Impact of Audit Fees on Earnings Management and Financial Risk: An Analysis of Corporate Finance Practices

Abstract

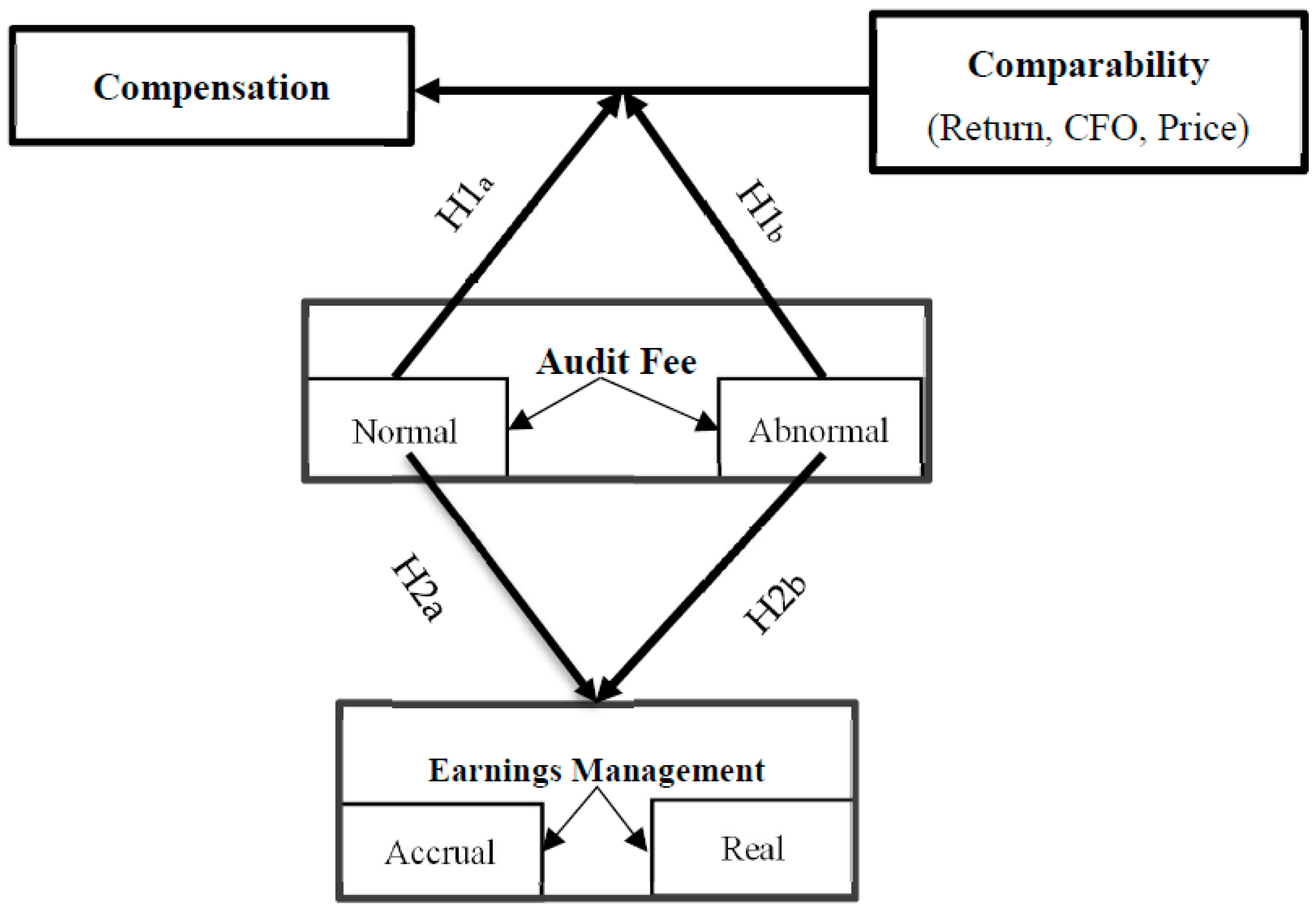

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

4. Empirical Models and Econometrics Results

- CFO(i,t) is cash flow from operations divided by beginning total assets.

- NI(i,t) is net income after deducting the current year’s tax divided by the beginning total assets.

- RETURN(i,t): Annual stock return of the firm i in the current year.

- NI/P(i,t): Net income after deducting tax per share in the current year divided by the beginning share price for firm i.

