Stochastic Uncertainty of Institutional Quality and the Corporate Capital Structure in the G8 and MENA Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Impact of Country-Level Institutional Quality on Corporate Business

2.2. Institutional Quality and Corporate Financing Decisions in Developed Countries

2.3. Institutional Quality and Corporate Financing Decisions in Developing Countries

2.4. Macroeconomic Determinants of Capital Structure

2.4.1. GDP Growth

2.4.2. Inflation Rate

2.4.3. Unemployment

2.5. Hypothesis Development

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

3.2. Dependent Variable

3.3. Independent Variables

4. Results and Discussion

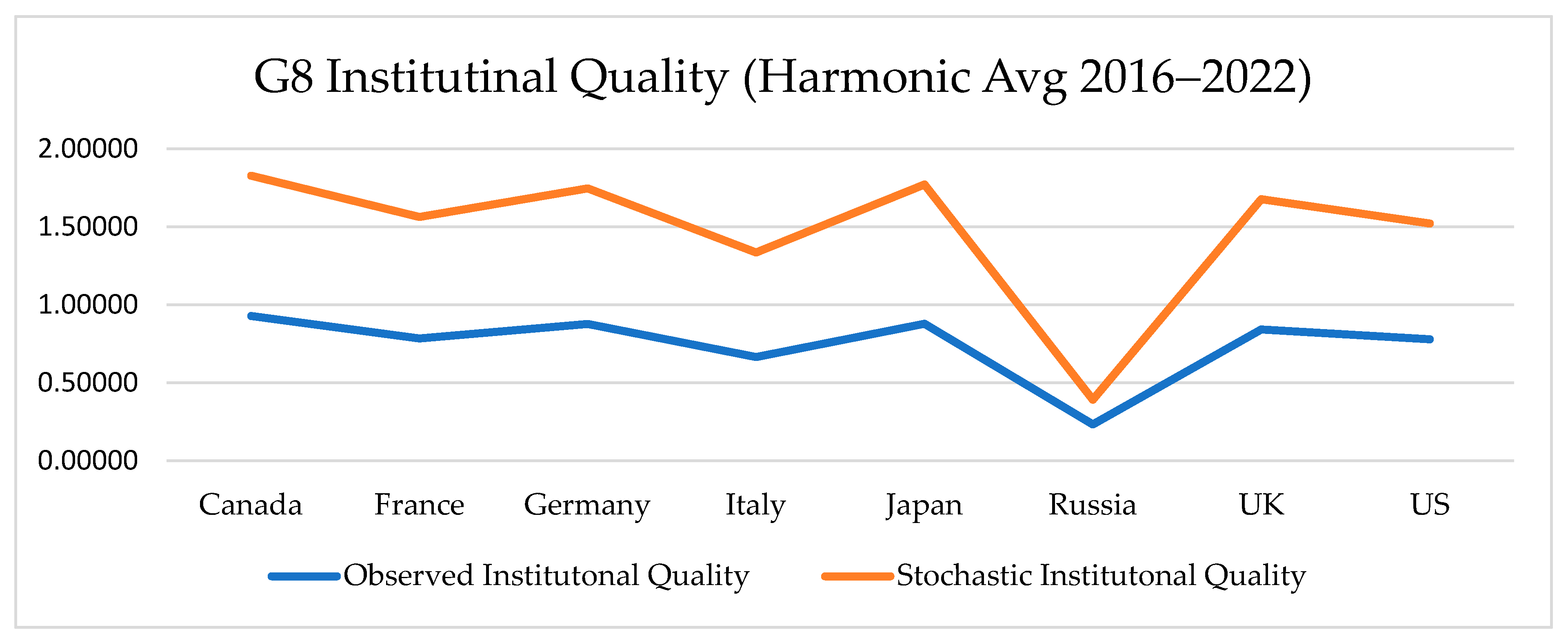

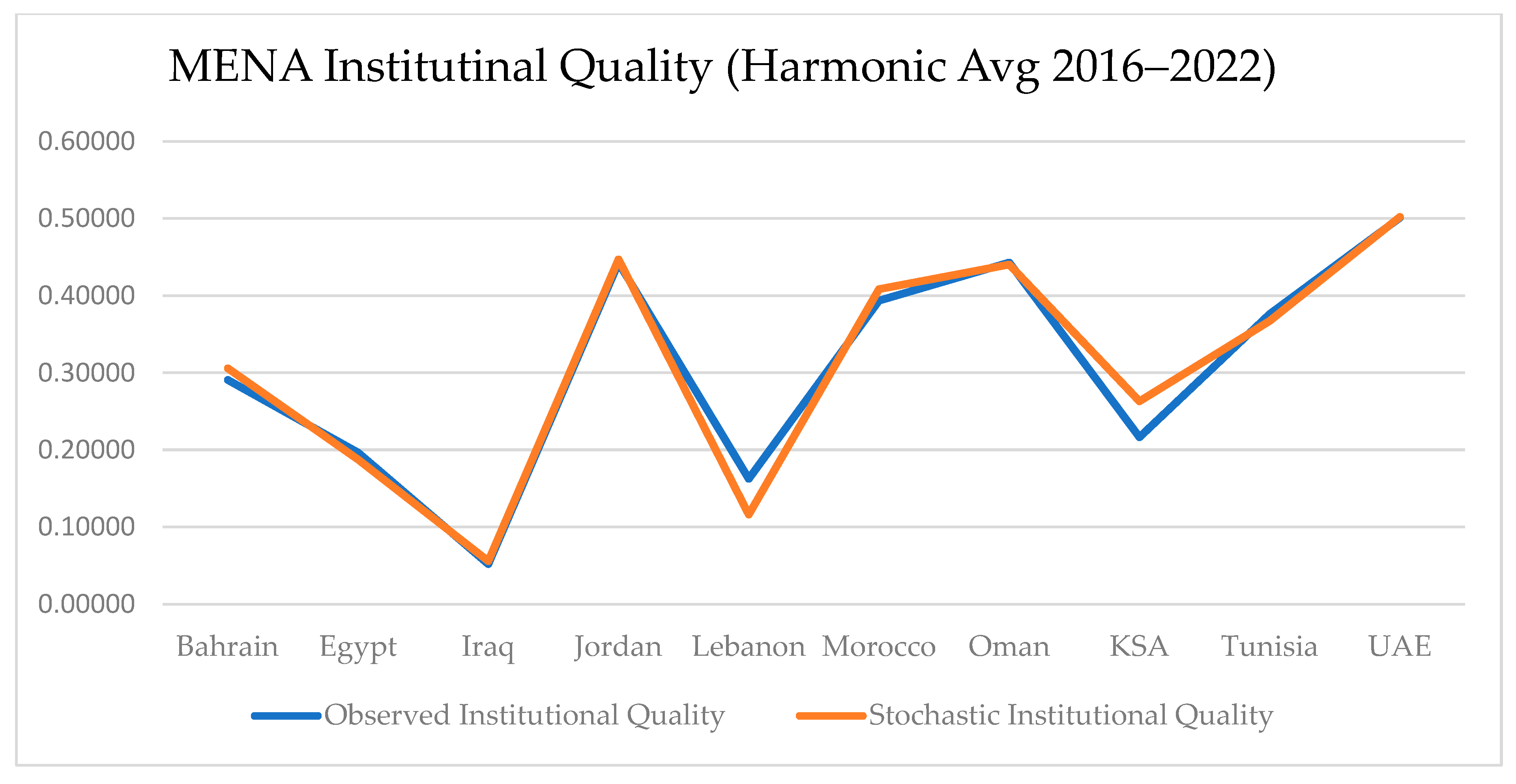

4.1. Observed Versus Uncertain Institutional Quality

4.2. Effects of Voice and Accountability on Corporate Capital Structure

4.3. Effect of Political Stability on Corporate Capital Structure

4.4. Effect of Government Effectiveness on the Corporate Capital Structure

5. Conclusions

- As the pillars of WGIs reflect a quantification of attitudes, high multicollinearity exists, which must be taken into consideration in future studies.

- Compared with MENA countries, G8 countries are characterized by stronger voice and accountability, resulting in more reliance on debt financing by the former than the latter. The expected (stochastic) effect remains positive in G8, indicating perseverance in protecting creditors’ contractual rights. The same is true in MENA countries, where an expected improvement in voice and accountability is observed.

- Political stability in G8 sustains debt financing, although a stochastic negative effect is estimated, indicating that potential political instability may result in companies relying on less debt financing. The same negative stochastic effect is estimated in MENA countries, which have the same implications.

- Government effectiveness has a crucial negative effect on debt financing in both G8 and MENA listed firms. This finding implies that stronger government effectiveness may lead to an expected reduction in debt financing and consequently more reliance on equity financing.

- The effect of firm size is still persistent over time and across different institutional arrangements. That is, large firms are able to secure and afford debt financing.

