Abstract

This research examines the cognitive and psychological mechanisms underlying young adults’ reactions to ESG-labeled online advertisements, specifically resistance to persuasion and purchase intention. Based on dual-process theories of persuasion and digital literacy theory, we develop and test a structural equation model (SEM) of perceived greenwashing, online advertising literacy, source credibility, persuasion knowledge, and advertising skepticism as predictors of behavioral intention. Data were gathered from 690 Greek consumers between the ages of 18–35 years through an online survey. All the direct effects hypothesized were statistically significant, while advertising skepticism was the strongest direct predictor of purchase intention. Mediation tests indicated that persuasion knowledge and skepticism partially mediated perceptions of greenwashing, literacy, and credibility effects, in favor of a complementary dual-route process of ESG message evaluation. Multi-group comparisons revealed significant moderation effects across gender, age, education, ESG familiarity, influencer trust, and ad-avoidance behavior. Most strikingly, women evidenced stronger resistance effects via persuasion knowledge, whereas younger users and those with lower familiarity with ESG topics were more susceptible to skepticism and greenwashing. Education supported the processing of source credibility and digital literacy cues, underlining the contribution of informational capital to persuasion resilience. The results provide theoretical contributions to digital persuasion and resistance with practical implications for marketers, educators, and policymakers seeking to develop ethical ESG communication. Future research is invited to broaden cross-cultural understanding, investigate emotional mediators, and incorporate experimental approaches to foster consumer skepticism and trust knowledge in digital sustainability messages.

1. Introduction

ESG messaging has emerged as the dominant trend in modern marketing, as companies increasingly emerge as ethically responsible stakeholders to appeal to consumers who are concerned about sustainability (De Freitas Netto et al. 2020; Ktisti et al. 2022). Across all mainstream and digital media, ESG messaging has reached saturation point from green product branding to corporate social media efforts. But it has also created opportunities for greenwashing—the tendency to deceive or overstate claims of environmental or social responsibility for the sake of brand reputation, not any actual environmental or social benefit (Lima et al. 2024; Raghunandan and Rajgopal 2022).

Recent studies have shown that greenwashing not only occurs in the form of clearly deceptive claims but also, less obviously, using evasive terms, unverifiable claims regarding the environment and influencer sponsorship with inadequate disclosure (Raghunandan and Rajgopal 2022; Santos et al. 2024). More than half of all green statements within the European Union are deemed to be misleading or unsubstantiated. The problem is particularly acute in online advertising spaces, where influencer marketing, emotive storytelling, and platform-based nudges can potentially blur the distinction between substantive ESG action and performative signaling (Santos et al. 2024; Yang et al. 2020). The risks are heightened in areas like educational technology (EdTech) and e-commerce, where sustainability messaging typically reaches consumers via algorithms, pop-ups, and curated content—with neither open accountability nor verification.

Greenwashing is highly perilous, individually as well as cumulatively. For consumers, misleading ESG advertising dissolves trust, triggers confusion, and distorts decision-making. Empirical research has established perceived greenwashing with lower brand trust, lower product satisfaction, and lower purchase intentions. At the macro level, it refutes the overall credibility of green advertising and risks diluting the effectiveness of truly sustainable practice (Akram et al. 2024; Borah et al. 2024). Apart from reputational risk, greenwashing is now a material business risk, attracting the attention of investors, regulators, and activist groups. Regulatory frameworks like the European Green Claims Directive are indicative of an increasing regulatory imperative for substantiable ESG communications. Economically, greenwashing entities risk not just reputational harm but also decreased investor trust, higher cost of capital, and loss of brand value—particularly where ESG performance is touted as a differentiator (Borah et al. 2024; Causevic et al. 2022).

Young consumers, especially Generation Z and younger millennials, are the most significant audience for digital ESG communication and are increasingly cynical about its veracity (Duffett and Mxunyelwa 2025; Das et al. 2025). They care about sustainability and social justice and habitually call brands to account for ethical dissonance. But their frequent exposure to online content and emotive appeals with little ability to scrutinize advanced ESG claims puts them at risk of profoundly sophisticated greenwashing tactics. While Gen Z is more ad- and persuasion-savvy, studies have established that even extremely skeptical instances are vulnerable to source credibility, emotional framing, and implicit cues in persuasive online settings. Ironically, media-skeptical skepticism is not always a cure for manipulative influence—particularly when messages are from credentialed sources or sites, or environmental claims are presented in sweet-tasting packages but have hollow meaning (Duffett and Mxunyelwa 2025; Das et al. 2025).

Theoretically, how young consumers react to ESG-labeled web ads must be responded to by an integration of strategies like the Persuasion Knowledge Model, Theory of Planned Behavior, and source credibility models (Fella and Bausa 2024; Dangelico et al. 2024; Chwialkowska et al. 2024). These conclude that green marketing effects do not solely lie with message content but also cognitive processing (e.g., detection of intent to persuade), emotional experience, perceived source trustworthiness, and context-specific digital design features. In addition, variables like perceived greenwashing, ad skepticism, ESG trust, and digital ad literacy not only act as antecedents but also as mediators of behavioral intentions, influencing how consumers process, judge, and respond to communications of sustainability (De Freitas Netto et al. 2020; Dangelico et al. 2024; Chwialkowska et al. 2024). As the literature continues to grow, it gravitates towards complex, multi-path models that reflect the psychological richness of digital persuasion—particularly that of younger consumers who must negotiate a dense and morally complex ad environment (Duffett and Mxunyelwa 2025; Díaz et al. 2024; Fang 2024).

In spite of an increasing body of research on greenwashing and electronic persuasion, not much empirical research exists that synthesizes these fields into one area of study—in the case of ESG-labeled marketing to children and young people (Ktisti et al. 2022; Fehr 2023; Huang et al. 2024; Le et al. 2024). Most of the existing research studies investigate greenwashing and persuasion literacy as distinct constructs with little effort towards creating holistic behavioral theories that explain youth cognition and emotion about marketing targeting sustainability. Although previous research has proven greenwashing to undermine trust and lower purchase intentions, no overarching models have been developed that are focused on the interaction among perceived greenwashing, persuasion knowledge, advertisement skepticism, source credibility, and behavior intentions in web contexts (Le et al. 2024; Meet et al. 2024; Nguyen-Viet and Thanh Tran 2024).

In addition, the majority of recent studies have focused on business segments like fast fashion, food, and hospitality and the practice of green marketing in these fields with minimal attention to other areas of business like educational technology (EdTech), where ESG disclosure is becoming deeply integrated into learning infrastructures and influencer marketing-driven content. This overlooks a growing business landscape where brand communication is colliding with learning interaction (Duffett and Mxunyelwa 2025; Gregory 2024). Furthermore, there has been limited academic study of Generation Z—a generation that not only suffers from disproportionate exposure to digital ESG messaging but one also that exhibits distinctive modes of idealism, cynicism, and media critical thinking. The failure to deeply study the complex reactions of this generation is a systematic flaw, especially as they become leading decision-makers and formulators of emerging consumer standards (Duffett and Mxunyelwa 2025; Gregory 2024). This research fills a crucial blind spot in this nascent debate through empirical modeling of the psychological processes by which young Greek consumers assess and react to ESG-branded web ads. Centering on industries like EdTech and retail—where ESG content goes increasingly mainstream but sometimes poorly regulated—research examines how perceived greenwashing, credibility of the source, and literacy with the ad interact to affect skepticism, knowledge of persuasion, and buying intention. By focusing on Gen Z in a culturally homogenous sample of a country, the study strives to generalize important cognitive and affective determinants of ESG ad evaluation, thus achieving theoretical and practical implications to ethical marketing, regulation, and consumer protection (Ktisti et al. 2022; Huang et al. 2024).