- ΔNI/P(i,t): Changes in net income per share in the current year compared to the previous year divided by the beginning share price for firm i.

- LOSS(i,t): An artificial measure of a firm’s loss. If the firm is unprofitable, it equals one. Otherwise, it equals zero.

- Price(i,t): Closing price per share in the current year.

- NIPS(i,t): Net income after deducting tax per share for firm i in the current year.

- BVPS(i,t): Book value of the shareholder’s equity per share at the end of the period for firm i.

5. Findings

6. Discussion

- Highlighting the role of audit fees: This study underscores the influence of audit fees on financial reporting quality and risk management.

- Providing empirical evidence: We demonstrate the asymmetric effects of normal and abnormal audit fees on earnings management.

- Emphasising balanced audit fee structures: The need for balanced audit fee structures to ensure financial transparency and mitigate risk is evident from our findings.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antle, Rick, Elizabeth Gordon, Ganapathi Narayanamoorthy, and Ling Zhou. 2006. The joint determination of audit fees, non-audit fees, and abnormal accruals. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 27: 235–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asthana, Sharad C., and Jeff P. Boone. 2012. Abnormal audit fee and audit quality. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 31: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, Mary E., Wayne R. Landsman, Mark H. Lang, and Christopher D. Williams. 2018. Effects on comparability and capital market benefits of voluntary IFRS adoption. Journal of Financial Reporting 3: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Abdelaziz, Fouad, Souhir Neifar, and Khamoussi Halioui. 2022. Multilevel optimal managerial incentives and audit fees to limit earnings management practices. Annals of Operations Research 311: 587–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankley, Alan I., David N. Hurtt, and Jason E. MacGregor. 2012. Abnormal audit fees and restatements. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 31: 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou, Jer-Shiou, and Yi-Chieh Lee. 2011. Efficiency and profitability of biotech-industry in a small economy. International Journal of Business and Commerce 1: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Jong-Hag, Sunhwa Choi, Linda A. Myers, and David Ziebart. 2019. Financial statement comparability and the informativeness of stock prices about future earnings. Contemporary Accounting Research 36: 389–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Brant E., Nathan J. Newton, and Michael S. Wilkins. 2021. How do team workloads and team staffing affect the audit? Archival evidence from US audits. Accounting, Organisations and Society 92: 101225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryaei, Abbas Ali, and Yasin Fattahi. 2020. The asymmetric impact of institutional ownership on firm performance: Panel smooth transition regression model. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 20: 1191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryaei, Abbas Ali, Yasin Fattahi, Davood Askarany, Saeed Askary, and Mahdad Mollazamani. 2022. Accounting Comparability, Conservatism, Executive Compensation-Performance, and Information Quality. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechow, Patricia M., and Ilia D. Dichev. 2002. The quality of accruals and earnings: The role of accrual estimation errors. The Accounting Review 77 s-1: 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechow, Patricia M., Richard G. Sloan, and Amy P. Sweeney. 1991. Detecting earnings management. Accounting Review 70: 193–225. [Google Scholar]

- Donatella, Pierre, Mattias Haraldsson, and Torbjörn Tagesson. 2019. Do audit firms and audit costs/fees influence earnings management in Swedish municipalities? International Review of Administrative Sciences 85: 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshleman, John Daniel, and Peng Guo. 2014. Abnormal audit fees and audit quality: The importance of considering managerial incentives in tests of earnings management. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 33: 117–38. [Google Scholar]

