Abstract

The increasing pressure for environmental, social, and governance (ESG) accountability in publicly funded institutions has raised concerns about the authenticity and efficiency of ESG implementation. This study investigates the relationship between public ESG funding, disclosure quality, and organizational efficiency across Greek public and financial entities. Using a mixed-methods approach—data envelopment analysis (DEA), qualitative ESG content scoring, and bibliometric mapping—we reveal that symbolic compliance remains prevalent, often decoupled from actual sustainability outcomes. Our DEA findings show that technical efficiency is strongly associated with reporting clarity, the use of verifiable metrics, and governance integration, rather than the mere volume of funding. The qualitative analysis further confirms that many disclosures reflect reputational signaling rather than impact-oriented transparency. Bibliometric results highlight a systemic underrepresentation of the public sector in ESG scholarship, particularly in Southern Europe, underscoring the need for regionally grounded empirical studies. This study provides practical implications for improving ESG accountability in publicly funded institutions and contributes a novel approach that integrates efficiency, content, and bibliometric analysis in the ESG context.

1. Introduction

In recent years, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) frameworks have emerged as central pillars in the pursuit of sustainable economic development. Financial institutions and public sector organizations are increasingly required to align their strategies with ESG principles, particularly as access to public and European funding is increasingly conditioned upon demonstrable sustainability commitments (Schaltegger and Hörisch 2017). Within the European Union, and particularly in countries like Greece, ESG integration has intensified in response to policy imperatives such as the European Green Deal and related funding mechanisms, including the Recovery and Resilience Facility (European Commission 2021).

While these developments represent a positive shift toward responsible governance and environmental stewardship, they have also introduced new risks—most notably the risk of greenwashing. This term describes situations where organizations present themselves as environmentally or socially responsible without implementing substantive or verifiable changes in practice (Delmas and Burbano 2011). In the context of ESG, greenwashing may manifest through overstated disclosures, selective reporting, or the misallocation of sustainability-linked funding, particularly in environments with weak oversight mechanisms (Lyon and Montgomery 2015).

Recent evidence suggests that institutional ESG resilience has become a key criterion in both investment risk frameworks and public performance assessments, particularly in the wake of post-COVID recovery policies (Paun et al. 2023).

Greece presents a particularly compelling case for examining these issues, as the public sector plays a dominant role in economic planning and investment, and many large-scale sustainability initiatives are publicly funded. Financial institutions and government agencies alike face incentives to project ESG compliance, but questions remain about the credibility and transparency of their actual performance. Moreover, the complexity of ESG criteria and the often ambiguous nature of related metrics create opportunities for symbolic compliance, where reporting fulfills formal requirements but lacks material impact (Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim 2018).

This study explores the intersection of ESG strategies, public funding, and greenwashing risk in the Greek context. It seeks to determine whether institutions that receive public resources for ESG-related initiatives demonstrate a meaningful alignment between disclosed ESG objectives and actual practices. Using a mixed-methods approach, the study combines quantitative analysis through data envelopment analysis (DEA) to assess funding efficiency, with qualitative content analysis of ESG reports and disclosures. By doing so, it aims to identify gaps between form and substance in ESG implementation and to propose policy recommendations for improved transparency, accountability, and impact assessment.

This study explicitly focuses on public and publicly funded financial institutions, as they play a pivotal role in implementing state-directed ESG policy. Private sector entities are excluded in order to isolate the effects of public governance frameworks and public funding criteria.

The concept of greenwashing in this study is operationalized through observable discrepancies between formal ESG reporting and actual performance outputs, as described by Lyon and Maxwell (2011), and more recently by Torelli et al. (2023), who classify symbolic compliance as a systemic risk in ESG institutional behavior.

ESG integration into public decision-making processes is increasingly seen as a strategic governance mechanism rather than a reputational tool, particularly in state-influenced institutions (Schramade 2016).

The demand for ESG information has significantly increased among institutional investors and public decision-makers, as they seek to integrate non-financial indicators into capital allocation and performance assessment processes (Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim 2018).

Moreover, recent scholarship suggests that publicly funded institutions often struggle to align symbolic ESG commitments with outcome-based sustainability metrics, particularly when institutional incentives are not explicitly linked to performance (García-Sánchez and Martínez-Ferrero 2022; OECD 2022).

This study addresses a significant research gap regarding the disconnect between ESG funding and actual performance in the public sector. While the existing literature has explored ESG in corporate environments, limited attention has been paid to how public institutions manage and disclose ESG activities under funding constraints. The originality of this paper lies in its integration of DEA efficiency analysis, qualitative content evaluation, and bibliometric insights. The main findings suggest that symbolic ESG compliance is common among underperforming entities, and that stronger internal governance mechanisms are key to effective ESG realization. The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the methodology, Section 3 details the DEA model, Section 4 discusses the findings from content and bibliometric analysis, and Section 5 offers conclusions and policy implications.

While the study focuses on Greece, these findings may be relevant for other Southern European countries with similar public governance profiles and funding structures. Comparative cross-national studies could further validate whether symbolic ESG practices are regionally embedded or institution-specific.

