After 2001 it was incorporated in the process of the Open Method of Coordination of the Lisbon strategy (

Tinios 2012). Representatives of Member States coordinate national projections of ageing-related expenditure linking them to demographic projections, and employing comparable and internationally consistent assumptions. Though emphasis is placed on the largest item, pensions, projections also cover other ageing related public expenditure, namely health care, unemployment, long term care and education; of these, only the last is systematically related to population ageing negatively.

AWG projections have three key characteristics which enable their use in IPD calculations: they come with the authority of system operators (1), who are publicly answerable for the results (2) and who have legal and constitutional responsibility for the continuity of the systems projected (3). The three characteristics together dictate that the logic of the projections is squarely that of

open groups (OGL) employing PBO methodology—i.e., that systems need to be sustainable for the foreseeable future, taken to be at least 40 years ahead

11.

The political rationale of the Open Method of Coordination is for member states to engage in a structured exchange with their peers on how they each propose to meet agreed targets—in this case, adequacy and sustainability of pensions. The AWG projections, as a basic input in this procedure, could be interpreted as providing a kind of ‘a statement for the defence’—i.e., how far does the system operators themselves think that conflicting considerations and outstanding questions have been addressed to date, taking into account all actions and legislation already taken (

James 2012).

Projections are published every three years, containing expenditure and (earmarked) revenue. These can be manipulated to yield flow estimates of annual cash shortfalls, a quantity roughly equivalent to debt servicing of explicit measured debt. They can then be aggregated and discounted to yield estimates of the IPD for all countries participating in the AWG exercise.

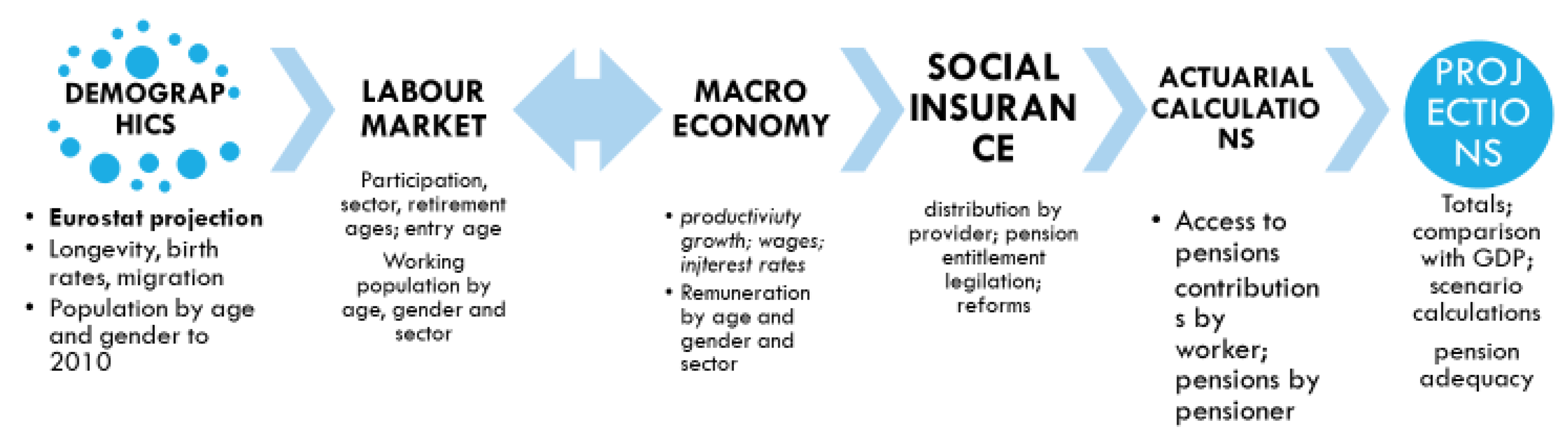

Figure 1 outlines the logic of the AWG projections. The key drivers are demographics for each country, relying on a common source, Eurostat; these are supplemented by labour and macroeconomic assumptions (provided centrally by the EU Commission and agreed with the member states), before handing over the modelling of each pension system to the Member State (MS) responsible for its operation. It is these projections which, after being peer reviewed by other MS and the Commission, are published centrally by the EU. The projection cycle means that if data are published in May of year n, institutional and legal detail corresponds to the situation in December of year n − 1, and pension system data to December of year n − 2.

