1. Introduction

Firm performance is one of the most vital indicators of long-term success, and reflects the efficiency, effectiveness, and competitiveness of an organisation. This includes crucial financial and non-financial information used to make strategic and sustainable decisions (

Aifuwa 2020;

Pang and Lu 2018). In addition, while financial figures offer a snapshot of a company’s short-term economic performance, non-financial performance (NFP) metrics and indicators are now acknowledged as crucial determinants of an organisation’s longer-term viability and strength. NFP offers greater insight as to how well-positioned it is for future growth. Often, these attributes empower competitive advantage (CA), enhance brand reputation, and harbour a resilient and flexible company culture. NFP is a methodology that focuses on one of the most important aspects for companies today: how well firms do on non-financial ‘metrics’ such as sustainability, social responsibility, and stakeholder relationships. Thus, in an era of strong corporate social responsibility and stakeholder governance, embedding NFP into holistic Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) is crucial for achieving a balanced, long-lasting organisation (

Vasile et al. 2022). Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) is a holistic framework that integrates risk identification, assessment, and response across all organisational levels (

COSO 2004). For insurance companies—whose business model is inherently centred on risk—ERM provides strategic tools to enhance non-financial performance such as customer satisfaction, employee engagement, and service quality.

Insurance companies are classified as financial institutions. However, they also play an essential role in economic and social development through the revenues generated, known as insurance premiums, which individuals and corporations pay for insurance coverage. These premiums are then invested in various industries to generate a return. In the Omani context, the Capital Market Authority (CMA), now known as the Financial Services Authority (FSA), regulates the insurance sector and requires each insurance company to report its information and financial figures quarterly to the regulator. The 2021–2022 Insurance Market Index, which was published in 2023, indicates that there are 19 insurance companies regulated in Oman, with 10 of them regarded as national companies and thus categorised under listed public shareholding companies. The insurance sector includes 30 officially licensed insurance brokers and 161 insurance agents. The insurance market comprises gross written premiums (GWP) of OMR 541.326 million, equivalent to approximately USD 1.4 billion.

An ERM system is typically seen as equipping organisations with the frameworks and structures needed for resilience and competence and to address the aftermath of crises that have led to the collapse of major companies across sectors across the globe (

Jalilvand and Moorthy 2023). Several studies claim that adopting ERM practices improves firm performance (

COSO 2017;

Malik et al. 2020;

Paape and Speklé 2012;

Phan et al. 2020). Usable ERM practices can provide a Competitive Advantage and help companies grow (

Blanco-Mesa et al. 2019). A study conducted by

Anton and Nucu (

2020) using a large sample set from 2008 to 2019 indicated that firm performance is the most studied topic in ERM.

However,

Simon et al. (

2015) indicated that several key Non-Financial Performance (NFP) indicators are influenced by effective ERM, such as customer satisfaction and retention, employee engagement and satisfaction, operational efficiency, innovation and adaptability, the quality of services, and stakeholder trust and relationships. In recent years, linking these key Non-Financial Performance (NFP) outcomes to comprehensive ERM programs has emerged as a significant determinant of the success and longevity of organisations.

Despite the abundance of earlier research on the effects of ERM in small- and medium-sized businesses, there have been comparatively few studies on ERM deployment in insurance companies, particularly in developing countries (

Anton and Nucu 2020). Given the increasing growth of ERM issues, additional studies should be conducted to evaluate the impact of ERM procedures on organisational performance to identify fresh evidence (

Alajmi 2019). Most Omani organisations lack awareness and focus on ERM and its principles. In addition, their adoption is still in its early stages (

Al-Farsi 2020).

With the increasing complexity of firm processes, ERM has become an essential management function (

Quang et al. 2024). The various crises around the world, pandemics, terrorism, the emergence of new technology, and major geopolitical upheavals are just a few of the many external threats companies face. Technological disruption, human error, constantly changing client needs, and uncertain resources (human, financial, and material) are problems in risk management. Most of these factors were present several decades ago. We are witnessing the emergence of a complex infrastructure and communication environment that represents a novel evolution of systems unprecedented in human experience. ERM practices should keep up with these changes by implementing new and more flexible methodologies (

Bakos and Dumitrașcu 2021).

