Gender Diverse Boardrooms and Earnings Manipulation: Does Democracy Matter?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample

3.2. Variables

3.3. Model Specification

3.4. Estimation Approach

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Data Analysis

4.2. Regression Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) GENDER | 1 | |||||||||||

| (2) IND | 0.195 *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| (3) DUALITY | 0.029 *** | −0.089 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| (4) LEVERAGE | 0.059 *** | 0.017 * | 0.024 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| (5) LNSIZE | 0.075 *** | 0.093 *** | 0.093 *** | 0.174 *** | 1 | |||||||

| (6) R&D | −0.014 | 0.114 *** | 0.016 * | −0.123 *** | −0.172 *** | 1 | ||||||

| (7) LIQUIDITY | −0.009 | −0.056 *** | 0.021 ** | −0.368 *** | −0.325 *** | 0.239 *** | 1 | |||||

| (8) GROWTH | −0.010 | 0.000 | −0.017 * | −0.046 *** | −0.070 *** | 0.042 *** | 0.027 *** | 1 | ||||

| (9) BIG4 | −0.028 *** | 0.029 *** | 0.041 *** | 0.009 | 0.103 *** | −0.008 | −0.023 *** | −0.007 | 1 | |||

| (10) ROA | 0.021 ** | −0.022 *** | 0.013 | −0.167 *** | 0.218 *** | −0.317 *** | −0.055 *** | 0.134 *** | 0.033 *** | 1 | ||

| (11) GDP | −0.015 * | 0.035 *** | −0.010 | −0.027 *** | 0.018 ** | 0.010 | −0.006 | 0.256 *** | 0.017 ** | 0.063 *** | 1 | |

| (12) DEM | 0.191 *** | 0.199 *** | −0.073 *** | −0.116 *** | −0.197 *** | 0.106 *** | 0.125 *** | 0.015 * | −0.009 | −0.084 *** | −0.002 | 1 |

| Country | Freq. | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | 218 | 1.60 |

| Belgium | 327 | 2.41 |

| Bulgaria | 3 | 0.02 |

| Cyprus | 35 | 0.26 |

| Denmark | 416 | 3.06 |

| Finland | 471 | 3.46 |

| France | 1311 | 9.64 |

| Germany | 1527 | 11.23 |

| Greece | 145 | 1.07 |

| Hungary | 60 | 0.44 |

| Iceland | 23 | 0.17 |

| Ireland | 424 | 3.12 |

| Italy | 532 | 3.91 |

| Lithuania | 4 | 0.03 |

| Luxembourg | 188 | 1.38 |

| Malta | 30 | 0.22 |

| Netherlands | 501 | 3.68 |

| Norway | 398 | 2.93 |

| Poland | 197 | 1.45 |

| Portugal | 105 | 0.77 |

| Romania | 15 | 0.11 |

| Russia | 320 | 2.35 |

| Slovenia | 9 | 0.07 |

| Spain | 430 | 3.16 |

| Sweden | 1480 | 10.89 |

| Switzerland | 1089 | 8.01 |

| Ukraine | 14 | 0.10 |

| United Kingdom | 3324 | 24.46 |

| Total | 13,596 | 100 |

| Year | Freq. | Percent |

| 2010 | 499 | 3.67 |

| 2011 | 526 | 3.87 |

| 2012 | 543 | 3.99 |

| 2013 | 552 | 4.06 |

| 2014 | 571 | 4.20 |

| 2015 | 615 | 4.52 |

| 2016 | 642 | 4.72 |

| 2017 | 702 | 5.16 |

| 2018 | 934 | 6.87 |

| 2019 | 1158 | 8.52 |

| 2020 | 1535 | 11.29 |

| 2021 | 1740 | 12.80 |

| 2022 | 1782 | 13.11 |

| 2023 | 1797 | 13.22 |

| Total | 13,596 | 100 |

| Sector | Freq. | Percent |

| Basic Materials | 1771 | 13.03 |

| Consumer Cyclicals | 2655 | 19.53 |

| Consumer Non-Cyclicals | 1195 | 8.79 |

| Energy | 894 | 6.58 |

| Healthcare | 1456 | 10.71 |

| Industrials | 3364 | 24.74 |

| Technology | 2261 | 16.62 |

| Total | 13,596 | 100 |

| Driscoll-Kraay Regression | Driscoll-Kraay Regression | Driscoll-Kraay Regression | IV-2SLS | IV-2SLS | IV-2SLS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABSDA | Jones Model | Modified Jones Model | Performance-Matched Model | Jones Model | Modified Jones Model | Performance-Matched Model | ||||||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

