Abstract

In recent years, scholars have been paying more attention to financial inclusion, which has been positioned as a crucial component in accomplishing the majority of the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals set forward by the United Nations. Investigating the effects of life insurance and financial inclusion on poverty in 45 Sub-Saharan African (SSA) nations between 1999 and 2023 is the goal of this study. Using the Panel Autoregressive Distributed Lag (P-ARDL) method, this study concludes that poverty can be decreased through financial inclusion. Notably, we found that life insurance raises poverty when financial inclusion follows. This might be because there are not many microinsurance options available in SSA nations for those with low incomes. Due to their increased likelihood of being financially illiterate and their inability to purchase the necessary smart devices and internet services, the lower-income segments are unable to enjoy the same advantages as the higher-income segments. According to the findings, financial exclusion problems may be resolved by future life insurance, but this must be done in a sustainable manner. Future life insurance should address the requirements of the underprivileged and lower-income groups, and financial inclusion should be progressively enhanced.

1. Introduction

Financial inclusion is increasingly recognized as a critical driver of economic development, particularly in low-income countries. It refers to the process of ensuring that individuals and businesses have access to affordable and appropriate financial services, including savings accounts, loans, insurance, and payment systems (World Bank 2021). The importance of financial inclusion lies in its ability to empower marginalized populations, enabling them to manage their finances effectively, invest in opportunities, and protect themselves against economic shocks (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2022).

Microinsurance, a subset of financial services, specifically targets low-income individuals and micro-enterprises by providing affordable insurance products that cover various risks, such as health, life, property, and agricultural losses (Churchill and Matul 2021). By mitigating financial risks, microinsurance plays a crucial role in enhancing the resilience of low-income populations, helping them to safeguard their assets and livelihoods against unforeseen events (Morduch 2023).

Despite the recognized benefits of financial inclusion and microinsurance, many low-income countries face significant challenges in achieving the widespread penetration of these services. Barriers such as limited access to financial institutions, low financial literacy, high costs of services, and a lack of trust in formal financial systems hinder progress (Kumar and Singh 2023). Additionally, microinsurance products often suffer from low awareness and complex designs, making it difficult for potential clients to understand and adopt them (Bhatia and Kaur 2024). This study aims to explore the relationship between financial inclusion and life insurance in low-income countries, identifying key factors that influence this dynamic and the barriers that persist.

By elucidating these elements, the research seeks to inform policymakers and financial institutions on effective strategies to enhance financial inclusion and microinsurance uptake, ultimately contributing to poverty alleviation and economic resilience in vulnerable communities. Despite global advancements in financial inclusion, significant gaps persist in ensuring equitable access to financial services for low-income populations in many developing countries. A considerable portion of individuals in these regions remain unbanked, and the uptake of microinsurance—an essential financial tool for mitigating risks such as health emergencies, natural disasters, and crop failures—remains alarmingly low. For example, it is estimated that only 11.5 percent of the potential market for microinsurance in low-income countries is currently served, leaving a vast 88.5 percent protection gap.

The problem is compounded by systemic barriers, including limited financial literacy, inadequate digital infrastructure, and the high costs of delivering financial services to remote areas. Furthermore, cultural and institutional factors hinder the adoption of insurance products, leaving millions vulnerable to economic shocks. Studies show that women and other marginalized groups are particularly underserved, even as they represent a significant segment of the market that could benefit from targeted inclusive financial solutions (Munich Re Foundation 2021). Addressing these challenges is critical, as financial inclusion is closely linked to poverty alleviation and economic resilience. Understanding the interplay between financial inclusion efforts and micro life insurance is vital to designing policies and interventions that close the protection gap and support sustainable development in low-income countries (Center for Financial Inclusion 2024).

