Bubbles, Blind-Spots and Brexit

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Literature

2.1. Political Modelling

2.2. Bubbles and Crashes in Financial Markets

3. The Probability Model

4. Empirical Analysis and Data

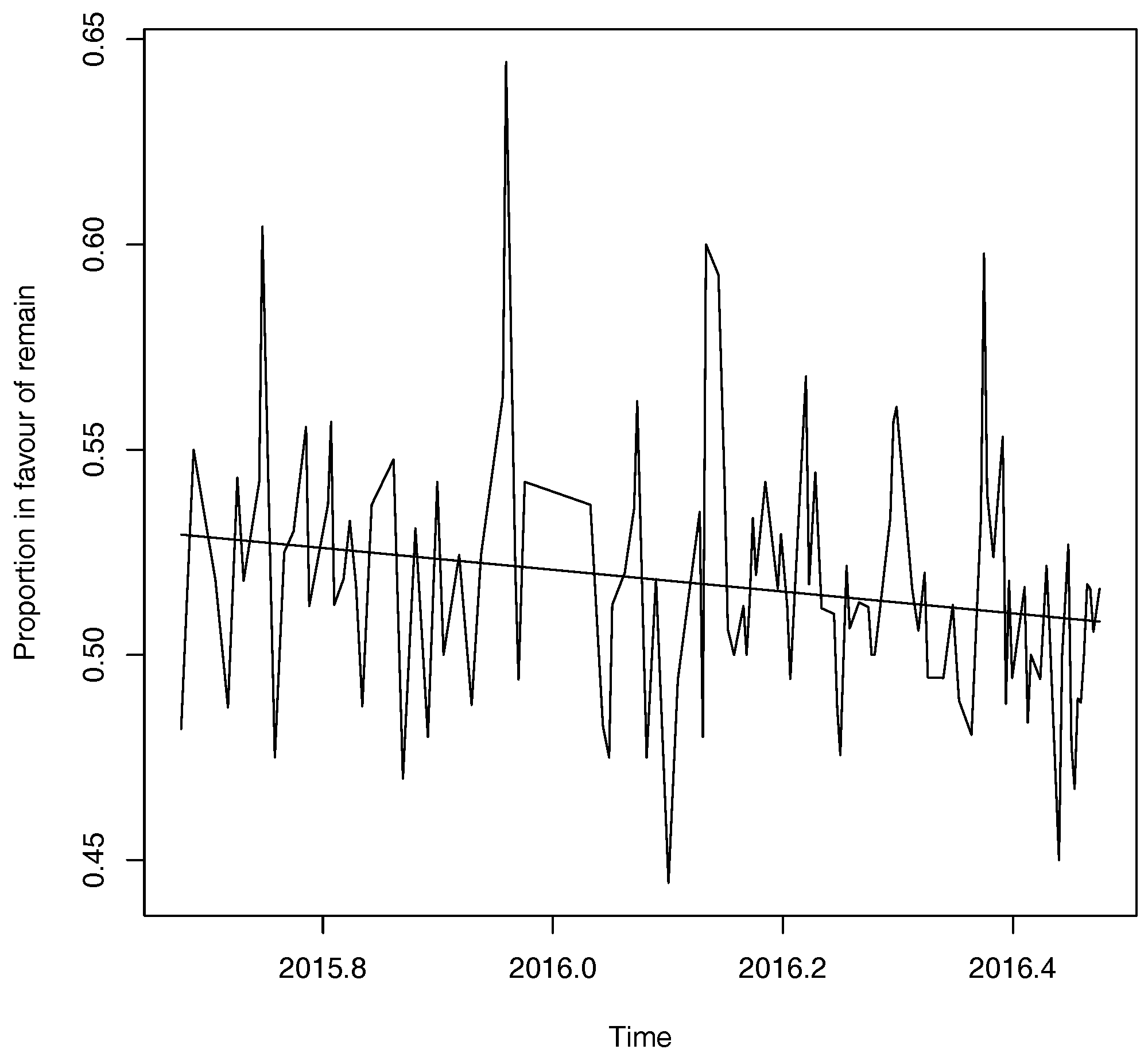

4.1. Opinion Polls

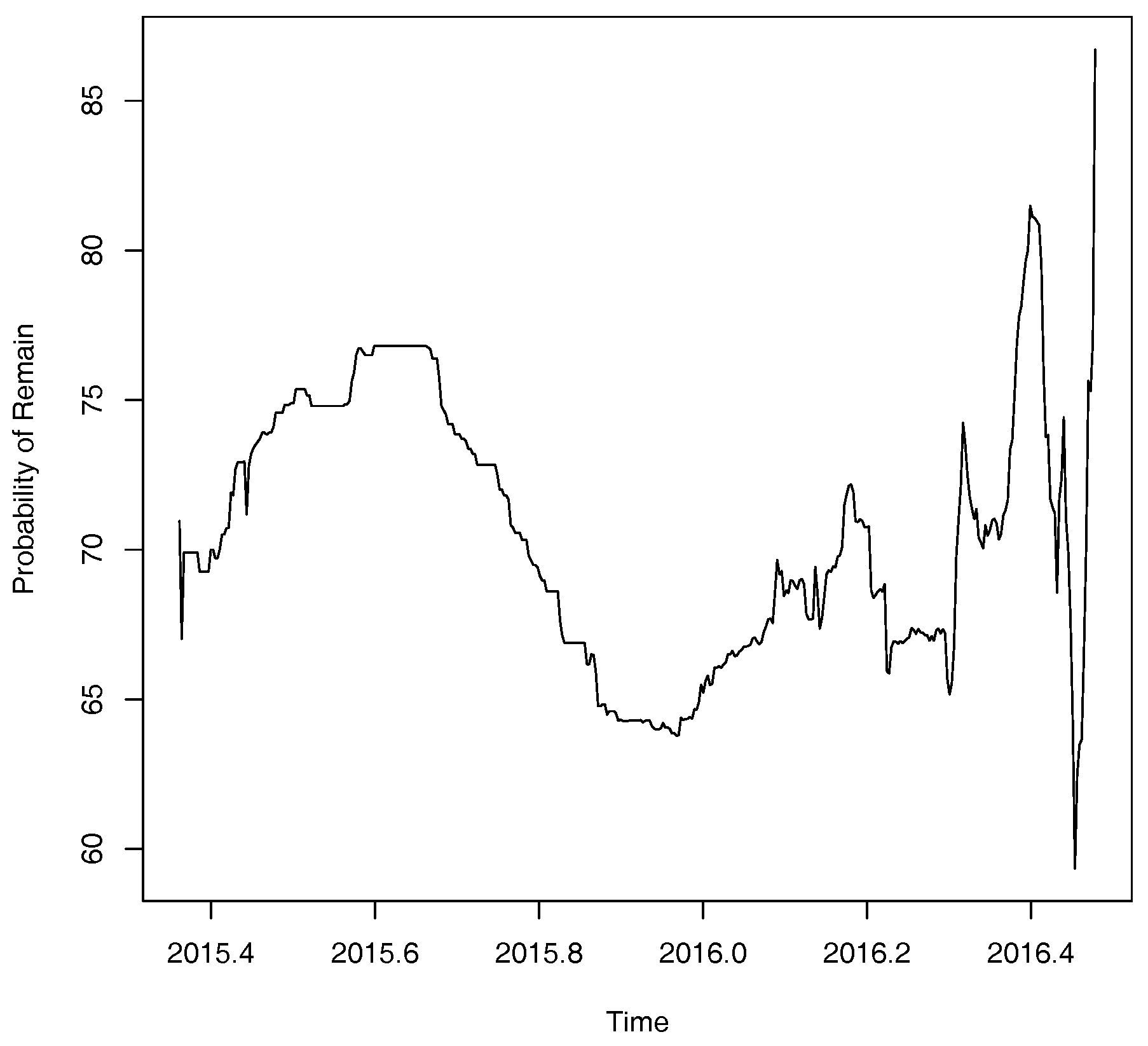

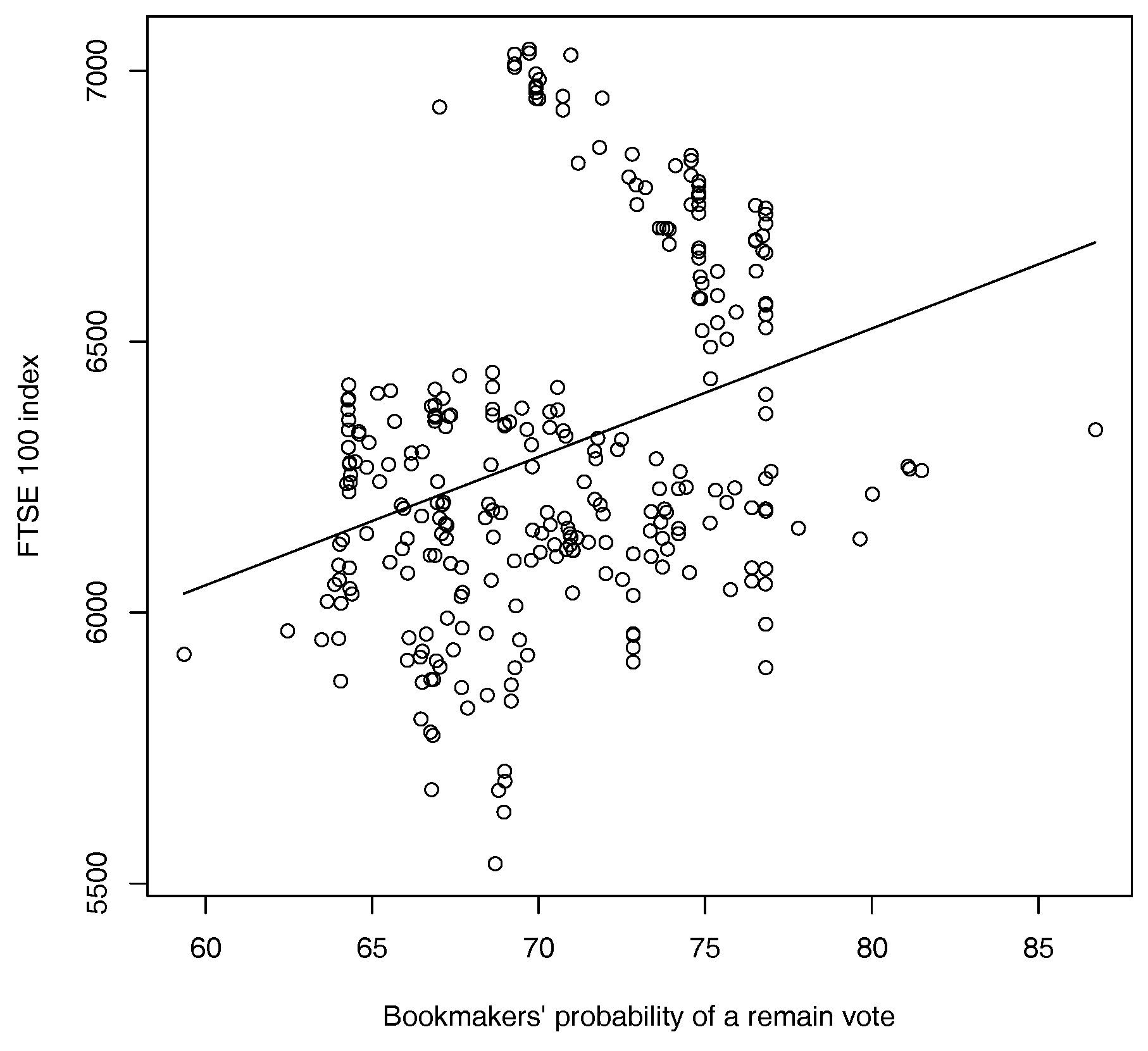

4.2. Betting Odds

5. Conclusions and Further Work

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

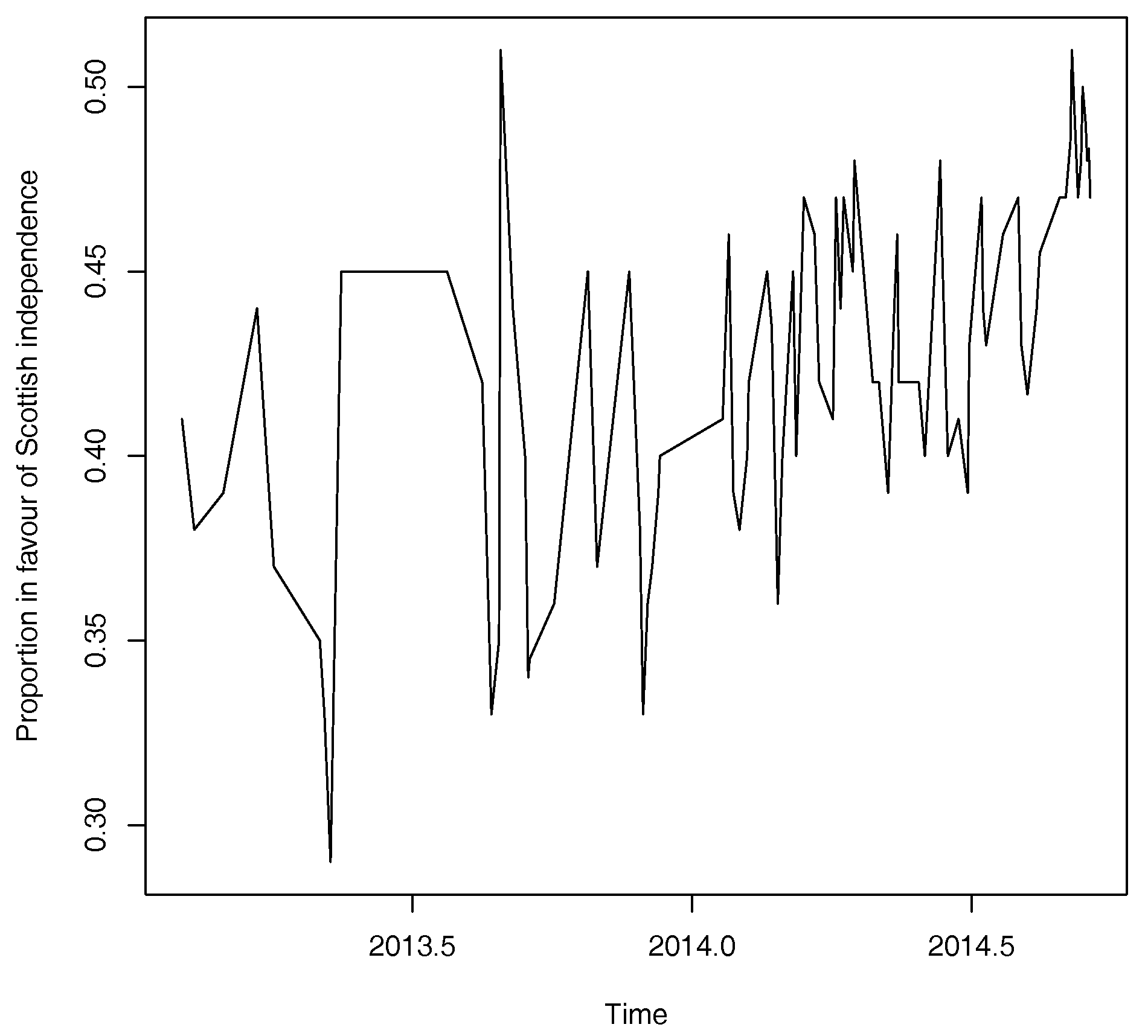

Appendix A. The 2014 Scottish Independence Referendum

References

- Alesina, Alberto, and Nouriel Roubini. 1992. Political cycles in OECD economies. The Review of Economic Studies 59: 663–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, Joyce E., Forrest D. Nelson, and Thomas A. Rietz. 2008. Prediction market accuracy in the long run. International Journal of Forecasting 24: 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, Nicholas H., and John M. Fry. 2010. Regression: Linear Models in Stattics. London, Dordtrecht, Heidelberg, New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, Olivier J., and Mark W. Watson. 1982. Bubbles, rational expectations and financial markets. In Crises in the Economic and Financial Structure. Edited by P. Wachtel. Lexington: D. C. Heathand Company, pp. 295–316. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah, Eng-Tuck, and John Fry. 2015. Speculative bubbles in Bitcoin markets? An empirical investigation into the fundamental value of Bitcoin. Economics Letters 130: 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernov, Dmitry, and Didier Sornette. 