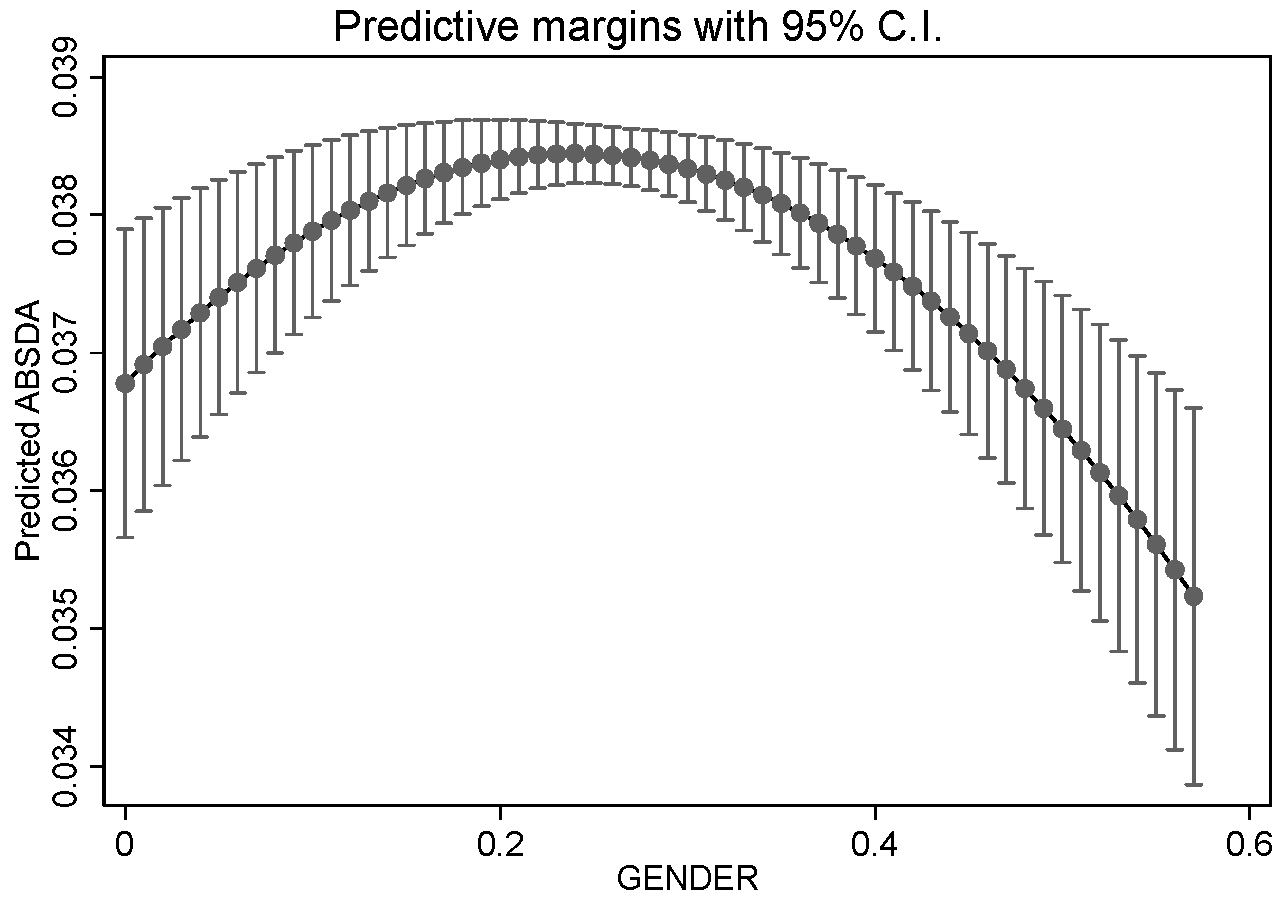

| Interval | 0 | 0.571 | 0 | 0.571 | 0 | 0.571 | 0 | 0.571 | 0 | 0.571 | 0 | 0.571 |

