The OFR Financial Stress Index

Abstract

1. Introduction

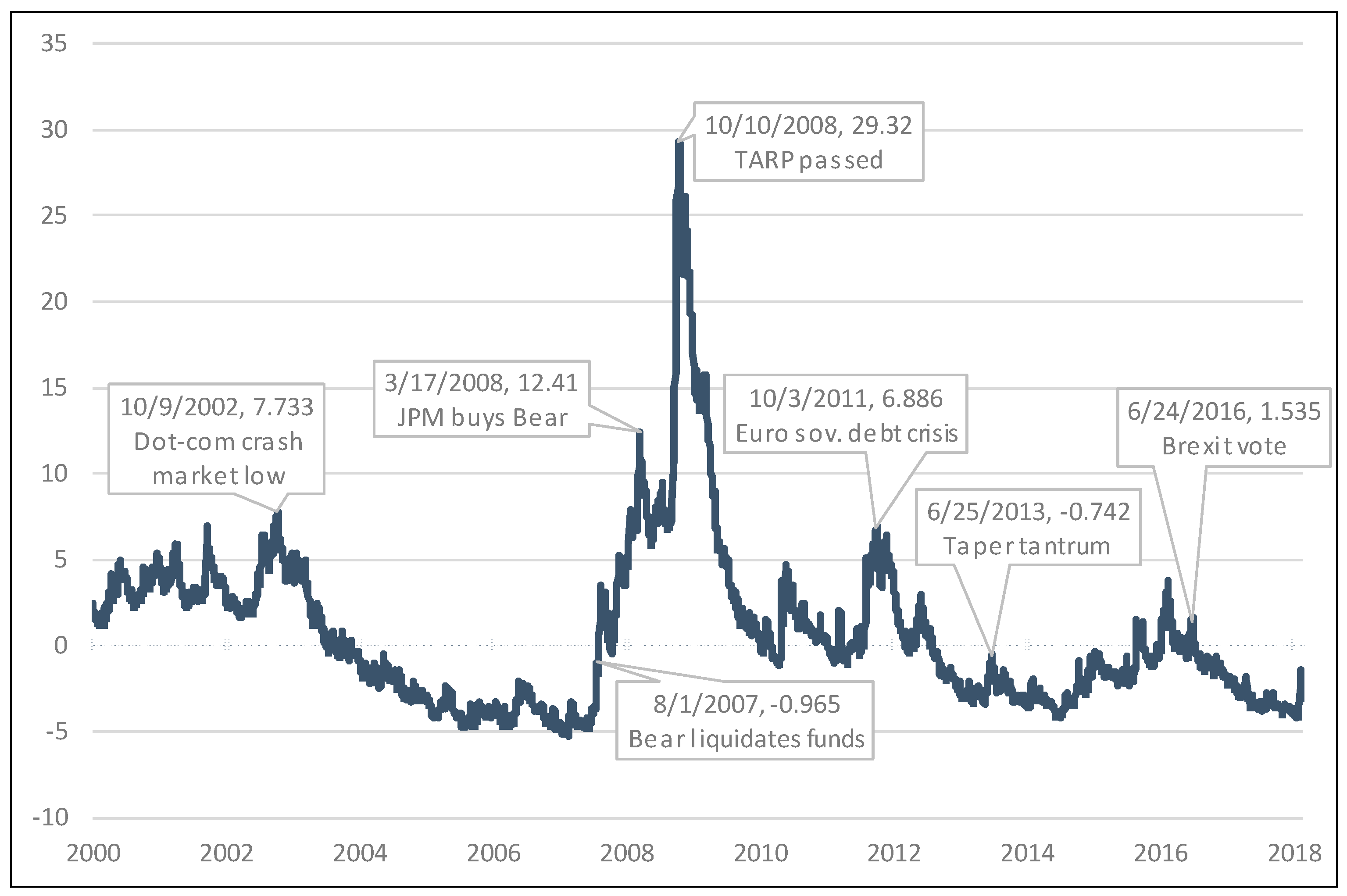

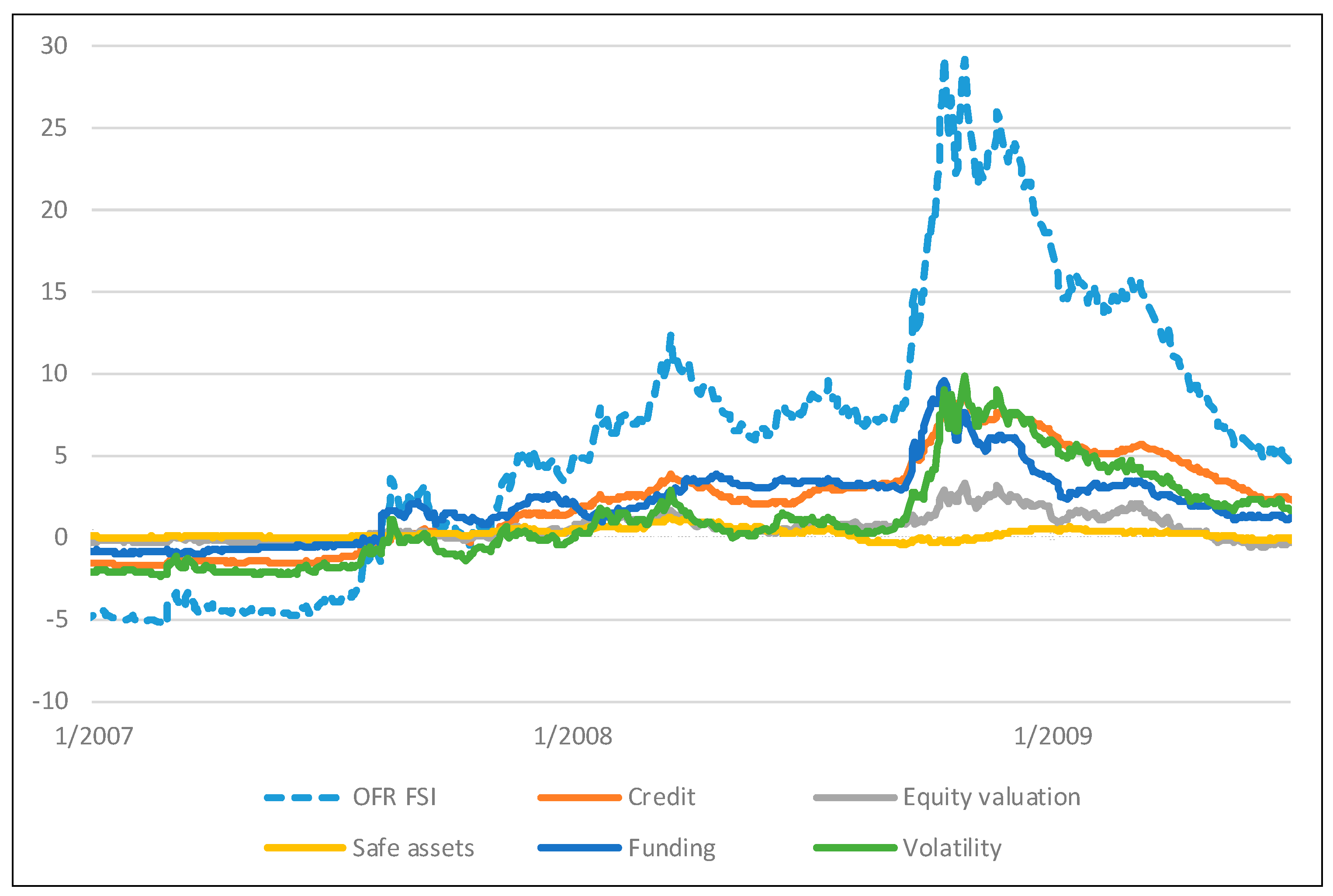

2. Systemic Financial Stress and Financial Stress Indexes

- Increased uncertainty about the fundamental value of assets or the behavior of investors. Volatility may rise when increased uncertainty causes investors to react more strongly to new information. Increased uncertainty can be measured by implied or realized volatility.

- Increased asymmetry of information. Asymmetric information can worsen during a stress event if variation in true quality of borrowers or assets increases, or if information is deemed less reliable. Information asymmetries can lead to problems of moral hazard and adverse selection, and to increased borrowing costs and decreased asset prices. Asymmetric information can be measured by increases in credit or funding spreads or decreases in risky asset valuations.

- Decreased willingness to hold risky assets. Investors that change their preferences or risk appetite may demand more compensation for holding risky assets. This change may lead to price decreases of risky assets and price increases of safe assets. The change can be measured by decreases in risky asset valuations or increases in safe asset valuations.

- Decreased willingness to hold illiquid assets. Investors may become reluctant to hold illiquid assets if demand for liquidity increases in anticipation of unexpected needs for cash. This change may be due to rising volatility, or a perceived deterioration in asset liquidity. The change can be measured by increases in funding spreads.