The Greek context is a first-rate setting where one can see how younger consumers react towards ESG-labeled ads, particularly in online areas such as EdTech and online shopping (Duffett and Mxunyelwa 2025; Díaz et al. 2024; Fang 2024). Greece has a unique set of sociopolitical, economic, and cultural circumstances that determine reception, evaluation, and reaction to ESG messages. While on the one hand, young consumers’ online activity is significant and Gen Z is defined by strong media literacy, pervasive exposure to social network influencers, and familiarity with target areas of advertising, on the other hand, at the European level, Greece is lower in institutional trust, particularly as it concerns corporate communications and the media (Fella and Bausa 2024; Dangelico et al. 2024; Chwialkowska et al. 2024). This deficit of trust, added to increased economic exposure and recent political unrest, renders a population susceptible to appeals of social justice but wary of insincere messages. Greek consumers, particularly young people, are thus well placed to identify contradiction in ESG messages and are thus perfect subjects with which to test how skepticism and awareness of persuasion respond to sustainability claims, whereas in highly regulated and well-established ESG systems of markets, Greece’s fragmented sustainability story can fuel greater skepticism—most notably on the part of digitally literate youth filtering through ambiguous or inflated ESG messaging (Le et al. 2024; Meet et al. 2024; Nguyen-Viet and Thanh Tran 2024). Meanwhile, amidst the economically struggling but socially aware Gen Z of Greece lies an idealism that is combined with critical thinking to make them all the more receptive to the gap between brand messaging and perceived authenticity (Duffett and Mxunyelwa 2025; Gregory 2024). This duality renders the Greek sample extremely relevant in testing the psychological interplay of greenwashing, persuasion knowledge, and advertising skepticism in ESG communication. However, cultural specificity may constrain generalizability. Ad credibility norms, nature-based norms, and emotive framing norms vary significantly by country (Le et al. 2024; Meet et al. 2024; Nguyen-Viet and Thanh Tran 2024). As great a context as Greece is for a study of the psychological impact of vague ESG messages, subsequent studies will have to cross-validate these findings in more regulatory or digitally amplified contexts to evaluate the strength of the model (Le et al. 2024; Meet et al. 2024; Nguyen-Viet and Thanh Tran 2024). In this instance, the Greek case serves as a stress test of ESG influence models and as a signal of the necessity to consider contextual dynamics in digital sustainability communication research.

The results revealed that all direct effects hypothesized, for example, the impact of perceived greenwashing, digital advertisement literacy, and source credibility on purchase intention, were statistically confirmed. Persuasion knowledge and advertisement skepticism also proved to be effective mediators, in favor of a dual-process theory of digital persuasion. Multi-group comparisons also revealed the presence of differences between demographic and psychographic subgroups, such as age, gender, ESG familiarity, ad-skipping tendency, and education level. These findings highlight the multifaceted and contextual nature of consumer reactions to ESG-labeled online ads, providing both theoretical insights and practical recommendations for improved sustainability communication.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the major literature regarding ESG advertising, knowledge of persuasion, and digital competency. Section 3 presents the conceptual model and hypotheses. Section 4 describes the methodology, which includes data collection and SEM procedures. Section 5 presents the results, including direct, mediated, and moderated effects. Section 6 presents practical implications, and Section 7 concludes with limitations and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Greenwashing and the Rise of ESG-Labeled Advertising

ESG-labeled advertising is online marketing communications specifically foregrounding a business’s environmental, social, or governance (ESG) initiatives, including claims of sustainability, social responsibility stories, or ethical governance initiatives (Ktisti et al. 2022; Huang et al. 2024). Increasing numbers of studies deconstruct critically exploring the discrepancy between rising prevalence of ESG-palette promotions and genuineness of corporate sustainability efforts. He et al. (2023) initiates the term “ESG fund style drift” to describe the gap between declared sustainability goals and real-world investment behaviors that erodes investor trust. Although such drift is correlated with poorer returns and smaller fund size, the research finds no material impact on later performance—indicating that reputational misalignment may matter more to stakeholders than underlying outcomes.

This reputational aspect is also heightened in the work of Raghunandan and Rajgopal (2022), where he explains this paradox by demonstrating that certain U.S.-based ESG funds invest in firms with abysmal labor or environmental track records yet return top-shelf ESG ratings. These bloated ratings are a systemic shortfall wherein ESG analysis repeatedly prioritizes disclosure quantity over material content and exposing an performative aspect of ESG branding. Other studies offer a more optimistic outlook. Similarly, Díaz et al. (2024), delves into ESG investment strategies for the energy sector and concludes that ESG-labeled portfolios are able to outperform regular indices, particularly when combined with behavioral finance measures such as Prospect Theory Value. However, the study does not ask whether or not the ESG scores reflect substance in sustainability or only market signaling.

On the regulatory side, the work of Rotman and David-Pennington (2024), refers to the absence of existing guidance. The study advocates for revisions to the FTC Green Guides to address confusing and unsubstantiated ESG claims at the brand level. In the study, the authors find public support for a legal definition of “sustainability,” which is not found in current regulation despite its frequent use in advertising. In their examination of comments to the Green Guides, they discover pervasive calls for definition of the term “sustainability,” used more and more now despite never being defined.

The demand for tighter regulation is in tandem with newer European proposals such as the Green Claims Directive aimed at limiting imprecise or unsubstantiable green labels. Stromberg and Bali Swain (2024), take regulatory theory further by also advocating citizen monitoring as a remedy, especially where institutional enforcement is lacking. Taking the mining sector as an example, they advocate pluralistic transparency devices aimed at encouraging truthful environmental disclosure.

Whereas institutional or regulatory settings dominate most of the literature, Cinceoglu and Strauß (2025), present a fresh discovery in putting internal dissent into the limelight within the ESG context. In interviews and analysis of media content, the authors illustrate how whistleblowers such as Desiree Fixler have been exposing institutional greenwashing from within. The research highlights the media function as an arena for accountability, advancing that reputational harm usually starts with self-blame before evoking public or regulatory penalties. In addition to the incisive scrutiny of wartime ESG reframings by Causevic et al. (2022), he indicts the labeling of weapons manufacture as “sustainable” in invasion-aftermath Europe as ESG frameworks being precariously pliable and ideologically contradictory—vulnerable to opportunist re-reading under geopolitics strains.

With such dynamics in mind, greenwashing has even dominated the marketing and risk management literature (Causevic et al. 2022; Díaz et al. 2024; Cinceoglu and Strauß 2025). Consumers have been resisting ESG claims more strongly than ever before, most notably among younger and digitally native demographics like Generation Z, with both higher sustainability aspirations and higher ad literacy. But while the literature has demonstrated the harmful impact of greenwashing on consumer attitudes and trust, few have modeled these alongside variables like persuasion knowledge, source credibility, or ad literacy—especially for the case of digitally mediated ESG campaigns in industries like EdTech and e-tailing.

Though there has been rich scholarship and policy debate, there are not enough empirical studies on how consumer-owned perceptions of greenwashing, or subjective opinion about deceptive ESG message intent, influence underlying psychological constructs such as source credibility, skepticism towards advertising, and persuasion knowledge in digital environments (Causevic et al. 2022; Díaz et al. 2024; He et al. 2023; Cinceoglu and Strauß 2025). Much of the literature focuses on institutional stakeholders (e.g., regulators, investment funds), with relatively less emphasis on consumer-confronted responses (Raghunandan and Rajgopal 2022; Rotman and David-Pennington 2024). Moreover, there is little empirical focus on younger digitally native consumers of ESG claims, even though such consumers are frequent consumers of advertisements and are strongly environmentally aware (Rotman and David-Pennington 2024; Stromberg and Bali Swain 2024).

This research fills this gap by conceptualizing perceived greenwashing as an essential precursor to young adults’ reactions to ESG-labeled online ads. The theoretical tradition departs from normative or ethical reasoning, instead defining greenwashing as a measurable risk factor with behavior, reputation, and monetary impacts. This is especially pertinent for high-developing industries such as EdTech and e-commerce, where algorithms, influencers, and platform dynamics obfuscate the lines between persuasion and manipulation.