- Eshleman, John Daniel, and Peng Guo. 2020. Do seasoned industry specialists provide higher audit quality? A re-examination. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 39: 106770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, Yasin, Gholamreza Kordestani, and Abbas Ali Daryaei. 2021. Impact of Accounting Comparability according to the Peer Firms on Board Compensation. Budget and Finance Strategic Research 2: 11–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Michael J., Gim S. Seow, and Danqing Young. 2004. Non-audit services and earnings management: UK evidence. Contemporary Accounting Research 21: 813–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). 2010. Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 8: Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting. Norwalk: Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, Richard M., Marilyn F. Johnson, and Karen K. Nelson. 2002. The relation between auditors’ fees for non-audit services and earnings management. The Accounting Review 77: 71–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandía, Juan L., and David Huguet. 2021. Audit fees and earnings management: Differences based on the type of audit. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 34: 2628–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Andrés, and Timo Teräsvirta. 2006. Simulation-based finite sample linearity test against smooth transition models. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 68: 797–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Junjian, and Dan Hu. 2015. Audit fees, earnings management, and litigation risk: Evidence from Japanese firms cross-listed on US markets. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal 19: 125. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Bruce E., and Byeongseon Seo. 2002. Testing for two-regime threshold cointegration in vector error-correction. Journal of Econometrics 110: 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, Paul M. 1985. The effect of bonus schemes on accounting decisions. Journal of Accounting and Economics 7: 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, Hassan, Salih Turan Katircioğlu, and Lesyan Saeidpour. 2015. Economic growth, CO2 emissions, and energy consumption in the five ASEAN countries. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 64: 785–91. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, Andrew D., and James W. Fredrickson. 2001. Top management team coordination needs and the CEO pay gap: A competitive test of economic and behavioral views. Academy of Management Journal 44: 96–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Jennifer J. 1991. Earnings management during import relief investigations. Journal of Accounting Research 29: 193–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalelkar, Rachana, Yuan Shi, and Hongkang Xu. 2024. Top management team incentive dispersion and audit fees. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance 35: 178–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kashmiri, Hawazin. 2014. Testing accruals-based earnings management models in an international context: A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Business Studies in Accountancy degree at Massey University, Albany, New Zealand. Ph.D. dissertation, Massey University, Albany, New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- Kasznik, Ron. 1999. On the association between voluntary disclosure and earnings management. Journal of Accounting Research 37: 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, Sagar P., Andrew J. Leone, and Charles E. Wasley. 2005. Performance-matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of Accounting and Economics 39: 163–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Nian Lim, Mohamed Sami Khalaf, Magdy Farag, and Mohamed Gomaa. 2024. The impact of critical audit matters on audit report lag and audit fees: Evidence from the United States. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, Gerald J., Michael Neel, and Adrienne Rhodes. 2018. Accounting comparability and relative performance evaluation in CEO compensation. Review of Accounting Studies 23: 1137–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNichols, Maureen F. 2002. Discussion of the quality of accruals and earnings: The role of accrual estimation errors. The Accounting Review 77: 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, Santanu, Donald R. Deis, and Mahmud Hossain. 2009. The association between audit fees and reported earnings quality in pre-and post-Sarbanes-Oxley regimes. Review of Accounting and Finance 8: 232–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Jonathan. 2020. Financial reporting comparability and accounting-based relative performance evaluation in the design of CEO cash compensation contracts. The Accounting Review 95: 343–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namakavarani, Omid Mehri, Abbas Ali Daryaei, Davood Askarany, and Saeed Askary. 2021. Audit committee characteristics and quality of financial information: The role of the internal information environment and political connections. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridzky, M., and F. Fitriany. 2022. The Impact of Abnormal Audit Fees on Audit Quality: A Study of ASEAN Countries. KnE Social Sciences, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, Mohamed A., and Yasmine M. Ragab. 2023. Determining audit fees: Evidence from the Egyptian stock market. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management 31: 355–75. [Google Scholar]

- Santos Jaén, José Manuel, Gema Martín de Almagro Vázquez, and María del Carmen Valls Martínez. 2023. Is earnings management impacted by audit fees and auditor tenure? An analysis of the Big Four audit firms in the US market. Oeconomia Copernicana 14: 899–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, Ahmed A., and Christopher J. Cowton. 2024. Combatting bribery and corruption: Does corporate anti-corruption commitment lead to more or less audit effort? In Accounting Forum. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Shandiz, Mohsen Tavakoli, Farzaneh Nassir Zadeh, and Davood Askarany. 2022. The Interactive Effect of Ownership Structure on the Relationship between Annual Board Report Readability and Stock Price Crash Risk. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehadeh, Ayman, Mahmoud Daoud Daoud Nassar, Husam Shrouf, and Mohammad Haroun Sharairi. 2024. How Audit Fees Impact Earnings Management in Service Companies on the Amman Stock Exchange through Audit Committee Characteristics. International Journal of Financial Studies 12: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simunic, Dan A. 1980. The pricing of audit services: Theory and evidence. Journal of Accounting Research 18: 161–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonu, Catherine Heyjung, Hyejin Ahn, and Ahrum Choi. 2017. Audit fee pressure and audit risk: Evidence from the financial crisis of 2008. Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics 24: 127–44. [Google Scholar]