| Slope | 0.014 | −0.019 | 0.011 | −0.017 | 0.010 | −0.016 | 0.021 | −0.025 | 0.019 | −0.025 | 0.019 | −0.024 |

| t-value | 4.237 | −5.423 | 2.434 | −4.941 | 2.384 | −4.918 | 3.146 | −3.285 | 2.587 | −3.025 | 2.538 | −2.950 |

| Overall test p-value | 0.000 | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.005 | ||||||

| Turning point | 0.239 | 0.224 | 0.223 | 0.258 | 0.247 | 0.248 | ||||||

| 95% Fieller C.I. | [0.155–0.313] | [0.050–0.301] | [0.042–0.302] | [0.196–0.316] | [0.150–0.309] | [0.148–0.312] | ||||||

| Jones Model | Modified Jones Model | Performance-Matched Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: | GENDER | GENDER2 | GENDER | GENDER2 | GENDER | GENDER2 |

| GENDERt−1 | 0.906 *** | 0.106 *** | 0.852 *** | 0.070 *** | 0.852 *** | 0.070 *** |

| (52.291) | (12.590) | (40.049) | (6.623) | (40.049) | (6.623) | |

| GENDERt−2 | 0.093 *** | 0.056 *** | 0.093 *** | 0.056 *** | ||

| (7.778) | (7.531) | (7.778) | (7.531) | |||

| GENDER2t−1 | −0.154 *** | 0.655 *** | −0.197 *** | 0.637 *** | −0.197 *** | 0.637 *** |

| (−5.007) | (34.937) | (−6.097) | (32.120) | (−6.097) | (32.120) | |

| GENDER_INDUSTRY | 0.105 *** | 0.044 *** | 0.072 *** | 0.030 * | 0.072 *** | 0.030 * |

| (4.107) | (2.811) | (2.705) | (1.797) | (2.705) | (1.797) | |

| IND | 0.018 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.015 *** | 0.005 *** | 0.015 *** | 0.005 *** |

| (6.269) | (4.051) | (4.884) | (3.054) | (4.884) | (3.054) | |

| DUALITY | 0.002 | 0.002 ** | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| (1.477) | (2.439) | (0.156) | (1.469) | (0.156) | (1.469) | |

| LEVERAGE | −0.004 | −0.000 | −0.003 | −0.000 | −0.003 | −0.000 |

| (−0.851) | (−0.089) | (−0.534) | (−0.164) | (−0.534) | (−0.164) | |

| LNSIZE | 0.002 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.001 *** |

| (5.027) | (4.009) | (4.490) | (3.473) | (4.490) | (3.473) | |

| R&D | −0.032 | −0.022 | −0.018 | −0.014 | −0.018 | −0.014 |

| (−1.299) | (−1.442) | (−0.626) | (−0.811) | (−0.626) | (−0.811) | |

| LIQUIDITY | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| (0.556) | (0.735) | (0.629) | (0.738) | (0.629) | (0.738) | |

| GROWTH | 0.005 * | 0.003 * | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.003 |

| (1.727) | (1.664) | (1.277) | (1.393) | (1.277) | (1.393) | |

| BIG4 | 0.002 * | 0.001 | 0.003 ** | 0.001 | 0.003 ** | 0.001 |

| (1.863) | (1.177) | (2.237) | (1.500) | (2.237) | (1.500) | |

| ROA | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.017 * | 0.008 | 0.017 * | 0.008 |

| (0.703) | (0.656) | (1.702) | (1.519) | (1.702) | (1.519) | |

| GDP | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (−0.592) | (−1.158) | (−0.401) | (−1.006) | (−0.401) | (−1.006) | |

| CONSTANT | −0.053 *** | −0.037 *** | −0.038 *** | −0.032 *** | −0.038 *** | −0.032 *** |

| (−3.941) | (−4.773) | (−2.698) | (−3.835) | (−2.698) | (−3.835) | |

| Observations | 11,004 | 11,004 | 9364 | 9364 | 9364 | 9364 |

| Industry dummies | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Year dummies | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| F-statistic p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| S-W F statistics | 3298 | 3230 | 1834 | 1827 | 1834 | 1827 |

| 1 | Concerning the first-stage regressions, we utilized the IV-2SLS F-statistics to assess instrument strength and the Sanderson–Windmeijer F-test to evaluate instrument weakness (Null: Weak instruments). The detailed first-stage outcomes and statistics for Model 5 are available upon request. |

| 2 | We gratefully acknowledge the anonymous reviewer for this valuable suggestion. |