‘System revenue’ is defined by the AWG as already legislated revenue legally earmarked to finance pensions. The

published information consists of revenue totals. However,

Deboeck and Eckerfelt (

2020), investigating the 2018 round, used its—publicly unavailable—constituent parts. These distinguish employers’ and employees’ contributions, government grants and other dedicated revenue. In order to calculate their net concept of debt, they subtract from expenditure flows

only sums corresponding to contribution revenue, while they disregard other system revenue which the member states themselves had used as offset. In this way, their restrictive definition of system revenue will, arguably, yield a pessimistic picture of future challenges, given that it disregards sources of revenue which are

already used to finance pensions. If our theoretical criterion is tax capacity, it is reasonable to assume that in those cases government grants are an established feature of the budget, continued payment in the future will have been anticipated. Exclusion of government grants will in this case will underestimate tax capacity, thus providing fiscally safer results for the respective member states.

Deboeck and Eckerfelt (

2020) acknowledge this difficulty by excluding Belgium altogether, while Denmark and Finland are dropped as outliers. On other countries where budget relief has recently been legislated, without budgeting the needed fiscal space, unrealistically low IPDs may be found.

When attempting to reproduce

Deboeck and Eckerfelt’s (

2020) results for the 2021, quite apart from the practical consideration that the breakdown of revenue into components is

not publicly available, we need an assumption that (a) allows the full sample of countries to be used and (b) leads to results roughly comparable to debt servicing of government bond.

If we follow

Barr (

2001) to focus on tax capacity, it is reasonable to depart from this restrictive definition of revenue and encompass all revenue cited by the MS or at least those parts which can be said not to entail extra tax effort. In other words, it is preferable to depart from a

legal definition of earmarked revenue, to one which attempts to capture added fiscal effort—whether

new taxes or other revenue need to be imposed. The notion of tax capacity, moreover, allows us to approach outlying cases and hence to arrive at IPD estimates for all member states participating in the AWG exercise.

If we are to produce estimates for all member states, adjustment is necessary for four cases

12: First, in Denmark, first pillar pensions have historically always been financed out of general revenue. As this is not earmarked in law, the totality of pension flows appears as unfunded. However, it is reasonable to presume that an amount regularly budgeted for decades would pose no challenge to taxable capacity. This should certainly apply to the base year proportion of GDP devoted to pensions; this can reasonably be judged as part of system revenue equivalent contribution. At the other extreme, Greece assumes that all social pensions are to be covered by an ad hoc government grant. This interprets a legal requirement passed in 2016 but never to date implemented: government grants after 2016 are financed out of borrowing, as was the case for over a decade (

Tinios 2020). If we are to be consistent with a tax capacity definition, we need to revise published AWG revenue projections for Denmark upwards and for Greece downwards. Indeed, we assume that DK only must finance sums over and above current levels of first pillar finance (as percentage of GDP); for Greece, we subtract government grants from total revenue. The third case is

Finland. The Finish first pillar system, centred on a social pension as in Denmark, is now complemented by a funded component. The AWG adds this to system revenue without any adjustment to the general revenue contribution, with the result that the country shows a large surplus (over 3% of GDP) for the entire period, an extent of savings which defies belief. To correct this, we assume that 2018 fiscal effort remains constant as a percent of GDP, leading to smoother, though still positive flows. Finally,

Belgium does not report any system revenue. In a similar vein, we impute a constant percentage GDP, that of the base-year, to correspond to a given fiscal effort.

Looking at the projections in greater detail, there are three key drivers (

Table 1):

Demographics: Eurostat 2019 projections show dependency ratios deteriorating sharply in the period to 2040.

Labour: the total employment rate in the EU rises from 71.1% in 2016 to 75.8% in 2070. This is due to women and older workers being assumed to work more (6.9 and 12.6 percentage points, respectively) and hence acts to counterbalance demographics.

Productivity growth: rises after 2025 anticipating technological changes as well as catching up, especially in the decade to 2030.

As stated earlier, the Ageing Working Group was set up at the turn of the century to focus on longevity, as the key demographic challenge. To allow such a focus it was necessary to adopt, to the extent possible, neutral assumptions on net migration. The volatility of migration flows, the balance between intra-EU and third-country migration combines with political sensitivities to make taking a credible account of the impact of migration an even more difficult undertaking. In the event, the 2021 report assumes that annual net migration inflows will fall gradually over the very long term. They are projected to decrease from about 1.3 million people in 2019 to about 1 million in 2070 (0.2% of the EU population). However, there are large differences between Member States. According to (

EPC 2020) the methodology used in projections for migration is far more reliable in 2021 comparing to 2018 round, making the methodology more robust. However, the authors maintain that the impact of migration on future pension finances in the EU should be a subject meriting a dedicated report that further clarifies and allows for better assumptions in the near future.