3. Construction and Interpretation of the OFR FSI

3.1. Indicator Selection

3.2. Indicator Aggregation

3.3. The Index and Its Interpretation

4. Use of the OFR FSI in Market Monitoring

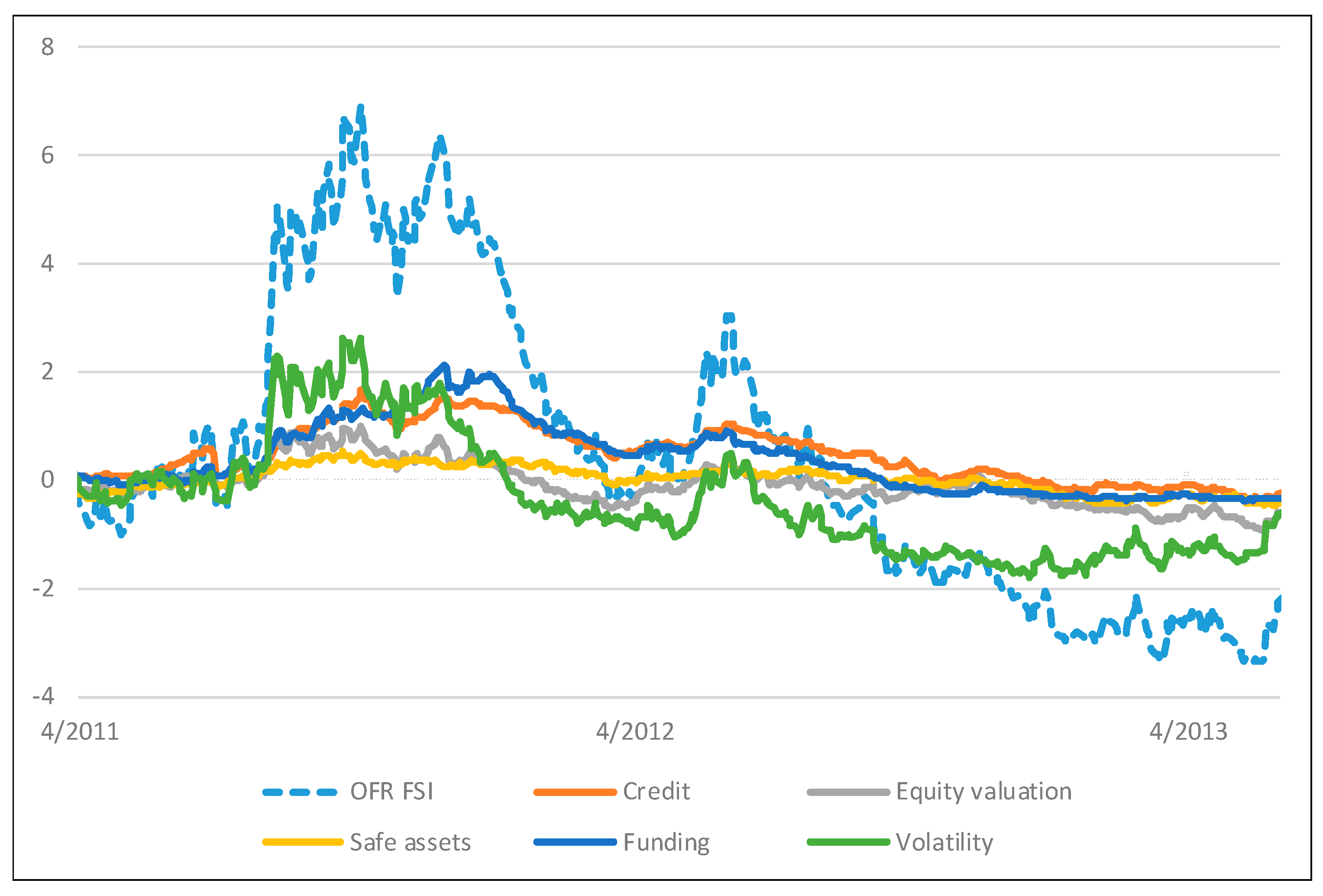

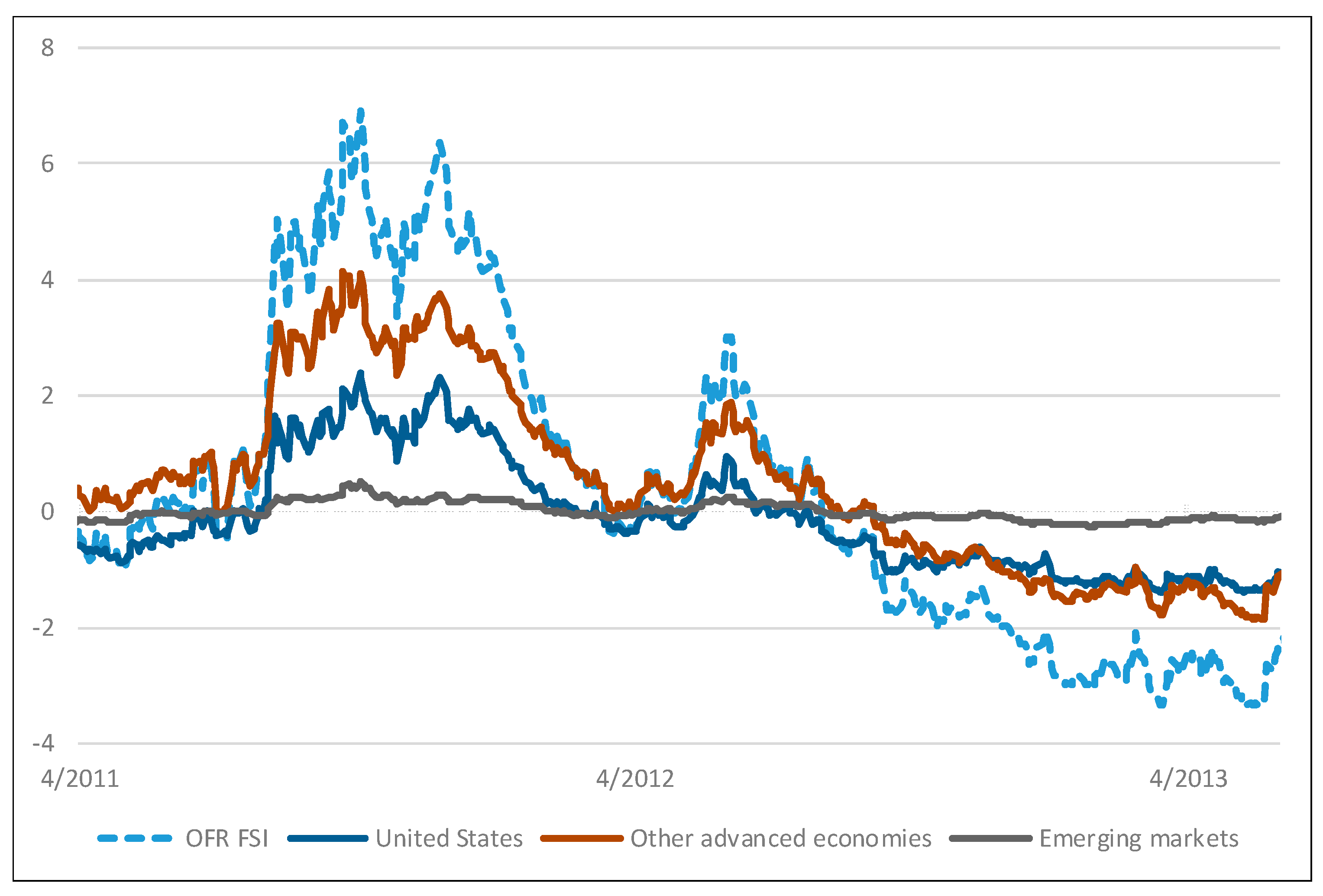

4.1. The European Sovereign Debt Crisis

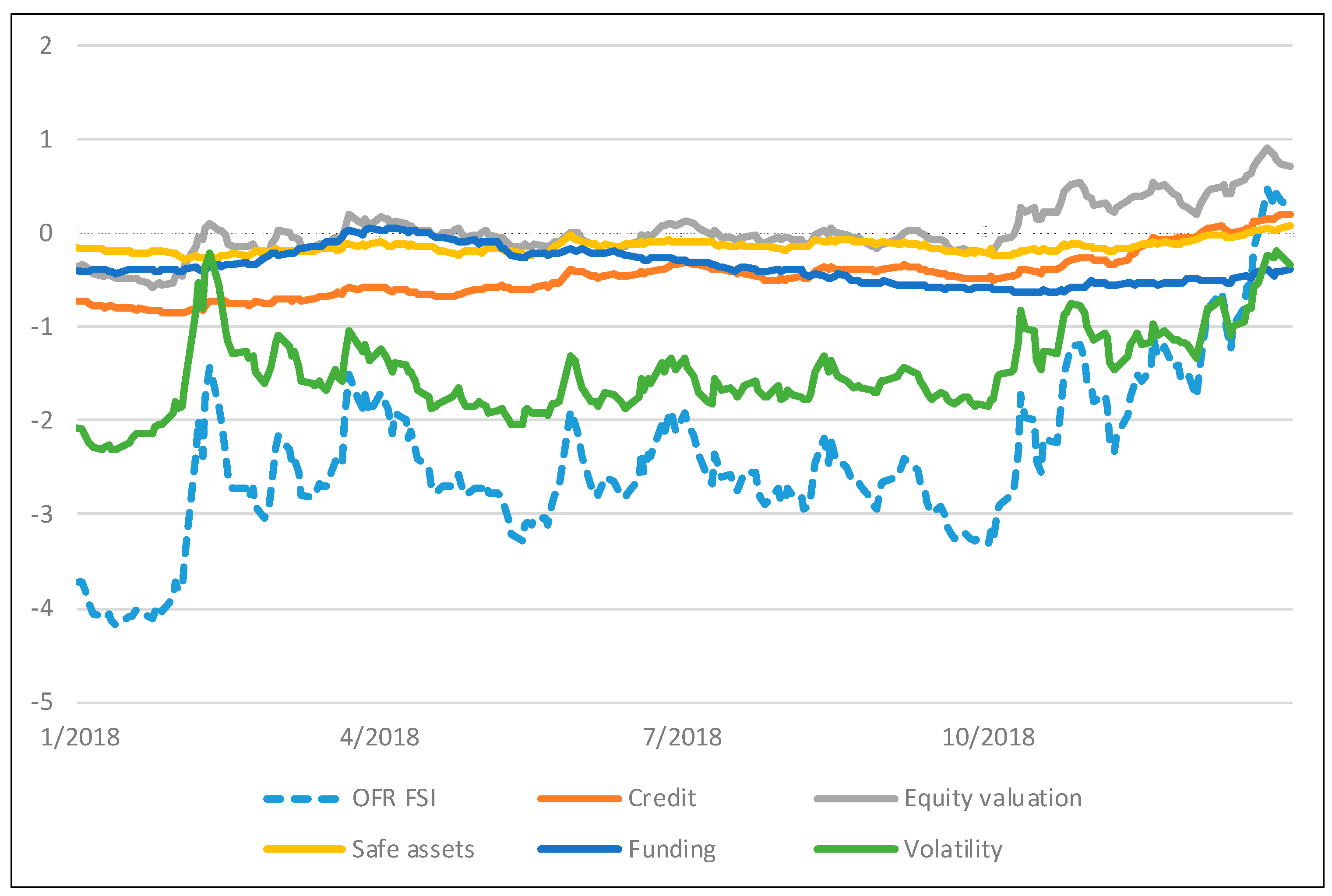

4.2. Financial Stress in 2018

5. Stress Identification and the Relationship of Stress to Economic Activity

5.1. Stress Identification Using the OFR FSI

5.2. The Relationship of Financial Stress to Real Economic Activity

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Indicator | Region(s) | Source | First Date in FSI | Note | Exp. Sign |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit | BaML US Corporate Master (IG) (OAS) | US | Haver | 1 January 2000 | L | Pos. |

| BaML US High Yield Corporate Master (HY) (OAS) | US | Haver | 1 January 2000 | L | Pos. | |

| BaML Euro Area Corp Bond Index (OAS) | AE | Haver | 1 January 2000 | L | Pos. | |

| BaML Euro Area High Yield Bond Index (OAS) | AE | Haver | 1 January 2000 | L | Pos. | |