- Utomo, St Dwiarso, and Zaky Machmuddah. 2023. Governance Disclosure, Integrated Reporting, CEO Compensation, Firm Value. In World Conference on Information Systems for Business Management. Singapore: Springer Nature, pp. 303–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Huiyu, Jincheng Fang, and Haoyu Gao. 2023. How FinTech improves financial reporting quality? Evidence from earnings management. Economic Modelling 126: 106435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocki, Peter. 2010. Corporate compensation policies and audit fees. Journal of Accounting and Economics 49: 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, Farzaneh Nassir, Davood Askarany, and Solmaz Arefi Asl. 2022. Accounting Conservatism and Earnings Quality. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Honghui, Hedy Jiaying Huang, and Ahsan Habib. 2018. The effect of tournament incentives on financial restatements: Evidence from China. The International Journal of Accounting 53: 118–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Computation for the Year 2010–2019 | Firms | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total population Less: | 533 | 100 |

| Firms inactive between 2010–2019 | (189) | (35) |

| Financial services firms | (52) | (10) |

| Firms that did not provide complete information | (48) | (9) |

| Firms that were admitted to the stock market from 2010 | (80) | (15) |

| Final sampled firms | 164 | 31 |

| Variables | Mean | Median | Max | Min | Std | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMPENSATE | 4.534 | 6.291 | 12.004 | 0.000 | 3.394 | 1640 |

| COMP_CFO | −0.072 | −0.062 | −0.006 | −0.255 | 0.035 | 1640 |

| COMP_RET | −0.120 | −0.105 | −0.025 | −0.504 | 0.061 | 1640 |

| COMP_PRC | −5047.168 | −3422.600 | −1.514 | −42,814.63 | 5044.544 | 1640 |

| SQR | 22.816 | 24.000 | 42.000 | 0.000 | 6.651 | 1640 |

| CORR_ROA | 0.367 | 0.701 | 1.000 | −1.000 | 0.689 | 1640 |

| CORR_CF | 0.200 | 0.384 | 0.999 | −0.999 | 0.706 | 1640 |

| CORR_RET | 0.457 | 0.787 | 1.000 | −1.000 | 0.648 | 1640 |

| INDHERF | 0.221 | 0.245 | 0.482 | 0.000 | 0.124 | 1640 |

| SIZE | 13.819 | 13.614 | 19.374 | 9.797 | 1.571 | 1640 |

| BM | 0.515 | 0.418 | 1.974 | −1.559 | 0.409 | 1640 |

| LEV | 0.588 | 0.563 | 1.363 | 0.012 | 0.214 | 1640 |

| ROA | 0.170 | 0.145 | 0.803 | −0.729 | 0.156 | 1640 |

| ADJROA | 0.002 | −0.003 | 0.563 | −0.938 | 0.135 | 1640 |

| RET | 0.106 | 0.093 | 0.989 | −0.997 | 0.317 | 1640 |

| ADJRET | 0.001 | −0.009 | 1.092 | −1.200 | 0.284 | 1640 |

| GROWTH | 0.194 | 0.161 | 1.460 | −0.964 | 0.327 | 1640 |

| DIVYIELD | 0.105 | 0.078 | 0.809 | 0.000 | 0.114 | 1640 |

| RETVOL | 0.218 | 0.186 | 0.768 | 0.002 | 0.141 | 1640 |

| CFVOL | 0.076 | 0.061 | 0.619 | 0.000 | 0.060 | 1640 |

| EM_ACC | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.900 | −0.699 | 0.103 | 1640 |

| ABAFEE | −0.003 | 0.001 | 2.700 | −2.657 | 0.655 | 1640 |

| LAF | 6.620 | 6.731 | 9.606 | 2.928 | 1.362 | 1640 |

| NFEE | 6.624 | 6.514 | 8.860 | 4.683 | 1.207 | 1640 |

| Panel A | Panel B | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | ANOVA (F) | Kruskal-Wallis (χ2) | t-Statistics |