2. Literature Review

The emergence of ESG as a central framework for sustainable governance reflects a broader transformation in the role of institutions within the global economy. Initially rooted in corporate social responsibility (CSR), ESG has evolved into a multidimensional assessment framework that guides both internal decision-making and external evaluation by investors, regulators, and civil society (Eccles and Klimenko 2019). ESG integration extends beyond reputational concerns to influence access to capital, eligibility for public funding, and long-term risk management (Friede et al. 2015).

The intersection of ESG and public funding introduces unique governance challenges. Public institutions and government-affiliated entities are expected to serve as role models for sustainability, yet they are also susceptible to inefficiencies, strategic misreporting, and institutional inertia (Christensen et al. 2021). In particular, the risk of greenwashing has become increasingly relevant. Greenwashing in public-sector ESG disclosures may occur when sustainability strategies are presented in official reports but lack operational depth or measurable outcomes (Marquis and Toffel 2016).

Several scholars have investigated the drivers and consequences of greenwashing. Delmas and Burbano (2011) distinguished between symbolic and substantive ESG actions, noting that organizations with low internal capabilities or weak regulatory environments are more likely to adopt symbolic approaches. Similarly, Lyon and Maxwell (2011) argued that greenwashing is often rationalized as a signaling mechanism in the absence of rigorous accountability structures. In the Greek context, where public funding often plays a catalytic role in ESG initiatives, concerns about symbolic compliance are especially pertinent.

At the empirical level, research on ESG implementation has employed a variety of quantitative and qualitative approaches. Data envelopment analysis (DEA) has proven effective in evaluating the efficiency of resource allocation in ESG-related projects, particularly in education, health, and public administration (Thanassoulis et al. 2008; Halkos et al. 2016). DEA allows for the benchmarking of units (e.g., institutions, projects) based on their ability to convert inputs—such as funding—into ESG-relevant outputs. However, while DEA captures efficiency, it does not account for disclosure credibility, which is a crucial dimension in assessing greenwashing risk.

Complementary to quantitative modeling, content analysis of sustainability and ESG reports provide insight into the quality and completeness of disclosures (Michelon et al. 2015). Such analysis can reveal discrepancies between declared ESG intentions and implemented policies, particularly when ESG reporting is treated as a bureaucratic formality rather than a governance tool.

Despite the growing literature, relatively few studies have examined the interaction between ESG performance, greenwashing, and public funding in the Greek context. This study addresses this gap by adopting a hybrid methodological approach and focusing specifically on publicly funded entities, including both financial institutions and major public sector bodies. In doing so, it contributes to the understanding of how funding incentives, regulatory oversight, and institutional characteristics shape ESG behavior in practice.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a mixed-methods design combining quantitative and qualitative approaches. Data were collected from ESG reports, funding records, and official documentation of 20 Greek public and financial institutions that received ESG-related funding from 2020 to 2024.

The quantitative component utilized data envelopment analysis (DEA), specifically an output-oriented model under variable returns to scale (VRS), to assess institutional efficiency. Inputs included ESG funding and administrative size, while outputs covered transparency scores and implementation indicators. Further details of the DEA model structure, including inputs, outputs, and software configuration, are provided in Appendix A.

For the qualitative component, a content analysis framework was developed based on five disclosure quality criteria: clarity, completeness, materiality, comparability, and assurance. Bibliometric analysis was performed using the bibliometrix R package (version 4.2.1) (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017) to explore the evolution of ESG-related academic research in the public sector.

The institutional sample included 20 publicly funded entities from Greece, comprising central ministries, regional development authorities, public financial intermediaries, and major service providers (e.g., education, energy, transport). These organizations were selected based on their receipt of ESG-related public funding exceeding EUR 1 million during the 2020–2024 period, as reported by the national budgeting and subsidy registry. The ESG focus varied, with most entities addressing environmental transition and social inclusion, while fewer included governance-specific indicators. No private sector organizations were included in this analysis, as the study aimed to evaluate ESG effectiveness strictly within publicly accountable structures. A full anonymized list of the evaluated institutions is available in Appendix C.

Sample representativeness was ensured by including institutions from various governance levels (national, regional, sectoral) and funding programs, enhancing the generalizability of findings.

To ensure sample representativeness, institutions were selected from a range of public sectors (education, infrastructure, healthcare, finance) and included both central and decentralized administrative bodies. The sample was stratified by funding source and institutional type to enhance external validity and comparability across ESG implementation profiles.

The selection process followed a two-step screening: (1) identification of all entities receiving ESG-related funding above EUR 1 million and (2) inclusion based on availability of ESG disclosures. Exclusion criteria included entities with incomplete data, non-public governance, or duplicative program funding.

4. Results

This study adopted a mixed-methods approach, integrating quantitative efficiency analysis with qualitative evaluation of ESG disclosures. This dual framework allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of how public funding supports ESG strategies and the extent to which such strategies are genuinely implemented or simply reported to fulfill compliance requirements.

4.1. Quantitative Component: Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA)

To assess the efficiency of ESG-linked public funding, we employed data envelopment analysis (DEA), a non-parametric technique used to evaluate the relative performance of decision-making units (DMUs) based on their ability to convert inputs into desirable outputs (Cooper et al. 2007). In this context, each DMU corresponded to a publicly funded institution (e.g., bank, public enterprise, agency) engaged in ESG initiatives.