Labour and productivity counterbalance the deterioration in demographics to lead to overall positive GDP average growth. Inflation is constant at 2%. Looking at differences by decade, the most challenging period is that between 2030 and 2040. The demographic deterioration is pulling things down, caused by the retirement of the baby boom generation and the impact of two generations’ worth of low fertility. Moreover, the assumed aid coming from the rise in productivity growth (due to technology advances) has not yet kicked in. In contrast, things are well on the way to improvement by 2050.

Averages disguise considerable variability between member states, which is ultimately responsible for the emerging structure of IPDs.

Table 2 summarises variability in the key drivers in the crucial two decades to 2040. We cite divergences in the key representative indicators of life expectancy, female participation and labour productivity. An idea of the dispersion in EU experience, which powers divergences, is gleaned by citing averages of the five top and bottom performers.

In terms of demographics, longevity is increasing strongly across Europe, while dependency ratios are deteriorating rapidly. A key countervailing influence comes from rises in labour participation. These are motivated by women’s greater involvement in paid labour (larger in the current laggards, EL and IT), which together with a rise in employment of older workers, lead to large jumps in total participation rates. Productivity growth reflects some catching up after low performance in the decade following the 2009 debt crisis plus an assumed process of convergence. However, it is not enough to counter negative demographics leading to negative GDP growth rate for the first decade.

Though it is hard to generalise, the overall impression is that assumptions probably err on the side of optimism. While the demographic drivers cannot be disguised, they are assumed to be softened by gains in female participation, older workers, convergence between member states and technology evolution. IPD estimates must therefore be assumed to be at the lower end of possible calculations.

A word of caution is warranted about the effect of the pandemic. This found the projection cycle half-way, which explains why its long-term impact is largely absent from the baseline projections. GDP, labour participation and pension system data are those of base year 2019, so capture the pre-pandemic situation and macroeconomic expectations. Similarly, demographic projections were completed in early 2020 and therefore contain no impact on life expectancy and other demographic parameters. However, in the published report, the AWG includes two post-pandemic scenarios, a lagged recovery scenario, which presumes a limited impact on potential growth after the initial ‘hit’, and an adverse structural scenario, where the pandemic affects productivity growth in the long term. While the impact of those scenarios on IPDs are not analysed, the report itself notes the high dispersion and different resilience of the member states, especially in the adverse structural scenario.

Proceeding to our calculations and starting from the contribution and benefit expenditure for the years 2020–2060, we derive the difference (Contributions–Benefits) for each year, which is a measure of cash shortfalls

13. As both revenue and expenditure are used, this exercise is squarely in the logic of Open Groups calculation involving future generations and calculations up to 2060. We calculate these differences for the 2018 and 2021 rounds of the AWG. In order to compare the two rounds, we ignore information for the years before and including 2019, for the purposes of comparability as well as to be able to compare with point estimates of bonds outstanding (explicit debt).

The publication released by the AWG in May 2021 enables us to compute assumed cash shortfalls—by the simple expedient of subtracting projected expenditure from revenue—which presumably will have to be made up by the government in due course. It is interesting—and a comment on political sensitivities—that this simple arithmetical calculation is not to be found in the AWG publication itself. This calculation was presented by (

Symeonidis et al. 2020) and published around the same time in an institutional paper by the Commission (

Deboeck and Eckerfelt 2020), for the first time about two years subsequently to the publication of the Aging Report 2018 and using the 2018 projection. The presentation and paper were independently created by the two teams of authors, but coincided, a fact that may indeed prove the increasing interest of the implicit debt in government economies.

The results are on a nominal basis. The AWG figures include an assumption of 2% inflation common for all countries through the projection period, which buoys revenue and allows the simulation of the impact of different pension indexation provisions. If we compare explicit bond debt with pensions, the influence of inflation would be a key differentiating factor: rising inflation would reduce the burden of debt service while (through indexation) it would increase the pension bill. It would therefore affect the relative dynamic behaviour of the two different kinds of debt—implicit and explicit.

Actuaries habitually express magnitudes in real terms. We therefore have expressed all values in constant 2019 prices and then used discounting. However, given that inflation is assumed to be common across the EU27, our choice to use real magnitudes is simply equivalent to using a discount rate higher by 2%.