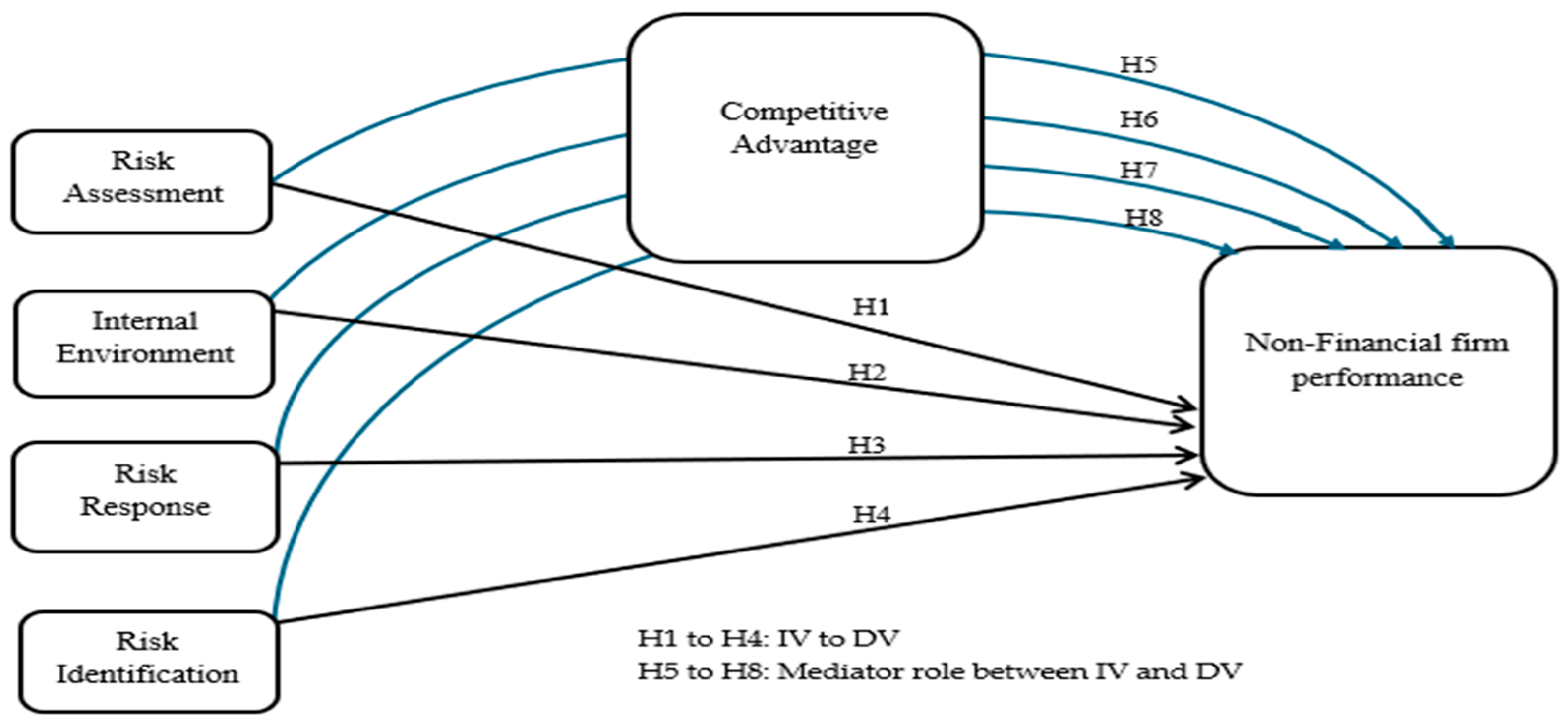

The relationship between ERM practices and NFP is not a simple, direct relationship. Instead, it is important to understand the dynamics of the Competitive Advantage as a mediator between ERM and NFP. Competitive Advantage is a powerful enabler of ever-increasing business differentiation, boosting the ability of ERM to convert to real-world NFP value. While a mature ERM framework, by its very nature, reduces risk and strengthens operational resilience, the applied leverage of Competitive Advantage strategically ensures that these inherent positives have strong explanatory power in accounting for this multifaceted phenomenon. The concept of Competitive Advantage within the context of the ERM-NFP process enables organisations to elucidate better how ERM practices can lead to ongoing organisational success. This is consistent with the Resource-Based View (RBV) theory, which argues that firms can achieve a Competitive Advantage by harnessing unique and valuable resources within the firm that cannot be easily replicated or copied. Bridging Competitive Advantage into ERM processes enables organisations to transform risk management from a reactive mechanism to a proactive, performance-enhancing mechanism, further solidifying its position in the long-term sustainability framework. Understanding this threefold connection helps enrich theoretical discussions. It provides a practical basis for decisions related to management, which is particularly useful for aligning risk management issues with the organisation’s broader objectives.

In this aspect, Competitive Advantage acts as a strategic enabler of ERM practices, not just a risk-mitigating process; ERM practices also act as organisational competitors and NFP-driving mechanisms. Incorporating Competitive Advantage considerations directly into ERM strategies enables firms to realign their focus from a reactive posture where risk management only serves to mitigate harm, towards proactively exploiting opportunities linked to risk within the organisational structure, providing a powerful lever for firms to leverage their risk management efforts more effectively, reinforce their market position, and safeguard their long-term viability in a complex and dynamic marketplace.

In light of this consideration, this study contributes to the literature by providing new evidence on the associations between ERM and NFP, particularly with regard to the relatively new development of ERM in the Omani insurance sector. While prior studies have mostly focused on financial outcomes, this study introduces Competitive Advantage as a mediator, reinforcing the ERM-NFP relationship. The empirical results from the PLS-SEM analysis of 439 responses indicated that ERM had a positive influence on NFP, with Competitive Advantage partially mediating this relationship. This study extends resource-based view (RBV) theory by showing that Competitive Advantage translates into greater risk management benefits, advising firms seeking long-term resilience. On an applied these results to provide guidance for insurers and policymakers on strategically approaching ERM as a means of improving competitiveness and sustainability. This study addresses a significant gap in the literature by highlighting the non-financial outcomes of ERM and establishing a pathway for future ERM research in developing economies and across various industries.

With the increasing complexity of firm processes, ERM has become an incredibly important, if immature, management function (

Quang et al. 2024). Various crises, technological disruptions, and uncertain resources have challenged firms. ERM practices should adapt to these changes with flexible methodologies (

Bakos and Dumitrașcu 2021). Establishing an ERM system enhances resilience, enabling firms to manage crises (

Jalilvand and Moorthy 2023) effectively. Several studies have highlighted the role of ERM in enhancing firm performance and Competitive Advantage (

Malik et al. 2020;

Phan et al. 2020).