Collectively, these studies shed light on major tensions and contradictions in the ESG communication environment. First, as much as ESG-themed messages resonate with investor and consumer intentions, the underlying metrics and promises tend to be shallow or inconsistent. Second, the disconnect between symbolic signaling (e.g., voluntary reporting) and material performance (e.g., compliance or effect) sets the stage for ripe greenwashing (Raghunandan and Rajgopal 2022; He et al. 2023). Third, the existing regulation is siloed and backward-looking with patches of overlapping jurisdictional voids among global and national authorities. Finally, the emergence of digital platforms and influencer channels makes ESG claim detection and interpretation more difficult because the trustworthiness of content and sources is more and more being intermediated by algorithmic reach and social endorsement as opposed to third-party validation. In addition to ethics and law, greenwashing is also a material business risk. Companies accused of greenwashing tend to experience declining stock prices, higher cost of capital, and reduced brand value (Díaz et al. 2024; Cinceoglu and Strauß 2025). Research indicates that such companies experience higher unsystematic risk and may not be able to keep investors, customers, and staff. Reputation loss can be especially severe for brands that establish their reputation on sustainability where credibility is a competitive advantage. In this regard, perceived greenwashing is not only a communicative error but also a measurable risk factor with attendant behavioral, reputation, and financial effects (Causevic et al. 2022; Cinceoglu and Strauß 2025).

2.2. Digital Persuasion, Source Credibility, and Psychological Processing

In online environments, the effectiveness of ESG-labeled advertising relies greatly on customers’ cognitive and emotional processing—most specifically that of Gen Z, who are very digitally literate and more attuned to manipulation (Akram et al. 2024; Borah et al. 2024; Chwialkowska et al. 2024; Crapa et al. 2024). Underlying theories like the Persuasion Knowledge Model (PKM) and the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) provide a solid basis for explaining such psychological processes. PKM posits that consumers, particularly media-savvy audiences such as Gen Z, construct intuitive safeguards against perceived manipulative attempts. When audiences can recognize manipulative intentions, then skepticism toward advertising will be activated, which mediates or curtails the persuasiveness of a message (Fella and Bausa 2024; Fehr 2023; Higueras-Castillo et al. 2024). This was empirically established by Nguyen-Viet et al. (2024), as they showed greenwashing elicited skepticism, which entirely mediated the adverse association between ESG claims and purchase intention.

The Elaboration Likelihood Model extends this by explaining how persuasion is achieved through a central (argument-based) or peripheral (cue-based) route, depending on message complexity and consumer engagement (Borah et al. 2024; Crapa et al. 2024; Herman et al. 2021). Source credibility, a powerful peripheral cue, has been shown to be especially effective for ESG advertising. Genuine micro-influencers have been shown to elicit higher levels of engagement and trust than classic celebrity endorsements or corporate websites (Nguyen-Viet and Thanh Tran 2024; Crapa et al. 2024; Higueras-Castillo et al. 2024). For example, Lima et al. (2024), combines value–belief–norm theory and ELM and reaches the conclusion that pro-environmental behavior is more likely when source credibility and audience values are congruent. Once more, Mladenovic et al. (2024), demonstrate how even low-credibility green statements can influence on the basis of high-quality product cues such as naturalness. But skepticism has a context-sensitive effect. Fella and Bausa (2024), demonstrate that consumers will detect greenwashing only if they are specifically invited to scrutinize sustainability communications. This supports the proposition that skepticism is an active—not automatic—response.

Emotional framing also has a similar impact. Based on a meta-analysis of guilt appeals, Peng et al. (2023), portrays that guilt can be powerful but is prone to being conditioned by perceived responsibility and closeness. Manipulative intensity of feeling can prompt defensive avoidance, but pride or hope appeals are likely to elicit more empowering responses. Tran et al. (2025), reports this from evidence in the hospitality industry, where environmental actions provoked pride and moral excellence, which resulted in customer citizenship behaviors. Emotional appeals can thus support or damage persuasive effects based on message framing and audience preparedness (Nguyen-Viet and Thanh Tran 2024; Crapa et al. 2024; Higueras-Castillo et al. 2024). Apart from green trust, other internal factors such as authenticity also act as mediators of ESG communication. Akram et al. (2024), find that green brand trust mediates the influence of promotional tools on purchase intentions, and Borah et al. (2024), show that trust moderates the green purchasing behaviors of Gen Z. Even in B2B settings, green trust mediates CSR and brand image effects on purchases as with dual studies by Nguyen-Viet et al. (2024).

Critically, various studies reveal contradictions. While eco-labels and CSR communications normally intend to establish trust, they end up encouraging suspicion where perceived as counterfeit (Díaz et al. 2024; He et al. 2023). Although emotional appeals are likely to mobilize participation, overdependence on guilt or fear may be a turnoff, especially with autonomy-valuing youth. This goes to highlight the double-edged nature of digital persuasion: its tools are strong but susceptible to failure unless executed in close resonance with the audience.

Individually, the studies present an emerging picture of ESG persuasion online (Díaz et al. 2024; He et al. 2023). Triadic interaction among affect, suspicion, and source credibility is a mechanism linking green message receipt. There are gaps in research. Lean models effectively embed these constructs in prediction models that are suitable for adolescents involved in social media contexts. This is the foundation for placing persuasion knowledge and advertising skepticism as mediators and source credibility as an overarching variable in the response model to ESG-tagged online ads by this current research. This research is therefore enriching a more complex behavior model with the ability to explain the complex dynamics between cognition, emotion, and digital media interplays in sustainability communication (Borah et al. 2024; Crapa et al. 2024; Herman et al. 2021).

Theoretical Integration: PKM, ELM, and TPB in ESG-Labeled Advertising Contexts

Collectively, the Persuasion Knowledge Model (PKM), the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM), and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) provide a complementary and multi-level explanation of how young consumers cognitively and emotionally react to ESG-labeled advertisements (Akram et al. 2024; Borah et al. 2024; Chwialkowska et al. 2024; Crapa et al. 2024). Each of these models deals with a subsequent level of psychological processing: PKM describes how people call upon resistance to persuasion attempts the very instant that they detect advertising intent; ELM describes the two routes through which persuasive messages are processed (central vs. peripheral); and TPB models how such attitudinal and evaluative processes obtain converted into behavioral intentions. Integrating these models offers a better explanation of how perceived greenwashing affects not just consumer trust and emotional skepticism but also their intention to adopt pro-environmental behaviors.

PKM aids in accounting for how digital natives, particularly Gen Z, would be more prone to notice and resist persuasion when they perceive manipulative intent behind green claims. As consumer persuasion knowledge develops, consumers employ defense mechanisms like skepticism that can undermine the persuasive impact of ESG communications (Nguyen-Viet and Thanh Tran 2024; Crapa et al. 2024; Higueras-Castillo et al. 2024). This model can especially be applied when considering online and influencer-marketed advertising in which messaging intent is often hidden from view by platform design, personalization technology, or green performance branding. This grounds the cognitive mediators of skepticism and resistance as evoked cognition in the study research on perceived greenwashing (Díaz et al. 2024; He et al. 2023).

At the same time, the ELM constrains this information in terms of specifying processing conditions under which customers consider ESG-labeled messages. For example, highly involved or activated customers will employ the central route within an argument evaluation of message arguments—such as the credibility of ESG claims, usage of third-party endorsement, or disclosure of environmental behavior (Díaz et al. 2024; He et al. 2023). Conversely, in low cognition or motivation, peripheral cues such as emotional appeal, aesthetics, or source credibility are employed by consumers (Borah et al. 2024; Crapa et al. 2024; Herman et al. 2021). Source credibility is, therefore, one of the important peripheral factors that determine persuasion in influencer-based or visual ESG communications. ELM explains why rational and emotional considerations such as persuasion knowledge and skepticism are included in parallel processing channels.

Lastly, TPB situates these cognitive and emotional processes in context through reference to behavior intention, the final dependent variable of the study (Díaz et al. 2024; He et al. 2023). TPB hypothesizes that intention to behave (e.g., buy a sustainable product) is influenced by three central factors, that is, attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control (Akram et al. 2024; Borah et al. 2024; Chwialkowska et al. 2024; Crapa et al. 2024). Attitudes in the research are driven by whether or not the ESG message is seen to be persuasive or misleading; subjective norms are constructed on the foundation of digital literacy, influencer cues, and social media profiles; and perceived control would be impacted by doubt and perceived greenwashing that is empowering or demotivating sustainable decision-making. TPB thus serves as the behavior output layer, predicting how interior psychological assessments blend into stated intent (Díaz et al. 2024; He et al. 2023).