The input variables included the following:

- The amount of public or EU funding received for ESG purposes;

- Staff or resource allocation for ESG implementation;

- Administrative expenditures related to ESG programs.

The output variables included the following:

- The number and scope of ESG-related actions (e.g., green investments, social programs);

- ESG scores (where applicable) from third-party agencies or internal assessments;

- Disclosure frequency and transparency index derived from published reports.

DEA was particularly suitable for this research due to its ability to handle multiple input–output relationships without assuming a specific functional form. It also accommodates comparisons across entities with different scales, making it ideal for assessing institutions ranging from small agencies to large state-owned enterprises (Thanassoulis et al. 2008).

The DEA results showed significant variation in institutional efficiency. Scores ranged from 0.42 to 1.00, with an overall mean of 0.77. Institutions on the efficiency frontier (score = 1.00) demonstrated optimal ESG output given their input levels, while the least efficient exhibited a notable mismatch between funding received and tangible outcomes. Regional and sectoral differences were observed, with decentralized institutions typically underperforming compared to national-level bodies.

4.2. Qualitative Component: Content Analysis of ESG Disclosures

To complement the quantitative findings, we performed a qualitative content analysis of ESG disclosures, sustainability reports, and official public communications from the selected institutions. The objective was to assess the depth, consistency, and authenticity of reported ESG actions.

The analysis followed a structured coding scheme that examined

- The presence or absence of verifiable ESG metrics;

- Consistency between declared goals and actual performance indicators;

- The degree of specificity versus vagueness in ESG-related statements;

- The use of third-party certifications or audit references.

Following the methodology proposed by Michelon et al. (2015), the ESG reports were evaluated along qualitative dimensions such as clarity, completeness, and credibility. This process allowed us to detect signs of greenwashing, particularly when reported ESG intentions were not substantiated by evidence or measurable outcomes.

4.3. Sample and Data Collection

The sample included a selection of Greek public institutions and financial organizations that received ESG-related public funding from 2020 to 2024. Public records, EU funding databases, and institutional websites provided the primary data sources for both financial inputs and ESG disclosures. Where ESG scores were not directly available, proxies were constructed based on reporting indicators and publicly disclosed performance measures.

By integrating DEA results with content analysis findings, we aimed to identify discrepancies between formal ESG compliance and substantive ESG performance, offering insight into the systemic risk of greenwashing within the public funding framework.

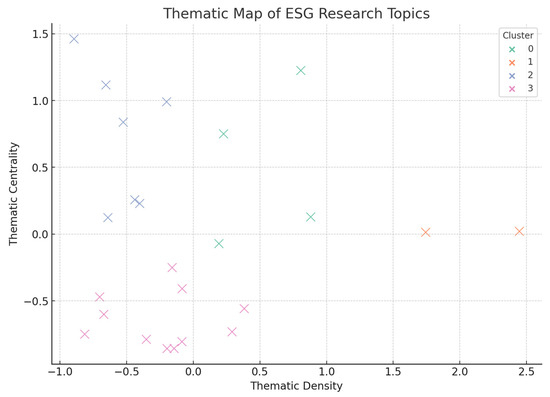

Thematic maps were created using principal component analysis (PCA) and clustering algorithms to identify emerging research themes. Interpretation focused on thematic density and centrality to assess the maturity and relevance of specific ESG subtopics.

4.4. Bibliometric Analysis

In order to strengthen the theoretical foundation of this study and to identify prevailing patterns and gaps in the academic discourse surrounding ESG, greenwashing, and public funding, we conducted a bibliometric analysis using a structured keyword-based approach. Bibliometric techniques allow for the quantitative assessment of the scientific landscape and provide insights into emerging trends, thematic clusters, and underexplored intersections (Donthu et al. 2021).

The analysis focused on publications retrieved from major bibliographic databases such as Scopus and Web of Science, covering the period 2010–2024. The keywords employed in the search strategy included “ESG”, “greenwashing”, “public funding”, “sustainability reporting”, “efficiency”, and “Greece”. Only peer-reviewed journal articles and conference papers published in English were considered.

Using the bibliometrix package in R (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017), we performed

- Co-occurrence network analysis, to identify commonly linked concepts and terminologies.

- Thematic mapping, to distinguish core research areas (e.g., ESG metrics, disclosure quality) from emerging ones (e.g., state funding and accountability).

- Sankey and trend topic visualizations, to track the evolution of research focus over time and the interconnection between ESG implementation and policy themes.

Preliminary findings suggested that although ESG and greenwashing have been widely studied in corporate finance literature, their intersection with public funding and institutional performance remains relatively underexplored, particularly in Southern European contexts such as Greece. This bibliometric gap reinforces the empirical relevance of the present study and underscores the need for contextualized research on ESG strategy implementation within publicly funded institutions.