Despite growing global interest in Enterprise Risk Management, empirical evidence from emerging economies and from the insurance sector remains limited (

Anton and Nucu 2020;

Eastman et al. 2024). Existing studies have concentrated primarily on financial outcomes, leaving the effects of ERM on non-financial performance indicators—such as customer satisfaction, service quality, and employee engagement—largely underexplored. Moreover, the potential mediating role of Competitive Advantage (CA) in translating ERM practices into performance gains has received minimal empirical attention, especially within the context of Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and Oman in particular. This study addresses these gaps by investigating how ERM practices affect non-financial performance in Omani insurance companies and by testing CA as a mediating mechanism. To our knowledge, this is among the first studies to provide firm-level evidence on these relationships within the Omani insurance industry, thereby offering both theoretical and practical contributions. Many Omani companies are not widely aware of or adopting ERM (

Al-Farsi 2020). Non-Financial Performance (NFP) is becoming crucial for assessing firms in addition to financial figures (

Vasile et al. 2022). Poor ERM negatively affects customer satisfaction, employee engagement, and innovation (

Simon et al. 2015). The positive impact of ERM-NFP on Competitive Advantage occurs both directly and indirectly (

Saeidi et al. 2020;

Quang et al. 2024). The ERM-CA-NFP relationships enlighten firms on how to become resilient and strategically competitive.

3. Research Methodology

This quantitative, correlational, and objective survey-based study explores the relationships between independent, mediating, and dependent variables. The reasoning behind such methodology relates to

Ponto (

2015), who declares that this kind of methodology allows researchers to provide quantity and connections between variables. In contrast, they can use different ways of questioning.

Sekaran and Bougie (

2016) recommend including all logical decision-making options in the research design.

Determining an appropriate sample size is crucial, as it is often impractical to collect data from the entirety of a population due to constraints related to time, financial resources, and the human effort required for data collection. Consequently,

Sekaran and Bougie (

2016) and

Zikmund et al. (

2013) advocate using sampling methods rather than including the entire population in research endeavours. Additionally, utilising a representative sample enhances the credibility of the study’s findings, with a generally acceptable sample size ranging from 30 to 500, contingent on the type of research conducted (

Sekaran and Bougie 2016).

The target population of this study consists of the employees of insurance companies in Oman, totalling 2167 individuals across top, middle, and operational management positions. A total of 600 questionnaires were distributed to employees across all 19 licensed insurance companies (10 national and 9 foreign branches) as listed by the Financial Services Authority (

FSA 2023). Of these, 439 usable responses were returned, resulting in a response rate of 73.2%. This nationwide approach ensured representation of the full diversity of the Omani insurance market rather than a single firm. The survey was administered electronically through Google Forms and distributed to all firms with prior approval from the National Centre for Statistics & Information. This population encompasses all employment levels, including top, middle, and operational management positions, as defined by the 2021–2022 Insurance Market Index, published in 2023, regarding premium volumes.

Top management includes employees in C-level positions such as Chief Executive Officer (CEO), Chief Financial Officer (CFO), Chief Operating Officer (COO), and Chief Risk Officer (CRO). These positions are critical for decision-making, policy development, and stakeholder management. Middle management is represented by department managers, branch managers, and customer service managers, who serve as a vital link between executives and staff. They are responsible for translating strategic goals into operational objectives and directing teams towards their achievement.

Operational management refers to clerks, customer service personnel, and front office staff who handle the day-to-day operational functions of the organisation (

Mintzberg 1979). According to

Krejcie and Morgan (

1970), the appropriate sample size for this population is calculated to be 327 respondents; however, the actual data collection yielded responses from 439 individuals.

Saunders et al. (

2019) affirmed that a larger sample size of 439 enhances the robustness of statistical analyses, particularly when considering potential outliers (

Saunders et al. 2019).

The questionnaire was prepared for insurance companies in Oman. The Capital Market Authority (CMA), now called the Financial Services Authority (FSA), is the supervisor and regulator of these companies, responsible for ensuring compliance with the law, protecting policyholders, and maintaining stability in the insurance market by setting standards through policies and guidelines. In addition to limited audits of insurance companies to guarantee their adherence to legal frameworks, and issuing circulars on a regular basis, the FSA monitors compliance with a variety of companies. The questionnaire was developed with carefully written items and operational definitions for each variable to ensure respondents understood their meaning. The questionnaire was translated into Arabic and English via professional legal translation firms, with the back-translation process ensuring accuracy (as shown in

Table S1 in Supplementary Materials).

The electronic questionnaire, developed using Google Forms, incorporates an introductory video that outlines the research objectives prior to respondents engaging with the survey. This link has received prior approval from the National Centre for Statistics & Information in Oman, as it pertains to data collection within the region for a duration of six months. The Financial Services Authority (FSA) has disseminated the survey link to insurance companies in Oman, requesting that they circulate it among their employees within a one-week timeline. Engagement with employers addressed their inquiries concerning the study, successfully conveying the necessity and significance of this research. No biases were identified against respondents, as each employer directly communicated with their employees through mass emails sent to all staff. This study employed a convenience sampling method, facilitating relative ease in accessing respondents whom their respective employers have systematically coordinated. This methodology was deemed appropriate given that the researcher exerted neither influence nor control over employees’ willingness to participate in the study.