The fundamental basis of this study is as follows: many studies examine financial inclusion or insurance separately, but this study integrates both dimensions to assess their combined and individual impacts on poverty, offering a holistic understanding of the development of the financial sector in SSA. This approach captures complementarities and potential interaction effects between formal financial access and risk management through insurance—a relatively underexplored nexus in the existing literature. Most studies use shorter time spans or start their analysis post-2010 (after the introduction of Global Findex data). This study’s 25-year scope allows for an analysis of structural changes and financial sector reforms; an assessment of long-term trends and policy continuity or discontinuity; and the inclusion of the pre-mobile money and post-mobile money eras for comparison. Unlike global or multi-region studies, this research is context-specific to Sub-Saharan Africa, considering regional peculiarities such as low insurance penetration; high poverty levels; the rapid growth of digital financial services; unique institutional, regulatory, and socio-economic contexts; and the integration of poverty metrics as the core dependent variable. Many existing works treat financial inclusion or insurance as ends in themselves (e.g., determinants of inclusion). This study goes further by assessing their real impact on poverty alleviation, using direct poverty indicators as outcome variables, making the study strongly relevant to policy. The study also employs a panel estimation technique—Panel Autoregressive Distributed Lag (P-ARDL)—which allows us to address endogeneity issues, control for unobserved heterogeneity, and capture dynamic relationships; this represents a methodological advancement over simple OLS or the cross-sectional regressions used in some prior works. Many insurance-related studies in SSA aggregate life and non-life products. The research specifically isolates life insurance, which has greater potential for social protection, asset accumulation, and poverty mitigation, offering more targeted policy insights. By covering the period from 1999–2023, the study captures critical global events with implications for poverty, financial inclusion, and insurance: the 2008–2009 global financial crisis, the 2011–2015 mobile money explosion, and the COVID-19 pandemic. This allows for an analysis of resilience, shock absorption, and the adaptive role of financial tools during crises. This research stands out because it combines a long-term panel analysis, a dual-sector focus (financial inclusion and life insurance), and a poverty-alleviation lens within the SSA context, while applying advanced econometric tools and considering historical shocks and institutional changes—thereby filling a critical gap in the literature and offering evidence-based insights for inclusive financial development and social protection policy. The rest of the study is structured as follows: Section 2 presents a reviews of literatures that focused on the impacts of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries, Section 3 presents the results followed by Section 4 present discussion of the results where results were explained in details and lastly, Section 5 and Section 6 presents the data and methodology and the conclusions and policy implication of the of the study respectively.

2. Literature Review

Financial inclusion and micro life insurance are interconnected concepts that are critical to enhancing economic resilience and reducing poverty in low-income countries (LICs). Financial inclusion, defined as the access to and effective use of affordable financial services by underserved populations, forms the foundation for expanding microinsurance, a subset of inclusive insurance tailored to low-income individuals (World Bank 2021). Financial inclusion has been widely recognized as a driver of economic growth, enabling individuals to save, invest, and access credit and insurance. Inclusive financial systems contribute to economic development by fostering entrepreneurship, reducing vulnerability to financial shocks, and improving income distribution (Center for Financial Inclusion 2024). In LICs, financial inclusion efforts often focus on digitizing payment systems, promoting financial literacy, and developing regulatory frameworks that are conducive to innovation (Microinsurance Network 2023).

Microinsurance is a low-cost, scalable financial product designed to address risks faced by vulnerable populations, such as health emergencies, crop failures, and climate-induced disasters. The penetration of microinsurance in LICs remains low, with only 11.5 percent of the potential market covered in some regions (Microinsurance Network 2023). The concept emphasizes affordability, accessibility, and relevance, offering solutions such as weather-indexed crop insurance, community health insurance, and bundled financial products that include savings and insurance.

Financial inclusion plays a pivotal role in facilitating micro life insurance. A well-developed financial ecosystem allows for cost-efficient distribution channels, such as mobile money platforms, which reduce the administrative and transaction costs of insurance services. Mobile-based microinsurance initiatives, such as those implemented in Kenya through M-Pesa, exemplify how financial inclusion infrastructure enhances insurance accessibility (Munich Re Foundation 2021).

Conversely, microinsurance contributes to financial inclusion by building trust in formal financial institutions and encouraging participation in broader financial markets. When individuals experience the tangible benefits of microinsurance—such as receiving payouts during emergencies—they are more likely to adopt other financial services (Center for Financial Inclusion 2024).

The theoretical underpinnings of financial inclusion and microlife insurance are multifaceted, drawing from economic, behavioral, and developmental frameworks. These theories collectively emphasize the importance of reducing barriers, leveraging intermediaries, and addressing behavioral challenges to expand access to financial services in LICs. Future efforts to enhance financial inclusion and microinsurance should incorporate insights from these theories to design scalable, sustainable, and impactful solutions.

Financial inclusion initiatives align closely with the Theory of Financial Intermediation, which posits that financial institutions play a critical role in reducing transaction costs, managing risks, and bridging information asymmetries in markets. In LICs, microinsurance providers rely on intermediaries such as microfinance institutions (MFIs), mobile network operators, and community-based organizations to distribute affordable insurance products. These intermediaries enhance access by leveraging existing networks, particularly in underserved regions (World Bank 2021).