Taken together, the three models form a theoretically coherent framework explaining the entire psychological process running from exposure to ESG messages through to internal judgment and all the way to behavioral intention. Their integration allows the modeling of resistance processes and motivational pathways, thus providing a more comprehensive and ecologically valid exploration of how digital sustainability advertising is processed cognitively by critical and affect-sensitive young consumers.

2.3. Young Consumers’ Reactions and Behavioral Intention in ESG Contexts

Young consumers, particularly Generation Z, are becoming central players in the shift towards sustainable consumption. Their greater sensitivity towards the environment is most typically paired with greater digital engagement, and therefore a unified convergence between green sensitivity and digital engagement. Palmieri et al. (2025), underlines how very tech-savvy young consumers are attuned to green consumption, particularly where social values converge with green values and interactive digital communication channels. Similarly, Theocharis and Tsekouropoulos (2025), verify that the purchasing behavior of Gen Z technology products for sustainability is significantly influenced by digital brand experience, brand loyalty, and brand trust, underpinning the significance of psychological and experiential branding in shaping green purchase intention.

Studies also indicate that Gen Z’s green behaviors are induced by multifaceted drivers. For example, Lopes et al. (2024), indicates the roles of ecological imperative and green willingness as important antecedents of green consumerism in Portugal, while Nguyen et al. (2025), illustrates the effects of green marketing mix strategies on loyalty, perceived quality, and willingness to pay among consumers in Vietnam. Likewise, Varese et al. (2025), illustrates demographic moderators such as education and gender on sustainability action and necessitates context-specific sustainability communication. Yet, the rhetoric of sustainability among young people is not free of paradox. Zhao et al. (2025), detects inconsistency between attitude and behavior, with green attitudes not always manifesting in consistent consumption habits—a phenomenon referred to as the “attitude–behavior gap”. Dangelico et al. (2024), also attests that while environmental concern and perceived usefulness are sound predictors of sustainable beer consumption, gender, and product packaging moderate the intensity of these relationships.

Concurrently, other studies reveal how social influence and brand trust cross-pollinate with green skepticism. Nguyen-Viet et al. (2024), asserts that perceived greenwashing has a direct reverse effect on purchase intention and activates mediators like perceived betrayal and confusion, especially in the electric motorbike sector. The same is argued by Sanchez-Chaparro et al. (2024), cautioning that use of generic ESG labels may enhance the risk of confusion or boomerang by Gen Z consumers—particularly in industries with a track record of past environmental damage—because Gen Z consumers have heightened sensitivity to authenticity cues.

Influencer platforms and social media are also a formative force behind the ESG reaction of Gen Z. Duffett and Mxunyelwa (2025), offer that purchase intent is established through influencer traits like ease-of-use perceptions and credibility through online platforms like Instagram. Their research indicates that platform experience during psychological processing mediates green messages and trust. In parallel, Das et al. (2025), builds upon this by demonstrating how Gen Z’s materialism and novelty-seeking characteristic can be employed to extend their consideration of virtual tourism’s green value—to include values and curiosity in forming sustainable engagement.

All these findings share one thing in common: Gen Z consumers are very committed to sustainability stories but increasingly skeptical of performative or fake branding. Evidence attests that their intent behaviors are motivated by psychological constructs like perceived risk (Zou et al. 2024), emotional attachment (Tran et al. 2025), and identity congruence (Rahimi et al. 2025). However, these intents are mitigated by cognitive overload, message fatigue in the virtual space, and the accelerating complexity of greenwashing strategies.

Lacking rich insights notwithstanding, the current literature remains lacking in a few areas. For starters, there is limited application of persuasion theory and green skepticism as intervening variables. Although research acknowledges message trust and emotional appropriateness impacts, little research replicates the functioning of cognitive filters in conjunction with alternative ESG cues (Raghunandan and Rajgopal 2022; Causevic et al. 2022; Díaz et al. 2024; He et al. 2023). Secondly, most research ignores the platform context, i.e., EdTech and hybrid digital learning-retail environments in which green messaging is being progressively integrated. Last but not least, there is a research need to examine moderating variables like digital ad literacy or eco-involvement, which can weaken or strengthen the influence of perceived greenwashing.

This study addresses the cited gaps by investigating the effects of perceived greenwashing, advertisement source credibility, and advertising literacy on social media on Gen Z’s purchase intentions of products advertised through ESG-tagged online ads. Through the inclusion of persuasion knowledge and skepticism as psychological mediators, the current study advances our understanding of how young consumers process and respond to green claims in digital settings. By double-paying attention to both behavioral intention and cognitive resistance, the research provides theoretical and practical implications for ethical ESG communication.

As per previous studies, it is apparent that ESG-stamped ad responses from young consumers are influenced by a multifaceted array of perceptual, psychological, and contextual factors. Perceived greenwashing, source credibility, persuasion knowledge, and emotional engagement have all been identified as influencing behavior intention—especially in digitally mediated contexts. Yet these factors are rarely applied in concert within an unified theoretical framework, much less one charting the dual context of school and store digital spaces for Generation Z.

To empirically test the dependencies postulated by previous studies, the present study sets out a series of hypotheses underpinned by the above empirical and theoretical basis:

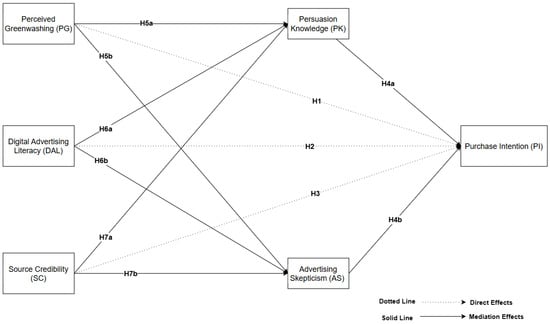

H1.

Persuasion knowledge (PK) positively influences purchase intention (PI).

H2.

Digital advertising literacy (DAL) positively influences purchase intention (PI).

H3.

Advertising skepticism (AS) negatively influences purchase Intention (PI).

H4a.

Persuasion knowledge (PK) has a direct positive effect on purchase intention (PI).

H4b.

Advertising skepticism (AS) has a direct negative effect on purchase intention (PI).

H5a.

The effect of perceived greenwashing (PG) on purchase intention (PI) is mediated by persuasion knowledge (PK).

H5b.

The effect of perceived greenwashing (PG) on purchase intention (PI) is mediated by advertising skepticism (AS).

H6a.

The effect of digital advertising literacy (DAL) on purchase intention (PI) is mediated by persuasion knowledge (PK).

H6b.

The effect of digital advertising literacy (DAL) on purchase intention (PI) is mediated by advertising skepticism (AS).

H7a.

The effect of source credibility (SC) on purchase intention (PI) is mediated by persuasion knowledge (PK).

H7b.

The effect of source credibility (SC) on purchase intention (PI) is mediated by advertising skepticism (AS).

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Conceptual Model and Rationale

At a time when environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues are ever more prominent in digital marketing communications, questions regarding the authenticity and reliability of such claims have become ever more urgent. Young consumers, especially digitally native young people, are habitually subjected to ESG-labeled ads on social media, learning platforms, and e-commerce systems. Yet, the growing evidence of greenwashing—the consumer experience of perceived inaccuracy, exaggeration, or lack of evidence behind a brand’s claims of ESG—has arisen as a signature challenge to effective digital persuasion. Recent findings indicate that perceived greenwashing not only harms brand trust but also triggers psychological resistance in the shape of skepticism and reduced purchase intention (Fella and Bausa 2024; Díaz et al. 2024; Crapa et al. 2024). However, empirical observations hardly capture these effects completely, especially within digitally mediated settings of ESG communication (Fang 2024; Le et al. 2024; Herman et al. 2021; Jiménez and Yang 2008).