3.1. Data Collection, Population, and Respondents

This study employs a customised questionnaire based on the established literature on ERM practices, CA, and organisational performance. Population: Omani insurance company participants. A 5-point Likert scale is used to measure the study variables, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). This scale was chosen because of its flexibility in capturing multiple nuanced responses to specific questions.

This study complied with all applicable ethical standards. Prior to data collection, ethical clearance was obtained from the National Centre for Statistics & Information (NCSI) in Oman (Approval No. 12/2024). All respondents were informed about the purpose of the research and assured that participation was entirely voluntary. Informed consent was obtained electronically before the survey began, and participants were guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality of their responses. No identifying personal data were collected, and all data were used solely for academic purposes.

3.2. Measurement of the Study’s Variables

3.3. Multiple Regression Analysis

The study utilised multiple regression analysis (a multivariate statistical technique) to evaluate the hypothesised relationships between dependent variables and several independent and predictive variables. This analysis method is particularly suitable for studies with a dependent variable expected to serve as the subject of the independent, mediating, and moderating variables. Established as a method of description, multiple regression summarises and describes the linear relationships between independent mediators or mediating and moderating variables on a dependent variable and was used in this study to clarify how the study’s variables relate to and with each other cumulatively (

Hair et al. 2010). While this study applies PLS-SEM to model latent constructs and examine mediation effects, we acknowledge the limitation of this approach in establishing causality. Future studies could benefit from adopting econometric techniques such as instrumental variable regressions to mitigate endogeneity and strengthen causal claims (

Dionne et al. 2018).

4. Findings

4.1. Data Analysis and Findings

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) is a robust analysis tool that offers effective epidemic and path modelling estimation, as well as non-linear relation performance. In datasets with a large number of indicators and non-normal distributions, the latter method has advantages for theory testing (

Hair et al. 2021;

Kock 2015). Data cleaning and preprocessing were performed using SPSS (ver. 23.0), where common method bias and linearity checks were conducted to ensure high data quality. Hypothesis testing was conducted using SmartPLS 4, one of the most advanced software packages used for testing complex relationships to validate the proposed theoretical model. Maintaining a strict analysis and enhancing the validity of the outputs.

4.2. Common Method Bias (CMB)

The study rigorously assessed common method bias (CMB) using both Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) and inner Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values to ensure the validity of the findings. As per

Nitzl (

2016), CMB may be indicated when the correlations between primary constructions exceed 0.90. In this study, all HTMT correlation values were below this threshold, with the highest value recorded at 0.846 (refer to the HTMT table), confirming that CMB was not a concern. Additionally, inner VIF values were analysed to detect any potential multicollinearity issues, where values exceeding 3.30 suggest model contamination. This study’s highest inner VIF value was 2.569 (refer to the structural model assessment table), well below the recommended threshold outlined by

Kock (

2015). These findings collectively confirm that CMB did not pose a significant issue in this research.

4.3. Intercorrelations of the Study Variables

Table 1 shows the study variables’ means, standard deviations (SD), and intercorrelations. The Internal Environment (IE) had a mean score of 2.484 (SD = 1.248), indicating that participants perceived internal environment practices within their organisations as neutral to somewhat positive. Risk Assessment (RA) had the highest mean value (2.485, SD = 1.159), indicating that respondents showed relatively stronger agreement than the other variables, while Risk Response (RR) had the lowest mean value (2.433, SD = 1.107). Given that the study has utilised a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree), a mean score around 2.5 can be interpreted as indicating a neutral to slightly positive perception, emphasising that participants neither strongly disagreed nor strongly agreed with the survey statements. This interpretation is supported by previous studies, which have defined Likert mean scores from 2.0 to 3.0 as representing neutral to moderate agreement levels (

Boone and Boone 2012). However, all variables had statistically significant positive relationships with Non-Financial Firm Performance (NFP) at the

p < 0.01 level, which strongly suggests the existence of positive relationships between ERM practices, competitive advantage, and non-financial performance. The Means, SD, and Correlations of the study variables can be seen in

Table 1.

4.4. Demographic Profile of the Respondents

The demographic profile revealed a diverse sample, with Arabic speakers (64.94%) and males (58.77%) forming the majority. Job positions were well distributed across operational (47.15%), middle (36.67%), and top management (16.17%). Experience levels varied, with 34.62% having over 15 years of experience. Although gender, age, education, job position, and experience data were collected and are reported here to characterise the sample, these demographic factors were not entered as control variables in the structural equation model because the primary objective was to test the relationships among ERM, CA, and NFP.

Most respondents worked in established companies (51.94% older than 15 years) with large workforces (43.96% having more than 200 employees). The educational qualifications were primarily degrees (37.81%) and diplomas (32.80%). This diversity strengthens the validity and generalizability of the study, offering a comprehensive view of the target population.

The respondent profile revealed a diverse sample, featuring varied language preferences, gender distribution, job positions, experience levels, company characteristics, and educational qualifications. This demographic diversity strengthens the validity and generalizability of the study, offering a comprehensive representation of the target population.

