How Does Distress Acquisition Incentivized by Government Purchases of Distressed Loans Affect Bank Default Risk?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Literature

3. The Framework and Assumptions

4. The Model

4.1. The Acquirer Bank

4.2. The Acquired Bank

4.3. The Consolidated Bank

4.4. Incentivized Acquisition

5. Solutions and Results

6. Numerical Exercises

6.1. Baselines

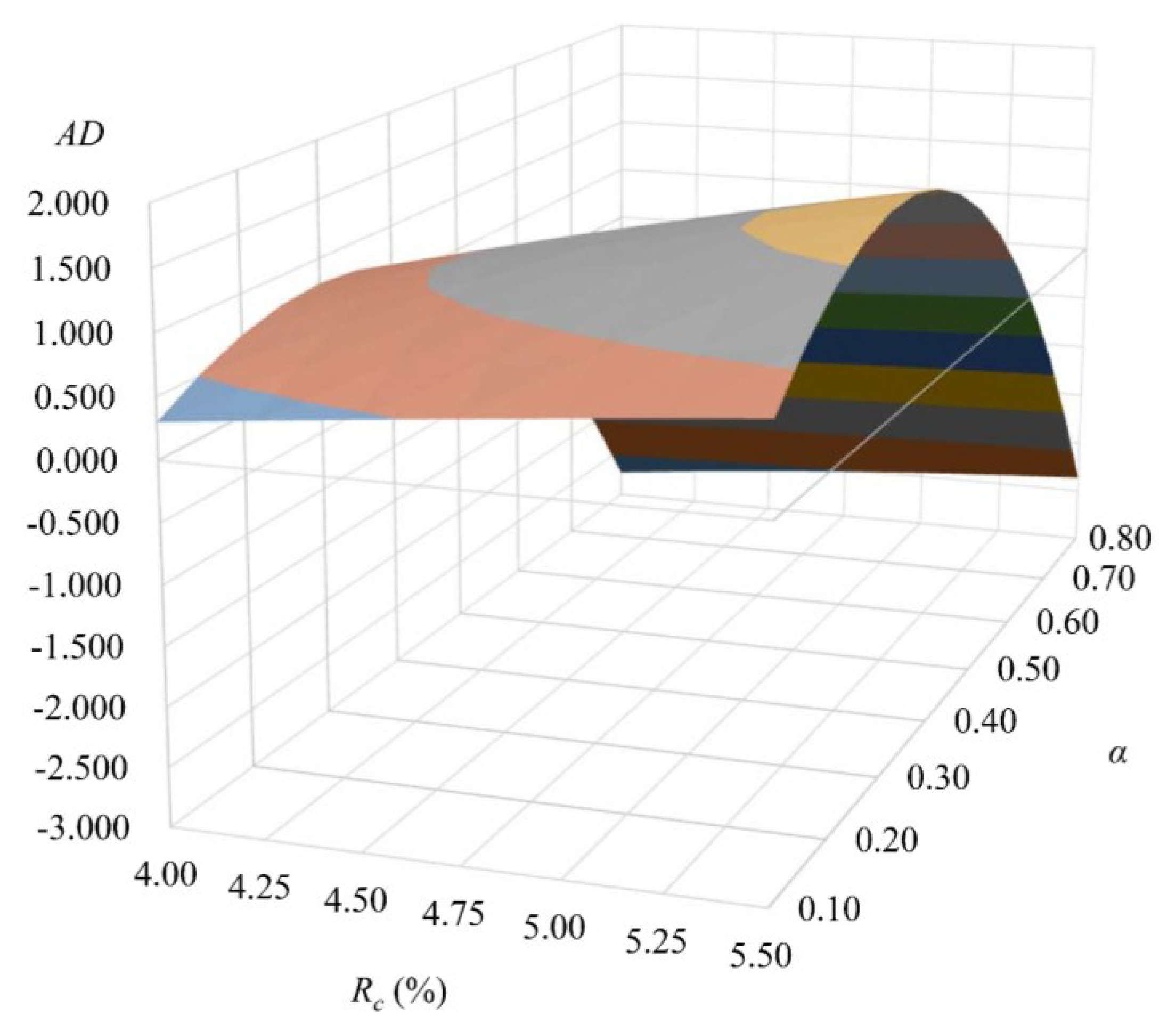

6.2. Effect of the Government’s Purchases of Distressed Loans on Default Risk

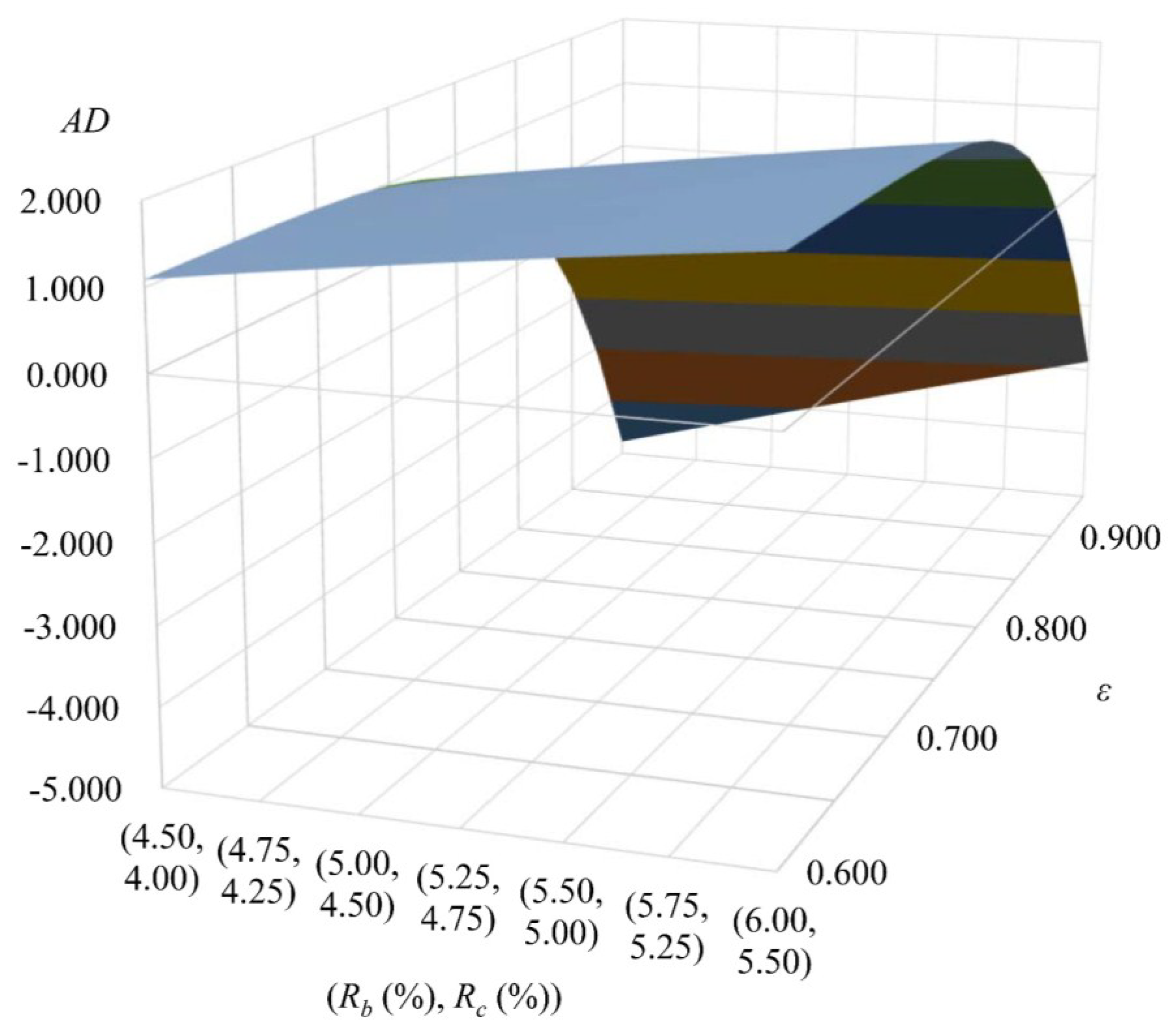

6.3. Effect of the Acquired Bank’s Knock-Out Value on Default Risk

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bayazitova, Dinara, and Anil Shivdasani. 2011. Assessing TARP. Review of Financial Studies 25: 377–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebchuk, Lucian Arye. 2008. A Plan for Addressing the Financial Crisis. Economics and Business Discussion Paper Series, Paper 620. Cambridge: Harvard Law School. Available online: http://lsr.nellco.org/harvard_olin/620 (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Beccalli, Elena, and Pascal Frantz. 2013. The determinants of mergers and acquisitions in banking. Journal of Financial Services Research 43: 265–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Allen N., Rebecca S. Demsetz, and Philip E. Strahan. 1999. The consolidation of the financial services industry: Causes, consequences, and implications for the future. Journal of Banking & Finance 23: 135–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitenfellner, Bastian, and Niklas Wagner. 2010. Government intervention in response to the subprime financial crisis: The good into the pot, the bad into the crop. International Review of Financial Analysis 19: 289–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockman, Paul, and Harry J. Turtle. 2003. A barrier option framework for corporate security valuation. Journal of Financial Economics 67: 511–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebenoyan, A. Sinan, and Philip E. Strahan. 2004. Risk management, capital structure and lending at banks. Journal of Banking & Finance 28: 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouhy, Michel, and Dan Galai. 1991. A contingent claim analysis of a regulated depository institution. Journal of Banking & Finance 15: 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsas, Ralf. 2004. Preemptive Distress Resolution through Bank Mergers. Working Paper. Frankfurt: Goethe University Frankfurt. Available online: http://publikationen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/opus4/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/3705/file/454.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Emmons, William R., R. Alton Gilbert, and Timothy J. Yeager. 