Deboeck and Eckerfelt’s (

2020), in contrast use nominal amounts, a choice which allows easier comparisons with debt service. However, as inflation is common for all at 2%, it operates in the same way as a higher discount rate. Thus, 5% discounting of nominal magnitudes (D&E’s choice) is equivalent to discounting real magnitudes by 3%.

To aggregate flows into a stock of IPD, we discount using a

range of discount rates. To maintain comparability, we illustrate using discount rates used in the literature viz. 0%, 2% (Baseline), 3%, 4%. The influence of discounting would be evident where there is a succession of deficits and surpluses, in which case this time structure will be weighted in a different way depending on which rate is used. Higher discount rates would reduce the influence of distant surpluses or deficits

14. In contrast, in countries where deficits do not display variability, the impact would be more uniform.

An important issue is how far revenue corresponds to tax capacity. The Member States in supplying information to the AWG were instructed to apply a strict legal definition—i.e., whether a revenue item had been legislated as due to the pension system. This creates a difficulty if we are to interpret this as tax capacity, exemplified by the two polar cases—Denmark and Greece

15, referred to already. Denmark’s social pension has always been financed by general revenue while Greece’s new ‘national pension’ is financed by borrowing by the central government. To safeguard our interpretation of constant tax capacity we undertook two opposite adjustments: We supposed that Denmark’s tax capacity remains at the share of GDP devoted in 2019 to finance universal pensions (9.8% of GDP for 2018 Round, 9.2% for Round 2021). Greece was assumed not to receive government grants (5.8% of GDP for the year 2019 in Rounds 2018, 2021), retaining only social security contributions and other fund income. Finland’s data is adjusted in line with Denmark (3% of GDP for 2018 data, adjusted by the state in 2021), while a flow of revenue equivalent to 2019 expenditure is imputed for Belgium.