| COMPENSATE | 16.071 *** | 308.324 *** | 497.251 *** |

| COMP_RET | 12.011 *** | 256.126 *** | 519.336 *** |

| COMP_RET | 19.203 *** | 318.874 *** | 609.562 *** |

| COMP_PRC | 17.305 *** | 128.347 *** | 437.164 *** |

| SQR | 23.622 *** | 547.824 *** | 692.3216 *** |

| CORR_ROA | 14.459 *** | 361.213 *** | 806.228 *** |

| CORR_CF | 18.154 *** | 327.267 *** | 659.450 *** |

| CORR_RET | 11.240 *** | 471.289 *** | 647.330 *** |

| INDHERF | 14.642 *** | 241.478 *** | 708.029 *** |

| SIZE | 11.246 *** | 502.545 *** | 415.260 *** |

| BM | 14.913 *** | 139.115 *** | 558.116 *** |

| LEV | 11.315 *** | 207.831 *** | 352.283 *** |

| ROA | 12.459 *** | 336.643 *** | 549.686 *** |

| ADJROA | 18.914 *** | 327.267 *** | 553.628 *** |

| RET | 10.210 *** | 471.289 *** | 967.044 *** |

| ADJRET | 15.642 *** | 141.478 *** | 953.812 *** |

| GROWTH | 11.246 *** | 502.555 *** | 977.738 *** |

| DIVYIELD | 14.130 *** | 139.115 *** | 604.402 *** |

| RETVOL | 11.243 *** | 207.831 *** | 466.964 *** |

| CFVOL | 14.910 *** | 236.643 *** | 557.470 *** |

| EM_ACC | 13.246 *** | 241.873 *** | 539.182 *** |

| ABAFEE | 13.031 *** | 539.551 *** | 604.402 *** |

| LAF | 15.142 *** | 377.381 *** | 664.694 *** |

| NFEE | 13.019 *** | 362.346 *** | 575.074 *** |

| Models | R2 (Adj) | F Statistic | AIC (1) | SC (2) | HQC (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jones (1991) | 0.309 | 3.774 | −1.232 | −0.823 | −1.136 |