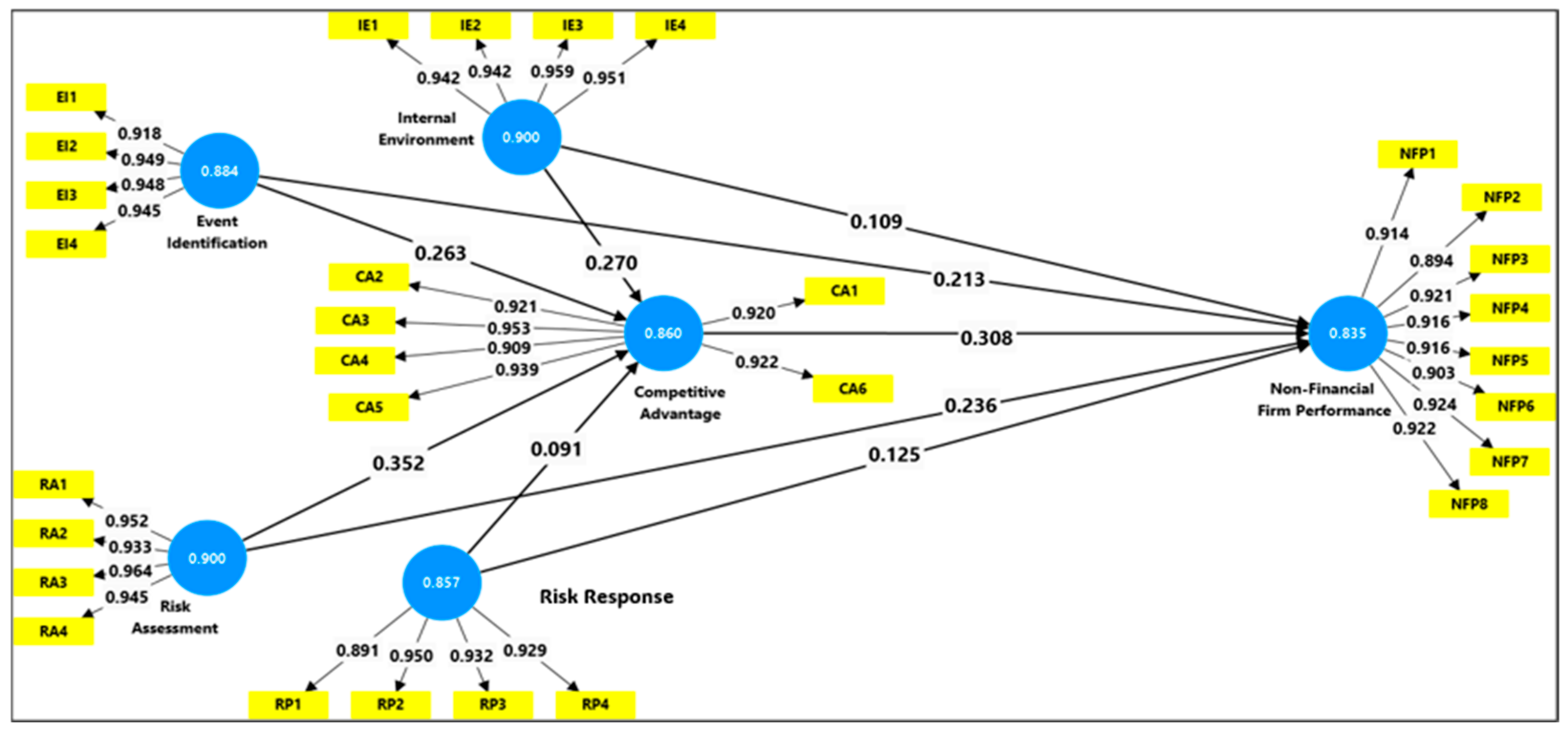

4.5. Evaluation of Measurement Model (Outer Model)

To ensure the reliability and validity of our study constructs, we conducted rigorous internal consistency tests using two widely accepted measurement models: calculated composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha (CA). As shown in

Table 2, the internal consistency of all constructs was excellent, with Composite Reliability (CR) > 0.7 and Cronbach’s alpha (CA) > 0.7. These results affirm the strong reliability of the constructs (

Hair et al. 2021). Furthermore, all items had factor loadings (FLs) above the 0.70 margin, establishing a robust correlation with the latent variables.

Chin (

1998) and

Hair et al. (

2021). These results unequivocally confirm the validity of the measurement model.

Having met the relevant threshold criteria (i.e., factor loadings, Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Cronbach’s alpha (CA), and composite reliability (CR)), we tested the constructs for discriminant validity using two established methods: the Fornell-Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT). The diagonal cells in

Table 3 are the square roots of the AVE values, and the correlations are below. Based on the Fornell–Larcker criterion (

Fornell and Larcker 1981), we compared the square root of AVE values with the appropriate correlations, as shown in

Figure 2. The diagonal represents the square root of AVE, and the diagonal values are always more significant than the correlations below them. These findings provide compelling evidence that discriminant validity has been achieved according to the parameters set forth by the Fornell–Larcker criterion, reinforcing the robustness of our study.

The off-diagonal values are the correlations between latent variables, and the diagonal is the square root of AVE.

The discriminant validity of the constructs was also evaluated using the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) criterion, as suggested by

Henseler et al. (

2015). Our analysis demonstrated that all correlation values among the constructs were below 0.9, indicating satisfactory levels of discriminant validity. This outcome aligns with the threshold recommended by

Henseler et al. (

2015). Specifically, in

Table 4, the highest observed HTMT value is 0.846, confirming that no significant concerns regarding discriminant validity were identified. Consequently, the measurement model demonstrated acceptable discriminant validity to confirm that each of the constructs is empirically distinct.