| BaML Japan Corporate (OAS) | AE | Haver | 1 January 2000 | L | Pos. | |

| JPMorgan CEMBI Strip Spread | EM | Bloomberg | 1 January 2004 | L | Pos. | |

| JPMorgan EMBI Global Strip Spread | EM | Bloomberg | 1 April 2003 | L | Pos. | |

| Equity Valuation | MSCI Emerging Markets Index (P/B Ratio) | EM | Bloomberg | 1 January 2000 | LRMA | Neg. |

| MSCI Europe Index (P/B Ratio) | AE | Bloomberg | 1 February 2001 | LRMA | Neg. | |

| NIKKEI 225 Index (P/B Ratio) | AE | Bloomberg | 1 May 2002 | LRMA | Neg. | |

| S&P 500 Index (P/B Ratio) | US | Bloomberg | 1 January 2000 | LRMA | Neg. | |

| Funding | 2-Year EUR/USD Cross-Currency Swap Spread | US, AE | Bloomberg | 1 February 2001 | L | N/A |

| 2-Year US Swap Spread | US | Bloomberg | 1 January 2000 | L | N/A | |

| 2-Year USD/JPY Cross-Currency Swap Spread | US, AE | Bloomberg | 1 January 2000 | L | N/A | |

| 3-Month EURIBOR—EONIA | AE | Bloomberg, Haver | 1 March 2002 | L | Pos. | |

| 3-Month Japanese LIBOR—OIS | AE | Bloomberg | 1 April 2004 | L | Pos. | |

| 3-Month LIBOR—OIS | US | Bloomberg | 1 January 2004 | L | Pos. | |