- The effects of macroeconomic factors reflect the essence of institutional quality. That is, in both regions, the observed and stochastic progress in GDP growth results in less debt financing. Nevertheless, the listed companies in the MENA region exhibit insignificant stochastic effects, indicating that the expected patterns of corporate debt financing may not be related to GDP growth. In addition, the observed and stochastic effects of inflation remain negative for corporate debt financing in the G8 and MENA economies. The unemployment rate plays a signaling role in G8 only, although the stochastic effect is statistically insignificant.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Linearity Versus Nonlinearity Test: G8 and MENA Countries1

| Countries | Results |

| G8 | F(3, 2145) = 1.745 (Prob > F = 0.1560) |

| MENA | F(3, 2588) = 2.32 (Prob > F = 0.191) |

Appendix B. Hausman Test: G8 and MENA Countries2

| Countries | Results |

| G8 | chi2 (10) = 12.97 (Prob > chi2 = 0.2252) |

| MENA | chi2 (5) = 18.65 (Prob > chi2 = 0.0022) |

Appendix C. Heteroscedasticity Test: G8 and MENA Countries (Breusch–Pagan/Cook–Weisberg Test)3

| Countries | Results |

| G8 | chi2 (1) = 171.22 (Prob > chi2 = 0.0000) |

| MENA | chi2 (1) = 303.38 (Prob > chi2 = 0.0000) |

| 1 | The results indicate that, at the 95% confidence level, the null hypothesis of the Ramsey RESET test is not rejected for both the G8 and MENA countries, suggesting that the linear model is appropriate. |

| 2 | The results indicate that the random-effects model is appropriate for the G8 countries, as the p value associated with the test exceeds 5%, whereas the fixed-effects model is appropriate for the data of the MENA countries, given that the corresponding p value is below 5%. |

| 3 | The results indicate that the null hypothesis of the Breusch–Pagan/Cook–Weisberg test for heteroskedasticity is rejected at the 95% confidence level. This suggests that the variance of the residuals is not constant, which requires the use the robust estimators. |

References

- Abor, Joshua. 2005. The effect of capital structure on profitability: An empirical analysis of listed firms in Ghana. The Journal of Risk Finance 6: 438–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson. 2005. Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth. In Handbook of Economic Growth. Edited by Philippe Aghion and Steven N. Durlauf. North Holland: Elsevier, vol. 1A, pp. 385–472. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Fatma, and David G. McMillan. 2023. Capital structure and political connections: Evidence from GCC banks and the financial crisis. International Journal of Emerging Markets 18: 2890–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alim, Wajid, Naqib U. Khan, Vince W. Zhang, Helen H. Cai, A. Mikhaylov, and Qiong Yuan. 2024. Influence of political stability on the stock market returns and volatility: GARCH and EGARCH approach. Financial Innovation 10: 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, Paulo F. Pereira, and Miguel A. Ferreira. 2011. Capital structure and law around the world. Journal of Multinational Financial Management 21: 119–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, Antonios, Yilmaz Guney, and Krishna Paudyal. 2006. The determinants of debt maturity structure: Evidence from France, Germany and the UK. European Financial Management 12: 161–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asteriou, Dimitrios, Keith Pilbeam, and Iuliana Tomuleasa. 2021. The impact of corruption, economic freedom, regulation and transparency on bank profitability and bank stability: Evidence from the Eurozone area. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 184: 150–77. [Google Scholar]

- Awartani, Basel, Moamed Belkhir, Sabri Boubaker, and Aktham Maghyereh. 2016. Corporate debt maturity in the MENA region: Does institutional quality matter? International Review of Financial Analysis 46: 309–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Scott R., Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis. 2016. Measuring economic policy uncertainty. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131: 1593–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, Arindam, and Nandita M. Barua. 2016. Factors determining capital structure and corporate performance in India: Studying the business cycle effects. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 61: 160–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basto, Douglas Dias, Wilson T. Nakamura, and Leonardo C. Basso. 2009. Determinants of Capital Structure of Publicly Traded Companies in Latin America: The Role of Institutional and Macroeconomics Factors. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1365987 (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Beck, Thorsten, Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, and Vojislav Maksimovic. 2002. Financing Patterns Around the World: The Role of Institutions. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2905. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Belghitar, Yacine, Ephraim Clark, and Abubakr Saeed. 2019. Political connections and corporate financial decision making. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 53: 1099–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkhir, Mohamed, Aktham Maghyereh, and Basel Awartani. 2016. Institutions and corporate capital structure in the MENA region. Emerging Markets Review 26: 99–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hamouda, Raja Zekri, Nessrine Hamzaoui, and Jilani Jilani. 2023. Capital Structure determinants: New evidence from the MENA region countries. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 13: 144–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, Rumeysa. 2019. Relative importance of country and firm-specific determinants of capital structure: A multilevel approach. Prague Economic Papers 28: 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokpin, Godfred A. 2009. Macroeconomic development and capital structure decisions of firms: Evidence from emerging market economies. Studies in Economics and Finance 26: 129–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, Laurence, Varouj Aivazian, Asli Demirguc-Kunt, and Vojislav Maksimovic. 2001. Capital structures in developing countries. The Journal of Finance 56: 87–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubakri, Narjess, Jean C. Cosset, and Walid Saffar. 2012a. The impact of political connections on Firms’ operating performance and financing decisions. Journal of Financial Research 35: 397–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubakri, Narjess, Omrane Guedhami, Dev Mishra, and Walid Saffar. 2012b. Political Connections and the Cost of Equity Capital. Journal of Corporate Finance 18: 514–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahan, Steven, David Emanuel, and Jerry Sun. 2009. The Effect of Earnings Quality and Country-level Institutions on the Value Relevance of Earnings. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 33: 371–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, Omar. 2012. Capital structure adjustment speed and macroeconomic conditions: US MNCs and DCs. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics 84: 106–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Wenbin, Xiaoman Duan, and Vahap B. Uysal. 2013. Does political uncertainty affect capital structure choices? Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 53: 1689–99. [Google Scholar]