2004. Reducing the risk at community banks: Is it size or geographic diversification that matters? Journal of Financial Services Research 25: 259–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Episcopos, Athanasios. 2008. Bank capital regulation in a barrier option framework. Journal of Banking & Finance 32: 1677–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorton, Gary, and Lixin Huang. 2004. Liquidity, efficiency, and bank bailouts. American Economic Review 94: 455–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoggarth, Glenn, Jack Reidhill, and Peter Sinclair. 2003. Resolution of banking crises: A review. In Financial Stability Review. London: Bank of England, vol. 15, pp. 109–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi, Takeo, and Anil. K. Kashyap. 2010. Will the U.S. bank recapitalization succeed? Eight lessons from Japan. Journal of Financial Economics 97: 398–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Joseph P., William W. Lang, Loretta J. Mester, and Choon-Geol Moon. 1999. The dollars and sense of bank consolidation. Journal of Banking & Finance 23: 291–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, Anil K., Raghuram G. Rajan, and Jeremy C. Stein. 2002. Banks as liquidity providers: An explanation for the coexistence of lending and deposit-taking. Journal of Finance 57: 33–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasman, Adnan, Gokce Tunc, Gulin Vardar, and Berna Okan. 2010. Consolidation and commercial bank net interest margins: Evidence from the old and new European Union members and candidate countries. Economic Modelling 27: 648–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maudos, Joaquín, and Juan Fernández de Guevara. 2004. Factors explaining the interest margin in the banking sectors of the European Union. Journal of Banking & Finance 28: 2259–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, Robert C. 1973. Theory of rational option pricing. Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 4: 141–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, Robert C. 1974. On the pricing of corporate debt: The risk structure of interest rates. Journal of Finance 29: 449–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, Helena M., and David H. Pyle. 1994. Liquidation costs and risk-based bank capital. Journal of Banking & Finance 18: 113–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, Robert S. 1996. Credit derivatives: New financial instruments for controlling credit risk. Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City 81: 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sahut, Jean-Michel, and Mehdi Mili. 2011. Banking distress in MENA countries and the role of mergers as a strategic policy to resolve distress. Economic Modelling 28: 138–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vallascas, Francesco, and Jens Hagendorff. 