| Dechow et al. (1991) | 0.386 | 3.716 | −1.125 | −0.833 | −1.068 |

| Kasznik (1999) | 0.567 | 11.582 | −1.310 | −0.957 | −1.105 |

| Dechow and Dichev (2002) | 0.510 | 9.202 | −1.186 | −0.733 | −1.081 |

| McNichols (2002) | 0.586 | 12.162 | −1.344 | −0.984 | −1.136 |

| Kothari et al. (2005) | 0.293 | 3.665 | −0.919 | −0.426 | −0.814 |

| Variable | COMP_CFO | COMP_RET | COMP_PRC |

|---|---|---|---|

| COMP_CFO | 6.287 ** (3.043) | − | − |

| COMP_RET | − | 2.739 *** (0.744) | − |

| COMP_PRC | − | − | 3.86 × 10−5 *** (1.48 × 10−5) |

| ABAFEE | 0.267 (0.226) | −0.160 * (0.089) | 0.065 (0.054) |

| ABAFEE * COMP_CFO | 5.434 (2.858) | − | − |

| ABAFEE * COMP_RET | − | −0.722 (0.707) | − |

| ABAFEE * COMP_PRC | − | − | 2.14× 105 *** (8.15× 10−6) |

| CORR_ROA | 0.105 (0.106) | 0.059 (0.049) | 0.069 (0.042) |

| CORR_CF | −0.119 (0.103) | −0.044 (0.045) | −0.066 (0.041) |

| CORR_RET | 0.109 (0.117) | 0.035 (0.057) | 0.022 (0.047) |

| INDHERF | −2.124 (1.862) | −2.300 * (1.176) | −3.015 *** (1.004) |

| SIZE | 0.642 *** (0.076) | 0.365 *** (0.044) | 0.691 *** (0.038) |

| BM | 0.493 ** (0.226) | 0.120 (0.111) | 0.072 (0.105) |

| LEV | 1.391 ** (0.542) | 0.558 ** (0.247) | 0.476 ** (0.222) |

| ROA | 0.462 (1.282) | 1.011 * (0.609) | 0.277 (0.533) |

| ADJROA | 3.210 ** (1.280) | 0.805 (0.610) | 1.596 *** (0.504) |

| RET | 1.659 *** (0.406) | 0.503 *** (0.180) | 0.595 *** (0.161) |

| ADJRET | −1.466 *** (0.444) | −0.504 ** (0.207) | −0.664 *** (0.176) |

| GROWTH | −0.213 (0.236) | −0.020 (0.109) | −0.025 (0.097) |

| DIVYIELD | 1.356 ** (0.736) | 0.903 ** (0.389) | 0.977 *** (0.367) |

| RETVOL | 1.324 (0.552) | 0.573 ** (0.246) | 0.459 ** (0.226) |

| CFVOL | 0037 (1.278) | 0.282 (0.612) | 0.594 (0.457) |

| Hausman Test () | 32.619 | 39.004 | 39.860 |

| R2 (Adj) | 0.504 | 0.862 | 0.899 |

| F statistic | 7.627 *** | 47.029 *** | 67.487 *** |

| DW | 1.764 | 1.961 | 1.857 |

| Variable | COMP_CFO | COMP_RET | COMP_PRC |

|---|---|---|---|

| COMP_CFO | 18.252 ** (8.928) | - | - |

| COMP_RET | - | 3.015 *** (0.613) | - |

| COMP_PRC | - | - | 0.0001 ** (5.98 × 10−5) |

| NFEE | 0.083 (0.152) | −0.131 (0.120) | 0.373 *** (0.087) |

| NFEE * COMP_CFO | 3.032 ** (1.378) | - | - |

| NFEE * COMP_RET | - | 0.485 *** (0.162) | - |

| NFEE * COMP_PRC | - | - | 3.30 × 10−5 *** (1.01 × 10−5) |

| CORR_ROA | 0.043 *** (0.014) | 0.042 * (0.023) | 0.057 (0.055) |

| CORR_CF | −0.070 *** (0.023) | −0.053 * (0.030) | −0.096 ** (0.048) |

| CORR_RET | 0.014 (0.033) | 0.042 (0.042) | 0.201 ** (0.094) |

| INDHERF | −2.870 ** (1.407) | −2.297 (1.572) | −8.034 *** (0.374) |

| SIZE | 0.689 *** (0.064) | 0.627 *** (0.067) | 0.720 *** (0.037) |

| BM | 0.074 (0.073) | 0.108 (0.079) | 0.449 *** (0.098) |

| LEV | 0.394 *** (0.138) | 0.468 *** (0.152) | −0.185 (0.214) |

| ROA | 0.435 * (0.248) | 1.209 *** (0.363) | 4.476 *** (0.606) |

| ADJROA | 1.520 *** (0.376) | 0.710 * (0.431) | 0.177 (0.826) |

| RET | 0.514 *** (0.137) | 0.483 *** (0.135) | 0.814 *** (0.203) |

| ADJRET | −0.605 *** (0.124) | −0.517 *** (0.139) | −0.821 *** (0.177) |

| GROWTH | −0.031 (0.081) | −0.027 (0.078) | −0.324 *** (0.124) |

| DIVYIELD | 0.924 *** (0.299) | 0.911 *** (0.328) | −0.501 (0.689) |

| RETVOL | 0.558 *** (0.198) | 0.486 *** (0.176) | 0.426 * (0.239) |

| CFVOL | 0.351 (0.418) | 0.330 (0.473) | −1.841 *** (0.704) |

| Hausman Test () | 35.483 | 37.124 | 40.011 |

| R2 (Adj) | 0.892 | 0.865 | 0.518 |

| F statistic | 62.111 *** | 48.591 *** | 91.106 *** |

| DW | 1.764 | 1.753 | 1.965 |

| Tests | M = 1 | M = 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Lagrange multiplier test (LM) H0: r = 0 vs. H1: r = 1 | 6.003 *** | 0.657 |

| Likelihood ratio test (LR.) H0: r = 0 vs. H1: r = 1 | 21.586 *** | 1.554 |

| Search Range | Optimal Threshold Value (c) | Transition Parameter (γ) | RSS | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