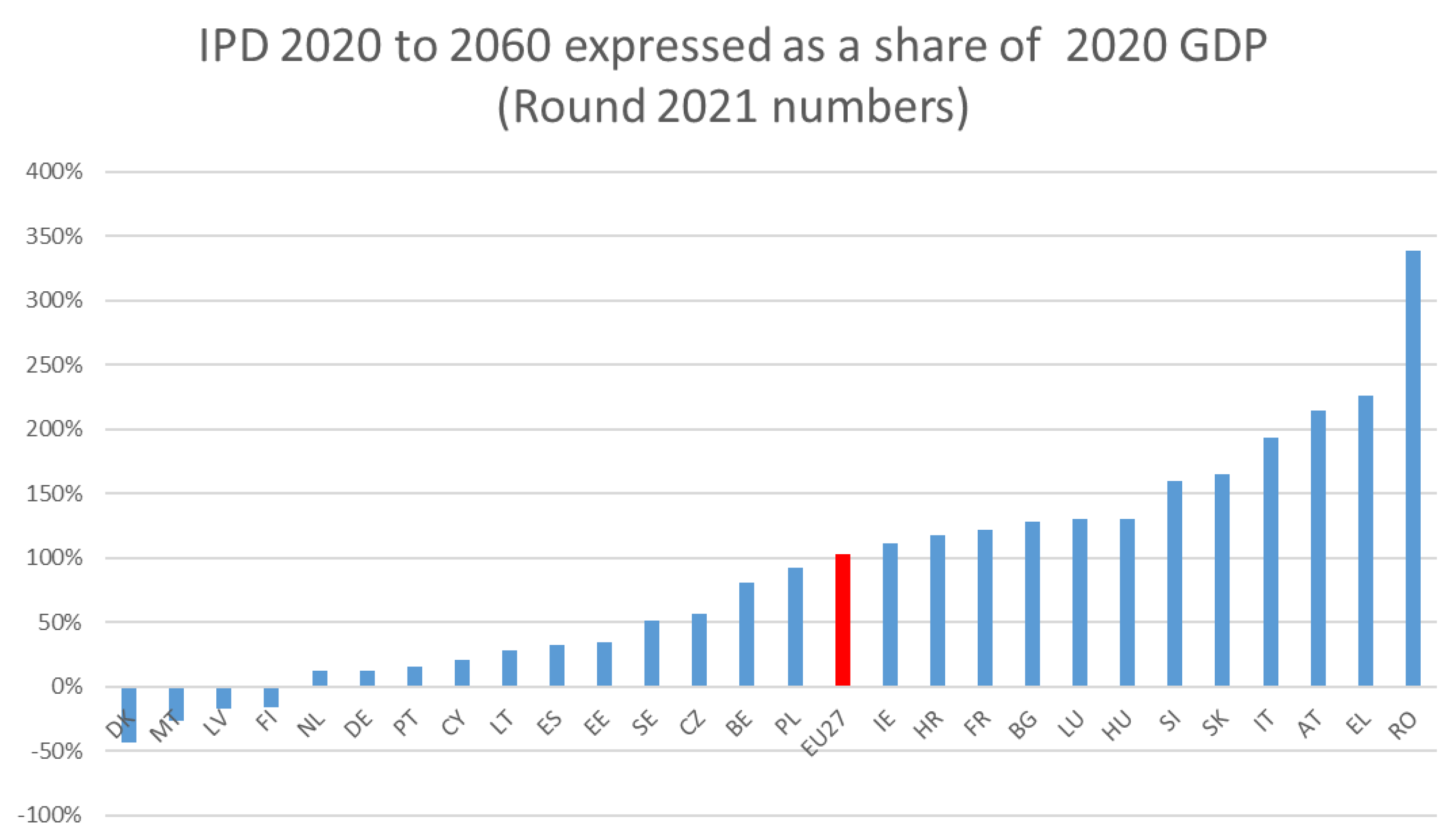

The histograms in

Figure 2, using a 3% discount rate, show the result of the IPD calculation for the 2021 projection round. However, it may be, the IPD calculated certainly is of a size that cannot be ignored. For a minority of countries (DK, MT, LV, FI, NL, DE, PT, and CY) IPDs are below 20% of GDP. For a further seven countries they are between 30% and 100% of GDP (LT, ES, EE, SE, CZ, BE, and PL). For the rest of the countries the IPD is more than 100% of GDP, including EU27, while for Greece (adjusted) and Romania the amounts are well above 200% and 300%, respectively.

The figure shows the tax capacity adjusted data for the four countries already mentioned. The impact of the correction is shown in

Table 3: Denmark’s computed IPD falls from the outlier figure of 320% of GDP to a surplus of 43% (universal pensions do not fully keep up with GDP growth) for Round 2021. Greece moves from a small gap of 27% to a sizeable financing gap (226%).

It is worth noting here that Greece recently voted for a new funded scheme in its first pillar of pensions. As this has been the first attempt for this country, the expected results have not been investigated in academia yet. However, a similar exercise has been attempted in (

Symeonidis et al. 2021).

IPD is, as expected sensitive to the discount rate. With 0% discount rate 17 countries are found to have IPD more than 100% of GDP, a number which falls to 14 if 3% is used. Given that the majority of countries have deficits consistently throughout the period, discounting does not change the rank order of countries—which would have been the case had there been more countries where surpluses are interposed with deficits and vice versa. Results are provided below in

Table 4.

How do the results compare to the 2018 round? This round’s IPD was computed by

Symeonidis et al. (

2020), using identical assumptions to the ones used in this paper. The results for the two separate rounds are shown in

Table 5. We see that the average IPD for the 2% baseline has risen to 246%, from 149% in 2018 (median from x to y), a difference which is larger still if we take lower discount rates. At the 3% discount the figure is almost double.

What can account for such a large effect? Comparing the three key drivers, we see that if anything the 2021 projection should be better not worse; labour productivity growth is slightly higher in the newer projection, while demographics are substantially unchanged. The deterioration must therefore be due to the performance of the pension system. A few examples of that are referred to later in the text.

It needs to be stated that the calculations for 2018 are in accordance

Symeonidis et al. (

2020). As far as the calculation of

Deboeck and Eckerfelt (

2020), who use the same AWG projections, are concerned, a number of considerations should be borne in mind. Both calculations are OGL and apply PBO. However, their published ‘

gross IPD’ only refers to

expenditure and does not subtract expected revenue. Their ‘

net’ IPD only counts employees and employers’ social insurance contributions and disregards other sources of revenue—mostly government grants. Our own calculations are limited to using publicly available data, which consists of what governments

themselves regard as system expenditure. This is certainly more generous, but, as the example of Denmark shows it can be a better measure of future tax capacity, as the point of reference we

actually employ is whether revenue is

currently being used to fund pensions. Our estimate can thus be interpreted as a lower bound for the necessary additional tax effort needed in the future

16. To these we must note some other differences: we start our projections for 2020 and disregard previous deficits, to count only future deficits, while our benchmark real discount rate is lower than their Graph III.7

17; we end our projection in 2060 to maintain comparability with the AWG 2018 projections and we interpolate between the 5-year intervals reported. A final important note is that for internally available data of the authors’ home country, all calculations for round 2018 coincide if made with the assumptions of

Deboeck and Eckerfelt (

2020) and methodology analysed in this paper.