This study bridges an important knowledge gap by developing a conceptual model that explains how perceived greenwashing influences the purchase intention of young consumers in response to ESG-labeled online advertisements. Our model positions perceived greenwashing (PGW) as the primary independent variable and predicts that PGW triggers a sequence of cognitive and attitudinal processes that ultimately lower purchase likelihood. Inferring from the Persuasion Knowledge Model (PKM) and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), we theoretically argue that PGW indirectly influences behavior but through two essential mediating processes: persuasion knowledge and skepticism towards advertising (De Freitas Netto et al. 2020; Borah et al. 2024; Chwialkowska et al. 2024; Gregory 2024). Internet advertising literacy sums up the capacity to read critically, evaluate, and interpret internet advertisements. The Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) assumes that consumers with more education will use the central route in processing advertising, considering message content and argument quality (Herman et al. 2021; Palmieri et al. 2025; Nguyen et al. 2025; Obermiller and Spangenberg 1998). Ad literacy would consequently fortify the PGW–mediator relationship since educated consumers will be better able to spot deceptive ESG claims and employ persuasion knowledge or skepticism (Stromberg and Bali Swain 2024; Sarhour 2025; Wang et al. 2024). On the other hand, perceived trustworthiness and expertise of source credibility (e.g., influencer, brand, or platform) can neutralize the negative impact of PGW. For ELM, the periphery cue user will respond favorably to an ESG message if the user has a credible source perception, thus reducing distrust or skepticism (Causevic et al. 2022; Duffett and Mxunyelwa 2025; Das et al. 2025; Crapa et al. 2024).

Persuasion knowledge is consumers’ understanding of advertising’s persuasive intent and their capacity to critically evaluate such attempts. As the Persuasion Knowledge Model (PKM) has argued, consumers, when they perceive a message is attempting to persuade them, especially if it is perceived as manipulative or deceptive, will resort to coping mechanisms like critical thinking or resistance (Das et al. 2025; Fella and Bausa 2024; Fang 2024). People with higher persuasion knowledge of ESG-labeled ads will more likely recognize greenwashing and be less affected by it. It is complemented by ad skepticism, a second mediator uncovered through the propensity to doubt advertisement message intentionality or sincerity. The literature corroborates that greenwashing perceived to a great extent increases skepticism, which negatively affects brand evaluations and lowers behavioral intentions (Zhao et al. 2025; Zou et al. 2024). With these two mediators in place, the model depicts the psychological processing pathways by which PGW damages purchase intention.

Our dependent variable, purchase intention, is an indicator of willingness on the part of consumers to purchase a product or service following exposure to an ESG-branded online ad. It is employed extensively within advertising and sustainable marketing research, and has a strong foundation upon TPB, contending that intention is the ultimate behavior predictor (He et al. 2023; Díaz et al. 2024; Causevic et al. 2022; Raghunandan and Rajgopal 2022). Earlier studies have consistently shown that consumers’ perceptions of greenwashing, i.e., their beliefs that a brand is misleading or deceiving through its ESG statements, in fact decrease green purchase intentions. This factor is therefore deemed theoretically and practically relevant for gauging the success of ESG-based persuasive communications (Causevic et al. 2022; Díaz et al. 2024; He et al. 2023).

As a whole, the conceptual model (Figure 1) integrates theoretical understanding of PKM, ELM, and TPB in order to theorize the behavioral outcomes of perceived greenwashing in digital spaces. Theoretically, it contributes by framing not only the psychological processes (mediators) but also attitudinal and behavioral changes through which PG influences consumer behavior. Moreover, by centering youth consumers in the online ESG advertising context, the research addresses a relevant yet under-explored gap—providing real-world practice to inform marketers, regulators, and sustainability communicators to create more transparent, credible, and effective ESG campaigns.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

This study utilized a perceptual and behaviorally oriented method with self-reported measures to access evidence of internal psychological events like skepticism and persuasion knowledge. Subjective by definition, in the consumer psychology and advertising literature, self-reports are frequently used when measuring attitudinal and cognitive variables (Das et al. 2025; Fella and Bausa 2024; Fang 2024). All the scales were adaptations from well-established previous scales, and methodological controls (screening, pilot testing, anonymity) were established to minimize social desirability and response bias (Zhao et al. 2025; Zou et al. 2024). Self-report data provide insight into rich consumer judgments and are appropriate to model theorized psychological processes in early-stage exploratory research.

3.2. Data Collection and Sampling

The research focused on young adult Greek consumers between 18 and 35 years, who are late Gen Z as well as early millennials. The age category was chosen because this group has higher digital usage, higher levels of internet advertisement exposure, as well as environmental, social, and governance (ESG) concern sensitivity. Prior work had focused on the applicability of younger age brackets to green marketing, with social media engagement among millennials previously being said to be associated with greater green purchasing intentions and Gen Z consumers posting about sustainability more often, influencing their own buying behavior in turn. Working with Greek youth ensured a culturally comparable sample, eliminating cross-national differences in greenwashing perceptions (Rahman et al. 2022; Sandelowski 2000). For example, past research followed nation-based responses to ESG scandals like the Volkswagen emissions scandal. By focusing on a single national setting, the research bypassed cultural controls and laid the groundwork for future cross-country comparisons (Spector 2019; Stratton 2021).

Subjects were potential participants if they were between 18 and 35 years old, permanent Greek residents, and familiar with the Greek language since the questionnaire was presented in Greek. The second factor for inclusion was whether participants were familiar with digital learning or shopping websites (e.g., Coursera, YouTube Edu, Amazon, SHEIN) that present ESG-related ads. This was captured in a screen question about whether respondents had seen ads for the social or environmental causes of a company on social media or apps in the past six months. Those who said they did not know were excluded so that the sample would be representative of respondents who could provide useful insight into the effectiveness of digital ads marked with ESG. Age eligibility was implemented at survey entrance. The initial question was a numerical age screener with Google Forms validation (accepted range: 18–35). Answers outside of this range were automatically directed to a thank-you/exit page (“Go to section based on answer”) and could not continue. Participants also attested to being ≥18 at consent. In data cleaning, we re-checked age and eliminated any records with missing or inconsistent values; there were no cases outside 18–35 left in the analytic dataset. Recruitment channels (university mailing lists, student/alumni associations, and youth-oriented communities) also limited the target age range.

Notably, the survey did not entail presentation to any particular ESG-labeled advertisement under controlled conditions. Instead, participants were requested to provide answers based on past experience in viewing online ads with environmental or social responsibility messages (Zhao et al. 2025; Zou et al. 2024). The reason behind this approach was to receive naturalistic cognitive and affective responses from consumers and actual digital experiences and not to response statements towards artificial or decontextualized advertisement material. By basing the research on participants’ real-world exposure to digital media, we were trying to maximize ecological validity and simulate natural processing of ESG messages as naturally happens on platforms like social media websites, e-learning websites, or e-commerce mobile applications (Causevic et al. 2022; Díaz et al. 2024; He et al. 2023). To further enhance the responsiveness of the data, a screen question was provided to ensure that respondents with recent experience with ESG-themed advertising in the previous half-year were only allowed to respond to the survey. This screening guaranteed that the respondents had the requisite recall and exposure in order to respond with useful insight into the psychological and persuasive process that was activated through ESG messaging on the web.

A non-probability sampling strategy was used, integrating purposive and snowball sampling (Vehovar et al. 2016; Taherdoost 2016). Given the age-determined and behavioral nature of the study, random sampling of the wider population was not feasible. Participants were recruited purposefully from networks in which the target type was most likely to be located. Initial contact was made through university mailing lists, departmental alumni websites, and social network sites for sustainability, e-learning, or youth engagement. Greek university students aged between 18 to 35 years old were a convenient and available subgroup since they were digitally literate and used EdTech and e-commerce websites regularly. The survey general link was shared on Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn through messages specifically designed to connect with young Greek adults. Snowball sampling was employed to provide coverage beyond students to young adults employed or unemployed by inviting participation to pass the survey to friends. While precluding generalizability, this method of sampling was satisfactory for theory tests of structural relationships among psychological and behavioral constructs. Various attempts were employed in trying to provide diversity by gender, academic background, and geography. It was anonymous and voluntary. To maximize response rates, the gift voucher raffle was made available as an optional incentive in keeping with competent research ethics.