| 3-Month TED Spread | US | Bloomberg | 1 January 2000 | L | Pos. | |

| Safe Assets | 10-Year US Treasury Note (yield) | US | Haver | 1 January 2000 | DMA | Neg. |

| 10-Year German Bond (yield) | AE | Bloomberg | 1 January 2000 | DMA | Neg. | |

| Gold/USD Real Spot Exchange Rate | US, AE, EM | Haver | 1 January 2000 | LRMA | Pos. | |

| Japanese Yen/USD Spot Exchange Rate | AE | Haver | 1 January 2000 | LRMA | N/A | |

| Swiss Franc/USD Spot Exchange Rate | AE | Haver | 1 January 2000 | LRMA | N/A | |

| US Dollar Index (DXY) | US | Bloomberg | 1 January 2000 | LRMA | N/A | |

| Volatility | CBOE S&P 500 Volatility Index (VIX) | US | Haver | 1 January 2000 | L | Pos. |

| Dow Jones EURO STOXX 50 Volatility Index (V2X) | AE | Bloomberg | 1 March 2002 | L | Pos. | |

| ICE Brent Crude Oil Futures (22-day realized vol.) | US, AE, EM | Bloomberg | 1 January 2000 | L | Pos. | |

| Implied Volatility on 6-Month EUR/USD Options | US, AE | Bloomberg | 1 February 2001 | L | Pos. | |

| Implied Volatility on 6-Month USD/JPY Options | US, AE | Bloomberg | 1 January 2000 | L | Pos. | |