The Inclusive Growth Theory emphasizes the need for equitable economic growth that benefits all segments of society. Financial inclusion directly supports this theory by providing tools including savings, credit, and insurance to marginalized populations. Microinsurance, as a component of inclusive financial systems, ensures that vulnerable households can manage economic risks, preventing poverty traps and fostering more sustainable development (Microinsurance Network 2023). The protection afforded by microinsurance enables households to invest in productive assets and participate more fully in economic activities.

The paper is anchored around Diffusion of Innovations (DOI) Theory and Institutional Theory. The DOI explains how innovations (e.g., financial services or insurance products) are adopted over time by a population. Financial inclusion promotes the diffusion of financial literacy and digital tools, which may increase awareness and trust in insurance products. It is relevant to this study because insurance products, particularly microinsurance, represent innovations in low-income communities where financial inclusion initiatives such as mobile money pave the way for adoption. Moreover, institutional theory emphasizes the role of formal and informal structures (e.g., laws, norms, and organizations) in shaping behavior. Financial inclusion initiatives often rely on institutional reforms to improve financial and insurance market accessibility, as regulatory frameworks enabling mobile money and microinsurance are institutional changes that foster life insurance.

2.1. Empirical Review of the Relationship Between Financial Inclusion and Life Insurance

Empirical studies have explored the relationship between financial inclusion and life insurance in low-income countries (LICs). Financial inclusion was shown to be empirically linked to improved economic resilience, poverty reduction, and income equality in LICs.

Microinsurance, a key component of financial inclusion, has demonstrated its potential to improve financial resilience among low-income households. Empirical evidence from Ghana and other LICs indicates that microinsurance provides a critical safety net against economic shocks, such as health emergencies and agricultural losses. For example, parametric insurance models, which trigger payouts based on predefined indices such as rainfall levels, have been particularly effective in addressing rural risks. Despite these successes, the penetration rate remains low, with many LICs failing to exceed 12 percent market coverage due to affordability and infrastructure challenges (Microinsurance Network 2023).

2.1.1. Financial Inclusion and Life Insurance

The synergy between financial inclusion and microinsurance is evident in the empirical research. Studies reveal that mobile money platforms and digital financial services significantly enhance microinsurance distribution by lowering transaction costs and improving accessibility. In Kenya, the integration of microinsurance with mobile platforms such as M-Pesa has expanded coverage to previously unreachable demographics, illustrating the importance of leveraging digital infrastructure for inclusive insurance growth (Munich Re Foundation 2021; World Bank 2021).

Chummun (2017) investigated the relationship between mobile microinsurance and financial inclusion in developing countries. Through a review of literature, the author advances the hypothesis that inclusive financing is more likely to be successful in countries where mobile microinsurance is being used than in countries where the service is not available to low-income people. The study is predicated on the argument that mobile platforms including mobile money can be used as a measure to mitigate the inherent transaction costs of microinsurance and to assist in building the volume of microinsurance and mobile microinsurance policies. Despite some identified challenges, the findings revealed that leveraging the use of the relatively low-cost mobile channels of microinsurance could promote the effective accessibility of microinsurance, providing opportunities to reach low-income households in remote places and contribute to financial inclusion. Finally, the author points to some possible ways to mobilize mobile microinsurance to enable effective financial inclusion.

Mbugua (2021) conducted a study in Kenya that utilized a cross-sectional descriptive survey to analyze the impact of microinsurance on life insurance. Factors including client education, regulatory frameworks, and innovative distribution channels were found to drive microinsurance adoption. The research found that microinsurance strategies, including financial literacy education and the use of technology, significantly improved insurance uptake among low-income households. The study highlighted the importance of affordable and flexible premium payment options in enhancing access to microinsurance products.

Inyang and Okonkwo (2022) provided an integrative review of microinsurance schemes in Nigeria, identifying both opportunities and barriers to increasing life insurance. Their findings indicated that Nigeria’s insurance sector suffers from under-penetration, contributing less than one percent to GDP. This study highlights microinsurance’s potential to increase penetration, leveraging Nigeria’s demographics, regulatory frameworks, and insures advancements. Barriers such as low awareness and insufficient market research were identified, prompting recommendations for stakeholder initiatives and tailored microinsurance schemes. The authors emphasized the need for tailored products that meet the specific needs of low-income populations to improve engagement with microinsurance offerings.