- Cashman, George D., David M. Harrison, and Hainan Sheng. 2015. Political risk and the cost of capital in Asia-Pacific property markets. International Real Estate Review 18: 331–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaney, Paul K., Mara Faccio, and David Parsley. 2011. The quality of accounting information in politically connected firms. Journal of Accounting and Economics 51: 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Chih-Ying, Peter F. Chen, and Qinglu Jin. 2015. Economic freedom, investment flexibility, and equity value: A cross-country study. The Accounting Review 90: 1839–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherni, Fatma. 2022. The quality of institutions on capital structure: Evidence from MENA region. Applied Mathematics & Information Sciences 16: 159–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chipeta, Chimwemwe, and Chera Deressa. 2016. Firm and country specific determinants of capital structure in Sub Saharan Africa. International Journal of Emerging Markets 11: 649–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Seong-Soon, Sadok El Ghoul, Omrane Guedhami, and Jungwon Suh. 2014. Creditor rights and capital structure: Evidence from international data. Journal of Corporate Finance 25: 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chortareas, Georgios E., Claudia Girardone, and Alexia Ventouri. 2013. Financial freedom and bank efficiency: Evidence from the European Union. Journal of Banking & Finance 37: 1223–31. [Google Scholar]

- Claessens, Stijn, and Luc Laeven. 2004. What drives bank competition? Some international evidence. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 36: 563–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, Stijn, Erik Feijen, and Luc Laeven. 2008. Political connections and preferential access to finance: The role of campaign contributions. Journal of Financial Economics 88: 554–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Daniel A., and Paul Zarowin. 2010. Accrual-based and real earnings management activities around seasoned equity offerings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50: 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonnelli, Emanuele, and Mounu Prem. 2017. Corruption and Firms: Evidence from Randomized Audits in Brazil. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2931602 (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Consigli, Giorgio, Daniel Kuhn, and Paolo Brandimarte. 2017. Optimal Financial Decision Making Under Uncertainty. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Çam, İlhan, and Gökhan Özer. 2021. Institutional quality and corporate financing decisions around the world. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 57: 101401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, Abe, Rezaul Kabir, and Thuy T. Nguyen. 2008. Capital structure around the world: The roles of firm-and country-specific determinants. Journal of Banking & Finance 32: 1954–69. [Google Scholar]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, Asli, and Vojislav Maksimovic. 1999. Institutions, financial markets, and firm debt maturity. Journal of Financial Economics 54: 295–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessai, Mihir A., C. Fritz Foley, and James R. Hines, Jr. 2008. Capital Structure with Risky Foreign Investment. Journal of Financial Economics 88: 534–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwan, Ishac, and Marc Schiffbauer. 2018. Private banking and crony capitalism in Egypt. Business and Politics 20: 390–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupačová, Jitka, Jan Hurt, and Josef Štěpán. 2003. Stochastic Modeling in Economics and Finance. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ebaid, El-Sayed I. 2009. The impact of capital-structure choice on firm performance: Empirical evidence from Egypt. The Journal of Risk Finance 10: 477–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldomiaty, Tarek. I. 2008. Determinants of corporate capital structure: Evidence from an emerging economy. International Journal of Commerce and Management 17: 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etudaiye-Muhtar, Oyebola F., Rubi Ahmad, and Bolaji T. Matemilola. 2017. Corporate debt maturity structure: The role of firm level and institutional determinants in selected African countries. Global Economic Review 46: 422–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, Mara. 2006. Politically Connected Firms. American Economic Review 96: 369–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Joseph P. H., Sheridan Titman, and Garry Twite. 2012. An international comparison of capital structure and debt maturity choices. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 47: 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinha, Jorge. 2003. Corporate Governance: A Survey of the Literature. Discussion Paper No. 2003-06. Porto: Universidade do Porto, Faculdade de Economia do Porto. [Google Scholar]