2011. The impact of European bank mergers on bidder default risk. Journal of Banking & Finance 35: 902–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanHoose, David. 2007. Theories of bank behavior under capital regulation. Journal of Banking & Finance 31: 3680–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Barry. 2007. Factors determining net interest margins in Australia: Domestic and foreign banks. Financial Markets, Institutions & Instruments 16: 145–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Linus. 2010. The put problem with buying toxic assets. Applied Financial Economics 20: 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Kit Pong. 1997. On the determinants of bank interest margins under credit and interest rate risks. Journal of Banking & Finance 21: 251–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Alternatively, Beccalli and Frantz (2013) point out that a higher likelihood of becoming an acquirer exists for larger banks with a history of high growth, greater cost X-efficiency, and low capitalization. In contrast, banks are more likely to be targets if they have lower free cash flows, are less efficient, are illiquid, and are under-capitalized. |

| 2 | This capital constraint will be binding as long as is sufficiently higher than (Wong 1997). |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | As pointed out by Breitenfellner and Wagner (2010), the possible government supports generally include government guaranteed debt-issuance programs, direct equity injections, and purchases of distressed assets by the government. The design of a government assistance program largely depends on its targets, such as financial stabilization, taxpayer protection, or separation between good and bad management performance. This paper focuses on purchases of distressed assets by the government as an acquisition incentive. We argue that an alternative assistance program used as an incentive for acquisition may result in different outcomes. |

| 6 | Funds will be collected in fines, penalties, and forfeitures from the consolidated bank if violations related to the Bank Secrecy Act and U.S. sanctions programs require this. These requirements are significant tools that aid the financial authorities in detecting, disruption and inhibiting corruption. We remain silent on the issue in our model. |

| 7 | Equation (11) is an alternative decision used in our model for the strong acquirer bank incentivized to participate in the government’s assistance program. Hoshi and Kashyap (2010) argue that a bank may refuse government assistance if a bailout program generates an adverse signal that the bank is expected to have high future losses. We are silent on this issue. |