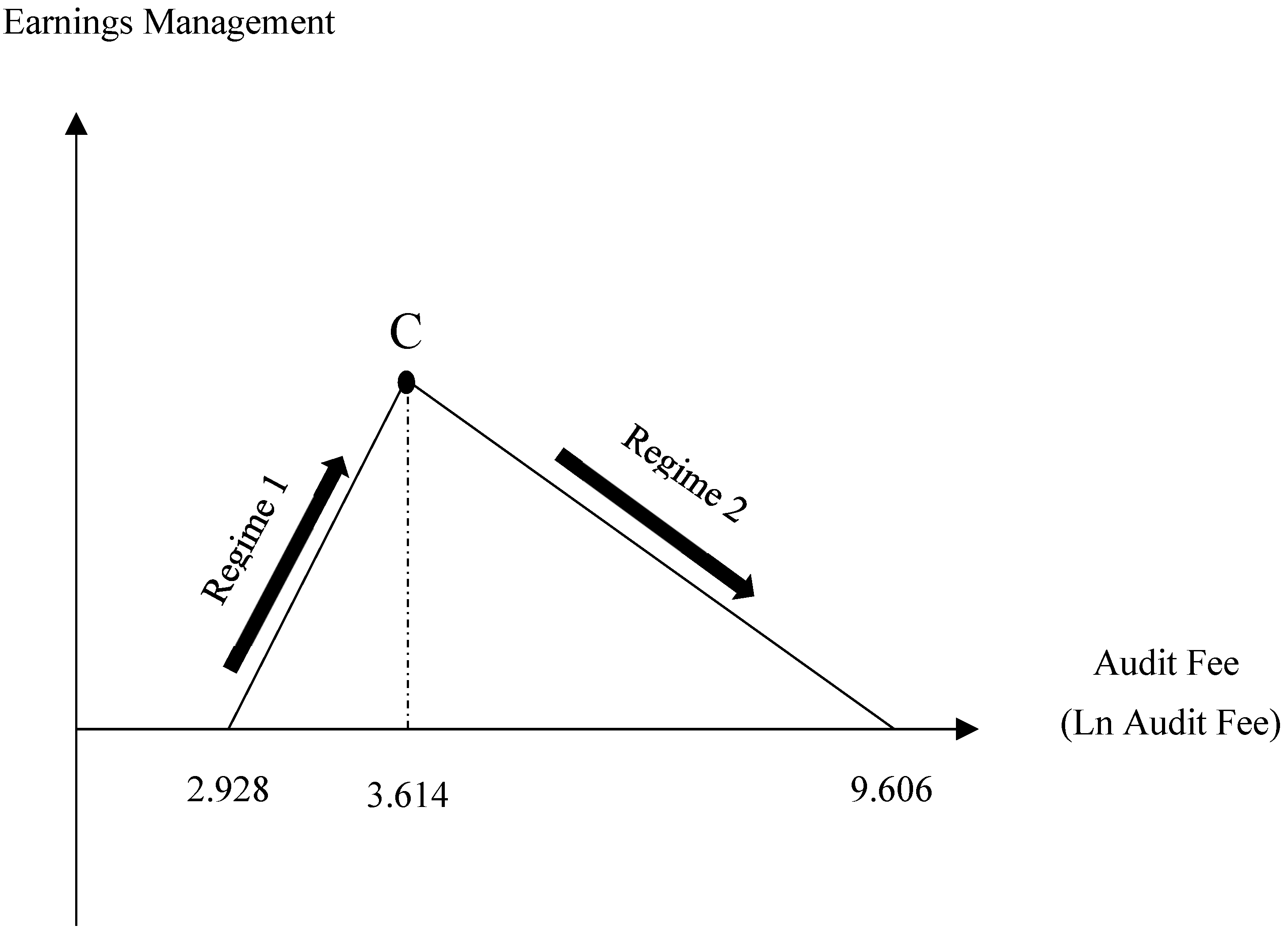

| LAF | 4.951 *** (2.026) | 846.237 *** (322.361) | −4.743 | −55.709 | −46.152 |

| Panel A: Linearity Model | |||

| Coeff. | SE. | t-value | |

| LAF | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.304 |

| ROA | 0.602 | 0.025 | 23.729 |

| Lev | −0.015 | 0.010 | −0.136 |

| Size | 0.009 | 0.001 | 5.809 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.632 | ||

| F statistic | 17.362 *** | ||

| Panel B: Non-linearity Model (Regime 1) | |||

| LAF | 0.014 *** | 0.005 | 2.823 |

| ROA | - | - | - |

| Lev | - | - | - |

| Size | - | - | - |

| C1 | 4.651 *** | 1.806 | 2.573 |

| γ | 846.237 *** | 319.117 | 2.651 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.621 | ||