Jain and Singh (2024) explored the transformative role of financial inclusion in the Indian insurance sector using a mixed-methods approach. Financial inclusion strategies have catalyzed growth and innovation in India’s insurance sector. Their review highlights how digital solutions and government-private initiatives have boosted penetration rates and product diversification. Their study also revealed that microinsurance not only serves as a safety net for low-income individuals but also encourages savings and investment in small enterprises. The research underscored the significance of financial literacy programs in enhancing the understanding and utilization of microinsurance among economically disadvantaged communities.

Jasintha and Mohan (2022) conducted a quantitative analysis to assess the impact of insurance inclusion on financial well-being in India. Their empirical findings demonstrated that households with access to microinsurance reported greater financial security and resilience against economic shocks. The study utilized a large sample size and employed statistical methods to analyze the data, confirming that microinsurance is vital for promoting financial inclusion and improving the overall economic stability of low-income households. The study notes that stagnant life insurance can be addressed using microinsurance products and technological integration, emphasizing the role of insurance in reducing vulnerabilities.

Kajwang’s (2022) study of microinsurance and poverty alleviation revealed that microinsurance is tailored for low-income groups, providing financial protection against risks while fostering resilience amidst vulnerabilities. The study used a desk research approach to evaluate its impact on poverty alleviation, finding that it protects the poor from shocks, supports gender-specific needs, and liberates household capital for small enterprises. The author recommends increased government support, insurance literacy campaigns, and innovative strategies to raise awareness of microinsurance’s benefits.

Mose (2022) addressed Kenya’s low life insurance rate of 2.43 percent by exploring microinsurance strategies such as financial literacy, technological adoption, and product flexibility. Based on descriptive surveys, the findings highlighted that microinsurance positively influences penetration through customer education and innovative distribution methods. The study recommends stronger public–private partnerships to expand microinsurance. Anusha (2020) connected financial and insurance inclusion, focusing on microinsurance’s role in spreading financial services to rural areas. It suggests that policies aimed at simultaneous financial and insurance inclusion can enhance equity and drive sustainable growth, particularly in underserved areas.

Overall, the empirical evidence highlights the significant relationship between financial inclusion and micro life insurance in low-income countries. Studies consistently emphasize the importance of client education, tailored product offerings, and supportive regulatory frameworks in enhancing access to microinsurance. Integrating microinsurance into broader financial inclusion strategies is essential for fostering economic resilience among vulnerable populations.

2.1.2. Financial Inclusion and Poverty

Lal (2018) examined the impact of financial inclusion on poverty alleviation. In order to fulfil the objectives of the study, primary data were collected from 540 beneficiaries of cooperative banks operating in three northern states of India, i.e., J&K, Himachal Pradesh (HP) and Punjab, using purposive sampling during the period from July–December 2015. The technique of factor analysis was used to summarize the complete dataset into minimum factors. To check the validity and reliability of the data, the second-order CFA was performed. Statistical techniques such as one-way ANOVA, t-tests, and SEM were used for the data analysis. The study results reveal that financial inclusion through cooperative banks has a direct and significant impact on poverty alleviation. The study highlights that access to basic financial services such as savings, loans, insurance, credit, etc., through financial inclusion generates a positive impact on the lives of the poor and helps them to escape the clutches of poverty.

Tran and Le (2021) examined the financial inclusion–poverty nexus of 29 European nations between 2011 and 2017. Based on panel data from 29 European nations between 2011 and 2017, 2SLS and GMM regressions revealed that financial inclusion has a negative effect on poverty at all three poverty lines of USD 1.9, USD 3.2, and USD 5.5 per day. All three levels of POV1.9, POV3.2, and POV5.5 are negatively impacted by the percentage of the population between the ages of 15 and 64, as well as the ratio of service employment to total employment. On the other hand, the percentage of people aged 25 and older who completed at least secondary school, GDP per capita, and trade openness all positively affect poverty at all three levels.

Tran et al. (2022) assessed how financial inclusion affected multifaceted poverty reduction, particularly with regard to household use of financial products and services. Their study estimates the impact of financial inclusion on household use of financial products and services, as well as other factors, on multidimensional poverty using a multivariate probit model with a Vietnamese dataset. The findings demonstrate that multifaceted poverty is decreased by financial inclusion. In particular, households are less likely to experience multidimensional poverty if they have bank accounts, save at banks, use credit or debit cards, or invest in stocks or bonds. In light of these results, we provide a number of suggestions to legislators in an effort to boost household usage of financial services and products.