| 8 | Neal (1996) argues that banks are exposed to the risk that borrowers will default on their loans and the credit risk faced by banks is relatively high. This is understood because banks tend to concentrate their loans geographically or in particular industries, which limits their ability to diversify credit risks across borrowers. |

| 9 | Nevertheless, our results generally apply to other cases of as well. |

| 10 | The linear slope of and are and . The margins at and , for example, are and , respectively. |

| Asset | Liability and Equity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquirer bank: | |||

| Loan | Deposit | 1 | |

| Liquid asset | Equity | ||

| Acquired bank: | |||

| Loan | Deposit | ||

| Liquid asset | Equity | ||

| Consolidated bank: | |||

| Loan | Deposit | ||

| Loan purchased by | Equity | ||

| government | |||

| Liquid asset |

| (4.50, 200) | (4.75, 197) | (5.00, 194) | (5.25, 191) | (5.50, 188) | (5.75, 185) | (6.00, 182) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.10~0.15 | - | 2.1448 | 2.0753 | 1.9664 | 1.8867 | 1.8212 | - |

| 0.15~0.20 | - | 1.7013 | 1.5987 | 1.5641 | 1.4625 | 1.4367 | - |

| 0.20~0.25 | - | 1.2744 | 1.2182 | 1.1768 | 1.1012 | 1.0663 | - |

| 0.25~0.30 | - | 0.9294 | 0.8779 | 0.8208 | 0.7816 | 0.7356 | - |

| 0.30~0.35 | - | 0.5989 | 0.5618 | 0.5251 | 0.4972 | 0.4611 | - |

| 0.35~0.40 | - | 0.3187 | 0.2826 | 0.2623 | 0.2337 | 0.2120 | - |

| 0.10~0.15 | - | −0.0916 | −0.0803 | −0.0684 | −0.0592 | −0.0512 | - |

| 0.15~0.20 | - | −0.0726 | −0.0619 | −0.0544 | −0.0459 | −0.0404 | - |

| 0.20~0.25 | - | −0.0544 | −0.0471 | −0.0410 | −0.0346 | −0.0300 | - |

| 0.25~0.30 | - | −0.0397 | −0.0340 | −0.0286 | −0.0245 | −0.0207 | - |

| 0.30~0.35 | - | −0.0256 | −0.0217 | −0.0183 | −0.0156 | −0.0130 | - |

| 0.35~0.40 | - | −0.0136 | −0.0109 | −0.0109 | −0.0073 | −0.0060 | - |

| (4.50, 200) | (4.75, 197) | (5.00, 194) | (5.25, 191) | (5.50, 188) | (5.75, 185) | (6.00, 182) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.600~0.625 | - | 0.0036 | 0.0036 | 0.0036 | 0.0036 | 0.0036 | - |

| 0.625~0.650 | - | 0.0101 | 0.0101 | 0.0101 | 0.0101 | 0.0101 | - |

| 0.650~0.675 | - | 0.0254 | 0.0255 | 0.0254 | 0.0255 | 0.0254 | - |

| 0.675~0.700 | - | 0.0585 | 0.0584 | 0.0584 | 0.0584 | 0.0584 | - |

| 0.700~0.725 | - | 0.1228 | 0.1229 | 0.1229 | 0.1228 | 0.1229 | - |

| 0.725~0.750 | - | 0.2389 | 0.2388 | 0.2389 | 0.2389 | 0.2389 | - |

| 0.750~0.775 | - | 0.4322 | 0.4325 | 0.4320 | 0.4324 | 0.4320 | - |

| 0.775~0.800 | - | 0.7322 | 0.7323 | 0.7324 | 0.7324 | 0.7326 | - |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, J.-J.; Chang, C.-P.; Chen, S. How Does Distress Acquisition Incentivized by Government Purchases of Distressed Loans Affect Bank Default Risk? Risks 2018, 6, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks6020039

Lin J-J, Chang C-P, Chen S. How Does Distress Acquisition Incentivized by Government Purchases of Distressed Loans Affect Bank Default Risk? Risks. 2018; 6(2):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks6020039

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Jyh-Jiuan, Chuen-Ping Chang, and Shi Chen. 2018. "How Does Distress Acquisition Incentivized by Government Purchases of Distressed Loans Affect Bank Default Risk?" Risks 6, no. 2: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks6020039

APA StyleLin, J.-J., Chang, C.-P., & Chen, S. (2018). How Does Distress Acquisition Incentivized by Government Purchases of Distressed Loans Affect Bank Default Risk? Risks, 6(2), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks6020039