| F statistic | 10.713 *** | ||

| Panel C: Non-linearity Model (Regime 2) | |||

| LAF | −0.004 *** | 0.001 | −4.424 |

| ROA | - | - | - |

| Lev | - | - | - |

| Size | - | - | - |

| C2 | - | - | - |

| γ | - | - | - |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.682 | ||

| F statistic | 35.399 *** | ||

| DW | 1.94 | ||

| Variable | COMP_CFO | COMP_RET | COMP_PRC |

|---|---|---|---|

| COMP_CFO | 6.614 ** (2.627) | - | - |

| COMP_RET | - | 3.876 *** (0.851) | - |

| COMP_PRC | - | - | 5.35 × 10−5 *** (1.19 × 10−5) |

| LAF | −0.122 * (0.069) | −0.101 *** (0.024) | −0.037 (0.024) |

| SQR | 0.062 (0.157) | −0.033 (0.041) | 0.262 *** (0.078) |

| SQR*LAF *COMP_CFO | −0.131 (0.669) | - | - |

| SQR*LAF *COMP_RET | - | −0.293 *** (0.105) | - |

| SQR*LAF *COMP_PRC | - | - | 3.66 × 10−6 ** (1.55 × 10−6) |

| CORR_ROA | 0.090 (0.066) | 0.039 * (0.022) | 0.049 *** (0.019) |

| CORR_CF | −0.139 (0.093) | −0.054 ** (0.036) | −0.072 *** (0.023) |

| CORR_RET | 0.126 (0.127) | 0.052 (0.036) | 0.028 (0.029) |

| INDHERF | −2.155 (1.198) | −2.540 * (1.479) | −3.328 ** (1.426) |

| SIZE | 0.635 *** (0.141) | 0.639 *** (0.056) | 0.679 *** (0.055) |

| BM | 0.494 *** (0.136) | 0.109 (0.076) | 0.058 (0.084) |

| LEV | 1.372 *** (0.405) | 0.522 *** (0.126) | 0.455 *** (0.127) |

| ROA | 0.321 (1.356) | 1.009 *** (0.351) | 0.030 (0.253) |

| ADJROA | 3.196 ** (1.499) | 0.957 ** (0.403) | 1.894 *** (0.327) |

| RET | 1.679 *** (0.577) | 0.531 *** (0.147) | 0.633 *** (0.122) |

| ADJRET | −1.471 ** (0.664) | −0.584 *** (0.135) | −0.757 *** (0.110) |

| GROWTH | −0.178 (0.283) | 0.000 (0.067) | −0.010 (0.063) |

| DIVYIELD | 1.407 * (0.848) | 1.010 *** (0.329) | 1.065 *** (0.322) |

| RETVOL | 1.263 *** (0.445) | 0.505 *** (0.143) | 0.377 ** (0.175) |

| CFVOL | −0.010 (0.918) | 0.306 (0.439) | 0.521 (0.409) |

| Hausman Test () | 28.335 | 31.415 | 30.483 |

| R2 (Adj) | 0.497 | 0.837 | 0.876 |

| F statistic | 6.995 *** | 38.586 *** | 53.047 *** |

| DW | 1.858 | 1.873 | 1.861 |

| Panel A: Linearity Model | |||

| Coeff. | SE. | t-value | |

| LAF | 0.021 | 0.008 | 2.625 |

| ROA | 0.536 | 0.083 | 6.457 |

| Lev | −0.142 | 0.130 | −1.092 |

| Size | 0.044 | 0.0.13 | 3.384 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.616 | ||

| F statistic | 14.222 *** | ||

| Panel B: Non-linearity Model (Regime 1) | |||

| LAF | 0.010 *** | 0.004 | 2.506 |

| ROA | - | - | - |

| Lev | - | - | - |

| Size | - | - | - |

| C1 | 3.614 *** | 1.679 | 2.152 |

| γ | 514.293 *** | 119.202 | 4.299 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.621 | ||

| F statistic | 18.357 *** | ||

| Panel C: Non-linearity Model (Regime 2) | |||

| LAF | −0.012 *** | 0.005 | −2.418 |

| ROA | - | - | - |

| Lev | - | - | - |

| Size | - | - | - |

| C2 | - | - | - |

| γ | - | - | - |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.621 | ||

| F statistic | 28.106 *** | ||

| DW | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daryaei, A.A.; Askarany, D.; Fattahi, Y. Impact of Audit Fees on Earnings Management and Financial Risk: An Analysis of Corporate Finance Practices. Risks 2024, 12, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks12080123

Daryaei AA, Askarany D, Fattahi Y. Impact of Audit Fees on Earnings Management and Financial Risk: An Analysis of Corporate Finance Practices. Risks. 2024; 12(8):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks12080123

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaryaei, Abbas Ali, Davood Askarany, and Yasin Fattahi. 2024. "Impact of Audit Fees on Earnings Management and Financial Risk: An Analysis of Corporate Finance Practices" Risks 12, no. 8: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks12080123

APA StyleDaryaei, A. A., Askarany, D., & Fattahi, Y. (2024). Impact of Audit Fees on Earnings Management and Financial Risk: An Analysis of Corporate Finance Practices. Risks, 12(8), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks12080123