- Feynman, Richard Phillips. 2013. The Brownian Movement. Pasadena: California Institute of Technology, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, Murray Z., and Vidhan K. Goyal. 2003. Testing the pecking order theory of capital structure. Journal of Financial Economics 67: 217–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, Murray Z., and Vidhan K. Goyal. 2009. Capital structure decisions: Which factors are reliably important? Financial Management 38: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajurel, Dinesh. 2006. Macroeconomic Influences on Corporate Capital Structure. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=899049 (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Goldman, Eitan, Jörg Rocholl, and Jongil So. 2009. Do politically connected boards affect firm value? The Review of Financial Studies 22: 2331–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greif, Avner. 2006. Institutions and the Path to the Modern Economy: Lessons from Medieval Trade. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gropper, Daniel M., John S. Jahera, Jr., and Junk C. Park. 2015. Political power, economic freedom and Congress: Effects on bank performance. Journal of Banking & Finance 60: 76–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gwatidzo, Tendai, and Kalu Ojah. 2014. Firms’ debt choice in Africa: Are institutional infrastructure and non-traditional determinants important? International Review of Financial Analysis 31: 152–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, Christopher A. 2018. The impact of institutional volatility on financial volatility in transition economies. Journal of Comparative Economics 46: 598–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, Jerry A. 1978. Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 46: 1251–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, Jerry A., and William E. Taylor. 1981. Panel data and unobservable individual effects. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 49: 1377–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearn, Bruce. 2013. The Determinants of director Remuneration in West Africa: The Impact of State versus Firm-Level Governance Measures. Emerging Markets Review 14: 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearn, Bruce. 2014. Institutional Impact of the Expropriation of Private Benefits of Control in North Africa. Research in International Business and Finance 30: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmelgarn, Thomas, and Daniel Teichmann. 2014. Tax reforms and the capital structure of banks. International Tax and Public Finance 21: 645–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, Phan Thi Quoc. 2017. Macroeconomic factors and corporate capital structure: Evidence from listed joint stock companies in Vietnam. International Journal of Financial Research 9: 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibe, Oliver C. 2013. Markov Processes for Stochastic Modeling. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Iona, Alfonsina, Andrea Calef, and Ifigenia Georgiou. 2023. Credit Market Freedom and Corporate Decisions. Mathematics 11: 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, Pankaj K., Emre Kuvvet, and Michael S. Pagano. 2017. Corruption’s impact on foreign portfolio investment. International Business Review 26: 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, Jacek, and Leszek Czerwonka. 2019. Meta-study on the relationship between macroeconomic and institutional environment and internal determinants of enterprises’ capital structure. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 32: 2614–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Michael C. 1986. Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. American Economic Review 76: 323–29. [Google Scholar]

- Joskow, Paul L. 2008. Introduction to New Institutional Economics: A Report Card. In New Institutional Economics: A Guidebook. Edited by Éric Brousseau and Jean-Michel Glachant. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jõeveer, Karin. 2013. Firm, country and macroeconomic determinants of capital structure: Evidence from transition economies. Journal of Comparative Economics 41: 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julio, Brandon, and Youngsuk Yook. 2012. Political uncertainty and corporate investment cycles. The Journal of Finance 67: 45–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2011. The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues1. Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 3: 220–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwaja, Asim I., and Atif Mian. 2005. Do lenders favor politically connected firms? Rent provision in an emerging financial market. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 120: 1371–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korajczyk, Robert A., and Amnon Levy. 2003. Capital structure choice: Macroeconomic conditions and financial constraints. Journal of Financial Economics 68: 75–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Satish, Sisira Colombage, and Purnima Rao. 2017. Research on capital structure determinants: A review and future directions. International Journal of Managerial Finance 13: 106–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. 1997. Legal determinants of external finance. The Journal of Finance 52: 1131–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. 1998. Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy 106: 1113–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemma, Tesfaye T. 2015. Corruption, debt financing and corporate ownership. Journal of Economic Studies 42: 433–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Peisen, Houjian Li, and Hua Gou. 2020. The impact of corruption on firms’ access to bank loans: Evidence from China. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 33: 1963–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Iturriaga, Félix J., and Juan A. Rodriguez-Sanz. 2008. Capital structure and institutional setting: A decompoitional and international analysis. Applied Economics 40: 1851–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matemilola, Bolaji Tunde, A. N. Bany-Ariffin, W. N. W. Azman-Saini, and Annuar M. Nassir. 2019. Impact of institutional quality on the capital structure of firms in developing countries. Emerging Markets Review 39: 175–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, Pervaiz Ahmed, Rohani Bt Md Rus, and Zahiruddin B. Ghazali. 2015. Firm and macroeconomic determinants of debt: Pakistan evidence. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 172: 200–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Merton H. 1977. Debt and Taxes. Journal of Finance 32: 261–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modigliani, Franco, and Merton H. Miller. 1958. The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. The American Economic Review 48: 261–97. [Google Scholar]