| JPMorgan Emerging Market Volatility Index | AE | Bloomberg | 1 April 2003 | L | Pos. | |

| Merrill Lynch Euro Swaptions Volatility Estimate | AE | Bloomberg | 1 January 2000 | L | Pos. | |

| Merrill Lynch US Swaptions Volatility Estimate | US | Bloomberg | 1 January 2000 | L | Pos. | |

| NIKKEI Volatility Index | AE | Bloomberg | 1 February 2003 | L | Pos. | |

| Key | ||||||

| AE = Advanced economies ex-U.S., e.g., eurozone and Japan | HY = High yield | |||||

| BaML = Bank of America Merrill Lynch | IG = Investment grade | |||||

| CBOE = Chicago Board Options Exchange | JPY = Japanese yen | |||||

| CEMBI = Corporate Emerging Markets Bond Index | LIBOR = London Interbank Offered Rate | |||||

| EM = Emerging markets | MSCI = Morgan Stanley Capital International | |||||

| EMBI = Emerging Market Bond Index | OAS = Option-adjusted spread | |||||

| EONIA = Euro OverNight Index Average | OIS = Overnight indexed swap | |||||

| EUR = Euro | P/B Ratio = Price-to-book ratio (value-weighted) | |||||

| EURIBOR = Euro InterBank Offered Rate | USD = U.S. dollar | |||||

Appendix B

| Date | Intervention |

|---|---|

| 23 September 1998 | Federal Reserve coordinates purchase of LTCM by consortium of 12 firms |

| 11 September 2001 | Federal Reserve responds to liquidity shortages caused by the physical limitations of 9/11 |

| 10 August 2007 | Federal Reserve adds $38 billion in reserves and issues a statement reaffirming its commitment to provide liquidity |

| 17 August 2007 | Federal Reserve reduces primary credit spread by 50 basis points and allows 30-day term financing |

| 21 August 2007 | Federal Reserve reduced minimum fee rate for SOMA securities lending |

| 26 November 2007 | Federal Reserve eases terms on SOMA lending |

| 12 December 2007 | Federal Reserve announced creation of the TAF |

| 7 March 2008 | Federal Reserve announces it is expanding the size of the next two TAF auctions |

| 11 March 2008 | Federal Reserve announces the creation of the TSLF |

| 14 March 2008 | Federal Reserve lends to Bear Stearns |

| 16 March 2008 | Federal Reserve facilitates purchase of Bear Stearns by JPMC and creates PDCF |

| 2 May 2008 | Federal Reserve increases the size of TAF auctions |

| 13 July 2008 | Federal Reserve authorizes the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to lend to Fannie and Freddie should lending prove necessary |

| 30 July 2008 | Federal Reserve extends term lending on TAF to 84 days |

| 7 September 2008 | Treasury places Fannie and Freddie into conservatorship and provides liquidity backstops for GSEs |

| 15 September 2008 | Federal Reserve expands PDCF eligible assets and conducts two open market operations |

| 16 September 2008 | Federal Reserve extends line of credit to AIG |

| 19 September 2008 | Federal Reserve announces AMLF and Treasury guarantees MMMFs |

| 28 September 2008 | FDIC announces assistance for Wachovia merger and Federal Reserve increase size of TAF |

| 6 October 2008 | Federal Reserve further expands size of TAF |

| 7 October 2008 | Federal Reserve announces creation of the CPFF |

| 8 October 2008 | Federal Reserve decreases fees on SOMA lending |

| 14 October 2008 | Treasury announces $250 billion for preferred stock purchases and FDIC announces TLGP |

| 21 October 2008 | Federal Reserve announces the creation of the MMIFF |

| 23 November 2008 | Federal Reserve, Treasury, and FDIC agree to provide Citigroup a package of guarantees, liquidity access, and capital |

| 25 November 2008 | Federal Reserve announces the TALF |

| 30 December 2008 | Treasury announces the purchase of preferred stock in GMAC |

| 7 January 2009 | Federal Reserve expands set of institutions eligible to borrow under the MMIFF |

| 16 January 2009 | Treasury, FDIC, and Federal Reserve provide Bank of America with rescue package |

| 30 January 2009 | Federal Reserve liberalizes rules related to AMLF |

| 25 February 2009 | Federal Reserve, OCC, FDIC, and OTS announce details of the Capital Assistance Program |

| 23 March 2009 | Treasury announces the details of the public-partnership investment plan |

| 1 May 2009 | Federal Reserve announces the inclusion of the CMBS in the TALF |

| 7 May 2009 | Bank stress test results and capital-raising requirements for SCAP firms officially announced |

| 19 May 2009 | Federal Reserve further expands collateral eligible under the TALF |

| 2 May 2010 | Euro area member states and the IMF announce a three-year program for Greece, totaling €110 billion |

| 9 May 2010 | Euro area leaders announce that all the institutions of the euro area, including the ECB, commit to an overhaul of the European macroeconomic surveillance framework. Finance ministers announce the creation of the European Financial Stability Facility |

| 11 May 2010 | Federal Reserve agrees with foreign central banks to reestablish temporary dollar swap facilities |

| 29 October 2010 | European leaders reach an agreement on the need to set up a permanent crisis mechanism to safeguard the financial stability of the euro area as a whole (the European Stability Mechanism or ESM) |

| 28 November 2010 | European leaders and the IMF agree to grant an €85 billion assistance package to Ireland |

| 11 March 2011 | Euro area leaders agree to make the EFSF’s €440 billion lending capacity fully effective, and to allow the EFSF and ESM to intervene in the primary markets for sovereign debt, as an exception and only in the context of a financial assistance program |

| 17 May 2011 | Having received a request from Portugal, the European Council agrees to a financial assistance package totaling €78 billion over three years |

| 21 July 2011 | Euro area Heads of State or Government and EU institutions decide on a new package of measures to end the crisis and prevent contagion, including: a new program for Greece, and an agreement hat includes measures to enhance the flexibility of stabilization tolls by allowing the EFSF/ESM to act on the basis of a precautionary program, to intervene in secondary markets, and to finance the recapitalization of financial institutions through loans to governments, including non-program countries |

| 4 August 2011 | The ECB reactivates secondary market purchases and starts purchasing Italian and Spanish bonds in an attempt to ease market tensions |