2016. MAn-Made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment. Heidelberg, New York, Dordtrecht, London: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Iain J., and Saeed Amen. 2017. Implied distributions from GBPUSD risk-reversals and implication for Brexit scenarios. Risks 5: 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diba, Behzad T., and Herschel I. Grossman. 1988. Explosive rational bubbles in stock prices? The American Economic Review 78: 520–30. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, Robert S., and Christopher Wlezien. 2008. Are political markets really superior to polls as election predictors? Public Opinion Quarterly 72: 190–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, Robert S., and Christopher Wlezien. 2012. Markets vs. polls as election predictors: An historical assessment. Electoral Studies 31: 532–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, George W. 1991. Pitfalls in testing for explosive bubbles in asset prices. The American Economic Review 81: 922–30. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French. 1988. Permanent and transitory components of stock prices. Journal of Political Economy 96: 246–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Stephen D. 2016. Putting it all together and forecasting who governs: The 2015 British general election. Electoral Studies 41: 234–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Stephen D., and Michael S. Lewis-Beck. 2016. Forecasting the 2015 British general election: The 1992 debacle all over again? Electoral Studies 41: 225–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, Robert, Will Jennings, Mark Pickup, and Christopher Wleizen. 2016. From polls to votes to seats: Forecasting the 2015 British general election. Electoral Studies 41: 244–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, John. 2012. Exogenous and endogenous crashes as phase transitions in complex financial systems. The European Physical Journal B 85: 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, John. 2015. Stochastic modelling for financial bubbles and policy. Cogent Economics and Finance 3: 1002152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, John, and Eng-Tuck Cheah. 2016. Negative bubbles and shocks in cryptocurrency markets. International Review of Financial Analysis 47: 343–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandar, John, Richard Zuber, Thomas O’Brien, and Ben Russo. 1988. Testing rationality in the point spread betting market. The Journal of Finance 43: 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürkaynak, Refet S. 2008. Econometric tests of asset price bubbles: Taking stock. Journal of Economic Surveys 22: 166–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harras, Georges, and Didier Sornette. 2011. How to grow a bubble: A model of myopic adapting agents. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 80: 137–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendershott, Patric H., Robert J. Hendershott, and Charles R.W. Ward. 2003. Corporate equity and commercial property market “bubbles”. Urban Studies 40: 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron, Michael C., James Lavin, Donald Cram, and Jay Silver. 1999. Measurement of political effects in the United States economy: A study of the 1992 presidential election. Economics and Politics 11: 51–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, Mathias, Michael U. Krause, and Thomas Laubach. 2012. Trend growth expectations and U.S. house prices before and after the crisis. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 83: 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hott, Christian, and Pierre Monnin. 2008. Fundamental real estate prices: An empirical estimation with international data. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 36: 427–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüsler, Andreas, Didier Sornette, and Cars H. Hommes. 2013. Super-exponential bubbles in lab experiemnts: Evidence for anchoring over-optimistic expectations on price. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 92: 304–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, Herbert. 1944. Do they tell the truth? The Public Opinion Quarterly 8: 557–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, Anders, Olivier Ledoit, and Didier Sornette. 2000. Crashes as critical points. International Journal of Theoretical and Applied Finance 3: 219–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Dominic. 2004. Overconfidence and War: The Havoc and Glory of Positive Illusions. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kindelberger, Charles P., and Robert Z. Aliber. 2005. Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, 5th ed. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, Steven G., and Michael E. Sobel. 2004. Forecasting the vote: A theoretical comparison of election markets and public opinion polls. Political Analysis 12: 277–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lad, Frank. 1996. Operational, Subjective Statistical Methods: A Mathematical, Philosophical and Historical Introduction. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh, Andrew, and Justin Wolfers. 2006. Competing approaches to forecasting elections: economic models, opinion polling and prediction markets. Economic Record 82: 325–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S., Richard Nadeau, and Eric Bélanger. 2016. The British general election: Synthetic forecasts. Electoral Studies 41: 264–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, Roderick J.A. 1988. Missing-data adjustments in large surveys. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 6: 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillart, T., D. Sornette, S. Frei, T. Duebendorfer, and A. Saichev. 2011. Quantification of deviations from rationality with heavy tails in human dynamics. Physical Review E 83: 056101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmendier, Ulrike, and Geoffrey Tate. 2005. CEO overconfidence and corporate investment. The Journal of Finance 60: 2661–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Don A., and Paul J. Healy. 2008. The trouble with overconfidence. Psychological Review 208: 502–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murr, Andreas E. 2016. The wisdom of crowds: What do citizens forecast for the 2015 British general election? Electoral Studies 41: 283–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehler, Andreas, Matthias Horn, and Stefan Wendt. 2017. Brexit: Short-term stock price effects and the impact of firm-level internationalization. Finance Research Letters 22: 175–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J. Gregory. 2010. The Bradley Effect:mediated reality of race and politics in the 2008 US presidential election. American Behavioral Scientist 54: 417–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prechter, Robert Rougelot, Jr. 1999. The Wave Principle of Human Behaviour and the New Science of Socionomics. Gainesville: New Classics Library. [Google Scholar]