References

- Agoraki, Maria-Eleni K., Georgios P. Kouretas, and Christos Triantopoulos. 2020. Democracy, regulation and competition in emerging banking systems. Economic Modelling 84: 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaparte, Yosef. 2024. Why do stock markets negatively price democracy? Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 91: 101905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaziz, Dhouha, Bassem Salhi, and Anis Jarboui. 2020. CEO characteristics and earnings management: Empirical evidence from France. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 18: 77–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahma, Sanjukta, Chioma Nwafor, and Agyenim Boateng. 2021. Board gender diversity and firm performance: The UK evidence. International Journal of Finance & Economics 26: 5704–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechow, Patricia M., Richard G. Sloan, and Amy P. Sweeney. 1995. Detecting earnings management. Accounting Review 70: 193–225. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Xingqiang, Shaojuan Lai, and Hongmei Pei. 2016. Do women top managers always mitigate earnings management? Evidence from China. China Journal of Accounting Studies 4: 308–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gull, Ammar Ali, Mehdi Nekhili, Haithem Nagati, and Tawhid Chtioui. 2018. Beyond gender diversity: How specific attributes of female directors affect earnings management. The British Accounting Review 50: 255–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haans, Richard F. J., Constant Pieters, and Zi-Lin He. 2016. Thinking about U: Theorizing and testing U-and inverted U-shaped relationships in strategy research. Strategic Management Journal 37: 1177–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Jennifer J. 1991. Earnings management during import relief investigations. Journal of Accounting Research 29: 193–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, Sagar P., Andrew J. Leone, and Charles E. Wasley. 2005. Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of Accounting and Economics 39: 163–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouaib, Amel, and Abdullah Almulhim. 2019. Earnings manipulations and board’s diversity: The moderating role of audit. The Journal of High Technology Management Research 30: 100356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyaw, Khine, Mojisola Olugbode, and Barbara Petracci. 2015. Does gender diverse board mean less earnings management? Finance Research Letters 14: 135–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghavi, Navaz, Saeed Pahlevan Sharif, and Hafezali Bin Iqbal Hussain. 2021. The role of national culture in the impact of board gender diversity on firm performance: Evidence from a multi-country study. Equality Diversity and Inclusion 40: 631–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Quang Khai. 2024. Women in top executive positions, external audit quality and financial reporting quality: Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 14: 993–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Tuan, An Nguyen, Mau Nguyen, and Thuyen Truong. 2021. Is national governance quality a key moderator of the boardroom gender diversity–firm performance relationship? International evidence from a multi-hierarchical analysis. International Review of Economics & Finance 73: 370–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, Ann L., and Judit Temesvary. 2018. The performance effects of gender diversity on bank boards. Journal of Banking & Finance 90: 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Olojede, Erin Olayinka, and Adetula Dorcas. 2023. Do corporate governance mechanisms restrain earnings management? Evidence from Nigeria. International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics 17: 544–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saona, Paolo, Laura Muro, Pablo San Martín, and Ryan McWay. 2024. Do board gender diversity and remuneration impact earnings quality? Evidence from Spanish firms. Gender in Management: An International Journal 39: 18–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Yezhou, Lu Qiao, Suyang Li, and Ziwen Bu. 2021. Political freedom and earnings management. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 75: 101443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socol, Adela, and Iulia Cristina Iuga. 2025. Does democracy matter in banking performance? Exploring the linkage between democracy, economic freedom and banking performance in the European Union member states. International Journal of Finance & Economics 30: 86–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Jerry, Guoping Liu, and George Lan. 2011. Does Female Directorship on Independent Audit Committees Constrain Earnings Management? Journal of Business Ethics 99: 369–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, Muhammad, Muhammad Umar Farooq, Junrui Zhang, Muhammad Abdul Majid Makki, and Muhammad Kaleem Khan. 2019. Female directors and the cost of debt: Does gender diversity in the boardroom matter to lenders? Managerial Auditing Journal 34: 374–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varouchas, Evangelos, Stavros Arvanitis, Emmanuel Mamatzakis, and George M. Agiomirgianakis. 2024. Examining the influence of gender and ethnic diversity on bank performance: Empirical insights from the USA. International Journal of Banking, Accounting and Finance 14: 513–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Obs. | Mean | Sd. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABSDA (Jones model) | 11,549 | 0.038 | 0.028 | 0.001 | 0.123 |