Sakanko (2023) used primary data gathered from 624 questionnaires to examine the effect of financial inclusion on poverty reduction in 224 towns and villages spread over 12 Local Government Areas in Niger State, Nigeria. To this end, the study used the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation techniques along with the logistics regression and Probit regression models. The findings show that while age has a negative impact on financial inclusion in Niger State, gender, education, literacy, income, social security, and phone availability are all important positive drivers of financial inclusion. Furthermore, the OLS results show that, while the literacy rate shows a position that reduces income, account ownership, bank access, social security access, and employment all have a favorable impact on income levels.

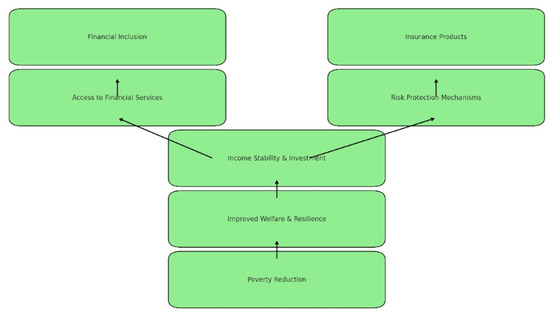

In summary, to best of the knowledge of the authors, there exist no empirical studies directly examining the moderating effect of life insurance on the financial inclusion–poverty nexus; this, therefore, forms the crux of this research. Figure 1 presents the diagram illustrates the conceptual framework showing how financial inclusion and life insurance products contribute to poverty reduction through mediating channels. The Initial Inputs: Financial Inclusion: Access to and usage of formal financial services (e.g., banking, credit, savings) and life Insurance Products: Insurance schemes providing coverage against life risks, helping to secure family income in case of loss. These two factors influence the mediating Channels. Secondly, the mediating Channels: these channels serve as the mechanisms or pathways through which financial inclusion and insurance influence outcomes. The diagram below shows the mediating node influencing two key outcomes: income growth & Stability and Risk Mitigation & Protection. Thirdly, Secondary Outcomes: Income Growth & Stability: Reflects increased, predictable, and secure income flows due to improved financial access and safety nets. Risk Mitigation & Protection: Involves managing economic shocks (e.g., death, illness, job loss) more effectively. These outcomes converge to lead to: Final Outcome: Poverty Reduction: The end goal, achieved through improved income and reduced vulnerability to shocks. In Summary, Financial Inclusion and Life Insurance Products → Mediating Channels → Income Growth & Stability + Risk Mitigation & Protection → Poverty Reduction. This framework is likely part of a research model analyzing how inclusive finance and insurance mechanisms can structurally reduce poverty, particularly relevant in developing or low-income country contexts (Anifowose and Chummun 2025).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework: impact of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty. Source: Created by Authors (2024).

3. Results

The summary of statistics is important to exploring the time-series distribution of the data collected for each of the variables. Table 1 indicates that all variables used as endogenous variables for poverty are positive. This reveals the average for all the endogenous variables. For instance, the mean distribution of the poverty reduction in SSA indicates that, in SSA countries, poverty is reduced as a result of the joint impacts of joint impacts of financial inclusion and life insurance.

Table 1.

Summary of descriptive statistics for the joint impacts of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa from 1999Q1 to 2023Q4.

Table 2 presents the correlation matrix of the variables used in the model. The correlation matrix shows the degree of association and direction of relationships among the variables. The results in the table show that there exists a negative relationship among poverty, financial inclusion, life insurance, interactive term of financial inclusion and life insurance (FIInsur), inflation, trade openness (TOP), and growth. It can be deduced that all independent variables can be included in the same model without the fear of multicollinearity.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix for the joint impacts of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa 1999Q1 to 2023Q4.

Various studies (Anifowose et al. 2019) have advised researchers to always use more than one method of panel unit root testing in order to be sure of the order of integration of the variables to be included in a particular model. The reason behind this might be connected to the fact that a non-stationary variable constitutes an outlier among other variable and the inclusion can significantly influence the outcome of the empirical analysis. For this study, both the ADF and PP methods of panel unit root tests are adopted for consistency’s sake. The results are presented in Table 3. Table 3 presents the panel unit root for the joint impacts of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa from 199Q1 to 2023Q4.