- Modigliani, Franco, and Merton H. Miller. 1963. Corporate income taxes and the cost of capital: A correction. American Economic Review 53: 433–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mokhova, Natalia, and Marek Zinecker. 2014. Macroeconomic factors and corporate capital structure. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 110: 530–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Mendoza, Jorge A., Sandra M. Sepúlveda Yelpo, Carmen L. Velosos Ramos, and Carlos L. Delgado Fuentealba. 2021. Effects of capital structure and institutional–financial characteristics on earnings management practices: Evidence from Latin American firms. International Journal of Emerging Markets 16: 580–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthama, Charles, Peter Mbaluka, and Elizabeth Kalunda. 2013. An empirical analysis of macroeconomic influences on corporate capital structure of listed companies in Kenya. Journal of Finance and Investment Analysis 2: 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Nejad, Niloufar R., and Shaista Wasiuzzaman. 2015. Multilevel determinants of capital structure: Evidence from Malaysia. Global Business Review 16: 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Huyen Thuy Bich Tram, and Thi Thuy Linh Tran. 2017. Institutional Quality Matters and Vietnamese Corporate Debt Maturity. Vnu Journal of Economics and Business 33: 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- North, Douglass C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- North, Douglass C. 1993. Economic Performance Through Time. Lecture to the Memory of Alfred Nobel. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/1993/north/lecture (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- North, Douglass C. 2005. Understanding the Process of Economic Change. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- North, Douglass C. 2008. Institutions and the Performance of Economies over Time. In Handbook on New Institutional Economics. Edited by Claude Ménard and Mary M. Shirley. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Obay, Lamia A. 2018. The capital structure choice: Evidence of debt maturity substitution by GCC firms. Asian Economic and Financial Review 8: 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, Mohammad M., and John Pointon. 2009. Capital structure and firm characteristics: An empirical analysis from Egypt. Review of Accounting and Finance 8: 454–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztekin, Özde. 2015. Capital structure decisions around the world: Which factors are reliably important? Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 50: 301–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Wei-Fong, Xinjie Wang, and Shanxiang Yang. 2019. Debt maturity, leverage, and political uncertainty. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 50: 100981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Jun, and Philip E. Strahan. 2007. How laws and institutions shape financial contracts: The case of bank loans. The Journal of Finance 62: 2803–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, Raghuram G., and Luigi Zingales. 1995. What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data. The journal of Finance 50: 1421–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, James Bernard. 1969. Tests for specification errors in classical linear least-squares regression analysis. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 31: 350–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, Zia U. 2016. Impact of macroeconomic variables on capital structure choice: A case of textile industry of Pakistan. The Pakistan Development Review 55: 227–39. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, Scott. 2006. Over-Investment of Free Cash Flows. Review of Accounting Studies 11: 159–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saona, Paolo, Eleuterio Vallelado, and Pablo San Martín. 2020. Debt, or not debt, that is the question: A Shakespearean question to a corporate decision. Journal of Business Research 115: 378–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapra, Sunil. 2005. A regression error specification test (RESET) for generalized linear models. Economics Bulletin 3: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert, Bruce, and Halit Gonenc. 2016. Creditor rights, country governance, and corporate cash holdings. Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting 27: 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shambor, Aws Yousef. 2017. The determinants of capital structure: Empirical analysis of oil and gas firms during 2000–2015. Asian Journal of Finance and Accounting 9: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Bhanu P., and M. Kannadhasan. 2020. Corruption and capital structure in emerging markets: A panel quantile regression approach. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 28: 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Jared D. 2016. US political corruption and firm financial policies. Journal of Financial Economics 121: 350–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Jeremy C. 1989. Efficient capital markets, inefficient firms: A model of myopic corporate behavior. Quarterly Journal of Economics 104: 655–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tag, Mehmet N., and Suleyman Degirmen. 2022. Economic freedom and foreign direct investment: Are they related? Economic Analysis and Policy 73: 737–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Le M. 2017. Impact of the financial markets development on capital structure of firms listed on Ho Chi Minh stock exchange. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 7: 510–15. [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani, Reza, and Sara Najafzadeh Khoi. 2017. Investigating the impact of inflation uncertainty on the capital structure of firms listed in Tehran stock exchange. Financial Economics 11: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Temimi, Akram, Rami Zeitun, and Karim Mimouni. 2016. How does the tax status of a country impact capital structure? Evidence from the GCC region. Journal of Multinational Financial Management 37: 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thursby, Jerry G. 1979. Alternative specification error tests: A comparative study. Journal of the American Statistical Association 74: 222–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thursby, Jerry G., and Peter Schmidt. 1977. Some properties of tests for specification error in a linear regression model. Journal of the American Statistical Association 72: 635–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titman, Sheridan, and Roberto Wessels. 1988. The determinants of capital structure choice. The Journal of Finance 43: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, Diana A., Georgeta Vintila, and Stefan C. Gherghina. 2022. Firm-and Country-level drivers of capital structure: Quantitative evidence from central and Eastern European listed companies. Journal of Financial Studies and Research 2022: 572694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Shang-Jin, and Jing Zhou. 2018. Quality of Public Governance and the Capital Structure of Nations and Firms. No. w24184. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Weill, Laurent. 2011. Does corruption hamper bank lending? Macro and micro evidence. Empirical Economics 41: 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, Oliver E. 2002. The Theory of the Firm as Governance Structure: From Choice to Contract. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 16: 171–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Raymond M., Cephas Simon Peter Dak-Adzaklo, and Agnes W. Lo. 2024. Debt choice in the regulated competition era. Journal of International Money and Finance 142: 103045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, Jeffrey M. 2006. Cluster-sample methods in applied econometrics: An extended analysis. American Economic Review 93: 133–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2022. Available online: http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/#home (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Xu, Tao. 2019. Economic freedom and bilateral direct investment. Economic Modelling 78: 172–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, Amr, and Ayah El-Ghonamie. 2015. Factors that determine capital structure in building material and construction listed firms: Egypt case. International Journal of Financial Research 6: 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Hui, and Steven X. Zhu. 2017. Corporate innovation and economic freedom: Cross–country comparison. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 63: 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Conceptual Definition | Operational Definition | Authors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate Capital Structure | Long-term debt ratio | Long-term debt to total assets | (Abor 2005; Eldomiaty 2008; Ebaid 2009; Omran and Pointon 2009; Youssef and El-Ghonamie 2015; Bandyopadhyay and Barua 2016; Shambor 2017; Obay 2018) | |