| ABSDA (Modified Jones model) | 11,539 | 0.039 | 0.028 | 0.001 | 0.124 |

| ABSDA (Performance-matched model) | 11,539 | 0.039 | 0.028 | 0.001 | 0.125 |

| GENDER | 13,596 | 0.256 | 0.149 | 0 | 0.571 |

| IND | 13,541 | 0.547 | 0.267 | 0 | 1 |

| DUALITY | 13,596 | 0.235 | 0.424 | 0 | 1 |

| LEVERAGE | 13,596 | 0.248 | 0.168 | 0 | 0.764 |

| LNSIZE | 13,596 | 21.506 | 1.885 | 16.756 | 25.798 |

| R&D | 13,596 | 0.015 | 0.041 | 0 | 0.263 |

| LIQUIDITY | 13,563 | 0.429 | 0.202 | 0.060 | 0.964 |

| GROWTH | 12,145 | 0.087 | 0.262 | −0.617 | 1.378 |

| BIG4 | 13,596 | 0.388 | 0.487 | 0 | 1 |

| ROA | 13,596 | 0.031 | 0.110 | −0.542 | 0.295 |

| GDP | 13,596 | 1.676 | 3.807 | −28.800 | 24.500 |

| DEM | 13,596 | 8.440 | 1.027 | 2.220 | 9.930 |

| Driscoll-Kraay Regression | IV-2SLS Regression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: ABSDA | Jones Model | Modified Jones Model | Performance-Matched Model | Jones Model | Modified Jones Model | Performance-Matched Model |

| GENDER | 0.014 *** | 0.011 ** | 0.010 ** | 0.021 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.019 ** |

| (4.237) | (2.434) | (2.384) | (3.146) | (2.587) | (2.538) | |

| GENDER2 | −0.029 *** | −0.024 *** | −0.023 *** | −0.040 *** | −0.039 *** | −0.038 *** |

| (−5.910) | (−3.918) | (−3.877) | (−3.357) | (−2.939) | (−2.873) | |

| IND | −0.007 *** | −0.007 *** | −0.007 *** | −0.007 *** | −0.007 *** | −0.007 *** |

| (−5.898) | (−6.081) | (−5.951) | (−8.420) | (−6.932) | (−7.135) | |

| DUALITY | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (−0.064) | (0.053) | (0.061) | (0.012) | (0.047) | (0.083) | |

| LEVERAGE | 0.015 ** | 0.015 ** | 0.015 ** | 0.016 *** | 0.013 *** | 0.014 *** |

| (2.900) | (2.706) | (2.743) | (9.371) | (7.116) | (7.269) | |

| LNSIZE | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** |

| (−20.049) | (−24.178) | (−10.995) | (−15.067) | (−14.656) | (−12.511) | |

| R&D | 0.029 * | 0.027 * | 0.030 ** | 0.028 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.029 *** |

| (2.050) | (1.876) | (2.166) | (4.229) | (3.515) | (3.683) | |

| LIQUIDITY | −0.023 *** | −0.018 *** | −0.019 *** | −0.022 *** | −0.020 *** | −0.020 *** |

| (−9.850) | (−6.204) | (−7.137) | (−14.936) | (−11.575) | (−11.679) | |

| GROWTH | 0.002 | 0.017 *** | 0.017 *** | 0.002 | 0.017 *** | 0.017 *** |

| (1.251) | (12.784) | (13.077) | (1.580) | (12.887) | (13.031) | |

| BIG4 | −0.001 * | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 *** | −0.001 ** | −0.001 ** |

| (−1.932) | (−1.743) | (−1.623) | (−2.612) | (−2.347) | (−2.148) | |

| ROA | 0.014 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.022 *** | 0.014 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.018 *** |

| (8.428) | (9.370) | (8.740) | (4.854) | (5.316) | (5.431) | |

| GDP | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** |

| (−3.334) | (−3.908) | (−3.928) | (−3.729) | (−4.056) | (−4.037) | |

| CONSTANT | 0.084 *** | 0.086 *** | 0.076 *** | 0.083 *** | 0.085 *** | 0.078 *** |

| (39.142) | (35.740) | (18.148) | (22.189) | (20.230) | (18.232) | |

| Observations | 11,413 | 11,404 | 11,404 | 11,004 | 9364 | 9364 |

| R2 | 0.462 | 0.454 | 0.459 | 0.459 | 0.463 | 0.465 |

| Firms | 1727 | 1727 | 1727 | |||

| Industry dummies | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Year dummies | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| LM-Anderson (p-value) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| Hansen (p-value) | 0.335 | 0.168 | 0.175 | |||