Table 3.

Panel unit root test for the joint impacts of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa 1999Q1 to 2023Q4.

After identifying the order of integration of the variables, the next step was to determine whether the variables share a long-run equilibrium relationship. For this test, the Pedroni residual cointegration test is used to determine whether a set of non-stationary time series are cointegrated, meaning that they share a long-term equilibrium relationship despite potential short-term fluctuations. Table 4 present the Pedoni panel cointegration test result for the model.

Table 4.

Pedroni panel cointegration test results.

The panel PP statistic and panel ADF statistic strongly reject the null hypothesis, suggesting the existence of cointegration. Additionally, the panel v statistic and panel rho statistic fail to reject the null hypothesis, but these are less powerful in many cases compared to the PP and ADF statistics. Based on the significant panel PP statistic and panel ADF statistic, there is evidence to suggest that the series are cointegrated, meaning they share a long-term equilibrium relationship. Further analysis, such as estimating the long-term relationship using an error correction model (ECM), can provide insights into the dynamics among these variables. Table 5 present the long-run form along with the bound test of the model.

Table 5.

Impact of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty in SSA countries.

4. Discussion

This research used the P-ARDL technique to measure the impact of financial inclusion. Table 5 resents the ARDL bounds test and the associated error correction model for determining the short-run and long-run relationships between poverty (POV) and several explanatory variables.

The coefficients in the “levels equation” reveal the long-term effects of the independent variables on poverty reduction (POV). The coefficient for FII (−3.05) indicates that an increase in the financial inclusion index (FII) is associated with a reduction in poverty. However, this result is not statistically significant (p = 0.498). This insignificance may stem from low financial literacy in Sub-Saharan African countries, which limits the ability of low-income earners to effectively and efficiently access financial services. Additionally, the result may reflect the broader impact of financial inclusion on different income groups, rather than exclusively benefiting the low-income segment, thereby diluting its specific effect on poverty reduction. The result is similar to the findings of (Turegano and Herrero 2018).

The coefficient for life insurance (INSUR) is significant and positive (coef. = 17.51, p < 0.01), suggesting that higher insurance levels contribute significantly to poverty reduction in the long run. This finding aligns with the results of Chummun (2017). However, the interactive term of financial inclusion and insurance performance (FIINSUR) is not statistically significant (p = 0.542), contrasting with the findings of Chummun (2017).

The inflation coefficient (0.0937) implies a weak and insignificant effect of inflation on poverty reduction (p = 0.1613). Trade openness (TRADEOPP) shows no significant relationship (p = 0.725). Economic growth (GRO) has a significant negative effect (coef. = −0.0113, p = 0.0322). This might suggest that, while GDP per capita increases, poverty reduction does not proportionally follow due to inequality or other factors. The constant term Constant (C) (25.42) represents the baseline level of poverty reduction when all variables are at zero.

The error correction term, POV (−1), has a significant negative coefficient (−0.5808, p < 0.001), confirming the presence of a long-run relationship. The adjustment speed is 58.08 percent, meaning that over half of any short-run disequilibrium is corrected in the next period. Key short-run effects include the following. D(FII): positive effect (coef. = 11.10, p = 0.0291), indicating a short-run benefit of financial inclusion. D(INSUR) showed mixed results; while the initial effect is positive (coef. = 7.63, p = 0.0326), the lagged terms are negative and significant, suggesting dynamic effects over time. D(FI_INSUR) had a significantly negative impact across lags, implying that the interaction between financial inclusion and life insurance may introduce complex and potentially detrimental short-term dynamics. D(INFLATION) had a positive and significant effect (coef. = 0.265, p < 0.001), highlighting a short-term inflationary boost to poverty reduction. (GRO) had an insignificant effect (p = 0.4171). This is similar to findings of (Ilori and Ilori 2025; Oke et al. 2023).