| 6 September 2011 | The Swiss Central Bank announces its decision to cap the Swiss franc’s euro exchange rate, in an attempt to halt its appreciation |

| 27 October 2011 | European leaders agree on another comprehensive package of additional measures, focused on Greece and European firewalls. Leaders also agree to “optimize” the resources of the EFSF by introducing two leverage options, allowing the EFSF’s firepower to be multiplied |

| 30 November 2011 | The ECB, the Fed, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England, and the Swiss National Bank announce agreement to enhance their ability to provide liquidity. The agreement involves the extension of these arrangements to February 2013 and the possibility for each of the central banks to provide liquidity support in any of their currencies |

| 8 December 2011 | The ECB announces a package of measures to support the banking system, including the long-term refinancing operations |

| 21 February 2012 | European leaders agree on the terms for a second rescue program for Greece, with a marginally higher contribution from the private sector |

| 12 March 2012 | The Spanish government adopts a new comprehensive package of measures to strengthen the banking sector |

| 9 June 2012 | Spain becomes the first country to request financial assistance to recapitalize its banking sector, within the framework of a €100 billion program focused on the banking sector only |

| 25 June 2012 | Cyprus formally requests financial assistance form the EU and IMF |

| 30 April 2014 | the IMF approves a loan of $17.01 billion to Ukraine under a two-year Stand-by Arrangement in order to support Ukraine’s economic reform program |

| 15 January 2015 | The Swiss Central Bank abandons its currency cap against the euro as expectations for an ECB quantitative easing program put pressure on the Swiss franc |

| 11 March 2015 | The IMF approves a new loan of $17.5 billion to Ukraine to stabilize the economy and financial sector, bringing the total bailout package to $40 billion over four years |

| 14 August 2015 | Eurozone finance ministers agree to a third Greek bailout package worth €86 billion in exchange for tax hikes and spending cuts |

| 4 August 2016 | Bank of England launches four stimulating measures in response to Brexit |

References

- Acharya, Viral V., Lasse H. Pedersen, Thomas Philippon, and Matthew Richardson. 2017. Measuring Systemic Risk. Review of Financial Studies 30: 2–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, Tomáš, Soňa Benecká, and Jakub Matějů. 2018. Financial stress and its non-linear impact on CEE exchange rates. Journal of Financial Stability 36: 346–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian, Tobias, and Markus K. Brunnermeier. 2016. CoVaR. American Economic Review 106: 1705–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakis, George, and Athanasios P. Papadopoulos. 2019. Financial Stability, Monetary Stability and Growth: A PVAR Analysis. Open Economies Review 30: 157–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARRC. 2017. The ARRC Selects a Broad Repo Rate as its Preferred Alternative Reference Rate. ARRC: Alternative Reference Rates Committee. Press Release. June 22. Available online: https://www.newyorkfed.org/arrc/announcements.html (accessed on 23 October 2017).

- Arsov, Ivailo, Elie Canetti, Laura E. Kodres, and Srobona Mitra. 2013. Near-Coincident Indicators of Systemic Stress. IMF Working Paper No. 13/115, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, USA. May 17. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Jushan, and Serena Ng. 2008. Large Dimensional Factor Analysis. Foundations and Trends in Econometrics 3: 89–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisias, Dimitrios, Mark Flood, Andrew W. Lo, and Stavros Valavanis. 2012. A Survey of Systemic Risk Analytics. OFR Working Paper No. 12-01, Office of Financial Research, Washington, DC, USA. January 5. [Google Scholar]

- Brave, Scott A., and R. Butters. 2011. Monitoring Financial Stability: A Financial Conditions Approach. Economic Perspectives 35: 22–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bruegel. 2017. Euro Crisis Timeline. Available online: http://www.bruegel.org (accessed on 23 October 2017).

- Cardarelli, Roberto, Selim Elekdag, and Subir Lall. 2011. Financial Stress and Economic Contractions. Journal of Financial Stability 7: 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, Mark, Kurt Lewis, and William Nelson. 2012. Using Policy Intervention to Identify Financial Stress. Finance and Economics Discussion Series Working Paper 2012-02, Federal Reserve Board, Washington, DC, USA. January 10. [Google Scholar]

- Chicago Fed National Activity Index. 2016. Online Content, December 22. Available online: https://www.chicagofed.org/publications/cfnai/index (accessed on 23 October 2017).

- Dattels, Peter, Rebecca McCaughrin, Ken Miyajima, and Jaume Puig. 2010. Can You Map Global Financial Stability? IMF Working Paper No. 2010/145, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, USA. June. [Google Scholar]

- Duprey, Thibaut, and Benjamin Klaus. 2017. How to predict financial stress? An assessment of Markov switching models. ECB Working Paper Series No. 2057, European Central Bank, Frankfurt, Germany. May. [Google Scholar]

- Duprey, Thibaut, Benjamin Klaus, and Tuomas Peltonen. 2017. Dating systemic financial stress episodes in EU countries. Journal of Financial Stability 32: 30–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, Marianna B. 2010. Detecting and Interpreting Financial Stress in the Euro Area. ECB Working Paper Series No. 1214, European Central Bank, Frankfurt, Germany. June. [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi, Marianna B. 2011. Up for Count? Central Bank Words and Financial Stress. Sveriges Riksbank Working Paper Series No. 252, Sveriges Riksbank, Stockholm, Sweden. April. [Google Scholar]

- Hakkio, Craig S., and William R. Keeton. 2009. Financial stress: What is it, how can it be measured, and why does it matter? Economic Review 94: 5–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzius, Jan, Peter Hooper, Frederic S. Mishkin, Kermit L. Schoenholtz, and Mark W. Watson. 2010. Financial Conditions Indexes: A Fresh Look after the Financial Crisis. NBER Working Paper 16150, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, USA. July. [Google Scholar]