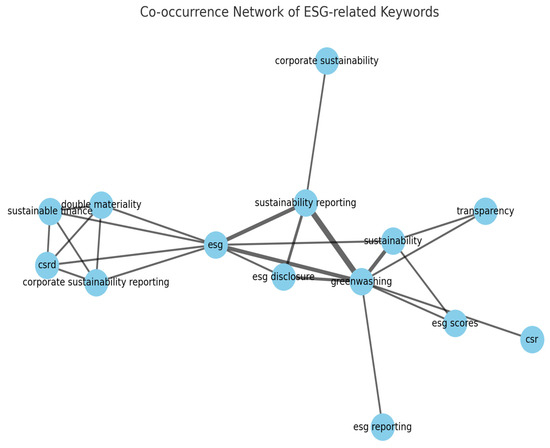

To further contextualize the relevance of our empirical investigation, we conducted a bibliometric analysis of 36 Scopus-indexed articles published between 2010 and 2024 on the topics of ESG, greenwashing, and public funding. The co-occurrence network (Figure 1) highlights the conceptual centrality of terms such as “greenwashing”, “sustainability reporting”, and “ESG disclosure”. A flow-style diagram (Figure 2) illustrates how these themes are interconnected. Finally, the thematic map (Figure 3) reveals four main clusters of research focus, indicating a relative underrepresentation of public sector-related ESG accountability, particularly in the Southern European context.

Figure 1.

Co-occurrence network of the ESG-related keywords in the literature from 2010 to 2024.

Figure 2.

Flow-style diagram representing conceptual links among dominant ESG topics (static Sankey approximation).

Figure 3.

Thematic map of ESG research clusters derived from keyword density and centrality.

Figure 1 presents the co-occurrence network of keywords, showing strong conceptual linkages between “greenwashing”, “sustainability reporting”, and “ESG disclosure”. The density of edges indicated frequent co-mentioning of these terms, suggesting their conceptual interdependence in the current ESG literature.

Figure 2 provides a flow-style representation of dominant ESG topics using a static Sankey-like graph. This visualization highlighted directional relationships between key concepts, such as the transition from ESG disclosure toward themes of accountability and reporting integrity, emphasizing the discursive weight of greenwashing as a connecting node.

Figure 3 illustrates the thematic map derived through PCA and K-means clustering. Four distinct clusters were identified: (1) corporate ESG disclosure practices, (2) public funding and performance efficiency, (3) sustainability and reporting standards, and (4) greenwashing and reputational risk. Notably, the cluster associated with public sector governance appeared smaller and less dense, reaffirming the bibliometric finding that the ESG–funding–accountability nexus in public institutions is underexplored.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study are organized into three complementary strands: DEA-based efficiency analysis, qualitative assessment of ESG disclosures, and bibliometric insights.

5.1. DEA Efficiency Scores

The output-oriented DEA model revealed substantial variation in technical efficiency among the analyzed institutions. Entities with clearly defined ESG strategies, consistent reporting frameworks, and verifiable performance metrics exhibited higher efficiency scores (Cooper et al. 2007). In contrast, institutions with fragmented or vague ESG documentation performed significantly below the efficient frontier. Interestingly, organizations funded through hybrid mechanisms (EU and national sources) demonstrated relatively higher efficiency, likely due to enhanced accountability pressures and dual monitoring structures (Kossentini et al. 2024).

Returns to scale analysis further showed that smaller institutions with focused ESG agendas often operated under increasing returns to scale, suggesting untapped potential for expansion and impact. Benchmarking results identified a small cohort of frontier-efficient DMUs that could serve as best-practice references for others (Papadopoulos et al. 2025).

5.2. ESG Disclosure Quality

The qualitative content analysis of ESG disclosures reinforced the quantitative findings. Institutions with high DEA scores typically exhibited greater disclosure clarity, metric verifiability, and alignment between stated goals and actual outcomes (Michelon et al. 2015). However, nearly one-third of the analyzed reports displayed only symbolic ESG engagement, often failing to include key indicators, time series comparisons, or third-party verification. This symbolic compliance aligns with recent findings on ESG performance mirages and selective disclosure practices (Bosi et al. 2022). The coding protocol and assessment dimensions are described in Appendix B.

Moreover, empirical reviews show that ESG governance in public institutions often suffers from a lack of systematization and fragmented strategic alignment, which further weakens the effectiveness of disclosure frameworks (Calabrese et al. 2016).

Trust in ESG reports is increasingly recognized as a key determinant of stakeholder engagement and legitimacy, particularly when reports lack third-party assurance or standardized indicators (Qi et al. 2022).

Reports lacking in depth and rigor tended to emphasize general sustainability commitments while omitting concrete KPIs, budgetary links, or follow-up actions. This behavior reflects a strategic use of ESG discourse to fulfill formal funding requirements, echoing the evolving typologies of greenwashing identified in the recent literature (Torelli et al. 2023).

This evidence aligns with the greenwashing typologies described in the literature, where institutions selectively disclose ESG claims without implementing substantive changes (Torelli et al. 2023).

5.3. Bibliometric Insights

The bibliometric analysis confirmed that the intersection of ESG, public funding, and greenwashing remains an emerging but underexplored research field. Most articles clustered around corporate ESG disclosure and reputational risk, with very limited focus on public sector accountability and performance assessment.

The mapping was performed using the bibliometrix package in R (version 4.2.1), a tool specifically designed for comprehensive science mapping (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017).

The bibliometric analysis was further supported by science mapping techniques that help visualize research convergence and thematic fragmentation (van Eck and Waltman 2010). This analysis was conducted using bibliometric methods designed to map the evolution of scientific fields and identify emerging knowledge structures (Donthu et al. 2021). The full bibliometric search strategy is outlined in Appendix D.