5. Materials and Methods

This section presents the methodology for investigating the effect of life insurance on financial inclusion in SSA countries. Data for this study were obtained from the World Bank Global Financial Development Database and the World Bank Development Indicators Database. The period from 1999–2023 captures the emergence and evolution of financial inclusion and life insurance markets, coinciding with the global poverty reduction agenda, technological innovation, and data availability, making it a methodologically sound and policy-relevant period for studying their impacts on poverty in SSA countries. Additionally, reliable data on financial inclusion (e.g., account ownership, mobile money usage) began to be collected more systematically in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with substantial improvements after 2010 through sources including the Global Findex Database (first launched in 2011) and the World Bank financial access surveys; moreover, data on insurance products, particularly life insurance, became more readily available for SSA countries around the late 1990s through Swiss Re, AXCO, and national insurance commissions. Lastly, comprehensive poverty data (e.g., poverty headcount ratio, poverty gap) from the World Bank PovcalNet and other global databases are more consistently available from 1999 onward. The period of 1999–2023 aligns with key global and regional development agendas, such as poverty reduction strategies (PRSPs) adopted by many SSA governments in the early 2000s; the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 2000–2015, with poverty eradication as a core goal; and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2015–2030, especially Goal 1 (No Poverty) and Goal 8 (Inclusive Growth and Financial Access). This period allows for an analysis of how financial inclusion and insurance intersect with these broader developmental goals. Table 6 presents the names of the data and corresponding proxies for their measurement along with the reliable data sources.

Table 6.

Data proxies, variable measurements, and sources.

Econometric Model Specification

The variables included in the model specification are calibrated in line with the work of (Wong et al. 2023) to investigate the moderating effect of life insurance on the relationship between financial inclusion and poverty in SSA countries, as follows:

where INSUR is life insurance and is the interaction term between financial inclusion and life insurance. This interaction term is expected to indicate the impact of life insurance on the relationship between financial inclusion and poverty. At the margin, the total effects of life insurance can be calculated by examining the partial derivative of poverty with respect to financial inclusion.

This equation reveals the marginal effect of financial inclusion on poverty changes, with defined with respect to the level of life insurance. The sign of coefficient of the interaction term shows its moderating effect. However, if is negative and the interactive term coefficient has a positive sign, it indicates that a rise in life insurance would enhance the negative impact of financial inclusion on poverty. If and are negative, this indicates that life insurance retards the positive effects of financial inclusion on poverty. Table 7 presents the theoretical sign of the variables in the model.

Table 7.

Variables expected theoretical sign.

6. Conclusions

This study explored how life insurance may moderate the relationship between financial inclusion and poverty, indicating that financial inclusion and life insurance products have a positive and insignificant impact on poverty in Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries. It suggests that, while these factors may be associated with poverty reduction, their effects are not strong or statistically reliable. This implies that there is limited penetration and usage: that is, financial inclusion and life insurance might not be widespread or effectively utilized by the poor. Many individuals may have access to financial services but do not actively use them in ways that significantly reduce poverty. Second, there is low financial literacy; people might not fully understand or trust financial services, including life insurance, leading to underutilization or misuse. Third, the study indicates that there exist short-term versus long-term effects; that is, the benefits of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty reduction might take longer to materialize, and the study period may not have captured the long-term effects. Furthermore, there could be structural constraints such as other economic and institutional factors (i.e., weak governance, corruption, or inadequate infrastructure) that limit the effectiveness of financial services in reducing poverty, as well as insurance design issues. In other words, life insurance, in particular, may not directly alleviate poverty in the short term, as the benefits are often realized only upon death or after long periods. If policies are not tailored to the needs of the poor, their impact may be minimal. Moreover, there could be credit usage and indebtedness i.e., if financial inclusion primarily increases access to credit without corresponding productive investments, it may not significantly reduce poverty and, in some cases, could lead to over-indebtedness.

In conclusion, there could be measurement and data limitations; the insignificant impact could also be due to data limitations or methodological issues in the study, such as small sample sizes or omitted variable bias. Future research could consider investigating additional potential moderators that could strengthen this relationship. For example, financial literacy might serve as a significant moderator, as a better understanding and awareness of financial products and services could enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of their use, particularly among lower-income segments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.L.A.; Methodology, O.L.A.; Formal analysis, O.L.A.; Writing—original draft, O.L.A.; Writing—review & editing, O.L.A. and B.Z.C.; Supervision, B.Z.C.; Funding acquisition, B.Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data were sourced from World Bank Global Financial Development Database and World Bank Development Indicators Database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anifowose, Oladotun L., Adeleke Omolade, and Mukorera Sophia. 2019. Determinants for BRICs Countries Military Expenditure. Acta Universitatis Danubius. Œconomica 15: 165–90. [Google Scholar]