- Prechter, Robert R., Jr., Deepak Goel, Wayne D. Parker, and Matthew Lampert. 2012. Social mood, stock market performance, and US presidential elections: A socionomic perspective on voting results. SAGE Open 2: 2158244012459194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronin, Emily, Daniel Y. Lin, and Lee Ross. 2002. The bias blind spot: perceptions of bias in self versus others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 28: 369–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhode, Paul W., and Koleman S. Strumpf. 2004. Historical presidential betting markets. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 18: 127–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoff, Kenneth S. 1990. Equilibrium political business cycles. The American Economic Review 80: 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild, David. 2009. Forecasting elections: comparing prediction markets, polls and their biases. Public Opinion Quarterly 73: 895–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Donald B., Hal S. Stern, and Vasja Vehovar. 1995. Handling “don’t know” survey responses: The case of the Slovenian plebiscite. Journal of the American Statistical Association 90: 822–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiller, Robert J. 2005. Irrational Exuberance, 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Hyun Song. 1993. Measuring the incidence of insider trading in a market for state-contingent claims. The Economic Journal 103: 1141–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sornette, D. 2003. Why Stock Markets Crash: Critical Events in Complex Financial Systems. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sornette, Didier. 2006. Critical Phenomena in Natural Sciences: Chaos, Fractals, Selforganization and Disorder: Concepts and Tools, 2nd ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, Peter. 2016. Will the UK Leave the EU? Keeping Track of the Polls, Bookmaker Odds, and the Financial Markets. The Daily Telegraph. June 20. Available online: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2016/02/22/will-the-uk-leave-the-eu-how-to-track-the-odds-of-a-brexit/ (accessed on 17 July 2017).

- Spence, Peter, and Tim Wallace. 2016. City Bets on Pound to Suffer Bigger Plunge Than ‘Black Wednesday’ After Brexit Vote. The Daily Telegraph. June 18. Available online: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2016/06/18/city-bets-on-pound-to-suffer-bigger-plunge-than-black-wednesday (accessed on 17 July 2017).

- Štrumbelj, Erik. 2014. On determining probability forecasts from betting odds. International Journal of Forecasting 30: 934–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, Lawrence H. 1986. Does the stock market rationally reflect fundamental values? The Journal of Finance 41: 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarran, Brian. 2016. The economy: A Brexit vote winner? Significance 13: 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan Williams, L. 1999. Information efficiency in betting markets: A survey. Bulletin of Economic Research 51: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan Williams, L., and J. James Reade. 2016. Forecasting elections. Journal of Forecasting 35: 308–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteley, Paul. 2016. Why do voters lie to the pollsters? Political Insight 7: 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Wanfeng, Ryan Woodard, and Didier Sornette. 2012. Diagnosis and prediction of rebounds in financial markets. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 391: 1361–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeira, Joseph. 1997. Informational overshooting, booms and crashes. Journal of Monetary Economics 43: 237–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Wei-Xing, and Didier Sornette. 2006. Is there a real-estate bubble in the US? Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications 361: 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | By over-confident we mean over-precise in their estimates of the underlying risks involved (see Section 3). |

| 2 | The average number of “don’t know” responses in the opinion polls studied here is 15% (standard deviation 0.35%). Omitting “don’t know” responses follows the standard way in which opinion poll data has been used to make political forecasts in the literature (see, e.g., Leigh and Wolfers 2006). Further, the closeness of the final vote coupled with empirical evidence from general survey modelling (Little 1988) and other political modelling work (Rubin et al. 1995) suggests that this approach should lead to reasonable results in practice. Non-ignorable missing data models for political polls have been considered in related problems (Rubin et al. 1995). However, this would require additional modelling assumptions that in practice would be difficult justify and would be unlikely to lead to significant improvements (see, e.g., Rubin et al. 1995). |

| Dates | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| September 2015–January 2016 | 7.2002 | 0.0072 |

| September 2015–Feburary 2016 | 14.0192 | 0.0002 |

| September 2015–March 2016 | 12.0572 | 0.0005 |

| September 2015–April 2016 | 9.4774 | 0.0021 |

| September 2015–May 2016 | 20.4255 | 0.0000 |

| September 2015–June 2016 | 13.5763 | 0.0002 |

| Parameter | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | 69.8372 *** | 70.277 *** |

| (10.885) | (11.028) | |

| −0.8938 | ||

| (−0.067) | ||

| 13.169 | ||

| (−0.147) |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fry, J.; Brint, A. Bubbles, Blind-Spots and Brexit. Risks 2017, 5, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks5030037

Fry J, Brint A. Bubbles, Blind-Spots and Brexit. Risks. 2017; 5(3):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks5030037

Chicago/Turabian StyleFry, John, and Andrew Brint. 2017. "Bubbles, Blind-Spots and Brexit" Risks 5, no. 3: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks5030037

APA StyleFry, J., & Brint, A. (2017). Bubbles, Blind-Spots and Brexit. Risks, 5(3), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks5030037