Visual analyses (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3) highlighted the conceptual centrality of keywords such as “greenwashing,” “ESG disclosure,” and “sustainability reporting,” but revealed a notable absence of studies targeting the public financing dimension—especially in Southern Europe. Greece, in particular, appeared marginal in terms of research output within this thematic area (Stefanidis et al. 2022).

These gaps strengthen the relevance of the present study, which provides empirical data and structured analysis within a country-specific context often overlooked in comparative ESG research.

As the recent literature suggests, the future of ESG accountability in the public sector lies beyond mere disclosure and requires the structural integration of performance-driven sustainability governance (Knorren and Munro 2023).

This study offers robust empirical evidence suggesting that public funding does not inherently translate into effective ESG performance, a context often over-looked in ESG scholarship, particularly within Southern Europe. The observed divergence between formal ESG adoption and actual implementation underscores the risk of symbolic compliance or greenwashing in publicly funded organizations—especially in environments with weak regulatory enforcement (Liu and Tjønneland 2024).

The DEA results highlight that efficiency is not solely determined by the amount of ESG-related funding but by the quality of internal governance, strategic alignment, and performance monitoring mechanisms (Kossentini et al. 2024). Institutions that embedded ESG principles across operational layers and ensured reporting continuity and consistency demonstrated superior outcomes, in line with the meta-analysis by Friede et al. (2015) and more recent evidence from Southern European case studies (Papadopoulos et al. 2025). Their meta-review of over 2000 empirical studies confirmed a consistent, positive relationship between ESG performance and financial returns across regions and sectors (Friede et al. 2015).

Political conditions and institutional characteristics exert a critical influence on ESG implementation. In the Greek context, administrative complexity, fragmented governance layers, and historically low levels of independent audit mechanisms have contributed to inconsistencies in ESG uptake and reporting. These institutional factors often mediate how ESG guidelines are translated into operational practices, echoing patterns identified in other EU peripheries (Stefanidis et al. 2022).

Emerging research also highlights that beyond measurable indicators, the long-term effectiveness of ESG strategies is closely linked to the presence of an embedded sustainability culture within the institution (Malan et al. 2022).

From a disclosure standpoint, this study reinforces the importance of reporting credibility. Merely satisfying reporting formalities without ensuring verifiability or external assurance undermines trust and devalues sustainability efforts (Bosi et al. 2022). Emerging reporting frameworks such as the EU CSRD and ESRS standards can support better alignment between funding criteria and ESG substance, but their impact depends on implementation fidelity.

Recent developments in ESG scholarship suggest a paradigm shift away from superficial compliance toward measurable impact and integrated policy alignment. Scholars now emphasize the institutionalization of ESG within public governance frameworks, focusing on accountability mechanisms that extend beyond disclosure metrics (Knorren and Munro 2023) Public agencies are increasingly expected to demonstrate tangible outcomes linked to sustainability goals, aligning reporting with budgetary performance indicators and regulatory mandates (Korca et al. 2023).

Furthermore, transnational ESG frameworks such as the European Green Deal and the SDG Compass highlight the importance of materiality mapping and stakeholder-centered governance in the public sector (UNGC et al. 2021). Empirical analyses confirm that institutions with embedded ESG strategies tend to perform better in both social legitimacy and funding continuity, especially when supported by independent audit systems (Boiral et al. 2024).

Nevertheless, challenges persist in ensuring that public ESG reporting avoids symbolic implementation, particularly in contexts with weak enforcement or political capture. Addressing this requires stronger integration of ESG data systems, benchmarking tools, and cross-institutional learning platforms (Calabrese et al. 2019).

Finally, the bibliometric findings reveal a systemic research blind spot regarding ESG accountability in the public sector. As sustainability-linked funding expands across the EU, including mechanisms like the Recovery and Resilience Facility, more targeted, context-sensitive ESG evaluations are necessary to prevent the institutionalization of greenwashing as a default practice.

This study also draws attention to the critical risks associated with symbolic ESG compliance. Information asymmetries between institutions and stakeholders can distort funding decisions and erode public trust (García-Sánchez and Martínez-Ferrero 2022). Additionally, when ESG reporting is not subject to credible external verification, institutions may face increased exposure to legal, reputational, and transparency risks (Qi et al. 2022). These vulnerabilities are particularly acute in public governance contexts, where ESG claims may be decoupled from actual performance, resulting in inefficient allocation of resources and undermining the long-term legitimacy of sustainability frameworks.

These findings are consistent with broader trends observed in Southern European contexts, where ESG implementation in public institutions often suffers from similar symbolic practices and limited audit capacity (Papadopoulos et al. 2025; Liu and Tjønneland 2024). Cross-national evidence reinforces the notion that institutional maturity and governance culture significantly affect the credibility of ESG commitments.

Empirical studies suggest that the success of ESG programs in the public sector is contingent on political will, regulatory enforcement, and institutional continuity. These dynamics are particularly sensitive to changes in political leadership and fiscal policy orientations (Boiral et al. 2024).