4.6. Assessment of Structural (Inner) Model

After thoroughly evaluating the measurement model, we assessed collinearity, the coefficient of determination (R

2), and effect size within the structural model. This involved analysing R

2 values, f

2 values, and the inner Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), as illustrated in

Table 5 and

Table 6, respectively. The results met the recommended thresholds for R

2, f

2, and the inner VIF, thus confirming the model’s robustness and reliability. Using these criteria, we examined the outcomes of the hypothesis testing.

The R

2 values for Competitive Advantage (CA) of 0.795 and for Non-Financial Performance (NFP) of 0.818 indicate that the model explains a significant percentage of the variance in these constructs. The significant R

2 also exceeds the

Cohen (

1989) benchmark of 0.26, which suggests adequate explanatory power of the model. The following is a summary of the effect sizes (f

2) and examines potential collinearity concerns through VIF values.

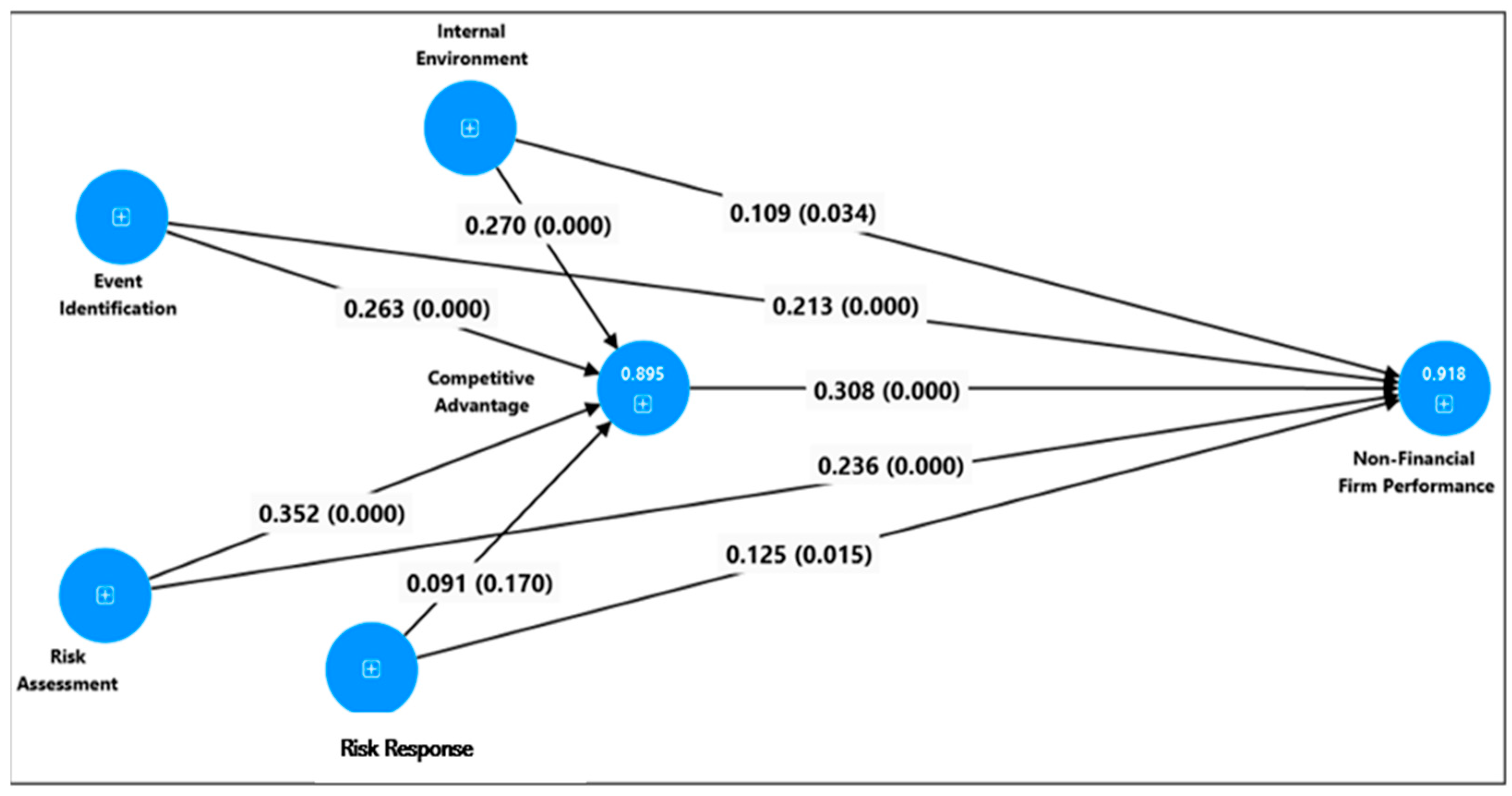

4.7. Hypotheses Testing Results

Figure 3 and

Table 7 present the results for the proposed hypotheses derived from bootstrapping with 10,000 resampling iterations. Hypothesis 1 (H1), which examined the direct relationship between the Internal Environment (IE) and Non-Financial Performance (NFP), yielded statistically significant results (

p = 0.034), confirming a significant relationship. The

t-value of 2.121 exceeded the critical threshold of 1.96, and the positive beta value (0.109) indicated a significant positive effect of the Internal Environment (IE) on Non-Financial Performance (NFP).