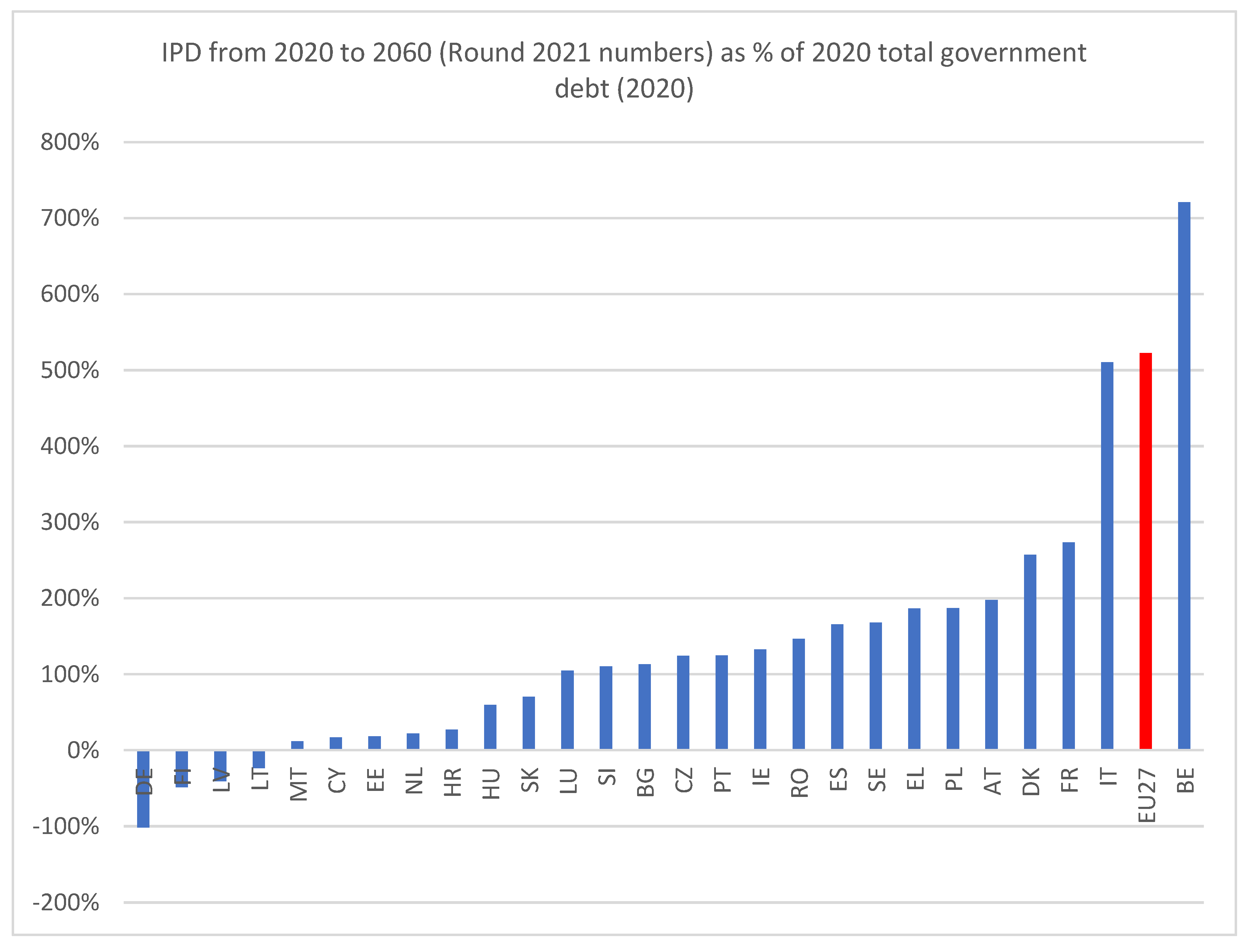

Possibly a more important comparison is that between IPD and outstanding bond debt. We used debt data from Eurostat for 2020 (

Eurostat 2021) at the end of the year. For most countries (17 out of 27) IPD using 2% discount is equal to or higher to debt. The necessity to service outstanding pension promises exceeding total outstanding debt implies, at the very least, that the simultaneous examination of debt servicing and pension deficits would be a fruitful exercise. Results are provided in

Figure 3 below.