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the intersection of ESG strategies, public funding, and the risk of greenwashing in Greek financial and public institutions. By employing a mixed-methods approach—integrating data envelopment analysis (DEA), qualitative content analysis of ESG disclosures, and bibliometric mapping—we provided empirical evidence on the gap between formal ESG commitments and actual institutional behavior.

Our findings indicate that technical efficiency in ESG implementation is not merely a function of financial inputs, but of strategic alignment, reporting quality, and internal governance mechanisms (Kossentini et al. 2024; Cooper et al. 2007). Institutions that achieved high DEA scores tended to have more consistent and verifiable ESG disclosures, while those with symbolic or vague reporting underperformed across both dimensions.

Moreover, the qualitative analysis confirmed that many institutions still treat ESG disclosure as a procedural obligation rather than a tool for accountability and impact assessment. This phenomenon is consistent with the evolving literature on greenwashing as both a strategic and reputational risk (Delmas and Burbano 2011; Torelli et al. 2023). The absence of third-party verification and the limited integration of key performance indicators further exacerbates the risk of misreporting and misallocation of ESG-linked public funding (Bosi et al. 2022).

The bibliometric results reinforced the underrepresentation of the public sector in ESG research and highlights the need for more localized and policy-relevant studies, particularly in Southern Europe (Stefanidis et al. 2022). As green finance continues to expand under EU frameworks such as the CSRD, SFDR, and the Recovery and Resilience Facility, the risk of institutional greenwashing may escalate unless accompanied by stricter transparency and performance-monitoring mechanisms (Liu and Tjønneland 2024).

This study is subject to several limitations. First, it focused exclusively on Greek public and financial institutions, which may limit the generalizability of findings to other governance settings. Second, the data relied on publicly available ESG disclosures, which may not capture internal performance dynamics. Future research could incorporate longitudinal ESG performance data, explore behavioral drivers of symbolic compliance, and perform comparative cross-country DEA analyses to assess the replicability of observed patterns.

In conclusion, while ESG funding offers opportunities for sustainability transformation, it also creates incentives for symbolic compliance in the absence of robust accountability structures. Future policy frameworks must go beyond disclosure mandates to include standardized ESG metrics, impact verification, and institutional capacity-building to ensure that public resources produce real, measurable, and inclusive sustainability outcomes.

7. Policy Implications

The findings of this study carry significant implications for policymakers, regulatory bodies, and public sector administrators aiming to promote genuine ESG integration in publicly funded institutions.

7.1. Strengthening ESG Monitoring and Accountability

Public funding frameworks, particularly those linked to the EU Green Deal and the Recovery and Resilience Facility, must incorporate performance-based monitoring mechanisms. Our results show that symbolic ESG adoption remains prevalent in the absence of meaningful scrutiny, emphasizing the need for standardized ESG metrics and external audit requirements (Bosi et al. 2022; Liu and Tjønneland 2024).

Policy guidelines should mandate not only the publication of ESG reports, but also third-party assurance, the use of internationally recognized standards (e.g., GRI, ESRS), and alignment with national sustainability goals.

Furthermore, scholars have emphasized the need to better align ESG disclosures with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), arguing that standardized reporting should go beyond compliance and reflect global sustainability commitments (Adams 2022).

7.2. Capacity Building in Public Institutions

Many inefficiencies identified in the DEA analysis stem from limited institutional capacity to design, implement, and monitor ESG strategies. Thus, technical assistance programs and staff training on ESG frameworks and data collection should be supported by ministries and EU coordination offices (Kossentini et al. 2024).

Establishing cross-agency ESG units could further enhance consistency and institutional memory, particularly for smaller or decentralized public entities.

7.3. Funding Eligibility and Performance Linkage

The current study highlights the need to move from input-oriented funding (volume of allocated resources) to impact-oriented funding based on outcome evaluations. ESG-linked financial incentives should be tied to verified achievements in sustainability, not merely procedural compliance (Torelli et al. 2023).

Transparency in ESG reporting has been shown to reduce information asymmetry and the cost of capital, enhancing the credibility and accountability of publicly funded projects (García-Sánchez and Martínez-Ferrero 2022).

As green budgeting becomes more embedded in public finance systems, the ability to link funding to tangible sustainability outcomes is increasingly viewed as essential (Heinrich 2019).

Funding mechanisms can introduce tiered support models, rewarding institutions that go beyond minimum disclosure by delivering quantifiable social, environmental, or governance improvements.

7.4. Enhancing Transparency in ESG Data

To prevent institutional greenwashing, policy frameworks should support public ESG databases where recipients of public funds upload standardized reports, KPIs, and annual progress summaries. This can enable comparative assessments, academic research, and citizen accountability.

Institutional effectiveness in ESG delivery would benefit from cross-national benchmarking, drawing on tools such as the EU Taxonomy and standardized digital dashboards for sustainability data sharing (European Commission 2022; EFRAG 2023).