| Driscoll-Kraay Regression | IV-2SLS Regression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: ABSDA | Jones Model | Modified Jones Model | Performance-Matched Model | Jones Model | Modified Jones Model | Performance-Matched Model |

| GENDER | 0.168 *** | 0.157 *** | 0.164 *** | 0.223 *** | 0.214 *** | 0.227 *** |

| (5.347) | (4.485) | (4.386) | (5.263) | (4.888) | (5.157) | |

| GENDER2 | −0.246 *** | −0.245 *** | −0.255 *** | −0.373 *** | −0.370 *** | −0.390 *** |

| (−3.784) | (−3.563) | (−3.468) | (−3.815) | (−3.690) | (−3.874) | |

| GENDER × DEM | −0.019 *** | −0.018 *** | −0.019 *** | −0.024 *** | −0.024 *** | −0.025 *** |

| (−4.824) | (−4.109) | (−4.041) | (−4.811) | (−4.508) | (−4.807) | |

| GENDER2 × DEM | 0.026 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.028 *** | 0.040 *** | 0.040 *** | 0.042 *** |

| (3.337) | (3.231) | (3.171) | (3.473) | (3.373) | (3.581) | |

| DEM | 0.001 ** | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | 0.001 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.002 *** |

| (2.590) | (2.086) | (2.154) | (3.725) | (3.514) | (3.745) | |

| IND | −0.006 *** | −0.006 *** | −0.007 *** | −0.007 *** | −0.007 *** | −0.007 *** |

| (−5.798) | (−5.936) | (−5.868) | (−7.650) | (−7.506) | (−7.752) | |

| DUALITY | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (−0.668) | (−0.513) | (−0.529) | (−0.888) | (−0.560) | (−0.609) | |

| LEVERAGE | 0.015 ** | 0.015 ** | 0.015 ** | 0.016 *** | 0.015 *** | 0.016 *** |

| (2.920) | (2.719) | (2.756) | (9.310) | (8.861) | (9.106) | |

| LNSIZE | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** |

| (−19.822) | (−23.032) | (−10.998) | (−14.841) | (−15.431) | (−12.536) | |

| R&D | 0.030 * | 0.028 * | 0.030 ** | 0.029 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.029 *** |

| (2.123) | (1.941) | (2.243) | (4.416) | (3.896) | (4.297) | |

| LIQUIDITY | −0.023 *** | −0.018 *** | −0.019 *** | −0.023 *** | −0.018 *** | −0.019 *** |

| (−10.632) | (−6.559) | (−7.639) | (−15.101) | (−11.785) | (−12.341) | |

| GROWTH | 0.002 | 0.017 *** | 0.017 *** | 0.002 | 0.017 *** | 0.017 *** |

| (1.274) | (12.875) | (13.147) | (1.634) | (14.433) | (14.709) | |

| BIG4 | −0.001 * | −0.001 * | −0.001 * | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 ** |

| (−2.086) | (−1.904) | (−1.799) | (−3.091) | (−2.781) | (−2.533) | |

| ROA | 0.015 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.022 *** | 0.014 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.021 *** |

| (8.698) | (9.968) | (9.306) | (4.849) | (6.759) | (7.176) | |

| GDP | −0.001 ** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** |

| (−2.634) | (−3.213) | (−3.218) | (−3.722) | (−3.929) | (−3.989) | |

| CONSTANT | 0.075 *** | 0.076 *** | 0.066 *** | 0.071 *** | 0.072 *** | 0.061 *** |

| (14.576) | (13.289) | (8.713) | (13.954) | (13.780) | (11.715) | |

| Observations | 11,412 | 11,403 | 11,403 | 11,003 | 10,995 | 10,995 |

| R2 | 0.464 | 0.456 | 0.461 | 0.461 | 0.452 | 0.457 |

| Firms | 1727 | 1727 | 1727 | |||

| Industry dummies | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Year dummies | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| LM-Anderson (p-value) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| Hansen (p-value) | 0.500 | 0.145 | 0.147 | |||