- Anifowose, Oladotun Larry, and Bibi Zaheenah Chummun. 2025. A Panel Data Analysis of Determinants of Financial Inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) Countries from 1999 to 2024. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18: 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusha, N. 2020. Insurance Inclusion: A Tool for Financial Inclusion in India. Available online: https://mcom.sfgc.ac.in/downloads/2020/20.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Bhatia, M., and R. Kaur. 2024. Challenges in microinsurance adoption: A study of low-income populations. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 29: 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Financial Inclusion. 2024. Inclusive Insurance: Closing the Protection Gap for Emerging Customers. Available online: https://www.centerforfinancialinclusion.org (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Chummun, Bibi Z. 2017. Mobile microinsurance and financial inclusion: The case of developing African countries. Africagrowth Agenda 2017: 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, Craig, and Michal Matul. 2021. Microinsurance: Targeting the Poor. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, Asli, Leora Klapper, and Dorothe Singer. 2022. Financial inclusion and the role of digital finance. World Bank Economic Review 36: 345–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ilori, David Babafemi, and Morounke Adeseye Ilori. 2025. Supply-side factors and financial inclusion of micro, small and medium enterprises in southwest, Nigeria. Abjournals 8: 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Inyang, Uduakobong, and Ikeotuonye Victor Okonkwo. 2022. Microinsurance schemes and life insurance in Nigeria: An integrative review. The Journal of Risk Management and Insurance 26: 60–74. Available online: https://jrmi.au.edu/index.php/jrmi/article/view/243 (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Jain, Mukesh Kumar, and Divya Singh. 2024. A Review on Enhancing Insurance Accessibility in India: The Transformative Role of Financial Inclusion. International Journal of Poverty, Investment and Development 3: 13–22. Available online: https://www.ijprems.com/uploadedfiles/paper/issue_3_march_2024/32813/final/fin_ijprems1709980781.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Jasintha, V. L., and S. Mohan. 2022. Insurance for financial inclusion and well-being. Journal of Positive School Psychology 6: 3989–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kajwang, Ben. 2022. Influence of microinsurance access on poverty alleviation. International Journal of Poverty, Investment and Development 3: 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A., and R. Singh. 2023. Barriers to financial inclusion in developing economies: A systematic review. International Journal of Financial Studies 11: 12–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, Tarsem. 2018. Impact of financial inclusion on poverty alleviation through cooperative banks. International Journal of Social Economics 45: 808–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbugua, Douglas K. 2021. Effect of Microinsurance Growth on Life Insurance in Kenya. Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Microinsurance Network. 2023. The Landscape of Microinsurance 2023. Available online: https://microinsurancenetwork.org/resources/the-landscape-of-microinsurance-2023 (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Morduch, J. 2023. The role of microinsurance in poverty alleviation: Evidence from low-income countries. Development Policy Review 41: 321–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mose, Stellah. 2022. Microinsurance as a Strategy in Enhancing Life Insurance in Kenya. Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Munich Re Foundation. 2021. The Landscape of Microinsurance 2021. Available online: https://www.munichre-foundation.org (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Oke, Dorcas, Rosemary Soetan, and Taiwo Ayedun. 2023. Financial Inclusion and the Performance of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in Southwest Nigeria. Paper presented at the 29th RSEP International Conference on Economics, Finance & Business, Barcelona, Spain, February 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Sakanko, Musa Abdullahi. 2023. A State-Level Impact Analysis of Financial Inclusion and poverty reduction in Nigeria. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Abuja, Abuja, Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, Huong Thi Thanh, and Ha Thi Thu Le. 2021. The impact of financial inclusion on poverty reduction. Asian Journal of Law and Economics 12: 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Huong Thi Thanh, Ha Thi Thu Le, Nga Thanh Nguyen, Tue Thi Minh Pham, and Huyen Thanh Hoang. 2022. The effect of financial inclusion on multidimensional poverty: The case of Vietnam. Cogent Economics & Finance 10: 2132643. [Google Scholar]

- Turegano, David Martinez, and Alicia Garcia Herrero. 2018. Financial inclusion, rather than size, is the key to tackling income inequality. The Singapore Economic Review 63: 167–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Zhian Zhiow Augustinne, Ramez Abubakr Badeeb, and Abey P. Philip. 2023. Financial inclusion, poverty, and income inequality in ASEAN countries: Does financial innovation matter? Social Indicators Research 169: 471–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2021. Financial Inclusion: A Global Perspective. World Bank Publications. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).