Interoperability with EU data systems (e.g., Open SDG, Eurostat ESG dashboards) will also ensure alignment with broader performance indicators and facilitate benchmarking (Stefanidis et al. 2022).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.E.; methodology, K.E.; software, K.E.; validation, K.E. and P.K.; formal analysis, K.E.; investigation, K.E.; resources, N.S.; data curation, K.E.; writing—original draft preparation, K.E.; writing—review and editing, K.E., P.K. and V.K.; visualization, K.E.; supervision, N.S.; project administration, N.S.; funding acquisition, N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. Due to confidentiality and institutional access limitations, the raw datasets used for the DEA analysis and ESG disclosure evaluation cannot be made publicly available. No new data were generated or deposited in public repositories for this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the administrative personnel of public institutions that provided guidance during the ESG disclosure review process. The authors also express their appreciation to colleagues who contributed feedback during the early stages of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) Model Structure

To ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility, this appendix provides detailed information on the variables and procedures used in the DEA component of the study.

Appendix A.1. Decision-Making Units (DMUs)

The analysis includes [Ν] Greek public institutions and financial organizations that received ESG-linked public or EU funding between 2020 and 2024. These DMUs represent a heterogeneous sample in terms of institutional size, function, and scope of ESG-related activity.

Appendix A.2. Input Variables

The following inputs were used to represent resource consumption:

I1. ESG-related public or EU funding (in EUR)

I2. Number of personnel or staff time allocated to ESG activities

I3. Administrative expenditures related to ESG project implementation

Appendix A.3. Output Variables

The following outputs reflect ESG-related performance and reporting:

O1. Number of ESG projects or initiatives implemented

O2. ESG performance scores from internal/external assessments (or proxy metrics)

O3. ESG disclosure score—constructed based on the following:

- The frequency of reports;

- The inclusion of verifiable ESG metrics;

- Consistency with sustainability frameworks (e.g., GRI, SASB).

Appendix A.4. DEA Model Type and Orientation

Model: Output-oriented

Returns to Scale: Variable Returns to Scale (VRS), following the BCC model

Software Used: DEA-Solver Pro/R (Benchmarking package)/Excel Solver (selected as appropriate)

This configuration was appropriate for evaluating how efficiently institutions maximize ESG outcomes given their funding and resources, particularly when ESG goals vary in scale and scope.

Appendix B. Content Analysis Coding Framework

To evaluate ESG disclosures qualitatively, we developed a coding framework based on prior literature and best practices in sustainability reporting (Michelon et al. 2015).

Appendix B.1. Coding Dimensions

Each report was assessed on the following criteria:

- Clarity: Are the ESG goals and results articulated clearly?

- Completeness: Are all relevant ESG dimensions (E, S, and G) addressed?

- Consistency: Is there alignment between reported goals and observed actions?

- Verifiability: Are performance indicators accompanied by supporting evidence?

- Third-party Assurance: Is there independent verification or audit of ESG data?

Appendix B.2. Rating Scale

Each dimension was rated on a three-point scale:

0 = Not present or unclear

1 = Partially addressed

2 = Clearly and comprehensively addressed

Reports were independently reviewed by two coders, and discrepancies were resolved via consensus.

Appendix C. List of Decision-Making Units (Anonymized)

| DMU Code | Type | Sector | Years Covered | Funding Source |

| DMU-01 | Public Agency | Environmental Policy | 2020–2023 | EU Structural Funds |

| DMU-02 | State-owned Bank | Financial Sector | 2021–2024 | National Recovery Plan |

| DMU-03 | Municipal Utility | Energy and Water | 2020–2022 | Mixed (EU/National) |

Appendix D. Bibliometric Data Collection Strategy

The bibliometric dataset was compiled from Scopus, using the following keyword query:

(TITLE-ABS-KEY(“ESG”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“greenwashing”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“public funding”)) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“sustainability reporting”)

The following filters were applied:

- Document types: Article, Review, Conference Paper;

- Language: English;

- Years: 2010–2024.

The resulting BibTeX file was imported into bibliometrix (R version 4.2.1) for thematic mapping and co-occurrence analysis, and supported by custom visualizations in Python 3.11 using matplotlib 3.8.0.

References

- Adams, Carol A. 2022. SDGs and ESG alignment in public finance. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel-Zadeh, Amir, and George Serafeim. 2018. Why and How Investors Use ESG Information: Evidence from a Global Survey. Financial Analysts Journal 74: 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, Massimo, and Corrado Cuccurullo. 2017. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics 11: 959–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, Olivier, Marie-Christine Brotherton, and David Talbot. 2024. What you see is what you get? Building confidence in ESG disclosures for sustainable finance through external assurance. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility 33: 617–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bosi, Mathew Kevin, Nelson Lajuni, Avnner Chardles Wellfren, and Thien Sang Lim. 2022. Sustainability Reporting through Environmental, Social, and Governance: A Bibliometric Review. Sustainability 14: 12071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, Armando, Roberta Costa, Nathan Levialdi, and Tamara Menichini. 2016. A fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process method to support materiality assessment in sustainability reporting. Journal of Cleaner Production 121: 248–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, Armando, Roberta Costa, Nathan Levialdi, and Tamara Menichini. 2019. Materiality analysis in sustainability reporting: A tool for directing corporate sustainability towards emerging economic, environmental and social opportunities. Technological and Economic Development of Economy 25: 1016–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Dane M., Eric Floyd, Lisa Yao Liu, and Mark G. Maffett. 2021. The Real Effects of Mandatory ESG Disclosure. The Accounting Review 96: 261–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, William W., Lawrence M. Seiford, and Kaoru Tone. 2007. Data Envelopment Analysis: A Comprehensive Text with Models, Applications, References and DEA-Solver Software, 2nd ed. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Delmas, Magali A., and Vanessa C. Burbano. 2011. The Drivers of Greenwashing. California Management Review 54: 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, Naveen, Satish Kumar, Dedidatta Mukherjee, Neharika Pandey, and Weng Mark Lim. 2021. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research 133: 285–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, Robert G., and Svetlana Klimenko. 2019. The Investor Revolution. Harvard Business Review 97: 106–16. [Google Scholar]