Data collection was conducted via an automated web-based questionnaire using Google Forms. The choice of this medium was due to it being available, user-friendly, and in a position to provide anonymity through not asking for personal identifiers. The questionnaire was created in Greek, and for those measures created in English, a strict forward–backward translation was utilized. The items were rendered into Greek by two bilingual experts, and the content was back-translated into English by an independent expert to check for equivalence. Inconsistencies were settled through discussion to ensure linguistic accuracy and conceptual fidelity. The translated survey instrument was pilot-tested on 10 participants from the target population for instructional clarity, item interpretability, and mobile phone compatibility. Reconfigurements to improve usability and language flow were undertaken on the basis of pilot feedback.

A total of 690 responses were gathered collectively, hoping to obtain a minimum of 300 usable cases. The sample size was calculated as required for structural equation modeling (SEM) statistical power. A minimum of 300 cases was suggested by the earlier literature to ensure stable estimation of SEM parameters and a 10:1 case-to-estimated-parameter or -indicator ratio (Van Zyl and Ten Klooster 2022; Schermelleh-Engel et al. 2003; Memon et al. 2020). The prior model contained about 6 observed variables and 23 estimated parameters. After deleting incomplete and poor-quality responses (missing response, straight-lining), there were 690 valid responses left, which were in the acceptable range to conduct SEM. Sample size was adequately powered to detect medium effect sizes, as well as for testing mediation and moderation hypotheses (Wagner and Grimm 2023; Hair et al. 2021).

3.3. Measurement Scales

The final survey used validated multi-item scales that matched each of the latent variables in the conceptual model. Perceived greenwashing was assessed through five items by Nguyen et al. (2019), addressing participants’ perceptions regarding overstated or deceptive ESG statements, including items such “This brand exaggerates its environmental claims.” Advertising skepticism was assessed with a 3-item scale adaptation of skepticism scale (Obermiller and Spangenberg 1998). Digital ad literacy and persuasion knowledge were operationalized and tested with items taken from Rozendaal et al. (2016), respectively, and source credibility was assessed with five items taken from Nguyen et al. (2019), with items such as “The source appears to be knowledgeable about environmental and social issues” and “I believe the source has good intentions in promoting this content,” for example. Purchase intention was assessed with four items from Nguyen et al. (2019), adapted to the ESG context. All the items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The utilization of validated instruments provided content validity and allowed for comparisons with other similar studies on green advertising and electronic persuasion. Items were translated to Greek via forward–backward translation and piloted for clarity. The full list of items is presented in Table A1 (Appendix A).

3.4. Sample Profile

A total of 690 participants completed the survey (Table 1). The sample consisted of 51.6% males (n = 356) and 48.4% females (n = 334). Participants were primarily aged 21–25 (30.9%) and 26–30 (30.0%), with smaller groups aged 18–20 (14.5%) and 31–35 (24.6%). Regarding educational attainment, 32.5% of respondents were currently enrolled in an undergraduate program, 28.7% held a bachelor’s degree, 23.9% had completed a master’s degree or higher, and 14.9% had a high school diploma. In terms of exposure to digital platforms, nearly half of the sample (47.7%) reported using such platforms daily, followed by 17.7% a few times per week, and 14.9% who reported never using them. Participants were also asked about their ad-avoidance behavior toward ESG-related advertisements. While 27.1% indicated they never skip such ads, 21.6% reported always skipping them, with intermediate frequencies reported by others (16.8% often, 14.8% sometimes, 19.7% rarely). Notably, 30.0% of participants selected “I’m not sure,” suggesting a degree of ambiguity or inattentiveness toward such advertising. Regarding influencer trust, 29.1% of participants said they follow ESG-promoting influencers but do not fully trust their claims, while 25.9% do not follow such creators at all, and only 14.9% reported following and trusting them. In terms of familiarity with ESG topics, the majority of the participants expressed low levels of familiarity, either having no knowledge at all (30.1%) or very low knowledge (20.4%). These findings offer a detailed demographic and behavioral profile of young Greek adults (18–35) regarding their exposure to and engagement with ESG-labeled digital content. The diversity in platform usage, ad-avoidance tendencies, and influencer trust levels highlights the variability in how this audience engages with persuasive ESG messaging online.

Table 1.

Sample profile.

4. Data Analysis and Results

The structural analysis in the current research was obtained via structural equation modeling (SEM) in the SmartPLS 4 software package (Version 4.1.1.4). Proceeded as per the recommendations of Nitzl et al. (2016), SEM—more variance-based—is widely regarded as a good analytical tool for management and social science research. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used because it has the ability to estimate sophisticated causal relationships by maximizing endogenous latent variables’ explained variance (Cheah et al. 2023; Hair et al. 2006). Multi-group analysis (MGA) was also employed for subgroup differences analysis, which allows contextual differences, at times unknowable by using typical regression techniques, to be identified (Cheah et al. 2023; Hair et al. 2006). The estimation process followed methodological guidelines of Wong (2013), for precise calculation of path coefficients, standard errors, and reliability estimates. Indicator reliability for the reflective measurement model was defined by outer loadings greater than a 0.70 threshold in order to be in reasonable correlation with their own latent constructs.

4.1. Common Method Bias (CMB)

In order to provide evidence of the reliability and validity of the findings, common method bias (CMB) was examined according to the methodological procedure suggested by (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Harman’s single-factor test was utilized in order to determine if a single latent factor explained most of the variance in the data. The unrotated principal component analysis found that the largest factor explained 33.863% of the overall variance, which was far from the suggested 50% value. Although CMB was not a significant threat in this study, its assessment contributes to the robustness of the analysis by avoiding potential biases and enhancing the validity of observed relationships among constructs (Podsakoff et al. 2003, 2012).

4.2. Measurement Model

The first step of the PLS–SEM procedure is measurement model evaluation, where all the constructs are measured in terms of reflective indicators. Based on the recommendations of Hair et al. (2021), this is performed by ensuring composite reliability, indicator reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Indicator reliability, as defined by Vinzi et al. (2010), is the degree to which the variation in observed variables is captured by the latent construct it represents, usually quantifiable through outer loadings. Loadings of 0.70 or greater are commonly regarded as adequate, according to the criteria of Wong (2013), and Chin (2009). Yet, Vinzi et al. (2010), also admit that in social science research there may be indicators with less than this threshold. Under such conditions, low-loading indicators must be assessed for their contribution to composite reliability and convergent validity prior to their elimination. Hair et al. (2011), state that indicators with loadings of 0.40 to 0.70 can be eliminated only if their removal would significantly enhance composite reliability or the average variance extracted (AVE). According to these guidelines, one of the indicators (ADL5) with a loading of below 0.500 was removed from the model, as shown in Table 2, according to the optimization criteria of Gefen and Straub (2005).

Table 2.

Factor loading reliability and convergent validity.

Reliability in the current study was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, rho_A, and composite reliability. As suggested by Wasko et al. (Wasko and Faraj 2005), scores above the cut-off point of 0.70 were achieved with constructs like PG, ADL, SC, PK, AS, and PI, while the other constructs also showed moderate-to-high internal consistency, in line with evidence from the previous literature (Hair et al. 2021, 2011, 2016). The rho_A coefficient, theoretically placed between Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability, also exceeded the 0.70 cut-off for most constructs, thus supporting the reliability findings presented by Sarstedt et al. (2021), and Henseler et al. (2015).

Convergent validity was established, with the average variance extracted (AVE) for all but a few constructs above the cut-off threshold of 0.50 recommended by Fornell and Larcker (1981). Composite reliability was accepted where the AVE was marginally less than 0.50, given that composite reliability was above 0.60, which is also acceptable according to Fornell and Larcker (1981). Discriminant validity was initially checked using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, where the square root of AVE of every construct exceeded its correlations with the other constructs. Additional confirmation was also achieved using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT), as proposed by Henseler et al. (2015), where all HTMT values were below the conservative threshold value of 0.85. The findings are shown in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

HTMT ratio.