| Dependent Variable: ABSDA | Jones Model | Modified Jones Model | Performance-Matched Model | Jones Model | Modified Jones Model | Performance-Matched Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GENDER | 0.011 *** | 0.010 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.023 | 0.019 | 0.019 |

| (3.598) | (3.026) | (2.778) | (1.103) | (0.828) | (0.832) | |

| GENDER2 | −0.015 *** | −0.012 ** | −0.011 * | −0.031 | −0.027 | −0.030 |

| (−2.873) | (−2.098) | (−1.920) | (−0.702) | (−0.540) | (−0.591) | |

| GENDER × DEM | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 | |||

| (−0.577) | (−0.389) | (−0.429) | ||||

| GENDER2 × DEM | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |||

| (0.380) | (0.305) | (0.376) | ||||

| DEM | −0.001 | −0.000 | −0.000 | |||

| (−1.127) | (−0.296) | (−0.219) | ||||

| IND | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| (1.111) | (0.921) | (1.112) | (1.113) | (0.918) | (1.108) | |

| DUALITY | 0.001 | 0.001 * | 0.001 ** | 0.001 | 0.001 * | 0.001 ** |

| (1.589) | (1.917) | (2.016) | (1.563) | (1.907) | (2.009) | |

| LEVERAGE | 0.012 *** | 0.011 *** | 0.011 *** | 0.012 *** | 0.011 *** | 0.011 *** |

| (9.807) | (8.121) | (7.803) | (9.797) | (8.118) | (7.802) | |

| LNSIZE | −0.005 *** | −0.006 *** | −0.005 *** | −0.005 *** | −0.006 *** | −0.005 *** |

| (−14.882) | (−13.525) | (−13.228) | (−14.794) | (−13.481) | (−13.190) | |

| R&D | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.018 * | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.018 * |

| (0.626) | (1.236) | (1.660) | (0.613) | (1.233) | (1.658) | |

| LIQUIDITY | −0.014 *** | −0.010 *** | −0.011 *** | −0.014 *** | −0.011 *** | −0.011 *** |

| (−8.884) | (−6.077) | (−6.083) | (−8.968) | (−6.105) | (−6.108) | |

| GROWTH | 0.005 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.005 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.021 *** |

| (12.782) | (44.787) | (45.077) | (12.834) | (44.763) | (45.052) | |

| BIG4 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (1.465) | (1.171) | (1.248) | (1.444) | (1.162) | (1.240) | |

| ROA | 0.013 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.017 *** | 0.013 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.017 *** |

| (7.296) | (9.794) | (8.704) | (7.251) | (9.769) | (8.681) | |

| GDP | −0.000 | −0.001 ** | −0.001 ** | −0.000 | −0.001 ** | −0.001 ** |

| (−1.252) | (−2.300) | (−2.385) | (−1.523) | (−2.361) | (−2.427) | |

| CONSTANT | 0.155 *** | 0.155 *** | 0.153 *** | 0.161 *** | 0.157 *** | 0.155 *** |

| (19.217) | (17.199) | (16.864) | (16.270) | (14.136) | (13.821) | |

| Observations | 11,338 | 11,329 | 11,329 | 11,337 | 11,328 | 11,328 |

| R2 | 0.907 | 0.884 | 0.884 | 0.908 | 0.884 | 0.883 |

| Industry fixed effects | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Year fixed effects | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Firm fixed effects | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Varouchas, E.G.; Arvanitis, S.E.; Floros, C. Gender Diverse Boardrooms and Earnings Manipulation: Does Democracy Matter? Risks 2025, 13, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13070126

Varouchas EG, Arvanitis SE, Floros C. Gender Diverse Boardrooms and Earnings Manipulation: Does Democracy Matter? Risks. 2025; 13(7):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13070126

Chicago/Turabian StyleVarouchas, Evangelos G., Stavros E. Arvanitis, and Christos Floros. 2025. "Gender Diverse Boardrooms and Earnings Manipulation: Does Democracy Matter?" Risks 13, no. 7: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13070126

APA StyleVarouchas, E. G., Arvanitis, S. E., & Floros, C. (2025). Gender Diverse Boardrooms and Earnings Manipulation: Does Democracy Matter? Risks, 13(7), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13070126