Hypothesis 2 (H2), investigating the direct relationship between Event Identification (EI) and Non-Financial Performance (NFP), also showed significant results (p = 0.000, t = 4.118, beta = 0.213), demonstrating a positive effect of Event Identification (EI) on Non-Financial Performance (NFP).

Hypothesis 3 (H3), assessing the direct relationship between Risk Assessment (RA) and Non-Financial Performance (NFP), produced significant findings (p = 0.000, t = 5.184, beta = 0.236), highlighting the positive effect of Risk Assessment (RA) on Non-Financial Performance (NFP).

Hypothesis 4 (H4), exploring the direct relationship between Risk Response (RR) and Non-Financial Performance (NFP), revealed statistically significant results (p = 0.015, t = 2.451, beta = 0.125), indicating a positive effect of Risk Response (RR) on Non-Financial Performance (NFP).

Hypothesis 5 examined the mediating role of Competitive Advantage in the relationship between IE and NFP, with findings supporting this hypothesis (p = 0.000, t = 3.664). The confidence intervals for the indirect effects (LL = 0.048, UL = 0.138) excluded zero, confirming significant partial mediation by CA.

Hypothesis 6 tested the mediating effect of Competitive Advantage on the relationship between EI and NFP, and the results supported this hypothesis (p = 0.006, t = 2.741). The confidence intervals (LL = 0.038, UL = 0.153) excluded zero, affirming a significant partial mediation by CA.

Hypothesis 7, which evaluated the mediating effect of Competitive Advantage on the relationship between Risk Assessment (RA) and NFP, also found support (p = 0.000, t = 4.134), with confidence intervals (LL = 0.066, UL = 0.166) excluding zero, confirming significant partial mediation.

However, Hypothesis 8, examining the mediating effect of Competitive Advantage in the relationship between Risk Response (RR) and NFP, was not supported. The p-value (0.176) exceeded 0.05, the t-value (1.355) fell below 1.96, and the confidence intervals (LL = −0.010, UL = 0.074) included zero, indicating no significant mediation.

The results of the PLS-SEM analysis reveal that all four ERM dimensions—Internal Environment, Event Identification, Risk Assessment, and Risk Response—have positive and statistically significant effects on Non-Financial Performance (NFP). Among these, Risk Assessment exhibits the strongest positive path coefficient, indicating that a systematic evaluation of potential threats enhances service quality and customer satisfaction more than other ERM components. Furthermore, Competitive Advantage (CA) partially mediates the positive relationships of Internal Environment, Event Identification, and Risk Assessment with NFP, confirming that ERM improves organisational capabilities, which in turn drive superior non-financial outcomes. In contrast, the indirect effect of Risk Response through CA is positive but not significant, suggesting that this dimension influences NFP primarily through its direct pathway (as shown in

Figure 3).

4.8. Discussion of Findings

This study provides significant empirical support for all eight hypotheses examining the relationship between ERM and NFP in the Omani insurance industry. The results demonstrate that the internal environment, event identification, risk assessment, risk response, and Competitive Advantage are significantly and positively associated with NFP. These findings contribute to the growing evidence on ERM and its organisational relevance, particularly in emerging economies.

The positive impact of the internal environment on NFPs aligns with the study’s findings of

Nyagah’s (

2014). However, it contrasts with

Yakob et al. (

2019) and

Alawattegama (

2018), highlighting the importance of context-specific ERM implementation. This discrepancy underscores the need for greater awareness of the effectiveness of ERM to vary across organisational and contextual lenses. The impact of event identification on NFP is consistent with the findings of both

Jaber (

2020) and

Saeidi et al. (

2019), underscoring the importance of systematic risk consciousness for organisational performance improvement.

The benefits of risk assessment based on the NFP are consistent with those of

Suttipun et al. (

2019) and

Shahrin and Ibrahim (

2021), who stress its critical importance in strategic decision-making. This differs from

Nyagah (

2014), who found a negative relationship, likely due to differences in organisational uptake of risk assessment into their processes. The positive effect of risk response on NFP is aligned with

Saeidi et al. (

2019). However, it is remarkably different from

Yakob et al. (

2019), reflecting the specific culture of risk response that underpins the Omani insurance industry.

This study’s significant contribution is that it shows the competitive advantage to be a significant mediator variable between these ERM practices and the NFP. This finding aligns with the research conducted by

Ricardianto et al. (

2023) and

Saeidi et al. (

2020), which found that ERM is more effective in the presence of CA, especially in developing economies. This study, which examines the potential role of mediation, whereas

Florio and Leoni (

2017) did not, offers a more fine-grained understanding of how ERM impacts organisational performance.

Pagach and Warr (

2010) found mixed support for the impacts of ERM; however, the current study provides strong evidence of such on non-financial measures in a developing setting. These findings affirm

Muslih (

2019) that ERM has a positive transformative potential in emerging markets. This study incorporates the Resource-Based View (

Wernerfelt 1984) to emphasise the empirical relationship between the strategic alignment of ERM with organisational resources to achieve NFP.