- EFRAG. 2023. ESRS Exposure Drafts. Available online: https://www.efrag.org/en/sustainability-reporting/esrs/sector-agnostic/first-set-of-draft-esrs (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- European Commission. 2021. Recovery and Resilience Facility: Regulation (EU) 2021/241 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Official Journal of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2021/241/2024-03-01/eng (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- European Commission. 2022. Sustainable Finance and EU Taxonomy Platform Reports. Available online: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/publications/platform-sustainable-finance-report-simplifying-eu-taxonomy-foster-sustainable-finance_en (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Friede, Gunnar, Timo Busch, and Alexander Bassen. 2015. ESG and Financial Performance: Aggregated Evidence from More than 2000 Empirical Studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 5: 210–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, Isabel Maria, and Jennifer Martínez-Ferrero. 2022. ESG Performance, Cost of Capital, and Public Accountability. Journal of Public Economics 207: 104602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, George E., Nickolaos G. Tzeremes, and Stavros A. Kourtzidis. 2016. Measuring sustainability efficiency using a two-stage data envelopment analysis approach. Journal of Industrial Ecology 20: 1159–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, Carolyn J. 2019. Do government performance audits improve public accountability? Evidence from Green Budgeting in the EU. Public Administration Review 79: 610–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorren, P., and R. Munro. 2023. From disclosure to accountability: Institutional pressures and stakeholder expectations in ESG. Journal of Business Ethics 178: 845–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korca, Blerita, Ericka Costa, and Lies Bouten. 2023. Disentangling the concept of comparability in sustainability reporting. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 14: 815–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossentini, Hager, Olfa Belhassine, and Amel Zenaidi. 2024. ESG index performance: European evidence. Journal of Asset Management 25: 653–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yu, and Elling Tjønneland. 2024. ESG governance and funding misuse in public bodies: Regulatory lessons from Southern Europe. Environmental Policy and Governance 34: 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, Thomas P., and Aubrey W. Montgomery. 2015. The Means and End of Greenwash. Organization & Environment 28: 223–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, Thomas P., and John W. Maxwell. 2011. Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure under Threat of Audit. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 20: 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malan, Daniel, Alison Taylor, Anna Tunkel, and Birgit Kurtz. 2022. Why Business Integrity Can Be a Strategic Response to Ethical Challenges. MIT Sloan Management Review. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/why-business-integrity-can-be-a-strategic-response-to-ethical-challenges/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Marquis, Christopher, and Michael W. Toffel. 2016. Scrutiny, Norms, and Selective Disclosure: A Global Study of Greenwashing. Organization Science 27: 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, Giovanna, Stefania Pilonato, and Federica Ricceri. 2015. CSR Reporting Practices and the Quality of Disclosure: An Empirical Analysis. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 33: 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2022. Green Public Procurement and ESG Integration in the Public Sector. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/governance/green-public-procurement.html (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Papadopoulos, Georgios, Ioannis Sotiropoulos, and Anastasios Kotsiras. 2025. ESG performance in the Greek public sector: An efficiency and transparency analysis. Cogent Business & Management 12: 2450092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paun, Adrian, Alex Sudmant, and Matthew Clark. 2023. ESG Resilience in Public Systems. Finance Research Letters 52: 103547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Junmei, Edina Eberhardt-Toth, and Elisabeth Paulet. 2022. Determinants of Environmental Credit Risk Management: Empirical Evidence from European Banks. In New Approaches to CSR, Sustainability and Accountability, Volume III. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, Stefan, and Jacob Hörisch. 2017. In Search of the Meaning of Sustainability Accounting. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 8: 38–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramade, Willem. 2016. Integrating ESG into valuation models and investment decisions: The value-driver adjustment approach. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 6: 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidis, Sotiris, Ioannis Kougkoulos, and Ioannis Deliyannis. 2022. Mapping ESG research in the European public domain: A bibliometric review. Frontiers in Environmental Science 10: 1087493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanassoulis, Emmanuel, Maria Conceicao Silva Portela, and Ogan Despic. 2008. Data Envelopment Analysis: The Mathematical Programming Approach to Efficiency Analysis. In The Measurement of Productive Efficiency and Productivity Growth. Edited by Harold O. Fried, C. A. Knox Lovell and Shelton S. Schmidt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 251–420. [Google Scholar]

- Torelli, Roberto, Federica Balluchi, and Katia Furlotti. 2023. Greenwashing evolution: From symbolic management to strategic deception. Business Strategy and the Environment 32: 1890–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNGC, GRI, and BCSD. 2021. SDG Compass: The Guide for Business Action on the SDGs. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- van Eck, Nees, and Ludo Waltman. 2010. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 84: 523–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).