To capture scale effects, IPD as a percentage of GDP is plotted against debt as percentage of GDP in a scatter diagram. Those countries where implicit debt exceeds explicit are below the diagonal. Results are provided in

Figure 4 below.

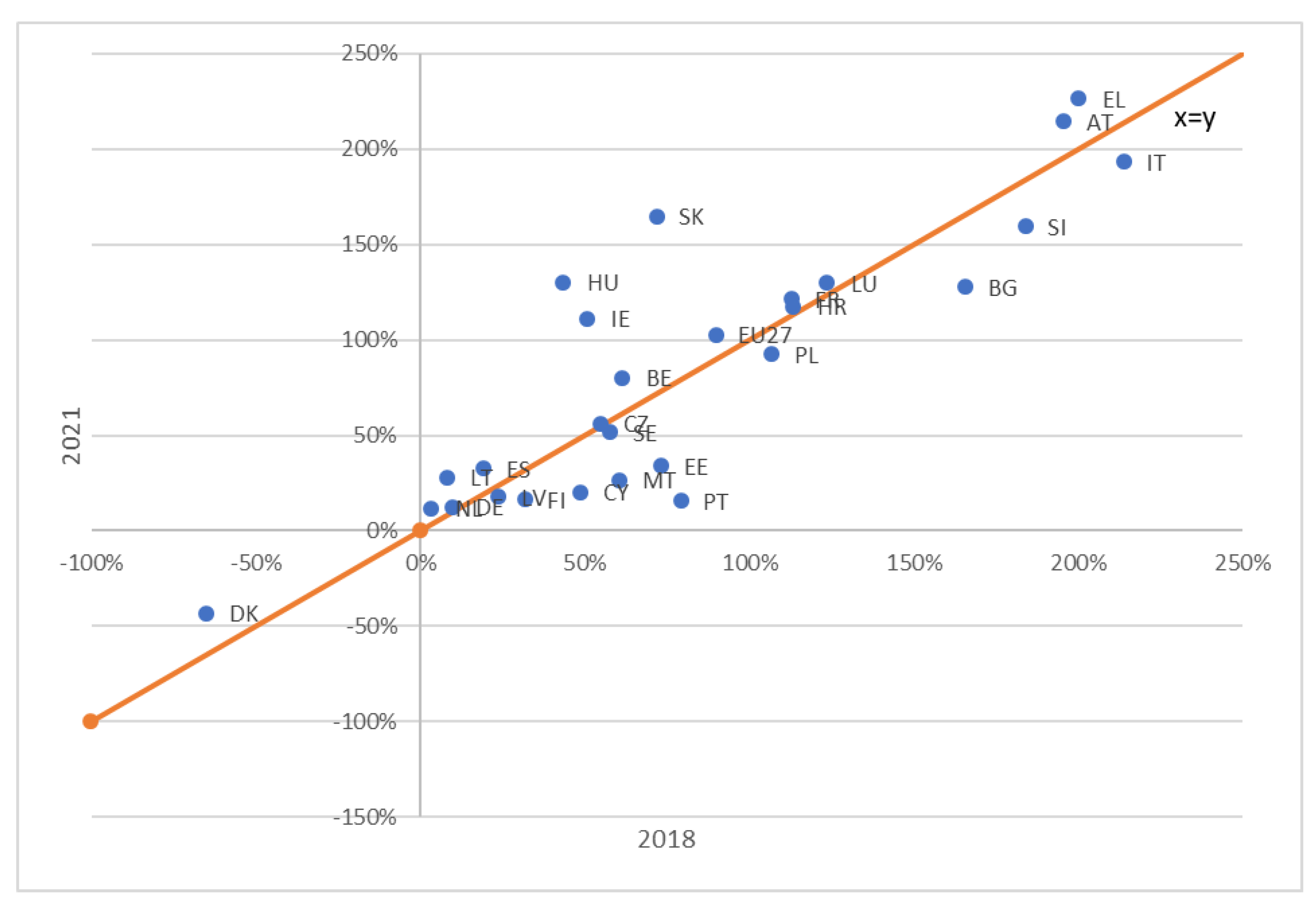

The final exercise is to track changes between IPD resulting from the last two published AWG exercises—2018 and 2021.