This study advances understanding of the multidimensional benefits of ERM by presenting a comprehensive framework that aligns ERM practices with competitive strategies. The findings provide practical guidance for insurance practitioners and policymakers, particularly in developing economies. As ERM continues to evolve, future research could extend these insights through longitudinal designs, cross-industry comparisons, and mixed-methods approaches to capture its long-term effects. The mediation analysis further reveals that Competitive Advantage (CA) positively and significantly mediates the relationships of Internal Environment, Event Identification, and Risk Assessment with Non-Financial Performance (NFP), indicating that ERM strengthens organisational capabilities—such as resource coordination and strategic flexibility—that drive superior non-financial outcomes. However, the mediation pathway for Risk Response is not significant, suggesting that its influence on NFP occurs primarily through direct effects rather than via CA.

In conclusion, this study significantly enhances the body of knowledge on ERM by investigating the impact of ERM on NFP and establishing the mediating role of the CA. These findings underscore the strategic importance of ERM implementation in enhancing organisational resilience and performance, especially in dynamic and evolving business environments. The findings contribute to theory building and, at a practical level, provide insights for practitioners seeking to enhance their organisations’ competitive advantage through implementing ERM systems. Consequently, the results offer strong empirical support for the proposed model and demonstrate the importance of ERM practices to improve competitive advantage and non-financial performance.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary and Conclusions

This study confirms that ERM practices contribute to better non-financial performance among Omani insurers and that Competitive Advantage plays a partial mediating role in this relationship. Specifically, CA transmits the positive effects of Internal Environment, Event Identification, and Risk Assessment to NFP, underscoring the Resource-Based View proposition that unique organisational resources transform risk management capabilities into measurable performance gains.

The findings indicate that Competitive Advantage (CA) acts as a significant mediator linking Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) practices to Non-Financial Performance (NFP). PLS-SEM results show that CA partially mediates the effects of Internal Environment, Event Identification, and Risk Assessment on NFP (

p < 0.01). In contrast, the mediation path from Risk Response to NFP through CA is not significant (

p = 0.176). CA is strongly correlated with NFP (r = 0.933) and demonstrates a meaningful effect size (f

2 = 0.221), suggesting that ERM-driven competitive advantage enhances a firm’s resilience and market position through its corporate image, service quality, and stakeholder trust. Although PLS-SEM is appropriate for predictive modelling with complex latent constructs, the nesting of respondents within 19 insurance firms raises the possibility of firm-level clustering effects. Because PLS-SEM does not readily accommodate multilevel structures, formal adjustments for intra-class correlation were not feasible. Future studies should apply multilevel SEM or hierarchical modelling to account for firm-level variance and validate these relationships further (

Hair et al. 2017). These results align with prior research (

Nyagah 2014;

Jaber 2020;

Saeidi et al. 2019) while highlighting contextual differences noted by

Yakob et al. (

2019) and

Alawattegama (

2018). By integrating the Resource-Based View (

Wernerfelt 1984), the study underscores the strategic alignment of ERM with organisational resources to drive non-financial outcomes, supporting evidence from

Ricardianto et al. (

2023),

Saeidi et al. (

2020), and

Muslih (

2019) on ERM’s transformative potential in emerging markets.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

The findings offer several actionable insights for Omani insurers, industry regulators, and policymakers. First, the positive and significant relationships between ERM practices and non-financial performance suggest that regulators such as the Financial Services Authority (FSA) should encourage or mandate the adoption of integrated ERM frameworks, providing technical guidelines and training to ensure consistent implementation across the industry. Second, insurers should integrate ERM into their strategic planning and decision-making processes, moving beyond compliance to leverage ERM as a source of competitive advantage. This includes cross-departmental risk committees, scenario planning, and continuous staff training on risk awareness and communication. Third, industry associations could develop benchmarking tools and an ERM maturity index to allow firms to monitor progress and share best practices. These measures would not only strengthen risk governance within individual companies but also enhance the overall stability and reputation of the Omani insurance sector, supporting the broader goals of Oman Vision 2040.

5.3. Limitations

Despite its important contributions, this study also has some limitations that should be addressed in future studies. Limited generalizability focuses on a single sector within a specific culture. On the other hand, self-reported data may be biased, which could call into question the credibility of the results. In order to address all of these shortcomings and elaborate further on the contributions of this study, future (empirical) research should, among others, consider studying ERM practices across various sectors in order to increase the generalizability of the results, study the interplay between the emerging technologies and ERM practices, study ERM practices cross-nationally within developed and developing economies, conduct longitudinal studies that investigate whether ERM practices can be positively sustained over time, and finally focus on the human capital aspect of ERM to provide insights into long-term pay-offs for the company and optimisation of competitive positioning within its sector.

While demographic data such as gender, age, education, and job position were collected, these variables were not incorporated as control factors in the PLS-SEM analysis. Future studies may benefit from including these demographics as control or moderating variables to account for potential heterogeneity among respondents and to validate the robustness of the relationships observed in this study.

5.4. Future Research Directions

Future research should investigate the development of a comprehensive ERM index that encompasses all four dimensions of ERM to evaluate the overall maturity of risk management practices. An index of this nature could enhance comparisons across firms and industries, support benchmarking of ERM implementation, and provide greater insights into the impact of integrated risk management on organisational performance. Future research may focus on creating a composite ERM index to evaluate overall maturity, investigate potential moderators like organisational culture, and broaden the analysis to include other GCC countries for cross-market comparisons.