| WGIs | Voice and Accountability | Refers to perceptions of the extent to which citizens have freedom of expression and media and are able to select government | Voice and Accountability Index constructed by the World Bank | (Kaufmann et al. 2011) |

| Political Stability | Refers to political stability and absence of violence in a country | Political Stability and Absence of Violence Index constructed by the World Bank | ||

| Government Effectiveness | Refers to perceptions of the quality of public service, the quality of civil service, and the degree of the government’s independence from political pressure | Government Effectiveness Index constructed by the World Bank | ||

| Regulatory Quality | Refers to the quality of a country’s regulatory environment | Regulatory Quality Governance Index constructed by the World Bank | ||

| Rule of Law | Refers to the perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, the police, and the courts | Rule of Law Index constructed by the World Bank | ||

| Control of Corruption | Refers to the control of corruption in a country | Control of Corruption Index constructed by the World Bank | ||

| Control | Economic Growth | GDP growth | GDP growth rate (calculated as the percentage change in GDP per capita across years) | Cohen and Zarowin (2010); Chen et al. (2015) |

| Inflation Rate | Inflation | Annual percentages of average consumer prices are year-on-year changes | ||

| Unemployment Rare | Unemployed workers are those who are currently not working but are willing and able to work for pay, currently available to work, and have actively searched for work | The number of unemployed persons as a percentage of the labor force (the total number of people employed plus unemployed) | ||

| Firm Size | The size of the firm | Natural logarithm of total assets | ||

| Country Membership | The country included in the analysis | Dummy variables (binary 0, 1) taking the value of 1 for a given country and 0 otherwise | Obay (2018) | |

| Descriptive Statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | Min. | Max. | Mean | Std. Deviation |

| Debt Ratio | 2163 | 0.0000171 | 0.9641 | 0.238993 | 0.172486 |

| Voice and Accountability | 2163 | 0.1449275 | 0.9660194 | 0.7744635 | 0.226162 |

| Political Stability | 2163 | 0.152381 | 0.9285714 | 0.552816 | 0.1574594 |

| Government Effectiveness | 2163 | 0.259434 | 0.9666666 | 0.8235676 | 0.1579148 |

| Regulatory Quality | 2163 | 0.1320755 | 0.9761905 | 0.8274535 | 0.2021162 |

| Rule of Law | 2163 | 0.1226415 | 0.9666666 | 0.7951969 | 0.2336246 |

| Control of Corruption | 2163 | 0.1666667 | 0.9619048 | 0.7973853 | 0.2330293 |

| GDP Growth | 2163 | −0.10645 | 0.06026 | 0.010336 | 0.0363128 |

| Inflation Rate | 2163 | −0.00648 | 0.05375 | 0.01566 | 0.0116451 |

| Unemployment Rate | 2163 | 0.02358 | 0.118 | 0.0609961 | 0.0244892 |

| Descriptive Statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | Min. | Max. | Mean | Std. Deviation |