- Hollo, Daniel, Manfred Kremer, and Marco Lo Duca. 2012. CISS—A Composite Indicator of Systemic Stress in the Financial System. ECB Working Paper Series No. 1426, European Central Bank, Frankfurt, Germany. March. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Xin, Hao Zhou, and Haibin Zhu. 2012. Assessing the systemic risk of a heterogeneous portfolio of banks during the recent financial crisis. Journal of Financial Stability 8: 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illing, Mark, and Ying Liu. 2006. Measuring Financial Stress in a Developed Country: An Application to Canada. Journal of Financial Stability 2: 243–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliesen, Kevin L., and Douglas C. Smith. 2010. Measuring Financial Market Stress. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis National Economic Trends, January 15. [Google Scholar]

- Kliesen, Kevin L., Michael T. Owyang, and E. Katarina Vermann. 2012. Disentangling Diverse Measures: A Survey of Financial Stress Indexes. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 94: 369–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Duca, Marco, and Tuomas A. Peltonen. 2011. Macro-Financial Vulnerabilities and Future Financial Stress: Assessing Systemic Risks and Predicting Systemic Events. ECB Working Paper Series No. 1311, European Central Bank, Frankfurt, Germany. March. [Google Scholar]

- Louzis, Dimitrios P., and Angelos T. Vouldis. 2013. A Financial Systemic Stress Index for Greece. ECB Working Paper No 1563, European Central Bank, Frankfurt, Germany. July. [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, Daniel. 1977. Quantitative Methods for Analyzing Travel Behaviour of Individuals: Some Recent Developments. Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper No. 474. New Haven: Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics at Yale University, November 22. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, William R., and Roberto Perli. 2007. Selected Indicators of Financial Stability. Risk Management and Systemic Risk 4: 343–72. [Google Scholar]

- OFR Financial Markets Monitor. 2017. The Volatility Paradox: Tranquil Markets May Harbor Hidden Risks. Second Quarter 2017. August 17. Available online: https://www.financialresearch.gov/financial-markets-monitor/2017/08/17/the-volatility-paradox/ (accessed on 23 October 2017).

- Rosenberg, Michael. 2009. Financial Conditions Watch: Global Financial Market Trends and Policy. Bloomberg LLP, September 11. [Google Scholar]

- Sandahl, Johannes F., Mia Holmfeldt, Anders Rydén, and Maria Strömqvist. 2011. An Index of Financial Stress for Sweden. Sveriges Riksbank Economic Review 2: 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, James H., and Mark Watson. 2002. Macroeconomic Forecasting Using Diffusion Indexes. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 20: 147–62. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, James H., and Mark Watson. 2006. Forecasting with Many Predictors. In Handbook of Economic Forecasting. Edited by Graham Elliot, Clive Granger and Allan Timmermann. Amsterdam: Elsevier, chp. 6. pp. 515–54. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, James H., and Mark Watson. 2010. Dynamic Factor Models. In Oxford Handbook of Economic Forecasting. Edited by Michael Clements and David Hendry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Toda, Hiro Y., and Taku Yamamoto. 1995. Statistical inference in vector autoregressions with possibly integrated processes. Journal of Econometrics 66: 225–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasicek, Borek, Diana Zigraiova, Marco Hoeberichts, Robert Vermeulen, Katerina Smidkova, and Jakob de Haan. 2017. Leading indicators of financial stress: New evidence. Journal of Financial Stability 28: 240–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The OFR Financial Stress Index (OFR FSI) is published after every U.S. trading day by the Office of Financial Research. It is available online at https://www.financialresearch.gov/financial-stress-index/. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | This proceeds as follows: initialize the algorithm with a loading vector and compute an initial factor . Subsequent iterates are computed using and . We proceed for 200 iterations. We then repeat the analysis 15 times, initializing the vector in different ways, including taking the first principal component of the largest subset of balanced panel data, taking the first principal component using a pseudo-correlation matrix constructed by the pairwise correlations using each pair’s overlapping sample, and sampling from a random normal vector. We then select the iteration with the smallest sum of squared errors. |

| 4 | Descriptions of the indicator categories are in Table 1. Additional information about the indicators in the index, including definitions of the abbreviations used in Table 2, is available in Appendix A. |

| 5 | The 10-year Treasury note yield is transformed to be relative to its 250-trading day moving average. See Appendix A. |

| 6 | See for example, (OFR Financial Markets Monitor 2017) “The Volatility Paradox: Tranquil Markets May Harbor Hidden Risks.” |

| 7 | McFadden’s pseudo R-squared is equal to one minus the ratio of the log-likelihood of the model containing the OFR FSI to that of the model with just a constant. Higher values are thus associated with more variation in StressEvent being explained by the OFR FSI. McFadden (1977) suggests that values above 0.2 indicate “excellent” model fit. |

| Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| Credit | Contains measures of credit spreads, which represent the difference in borrowing costs for firms of different creditworthiness. In times of stress, credit spreads may widen when default risk increases or credit market functioning is disrupted. Wider spreads may indicate that investors are less willing to hold debt, increasing costs for borrowers to get funding. |

| Equity valuation | Contains stock valuations from several stock market indexes, which reflect investor confidence and risk appetite. In times of stress, stock values may fall if investors become less willing to hold risky assets. |

| Funding | Contains measures related to how easily financial institutions can fund their activities. In times of stress, funding markets can freeze if participants perceive greater counterparty credit risk or liquidity risk. |

| Safe assets | Contains valuation measures of assets that are considered stores of value or have stable and predictable cash flows. In times of stress, higher valuations of safe assets may indicate that investors are migrating from risky or illiquid assets into safer holdings. |

| Volatility | Contains measures of implied and realized volatility from equity, credit, currency, and commodity markets. In times of stress, rising uncertainty about asset values or investor behavior can lead to higher volatility. |

| Indicator Category | Indicator | Coef. | Data | Wgt. | Data * | Contr. | Subtotal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit | BaML US Corporate Master (IG) (OAS) | 0.241 | 0.016 | 0.241 | 0.016 | 0.004 | |

| BaML US High Yield Corporate Master (HY) (OAS) | 0.244 | −0.114 | 0.244 | −0.114 | −0.028 | ||

| BaML Euro Area Corp Bond Index (OAS) | 0.160 | 0.761 | 0.160 | 0.761 | 0.122 | ||

| BaML Euro Area High Yield Bond Index (OAS) | 0.230 | −0.346 | 0.230 | −0.346 | −0.080 | ||