Table 4.

Fornell and Larcker criterion.

4.3. Structural Model

Structural model was verified based on R2 and Q2 and the significance of the path coefficients, as suggested by Hair et al. (2021). The R2 values reported were good with respect to the variance explained: 0.465 for purchase intention, 0.461 for advertising skepticism, and 0.447 for persuasion knowledge. Further, predictive relevance (Q2) values also contained moderate-to-high predictability, with scores of 0.455 for advertising skepticism, 0.409 for purchase intention, and 0.440 for persuasion knowledge.

To further examine the structural model, hypothesis testing was performed to evaluate the statistical significance of the associations between constructs. Path coefficients were estimated using a bootstrapping technique, as suggested by Hair et al. (2016). Mediation effects were tested using a bias-corrected one-tailed bootstrapping approach with 10,000 resamples, as proposed by Preacher and Hayes (2008), and Streukens and Leroi-Werelds (2016). These are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Hypotheses testing.

All five direct hypotheses (H1–H4b) were confirmed, showing statistically significant relationships between the independent and mediating variables and the dependent variable (purchase intention). Perceived greenwashing (PG), in particular, was shown to be significantly positively related to purchase intention (β = 0.151, t = 4.302, p < 0.001), confirming H1. This implies that even where greenwashing has been identified, it is not necessarily going to eliminate behavioral intention, perhaps because it impacts other variables such as ad literacy or relevance perception. Digital advertising literacy (DAL) was significantly correlated with purchase intention (β = 0.261, t = 5.637, p < 0.001), which confirms H2. This would mean that people who are more competent in critical reading of online advertisements possess a higher purchase intention, possibly because there are higher scrutiny levels involved in judging ESG claims. Source credibility (SC) also played an important role in purchase intention (β = 0.189, t = 5.521, p < 0.001), in support of H3. This highlights the significant role of perceived trustworthiness of the ad source—i.e., platforms, brands, or influencers—in affecting persuasive effectiveness. Both cognitive–affective mediators had persuasion knowledge (PK) significantly related to purchase intention (β = 0.109, t = 2.806, p = 0.003), validating H4a. This shows that awareness of the persuasive intention will not always discourage consumers but can assist them to read and assess messages more critically, sometimes increasing behavioral intention when messages are perceived as credible. Lastly, advertising skepticism (AS) had the greatest direct impact on purchase intention (β = 0.285, t = 7.208, p < 0.001), affirming H4b. Such an outcome means that greater skepticism, far from being seen as undesirable, may even create stronger cognitive processing of ad copy, leading to more stable attitudinal responses—either negative or, paradoxically, reinforcing intention if skepticism is overcome.

These direct impacts validate the theoretical applicability of persuasion knowledge and skepticism as cognitive filters that young consumers use to make sense of ESG advertising. All pathways were significant in the predicted direction and illustrate the predictive ability of the model’s key constructs in predicting purchase intention.

4.4. Mediation Analysis

Mediation effects were examined to identify if persuasion knowledge (PK) and advertising skepticism (AS) mediate the indirect relationships among the independent variables (perceived greenwashing, digital advertising literacy, and source credibility) and the dependent variable (purchase intention). The indirect effects were measured via bias-corrected bootstrapping with 10,000 resamples. The standardized coefficients (β), standard errors (SD), t-statistics, and significance levels (p-values) for all mediation paths are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Mediation analysis.

Beginning with perceived greenwashing (PG), testing indicated a strong indirect effect on PI through PK (H5a: β = 0.013, SE = 0.005, t = 2.618, p = 0.004), and indirectly via AS (H5b: β = 0.057, SE = 0.012, t = 4.606, p < 0.001). Both indirect effects were positive, as was PG’s direct effect on PI (β = 0.151, p < 0.001), which indicates complementary mediation. This implies that greenwashing perception among participants partly mediates purchase intention as well as recognition of persuasion tactic and skepticism about advertising—without obviating PG’s direct effect.

For digital advertising literacy (DAL), there was significant mediation through PK (H6a: β = 0.052, SE = 0.018, t = 2.801, p = 0.003) and through AS (H6b: β = 0.167, SE = 0.023, t = 7.134, p < 0.001). The direct association between DAL and PI was also positive and significant (β = 0.261, p < 0.001), thus establishing complementary partial mediation. This would mean that higher digital advertising literacy increases both cognitive resistance (through PK) and affective resistance (through AS), which in turn shape stronger consumer purchase intention—or even cause prudent discrimination when receiving ESG messages.

With regard to source credibility (SC), the model also facilitated strong indirect effects to PI through both PK (H7a: β = 0.027, SE = 0.011, t = 2.451, p = 0.007) and AS (H7b: β = 0.023, SE = 0.012, t = 1.951, p = 0.026). Since the direct effect of SC on PI was still significant and positive (β = 0.189, p < 0.001), the above findings also indicate complementary mediation. This implies that the source of a digital ESG message is not just positively affecting purchase intention directly but also indirectly by affecting the extent to which the message appears to be effective and how critically it is considered.

In summary, all six indirect effects (H5a–H7b) were significant in a directional pattern consistent with their respective direct effects. Therefore, the mediating functions of persuasion knowledge and advertising skepticism are established to be complementary rather than substitutive to the direct effects of greenwashing perceptions, digital literacy, and source credibility on behavioral intentions. The evidence is supportive of a dual-process model of digital persuasion: central (cognitive) as well as peripheral (skeptical or affective) processes are engaged when people react to ESG-related digital communication.

4.5. Muti-Group Analysis (MGA)

To analyze possible moderation effects across the structural model, a sequence of multi-group analyses (MGAs) was executed with SmartPLS. Subgroup differences were analyzed by gender, age, familiarity with ESG, trust towards ESG influencers, frequency of ad-skipping, and education level. Statistically significant differences only (p < 0.05) are listed below (Table 7).

Table 7.

Significant MGA results with group comparisons.

Gender differences were revealed particularly: men were more positively affected by digital ad literacy (DAL) and source credibility (SC) on building purchase intention (PI), whereas females experienced greater negative impacts of perceived greenwashing (PG) and persuasion knowledge (PK) on PI, as well as greater skepticism (AS). The findings indicate gender differentiation in digital persuasion processing. Age variation indicated younger subjects (18–20) to be more influenced by DAL, SC, and PK in building AS and PI, with older respondents (31–35) having higher SC → PK relationships. The trend verifies developmental differences in source evaluation processing and persuasion. Subjects with lower ESG familiarity were inclined to have a higher negative influence on PI through AS and PK, suggesting greater resistance. By contrast, strongly ESG-aware respondents responded more favorably to SC and DAL, thus pointing towards more thoughtful patterns of choice-making. The main routes were also moderated by trust in ESG influencers. Participants with high trust were more attracted to SC and DAL, whereas low-trust participants were more responsive toward PG, accompanied by greater skepticism and reactance. Ad-skipping behavior was related to more negative effects of AS and PK on PI, particularly for high skippers, while SC was a robust positive predictor in all such subgroups. These findings indicate persuasion avoidance and ad literacy variation. Level of education also moderated effects attributed to persuasion awareness and credibility. More highly educated respondents (Bachelor’s or Master’s) exhibited superior DAL and SC effects, which indicate more skilled processing of advertisement cues.

These results substantiate the hypothesis that ESG advertising’s impact is mediated by salient demographic, cognitive, and behavioral variables, influencing how various subgroups process, reject, or accept persuasive messages.

5. Discussion

The outcome of the structural equation model provides insightful information with regard to young consumers’ processing and reaction to ESG-labeled internet ads. All direct hypotheses (H1–H4b) were confirmed, demonstrating suitable and theoretically sound relationships between cognitive–affective processes and purchasing intention (PI) in an environment of online sustainability messages. The findings provide richness to the pool of existing research on greenwashing, persuasion knowledge, and Gen Z digital activity, as well as some surprising nuances.