Figure 5 is a scatter diagram where IPD 2021 are plotted against IPD 2018. To aid comparisons to

Symeonidis et al. (

2020) only common years are compared—viz. years from 2020 to 2060; the years preceding the second benchmark date are not included. For the same reason, the GDP projection employed for

both cases is that of 2020. In that way, we hope to capture changes involving pension reforms and to abstract from differences outside the pension system or the projection period. The 45-degree line divides countries where IPF has risen or fallen as a percentage of 2019 if compared to projections made 3 years earlier. Differences could be due to pension reforms reducing future anticipated deficits. They could also be caused by differences in methodology between waves or due to differences to assumed projected behaviour of expenditure or revenue drivers. However, differences in assumptions between the two points are relatively minor, leaving differences to be accounted for by changes in pension systems. Some Member States, for example, have recently reversed previously legislated reforms. This is the case in Poland, Czechia, Croatia, and Slovakia. This explains the increase for the latter in 2021. In other cases, the impact of legislated reforms was suspended or postponed (e.g., in Spain) or new, temporary possibilities to retire early were created, as in Italy. On the other hand, the effect of a reduction of public pension spending as a share of GDP over the long term is projected in eleven Member States (EL, EE, PT, FR, LV, ES, HR, IT, DK, SE, and PL), as a result of implemented pension reforms can be experienced (Aging Report 2021). Finally, Hungary is one of the countries that would see spending increase by +1.8 pps in the final round, while Romania has enacted reforms in 2018, which explains why in both case the countries appear as outliers.

A definitive answer to whether IPDs are on a downward trend is important for policy. If it were concluded that IPDs are lower this could stand as a signal that addressing the impact of ageing on pensions is finally paying off. It could further act to justify the perceived change in problem solving in EU decisions towards green growth and the future of work. As

Holzmann (

1990) noted, IPDs can be a powerful shorthand instrument to gauge the efficacy of pension reform.

Our calculation of IPDs for 2018 can be used to address this problem in two ways:

Firstly, we can use the detailed comparisons of IPDs for 2021 and 2018 to test the hypothesis that unfunded expenditure across the EU is on a downward trend.

Table 6 shows that in 14 cases IPDs increased by a mean amount of 47 pp, while there was a decrease in 13 countries by 37 pp, which leaves an overall mean of a fall by 9 percentage points. In consequence, a one-tailed t-test does not reject the hypothesis that there was no change or an increase. This impression is confirmed by comparing medians of the two groups (which are not affected by extreme values).

Secondly, we may compare our own results with previous published results covering the same countries. The comparison in this case is necessarily more impressionistic as the coverage both in terms of countries and in terms of years differs; both demographic and macroeconomic drivers will also differ making the comparisons far less reliable.

Nevertheless, it is worth delving in four cases using EU data from the last decade—summarised in

Table 7. All four have as their starting point AWG projections of slightly different vintages and apply similar methodology to the one employed here. The exception is

Soto et al. (

2011), who uses older data and a lower discount rate, and applies ‘pension adjusted budget methodology’ and hence derives much lower estimates. In the three cases of studies published after 2011 average IPDs are considerably larger than computed in this study—by a large margin. This probably refers to a busier reform programme before 2018 and probably signifies a real change.

Both exercises lead to a tentative impression that IPDs are indeed falling, though at a decreasing rate. Even so, and even taking member states own interpretations of system revenue at face value, there remains a major challenge—equal to more than doubling the explicit debt burden of 2019. However, this is only an impression. To see how far pension reform has done its work, further work is necessary most notably by isolating the impact of changes in assumptions regarding drivers and hence netting out the impact of pension reforms.

The analysis could be taken further through a more direct discussion of debt sustainability analysis (DSA). One would, as a first step need to ensure that assumptions on GDP growth, interest rates and inflation are consistent. We could use the DSAs available for a subset of states, where available, to track the assumptions used. Key points of interest would be whether (a) GDP allows for a demographic effect pulling downwards and (b) whether tax elasticities assumed make an allowance for the added revenue necessary to cover future pension deficits. Comparing the relative time structure between pension deficits and debt servicing could indicate periods where production would need to cater both for heightened pension expenditure and for debt servicing. Other steps may be more ambitious, such as investigating the impact of inflation, which makes debt servicing easier but (through indexation) could make financing pensions harder. Similarly, wage growth or pandemic scarring could also be investigated. In that context, we should note that interest rate or GDP changes are in principle reversible, whereas a wave of early retirement would have a ratchet effect on future commitments.