| BaML Japan Corporate (OAS) | 0.174 | 0.697 | 0.174 | 0.697 | 0.122 | ||

| JPMorgan CEMBI Strip Spread | 0.209 | 0.248 | 0.209 | 0.248 | 0.052 | ||

| JPMorgan EMBI Global Strip Spread | 0.131 | 0.100 | 0.131 | 0.100 | 0.013 | 0.205 | |

| Equity Valuation | MSCI Emerging Markets Index (P/B Ratio) | −0.141 | −0.618 | 0.141 | 0.618 | 0.087 | |

| MSCI Europe Index (P/B Ratio) | −0.190 | −0.855 | 0.190 | 0.855 | 0.162 | ||

| NIKKEI 225 Index (P/B Ratio) | −0.172 | −1.102 | 0.172 | 1.102 | 0.190 | ||

| S&P 500 Index (P/B Ratio) | −0.197 | −1.365 | 0.197 | 1.365 | 0.269 | 0.708 | |

| Funding | 2-Year EUR/USD Cross-Currency Swap Spread | −0.095 | 0.244 | 0.095 | −0.244 | −0.023 | |

| 2-Year US Swap Spread | 0.174 | −0.960 | 0.174 | −0.960 | −0.167 | ||

| 2-Year USD/JPY Cross-Currency Swap Spread | −0.012 | −0.484 | 0.012 | 0.484 | 0.006 | ||

| 3-Month EURIBOR—EONIA | 0.206 | −0.579 | 0.206 | −0.579 | −0.120 | ||

| 3-Month Japanese LIBOR—OIS | 0.187 | −0.941 | 0.187 | −0.941 | −0.176 | ||

| 3-Month LIBOR—OIS | 0.192 | 0.407 | 0.192 | 0.407 | 0.078 | ||

| 3-Month TED Spread | 0.173 | 0.036 | 0.173 | 0.036 | 0.006 | −0.395 | |

| Safe Assets | 10-Year US Treasury Note (yield) | −0.105 | −0.301 | 0.105 | 0.301 | 0.032 | |

| 10-Year German Bond (yield) | −0.095 | −0.190 | 0.095 | 0.190 | 0.018 | ||

| Gold/USD Real Spot Exchange Rate | 0.033 | −0.048 | 0.033 | −0.048 | −0.002 | ||

| Japanese Yen/USD Spot Exchange Rate | −0.109 | −0.023 | 0.109 | 0.023 | 0.002 | ||

| Swiss Franc/USD Spot Exchange Rate | −0.008 | 0.191 | 0.008 | −0.191 | −0.002 | ||

| US Dollar Index (DXY) | 0.050 | 0.547 | 0.050 | 0.547 | 0.027 | 0.076 | |

| Volatility | CBOE S&P 500 Volatility Index (VIX) | 0.254 | 0.790 | 0.254 | 0.790 | 0.201 | |

| Dow Jones EURO STOXX 50 Volatility Index (V2X) | 0.209 | −0.029 | 0.209 | −0.029 | −0.006 | ||

| ICE Brent Crude Oil Futures (22-day realized volatility) | 0.176 | 1.518 | 0.176 | 1.518 | 0.267 | ||

| Implied Volatility on 6-Month EUR/USD Options | 0.199 | −1.052 | 0.199 | −1.052 | −0.210 | ||

| Implied Volatility on 6-Month USD/JPY Options | 0.161 | −0.872 | 0.161 | −0.872 | −0.140 | ||

| JPMorgan Emerging Market Volatility Index | 0.216 | −0.169 | 0.216 | −0.169 | −0.037 | ||

| Merrill Lynch Euro Swaptions Volatility Estimate | 0.198 | −1.696 | 0.198 | −1.696 | −0.336 | ||

| Merrill Lynch US Swaptions Volatility Estimate | 0.185 | −0.922 | 0.185 | −0.922 | −0.170 | ||

| NIKKEI Volatility Index | 0.208 | 0.507 | 0.208 | 0.507 | 0.105 | −0.326 | |

| OFR FSI | 0.268 | ||||||

| Variable | Mean | Std | 25% | 50% | 75% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OFR FSI | 0.76 | 4.68 | −2.64 | −0.22 | 2.95 |

| Count = 0 | Count = 1 | ||||

| StressEvent | 3364 | 1081 |

| Dependent Variable: StressEvent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coef. | SE | t-stat | p-Value |

| Constant | −1.521 | 0.044 | −34.620 | <0.00001 |

| OFR FSI | 0.271 | 0.010 | 24.270 | <0.00001 |

| Odds ratio | 1.31 | |||

| McF-R2 | 0.19 | |||

| AUC | 0.76 | |||

| Variable | Mean | Std | 25% | 50% | 75% |

| OFR FSI | 0.78 | 4.61 | −2.49 | −0.22 | 3.02 |

| CFNAI | −0.29 | 0.85 | −0.51 | −0.16 | 0.19 |

| Dependent Variable: CFNAI | |||

| Variable | Coef. | SE | t-stat |

| OFR FSI (t−1) | −0.036 | 0.023 | −1.521 |

| OFR FSI (t−2) | −0.071 | 0.035 | −2.043 |

| Does the OFR FSI help predict CFNAI? | |||

| Null hypothesis: OFR FSI does not Granger cause the CFNAI | |||

| F-stat | 13.30 | ||

| p-value | <0.0001 | ||

| Dependent Variable: OFR FSI | |||

| Variable | Coef. | SE | t-stat |

| CFNAI (t−1) | −0.392 | 0.212 | −1.849 |

| CFNAI (t−2) | 0.064 | 0.200 | 0.320 |

| Does the CFNAI help predict OFR FSI? | |||

| Null hypothesis: CFNAI does not Granger cause the OFR FSI | |||

| F-stat | 1.71 | ||

| p-value | 0.1835 | ||

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monin, P.J. The OFR Financial Stress Index. Risks 2019, 7, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks7010025

Monin PJ. The OFR Financial Stress Index. Risks. 2019; 7(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks7010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonin, Phillip J. 2019. "The OFR Financial Stress Index" Risks 7, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks7010025

APA StyleMonin, P. J. (2019). The OFR Financial Stress Index. Risks, 7(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks7010025