5.1. Direct Relationships: Interpreting the Path Effects

Perceived greenwashing (PG) positively influenced purchase intention (β = 0.151, p < 0.001), confirming H1 but contradicting some early expectations. Greenwashing is typically supposed to be monotonically negative for brand evaluation and behavioral outcomes, with the current literature demonstrating negative impacts on trust, satisfaction, and purchase willingness (Raghunandan and Rajgopal 2022; Rotman and David-Pennington 2024; Stromberg and Bali Swain 2024). Yet the findings of this study reveal that even when consumers suspect ESG content to be potentially misleading, this does not inevitably annihilate behavioral intention. The reason may be that greenwashing detection may trigger other cognitive processes—critical analysis, relevance assessment, or moral engagement—that reconceptualize the message without cancelling its persuasive appeal. This finding is consistent with the paradox demonstrated in (Mladenovic et al. 2024), in which low-credibility ESG signals remained persuasive under certain contextual cues.

Digital advertising literacy (DAL) was positively related to purchase intention (β = 0.261, p < 0.001), confirming H2. This suggests that increased critical sensitivity toward digital persuasive tactics does not discourage, but rather reinforces, behavioral intent. This finding concurs with Persuasion Knowledge Model and newer evidence by Fella and Bausa, 2024, that consumers who are media-literate, particularly Gen Z, utilize literacy as a means to cope with persuasive communication more effectively, as opposed to avoiding it altogether. DAL can thus be a self-confidence device, allowing users to critically but constructively analyze ESG statements (Díaz et al. 2024; Cinceoglu and Strauß 2025). This is also connected to the theoretical value of incorporating DAL into models of online persuasion, particularly in the context of environmental communication.

The effect of source credibility (SC) on purchase intention (β = 0.189, p < 0.001) also aligns with the Elaboration Likelihood Model, which places credibility at the center as a key peripheral cue in persuasion. This also aligns with more contemporary research by Higueras-Castillo et al. (2024), and Crapa et al. (2024), where those micro-communicators and influencers who were perceived as authentic were found to be more engaging. With skepticism and saturation dominating the world of advertising online, communicator–recipient trust is an important success determinant of persuasion. With Gen Z, for instance, source attributes including expertise, transparency, and moral congruence can make up for otherwise failing content or context (Raghunandan and Rajgopal 2022; Palmieri et al. 2025).

Persuasion knowledge (PK) was also positively correlated with purchase intention (β = 0.109, p = 0.003), supporting H4a. This provides a more nuanced understanding of PK’s contribution to advertising effectiveness. While previous versions of the PKM implied greater persuasion knowledge as a vehicle to counteract susceptibility to marketing (e.g., by triggering resistance), newer evidence indicates that PK facilitates more sophisticated responses—particularly among skeptical young consumers. For instance, Bertucci Lima’s model is focused on the extent to which PK, in conjunction with emotionally congruent framing and credible sources, can enable rather than hinder persuasion. In this regard, the capacity to discern persuasive intent may have enabled participants to form better judgments regarding ESG ads, effectively cementing rather than dismissing behavioral intention (Díaz et al. 2024; Rotman and David-Pennington 2024; Stromberg and Bali Swain 2024).

Notably, advertising skepticism (AS) most strongly positively directly affected purchase intention (β = 0.285, p < 0.001), hence empirically confirming H4b and posing a theoretical paradox. Skepticism is often thought of as a barrier to persuasion, yet here seems to be positively linked with purchasing intention. One way of interpreting this is that skepticism, instead of being a signal of rejection, is elevated cognitive performance. This aligns with research by Huang et al. (2024), and Chwialkowska et al. (2024), whereby skepticism was found to drive closer questioning of message authenticity, especially when consumers are faced with trite or cliched ESG appeals. For Gen Z consumers, who share the collective moniker of “critical believers,” skepticism can be less of a barrier and more of a filter—through which they might test the message before adopting it. This route also represents a “suspicion–resolve” process: when suspicious consumers are confident that a message meets their authenticity standards, they can reward it with stronger behavioral intent (Akram et al. 2024; Chwialkowska et al. 2024).

Collectively, these direct effects corroborate the theoretical hypothesis that online persuasion in ESG advertising is not a content of message, but an interpretive dynamic shaped by knowledge, trust, emotional skepticism, and media literacy. The model confirms the validity of frameworks such as PKM and ELM, but conjectures that with communications to Gen Z through ESG, linear assumptions such as “more skepticism equals less persuasion” are no longer necessary. Rather, the interplay of psychological resilience, digital literacy, and emotional engagement creates a more dynamic environment of persuasion—where greenwashing does not necessarily rebound, and skepticism can be a strength rather than a liability.

5.2. Mediation Analysis: The Role of Persuasion Knowledge and Advertising Skepticism

Mediation analysis provides us with interesting insights into the role of perceived greenwashing (PG), digital advertising literacy (DAL), and source credibility (SC) influencing consumer purchase intentions (PI) in ESG-labeled digital advertisement. More precisely, the current study tests the mediating functions of persuasion knowledge (PK) and advertising skepticism (AS)—two of the most basic cognitive and affective processing constructs of persuasive messages. All six of the indirect effects hypothesized (H5a–H7b) were significant, indicating complementary partial mediation in each instance. This is consistent with the idea that both central and peripheral processing pathways are operating at the same time, as predicted by dual-process theories of persuasion like the Elaboration Likelihood Model and extensions of the Persuasion Knowledge Model.

Beginning with perceived greenwashing, both pathways, PG → PK → PI (H5a) and PG → AS → PI (H5b), were positive and significant. This indicates that even though greenwashing has a tendency to induce skepticism and critical thinking, these beliefs perhaps may not always deter behavioral intention. Instead, critical sensitivity (through PK) and affective sensitivity (through AS) can turn suspicion into discriminative consideration, particularly with the addition of other items of coherent evidence like credible source information or emotional appeal. This is consistent with new research that shows skepticism about ESG communication does not necessarily equal rejection (Akram et al. 2024; Borah et al. 2024; Chwialkowska et al. 2024). Instead, consumers—particularly Gen Z—will retain intention to interact with sustainable products if they are empowered to be able to critically examine messages.

Digital advertising literacy showed even more powerful indirect effects via both PK (H6a: β = 0.052) and AS (H6b: β = 0.167), indicating that literate consumers think deeply about persuasive message content, identifying persuasive tactics and emotionally regulating their reactions. DAL seems to be a dormant asset that triggers both cognitive defenses (e.g., decoding persuasion attempts) and affective filters (e.g., regulating trust and relevance). This double mediation is important theoretically: it guarantees the position of DAL not merely as a protective shield, but as an enabler of interaction and efficient decision-making in complicated digital contexts. It also develops on previous research demanding an active concept of ad literacy—one that is enabling rather than inoculating (Fella and Bausa 2024; Nguyen-Viet and Thanh Tran 2024; Nguyen-Viet et al. 2024).

Source credibility also had an influence indirectly through PK (H7a) and AS (H7b), complementing its direct positive influence on PI. The finding suggests that credible sources do not only persuade directly (by increasing trust) but that they influence the interpretive environment in which the consumer is evaluating message intention and genuineness. Credibility essentially appears to dampen resistance during processing of potentially skeptical ESG appeals, but modulates the efficacy of PK and AS rather than entirely preventing them from being effective.

Together, the mediation findings are in line with the simultaneous co-activation of affective and cognitive resistance processes to digital ESG messages. In contradistinction to serving as inhibitory blocks to persuasion, PK and AS operate as evaluative filters capable of enhancing message processing and generating more resistant or goal-directed behavioral intentions. This challenges the conventional assumption that resistance indicators—such as skepticism or persuasion knowledge—are inherently detrimental to persuasive outcomes.

5.3. Multi-Group Analysis (MGA): Moderation by Demographics and Contextual Factors

The multi-group analysis (MGA) yielded important findings on the contribution of demographic and contextual factors towards shaping the structural relationships in ESG-labeled online ads. Variance was present across gender, age, familiarity with ESG, trust in ESG endorsers, attitudes on skipping ads, and educational level, highlighting the importance of differentiated digital persuasion methods depending on the segmentation of the audience.