| Debt Ratio | 2611 | 0.000137 | 0.7984 | 0.1401321 | 0.374187 |

| Voice and Accountability | 2611 | 0.0492611 | 0.5652174 | 0.1727827 | 0.1198541 |

| Political Stability | 2611 | 0.0141509 | 0.7190476 | 0.2754281 | 0.1454232 |

| Government Effectiveness | 2611 | 0.0754717 | 0.9047619 | 0.5331031 | 0.1753695 |

| Regulatory Quality | 2611 | 0.0904762 | 0.8285714 | 0.5059163 | 0.1681739 |

| Rule of Law | 2611 | 0.0238095 | 0.7877358 | 0.5165234 | 0.1671129 |

| Control of Corruption | 2611 | 0.052381 | 0.8349056 | 0.5236297 | 0.1760254 |

| GDP Growth | 2611 | −0.25 | 0.15199 | 0.0123362 | 0.0393075 |

| Inflation Rate | 2603 | −0.0193 | 1.4451 | 0.06792 | 0.0502162 |

| Unemployment Rate | 2611 | 0.0358 | 0.19075 | 0.0990754 | 0.0481625 |

| Dependent: Debt Ratio | Observed Institutional Determinants of Capital Structure | Stochastic Institutional Determinants of Capital Structure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G8 | MENA | G8 | MENA | |

| (Constant) | 0.417 *** (0.051) | 0.184 * (0.101) | −0.092 (0.165) | 0.417 *** (0.071) |

| Voice and Accountability | 0.106 *** (0.006) | −0.178 *** (0.023) | 0.387 *** (0.095) | 0.1494 ** (0.088) |

| Political Stability | 0.067 *** (0.005) | 0.026 (0.029) | −0.142 *** (0.034) | |

| Government Effectiveness | −0.311 *** (0.074) | −0.015 (0.107) | −0.358 *** (0.031) | |

| GDP Growth | −0.199 *** (0.068) | −0.402 ** (0.181) | −0.000046 *** (0.000008) | 0.000008 (0.000008) |

| Inflation Rate | −0.345 *** (0.037) | −0.1987 *** (0.018) | −0.851 *** (0.183) | −0.074 *** (0.030) |

| Unemployment Rate | −0.355 *** (0.020) | −0.889 (0.920) | 0.111 (0.072) | −0.049 (0.087) |

| Size Effect (Natural Log of Total Assets) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| G8 Country Effect (Dummy Variables Taking Binary Values) | Yes | Yes | ||

| MENA Country Effect (Dummy Variables Taking Binary Values) | Yes | Yes | ||

| Time | 0.0014 (0.0013) | 0.0024 (0.0033) | 0.0021 (0.0209) | 0.0093 (0.0063) |

| N | 2163 | 2603 | 1635 | 2238 |

| 0.5502 | 0.5060 | 0.9663 | 0.9722 | |

| Pesaran Cross-Sectional Dependence (CD) Test | 648.24 *** | 20.99 *** | 611.93 *** | 14.87 *** |

| Dependent: Debt Ratio | Stochastic Institutional Determinants of Capital Structure (G8 and MENA) |

|---|---|

| (Constant) | 0.1499 (0.0329) *** |

| Voice and Accountability | 0.1030 (0.072) |

| Inflation Rate | −0.0882 *** (0.0264) |

| Size Effect (Natural Log of Total Assets) | Yes |

| G8 and MENA Country Effect (Dummy Variables Taking Binary Values; 1 = G8, 0 = MENA) | Yes |

| Time | 0.00043 *** (0.00015) |

| N | 3876 |

| 0.9864 | |

| Pesaran Cross-Sectional Dependence (CD) Test | 43.844 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eldomiaty, T.; Azzam, I.; Fouad, J.; Sadek, H.M.; Sedik, M.A. Stochastic Uncertainty of Institutional Quality and the Corporate Capital Structure in the G8 and MENA Countries. Risks 2025, 13, 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13060111

Eldomiaty T, Azzam I, Fouad J, Sadek HM, Sedik MA. Stochastic Uncertainty of Institutional Quality and the Corporate Capital Structure in the G8 and MENA Countries. Risks. 2025; 13(6):111. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13060111

Chicago/Turabian StyleEldomiaty, Tarek, Islam Azzam, Jasmine Fouad, Hussein Mowafak Sadek, and Marwa Anwar Sedik. 2025. "Stochastic Uncertainty of Institutional Quality and the Corporate Capital Structure in the G8 and MENA Countries" Risks 13, no. 6: 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13060111

APA StyleEldomiaty, T., Azzam, I., Fouad, J., Sadek, H. M., & Sedik, M. A. (2025). Stochastic Uncertainty of Institutional Quality and the Corporate Capital Structure in the G8 and MENA Countries. Risks, 13(6), 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13060111